Abstract

After being wrongfully blamed for their child’s disturbances, French parents of a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are now perceived as essential partners of care professionals. This shift in perspective has encouraged the development of parent training programs in the field of autism. In this paper, we present three programs currently implemented in France for parents of a child with ASD. We investigated their social validity, from the parents’ perspective. All three programs showed good social validity: attendance rate was good and parents were satisfied. In France, like elsewhere, more parents should be given the opportunity to participate in such programs to help them deal with the specific challenges of raising a child with ASD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Impact of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) on Parents’ Lives

Having a child with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a highly stressful experience (Davis and Carter 2008), that affects parent’s wellbeing, as well as their physical and psychological health (Dardas and Ahmad 2014; Giallo et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2009). The challenge of raising a child with ASD (Roper et al. 2014) can impair the quality of life of parents and of the whole family (Cappe et al. 2011). Thus, these families have specific needs, linked to the daily difficulties and challenges they have to face (Derguy et al. 2015).

While early diagnosis provides a degree of explanation for the child’s behavioral difficulties and helps parents accept that they are not to blame for it (Chamak et al. 2011), it can also be associated with a greater level of parenting stress (Osborne et al. 2008). Recent evidence underscores the importance of working alongside families, as family context can impact the development and escalation of severe behavior problems in children with ASD (Smith et al. 2014).

The French Historical Context of Autism

In France, the term ‘autism’ has long been associated with negative social representations and carries a painful history marked by psychogenic theories incriminating mothers for their child’s disturbances and excluding parents from childcare (Philip 2009). In the fifties, the psychoanalytical approach was at its strongest and most (fortunately not all) French people considered autism to be a psychological and sociological disorder (Feinstein 2011). Even suggesting there could be organic causes was a sacrilege (Feinstein 2011). In a context of ferocious opposition from the majority of his colleagues, French scientist Gilbert Lelord stands out as one of the world’s pioneers in autism research, as he was one of the first to carry out serious EEG tests in children with ASD and to develop an innovative technique designed to encourage communication through play (exchange therapy) (Lelord et al. 1973, 1991). In the seventies, parents initiated associative movements to speak out against the injustice of being wrongfully blamed, raising awareness of the social exclusion and stress they endured (Cappe and Boujut 2016; Philip 2009). French parents have long been dissatisfied with the diagnostic process and have been asking for earlier diagnosis and appropriate educational approaches (Chamak et al. 2011). In the late nineties, Howlin and Moore (1997) found a significant 10-year gap between the UK and France in the age of children at the time of diagnosis. Thanks to the initiatives of some regional child psychiatry hospital units, such as Montpellier, Paris, Toulouse and Tours, that paved the way and provided high-quality evaluations and services, the situation has now improved throughout the territory (Adrien et al. 2001; Baghdadli et al. 2006; Barthélémy et al. 1992; Lelord et al. 1991; Rogé 1989, 1998), with earlier evaluations and shorter waiting lists, aiming to offer earlier interventions to the child and his or her parents (Chamak et al. 2011). The widening and redefinition of the diagnostic criteria, as well as the active involvement and mobilization of parents’ associations have also led to an evolution towards less negative social representations on the etiology of ASD and more appropriate interventions and treatments (Chamak et al. 2011).

Supporting Parents: French Governmental Politics

Only recently did the French National Authority for Health acknowledge, for the first time, the central role of families in the child’s course of care, as well as the importance of parent-professional partnerships, in its best practice guidelines for the care of children and adolescents with ASD (HAS 2012). These guidelines also outlined the disorder’s repercussions on families and the necessity to give parents appropriate support. A year later, this approach was strengthened by the third 5-year governmental plan for autism (2013–2017), which insisted on the importance of “giving parents quality welcome, advice and training [...] to help families be present and active with their relatives, to protect them from exhausting and stressful situations and to allow them to play their role to the full on the long term” (Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, 2013—Action sheet 22, p. 96). In other words, parents or relatives are now perceived as essential partners of care professionals, and should be given appropriate knowledge and tools to deal with their child’s disorder. This change of perspective has encouraged the development of a variety of parent-centered programs, in the field of autism. Such approaches are popular across the Atlantic but only recently did they develop in Europe and particularly in France (Derguy et al. 2017, 2018; Ilg et al. 2018; Pickles et al. 2016; Rattaz et al. 2016).

Different Types of Parent Programs

For Schultz et al. (2011), parent training (or parent education) as an intervention draws its strength from its comprehensive nature, its ability to serve multiple functions, and its adaptable form (Schultz et al. 2011). It serves to inform parents, teach them new skills, and supplement child interventions (Brookman-Frazee et al. 2006). Bearss and collaborators (2015a, b), for their part, contrast parent training (providing specific strategies to manage disruptive behavior) with parent education (providing information about autism but no behavior management strategies) (Bearss et al. 2015b), and therefore distinguish parent programs on the basis of whether they are designed to actively engage the parent in promoting skill acquisition or behavior change in the child (parent-mediated intervention, direct benefit to the child), or whether they aim to provide parental support and promote knowledge gains around the child’s disability (parent support, indirect benefit to the child) (Bearss et al. 2015a). However, this clear dichotomous classification is probably not the best way to account for the diversity of parent programs. Indeed, despite different labels, theoretical backgrounds (e.g. psychoeducation, therapeutic education, etc.), aims and formats, parent programs respond to one or more of parents’ needs, ranging from information (parent education) to specific skill training (parent training). In addition, most programs include more or less psychosocial support. In fact, these programs may include similar components, but give them different weights, thus making each program unique. Such formal programs should systematically be evaluated from a parent perspective to assess parents’ responsiveness to these types of interventions (Clément and Schaeffer 2010; Durlak 2010; Durlak and DuPre 2008). The social validity concept can serve this purpose, as it underlines the importance of measuring the adequacy of the program’s objectives with societal expectations, including the accessibility and acceptability of interventions (Wolf 1978).

Study Objectives

Non Anglo-Saxon programs have been excluded from previous literature reviews (e.g. Schultz et al. 2011). Our aim was to review three programs developed and implemented in French-speaking areas (France and/or Province of Quebec, Canada) for parents of a child with ASD, and to evaluate their social validity, notably their accessibility and participants’ satisfaction (Clément and Schaeffer 2010).

Methods

Description of the Programs

As recommended by Derguy et al. (2015), all three programs were designed to provide support tailored to the specific needs of parents of a child with ASD, taking into account the child’s developmental specificities and behavioral manifestations.

As these programs were developed independently, each has its own format and characteristics that are summarized in Table 1. However, they are all intended for closed groups of parents whose children have been diagnosed with ASD. In order to be included in the study, the child’s diagnosis had to be established by a child psychiatrist, according to the international classification criteria for the autism phenotype (American Psychiatric Association 2003, 2013), complemented by one or more diagnostic evaluations, such as ADOS (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; Lord et al. 2000), ADI-R (Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised; Rutter et al. 2003), and/or CARS (Childhood Autism Rating Scale; Schopler et al. 1986). There are concerns regarding the clinical utility of the ADI-R and ADOS (Fitzgerald 2017), for these tools are based on a narrow view of the disorder and present a risk of under-diagnosing (Baird et al. 2006), especially in toddlers (Ventola et al. 2006). However, they are recommended by the French National Authority for Health to contribute to the ASD diagnostic process (HAS 2018), and they are validated and available in French. In this study, these evaluations were used as an inclusion criterion and always in complement of the clinical diagnosis of a professional clinician.

Beyond ASD, Parental Skills Within My Reach

The program <<Beyond ASD, parental skills within my reach>> (French name: <<Au-delà du TSA, des compétences parentales à ma portée>>) finds its roots in psychoeducation. Pychoeducation developed in the early fifties and integrates psychology and education science theories in order to help those with adjustment difficulties, by assisting and supporting their progression towards a better balance (Gendreau 2001). Beyond ASD was developed in 2004 as part of a Masters dissertation at the university of Quebec in Trois-Rivières (Hardy 2008), and revised following evaluations by the first participants (Stipanicic et al. 2014).

The main objective of this program is to allow participants to acknowledge, develop and update their parental skills. Beyond ASD’s five workshops address different issues (see Table 2 for details), but all aim to empower participants in their role of parent of a child with specific needs.

Pre- and post-intervention efficacy measures yielded significant positive results: after the program, parents were less stressed, they had a more positive perception of their situation and used more efficient coping strategies (Cappe et al. subm., Sankey et al. 2017). In addition, they experienced an improvement of their quality of life, notably regarding the relationship with their child and their general wellbeing (Cappe et al. in rev.). Finally, they had a better knowledge of the disorder (Sankey and Cappe 2017). Professionals reported that Beyond ASD could be easily implemented in a clinical service. They noted the high quality of the program, despite several adaptations that had to be made to respond to field constraints. Overall, professionals felt parents were responsive to the program (Sankey et al. in rev.).

The ETAP Program: Therapeutic Education Program for Parents of a Child with ASD

The ETAP program (in French “Education Thérapeutique Autisme et Parentalité”) was developed in accordance with the methodological specifications of therapeutic education (TE) (HAS 2007a, b, 2012). The World Health Organization (1998) defines therapeutic education as helping patients and/or their family acquire or maintain the skills they need to manage, as well as possible, their lives with a chronic disease. TE should help patients and their families to understand the disorder and its treatment, to work alongside professionals and to take responsibility for their own treatment, in order to help them maintain and improve their quality of life.

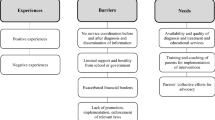

Topics and educational objectives are based on the results of two previous studies about parents’ needs and the determinants of parental stress in ASD (Derguy et al. 2015, 2016) and the expertise of nine professionals specialized in ASD and/or therapeutic education with complementary training (four psychologists, a speech-language therapist, a psychomotor therapist, a psychiatrist, a social worker and an archivist specialized in resources on ASD). In addition, parents’ educational needs in different areas (material, information, management of daily life, parental guidance, emotional and relational support) were assessed through one-on-one interviews (before and after the program), also called ‘educational diagnosis’ in the TE terminology (Derguy et al. 2015).

ETAP considers the ASD functioning specificities and targets two kinds of therapeutic education skills: self-care skills and psychosocial skills. The self-care skills aim to a better understanding of the disorder and its management (HAS 2007a). Psychosocial skills are personal and interpersonal, cognitive and physical skills, that help people make informed decisions, solve problems, communicate effectively and build healthy relationships, in order to acquire the ability to live in their environment and eventually change it (WHO 2003).

Table 3 summarizes the main goals of each workshop.

Preliminary results on a sample of 40 parents (ETAP group = 30, control group = 10) show a significant positive impact on the quality of life and depressive symptoms of the ETAP program participants (not the controls), but no significant decrease in anxiety symptoms. However, when we consider the proportion of parents with a significant anxiety state (above the clinical threshold of HADS, score ≥ 10; Zigmond and Snaith 1983), it tends to decrease after the program only for the ETAP group (Derguy et al. 2018).

A. B. C. of the Behavior of Children with ASD: Parents in Action!

The ABC program (in French: “L’A.B.C. du comportement de l’enfant ayant un TSA : Des parents en action !”) was developed as part of a doctoral dissertation carried out at the university of Strasbourg, first through a collaboration with a specialized hospital center dedicated to psychiatry (Centre Hospitalier de Rouffach, France) and then with the University Institute in Trois Rivières (Québec, Canada) (Ilg et al. 2018). It was developed within the theoretical framework of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) with incidental learning (Schreibman et al. 2015). The ABC program was designed to provide parents with quality information on ASD and behavioral management strategies in order to improve their everyday living and communication skills and to reduce challenging behaviors (see Table 4 for details).

The ABC program aims to train participants to gain confidence in their parental abilities and to better adjust to their child’s characteristics, in order to improve their family quality of life. Through manageable objectives, parents progressively learn to apply behavioral strategies within their home and the child’s daily routines in order to encourage desired behaviors and prevent challenging ones (Schreibman et al. 2015).

Preliminary results have shown that after participating in the ABC program, parents had significantly improved their knowledge in ASD and behavioral intervention strategies, as well as their children’s socialization skills, and had experienced a decrease in their parental stress (Ilg et al. 2018).

Evaluation of the Programs

General Evaluation Procedures

The evaluation procedures followed Smith et al.’s (2007) first two recommendations about the design of research studies on psychosocial interventions in autism. First, each of the three programs was formulated, initially applied to a small group of participants and eventually revised. Second, handbooks were developed and a systematic research plan was put forward, in accordance with each program’s specific goals.

Description of Participants

This paper includes data from 71 parents (Beyond ASD: 23 parents, ETAP: 30 parents and ABC: 18 parents). The description participants can be found in Table 5.

Measures

We investigated the social validity of these three programs, from the parents’ perspective. For each program, we evaluated parents’ attendance rate and level of satisfaction.

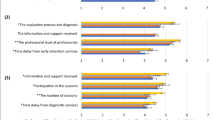

For Beyond ASD, parents completed a 14-item evaluation questionnaire at the end of each workshop (Gagnon 1998 in Naud and Sinclair 2003) to assess the program’s content (i.e. topics and objectives, 2 items), means (i.e. material and educational strategies, 3 items), facilitation (i.e. facilitators’ ability to lead the group, 4 items), atmosphere (i.e. respect, feeling of belonging to the group, 2 items), practical outcome (i.e. practical utility of what has been learnt, 2 items) and their general satisfaction (1 item). Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 4 (totally agree), with higher scores reflecting greater satisfaction. At the end of the program, the Parent Evaluation Inventory-Parent Treatment (PEI-Parent, Kazdin et al. 1992, French adaptation by Massé 1998) was used to assess the extent to which the program was viewed positively by the parents. The 19 items of the PEI-Parent are rated on a five-point Likert-type scale. It includes 2 subscales: the progress subscale, which includes 11 items and aims to assess whether parents feel they have made progress in their parental role thanks to participating in the program (maximum score of 55) and the acceptability subscale, which includes 8 items and measures whether parents found the program to be appropriate, interesting and stimulating (maximum score of 40). Higher scores indicate greater levels of progress and acceptability. Total score is obtained by summing all items. It ranges from 19 to 95. The PEI has shown high levels of reliability and validity and is able to discriminate among treatments and reactions to them (e.g., Kazdin 2000).

For the ETAP program, a seven-item questionnaire was specifically developed to assess participants’ satisfaction with the objectives of the program, as well as with the procedure and methods used in the program (content, group format, professionals). This questionnaire related to main goals, personal goals, content of the program, place in the group, level of confidence in the group, ease to speak in the group and professionals’ interventions (Derguy et al. 2017). Each item is rated on a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (Not at all Satisfied or Strongly Disagree) to 3 (Completely Satisfied or Strongly Agree). Higher scores reflect greater satisfaction. Each score is considered independently.

For the ABC program, the 9-item short form of the Treatment Evaluation Inventory (TEI-SF, Kelley et al. 1989), adapted and translated into French (Paquet et al. 2017), was used in post-intervention to assess parents’ acceptance of the provided procedures. TEI-SF items are designed to evaluate the acceptability, appropriateness, and predicted effectiveness of a given treatment (Kelley et al. 1989). Items are rated on a five-point Likert-type scale with fixed, anchored points, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Total scores are obtained by summing all items (minimum score 9 and maximum score 45), with higher scores indicating greater levels of acceptability. Based on Kazdin et al.s’ (1981) formula, a moderate acceptability rating on the 9-item TEI-SF would be 27 (resulting from a midpoint score of 3 on each item). Kelley et al. (1989) reported an internal consistency of.85 and more recently, Paquet et al. (2017) reported one of.79 in a French validation.

Satisfaction with the effects of the program was evaluated in post-intervention with the Therapy Attitude Inventory (TAI, translated and adapted into French with the author’s authorization; Eyberg 1993). The TAI includes 10 statements concerning feelings of progress in parental skills and knowledge, parental self-confidence, relationship with the child, child behavior, as well as indirect effects of the program on other family problems and general satisfaction about the program. Each statement is rated on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (I disliked it very much) to 5 (I liked it very much) (minimum score 10 and maximum score 50). A moderate acceptability rating on the TAI would be 30 (Kazdin et al. 1981). The scale has a good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of.88 (Eyberg 1993).

Data Presentation and Analysis

Results are presented as Mean Score (SD)/Theoretical Maximum Score.

In addition, for each program, we calculated the Effective attendance rate (EAR) as follows:

EAR (%) = Number of effective attendances/Number of expected attendances × 100 and Number of expected attendances = Total number of workshops × Number of parents enrolled.

Results

Across the three programs, none of the participants discontinued the intervention before their conclusion.

For Beyond ASD, almost all participants attended every single workshop (Table 6). Parents were satisfied with the workshops’ contents (mean score = 7.81 (0.27)/8), means (mean score = 11.51 (0.54)/12), facilitation (mean score = 15.73 (0.41)/16), practical outcome (mean score = 7.96 (0.12)/8), and atmosphere (mean score = 7.18 (0.59)/8). General satisfaction after the workshops was high (mean score = 3.94 (0.15)/4). At the end of the program, participants felt empowered in their parental role (PEI-Parent: mean progress score = 43.67 (5.56)/55) and were satisfied (Mean acceptability score = 37.33 (2.35)/40). Overall, Beyond ASD was rated 81 (7.23)/95 (85.3%) on the PEI-Parent scale.

For the ETAP program, participants showed regular attendance and half of them never missed a single workshop (Table 6). Parents reported being generally satisfied with all of the evaluated aspects (main goals: 2.48 (0.51)/3; personal goals: 2.46 (0.58)/3; content: 2.43 (0.50)/3; place in the group: 2.46 (0.50)/3; level of confidence in the group: 2.64 (0.48)/3; ease to speak in the group: 2.71 (0.46)/3; professionals’ interventions: 2.64 (0.48)/3).

For the ABC program, participants also showed regular attendance, but a majority (all of the fathers and a few mothers) missed at least one workshop (Table 6). Parents considered the strategies learned during the program could be used at home with their child (mean total acceptability score of 39.39 (4.39)/45 on the TEI-SF; Ilg et al. 2018) (mean total acceptability score of 39.39 (4.39)/45 on the TEI-SF). They were also very satisfied at the end of the program (mean total score of 40.89 (6.79)/50 on the TAI scale; Ilg et al. 2018).

Discussion

Beyond ASD, ETAP and ABC programs’ social validity assessments revealed that parents were globally satisfied with all three programs. Attendance rates were above 85% in all cases.

The need to support parents of a child with ASD has been clearly identified (Derguy et al. 2015; Papageorgiou and Kalyva 2010). Witnessing parents’ general satisfaction to receive tailored support was not surprising, given the scarcity of support programs currently available in France. Following the later recommendations of good practice of the French HAS (HAS and ANESM 2012), these three programs aim to bridge the gap in family support and training, and to strengthen the parent-professionals partnership (Krieger et al. 2013). Along with a few other programs (e.g. Rattaz et al. 2016), they contribute to enrich the offering of support for French speaking parents of a child with ASD. Ensuring the availability of a variety of programs, ranging from support and information to specific skill training, should allow professionals to select the most appropriate for the parents they meet. It is important to keep in mind that programs’ efficacy may vary greatly with child or parent characteristics (Baker-Ericzén et al. 2010; Cappe et al. 2014). Offering a wide range of programs makes it possible to individualize and optimize family interventions in order to improve parental quality of life and child development (Stahmer et al. 2011). Beyond ASD and ETAP are both destined to be a first step in parents’ stressful post-diagnosis path (Chamak et al. 2011). Beyond ASD includes several tasks and exercises that require that participants have good spoken and written language skills and it may not be suited for parents for whom French is not the first language, whereas ETAP does not have such requirements. ABC is better suited for advanced parents, who wish to acquire more technical skills in order to promote their child’s development. Some parents may benefit from participating to several of these programs. In Quebec, Beyond ASD and ABC are jointly offered one after the other. This might be an option to consider in France, because in our three programs, some participants expressed the need for more support (e.g. increase workshops’ number or length, include follow-up meetings or more individual/home visits, address additional topics). Several studies have reported that parents are satisfied with the group format and the social and emotional sharing opportunities it allows (Banach et al. 2010; Bitsika and Sharpley 2000). Participating in several group programs would also increase such opportunities. However, combining interventions requires prior consideration on whether these interventions are complementary, partially overlapping (in which case one would be redundant), and whether they use different or even mutually exclusive conceptual or operational vocabularies, which can be confusing for the families (Vivanti 2017).

We recorded surprisingly high attendance rates for all three programs, despite the well-known pressing schedule of parents of a child with ASD (Cappe et al. 2011). However, some participants did not attend every single workshop. For Beyond ASD, very few parents (2/23) missed a workshop, but for ETAP (15/30) and ABC (11/18, mostly fathers) more did. One of the reasons for this difference in assiduity may be that Beyond ASD includes only five workshops, whereas ETAP includes seven and ABC 12. It may have been more difficult for parents, especially fathers, to commit for many workshops over a long period of time. Hence, it seems important to offer programs that are adapted to parents’ schedules. Particular thought should be given to the time when workshops should take place and eventually to provide childcare during workshops. Professionals should encourage parents’ attendance all along the programs. In addition, further developments could include distance training for overstretched or isolated parents, who wouldn’t otherwise be able to attend workshops.

Limits

This study has several limitations. First, the use of different tools in the programs’ evaluation procedures makes it difficult to compare results. This is a common limitation when attempting to compare programs, even more so on the international scene, because the same questionnaires are not always available in different languages. However, the aim of this paper was not to compare results. Second, these evaluations included a small number of participants, who may not have been representative of the population. Besides, most participants lived as a couple and the situation of single parents may be very different. Beyond ASD and ETAP included a majority of mothers among their participants. Professionals often expect fathers to be less available and/or interested in taking part in such programs, and generally consider mothers as their main interlocutor for childcare. However, the ABC program insisted on the involvement of both parents and managed to include 16 parents, mothers and fathers of 8 families. Even though all fathers missed at least one of the twelve workshops, none of them actually dropped out of the program. Given the importance of consistency between parents in teaching new skills to children with ASD, encouraging fathers’ participation in such programs could be an interesting lead to follow. On the long run, it would be worthwhile to systematically consider offering such support programs to both parents in the post-diagnosis course of care.

Perspectives and Conclusion

In this paper, we have documented that the programs “Beyond ASD, parental skills within my reach”, “ETAP” and “ABC of the behavior of children with ASD: parents in action!” were experienced as being socially acceptable by the parents who participated. In France, the lack of research interest regarding parents of a child with ASD is probably one of the many collateral damages of a painful history marked by psychogenic theories incriminating mothers for their child’s disturbances (Greenberg et al. 2006). The accusations that have long been abusively addressed to families have led to the widespread idea that supporting parents would be tantamount to acknowledge their possible failures. In this regard, the best practice guidelines of the French National Authority for Health and the fourth governmental plans for autism (2018–2022) represent an important step towards better consideration of families. French health and medico-social professionals should now be given appropriate means to ensure successful implementation of these programs, which require human resources, as well as significant training and preparation time. This remains a challenge and requires a cultural shift, as in France socio-medical establishments traditionally focus resources and interventions on the person with ASD while families are often pushed aside.

References

Adrien, J.-L., Roux, S., Couturier, G., Malvy, J., Guerin, P., Debuly, S., et al. (2001). Towards a new functional assessment of autistic dysfunction in children with developmental disorders: The behaviour function inventory. Autism, 5(3), 249–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361301005003003.

American Psychiatric Association. (2003). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR) (2nd ed.). American Psychiatric Pub.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-V®). American Psychiatric Pub.

Baghdadli, A., Beuzon, S., Bursztejn, C., Constant, J., Desguerre, I., Rogé, B., et al. (2006). Recommandations pour la pratique clinique du dépistage et du diagnostic de l’autisme et des troubles envahissants du développement. Archives de Pédiatrie, 13(4), 373–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcped.2005.12.011.

Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., Meldrum, D., & Charman, T. (2006). Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). The Lancet, 368(9531), 210–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69041-7.

Baker-Ericzén, M. J., Hurlburt, M. S., Brookman-Frazee, L., Jenkins, M. M., & Hough, R. L. (2010). Comparing child, parent, and family characteristics in usual care and empirically supported treatment research samples for children with disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 18(2), 82–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426609336956.

Banach, M., Iudice, J., Conway, L., & Couse, L. J. (2010). Family support and empowerment: Post autism diagnosis support group for parents. Social Work with Groups, 33(1), 69–83.

Barthélémy, C., Adrien, J.-L., Roux, S., Garreau, B., Perrot, A., & Lelord, G. (1992). Sensitivity and specificity of the Behavioral Summarized Evaluation (BSE) for the assessment of autistic behaviors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 22(1), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01046400.

Bearss, K., Burrell, T. L., Stewart, L., & Scahill, L. (2015a). Parent training in autism spectrum disorder: What’s in a name? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 18(2), 170–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-015-0179-5.

Bearss, K., Johnson, C., Smith, T., Lecavalier, L., Swiezy, N., Aman, M., et al. (2015b). Effect of parent training vs parent education on behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 313(15), 1524–1533. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.3150.

Bitsika, V., & Sharpley, C. (2000). Development and testing of the effects of support groups on the well-being of parents with autism-II: Specific stress management techniques. Journal of Applied Health Behaviour, 2(1), 8–15.

Brookman-Frazee, L., Stahmer, A., Baker-Ericzen, M. J., & Tsai, K. (2006). Parenting interventions for children with autism spectrum and disruptive behavior disorders: Opportunities for cross-fertilization. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 9(3–4), 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-006-0010-4.

Cappe, E., Albert-Benaroya, S., Downes, N., Allard Ech-Chouikh, J., De Gaulmyn, A., Luperto, L., et al. (in revision). Preliminary results of the effects of a psychoeducational program on stress and quality of life among French parents of a child with autism spectrum disorder.

Cappe, E., & Boujut, E. (2016). L’approche écosystémique pour une meilleure compréhension des défis de l’inclusion scolaire des élèves ayant un trouble du spectre de l’autisme. ANAE, 143–4 vol 28, 391–401.

Cappe, E., Chatenoud, C., & Paquet, A. (2014). Les caractéristiques des personnes ayant un TSA et des autres membres de la famille influençant l’adaptabilité familiale. In La famille et la personne ayant un trouble du spectre de l’autisme. Comprendre: soutenir et agir autrement. Montréal: Editions Nouvelles.

Cappe, E., Wolff, M., Bobet, R., & Adrien, J.-L. (2011). Quality of life: a key variable to consider in the evaluation of adjustment in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders and in the development of relevant support and assistance programmes. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9861-3.

Chamak, B., Bonniau, B., Oudaya, L., & Ehrenberg, A. (2011). The autism diagnostic experiences of French parents. Autism, 15(1), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361309354756.

Clément, C., & Schaeffer, E. (2010). Évaluation de la validité sociale des interventions menées auprès des enfants et adolescents avec un TED. Revue de Psychoéducation, 39(2), 207–218.

Dardas, L. A., & Ahmad, M. M. (2014). Quality of life among parents of children with autistic disorder: A sample from the Arab world. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(2), 278–287.

Davis, N. O., & Carter, A. S. (2008). Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(7), 1278–1291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0512-z.

Derguy, C., M’Bailara, K., Michel, G., Roux, S., & Bouvard, M. (2016). The need for an ecological approach to parental stress in autism spectrum disorders: the combined role of individual and environmental factors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2719-3.

Derguy, C., Michel, G., M’Bailara, K., Roux, S., & Bouvard, M. (2015). Assessing needs in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A crucial preliminary step to target relevant issues for support programs. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 40(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2015.1023707.

Derguy, C., Pingault, S., Poumeyreau, M., & M’bailara, K. (2017). L’éducation thérapeutique: un modèle pertinent pour accompagner les parents d’enfant avec un Trouble du Spectre de l’Autisme ? Education Thérapeutique du Patient -. Therapeutic Patient Education, 9(2), 20203. https://doi.org/10.1051/tpe/2017013.

Derguy, C., Poumeyreau, M., Pingault, S., & M’bailara, K. (2018). Un programme d’éducation thérapeutique destiné à des parents d’enfant avec un TSA: résultats préliminaires concernant l’efficacité du programme ETAP. L’Encéphale. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2017.07.004.

Durlak, J. A. (2010). The importance of doing well in whatever you do: A commentary on the special section, “Implementation research in early childhood education. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25(3), 348–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2010.03.003.

Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation Matters: A Review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3–4), 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0.

Eyberg, S. (1993). Consumer satisfaction measures for assessing parent training programs. In L. VandeCreek, S. Knapp & T. L. Jackson (Eds.), Innovations in clinical practice: A source book (Vol. 12, pp. 377–382). Sarasota: Professional Resource Press/Professional Resource Exchange.

Feinstein, A. (2011). A history of autism: Conversations with the pioneers. New York: Wiley.

Fitzgerald, M. (2017). The clinical utility of the ADI-R and ADOS in diagnosing autism. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 211(2), 117–117. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.211.2.117.

Gendreau, G. (2001). Jeunes en difficulté et intervention psychoéducative. Montréal: Sciences et Culture.

Giallo, R., Wood, C. E., Jellett, R., & Porter, R. (2011). Fatigue, wellbeing and parental self-efficacy in mothers of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361311416830.

Greenberg, J. S., Seltzer, M. M., Hong, J., & Orsmond, G. I. (2006). Bidirectional effects of expressed emotion and behavior problems and symptoms in adolescents and adults with autism. American Journal of mental Retardation: AJMR, 111(4), 229–249. https://doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017(2006)111%5B229:BEOEEA%5D2.0.CO;2.

Hardy, M. C. (2008). Lorsque les competences des uns valorisent celles des autres. En Pratique, 9, 9–10.

Haute Authorité de Santé. (2018). Trouble du spectre de l’autisme. Signes d’alerte, repérage, diagnostic et évaluation chez l’enfant et l’adolescent. Recommandations de bonne pratique. Annexe 4.

Haute Autorité de Santé. (2007a). Education thérapeutique du patient: Définition, finalités et organisation.

Haute Autorité de Santé. (2007b). Education thérapeutique du patient. Comment élaborer un programme spécifique d’une maladie chronique.

Haute Autorité de Santé. (2012). Auto-évaluation annuelle d’un programme d’éducation thérapeutique du patient. Guide pour les coordonnateurs et les équipes.

Haute Autorité de Santé, & Agence nationale de l’évaluation et de la qualité des établissements et services sociaux et médico-sociaux. (2012). In Recommandation de bonne pratique. Autisme et Troubles envahissant du développement: interventions éducatives et thérapeutiques coordonnées chez l’enfant et l’adolescent. Saint-Denis La Plaine: Haute Autorité de Santé.

Howlin, P., & Moore (1997). Diagnosis in autism: A survey of over 1200 patients in the UK. Autism, 1(2), 135–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361397012003.

Ilg, J., Jebrane, A., Paquet, A., Rousseau, M., Dutray, B., Wolgensinger, L., & Clément, C. (2018). Evaluation of a French parent-training program in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Psychologie Française. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psfr.2016.12.004.

Johnson, N., Frenn, M., Feetham, S., & Simpson, P. (2011). Autism spectrum disorder: Parenting stress, family functioning and health-related quality of life. Families, Systems, & Health, 29(3), 232–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025341.

Kazdin, A. E. (2000). Perceived barriers to treatment participation and treatment acceptability among antisocial children and their families. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 9(2), 157–174.

Kazdin, A. E., French, N. H., & Sherick, R. B. (1981). Acceptability of alternative treatments for children: Evaluations by inpatient children, parents, and staff. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49(6), 900–907.

Kazdin, A. E., Siegel, T. C., & Bass, D. (1992). Cognitive problem-solving skills training and parent management training in the treatment of antisocial behavior in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60(5), 733–747.

Kelley, M. L., Heffer, R. W., Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (1989). Development of a modified treatment evaluation inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 11(3), 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00960495.

Krieger, A.-E., Saïas, T., & Adrien, J.-L. (2013). Promouvoir le partenariat parents–professionnels dans la prise en charge des enfants atteints d’autisme. L’Encéphale, 39(2), 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2012.06.002.

Lee, G. K., Lopata, C., Volker, M. A., Thomeer, M. L., Nida, R. E., Toomey, J. A., et al. (2009). Health-related quality of life of parents of children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(4), 227–239.

Lelord, G., Barthélémy, C., Martineau, J., Bruneau, N., et al. (1991). Free acquisition, free imitation, physiological curiosity and exchange and development therapies in autistic children. Brain Dysfunction, 4(6), 335–347.

Lelord, G., Laffont, F., Jusseaume, P., & Stephant, J. L. (1973). Comparative study of conditioning of averaged evoked responses by coupling sound and light in normal and autistic children. Psychophysiology, 10(4), 415–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1973.tb00799.x.

Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook, E. H., Leventhal, B. L., DiLavore, P. C., et al. (2000). The autism diagnostic observation schedule—Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(3), 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005592401947.

Naud, J., & Sinclair, F. (2003). EcoFamille: Programme de Valorisation du Developpement du Jeune Enfant Dans le Cadre de la Vie Familiale: Guide D’animation. Cheneliere/McGraw-Hill.

Osborne, L. A., McHugh, L., Saunders, J., & Reed, P. (2008). A possible contra-indication for early diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Conditions: Impact on parenting stress. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2(4), 707–715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2008.02.005.

Papageorgiou, V., & Kalyva, E. (2010). Self-reported needs and expectations of parents of children with autism spectrum disorders who participate in support groups. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(4), 653–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2010.01.001.

Paquet, A., McKinnon, S., Clément, C., & Rousseau, M. (2017). Traduction et adaptation du TEI-SF afin de documenter l’acceptabilité sociale de l’intervention comportementale intensive. http://www.em-consulte.com/en/article/1109038/data/revues/12691763/unassign/S1269176317300044/. Accessed 19 December 2017.

Philip, C. (2009). Autisme et parentalité. Paris: Dunod.

Pickles, A., Couteur, A. L., Leadbitter, K., Salomone, E., Cole-Fletcher, R., Tobin, H., et al. (2016). Parent-mediated social communication therapy for young children with autism (PACT): Long-term follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 388(10059), 2501–2509. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31229-6.

Rattaz, C., Alcaraz-Darrou, C., & Baghdadli, A. (2016). Évaluation des effets d’un groupe d’accompagnement parental sur le stress et la qualité de vie après l’annonce du diagnostic de Trouble du Spectre Autistique (TSA) chez leur enfant. Annales Médico-Psychologiques, Revue Psychiatrique, 174(8), 644–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2015.10.023.

Rogé, B. (1989). Adaptation Française de l’échelle d’évaluation de l’autisme infantile (C.A.R.S.). Issy-les-Moluineaux: Editions d’Applications Psychotechniques.

Rogé, B. (1998). The development of services for autistic persons and training for professionals: The situation in France. In R. Jordan & S. Powell (Eds.), Guide on education of children and youth with autism (pp. 115–119). Paris: UNESCO.

Roper, S. O., Allred, D. W., Mandleco, B., Freeborn, D., & Dyches, T. (2014). Caregiver burden and sibling relationships in families raising children with disabilities and typically developing children. Families, Systems & Health: The Journal of Collaborative Family Healthcare, 32(2), 241–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000047.

Rutter, M., Le Couteur, A., & Lord, C. (2003). ADI-R: Autism Diagnostic Interview Revised—Manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Sankey, C., & Cappe, E. (2017). Beyond autism spectrum disorder: Parental skills within my reach: Evaluation of a psycho-educative program intended for parents of a child with autism spectrum disorder. In ABAI’s Ninth International Conference, Paris, France, November 14–15.

Sankey, C., Girard, S., & Cappe, E. (in revision). Evaluation of the implementation process and social validity of a support program for parents of child with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Schopler, E., Reichler, R. J., & Renner, B. R. (1986). The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Schreibman, L., Dawson, G., Stahmer, A. C., Landa, R., Rogers, S. J., McGee, G. G., et al. (2015). Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: Empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(8), 2411–2428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2407-8.

Schultz, T. R., Schmidt, C. T., & Stichter, J. P. (2011). A review of parent education programs for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 26(2), 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357610397346.

Smith, L. E., Greenberg, J. S., & Mailick, M. R. (2014). The family context of autism spectrum disorders: Influence on the behavioral phenotype and quality of life. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(1), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2013.08.006.

Smith, T., Scahill, L., Dawson, G., Guthrie, D., Lord, C., Odom, S., et al. (2007). Designing research studies on psychosocial interventions in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(2), 354–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0173-3.

Stahmer, A. C., Schreibman, L., & Cunningham, A. B. (2011). Toward a technology of treatment individualization for young children with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Research, 1380, 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.043.

Stipanicic, A., Couture, G., Rivest, C., & Rousseau, M. (2014). Développement des modèles théoriques d’un programme destiné à des parents d’enfants présentant un trouble du spectre de l’autisme. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 20(3), 19–29.

Ventola, P. E., Kleinman, J., Pandey, J., Barton, M., Allen, S., Green, J., et al. (2006). Agreement among four diagnostic instruments for autism spectrum disorders in toddlers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(7), 839–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0128-8.

Wolf, M. M. (1978). Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203.

World Health Organization. (2003). Skills for health. Geneva: WHO.

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. (1998). Therapeutic patient education: continuing education programmes for health care providers in the field of prevention of chronic diseases: Report of a WHO working group. Accessed 24 January, 2018, from http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/108151.

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361301005003003.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank the parents who took part in the three programs as well as all their clinical partners. More particularly, authors are grateful to: For Beyond ASD: the Centre Universitaire de Pédopsychiatrie du CHRU de Tours, in particular Pr. Frédérique Bonnet-Brilhault, Dr. Joëlle Malvy and Julie Allard Ech Chouikh, and the Centre de Ressources pour l’Autisme de Haute Normandie, in particular Dr. Antoine Rosier and Romain Taton. For ETAP: the Centre Ressources Autisme Aquitaine, in particular Pr. Manuel Bouvard and the Child psychiatry department of Robert Debré Hospital (Paris), in particular Pr. Richard Delorme and Marion Poumeyreau, as well as Katia M’bailara and Solenne Pingault for sharing their expertise in Therapeutic Education and ASD. For ABC: The Centre Hospitalier Spécialisé de Rouffach, in particular Dr. Benoît Dutray and Laure Wolgensinger, for sharing their expertise in Therapeutic Education and ASD and for the implementation of pilot groups.

Funding

Research for Beyond ASD received financial support from the Caisse Nationale de Solidarité pour l’Autonomie (CNSA) through the 2014 call for projects of the Institut de Recherche en Santé Publique (IRESP). Research for ETAP received financial support from the French ministry of higher education and research and from the Orange Foundation (Grant No. 2013 028). Research for ABC received financial support from the Centre Hospitalier Spécialisé de Rouffach (France) and from the Ecole Supérieure du Professorat et de l’Education of the Université de Strasbourg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CS coordinated and drafted the manuscript; CD conceived and coordinated the study regarding the ETAP program and helped draft the manuscript; CC and JI conceived and coordinated the study regarding the ABC program and helped draft the manuscript; ÉC had the idea of the manuscript, conceived and coordinated the study regarding the Beyond ASD program, and supervised and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

For all three programs, participants were given the necessary information and gave their informed consent to take part in the study. In addition, all procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the respective institutional and/or national research committees and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sankey, C., Derguy, C., Clément, C. et al. Supporting Parents of a Child with Autism Spectrum Disorder: The French Awakening. J Autism Dev Disord 49, 1142–1153 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3800-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3800-x