Abstract

The relationship between dyadic (eye contact and affect) and triadic (joint attention) behaviours in infancy, and social responsiveness at pre-school age, was investigated in 36 children with Autistic Disorder. Measures of eye contact and affect, and joint attention, including requesting behaviours, were obtained retrospectively via parental interviews and home videos from 0- to- 24-months of age. Concurrent measures (3–5 years) included social responsiveness to another’s distress and need for help. Early dyadic behaviours observed in home videos, but not as reported by parents, were associated with later social responsiveness. Many triadic behaviours (from both parent-reports and home video) were also associated with social responsiveness at follow-up. The results are consistent with the view that early dyadic and triadic behaviours, particularly sharing attention, are important for the development of later social responsiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Impairment in the ability to share attention with a social partner and an object or event (i.e. ‘joint attention’) is one of the most striking early characteristics of children with Autistic Disorder (AD; Sigman and Ruskin 1999; Mundy et al. 1990). The importance of joint attention in the development of language has been well established amongst typically developing children and children with AD (e.g. Baldwin 1995; Sigman and Ruskin 1999; Travis and Sigman 2001). The ability to share attention with others is also related to the development of social understanding in typically developing children (Charman et al. 2000), and to later social relations with peers in children with AD (Sigman and Ruskin 1999). It has been proposed that whilst responding to joint attention (e.g. following another’s gaze) is an earlier developing skill that may be linked to regulating attention and cognitive-executive processes, initiating joint attention (e.g. pointing out an object of interest) is a more advanced skill closely related to social emotional functions (Mundy et al. 1994; Mundy and Sheinkopf 1998).

Although various theoretical accounts of both typical and atypical development propose an important developmental link between joint attention and later emerging social understanding, particularly theory of mind (ToM; e.g. Baron-Cohen 1995; Mundy and Crowson 1997; Striano and Rochat 1999; for reviews, see Flavell 2000; Meltzoff et al. 1999), there is very little empirical evidence for this relationship. There are also no previous studies that trace the relationship between early joint attention in infancy and the affective capacity to respond to others in a social way by showing appropriate empathy, concern, and prosocial responding in the preschool years.

We chose to focus on the developmental association between early joint attention and later social responsiveness with adults because failure to respond in a typical way in social interactions with others is a key criterion for autism (DSM-IV-TR, American Psychiatric Association 2000). Children with AD fail to attend and/or show less concern when an adult displays fear, distress, discomfort or anger (Charman et al. 1998; Dawson et al. 2004; Sigman et al. 1992). Deficits in prosocial responses (helping and sharing) have also been reported (Dissanayake et al. 1996; Sigman and Ruskin 1999; Travis et al. 2001). Furthermore, these children have problems with the perception and interpretation of facial, gestural and vocal emotional expression (Hobson et al. 1988a, b; Loveland et al. 1994).

The only study, to date, to address the relationship between joint attention and social responsiveness in individuals with AD has investigated this relation concurrently. Travis et al. (2001) found that initiating, but not responding to, joint attention was concurrently related to peer engagement (on the play-ground) and prosocial behaviours (e.g. sharing and helping in the laboratory) in a group of children and adolescents with AD aged 8.5- to 18.5- years. However, only a longitudinal study will help to address the impact of joint attention deficits in infancy on the development of social responsiveness in young children with AD. This was one of the aims in the study reported here. Based on Mundy’s thesis that ‘initiating’ joint attention is a higher level social skill which is more closely related to social emotional functions than is ‘responding’ to joint attention (Mundy et al. 1994; Mundy and Sheinkopf 1998), and the different underlying biological processes attributed to these behaviours (Mundy et al. 1992; Mundy 2003), it was hypothesised that initiating joint attention behaviours in early development would be more closely related to later social responsiveness than responding to joint attention behaviours.

A related aim in the current study was to investigate whether there are specific precursors to the joint attention anomaly itself, in particular ‘dyadic’ affect and eye contact, that may be important for later social responsiveness. Dyadic affect refers to the face-to-face exchange of affective or emotional signals between a child and his/her partner (Trevarthen 1979). Dyadic (child-other) competencies are thought to lay the foundation for the development of triadic (child-other-object) competencies (Trevarthen and Hubley 1978). The basic impairment in dyadic affective engagement with others, as originally outlined by Kanner (1943) and re-addressed by Hobson (e.g. Hobson 1986, 1989, 2002), is another hallmark of AD. Centering around these mutual affective exchanges, that both the child and the adult find rewarding, is the motivation to engage in joint attention. Mundy and colleagues (e.g. Mundy and Hogan 1994; Mundy 2003) argue that there is an overall impairment in motivation to engage, and a difficulty recognizing the social value of affect, in AD. Other researchers have similarly suggested that disturbances in early social orienting result from an intrinsically low salience of social stimuli, and a concomitant failure to find social stimuli inherently rewarding (e.g. Dawson et al. 2002). Therefore, the dyadic affective exchanges, which are also embedded in bouts of joint attention, are also likely to have a positive influence on later social responsiveness, as the affective cues promote attention to the other’s emotional states (Dawson et al. 2004).

Understanding others as intentional agents is also necessary for the emergence of the full range of joint attention behaviours. One of the strongest indicators of intentionality is the use of eye gaze with a social partner. Gestures coordinated with gaze usually indicate an intentional stance (Bates et al. 1979). Very early impairments in gaze in children with autism (Clifford and Dissanayake 2008), and its role within dyadic and triadic interactions, may be important when considering the joint attention—social responsiveness link. The current study sought to investigate how individual differences in early dyadic and triadic behaviours contribute to the development of social responsiveness in pre-school aged children with AD. This research was part of a larger study on the early development of dyadic and triadic behaviours in infants with and without AD (see Clifford and Dissanayake 2008). As outlined in that study, given the practical constraints of obtaining infant measures of social behaviours, these measures were indexed retrospectively using both parent reports and the observation of home videos. Given that both gaze and affect are important components of joint attention, it was hypothesized that they, like the joint attention behaviours, particularly initiations of joint attention, will be related to higher level social-affective responsiveness at pre-school age.

Method

Participants

The sample comprised 36 children (3 females; 33 males) with a formal diagnosis of AD made independently by a clinical child psychologist and/or psychiatrist according to the DSM-IV criteria. All diagnostic information was checked by the researchers to ensure that these conformed to the DSM-IV criteria, and then confirmed with the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS, Schopler et al. 1998). Children with a diagnosis of Pervasive Developmental Disorder and children with visual, hearing or physical impairments (e.g. cerebral palsy), were excluded from the study. Children were recruited from associations by way of advertisement in the local autism association (Autism Victoria) newsletters. One family withdrew from the study after the first visit (due to time constraints), and was therefore, excluded due to incomplete data.

All children were aged between 36 and 68 months at recruitment. Their verbal (VMA) and nonverbal (NVMA) mental ages were determined using the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL, Mullen 1995). Current sample characteristics for both the complete and smaller samples are presented in Table 1. It is evident from this table that the sample comprised a mixed ability group, with the majority of children having comorbid intellectual disability.

Measures and Procedures

All participants attended two sessions (1 week apart) at the Child Development Unit at La Trobe University where they were administered a range of measures designed to assess social development (as part of the larger study).

Social Responsiveness

Children’s responsiveness to the following five social settings (under the three headings below, tasks adapted from Dissanayake et al. 1996) were each rated on a 6-point scale (0–5), and then aggregated so that the scores ranged from 0 to 25, and provided an index of social responsiveness. The aggregation of responsiveness (outcome) variables was necessary to reduce the number of analyses. This aggregation was justified as the variables were both theoretically and statistically related.

Empathic Response to Distress and Discomfort

This measured the child’s empathic response toward an adult who (a) pretended to be distressed after knocking her knee on a table (Dissanayake et al. 1996), and (b) pretended to cough/choke on a crisp during a snack break. Facial expressions and vocalizations were used to express distress and discomfort, respectively.

Response to Affectively-Charged Phone Conversation

The experimenter displayed signs of annoyance and concern during a pretend phone conversation by altering her facial expressions and her conversational tone while speaking on the telephone (Dissanayake et al. 1996).

Coding for responsiveness in each of these three settings included whether or not the child discontinued play and looked at the experimenter with interest and/or concern. Scores were based on the 6-point empathy scale used by Dissanayake et al. (1996), ranging from 0 (shows no interest) to 5 (shows intense affective involvement and/or comforting behaviour, e.g., patting the distressed other).

Prosocial Acts of Responsiveness

This test measured the child’s helping response toward the experimenter who spilt a drink on one occasion, and a tin of blocks on another. If the child did not respond spontaneously, a series of prompts were used to elicit prosocial behaviour (e.g. handing the child a napkin). Responses to each of the two situations were coded on a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (no response) to 5 (spontaneously tidies up), and aggregated into a single score with the responses to the three situations described above.

In order to verify that the experimenter had produced the appropriate affective expression and response, a second observer also coded the experimenter’s facial and bodily emotional expression, as well as the intensity, and the believability in 100% of the cases. Although the second observer was blind to the overall aims of the study, she was informed about the intended emotion in each scenario. For the chip choke, the knee knock, and the angry phone call, believability and intensity were rated. For the drink and block spills, only believability was rated. Believability was rated as ‘high’ (96.8% of the drink spills, 98.4% of the chip chokes, 93.6% of the block spills, 84.1% of the knee knocks, and 98.4% of the angry phone calls), with the remaining scenes being evaluated as ‘moderately believable’ and none being rated as ‘not believable.’ The intensity of the emotion displayed was rated as ‘high’ (85.7% of choke emotions, 81% of knee knock emotions, and 85.7% of angry phone call emotions), with the remaining ratings being ‘moderate intensity’. One coder coded 100% of the social responsiveness scenarios, with a second coder coding 10% of tapes. The two coders rates of agreement was between 90 and 100% for each of the separate social responsiveness subscales.

Infancy Behaviours

The infancy dyadic (affect and eye contact) and triadic (joint attention and requests) variables were coded for 6-monthly intervals over the infancy period through both parental interview and video observation. While the parent(s) of all participants were interviewed regarding their child’s early development, only 22 families had video tapes available of their child’s first 2 years of life. There were no differences on any of the sample characteristics between the parent interview and video samples (see Table 1).

Parent Interviews

Parents were informed they would be asked about their child’s early social development, but were unaware of the specific aims of the study. The parent interview comprised 21 questions, about each 6 monthly age range throughout infancy. The questions were repeated (where relevantFootnote 1) for each developmental period to measure the specific behaviours outlined in Table 2 below (operational definitions of each are presented in the “Appendix”). Anchor points (such as memorable birthday parties, christenings, and Christmas’), were first established in order to facilitate memory of each relevant age. As the current age of the children in this study ranged between 3 and 5 years, parents were recalling relatively recent events, so that the time between the behaviours of interest being displayed and later reported was relatively short.

Parents responded verbally to each question using a five point scale ranging from always to never. For a detailed description of the infancy measures, and how they were derived, see Clifford and Dissanayake (2008).

Home Videos

Segments of videos were randomly selected for coding, and the behaviours of interest (see Table 2) were coded as frequencies counts and, in some cases, as quality measures (these latter variables are labelled as qualitative throughout this paper) using The Observer software package (Noldus 2000). Where possible, the infant was observed for exactly 10 min at each of four ages, excluding video segments where the infant was not in view. Due to the limited number of participants with video data across each of the four 6-monthly time frames throughout infancy, it was necessary to combine these into yearly intervals (0–11 months and 12–24 months). This resulted in 18 children with footage across the first year, and 22 children (which included the aforementioned 18 children as well as 4 additional children) with footage across the second year of life. The age of the infant was obtained from date markings on their home videotapes, and confirmed with the parent/caregiver. There were two variables from the first year that were excluded from analyses since they were infrequent (occurred 6 times or less within the 10 min) and thus violated the assumptions of normality: responds to joint attention and responds to request.

As it is possible that parents who suspected a problem before taping their child may have a different taping style and/or interaction style than those parents who had not yet suspected a problem, possible differences between these two sub-groups were analysed. Ten videos (of all four original ages) were taped before parents suspected a problem. Independent samples t tests revealed there were no significant differences for context, level of interaction, or amount of toys, between the AD videos that were taped before suspecting a problem and after suspecting a problem (ps > .05).

Inter-Rater Reliability of Home Video Infancy Variables

A second observer, blind to the diagnoses in all cases and aims of the study, coded 10% of the videotapes for reliability purposes. The intra class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for each of the behaviours (see Table 2) were generally good to excellent, ranging from .67 (eye contact) to .98 (joint attention quality).

Results

The associations between early dyadic and triadic behaviours (infancy variables) and the social responsiveness measures (preschool variable) were examined using Pearson’s Product Moment Correlation Coefficients. Where the infancy and outcome measures were related to the developmental variables of chronological age (CA) and/or VMA, these variables were controlled for by using partial correlations. Given that VMA and NVMA were so highly correlated (r = .81, p < .001), only VMA and CA were partialled out in the correlations. Due to the multiple analyses, only correlations above .4 are reported.Footnote 2

Interview Investigation

There were no meaningful associations between parent reports of first year behaviours and current social responsiveness (see Table 3). Although none of the second year dyadic behaviours were significantly correlated with later social responsiveness, there were several triadic behaviours of importance. Abnormality ratings for points for interest, shows for interest, shares caregiver’s affect in social referencing, and points for request at 12–18 months were all negatively associated with later social responsiveness measured in the laboratory.

For the 18–24 month age range, correlations between dyadic variables and outcome variables were again low. However, once again, there were many correlations between the triadic behaviours and later social responsiveness. Poor ratings for triadic smiles, follows another’s point, points and shows for interest, social referencing, and points for request were all negatively and significantly related to later social responsiveness (Table 4).

Video Investigation

As with the parent report data, none of the first year dyadic variables were related to social responsiveness (seen in Table 5). Observed gaze switches was the only triadic behaviour moderately related to later social responsiveness; however, this relationship was dependent on VMA, and was no longer significant after controlling for this variable (r = .15, p > .10).

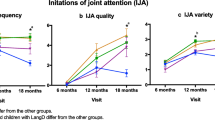

There were many significant correlations between the second year variables and later social responsiveness (see Table 5), which is consistent with the findings from the parent report data. Unlike the parent report data, ratings for dyadic behaviours seen in the videos were also important. Abnormal quality ratings for eye contact were strongly and significantly related to later social responsiveness (in a negative direction). The quality ratings for affect and frequency of social smiles were also important for later social responsiveness. Of the triadic behaviours, rates of initiates joint attention was moderately related to later social responsiveness; however, this relationship was dependent on VMA, and became unreliable in the partial correlations (r = .25, p > .1). The gaze switches behaviour was again related strongly to social responsiveness, and, unlike in the first year of life, these relationships were independent of VMA. The overall abnormal quality of joint attention in the second year was also negatively related to social responsiveness.

Discussion

The aims in the current investigation were to investigate the associations between the earliest forms of non-verbal communication during infancy and later social responsiveness at preschool age in children with AD. An important finding was the strong positive relationships between initiating joint attention behaviours reported by parents and as seen in home videos and later social responsiveness to others. However, VMA was seen to mediate the latter relationship which became insignificant after co varying this developmental variable. This mediation was not unexpected given the strong associations between language and joint attention, and the proposed links between each of these variables and later social development. Another important finding is that across both investigations, the presence of affect in dyadic and triadic contexts appears important to later social responsiveness. Unexpectedly, few dyadic parent report behaviours were associated with later social responsiveness, yet dyadic behaviours observed in the home videos in the second year of life were correlated with social responsiveness at preschool age. Possible reasons for this will be discussed.

Dyadic Behaviours

There were no correlations between parent reported or video based dyadic behaviours in the first year of life and later social responsiveness, nor were there any significant relationships for the parent reported dyadic behaviours in the second year. However, of the video taped behaviours observed in the second year of life, both the quality of affect as well as the frequency of social smiles were strongly related to later social responsiveness. The quality of eye contact, but not the frequency of eye contact, during the second year of life was also an important precursor to later social responsiveness.

Triadic Behaviours

There were no correlations between parental reports of first year triadic behaviours and later social responsiveness. For the video data, the only triadic behaviour during the first year of life which correlated with later social responsiveness was the frequency of gaze switches; however, this association was dependent on VMA. The lack of relationships during the first year across both studies is not surprising as triadic behaviours are only just beginning to emerge toward the end of the first year of life.

Parental reports of triadic interactions in the second year highlight the importance of affect. In particular, triadic smiles and shares caregiver’s affect in social referencing were correlated with later social responsiveness, suggesting that shared affective behaviours in the second year of life are important in the later development of responsiveness to other’s emotions and behaviour.

Amongst the joint attention behaviours that were important, the initiating behaviours reported by parents across the second year (i.e. points for interest and shows for interest) and those observed on the videos (initiates joint attention) were consistently related to social responsiveness at outcome. While the responding behaviours reported by parents for the 18- to 24- month range (following another’s point) was related to social responsiveness, those reported for the earlier age ranges and those observed in the videos were not. While the preferred explanation (discussed further below) is that it is the child initiated behaviours that are important for later social responsiveness, another is that the lack of a similar finding in the video study may have been due to the reduced number of participants in this investigation.

Parent reported requesting behaviours (using pointing) across the second year of life were related to later social responsiveness. In contrast, none of the requesting behaviours were associated with the outcome measure in the video investigation. Taken together, the results of both studies suggest that the joint attention behaviours are more important in the development of social responsiveness than are the requesting behaviours. This finding accords with the results of Travis et al. (2001), who found that initiating joint attention was concurrently related to prosocial sharing and helping behaviours in a laboratory setting, as well as to peer engagement on the play-ground, in a group of older children with AD. In sum, the results of both infancy studies largely support the position that joint attention is related to later social responsiveness. The results also suggest that, across the first two year of life, affect behaviours—whether in a dyadic or triadic context—are especially important for later social responsiveness.

Theoretical Implications

The most notable pattern of results across both investigations was that early affect and joint attention skills had the greatest association with later responsiveness to another’s distress and need for help. The results support the notion that affective exchanges in dyadic and triadic situations serve as a foundation for later social competencies such as responding appropriately to others needs. Longitudinal research on joint attention has largely been restricted to language and cognitive outcomes. This study is one of the first to establish that early shared affective exchanges within both dyadic and triadic (joint attention) contexts are indeed important for later responsiveness to another person.

The current findings, although largely based on simple time lag correlations, lend support to recent social orienting theories of autism, in which children fail to learn the reward value of dyadic interactions (Dawson et al. 2002; Mundy 2003). Mundy (1995) postulated that joint attention behaviours have a social-emotional approach function, initiating episodes of “affectively positive intersubjectivity” essential for higher social-cognitive development. Thus impaired joint attention behaviours in AD have negative ramifications for the development of intersubjectivity (and later social understanding). Other researchers have agreed with the hypothesis that the reward value plays an important role in identifying social information as relevant (e.g. Dawson et al. 2002). Mundy (2003) later proposed that joint attention and social cognition are at least partially mediated by the neural system subserving affiliative, affective interactions, and that the DMFC/AC complex may ‘contribute a neurofunctional platform from which the essential human capacity for intersubjectivity springs’ (p. 804).The significant associations found in this study may reflect the shared neural underpinnings to which Mundy refers. The current findings signify that the affect in joint attention may foster a sensitivity to affective cues and affective engagement required in social responsiveness (Dawson et al. 2004; Mundy 1995, 2003). Thus, impairments evident in affective engagement and in joint attention skills may hinder the development of sensitivity to affective cues, and ultimately the acquisition of social responsiveness skills.

The current finding also indicate that, as predicted, the initiating joint attention behaviours (e.g. showing and pointing to direct attention to an object of interest) were more commonly associated with later social development than the responding to joint attention (e.g. following another’s gaze or point to an object of interest) behaviours. This pattern may be explained by the proposal of Mundy and his colleagues that initiating joint attention is a more advanced skill, closely related to social emotional functions (Mundy et al. 1994; Mundy and Sheinkopf 1998). In contrast, different underlying neurological processes have been postulated for responding to joint attentions, and also for requesting behaviours (Mundy 1995), which may help explain the limited impact of these on later social responsiveness found in the current study. The application of Mundy’s theory to the current results suggests that impairments in social responsiveness could result from impairments in the social system underlying initiation of joint attention abilities.

While eye contact behaviours reported by the parents were not related to later social responsiveness, there was a strong and significant relationship between the quality of eye contact (e.g. clear, flexible, socially modulated, and of appropriate duration), as measured via video observation, and later social responsiveness. The finding that eye contact—one of the strongest indicators that an infant is intending to communicate with another person (Bates et al. 1979),—impacted later social responsiveness is fitting with the idea that intentionality also impacts more complex understanding of mental states (Malle 2001).

There is far less theory on the role of eye contact in the association between joint attention and later social development than there is for the role of affect. Whilst Mundy’s (1995, 2003) important social orienting theory largely neglects the role of eye contact in the development of social cognitive skills, he cites a study (with non-autistic individuals) in which eye contact and gaze aversion also activate components of the medial-frontal cortex (Calder et al. 2002). Gaze fixation has also been found to be associated with activation in the amygdala and fusiform gyrus in individuals with AD (Dalton et al. 2005). In a study on dyadic and triadic orientation, Leekam and Ramsden (2006) found that looking to another person’s eyes in response to an attention bid (dyadic orienting) was concurrently related to initiating joint attention as well as responding to joint attention, with the former being highly significant. Our results suggest that this is an area in need of further investigation, with emphasis on the longitudinal associations and their relationship to social development. However, it must be pointed out the current video finding regarding eye contact should be interpreted tentatively as it was not confirmed by the parent report data. Further research using a larger sample of (videos of) children with AD is needed before arriving at firm conclusions regarding the importance of gaze in later social development.

Limitations and Future Suggestions

A limitation in this study is the reliance on correlational analyses to infer relationships, which also do not preclude the possibility that associations between the variables of interest are determined by other factors not considered here, such as other child characteristics (e.g., temperament) and environmental factors. With larger sample sizes, it would be possible to test more complex multifactorial models, so that the unique contribution of the infancy variables to later social responsiveness may be assessed. The results from the video investigation need to be interpreted with caution due to the reduced participant numbers (n = 22). However, the sample size is comparable with previous studies on home videos, where the following groups sizes have been used: 8 (e.g. Bernabei et al. 1998); 11 (e.g. Baranek 1999; Osterling and Dawson 1994); 12 (Adrien et al. 1992); 15 (Werner et al. 2000); 20 (Osterling et al. 2002); and 25 (e.g., Maestro et al. 1999). A related issue is that although the sample did include some high functioning children, overall, the group was relatively low functioning; thus generalisation to children without comorbid intellectual disability is limited. Furthermore, the current study considered infant data from two sources (video and parent report). Although there are some remarkable similarities in the findings from these two data sources, replication of these results with higher participant numbers is desirable.

There are also some inherent methodological problems with both the video and parent interview studies. Video studies present difficulties such as estimating and controlling for subjects’ ages, the varying content of the videos, and the non-random sampling of a child’s behaviour. Every effort was made in the present study to control these limitations by randomly sampling the video segments, and by clarifying the infants’ ages with parents. The main limitation in the interview investigation was in the assessment of changes over time. As children develop rapidly over the period of infancy, the accuracy of the reported changes must be questioned. Although every effort was made to ensure that the parents were focussed on the correct age range (by using anchor events such as birthdays) and, at most, parents were reporting on the previous 5 years, it is possible that there may have been memory errors and biases in parent reports. Thus these results should not be interpreted in isolation, but along with the more objective video findings. Clinical implications of this type of research are many, with the most important being the identification of the early predictors of later outcome, so that intervention can target these behaviours early on in development.

Summary and Conclusions

The current study is the first to establish that early affect, and to some extent, gaze behaviours, along with early joint attention behaviours, are related to later social responsiveness amongst children with AD. Furthermore, the association of early joint attention and later social responsiveness was largely confined to the ability to initiate bids for joint attention. Although some requesting behaviours predicted later social responsiveness, they were not as influential as the joint attention behaviours. Despite the study limitations, the findings are important since they lend support to the social orienting models of AD, which may now be directly tested in the prospective sibling studies that are now underway. Moreover, the findings provide support for focusing on both dyadic orienting and triadic joint attention in the development of early intervention programs.

Notes

For example, initiating joint attention was not asked for the 0-5 month age range since these behaviours do not typically emerge until the end of the first year of life.

Given the small subject numbers in the study, the decision was made to report on only those correlations with an r value >.4 along with p values <.05. Bonferroni correction was not applied since this would inflate Type II error to unacceptable levels.

References

Adrien, J. L., Perrot, A., Sauvage, D., Leddet, I., Larmanade, C., Hameury, L., et al. (1992). Early symptoms in autism from family home movies: Evaluation and comparison between 1st and 2nd year of life using I.B.S.E. Scale. Acta Paedopsychiatrica: International Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(2), 71–75.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th text revised ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Baldwin, D. A. (1995). Understanding the link between joint attention and language. In C. Moore & P. Dunham (Eds.), Joint attention: Its origins and role in development (pp. 131–158). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Baranek, G. T. (1999). Autism during infancy: A retrospective video analysis of sensory-motor and social behaviors at 9–12 months of age. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 29(3), 213–224. doi:10.1023/A:1023080005650.

Baron-Cohen, S. (1995). Mindblindness: An essay on autism and theory of mind. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Bates, E., Benigni, L., Bretherton, I., Camaioni, L., & Volterra, V. (1979). Cognition and communication from 9–13 months: correlational findings. In E. Bates, L. Benigni, I. Bretherton, L. Camaioni, & V. Volterra (Eds.), The emergence of symbols (pp. 69–140). NY: Academic Press.

Bernabei, P., Camaioni, L., & Levi, G. (1998). An evaluation of early development in children with autism and pervasive developmental disorders from home movies: Preliminary findings. Autism, 2, 243–258. doi:10.1177/1362361398023003.

Calder, A., Lawrence, A., Keane, J., Scott, S., Owen, A., Christoffels, I., & Young, A. (2002). Reading the mind from eye gaze. Neuropsychologia, 40, 1129–1138.

Charman, T., Baron-Cohen, S., Swettenham, J., Baird, G., Cox, A., & Drew, A. (2000). Testing joint attention, imitation, and play as infancy precursors to language and theory of mind. Cognitive Development, 15(4), 481–498. doi:10.1016/S0885-2014(01)00037-5.

Charman, T., Swettenham, J., Baron-Cohen, S., Cox, A., Baird, G., & Drew, A. (1998). An experimental investigation of social-cognitive abilities in infants with autism: Clinical implications. Infant Mental Health Journal, 19(2), 260–275. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0355(199822)19:2<260::AID-IMHJ12>3.0.CO;2-W.

Clifford, S., & Dissanayake, C. (2008). The early development of joint attention in infants with autistic disorder using home video observations and parental interview. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 791–805. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0444-7.

Dalton, K., Nacewicz, B., Johnstone, T., Schaefer, H., Gernsbacher, M. A., Goldsmith, H., et al. (2005). Gaze fixation and the neural circuitry of face processing in autism. Nature Neuroscience, 8, 519–526.

Dawson, G., Carver, L., Meltzoff, A. N., Panagiotides, H., & McPartland, J. (2002). Neural correlates of face recognition in young children with autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, and typical development. Child Development, 73, 700–717.

Dawson, G., Toth, K., Abbott, R., Osterling, J., Munson, J., Estes, A., et al. (2004). Early social attention impairments in autism: Social orienting, joint attention, and attention to distress. Developmental Psychology, 40(2), 271–283. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.271.

Dissanayake, C., Sigman, M., & Kasari, C. (1996). Long-term stability of individual differences in the emotional responsiveness of children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 37(4), 461–467. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01427.x.

Flavell, J. H. (2000). Development of children’s knowledge about the mental world. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 24, 15–23. doi:10.1080/016502500383421.

Hobson, R. P. (1986). The autistic child’s appraisal of expressions of emotion: A further study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 27, 671–680. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1986.tb00191.x.

Hobson, R. P. (1989). On sharing experiences. Development and Psychopathology, 1, 197–203. doi:10.1017/S0954579400000390.

Hobson, P. (2002). The cradle of thought. Hampshire, England: Macmillan Education Ltd.

Hobson, P., Ouston, J., & Lee, A. (1988a). What’s in a face? The case of autism. The British Journal of Psychology, 79, 441–453.

Hobson, P., Ouston, J., & Lee, A. (1988b). Emotion recognition in autism: Coordinating faces and voices. Psychological Medicine, 18, 911–923.

Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2, 217–250.

Leekam, S., & Ramsden, C. (2006). Dyadic orienting and joint attention in preschool children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 185–197. doi:10.1007/s10803-005-0054-1.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., Di Lavore, P., & Risi, S. (1999). Autism diagnostic observation schedule-WPS Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Loveland, K., Tunali-Kotoski, B., Pearson, D., Brelsford, K., Ortegon, J., & Chen, R. (1994). Imitation and expression of facial affect in autism. Development and Psychopathology, 6, 433–444. doi:10.1017/S0954579400006039.

Maestro, S., Casella, C., Milone, A., Muratori, F., & Espasa, F. P. (1999). Study of the onset of autism through home movies. Psychopathology, 32(6), 292–300. doi:10.1159/000029102.

Malle, B. (2001). Folk explanations of intentional action. In B. Malle, L. Moses, & J. Louis (Eds.), Intentions and intentionality: Foundations of social cognition (pp. 265–286). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Meltzoff, A. N., Gopnik, A., & Repacholi, B. M. (1999). Toddlers’ understanding of intentions, desires, and emotions: Explorations of the dark ages. In P. D. Zelazo, J. W. Astington, & D. R. Olson (Eds.), Developing theories of intention: Social understanding and self-control (pp. 17–41). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Eribaum Associates Inc.

Mullen, E. (1995). Mullen scales of early learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance.

Mundy, P. (1995). Joint attention and social-emotional approach behavior in children with autism. Development and Psychopathology, 7(1), 63–82. doi:10.1017/S0954579400006349.

Mundy, P. (2003). The neural basis of social impairments in autism: The role of the dorsal medial-frontal cortex and anterior cingulate system. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 44(6), 793–809. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00165.

Mundy, P., & Crowson, M. (1997). Joint attention and early social communication: Implications for research on intervention with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 27, 653–676. doi:10.1023/A:1025802832021.

Mundy, P., & Hogan, A. (1994). Intersubjectivity, joint attention, and autistic developmental pathology. In D. Cicchetti & S. Toth (Eds.), Disorders and dysfunctions of the self. Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology (Vol. 5, pp. 1–30). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Mundy, P., Kasari, C., & Sigman, M. (1992). Nonverbal communication, affective sharing, and intersubjectivity. Infant Behavior and Development, 15, 377–381. doi:10.1016/0163-6383(92)80006-G.

Mundy, P., & Sheinkopf, S. J. (1998). Early communication skill and developmental disorders. In J. Burack, R. Hodapp, & E. Zigler (Eds.), Handbook of mental retardation and development (pp. 183–207). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mundy, P., Sigman, M., & Kasari, C. (1990). A longitudinal study of joint attention and language development in autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 20(1), 115–128. doi:10.1007/BF02206861.

Mundy, P., Sigman, M., & Kasari, C. (1994). Joint attention, developmental level, and symptom presentation in autism. Development and Psychopathology, 6, 389–401. doi:10.1017/S0954579400006003.

Noldus. (2000). The Observer 4.0 [Computer software]. Wageningen, The Netherlands: Noldus Information Technology.

Osterling, J., & Dawson, G. (1994). Early recognition of children with autism: A study of first birthday home videotapes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24, 247–257. doi:10.1007/BF02172225.

Osterling, J., Dawson, G., & Munson, J. (2002). Early recognition of 1-year-old infants with autism spectrum disorder versus mental retardation. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 239–251. doi:10.1017/S0954579402002031.

Schopler, E., Reichler, J., & Renner, B. (1998). The childhood autism rating scale (CARS). CA: Western Psychological Services.

Seibert, J., Hogan, A., & Mundy, P. (1982). Assessing interactional competencies: The Early Social-Communication Scales. Infant Mental Health Journal, 3, 244–258.

Sigman, M. D., Kasari, C., Kwon, J., & Yirmiya, N. (1992). Responses to the negative emotions of others by autistic, mentally retarded, and normal children. Child Development, 63, 796–807. doi:10.2307/1131234.

Sigman, M., & Ruskin, E. (1999). Continuity and change in the social competence of children with autism, down syndrome, and developmental delays. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 64(1), v–114.

Striano, T., & Rochat, P. (1999). Developmental link between dyadic and triadic social competence in infancy. The British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 17(4), 551–562. doi:10.1348/026151099165474.

Travis, L., & Sigman, M. (2001). Communicative intentions and symbols in autism: Examining a case of altered development. In J. Burack, T. Charman, N. Yirmiya, & P. Zelazo (Eds.), The development of autism: Perspectives from theory and research (pp. 279–308). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Travis, L., Sigman, M., & Ruskin, E. (2001). Links between social understanding and social behavior in verbally able children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(2), 119–130. doi:10.1023/A:1010705912731.

Trevarthen, C. (1979). Communication and cooperation in early infancy: A description of primary intersubjectivity. In M. Bullowa (Ed.), Before speech: The beginning of human communication (pp. 321–347). London: Cambridge University Press.

Trevarthen, C., & Hubley, P. (1978). Secondary intersubjectivity: Confidence, confiding and acts of meaning in the first year. In A. Lock (Ed.), Action, gesture and symbol (pp. 183–299). London: Academic Press.

Werner, E., Dawson, G., Osterling, J., & Dinno, N. (2000). Brief report: Recognition of autism spectrum disorder before one year of age: A retrospective study based on home videotapes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(2), 157–162. doi:10.1023/A:1005463707029.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the families who willingly gave their time to participate in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This research formed part of the first author’s doctoral dissertation, which was conducted under the supervision of the second author at La Trobe University.

Appendix

Appendix

Operational Definitions and Coding Criteria for Video Study Variables

1. Eye contact: The infant looks directly into the person’s face/eyes; here it is clear that the infant is looking at a person, and not the camera.

*Coding example for quality.

0 = infant shows age and contextually appropriate level of eye-contact with other persons that is clear, flexible, socially modulated and of appropriate duration.

1 = infant shows a slight deficiency in eye-contact with other persons, but does engage in some eye-contact (i.e. eye-contact occurs but may be fleeting and of short duration, or may sometimes consist of empty, lifeless or vacant stares;

2 = infant shows a moderate deficiency in eye-contact with other persons, rarely engaging in eye-contact and with extremely short duration, or may often consist of empty, lifeless or vacant stares, or somewhat poorly modulated eye contact;

3 = infant never engages in eye-contact or continuously stares vacantly and lifelessly, or displays poorly modulated eye contact in interactions.

2. Responds to name call: Infant looks directly at person calling them. If there is repeated calling, code a new look after 3 sec has elapsed.

3. Social smile: The infant smiles at a person while looking at them (initiating the smile); the infant responds to the smile of a caregiver by returning a smile immediately after the caregiver initiated that smile (reciprocal).

4. Shared positive affect: The infant demonstrates at least one of the following behaviours (in addition to a social smile): laughs, giggles, shows joy, happiness, facial enthusiasm, elevation, excitement; and combines these with some eye contact all while in close proximity to another person’s face. The infant wants to share enjoyment and excitement with the caregiver and directs toward the caregiver.

5. Joint attention gaze switching (checking/looking behaviour: sharing through eye contact): Infant looks at another person’s face in the presence of something interesting (possibly while holding/activating a toy) and then looks back at that object/event (in a sense ‘checking’ that the person has seen the object/event; Infant looks to caregiver to within 2 sec of a toy ceasing and then back to toy.

6. Initiating joint attention (Proto-declarative pointing/showing/giving/pushes toward for sharing, not to obtain or to request the removal of a toy): The infant points at a (proximal or distal) object in order to direct the caregiver’s attention to the object to share interest in the object; brings an object/hands object to a person or extends arm in the direction of the person’s face to show the object (not associated with need for help).

7. Responding joint attention (gaze monitoring and point following): The infant follows the caregiver’s point, gaze or head turn by moving their own head and focus or turning in the same direction in which the caregiver is looking, pointing, or showing interest (attention to a common focus). The caregiver may be vocalising too (e.g. “look”).

8. Social referencing: Infant looks at another person’s face in the presence of something ambiguous/threatening for information (and then may look back at that object/event).

9. Initiate requests (proto-imperatives): The infant points or extends arm and hand toward a desired object which aids the infant in obtaining the object (is part of a request for something out of reach; is often accompanied by vocalisation); infant gives object/pushes object toward caregiver in order to obtain help “do it again” or to “get rid” of something they do not want.

10. Responds to requests: The infant responds to the request of another (verbal or gestural) by, for example, giving an object to another person when they request it with an open palm; coming to ‘sit down’ when signal is given; labelling.

Note: The Early Social Communication Scales, Seibert et al. (1982) and the ADOS-G Module 1/2 (Lord et al.1999) were used in the development of these operational definitions.

Parent Interview Summary

Parents to answer in terms of this scale and interviewer to record answer:

Eye contact (All questions asked for: 0–6; –12; 12–18; and 18–24 months).

1. While in close proximity to your child (e.g. when sitting with your child on your lap facing you, while sitting close together at the table, at bath time) did your child gaze into your eyes?

2. When you try to get your child’s attention, did you ever feel that your child avoids looking directly at you?

3. Was it difficult to get eye contact initially with your child? (i.e. to ‘catch’ your child’s eye).

4. Was your child’s eye contact ever unpredictable?

5. Did your child seem to display abnormal eye contact, that is, the QUALITY seems to be different (e.g. an empty or lifeless expression, fleeting or piercing looks).

Eye contact and affect (All questions asked for: 0–6; 6–12; 12–18; and 18–24 months).

6. Did your child participate in peek-a-boo games? (i.e. a hiding behind a cloth and then being surprised in an anticipatory manner).

7. Did your child combine smiling and eye contact in interactions with you? (e.g. look at you smiling, make eye contact with you and smile at the same time).

Affect (All questions asked for: 0–6; 6–12; 12–18; and 18–24 months unless stated).

8. Does your child smile during interactions with you while playing with another object or sharing an event (e.g. smile at you when a mechanical toy is operating, or when an animal is near)?

(Interviewer Note: not asked for the first 6 months, as this behaviour is not generally shown during this age).

9. While close to your child (i.e. face to face with eye contact) how often did your child INITIATE smiles with you (i.e. smile spontaneously, first)?

10. Did your child smile IN RESPONSE to your smile?

11. Did your child use his/her emotions appropriately? (e.g. cry when sad; smile and laugh when happy; show a fearful face when scared etc.).

Joint attention (All questions asked for: 6–12; 12–18; and 18–24 months unless stated).

12. Did your child look at things you pointed at (follow your point)?

13. Did your child look at things you look at (follow your gaze)?

14. How often did your child use his/her index finger to point to indicate INTEREST in something (or extend his/her arm and hand to indicate like an approximation of a point)?

15. Did your child ever bring objects over to you, to SHOW you something?

(Interviewer Note: not asked for the first 12 months, as this behaviour is not generally shown during this age).

16. Did your child ever bring objects over to you, to GIVE you something?

(Interviewer Note: not asked for the first 12 months, as this behaviour is not generally shown during this age).

17. Did your child try and attract your attention to his/her own activity by looking back and forth between you and the object (and possibly vocalising)? (Demonstrate behaviour).

18. Did your child look at your face to check your reaction when faced with something unfamiliar? (e.g. a new toy, a stranger).

19. Does your child share your affect when faced with something unfamiliar (e.g. if you look uncertain, your child looks uncertain)?

Requesting (All questions asked for: 6–12; 12–18; and 18–24 months).

20. Did your child ever use his/her index finger to point to ASK for something (or extend his/her arm and hand to ASK)?

21. Did your infant ever BRING you something in attempt to request something (e.g. a toy to be activated or a box to be opened, often accompanied with a vocalisation such as a whine)?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clifford, S., Dissanayake, C. Dyadic and Triadic Behaviours in Infancy as Precursors to Later Social Responsiveness in Young Children with Autistic Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 39, 1369–1380 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0748-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0748-x