Abstract

For individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), long-term outcomes have been troubling, and intact IQ has not been shown to be protective. Nevertheless, relatively little research into adaptive functioning among adults with ASD has been completed to date. Therefore, both adaptive functioning and comorbid psychopathology were assessed among 52 adults with ASD without intellectual disability (ID). Adaptive functioning was found to substantially lag behind IQ, and socialization was a particular weakness. Comorbid psychopathology was significantly correlated with the size of IQ-adaptive functioning discrepancy. These findings emphasize key intervention targets of both adaptive skill and psychopathology for transition-age youth and young adults with ASD, as well as the need for ongoing monitoring of anxiety and depression symptoms during this developmental window.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adaptive functioning refers to a set of behaviors related to personal independence, encompassing home living skills, community navigation, self-care, socialization, and communication. In general, typical performance of the real-life skills involved in adaptive functioning is consistent with one’s cognitive functioning, such that individuals with lower IQ show lower adaptive behaviors and greater dependence on others. A different trajectory has been observed in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), who show notable gaps between adaptive functioning and cognitive level, particularly amongst individuals with average or higher IQ levels (Kanne et al. 2011; Klin et al. 2007), as well as age-related declines in adaptive behavior through adolescence (Pugliese et al. 2015). Little is known about adaptive behavior specifically in adults with ASD without intellectual disability (ID), but outcomes for adults with ASD are troubling, with lower postsecondary education and employment compared to adults with other developmental disabilities, such as ID, specific learning disabilities (in reading, written expression, or mathematics), and speech/language impairment (Shattuck et al. 2012). Outcomes for adults with ASD and average-range IQ are even more deeply concerning, showing lower rates of independent living than their neurotypical peers (Howlin and Moss 2012) and high rates of support required for participation in post-secondary education or employment (Howlin et al. 2004). Additionally, nearly 25% of adults with ASD and average-range IQ report having no daytime activities of any kind, an even higher rate than their ASD peers with accompanying ID (Taylor and Seltzer 2011). In other words, despite average-range cognitive abilities, some adults with ASD are significantly struggling to engage in daily activities and routines relative to their neurotypical peers with comparable IQ levels. In fact, considerable variability reported in outcomes for adults with ASD without ID suggests that higher IQ does not appear to be protective in ASD for improving outcomes (Howlin et al. 2004), and even bright individuals are struggling to launch appropriately into adulthood.

Although the gap between IQ and adaptive functioning in children and adolescents with ASD is consistently observed in the literature, little is understood about the predictors of adaptive functioning. In a large study exploring predictors of daily living skills for adolescents with ASD and average IQ, ASD symptomatology, IQ, maternal education, age, and sex accounted for just 10% of the variance (Duncan and Bishop 2015). In a sample of non-ID children with ASD using the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System-II (ABAS-II), IQ did not predict adaptive functioning, but severity of ASD symptomatology significantly negatively predicted overall adaptive functioning (Lopata et al. 2012), suggesting that, amongst individuals without ID, unique factors are contributing to their adaptive profile.

In order to understand the contributing factors and address this discrepancy in ASD (with and without ID) and neurotypical outcomes in regard to their adaptive functioning, it is vital to better understand the clinical presentation of ASD adults without ID and contributing factors to their profile. A clearer picture of their adaptive profile, as well as the psychiatric comorbidities that might impact these profiles, may help shape clinical intervention, thereby improving outcomes. To date, there have been few studies focusing on adaptive functioning in ASD adults without ID (see Table 1 for review), and no studies yet exist that explore psychiatric comorbidities and their associations with adaptive functioning in adults with ASD without ID. Mirroring a pattern observed in children (Kenworthy et al. 2010), socialization (relative to other adaptive skills) appears to be a particular weakness in the adult adaptive profile (Matthews et al. 2015). In one longitudinal study, individuals with ASD and average-range IQ who were followed into adulthood—a subset of the total population studied—showed deficits in daily living skills, with skills lagging 7–16 years behind chronological age expectations (Bal et al. 2015). Although most of the existing studies on adaptive functioning in adults with ASD have gathered data on IQ, and some report mean IQ in the average range (Farley et al. 2009; Matthews et al. 2015), none has included only individuals without ID, a population that presents with unique concerns for outcomes.

Within ASD, rates of co-occurring mental health conditions are high, with estimates as high as 70% for the presence of at least one comorbid disorder in children with ASD, with social anxiety and ADHD reported as most common, at 29.2 and 28.2% respectively (Simonoff et al. 2008). A study of adults with ASD revealed high levels of co-occurring anxiety at a prevalence of 50%, and 70% reported at least one episode of major depression (Lugnegard et al. 2011). The risk of co-occurring psychiatric conditions is also significantly higher for ASD adults than in the general population, ranging from 2.9 times greater likelihood for developing depression to 22 times greater likelihood for developing co-occurring schizophrenia (Croen et al. 2015). In addition, high rates of psychiatric comorbidities have been linked with lower quality of life in adults with ASD (Kamio et al. 2013).

To date, however, there have been no studies examining associations between co-occurring psychopathology and adaptive functioning using standardized measures in adults with ASD without ID. Findings of adolescents with ASD without ID have suggested increased vulnerability to depressive symptoms in particular, due in part to social comparison processes. Because of the higher cognitive skill in those without ID, self-awareness is more intact, leading to a higher level of social comparison and subsequent depression (Hedley and Young 2006). For adults without ID with apparent discrepancies between their daily living skills and socialization skills, this gap may be more acutely perceived and therefore lead to higher levels of depression or anxiety. Alternatively, depression or anxiety symptoms may interfere with an individual’s initiative, thus impacting engagement in social and daily living tasks. Additionally, because of the executive function demand of independently executing tasks related to adaptive behavior (Pugliese et al. 2015), we might also expect increased ADHD symptoms to be related to poorer adaptive skills in adulthood. In a sample that included a majority of adults with ID (70% of the sample), no significant correlation between adaptive functioning and psychopathology was observed when maternal warmth was co-varied (Woodman et al. 2016). However, a close look at levels of mental health symptoms in relation to adaptive functioning for individuals without ID has yet to be done. This is an important early step to effectively address poor outcomes for adults with ASD, as adults with ASD without ID pose unique challenges related to increased self-awareness, as well as increased expectations of independence due to higher cognitive skill. When cognitive skill does not translate to measurable successes in adult adaptive functioning, this may result in increased psychopathology. Alternatively, for individuals with higher rates of depression and anxiety, this may in turn impact their ability to engage fully or in an age-appropriate way in the daily living or socialization tasks expected of adults.

Adaptive functioning in the literature has most often been measured using the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS). While the VABS is a rich measure of adaptive functioning, with an extensive body of research supporting its use for younger populations with ASD (e.g., Carter et al. 1998; Stone et al. 1999; Liss et al. 2001; Fenton et al. 2003; Klin et al. 2007), less work has been done using alternative assessments of adaptive functioning to measure correlates of adaptive functioning in adults with ASD. In a population of children with ASD and average IQ, the ABAS-II showed good utility in characterizing impairments in adaptive functioning (Kenworthy et al. 2010). The ABAS-II, while correlated highly with VABS scores (Lopata et al. 2013), has not been adequately studied as a comparable measure of adaptive functioning in adults with ASD. This alternative measure of adaptive functioning assesses domains that differ to a degree from the VABS. Additionally, because the ABAS-II utilizes distinct measures for different age groups and has normative data for age ranges that reach into early adulthood (school age form, ages 5–21) and adulthood (adult form, ages 16–89), there are additional items providing information for adult-age adaptive functioning (e.g., budgeting money to cover expenses, checking bank account regularly, obtaining rental or car insurance independently, following maintenance schedule for a car). This is particularly relevant for research focusing primarily on adults without ID, for whom comparisons to age-appropriate adaptive functioning may be particularly useful.

The current paper seeks to examine the unique profile of adaptive functioning in adults with ASD. Specifically, because no study thus far has looked exclusively at adults without ID, the current study includes only adults with ASD without ID. Based on prior reports of adaptive functioning profiles observed in children with average IQ, we hypothesize that socialization will be a particular weakness in adults with ASD, and that adaptive functioning will fall well below cognitive functioning. To further understand the impact of co-occurring psychiatric conditions on the independent living skills of adults with ASD without ID, we examine the relationship between comorbid psychopathology in adults with ASD and level of adaptive functioning. We hypothesize that levels of co-occurring psychopathology (i.e., anxiety, depression, and ADHD symptomatology) will be negatively correlated with adaptive functioning, and that a greater discrepancy in cognitive and adaptive functioning will be associated with greater symptomatology.

Methods

Fifty-two adults (six female) with ASD ranging in age from 17.6 to 30.8 years (M = 21.1, SD = 2.9) participated in the study. Full-Scale IQ scores for all participants were above 70 (FSIQ M = 110.1, SD = 14.3, range = 75–143), as measured by the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI; Wechsler 1999) and Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence-Second Edition (WASI-II; Wechsler 2011). All subjects met DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASD, as assessed by an experienced clinician. Diagnoses were confirmed by a trained, research-reliable clinician through the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI or ADI-R; LeCouteur et al. 1989; Lord et al. 1994; 49 participants) and/or the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al. 2000, 48 participants)/the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Second Edition (ADOS-2; Lord et al. 2012, three participants), Modules 3 (2 participants) and 4 (49 participants). Participants met cut-off scores for the category of “Broad ASD” as designated by criteria established by the NICHD/NIDCD Collaborative Programs for Excellence in Autism (see Lainhart et al. 2006). This category was defined as meeting ADI-R cut-off for “autism” in the social domain and at least one other domain, or meeting the ADOS cut-off for the combined social and communication score. Exclusion criteria included an IQ < 70, comorbid genetic or neurological conditions (e.g., Fragile X or other known genetic disorder, brain trauma/injury) that affect brain and behavioral functioning. See Table 2.

Procedures

This project was part of a larger study examining brain and behavioral functioning in ASD. The current study was conducted in compliance with standards established by the institution’s IRB, including procedures for informed consent.

Measures

Adaptive Functioning

The Adaptive Behavior Assessment System-Second Edition (ABAS-II; Harrison and Oakland 2003) is a measure of adaptive behavior and independent living skills across a variety of domains with national standardization samples representative of the English speaking US population. The ABAS-II manual (Harrison and Oakland 2003) provides data documenting strong test–retest reliability (mostly 0.90 or higher for the measure), as well as convergent validity with the VABS. For the current study, all participants were assessed using the informant report adult form of the ABAS-II, completed by either a parent or guardian (only one subject had a non-parent complete the form, which was completed by a case manager), which was standardized on an age-stratified sample. Participants presented for the research appointments with a parent or guardian who was familiar with the participants’ functioning and able to fill out the ABAS-II. Results provide information in the areas of Conceptual Skills (Communication, Functional Academics, Self-Direction domains), Social Skills (Leisure and Social domains), and Practical Skills (Community Use, Home Living, Health and Safety, and Self-Care domains) as well as an overall score [General Adaptive Composite (GAC)]. Scores are presented as norm-referenced scaled scores (skill area domain scores: M = 10; SD = 3) or standard scores (composite scores: M = 100; SD = 15) such that higher scores represent better adaptive functioning (see Table 3).

Co-occurring Psychopathology

Co-occurring psychopathology was measured via the Adult Behavior Checklist (ABCL; Achenbach and Rescorla 2003). The ABCL is a 118-item scale composed of statements of behavior rated as ‘not true’, ‘somewhat or sometimes true’ and ‘very true’. The manual for this instrument (Achenbach and Rescorla 2003) documents good construct validity, test–retest reliability (most r values in the 0.80s and 0.90s), and internal consistency. The current study utilized the informant-rating version of the ABCL (appropriate for ages 18–59), which was filled out by parents/guardians. DSM-oriented subscales from the ABCL measuring anxiety problems, depression problems, and attention problems were used as correlates of interest. Ratings are expressed as T-scores (M = 50; SD = 10) derived from comparisons with normative-age expectations. Higher scores are indicative of more problem behaviors, and T-scores of 65 or higher are categorized as clinically significant (see Table 2).

Social Functioning

The Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS; Constantino and Gruber 2005) and Social Responsiveness Scale-Second Edition (SRS-2; Constantino and Gruber 2012) are 65-item standardized questionnaires regarding behaviors associated with ASD. The items on both measures are identical, with the second version reflecting updated norms. Both versions are standardized with sex-normed data, and the original version of the SRS showed good convergent validity with the ADI for identifying autism-related symptoms and behaviors (Constantino et al. 2003). The second version of the SRS was released after data collection for the current study was underway; for consistency, because the items are identical between the two versions, all responses from the first version of the SRS were re-scored using the updated norms from the age appropriate version of the SRS-2, so that the final scores used were effectively the SRS-2. Informant ratings were used for all participants, and either the school-age version (for individuals under 19; 7 participants) or the adult-version (45 participants) was used. Ratings are expressed as T-scores (M = 50; SD = 10) derived from comparisons with normative-sex expectations (see Table 2). Higher scores are indicative of greater social difficulty and autistic traits and behaviors, and T-scores of 65 or higher are categorized as clinically significant. For the current study, T-scores for the dyad of DSM-5 compatible aggregate domains of Social Communication and Interaction (SCI) and Restricted Interests and Repetitive Behavior (RRB) were used as correlates of interest.

Data Analytic Plan

All statistical analyses were completed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 23.

Comparison to Normative Data

One-sample t-tests were conducted to assess for discrepancies in adaptive skill compared to the age-stratified standardization sample of the ABAS-II. Statistical reference values of 100 (for composite scores) and 10 (for scaled scores) were used.

Strengths/Weaknesses Profile Analysis

ABAS-II strengths and weaknesses were determined for each participant’s skill area by comparing the difference between their individual skill area scores and the participant’s overall mean across all nine skill areas. If the absolute value of a negative difference score was greater than the critical value for a skill area, as determined by the ABAS-II manual (ABAS-II manual, Table B.8; Harrison and Oakland 2003), the skill area was then determined to be a significant weakness for the participant (p < .05). If a positive difference score was greater than the critical value for a skill area, then the skill area was said to be a significant strength for the participant (p < .05).

Correlation of Age and VIQ with ABAS-II

To determine whether IQ and age should be utilized as nuisance covariates when examining the relationship between adaptive functioning and both co-morbid psychopathology and social functioning, correlations were examined between ABAS-II composite scores and verbal, performance, and full-scale IQ scores from the WASI and age. If IQ and/or age were found to be significantly correlated with any ABAS-II composite score, a conservative approach was used designating IQ and/or age as covariates for each of the subsequent ABAS-II and psychopathology/social functioning correlations.

Correlations with Co-Morbid Psychopathology and Social Functioning

Partial correlations were run between each of the four composite scores from the ABAS-II (GAC, Conceptual, Practical, and Social) and both selected domains from the ABCL (DSM scales of Depression, Anxiety, and ADHD) and autistic traits as measured by the SRS-2 (SCI and RRB).

IQ—Adaptive Skill Discrepancy Correlations

A paired-samples t-test was run to explore differences in overall adaptive skills (ABAS-II GAC) and intellectual functioning (Full Scale IQ). Because the discrepancy in IQ and adaptive functioning in individuals with ASD is observed across the lifespan (e.g., Klin et al. 2007; Pugliese et al. 2015), we also explored co-morbid psychopathology and social functioning correlates of the discrepancy between IQ and ABAS-II. IQ—ABAS-II Composite difference scores were calculated by subtracting each of the four ABAS-II Composite scores (GAC, Conceptual, Practical, and Social) from the WASI Full-Scale IQ. Pearson’s correlation was then used to relate each of the four generated IQ—ABAS-II difference scores to psychopathology symptoms and social functioning from the ABCL and SRS-2, respectively.

Results

A detailed examination of the data revealed an outlying ABAS-II score within the Practical (one outlier) domain. However, inspection of skewness and kurtosis values revealed that the data, nevertheless, fell within allowable limits of normally distributed data. Therefore, all values were included in analyses.

Comparison to Normative Data

One-sample t tests yielded significantly lower adaptive skills across all four ABAS-II composite scores as compared to the normative, general population (all ps < 0.001). All nine individual skill areas were also significantly lower than the scores from the ABAS-II standardization sample (all ps < 0.001).

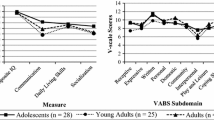

Strengths/Weakness Profile Analysis

Figure 1 shows the skill area score profiles across all ABAS-II domains. For each skill area, the figure shows the percentage of individuals exhibiting a significant strength (positive y axis) or significant weakness (negative y axis) relative to their other skill areas (i.e., the participant’s difference score in that skill area exceeded the critical value reported in the ABAS-II manual for that skill area). Visual inspection clearly reveals social skills as a deficit (e.g., weaknesses in: organizing activities with others, trying a new activity, seeking friendships and showing good judgment in selecting friends, recognizing and stating emotional states), with nearly 20% of participants reporting socialization skills that fell significantly below their average adaptive functioning in other areas, and only 2% reporting a relative strength in socialization. Home living (e.g., completing laundry, taking out trash, paying bills on time) was the area of most common relative strength. Community use (e.g., following directions to nearby areas, considering cost and necessity before buying items at a store, making appointments), functional academics (e.g., basic reading, writing, and math to complete everyday activities), and health and safety (e.g., following safety rules, taking medication safely) were also relative strengths for participants, with few participants reporting a relative weakness in these areas.

Correlation of Age and VIQ with ABAS-II

Age was not significantly correlated with any of the ABAS-II composite scores. Verbal IQ was found to be significantly correlated with the Conceptual composite (r = .30, p < .05), but was not significantly correlated with the remaining ABAS-II composite scores (all p values > 0.05). Taking a conservative approach, VIQ was therefore entered as a covariate in subsequent analyses.

Correlations with Co-Morbid Psychopathology and Social Functioning

SRS-2 (RRB and SCI) and ABCL domains (Depression, Anxiety, and ADHD) were all significantly negatively correlated with all ABAS-II composite scores after controlling for VIQ, with effect sizes ranging from medium to large (ranging from r = − .37 to − 0.72). See Table 4.

IQ—Adaptive Skill Discrepancy Analysis

A paired-samples t-test between ABAS-II GAC and FSIQ scores yielded a highly significant difference [t(48) = −11.965, p < .001), with significantly higher IQ than overall adaptive skill ratings for participants.

Discrepancy values between FSIQ and ABAS-II GAC composite scores were significantly positively correlated (medium effect size) with ABCL Depression, ABCL Anxiety, and SRS-2 SCI (see Table 5), such that greater discrepancies between IQ and adaptive skill ratings were associated with more depression and anxiety symptoms and more impaired social functioning. FSIQ–GAC discrepancy scores were not significantly related to ABCL ADHD symptoms.

Discussion

In this first study (to our knowledge) to examine the adaptive behavior profile for adults with ASD with non-ID cognitive functioning (IQ above 70) using the ABAS-II, we found adaptive skills that were significantly lower than those found among same-age peers from the normative population, as well as a clear and significant discrepancy between participants’ cognitive abilities and adaptive functioning, with relative impairment in adaptive behavior. The ASD adults’ profile of strengths and weaknesses paralleled previous findings of greatest weaknesses in socialization relative to other adaptive skill areas among adolescents with ASD (e.g., Kenworthy et al. 2010), and indicated relative strengths in the areas of home living and functional academics. Additionally, we showed that lower adaptive functioning was related to higher levels of anxiety, depression, ADHD, social difficulties, and repetitive behavior. Finally, greater discrepancy between participants’ cognitive and adaptive functioning, or a larger gap between IQ and ABAS scores, was related to higher levels of depression, anxiety, and social difficulties.

Overall, these findings extend previous reports from research with younger populations with ASD upwards to adults. Namely, consistent with findings from children and adolescents with average IQ (e.g., Pugliese et al. 2015), adaptive behavior profiles in the current study reflect impairment that is incongruent with cognitive abilities. Previous literature has shown that daily living skills improve slightly through post-schooling transition ages (through early 20s) and then subsequently plateau (Smith et al. 2012). Our work has expanded on this to include the full adaptive profile of adults (including examination of social and communication skills), suggesting that home living and functional academic skills are more often a relative strength in the adaptive profile of adults with ASD without ID into their 30s, but that overall there is impairment across all adaptive skill areas. These findings are also consistent with findings of poor adaptive functioning using the VABS with adults, including the finding of relatively greater impairment in socialization compared to other adaptive domains (e.g., Matthews et al. 2015; Farley et al. 2009; Bal et al. 2015). Using an alternative measure of adaptive functioning, our findings reflect the dire reality that average range or greater IQ does not protect those with ASD from everyday struggles navigating societal demands placed upon adults. It is worth noting that, with the use of the informant-report ABAS-II, rather than the clinician interview afforded by the VABS, our findings are vulnerable to potential over-inflation of scores, as without the clinician interview, informants are more likely to report what the individual can perform, rather than what they do perform independently without support. As a result, there may be an even more significant gap between cognitive functioning and adaptive functioning than the current findings indicate. Similarly, the GAC may also slightly overestimate overall adaptive skill due to the domains in which individuals show relative strengths (such as Functional Academics). Despite this potential, however, the adaptive scores achieved by our sample were still well below age-normed expectations.

This is also the first study to examine the co-morbid psychopathology correlates of adaptive functioning in adults with ASD without ID, with adaptive functioning correlating significantly and inversely with the level of anxiety, depression, ADHD symptoms, and social functioning, even after controlling for the effects of age and verbal IQ. Other studies have examined co-morbid psychopathology correlates of adaptive skills, but in samples of primarily or entirely adults with ID (Woodman et al. 2016; Totsika et al. 2010; Forster et al. 2011). Among adults with ASD with non-ID IQ, we have found a strong inverse correlational relationship between adaptive functioning and level of psychopathology and social symptoms. Our data are correlational only, and obviously do not address causality, but the associations are nevertheless pointing to important mental health factors related to adaptive functioning, including that the risks of poor adaptive functioning appear to increase with greater depression, anxiety, ADHD, and social symptoms. Furthermore, although most, but not all correlations, survive multiple comparison correction procedures, we have demonstrated the greatest risk for those with the greatest discrepancy between IQ and adaptive functioning. More specifically, we have shown that anxiety, depression, and social symptoms are highest for those with the largest gaps between IQ and adaptive function. Correlating co-morbidities with the size of the gap between IQ and adaptive functioning allows us to emphasize the lack of protection that high IQ has on mental health and everyday functioning in ASD, and also highlights the need to monitor for concerning levels of psychopathology when IQ outpaces adaptive skill. The lack of research in this area suggests that we have thus far not appreciated how psychopathology might be driving the adaptive profile of adults with ASD without ID, or visa versa. While these individuals with higher IQ are often viewed as “high functioning,” not only do their adaptive functioning profiles suggest this term is an over generalization, but there is also ongoing and significant concern for their mental health in the midst of navigating adult responsibilities. Particularly if these findings are replicated in future investigations, they highlight the interrelated nature of psychopathology and adaptive functioning, and that intervention in psychopathology may improve adaptive functioning. Conversely, if intervention focuses solely on adaptive functioning, little improvement may be seen if psychopathology is present. More work is needed to understand the underlying mechanism that mediates this association in order to effectively address these deficits.

Primary limitations of this study include the exclusion of participants with co-occurring ID. Although we intentionally limited participants to IQ > 70 to characterize the adaptive functioning profile related to poor outcomes for those specifically with intact cognitive functioning, this choice does contribute to limited generalizability of our findings to the full spectrum of ASD. Similarly, our sample included very few females, leading to difficulty generalizing our findings to adult females with ASD. Additionally, our study design did not employ a control group, limiting our ability to compare this pattern of findings to matched (e.g., on IQ and/or sex ratio) neurotypical peers. However, we relied upon a robust age-referenced normative sample from the ABAS-II to determine the degree to which adaptive functioning was atypical in ASD. At the same time, the current study’s design is limited by its reliance on parent/caregiver-report measures, which are more likely to be highly correlated with each other and potentially falsely inflate significant findings. More work is needed on the validity of self-report measures, and it would be particularly helpful to understand the role of self-awareness in adults with ASD without ID and its impact on understanding of their adaptive functioning. Future research should more closely examine the correlation between parent- and self-report and their perception of their adaptive functioning.

Future work that includes a control group, more females, and a comparison group of adults with low-IQ, with and without ASD, will help to reveal the contributing factors that are unique to ASD without ID. As this is the first study addressing this unique profile, the findings need to be replicated, both with the ABAS and with other standardized measures of adaptive behavior. While the current research relied on informant-report for measurement of adaptive skill and psychopathology, which is a common practice in both clinical and research work, future work would benefit from pairing informant-report to both self-report and direct clinical observation for a richer characterization of participants’ adaptive and mental health profiles. Furthermore, while we have demonstrated correlation between adaptive profile and mental health factors, more work needs to be done to determine causality, such as utilizing longitudinal designs. Evidence of causation would help to isolate ideal treatment targets leading to the development of effective interventions, including interventions that could potentially leverage the strong cognitive skills of these individuals.

Taken together, these findings underscore the fact that adults with ASD without ID lack many skills that are required for independent functioning in adulthood. Furthermore, the greater the gap between cognitive skill and everyday adaptive skill, the greater the level of depression and anxiety: necessary future steps include the development of interventions that attend to mental health and simultaneously seek to positively, pro-actively monitor, teach, and develop adaptive skills prior to the adult years.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2003). Manual for the ASEBA adult forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families.

Bal, V. H., Kim, S. H., Cheong, D., & Lord, C. (2015). Daily living skills in individuals with autism spectrum disorder from 2 to 21 years of age. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 19(7), 774–784.

Carter, A. S., Volkmar, F. R., Sparrow, S. S., Wang, J. J., Lord, C., Dawson, G. et al. (1998). The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales: supplementary norms for individuals with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 28(4), 287–302.

Constantino, J. N., Davis, S. A., Todd, R. D., Schindler, M. K., Gross, M. M., Brophy, S. L. et al. (2003). Validation of a brief quantitative measure of autistic traits: comparison of the social responsiveness scale with the autism diagnostic interview-revised. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(4), 427–433.

Constantino, J. N., & Gruber, C. P. (2005). Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Constantino, J. N., & Gruber, C. P. (2012). Social Responsiveness Scale–Second Edition (SRS-2). Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Croen, L. A., Zerbo, O., Qian, Y., Massolo, M. L., Rich, S., Sidney, S., & Kripke, C. (2015). The health status of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 19(7), 814–823.

Duncan, A. W., & Bishop, S. L. (2015). Understanding the gap between cognitive abilities and daily living skills in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders with average intelligence. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 19(1), 64–72.

Farley, M. A., McMahon, W. M., Fombonne, E., Jenson, W. R., Miller, J., Gardner, M. et al. (2009). Twenty-year outcome for individuals with autism and average or near-average cognitive abilities. Autism Research, 2(2), 109–118.

Fenton, G., D’ardia, C., Valente, D., Del Vecchio, I., Fabrizi, A., & Bernabei, P. (2003). Vineland adaptive behavior profiles in children with autism and moderate to severe developmental delay. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 7(3), 269–287.

Forster, S., Gray, K. M., Taffe, J., Einfeld, S. L., & Tonge, B. J. (2011). Behavioural and emotional problems in people with severe and profound intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 55(2), 190–198.

Harrison, P., & Oakland, T. (2003). Adaptive Behavior Assessment System - Second Edition (ABAS-II). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Hedley, D., & Young, R. (2006). Social comparison processes and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with Asperger syndrome. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 10, 139–153.

Howlin, P., Goode, S., Hutton, J., & Rutter, M. (2004). Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(2), 212–229.

Howlin, P., & Moss, P. (2012). Adults with autism spectrum disorders. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57(5), 275–283.

Kamio, Y., Inada, N., & Koyama, T. (2013). A nationwide survey on quality of life and associated factors of adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Autism: the International Journal of Research and Practice, 17(1), 15–26.

Kanne, S. M., Gerber, A. J., Quirmbach, L. M., Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, D. V., & Saulnier, C. A. (2011). The role of adaptive behavior in autism spectrum disorders: Implications for functional outcome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(8), 1007–1018.

Kenworthy, L., Case, L., Harms, M. B., Martin, A., & Wallace, G. L. (2010). Adaptive behavior ratings correlate with symptomatology and IQ among individuals with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(4), 416–423.

Klin, A., Saulnier, C. A., Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, D. V., Volkmar, F. R., & Lord, C. (2007). Social and communication abilities and disabilities in higher functioning individuals with autism spectrum disorders: The Vineland and the ADOS. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(4), 748–759.

Lainhart, J. E., Bigler, E. D., Bocian, M., Coon, H., Dinh, E., Dawson, G. et al. (2006). Head circumference and height in autism: a study by the Collaborative Program of Excellence in Autism. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 140(21), 2257–2274.

LeCouteur, A., Rutter, M., Lord, C., Rios, P., Robertson, S., Holdgrafer, M., & McLennan, J. (1989). Autism diagnostic interview: A standardized investigator-based instrument. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 19(3), 363–387.

Liss, M., Harel, B., Fein, D., Allen, D., Dunn, M., Feinstein, C. et al. (2001). Predictors and correlates of adaptive functioning in children with developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(2), 219–230.

Lopata, C., Fox, J. D., Thomeer, M. L., Smith, R. A., Volker, M. A., Kessel, C. M. et al. (2012). ABAS-II ratings and correlates of adaptive behavior in children with HFASDs. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 24(4), 391–402.

Lopata, C., Smith, R. A., Volker, M. A., Thomeer, M. L., Lee, G. K., & McDonald, C. A. (2013). Comparison of adaptive behavior measures for children with HFASDs. Autism Research and Treatment, 2013, 415989. doi:10.1155/2013/415989.

Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook, E. H. Jr., Leventhal, B. L., DiLavore, P. C. et al. (2000). The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(3), 205–223.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P., Risi, S., Gotham, K., & Bishop, S. (2012). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-2nd edition (ADOS-2). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Corporation.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (1994). Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24(5), 659–685.

Lugnegard, T., Hallerback, M. U., & Gillberg, C. (2011). Psychiatric comorbidity in young adults with a clinical diagnosis of Asperger syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(5), 1910–1917.

Matthews, N. L., Smith, C. J., Pollard, E., Ober-Reynolds, S., Kirwan, J., & Malligo, A. (2015). Adaptive functioning in autism spectrum disorder during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(8), 2349–2360.

Pugliese, C. E., Anthony, L., Strang, J. F., Dudley, K., Wallace, G. L., & Kenworthy, L. (2015). Increasing adaptive behavior skill deficits from childhood to adolescence in autism spectrum disorder: Role of executive function. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(6), 1579–1587.

Shattuck, P. T., Narendorf, S. C., Cooper, B., Sterzing, P. R., Wagner, M., & Taylor, J. L. (2012). Postsecondary education and employment among youth with an autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics, 129(6), 1042–1049.

Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., & Baird, G. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(8), 921–929.

Smith, L. E., Maenner, M. J., & Seltzer, M. M. (2012). Developmental trajectories in adolescents and adults with autism: The case of daily living skills. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(6), 622–631.

Stone, W. L., Ousley, O. Y., Hepburn, S. L., Hogan, K. L., & Brown, C. S. (1999). Patterns of adaptive behavior in very young children with autism. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 104(2), 187–199.

Taylor, J. L., & Seltzer, M. M. (2011). Employment and post-secondary educational activities for young adults with autism spectrum disorders during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(5), 566–574.

Totsika, V., Felce, D., Kerr, M., & Hastings, R. P. (2010). Behavior problems, psychiatric symptoms, and quality of life for older adults with intellectual disability with and without autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(10), 1171–1178.

Wechsler, D. (1999). Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence. New York, NY: The Psychological Corporation.

Wechsler, D. (2011). Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence (2nd edition manual). Bloomington, MN: Pearson.

Woodman, A. C., Mailick, M. R., & Greenberg, J. S. (2016). Trajectories of internalizing and externalizing symptoms among adults with autism spectrum disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 28(2), 565–581.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program at NIMH, NIH under grant 1-ZIA-MH002920. We would like to express our gratitude to the individuals and families who volunteered their time to contribute to this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CKK designed the study, analyzed the data, wrote the initial draft of the paper, and participated in revising the manuscript and addressing the reviewers’ comments. LK and GLW provided support in developing the study design. LK, GLW, and AM assisted with manuscript writing and development. HP collected data, built the database, participated in data analysis, and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kraper, C.K., Kenworthy, L., Popal, H. et al. The Gap Between Adaptive Behavior and Intelligence in Autism Persists into Young Adulthood and is Linked to Psychiatric Co-morbidities. J Autism Dev Disord 47, 3007–3017 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3213-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3213-2