Abstract

We investigated the presentation and correlates of hoarding behaviors in 204 children aged 7–13 with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and comorbid anxiety or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms. Approximately 34% of the sample presented at least moderate levels, and with 7% presenting severe to extreme levels of hoarding. Child gender predicted hoarding severity. In addition, child ASD-related social difficulties together with attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder symptom severity positively predicted hoarding controlling for child gender and restricted and repetitive behaviors. Finally, child anxiety/OCD symptoms positively predicted hoarding, controlling for all other factors. These results suggest hoarding behaviors may constitute a common feature of pediatric ASD with comorbid anxiety/OCD, particularly in girls and children with greater social difficulties and comorbid psychiatric symptom severity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by deficits in social communication as well as restricted and repetitive interests, activities, and behaviors (American Psychiatric Association (APA) 2013). ASD affects approximately 1–1.5% of children (Baio 2012; CDC 2014; Kogan et al. 2009) and is commonly associated with comorbid psychiatric disorders, with the most common being anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD), which have prevalence rates as high as 56% in the ASD population (Leyfer et al. 2006; Mattila et al. 2010; White et al. 2009).

There is preliminary evidence that ASD may be associated with hoarding behaviors. Hoarding is defined as a persistent incapacity or failure to discard possessions independently of their value, leading to debilitating clutter (American Psychiatric Association (APA) 2013), with a subset of individuals also exhibiting excessive acquisition of objects (Frost et al. 2009). In youth, however, excessive clutter is not a highly common feature and, when present, it is typically restricted to the youth’s bedroom (Storch et al. 2016). Most research on the prevalence of pathologic hoarding has focused on adults, with prevalence rates of 1.5–5.8% reported in community samples (Nordsletten and Mataix-Cols 2012; Nordsletten et al. 2013; Timpano et al. 2011). Although limited data exist in youth, a recent study in a large community sample of children and adolescents aged 6–17 years indicated that 8.9% of the sample presented with elevated hoarding symptoms (Burton et al. 2016). Slightly higher prevalence of hoarding behaviors has been reported in females relative to males (Burton et al. 2016; Ivanov et al. 2013; Testa et al. 2011; Wheaton et al. 2008), whereas age has not appeared to be related to hoarding in neurotypical children and adolescents (Burton et al. 2016).

In youth aged 4–17 years with ASD, the endorsement of hoarding behaviors may be as high as 24.3% (Scahill et al. 2014), suggesting hoarding may be particularly prevalent in this population. Hence, studies in both adults and youths have demonstrated a higher frequency of hoarding symptoms in individuals with ASD relative to typically developing individuals (Bejerot 2007; Cadman et al. 2015; McDougle et al. 1995; Pertusa et al. 2012; Russell et al. 2005; Ruta et al. 2010).

Different arguments have been advanced to explain the occurrence of hoarding symptoms in ASD. Individuals with ASD often experience intense and restricted interests, which may lead them to acquire and collect items (Pertusa et al. 2012). Individuals with ASD also share various psychosocial characteristics with other individuals who hoard (Zaboski and Storch 2017), including excessive attachment to objects, social isolation, and impairments in theory of mind (Grisham et al. 2008; Pertusa et al. 2012). These characteristics may be related to difficulties in discarding items or to a lack of insight regarding problematic aspects of hoarding behaviors.

Another common feature to individuals with hoarding disorders and individuals with ASD is the co-occurrence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and associated executive functioning deficits. Indeed, both hoarding and ASD have been linked with elevated comorbidity rates of aADHD (Antshel et al. 2013; Frost et al. 2011). Attention and executive deficits shared by these populations include difficulties in attention shifting, self-regulation, planning, and organizing (Geurts et al. 2004; Gilotty et al. 2002; Hill 2004; Olley et al. 2007; Woody et al. 2014). These characteristics may be related to impulsive acquisition and difficulties in organizing and discarding objects (Storch et al. 2011).

In addition to these shared characteristics, the co-occurrence of anxiety disorders and OCD in ASD has also been suggested as a potential factor explaining the relationship between ASD and hoarding (Storch et al. 2016; Zaboski and Storch 2017), as hoarding symptoms have been associated with elevated anxiety levels in normative samples (LaSalle-Ricci et al. 2006). Anxiety disorders and OCD are often characterized by catastrophic worries and fears, which may lead to safety behaviors including acquisition of items (potentially a distraction from negative affect) and retention of possessions (a negatively reinforced behavior intended to prevent unwanted negative outcomes or feelings of loss) (Kim 2005; Sloan and Telch 2002; Wells et al. 1995). Hence, youth with ASD and comorbid anxiety/OCD disorders, who represent the majority of youth with ASD (Leyfer et al. 2006; Mattila et al. 2010; White et al. 2009), may be at greater risk of clinical hoarding symptoms.

Taken together, these findings suggest a close link between hoarding and anxiety symptoms in individuals with ASD. To our knowledge, however, only one study to date has examined hoarding symptoms in youth with ASD and comorbid anxiety or OCD. In that study, Storch et al. (2016) assessed the prevalence and correlates of hoarding symptoms in 40 children and adolescents with ASD undergoing cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for anxiety/OCD. Among the sample, 27.5% of youths presented with high parent-reported hoarding symptoms, with more than 25% presenting at least modest difficulty regarding various hoarding symptoms including room clutter, control over urges to acquire or save unneeded possessions, time spent dealing with possessions, and distress related to having a parent discard items. Overall, hoarding severity was positively associated with anxiety severity and was found to decrease following CBT. Interestingly, difficulties in discarding items were associated with anxiety (and depression) severity, whereas excessive acquisition was not. In addition, hoarding was also associated with greater internalizing and depression symptoms, externalizing behaviors, and attention difficulties. On the other hand, neither child age, nor social functioning was associated with hoarding severity, while potential links with child gender were not examined. These findings suggest a high prevalence of hoarding behaviors and provide initial evidence for associations of hoarding with different clinical features in children with ASD and anxiety disorders/OCD. However, studies are needed with larger samples of children and adolescents to build upon these findings.

In the present study, we examined hoarding behaviors in a sample of 204 children with ASD aged 7–13, who were also presenting with comorbid anxiety and/or OCD symptoms. This study builds on Storch et al.’s work (2016), by examining a large sample of carefully diagnosed children with high functioning ASD, recruited from three geographically distinct sites across the US. First, we examined the prevalence and presentation of hoarding behaviors, as well as the proportion of children presenting with clinically significant levels of hoarding. Next, we examined potential correlates (i.e., gender, ASD-related social difficulties and restricted and repetitive behaviors, ADHD symptoms, and anxiety/OCD symptoms) of overall and specific (i.e., acquisition, clutter, discarding, and distress/impairment) hoarding behaviors. Finally, we explored potential associations between hoarding behaviors and primary comorbid diagnosis as well as overall comorbid conditions. We expected a high prevalence of hoarding behaviors such that approximately 25% would present with at least moderate levels of hoarding (Storch et al. 2016). We hypothesized that overall hoarding severity would be positively associated with ASD-related restricted and repetitive behaviors and social difficulties severity, as well as ADHD and anxiety/OCD symptoms severity. We expected a higher prevalence of hoarding behaviors in girls relative to boys. Regarding specific subdomains of hoarding, we expected difficulties in discarding items to be positively associated with anxiety severity. In addition, we expected ASD-related social difficulties and restricted and repetitive behaviors to predict overall hoarding severity, controlling for child gender. We also expected ADHD symptoms severity to predict hoarding severity over and above gender and ASD symptoms, and anxiety severity to predict hoarding severity over and above other factors. We had no a priori hypothesis regarding associations with different comorbidity profiles.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

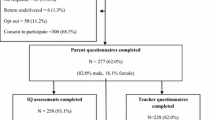

Participants were recruited at three research universities on the western and eastern coasts of the US, each in medium to large urban areas. Participants were drawn from anxiety/OCD treatment-seeking families being screened for potential enrollment in a multisite study examining psychotherapy for anxiety or OCD symptoms among youth with high functioning ASD (Kerns et al. 2016). To be included, participants had to be aged 7–13 years at consent and meet criteria for ASD as determined by scores from the Childhood Autism Rating Scale-Second Edition (Schopler et al. 2009), the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Second Edition (Lord et al. 2012), and a consensus among investigators across sites about the child’s diagnosis. Participants also had to have a Full Scale and Verbal Comprehension IQ > 70 as assessed on the WASI (Wechsler 1999) and to report the presence of anxiety or OCD symptoms.

In total, 213 children were screened for possible inclusion in the psychological treatment trial; 204 provided complete data regarding hoarding behaviors and were retained for the current analyses. Before the start of the program, all measures were administered to participants and their parents. All participants provided written consent (parents) and verbal assent (children) before completion of the study measures. Table 1 presents demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

Measures

Childhood Autism Rating Scale-Second Edition (CARS-2HF; Schopler et al. 2009)

The CARS-2HF is a 15-item clinician-administered diagnostic evaluation and direct observation measure of autism and autism severity. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = no evidence of difficulty, appropriate and normal, and 4 = severely abnormal. Total scores of 28 or above are considered as meeting criteria for ASD. The CARS-2HF has excellent validity and reliability (Schopler et al. 2009). Internal consistency was α = .84 in the present study.

Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-2; Lord et al. 2012)

The ADOS-2 is a structured observational assessment administered directly to the children to elicit social interaction and use of language, as well as repetitive and restricted behaviors and interests. Module 3 was administered to participants. Items are scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 2, with higher scores indicating higher difficulties. Scores are obtained for Social Affect and Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors subscales, as well as a Global scale. Scores on each scale are converted into comparison scores to determine diagnosis and severity. See Lord et al. (2012) for details on scores conversion and diagnostic criteria. In the present study, internal consistency was α = .75 for the overall scale, α = .81 for the social affect scale, and α = .42 for the repetitive and restrictive behaviors scale.

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule—Parent Version (ADIS-P; Silverman and Albano 1996) with Autism Spectrum Addendum (ASA; Kerns et al. 2017)

The ADIS-P/ASA is a semi-structured interview that assesses the presence of DSM-IV disorders in children, with an emphasis on anxiety disorders and OCD. The measure includes specific guidelines and items to support the differential diagnosis of ASD and anxiety symptoms and capture distinct and ambiguous anxiety symptoms (e.g. fears of change, worries about special interests, idiosyncratic phobias) that can arise in ASD. This measure provides a clinician severity rating (CSR) ranging from 0 (not at all) to 8 (very much) based on participant/parent report and diagnostician’s judgment. A CSR of 4 is required for a diagnosis. The ADIS-P/ASA has demonstrated reliability and validity in anxiety and OCD assessment among youth with ASD (Kendall et al. 2008; Kerns et al. 2017; Storch et al. 2012). The ADIS-P/ASA was used to determine main comorbid diagnosis (i.e. primary comorbid diagnosis) and all other comorbidities (i.e. overall comorbid diagnoses).

Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS; The Research Units On Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study (RUPP) 2002)

The PARS is a clinician-administered measure of the severity of various anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents integrating children’s and parent’s responses. The 6-item total score (excluding number of symptoms) was used. Items were scored on a 0 (none) to 5 (extreme) scale. The PARS possesses high test–retest reliability, inter-rater reliability, and good convergent and divergent validity (The Research Units On Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study (RUPP) 2002). Internal consistency was α = .75 in the present study.

Children’s Savings Inventory (CSI; Storch et al. 2011)

The CSI is a 20-item paper-and-pencil measure evaluating child hoarding behaviors, rated by parents. Items are rated on a scale ranging from 0 (none) to 4 (almost all/completely) and are divided into four subscales (Acquisition, Clutter, Discarding, and Distress/Impairment) as well as a Total score. Moderate severity is indicated by an average score of 2.0 (Storch et al. 2011, 2016). We also conceptualized severe levels as an average score of 3.0, indicating children adopted hoarding behaviors (Most/Much) and extreme as a score of 4.0 (almost all/Completely). The CSI has demonstrated strong internal consistency, as well as strong convergent and discriminant validity in typically developing youths (Storch et al. 2011), and has had excellent internal consistency in youths with ASD (Storch et al. 2016). Internal consistency for the Total scale was α = .92, α = .93 for the Discarding subscale, α = .88 for Acquisition, α = .87 for Clutter, and α = .76 for Distress and Impairment subscale.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach 2001)

The CBCL is a 118-item measure of parent perceptions of a child’s emotional and behavioral functioning over the last 6 months with sound psychometric properties (Achenbach 2001). Items are rated on a 0 (not true) to 2 (very true) scale. In the present study, we used the ADHD Problems subscale, which includes seven items assessing concentration and attention difficulties, hyperactivity, and executive dysfunction. Internal consistency was α = .73.

Statistical Analyses

We used SPSS 24 for statistical analyses. First, we used descriptive statistics including frequency counts, means, and standard deviations to examine the prevalence and presentation of hoarding behaviors (aim 1) as well as other clinical and demographic data. We examined patterns of missing values and excluded participants with over 20% of missing data on each measure from analyses in a pairwise manner. Patterns of significant missing data were as follows: 4.4% for ADOS, 2.5% for PARS, and 2.0% for CBCL ADHD problems subscale. Remaining missing data on individual items (< 20% of individual items on each measure) were replaced by the mean of the corresponding scale. Scores of all scales were normally distributed. To meet our second aim, we examined bivariate relationships between CSI and other study variables using Pearson correlations and point-serial correlations (for child gender). Child gender was dummy-coded with 0 indicating boys and 1 indicating girls. A hierarchical multiple regression was next computed to assess the predictive power of the different potential predictors of hoarding behaviors (CSI total) in four steps. First, we entered gender into the model to control for potential gender differences. Next, we entered the Social Affect and Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors scales of the ADOS. In a third step, we entered the CBCL ADHD subscale to assess the contribution of ADHD symptoms to hoarding severity over and above gender and ASD symptoms. We added PARS scores to assess the predictive role of anxiety over and above the other factors in a fourth step. Alpha was set at p value < .05 for multiple regression analysis. In addition, to meet aim 3, we assessed associations between the different overall comorbid diagnoses and hoarding behaviors using point-serial correlations; each possible diagnosis was dummy coded, with 0 indicating an absence of diagnosis and 1 indicating presence of diagnosis. One-way ANOVAs also compared children based on primary comorbid diagnosis to explore potential associations with hoarding for each subscale and total scale of the CSI. For each analysis, primary comorbid diagnosis (10 levels; i.e. generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobia, separation anxiety disorder, fear of/negative reactions to change, special interest fear, OCD, ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), or major depressive disorder) was entered as a between subject factor and hoarding severity as the dependent variable. The statistical threshold of significance was set at p value < .01 for correlation analyses and ANOVAs to correct for multiple comparisons.

Results

Presentation and Severity of Hoarding Behaviors

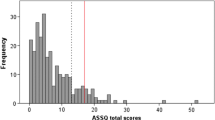

Overall levels of hoarding behaviors ranged from 3 to 75 out of 80 on the CSI scale, with a mean of 33.04 (SD = 16.93). Table 2 presents means and SDs, as well as the number and percentage of youths presenting moderate and severe-extreme levels for each item and subscale. Hoarding behaviors were highly prevalent among the sample, with 33.9% of youths presenting at least moderate overall levels. Moreover, 6.9% presented severe-extreme overall levels, indicating the presence of hoarding behaviors most of the time to almost always and much to complete endorsement of hoarding behaviors and associated difficulty. Over 30% of youths presented moderate to extreme levels of clutter, while more than 40% presented moderate to extreme difficulties in discarding items (representing 83.6% of those with significant clutter) and distress and impairment related to hoarding, as well as excessive acquisition of items. The item with the highest mean levels was having the room cluttered with possessions, with mean scores ranging from moderate to severe and 43.6% of the parents reporting severe-extreme levels.

Correlations Among Study Variables

All subscales and the total score of the CSI yielded significant positive correlations with child gender (at a trend level only for the Distress/Impairment scale), PARS scores, and CBCL ADHD Problems subscale (see Table 3). CSI scores were not correlated with ADOS Social Affect and Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors subscales. Correlations between the different potential predictors of the CSI scores did not exceed .60, suggesting low risks of multicollinearity.

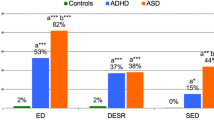

Multiple Regression Analyses

Table 4 presents results of the hierarchical multiple regression to predict hoarding severity on the CSI. Step 1 showed child gender significantly predicted hoarding severity; this association remained significant in Step 2, whereas neither child ASD-related social difficulties nor restricted and repetitive behaviors were significant predictors. When child ADHD symptoms were entered into the model (Step 3), both social difficulties and ADHD symptoms significantly predicted hoarding severity and child gender remained a significant predictor. Adding ADHD symptoms significantly increased the proportion of explained variance (from 6 to 18%). Finally, Step 4 showed that anxiety severity significantly predicted hoarding severity controlling for the other factors and child gender, social difficulties, and ADHD symptoms remained significant predictors. The final model explained 20% of the variance in hoarding behaviors.

Correlations Between Hoarding Behaviors and Overall Comorbid Diagnoses

Exploratory analyses assessing links with overall comorbid diagnoses indicated significant weak positive correlations between the presence of a separation anxiety diagnosis and overall hoarding behaviors (r = .22, p = .002), as well as with the Acquisition (r = .26, p < .001), Clutter (r = .23, p = .001), Discarding (r = .21, p = .003), and Distress and Impairment (r = .24, p = .002) subscales. Similarly, positive weak associations were found between the presence of a comorbid ODD and overall hoarding behaviors (r = .26, p < .001), as well as Acquisition (r = .26, p < .001), and Distress and Impairment (r = .22, p = .002) subscales; a similar trend was found for Clutter (r = .23, p = .012) and Discarding (r = .15, p = .036) subscales. Finally, the presence of a diagnosis of fear of change or negative reactions to change was also associated with increased overall hoarding behaviors (r = .19, p = .007), as well as Acquisition (r = .18, p = .009) Distress and Impairment (r = .22, p = .001) and, at a trend level, Clutter (r = .16, p = .024), but not with the Discarding subscale (r = .11, p = .107).

Associations with Primary Diagnosis

A one-way ANOVA indicated no significant differences between the different primary comorbid diagnoses for overall hoarding behaviors (F (9, 194) = .98, p = .459), nor for Acquisition (F (9, 194) = 1.15, p = .333), Clutter (F (9, 194) = 1.27, p = .258), Discarding (F (9, 194) = .80, p = .613), and Distress and Impairment (F (9, 194) = 1.33, p = .224) subscales.

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the presentation and correlates of hoarding behaviors in a sample of 204 children with ASD and comorbid anxiety or OCD symptoms. Hoarding behaviors were highly prevalent, with 33.9% of children presenting with at least moderate overall hoarding levels. Specifically, over 40% of youths presented at least moderate levels of excessive acquisition of items and difficulties in discarding items and over 30% experienced significant clutter. Additionally, more than 40% experienced distress and impairment associated with hoarding such as being upset when someone touched or removed items or when not being able to acquire an item. About 15–30% of children experienced severe to extreme levels of hoarding behaviors; the highest levels were reported for having the room cluttered with possessions, with 75% of parents reporting at least moderate levels and 43.6% reporting that their child’s room was much to completely cluttered by possessions. These rates are particularly high relative to those reported in neurotypical children and adolescents (8.9%), as well as in children with anxiety disorders, OCD, and ASD (Burton et al. 2016; Hamblin et al. 2015; Scahill et al. 2014; Storch et al. 2011). The rates found in the present study are also slightly elevated relative to those reported in the only study investigating hoarding behaviors in children with ASD and comorbid anxiety/OCD symptoms, where 25% of children and adolescents presented moderate to extreme levels of hoarding (Storch et al. 2016). Differences in sample sizes between our sample (n = 204) and the sample in Storch and colleagues’ study (n = 40) may partly explain these differences as, a larger sample may allow observing a wider range of hoarding severity and may increase the probability of including severe cases of hoarding. In addition, the inclusion of a greater proportion of children with comorbid ADHD (82% in our sample vs. 62.5% in the previous) and a larger number of female participants may also explain the slightly higher prevalence found in the present study, given the higher prevalence rates reported in females and in individuals with ADHD (Burton et al. 2016; Fullana et al. 2013; Ivanov et al. 2013; Testa et al. 2011; Wheaton et al. 2008). Our results suggest hoarding behaviors may be a more prevalent feature than previously reported in children with ASD and comorbid anxiety/OCD, highlighting the need for better understanding and intervention.

As expected and consistent with studies in non-ASD populations (Burton et al. 2016; Ivanov et al. 2013; Testa et al. 2011; Wheaton et al. 2008), child gender significantly predicted hoarding behaviors, with girls presenting higher severity relative to boys in all hoarding domains. This association remained significant after adding other factors into the regression model. Our findings suggest for the first time that girls with ASD, who represent approximately 20–25% of the pediatric ASD population (Loomes et al. 2017), are, like girls without ASD, at higher risk of presenting problematic hoarding behaviors.

ADHD symptoms, which include attention and executive functioning difficulties, were also identified as significant predictors of hoarding severity, with higher ADHD symptom severity being associated with higher hoarding severity. These findings are in line with those from a recent study in a similar population (Storch et al. 2016) and with previous studies reporting associations between ADHD and hoarding behaviors in non-ASD pediatric populations (Fullana et al. 2013; Hacker et al. 2016). Different hypotheses have been suggested to explain the association between ADHD and hoarding. For instance, elevated impulsiveness and poor self-control may lead to increased acquisition of objects in older children (Zaboski and Storch 2017), and to increased behavioral outbursts to acquire items in younger children. Indeed, having a comorbid diagnosis of ODD, which is characterized by elevated anger, temper tantrums, and argumentative behavior (American Psychiatric Association (APA) 2013), was also [weakly] associated with increased hoarding severity. Additionally, attention difficulties may be associated with impaired decision making such as difficulties in deciding whether the item is needed or not (Frost and Hartl 1996; Storch et al. 2016). Finally, organization and planning difficulties may prevent children from effectively discarding unneeded items (Storch et al. 2011); this may in turn increase room clutter. Unfortunately, the scale employed in the present study does not allow examining associations between specific ADHD dimensions such as inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsiveness and hoarding behaviors. This should be explored in future studies.

Once ADHD symptom severity was added to the regression model, child ASD-related social difficulties also positively predicted hoarding severity, controlling for child gender. ASD-related social difficulties, including a lack of reciprocity and theory of mind deficits, may lead to poor social insight and social isolation. This may prevent children with ASD from understanding how problematic their hoarding behaviors can be and may impair motivation to discard unneeded items. A previous study did not find associations between social deficits and hoarding severity in youth with ASD with comorbid anxiety/OCD (Storch et al. 2016). However, in that study, the authors employed a more general measure of social functioning that included questions on autistic fixations and preoccupations, a concept that is closer to restricted and repetitive behaviors/interests. Our results suggest that restricted and repetitive behaviors are not associated with hoarding severity.It appears rather that among the typical features of ASD, it is mostly social difficulties that may predict hoarding severity. Our results also suggest that social difficulties alone cannot explain hoarding severity, as the predictor was only significant once ADHD severity was added to the model. Hence, it may be that hoarding behaviors in some children with ASD and anxiety/OCD are more reflective of a lack of social proficiency combined with poor attention and executive function capacities, than manifestations of repetitive and stereotyped behaviors and interests. On the other hand, it is also possible that hoarding behaviors may increase social isolation in youths with ASD. However, given the correlational nature of our study, it is impossible to infer directionality and causality in these associations.

Another important finding is that child anxiety/OCD severity positively predicted hoarding severity over and above child gender, ASD-related social difficulties and restricted and repetitive behaviors, and ADHD symptom severity. Previous research has demonstrated positive associations between anxiety and hoarding severity in individuals with OCD/hoarding disorder without ASD and in mentally healthy individuals (LaSalle-Ricci et al. 2006; Pertusa et al. 2010; Xu et al. 2015). Common features of anxious children including emotion regulation difficulties, uncertainty and worries about potentially needing objects later, and excessive attachment to objects (Nordsletten and Mataix-Cols 2012; Phung et al. 2015; Raines et al. 2015; Shaw et al. 2015), may lead them to adopt hoarding behaviors as a way of securing themselves and coping with distress. These safety behaviors may include an excessive acquisition of objects, as a distraction from negative affect, as well as difficulties in discarding items leading to significant clutter, as a way of preventing potential distress due to loss (Kim 2005; Sloan and Telch 2002; Wells et al. 1995). Safety behaviors have been suggested to be maintained by negative reinforcement processes (Frost and Hartl 1996; Storch et al. 2016), such that the momentary relief experienced by the child when retaining objects increases probabilities of maintaining the behavior over time. Interestingly, the presence of comorbid diagnoses of separation anxiety and fear of/resistance to change was specifically, although weakly, associated with greater hoarding severity. Children experiencing separation anxiety may further retain possessions to secure and comfort themselves when separation is anticipated and may feel distressed when separated from comfort objects. Children resistant to change may feel increasingly distressed by the changes associated with discarding things, leading them to clutter and acquire even more items. Our results are also in line with those from Storch and colleagues (Storch et al. 2016) who found hoarding severity to be positively related to child internalizing symptoms (including anxiety) in youth with ASD and comorbid anxiety/OCD. Of note, the latter study also found significant reductions in hoarding severity after youths underwent 16 weeks of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety/OCD (Storch et al. 2016). Taken together, the current and previous results underscore the importance of treating anxiety and OCD symptoms in youth with ASD, as benefits may extend to other problematic features such as hoarding behaviors.

Finally, contrary to our expectations and to previous results (Storch et al. 2016), not only acquisition but all subdomains of hoarding were significantly related to child anxiety. Again, differences in sample characteristics may explain the discrepancies between previous findings and ours.

The present study has limitations. First, we did not collect information on socioeconomic status, which limits our capacity to assess the generalizability of findings. Second, all children presented with anxiety/OCD symptoms and most had a comorbid anxiety or OCD diagnosis, which limits comparisons with non-anxiety ASD. Third, hoarding and ADHD levels were measured based on parent reports only; this may have led to an underestimation of the symptoms in contexts other than at home (e.g. at school). In addition, ADHD symptoms were only measured with seven items from the CBCL. Although these items have been shown to possess good validity for the assessment of ADHD symptoms (Ebesutani et al. 2010), they do not allow separating inattention from hyperactivity symptoms or assessing other specific ADHD dimensions such as impulsiveness. Another limitation is that we used a cross-sectional design, which limits our capacity to assess directionality in the associations between study variables or predictability. Finally, it is important to keep in mind that the strength of correlations between the different study variables was weak, particularly for associations between hoarding and the different psychiatric comorbidities. In the same line, the final regression model only predicted 20% of the variance in hoarding severity. This suggest other factors may me better predictors of hoarding severity in children with ASD. Future studies should collect information on socioeconomic status, include children without anxiety/OCD as well as teacher reports of ADHD symptoms, use more thorough measures of ADHD symptoms, prioritize longitudinal designs, and explore potential associations with other clinical and demographic factors.

Despite these limitations, this study is the first to provide information on the presentation and predictors of hoarding behaviors in a large sample of well-characterized children with ASD and comorbid anxiety or OCD symptoms geographically dispersed throughout the US. We found a high prevalence of hoarding behaviors among the sample, with prevalence rates higher than those previously reported in a similar population and substantially elevated relative to those found in non-ASD populations. These findings suggest hoarding behaviors may be a common feature in youth with comorbid ASD and anxiety/OCD, with one-third of them presenting at least moderate levels. Results also suggested that girls, as well as children presenting with elevated ASD-related social difficulties, ADHD symptoms, and anxiety/OCD symptom severity, are at higher risk of displaying problematic hoarding behaviors. In addition, having a comorbid diagnosis of separation anxiety, ODD, or fear of/resistance to change was also associated with greater hoarding behaviors. Special attention should be given to these children, given the negative outcomes potentially associated with hoarding. The current findings, together with previous ones (Storch et al. 2016) also suggest that treating anxiety and OCD symptoms in children with ASD may reduce other problematic behaviors such as hoarding, highlighting the need for providing adequate treatment.

References

Achenbach, T. M. (2001). Manual for ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont.

American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association Task Force.

Antshel, K. M., Zhang-James, Y., & Faraone, S. V. (2013). The comorbidity of ADHD and autism spectrum disorder. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 13, 1117–1128.

Baio, J. (2012). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 Sites, United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries. Vol. 61, Number 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Bejerot, S. (2007). An autistic dimension: A proposed subtype of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Autism, 11, 101–110.

Burton, C. L., et al. (2016). Clinical correlates of hoarding with and without comorbid obsessive-compulsive symptoms in a community pediatric sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55, 114–121.

Cadman, T., et al. (2015). Obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: What does self-report with the OCI-R tell us? Autism Research: Official Journal of the International Society for Autism Research 8, 477–485. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1461.

CDC (2014). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years: Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Surveillance Summaries, 63, 1–21.

Ebesutani, C., et al. (2010). Concurrent Validity of the child behavior checklist DSM-oriented scales: Correspondence with DSM diagnoses and comparison to syndrome scales. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32, 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-009-9174-9.

Frost, R. O., & Hartl, T. L. (1996). A cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 341–350.

Frost, R. O., Steketee, G., & Tolin, D. F. (2011). Comorbidity in hoarding disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 28, 876–884.

Frost, R. O., Tolin, D. F., Steketee, G., Fitch, K. E., & Selbo-Bruns, A. (2009). Excessive acquisition in hoarding. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 632–639.

Fullana, M. A., et al. (2013). Is ADHD in childhood associated with lifetime hoarding symptoms? An epidemiological study. Depress Anxiety, 30, 741–748. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22123.

Geurts, H. M., Verte, S., Oosterlaan, J., Roeyers, H., & Sergeant, J. A. (2004). How specific are executive functioning deficits in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 836–854.

Gilotty, L., Kenworthy, L., Sirian, L., Black, D. O., & Wagner, A. E. (2002). Adaptive skills and executive function in autism spectrum disorders. Child Neuropsychology, 8, 241–248.

Grisham, J. R., Steketee, G., & Frost, R. O. (2008). Interpersonal problems and emotional intelligence in compulsive hoarding. Depression and Anxiety, 25, E63–E71.

Hacker, L. E., et al. (2016). Hoarding in children with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 20, 617–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054712455845.

Hamblin, R. J., Lewin, A. B., Salloum, A., Crawford, E. A., McBride, N. M., & Storch, E. A. (2015). Clinical characteristics and predictors of hoarding in children with anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 36, 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.07.006.

Hill, E. L. (2004). Executive dysfunction in autism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8, 26–32.

Ivanov, V. Z., et al. (2013). Prevalence, comorbidity and heritability of hoarding symptoms in adolescence: A population based twin study in 15-year olds. PLoS ONE, 8, e69140. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069140.

Kendall, P. C., Hudson, J. L., Gosch, E., Flannery-Schroeder, E., & Suveg, C. (2008). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 282.

Kerns, C. M., et al. (2016). The treatment of anxiety in autism spectrum disorder (TAASD) study: Rationale, design and methods. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 1889–1902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0372-2.

Kerns, C. M., Renno, P., Kendall, P. C., Wood, J. J., & Storch, E. A. (2017). Anxiety disorders interview schedule–autism Addendum: Reliability and validity in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46, 88–100.

Kim, E.-J. (2005). The effect of the decreased safety behaviors on anxiety and negative thoughts in social phobics. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 19, 69–86.

Kogan, M. D., et al. (2009). Prevalence of parent-reported diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder among children in the US, 2007. Pediatrics, 124, 1395–1403.

LaSalle-Ricci, V. H., Arnkoff, D. B., Glass, C. R., Crawley, S. A., Ronquillo, J. G., & Murphy, D. L. (2006). The hoarding dimension of OCD: Psychological comorbidity and the five-factor personality model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1503–1512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.11.009.

Leyfer, O. T., et al. (2006). Comorbid psychiatric disorders in children with autism: Interview development and rates of disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 36, 849–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0123-0.

Loomes, R., Hull, L., & Mandy, W. P. L. (2017). What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56, 466–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., Risi, S., Gothman, K., & Bishop, S. L. (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule, second edition (ADOS-2). Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Mattila, M. L., et al. (2010). Comorbid psychiatric disorders associated with Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism: A community- and clinic-based study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1080–1093. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-0958-2.

McDougle, C. J., et al. (1995). A case-controlled study of repetitive thoughts and behavior in adults with autistic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 772–777. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.152.5.772.

Nordsletten, A. E., et al. (2013). Epidemiology of hoarding disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 203, 445–452.

Nordsletten, A. E., & Mataix-Cols, D. (2012). Hoarding versus collecting: Where does pathology diverge from play? Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.12.003.

Olley, A., Malhi, G., & Sachdev, P. (2007). Memory and executive functioning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A selective review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 104, 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.02.023.

Pertusa, A., et al. (2010). Refining the diagnostic boundaries of compulsive hoarding: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.007.

Pertusa, A., et al. (2012). Do patients with hoarding disorder have autistic traits? Depression and Anxiety, 29, 210–218.

Phung, P. J., Moulding, R., Taylor, J. K., & Nedeljkovic, M. (2015). Emotional regulation, attachment to possessions and hoarding symptoms. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56, 573–581. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12239.

Raines, A. M., Allan, N. P., Oglesby, M. E., Short, N. A., & Schmidt, N. B. (2015). Specific and general facets of hoarding: A bifactor model. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 34, 100–106.

Russell, A. J., Mataix-Cols, D., Anson, M., & Murphy, D. G. (2005). Obsessions and compulsions in Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 525–528.

Ruta, L., Mugno, D., D’Arrigo, V. G., Vitiello, B., & Mazzone, L. (2010). Obsessive–compulsive traits in children and adolescents with Asperger syndrome. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 19, 17.

Scahill, L., et al. (2014). Children’s Yale–Brown obsessive compulsive scale in autism spectrum disorder: Component structure and correlates of symptom checklist. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53, 97–107. e1.

Schopler, E., Van Bourgondien, M. E., Wellman, G. J., & Love, S. R. (2009). Childhood autism rating scale (2nd edn.). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Shaw, A., Timpano, K., Steketee, G., Tolin, D., & Frost, R. (2015). Hoarding and emotional reactivity: The link between negative emotional reactions and hoarding symptomatology. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 63, 84–90.

Silverman, W. K., & Albano, A. M. (1996). The anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV- child and parent versions. San Antonio, TX: Oxford University Press.

Sloan, T., & Telch, M. J. (2002). The effects of safety-seeking behavior and guided threat reappraisal on fear reduction during exposure: An experimental investigation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40, 235–251.

Storch, E. A., et al. (2011). Development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of the Children’s Saving Inventory. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 42, 166–182.

Storch, E. A., et al. (2012). Multiple informant agreement on the anxiety disorders interview schedule in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 22, 292–299.

Storch, E. A., et al. (2016). Hoarding in youth with autism spectrum disorders and anxiety: Incidence, clinical correlates, and behavioral treatment response. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 1602–1612.

Testa, R., Pantelis, C., & Fontenelle, L. F. (2011). Hoarding behaviors in children with learning disabilities. Journal of Child Neurology, 26, 574–579. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073810387139.

The Research Units On Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study (RUPP), G. (2002). The pediatric anxiety rating scale (PARS): Development and psychometric properties. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 1061–1069 https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200209000-00006.

Timpano, K. R., et al. (2011). The epidemiology of the proposed DSM-5 hoarding disorder: Exploration of the acquisition specifier, associated features, and distress. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72, 780–786. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.10m06380. (quiz 878–879).

Wechsler, D. (1999). Manual for the Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence. San Antonio, TX, The Psychological Corporation.

Wells, A., Clark, D. M., Salkovskis, P., Ludgate, J., Hackmann, A., & Gelder, M. (1995). Social phobia: The role of in-situation safety behaviors in maintaining anxiety and negative beliefs. Behavior Therapy, 26, 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80088-7.

Wheaton, M., Timpano, K. R., LaSalle-Ricci, V. H., & Murphy, D. L. (2008). Characterizing the hoarding phenotype in individuals with OCD: Associations with comorbidity, severity and gender. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.01.015.

White, S. W., Oswald, D., Ollendick, T., & Scahill, L. (2009). Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 216–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.003.

Woody, S. R., Kellman-McFarlane, K., & Welsted, A. (2014). Review of cognitive performance in hoarding disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 34, 324–336.

Xu, W., Fu, Z., Wang, J., & Zhang, Y. (2015). Relationship between autistic traits and hoarding in a large non-clinical Chinese sample: Mediating effect of anxiety and depression. Psychological Reports, 116, 23–32. https://doi.org/10.2466/15.PR0.116k17w0.

Zaboski, B. A., & Storch, E. A. (2017). Hoarding in youth with autism spectrum disorders. In F. R. Volkmar (Ed.), Encyclopedia of autism spectrum disorders. (pp 1–3). New York, NY: Springer.

Acknowledgments

Data included in this paper were supported in part by grants to the second, third, and last authors (R01HD080098-01A1, R01HD080097-01A1, and R01HD080096-01A1) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect those of NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VLB and EAS generated the idea. VLB was the primary writer of the manuscript, and VB and EAS approved all changes. BJS and VLB supported the data analysis and writing of the manuscript. JJW, PCK, NMB, SLC, ABL, CK and EAS provided input around the interpretation of results and supported the writing of this manuscript. All authors supported study activities and interpretation of the results. All authors were involved in developing, editing, reviewing, and providing feedback for this manuscript and have given approval of the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. La Buissonniere-Ariza has received a postdoctoral research scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Storch has received royalties from Elsevier Publications, Springer Publications, American Psychological Association, Wiley, Inc, and Lawrence Erlbaum. He has received research funding from National Institute of Health and All Children’s Hospital Research Foundation. Dr. Lewin has received research grants from the Tourette Syndrome Association and the All Children’s Hospital. He has received financial support for attenting symposia from the American Psychological Association, American Board of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, Society for Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, and Tourette Syndrome Association. He is a consultant for Bracket and LLC, a member of the board of directors of the American Board of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, Society for Clinical Child and Adolescent, Florida’s Diabetes Camp, a member of the scientific and clinical advisory board of the International OCD Foundation, and co-director of the Southeastern Tourette Syndrome Association Center of Excellence. He has received royalties from Springer Publishing and Kingsley Publishing. Dr Kerns has received research funding support from NICHD (HD K23087472) and the Autism Science Foundation. She also receives royalties from Elsevier Publishing for an edited book, and is sole owner of Connor Kerns, PhD, LLC which provides consulting on assessment and treatment of anxiety in ASD.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

La Buissonnière-Ariza, V., Wood, J.J., Kendall, P.C. et al. Presentation and Correlates of Hoarding Behaviors in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Comorbid Anxiety or Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms. J Autism Dev Disord 48, 4167–4178 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3645-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3645-3