Abstract

Sixteen fathers of individuals with autism were interviewed to develop a grounded theory explaining how they learned about their children’s autism diagnosis. Results suggest the orientation process entails at least two phases: orienting oneself and orienting others. The orienting oneself phase entailed fathers having suspicion of developmental differences, engaging in research and education activities, having their children formally evaluated; inquiring about their children’s prognosis, and having curiosities about autism’s etiology. The orienting others phase entailed orientating family members and orienting members of their broader communities. Recommendations for responsive service provision, support for fathers, and future research are offered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Autism refers to a range of more specific diagnoses on the continuum of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). It is, “…characterized by severe and pervasive impairments in several areas of development that can include: reciprocal social interaction skills, communication skills, or the presence of stereotyped behavior, interests, and activities” (American Psychiatric Association [APA] 2013, p. 69). The autism diagnosis rate among children in the United States is one in 68 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2016). Research has documented that parents of individuals with autism experience an adjustment phase to their children’s needs and developmental trajectory (Hannon 2013, 2014; Hannon et al. 2017). Brobst et al. 2009; Davis and Carter 2008; Hastings et al. 2005; Meltzer 2008; Pottie and Ingram 2008; Seligman and Darling 2007). Fathers of individuals with autism, in particular, have been found to respond to their children’s needs differently than mothers for a range of reasons that include feeling stigmatized (Gray 2002, 2003) and considerations for their children’s social and occupational status (Heaman 1995; Seligman and Darling 2007). To better understand how fathers respond to their children’s unique needs and abilities, we endeavored to develop a theory about fathers’ orientation process to their children’s autism diagnosis.

Fathering Individuals with Autism

Becoming a father is a major cornerstone of adult development that affects men’s mental health (Lamb 2013). This process has been found to be both rewarding and stressful (Chin et al. 2011; Garfield et al. 2010; Shezifi 2004). The birth of a new child requires fathers to find different roles within their family systems (Chin et al. 2011), which contribute to feelings of pride and distress (Shezifi 2004). These changes for men can require shifts in attitude, disposition, can require an assessment of their resources and influence their mental health and wellness. Historically, American fathers from diverse groups have assumed roles in their nuclear families that have included authoritarian, financial provider, gender role model, decision-maker, protector, and partner supporter (McAdoo 1993; Palkovitz 2002; Pleck 1987).

Research about fathers of individuals with autism and other developmental differences has been limited (Seligman and Darling 2007). Studies that do include fathers have measured how parents describe autism’s influence on parenting, especially about parent stress levels (Davis and Carter 2008; Dunn et al. 2001; Hastings et al. 2005; Pottie and Ingram 2008); stress on partner/parent relationship and the potential for separation (Brobst et al. 2009; Freedman et al. 2012; Hartley et al. 2010), stigmatizing experiences (Gray 2002), and gender differences in coping style (Gray 2003). The literature has yielded a largely consistent finding that parenting children with autism is more stressful than parenting neuro-typical children and, arguably, more stressful than parenting children with other developmental differences. Another segment of the fathers of individuals with autism literature includes studies about the potential genetic link between children with autism and their biological fathers, particularly fathers categorized as having advanced paternal age (Ben Itzchak et al. 2011; Croen et al. 2007; Gerdts et al. 2013; Janecka et al. 2017; Lampi et al. 2013; Lundstrom et al. 2010; Sandin et al. 2016).

Comparative Studies on Gender Differences in Response to Stress

Sources of stress for parents of individuals with autism include: children’s social challenges (e.g., peer interactions), children’s capacity for emotion regulation, and parent–child relationship quality (Pottie and Ingram 2008). However, Davis and Carter (2008) found children’s emotion regulation problems are a primary trigger for stress in mothers, while children’s behavioral and interpersonal problems was a primary trigger for fathers’ stress. Research also suggests mothers and fathers influence each other’s stress levels and may contribute to parental separation. Hastings et al. (2005) found fathers’ stress about their children’s autism diagnoses was influenced more significantly by mothers’ depressive symptoms than by the children’s behavioral challenges.

One potential consequence of stress experienced by parents is risk for separation. However, the literature is inconsistent with findings about this potential (Freedman et al. 2012; Hartley et al. 2010). For example, Freedman et al. (2012) found parents of children with autism were not at an increased risk of living in households without two parents than children without autism. Hartley et al. (2010), however, compared the timing of divorce or separation in parents of children with autism with parents of neuro-typical children and found parents of children with autism had a higher rate of divorce.

Paternal Age and Autism

Janecka et al. (2017) recent review of epidemiological and molecular literature suggests that the association between later fatherhood and neurodevelopmental disorders is lacking. Furthermore, the authors recommend additional research that acknowledges the intersection of multiple mechanisms contributing to the etiology of autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Croen et al. (2007) analysis of 593 children with autism born between 1995 and 1999 found that advanced maternal and paternal ages were independently associated with autism diagnosis risk. Similarly, Ben Itzchak et al. (2011) found advanced parental age was associated in autism prevalence in 529 individuals with autism. Lundstrom et al. (2010) studied two nationally representative samples from the United Kingdom and Sweden to determine a relationship between paternal age and autism. The authors found that both cohorts showed a strong association between paternal age and risk for autism, with the oldest fathers showing an elevated risk for the diagnosis. Lastly, Lampi et al. (2013) investigated a total of 4713 cases of childhood autism to examine the associations between parental age and autism. Results suggested that advanced paternal age (i.e., 35–49 years old) was associated with childhood autism.

All of these studies offer glimpses about how fathers might describe their experiences and the biological relationship between them and their children with autism. However, few have intentionally sought to investigate these phenomena from fathers’ perspectives. Additionally, MacDonald and Hasting (2010) reported the vast majority of research on fathers of children with autism has used quantitative methodologies, creating a pathway for more research about fathers of individuals with autism with qualitative research designs.

Social and Cultural Capital Theoretical Framework

Social and cultural capital theory offers a useful perspective to interpret how fathers of individuals with autism learn about their children’s diagnoses. Bourdieu (1986) suggested capital (i.e., power, influence, resources) comes in three forms: economic, social, and cultural. Social and cultural capital can, at times, be leveraged when there is a dearth of economic capital. Social capital is resources and influence that come from people’s social connections or networks. Cultural capital is resources and influence that emerge from people’s possessions, whether inherent or acquired (e.g., educational attainment, skills, accent, clothing). Likewise, all of these forms of capital (i.e., economic, social, and cultural) can be used collectively to leverage social position for status, opportunity, and support.

Fathers of individuals with autism have been found to be acutely aware of their economic, social, and cultural capital (Seligman and Darling 2007; Hannon 2013; Hannon et al. 2017; Naseef 2001). Given past research that illustrates how boys and men from diverse groups are socialized to be good providers as fathers (McAdoo 1993; Palkovitz 2002; Pleck 1987), a social and cultural capital lens was fitting for this study. It is important to note that while fathers’ ability to provide includes financial support, it also includes provision in the form of disciplining, role modeling, and emotional support. However, given the diverse presentations of autism symptomology and the need for therapeutic care, financial provision can be a significant need. Garcia-Lopez et al. (2016) found autism symptom severity and family income were strong predictors of parents’ adjustment to their children’s needs.

This framework aligns with DeKanter’s (1987) conceptualization of fatherhood that acknowledges fathers’ intrapersonal negotiation of three levels: the person of the father (i.e., father’s embodiment), the position of the father (i.e., father’s socio-cultural capital), and the symbol of the father (i.e., the father’s role in the life of his child). We used a social and cultural capital theoretical lens to understand how fathers of individuals with autism engage with the process of learning about their children’s autism diagnosis given differences in parents’ responses to their children’s needs; fathers’ documented sensitivity to their roles as providers; and how little research exists about fathers’ experiences. Given these gaps in research about psychosocial aspects of autism, our study was intentionally designed to sample only fathers of individuals with autism to learn about their perspectives and experiences using a qualitative research methodology. This design provided an opportunity to more deeply understand fathering children with autism. As such, we addressed the question: how do fathers explain the process of learning about their children’s autism diagnoses?

Methods

Qualitative research aims to help understand specifics of particular cases and capture individuals’ points of view (Wang 2008). A qualitative approach provided us the opportunity to deeply understand this particular phenomenon by directly engaging fathers who are living it. Our choice for a grounded theory research design over other qualitative designs was to go beyond describing the phenomenon of fathers learning about their children’s diagnoses (e.g., phenomenology, narrative inquiry, ethnography), but to offer a possible explanation about their learning process. That is, the primary outcome of a grounded theory study is a, “theory with specific components: a central phenomenon, causal conditions, strategies, conditions and context, and consequences” (Corbin and Strauss 1990, p. 90). This is accomplished by developing and connecting categories of information based on properties of the phenomenon discerned during data collection and analysis (Creswell 2006; Strauss and Corbin 1990). Consequently, a theory emerges and is grounded in the data as they are systematically gathered and analyzed (Dey 2004; McLeod 2001; Miles and Huberman 1994; Strauss and Corbin 1990). Shyu et al. (2010) confirms the ability of the method to track and modify an emerging theory as new data appear and helps the theory maintain its relevance.

Participants

After receiving Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, fathers were recruited by advertising in a statewide autism advocacy organization in the northeastern region of the United States. Participants were offered a $40.00 gift certificate for fully participating in the study. Eligibility criteria required participants be fathers (i.e., biological, step-father, or in a fathering relationship) of individuals diagnosed with autism, be 18 years old or older, and speak and understand American English. A total of 16 fathers chose to participate after being provided informed consent documents for their review, approval, and signatures.

The fathers’ average age was 48.9 (range 32–67). Racially and ethnically, most fathers identified as White (n = 12) or White and Jewish, White and Spanish, or White and Arab-American. One participant identified as Black. Most fathers reported their highest completed level of education as college or higher (i.e., Associate’s degree through doctoral degree [n = 13]). The majority of fathers reported to be married to the biological mother of their children with autism (n = 12). The average of their children was 13.1 years old (n = 18; range 1.5–36). Fathers reported their children’s autism diagnosis as Autistic Disorder (n = 9), Asperger’s disorder (n = 3); Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (n = 3); Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified/Asperger’s Disorder (n = 2); and mild/moderate autism (n = 1).

Data Collection Procedures

Data were collected from fathers in one-time, semi-structured interviews conducted face to face or by web conferencing technology (e.g., Skype, Google Hangout) that averaged between 45 and 90 min. Interview questions broadly inquired about what actions, if any, did the fathers take to learn about their children’s diagnoses and if and how they chose to orient others about their children’s diagnoses. Additional questions included, but were not limited to, what does your child with autism do well? What are the most rewarding parts of being a father of a child with autism? What are the most challenging parts of being the father of a child with autism? How have your ideas and expectations about fatherhood evolved as a result of having a child with autism? The full interview protocol can be found in supplementary material. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist.

Data Analysis Procedures

Data analysis began with open coding throughout the data collection process, beginning after the third interview. The analysis required our detailed review of transcribed interviews to find codes, or discrete ideas, events, or experiences reflecting the fathers’ experiences with the learning process (e.g., therapies, grandparents, grief) (Corbin and Strauss 1990; Miles and Huberman 1994; Singh et al. 2010). Codes from the first three interviews facilitated the development of a codebook for subsequent interviews as basis of constant comparison to identify categories associated with more common, overarching concepts and determine any discrepancies between the open codes (Corbin and Strauss 1990; Singh et al. 2010).

Axial coding followed in the data analysis process, in which “categories are related to their sub-categories, and the relationships tested against data” to determine their confirmability (Corbin and Strauss 1990, p. 13). The higher-level categories (e.g., etiology, uncertain prognosis) were utilized to examine the relationships between open codes and contributed to the initial development of a grounded theory of the fathers’ orientation process. The third and last phase in our data analysis process was selective coding, to identify an overarching core category to highlight an explanatory whole representing the central phenomenon of the study and accounted for any variation in previously identified categories.

Trustworthiness strategies were integrated throughout the research process. For example, member checking (Lincoln and Guba 1995) with participants occurred at three separate points: during interviews (i.e., asking individuals for clarity and confirming understanding), after interviews (i.e., forwarding of transcripts for review and confirmation), and a findings summary (i.e., providing participants summary of findings for confirmation of our understanding). We maintained reflexive journals (Finlay 2002) to remain sensitized to our own biases and prejudices after every interview. Lastly, we engaged an external auditor throughout the data collection and analysis process for cross-checking to help ensure the interpretation of accurate findings and to reduce researcher error (Dey 2004; Morrow and Smith 2000).

Findings

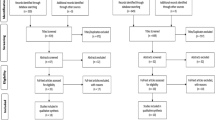

We identified a multi-step, multi-directional process associated with the all 16 fathers’ orientation to their children’s autism diagnosis that included two parts: orienting themselves and orienting others. The process of orienting themselves included: (1) having a suspicion of, or being informed of the children’s developmental differences; (2) engaging in research to educate themselves about autism (via a number of strategies described in more detail below); (3) decision for an evaluation for a (potential) formal diagnosis; (4) engaging in research and educating oneself on developmental differences (via a number of strategies described in more detail below); and, (5) inquiring about child’s prognosis (e.g., what will happen? How will s/he develop?); (6) curiosities about etiology (i.e. how did this happen and is it fixable?)

The second phase of the orientation process included orienting others, and could be summarized by the fathers having to address the question, who can/should I tell? This process entailed considering two specific categories of people to orient about the children’s diagnosis: (1) family (i.e., nuclear family and family of origin) and (2) community, or those in frequent contact with the family (e.g., education professionals, close friends, service providers, etc.).

Orienting Themselves

Suspicion of Differences

All of the fathers shared how they were suspicious about or informed of their children’s developmental differences. This came in the form of conversations with their partners/spouses, other parents, and/or consultations with professionals (e.g., medical, educational, etc.). Alan, a 50 year-old highly qualified teacher with a 6-year-old daughter, had suspicions about the potential for a diagnosis, described he and his wife’s decision to see a specialist, saying.

Yeah, so basically we went to see a developmental pediatrician, um, and again for me personally and my wife too at that point, it was just a formality for us to get the official diagnosis. At that point, it had become very clear.

Jeremy, 32 year old salesman with a 3 year old son, discussed his suspicions with his wife and said, “We started to think, I started to think before his second birthday that there might have been some things that were going on”. Another father described his suspicion as result of comparing his child’s development to friends who were parents. “At a very young age we started realizing that he wasn’t reaching the milestones which you would typically see, which we saw with our first child, which you would see with your associates’ children”. These examples are among many that highlight the start of these fathers’ orientation to their children’s diagnosis.

Research and Education Activities

The fathers all described how they began to educate themselves about autism. This research came in a number of ways that included intrapersonal (i.e., activities done alone) education (e.g., reading scientific articles, magazines, online resources, etc.) and interpersonal (i.e., activities with others) education (e.g., consultations with specialists, joining support groups, attending professional conferences). This part of the orientation process was most extensive and diverse. Ben, a pharmaceutical consultant whose son with autism is 23 years old, described both forms of research and education saying.

So how we reacted was to get ourselves educated as much as we could, you know, lots of reading. I attended lots of community meetings, local meetings, whatever meetings, given by whether it is the school or things like that, to figure out what services were available as well, and what were the options. We visited many, many schools as I mentioned. There are many specialized schools in this area. I think we visited all of them.

Charles, whose daughter with autism is 20 years old, described these activities decades ago.

It wasn’t like the Internet was like you could just go on—so we began to call around and somebody had told us about autism. I had heard of autism of course. I’d watched the movie Rain Man like everybody else had, right? I did not know much about it at all. So we began to research.

On the contrary, David, whose son with autism is 15, discussed how much he relied on the Internet for research and the role in his family as a problem solver.

I further oriented myself by doing tons of Internet research. I was an engineer, so growing up myself, I was the person in my household who was the arbitrator and the person that resolved conflict and solved problems, and I extended that into my career, and then I extended that into my family life.

Evaluation for Formal Diagnosis

The research and education process was generally followed by an intentional decision to seek a formal diagnosis by a specialist. The fathers discussed, in various ways, how they looked to get their questions answered or suspicions confirmed by an expert. Evan shared the diagnosis experience with twin children. “They were probably about 18 months old at that time, so it was really, really early. Then we got to the psychologist and started working through the whole procedure for the diagnosis.” Harrison, a stay at home father of a 15 year-old daughter with autism described the stress of seeing a variety of specialists—hampered by long appointment lists—to finally get his child’s formal diagnosis. He shared:

So we took her to a hearing doctor, and the hearing doctor found her behavior very bizarre, and he worried us a lot. He said, ‘There is something wrong with your daughter but it’s not hearing, and we, at that point, still didn’t have a clue’, and he recommended we see a specialist at the hospital in the audio department and a developmental pediatrician. At that point, we had no idea what a developmental pediatrician was and they scheduled us. I do remember that there was quite a wait, and when your kid has an issue, you know, every day seems like forever. I think we had to wait like six weeks. We tried to call everybody we knew to see if someone knew somebody, and we finally got a cancellation a few weeks later. They did a full, what I guess would be called a developmental profile. The developmental pediatrician saw her. A speech person saw her. An occupational therapist saw her, and after a little while of observing my daughter they were pretty sure, you know, they called – she had autism.

It is important to note that all of the fathers reported engaging in more research and education after news of their children’s diagnoses.

Inquiring about Child’s Prognosis

Predictably, all of the fathers discussed their concerns about their children’s developmental trajectory after the formal diagnosis. These inquiries reflected a desire to understand how to best support their children over the lifespan. Nathan, a psychologist by training with 36 year old son with autism, offered this example of being overwhelmed with his son’s potential prognosis.

I was familiar with people with learning disabilities and…I could make progress with them, so I was optimistic at the time my son gets diagnosed. [I thought to myself] Okay, I can do this. I can, if not cure him, make him a lot better.

Nathan also discussed the beginning of how he reconciled his son’s prognosis offering,

So I said to him [the doctor], can a child be part autistic? And he looked at me and he said, I’m not sure what you’re asking me, but can a woman be half pregnant? I was like, oh, no. And he said, [your son] he can learn, he can change, but he will always have autism. So I said, thank you doctor, and I walked out of there and I didn’t go back for a year.

Ben discussed the decision-making process of using medications for his son and how long they might be useful. He said,

I am pretty comfortable in dealing with doctors and medications and things, and we tried everything to be honest. We tried every potential medication at very low doses. He reacted and was very sensitive to all medication, even at very low doses. So the prognosis was encouraging from that point of view. It was obvious it would be a permanent condition.

Curiosities about Etiology

The fathers disclosed how, in the process of learning about their children’s autism diagnosis, they considered its etiology. Evan, the father of twins with autism, who also has autism, openly discussed his acceptance of how the condition may be genetic and present in his family for generations. He shared:

…the psychologist, early intervention folks, behaviorist, OT, and basically everyone that we worked with, [they] were suggesting that I go off and have the same evaluation done and that I take the ADOS [Autism Diagnosis Observation Scale] and see whether or not I have autism as well. There’s no question about it. There’s no magic about this. This is genetic. Your kids didn’t eat lead paint. They got it from you. You’re probably the one who has the traits, and you should probably go and do this, and I did that, and it made a pretty big difference.

Karl, whose son with autism is 12, discussed his curiosity about the relationship between autism diagnoses and vaccinations. He shared his speculations in the immediate time after his son was diagnosed with autism. He said,

You know, my sister is a scientist [and] years ago I remember thinking [there was] the link between autism and vaccines [and] we had long discussions about that….Not that I believed it at the time, but there are a lot of people who still do, unfortunately.

Coupled with the task of learning about their children’s diagnoses was orienting others about autism. This orientation took place with two specific groups that were categorized by family (e.g., nuclear family and family or origin) and community (e.g., those in frequent contact with the family). What follows is a presentation of the data confirming this interpretation.

Orienting Others

Orienting Family

The fathers in this study all discussed how they oriented members of their families. These were nuclear family members (i.e., spouses, children) and family of origin members (i.e., parents, brothers, sisters). Peter, an accountant with a 17 year old son, described the challenge in orienting his father to his son’s symptoms.

It’s not one of those things that you try to hide an issue. You know, if I’m going into a situation where I’m gonna be even with family—when my father was alive he always thought that James was going to one day poof it was going to be gone and he was going to grow out of it, you know. It was like ‘Dad, no, it’s not that way. I mean, this is who he is. Love him this way or not. Yeah, I know when he’s talking through the whole movie or you’re trying to watch the football game and he’s talking the whole time it’s driving you crazy, but this is who he is’.

Franklin, a college professor with a young son, shared the challenges of orienting several family members to understand his son’s differences.

My mom watches him the most outside of my wife and I. She was a special education teacher so she adjusted very quickly. I think she was in some denial too about the severity of the diagnosis…but in terms of like my father-in-law, he always wants to know is it [his behavioral issues] spectrum or is it the being young? Why won’t he hug me? To him I just have to say he’s developing in a different way than what you would normally expect.

He further elaborated, saying, “that’s something that my mother-in-law really struggles with. It is very hard for her to not get kisses from him, and my sister too.” Harrison recalled the challenge of orienting his parents to the behavioral interventions they implemented and the frustration of the interventions not being respected by his parents.

Like I said, my wife and I were very tough. When my mother would come over and hand her a toy just for not doing anything, which is what grandparents do, we would tell her no. Older people in general, again I’m sorry for stereotyping, didn’t understand what autism is.

Orienting Community

The fathers talked extensively about how they oriented their community about their children’s diagnoses. For the purposes of this study, community members were those in frequent contact with the children with autism. They included education professionals, service providers, friends, or even strangers who frequently patronized shared establishments in a community (e.g., grocery stores and other merchants). Matthew, a nonprofit organization manager who does extensive community work for children with disabilities, described how he oriented his son’s teachers and camp staff, noting.

We have a profile that we tell people to fill out to give to your teachers in September. It’s like a two page thing that you design about your child’s strengths, their weaknesses, and tips. I used that before he went to camp. For instance, you know, what to do when there’s loud music. You know, he has headphones. There are behavior tips about keeping the schedule. If you’re going to change the schedule, you really have to prep him for it.

Oliver, a 32 year old state police officer who has two sons, discussed orienting his older, neuro-typical son’s friends about his younger son’s autism diagnosis.

We tell all my older son’s friends that Benjamin has autism, and it means sometimes he might get anxious about situations. We explain some behaviors that might be associated with it, and we tell them, ‘hey, don’t take it personal. This is who he is. We’re working on it, but if you help us out, hey, he’s going to get better.’ And we’ve found that people, overall, are very receptive and want to help and they understand. So we explain to everybody who knows Antonio and knows us personally. We tell them what to expect, things that he might do, and we’ve had great success with that.

Charles articulated the differences in the orientation, depending on which community members needed it.

There’s two ways to orient someone. One is, if you are going to orient someone who is going to be working with her, that’s different than somebody you just run across in the street in passing. Sometimes I will explain to somebody something simple, especially if somebody is looking at her kind of strange in some type of social environment. I’ll say, ‘So this is my daughter Jennifer, she has autism.’ And I’ll just say that. Fortunately they respond with a lot of understanding. But if Jennifer is going to be working alongside or whatever, when we explain to them about her autism, then we’ll go into a little more detail. Typically, that would typically include something like, “Well, Jennifer has autism. She was diagnosed fairly young.” And I’ll even explain sometimes. Autism, the right and left hemispheres of the brain, there’s connectors and synapses that did not develop, so it’s an actual—to help explain a little bit of that.

These examples highlight the recursive and complex nature of this sample of fathers’ orientation to their children’s diagnosis. With these men it included using a frequent set of strategies to understand their children’s qualities, their unique challenges, and inherent strengths.

Discussion

The limited scholarship highlighting fathers’ experiences and perspectives about fathering individuals with autism yielded questions about what steps they take to understand their children’s diagnoses. For this study, we approached the reflections of 16 fathers of individuals with autism using grounded theory to account for how fathers orient themselves to and make meaning of their children’s autism diagnoses. The fathers uniformly shared how they engaged a specific set of activities that helped them understand the diversity of symptom presentation in their children and how, in turn, they learned to help others understand their children’s strengths and challenges. They discussed the value of conducting research in a number of ways (e.g., interpersonal and intrapersonal) in order to inform their perspectives about their children’s prognosis, while acknowledging their curiosities about cause of the diagnosis.

Social and Cultural Capital Theory, Fatherhood, and Autism

A social and cultural capital theory framework lends well to these findings. As fathers orient themselves to their children’s diagnoses, naturally occurring questions emerge in the family system about how to best meet the children’s needs and what resources are required to meet them. This becomes especially salient after the children receive formal diagnoses (i.e., Step 3). Garcia-Lopez et al. (2016) study highlighted how family income and symptom severity were strong predictors of parental adjustment to autism. As fathers become better oriented about the autism and their children’s therapeutic needs, the fathers and larger family system begin to determine how therapeutic needs will be met. This phenomenon speaks directly to fathers’ forms of capital and ability to provide for their children with autism as they are simultaneously being oriented to the diagnosis.

The fathers’ social and cultural capital can also influence their responses to their children’s prognosis (i.e., step 5) (Seligman and Darling 2007). Timing and access to resources (e.g., high quality of therapeutic care, reputable schools, etc.) are strongly correlated to quality of life for people with autism (Mandell et al. 2007). When fathers understand the relationship between their degree of social and cultural capital (e.g., location of residence, socio-economic status, educational attainment, social networks) and its potential influence on their children’s prognosis and quality of life, this orientation process becomes much more salient for them.

A social and cultural capital theory lens is relevant in the process of orienting others for fathers, particularly the process of orienting community. Fathers, providing for their children with autism in various ways (e.g., financially, emotionally, relationally, etc.), are often tasked with helping others understand their children’s unique needs and strengths (Hannon 2013). Community values where this orientation takes place can range from being accepting of or stigmatizing toward individuals with autism. Fathers’ social and cultural capital can, at times, influence where this orientation has to take place. That is, certain amounts of capital can influence community choice for programs, activities, and forms of support.

Given consistent findings about the stress associated with parenting individuals with autism, this study’s findings offer context about some stressors associated with this experience. For example, Rodrigue et al. (1992) found fathers of individuals with autism reported more negative effects on the parent–child relationship between fathers of individuals with autism than fathers of children with Down Syndrome or neurotypical children. The findings of this study suggest that as fathers become more knowledgeable about their children’s prognosis, knowledge may become a source of stress among fathers and negatively influence the parent–child relationship. Further, Brobst et al. (2009) found fathers of individuals with autism generally find less social support than mothers of individuals with autism. The inability to find support can be an additional stressor and reinforce fathers’ perceived need to be aware of their economic, social, and cultural capital to get their children the support they need by having a comprehensive knowledge about their children’s condition and being able to orient others to those needs.

This orientation process might also provide context when there is parenting/partner stress between parents of children with autism. Several studies have documented how mothers and fathers cope differently with challenges associated with parenting children with autism (Davis and Carter 2008; Freedman et al. 2012; Hastings et al. 2005). For children with more severe symptomology (e.g., limited expressive and receptive language, significant sensory input triggers, etc.), fathers’ sensitivity to their children’s occupational and social status (Seligman and Darling 2007) might contribute to tension between parents and yield concerns for their children being stigmatized and misunderstood (Gray 2002). Additionally, fathers in this study who predominantly identified as White, detailed the processes associated with their orientation which included the reliance and trust in behavioral health, mental health, and pediatric specialists. Hannon (2013) sampled a group of Black fathers discussed their orientation process in similar ways, who relied less on specialists for their orientation and more on their wives. These results may suggest a greater trust in the medical and behavioral health community among the fathers in this study than among Black fathers in Hannon’s (2013) findings.

The study’s findings also illustrate how questions about autism’s etiology are simultaneously relevant for fathers and for scientists. For some fathers, like Evan, he expressed reconciliation about his twins having autism, given his own (adult) autism diagnosis and his suspicions of his father being on the autism spectrum. Other fathers speculated about the relationship between vaccines and their children’s diagnosis. The important research investigating the potential relationship between advanced paternal age and autism prevalence is especially relevant for this sample, given the average age of the fathers in this study is approximately 49 years old and the average age of the children with autism is 13 year old.

Limitations of Study

Although this study contributes to the knowledge base on fathers of individuals with autism, there are limitations to the study. While a grounded theory study design does not seek to generalize its findings, the homogenous and small sample size limits the transferability of the findings (Creswell 2006). Another limitation in the study is researcher bias. The research team worked to address these biases through the use of reflexive journals, engaging an external auditor, and member checking throughout the data collection and analysis process.

Recommendations for Research and Practice

The present study offers a number of implications for supporting fathers of individuals with autism and research about fathers of individuals with autism. Research can expand to better understand fathers’ experiences and perspectives to inform practice. Qualitative and quantitative research that samples larger and more diverse fathers to determine the external validity of findings in this and similar studies is paramount. Additionally, comparing and contrasting the experiences of fathers from different racial and ethnic groups will be critical in developing culturally responsive practices and services to fathers of individuals with autism and their children. Understanding how the orientation process unfolds for siblings and mothers of individuals with autism will also contribute greatly to the knowledge base.

Training service providers (e.g., speech/language pathologists, school counselors, educational psychologists, etc.) should continue to include considerations for the entire family system as they make meaning of an autism diagnosis. The psychosocial aspects of autism for the family can influence academic performance in siblings of children with autism, the parenting relationship between parents of children with autism, and the larger extended family of the children with autism. This training must be inclusive of the diverse representation of American families that are parented by solo parents, gay and lesbian parents, and low and moderate income parents.

Conclusion

This study contributes to autism community’s knowledge about fathers raising children with autism. Their voices provide insight and awareness to an understudied population in order to guide further research and practice in working with family systems affected by autism diagnoses. The 16 fathers represented in this study help the readership better understand how they make meaning of their children’s developmental differences and inform interventions developed specifically for them, with a particular sensitivity to their social and cultural capital as providers for their families.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th edn.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Hannon, M. D. (2013). ‘Love him and everything else will fall into place’: an analysis of narratives of African-American fathers of children with autism spectrum disorders (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (Order No. 3576535).

Hannon, M. D. (2014). Smiles from the heart: humanistic counseling considerations for fathers of sons with Asperger’s disorder. Professional Counselor, 4(4), 363–377. doi:10.15241/mdh.4.4.363.

Hannon, M. D., White, E, & Nadrich, T. (2017). Influences of autism on fathering style among Black American fathers: A narrative inquiry. Journal of Family Therapy, 39(2), 1–23. doi:10.1111/1467-6427.12165.

Ben Itzchak, E., Lahat, E., & Zachor, D. A. (2011). Advanced parental ages and low birth weight in autism spectrum disorders—Rates and effect on functioning. Research in Developmental Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 32(5), 1776–1781.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The aristocracy of culture. Material Culture: Critical Concepts in the Social Sciences, 1(1), 164–193.

Brobst, J. B., Clopton, J. R., & Hendrick, S. S. (2009). Parenting children with autism spectrum disorders: The couple’s relationship. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(1), 38–49.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). National center on birth defects and developmental disabilities. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html.

Chin, R., Hall, P., & Daiches, A. (2011). Fathers’ experiences of their transition to fatherhood: A metasynthesis. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 29(1), 4–18.

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21.

Creswell, J. W. (2006). Qualitative research design: Choosing among five traditions (2nd edn.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Croen, L. A., Najjar, D. V., Fireman, B., & Grether, J. K. (2007). Maternal and paternal age and risk of autism spectrum disorders. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 161(4), 334–340.

Davis, N. O., & Carter, A. S. (2008). Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with Autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(7), 1278–1291.

DeKanter, R. (1987). A father is a bag full of money: The person, the position, and the symbol of the father. In T. Knijn & A. C. Mulder (Eds.), Unraveling fatherhood (pp. 6–26). Dordrecht: Foris.

Dey, I. (2004). Grounded theory. In C. Seale, G. Gobo, J. Gubrium, & D. Silverman (Eds.) Qualitative research practice (pp. 80–93). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dunn, M. E., Burbine, T., Bowers, C. A., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (2001). Moderators of stress in parents of children with autism. Community Mental Health Journal, 37(1), 39–52.

Finlay, L. (2002). “Outing” the researcher: The provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qualitative Health Research, 12(4), 531–545.

Freedman, B. H., Kalb, L. G., Zablotsky, B., & Stuart, E. A. (2012). Relationship status among parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A population-based study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(4), 539–548.

García-López, C., Sarriá, E., & Pozo, P. (2016). Multilevel approach to gender differences in adaptation in father-mother dyads parenting individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 28, 7–16.

Garfield, C. F., Isacco, A., & Bartlo, W. D. (2010). Men’s health and fatherhood in the urban Midwestern United States. International Journal of Men’s Health, 9(3), 161.

Gerdts, J. A., Bernier, R., Dawson, G., & Estes, A. (2013). The broader autism phenotype in simplex and multiplex families. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(7), 1597–1605. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1706-6.

Gray, D. E. (2002). ‘Everybody just freezes. Everybody is just embarrassed’: Felt and enacted stigma among parents of children with high functioning autism. Sociology of Health & Illness, 24(6), 734–749.

Gray, D. E. (2003). Gender and coping: The parents of children with high functioning autism. Social Science & Medicine, 56(3), 631–642.

Hartley, S. L., Barker, E. T., Seltzer, M. M., Floyd, F., Greenberg, J., Orsmond, G., & Bolt, D. (2010). The relative risk and timing of divorce in families of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(4), 449.

Hastings, R. P., Kovshoff, H., Ward, N. J., Degli Espinosa, F., Brown, T., & Remington, B. (2005). Systems analysis of stress and positive perceptions in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(5), 635.

Heaman, D. J. (1995). Perceived stressors and coping strategies of parents who have children with developmental disabilities: A comparison of mothers with fathers. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 10(5), 311–320.

Janecka, M., Mill, J., Basson, M. A., Goriely, A., Spiers, H., Reichenberg, A., et al. (2017). Advanced paternal age effects in neurodevelopmental disorders—Review of potential underlying mechanisms. Translational Psychiatry, 7(1), 9. doi:10.1038/tp.2016.294.

Lamb, M. E. (2013). The father’s role: Cross cultural perspectives. London: Routledge.

Lampi, K. M., Hinkka-yli-salomäki, S., Lehti, V., Helenius, H., Gissler, M., Brown, A. S., & Sourander, A. (2013). Parental age and risk of autism spectrum disorders in a Finnish national birth cohort. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(11), 2526–2535. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1801-3.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1995). Naturalistic inquiry (2nd edn.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lundström, S., Haworth, C. M. A., Carlström, E., Gillberg, C., Mill, J., Råstam, M., et al. (2010). Trajectories leading to autism spectrum disorders are affected by paternal age: Findings from two nationally representative twin studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(7), 850–856. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02223.x.

MacDonald, E. E., & Hastings, R. P. (2010). Mindful parenting and care involvement of fathers of children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 236–240.

Mandell, D. S., Ittenbach, R. F., Levy, S. E., & Pinto-Martin, J. (2007). Disparities in diagnoses received prior to a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(9), 1795–1802. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0314-8.

McAdoo, J. L. (1993). The roles of African-American fathers: An ecological perspective. Families in Society, 74(1), 28–35.

McLeod, J. (2001). Developing a research tradition consistent with the practices and values of counselling and psychotherapy: Why counselling and psychotherapy research is necessary. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 1(1), 3–11.

Meltzer, D. (2008). Explorations in autism: A psycho-analytical study (No. 3). London: Karnac Books.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Morrow, S. L., & Smith, M. L. (2000). Qualitative research for counseling psychology. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Handbook of Counseling Psychology (3rd edn., pp. 199–230). New York: Wiley.

Naseef, R. (2001). Special children, challenged parents: The struggles and rewards of raising child with a disability. Baltimore, MD: The Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company.

Palkovitz, R. (2002). Involved fathering and men’s adult development: Provisional balances. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Pleck, J. H. (1987). The theory of male sex-role identity: Its rise and fall, 1936 to the present. In H. Brod (Ed.) The Making of Masculinities. Boston: Allen and Unwin.

Pottie, C. G., & Ingram, K. M. (2008). Daily stress, coping, and well-being in parents of children with autism: A multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(6), 855.

Rodrigue, J. R., Morgan, S. B., & Geffken, G. R. (1992). Psychosocial adaptation of fathers of children with autism, down syndrome, and normal development. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 22(2), 249–263.

Sandin, S., Schendel, D., Magnusson, P., Hultman, C., Surén, P., Susser, E., et al. (2016). Autism risk associated with parental age and with increasing difference in age between the parents. Molecular Psychiatry, 21(5), 693–700. doi:10.1038/mp.2015.70.

Seligman, M., & Darling, R. B. (2007). Ordinary families, special children: A systems approach to childhood disability (3rd edn.). New York: Guilford Press.

Shezifi, O. (2004). When men become fathers: A qualitative investigation of the psychodynamic aspects of the transition to fatherhood. Unpublished doctorate dissertation. Alliant International University California, United States of America.

Shyu, Y., Tsai, J., & Tsai, W. (2010). Explaining and selecting treatments for autism: Parental explanatory models in Taiwan. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1323–1331. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-0991-1.

Singh, A., Urbano, A., Haston, M., & McMahan, E. (2010). School counselors’ strategies for social justice change: A grounded theory of what works in the real world. Professional School Counseling, 13(3), 135–145.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Wang, Y. W. (2008). Qualitative research. In P. P. Heppner, B. Wampold, & D. M. Kivlighan (Eds.), Research design in counseling (3rd edn., pp. 256–295). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere thanks to the Office of the Dean in the College of Education and Human Services at Montclair State University, assistants Jane Penola and Kelly Venezia for their support on this project, and to the fathers who so willingly shared their important stories.

Author Contributions

MDH conceived, designed, and coordinated the study, performed analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript. LVH performed analysis and interpretation of the data and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hannon, M.D., Hannon, L.V. Fathers’ Orientation to their Children’s Autism Diagnosis: A Grounded Theory Study. J Autism Dev Disord 47, 2265–2274 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3149-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3149-6