Abstract

The factors predicting stress, anxiety and depression in the parents of children with autism remain poorly understood. In this study, a cohort of 250 mothers and 229 fathers of one or more children with autism completed a questionnaire assessing reported parental mental health problems, locus of control, social support, perceived parent–child attachment, as well as autism symptom severity and perceived externalizing behaviours in the child with autism. Variables assessing parental cognitions and socioeconomic support were found to be more significant predictors of parental mental health problems than child-centric variables. A path model, describing the relationship between the dependent and independent variables, was found to be a good fit with the observed data for both mothers and fathers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parents of children with autism face unique challenges not faced by other parental groups. Children with autism can be difficult to understand, due to their atypical interpersonal responsiveness (e.g. reluctance to engage, verbally or physically, with caregivers) and patterns of communication (e.g. repetitive or illogical phrasing) (Busch 2009). Children with autism can also seem ‘impossible to reach’, a term used by Busch (2009) to describe the perception parents report of being unable to form a reciprocal relationship with their child(ren) with autism. Post-diagnosis, parents express feeling unsupported and stigmatized by both medical professionals and members of the community (Lamminen 2008; Wright and Williams 2007), and report being uncertain about the future impact of the diagnosis upon both themselves and the functioning of their family unit (Woodgate et al. 2008). Parents can also report deterioration in marital satisfaction (Rogers 2008) and a feeling of loss regarding the impact the diagnosis will have on their future life opportunities (Myers 2009).

It has been clearly demonstrated in the existing literature that the parents of children with autism report more mental health problems than the parents of children in other clinical and/or non-clinical groups (Benjak 2009; Bitsika and Sharpley 2004; Kuusikko-Gauffun et al. 2013; Micali et al. 2004; Singer 2006). Obviously this has an impact on the parents themselves. However, it also has a secondary impact on the child. Moore (2009), in a survey of the parents of 220 children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD), found that parents were much more likely to adhere to medical treatment recommendations than behavioural treatment recommendations for their child. Moore argued that the observed disparity was partly due to the emotional challenge inherent in following through with behavioural management programs for a child with autism. The elevated levels of mental health problems experienced by this parental group may reduce their capacity to manage such challenges, thus negatively impacting their ability to implement programs of arguable benefit to their child(ren) with autism.

Thus supporting families with children with autism is not solely a question of setting an effective behavioural management program for the child. It also requires an understanding of the pressures being placed on the parent, and the parents’ capacity to implement those recommendations. It has been demonstrated, as discussed above, that the parents of children with autism experience more mental health problems than the parents of developmentally normal children. However, without a clear understanding of the factors predicting reported mental health problems, structuring effective support services for families remains a challenge.

A considerable body of research already exists investigating the factors predicting stress, anxiety and depression in the parents of children with autism. Although a number of factors have been identified as predictive of parental mental health problems, such as perceived and actual stigmatization (Farrugia 2009), and physical well-being (Bitsika and Sharpley 2004), the majority of studies have focused on three core predictive variables—autism symptom severity, child externalizing behaviours and social support.

A number of authors have argued that autism symptom severity in the child is the primary predictor of mental health problems in the parent (Duarte et al. 2005; Hastings and Johnson 2001; Hastings et al. 2005). Duarte et al. (2005) compared the mothers of 31 children with autism recruited from mental health clinics with the mothers of 31 children without mental health problems, and reported that autism symptom severity was significantly correlated with maternal stress. In a study of 141 parents conducting home-based behavioural interventions, Hastings and Johnson (2001) also found a significant positive correlation between autism symptom severity and parental stress. However, both these studies recruited parents requesting specialized support services for their child with autism. The sample groups in these studies are thus not necessarily reflective of the general population of parents with children with autism. Studies recruiting directly from the community have found that autism symptom severity is not as predictive of maternal stress as factors such as child behaviour problems (Davis and Carter 2008; Hastings et al. 2005).

Behavioural problems in the child with autism have been identified in a number of other studies as a significant predictor of parental mental health problems (Civick 2008; Fiske 2009; Gray 2003; Lecavalier et al. 2005; Tomanik et al. 2004). A study conducted by Lecavalier et al. (2005) of the parents of 293 children with ASD found a strong positive correlation between child behaviour problems and stress, although there was little agreement among participants on the definition or extent of behaviour problems exhibited by this group of children, making it difficult to generalize from the results. Civick (2008) asked parents to provide a rating of their child’s externalizing behaviours (using a standardized scale), and concluded that externalizing behaviours positively predicted parental stress ratings for both mothers and fathers of children with autism. Although focused on mothers with children diagnosed by an independent practitioner with a pervasive developmental disorder (as opposed to solely autism), Tomanik et al. 2004 study of 60 mothers also found that child maladaptive behaviour accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in maternal stress.

A third factor identified in the existing literature as a key predictor is social support. In a study of 172 parents of children with autism, Gray and Holden (1992) found that both fathers and mothers who received more social support had lower scores of depression, anxiety and anger. Lamminen (2008) also reported that social support had a significant negative relationship with perceived parental stress in the parents of children with autism. In a mail survey study of 219 Australian parents with children with autism, Sharpley et al. (1997) concluded that, although social support was associated with lower levels of parenting stress, it was mediated by the perceived expertise of the family member or friend providing respite care for the parents.

However, a problem with comparing results across the studies listed above is the inconsistency in the inclusion of independent variables. Whereas some studies have included multiple independent variables, no existing studies have included autism symptom severity, child behavioural problems and social support in the same analysis. Thus, although each variable may well be predictive of parental mental health problems when analysed in isolation, a significant predictive relationship may not exist when each factor is assessed in the presence of other variables. Additionally, there are a number of potentially predictive factors that have not been assessed in the existing body of literature. A study in children with an intellectual disability suggested that parental cognitions (primarily parental locus of control and satisfaction with parenting) accounted for most of the variance in parental stress (Hassall et al. 2005). However, this study has not been replicated in the parents of children with autism. Similarly, perceived parent–child attachment, although shown to be a significant predictor of parental stress (Hoppes and Harris 1990), has not been assessed in the context of other potential predictors of anxiety, stress, and depression in parents of children with autism.

Another factor that requires consideration, especially with a view to developing effective support programs, is gender difference. Although a number of studies indicate that mothers of children with autism experience higher levels of mental health problems than fathers (Gray and Holden 1992; Hastings et al. 2005; Sharpley et al. 1997), others have argued that the observed mental health problems differ across gender. Rogers (2008) concluded that fathers tend to be comparatively unaffected by their child’s symptoms and behaviours and affected primarily by their spouse’s disposition and level of stress. Davis and Carter (2008), however, contradicted this finding, reporting that paternal stress was significantly affected by their child with autism (specifically by externalizing behaviours exhibited by that child), whereas maternal stress was associated with practical and time management problems. Fiske (2009) again reported a different finding, concluding that child externalizing behaviours equally affected the perceived stress of both mothers and fathers, but that reminders of their child’s long term diagnosis increased general and parenting stress for fathers, but not for mothers. Other studies have found that fathers of children with autism perceive there to be less support from family and friends than their partners (Altiere and von Kluge 2009) and demonstrate fewer adaptive coping skills than mothers (Lee 2009). As divorce rates are significantly higher in parents of children with autism compared to parents of developmentally normal children (Hartley et al. 2010), developing a clearer understanding of the differential pattern of predictors of mental health problems across gender, and using this to develop tailored support programs, would have clear practical benefit.

As stated by Keen et al. (2010), preserving parents’ good health and well-being is a precondition for the optimal care of children with autism. However, if supportive interventions are to be effective, it is essential that the factors predicting stress, anxiety and depression, the three primary mental health variables identified as elevated in this parental group, are clearly understood. Existing research identifies that social and economic support, child maladaptive behaviour and autism symptom severity correlate with mental health problems in this parental group. However, no existing study has included all of these factors together and assessed the comparative contribution of each. The current literature has also not investigated the role played by perceived parent–child attachment, a factor, based on the existing research into attachment behaviours in autistic children, which may also play a role in predicting parental mental health problems. Additionally, parental locus of control and parenting satisfaction, variables shown to be highly predictive of stress in the parents of children with intellectual disability, have not been included in similar studies in autism. The present study includes all these variables, allowing an assessment of the comparative contribution of each in predicting parental mental health problems. Finally, for any interventions targeted at parents with mental health problems to be effective, an understanding of the different pattern of predictive factors across gender is needed. Although existing research has indicated there is a difference between the experience of mothering and fathering a child with autism, no existing studies have looked in detail at the different factors predicting mental health problems across the maternal and paternal groups.

The primary aims of this study are thus twofold—firstly to evaluate the factors predictive of anxiety, stress and depression in separate samples of mothers and fathers with one or more children with a diagnosis of autism or ASD, and secondly to use this information to propose and analyse a model describing the relationship between these predictive factors. It was hypothesised that the variance in parental stress, anxiety and depression associated with conduct problems in the child, social support and autism symptom severity (factors shown, when regressed alone, to be significant predictors of parental mental health problems) may be better explained by other variables. It was also hypothesised that the pattern of predictors would differ across dependent variables, and also differ across parental gender. To achieve the first aim of the study, separate cohorts of mothers and fathers of children with autism completed a questionnaire assessing both mental health problems and factors possibly predictive of those mental health problems. Stepwise regression analysis was used to reduce the number of predictors that provided the comparatively greatest predictive relationships with each dependent variable (stress, anxiety and depression), so as to build a model to test as part of the second aim. To achieve the second aim the results of the regression analysis were used to propose a path model describing the relationship between independent and dependent variables. Invariance testing across gender was used to assess for consistency in the predictive model for mothers and fathers of children with autism.

Method

Participants

Participants were parents with one or more children aged between 4 years 0 months and 17 years 11 months with a diagnosis of ASD (parental report). A diagnosis of ASD usually involves a multi-disciplinary team, often including a psychologist, a paediatrician and a speech or language pathologist. Diagnosis focuses on interviews with parents and teachers, and observation of the child, and incorporates the use of standardised assessment tools, such as the Autism Diagnostic Interview (Lord et al. 1994). Due to the scale of this study, it was not feasible to conduct ASD assessments for all children and instead parental report was relied upon to confirm a diagnosis of autism. Parents were asked to confirm the child they were reporting on had received a diagnosis of autism or Autism Spectrum Disorder from a registered health professional. An affirmative answer to this question was required to proceed with the questionnaire.

Participants were recruited directly from the community. Mothers and fathers were recruited separately, and were not matched parenting dyads. The study was promoted via Facebook, and recruitment to the study was international. Prior to initiation of the online questionnaire, parents were requested to indicate consent for data to be used. Participants were informed that they could withdraw from participation at any time prior to submission of the online questionnaire. Consent was implied in the submission of the questionnaire. Ethics approval was granted prior to commencement of the study.

Data collection for mothers and fathers occurred separately, using comparative data collection procedures. In total 392 mothers and 387 fathers responded to the questionnaire. 273 participants (120 mothers and 153 fathers) were discounted because they did not complete the questionnaire in full or reported on children outside the specified age range. The sample incorporated with the present study therefore comprised 250 mothers and 229 fathers. The mean age of participating mothers was 39.86 years (range 24–58 years; SD = 6.33 years). The mean age of participating fathers was 41.66 years (range 21–65 years, SD = 6.97 years). The mean age of the children with autism reported on by the participants was 8.38 (range 4–17 years; SD = 3.89 years). Each participant was requested to complete an online questionnaire. When answering questions related to a child with autism, participants were instructed to only respond based on one child with autism (if the participant reported having more than one child with the diagnosis), and to report on the same child for all relevant sections of the questionnaire, ensuring consistency across measures (i.e. that individual parental scores across each measure related to the same child with autism).

Materials

In addition to providing demographic information, participants completed a 12 item questionnaire, developed for the current study, assessing participant perception of social and economic support. Questions took the form of statements, focused on family support (e.g. ‘You get the emotional help and support you need from your family,’); extra-familial support (e.g. ‘You can count on your friends when things go wrong.’), economic support (e.g. ‘You have some friends or family who are willing and able to help you financially’) and support related specifically to their child with autism (‘You have some family or friends who help you care for your child(ren) with autism.’) Participants responded to each statement by indicating the extent of their agreement along a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “Strongly agree”. Ten of the questions in the questionnaire related to ‘social support’. A final score for ‘social support’ was calculated by adding the individual scores for each of these ten questions. The other two questions were totalled to provide a score for ‘economic support.’ Possible scores for social support ranged from 0 to 50, with higher scores indicating a higher perceived level of received social support. The Cronbach’s alpha score for internal consistency for the 10 ‘social support’ items was 0.90. Possible scores for economic support ranged from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating a higher perceived level of received economic support. The Cronbach’s alpha of internal consistency for the two questions providing a measure of ‘economic support’ was 0.84.

To provide consistency across measures and allow inter-measure comparison, this study used the same clinical measure for all three mental health variables, the short-form Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond and Lovibond 1995). Internal reliability for the DASS-21 using Cronbach’s alpha is reported to be 0.88 for the Depression scale, 0.82 for the Anxiety scale, 0.90 for the Stress scale and 0.93 for the Total scale (Henry and Crawford 2005). The Cronbach’s alpha of internal consistency for the DASS-21 for this study was 0.91.

Autism symptom severity was assessed using the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ; Rutter et al. 2003). The SCQ is designed as a screening tool to identify children who would benefit from a full autism diagnostic review (Rutter et al. 2003) and was used as a validity check for parental reports of child Autism or ASD. In studies assessing reliability across age groups, the SCQ has demonstrated a Cronbach’s Alpha index of internal consistency ranging from 0.84 to 0.93. In studies assessing reliability across diagnostic categories, the Cronbach’s Alpha index of internal consistency (by group) ranges from 0.81 to 0.92 (Rutter et al. 2003). The Cronbach’s alpha of internal consistency for the SCQ for this study was 0.80.

To overcome the need for direct observation in calculating the child’s mental age, three questions devised by the study authors were used to indicate the developmental age of the child (an abbreviated tool was used in place of an existing measure due to the length of the study questionnaire). The items were administered in a yes/no format, and scored cumulatively (providing a maximum score of ‘3’ if an answer of ‘yes’ was provided to all three questions.) The questions were as follows: “Is she/he able to dress independently, or without considerable assistance from someone else? (Note: needing help to tie shoelaces would not be considered ‘considerable assistance’)”; “Is she/he able to go to the toilet independently, or without considerable assistance from someone else? (Note: needing to be reminded to wash hands or flush the toilet would not be considered ‘considerable assistance’)”; and “Is she/he able to bath/shower independently, or without considerable assistance from someone else? (Note: needing help turning on the shower or running the bath would not be considered ‘considerable assistance’).” A cumulative of score of ‘0’ or ‘1’ across these 3 questions was interpreted in the current study to indicate a comparatively low developmental age. The Cronbach’s Alpha index for internal consistency for the Developmental Age measure was 0.79.

Child maladaptive problem behaviours (‘conduct problems’) were assessed using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman 2001.) Ten questions from the SDQ were incorporated into the questionnaire for the current study, corresponding to the subscales for conduct problems and hyperactivity. Separate scores for ‘hyperactive behaviour’ and ‘conduct problems’ were calculated from the raw data, by combining the scores for the five respective questions in each domain, as recommended by factor analysis of the SDQ (Goodman 2001). Possible scores for both hyperactive behaviour and conduct problems ranged from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of perceived behaviour problems. Alpha scores of internal consistency in this study were 0.65 for ‘hyperactive behaviour’ and 0.66 for ‘conduct problems.’

An additional statement, ‘Often aggressive or violent towards adults’ was included, separate to the questions from the SDQ, to assess violent behaviour towards adults displayed by the child. For this item parents were again asked to select one of “Not True”, “Somewhat True” and “Certainly True.” Answers to this question were assigned a value from ‘0 to ‘2’ and scored separately to the SDQ. A score between ‘0’ and ‘2’ was calculated for each child, based on the answer to this question, and scored as ‘aggressive behaviour.’

Parental perception of parent–child attachment was assessed using the Parent–Child Relationship Inventory (PCRI; Gerard 1994). Three of the seven PCRI subscales focus on parent–child interaction and perception of parenting, and were considered relevant to the objectives of this study. These subscales were satisfaction with parenting, involvement (parent perception of involvement and ‘closeness’ to child—‘perceived parental involvement’), and limit setting (parental perception of their ability to set limits for their child—‘perceived limit setting ability’). Reports of the PCRI’s reliability (Gerard 1994) have demonstrated adequate psychometric properties. Tests of internal consistency of all subscales have yielded Cronbach’s alphas above 0.70 with a median value of 0.82 (Gerard 1994). The Cronbach’s alpha of internal consistency for the PCRI for this study was 0.84.

Parental locus of control, a variable indicated as predictive of mental health problems in the parents of children with intellectual disability (Hassall et al. 2005) was assessed using the Parental Locus of Control Scale (PLOC; Campis et al. 1986). Tests of internal consistency for the PLOC have provided Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient’s for each factor of 0.75 (parental efficacy), 0.77 (parental responsibility), 0.67 (child control of parent’s life), 0.75 (parental belief in fate/chance) and 0.65 (parental control of child’s behaviour), and a total scale reliability coefficient of 0.92 (Campis et al. 1986). The Cronbach’s alpha of internal consistency for the PLOC for this study was 0.90.

In total, data was collected for seventeen variables demonstrated in one or more previous studies to be potentially predictive of mental health problems in the parents of children with autism, Down syndrome or intellectual disability. These variables were sex of child, marital status, employment status, number of children with autism, age of parent, age of child, social support, economic support, hyperactive behaviour, conduct problems, aggressive behaviour, autism symptom severity, developmental age, perceived limit setting ability, satisfaction with parenting, perceived parental involvement (with the child with autism) and parental locus of control.

Regression Analyses—Results

Prior to the regression analyses, each independent variable was individually regressed against each dependent variable. Only independent variables which significantly predicted one or more dependent variables were included in subsequent analyses. Based on initial analyses, the following variables were demonstrated to have no significant predictive relationship with the dependent variables—sex of child, marital status, employment status and number of children with autism. These variables were therefore excluded from further analysis. The stepwise regression analyses were used to reduce the number of predictors of the dependent variables (stress, anxiety and depression) and identify the combination of independent variables which best predicted each dependent variable. Given that; (a) all the variables in the study have been chosen based on past research showing associations with the dependent variables; (b) the purpose was to reduce the number of predictors so that a parsimonious model could be proposed (Argyrous 2000), and (c) this model was to be validated using path analysis techniques, stepwise regression is an acceptable analytic method for such variable reduction (Field et al. 2012; Tabachnik and Fidell 2012).

Descriptive Statistics

Means and standard deviations for the 13 independent variables included in the stepwise regression analysis are as shown in Table 1.

The mean scores for depression, anxiety and stress in fathers of children with autism were all lower than the comparative scores in mothers of children with autism. The mean scores for both mothers and fathers were all within the ‘Moderate’ range for stress, anxiety and depression (Lovibond and Lovibond 1995). However, drawing further conclusions regarding the differences between the two populations may be misleading. The populations were recruited independently, and do not contain any matched co-parenting dyads.

Correlation Analysis

Correlations between variables were calculated using Pearson Correlation Coefficients. Correlation statistics for the 3 dependent variables and 13 independent variables included in the regression analyses are shown in Tables 2 and 3 below.

Stepwise Regression Analysis

Stepwise regression was employed to regress the 13 predictors listed in Tables 2 and 3 above against depression, anxiety and stress for both mothers and fathers. For each analysis, statistical criteria for entry was a probability of F ≤ 0.05, with the criteria for subsequent removal probability of F ≥ 0.1. Before interpretation, general assumptions of multiple regression were tested for the final models. VIF was less than 10 and Tolerance greater than 0.2 for all variables indicating an absence of colinearity in data (Bowerman and O’Connell 1990; Menard 2002). The Durbin–Watson test indicated that the independence of errors assumption was upheld. Further analysis revealed no evidence of heteroscedasticity, and that distribution of errors was normal. From these analyses the models were deemed to meet the assumptions of multiple regression, and thus the models were accepted.

Stepwise Models for Depression

The variables shown to significantly predict depression in the mothers of children with autism, as described in the final step of the stepwise regression model, are reported in Table 4.

Three independent variables, social support, parental locus of control and aggressive behaviour, were shown to be significant predictors of material depression.

The variables shown to significantly predict depression in the fathers of children with autism, as described in the final step of the stepwise regression model, are reported in Table 5.

Three independent variables, social support, perceived limit setting ability and satisfaction with parenting, were shown to be significant predictors of paternal depression.

Stepwise Models for Anxiety

The variables shown to significantly predict anxiety in the mothers of children with autism, as described in the final step of the stepwise regression model, are reported in Table 6.

Three independent variables, autism symptom severity, perceived limit setting ability and mother’s age, were shown to be significant predictors of maternal anxiety.

The variables shown to significantly predict anxiety in the fathers of children with autism, as described in the final step of the stepwise regression model, are reported in Table 7.

Three independent variables, perceived limit setting ability, social support and aggressive behaviour, were shown to be significant predictors of paternal anxiety.

Stepwise Models for Stress

The variables shown to significantly predict stress in the mothers of children with autism, as described in the final step of the stepwise regression model, are reported in Table 8.

Six independent variables, perceived limit setting ability, mother’s age, autism symptom severity, social support, parental locus of control and economic support, were shown to be significant predictors of maternal stress.

The variables shown to significantly predict stress in the fathers of children with autism, as described in the final step of the stepwise regression model, are reported in Table 9.

Three independent variables, perceived limit setting ability, social support and father’s age, were shown to be significant predictors of paternal stress.

Regression Analyses—Discussion

Although the existing literature has identified that conduct problems, autism symptom severity and social support significantly predict stress, anxiety or depression in the parents of children with autism (Civick 2008, Gray 2003; Gray and Holden 1992; Lecavalier et al. 2005; Schieve et al. 2007), there is an inconsistency in both the dependent and independent variables used across the existing studies. It was hypothesised in this study that the variance in parental stress, anxiety and depression associated with these factors may be better explained by other variables. It was also hypothesised that the pattern of predictors would differ across dependent variables, and also differ across parental gender.

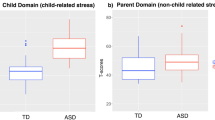

The results of the regression analyses support the hypotheses. Of the 13 variables included in the analysis, a combination of three was shown to be the best predictor of maternal depression—namely aggressive behaviour, parental locus of control and social support. Aggressive behaviour was a positive predictor of depression, and social support and parental locus of control were negative predictors (i.e. the more limited the social support and the more external the mother’s perceived locus of control, the higher the reported depression score). For maternal anxiety, a very different model was observed. Again, three variables were shown to significantly predict maternal anxiety, namely maternal age (a negative predictor, with younger mothers being more likely to report high levels of anxiety), autism symptom severity and perceived limit setting ability (which, again, was a negative predictor of maternal anxiety). The predictive model for maternal stress was a combination of the predictive models for maternal depression and anxiety. Five of the six variables predictive of depression and anxiety also significantly predicted stress (the variable shown to be a significant predictor of depression, but not included in the model for stress, was aggressive behaviour). Based on the results of the analysis, the predictive relationship between dependent and independent variables, for mothers of children with autism, can be described as shown in Fig. 1.

The predictive models for fathers of children with autism, in contrast to the result for mothers, showed comparative consistency across dependent variables. Social support and perceived limit setting ability were significant negative predictors of all three dependent variables in the fathers of children with autism. For each predictive model (for depression, anxiety and stress), there was a single additional variable shown to be significant. For paternal depression, this was shown to be satisfaction with parenting (a negative predictor), for paternal stress it was father’s age (like maternal age, this was a negative predictor, with younger fathers reporting higher levels of stress); and for paternal anxiety, this was aggressive behaviour. Based on the observed results, the predictive relationship between dependent and independent variables for the fathers of children with autism can be described as shown in Fig. 2.

A key point to note from these results is that conduct problems, a variable shown in the existing literature to be a significant predictor of parental mental health problems in the parents of children with autism (Civick 2008; Fiske 2009; Gray 2003; Duarte et al. 2005; Hastings and Johnson 2001; Lecavalier et al. 2005; Tomanik et al. 2004), was not shown to be a significant predictor of stress, anxiety and depression for either mothers or fathers in this study. Similarly, autism symptom severity, another variable shown to be predictive of mental health problems in this parental group (Duarte et al. 2005; Hastings and Johnson 2001; Hastings et al. 2005), was shown to be a significant predictor of maternal stress and anxiety, but did not predict maternal depression or paternal mental health problems. The regression analysis conducted in this study would suggest that the variance in parental mental health problems contributed by child conduct problems and autism symptom severity may be explained by other variables.

In five of the six regression analyses carried out in the present study, variables assessing reported social and economic support were shown to be significant predictors of parental mental health problems (with the exception being maternal anxiety). Variables assessing parental cognitions were also shown to have a significant predictive relationship with parental mental health problems. Parental perception of their ability to set effective limits for their child was shown to be a significant predictor in five of the six regression analyses undertaken, with perceived locus of control being a significant predictor in maternal depression (the one dependent variable not negatively predicted by perceived limit-setting ability). These results suggest that the relationship between ‘child-centric’ factors (such as externalizing behaviours and autism symptom severity) and parental mental health problems may be mediated by social/economic support and parental cognitions, with significant implications for support services for this parental group. Many documented support programs for this parental cohort tend to focus on the child, providing strategies to help the parent manage externalizing behaviours, and providing psychoeducation on autism and its behavioural and developmental implications (Keen et al. 2010; Tonge et al. 2006). However, it may be that such support is leaving a key area of need unmet. Neither Keen nor Tonge et al. include psychotherapeutic support for the parent as a core component of their intervention programs. As reported by a mother who provided qualitative feedback as part of the present study, ‘Why is it always about my child? I don’t always want to talk about my child. Health professionals seem to forget that I exist independent of my child.’

Based on the assumption that parental cognitions and socio-economic support mediated the relationship between ‘child-centric’ variables (i.e. autism symptom severity and externalizing behaviours) and parental psychological distress, the following model (Fig. 3) was proposed as being a good fit with the observed data.

The proposed model, as shown in Fig. 3, consisted of 5 latent factors, parental distress, socio-economic support, parental cognitions, externalizing behaviours and autism symptom severity. Parental distress was associated with three indicators, stress, anxiety and depression; socio-economic support was associated with two indicators, social support and economic support; parental cognitions was associated with two indicators, perceived limit setting ability and parental locus of control; externalizing behaviours was associated with two indicators, aggressive behaviour and conduct problems; and autism symptom severity was associated with two indicators, social interaction and communication skills.

Parental distress was predicted by socio-economic support and parental cognitions; parental cognitions was predicted by socio-economic support and externalizing behaviours; socio-economic support and externalizing behaviours were both predicted by autism Symptom severity. There was no correlation between error terms and no cross-loading of indicators.

The model described in Fig. 3 assumes no direct relationship between parental distress and either autism symptom severity or externalizing behaviours, based on assumptions already outlined in this discussion. The model assumes that autism symptom severity is predictive of both externalizing behaviours and lower scores on measures of socio-economic support, based on existing studies focused on the relationship between these variables (Gray and Holden 1992; Macintosh and Dissanayake 2006; Lamminen 2008). Lastly, based on the results of the regression analyses conducted as part of this study, the model assumes that externalizing behaviours and socio-economic support are predictive of negative parental cognitions, and that it is these negative parental cognitions, along with perceived socio-economic support, that predict parental distress.

The relationship between autism symptom severity and externalizing behaviours is already documented in the existing literature. In a chronological and mental age-matched study of 20 children with high-functioning autism, 19 children with Asperger’s Syndrome and 17 developmentally normal children, Macintosh and Dissanayake (2006) demonstrated that children with autism (and Asperger’s Syndrome) exhibited more problematic externalizing behaviours than children in the developmentally normal group. It has also been demonstrated in the literature that parents of children with autism report lower scores on scales of socio-economic support than parents of developmentally normal children (Gray and Holden 1992; Lamminen 2008). What the model in Fig. 3 proposes is that the relationship between these variables and parental distress is mediated, partially in the case of socio-economic support, and fully, in the case of externalizing behaviours, by parental cognitions. Should this model be shown to be a good fit with the observed data (for mother, fathers or both), it would suggest a new approach is needed to support this parental group—a focus on psychotherapeutic support for the adult rather than solely parental training related to the child.

Although multiple regression studies provide a good insight into the factors predicting mental health problems in this parental group, regression analysis cannot provide an insight into the relationship between independent variables. Structural equation modelling was thus used to test the validity of the proposed model. An additional aim of the analysis, if the model was shown to be a good fit for both mothers and fathers, was to test for invariance between the two groups. If it can be shown that the model has, at minimum, structural invariance across gender, it can arguably be hypothesised that the model forms a useful basis for informing support services targeting this specific parental group.

SEM Analysis—Method

Participants for this study were the same as those used for the stepwise regression analyses (N = 250 for mothers and N = 229 for fathers). MPlus’s (Version 6.1, Muthén and Muthén 2010) maximum likelihood estimation extraction procedure was used to evaluate Model A for mothers and fathers.

Overall model fit was determined with the Chi square statistic (χ2), the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler 1990), and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; MacCallum et al. 1996). As this study incorporated a large sample size it was likely that the χ2 score for model fit would be significant (indicating poor model fit). χ2 values are almost always significant with large samples sizes (Brown 2006). It was postulated, therefore, that the CFI and RMSEA scores would provide better assessments of model fit. CFI and RMSEA scores range from 0.00 to 1.00. A CFI value of close to or above 0.95 (with a minimum acceptable value of 0.90) and an RMSEA value of close to or below 0.06 (with a maximum acceptable value of 0.08) are considered necessary to conclude that there is a relatively good fit between the hypothesized model and the observed data (Hu and Bentler 1999).

Invariance and partial invariance testing between models for mothers and fathers was evaluated using MPlus’s (Version 6.1, Muthén and Muthén 2010) robust maximum likelihood estimation extraction procedure. Comparative fit between models was determined using the Satorra–Bentler Chi square difference test (∆SBχ2; Satorra and Bentler 2001). The Satorra–Bentler Chi square difference test was undertaken using the ‘sbdiff’ software program (Crawford 2007).

SEM Analysis—Results

Model Fit Statistics

The model fit statistics for the five factor path model of parental distress (Model A) are shown in Table 10.

For mothers, the CFI estimate was 0.974, and the RMSEA estimate was 0.052. These results would indicate that Model A is a good fit with the observed data for mothers.

For fathers, the CFI estimate was 0.954, and the RMSEA estimate was 0.072. These results would indicate that Model A is also a good fit with the observed data for fathers.

Measurement and Structural Invariance Across Gender

The results of measurement and structural invariance tests for Model A across gender are shown in Table 11.

CFI and RMSEA values for the configural (form) invariance and metric (weak) invariance models indicated good fit with the observed data. However, the CFI and RMSEA estimates for the scalar (strong) invariance model indicated poor fit with the observed data.

The Satorra–Bentler Chi squared difference test score for the metric invariance model was non-significant (p > .05), providing support for measurement invariance for Model A across gender at the weak invariance level. However, the Satorra–Bentler Chi squared difference test score for the scalar invariance model was significant (p < .001), indicating that Model A does not demonstrate measurement invariance across gender at the strong invariance level.

Discussion

Structuring a definitive model to describe parental depression, stress and anxiety for any parental group would be an impossible task. The number of environmental, genetic, personal and existential variables that predict, protect against, maintain and counteract mental health problems varies at the personal level. Every person is an individual, and as such every person’s experience of parenthood will be different. However, if support services are to be of help to parents, they must be reflective of that parent’s first-hand experience, not society’s perception of that experience.

The need for tailored support services is especially true for parents of children with autism. Although the existing literature has demonstrated that these parents experience more mental health problems than other parental groups (Benjak 2009; Bitsika and Sharpley 2004; Micali et al. 2004), the interventions designed to support this parental group generally assume these mental health problems primarily relate to the practical challenges of parenting a child with autism (Keen et al. 2010; Tonge et al. 2006). However, although behavioural management training programs such as those described by Keen et al. (2010) and Tonge et al. (2006) have been demonstrated to be effective in the short-term, providing longer term support to parents of children with autism requires a more holistic approach.

Although a number of studies exist that focus on the predictors of mental health problems in the parents of children with autism (Bitsika and Sharpley 2004; Civick 2008; Farrugia 2009; Fiske 2009; Hastings and Johnson 2001; Lecavalier et al. 2005), the majority of these studies focus on a small subset of predictive variables and a single dependent variable (usually stress, anxiety or depression). Although certainly valuable research, what these studies do not provide is a holistic view of the experience of parenting a child with autism, and the overall dynamics between variables that are predictive of, or protective against, mental health problems. Although social support (Gray and Holden 1992; Lamminen 2008), child externalizing behaviours (Gray 2003; Lecavalier et al. 2005), and autism symptom severity (Hastings and Johnson 2001; Duarte et al. 2005) have been shown to significantly predict stress, anxiety or depression in the parents of children with autism when assessed independently, that does not mean that these variables will demonstrate a linear predictive relationship in the presence of other possible predictors.

If research is to provide a starting point for the development of parental support services, then this lack of a holistic view is a problem. Parents who present to services are not uniform in their presentation—some may present with stress, some with depression and some with a complex combination of symptoms spanning two or more possible diagnostic categories. Additionally, parents will be affected by a diverse and changeable set of potentially contributory factors. Although, in this parental group, having a child with autism is an obvious common denominator, the contribution of other environmental, personal and situational factors will be multifaceted and specific to the individual. Therefore this study, in aiming to provide a groundwork for structuring relevant support services, takes a more inclusive approach. It looks at all three of the primary mental health variables parents tend to present with—stress, anxiety and depression—and includes a wide range of potential predictors in the analysis. The included subset of predictors still remains limited. It would be difficult for any study to include all the variables that could potentially contribute to parental mental health problems. However, by being as inclusive as possible (and by ensuring the selection of predictors is based on empirical findings), this study aimed to provide an assessment of not only the key predictors of mental health problems in the parents of children with autism, but also the relationship between those predictors.

The results of the stepwise regression analysis for mothers indicated potentially important differences in the predictors for anxiety and depression. Whereas anxiety was predicted by maternal age, the mother’s perceived ability to set behavioural limits for their child and autism symptom severity, depression was predicted by the child’s aggression towards adults, a perceived lack of social support and an externalized parental locus of control. The observed result has arguably significant implications for parental support services. When a mother of a child with autism presents with depression, the underlying contributors to the problem will not necessarily be the same as a mother of a child with autism presenting with anxiety. However, although the pattern of predictors between depression and anxiety is clearly different, there is still, arguably, a core theme central to both, and that is ‘perception of control.’ Although parental locus of control and perceived limit setting ability are measuring different phenomena—the former describing a perception of parental influence over their child’s emotional and behavioural development and the latter specific to a perceived ability to set limits on maladaptive behaviour patterns—they are still measures of parental perception of control. And in both situations, where the parent perceives they do not have a direct (or sufficient) influence over their child, it is predictive of elevated mental health measures.

What is key here is the word ‘perception.’ Neither variable is measuring whether the parent actually has an appropriate level of influence or behavioural control over their child(ren). The variables are measuring the parent’s perception of that control. Some of the comments left on the study Facebook page provide some insight into this difference. One mother commented that ‘I get very depressed. My three sons are on the spectrum. My youngest doesn’t speak much and has Hypotonia and he seems so unhappy. And I feel so guilty because I should be able to help him. I feel like such a bad mother.’ Another mother commented ‘don’t you just hate it when your child has a tantrum in a supermarket and everyone looks, and then we shout and say ‘what, he has autism’ and then they smile and walk off. They don’t even bother to ask you what is autism, and its pointless anyway because there’s nothing you can do.’

Parents of children with autism face challenges not commonly experienced by other parents. As noted in the introduction to this study, children with autism can be difficult to understand, due to their atypical personal responsiveness (Busch 2009) and demonstrate more maladaptive externalizing behaviours than developmentally normal children (Macintosh and Dissanayake 2006). Thus the results of effective, consistent parenting in a child with autism may be difficult to assess. Parents who are in fact managing to set limits and assist their child’s emotional development may not receive clear reinforcement, in terms of ‘positive’ changes in their child’s behaviour or demeanour. Thus they may start to perceive themselves as being ineffective parents. Providing these parents with additional means of managing behaviour (i.e. behavioural management plans) may not make a significant difference. If the parent already perceives themselves as ineffectual, new behavioural management plans, even if effectively practiced, may not change this perception. And, as noted by Schieve et al. (2007), parents who perceive themselves as ineffectual (and suffer from associated depression and anxiety) may lack the motivation to comply with behavioural management recommendations in the first place.

There are two primary conclusions, therefore, that can arguably be drawn from the analysis of the stepwise regression model for mothers. The first is that mothers with different mental health presentations are potentially being affected by a different pattern of contributory factors. Thus applying a ‘one size fits all’ intervention focused on behavioural management for the child may not be effective. The second conclusion is that the child’s autism symptomology and externalizing behaviours, although related to maternal mental health problems, are not the core predictors of maternal psychological distress. The core predictor, and the main focus of any successful intervention, is maternal cognitions. A limitation of this study is that it only measured cognitions related to parenting. It may be that cognitions unrelated to parenting (e.g. general locus of control and not just parental locus of control) would be just as significant in predicting mental health measures in this maternal group. However, until this research is undertaken, cognitions related to parenting, and more specifically to perceptions of control, should be a central focus for interventions looking to reduce maternal stress, anxiety and depression. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, as an example, has been demonstrated to be effective in helping parents of children with autism cope with negative cognitions (Blackledge and Hayes 2006). Providing parenting skills training without challenging the underlying belief systems related to the ability to implement those skills may, in the long run, be less effective than a more holistic and parent-centric approach.

The results of the stepwise regression analysis for fathers contrasted with the results for mothers. Whereas for mothers the predictors of stress, anxiety and depression differed, the same two variables were indicated as being the primary predictors of stress, anxiety and depression in fathers. These two variables were Social Support and perceived limit setting ability. The observed difference between the genders has potentially important implications for the delivery of support services to this parental group.

In general, the existing body of research has shown that stressful life events cause more psychological distress in women than they do in men, especially when these events affect family and friends (Aneshensel 1992; Thoits 1991). In situations where a child is affected by illness or a disability, mothers are also more likely to blame themselves for their child’s problems and feel that their identities are threatened by their child’s condition (Anderson and Elfert 1989). Existing research has also demonstrated that mothers of children with autism exhibit more mental health problems than fathers (Gray and Holden 1992; Hastings et al. 2005; Sharpley et al. 1997), However, there is only a small body of existing research investigating the difference in predictors across gender. Davis and Carter (2008) and Fiske (2009) reported that paternal stress is more affected by the long-term impact of their child’s diagnosis, whereas maternal stress primarily relates to specific daily stressors. Altiere and von Kluge (2009) found that fathers perceived a greater level of social isolation (lack of social support) than mothers, even within matched pairs. The results of the present study would appear to support Altiere and von Kluge’s finding. Social support was a significant predictor in all three regression models for fathers, but only two for mothers. This mirrors comparable research in the parents of children with cancer. Frank et al. (2001), in a study of 125 parents (77 mothers and 48 fathers) of children with various types of cancer, found that perceived social support associated with affective responses (self-reported depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms) in fathers but not in mothers.

However, a limitation of regression analysis is that it does not provide an insight into the relationship between the predictors. Is there any relationship between a lack of social support and having a child with autism (i.e. does having a child with autism cause parents to become more socially isolated?) A comment left by a father on the Facebook page for this study provided some insight into this—‘The biggest cause of stress, anxiety and depression for me is the lack of access to services for my two boys with Autism (11yrs & 13yrs), and the financial hardship associated with trying to meet their needs. We have also lost all family support along the way, which has been devastating.’

In modelling the relationship between the predictors included in this study and parental distress, as part of the SEM analysis, an assumption was made that this predictive relationship does exist—i.e. having a child with autism is predictive of perceived lower levels of social support, which in turn is predictive of parental psychological distress. However, further research would be warranted here, to both confirm if social support available to parents does reduce post-diagnosis of a child with autism, and whether this reduction in social support, if ‘real’ rather than perceived, is resultant from the child’s behaviour, the parents’ behaviour or the reaction of family and friends to the diagnosis.

The other primary predictor of stress, anxiety and depression in fathers was perceived limit setting ability. Again, this mirrors the results for mothers (perceived limit setting ability was a significant predictor of anxiety and stress, but not depression, in mothers), and highlights the role parental cognitions may play in mediating the relationship between child factors (autism severity and externalizing behaviours) and parental mental health problems.

The other three variables shown to be significant predictors of paternal mental health measures were Satisfaction with Parenting (a significant predictor of depression), Father’s Age (a significant predictor of stress) and Aggressive Behaviour (a significant predictor of anxiety).

A study conducted by Gray (2003) identified that parents of children with autism who displayed aggressive behaviour were more likely to report parental stress than parents of children with autism who did not display aggressive behaviour. However, this does not mean that aggressive behaviour towards adults, a behaviour-type that is widely reported by parents of children with autism (Woodgate et al. 2008), is a more significant predictor of parental mental health problems than other child externalizing behaviours. Both variables were included in this study and, whereas Aggressive Behaviour was a significant predictor of depression in mothers and anxiety in fathers, Conduct Problems was not shown to be a significant predictor in any of the regression models. Again, this does not mean Conduct Problems do not play a role in predicting parental mental health problems. However, it may be that the variance in mental health variables being contributed by Conduct Problems is explained by autism-specific maladaptive behaviours, such as aggressive behaviour towards adults. It should by noted, however, that the measure used to assess aggressive behaviour in this study consisted of a single item, and thus is subject to misinterpretation when included in statistical analysis. Further research aiming to define the externalizing behaviours that predict parental psychological distress in this specific cohort would be warranted.

Satisfaction with Parenting, as noted earlier, was a significant negative predictor of depression in fathers. As reported by Myers (2009), parents of children with autism report a feeling of loss and grief regarding their own future life opportunities. Myers described parents feeling that they had lost the ability to live their own lives. In the words of one father who commented on the Facebook site for this study, ‘I always wanted to be a parent. But I’m not a parent, I’m just a carer and I don’t have much of a relationship with my son. I do get depressed sometimes.’ The decision to have children is, arguably, based partially on the expectation that it will be a rewarding personal experience. As reported by Busch (2009), parents of children with autism describe their children as ‘impossible to reach’. Busch described that parents of children with autism feel unable to form productive two-way relationships with their children. The perceived parent–child relationship, as hypothesised in the aims of this study, does therefore play in role in predicting parental mental health measures, for fathers at least. Helping parents adapt their pre-existing expectations of parenthood (through a process of cognitive restructuring, such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy), and providing reassurance that it is acceptable for parents to feel a sense of loss and grief, may assist in helping parents adapt to the demands of parenting a child with autism.

Parental age was found to be a significant predictor of stress for both mothers and fathers (and anxiety, for mothers). For both mothers and fathers, age was a negative predictor of stress—i.e. the younger the parent, the more likely the parent was to report high levels of stress. There are many possible explanations for this—younger parents may be less emotionally able to cope with parenting a child with autism, may be less secure in their relationship with their partner, or less financially secure. Beyond such speculation, however, this study provides no insights into why younger parents of children with autism are at greater risk of mental health problems. Further research into this area, investigating the personal, economic and psychosocial factors that affect younger parents of children with autism, would be warranted.

Although the regression analyses undertaken provided a level of insight into the differing predictors of stress, anxiety and depression in the parents of children with autism, what these studies did not take into account is the relationship between the various predictive variables. This study therefore sought to propose a theoretical model describing the relationship between parental psychological distress and the included predictive variables, and test the statistical fit of the proposed model with the observed data for both mothers and fathers.

Based on the results of the regression analyses, it was hypothesised that autism symptom severity and child externalizing behaviours did not directly influence parental psychological distress, and that the relationship between these two sets of variables was mediated by parental cognitions and socio-economic support. The model fit statistics for both mothers and fathers indicated that this model was a good fit with the observed data. Although invariance testing between the model for mothers and fathers only indicated weak (metric) invariance, the results provide support for the development of support services that focus on parental cognitions as well as behavioural management training—i.e. a therapeutic approach rather than solely an autism and child-centric approach.

Certain limitations need to be taken into account before any clear conclusions can be drawn from the study results. Firstly, as with any study looking at the factors predicting stress, anxiety and depression, this study included a restricted subset of potentially predictive variables. Perceived stigmatization and physical well-being were not taken into account, and cognitions unrelated to parenting were also not assessed. The current study provides only a surface level insight into the actual types of cognitions that predict and maintain stress, anxiety and depression in the parents of children with autism. Secondly, the age range used in this study was relatively large (the study included parents of children with autism aged 4–17). Use of such a large age range benefited recruitment to the study. However, it is possible that such a wide age range may have impacted on the outcome of the subsequent analyses. This needs to be taken into account when interpreting the data. Thirdly, this study recruited mothers and fathers separately from the general population. It did not recruit matched pairs of mothers and fathers. Any differences observed in predictive variables between mothers and fathers is therefore subject to variance within the study populations. 99 % of participating mothers and 43 % of participating fathers in this study reported being primary carers for their child(ren) with autism. As 74 % of mothers and 87 % of fathers reported being married or in a relationship, it is unlikely the study population is reflective of those parents less actively involved with their child(ren) with autism. Recruiting matched pairs of mothers and fathers would provide a more comprehensive source of comparison across gender. A suggestion for further research would be to test the theoretical model proposed in this study using a matched pair study design. Another limitation was the use of author-generated measures of socio-economic support and development age and a single item measure of aggressive behaviour. The decision was made to include abbreviated measures of these variables to limit the length of the questionnaire (due to concerns over participant completion rates and the cohort size required to undertake regression analysis). However, there would have been clear advantages in using validated, widely researched measures to assess these variables.

However, with these limitations in mind, this study does indicate that child-related factors such as autism symptom severity and externalizing behaviours may not be the primary predictors of mental health problems in the parents of children with autism. Socio-economic support and parental cognitions, specifically those cognitions related to the role of the parent, are indicated as being the primary predictors of mental health problems, and these factors may mediate the relationship between child-related factors and parental psychological distress. A possible area for further research would be to test a theoretical framework to explain these observed relationships in more detail.

Based on these results, it can be theorized that support services focused solely on autism psychoeducation and behavioural management training, as proposed by Tonge et al. (2006) and Keen et al. (2010), may have a short-term efficacy. Combining elements of these programs with psychological therapy and respite care for the child would, theoretically, provide more long term benefit in reducing parental mental health problems and encouraging adherence to behavioural management plans (as long, of course, as the parents are willing and able to comply with the offered therapy). Without an understanding of the psychological impact of parenting a child with autism, and without providing parents with the skills to cope with associated beliefs and cognitions, interventions are unlikely to be effective. In providing support to parents of children with autism, the focus must not only be on the child.

References

Altiere, M., & von Kluge, S. (2009). Family functioning and coping behaviors in parents of children with autism. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18, 83–92.

Anderson, J. M., & Elfert, H. (1989). Managing chronic illness in the family—Women as caretakers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 14, 735–743.

Aneshensel, C. S. (1992). Social stress: Theory and research. Annual Review of Sociology, 18, 15–38.

Argyrous, G. (2000). Statistics for social and health research. London: Sage.

Benjak, T. (2009). Comparative study on self-perceived health of parents of children with autism spectrum disorders and parents of non-disabled children in Croatia. Croatian Medical Journal, 50, 403–409.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246.

Bitsika, V., & Sharpley, C. (2004). Stress, anxiety and depression among parents of children with ASD spectrum disorder. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counseling, 14, 151–161.

Blackledge, J. T., & Hayes, S. C. (2006). Using acceptance and commitment therapy training in the support of parents of children diagnosed with autism. Child & Family Behaviour Therapy, 28, 1–18.

Bowerman, B., & O’Connell, R. (1990). Linear statistical models: An applied approach. Boston: PWS-Kent Pub. Co.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guildford Press.

Busch, E. C. (2009). Using acceptance and commitment therapy with parents of children with autism: The application of a theory. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses 0622 (0971). Uni Dissertation Publishing.

Campis, L. K., Lyman, R. D., & Prentice-Dunn, S. (1986). The parental locus of control scale: Development and validation. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 15, 260–267.

Civick, P. (2008). Maternal and paternal differences in parental stress levels and marital satisfaction levels in parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses 0622 (0925). Umi Dissertation Publishing.

Crawford, J. R. (2007). sbdiff.exe [Computer software].

Davis, N. O., & Carter, A. S. (2008). Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 278–1291.

Duarte, C. S., Bordin, I. A., Yazigi, L., & Mooney, J. (2005). Factors associated with stress in mothers of children with autism. Autism, 9, 416–427.

Farrugia, D. (2009). Exploring stigma: Medical knowledge and the stigmatisation of parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Sociology of Health & Illness, 31, 1011–1027.

Field, A., Miles, J., & Field, Z. (2012). Discovering statistics using R. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Fiske, K. (2009). A cross-sectional study of patterns of renewed stress among parents of children with autism. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses 0621 (0190).

Frank, N. C., Brown, R. T., Blount, R. L., & Bunke, V. (2001). Predictors of affective responses of mothers and fathers of children with cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 10, 293–304.

Gerard, A. B. (1994). Parent–child relationship inventory (PCRI) manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 1337–1345.

Gray, D. E. (2003). Gender and coping: The parents of children with high functioning autism. Social Science and Medicine, 56, 631–642.

Gray, D. E., & Holden, W. J. (1992). Psycho-social well-being among the parents of children with autism. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 18, 83–93.

Hartley, S. L., Barker, E. T., Seltzer, M. M., Floyd, F., Greenberg, J., Orsmond, G., et al. (2010). The relative risk and timing of divorce in families of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 449–457.

Hassall, R., Rose, J., & McDonald, J. (2005). Parenting stress in mothers of children with an intellectual disability: The effects of parental cognitions in relation to child characteristics and family support. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49, 405–418.

Hastings, R. P., & Johnson, E. (2001). Stress in UK families conducting intensive home-based behavioral intervention for their young child with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 327–336.

Hastings, R. P., Kovshoff, H., Ward, N. J., Degli Espinosa, F., Brown, T., & Remington, B. (2005). Systems analysis of stress and positive perceptions in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35, 635–644.

Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 227–239.

Hoppes, K., & Harris, S. (1990). Perceptions of child attachment and maternal gratification in mothers of children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 19, 365–370.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Keen, D., et al. (2010). The effects of a parent-focused intervention for children with a recent diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder on parenting stress and competence. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4, 229–241.

Kuusikko-Gauffun, S., Pollock-Wurman, R., Mattila, M.-L., Jussila, K., Ebeling, H., Pauls, D., et al. (2013). Social anxiety in parents of high-functioning children with autism and Asperger Syndrome. Journal of Autism and Development Disorders, 43, 521–529.

Lamminen, L. (2008). Family functioning and social support in parents of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, 0519(0102).

Lecavalier, L., Leone, S., & Wiltz, J. (2005). The impact of behaviour problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 3, 172–183.

Lee, G. K. (2009). Health-related quality of life of parents of children with high-functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24, 227–239.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (1994). Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder, 25, 659–685.

Lovibond, S., & Lovibond, P. (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (2nd ed.). Sydney: Psychology Foundation.

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1, 130–149.

Macintosh, K., & Dissanayake, C. (2006). Social skills and problem behaviours in school-aged children with high-functioning autism and Asperger’s disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 1065–1076.

Menard, S. (2002). Applied logistic regression analysis (2nd ed.). California: Sage Publications.

Micali, N., Chakrabarti, S., & Fombonne, E. (2004). The broad autism phenotype: Findings from an epidemiological survey. Autism, 8, 21–37.

Moore, T. R. (2009). Adherence to behavioral and medical treatment recommendations by parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 1173–1184.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2010). Mplus user’s guide (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén.

Myers, B. J. (2009). “My Greatest Joy and My Greatest Heart Ache:” Parents’ own words on how having a child in the autism spectrum has affected their lives and their families’ lives. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3, 670–684.

Rogers, M. L. (2008). Can marital satisfaction of parents raising children with autism be predicted by child and parental stress. ProQuest Dissertation and Theses, 0451 (1389).

Rutter, M., Bailey, A., & Lord, C. (2003). SCQ: Social Communication Questionnaire. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2001). A scaled difference Chi square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika, 66, 507–514.

Schieve, L. A., Blumberg, S. J., Rice, C., Visser, S. N., & Boyle, C. (2007). The relationship between autism and parenting stress. Pediatrics, 119, 114–121.

Sharpley, C. F., Bitsika, V., & Efremidis, B. (1997). Influence of gender, parental health, and perceived expertise of assistance upon stress, anxiety, and depression among parents of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 22, 19–28.

Singer, G. (2006). Meta-analysis of comparative studies of depression in mothers of children with and without developmental disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 111, 155–169.

Tabachnik, B. G., & Fidell, S. L. (2012). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). New York: Harper Collins.

Thoits, P. A. (1991). Gender differences in coping emotional distress. In J. Eckenrode (Ed.), The social context of coping (pp. 107–138). New York: Plenum Press.

Tomanik, S., Harris, G. E., & Hawkins, J. (2004). The relationship between behaviours exhibited by children with autism and maternal stress. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 29, 16–26.

Tonge, B., Brereton, A., Kiomall, M., Mackinnon, A., King, N., & Rinehart, N. (2006). Effects on parental mental health of an education and skills training program for parents of young children with autism: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45, 561–569.

Woodgate, R. L., Ateah, C., & Secco, L. (2008). Living in a world of our own: The experience of parents who have a child with autism. Qualitative Health Research, 18, 1075–1083.

Wright, B., & Williams, C. (2007). Intervention and support for parents and carers of children and young people on the autism spectrum: A resource for trainers child. London: Kingsley Publishers.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the University of Tasmania in completing this study. The authors also wish to acknowledge the time taken and vital contribution made by the study participants.

Ethical standard

The research associated with this article abides by the ethical standards laid down by the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Ethics approval was granted prior to commencement of the study.

Informed consent

All participants gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Falk, N.H., Norris, K. & Quinn, M.G. The Factors Predicting Stress, Anxiety and Depression in the Parents of Children with Autism. J Autism Dev Disord 44, 3185–3203 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2189-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2189-4