Abstract

We compared disruptive behaviors in boys with either autism spectrum disorder (ASD) plus ADHD (n = 74), chronic multiple tic disorder plus ADHD (n = 47), ADHD Only (n = 59), or ASD Only (n = 107). Children were evaluated with parent and teacher versions of the Child Symptom Inventory-4 including parent- (n = 168) and teacher-rated (n = 173) community controls. Parents rated children in the three ADHD groups comparably for each symptom of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder. Teacher ratings indicated that the ASD + ADHD group evidenced a unique pattern of ODD symptom severity, differentiating them from the other ADHD groups, and from the ASD Only group. The clinical features of ASD appear to influence co-morbid, DSM-IV-defined ODD, with implications for nosology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Childhood aggression has long been recognized as one of the most common and persistent forms of childhood maladjustment (Biederman et al. 1996; Brame et al. 2001; Broidy et al. 2003), and predictive of a range of negative adolescent and adult outcomes including continuing aggression, failure in school and work settings, substance abuse, and later-onset psychopathology (Moffitt 1993; Patterson et al. 1989; Tremblay 2000). This, combined with the findings of numerous studies indicating that psychiatric co-morbidity is associated with greater symptom severity and persistence, number of mental health risk factors, negative outcomes and more intractable course compared with mono-morbidity (e.g., Capaldi 1992; Connor et al. 2003; Jensen et al. 1997), make the study of aggression in children with clinical features that are likely to exacerbate aggression of particular interest. Two such characteristics commonly associated with childhood psychiatric disorders are impaired social cognition [e.g., autism spectrum disorder (ASD)] and behavioral disinhibition [e.g., attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), chronic multiple tic disorder (CMTD)]. In the case of ASD, the deficits in social cognition impacting the individual’s ability to recognize and infer mental states (e.g., intentions, beliefs, desires, etc.) in oneself and others, and to understand that others have beliefs, desires and intentions that are different from one’s own (e.g., Loth et al. 2008), is likely to impact aggression, particularly when paired with language difficulties (e.g., Werner et al. 2006).

ASD (i.e., autistic disorder, Asperger’s syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder-NOS) is commonly associated with ADHD (e.g., Frazier et al. 2001; Goldstein and Schwebach 2004; Montes and Halterman 2007), with screening prevalence rates as high as 50% in referred samples (Gadow et al. 2006). ADHD in children with ASD is often associated with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) (Gadow et al. 2006, 2008a) and other types of aggression (e.g., Hughes et al. 2002; Singh et al. 2006). Children with ASD also often exhibit the symptoms of CMTD (Gadow and DeVincent 2005), and children with CMTD are reported to be at relatively higher risk for explosive outbursts (e.g., Budman 2006; Budman et al. 2003). Although the extant literature has adequately documented the co-occurrence of aggression in children with ASD with and without co-morbid ADHD or CMTD, most of this research has focused on summary or composite scores of child aggression from behavior ratings scales. For example, in a previous report we compared parent and teacher ratings of the overall severity of ODD and conduct disorder (CD) symptoms in children with either ASD + ADHD, CMTD + ADHD, or ADHD Only (Gadow et al. 2009). Although analyses indicated comparable levels symptom severity in these three phenotypically similar groups of children with ADHD, we suspect this is only a partial picture.

What is not known is whether co-morbid neuro-developmental disorders contribute to differences in specific types of aggressive behavior, which may ultimately be important not only for understanding the pathophysiology of aggression but also ASD. The notion that a more molecular analysis of behavioral constructs or clinical phenotypes may be helpful in understanding the etiology of ASD (and neurobehavioral disorders in general) is addressed in three thoughtful reviews by Abrahams and Geschwind (2008), Belmonte et al. (2004), and Szatmari et al. (2007). Owing to the implications of (a) social cognition deficits for aggression in boys, particularly less verbal ones (Werner et al. 2006), (b) findings that children at-risk for ADHD were not found to be impaired when completing advanced social cognition tasks compared to controls (Charman et al. 2001; Perner et al. 2002), (c) the importance of genetic factors in the etiology of both ASD (e.g., Ronald et al. 2005; Rutter et al. 1999) and CMTD (e.g., Comings et al. 1996; Grados et al. 2008), and (d) the role of environmental variables in child aggression (Bohman 1996; Cadoret et al. 1995; Rutter et al. 1999), it is reasonable to assume that biologic substrates of ASD, ADHD, and CMTD may interact with environmental variables resulting in different patterns of ODD and CD behaviors.

The present study examined the perceived severity of specific ODD and CD symptoms in four groups of clinically-referred boys (ASD + ADHD, CMTD + ADHD, ADHD Only, ASD Only) and a community-based comparison sample (Controls). Owing to the limited research about this topic, by necessity this study is hypothesis generating and not hypothesis confirming. Nevertheless, based on prior research, we expected: (1) the three groups of ADHD boys to obtain more severe ratings for most symptoms of disruptive behavior compared with Controls (Gadow et al. 2009), but this would likely be less evident for symptoms that tapped social cognition abilities in the ASD + ADHD group; (2) the ASD + ADHD group would demonstrate differentially more severe ODD and CD symptoms compared to children with ASD Only; and (3) deficits in social cognition associated with ASD will result in differentially higher levels of ODD and CD behaviors in ASD children who are not ADHD versus Controls; and (4) given the importance of environmental variables in child aggression, group differences will vary as a function of mother versus teacher report (e.g., Drabick et al. 2007; Hudziak et al. 2005).

Method

Participants

Referred Samples

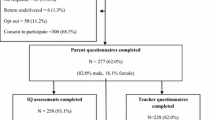

Four groups of clinically-referred boys participated in this study (Table 1), all of whom lived in the same geographic area and were evaluated in the same university hospital clinic using identical measures: ASD + ADHD (n = 74), ASD Only (n = 107), CMTD + ADHD (n = 47), and ADHD Only (n = 59). The two non-ASD samples were recruited for participation in a long-term follow-up study, part of which involved a short-term drug trial for the CMTD + ADHD group (Gadow et al. 2007; Pierre et al. 1999). Participants and their mothers were recruited from a variety of sources including a child psychiatry outpatient service, community clinics, schools, media advertisements, and parent support groups. Both ASD samples (with and without ADHD) were selected from a dataset collected for a retrospective chart review study (Gadow et al. 2006, 2008b, 2009). The research protocol for each study sample was approved by a university Institutional Review Board and appropriate measures were taken to protect patient (and rater) confidentiality. Procedures for recruiting, evaluating, diagnosing, and assessing each group are described in detail in the aforementioned publications.

Children in the two non-ASD samples were excluded from consideration for the study if they were dangerous to self or others, psychotic or had a seizure disorder, or had a major organic brain dysfunction, major medical illness, or ASD. Children were also excluded from the CMTD + ADHD group if their tics were so severe at intake that either the parent or child requested immediate intervention for tics. In all three samples, children were excluded if they were intellectually impaired (IQ < 70).

Control Samples

There were two community-based comparison groups, one each for teacher- and parent-completed ratings, all of whom were evaluated as part of a normative data study of the Child Symptom Inventory-4 (CSI-4; Gadow and Sprafkin 1986, 1994, 2002) and were living in the same communities as the referred samples. Teacher CSI-4 ratings were obtained for students in regular education classes (n = 464), a subset of whom who were receiving special education services (n = 60) (Nolan et al. 2001). In the current study we used only teacher ratings of boys who did not receive special education services, and whose teacher-ratings of ADHD symptoms did not meet criteria for ADHD (based on their CSI-4 screening cutoff scores described below) (n = 167). Parent CSI-4 ratings were obtained for students in regular education classes (n = 446), a subset of whom who were receiving special education services (n = 61). As was the case for teacher ratings, only parent ratings of boys who were not receiving special education services, and whose ratings did not meet criteria for ADHD (based on their CSI-4 screening cutoff scores), were included in the present study (n = 173).

Measures

Psychiatric Symptoms

The CSI-4 has both parent and teacher versions (Gadow and Sprafkin 1994, 2002). The items bear one-to-one correspondence with DSM-IV symptoms (i.e., high content validity) and can be scored in two ways: Symptom Count (number of symptoms criteria) and Symptom Severity (dimensional). Symptom count is a categorical score which uses scores of 0 (negative/sometimes) or 1 (often/very often). When summed, if the total symptom count is equal to or greater than the number of symptoms specified by DSM-IV as being necessary for a disorder, the individual is considered to meet criteria for the disorder. To determine symptom severity, items are scored (never = 0, sometimes = 1, often = 2, and very often = 3) and summed separately for each category. Individual symptom categories include ADHD: Inattentive type (ADHD:I); ADHD: Hyperactive-Impulsive type (ADHD:HI); ADHD: Combined type (ADHD:C); ODD (seven items), and CD (14 items). Numerous studies indicate that the CSI-4 demonstrates satisfactory psychometric properties in community-based normative, clinic-referred non-ASD, and ASD samples (Gadow and Sprafkin 2007).

Procedure

Clinic Samples

Procedures for recruiting, evaluating, diagnosing, and assessing each group are described in detail in prior publications (Gadow et al. 2007, 2006; Pierre et al. 1999). Briefly, prior to scheduling the clinic evaluation, mothers of potential patients were mailed a packet of materials including standardized behavior rating scales to be completed by parent and teacher, background information questionnaire, and permission for release of school records. In most cases (>90%), parent ratings were completed by the child’s mother.

Clinic evaluations included interviews with the boys and their caregivers, informal observation of parent–child interaction, and review of the aforementioned materials. In addition, the mothers of the boys in the two non-ASD samples were interviewed by trained evaluators using the parent version of the diagnostic interview for children and adolescents (DICA-P) (Reich 2000) for all but the first 11 boys. To be considered ADHD, boys in all three samples had to meet DSM-IIIR (American Psychiatric Association 1987) or DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994) criteria for ADHD and be above cutoff on at least one mother- and at least one teacher-completed ADHD behavior rating scale: Abbreviated Teacher/Parent Rating Scale (ATRS/APRS) (Conners 1973), the IOWA Conners Teacher’s Rating Scale (Loney and Milich 1982), the Conners (48-item) Parent Rating Scale (Goyette et al. 1978), the Mothers’ Objective Method for Subgrouping (MOMS) checklist (Loney 1984), and the parent and teacher versions of the CSI. Each child met ADHD clinical criteria in both school and home (the “and rule”).

The diagnosis of CMTD was based on an extensive battery of measures including the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS; Leckman et al. 1989), parent- and teacher-completed Global Tic Rating Scale (GTRS; Nolan et al. 1994), direct observation (simulated classroom, clinic office), and detailed family history. Almost all (94%) boys met research diagnostic criteria (Kurlan 1989) for Tourette syndrome, either definite (n = 30) or by history (n = 32). Four were diagnosed chronic motor tic disorder, definite. Tic severity as measured with the YGTSS was comparable to other studies of children with Tourette syndrome. At least two reliable examiners in different settings witnessed multiple different motor tics in all patients.

Using DSM-IV criteria, all ASD diagnoses were made by expert clinicians, whose diagnoses were determined to be valid in a related study (Sprafkin et al. 2002). In all cases, ASD diagnoses were based on (a) comprehensive developmental history of language and social development and inflexible or repetitive behaviors, (b) review of the parent- and teacher-completed CSI-4, which includes a validated ASD subscale (see “Measures”), and (c) prior evaluations by educators and clinicians. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al. 2000), administered by trained staff, was added to the assessment battery during the course of the study, and this information was used by the clinician to make the diagnosis in approximately 45% of the ASD cases. ADOS- and expert-diagnosed groups did not differ in IQ, demographic characteristics, or severity of any of the 12 DSM-IV ASD symptoms. The distribution of ASD diagnoses by subtype was as follows: autistic disorder (17%), Asperger’s disorder (38%), and PDD-NOS (45%). Children in the ASD sample were considered as ASD Only or as ASD + ADHD based on their CSI-4 Screening cutoff scores. Children who met criteria for any ADHD symptom category (ADHD:I, ADHD:HI, or ADHD:C) were placed in the ASD + ADHD group.

Community Samples

Teacher CSI-4 ratings were obtained for regular education classes in four public schools on Long Island, New York. Parent ratings were obtained from three elementary schools and seven pediatric practices on Long Island, New York. In the current study we used parent CSI-4 ratings of 168 boys, and teacher CSI-4 ratings of 173 boys. Mothers completed the Checklist for 90% of the boys. Details of the sampling procedure for parent ratings appear elsewhere (Gadow and Sprafkin 2002).

Statistical Analyses

The primary goal of this study was to compare individual symptoms of aggression across five different groups of boys with and without ADHD and ASD. The first step in data analysis was to compute descriptive statistics for all variables and identify outlying scores and extreme distributions. ANOVAs (continuous variables) and chi-square (categorical variables) analyses were used to investigate group differences in demographic characteristics.

A series of MANOVA analyses were conducted to investigate group differences in aggression symptoms for each informant separately. We first investigated differences among the three ADHD groups (ADHD Only, ASD + ADHD, and CMTD + ADHD) and the control samples, followed by a comparison of ASD boys with and without ADHD and controls. Tukey HSD tests (equal variances) and Dunnett’s C tests (unequal variances) were performed to localize differences between groups. Only statistically significant (p < .05) results are noted and Bonferroni corrected alphas are reported for multiple comparisons. Because demographic characteristics were only minimally correlated (all rs < .20) with severity of aggression symptoms, they were not treated as covariates in these analyses.

Results

Group Differences in Demographics

With the exception that average age of the ADHD Only group was lower than that of the parent-rated community sample (p < .001), the four clinic groups of boys (ASD + ADHD, CMTD + ADHD, ADHD Only, and ASD Only) and controls were similar in terms of age, IQ, living with at least one biological parent, and single-parent household (Table 1). With regard to ethnicity, a significantly larger percentage of boys in the CMTD + ADHD sample were of non-European–American ethnicity compared with the ASD + ADHD and ASD Only samples. Finally, the CMTD + ADHD group was of lower SES than the other three groups, whereas the ASD Only group had significantly higher SES than the ADHD Only sample.

How Do Boys With ADHD Differ From Controls?

Teachers (Table 2) and mothers rated all three groups of boys with ADHD as having more severe ODD behaviors than Controls, and this was true for all symptoms. These findings indicate a clear pattern of differentiation for boys with ADHD versus unaffected peers.

With regard to the CD behaviors, teacher ratings (Table 2) indicated the ASD + ADHD boys were more severe than Controls for two items (“lies”, “destroys property”). The ADHD Only group had higher ratings for three items (“starts fights”, “steal”, “destroys property”), whereas the CMTD + ADHD group was scored as having more severe lying, fighting, stealing, and using a weapon. However, when controlling for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni corrected alphas, the latter item is no longer significant.

Mothers’ ratings pointed to mixed differences between the ADHD groups and the Controls for CD behaviors. Specifically, they rated boys with ASD + ADHD as having more severe problems with “lying”, “bullying”, and “destroying property” as well as “cruelty to animals” and “to people”; the ADHD + CMTD group was rated as more severe than Controls on “cruelty to animals” and “preoccupied with sex”; and the ADHD Only group was also rated as higher than controls in “cruelty to people”. Whereas the ADHD Only group obtained more severe ratings for starts physical fights”, this result was no longer significant with the Bonferroni correction.

Collectively, these findings indicate that the three phenotypically similar groups of ADHD boys evidenced more severe ODD behaviors than Controls further supporting the contribution of ADHD to aggressive behavior and extending this relation to the level of individual behaviors. This relation was less clear for CD behaviors, several of which were uncommon in most samples.

How Do Boys With ASD + ADHD Differ From the Other Boys With ADHD?

Maternal ratings of ODD symptoms indicated that the ASD + ADHD boys were comparable to the ADHD Only and ADHD + CMTD groups. Teachers, however, rated the ASD + ADHD boys more severely than the other two groups for half of the ODD behaviors, particularly symptoms that required a lower level of social sophistication to enact them (e.g., “loses temper” versus “tries to get even”; Table 2). As for CD behaviors, results were mixed; however, both mothers and teachers rated the ASD + ADHD boys similarly to the other ADHD groups with one exception (teacher ratings of stealing). However, a close examination of the data reveals instances of CD behaviors were few and far in between for all groups, making the clinical significance of any results with regard to the CD behaviors, minimal. Collectively, these findings suggest that the clinical features of ASD appear to alter the ODD (but not CD) phenotype at least as it is currently defined in DSM-IV and evaluated with teacher ratings.

How Do ASD Boys Without ADHD Differ From Controls?

With the exception of “annoys others” (parent and teachers ratings) and “tries to get even” (parent ratings), both informants considered the ASD Only boys as having more severe ODD symptoms than Controls suggesting the possibility that certain ODD behaviors may be linked to the ASD phenotype (Table 3). The only CD behavior for which the ASD Only group was rated more severe than Controls was mother-rated “cruel to people” (F = 7.1, p < .001).

How Do ASD Boys With and Without ADHD Differ From Each Other?

For most ODD behaviors, the ASD + ADHD group was considered to be more severe than the ASD Only group, supporting the notion that co-morbid ADHD contributes to the severity of ODD in boys with ASD (Table 3). The exceptions were on teacher-rated behavior (“loses temper”) and three mother-rated behaviors (“easily annoyed”, “angry and resentful”, “tries to get even”).

There were few group differences for CD symptoms. Both teachers and mothers rated the ASD + ADHD group as lying more often than the ASD Only group (F = 7.2, p < .001; F = 6.3, p < .002, respectively). Mothers also rated the ASD + ADHD boys as more likely to destroy objects than the ASD Only group (F = 9.0, p < .000).

Discussion

In general, the findings of the present study provide additional support for the association of ADHD with ODD and CD behaviors in diverse groups of children including youngsters with ASD. Moreover, they also provide new insight into the diversity of these relations when examined at the molecular level. Specifically, a close examination of specific symptoms revealed significant differences between the two ASD groups: both mothers and teachers rated boys with ASD + ADHD as having more severe ODD behaviors compared with the ASD Only group, which is in accordance with previous research (Gadow et al. 2006). Furthermore, boys with ASD Only (i.e., without ADHD) and Controls were rated similarly for ODD behaviors that appear to require more social cognition (i.e., “deliberately annoys others”, “blames others for own mistakes”). These findings suggest that although co-morbid ADHD appears to be a risk factor for ODD behaviors in boys with ASD, the social cognition deficits associated with the ASD diathesis may be “protective” for certain types of ODD behaviors. Collectively, these results are consistent with the notion that co-morbid neurobehavioral syndromes (e.g., ASD) may alter the generally accepted clinical features of other co-morbid disorders such as ODD. Similarly, the comparison of the three ADHD diagnostic groups also revealed the impact of co-morbidity on clinical phenotypes. Specifically, teachers (but not mothers), rated the ASD + ADHD group more severely than the other ADHD groups for four ODD symptoms that appear to require less social cognition (“loses temper”, “defies what is told to do”, “touchy or easily annoyed”, and “angry and resentful”). They did not, however, indicate that these boys more frequently engaged in “argues with adults”, “deliberately annoys others”, “blames others for own mistakes”, and “tries to get even”. This distinction falls in line with a wealth of investigations published over the past two decades (e.g., Rehfeldt et al. 2007; Serra et al. 2002) further demonstrating impairments in reciprocal social interaction and communication (i.e., activities that require intact social cognition abilities) as core features of ASD. It also strengthens Werner et al.’s (2006) suggestion that acts of aggression may differ according to the degree of social sophistication required to carry them out.

We predicted that given the importance of environmental variables in child disruptive behavior, group differences will vary as a function of mother versus teacher report (e.g., Drabick et al. 2007; Hudziak et al. 2005), and this was found to be at least partially true. While we hasten to note that the present study was not designed to be a direct test of this hypothesis (i.e., we did not statistically test for informant differences), the pattern of significant post-hoc comparisons and magnitude of effect sizes suggest considerable discordance between mother and teacher perceptions of ODD behaviors. Teacher ratings appeared to be more sensitive in differentiating cognitive demands implicit in certain disruptive behaviors (i.e., requiring social cognition abilities), which is consistent with the findings of numerous studies (e.g., Drabick et al. 2007; Hudziak et al. 2005; Mitsis et al. 2000). For example, Drabick et al. (2007) demonstrated that teacher-reported ODD better differentiated ODD symptom groups than did mother ratings. Others showed teachers’ reports were more strongly linked to impairment criteria than mother- or child-reported ODD (Hart et al. 1994). Collectively, these results point to the importance of using teacher ratings in addition to traditionally-obtained parent reports, as the former seem to tap into a differentiated understanding of co-morbidity and risk factors (Drabick et al. 2004, 2006). As Kraemer et al. (2003) suggest, such cross-informant discordance implies, among other influences, the impact of the context in which the informant observes the child (also see van der Oord et al. 2006) and the perspective and biases of the informant (e.g., Youngstrom et al. 2000).

Limitations and Future Directions

Generalization of our results is limited to samples with similar demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, percent of ethnic minority, SES). For example, disruptive behavior in girls may evidence a different pattern of group differences. Our assessment of ODD and CD was limited to rating scale data. Other methods of assessment (e.g., direct observations) need to be included in future studies. Although differences between our ASD and non-ASD samples were seemingly consistent with the clinical features of ASD, we did not specifically examine relations between social cognitions and specific symptoms of disruptive behaviors to determine if they are in fact interrelated. Although we excluded boys with IQs < 70 from all samples and did not find evidence of an association between severity of ODD and CD and intellectual ability, additional research is necessary to rule out an association between IQ, social cognition, and obtained group differences in this range of intellectual ability.

Although our results must be considered preliminary, they do point to the importance of considering a more fine-grained approach when formulating clinical phenotypes, particularly when investigating phenotypic variation (e.g., ODD, CD) across a range of possible co-morbidities (e.g., ASD + ADHD, CMTD + ADHD). A related strategy is becoming more widely embraced in molecular biology (e.g., endophenotypes, subphenotypes) (e.g., Fisch 2008; Kendler 2006; Liu et al. 2008; Shao et al. 2003). Moreover, this study does not resolve the conundrum of whether it is better to characterize behavioral syndromes (e.g., ODD, CD) in children with ASD with symptom characterizations that reflect their social cognition deficits or to use symptom characterizations that apply equally to a wide range of co-morbid neurobehavioral syndromes. Put somewhat differently, is it more scientifically or clinically useful to define ODD in terms of behavioral features that are unlikely to be influenced by co-occurring conditions (e.g., ASD, CMTD) or embrace these differences and acknowledge the existence of a unique variant of ODD in children with ASD? It seems that a necessary step on the way to answering this and many related questions is coming closer to a consensus of nosological criteria for defining behavioral syndromes.

References

Abrahams, B. S., & Geschwind, D. H. (2008). Advances in autism genetics: On the threshold of a new neurobiology. National Review, 9, 341–355. doi:10.1038/nrg2346.

American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, (3rd ed.), revised (DSM-III-R). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. (DSM-IV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Belmonte, M. K., Cook, E. H., Jr, Anderson, G. M., Rubenstein, J. L. R., Greenough, W. T., Beckel-Mitchener, A., et al. (2004). Autism as a disorder of neural information processing: Directions for research and targets for therapy. Molecular Psychiatry, 9, 646–663.

Biederman, J., Faraone, S., Milberger, S., Curtis, S., Chen, L., Marrs, A., et al. (1996). Predictors of persistence and remission of ADHD into adolescence: Results from a 4-year prospective follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 343–351.

Bohman, M. (1996). Predisposition to criminality: Swedish adoption studies in retrospect. In G. R. Bock & J. A. Goode (Eds.), Genetics of criminal and antisocial behavior (Ciba Foundation Symposium194) (pp. 99–114). Chichester: Wiley.

Brame, B., Nagin, D. S., & Tremblay, R. E. (2001). Developmental trajectories of physical aggression from school entry to late adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 42, 503–512. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00744.

Broidy, L. M., Nagin, D. S., Tremblay, R. E., Bates, J. E., Brame, B., Dodge, K. A., et al. (2003). Developmental trajectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: A six-site, cross-national study. Developmental Psychology, 39, 222–245. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.222.

Budman, C. L. (2006). Treatment of aggression in Tourette syndrome. In J. T. Walkup, J. W. Mink, & P. J. Hollenbeck (Eds.), Advances in neurology: Tourette syndrome (Vol. 99, pp. 222–226). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publishers.

Budman, C. L., Rockmore, L., Stokes, J., & Sossin, M. (2003). Clinical phenomenology of episodic rage in children with Tourette syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55, 59–65. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00584-6.

Cadoret, R. J., Yates, W. R., Troughton, E., Woodworth, G., & Stewart, M. A. (1995). Genetic-environmental interaction in the genesis of aggressivity and conduct disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 916–924.

Capaldi, D. M. (1992). Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: II. A 2-year follow-up at grade 8. Development and Psychopathology, 4, 125–144. doi:10.1017/S0954579400005605.

Charman, T., Carroll, F., & Sturge, C. (2001). Theory of mind, executive function and social competence in boys with ADHD. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 6, 31–49.

Comings, D. E., Wu, S., Chiu, C., Ring, R. H., Gade, R., Ahn, C., et al. (1996). Polygenetic inheritance of Tourette syndrome, stuttering, attention deficit hyperactivity, conduct, and oppositional defiant disorder. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 67B, 264–288.

Conners, C. K. (1973). Rating scales for use in drug studies with children (Special issue: Pharmacotherapy of children). Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 9(Spec Issue), 24–84.

Connor, D. E., Edwards, G., Fletcher, K. E., Baird, J., Barkley, R. A., & Steingard, R. J. (2003). Correlates of comorbid psychopathology in children with ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 193–200. doi:10.1097/00004583-200302000-00013.

Drabick, D. A. G., Gadow, K. D., Carlson, G. A., & Bromer, E. J. (2004). ODD and ADHD symptoms in Ukranian children: external validators and comorbidity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 735–743. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000120019.48166.1e.

Drabick, D. A. G., Gadow, K. D., & Loney, J. (2007). Source-specific oppositional defiant disorder: Comorbidity and risk factors in referred elementary schoolboys. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 92–101. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000242245.00174.90.

Drabick, D. A. G., Gadow, K. D., & Sprafkin, J. (2006). Co-occurrence of conduct disorder and depression in a clinic-based sample of boys with ADHD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 47, 766–774. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01625.x.

Fisch, G. S. (2008). Syndromes and epistemology II: Is autism a polygenic disorder? American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A, 146A, 2203–2212. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.32438.

Frazier, J. A., Biederman, J., Bellordre, C. A., Garfield, S. B., Geller, D. A., Coffey, B. J., et al. (2001). Should the diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder be considered in children with pervasive developmental disorder? Journal of Attention Disorders, 4, 203–211. doi:10.1177/108705470100400402.

Gadow, K. D., & DeVincent, C. J. (2005). Clinical significance of tics and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children with pervasive developmental disorder. Journal of Child Neurology, 20, 481–488.

Gadow, K. D., DeVincent, C. J., & Drabick, D. A. G. (2008a). Oppositional defiant disorder as a clinical phenotype in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1302–1310. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0516-8.

Gadow, K. D., DeVincent, C. J., & Pomeroy, J. (2006). ADHD symptom subtypes in children with pervasive developmental disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 271–283. doi:10.1007/s10803-005-0060-3.

Gadow, K. D., DeVincent, C., & Schneider, J. (2008b). Predictors of psychiatric symptoms in children with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1710–1720. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0556-8.

Gadow, K. D., DeVincent, C. J., & Schneider, J. (2009). Comparative study of children with ADHD Only, ADHD + autism spectrum disorder, and ADHD + chronic multiple tic disorder. Journal of Attention Disorders (in press).

Gadow, K. D., & Sprafkin, J. (1986). Stony Brook child psychiatric checklist-3. Stony Brook: Department of Psychiatry, State University of New York.

Gadow, K. D., & Sprafkin, J. (1994). Child symptom inventories manual. Stony Brook, NY: Checkmate Plus.

Gadow, K. D., & Sprafkin, J. (2002). Child symptom inventory-4 screening and norms manual. Stony Brook, NY: Checkmate Plus.

Gadow, K. D., & Sprafkin, J. (2007). The symptom inventories: An annotated bibliography [On-line]. Available: www.checkmateplus.com.

Gadow, K. D., Sverd, J., Nolan, E. E., Sprafkin, J., & Schneider, J. (2007). Immediate-release methylphenidate for ADHD in children with comorbid chronic multiple tic disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 840–848. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e31805c0860.

Goldstein, S., & Schwebach, A. (2004). The comorbidity of pervasive developmental disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Results of a retrospective chart review. Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 329–339. doi:10.1023/B:JADD.0000029554.46570.68.

Goyette, C. H., Conners, C. K., & Ulrich, R. F. (1978). Normative data on revised Conners parent and teacher rating scales. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 6, 221–236. doi:10.1007/BF00919127.

Grados, M. A., Mathews, C. A., & Tourette Syndrome Association International Consortium for Genetics. (2008). Latent class analysis of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome using comorbidities: Clinical and genetic implications. Biological Psychiatry, 64, 219–225. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.01.019.

Hart, E. L., Lahey, B. B., Loeber, R., & Hanson, K. S. (1994). Criterion validity of informants in the diagnosis of disruptive behavior disorders in children: A preliminary study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 410–414. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.62.2.410.

Hollingshead, A. B. (1975). Four factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Department of Sociology, Yale University.

Hudziak, J. J., Derks, E. M., Althoff, R. R., Copeland, W., & Boomsma, D. I. (2005). The genetic and environmental contributions to oppositional defiant behavior: A multi-informant twin study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44, 907–914. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000169011.73912.27.

Hughes, D. M., Cunningham, M. M., & Libretto, S. E. (2002). Risperidone in children and adolescents with autistic disorder and aggressive behavior. British Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 48, 113–122.

Jensen, P. S., Martin, D., & Cantwell, D. P. (1997). Comorbidity in ADHD: Implications for research, practice, and DSM-V. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 1065–1079.

Kendler, K. S. (2006). Reflections on the relationship between psychiatric genetics and psychiatric nosology. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 1138–1146. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.7.1138.

Kraemer, H., Maeselle, J. R., Ablow, J. C., Essex, M. J., Boyce, W. T., & Kupfer, D. J. (2003). A new approach to integrating data from multiple informants in psychiatric assessment and research: Mixing and matching contexts and perspectives. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1566–1577. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1566.

Kurlan, R. (1989). Tourette’s syndrome: Current concepts. Neurology, 39, 1625–1630.

Leckman, J. F., Riddle, M. A., Hardin, M. T., Ort, S. I., Swartz, K. L., Stevenson, J., et al. (1989). The Yale global tic severity scale: Initial testing of a clinic-rated scale of tic severity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 28, 566–573. doi:10.1097/00004583-198907000-00015.

Liu, X.-Q., Paterson, A. D., Szatmari, P., & The Autism Genome Project Consortium. (2008). Genome-wide linkage analyses of quantitative and categorical autism subphenotypes. Biological Psychiatry, 64, 561–570. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.023.

Loney, J. (1984). A short parent scale for subgrouping childhood hyperactivity and aggression. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Toronto.

Loney, J., & Milich, R. (1982). Hyperactivity inattention, and aggression in clinical practice. In M. Wolraich & D. K. Routh (Eds.), Advances in developmental and behavioral pediatrics (Vol. 3, pp. 113–147). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook, E. H., Jr, Leventhal, B. L., DiLavore, P. C., et al. (2000). The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 205–223. doi:10.1023/A:1005592401947.

Loth, E., Gomez, J. C., & Happe, F. (2008). Event schemas in autism spectrum disorders: The role of theory of mind and weak central coherence. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 449–463. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0412-2.

Mitsis, E. M., McKay, K. E., Schulz, K. P., Newcorn, J. H., & Halperin, J. M. (2000). Parent-teacher concordance for DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a clinic-referred sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 308–313. doi:10.1097/00004583-200003000-00012.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.674.

Montes, G., & Halterman, J. S. (2007). Bullying among children with autism and the influence of comorbidity with ADHD: A population-based study. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 7, 253–257. doi:10.1016/j.ambp.2007.02.003.

Nolan, E. E., Gadow, K. D., & Sprafkin, J. (2001). Teacher reports of DSM-IV ADHD, ODD, and CD symptoms in schoolchildren. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 241–249. doi:10.1097/00004583-200102000-00020.

Nolan, E. E., Gadow, K. D., & Sverd, J. (1994). Observations and ratings of tics in school settings. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 22, 579–593. doi:10.1007/BF02168939.

Patterson, G. R., De Baryshe, B. D., & Ramsey, E. (1989). A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. The American Psychologist, 44, 329–335. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.329.

Perner, J., Kain, W., & Barchfeld, P. (2002). Executive control and higher order theory of in children at risk of ADHD. Infant and Child Development, 11, 141–158. doi:10.1002/icd.302.

Pierre, C. B., Nolan, E. E., Gadow, K. D., Sverd, J., & Sprafkin, J. (1999). Comparison of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder with and without comorbid tic disorder. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 20, 170–176.

Rehfeldt, R. A., Dillen, J. E., Ziomek, M. M., & Kowalchuk, R. K. (2007). Assessing relational learning deficits in perspective-taking in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. The Psychological Record, 57, 23–47.

Reich, W. (2000). Diagnostic interview for children and adolescents (DICA). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 59–66. doi:10.1097/00004583-200001000-00017.

Ronald, A., Happer, F., & Plomin, R. (2005). The genetic relationship between individual differences in social and nonsocial behaviors characteristic of autism. Developmental Science, 8, 444–458. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00433.x.

Rutter, M., Silberg, J., O’Connor, T., & Simonoff, E. (1999). Genetics and child psychiatry: II Empirical research findings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 40, 19–55. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00423.

Serra, M., Loth, F. L., van Greet, P. L. C., Hurkens, E., & Minderaa, R. B. (2002). Theory of mind in children with ‘lesser variants’ of autism: A longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 43, 885–900. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00104.

Shao, Y., Cuccaro, M. L., Hauser, E. R., Raiford, K. L., Menold, M. M., Wolpert, C. M., et al. (2003). Fine mapping of autistic disorder to chromosome 15q11-q13 by use of phenotypic subtypes. American Journal of Human Genetics, 72, 539–548. doi:10.1086/367846.

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Winton, A. S. W., Fisher, B. C., Wahler, R. G., McAleavey, K., et al. (2006). Mindful parenting decreases aggression, noncompliance, and self-injury in children with autism. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 14, 169–177. doi:10.1177/10634266060140030401.

Sprafkin, J., Volpe, R. J., Gadow, K. D., Nolan, E. E., & Kelly, K. (2002). A DSM-IV-referenced screening instrument for preschool children: The early childhood inventory-4. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 604–612. doi:10.1097/00004583-200205000-00018.

Szatmari, P., Maziade, M., Zwaigenbaum, L., Merette, C., Roy, M.-A., Joober, R., et al. (2007). Informative phenotypes for genetic studies of psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 144B, 581–588. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.30426.

Tremblay, R. E. (2000). The development of aggressive behavior during childhood: What have we learned in the past century? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 24, 129–141. doi:10.1080/016502500383232.

van der Oord, S., Prins, P. J. M., & Oosterlaan, J. (2006). The association between parenting stress, depressed mood and informant agreement in ADHD and ODD. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1585–1595. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.11.011.

Werner, R. S., Cassidy, K. W., & Juliano, M. (2006). The role of social-cognitive abilities in preschoolers’ aggressive behavior. The British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 24, 775–799. doi:10.1348/026151005X78799.

Youngstrom, E., Loeber, R., & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (2000). Patterns and correlates of agreement between parent, teacher, and male adolescent ratings of externalizing and internalizing problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 1038–1050. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.1038.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Dr. John Pomeroy, Dr. Joyce Sprafkin, and Dr. Jeff Sverd for their role in the diagnostic evaluations. This study was supported, in part, by grants awarded to Dr. Gadow from the Tourette Syndrome Association, Inc., National Institute of Mental Health (MH 45358), and the Matt and Debra Cody Center for Autism and Developmental Disorders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guttmann-Steinmetz, S., Gadow, K.D. & DeVincent, C.J. Oppositional Defiant and Conduct Disorder Behaviors in Boys With Autism Spectrum Disorder With and Without Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Versus Several Comparison Samples. J Autism Dev Disord 39, 976–985 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0706-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0706-7