Abstract

Generalized anxiety and depression symptoms may be associated with poorer social outcomes among children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) without intellectual disability. The goal of this study was to examine whether generalized anxiety and depression symptoms were associated with social competence after accounting for IQ, age, and gender in typically developing children and in children with ASD. Results indicated that for the TD group, generalized anxiety and depression accounted for 38% of the variance in social competence and for children with ASD, they accounted for 29% of the variance in social competence. However, only depression accounted for a significant amount of the variance. The findings underscore the importance of assessing the social impact of internalizing symptoms in children with ASD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is primarily defined by impairments in social communication and restricted and repetitive patterns of interests and behaviours (American Psychiatric Association 2013). However, children with ASD are also at high risk for other medical and psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression. Anxiety is one of the most common comorbid conditions in ASD with reported prevalence rates ranging between 11 and 84% (White et al. 2009). Depression follows closely behind with prevalence rates ranging from 1.4 to 38% (Magnuson and Constantino 2011). Despite significant variability in the prevalence rates for anxiety and depression, psychiatric disorders are very common in children and youth with ASD (Mukkades et al. 2010; Simonoff et al. 2008). Youth with ASD without an intellectual disability (IQ > 85), in particular, show high rates of both anxiety and depression as compared to youths with ASD with intellectual disability and youth without ASD (Mayes et al. 2011).

One hypothesis is that youth with ASD without an intellectual disability may be more socially aware and have more social opportunities, but also experience a heightened risk for anxiety as their social environment becomes increasingly complex, their deficits more apparent, and they experience social failures (Bellini 2004; Kerns and Kendall 2013; Volkmar and Klin 2000). This hypothesis may also extend to depression symptoms as lower self-ratings of social competence have also been found to be associated with higher depression symptomatology (Vickerstaff et al. 2007). As children age their social environment becomes more complex which can exacerbate interpersonal challenges and increase the risk for mental health issues (e.g., internalizing symptoms) throughout development. However, the circumstances (i.e., complex social structures and individual constellation of interpersonal challenges each child experiences) that place children at risk for developing mental health challenges are not likely to occur abruptly but rather increase the risk for the development of mental health problems over time. Nevertheless, the relation between internalizing symptoms and social outcomes is likely bidirectional (Kerns and Kendall 2013) as mental health symptoms negatively impact social competence, and poor social competence may increase the risk for mental health problems in youth with ASD.

There are also significant conceptual (e.g., symptom overlap) and measurement issues to be considered when examining internalizing symptoms in youth with ASD, which is well documented in the case of anxiety. Assessment of anxiety in youth with ASD is challenging for several reasons, including (but not limited to) overlap in ASD and anxiety symptomatology (e.g., social avoidance), atypical presentation (e.g., more externalizing behaviours in ASD), language level requirements of existing measures which limit their suitability for this population, and lack of validated measures. Existing measures developed for typically developing (TD) populations rely on abstract concepts (e.g., time, emotions) and are not well suited for youth with ASD who may have limited self-awareness and insight into symptoms and emotions. For these reasons, the last several years have seen considerable debate in the field regarding how best to measure anxiety in youth with ASD (Grondhuis and Aman 2012; Lecavalier et al. 2014). For these reasons, as in this study, parent report has been the measure of choice with this population, although, there is evidence that self-report may be suitable for use with at least a subset of high functioning individuals with ASD (Mazefsky et al. 2011).

To date, much of the research examining the impact of anxiety on social outcomes, in TD children and children with ASD, has focused on social anxiety and thus, we know little about how other types of anxiety (e.g., Generalized Anxiety Disorder) and depression, common symptoms in children with ASD, may be implicated in social competence. Furthermore, the lack of validated measures to assess the construct of social competence in youth with ASD (Yager and Iarocci 2013) has limited investigations in this area (Gresham and Elliott 1990). The current study addresses a gap in the literature by examining whether generalized anxiety and depression symptoms are associated with social competence using a measure of social competence that has been validated for use with children with ASD.

Generalized Anxiety in ASD and TD

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is characterized by excessive worry (including anticipatory worry) about a variety of different events or activities (e.g., school) that the individual finds difficult to control. Furthermore, it is associated with feelings of restlessness, fatigue, difficulties concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance (American Psychiatric Association 2013). In one study, TD youth with GAD were rated similarly to their unaffected peers with regard to likelihood of having a best friend, rates of participation in club or group activities, and parent ratings of social competence despite having fewer friends overall (Scharfstein et al. 2011). In another study, comparing social skills and acceptance in TD children with social anxiety disorder and children with GAD, parents of both groups of children reported problems in the area of social skills, assertiveness, as well as challenges within interpersonal relationships. However, their peers rated the children with GAD positively on social acceptance (e.g., likability and friendship potential) suggesting that the GAD symptoms (e.g., negative misattribution of social situations, unrealistically high social performance standards) were not interfering with their peers’ acceptance of them (Scharfstein and Beidel 2015).

In a study examining the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in ASD, Simonoff et al. (2008) found GAD to be among the most commonly diagnosed comorbid disorders (13.4%) in this population. As with TD youth, few studies have examined how GAD (or GAD symptoms) may impact social outcomes in youth with ASD. In one study of children with ASD aged 7–11 (Chang et al. 2012) GAD severity (as measured by Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule severity ratings; ADIS; Silverman and Albano 1996) did not predict variability in parent rated social skills on the SSRS. In another study on the impact of internalizing symptoms on friendships, higher levels of anxiety and depression symptoms were associated with more dyadic friendships, even when controlling for IQ and level of autism severity (Mazurek and Kanne 2010). However, peer victimization was related to higher levels of generalized anxiety symptoms as well as several other variables such as depression, panic, social anxiety, and loneliness (Storch et al. 2012).

Depression in ASD and TD

Depression often co-occurs with anxiety in TD youth (Angold et al. 1999; Lewinsohn et al. 1997). A 25-year longitudinal study found that males (n = 372) and females (n = 463) aged 15 and older, presenting with both anxiety and depression symptoms were more likely to have a higher proportion of comorbid ICD-10 mental health disorders and a lower level of general functioning (Fichter et al. 2010). Depression symptomatology includes depressed mood, anhedonia and withdrawal from social activities, fatigue, irritability, feelings of worthlessness and guilt, lack of concentration, and suicidal ideation (American Psychiatric Association 2013), all of which may negatively impact social functioning. Depression is associated with negatively-biased social information processing and cognitive distortions (Beck 1967) which may contribute to maladaptive social attribution biases and promote more negative automatic thinking regarding social situations. Furthermore, higher self-reported depression symptoms in TD adolescents were associated with lower levels of self- and teacher- rated social competence (Dalley et al. 1994; Shah and Morgan 1996). A diagnosis of early onset, recurrent depression (defined as occurring before age 15) was associated with poorer adjustment, especially with regards to social outcomes later in adolescence and in early adulthood (Hammen et al. 2008). In adolescence, depression has been found to be a marker for future maladjustment, including substance use, educational underachievement, recurrent unemployment, early parenthood, as well as negative mental health outcomes such as later depression, suicidal behaviours, and anxiety (Fergusson and Woodward 2002).

Depression symptoms also figure prominently in the mental health risk profile of high functioning youth with ASD. Youth with ASD and intellectual disability may also experience depression, however, there are additional challenges inherent in measuring and understanding the expression of depressive symptoms in these youth due to difficulties in communicating their distress. High functioning youth with ASD may be more vulnerable to depression symptoms due to their greater social and self-awareness (Klin et al. 2005). For example, increased awareness of disability in youth with Asperger`s Disorder was shown to be related to higher levels of depression (Butzer and Konstantareas 2003). Similarly, lower levels of self-perceived social competence were associated with higher rates of depression in children with ASD (Vickerstaff et al. 2007). Depression symptoms also seem to co-occur with changes in ASD symptoms (Magnuson and Constantino 2011). In some cases these changes may be viewed as an improvement (e.g. a decrease in repetitive or obsessional behaviour) and mask the depression in these youth, whereas in other cases, the change in symptomatology may be associated with decreased adaptive functioning and self-care, increased compulsiveness, or self-injurious behaviour (Stewart et al. 2006). Regardless of the individual’s unique symptom presentation, the influence of depression symptoms, much like that of anxiety symptoms on social competence, may be bidirectional.

When examining anxiety and depression symptoms in children with ASD, it is important to control for variables such as age and IQ as potential risk factors for both anxiety and depression (e.g. Mayes et al. 2011). IQ is consistently associated with social outcomes in individuals with ASD (Howlin et al. 2004; Eaves and Ho 2008; Anderson et al. 2009). Specifically, older age and lower IQ are related to lower levels of self-rated social competence and higher levels of depression symptoms (Vickerstaff et al. 2007).

In the current study we used GAD and depression symptoms that are highly prevalent yet variable in children with ASD to predict the variability in social competence in children with ASD. Our study extends previous research in at least three ways: (1) we examined the influence of both GAD and depression symptoms on social competence; (2) we used the Multidimensional Social Competence Scale (MSCS) validated for use with children (7–18 years of age) with and without ASD (Yager and Iarocci 2013); (3) we compared children with ASD to TD peers of similar age and controlled for IQ, age, and gender in both TD and ASD samples. It was hypothesized that both generalized anxiety and depression symptoms would be associated with social competence for both groups of children over and above age, IQ, and gender. However, as compared to the TD children, we expected that generalized anxiety symptoms may be more predictive of social competence than depression symptoms in children with ASD due to the significant impact of anxiety on the relationships of children with ASD (Kelly et al. 2008).

Method

Procedure

The data utilized in this study was collected as part of a general clinical battery administered to each youth with ASD who participated in research in our university laboratory setting between 2012 and 2015. Participants were recruited from the community through a variety of means including participation in a summer camp, the promotion of research at community events, a lab website, and advertisements directed to parents who signed up to receive an annual lab newsletter. After obtaining consent, one of the youth’s parents was asked to complete a set of questionnaires while their child participated with a researcher in the next room to complete the IQ measure and other tasks included in the battery. After participating, families were compensated with a small honorarium.

Participants

Participants included 67 children with ASD (IQ > 70) and 67 TD children (IQ > 70) between the ages of 6 and 14 and their parents. The sample of participants with ASD included 57 males (85%) and 10 females (15%) and the sample of TD participants included 41 males (61%) and 26 females (39%).

Diagnosis

For each child participant with ASD a parent confirmed that their child had a clinical diagnosis of ASD and was receiving government funding for ASD. In the jurisdiction in which this data was collected, in order to qualify for funding from the Ministry of Children and Family Development Autism Funding Program children must be assessed by a pediatrician, psychologist, or psychiatrist trained to administer the ADI-R and ADOS (Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R); Le Couteur et al. 1989; Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS); Lord et al. 2001). As well, each child must fulfill the DSM criteria for ASD (American Psychiatric Association 2000). Diagnostic reports were obtained for all children with ASD for the purpose of confirming their ASD diagnosis.

The sample of children with ASD included 23 individuals (34%) that were diagnosed with an additional mental health disorder. This group consisted of 15 participants (22%) diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) or Attention Deficit Disorder, 6 participants (9%) with an Anxiety Disorder, 2 individuals diagnosed with a mood disorder (3%), and 1 participant diagnosed with an impulse control disorder (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder:1%). There were also 7 participants (10%) who had a learning disability or a language disorder. Of the 23 participants with ASD that had a comorbid condition, 8 of these individuals (34%; 12% of the entire ASD sample) had more than one comorbid condition. The sample of TD children had fewer mental health concerns. The sample included 2 individuals with ADHD (3%), 2 participants with OCD (3%), 1 participant with a diagnosis of an Anxiety Disorder (1%), 1 participant with a diagnosis of Oppositional Defiant Disorder (1%), and 1 participant with a learning disability (1%). Of the 7 TD participants with a mental health diagnosis, only 2 participants (28%; 3% of the entire TD sample) had more than one condition.

Measures

Social Responsiveness Scale

The SRS (Constantino 2002), a 65-item parent questionnaire presented in a Likert scale format (1–4) was used as a measure of autism symptoms in participants with and without ASD. The SRS was normed on a sample of over 1600 children between 4 and 18 years of age. On this measure, higher scores are indicative of more autism symptoms. The SRS has been demonstrated to have good internal consistency (αs are all between 0.94 and 0.97 which are considered to be good reliability for behavioural assessments; Constantino and Gruber 2005); good test–retest reliability (0.85 for males and 0.77 for females) and strong interrater reliability for all combinations of raters (mother–father, mother–teacher and father–teacher). Higher scores are strongly associated with a clinical diagnosis of ASD and represent higher levels of autism symptoms. Specifically, a T score of 60 through 75 represents a mild to moderate level of social impairment that is characteristic of children with high functioning ASD, and a T score of 76 or higher is most strongly associated with a clinical diagnosis of ASD (Constantino and Gruber 2005). Participants with ASD were expected to score high on this measure whereas the TD participants were expected to have scores within the Normal Range (T score below 60).

Behaviour Assessment System for Children, Second Edition

The Behaviour Assessment System for Children, Second Edition (BASC-2; Reynolds and Kamphaus 2004) includes parent-, teacher-, and self-report scales that are widely used to measure adaptive and problem behaviours in children and adolescents. Separate norms have been developed with very large samples for male and female youth in three different age categories (preschool, child, adolescent) for each type of form (parent-, teacher- and self-report). The parent-report scale was used to assess the youths’ anxiety and depression symptoms; it includes 150 questions with a four point response format (Never, Sometimes, Often, Almost Always) was used to rate the child’s behaviour. The BASC-2 provides both raw and T scores for an Internalizing Problems composite, including scales measuring anxiety and depression symptoms. The anxiety scale consists of general questions about worries including (but not limited to) worries about making mistakes, test performance, and pleasing others. The Anxiety subscale has good internal consistency reliability (αs > 0.81), as well as acceptable test–retest reliability (0.73 on the child form; 0.84 on the adolescent form) and interrater reliability (0.80 on the child form; 0.66 on the adolescent form). The depression subscale has strong reliability overall (αs > 0.85), good test–retest reliability (0.84 on the child form; 0.82 on the adolescent form), and acceptable interrater reliability (0.67 on the child form; 0.78 on the adolescent form; Reynolds and Kamphaus 2004). The BASC −2 was used to assess parent reported symptoms of generalized anxiety and depression.

Cognitive Assessment

In order to assess IQ, participants were administered the Stanford Binet Intelligence Scale 5th Edition, Abbreviated Battery (Roid 2003), or the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI; Wechsler 1999). Abbreviated full scale IQ scores were utilized as an approximation of intellectual functioning. Data on chronological age and gender were also collected.

Multidimensional Social Competence Scale

The Multidimensional Social Competence Scale (MSCS; Yager and Iarocci 2013) is a parent-rating scale that measures 7 distinct domains of social competence including social motivation, social inferencing, demonstrating empathic concern, social knowledge, verbal conversation skills, nonverbal sending skills, and emotion regulation. It includes 77 questions with a five point response format (Not True or Almost Never True, Rarely True, Sometimes True, Often True, Very True or Almost Always True). Higher scores on the MSCS are indicative of better social competence. The scale has good internal consistency reliability (αs > 0.84), as well as strong convergent validity with the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS; r = −0.89, p = .001), and good criterion related validity (e.g., large significant correlations with number of close friends, frequency of social contact with friends, and getting along with classmates). Importantly, the MSCS was shown to have good discriminant validity between cognitive ability and social competence.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for each of the variables in this study except for gender, which was unevenly distributed in both the ASD and TD samples, with the majority of the groups consisting of males (ASD: 57 males, 10 females; TD: 41 males, 26 females).

Participants with ASD were matched on age with the TD participants (mean age for both groups was 9 years; ranging between 6 and 13 years of age for the ASD group and 6 and 14 years of age for the TD group). Mean abbreviated intelligence scores for the ASD group was 102.59 and 108.85 for the TD group. There was a broad range of symptom severity on both generalized anxiety symptoms and depression symptoms in both ASD and TD groups, Nevertheless, means for the two groups were consistent with scores observed in a previous sample of TD/ASD youth using the BASC-2 (Volker et al. 2010). There was an especially high proportion of participants with ASD scoring over the at risk cutoff of 60T on both, which is indicative of clinically significant levels of generalized anxiety and depression. Specifically, in the ASD group, 48% of the sample for depression and 34% of the sample for generalized anxiety scored at or above the clinical cutoff of 60T. Further examination showed that of the 34 participants with ASD who were above the 60T cutoff for either depression or generalized anxiety symptoms, 59% of them were above the cutoff for both depression and generalized anxiety symptoms. In contrast, only 15% of the TD sample scored at or above the cutoff of 60T for depression and anxiety symptoms (15%). Of the TD participants who were above the cutoff for either depression or generalized anxiety symptoms, 33% of them were above the cutoff for both depression and generalized anxiety symptoms.

With regards to autism symptoms, 65 participants (97%) of the ASD group scored above 60T, placing them in the Mild to Moderate Range of severity. Scores in this range are indicative of significant and problematic impairment in everyday social interactions and are typical scores for youth with ASD. There were also 36 participants (54%) in the ASD sample who scored above 75T, placing them in the Severe Range. Scores in this range are indicative of severe and extremely problematic interference in everyday social interactions and is considered to be strong evidence of a clinically diagnosable ASD (Constantino and Gruber 2005). In the TD group, 10 participants had scores above 60T in the Mild to Moderate Range of Severity. According to the test developers, since the SRS measures the full range of severity seen in the general population, therefore, it is possible for some TD participants to fall at the higher end of this range, as is observed in this sample. On the MSCS, the mean rating was 204.95 for the ASD group and 281.88 for the TD group, indicating higher social competence for participants in the TD group.

Correlation Analyses

In order to test the associations between each of the variables, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for all continuous variables and a point biserial correlation was calculated for correlations including gender. Before any analyses were conducted, the data was examined for outliers 3 standard deviations above or below the mean and none were found to exist. Tables 2 and 3 provide a summary of correlation analyses as follows. As would be expected, in both groups, generalized anxiety (GA) and depression (D) were strongly positively correlated with each other (TD: r = .67, p = .000 < 0.01; ASD: r = .60, p = .000 < 0.01), and were also positively correlated with SRS scores (TD D: r = .61, p = .000 < 0.01; ASD D: r = .60, p = .000 < 0.01; TD GA: r = .26, p = .036 < 0.05; ASD GA: r = .49, p = .000 < 0.01), indicating that higher internalizing symptoms were associated with higher levels of social impairment in both groups. Consistent with this, higher levels of generalized anxiety and depression were also negatively correlated with MSCS scores for children with ASD (D: r= − 0.56, p = .000 < 0.01; GA: r = −0.41, p = .001 < 0.01; in contrast with the SRS, higher MSCS scores are associated with better social competence). For TD participants, this was true for depression scores, but not for generalized anxiety scores, which was in the expected direction but not significant (D: r = −0.61, p = .000 < 0.01; GA: r = −0.19, p = .134 > 0.05).

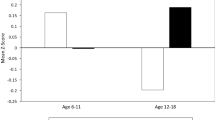

Generalized anxiety and depression were not significantly associated with IQ for either group. Depression was not correlated with age in either group, and generalized anxiety was not correlated with age in the TD group, but was in the ASD group; for children in the ASD group older children had higher levels of generalized anxiety (ASD GA: r = 0.26, p = .034 < 0.05). Finally, depression was not associated with gender for either group, and generalized anxiety was not associated with gender in the ASD group but was in the TD group (TD GA: r = −0.31, p = .010 = 0.01), with boys demonstrating higher levels of anxiety in this group. Higher levels of social competence (SC) were not found to be related to age in either group or gender. However, higher levels of social competence was associated with higher IQ in the TD group (TD SC: r = 0.33, p = .006 < 0.01), but not in the ASD group; which suggests that IQ may be associated with SC for TD children but not for children with ASD.

Regression Analyses

Two ordinary least square multiple regression analyses were used to examine the relations between generalized anxiety and depression symptoms (controlling age IQ and gender) and the outcome variable, social competence.

TD Group

For the TD group, regression analyses indicate that the variables in Model 1 (age, IQ, and gender) explain a statistically significant proportion of the variance in SC (R2 = 0.147, F(3,63) = 3.621, p = 0.018 < 0.05). T tests show that IQ has the only statistically significant regression coefficient in the model (IQ: β = 0.302, t63 = 2.498, p = .015 < 0.05; age: β = 0.081, t63 = 0.670, p = .505 > 0.05; gender: β = 0.180, t63 = 1.537, p = .129 > 0.05) meaning that the association between IQ and SC is statistically significant even after controlling for age and gender. These results are consistent with the previous correlation analyses that indicated that age and gender were not significantly related to social competence in this group, in contrast, IQ was moderately associated with social competence. Model 2, included generalized anxiety and depression blocked together, which accounted for an additional 38% of the variance in social competence (ΔR2 = 0.375, ΔF(2,61) = 13.33, p = .000 < 0.01). T tests show that both depression (β = −0.829, t61 = −6.806, p = .000 < 0.01) and generalized anxiety contributed to the statistical significance of the model (β = 0.438, t61 = 3.505, p = .001 < 0.01). See Table 4 presents a summary of the final regression model at step 2.

ASD Group

Regression analyses show that the variables in Model 1 (age, IQ, and gender) did not explain a statistically significant proportion of the variance in social competence (R2 = 0.038, F(3,63) = 0.837, p = .479 > 0.05). T tests show that none of the covariates modeled in Block 1 are statistically significant (IQ: β = −0.081, t63 =−0.652, p = 0.517 > 0.05; age: β = −0.191, t63 = −1.472, p = 0.146 > 0.05; gender: β = −0.011, t63 =− 0.083, p = 0.934 > 0.05). These results are consistent with the previous correlation analyses that indicated that IQ, age, and gender were not significantly related to social competence in the ASD group. Model 2, included generalized anxiety and depression blocked together, which accounted for an additional 29% of the variance in social competence (ΔR2 = 0.293, ΔF(2,61) = 13.35, p = 0.000 < 0.01). T tests show that depression (β = −0.506, t61 = −3.748, p = 0.000 < 0.01) was the only statistically significant regression coefficients in the model; age, gender, and generalized anxiety were not statistically significant. See Table 5 for a summary of the final regression model at step 2.

Discussion

Generalized Anxiety Symptoms in ASD and TD

The aim of the present study was to explore the relations between generalized anxiety, depression symptoms and social competence in children with ASD without intellectual disability and their age matched TD peers. In the current sample of children with ASD, which included a subset of individuals diagnosed with an anxiety disorder (6 participants; 9% of the sample), 34% fell in the clinically significant range for generalized anxiety symptoms on the BASC-2, which is well within the range observed in the previous literature examining prevalence rates of anxiety in ASD. In contrast, the TD sample, which included only 1 participant previously diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, contained a far fewer 15% of children who fell in the clinically significant range for generalized anxiety symptoms.

In both groups, generalized anxiety symptoms were found to be significantly negatively correlated with parent-rated social competence in the expected direction; that is, higher generalized anxiety was associated with poorer social competence as rated by the MSCS. Similarly, generalized anxiety was also found to be associated with higher levels of autism symptoms (as rated by the SRS) in both groups. Mazurek and Kanne, (2010) previously found that anxiety was associated with better social outcomes in children with ASD, however, in their study item 65 on the ADI-R (which inquires about the presence of a best-friend relationship) was used as the outcome measure whereas in the current study, the outcome was a parent-rated measure of social competence. Measures for anxiety and depression were also different; Mazurek and Kanne, (2010) used the anxiety/depression scale on the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach and Rescorla 2001) which includes questions assessing both anxiety and depression, whereas in the current study the BASC-2 anxiety and depression subscales assessed the independent contributions of each of these variables in the prediction of social competence.

Results from hierarchical multiple regression analyses did not support our hypothesis but rather indicated that generalized anxiety was only associated with social competence above age, IQ, and gender in the TD group, but not in the ASD group. Unlike social anxiety, which may be more relevant to social functioning in children with ASD, generalized anxiety may not be related to social outcomes (Ginsburg et al. 1998; Chang et al. 2012) in the same way as it is in TD children. Although generalized anxiety may have some social features such as worrying about what others think, generalized worry is more abstract, broad and distributed across different contexts. For instance, generalized anxiety may include worry about school work, worry about making mistakes, worry about something bad happening, and can also be accompanied by general feelings of nervousness, tenseness, and fearfulness. In contrast, features associated with social anxiety such as strong avoidance and withdrawal from social situations likely contribute to much higher levels of social difficulties in these individuals. Individuals with social anxiety may have more negative attributions of other’s social behaviour which may further contribute to social challenges and poorer social outcomes (Chang et al. 2012). Alternatively, generalized anxiety in children with ASD may present as worry related to uncontrollable or unknown events and the available parent-reported questionnaire measures may not be adequately capturing generalized anxiety in children with ASD.

Consistent with previous findings in ASD, age was positively associated with higher levels of generalized anxiety symptoms only in the ASD group (e.g. Mayes et al. 2011). However, gender was associated with higher levels of generalized anxiety only in the TD group, with boys experiencing higher levels of anxiety than girls. This is not consistent with previous findings of higher rates of anxiety symptoms in TD girls than boys (Hale et al. 2011; Crocetti et al. 2015; Leikanger et al. 2012). However, our finding may be an artefact of the low ratio of females to males in our group given that we attempted to have a comparable gender distribution in both the TD and ASD groups. Given the small number of females in this study, it was underpowered to detect any significant effect of gender. Further research is needed to determine whether different risk factors may be present for ASD (e.g. age) and TD (e.g. gender) youth for generalized anxiety symptoms.

Depression Symptoms in ASD and TD

In the current sample of children with ASD, approximately 48% had clinically significant levels of depression on the BASC-2; however, only two participants were previously formally diagnosed with a mood disorder. In contrast, the TD sample, which did not contain any children previously diagnosed with a mood disorder, contained a far fewer 15% of children who fell in the clinically significant range for depression symptoms.

The BASC-2 depression scale includes several items that pertain to social symptoms of depression in TD youth such as withdrawal and problems related to social interactions and friendships that are also key features of ASD. Thus, we sought to explore whether the participants with ASD were scoring highly on the depression scale as a result of parents endorsing only social items (e.g., feeling that they are not understood or well-liked by others), or were also reporting other ‘core’ symptoms of depression measured on this scale such as negative emotionality, self-dislike, and suicidal ideation. BASC-2 depression items were examined separately to determine the proportions of parents who were reporting social and ‘core’ symptoms. It was determined that both social as well as ‘core’ features of depression were endorsed by parents in this sample, thus, the high depression scores in the youth with ASD were not solely based on the social difficulties associated with depression (Table 6).

Results from hierarchical multiple regression analyses indicated that depression was strongly significantly predictive of social competence in both groups over and above age, IQ, and gender. For children with ASD, depression was the only statistically significant predictor of social competence in the final model, however, for TD children, both generalized anxiety and depression symptoms contributed after considering the covariates. Depression symptoms often include social disengagement, irritability, and reduced ability to think or concentrate (American Psychiatric Association 2013), any one of which could adversely influence social competence. Consistent with this picture, as with generalized anxiety symptoms, higher levels of depression symptoms were also associated with more autism symptoms and high levels of depression were associated with higher levels of generalized anxiety, as expected.

In the current sample of children with ASD, over 54% of the participants scored in the severely socially impaired range, as indexed by the SRS scores. Despite significant social difficulties, the mean IQ (102) was within the average range. Research has suggested that higher cognitive abilities and self-awareness in high functioning youth with ASD may also be risk factors for developing depression (Mazurek and Kanne 2010). In a study of 22 children with ASD between the ages of 7 and 13, Vickerstaff et al. (2007) found that higher cognitive abilities and insight led to lower self-reported social competence and higher levels of depression symptoms. In contrast to this, in our TD and ASD samples, IQ was not found to be significantly associated with depression symptoms. However, IQ was found to be associated with lower levels of autism symptoms in the TD sample and also emerged as a significant predictor of social competence in this group, indicating that IQ may function as a protective factor in the developing of social competence, at least in TD children.

Limitations and Future Research

This study was limited by the exclusive use of parent ratings to evaluate social competence, social impairment, generalized anxiety symptoms and depression symptoms. In the case of anxiety, this is not ideal because there is evidence that children’s perceptions of their anxiety symptoms can differ from parents’ perceptions (e.g., Baldwin and Dadds 2007; Blakeley-Smith et al. 2012). High functioning youth with ASD, in particular, may be able to accurately report their psychiatric symptoms and self-report should be explored as a unique source of information for the assessment and treatment of youth with ASD (Meyer et al. 2006; Ozsivadjian et al. 2013). However, measures may need to be developed or adapted to better assess symptoms of anxiety or depression in youth with ASD (e.g., including the use of visual material to make abstract concepts more concrete, reducing language requirements, and including observable (i.e., behavioural/physiological) measures of symptomatology (e.g., increased breathing rate). Further, incorporating behavioural observations as well as multiple reporters (e.g., peer-, teacher-, and self-report) in measuring the variables of interest would provide a more comprehensive picture of the relations between mental health symptoms and social competence. It may be advantageous to consider mixed methods to assess social competence including quantitative (e.g., frequency of contact, number of contacts) and qualitative techniques (e.g., in-depth interview about mental health).

In future research it is important to consider that the relations between social difficulties and mental health symptoms are likely reciprocal in nature, that is, increased symptoms may be associated with increased social difficulties which in turn are associated with a further increase in symptoms. For example, increases in self-reported loneliness and depression symptoms in adolescents with Asperger’s syndrome were predicted by the degree of conflict and betrayal in their friendships (Whitehouse et al. 2009).

In the current study, only two participants in the ASD sample had a diagnosis of a depressive disorder yet we found a high number of depression symptoms in the sample, suggesting that depression symptoms may remain undetected by professionals. One reason for this could be that certain clinical features observed in depressed individuals, such as social isolation and withdrawal, overlap with behaviours associated with ASD, and therefore may not be as noticeable. Assessment of anxiety in ASD is also challenging due to symptom overlap between the two disorders. In the case of anxiety and depression, atypical symptom presentation, such as increased agitation and aggressiveness, increased repetitive behaviours, or compulsiveness, may make detecting symptoms of either disorder in youth with ASD particularly challenging for clinicians (Magnuson and Constantino 2011; Kerns and Kendall 2013). In addition, individuals with ASD often struggle in the area of communication and may have less self-awareness and emotional insight into their symptoms, which may also make it more difficult to detect both anxiety and depression in this population (Magnuson and Constantino 2011).

Due to the small number of females in this study, we were not able to adequately explore the effect of gender with regard to anxiety, depression and social competence. However, we know from studies of TD youth that gender plays an important role in internalizing symptoms and social competence and should be investigated in youth with ASD. Additionally, with only a moderate sample size of n = 67 in each group, the current study is underpowered to differentiate the independent effects of anxiety and depression on social competence.

In sum, the current findings suggest that in children with ASD without intellectual disability anxiety and depression symptoms and poor social competence are best monitored and evaluated concurrently.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: An integrated system of multi informant assessment. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families

American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision (4th edn) Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th edn.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Anderson, D. K., Oti, R. S., Lord, C., & Welch, K. (2009). Patterns of growth in adaptive social abilities among children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(7), 1019–1034. doi:10.1007/s10802-009-9326-0.

Angold, A., Costello, E. J., & Erkanli, A. (1999). Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(01), 57–87. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00424.

Baldwin, J. S., & Dadds, M. R. (2007). Reliability and validity of parent and child versions of the multidimensional anxiety scale for children in community samples. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(2), 252–260. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000246065.93200.a1.

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimental and theoretical aspects. New York: Harper & Row.

Bellini, S. (2004). Social skill deficits and anxiety in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 19(2), 78–86. doi:10.1177/10883576040190020201.

Blakeley-Smith, A., Reaven, J., Ridge, K., & Hepburn, S. (2012). Parent–child agreement of anxiety symptoms in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(2), 707–716.

Butzer, B., & Konstantareas, M. M. (2003). Depression, temperament and their relationship to other characteristics in children with Asperger’s disorder. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 10(1), 67–72. http://www.oadd.org/publications/journal/issues/vol10no1/download/butzer&konstantareas.pdf.

Chang, Y., Quan, J., & Wood, J. J. (2012). Effects of anxiety disorder severity on social functioning in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 24(3), 235–245. doi:10.1007/s10882-012-9268-2.

Constantino, J. N. (2002). The Social Responsiveness Scale. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Constantino, J. N., & Gruber, C. P. (2005). Social responsiveness scale. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Crocetti, E., Hale, W. W. III, Dimitrova, R., Abubakar, A., Gao, C. H., & Pesigan, I. J. A. Generalized anxiety symptoms and identity processes in cross-cultural samples of adolescents from the general population. Child & Youth Care Forum, 44(2), 159–174). doi:10.1007/s10566-014-9275-9.

Dalley, M. B., Bolocofsky, D. N., & Karlin, N. J. (1994). Teacher-ratings and self-ratings of social competency in adolescents with low- and high-depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 22(4), 477–485. doi:10.1007/BF02168086.

Eaves, L. C., & Ho, H. H. (2008). Young adult outcome of autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(4), 739–747. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0441-x.

Fergusson, D. M., & Woodward, L. J. (2002). Mental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(3), 225–231. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.225.

Fichter, M. M., Quadflieg, N., Fischer, U. C., & Kohlboeck, G. (2010). Twenty-five-year course and outcome in anxiety and depression in the upper Bavarian longitudinal community study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 122(1), 75–85. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01512.x.

Ginsburg, G. S., La Greca, A. M., & Silverman, W. K. (1998). Social anxiety in children with anxiety disorders: Relation with social and emotional functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26(3), 175–185. doi:10.1023/A:1022668101048.

Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (1990). The Social Skills Rating System. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Grondhuis, S. N., & Aman, M. G. (2012). Assessment of anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(4), 1345–1365.

Hale, W. W., Crocetti, E., Raaijmakers, Q. A., & Meeus, W. H. (2011). A meta-analysis of the cross-cultural psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(1), 80–90. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02285.x.

Hammen, C., Brennan, P. A., Keenan-Miller, D., & Herr, N. R. (2008). Early onset recurrent subtype of adolescent depression: Clinical and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 433–440. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01850.x.

Howlin, P., Goode, S., Hutton, J., & Rutter, M. (2004). Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(2), 212–229. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x.

Kelly, A. B., Garnett, M. S., Attwood, T., & Peterson, C. (2008). Autism spectrum symptomatology in children: The impact of family and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(7), 1069–1081. doi:10.1007/s10802-008-9234-8.

Kerns, C. M., & Kendall, P. C. (2013). The presentation and classification of anxiety in autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Psychology, 19(4), 323–347. doi:10.1111/cpsp.12009.

Klin, A., McPartland, J., & Volkmar, F. R. (2005). Asperger syndrome. In F. R. Volkmar, R. Paul, A. Klin & D. Cohen (Eds.), Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders: Vol 1. Diagnosis, development, neurobiology, and behavior (3rd edn., pp. 88–125). Hoboken: Wiley.

Le Couteur, A., Rutter, M., Lord, C., Rios, P., Robertson, S., Holdgrafer, M., & McLennon, J. (1989). Autism diagnostic interview: A standardized investigator-based instrument. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 19(3), 363–387.

Lecavalier, L., Wood, J. J., Halladay, A. K., Jones, N. E., Aman, M. G., Cook, E. H., & Sullivan, K. A. (2014). Measuring anxiety as a treatment endpoint in youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(5), 1128–1143. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1974-9.

Leikanger, E., Ingul, J., & Larsson, B. (2012). Sex and age-related anxiety in a community sample of Norwegian adolescents. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 53(2), 150–157. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2011.00915.x.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Zinbarg, R., Seeley, J. R., Lewinsohn, M., & Sack, W. H. (1997). Lifetime comorbidity among anxiety disorders and between anxiety disorders and other mental disorders in adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 11(4), 377–394. doi:10.1016/S0887-6185(97)00017-0.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., & Risi, S. (2001). Autism diagnostic observation schedule. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Magnuson, K. M., & Constantino, J. N. (2011). Characterization of depression in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 32(4), 332–340. doi:10.1097/DBP.0b013e318213f56c.

Mayes, S. D., Calhoun, S. L., Murray, M. J., Ahuja, M., & Smith, L. A. (2011). Anxiety, depression, and irritability in children with autism relative to other neuropsychiatric disorders and typical development. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 474–485. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2010.06.012.

Mayes, S. D., Calhoun, S. L., Murray, M. J., & Zahid, J. (2011). Variables associated with anxiety and depression in children with autism. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 23(4), 325–337. doi:10.1007/s10882-011-9231-7.

Mazefsky, C. A., Kao, J., & Oswald, D. P. (2011). Preliminary evidence suggesting caution in the use of psychiatric self-report measures with adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 164–174. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2010.03.006.

Mazurek, M. O., & Kanne, S. M. (2010). Friendship and internalizing symptoms among children and adolescents with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(12), 1512–1520. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1014-y.

Meyer, J., Mundy, P., Van Hecke, A., & Durocher, J. (2006). Social attribution processes and comorbid psychiatric symptoms in children with Asperger syndrome. Autism, 10(4), 383–402. doi:10.1177/1362361306064435.

Mukkades, N. M., Herguner, S., & Tanidir, C. (2010). Psychiatric disorders in individuals with high-functioning autism and Asperger’s disorder: Similarities and differences. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 11, 964–971.

Ozsivadjian, A., Hibberd, C., & Hollocks, M. (2013). Brief report: The use of self-report measures in young people with autism spectrum disorder to access symptoms of anxiety, depression and negative thoughts. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(4), 969–974. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1937-1.

Reynolds, C. R., & Kamphaus, R. W. (2004). BASC-2: Behavior assessment system for children, manual (2nd edn). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Roid, G. H. (2003). Stanford binet intelligence scales (5th edn.). Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing.

Scharfstein, L., Alfano, C., Beidel, D., & Wong, N. (2011). Children with generalized anxiety disorder do not have peer problems, just fewer friends. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 42(6), 712–723. doi:10.1007/s10578-011-0245-2.

Scharfstein, L. A., & Beidel, D. C. (2015). Social skills and social acceptance in children with anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(5), 826–838. doi:10.1080/15374416.2014.895938.

Shah, F., & Morgan, S. B. (1996). Teacher’s ratings of social competence of children with high versus low levels of depressive symptoms. Journal of School Psychology, 34(4), 337–349. doi:10.1016/S0022-4405(96)00019-2.

Silverman, W. K., & Albano, A. M. (1996). The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-Child and Parent Versions. San Antonio, TX: Graywinds Publications.

Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., & Baird, G. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(8), 921–929. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f.

Stewart, M. E., Barnard, L., Pearson, J., Hasan, R., & O’Brien, G. (2006). Presentation of depression in autism and Asperger syndrome: A review. Autism, 10(1), 103–116. doi:10.1177/1362361306062013.

Storch, E. A., Larson, M. J., Ehrenreich-May, J., Arnold, E. B., Jones, A. M., Renno, P., Fujii, C., Lewin, A. B., Mutch, P. J., Murphy, T. K., & Wood, J. J. (2012). Peer victimization in youth with autism spectrum disorders and co-occurring anxiety: Relations with psychopathology and loneliness. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 24(6), 575–590. doi:10.1007/s10882-012-9290-4.

Vickerstaff, S., Heriot, S., Wong, M., Lopes, A., & Dossetor, D. (2007). Intellectual ability, self-perceived social competence, and depressive symptomatology in children with high-functioning autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(9), 1647–1664. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0292-x.

Volker, M. A., Lopata, C., Smerbeck, A. M., Knoll, V. A., Thomeer, M. L., Toomey, J. A., & Rodgers, J. D. (2010). BASC-2 PRS profiles for students with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(2), 188–199. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0849-6.

Volkmar, F. R., & Klin, A. (2000). Diagnostic issues. In A. Klin, F. R. Volkmar & S. Sparrow (Eds.), Asperger syndrome (pp. 25–71). New York: Guilford Press.

Wechsler, D. (1999). The Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

White, S. W., Oswald, D., Ollendick, T., & Scahill, L. (2009). Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(3), 216–229. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.003.

Whitehouse, A. J. O., Durkin, K., Jaquet, E., & Ziatas, K. (2009). Friendship, loneliness and depression in adolescents with asperger’s syndrome. Journal of Adolescence, 32(2), 309–322. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.03.004.

Yager, J., & Iarocci, G. (2013). The development of the multidimensional social competence scale: A standardized measure of social competence in autism spectrum disorders. Autism Research, 6(6), 631–641. doi:10.1002/aur.1331.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Strategic Initiative in Health Research (STIHR): Autism Research Training Program to the first author and a Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) Scholar Award to the second author. We would like to thank Dr. Rachel Fouladi for her helpful comments at various stages of the study.

Author contributions

KJ and GI designed the study. KJ assisted with data collection, performed statistical analyses, interpreted the data, and writing the manuscript. GI coordinated data collection, assisted with interpretation of the data, and in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Grant number 41020100282).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Johnston, K.H.S., Iarocci, G. Are Generalized Anxiety and Depression Symptoms Associated with Social Competence in Children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder?. J Autism Dev Disord 47, 3778–3788 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3056-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3056-x