Abstract

A family systems approach is required to identify the needs of families of children with autism. This paper explores how grandparents support children with autism and their parents using a family systems perspective. A thematic analysis of eighteen semi-structured interviews was conducted with participants from nine families, capturing experiences of both parents’ and grandparents’. Themes identified were family recalibrating; strengthening the family system; and current needs and future concerns of grandparents. The views of families indicated the overwhelming need to acknowledge the grandparental role in supporting families that strengthen the family system by supporting the needs of a child with autism. Findings revealed that grandfathers have a calming role in these families where children have significant behavioural difficulties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Families provide critical support for children with disabilities (Neely-Barnes and Dia 2008). Family functioning plays an important role in understanding parental well being and parenting interactions with children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Pruitt et al. 2016). However, raising a child with ASD is stressful and challenging for parents and families (Myers et al. 2009). Johnson et al. (2011) reported that parents of children with autism are under significant stress. Of note is the impact of how parents perceive this stress. For example, Ooi et al. (2016) identified that the psychological well being of parents may not only be attributed to stress causing behaviours in their child with ASD, but also to how parents define the behaviour that is perceived to be difficult.

Parents’ perceptions of stigma (Broady et al. 2017; Farrugia 2009) and increased burden, relative to the severity of their child’s symptoms (Stuart and McGrew 2009), can result in significant psychological distress for many families (Benson and Karlof 2009). The issue of stigma is strongly perceived by parents as a result of the hidden difficulties associated in children with ASD (Ooi et al. 2016). The impact of a child’s mental health can also impact on family functioning, where greater mental health difficulties in children with ASD are associated as a result of children’s greater social responsiveness difficulties and poorer social skills due to ASD (Ratcliffe et al. 2015). This study revealed that social skills difficulties in a sample of children with ASD without Intellectual Disability (ID) explained 49.7% variance in mental health measures of children with ASD from parents reports, compared to 42.1% variance in children with mental health difficulties, ASD and ID. These scores indicate that children with ASD and without ID are possibility at greater risk of developing co-morbid mental health difficulties due to an increased awareness of their social skills difficulties, the expectations placed on them as a result of their hidden difficulties and the challenges in coping with social demands. Additionally, parents report experiences of lower marital quality than other parents (Harper et al. 2013; Divan et al. 2012). Research has revealed that gender disparities exist when parenting a child with autism, with mothers more negatively impacted than fathers (Gau et al. 2011). However, other findings suggest that mothers and fathers experience similar levels of relationship satisfaction in parenting a child with autism, rejecting the gender role variances (Langley et al. 2017).

There are positive aspects to parenting a child with autism (Potter 2016; Markoulaksis et al. 2012; Kayfitz et al. 2010) including stronger bonds between family members and a greater acceptance of life’s events. Research has revealed an increased sense of unity that benefitted marriages as a result of caring for a child with autism (Markoulaksis et al. 2012). Mothers experienced social benefits of parenting a child that included new social opportunities such as new friendships within the autism community (Markoulaksis et al. 2012). Mothers also reported high daily positive interactions with their child with ASD when their family was more cohesive (Pruitt et al. 2016). A thematic analysis of gratitude letters written by mothers of children with ASD revealed their gratitude for social supports that included both emotional and instrumental supports. Some mothers also expressed gratitude to their religious communities for giving them support to raise a child with a disability (Timmons et al. 2017). Moreover, reports of the benefits of having a child with ASD in the family include a greater awareness of others’ needs, a greater appreciation of differences that exist between people, and a greater clarity about things that matter (Schlebusch and Dada 2018). There is an imbalance in autism research on families, with a dearth of research on fathers’ experiences, biased towards mothers’ experiences (Ooi et al. 2016). Recently, Potter (2016) revealed that fathers’ experiences of parenting their child with ASD included their reports of appreciating their child’s individual qualities and valuing the strong emotional bond between father and child.

Intergenerational relationships, i.e. the interactions that occur between grandparents, parents and children, affect a family (Seligman and Darling 2007). The quality of relationships that exist between parents and grandparents may be a source of support or stress that can impact on the family system (Cox and Paley 1997). Hastings (1997) suggests that grandparents of children with disabilities act as important sources of practical and emotional support. However, grandparent involvement in families of children with disabilities can also be complex (Sullivan et al. 2012). Intergenerational relationships can provide insights into family functioning when a grandchild has a disability (Barnett et al. 2010; Mouzourou et al. 2011), including families of children with autism (Kahana et al. 2015). Highly involved grandparents are a source of much needed support to parents and grandchildren (Barnett et al. 2010).

Autism is considered a significant stressor for families, including grandparents, and presents significant challenges including role confusion among members (Hillman 2007). Grandparents provide both emotional and instrumental support to families (Harper et al. 2013; Divan et al. 2012). Nonetheless, Hillman (2007) also revealed possible negative influences of grandparents in relation to disciplinary or treatment issues concerning a child where poor familial relations reduced the participation of grandparents in providing necessary supports. In families of a child with autism, the grandparent-parent relationship can play “a potent role” (Glasberg and Harris 1997, p. 17), where maternal grandmothers can have a more supportive role than paternal grandmothers. Moreover, Glasberg and Harris (1997) revealed that when paternal grandmothers were familiar with their grandchild, their ratings were similar to those of maternal grandmothers. These researchers unveiled the interactive complexity of relationships in families and identified that the position a grandparent has in the family system determined how they engaged within that system.

A web-based survey, with over 1870 grandparents of children with autism in the United States (Hillman et al. 2017), revealed that grandparents played a major supportive role in their families. Grandparents reported that their grandchild brought both them and the child’s parents closer. Many grandparents provided support by way of financial aid with a quarter of grandparents reporting that they had moved closer to, or moved in with, their family to ease the financial burden that the family was experiencing (Hillman et al. 2016). Difficulties experienced by grandparents of children with a disability, i.e. family conflicts, the aging process, and sacrificing their own work or retirement opportunities to support their families, impacted on their lives (Miller et al. 2012). Margetts et al. (2006) disclosed that grandparents of children with autism were concerned about the double burden they experienced in caring for their child and grandchild and they believed they were re-entering parenthood with their own child. Furthermore, the stress of their role within the family system was an additional source of concern for these grandparents.

A multicultural perspective on the role grandparents play in families of children with autism is sparse and more research is required to enhance our understanding of the contributions grandparents make and the supports they need. Recent research has highlighted the need to explore the psychological well being of all grandparents who provide supplementary child care (Kim et al. 2017), not only grandparents of children with disabilities. For grandparents in African American families who resided in the same household as their grandchildren, it was the religious role that created opportunities for some of the most meaningful contact with their grandchildren (King et al. 2008). Cultural norms of providing this care may differentially affect the psychological well being of grandparents who provide care, based on race, ethnicity or country of origin (Kim et al. 2017). This suggests that the psychological well being of grandparents may be more greatly affected due to the additional demands placed on the family system when a grandchild has a special educational need, such as ASD.

Theoretical Framework: Family Systems Approach

Researchers have suggested that family systems theory (FST), encompassing an ecological family systems approach, could provide a better insight into family dynamics (Ayvazoglu et al. 2015; Cridland et al. 2014). Recent research has called for further studies to determine the roles that extended families play in supporting children with disabilities (Ayvazoglu et al. 2015), particularly their impact on family subsystems (Langley et al. 2017), as this approach captures the heterogeneity of families (Cridland et al. 2014). Minuchin (1988, p. 21) suggests systems research recognises

the family as an organised whole, albeit with clear subsystems; explores the patterns of interaction around a central anchor person; and looks at homeostasis and change at a point of dramatic transition, considers the interaction of developmental realities…and the process by which changing relationships are calibrated.

Specifically, an exploration of the role of grandparents in families who have a child with ASD is required by unveiling the interactions that occur between grandparents and parents within their respective subsystems. How both subsystems adapt to the needs of a child with ASD, as the central anchor person, requires investigation. Adopting a systems perspective to family interactions proposes that families are in a constant state of change (Galvin et al. 2005). Few empirical studies have been conducted on families who have a child with a developmental disability within a systems framework (Head and Abbeduto 2007). Autism services providers should acknowledge a family’s belief system that recognises a family as a unique entity (King et al. 2009). Additionally, calls for a systems approach to family research from multiple perspectives is required (Kazak et al. 2009; Canary 2008) including the influence of grandparents (Hillman et al. 2016). Studies have rarely explored the relationship dynamics between family subsystems (Cridland et al. 2014).

This paper examined the shared experiences of interactions in both the parental and grandparental subsystems to identify the role that grandparents of children with autism have within a family system. This paper explored the perspectives of both parents and grandparents, within a dynamic, interactive, family system framework, and how their roles adapted to change. This paper enhances our understanding of grandparents’ roles from the perspectives of both parents and grandparents of children with autism.

Methods

Participants

Using a snowball sampling strategy, participants were recruited from inclusive primary schools that had satellite classes for children with autism, and from specialist schools for children with autism and ID. Children who access satellite classes usually have a diagnosed borderline intellectual ability or above, and have a diagnosis of ASD. Typically, children access these classes due to the difficulties they experience in a regular classroom. All children who attend special schools have a diagnosis of ASD and ID. These children usually access a specialist curriculum compared to their peers in inclusive settings. These schools were located in a region in the Republic of Ireland. This sampling technique was used to access a specific cohort that otherwise was difficult to access. Following ethical approval, the researchers obtained the support of school principals in four schools in the region to assist in disseminating information about this study.

All parents, who initially volunteered to participate, were interviewed for this research, comprising of nine families in total. Only three families, who had children in a special class attached to a mainstream school, volunteered to participate. All other families had children attending a special school setting. All children whose families participated in this research presented with ID in addition to their diagnosis of autism. Written informed consent was obtained from parents and grandparents of the children, and consent was obtained from parents in relation to the participation of specified grandparents. This research was conducted, and ethical approval was granted, in accordance with ethical guidelines set by an ethics committee in the university where the researchers are based.

Eighteen interviews were completed with six mothers, three dyadic sets of parents, two grandfathers, four grandmothers and three dyadic sets of grandparents, consisting of input from nine families of children with autism. Data saturation (Saunders et al. 2018), interpreted as the number of interviews needed, was deemed to be reached when nothing new became apparent in interviews. Furthermore, as data gathering commenced no additional participants emerged. The variety of participants was to allow for accounts of experiences within families to add to the richness and depth of qualitative findings (Polkinghorne 2005). Parents ranged in age from 30 to 49 years. Grandparents ranged in age from 50 to 84 years. All participants were of Irish heritage. Most of the participants had a child or grandchild that attended a special school. One mother had a child who accessed mainstream education and three families had children who attended a special class within a mainstream school. One mother had two children with autism; all other interviews were conducted in families with one child. For the purposes of clarity, participants’ demographics are presented in Table 1. To protect identities of all participants, pseudonyms and age ranges are given.

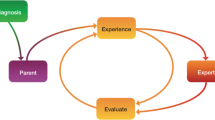

Procedure

Two semi-structured interviews schedules (for parents and grandparents) were devised. Initially, each interview commenced with open questions on participants’ experiences of the grandparent role in their respective families. Subsequently, questions more specifically addressed in interviews with both groups included their experiences of the lead up to diagnosis, their experiences of the diagnostic process, family functioning following diagnosis, impact on the family, and the supportive role of grandparents. Face-to–face interviews were conducted in the family home apart from two interviews which took place in school settings. Each interview lasted approximately 1 h. Consent was given for each interview to be electronically audio recorded to allow for verbatim transcription. An abbreviated version of this manuscript was given to all participants upon completion of this research. Participants were invited to make any comments on this study, prior to submission for review. Subsequently, no responses were received from families following the dissemination of the findings to participants, apart from one family. This family reported that they had participated in several pieces of autism research and revealed that this research was the first time that they received a report on the findings.

Analysis

A constructivist, interpretivist paradigm, adhering to a relativist position, was adopted for this research. According to Ponterotto (2005, p. 129), constructivist-interpretivists posit that “reality is constructed in the mind of the individual …where meaning is hidden and brought to the surface through deep reflection”. This paradigm approaches human inquiry by “sharing the goals of understanding the complex world of lived experiences from the point of view of those who live it” (Schwandt 1998, p. 221). The family systems approach in this study explored the emic perspectives of parents and grandparents on how the role of grandparents impacted on families who have a child with ASD. Constructivist interpretivists propose that to understand the world of meaning, one must interpret it (Schwandt 1998).

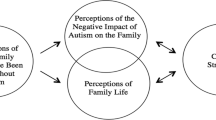

Thematic analysis was selected to analyse and to interpret these interviews, driven by a theoretical and analytical interest (Braun and Clarke 2006) in family systems theory. Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase guide was used as a framework for analysis. Firstly, the interview data were transcribed and the content was read and re-read. Secondly, units of text were coded for initial basic themes that emerged using a colour coding technique thereby identifying the data set. The data was grouped together and given provisional titles. Data was cross validated by the second author. Thirdly, the data set was read, discussed and reflected upon. Family systems theory was consulted at this stage to support emerging themes as “thematic analysis at the latent level goes beyond semantic content of the data, and starts to identify underlying ideas assumptions and conceptualisations” (Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 84). Following this process, emerging themes were cross validated by both authors once again. Fourthly, more meaningful themes were identified with a thematic map of the analysis and were interpreted in terms of themes that overlapped with both parent and grandparent experiences to reflect the interactions in both subsystems from family system perspective. This phase was completed using mind mapping software.

Results

The following themes were identified from an in-depth analysis of the interview transcripts. Focusing on the roles of grandparents in families of children with ASD from a family systems perspective, capturing the perspectives of parents and grandparents on the grandparental role, three key themes were identified following a theoretical thematic analysis: (i) Family recalibrating; (ii) Strengthening the family system; and (iii) Current needs and future concerns of grandparents, outlined in Table 2.

Family Recalibrating

Parents and grandparents reported on the changing roles of grandparents in meeting the needs of a child with ASD within their respective families. Changes in grandparents’ roles were particularly salient during times of stress resulting in families making adaptations to their lives and “recalibrating”. Specifically, family members’ roles changed to meet the needs of the child with ASD. All grandparents reported that they were impacted by the social isolation they experienced as a grandparent of a child with autism. Specifically, their perceived isolation emerged as a result of their reported perceptions of what both grandparents and parents envisaged for grandparents’ retirement years. This lead to tensions in families that were affected by mental health issues disclosed in several families. Despite these perceived limitations, the general consensus was that families adjusted to their lives with an autistic child. The subthemes identified were “limiting life” and “impact on family”.

Limiting Life

Eight of the nine families disclosed the limiting effects on their families’ lives as a result of having a child with ASD in their family. For grandparents in seven families, their roles included care giving and providing respite for the child. For two families, the grandparents’ role included supporting a parent where marital break-up occurred, thereby increasing their supportive role. In one family, a grandmother had a caregiver role despite having her own health difficulties. Her daughter reported:

my mother was so good,when I was having very hard nights I would ring her and she would say bring him up… So I’ve been very grateful to my Mum, she has been sick her whole life and she shouldn’t be here at all, she has been and unbelievable amount of strength and support to me she is the main person. [Lucy; mother; 65–72]

For four families, grandparents’ lives changed as a result of adopting a care role for their grandchild with ASD within their respective families. One grandmother commented:

I looked after him from the beginning, I volunteered but my life changed an awful lot, because I used to play pitch and putt every day, and I would be free, I used to enjoy it immensely and after [child’s name] being diagnosed I was under pressure then. [Catherine; grandmother; 165–169]

Conversely, one mother of two children with ASD reported that grandparents opted to maintain the plan they had for their retirement years and to play a less supportive role in their family than their children had possibly anticipated:

even though they live close…we might not see them for two weeks sometimes, they are not going to be tied down with grandchildren. [Brenda; mother; 1316–1320]

Impact on Family

For many families, having a child with ASD in the family impacted on the role of grandparents, particularly as they were often the first to express concerns about their grandchild’s development. Specifically, in five families, grandparents were the first to disclose their initial concerns.

he was fine until about two years of age and then he started one day with this big flow of gobblydegook and something struck me so I said to [child’s mother], I don’t like this so from there she just took him to the doctors and specialists. [Fiona; grandmother; 142–145]

In seven families, grandparents had the role of informing their extended family about their grandchild’s diagnosis of ASD.

I suppose like a typical Irish family you tell your parents and they become the messengers then for everybody else and that’s the way it would have been I suppose. [John and Jill; parents; 493–495]

Five out of nine mothers revealed that their son or daughter with ASD brought families closer together, where they developed a closer relationship with their mothers resulting in role confusion. The traditionally defined roles in a mother-daughter dyad were blurred in all families where the grandmother was identified as a very close friend on whom the mother was dependent:

yeah we would be close,her youngest daughter was saying why are you and nana like friends instead of mammy and daughter?. [Margaret; grandmother; 556–558]

Mental health issues affected two families. In one family, a mother was hospitalised and grandparents took over the role as main caregivers:

she had a nervous breakdown, with her personal problems it is very difficult for her to have a child so severe, she is trying herself to cope, there at times and it’s difficult, and I think we could give her a bit more support. [Simon and Lorraine; grandparents; 330; 397–403]

Strengthening the Family System

Grandparents had a role to play in strengthening the family system. The ability of a family to adjust its equilibrium, or homeostasis, when a child in the family has ASD was supported by grandparents. This theme included planning that was required to meet the needs of a child; how a family was strengthened by prior experiences of special education needs; and the variations in roles played by paternal and maternal grandparents. The role of the grandfather was significant also. The subthemes that emerged from analysis included: “the active role of grandparents” and “calming role of grandfather”.

The Active Role of Grandparents

The active roles of grandparents were reported in eight of the nine families in this study. In four families, having previous experience of special education needs, either through work contexts or family experiences, supported grandparents. Grandparents were active in the lives of their families in a number of ways that was informed, in some instances, of previous active experiences of engaging with individuals with special education needs. Grandparents were also active in a care role for children that including providing respite. Maternal grandparents, particularly grandmothers, were identified as more active than paternal grandparents. In six families, grandparents provided respite for parents by caring for their grandchild:

The odd time now she would get bad, you know have a tantrum and we would be all, kind of, getting stressed, and I’d be saying I’ll take her out and Mam would take her. [Marie; mother; 810–813]

Seven families revealed their dependence on grandparental support:

he was over there last night for a sleep over, yeah he loves going to nana’s and granda’s house for a sleep over, I suppose we have become more dependent on them really. [Jill; mother; 582–583; 587]

A variation in the role played by paternal and maternal grandmothers emerged from analysis. Specifically, in six families, maternal grandparents, and in particular grandmothers, were more actively involved in supporting families than paternal grandparents. A paternal grandmother commented:

we wouldn’t really be hands on grandparents. I wouldn’t be a hands on grandmother, but I always think that the girl goes home to her mother when there is anything wrong. [Teresa; grandmother; 48–50]

Three parents expressed their concern that having a grandchild with ASD was a burden to grandparents:

it’s hard for her to mind him ‘cause she is on her own, I always feel we try not to ask her too much to mind him but he adores her so much, and she has so much time and patience with him. [Monica; mother; 472–475]

Calming Role of Grandfather

The participation of grandfathers within the family system was explicitly discussed in eight families. Inputs on the role of the grandfather were enhanced in this study from interviews that were completed with two grandfathers individually and joint interviews alongside grandmothers in three other instances. In two families, grandfathers had the role of father figure in instances where marital break-up had occurred and where a grandchild’s father had little or no role in the child’s life:

with him being without a Dad, there was an extra responsibility on me by just playing the role of a Dad. [Simon; grandfather; 122–123].

In all eight families, the role of the grandfather was overwhelmingly positive. The calming influence of a grandfather was particularly salient in three families where a grandchild with ASD had significant behavioural difficulties.

she would start having a tantrum over something, but my Dad would be ‘no way we don’t do that here’ and that’s it you know, he is very kind and very calm, he’s just the same all the time. [Marie; mother; 307–312]

In four families, a distinctive bond between a grandfather and child with ASD was also disclosed:

my father idolised him since the day he was born, there was just something between the two of them, they have a bond, he would say if [child’s name] isn’t going then no one is going. [Jill; mother; 738–740; 758]

Current Needs and Future Concerns of Grandparents

Respondents identified the current needs of grandparents that are impeding their participation within their respective family currently, and potentially into the future. Families identified challenges that emerged during points of transition and the need to have grandparents’ roles acknowledged by professionals. Grandparents raised concerns regarding the challenges of limited supports and the resources that are required to effectively meet the needs of their grandchild. Parents and grandparents expressed their concerns about grandparents’ reduced ability to meet families’ needs into the future, particularly relating to the burden that a child with ASD may have on their families when grandparents are no longer in a position to support them. The two main subthemes identified were “needs of grandparents” and “concerns for future”.

Needs of Grandparents

All participants unanimously stated that clinicians, who give multidisciplinary support to families of children with autism, should acknowledge the role grandparents play in supporting families. Eight families suggested that families should have the option of whether they wanted grandparents to be involved formally at some level. They reported that they did not consider this intrusive. Two families commented that taking part in this research was beneficial for their families:

now it doesn’t happen that it’s explained to grandparents,you’re there now having a one-to-one with us and that’s the first time anyone has ever spoken to us about it,that’s right, the first time, there needs to be more of the likes of you [the researcher] now doing this and going around meeting grandparents. [Peter and Ruth; grandparents; 1462–1468; 1474–1475]

Actually, I thought even doing this [research] was probably going to be a support to them. [Sarah; mother; 889]

The lack of education on ASD impacted on the grandparents’ potential to be more active in supporting their grandchild with autism. The majority of participants perceived this lack of knowledge as impeding on grandparents’ potential contribution to their respective families:

I don’t think it is an intrusion, I think the offer should be there, if the parents and grandparents get on with each other, I think if grandparents were brought into the picture from day one, then maybe they could help them a lot better because they could understand it [ASD] a lot better and, you see, some grandparents I suppose find it hard to understand. [Margaret; grandmother; 852–859]

For one grandparent, having greater knowledge may have increased her participation in supporting her family and may have reduced the burden of guilt she was experiencing:

If I had known more, I would have been able to do more and not feel as guilty as I do now. [Teresa; grandmother; 828–829]

Concerns for Future

In three families, grandparents played a supportive role. In five families, parents disclosed that they were heavily reliant on grandparents for support. The grandparents and the parents all expressed their concerns for the future when grandparents would no longer be available to play an active role and when an autistic child might become an increasing burden on the family.

the biggest worry that we have is we won’t be there for him you now and how will she cope with [child’s name] but it’s the future that’s the problem. [Simon and Lorraine; grandparents; 142–144; 148]

One grandmother disclosed her concern about her inability to play an active role in the future life of her grandchild.

I fear when he gets bigger and strong and I go the other way that I won’t be able to do enough for him which I want to do you know. [Sandra; grandmother; 515–516]

Discussion

This study explored the role of grandparents in supporting families of children with ASD from a family systems perspective. Both parents and grandparents shared their experiences of the roles grandparents played in their respective families. The results of this study reveal the vital and largely unacknowledged role that grandparents play in supporting families of children with ASD (Hastings 1997) and the need for grandparents to obtain additional supports to enhance their role (Hillman 2007). The theme of “strengthening the family system” is consistent with previous findings that identified closer bonds existing in families of children with ASD (Hillman et al. 2016, 2017; Miller et al. 2012; Kayfitz et al. 2010; Margetts et al. 2006). Barnett et al. (2010) suggest that the transition to motherhood, a shared experience, strengthens the mother daughter dyad. This caused role confusion between two of the mothers and daughters in this study. While the experience of role confusion within this dyad is consistent with Hillman’s (2007) findings, this was not an additional stressor in the families who participated in this study. Further research could explore the implications of closer bonds in each subsystem within families using a family systems approach. Conversely, not all families experienced closer bonds. The less active role of paternal grandparents revealed here is consistent with previous research (Glasberg and Harris 1997).

The “calming role of grandfather” is important, as it acknowledges the role that grandfathers played in providing behavioural supports to children. While this may be a cultural feature of the Irish family, it certainly warrants further exploration, particularly regarding how a child with ASD gravitates towards the calm temperament of the grandfathers, as revealed in this study. Few studies have addressed men’s experiences as grandfathers. Recent research has started to examine grandfathers’ interactions with their grandchildren (Stelle et al. 2013). This suggests that grandfathers have a more significant role in families than previously acknowledged, as they are frequently absent from research. Grandfathers’ perspectives should be considered more in research, particularly research on families of children with special education needs.

In two of nine families where marital break-up occurred, mothers relied significantly on grandparental support. This is consistent with research in Ireland that indicates that one in four children in Ireland live in families outside the ‘traditional model’ (Lunn and Fahey 2011). Grandfathers had the role of father figure in these families. Interestingly, Freedman et al. (2011) revealed, in data taken from a population-based cross-sectional National Survey of Children’s Health in the United States that the stress placed on families of a child with ASD has no effect on the family structure and family break-up does not occur more often than in other families. Additionally, these findings indicate that there is no evidence that a child with ASD is at an increased risk when living in a household not composed of the traditional family dyad consisting of a married father and mother. A worrying aspect here is how families of children with ASD cope when the support of grandparents is no longer available to them. Grandparents expressed their concerns about the functioning of families in the future, particularly given their own declining health and physical abilities as they got older (Miller at al. 2012).

The impact of mental health difficulties on families was disclosed in interviews. Research has revealed that interventions are needed that target parent, child and family characteristics in order to better enhance parents’ day to day functioning in the context of ASD (Pruitt et al. 2016). In one family, grandparents took over the care role of a child with ASD when the mother was hospitalised, despite this grandmother having her own considerable health difficulties. How this family, and other families with mental health difficulties, will manage in the longer term is a cause for concern. The impact of mental health difficulties in children with ASD is a further cause for concern (Ratcliffe et al. 2015), particularly how these issues can impact on the wider family system. Daniels et al. (2008) reported that parents of children with ASD were more likely to have been hospitalised for a mental health difficulty than parents of control subjects in a large epidemiological study in Sweden. Recent research has identified grandparents’ resilience and reports of the transformative experience of having a child with ASD in the family (Hillman et al. 2016). The findings here highlight the importance of developing resilience skills in families and exploring the possibility of developing supports within other subsystems in families, including the extended family. Ooi et al. (2016) recommended that health care provision should be family centred to address the needs of the whole family, not just the affected child, to guard a family’s well being and quality of life.

Implications for Professionals

There are several implications for clinicians that have emerged from this study. Families overwhelming articulated the need for professionals to acknowledge grandparents’ roles in supporting families of children with autism. This is consistent with the view that grandparents are an important but unrecognised and under-utilised resource in families (Seligman and Darling 2007). Family focused ASD research is necessary for increasing our understanding of ASD and to identify suitable clinical support services for families (Cridland et al. 2014). King et al. (2009) suggest that it is imperative for service providers to appreciate the capacity of families of children with disabilities to adapt, to develop a sense of meaning and purpose, and to ascribe positive meaning to life events. Recent research has identified that a family centred case management model can have a positive impact on the health and wellness of families with children who have disabilities (Brown et al. 2017). Professionals should continue to recognise the value of supporting all family members in relation to their family unit (Langley et al. 2017; Turnbull et al. 2012).

Furthermore, research suggests that a systems based approach is utilised in the assessment of children with developmental disabilities (Head and Abbeduto 2007; Hillman 2007; Margetts et al. 2006) and this is worthy of further consideration. Interventions must recognise and plan around the complexities in relationships that exist between grandparents and grandchildren to support and empower grandparents in unique and diverse situations (Stelle et al. 2013). To ensure their contribution is positive, grandparents would benefit from more psycho-educational supports and information on their grandchild’s autism, to enable them to give meaningful support to families. Clinicians have the potential to empower grandparents by better informing them, with parental consent, of their grandchild’s needs specific to autism. Research has identified that tailoring services to best meet families’ needs could improve the quality of life of families and decrease the burden on care systems (Hodgetts et al. 2015). Without accurate information about their grandchild’s particular needs, grandparents who want to help their grandchild with ASD, and their son or daughter, feel helpless in their role (Sullivan et al. 2012) and this can affect their wellbeing (Kim et al. 2017). Additionally, research has suggested tailoring parenting programmes to support grandparents when they look after their grandchildren (Kirby and Sanders 2012). This manuscript identifies that a specific training programme is required to inform grandparents of their grandchild’s autism, using a family systems approach.

Caution is advised where professionals need to be mindful of the impact disability may have on grandparents, as they can experience distress at the news of their grandchild’s disability (Hastings 1997) where some grandparents previously reported feelings of despair and helplessness (Hillman et al. 2017). Many grandparents have a very active role in the lives of their grandchildren with autism. However, families have to consider how they will need to adapt to a future where grandparents are not available to play such an active role in their family’s lives (Miller et al. 2012). This has implications for future planning in families who have children with autism. Involving grandparents in a circle of support for their grandchild may allow them to play a more active role in the life of their grandchild. This could allow grandparents the option of taking a less active role when the need arises without the impact of their support no longer being available to meet families’ needs.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has a number of strengths: firstly, it included respondents from within two subsystems of families who gave input on the roles of grandparents in families. A family systems approach enriched findings here by revealing how grandparents’ roles were perceived not only by grandparents themselves, but by parents also. Secondly, the variety of participants enriched findings, particularly the inclusion of grandfathers who are often absent from research on families. Thirdly, the age range of both parents and grandparents captured multiple generational experiences of how grandparents’ roles were perceived, particularly when family systems approaches recognise the fluctuating nature of family functioning (Cridland et al. 2014). This research captured experiences of families of children with ASD from 5 to 18 years of age, capturing a trajectory of how family systems adjust to the needs of a developing child with ASD over time. This study revealed that the needs of children remained high regardless of age suggesting that family supports are required throughout the lifespan of the family member with autism. Fourthly, of note, is the revelation of the valuable role a grandfather plays in the life of a child with autism. Future research could investigate the roles of grandfathers of children with ASD compared to grandfathers of other neuro-diverse children or typically developing children. This study provided a qualitative snapshot of Irish families of children with ASD captured at a moment in time. Research has recognised that families’ needs in ASD are often consistent across jurisdictional boundaries (Hodgetts et al. 2015) lending strength to the richness of qualitative data on family experiences of ASD gathered in this study. Researchers have called for qualitative, family systems research that captures the idiographic, multifaceted issues that are present in families (Cridland et al. 2014). This paper responds to this call and provides an insight into the complexities that arises in families that is not always captured in large data sets.

Conversely, this study is not without limitations: firstly, the participants were those who professed an interest in this area by their participation and, therefore, are possibly not the experiences of other families. Secondly, participants were limited to Caucasian, Irish families and are not reflective of recent demographic changes in Irish families. This is possibly due to the challenges that can arise from recruiting participants for research from ethnic minorities (Waheed et al. 2015). Thirdly, one interview may not have captured the whole experiences of families, as one-shot interviews may diminish the potential to produce rich descriptions for worthwhile findings (Polkinghorne 2005). Fourthly, the use of triangulation, using quantitative methods, would have enhanced findings here, perhaps even capturing the perspectives of children themselves (Schlebusch and Dada 2018), using a participatory approach (Pellicano et al. 2013, 2014). Finally, the majority of participants had a child/grandchild who attended special schooling and also had an ID, implying that their needs, and the need to involve grandparents, were possibly greater than those of children with ASD who attend mainstream schooling. Therefore, interpretations on the generalisability of grandparents’ roles in families of children with ASD are thus limited. This study would have benefited from the inclusion of more families who have children with ASD in mainstream education to explore whether grandparents’ roles differed depending on the level of a child’s functioning. Furthermore, it is possible that all families may not have similar positive experiences. It is also plausible that families with more negative experiences of grandparents’ roles would not participate in this type of study.

Additionally, grandparent psychological well being was not explored in this research. There is a dearth of research on grandparents who look after their grandchild (Kim et al. 2017). Religious supports are identified in research as a positive support mechanism for families of children with ASD (Habib et al. 2017; Hillman et al. 2016; Divan et al. 2012; King et al. 2009). Interestingly, the role of religion as a protective factor for grandparents, in supporting families of children with ASD, did not emerge in this research particularly when it is identified as a factor in providing meaningful contact between grandparent and grandchild (King et al. 2008). Future research could explore the impact of culture and religious beliefs from multigenerational and multicultural perspectives on families with children who have autism, particularly in instances where there is a potential for these factors to impact on grandparent well being, thereby possibly impacting on their role.

Conclusion

Grandparents of children with ASD provide supports, not only to the children themselves, but also to their son or daughter whose child has autism. To reduce the burden families can experience, they would benefit from a family systems approach to empower grandparents to respond proactively to the needs of the family. It is incumbent upon professionals to devise supports to meet this need and to give recognition to grandparents of the valuable role they play. This research is a rallying call to professionals to consider the roles of grandparents more formally in their interactions with families of children with autism, and to identify supports to meet grandparents’ needs that ultimately improve the functioning of the family system.

References

Ayvazoglu, N. R., Kozub, F. M., Butera, G., & Murray, M. J. (2015). Determinants and challenges in physical activity participation in families with children with high functioning autism spectrum disorder from a family systems perspective. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 47, 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2015.08.015.

Barnett, M. A., Scaramella, L. V., Neppl, T. K., Ontai, L. L., & Conger, R. D. (2010). Intergenerational relationship quality, gender and grandparents involvement. Family Relations, 59(1), 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2009.00584.x.

Benson, P. R., & Karlof, K. L. (2009). Anger, stress proliferation, and depressed mood among parents of children with ASD: A longitudinal replication. Journal of Autism Developmental Disorders, 39, 350–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0632-0.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Broady, T. R., Stoyles, G. J., & Morse, C. (2017). Understanding carers’ lived experience of stigma: The voice of families with a child on the autism spectrum. Health and Social Care in the Community, 25(1), 224–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12297.

Brown, K., Churchill, V., Laghaie, E., Ali, F., Fareed, S., & Immergluck, L. (2017). Grandparents raising grandchild with disabilities: Assessing health status, home environment and impact of a family support case management model. International Public Health Journal, 9(2), 181–188.

Canary, H. (2008). Creating supportive connections: A decade of research on support for families of children with disabilities. Health Communication, 23(5), 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410230802342085.

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01259.

Cridland, E. K., Jones, S. C., Magee, C. A., & Caputi, P. (2014). Family-focused autism spectrum disorder research: A review of the utility of family systems approaches. Autism, 18, 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361312472261.

Daniels, J. L., Forssen, U., Hiltman, C. M., Cnattingius, S., Savitz, D. A., Feychting, M., & Sparen, P. (2008). Parental psychiatric disorders associated with autism spectrum disorders in the offspring. Pediatrics, 121(5), 1162–1357. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-2296.

Divan, G., Vajartkar, V., Desai, M. U., Strik-Lievers, L., & Patel, V. (2012). Challenges, coping strategies, and unmet needs of families with a child with autism spectrum disorder in Goa, India. Autism Research, 5, 190–200. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1225.

Farrugia, D. (2009). Exploring stigma: Medical knowledge and the stigmatisation of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Sociology of Health and Illness, 31(7), 1011–1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01174.x.

Freedman, B. H., Kalb, L. G., Zablotsky, B., & Stuart, E. A. (2011). Relationship status among parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A population-based study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1269-y.

Galvin, K. M., Dickson, F. C., & Marrow, S. R. (2005). Systems theory: Patterns and (w)holes in family communication. In D. Braithwaite & L. A. Baxter (Eds.), Engaging theories in family communication: Multiple perspectives (pp. 309–324). Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Gau, S. S., Chou, M., Chiang, H., Lee, J., Wong, C., Chou, W., et al. (2011). Parental adjustment, marital relationship, and family function in families of children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 263–270.

Glasberg, B. A., & Harris, S. L. (1997). Grandparents and parents assess the development of their child with autism. Child and Family Behaviour Therapy, 19(2), 17–27.

Habib, A., Prendeville, P., Abdussabur, A., & Kinsella, W. (2017). Pakistani mothers’ experiences of parenting a child with autism spectrum disorder in Ireland. Educational and Child Psychology, 34(2), 67–79.

Harper, A., Taylor Dyches, T., Harper, J., Olsen Roper, S., & South, M. (2013). Respite care, marital quality, and stress in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Development Disorders, 43, 2604–2616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1812-0.

Hastings, R. (1997). Grandparents of children with disabilities: A review. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 44(4), 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/0156655970440404.

Head, L. S., & Abbeduto, L. (2007). Recognising the role of parents in developmental outcomes: A systems approach to evaluating the child with developmental disabilities. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13, 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrdd.20169.

Hillman, J. (2007). Grandparents of children with autism: A review with recommendations for education, practice and policy. Educational Gerontology, 33(6), 513–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270701328425.

Hillman, J., Marvin, A. R., & Anderson, C. M. (2016). The experience, contributions, and resilence of grandparents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 14(2), 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2016.1160727.

Hillman, J. L., Wentzel, M. C., & Anderson, C. M. (2017). Grandparents’ experience of autism spectrum disorder: Identifying primary themes and needs. Journal of Autism and Development Disorders, 47, 2957–2968. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3211-4.

Hodgetts, S., Zwaigenbaum, L., & Nicholas, D. (2015). Profile and predictors of service needs for families of children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 19(6), 673–683. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314543531.

Johnson, N., Freen, M., Feetham, S., & Simpson, P. (2011). Autism spectrum disorder: Parenting stress, family functioning and health-related quality of life. Families, Systems, and Health, 29(3), 232–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025341.

Kahana, E., Lee, J. E., Kahana, J., Goler, T., Kahana, B., Shick, S., et al. (2015). Childhood autism and proactive family coping: Intergenerational perspectives. Journal of Intergenerational Relationship, 13(2), 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2015.1026759.

Kayfitz, A. D., Gragg, M. N., & Orr, R. R. (2010). Positive experiences of mothers and fathers of children with autism. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 23(4), 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2009.00539.x.

Kazak, A. E., Rourke, M. T., & Navsaria, N. (2009). Families and other systems in pediatric psychology. In M. C. Roberts & R. G. Steele (Eds.), Handbook of pediatric psychology. New York: Guildford Press.

Kim, H. J., Kang, H., & Johnston-Motoyana, M. (2017). The psychological well being of grandparents who provide supplementary grandchild care: A systematic review. Journal of Family Studies, 1, 118–141.

King, G., Baxter, D., Rosenbaum, P., Zwaigenbaum, L., & Bates, A. (2009). Belief systems of families of children with autism spectrum disorders or Down syndrome. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(1), 50–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357608329173.

King, S. V., Burgess, E. O., Akinyela, M., Counts-Spriggs, M., & Parker, N. (2008). The religious dimensions of the grandparent role in three-generation African American households. Journal of Religion, Spirituality and Aging, 19(1), 75–96.

Kirby, J. N., & Sanders, M. R. (2012). Using consumer input to tailor evidence-based parenting intervention to the needs of grandparents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21, 626–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-011-9514-8.

Langley, E., Totsika, V., & Hastings, R. P. (2017). Parental relationship satisfaction in families of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A multilevel analysis. Autism Research, 10, 1259–1268. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1773.

Lunn, P., & Fahey, T. (2011). Households and family structures in Ireland-A detailed statistical analysis of Census 2006. Dublin: Economic & Social Research Institute.

Margetts, J. K., Le Couteur, A., & Croom, S. (2006). Families in a state of flux: The experience of grandparents in autism spectrum disorder. Child: Care, Health and Development, 32(5), 565–574. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00671.x.

Markoulaksis, R., Flectcher, P., & Bryden, P. (2012). Seeing the glass half full-benefits to the lived experiences of female primary caregivers of children with autism. Clinical Nurse Specialist. https://doi.org/10.1097/NUR.0b013e31823bfb0f.

Miller, E., Buys, L., & Woodbridge, S. (2012). Impact of disability on families: Grandparents’ perspectives. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 56(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01403.x.

Minuchin, P. (1988). Relationships within a family: A systems perspective on development. In R. A. Hinde & J. Stevenson-Hinde (Eds.), Relationships within families: Mutual influences. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Mouzourou, C., Milagros-Santos, R., & Gaffney, J. S. (2011). At home with disability: One family’s three generations narrate autism. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 24(6), 693–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2010.529841.

Myers, B. J., Mackintosh, V. H., & Goin-Kochel, R. P. (2009). My greatest joy and my greatest heartache”: Parents own words on how having a child in the autism spectrum has affected their lives and their families’ lives. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3, 670–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2009.01.004.

Neely-Barnes, S. L., & Dia, D. A. (2008). Families of children with disabilities: A review of literature and recommendations for interventions. Journal of Intensive Behaviour Intervention, 5(3), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0100425.

Ooi, K. L., Ong, Y. S., Jacob, A. A., & Khan, T. M. (2016). A meta-synthesis on parenting a child with autism. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 1–18.

Pellicano, E., Dinsmore, A., & Charman, T. (2013). A future made together: Shaping Autism research in the UK. London: Institute of Education.

Pellicano, E., Dinsmore, A., & Charman, T. (2014). What should autism research focus upon? Community view and priorities from the UK. Autism, 18, 756–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314529627.

Polkinghorne, D. E. (2005). Language and meaning: Data collection in qualitative research. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 52(2), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.137.

Ponterotto, J. G. (2005). Qualitative research in counselling psychology: A primer on research paradigms and philosophy of science. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 52(2), 126–136.

Potter, C. A. (2016). ‘I accept my son for who he is-he has incredible character and personality’: Fathers’ positive experiences of parenting children with autism. Disability & Society, 31(7), 948–965. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2016.1216393.

Pruitt, M. M., Willis, K., Timmons, L., & Ekas, N. V. (2016). The impact of maternal, child, and family characteristics on the daily well-being and parenting experiences of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 20(8), 973–985. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315620409.

Ratcliffe, B., Wong, M., Dossetor, D., & Hayes, S. (2015). The association between social skills and mental health in school-age children with autism spectrum disorder, with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 45, 2487–2496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2411-z.

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., et al. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality and Qunatity, 52, 1893–1907.

Schlebusch, L., & Dada, S. (2018). Positive and negative cognitive appraisal of the impact of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorder, 51, 86–93.

Schwandt, T. A. (1998). Constructivist, interpretivist approaches to human inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The landscape of qualitative research: Theories and issues. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Seligman, M., & Darling, R. B. (2007). Ordinary families, special children: A systems approach to childhood disability. New York: The Guildford Press.

Stelle, C., Fruhauf, C. A., Orel, N., & Landry-Meyer, L. (2013). Grandparenting in the 21st century: Issues of diversity in grandparent-grandchild relationships. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 53(8), 682–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2010.516804.

Stuart, M., & McGrew, J. H. (2009). Caregiver burden after receiving a diagnosis of an autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(1), 86–97.

Sullivan, A., Winograd, G., Verkuilen, J., & Fish, M. C. (2012). Children on the autism spectrum: Grandmother involvement and family functioning. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 25, 484–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2012.00695.x.

Timmons, L., Ekas, N. V., & Johnson, P. (2017). Thankful thinking: A thematic analysis of gratitude letters by mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 34, 19–27.

Turnbull, A. P., Turnbull, H. R., Wehmeyer, M. L., & Shogren, K. A. (2012). Exceptional lives: Special education in today’s schools. New York: Pearson.

Waheed, W., Woodham, A., Parker, A., Allen, G., & Bower, P. (2015). Overcoming barriers to recruiting ethnic minorities to mental health research: A typology of recruitment strategies. BMC Psychiatry, 15(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0484-z.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the families who generously took time to share their experiences. The authors acknowledge the support of Geraldine Bond and Mary Fitzgerald, both in the Brothers of Charity Cork, who assisted in the preparation of this research. This paper was completed following the submission of a Masters dissertation by the first author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PP conceived this study. She designed, coordinated, completed and analysed interviews. She also drafted the manuscript. WK supervised the design of this research. He reviewed interview analysis for consistency and assisted in the draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author A declares that she has no conflict of interest. Author B declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee to which the authors are affiliated, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its amendments.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Prendeville, P., Kinsella, W. The Role of Grandparents in Supporting Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Family Systems Approach. J Autism Dev Disord 49, 738–749 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3753-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3753-0