Abstract

We describe a survey of children with ASD aged 4–10 years. The main dependent variables were out-of-pocket expenditures for health services and hours of therapy. Multivariable logistic regression models were used in order to find independent predictors for service utilization. Parents of 178 of the children (87 %) agreed to participate. The average annual out-of-pocket cost was $8,288, with a median of $4,473 and a range of $0-89,754. Higher severity of ASD and a parent with an academic degree were associated with higher expenditure. Having at least one older sibling, siblings without developmental disorders, regular education setting, lower parent education and low income were associated with lower expenditure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) are diagnosed in early childhood and considered to be lifelong disabilities. Current clinical guidelines for the treatment and management of children with ASD are available from the Council of Children with Disabilities (Myers and Johnson 2007). Best practice is considered an individualized and integrated program including educational, medical and allied-medical interventions, provided by professionals and directed to minimize specific developmental deficits and reduce negative behaviors (Myers and Johnson 2007).

In recent years, several major advancements have influenced the interaction between children with ASD and health systems: children with ASD are diagnosed younger and at higher rates, their clinical management is becoming more intensive, proactive, comprehensive, and consequently-more expensive (Croen et al. 2006; Leslie and Martin 2007; Mandell et al. 2006; Shimabukuro et al. 2008). The complexity of this disability and the rapid advances present an enormous challenge for healthcare systems, in terms of adequate clinical management and cost containment.

Medical expenditures of a child with ASD in the United States, based mainly on reimbursement payments, were found to be 3–10 times greater than those for children without ASD (Croen et al. 2006; Mandell et al. 2006; Shimabukuro et al. 2008). The medical expenditure per one child with ASD has increased by 20 % during 2000–2004 (Leslie and Martin 2007).These expenditure estimations usually do not include out-of-pocket expenses, special education and educational interventions costs, complementary and alternative medicine, loss of family income and other expenses. According to a British pilot study, these expenses probably represent a major part of the total expenditures associated with ASD (Jarbrink et al. 2003).

The Israeli health system bases most of its services on public organizations. The national health insurance act in Israel defines the eligibility of children with specific developmental disabilities (and ASD among them), for extended health services. Funding of up to three individualized treatments per week is given up to age 18 years, for all children diagnosed with ASD. Additional treatments may be funded by the Ministries of Health, Education or Labor, according to the child’s age and educational setting. In addition, access to pediatrician or nurse is not restricted, most medications are funded with copayment of no more than 15 %, and special education (including some specific ASD treatments) is covered.

From age 6 months and up to 3 years (plus 11 months if during same educational year), children with ASD in Israel are eligible to early preschool special education, including at least 10 h of individualized treatments per week and funded in full by the Ministry of Labor and Social services. After age three, they are eligible to special education in preschool, kindergarten or school setting, funded by the Ministry of Education. However, if parents or educators apt for integration in regular settings, the eligibility for treatments is more limited. Home-based programs and many educational interventions are not reimbursed.

In Israel, core ASD treatments include: physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy and psychological treatments. Most specific treatments for autism such as ABA (Applied Behavioral Analysis) and DIR (Developmental, Individual difference, Relationship-based model), are designated as educational interventions (unless provided by one of the core professions mentioned above). As such, the latter are fully paid out-of-pocket.

Gaps in public service availability and eligibility along with medical recommendations for an intensive and emergent approach may encourage utilization of private health services, with significant economic and social implications. The current study is aimed to provide information regarding the utilization of health services by children with ASD in Israel, and the level of out-of-pocket expenditures which is associated with these services.

Methods

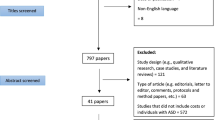

This is a survey of health services utilization by children with ASD in Israel. The survey included children aged 4–10 years, with a definitive diagnosis of ASD. The children were identified from the clinical records of the “Keshet” Center for autism, which belongs to the Israeli Ministry of Health and receives referrals countrywide. First, we sent letters to the parents of all eligible children from the center, explaining the study and its aims. Few weeks later, one of the researchers administered a semi-structured telephone interview to the parents who gave their consent. We conducted the interviews during February 2010–June 2011. The study was approved by the Sheba Medical Center Institutional Review Board (approval # SMC-7177-09).

We have developed the retrospective interview for this study, and it included questions about the utilization of health services for the child during the last school year. For each service, we have documented the service type, frequency of use, service provider and the associated out-of-pocket expenditure. We did not consider education hours as relevant services or treatments for the purpose of this survey, except for focused therapy hours, such as educational ASD interventions or therapies given at educational settings. In cases of recall problems, we encouraged the parent to check the documentation or consult with the other parent for missing details. Expenditures data were converted into monetary terms at 2011 real market prices using conversion rate of 1 USD = 3.74 New Israeli Shekels. ASD diagnosis subtype was taken from the medical records, and was categorized according to DSM-4 diagnoses into low severity (PDD-NOS, Asperger’s disorder) and high severity (Autistic disorder, Rett syndrome).

Missing expenditures data (6.7 % of the treatment items) were imputed by replacement of the expenditures unit with the average unit cost for the same specific treatment in our sample. Missing data regarding hours of therapy (1.5 % of the therapies) were imputed using the mean weekly hours for the same specific therapy.

We have divided the yearly out-of-pocket expenditures into quartiles, and calculated two separate multivariable logistic regression models—one for the upper quartile, and the other for the lower quartile of expenditures. Independent variables were entered into the models using the forward stepwise method (by likelihood ratio). Significance levels of 0.2 for addition to the model and 0.25 for removal from the model were used, in order to enable statistical adjustment for relevant variables, while keeping a stable model. We analyzed hours of therapy by the same statistical methods. Associations between predictors and independent variables are reported by odds ratios (OR) and their 95 % confidence intervals (CI). All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19 and WINPEPI version 11.8.

Results

Study Population

We have contacted the parents of 204 consecutive 4–10 years old children with a validated diagnosis of ASD (our recruitment base), and 178 (87 %) of them gave their consent and completed the interview. The distribution of ASD subtypes and children’s age were not significantly different when comparing participants to non-participants, although participating children were slightly younger on average than non-participants (mean = 6.7 ± SD = 1.9 vs. 7.3 ± 2.0 years, respectively). Most of the children (85 %) were boys, and the mean age at the time of interview was 6.7 years (SD: 1.9), with the leading diagnoses being PDD-NOS (47 %) and autistic disorder (45 %). The study population is further described in Table 1.

Health Service Expenditures Paid for Out-of-Pocket

The average annual out-of-pocket expenditure per child was $8,289 (SD $11,642), with a median of $4,473 and a range of $0–89,754. Table 2 describes treatment utilization and out-of-pocket expenditures by treatment category. Median values for most categories were null. Figure 1 visually presents the average expenditure on the various treatment categories.

Endorsed allied-medical treatments (including mostly speech therapy, occupational therapy, but also physiotherapy, psychological treatment and social work) were used by almost all of the children. Allied-medical treatments in general (including also pending endorsement therapies, such as hydrotherapy, hippotherapy and art therapy) were summed up to 41 % of the total out-of-pocket expenditure. Educational treatments, such as ABA or DIR, were used approximately by 15 % of the children, but still formed the most expensive category. Personal aides were used in the educational settings or at home by 42 % of the children. Complementary/alternative treatments, represented under various categories in our division (other allied-medical therapies, food supplements, other alternative treatments), also bare substantial portion of the out-of-pocket expenditure.

Most children (80 %) were utilizing services at their educational settings, but these services had very limited out-of-pocket expenditures (only 3 % of the average annual expenditure). On the other hand, 84 % of the parental expenditure was spent on private providers (average annual expenditure: $6,914 per child). Additional service providers included Health Maintenance Organizations (7 % of the expenditure) and others (6 %), such as hospital clinics (Table S1).

Table 3 presents the associations of various child and family characteristics with the chances for being in the upper quartile (model 1) or the lower quartile (model 2) of out-of-pocket expenditure level, in two separate multivariable models. Higher severity of ASD was associated with more than three fold likelihood for very high expenditure (OR = 3.31; 95 % CI 1.40–7.83), and having at least one of the parents with an academic degree was associated with 6-fold likelihood for very high expenditures, in comparison to families where none of the parents had more than 12 years of education (OR = 5.93; 95 % CI 1.21–29.02). Having a secular parent, living with a spouse or house income above average, were also associated with increased chances for very high expenditure, although not significantly.

The only variable that we found to be associated with the lower quartile of expenditure (Table 3, model 2) was: having at least one older sibling (OR = 4.83; 95 % CI 1.61–14.45 and OR = 4.35; 95 % CI 1.62–11.67 for one or more older siblings, respectively). Variables that were significantly associated with lower likelihood of very low out-of-pocket expenditure are: having a sibling with developmental disability (OR = 0.28, 95 % CI 0.09–0.9), attendance of a regular preschool setting (OR = 0.1, 95 % CI 0.02–0.53 in comparison to special education preschool), higher parental education (OR = 0.26, 95 % CI 0.09–0.77) and house income of around or above average (OR = 0.34, 95 % CI 0.12–0.96, and OR = 0.11, 95 % CI 0.03–0.38, respectively).

Utilization of Health Services by Treatment Hours

We have also calculated the actual weekly hours of treatment (including allied-medical treatments, educational and pedagogic interventions) per child. There was an average of 7.3 weekly hours of treatment (SD: 5.25; median: 6.0; range: 1.0–34.3 h). Being at the upper quartile of treatment hours, was significantly associated with religiosity (OR = 6.92, 95 % CI 1.53–31.18 for ultra-orthodox in comparison to secular parents), high ASD severity (OR = 3.27; 95 % CI 1.35–7.95) and income above average (OR = 4.61, 95 % CI 1.45–14.66 in comparison to below average) (Table 4, model 1).

The only variable that was independently associated with very low number of treatment hours in a multivariable model was attendance of regular preschool setting or integration in a regular school (OR = 2.82, 95 % CI 1.05–7.54 and OR = 18.18, 95 % CI 4.37–75.72 respectively, in comparison to special education preschool) (Table 4, model 2). Additional variables that entered the model, although without statistical significance, were birth order and parental immigration. Not being a firstborn was found to be a risk factor for less treatment hours. Having a parent who immigrated to Israel, on the other hand, was found to be associated with decreased chances for less treatment hours.

In order to exclude possible confounding by ASD severity, we created another multivariable model which included this variable (using the “enter” method). The model, however, did not change the association for attendance of regular school significantly (OR = 16.0, 95 % CI 3.77–67.64, data not shown).

Following the results of the multivariate models, we further explored the distribution of the educational setting type (special/regular education) by two socio-demographic variables: religiosity and income. This inspection revealed that attendance of special education setting is strongly associated with both high religiosity level (p = 0.03) and lower income (p = 0.02), to the level that none of the ultra-orthodox children in our sample were attending a regular school or preschool (Table S2).

Discussion

Major Findings and Their Implications

This is the first study that examined healthcare services and out-of-pocket expenditures of children with ASD in Israel. Our motivation for this study was driven by social and economic aspects, as well as the increasing incidence of ASD and high associated expenditures, for both parents and society.

In regards to out-of-pocket expenditures, despite the national health insurance coverage in Israel, we found a high expenditure level on average, with very large variability. Although children with a clinically more severe condition do have higher chances for very high out-of-pocket expenditures, the strongest independent predictors for this were socio-demographic. While parents, who immigrated to Israel, or single-parents, had lower chances for high expenditure, parents with higher education or higher income level had higher chances. In other words, out-of-pocket treatment expenditures for children with ASD in Israel, in which a national health insurance law exists since 1995, are determined mainly by the socio-demographic characteristics of their parents. This is related to the fact that some of the preferred treatments for these children are not publicly funded, but also, to some extent, to utilization of unproven, expensive treatments.

One of the few studies that did examine the expenditure impact of children with ASD took place in the United Kingdom (Jarbrink et al. 2003). A sample of only 17 children participated, but the expenditures that were measured were more comprehensive than ours, including additional out-of-pocket expenses and economic burdens (damages, transports, special activities, extra expenditures for siblings, loss of working hours due to informal care and others). The mean weekly expenditure reached almost 700 £ (median: 650 £), in 2003, with the largest portions being income losses and education (approximately 30 % each, not including early educational interventions).

According to the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, the average household income in Israel during 2010 was $38,534, and as such, average out-of-pocket expenditure of $8,289 for one child with autism represents a serious economic burden. Children with ASD are eligible for a disability benefit from the National Insurance of Israel, which amount to approximately $7,500 yearly, but one should also remember that the expenditures that we have measured represent only a small fraction of the parental burden associated with raising a child with ASD. Other difficulties excluding expenditure, such as family effort in provision and coordination of services, distress influencing employment capabilities and reduced attention for siblings may also be mentioned in this context, despite the fact that these are harder to measure and quantify.

The public health debate in the United States commonly deals with the issue of the non-insured population. It was recently found, however, that the portion of uninsured children in the US is smaller than the portion of “underinsured” ones: those who own health insurance, but are inadequately covered (Kogan et al. 2010). This phenomenon may be similar to the one uncovered in the current study: most health services for children with ASD in Israel are not adequately covered, and parents are using private services, as far as they can afford in terms of time and money, despite being covered by a national insurance. “Underinsurance”, therefore, might not be unique to countries without a national health insurance, and the results of this study may have implications on every country which is considering policy changes in its health insurance regulations.

In addition, the “medical home” concept, which is frequently used in the American healthcare literature regarding children with special needs (AAP 2004; Kogan et al. 2008; Strickland et al. 2004), is expected to be a natural result of the Israeli healthcare system. Each and every Israeli child is insured by a public HMO, funded by the state. Private expenditures for children with ASD, however, are found in our sample to be used very commonly (67 % of the children), to the level of 84 % of the expenditure. The medical home for many children with ASD in Israel has therefore shifted from their publicly funded HMO to their private providers.

Patterns of Service Utilization

While investigating predictors for very low expenditures, the importance of the educational setting stood out. We found that children with ASD who are integrated into regular education settings, in which fewer therapies are given, will have low chances for low out-of-pocket expenditure, even after adjustment for socio-demographic factors like parental education and income. Due to the large differences in cost of treatments among various providers, with the highest differences between special education settings (usually free of charge) and private settings, we went further to analyze service utilization by hours of treatment, regardless of out-of-pocket expenditures. We found that children who were integrated into regular education, especially regular schools, were not only those who spent more money on treatments, but also those who got minimal treatment hours. In other words, integration into a regular daycare or school, implicates less treatment for the child and higher expenditures for the parents, regardless of disease severity.

Jewish Ultra- orthodox families in Israel usually have very low income and are less likely to apt for home based programs for their children, due to privacy, financial and logistic considerations. This may explain our finding that these children are attending special education (instead of integrating the child in regular settings), which in turn results in receiving more treatment hours.

In summary, children of parents who are ultra-orthodox, have low income or low formal education level, recent immigrants, and children who are not firstborn—tend to attend special education settings, which gives them more hours of treatment while maintaining lower out-of-pocket expenditure. On the other hand—parents with higher education and income level tend to integrate their children into regular settings, and utilize allied-medical and educational treatments from private providers.

These findings may be useful for policymakers and case managers. Integration of children with disabilities saves significant public expenditures, is demanded by many parents and is usually encouraged by the medical personnel. In order to provide better treatment to children with ASD in integrated education, reduce parental economic burden and coordination effort, health policymakers may consider providing reasonable-cost treatments during school hours in regular schools and daycare settings.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, our study is the first to comprehensively examine the out-of-pocket expenditures associated with having a child with ASD. The main strength of the study is its thorough data collection regarding use of health services, including expenditures and hours of treatment, expanded treatment categories, private and public providers. We believe that treatment out-of-pocket cost is part of the clinical setting, and as such, our findings are also relevant for clinicians who treat and manage children with ASD.

Several limitations of the study should be noted. The study was not based on a representative sample of the population of children with ASD in Israel, since we were not able to generate such a sample. We used a list of children who were treated or diagnosed at one large tertiary center, and by no doubt, this sample underrepresents children who live in the geographic periphery of Israel and children whose parents cannot be interviewed appropriately in Hebrew (such as the Arab population and recent immigrants). This last limitation also prevented us from testing and discussing the implications of language and cultural barriers.

We have collected the data retrospectively, and its recall may not be accurate. We have made any effort to minimize recall errors (as described under methods), and recall errors in this study may not be differential with regards to predictors. This implicates that recall errors should not seriously affect the multivariable models, but the descriptive results we have found should still be considered gross estimates.

Future Studies

Future studies are expected to better represent the population of children with ASD in Israel and in other countries, in terms of linguistic, ethnic, geographic and cultural variability. Such representation may certainly raise additional problems and findings that were not detected by us. Studies may also focus on the relations between the type of the educational setting and the factors that are related to the decision on this setting. In addition, prospective data collection is warranted and may certainly improve the accuracy of the data.

References

AAP. (2004). Policy statement: Organizational principles to guide and define the child health care system and/or improve the health of all children. Pediatrics, 113(5 Suppl), 1545–1547.

Croen, L. A., Najjar, D. V., Ray, G. T., Lotspeich, L., & Bernal, P. (2006). A comparison of health care utilization and costs of children with and without autism spectrum disorders in a large group-model health plan. Pediatrics, 118(4), e1203–e1211.

Jarbrink, K., Fombonne, E., & Knapp, M. (2003). Measuring the parental, service and cost impacts of children with autistic spectrum disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(4), 395–402.

Kogan, M. D., Strickland, B. B., Blumberg, S. J., Singh, G. K., Perrin, J. M., & van Dyck, P. C. (2008). A national profile of the health care experiences and family impact of autism spectrum disorder among children in the united states, 2005–2006. Pediatrics, 122(6), e1149–e1158.

Kogan, M. D., Newacheck, P. W., Blumberg, S. J., Ghandour, R. M., Singh, G. K., Strickland, B. B., et al. (2010). Underinsurance among children in the united states. New England Journal of Medicine, 363(9), 841–851.

Leslie, D. L., & Martin, A. (2007). Health care expenditures associated with autism spectrum disorders. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 161(4), 350–355.

Mandell, D. S., Cao, J., Ittenbach, R., & Pinto-Martin, J. (2006). Medicaid expenditures for children with autistic spectrum disorders: 1994–1999. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(4), 475–485.

Myers, S. M., & Johnson, C. P. (2007). Management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 120(5), 1162–1182.

Ruble, L. A., Heflinger, C. A., Renfrew, J. W., & Saunders, R. C. (2005). Access and service use by children with autism spectrum disorders in medicaid managed care. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(1), 3–13.

Shimabukuro, T. T., Grosse, S. D., & Rice, C. (2008). Medical expenditures for children with an autism spectrum disorder in a privately insured population. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(3), 546–552.

Strickland, B., McPherson, M., Weissman, G., van Dyck, P., Huang, Z. J., & Newacheck, P. (2004). Access to the medical home: Results of the national survey of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics, 113(5 Suppl), 1485–1492.

Wang, L., & Leslie, D. L. (2010). Health care expenditures for children with autism spectrum disorders in medicaid. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(11), 1165–1171.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the Israel National Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research (NIHP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raz, R., Lerner-Geva, L., Leon, O. et al. A Survey of Out-of-Pocket Expenditures for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Israel. J Autism Dev Disord 43, 2295–2302 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1782-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1782-2