Abstract

Patterns of current psychotropic medication use among 5,181 children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) enrolled in a Web-based registry were examined. Overall, 35% used at least one psychotropic medication, most commonly stimulants, neuroleptics, and/or antidepressants. Those who were uninsured or exclusively privately insured were less likely to use ≥3 medications than were those insured by Medicaid. Psychiatrists and neurologists prescribed the majority of psychotropic medications. In multivariate analysis, older age, presence of intellectual disability or psychiatric comorbidity, and residing in a poorer county or in the South or Midwest regions of the United States increased the odds of psychotropic medication use. Factors external to clinical presentation likely affect odds of psychotropic medication use among children with ASD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are a collection of neuro-developmental disorders characterized by repetitive behaviors and deficits in social interaction and communication. The ASD include autistic disorder (AD), pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), and Asperger disorder, usually referred to as Asperger syndrome (AS) (American Psychiatric Association 2000). Treatment of ASD often includes psychotropic medications to address aggression, self-injurious behavior, hyperactivity, anxiety, sleep problems, and other symptoms common in children with these disorders (Bryson et al. 2003; Filipek et al. 2000; Myers et al. 2007; Witwer and Lecavalier 2005). Although the US Food and Drug Administration has indicated only one medication for use in ASD treatment (risperidone), many other medications are commonly prescribed (Filipek et al. 2000; Findling 2005; Myers et al. 2007; Posey et al. 2008; Tsai 1999; Volkmar 2001).

Previous studies estimated that 30–60% of children with ASD use at least one psychotropic medication, predominantly antidepressants, stimulants, or neuroleptics (including newer antiepileptic medications) (Aman et al. 2005; Green et al. 2006; Mandell et al. 2008; Martin et al. 1999; Oswald and Sonenklar 2007; Witwer and Lecavalier 2005). Three mailed surveys of families in Ohio and North Carolina, conducted by one research group, found that higher parental educational level was associated with prescription drug use among individuals with ASD; no information on insurance status was included (Aman et al. 2005; Langworthy-Lam et al. 2002).

An international Web-based survey (Green et al. 2006) examining current treatment of children with parent-reported ASD found that those with more severe autistic symptoms or AS were more likely than were children with milder symptoms to use prescription medications, as were older children. This study did not examine the effects of demographic characteristics on medication use.

Using private-insurance claims (Oswald and Sonenklar 2007; Shimabukuro et al. 2008) and data from a nationally representative sample (de Bildt et al. 2006), other research found similar direct relationships among age, ASD severity, and prescription medication use. These studies and others (Aman and Langworthy 2000; Martin et al. 1999; Witwer and Lecavalier 2005) have not examined the roles of demographic factors beyond age, sex, or type of ASD.

Using data from more than 60,000 Medicaid claimants, Mandell et al. (2008) recently published the most detailed examination to date of psychotropic medication use among people younger than 21 years of age with ASD. They found that age, presence of AS (as opposed to AD), presence of a comorbid psychiatric condition, and presence of a higher degree of intellectual disability all were positively correlated with psychotropic medication use.

In addition to reporting on these individual-level demographic factors, this group found that medication use was increased among White children and children living in rural counties with a high percentage of White residents (Mandell et al. 2008).

The generalizability of these findings may be limited, however, because the sample included solely Medicaid-enrolled children, a disproportionately poor and potentially severely affected group, since children may also qualify for Medicaid based on disability, regardless of family income.

Our goals in this analysis are threefold. We first sought to confirm Mandell et al.’s findings regarding factors influencing psychotropic medication use and comparative prevalence in a unique national dataset, the Interactive Autism Network (IAN), which includes children of varying insurance status. This voluntary, open enrollment national online ASD registry continually collects data from families with affected children, and more recently from adults with ASD. Therefore, the IAN is able to elicit longitudinal information about community-level psychotropic medication use from across the United States.

This cost-efficient, convenient method of acquiring data has encouraged parents of more than 10,000 individuals with ASD to complete questionnaires on both probands and family members, providing natural history and demographic data along with autism screen results. Internet-mediated research is becoming an increasingly important tool for investigators (Best and Krueger 2004; Hewson et al. 2003) and already has helped to advance knowledge in Rett syndrome (Bebbington et al. 2008).

Our second aim was to test the hypothesis that insurance status—in addition to the demographic variables previously associated with medication use—affects use of prescription medications in ASD. The literature in this area is contradictory. For example, Chen and Chang (2002) found that compared with publicly or privately insured children, those without any insurance had lower likelihood of prescription medication use; yet, Martin et al.(2002) reported that psychotropic medication use was much higher in Medicaid-enrolled versus privately insured groups. Related studies have not examined or reported the potential role of insurance status in determining psychotropic medication use (Aman et al. 2005; de Bildt et al. 2006; Green et al. 2006; Witwer and Lecavalier 2005).

Our third goal was to investigate prescribing trends by medical specialty for children with ASD, given limited if any research in this area. The management of mental and behavioral health has become a larger part of pediatric primary care, most noticeably with the evaluation and treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder/attention deficit disorder (ADHD/ADD) (Hoagwood et al. 2000). It is likely that the medication management of other psychiatric and developmental conditions also will be shared among different specialists.

Method

Data Source and Sample

The IAN is an Internet-based research database begun in April 2007. More than 28,000 individuals residing in the United States are participating, with more than 10,000 children with an ASD enrolled, along with 20,000 of their immediate family members. All data are voluntarily submitted by families. The database is continuously updated and recruitment is ongoing; IAN is an open resource with de-identified data made available to other research groups. The current analysis was conducted using data entered as of October 20, 2008, for consented participants 18 years of age or younger who had completed the primary history questionnaire and listed their current treatments (N = 5,181). We excluded children with childhood disintegrative disorder (n = 5); Rett syndrome is an exclusion criterion for registering with IAN.

All survey data were entered by parents and maintained in the Internet Mediated Research System©, or IMRS (MDLogix, Baltimore). Electronic consent was elicited from participating families under the auspices of the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board (#NA_00002750).

IAN Questionnaires

The IAN Project data collection consists of multiple topic-specific questionnaires authored by the IAN Research team in collaboration with other researchers. Survey questions are available at http://www.iancommunity.org/cs/ian_research_questions/ian_research_questions. All families complete an initial registration and then are invited to complete several other questionnaires, including a profile on each affected child and a list of treatments that the child currently receives. Families then complete a separate questionnaire for each listed treatment including information on insurance coverage. Once registered, families receive reminders every 2 weeks to complete outstanding questionnaires. These surveys were developed by IAN staff in collaboration with members of the IAN Science Advisory Committee, piloted with families, and revised as needed.

Families report the child’s primary ASD diagnosis and also are requested to complete the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ), a widely used, validated (Berument et al. 1999) autism screening tool consisting of 40 items based on the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (text revision) (American Psychiatric Association 2000) criteria for ASD and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles). A t score of 15 or higher (12 if the child has a sibling with ASD) is highly suggestive of ASD. The SCQ Lifetime version has been offered to all IAN participants, aged 2 to 18 years, since April 2007. Parents also were given screening questions before completing the form to ensure that the child’s mental age was >2 years.

Specific psychotropic medications and other variables included in this study are described in Table 1. Anticonvulsants are used both for seizure control and as mood stabilizers, but we were unable to determine the reason for using a particular medication so these drugs were combined into one category. Although atomoxetine is technically not a stimulant as defined by the National Hospital Association Formulary, we combined this medication with the Stimulant category since the predominant use is for ADHD/ADD symptoms.

Families do not supply overall insurance status in the IAN survey. Therefore, to examine the effects of type of insurance on psychotropic medication use, we examined data from all subjects who reported use of at least one psychotropic medication and who reported payer information about that medication.

Data Analysis

Analysis was conducted using STATA 9.2 (College Station, TX). To estimate bivariate associations between each independent variable and any psychotropic medication use, we used a random-effects logistic regression model (xtlogit) to adjust for clustering at the state level. For insurance status, data were provided by medication rather than at the patient level. When participants with more than one psychotropic medication reported more than one type of payer arrangement, the modal insurance status was used. For the insurance analysis only, we dropped those participants who had a tie for mode (n = 67 medications, n = 32 participants) and those who chose “Don’t Know.” To examine differences among prescribers, chi-square analysis with Fisher exact test was used.

For the final adjusted logistic regression multivariate model, all statistically significant (p < .05) parameters identified using bivariate analysis were included along with previously identified a priori covariates (race, gender, current ASD diagnosis, age), again using random effects to adjust for clustering at the state level for psychotropic medication use as the dependent variable.

Results

A total of 5,181 children in our sample had complete child and treatment information from April 2007 through October 20, 2008. The sample was predominantly 6–11 years of age (49%), was mostly male (83%), and often reported psychiatric comorbidities (39% with ≥1 comorbidity). Of all eligible participants, 94% had positive SCQ screens. Demographics and other general characteristics of the study sample are provided in Table 2.

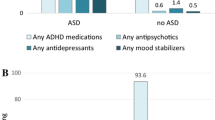

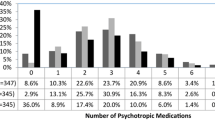

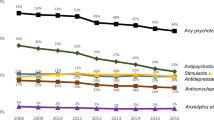

Overall, 35.3% of subjects used at least one psychotropic medication at the time of survey completion (see Table 2). Nearly 10% reported concurrent use of medications in three or more major classes. The most common psychotropic medications were stimulants, neuroleptics, and antidepressants. Less than 2% of participants reported using anxiolytics (n = 75, 1.5%), sedatives (n = 18, 0.2%), or other (naltrexone, n = 16, 0.3%; naloxone, n = 6, 0.1%); therefore, these medications were not included in the tables as distinct categories.

Older children were more likely to use medication than were their younger counterparts, as were those with AS, one or more psychiatric comorbidities, or intellectual disability. White and African American participants reported similar percentages of psychotropic medication use. Hispanic participants were less likely to use any psychotropic medication. Increased maternal educational level was not a significant factor for overall psychotropic medication use but was negatively associated with alpha agonist use.

Among those children using a psychotropic medication with analyzable data (n = 1,575), those with no reported insurance coverage were significantly less likely to be on more than two medications than were those with private insurance, Medicaid, or a combination of insurance types (10.8% vs. 21.3%, 28.7%, or 25.2%, respectively).

Overall, among all medications prescribed (n = 2,624), most were prescribed by a psychiatrist (48.9%) or neurologist (20.3%), and less often by a developmental pediatrician (11.9%) or general pediatrician (10.5%). See supplemental Web Table.

Among those using at least two psychotropic medications (n = 367), 73% had only one type of prescriber; 25% had two types of prescribers and 2% reported three types of prescribers (data not shown). Those with multiple prescribers often had a psychiatrist (79.6%) or neurologist (62.1%) as a co-prescriber.

As shown in Table 3, use of psychotropic medication was associated with geographic characteristics. Compared with participants in less urban areas, those in large metropolitan areas were less likely to be on any psychotropic medication. Psychotropic medication use was least common in the West (27.9%) and Northeast (33.9%), which include a higher proportion of urban populations than the South and Midwest. Those living in counties with the lowest and the highest median incomes were less likely than other participants to report psychotropic medication use (34.8, 33.7% vs. 39.2, 39.8%). In the least affluent counties, participants more often reported using neuroleptics (19.0%) and alpha agonists (11.9%) than did those in other counties. Use of alpha agonists was more common in the South (10.1%). There was a positive correlation between psychotropic medication use and percentage of White county residents.

Table 4 shows that the adjusted odds of psychotropic medication use were predominantly determined by age, type of ASD, presence of intellectual disability or a psychiatric comorbidity, and relative county wealth and geographic region. Participants in the wealthiest counties were 0.70 as likely as those in the poorest counties to report psychotropic medication use (95% CI, 0.52, 0.94, p < .02). Compared with those in the South and Midwest, participants in the Northeast (OR 0.79, 95% CI, 0.63, 0.98) and West (OR 0.60, 95% CI, 0.42, 0.78) were significantly less likely (p < .05) to report any psychotropic medication use.

Discussion

By comparing data from families of more than 5,000 children with ASD, we confirmed and identified important factors affecting likelihood of psychotropic medication use, including individual, demographic, geographic, insurance status, and prescriber.

In our national online registry of children with ASD younger than 18 years of age, we confirmed earlier studies of parent-reported data showing that stimulants, neuroleptics, and antidepressants are the most commonly used psychotropic medications; alpha agonists also account for a sizable proportion of use (Myers et al. 2007). Non-benzodiazepine sedatives and opioid-receptor antagonists were not as popular. Use of all these medications merits further study given their widespread popularity, since many have not been extensively tested on the pediatric population, particularly not as part of a multiple-medication plan.

However, some of our findings about individual factors associated with medication use were different from those in previous reports. We expected that children with AS would be more likely to use psychotropic medications than would other children, based on other reports (Mandell et al. 2008; Martin et al. 1999); but in adjusted analysis, they did not have a higher likelihood than those with other ASD. One possible reason is that we were able to discriminate between AS and PDD-NOS, which was not possible in the Mandell study. More likely, our inclusion of seizure disorder and intellectual disability as independent covariates diminished the difference in psychotropic medication use among different ASD diagnoses. Further research that combines information about genetic and phenotypic differences in ASD is urgently needed for dissecting homogeneous categories in presentation and subsequently maximizing medication effectiveness.

Unlike previous ASD studies, we did not find that a child’s race or ethnicity affected the odds of psychotropic medication use in multivariate analysis (Mandell et al. 2008). One explanation for our finding is that there is selection bias in our self-referred sample that is not present in administrative data. Regardless of ethnicity, families that participate in projects like the IAN may share some similarities in factors associated with treatment use.

We, like Mandell et al., found a correlation between psychotropic medication use and geographic characteristics. Increased medication use in poorer areas may reflect that these children have less access to behavioral and educational supports and thus use more pharmaceutical interventions, as others have found in more rural areas (Farmer et al. 2009). Although urbanicity itself was not significant in the multivariate analysis, regions with proportionally more urban populations (Northeast, West) were less likely to use psychotropic medications. This disparity suggests that care, like ASD identification (Mandell and Palmer 2005), is subject to regional differences reflecting differential access to specialty health care and/or lack of consistent guidelines for pharmaceutical management of ASD.

In this registry, prevalence of psychotropic medication use was 35%, consistent with other smaller, community-based studies (Aman et al. 2005; de Bildt et al. 2006; Green et al. 2006; Martin et al. 1999; Witwer and Lecavalier 2005) but considerably lower than the 56% found by Mandell et al. (2008). This discrepancy is not unexpected, since Mandell et al. relied on a sample of Medicaid-enrolled children, which likely included a greater proportion of children with severe impairments than did our sample (Martin et al. 2002; Safer et al. 2004; Zito et al. 2005). We found some support for this theory in our data: Among those using psychotropic medications in our study, participants with any Medicaid coverage were more likely than exclusively privately insured or uninsured participants to use multiple medications. Another explanation for the variation is that Medicaid plans tend to have generous formularies (Olfson et al. 2006); coverage for nonpharmaceutical interventions may be less extensive, perhaps indirectly encouraging providers to rely more on medications, given limited resources for other options. These intriguing differences strongly support further population-based research to determine how insurance status independently predicts use of medication.

Another important influence in psychotropic medication use may be prescriber patterns. As ASD diagnoses increase but availability of pediatric specialists remains a limited commodity, both primary care physicians and specialists will need to identify and then match a child’s phenotype to evidence-based, standardized medical and behavioral interventions to reduce adverse effects and improve outcome (Myers et al. 2007; Williams et al. 2004).

Limitations

Although this is the largest report of psychotropic-medication-use patterns in ASD among varied insurance statuses, there are some limitations to reliability and accuracy.

First, our data are provided by Web-based parent-report, so diagnoses and treatment use are not validated. However, current research supports Web-based surveys on medical information as a reliable means of data collection (Gosling et al. 2004). For example, we found that >95% of participants screened positive on SCQ screens, lending validation to at least one parameter, ASD status. Although other studies have relied on medical claims data, these data are supplied by parents who administer the medications, and may better reflect actual use.

Another concern is selection bias, common to other community- and clinic-based studies, toward families with higher socioeconomic status (SES) and with Internet access. Given that nearly 80% of adults aged 18–50 years use the Internet (Jones and Fox 2009), the “digital divide” may not be as important a factor influencing research participation as maternal education (our proxy for SES) and other biases, such as willingness to participate in nonreimbursed medical research and prioritizing leisure time to do so, and trust in the biomedical establishment. These biases are likely distributed throughout the registry, which is arguably an improvement on existing parent- and clinic-based research because of the flexibility of Internet participation. Our conclusions are therefore limited to a comparison of these participants; external validation with the general population is clearly indicated.

We also were limited in that our insurance data were linked to individual treatments rather than individuals, and did not specify the reason for Medicaid eligibility (disability, income, or both). Lastly, because our data include information only on history of (not current status) seizure disorder, we are not able to determine if anticonvulsants are being prescribed for mood-stabilizing or antiepileptic properties.

Despite these limitations, there are important implications from these findings drawn from the largest national autism registry, the Interactive Autism Network, a novel, cost-efficient, and accessible approach to collecting current data from families and individuals with ASD. Our study is consistent with other research associating psychotropic medication use in ASD with older age, presence of intellectual disability or psychiatric comorbidity, and geographic characteristics like county affluence and region. Our data also suggest that insurance status and prescriber influence psychotropic medication use in ASD, adding to the concern that many factors unrelated to presentation affect exposure to psychotropic medication. Hopefully, as knowledge about phenotypic and genotypic responses to pharmaceuticals improves and as effective behavioral and educational interventions become more accessible, uniform standards for comprehensive ASD care will emerge and disperse. In the meantime, however, children with ASD deserve close monitoring of both short- and long-term effects of psychotropic medications on the developing brain and on everyday functioning.

References

Aman, M. G., Lam, K. S., & Van Bourgondien, M. E. (2005). Medication patterns in patients with autism: Temporal, regional, and demographic influences. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 15(1), 116–126.

Aman, M. G., & Langworthy, K. S. (2000). Pharmacotherapy for hyperactivity in children with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(5), 451–459.

American Society of Health System Pharmacists. (2006). AHFS drug information. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or Adolescence. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) (Fourth, Text Revision ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890423349.

Bebbington, A., Anderson, A., Ravine, D., Fyfe, S., Pineda, M., de Klerk, N., et al. (2008). Investigating genotype–phenotype relationships in rett syndrome using an international data set. Neurology, 70(11), 868–875.

Berument, S. K., Rutter, M., Lord, C., Pickles, A., & Bailey, A. (1999). Autism screening questionnaire: Diagnostic validity. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 175, 444–451.

Best, S. J., & Krueger, B. S. (2004). Internet data collection. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bryson, S. E., Rogers, S. J., & Fombonne, E. (2003). Autism spectrum disorders: Early detection, intervention, education, and psychopharmacological management. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry (Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie), 48(8), 506–516.

Chen, A. Y., & Chang, R. K. (2002). Factors associated with prescription drug expenditures among children: An analysis of the medical expenditure panel survey. Pediatrics, 109(5), 728–732.

de Bildt, A., Mulder, E. J., Scheers, T., Minderaa, R. B., & Tobi, H. (2006). Pervasive developmental disorder, behavior problems, and psychotropic drug use in children and adolescents with mental retardation. Pediatrics, 118(6), e1860–e1866.

Farmer, J. E., Marvine, A., Law, K., & Anderson, C. (2009). The impact of urbanicity on diagnosis and treatment of ASD. Presented at IMFAR, Chicago, IL.

Filipek, P. A., Accardo, P. J., Ashwal, S., Baranek, G. T., Cook, E. H., Jr, Dawson, G., et al. (2000). Practice parameter: Screening and diagnosis of autism: Report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American academy of neurology and the child neurology society. Neurology, 55(4), 468–479.

Findling, R. L. (2005). Pharmacologic treatment of behavioral symptoms in autism and pervasive developmental disorders. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66(Suppl 10), 26–31.

Gosling, S. D., Vazire, S., Srivastava, S., & John, O. P. (2004). Should we trust web-based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about internet questionnaires. American Psychologist, 59(2), 93–104.

Green, V. A., Pituch, K. A., Itchon, J., Choi, A., O’Reilly, M., & Sigafoos, J. (2006). Internet survey of treatments used by parents of children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 27(1), 70–84.

Hewson, C., Yule, P., Laurent, D., & Vogel, C. (2003). Internet research methods: A practical guide for the social and behavioral sciences. London: Sage.

Hoagwood, K., Jensen, P. S., Feil, M., Vitiello, B., & Bhatara, V. S. (2000). Medication management of stimulants in pediatric practice settings: A national perspective. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: JDBP, 21(5), 322–331.

Jones, S., & Fox, S. (2009) Generations online in 2009. Pew Internet and American life project. http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/Generations-Online-in-2009. Accessed May 20, 2009.

Langworthy-Lam, K. S., Aman, M. G., & Van Bourgondien, M. E. (2002). Prevalence and patterns of use of psychoactive medicines in individuals with autism in the autism society of North Carolina. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 12(4), 311–321.

Mandell, D. S., Morales, K. H., Marcus, S. C., Stahmer, A. C., Doshi, J., & Polsky, D. E. (2008). Psychotropic medication use among medicaid-enrolled children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 121(3), e441–e448.

Mandell, D. S., & Palmer, R. (2005). Differences among states in the identification of autistic spectrum disorders. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 159(3), 266–269.

Martin, A., Scahill, L., Klin, A., & Volkmar, F. R. (1999). Higher-functioning pervasive developmental disorders: Rates and patterns of psychotropic drug use. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(7), 923–931.

Martin, A., Sherwin, T., Stubbe, D., Van Hoof, T., Scahill, L., & Leslie, D. (2002). Datapoints: Use of multiple psychotropic drugs by medicaid-insured and privately insured children. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 53(12), 1508.

Myers, S. M., Johnson, C. P., & American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children With Disabilities. (2007). Management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 120(5), 1162–1182.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2006) NCHS urban–rural classification scheme for counties. Retrieved November 15, 2008, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/r&d/rdc_urbanrural.htm.

Olfson, M., Blanco, C., Liu, L., Moreno, C., & Laje, G. (2006). National trends in the outpatient treatment of children and adolescents with antipsychotic drugs. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(6), 679–685.

Oswald, D. P., & Sonenklar, N. A. (2007). Medication use among children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 17(3), 348–355.

Posey, D. J., Stigler, K. A., Erickson, C. A., & McDougle, C. J. (2008). Antipsychotics in the treatment of autism. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 118(1), 6–14.

Safer, D. J., Zito, J. M., & Gardner, J. F. (2004). Comparative prevalence of psychotropic medications among youths enrolled in the SCHIP and privately insured youths. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 55(9), 1049–1051.

Shimabukuro, T. T., Grosse, S. D., & Rice, C. (2008). Medical expenditures for children with an autism spectrum disorder in a privately insured population. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(3), 546–552.

Tsai, L. Y. (1999). Psychopharmacology in autism. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61(5), 651–665.

US Census Bureau. (2008). Retrieved October 31, 2008, from http://factfinder.census.gov.

Volkmar, F. R. (2001). Pharmacological interventions in autism: Theoretical and practical issues. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(1), 80–87.

Williams, J., Klinepeter, K., Palmes, G., Pulley, A., & Foy, J. M. (2004). Diagnosis and treatment of behavioral health disorders in pediatric practice. Pediatrics, 114(3), 601–606.

Witwer, A., & Lecavalier, L. (2005). Treatment incidence and patterns in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 15(4), 671–681.

Zito, J. M., Safer, D. J., Zuckerman, I. H., Gardner, J. F., & Soeken, K. (2005). Effect of medicaid eligibility category on racial disparities in the use of psychotropic medications among youths. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 56(2), 157–163.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Autism Speaks. The funder had no role in determining content. We thank Ms. Teresa Foden for proofreading the manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of IAN families, without which this research would not be possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

All authors remain at the same institutions that they were at during the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rosenberg, R.E., Mandell, D.S., Farmer, J.E. et al. Psychotropic Medication Use Among Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders Enrolled in a National Registry, 2007–2008. J Autism Dev Disord 40, 342–351 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0878-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0878-1