The present paper consists of two parts. In the first part, eleven high-functioning adults with pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) participated and were videotaped with a concealed camera while having an initial conversation with a typically developing stranger. Analyses revealed some significant differences with regard to the dyad members’ overt behaviours. Contrary to our main hypothesis, analyses of the covert behaviour revealed that the participants with PDD did not differ from the typically developing participants in the ability to infer the thoughts and feelings of their interaction partner. The second part indicated that the inference ability of both groups was independent of the dyad members’ behavioural characteristics and the content of the dyad members’ thoughts and feelings. Issues addressed in this paper include the relation of scriptal knowledge to social functioning, and the advantage participants with PDD take from more structured interactions compared with less structured interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The past few years there has been great interest in developing tasks which are able to measure the social functioning of normally intelligent subjects with autism in contexts that approximate closely the real social world (Baron-Cohen, Jolliffe, Mortimore, & Robertson, 1997; Kaland et al., 2002; Kleinman, Marciano, & Ault, 2001). A validated design that encounters these demands is the empathic accuracy design of Ickes and colleagues (Ickes, 1997; Ickes, Bissonnette, Garcia, & Stinson, 1990; Marangoni, Garcia, Ickes, & Teng, 1995). Empathic accuracy is the degree to which someone is able to accurately infer the specific content of another person’s thoughts and feelings and, in addition, is the product of a specific conversation between two or more interacting persons (Ickes et al., 1990). As described by Ickes (1997), the most unequivocal way to measure empathic accuracy is by rating the similarity between the content of the target’s actual thought or feeling and the content of the perceiver’s inference. Over the years, the empathic accuracy design has proved to be a reliable and valid method to measure peoples’ inference abilities (Ickes, Stinson, Bissonnette, & Garcia, 1990; Simpson, Ickes, & Blackstone, 1995).

In two recent studies (Ponnet, Roeyers, Buysse, De Clercq, & Van der Heyden, 2004; Roeyers, Buysse, Ponnet, & Pichal, 2001), we tested adults with a pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) and typically developing adults using a naturalistic Empathic Accuracy Task. In this task, each participant attempted to infer aspects of a target person’s actual subjective experience, while viewing a videotape of the target person in a naturally occurring conversation with a stranger. The procedure used in the studies was the standard stimulus paradigm, in which individual participants each viewed the same set of two videotaped interactions between strangers. In both studies, the Empathic Accuracy Task was able to distinguish clearly between the group with PDD and the control group, although a significant difference between both groups was only found on one of the two empathic accuracy videotapes.

The two studies indicate that the above-mentioned standard stimulus empathic accuracy design is a promising and valuable method to study the mind-reading abilities of adults with PDD. We consider the empathic accuracy design to be more naturalistic than static mind-reading tasks since it allows participants to make inferences about other people’s thoughts and feelings on the basis of verbal and non-verbal cues, whereas in the static mind-reading tasks participants have to rely on either verbal or non-verbal cues. In contrast with common paper and pencil mind-reading tasks, the empathic accuracy task forces people to infer “on-line” the thoughts and feelings of interacting persons, which reduces the possibility that participants successfully pass the task without a genuine social-cognitive understanding of the situation.

However, it should be noticed that the real social world is still more complex than the standard stimulus design of the Empathic Accuracy Task. In the standard stimulus design, participants serve only as perceivers, not as targets, which is different from any social dyadic interaction where participants have to infer the thoughts and feelings of their interaction partner and vice versa. This lack of bidirectional influences induces the authors to use an alternative empathic accuracy design, the dyadic interaction design, in which each participant becomes an active and interacting member, instead of being a passive observer. The empathic accuracy, also defined as the degree to which the participant’s inference matches the target’s subjective experience, is therefore, in a way, best characterised as the emergent product of social interaction processes that occur at the level of the dyad (Ickes, 1997; Ickes et al., 1990).

Since the dyadic interaction design requires various social skills, which are at the core of the PDD diagnosis, the social situation of the dyadic interaction design can be considered as more complex than that of the standard stimulus design. In order to assure that the PDD participants possess a minimum of the acquired social skills, we therefore worked with a sample of high-functioning subjects with PDD of the Roeyers et al.’s study (2001). Although there were significant between-group differences found in the Empathic Accuracy Task of Roeyers et al. (2001), some participants with PDD performed as well as participants without PDD. This “upper-class” of PDD subjects (with empathic accuracy scores above the mean) was invited to participate in the present study.

The present investigation consists of two parts. In the first part, eleven adults with PDD participated in a laboratory study in which they were videotaped with a concealed camera while having an initial conversation with a typically developing stranger. The hypotheses and research questions of the first part are based on previous studies with the empathic accuracy design as well as other studies with adults with PDD. A prior study of Stinson and Ickes (1992) with typically developing adults revealed that the empathic accuracy of male strangers was strongly dependent on the level of interactional involvement (in case verbalisations, gazes, positive affect, gestures and interpersonal distance) in their immediate interaction. Stinson and Ickes (1992, p. 795) reason that this is not surprising because the strangers’ immediate interaction provided them with their only source of information about each other. In the present study, we assume differences between the adults with PDD and the control adults with regard to their behavioural characteristics, and we expect reciprocity between the behaviours of the dyad members. We further assume that the association between the behavioural characteristics and the empathic accuracy scores will be different for both groups. We strengthen the latter expectation with a recent study of Koning and Maggil-Evans (2001) who found that subjects with PDD made use of facial cues as frequently as typically developing controls, but subjects with PDD used facial cues more often than other cues (such as tone of voice) for inferring emotions. Koning and Maggil-Evans (2001, p. 32) further noticed that “the difficulties of the subjects with PDD to infer the affective state of others may become only apparent when dealing with the simultaneous presentation of facial, vocal, body and situational cues”. Based on our previous studies with the empathic accuracy design (Ponnet et al., 2004; Roeyers et al., 2001), we expect within-dyad differences in empathic accuracy. In addition, we expect different patterns between the dyad members with regard to the focus/foci or “theme(s)” of the original thought/feeling entries and with regard to the empathic accuracy for thought/feeling entries circling around a specific focus or theme.

The procedure used was the dyadic interaction design (Ickes et al., 1990) through which we were able to study both the overt behaviour of the interacting dyad members, and the covered thoughts and feelings of the participants. First, the dyadic interaction paradigm permits the study of the overt behavioural characteristics of the dyad members during their conversation. It is common knowledge that people with PDD often exhibit socially and emotionally inappropriate behaviours, but the way in which they specifically differ from typically developing control subjects is not always clear and probably varies from person to person (see Zager, 1999). The uniqueness of the present observational study lies in the combination of our naturalistic design and the procedure that is used to code the behaviours: (a) both the participant with PDD as well as the participant without PDD were unaware that they were being videotaped, so that the naturalistic character of the recorded interaction was guaranteed, and (b) instead of using a rating procedure, the behaviours of each adult were thoroughly (second-to-second or even slower) observed and coded, using a validated computer programme.

Second, in the dyadic interaction paradigm the participants have to make a written record of all their unexpressed thoughts and feelings on a standardised coding form, by which we were able to explore the nature of the dyad members’ original thought/feeling entries. This permitted us to attribute the different patterns in the dyad members’ empathic accuracy. We assessed how difficult it was to infer the specific content of each thought/feeling entry for each dyad member and how concrete or abstract the content of each thought/feeling entry was. Furthermore, we examined the thematic topic of each dyad member’s actual thought/feeling entries. Thereafter, we calculated the global empathic accuracy for each dyad member. According to the content of each thought/feeling entry, the empathic accuracy scores of each participant could be computed for all the thought/feeling entries classified as highly easy/concrete and for all the thought/feeling entries classified as highly difficult/abstract. Furthermore, we worked out the empathic accuracy scores of each participant for all the thought/feeling entries belonging to the different topics of the original thoughts and feelings.

Part 1

Method

Participants

Two groups of normally intelligent adults participated in this study, i.e. 11 subjects with PDD and a control group of 11 typically developing subjects. Male/female ratio (9/2) was similar in both groups. The subjects of the clinical group were drawn from a sample of individuals who participated in a research project two years ago at our laboratory (Roeyers et al., 2001). More specifically, 15 subjects with PDD with the highest performance on the Empathic Accuracy Task of Roeyers et al. (2001) were selected and invited for a follow-up task. Four of them refused to participate. The eleven remaining participants had all been diagnosed by a multidisciplinary team of experienced clinicians and fulfilled established DSM-IV criteria for autism, Asperger syndrome or PDD-NOS (APA, 1994). The comparison group was recruited by personal contact.

The adults with PDD were matched on a one-to-one basis with the control adults on sex, chronological age, level of education and main interests (e.g. computer and internet, music, cars). This results in 11 dyads. Given the bidirectional nature of the communication and the empathic accuracy design (see above), the dyad is used as unit of analyses and within-dyad analyses will be used.

All participants with PDD had IQ scores in the normal range as indicated by their records of previous IQ testing using the full Wechsler Scale of Intelligence. The control participants were given the shortened WAIS version, comprising Block Design, Vocabulary, Arithmetic, and Picture Arrangement. Two participants of the control group refused the intelligence testing, but on the basis of their study or professional level it can be taken for granted that they are of normal intelligence.

The IQ scores for the participants with PDD were: Total IQ, M = 121.44, SD = 12.49, Verbal IQ, M = 117.67, SD = 10.57, and Performance IQ, M = 122.56, SD = 12.97. The estimated IQ scores for the control participants were: Total IQ, M = 124.78, SD = 12.26, Verbal IQ, M = 121.67, SD = 11.25, and Performance IQ, M = 121.78, SD = 13.06. Paired t-tests revealed no significant within-dyad differences for Total IQ, t(8) = .46, for Verbal IQ, t(8) = .71., and for Performance IQ, t(8) = −.11. Furthermore, a paired t-test revealed no significant differences between the mean chronological ages of the participants with PDD (M = 24.60, SD = 8.11) and the mean chronological ages of the control participants (M = 24.53, SD = 7.89), t(10) = −.10.

Setting and Equipment

The observation room where the dyad members’ interactions were recorded was furnished with three armchairs (one for the experimenter and one for each participant), a coffee table and two small tables placed before a one-way screen. The two tables were decorated with some plants, in support of covering the one-way screen. Behind the one-way screen was a control room used to house a camera and audio equipment. The video camera focused on the area of the coffee table and the two armchairs of the interaction partners and was connected with two identical VCRs, by which the interaction was directly recorded on two analogue videotapes. Nearby the observation room, two offices were equipped with an identical 30 inch colour TV monitor and a VCR.

Procedure

The procedures used were based on those developed by Ickes and colleagues (Ickes et al., 1990; Simpson et al., 1995; Stinson & Ickes, 1992). The dyad members, previously unacquainted to each other, were scheduled to come to the research centre at the same time. They were asked to participate in a study on “people’s perceptions about others during different situations”. They were told in advance that they would meet another person, but they were kept unaware that they were to be videotaped. Ethical permission was sought and granted for this study. Furthermore, the typically developing dyad member was not informed that his/her interaction partner had a PDD diagnosis. Likewise, the dyad member with PDD was kept unaware whether or not his/her interaction partner had any kind of diagnosis.

Phase 1: Collection of the Videotape Data

Once they arrived at the research centre, both participants were brought to different waiting rooms so that they would not meet and interact before the experiment began. When they were brought together, the research assistant told the participants they had to fill in some inquiry forms. However, when the research assistant reached for the inquiry forms, he “discovered” that some of the copies were not well printed. In order to get some proper copies, the experimenter left the room. Promising to return in a few minutes, he suggested both participants to seek acquaintance with each other during his absence. At this point, a second research assistant activated the concealed camera. After approximately 8 minutes, the first research assistant returned and partly debriefed the participants. The participants were told they had been unobtrusively videotaped in order to study the spontaneous occurring interaction that takes place between two strangers. The participants were then asked whether their tape could be used as data. It was made clear that if either of them did not want the videotape used for any reason, they could erase it themselves immediately. None of the participants refused the tape to be released and each of them signed a consent form. Thereafter, both adults were asked to participate in a second phase of the study.

In approximately two third of the cases, the conversation was started by the control adult. Examples of utterances given by the adults with PDD were: “Where do you come from?”, “What is your name?”, “What are you studying?”, “It’s the second time that I’m participating in a research study”. Examples of utterances given by the control adults were: “How do you come to be here?”, “Where do you come from?”, “Do you have a job?”, “Phew, it’s very hot outside”.

Phase 2: Collection of the Thought/Feeling Data

In the second phase, the participants were brought to the above-mentioned separate offices. Both participants were asked to view their videotape and to make a written record of all the unexpressed thoughts and feelings they remembered having had during the interaction period that they were left alone. Following the procedures of previous studies (e.g. Buysse & Ickes, 1999; Ickes et al., 1990), the research assistant instructed them to stop the videotape at each point during the interaction when they remembered having had a specific thought or feeling. At each of those stops, the participants were asked to write down on a standardised thought/feeling coding form (a) the time when the thought or feeling occurred (as displayed by a digital clock on the under-right corner of the videotape), (b) whether the entry was a thought or a feeling, and (c) the specific content of the thought/feeling entry.

Furthermore, the research assistant explicitly encouraged the participants to report all the thoughts and feelings they remembered having had as accurately and honestly as possible, and assured the participants that their unexpressed thoughts and feelings would never be shown to their interaction partner. In addition, the research assistant asked the participants to report only those thoughts and feelings they distinctly remembered having had during the interaction period and not to report any new thoughts and feelings that occurred to them while they were viewing the videotape. No restriction of time was given. Considerable evidence for the construct validity of this method of thought/feeling assessment has been established (see Ickes, Robertson, Tooke, & Teng, 1986).

Sample thought/feeling entries reported by the adults with PDD were: “What do I have to say?”, “I feel a bit uncomfortable”, “It is quiet here”, “This situation looks suspicious to me”, “Where does he come from?”. Sample entries reported by the control adults were: “It’s taken too long here for me”, “What can I say?”, “Perhaps she knows something about the coming experiment”, “His accent is funny”, “Where does he come from?”, “Ouch, we both fell silent”, “I hope the experimenter will arrive soon”, “Strange shoes he’s wearing”.

Phase 3: Collection of the Empathic Accuracy Data

After the collection of all the unexpressed thought/feeling entries, the research assistant requested the participants to view their videotape a second time. This time, the research assistant paused the videotape at precisely those moments during which their interaction partner had reported having had a specific thought or feeling. The participants’ task was to make inferences about the content of their partner’s thought/feeling entries. More specifically, the participants were asked to report (a) whether the interaction partner’s entry was a thought or a feeling, and (b) the specific content of the thought/feeling entry. No restriction of time was given. When this task was fulfilled, each participant was debriefed more completely and was given a small monetary reward for his or her participation.

Measures

Behavioural Measures

The verbalisations, gazing and stimulatory gestures of the participants with PDD and those of the control participants were recorded from videotape by using “The Observer Video-Pro Analysis System” (Noldus, 1991; Noldus, Trienes, Hendriksen, Jansen, & Jansen, 2000). This system reads time codes directly from videotape, which allows accurate event timing at slower playback speed.

Verbalisations are defined as all meaningful words, utterances, questions, remarks and requests. Vocalisations such as sounds which do not form words, sneezing or coughing were excluded. Gazing is defined as “looking at the face of the other person”. Stimulatory gestures were all hand movements that had to do with touching some object, body part of the self or body part of the other person.

The codings were performed by one rater. To prevent bias, each of the two videotaped interactants was rated independently for each behaviour (verbalisation, gazing and stimulatory gestures), so that each videotape was viewed six times (i.e. 2 interactants × 3 behaviours) by the rater. The behavioural coding was very time consuming, because the rater scored each behaviour at a slower playback speed (1/2 normal) and made multiple passes through the videotape if necessary. A second rater coded a randomly chosen videotape, in order to validate the judgement of the first coder. Consistent with the first rater and using the same procedure, this videotape was viewed six times by the second rater. The degree of inter-rater concordance (based on frequency and sequence) was calculated for each behaviour, by tallying the frequency of agreements and disagreements between the observations of both coders. The tolerance window, which defines how accurate the timing of a record must be to be considered a match or not, was set on 2 seconds. This means that the programme links the events in the two observations and searches 2 seconds around a time code. These links may result in an error (disagreement) or a match. All kappa values were satisfactory (between .76 and .84).

For each behavioural characteristic of each participant, we calculated (a) the total duration, (b) the frequency, and (c) the mean duration of each specific behaviour. The mean duration of each specific behaviour was derived by dividing for each perceiver the duration of the specific behaviour by the frequency of that behaviour. In the present paper, the mean duration of each behavioural characteristic will be presented in seconds, while the total duration of each behaviour will be presented in percentages, by dividing for each participant the total duration of the specific behaviour by the total duration of each videotape.

Actual Thought/Feeling Measures

As suggested by Ickes and colleagues (Ickes et al., 1990), the participants’ thought/feeling entries were coded by five independent judges (i.e. undergraduate college students). The judges watched all videotapes that were stopped each time one of the interacting persons had reported having had a thought or a feeling. The judges rated for each thought/feeling entry how difficult they thought it was to infer the specific content of each thought/feeling entry on a 7 point scale ranging from 1 (very easy) to 7 (very difficult). Because of the satisfactory interrater reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .75) of the five judges, we averaged the judges’ scores for each though/feeling entry.

Similarly, the same five judges rated for each thought/feeling entry how concrete or abstract the specific content of each thought/feeling entry was on a 7 point scale ranging from 1 (very concrete) to 7 (very abstract). Because the interrater reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) of the five judges was .72, the judges’ scores were averaged for each thought/feeling entry.

Finally, the same five judges assessed for each thought/feeling entry whether the focus of the thought/feeling entry was (a) on the self, (b) the interaction partner, (c) other person(s), (d) the research context, or (e) a tangible environmental object or event. The interrater reliabilities (Cronbach’s alpha) for these mutually non-exclusive categories varied between .86 and .95.

Empathic Accuracy Measures

Following the logic and procedure described by Ickes and colleagues (Ickes et al., 1990; Marangoni et al., 1995), the empathic accuracy was computed by comparing the written content of each actual thought/feeling entry with that of the corresponding inferred thought/feeling entry.

The same five judges were instructed to compare each inferred thought/feeling entry with the corresponding thought/feeling entry and to rate the level of similarity on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (essentially different content) through 1 (somewhat similar but not the same content) to 2 (essentially the same content). The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the five judges’ content accuracy ratings was .89 for the PDD group and .92 for the control group. Because of the high reliability of the judges’ ratings, the mean of the empathic accuracy scores rated by the five judges was calculated for each particular inference. In order to derive an overall empathic accuracy score for each perceiver, the mean empathic accuracy scores were summed across all thought/feeling inferences and then divided by the total number of accuracy points that could be obtained for a given number of inferences, and multiplied by 100. As in previous studies (Buysse & Ickes, 1999; Ickes et al., 1990; Ickes et al., 1990), the baseline empathic accuracy for each of the participants was estimated by randomly pairing each set of the actual thought/feeling entries with the corresponding set of the partner’s inferences and rating the content of these randomly paired entries on similarity. The internal consistency of the baseline accuracy provided by the five judges was .94 for the PDD group and .89 for the control group. The mean of the baseline accuracy scores rated by the five judges was further calculated for each inference. Then, these baseline accuracy scores were summed across all thought/feeling inferences and then divided by the total number of accuracy points that could be obtained for a given number of inferences and multiplied by 100. Finally, we obtained an adjusted measure of empathic accuracy for each perceiver, by subtracting the baseline accuracy scores for each participant from the empathic accuracy scores for that participant (see also Ickes et al., 1990).

Following this logic, the empathic accuracy scores for each perceiver were calculated for all thought/feeling entries belonging to (a) the most easy-to-infer thought/feeling entries, (b) the most-difficult-to-infer thought/feeling entries, and (c) the remaining moderate difficult-to-infer thought/feeling entries. Similarly, the empathic accuracy scores for each perceiver were calculated for all thought/feeling entries belonging to (a) the most abstract thought/feeling entries, (b) the most concrete thought/feeling entries, and (c) the moderate abstract thoughts and feelings. Finally, we computed for each perceiver the empathic accuracy scores for all the thought/feeling entries whether or not belonging to the 5 categorical classifications of the actual thoughts and feelings, more specifically (a) the self, (b) the interaction partner, (c) other person(s), (d) the research context, and (e) a tangible environmental object or event.

Results

Within-Dyad Differences with Regard to the Behavioural Characteristics

Since the empathic accuracy design allows us to study the overt behaviour of the participants, we tested our research question whether or not the verbalisation, gazing and stimulatory gestures differed between the dyad members. As shown in Table I, analysis revealed that the within-dyad difference in total duration of verbalisation approached significance, t(10) = −2.05, p = .07. There were no significant within-dyad differences in the total duration of gazing and the total duration of stimulatory gestures. Furthermore, a series of paired t-tests revealed that there were no significant within-dyad differences in the frequency of verbalisation, in the frequency of gazing, and in the frequency of stimulatory gestures. Significant within-dyad differences were found with regard to the mean duration of verbalisation, indicating that participants with PDD verbalise longer than control participants at the moment they get up to speak, and with regard to the mean duration of gazing, indicating that the period of each look at the interaction partner is shorter for participants with PDD than for control participants. No significant within-dyad difference was found with regard to the mean duration of stimulatory gestures.

In order to know more about the level of interactional involvement, two sets of correlations are of interest. First, we are interested in the within-dyad correlations of the behavioural characteristics. As shown in Table II, the verbalisation of the PDD participants significantly relates to the verbalisation of the control participants, which implies that more verbalisation by one interaction partner is reciprocated by more verbalisation by the other interaction partner. The same pattern is true for gazing, but not for stimulatory gestures. The fact that several other significant within-dyad associations were found (see Table II) suggests that reciprocity is a main characteristic of the behavioural interactions. Second, we are interested in the within-group correlations of the different behaviours. Two significant positive associations were found between verbalisation and gazing, indicating that the more a dyad member verbalises, the more this person is looking at the interaction partner. Furthermore, the significant negative association between the stimulatory gestures and the gazing of the participants with PDD indicates that the more a participants with PDD is touching some object or body part, the less he is looking at the interaction partner, and vice versa. By using the formula of HaysFootnote 1(1994), transformation of the correlations into z-scores revealed that the associations between stimulatory gestures and gazing were equally strong in both groups.

Within-Dyad Differences with Regard to the Actual Thought/Feeling Entries

A paired t-test revealed no significant within-dyad difference between the number of thoughts and feelings reported by the PDD participants (M = 16.55, SD = 11.99) and the control participants (M = 20.45, SD = 10.43), t(10) = −.86.

Within-dyad analysis revealed that the mean difficulty of the actual thought/feeling entries (aggregated over the 5 judges and all entries) did not differ significantly, t(10) = .77, with M = 4.92 (SD = 1.21) for the PDD participants and M = 4.93 (SD = 1.14) for the control participants. Then, based on the quartile distribution of both groups’ thought/feeling entries and independent of the “empathic accuracy” variable, the thought/feeling entries were divided into (a) the 25.2% most easy-to-infer thought/feeling entries, (b) the 51.5% moderate difficult-to-infer thought/feeling entries, and (c) the 23.3% most-difficult-to-infer thought/feeling entries. Analysis revealed that there were no significant within-dyad differences (χ2 (2) = 1.16) with regard to the percentages of thought/feeling entries classified as easy-to-infer thought/feeling entries (24.3% for the PDD participants and 25.8% for the control participants), moderately difficult-to-infer thought/feeling entries (50.0% for the PDD participants and 52.5% for the control participants), and difficult-to-infer thought/feeling entries (25.7% for the PDD participants and 21.7% for the control participants).

Within-dyad analysis revealed that the mean abstractness of the actual thought/feeling entries (aggregated over the 5 judges and all entries) was not significantly different, t(10)=1.36, with M = 3.98 (SD = 1.13) for the PDD participants and M = 4.34 (SD = 1.08) for the control participants. Following the above-mentioned procedure, the thought/feeling entries were divided into (a) the 27.9% most abstract thought/feeling entries, (b) the 45.2% moderate abstract thought/feeling entries, and (c) the 26.7% most concrete thought/feeling entries. Significant within-dyad differences were found (χ2 (2) = 12.23, p < .01) with regard to the percentages of thought/feeling entries classified as abstract thought/feeling entries (35.4% for the PDD participants and 22.7% for the control participants), moderately abstract thought/feeling entries (43.4% for the PDD participants and 46.7% for the control participants), and concrete thoughts and feelings (21.2% for the PDD participants and 30.6% for the control participants), indicating that the participants with PDD had more abstract thought/feeling entries than the control participants and had less concrete thoughts and feelings than the control participants.

Furthermore, within-dyad comparison of the topic of the thought/feeling entries revealed no significant differences with regard to the thought/feeling entries that focussed on the self, other person(s), the research context, and a tangible environmental object or event (see Table III). However, a significant within-dyad difference was found with regard to the thoughts and feelings that focussed on the interaction partner, t(10) = 2.58, p < .05, indicating that the control participants had more thoughts and feelings that focussed on the interaction partner than the participants with PDD.

Finally, there was no significant within-dyad difference in the total amount of time required to write down their original thoughts or feelings, t(10)=.06. The mean time was 36.31 minutes (SD = 17.57) for the participants with PDD and 35.96 minutes (SD = 19.84) for the control participants. By dividing for each participant the time required to write down all original thought/feeling entries by the number of thought/feeling entries, we derived for each dyad member the average time required to write down a thought or feeling. Analysis revealed that the within-dyad difference in average time (in minutes) required to write down a thought or feeling approached significance, t(10) = −2.11, p = .06, with M = 2.47 (SD = 0.78) for the PDD participants and M = 1.84 (SD = 0.63) for the control participants.

Within-Dyad Differences with Regard to Empathic Accuracy

We compared the empathic accuracy scores of the participants with PDD with those of the control participants, to test for our primary hypothesis, that the control participants would display significantly more empathic accuracy than the participants with PDD. Contradictory to our hypothesis, there was no significant within-dyad difference (see Table IV). The mean adjusted accuracy score was 25.70% for the PDD participants and 25.14% for the control participants. Table IV contains data that provide comparisons of the original content accuracy scores, the baseline accuracy scores and the adjusted measures of empathic accuracy (see ‘empathic accuracy measures’ section for more detailed description).

The mean empathic accuracy scores of the thought/feeling entries belonging to the most easy-to-infer thought/feeling entries, the most difficult-to-infer thought/feeling entries and the moderately difficult-to-infer thought/feeling entries are shown in Table V, represented separately for each group. We conducted a 2 (Group: PDD versus Control) × 3 (Difficulty: Easy, Moderate and Difficult) ANOVA on the empathic accuracy scores, with Group and Difficulty as within-subject factors. The analysis revealed no significant main effect for Group, F(1,10) < 1. However, a significant main effect for Difficulty was found, indicating that the most difficult-to-infer thought/feeling entries are less accurately inferred than the most easy-to-infer thought/feeling entries, F(2,9) = 6.27, p < .01. The interaction between Group and Difficulty yielded no significance, F(2,9) = 2.07, indicating that both groups have the same tendency to be less accurate in inferring more difficult thought/feeling entries.

Furthermore, Table V presents for each group the mean empathic accuracy scores of the thought/feeling entries belonging to one of the three categories of abstractness. We conducted a 2 (Group: PDD versus Control) × 3 (Abstractness: Concrete, Moderate and Abstract) ANOVA on the empathic accuracy scores, with Group and Abstractness as within-subject factors. The analysis revealed no significant main effect for Group, F(1,10) < 1. We found no significant main effect for Abstractness, F(2,9) < 1, indicating that there were no differences in empathic accuracy between the most concrete-to-infer, the moderate concrete-to-infer and the most abstract-to-infer thought/feeling entries. The interaction between Group and Abstractness was not significant, F(2,9) < 1.

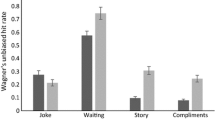

For each group, the mean empathic accuracy scores of thought/feeling entries belonging to a specific topic are shown in Table VI. A series of 2 (Group: PDD versus Control) × 2 (Topic: Presence versus Absence of a particular focus) ANOVAs on the empathic accuracy scores were conducted, with Group and Topic as within-subject factors. As shown in Table VI, the analyses revealed no significant effect of group for each of the more detailed empathic accuracy scores. Furthermore, the analyses revealed only one significant main effect of topic, indicating that the thought/feeling entries that focussed on a tangible environmental object or event are less accurately inferred than the thought/feeling entries without this focus. No significant interaction effects (Topic x Group) were found.

We measured the total amount of time (in minutes) required to infer and write down the other person’s thoughts and feelings. No significant within-dyad difference was found, t(10) = 1.53, with M = 42.43 (SD = 27.95) for the participants with PDD and M = 29.71 (SD = 19.29) for the control participants. By dividing for each participant the time required to write down all inferences by the number of inferences, we derived for each dyad member the average time required to infer and write down a thought or feeling. No significant within-dyad difference was found in the average time required to infer the other person’s thought or feeling, t(10) = 1.11. The mean time was 2.17 minutes (SD = .80) for the participants with PDD and 1.88 minutes (SD = .55) for the control participants.

Correlates of the Empathic Accuracy Measures

We found a significant association between the mean empathic accuracy of the control group and the total duration of the stimulatory gestures of the group with PDD, indicating that the more one dyad member is touching some object or body part, the better the interaction partner can infer the thoughts and feelings. No other significant associations between empathic accuracy and the total duration of a specific behaviour were found (see Table VII). However, a significant negative association was found between the empathic accuracy of the PDD group and the mean duration of the PDD group’s gazing, indicating that the empathic accuracy of the participants with PDD decreases when the mean time of their gazes increases and vice versa. We further used the formula of Hays to transform the Pearson correlations into z-scores. As shown in Table VII, the transformation revealed that the strength of the associations was equally strong in both groups.

Finally, we calculated for both groups the correlations between empathic accuracy scores, chronological ages, IQ-scores and inference times. As shown in Table VIII, Pearson correlations revealed no significant associations between the empathic accuracy scores and the time needed to infer another person’s thought/feeling entry. Furthermore, no significant associations were found between empathic accuracy scores and IQ scores, or between empathic accuracy scores and ages. Since we had the empathic accuracy scores of the 11 participants with PDD on both videotapes of the Empathic Accuracy Task of Roeyers et al. (2001), we were able to correlate these scores with the present empathic accuracy scores of the PDD participants. Pearson correlations revealed that the empathic accuracy scores of the 11 participants with PDD correlated significantly with their performance on videotape 1 of the Empathic Accuracy Task (Roeyers et al., 2001).

Discussion

The dyadic empathic accuracy design allowed us to study both the overt and the covert behaviour of the dyad members. As expected, within-dyad analyses of the overt behaviour of the dyad members revealed that there were significant and nearly significant differences between the total and mean duration of verbalisation and gazing. While the within-dyad analyses demonstrated that the social interaction between participants with and without PDD is characterised by a strong level of behavioural reciprocity, further within-group analyses revealed that the different behaviours correlated with each other and that the associations between these behaviours were equally strong in both groups. Contrary to expectations, the main finding of the within-dyad analyses of the covert behaviour was that the participants with PDD did not differ from the control adults in the ability to infer the thoughts and feelings of their interaction partner.

However, when we are interested in the inference abilities of adults with or without PDD while interacting with each other, the peculiar behavioural characteristics of adults with PDD should be taken into consideration (e.g. Howlin, 1997, 1998). Several people, who meet for the first time a normally intelligent adult with PDD, often notice that this person is —in a way- somewhat strange, but because of their unfamiliarity with the PDD diagnosis, they can not figure out what exactly makes the other person so odd (Attwood, 1998; Wing, 1992). Moreover, it has proved surprisingly difficult to determine accurately what is abnormal about autistic subjects’ social behaviour through systematic studies (Hobson & Lee, 1998). Sometimes, the oddity is caused by a single word or gesture that occurs at an inappropriate moment. Otherwise, it is possible that the behaviour of the adult with PDD does not occur at adequate strength or is not exhibited at all and which absence is inappropriate (Howlin, 1997; Lord & Magill-Evans, 1995; Schreibman, 1994; Tsai, 1992). When a typically developing adult interacts with an adult with PDD, we can assume that the peculiarities of the person with PDD have an influence either on the behaviour of the person without PDD or on the perception that the person forms on the PDD adult or both. Even so, the behaviour of the typically developing adult will influence the behaviour and thoughts or feelings of the person with PDD (Lord & Magill-Evans, 1995). In the present study it is possible to investigate whether or not the combination between some behavioural characteristics and the content of the dyad members’ thought/feeling entries affected the inference ability of both groups. Therefore, part 2 was conducted.

Part 2

In the second part, the procedure used was the standard stimulus paradigm (Marangoni et al., 1995). A panel of typically developing persons was asked to view all eleven videotapes of the dyadic interaction and to make inferences about the specific content of the thought/feeling entries of each dyad member. The perceivers were kept unaware that in each videotape one of the interacting persons had PDD. The standard stimulus paradigm enabled us to assess whether or not perceivers reached different accuracy rates for thought/feeling entries belonging to persons with PDD and for those belonging to typically developing persons. On the basis of the characteristics of persons with PDD, we assume that the accuracy scores of the perceivers will be higher for thought/feeling entries belonging to the typically developing persons than for those belonging to the persons with PDD.

Method

Participants

The participants were thirteen typically developing subjects who were recruited by a temping agency. All participants (8 male and 5 female) were students. On the basis of their study we can assume that they are of normal intelligence. The mean chronological age of the group was 21.12 year (SD = 2.07).

Procedure

The procedure used was based on Ickes and colleagues (Ickes et al., 1990; Marangoni et al., 1995). The 13 participants were invited to come together to our laboratory. They were randomly divided into two groups. The first group comprised 7 participants who viewed six of the eleven above-mentioned videotapes during a day. The second group comprised 6 participants who viewed eight of the eleven videotapes. By doing so, three videotapes were seen by both groups. In order to avoid bias, all participants were kept unaware of the purpose of the study.

The procedure was based on the standard stimulus paradigm and was essentially the same as in the first part. The participants of each group were seated before a video-screen and were instructed to view each videotape one time without an interruption. After viewing the videotape in its entirety, the experimenter asked them to view the videotape a second time. However, this time the experimenter manually interrupted the videotape at each of those points at which one of the two interaction partners had reported a specific unexpressed thought or feeling. Whenever the videotape was paused, the members of the panel were asked to make inferences about the specific content of the unexpressed thought/feeling entries and to write down (a) whether the entry was presumed to be a thought or a feeling, and (b) the specific content of the thought/feeling entry. To ensure that the perceivers clearly understood the procedure, a preparatory session was given with other material. When the participants had viewed all tapes and had completed the task, they were debriefed more fully and thanked for their participation in the study.

Empathic Accuracy Measure

The empathic accuracy scores of the members of the panel were computed by using the same logic and procedure as described in the first part. The same above-mentioned five independent judges had to compare each perceiver’s inferred thought/feeling entry with the corresponding original thought/feeling entry and to rate the level of similarity on a 3-point scale, ranging from 0 (essentially different content) through 1 (somewhat similar but not the same content) to 2 (essentially the same content). The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the five judges’ content accuracy ratings was .86 for the thought/feeling entries belonging to the PDD participants and .94 for the thought/feeling entries belonging to the control participants. Similar to part 1, the original empathic accuracy scores were calculated for each perceiver.

The baseline level of empathic accuracy for each of the panel members was estimated by randomly pairing each set of the perceiver’s inferred thought/feeling entries with the corresponding set of the original thought/feeling entries and rating the content of these randomly paired original/inferred entries on similarity. The internal consistency of the baseline accuracy provided by the five judges was .87 for the thought/feeling entries belonging to the PDD group and .67 for the thought/feeling entries belonging to the control group. Following the logic of the first part, the baseline empathic accuracy scores were calculated for each member of the panel. By subtracting for each panel member the baseline empathic accuracy scores from the original content scores, we derived a measure of global empathic accuracy for each panel member.

Results

The mean original content accuracy score (M = 32.60%, SD = 9.28%) of the panel for thought/feeling entries belonging to the PDD participants did not differ significantly from the mean original content accuracy score (M = 28.72%, SD = 11.56%) of the panel for thought/feeling entries belonging to the control participants, t(10) = −.85. Furthermore, the mean adjusted empathic accuracy score of the panel was 19.83% (SD = 9.82%) for thought/feeling entries belonging to the PDD participants and 19.25% (SD = 9.29%) for thoughts and feelings belonging to the control participants. Analysis revealed no significant differences in inferring the thoughts and feelings of adults with PDD and those of control adults, t(10) = −.15.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

This paper attempted to measure the social functioning of eleven normally intelligent adults with PDD during a naturalistic conversation with a typically developing stranger. The paper differs from previous research in that the procedure used enabled us to study the overt and the covert behaviour of the interacting participants. The study consisted of two parts.

In the first part, analyses of the overt behaviour revealed that during a naturalistic dyadic conversation participants with PDD verbalise longer than control participants whenever they speak to their interaction partner and that the period of each look at the interaction partner is shorter for participants with PDD than for control participants. Furthermore, participants with PDD tended to speak more than control participants. No significant within-dyad differences were found with regard to the stimulatory gestures. These data are consistent with other behavioural studies in which differences between subjects with PDD and control subjects in the frequency of non-verbal expression during social interaction were found to be much less than expected (Tantam, Holmes, & Cordess, 1993; Van Engeland, Bodnar, & Bolhuis, 1985; Willemsen-Swinkels, Buitelaar, Weijnen, & Van Engeland, 1998). As is expected in studies with typically developing dyads (e.g. Stinson & Ickes, 1992), we further found several reciprocities between the verbalisations, gazes and stimulatory gestures of the dyad members, indicating that most behaviours of the dyad member are reciprocated by one or more behaviours of the interaction partner.

The dyadic interaction design of the first part enabled us to explore the theme(s) of the dyad members’ original thoughts and feelings. Analyses indicated that the percentages of thought/feeling entries belonging to a specific topic were merely the same for the PDD participants and the control participants, with the exception of thoughts and feelings that focussed on the interaction partner. Control participants had twice as many thought/feeling entries that focussed on the interaction partner than participants with PDD. Further analyses demonstrated that the thought/feeling entries of the adults with PDD were as difficult as those of the typically developing adults. Although the mean level of abstractness was similar for thoughts and feelings belonging to participants with PDD and for those belonging to control participants, participants with PDD had more abstract thoughts and feelings than control participants and had less concrete thoughts and feelings than control participants.

Contrary to our main hypothesis, the participants with PDD did not differ from the typically developing participants in the ability to infer the thoughts and feelings of their interaction partner. Further analyses indicated that the empathic accuracy scores decreased with an increasing level of difficulty, although this effect was similar for both groups. Only one main effect of topic on the empathic accuracy scores was found, indicating that thought/feeling entries that focussed on a tangible environmental object or event are less accurately inferred than the thought/feeling entries without this focus. Furthermore, the findings do not endorse the assumption that the association between the participants’ behavioural characteristics and the empathic accuracy scores is different for participants with PDD and control participants, which—in a way- is inconsistent with the study of Koning and Magill-Evans (2001). In this study, subjects with PDD were significantly more impaired than control subjects to infer others’ affective state when dealing with the simultaneous presentation of facial, vocal, body and situational cues.

In the second part, we explored whether or not the inference ability of both groups was affected by the combination between some behavioural characteristics and the content of the interaction partner’s thoughts and feelings. The analyses revealed that the thought/feeling entries of the PDD participants were as difficult to infer as the thought/feeling entries of the control participants, which indicated that the inference ability of both groups was independent of the dyad members’ behavioural characteristics and the content of the dyad members’ thoughts and feelings.

The results of both parts are surprising given the daily life perspective taking difficulties of adults with PDD and implicate that, under some circumstances, some high-functioning adults with PDD are able to read the thoughts and feelings of others during a naturalistic conversation. However, it should be noted that the high-functioning adults with PDD had an intelligence level far above the normal range and were invited to participate in the present study on the basis of their good performance on previous mind-reading tasks (Roeyers et al., 2001). Many researchers have stressed the role of both verbal and chronological age in the performance on theory of mind tasks and have suggested that intelligence might compensate for conceptual perspective taking strategies (Bowler, 1992; Happé, 1995; Prior, Dahlstrom, & Squires, 1990; Yirmiya & Shulman, 1996). The fact that the IQ-scores of the participants did not correlate with the empathic accuracy scores, suggests that it can not be taken for granted that the good empathic accuracy scores of the present PDD group are solely due to their higher level of intelligence. The higher intelligence of the PDD persons can play a necessary but not a sufficient role in their task success.

There are, however, two possible alternative explanations. A first explanation is based on social psychological research. According to Eisenberg, Murphy and Shepard (1997), individuals use a variety of types of information to decipher what other people are thinking or feeling. Karniol (1995) found that older children use a greater variety of strategies than younger children while they are inferring the thoughts of other persons, and that the strategies of older children rely more on personal information, whereas the younger children’s strategies rely more on situational information. Even so, Gnepp, Klayman and Trabasso (1982) found that the use of type of information to rely on when evaluating the emotional states of others, varies with age. Increasing with age, people prefer to use personal information (i.e. specific information about the individual) over normative information (i.e. information about the group to which the individual belongs), and normative information more than situational information (i.e. information about another’s physical or social environment) (Gnepp et al., 1982). Although the present investigation does not provide information about the specific type of information the participants with or without PDD are relying on, it can be considered that all participants are familiar with the script of the present study (i.e. an initial conversation of the getting acquainted type). This familiarity might be derived from experience or (with regard to adults with PDD) by having learned the script previously. Therefore, cues in the situation may lead to the retrieval of information from memory about similar situations to that of the target person, as well as social scripts or other socially relevant knowledge (see Karniol, 1995). However, there has been as yet no systematic examination of the relation of scriptal knowledge of adults with PDD to their mind-reading performance. Moreover, very little is known about the capabilities of subjects with autism in scripts. While a recent study of Trillingsgaard (1999) with a small sample of children with autism suggested that children with autism have significantly fewer well-organized scripts for familiar social routines (such as make a cake or celebrate a birthday) than normal control children, the results of a study of Volden and Johnston (1999) suggested that the basic scriptal knowledge of children with autism appears to be intact. The question remains whether these results can be generalised to adults with PDD. This could be an area of further investigation.

The second explanation is allied to the first explanation. In a previous study with the empathic accuracy design, Hancock and Ickes (1996) already suggested that an 8-minute interaction period does not provide enough time for the interactants to import different meaning contexts into the interaction, and that it might be that two strangers, when they interact for the first time, employ rather a generic meaning context for the first minutes of the interaction, until they feel sufficiently acquainted with each other to go beyond it. Although we believe that the design of the present study is an advantage for the naturalistic study of the mind-reading abilities of persons with PDD, every medal has two sides. On the one hand the empathic accuracy design implies that the mind-reading abilities can be studied ecologically, on the other hand the ecological design implies that the participants can structure the social situation according to their own possibilities or desires. For instance, during the initial conversation the participants can talk when they are willing to do, but if one of the participants does not want to talk, he/she does not have to talk. This implies that the participants can influence the conversation and, in a way, have control over the situation. Even so, if one of the interaction partners has lower social skills than the other, then the level of the conversation will drop as far as the level of social abilities of the first interaction partner. However, the advantage of being able to structure the present 8-minute social interaction can be considered as a once-only event, because in daily life it is impossible to structure the miscellany of protracted social interactions. Furthermore, it should be noted that the ability to structure the situation has an impact on both the content of the thought/feeling entries of each dyad member and the inference ability of each interaction partner. Suppose that the dyad members decided to have only small talks with each other and did not go beyond the generic meaning context of the “getting acquainted” type, then the content of their thoughts and feelings would also be rather generic. Inferring generic thoughts and feelings requires different (and probably less) social-cognitive acquirements from the interaction partner, than inferring thoughts and feelings that do not (or less) represent familiar experiences.

The fact that the present mind-reading performance of the eleven participants with PDD correlates with their performance on the first empathic accuracy videotape in the study of Roeyers et al. (2001) and does not correlate with their performance on the second videotape, does not rule out either explanation. As noted by Roeyers et al. (2001) the first videotape was more structured and more predictable than the second videotape. In order to obtain more information about the relationship between scriptal knowledge, structuralisation and mind-reading performance, we are at the moment conducting a study in which adults with a pervasive developmental disorder each have to view different videotapes with varying level of structure and with different scripts, and have to infer the thoughts and feelings of the videotaped targets.

The present study may contribute towards a better understanding of the mind-reading abilities of adults with PDD during a naturalistic conversation with a stranger. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the design of the study still differs from any real life social situation in several ways. First, the participants had to infer the thoughts or feelings of their interaction partner in a retrograde phase (i.e. while they were viewing the videotape of their own conversation for a second time). The demands of daily life do not permit us to review our interactions and expect to make quick inferences about the thoughts and feelings of the other at the specific moment these thoughts and feelings occur. Second, the design permits the participants to use as much time as needed to infer the thoughts and feelings of their interaction partner. Although the participants with PDD did not need more time than the control participants to infer the other’s thoughts and feelings, in daily life they may not have the time they need and it might be that therefore their impaired mind-reading abilities become more apparent. Third, in daily life we do not have access to the original thoughts and feelings of the interactants. It can be suggested that persons with PDD might have had more difficulties to write down their original thought/feeling entries, although there is no conclusive evidence to support this hypothesis. On the one hand this hypothesis can be supported by the fact that participants with PDD tended to need more time to write down a single thought/feeling entry. On the other hand, the analysis revealed no significant within-dyad difference in the total amount to write down the thought/feeling entries. Besides the mental strain to write down the original thoughts and feelings, it should be pointed out that there is no reason to believe that persons with PDD are less accurate in writing down their own thoughts and feelings. We have previously shown that the mean difficulty and the mean abstractness of thought/feeling entries of the participants with PDD were similar to those of the control participants, and no significant differences were found in the inference ability of the thirteen typically developing participants with regard to the thought/feeling entries belonging to participants with PDD and those belonging to control participants.

Finally, it seems that being in the interaction yields higher empathic accuracy scores than perceiving the interaction. While the mean empathic accuracy scores of the thirteen perceivers in part 2 were around 19%, the mean empathic accuracy scores of the dyad members in part 1 were around 25%. This suggests that the empathic accuracy scores are not only mediated by components of the perceiver and components of the target, but also by the intersubjective meaning context of both dyad members (who are target and perceiver at the same time). Although highly hypothetical, this suggests that the intersubjective meaning context, which is created through the conversation and non-verbal behaviours of the dyad members, enhances the empathic accuracy of the dyad members or, conversely, affects negatively the empathic accuracy of participants who serve only as perceivers.

In sum, the present study found no support for the main hypothesis that the inference ability of persons with PDD would be more hampered than the inference ability of control persons while having a naturalistic conversation with each other. The study differs from previous research in that both the overt behaviour and the covert thoughts and feelings of adults with and without PDD were meticulously analysed in a standardised manner. The results of the study underline the importance of exploring the impact of previous scriptal knowledge on the mind-reading performance and the possible advantage the adults with PDD obtain from more structured situations compared with less structured situations.

Notes

\({{z_{1}-z_{2}}\over{\sqrt{{{{1}\over{n_{1}-3}}}+{{1}\over{n_{2}-3}}}}}\)

References

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author

Attwood T., (1998).Asperger’s Syndrome: A Guide For Parents and Professionals Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London

Baron-Cohen S., Jolliffe T., Mortimore C., Robertson M., (1997). Another advanced test of theory of mind: Evidence from high-functioning adults with autism or Asperger syndrome Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 38: 813–822

Bowler D. M., (1992). Theory of mind in Asperger’s syndrome Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 33: 877–893

Buysse A., Ickes W., (1999). Topic-relevant cognition and empathic accuracy in laboratory discussions of safer sex Psychology and Health 14: 351–366

Eisenberg N., Murphy B., Shepard S., (1997). The development of empathic accuracy. In Ickes W., (Ed), Empathic Accuracy Guilford Press. New York, 73–116

Gnepp J., Klayman J., Trabasso T., (1982). A hierarchy of information sources for inferring emotional reactions Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 33: 111–123

Hancock M., Ickes W., (1996). Empathic accuracy: When does the perceiver-target relationship make a difference? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 13: 179–199

Happé F. G. A., (1995). The role of age and verbal ability in the theory of mind task performance of subjects with autism Child Development 66: 843–855

Hays W.L., (1994). Statistics 5 Harcourt Brace College Publishers: Orlando

Hobson P., Lee A., (1998). Hello and goodbye: A study of social engagement in autism Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 28: 117–127

Howlin P., (1997). Autism: Preparing for Adulthood. Routledge: New York

Howlin P., (1998). Practitioner review: Psychological and educational treatments for autism Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 39: 307–322

Ickes W., (1997). Empathic Accuracy Guilford Press. New York

Ickes, W., Bissonnette, V., Garcia, S., & Stinson L. L. (1990). Implementing and using the dyadic interaction paradigm. In C. Hendrick & M.S. Clark (Eds), Review of Personality and Social Psychology: Research Methods in Personality and Social Psychology (Vol. 11, pp. 16–44). Sage. Newbury Park, CA

Ickes W., Robertson E., Tooke W., Teng G., (1986). Naturalistic social cognition: Methodology, assessment, and validation Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59: 730–742

Ickes W., Stinson L., Bissonnette V., Garcia S., (1990). Naturalistic social cognition: Empathic accuracy in mixed-sex dyads Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59: 730–742

Kaland N., Moller-Nielsen A., Callesen K., Mortensen E.L., Gottlieb D., Smith L., (2002). A new ‘advanced’ test of theory of mind: Evidence from children and adolescents with Asperger syndrome Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 43: 517–528

Karniol R. (1995). Developmental and individual differences in predicting others’ thoughts and feelings: Applying the transformation rule model. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Review Of Personality And Social Psychology: Social Development (Vol. 15, pp. 27–48). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Kleinman J., Marciano P., Ault R., (2001). Advanced theory of mind in high-functioning adults with autism Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 31: 29–36

Koning C., Magill-Evans J., (2001). Social and language skills in adolescent boys with Asperger syndrome Autism 5: 23–36

Lord C., Magill-Evans J., (1995). Peer interactions of autistic children and adolescents Development and Psychopathology 7: 611–626

Marangoni C., Garcia S., Ickes W., Teng G., (1995). Empathic accuracy in a clinically relevant setting Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68: 854–869

Noldus L.P., (1991). The observer: A software system for collection and analysis of observational data Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers 23: 415–429

Noldus L.P.J.J., Trienes R.J.H., Hendriksen A.H.M., Jansen H., Jansen R.G., (2000). The Observer Video-Pro: New software for the collection, management, and presentation of time-structured data from videotapes and digital media files Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers 32: 197–206

Ponnet, K., Roeyers, H., Buysse, A., De Clercq, A., & Van der Heyden, E. (2004). Advanced mind-reading in adults with Asperger syndrome. Autism 8: 249–269

Prior M. R., Dahlstrom B., Squires T. L., (1990). Autistic children’s knowledge of thinking and feeling states in other people Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 31: 587–601

Roeyers H., Buysse A., Ponnet K., Pichal B., (2001). Advancing advanced mind-reading tests: Empathic accuracy in adults with a pervasive developmental disorder Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 42: 271–278

Schreibman L., (1994). General principles of behavior management. In E. Schopler, Mesibov G., (Eds), Behavioral Issues in Autism. Plenum Press: New York. 13–38

Simpson J. A., Ickes W., Blackstone T., (1995). When the head protects the heart: Empathic accuracy in dating relationship Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69: 629–641

Stinson L., Ickes W., (1992). Empathic accuracy in the interactions of male friends versus male strangers Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 62: 787–797

Tantam D., Holmes D., Cordess C., (1993). Nonverbal expression in autism of Asperger type Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 23: 111–133

Trillingsgaard P., (1999). The script model in relation to autism European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 8: 45–49

Tsai L., (1992). Diagnostic issues in high-functioning autism. In E. Schopler, Mesibov G., (Eds), High-Functioning Individuals With Autism. Plenum Press: New York. 11–40

Van Engeland H., Bodnar F. A., Bolhuis G., (1985). Some qualitative aspects of the social behavior of autistic children: An ethological approach Journal of Child Psychology, Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 26: 879–893

Volden J., Johnston J., (1999). Cognitive scripts in autistic children and adolescents Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 29: 203–211

Willemsen-Swinkels S., Buitelaar J., Weijnen F., Van Engeland H., (1998). Timing of social gaze behaviour in children with a pervasive developmental disorder Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 28: 199–210

Wing L., (1992). Manifestations of social problems in high-functioning autistic people. In E. Schopler, Mesibov G., (Eds), High-Functioning Individuals With Autism. Plenum Press: New York. 11–40

Yirmiya N., Shulman C., (1996). Seriation, conservation, and theory of mind abilities in individuals with autism, individuals with mental retardation, and normally developing children Child Development 67: 2045–2059

Zager D. B., (1999). Autism: Identification, Education, and Treatment Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers: New Jersey

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ponnet, K., Buysse, A., Roeyers, H. et al. Empathic Accuracy in Adults with a Pervasive Developmental Disorder During an Unstructured Conversation with a Typically Developing Stranger. J Autism Dev Disord 35, 585–600 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-005-0003-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-005-0003-z