Abstract

The current 3-wave study examined bidirectional associations between peer victimization and functions of aggression across informants over a 1-year period in middle childhood, with attention to potential gender differences. Participants included 198 children (51% girls) in the third and fourth grades and their homeroom teachers. Peer victimization was assessed using both child- and teacher-reports, and teachers provided ratings of reactive and proactive aggression. Cross-classified multilevel cross-lagged models indicated that child-reports, but not teacher-reports, of peer victimization predicted higher levels of reactive aggression within and across academic years. Further, reactive aggression predicted subsequent increases in child- and teacher-reports of peer victimization across each wave of data. Several gender differences, particularly in the crossed paths between proactive aggression and peer victimization, also emerged. Whereas peer victimization was found to partially account for the stability of reactive aggression over time, reactive aggression did not account for the stability of peer victimization. Taken together with previous research, the current findings suggest that child-reports of peer victimization may help identify youth who are risk for exhibiting increased reactive aggression over time. Further, they highlight the need to target reactively aggressive behavior for the prevention of peer victimization in middle childhood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Both peer victimization and aggression are common among youth and are associated with increased risk for a wide range of adjustment problems, including delinquency, substance use, peer rejection, and symptoms of depression and anxiety (e.g., Reijntjes et al. 2010, 2011; Vitaro and Brendgen 2011). Although experiences of victimization and functions of aggression have been consistently linked over time (e.g., Lamarche et al. 2007; Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007), discrepant findings in the extant literature have precluded firm conclusions regarding the direction of effects and whether associations differ among boys and girls. Additional longitudinal research is therefore needed in order to clarify the nature of these temporal relations and inform the development of intervention efforts. The current study sought to advance this literature by examining associations between peer victimization and reactive and proactive aggression across informants (i.e., children and teachers) over a 1-year period in middle childhood, with attention to potential gender differences. In particular, the three-wave methodological design provided the opportunity to evaluate prospective links within an academic year and across the transition into the subsequent academic year. The indirect effects of reactive aggression on the stability of peer victimization and peer victimization on the stability of reactive aggression were also investigated.

These objectives were addressed during the middle childhood years. It has been suggested that the basis for functioning in peer groups is formed during this time period (Pouwels and Cillessen 2013). Further, Mahady Wilton et al. (2000) observed that elementary school-age children were most likely to respond to incidents of peer victimization with aggressive coping responses. Given that youth who react to provocation with revenge-seeking and angry retaliatory behavior are likely to escalate aggressive encounters with peers and increase their risk of developing more stable and severe patterns of victimization (e.g., Perry et al. 1990), middle childhood represents an important developmental period in which to investigate these associations.

Peer Victimization and Functions of Aggression

Peer victimization is a developmentally salient interpersonal stressor that refers to the experience of being the recipient of peers’ aggressive behavior. A substantial body of research has demonstrated that such experiences are linked to higher levels of problem behavior, including aggression, over time (Reijntjes et al. 2011). It is important to note, however, that emerging evidence suggests that experiences of victimization may be differentially related to functions of aggressive behavior, namely reactive and proactive aggression (e.g., Lamarche et al. 2007; Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007).

Subtypes of aggression are commonly distinguished by the underlying function or motivation behind the behavior (Vitaro and Brendgen 2011). Reactive aggression is characterized by angry retaliatory behavior that occurs in response to perceived provocation or threat. Proactive aggression, on the other hand, refers to instrumental, goal-oriented, and offensive actions that do not require provocation and are motivated by anticipated rewards. Despite considerable statistical overlap, confirmatory factor analyses have consistently supported the distinction between reactive and proactive aggression (for a more complete review, see Vitaro and Brendgen 2011). Several investigations have also revealed that these subtypes of aggression are characterized by different patterns of social-information processing, which may have implications for their links to peer victimization. Specifically, reactive aggression is associated with the tendency to attribute hostile intent to peers’ behavior in ambiguous social situations, and proactive aggression is associated with the positive evaluation of aggression and its likely consequences, especially in the context of peer conflict (e.g., Dodge and Coie 1987).

A growing body of research indicates that whereas peer victimization is positively related to reactive aggression, it is negatively associated with, or unrelated to, proactive aggression. It is posited that victimized children may use reactive aggression as a defensive response and as a way to retaliate against hostile peer attacks (Lamarche et al. 2007). Corresponding to research examining the social-information processing deficits that characterize reactive aggression (e.g., Dodge and Coie 1987), victimized children tend to exhibit a hostile attribution bias (Camodeca and Goossens 2005). Thus, it follows that youth who experience victimization may come to view peers’ behavior as provocative and hostilely motivated, leading them to react with angry retaliatory behavior.

Additionally, children who exhibit reactive aggression may be targeted as victims because their attention problems, impulsivity, and hostile attitudes provoke frequent conflict and are irritating to their peers (Dodge et al. 1997). Reactively aggressive youth’s tendency to be rejected (e.g., Poulin and Boivin 2000) may leave them particularly vulnerable to victimization, as it reduces the likelihood that other children will intervene and stand up against the aggressor. Peers may also find it reinforcing to provoke these children given that reactive aggression is often associated with difficulties managing emotional expression (e.g., Marsee and Frick 2007). In fact, previous research suggests that youth who respond to peer provocation with hostility tend to reinforce their aggressors with dramatic emotional responses and exaggerated retaliatory behavior (Perry et al. 1990).

Conversely, some proactively aggressive youth possess qualities, such as leadership, a sense of humor, and popularity among peers (e.g., Dodge and Coie 1987), that are likely to prevent them from being targeted for peer victimization. Children who exhibit proactive aggression also tend to be non-submissive and affiliate with other proactively aggressive youth who may be capable of defending them or retaliating on their behalf (Poulin and Boivin 2000). Taken together, these characteristics may account for findings indicating that proactive aggression is unrelated to, or negatively associated with, experiences of victimization.

Previous Longitudinal Research

Consistent with the previously established patterns regarding general externalizing problems (Reijntjes et al. 2011), it is likely that the association between peer victimization and reactive aggression is reciprocal in nature, whereas proactive aggression may predict decreases in peer victimization over time. However, discrepant findings in the extant literature have precluded firm conclusions regarding the nature of these longitudinal relations.

Altogether, two of the three studies examining bidirectional associations have failed to find prospective links from peer victimization to reactive aggression in early childhood (Ostrov et al. 2014) and early adolescence (Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007). In contrast, evidence for this association has emerged in middle childhood among both boys and girls (Averdijk et al. 2016), although another investigation examining this unidirectional effect found that it was significant for boys only (Lamarche et al. 2007). More consistent support has emerged with regard to the path from reactive aggression to peer victimization across gender in early (Ostrov et al. 2014) and middle (Averdijk et al. 2016) childhood as well as in early adolescence for boys but not girls (Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007).

Mixed results have been reported regarding the longitudinal relations between peer victimization and proactive aggression, which appear to be specific to boys when evident. That is, proactive aggression has been shown to predict decreases in peer victimization among boys in early childhood (Ostrov et al. 2014) and early adolescence (Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007). Further, one study revealed that peer victimization predicted decreases in proactive aggression in early adolescence for boys only (Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007); in contrast, no prospective links between these variables have been documented in middle childhood (Lamarche et al. 2007; Averdijk et al. 2016).

This inconsistent pattern of findings in the literature may be due in part to methodological differences in the aforementioned studies’ designs. It is worth noting that the only investigation to document bidirectional associations between peer victimization and reactive aggression utilized child-reports of victimization (Averdijk et al. 2016), which are often regarded as the most valid measures given that they capture incidents occurring across diverse settings that others may be unaware of (see Fite et al. 2013; Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd 2002).

Moreover, no prior longitudinal studies have used teacher-reports of peer victimization; this is a notable omission in the literature considering that such instruments are quite useful for monitoring problem behaviors within the school context (Cullerton-Sen and Crick 2005). Teacher-reports are efficient, relatively nonintrusive, and cost-effective, and they provide both additive and unique information regarding children’s social interactions (Cullerton-Sen and Crick 2005; Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd 2002). Indeed, previous research has demonstrated that teacher-reports of peer victimization correspond to self- and peer-reports of peer victimization (Cullerton-Sen and Crick 2005; Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd 2002). Whereas two of the aforementioned studies utilized peer-reports of peer victimization (Lamarche et al. 2007; Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007), which are also based on daily interactions and observations, it has been argued that this method may reflect youth’s reputation and previously established status as a victim, thereby making it more resistant to change than child- or teacher-reports (Pouwels et al. 2016). Accordingly, the present research design utilized both child and teacher ratings of peer victimization in order to provide a test of the robustness of findings across informants. Given that teachers are reliable reporters, but may not always be aware of peer victimization (e.g., Vernberg et al. 1995), it was expected that the prospective links would be stronger when utilizing child-reports.

It also remains possible that the longitudinal relations between peer victimization and functions of aggression may differ according to whether they are measured within an academic year or across academic years. Whereas continuity in the classroom environment likely contributes to the stability of these associations, transitions into the subsequent grade level may provide the opportunity for children to redefine their position in the peer group, thereby reducing their involvement in victimization and aggression (Pouwels et al. 2016). As Dempsey et al. (2006) suggest, “in addition to altering children’s’ network of peer relations in the classroom, this transition could also separate children in victimizing relationships. Changes in the composition of the classroom allows for children to be re-evaluated by their new classmates as they grow and mature” (p. 274). Only one known previous study’s design, however, provides the opportunity to examine this proposition; significant effects were found over a 4-month period (i.e., February to May), but not over the subsequent 8-month period (i.e., May to February; Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007). Unfortunately, such comparisons across other investigations are confounded by the differing time periods between assessments (i.e., 4 months to 2 years; Averdijk et al. 2016; Lamarche et al. 2007; Ostrov et al. 2014). Thus, the current study employed a three-wave design in which the intervals between time points fell both within and across academic years in order to further evaluate whether these relations differ depending on when they are assessed.

Due to mixed findings in the extant literature, it is not yet clear whether the prospective links between peer victimization and reactive and proactive aggression differ according to gender. This question was further evaluated in the present study; still, it is important to note that the measure that was utilized emphasized physical acts of aggression, such that items referenced “physical force” and “fighting.” Previous research has shown that boys tend to exhibit higher levels of physical aggression than girls. In contrast, when aggressive, girls are more likely to engage in relational acts of aggression (e.g., gossip, rumor spreading, ostracism; see Ostrov and Godleski 2010). Further, Ostrov and Godleski (2010) have put forward a gender-linked model of aggression that suggests that physical aggression may be more strongly linked to psychosocial outcomes for boys and relational aggression may be more strongly linked to psychosocial outcomes for girls in early and middle childhood. Thus, it was anticipated that the observed associations in the current investigation would be stronger for boys than girls.

Finally, it may be that peer victimization contributes to an escalating cycle of reactive aggression over time. Reactively aggressive youth are likely to be victimized by their peers, and these experiences, in turn, may lead them to retaliate and engage in more reactive aggression during future encounters with peers. Correspondingly, it is likely reactive aggression contributes to an escalating cycle of peer victimization over time. Averdijk et al.’ (2016) findings provide some support for this latter notion, although it is not possible to determine whether reactive aggression uniquely contributed to the stability of peer victimization over the 3-year period since the indirect effect of overall problem behavior (i.e., reactive, proactive, and indirect aggression and symptoms of depression and anxiety) was examined. Considering the myriad of harmful outcomes associated with chronic patterns of both reactive aggression (e.g., Barker et al. 2006) and peer victimization (e.g., Biggs et al. 2010), additional work is needed to identify mechanisms that account for the stability of these problematic behaviors and experiences.

Current Study

The central aims of the current study were to address these gaps in the literature by further examining bidirectional associations between peer victimization and functions of aggression across informants (i.e., children and teachers) over a 1-year period, with attention to potential gender differences. The indirect effects of reactive aggression on the stability of peer victimization and peer victimization on the stability of reactive aggression were also evaluated.

Data collection occurred as part of a larger ongoing project focused on peer victimization during middle childhood. Prior cross-sectional findings from this work have demonstrated that elementary school-age children were most commonly victimized in locations where adult monitoring is limited (i.e., the playground followed by their home and neighborhood; Fite et al. 2013), child- and teacher-reports of relational victimization were more congruent than their reports of physical victimization (Williford et al. 2015), the effects of peer victimization on academic performance were not as detrimental at high levels of parental school involvement (Fite et al. 2014), and only physical aggression was uniquely associated with risk for substance use outcomes after controlling for both forms of aggression and peer victimization (Fite et al. 2016). Moreover, several recent longitudinal studies have revealed that high levels of anger regulation attenuated the link between peer victimization and physical aggression, whereas high levels of anger and sadness regulation exacerbated the association between peer victimization and relational aggression over a 6-month period (Cooley and Fite 2016), anxiety symptoms partially accounted for the relation between stressful life events and peer victimization over a 1-year period (Brown and Fite 2016), and symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder predicted higher levels of physical, but not relational, victimization over a 1.5-year period among children who reported engaging in moderate to high levels of physical activity, especially out of the school context (Mitchell et al. 2016). However, this is the first investigation from this larger project to examine the associations between peer victimization and functions of aggression.

Based on available theory and extant findings, it was hypothesized that (1) peer victimization would predict higher levels of reactive aggression, (2) reactive aggression would predict higher levels of peer victimization, (3) proactive aggression would predict lower levels of peer victimization, (4) reactive aggression would partially account for the stability of peer victimization, (5) peer victimization would partially account for the stability of reactive aggression, and (6) these prospective links would be stronger for boys than girls, stronger when utilizing child-reports, as compared to teacher-reports, of peer victimization, and stronger when examined within an academic year compared to across academic years.

Method

Participants

Participants included 97 boys and 101 girls between the ages of 8 and 10 (M = 8.77, SD = 0.72) from an elementary located in a small, rural Midwestern community in the United States (U.S.) and their homeroom teachers. All students in the third and fourth grades not receiving special education services were recruited for participation in the current study (n = 263). Caregiver consent was obtained during parent-teacher conferences and by sending letters home during the fall semester. Overall, 86% of families completed the consent form (n = 233), and permission was obtained for 77% of the eligible students to participate in the study at Times 1 and 2 (n = 203). Similar recruitment procedures were followed prior to data collection at Time 3. Homeroom teachers also provided written informed consent prior to completing study measures (Times 1 and 2 N = 12; Time 3 N = 11), with 100% participation throughout the course of the study.

At Time 1, data were missing for two students who declined participation, two students who were absent on the days of data collection, and one student who provided assent but did not complete the measure of interest in the current study. At Time 2, data were missing for one student who declined participation and two students who had moved out of the school district. At Time 3, data were missing for nine students whose parents declined consent, one student whose parents did not return the consent form, one student who declined participation, seven students who had moved out of the school district, and one student who was absent on the days of data collection. The 2.5% of students missing Time 1 data were excluded from the study due to analytic constraints. However, a series of independent samples t-tests indicated that the 1.5% of participants with missing data at Time 2 and the 9.6% of participants with missing data at Time 3 did not differ from participants with complete data on any study variables at Time 1, suggesting a representative longitudinal sample; accordingly, these participants were retained and analyses accounted for their missing data.

The final sample consisted of 198 children in the third (n = 107) and fourth grades (n = 91). School records indicated that the racial composition of the student body was predominantly Caucasian, with less than 10% of children identifying as a racial minority (4% African American, 2% Asian, 2% American Indian/Alaska Native, 1% Hispanic/Latino). Although information regarding students’ socioeconomic status was not available, approximately 40% of the children at the school were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

Measures

Peer Victimization

Exposure to peer victimization was assessed using both child- and teacher-reports. Children completed the Victimization of Self (VS) scale of the Peer Experiences Questionnaire (Dill et al. 2004). The VS scale consists of nine items assessing both physical (four items; e.g., “A kid hit, kicked, or pushed me in a mean way”) and relational (five items; e.g., “A kid told lies about me so other kids wouldn’t like me”) experiences of peer victimization. Children were asked to rate the frequency of such occurrences on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Never to 5 = Several Times a Week). The VS scale has previously demonstrated good psychometric properties in samples of elementary school-age youth (e.g., Dill et al. 2004).

Teachers completed a modified version of the Social Experience Questionnaire – Teacher Report (SEQ-T) for each student in the homeroom (Cullerton-Sen and Crick 2005). The SEQ-T consists of six items assessing both physical (three items; e.g., “Gets hit, kicked, punched by others”) and relational (three items; e.g., “Other kids tell rumors about them behind their backs”) experiences of peer victimization. Teachers were asked to rate the frequency of such occurrences on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Never to 5 = Almost Always). The modified SEQ-T has previously demonstrated good psychometric properties in samples of elementary school-age youth (e.g., Williford et al. 2015).

Overall scores were created separately for child- and teacher-reports at each time point by averaging across the nine items and six items, respectively. Both the VS scale (0.88, 0.91, 0.88) and the SEQ-T (0.71, 0.82, 0.88) demonstrated adequate internal consistency across all three waves of the current study. It has been suggested that child- and teacher-reports provide both overlapping and unique information regarding experiences of victimization (Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd 2002), and previous research has shown that they contribute unique information in the prediction of outcomes associated with peer victimization (e.g., Cullerton-Sen and Crick 2005). Therefore, models were estimated separately for child- and teacher-reports of peer victimization.

Functions of Aggression

Teachers reported on students’ levels of aggressive behavior using Dodge and Coie’s (1987) measure of reactive and proactive aggression, which consists of six items. Three items assess reactive aggression (e.g., “When the child has been teased or threatened, he/she gets angry easily and strikes back”), and three items assess proactive aggression (e.g., “The child uses physical force or threatens to use physical force in order to dominate other kids”). Teachers responded using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Never to 5 = Almost Always). This is a widely used measure for teacher ratings of aggressive behavior that has previously demonstrated good psychometric proprieties in samples of elementary school-age youth (e.g., Dodge and Coie 1987; Poulin and Boivin 2000). Mean scores were calculated for each function of aggression at each time point, such that higher scores indicated higher levels of aggressive behavior. The reactive (0.94, 0.94, 0.93) and proactive (0.73, 0.84, 0.86) aggression subscales demonstrated adequate internal consistency across all three waves of the current study.

Procedures

School administrators and the researchers’ Institutional Review Board provided approval for the study. Time 1 child-reported data collection occurred through class-wide group administration beginning approximately 12 weeks after the start of the fall semester of 2014. Students were asked to provide verbal assent prior to their participation; during data collection, a research assistant provided standardized instructions to the students and then read each questionnaire item aloud while additional trained research assistants circulated throughout the classroom to answer questions and assist students who had difficulty understanding particular items. No teachers or nonparticipating students were present in the rooms in order to facilitate accurate responding. Teachers were asked to complete a secure online survey for each of the students in their homeroom during the same month in which child-reported data were collected. Similar procedures were followed when data collection took place again approximately 6 months later in the spring semester (Time 2) in addition to 6 months later in the fall semester of the subsequent school year (Time 3). Children received a small prize (i.e., a mechanical pencil) and teachers were compensated $50 upon completion of their surveys at each time point.

Data Analytic Plan

Given that the participants were clustered into groups, with children nested within classrooms and teachers providing ratings for all of the students in their homeroom at each time point, data in the current study had a multilevel structure. It is important to note, however, that the clusters changed between Time 2 and Time 3, as the students transitioned across academic years into a new classroom in the subsequent grade level (i.e., the data were also cross-classified). Accordingly, the bidirectional associations between peer victimization and functions aggression were examined using a series of cross-classified multilevel cross-lagged models within Mplus statistical software (Version 7; Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012) using a Bayesian estimator. More specifically, model estimation was performed using the Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm and the Gibbs sampler (see Muthén and Asparouhov 2012). All analyses were conducted using non-informative priors, which do not make hypotheses about the expected findings and yield parameters that coincide with maximum likelihood estimates (Muthén and Asparouhov 2012; for a review of Bayesian estimation, see Zyphur and Oswald 2015).

As previously noted, the amount of missing data at Times 2 and 3 was 1.5% and 9.6%, respectively; in Bayesian analyses, a posterior distribution is estimated for each missing value using the Monte Carlo algorithm and the Gibbs sampler, and models produce asymptotically the same results as maximum likelihood estimation (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012). Initial inspection of the outcome variables revealed that the skewness and kurtosis fell below the recommended values of three and ten, indicating that non-normality of the data was not a concern (see Table 1).

A hierarchical approach was employed in building models. First, an empty means, random intercept model was estimated in order to assess the amount of variance in each variable that was accounted for at the classroom level (Model 1). Thus, the mean of each outcome (i.e., intercept) was allowed to randomly vary across the respective classrooms at each time point. A separate series of models were then estimated for each informant of peer victimization. The autoregressive and crossed paths were added to the model as fixed effects in order to evaluate stability paths and bidirectional associations (Model 2). Gender and grade level were also controlled for in these models to account for the previously documented gender differences in these associations (e.g., Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007) along with age differences in levels of aggression (see Vitaro and Brendgen 2011) and peer victimization (e.g., Rudolph et al. 2011). Next, gender moderation was examined for each wave of the model; thus, one model was estimated with interactions between gender and Time 1 variables predicting Time 2 variables (Model 3), and another was estimated with interactions between gender and Time 2 variables predicting Time 3 variables (Model 4). Significant interaction effects were probed when the models were conditioned to represent specific associations for boys and girls. Finally, a model was estimated that first evaluated the indirect effect of Time 2 peer victimization on the stability of reactive aggression from Time 1 to Time 3 (Model 5) and then evaluated the indirect effect of Time 2 reactive aggression on the stability of peer victimization from Time 1 to Time 3 (Model 6).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables are presented in Table 1. Of note, students reported a substantially higher prevalence of peer victimization than teachers at Time 1. That is, 73.2% of children endorsed having experienced at least one incident of peer victimization since the beginning of the school year, whereas teachers reported that only 19.2% of students had been victimized by their peers on at least one occasion. Moreover, teachers reported that 35.4% of students had engaged in at least one reactively aggressive act, and 18.7% of students had engaged in at least one proactively aggressive act at Time 1. Child- and teacher-reports were uncorrelated or modestly correlated within time across the study, sharing between 1% and 11% of their variance; in contrast, reactive and proactive aggression were strongly correlated within time across the study, sharing between 45% and 58% of their variance.

Cross-Classified Multilevel Cross-Lagged Models

The empty means, random intercept model revealed that between 3% and 37% (Mdn = 7%) of the variance in each variable across clusters and time points was explained at the classroom level, suggesting that multilevel analytic techniques were justified.

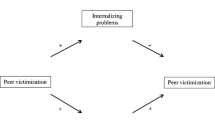

Child-Reported Peer Victimization

The control variables and cross-lagged paths were then added to the child-reported peer victimization model as fixed effects. With regard to the control variables, gender was positively associated with Time 2 peer victimization, μβ = 0.13, SD = 0.06, 95% CI [0.02, 0.23], such that girls were more likely than boys to experience increases in peer victimization from the fall to the spring semester; however, no other gender or grade level effects were evident. Results of the autoregressive and crossed paths are depicted in Fig. 1, and results of the models examining gender as a moderator of the crossed paths are presented in Table 2. As shown, a significant Time 2 peer victimization x gender interaction emerged in the prediction of Time 3 proactive aggression, and the inclusion of this fixed effect accounted for an additional 4% of the residual variance. Follow-up analyses indicated that experiences of victimization predicted subsequent decreases in proactive aggression among boys, μβ = −0.21, SD = 0.07, 95% CI [−0.34, −0.05], but not girls, μβ = 0.10, SD = 0.07, 95% CI [−0.06, 0.22]. Finally, a significant indirect effect emerged, indicating the peer victimization partially accounted for the stability of reactive aggression from Time 1 to Time 3, indirect effect = 0.04, SD = 0.02, 95% CI [0.00, 0.10].Footnote 1 There was, however, a significant direct effect remaining of prior victimization on subsequent victimization, μβ = 0.25, SD = 0.07, 95% CI [0.12, 0.38]. In contrast, the indirect effect of Time 2 reactive aggression on the stability of peer victimization from Time 1 to Time 3 was not significant, indirect effect = 0.01, SD = 0.01, 95% CI [0.00, 0.04].

Cross-classified multilevel cross-lagged models of the bidirectional associations between child-reported peer victimization and functions of aggression. Note. Standardized posterior mean estimates are reported outside parentheses and standard deviations are reported inside parentheses. Solid lines are statistically significant paths in which the 95% credibility intervals did not contain zero; dotted lines are estimated but nonsignificant paths. Asterisks denote paths that were significantly moderated by gender in subsequent models. Gender and grade level were included as control variables for all endogenous variables, but paths are not included in the figure for ease of communication. Additionally, exogenous variables were allowed to covary and residual covariances within each wave were estimated; however, these covariances are not shown for clarity purposes. The pseudo-R 2 values represent the proportion reduction in the residual variance of the outcome accounted for by the inclusion of fixed effects in each model

Teacher-Reported Peer Victimization

As before, when the control variables and cross-lagged paths were added to the teacher-reported model as fixed effects, gender was positively associated with Time 2 peer victimization, μβ = 0.10, SD = 0.05, 95% CI [0.00, 0.20]1; however, no other gender or grade level effects were evident. Results of the autoregressive and crossed paths are depicted in Fig. 2, and results of the models examining gender as a moderator of the crossed paths are presented in Table 3. As shown, significant Time 1 reactive aggression x gender and Time 1 proactive aggression x gender interactions emerged in the prediction of Time 2 peer victimization, and the inclusion of these fixed effects accounted for an additional 6% of the residual variance. Follow-up analyses indicated that reactive aggression predicted subsequent increases in peer victimization among boys, μβ = 0.31, SD = 0.07, 95% CI [0.19, 0.46], but not girls, μβ = 0.03, SD = 0.11, 95% CI [−0.15, 0.27]. Conversely, proactive aggression predicted subsequent decreases in peer victimization among boys, μβ = −0.14, SD = 0.06, 95% CI [−0.25, −0.02], and subsequent increases in peer victimization among girls, μβ = 0.30, SD = 0.06, 95% CI [0.16, 0.41]. Given that none of the crossed paths from peer victimization to reactive aggression were significant, indirect effects were not examined.

Cross-classified multilevel cross-lagged models of the bidirectional associations between teacher-reported peer victimization and functions of aggression. Note. Standardized posterior mean estimates are reported outside parentheses and standard deviations are reported inside parentheses. Solid lines are statistically significant paths in which the 95% credibility intervals did not contain zero; dotted lines are estimated but nonsignificant paths. Asterisks denote paths that were significantly moderated by gender in subsequent models. Gender and grade level were included as control variables for all endogenous variables, but paths are not included in the figure for ease of communication. Additionally, exogenous variables were allowed to covary and residual covariances within each wave were estimated; however, these covariances are not shown for clarity purposes. The pseudo-R 2 values represent the proportion reduction in the residual variance of the outcome accounted for by the inclusion of fixed effects in each model

Discussion

The current three-wave longitudinal study examined bidirectional relations between peer victimization and functions of aggression over a 1-year period in middle childhood. Consistent with expectations, results indicated that child-reports, but not teacher-reports, of peer victimization predicted subsequent increases in reactive aggression both within and across academic years (i.e., over 6-month intervals) after controlling for prior levels of both functions of aggressive behavior. Similar findings have been reported over 1-year intervals using self- (Averdijk et al. 2016) and peer-reports (Lamarche et al. 2007) of peer victimization in samples of elementary school-age youth; however, other studies have failed to find prospective links from peer victimization to reactive aggression over 4-month intervals in early childhood using observations of peer victimization (Ostrov et al. 2014) or over 4- and 8-month intervals in early adolescence using peer-reports of peer victimization (Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007). It is thought that, over time, children may come to use reactive aggression as a defensive response in order to protect themselves and as a method of retaliation against peer provocation (Lamarche et al. 2007). Victimized youth may also increasingly view peers’ behavior as provocative and hostilely motivated, even in ambiguous situations, which may lead them to react with angry retaliatory behavior (Camodeca and Goossens 2005). Taking the current and previous findings together, it appears that this progression is especially likely to occur during middle childhood.

Still, the observed discrepancy in effects across child- and teacher-reports of peer victimization in the current study is noteworthy. Although teachers are reliable and valid informants who provide additive and unique information regarding children’s social interactions (Cullerton-Sen and Crick 2005; Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd 2002) their reports are limited to daily interactions and observations within the school context (Pouwels et al. 2016). Teachers may not always be aware of peer victimization, as many incidents occur outside of the school context (e.g., on the bus, in the neighborhood) or in locations at school where monitoring is limited (e.g., on the playground; Fite et al. 2013). Previous research has also revealed that students tend to not report their experiences of victimization to teachers or other adults (e.g., Vernberg et al. 1995). Thus, child-reports are regarded as the most valid measures since they provide a broader account of incidents that have occurred across diverse settings (Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd 2002). In fact, approximately 3.8 times as many students were identified as having experienced at least one incident of peer victimization since the beginning of the school year using child-reports, as compared to teacher-reports, at the onset of the current study.

Support was also found for the hypothesis that reactive aggression would predict higher levels of peer victimization over time. Further, results were robust both within and across informants and academic years after controlling for prior levels proactive aggression and peer victimization. The current study contributes to a growing body of research demonstrating that youth who engage in reactively aggressive behavior are at increased risk for victimization by their peers across developmental periods, including early (Ostrov et al. 2014) and middle (Averdijk et al. 2016) childhood as well as early adolescence (Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007). This may be due in part to the disruptive behaviors they exhibit that aggravate their peers (Dodge et al. 1997) and their social isolation (Poulin and Boivin 2000), which leaves them vulnerable to peer attacks. Given that reactively aggressive youth may have difficulties regulating their emotions (e.g., Marsee and Frick 2007), the dramatic emotional responses and exaggerated retaliatory behavior such experiences elicit may also encourage peers to further provoke and victimize these children (Perry et al. 1990).

Interestingly, only reactively aggressive boys exhibited increases in peer victimization within an academic year when teacher-reports were utilized in the current study. This pattern is similar to prior findings from an early adolescent sample (Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007), and it suggests that the use of reactive aggression may place boys at unique risk for peer victimization within the immediate school context. However, the effect of reactive aggression on peer victimization did not differ between boys and girls across academic years using teacher-reports or between or across academic years using child-reports. Thus, reactive aggression may increase all youth’s risk for peer victimization across diverse settings as well as within the school context following transitions into the subsequent grade level, with changes in classroom social dynamics taking place (Pouwels et al. 2016).

Also consistent with expectations and previous research (Ostrov et al. 2014; Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007), the use of proactive aggression predicted decreases in peer victimization over the course of an academic year for boys only; again, this pattern was specific to teacher-reports of peer victimization and therefore likely pertains to boys’ peer interactions within the immediate school context. Boys who engage in proactive aggression may exhibit characteristics (e.g., popularity with peers) and have social relationships (e.g., with other proactively aggressive youth; Poulin and Boivin 2000) that make them poor targets for victimization. In contrast, child-reports of peer victimization predicted decreases in proactive aggression across academic years among boys but not girls in the current study. Although unexpected, this pattern also supports prior findings (Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007) and suggests that boys who experience peer victimization may be less likely to positively evaluate aggression and its consequences in the context of peer conflict, thereby leading them to exhibit lower levels of strategic, goal-oriented aggression during the subsequent school year.

Surprisingly, proactive aggression was found to predict increases in teacher-reported peer victimization over the course of an academic year among girls. As previously noted, the current study utilized a measure that emphasized physical acts of aggression (Dodge and Coie 1987). In contrast, relational aggression is the modal form of aggression for girls (Ostrov and Godleski 2010), and it has been suggested that children who exhibit gender nonnormative forms of aggression are likely to elicit particularly negative reactions from peers (Crick and Dodge 1994). Thus, it may be that girls who engage in proactive aggression that is physical in nature are at increased risk for being targeted for peer victimization within the school context.

Despite the observed reciprocal relations, reactive aggression did not account for the stability of child-reported peer victimization over a 1-year period in the current study. This finding indicates that reactive aggression alone does not contribute to an escalating cycle of peer victimization over time; in fact, previous work has shown that overall problem behavior mediates the stability of peer victimization (Averdijk et al. 2016). Conversely, child-reported peer victimization was found to partially account for the stability of reactive aggression over a 1-year period, although there was a strong remaining direct effect of prior on subsequent reactive aggression. It appears that reactively aggressive youth’s tendency to be victimized by their peers may lead to greater engagement in reactive aggression over time, which is concerning given that chronic patterns of reactive aggression are associated with later involvement in delinquent lifestyles (e.g., affiliation with gangs; Barker et al. 2006).

Limitations and Future Directions

Findings from the current study should be evaluated while taking into consideration several methodological limitations. Despite the multi-informant approach to peer victimization, only teacher ratings of aggressive behavior were obtained in this investigation. Previous research has demonstrated that teachers are reliable and valid informants of child aggression (e.g., Dodge and Coie 1987); however, their reports are limited to daily interactions and observations within the school context (Pouwels et al. 2016). Future research endeavors should therefore incorporate parent- and peer-reports along with teacher-reports in order to provide an assessment of aggressive behavior that spans diverse settings (e.g., home, school, and community).

Prior work has also demonstrated that associations may vary according to both forms and functions of aggression (e.g., Ostrov et al. 2014). Although it was not possible to completely disentangle forms from functions of aggression with the measure utilized in this study (Dodge and Coie 1987), it primarily emphasized physical acts of aggression, which represents a significant limitation with regard to the current gender analyses. Considering the gender-linked model of aggression (Ostrov and Godleski 2010), reactive and proactive relational aggression may be more strongly related to peer victimization among girls than boys. Additional work is therefore needed to examine these associations and extend previous findings beyond the early childhood years (Ostrov et al. 2014).

Further, the interval under investigation in the current study was relatively brief. Importantly, prospective associations from peer victimization to reactive aggression have only been documented in middle childhood to date (Averdijk et al. 2016; Lamarche et al. 2007), primarily using child-reports of peer victimization. Taking into account the current results, it is unknown whether other discrepant findings regarding this pathway (Ostrov et al. 2014; Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007) are due to the developmental period under investigation (i.e., early childhood and early adolescence versus middle childhood) or due to differences in the informant of peer victimization. Additional work examining these relations from childhood to adolescence using a multi-informant approach would be useful for determining how peer victimization and functions of aggression reciprocally influence each other across development. Future research evaluating the mechanisms by which peer victimization and functions of aggression are prospectively related (e.g., emotion dysregulation, peer rejection) will also be useful for further developing prevention and intervention efforts.

Finally, the generalizability of the current findings may be limited taking into account the predominantly Caucasian student body of the school where this research was conducted. Still, this study extends previous research conducted with samples of youth from urban and suburban areas of the Northeastern U.S. (Ostrov et al. 2014), Canada (Lamarche et al. 2007), Switzerland (Averdijk et al. 2016), and Finland (Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007) to a sample of children from a small, rural Midwestern community in the U.S. Of note, rural populations represent a substantial proportion of the U.S. and countries throughout the world. Although similar family, school, and peer risk factors for aggressive behavior have been observed among both rural and urban youth (Swaim et al. 2006), Huesmann and Guerra (1997) note that the socialization processes of children living in high-risk environments may contribute to normative beliefs supporting aggression and predict higher levels of aggressive behavior among peers. Thus, future investigations should continue to examine these bidirectional associations in ethnically, geographically, and socioeconomically, diverse samples.

Implications for Practice

The present findings contribute to a growing body of research indicating that peer victimization increases youth’s risk for engaging in reactive aggression (Averdijk et al. 2016; Lamarche et al. 2007), and in turn, reactive aggression predicts higher rates of peer victimization over time (Averdijk et al. 2016; Ostrov et al. 2014; Salmivalli and Helteenvuori 2007). Whereas these bidirectional associations were robust within and across academic years, they differed according to informants in the current study. More specifically, teachers were able to identify reactively aggressive youth who were likely to experience subsequent increases in peer victimization, but they appeared to under-identify children experiencing peer victimization who were at risk for exhibiting higher levels of reactive aggression during future interactions with peers. The fact that teachers are unaware of many victimization incidents may partially account for the tendency of victimized youth to become increasingly aggressive, as they are likely left to their own accord to handle these problematic interactions (Williford et al. 2015). It is therefore recommended that intervention (and research) efforts rely primarily on children’s reports of peer victimization, but also incorporate trainings to help teachers better recognize and effectively respond to peer victimization within the school context.

Importantly, current and previous findings highlight the need to target reactively aggressive behavior in order to reduce youth’s risk for problematic peer interactions during middle childhood. Cognitive behavioral interventions may represent one avenue for reducing reactive aggression, thereby attenuating its association with peer victimization and preventing the negative long-term psychosocial sequelae linked to these behaviors (e.g., Reijntjes et al. 2010, 2011; Vitaro and Brendgen 2011). Merk et al. (2005) recommend that treatment for reactively aggressive youth focus on reducing hostile attribution biases, social skills training, increasing positive interactions with peers, improving anger control, and parent management training. Taking into account the finding that peer victimization contributes to the stability of reactive aggression over time, a particular emphasis on developing adaptive coping strategies in response to hostile peer encounters (e.g., conflict resolution, advice seeking; Kochenderfer-Ladd 2004) also appears to be indicated. The Coping Power Program has been identified as a “well-established” intervention for children exhibiting aggressive behavior during the late elementary school years (i.e., fourth- through sixth-grade); this program has been adapted for use in culturally diverse populations, and one recent randomized-controlled trial demonstrated significant reductions in teacher-rated externalizing behavior problems, proactive and reactive aggression, impulsivity traits, and callous-unemotional traits by the end of the intervention and at 3-year follow-up (Lochman et al. 2014). Evaluation of this and other programs for the prevention of peer victimization is in need of investigation.

Notes

Please note that the preceding 95% credibility interval did not contain zero, but is reported to two decimal places in text.

References

Averdijk, M., Malti, T., Eisner, M., Ribeaud, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2016). A vicious cycle of peer victimization? Problem behavior mediates stability in peer victimization over time. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 2, 162–181. doi:10.1007/s40865-016-0024-7.

Barker, E. D., Tremblay, R. E., Nagin, D. S., Vitaro, F., & Lacourse, E. (2006). Development of male proactive and reactive physical aggression during adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 783–790. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01585.x.

Biggs, B. K., Vernberg, E., Little, T. D., Dill, E. J., Fonagy, P., & Twemlow, S. W. (2010). Peer victimization trajectories and their association with children’s affect in late elementary school. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 34, 136–146. doi:10.1177/0165025409348560.

Brown, S., & Fite, P. J. (2016). Stressful life events predict peer victimization: does anxiety account for this link? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 2616–2625. doi:10.1007/s10826-016-0428-3.

Camodeca, M., & Goossens, F. A. (2005). Aggression, social cognitions, anger and sadness in bullies and victims. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 186–197. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00347.x.

Cooley, J. L., & Fite, P. J. (2016). Peer victimization and forms of aggression during middle childhood: the role of emotion regulation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 535–546. doi:10.1007/s10802-015-0051-6.

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information- processing mechanisms in children's social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 74–101. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74.

Cullerton-Sen, C., & Crick, N. R. (2005). Understanding the effects of physical and relational victimization: the utility of multiple perspectives in predicting social-emotional adjustment. School Psychology Review, 34, 147–160 Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/publications/spr/abstract.aspx?ID=1767.

Dempsey, J. P., Fireman, G. D., & Wang, E. (2006). Transitioning out of peer victimization in school children: gender and behavioral characteristics. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 28, 273–282. doi:10.1007/s10862-005-9014-5.

Dill, E. J., Vernberg, E. M., Fonagy, P., Twemlow, S. W., & Gamm, B. K. (2004). Negative affect in victimized children: the roles of social withdrawal, peer rejection, and attitudes towards bullying. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 159–173. doi:10.1023/B:JACP.0000019768.31348.81.

Dodge, K. A., & Coie, J. D. (1987). Social-information processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 1146–1158. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1146.

Dodge, K. A., Lochman, J. E., Harnish, J., Bates, J., & Pettit, G. (1997). Reactive and proactive aggression in school children and psychiatrically impaired chronically assaultive youth. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 37–51. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.106.1.37.

Fite, P. J., Williford, A., Cooley, J. L., DePaolis, K., Rubens, S. L., & Vernberg, E. M. (2013). Patterns of victimization locations in elementary school children: effects of grade level and gender. Child and Youth Care Forum, 42, 585–597. doi:10.1007/s10566-013-9219-9.

Fite, P. J., Cooley, J. L., Williford, A., Frazer, A., & DiPierro, M. (2014). Parental school involvement as a moderator of the association between peer victimization and academic performance. Children and Youth Services Review, 44, 25–32. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.05.014.

Fite, P. J., Gabrielli, J., Cooley, J. L., Rubens, S. L., Pederson, C. A., & Vernberg, E. M. (2016). Associations between physical and relational forms of peer aggression and victimization and risk for substance use among elementary school-age youth. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 25, 1–10. doi:10.1080/1067828X.2013.872589.

Huesmann, L. R., & Guerra, N. G. (1997). Children’s normative beliefs about aggression and aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 408–419. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.2.408.

Kochenderfer-Ladd, B. (2004). Peer victimization: the role of emotions in adaptive and maladaptive coping. Social Development, 13, 329–349. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2004.00271.x.

Ladd, G. W., & Kochenderfer-Ladd, B. (2002). Identifying victims of peer aggression from early to middle childhood: Analysis of cross-informant data for concordance, estimation of relational adjustment, prevalence of victimization, and characteristics of identified victims. Psychological Assessment, 14, 74–96. doi:10.1037/1040–3590.14.1.74.

Lamarche, V., Brendgen, M., Boivin, M., Vitaro, F., Dionne, G., & Perusse, D. (2007). Do friends’ characteristics moderate the prospective links between peer victimization and reactive and proactive aggression? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 665–680. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9122-7.

Lochman, J. E., Wells, K. C., Qu, L., & Chen, L. (2014). Three-year follow-up of coping power intervention effects: evidence of neighborhood moderation? Prevention Science, 14, 364–376. doi:10.1007/s11121-012-0295-0.

Mahady Wilton, M. M., Craig, W. M., & Pepler, D. J. (2000). Emotional regulations and display in classroom victims of bullying: characteristic expressions of affect, coping styles and relevant contextual factors. Social Development, 9, 226–244. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00121.

Marsee, M. A., & Frick, P. J. (2007). Exploring the cognitive and emotional correlates to proactive and reactive aggression in a sample of detained girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 969–981. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9147-y.

Merk, W., Orobio de Castro, B., Koops, W., & Matthys, W. (2005). The distinction between reactive and proactive aggression: utility for theory, diagnosis, and treatment? European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 2, 197–220. doi:10.1080/17405620444000300.

Mitchell, T. B., Cooley, J. L., Evans, S. C., & Fite, P. J. (2016). The moderating effect of physical activity on the association between ADHD symptoms and peer victimization in middle childhood. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 47, 871–882. doi:10.1007/s10578-015-0618-z.

Muthén, B., & Asparouhov, T. (2012). Bayesian structural equation modeling: a more flexible representation of substantive theory. Psychological Methods, 17, 313–335. doi:10.1037/a0026802.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2012). Mplus User's Guide (Seventh ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Ostrov, J. M., & Godleski, S. A. (2010). Toward an integrated gender-linked model of aggression subtypes in early and middle childhood. Psychological Review, 117, 233–242. doi:10.1037/a0018070.

Ostrov, J. M., Kamper, K. E., Hart, E. J., Godleski, S. A., & Blakely-McClure, S. J. (2014). A gender-balanced approach to the study of peer victimization and aggression subtypes in early childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 26, 575–587. doi:10.1017/S0954579414000248.

Perry, D. G., Williard, J. C., & Perry, L. C. (1990). Peers’ perceptions of the consequences that victimized children provide aggressors. Child Development, 61, 1310–1325. doi:10.2307/1130744.

Poulin, F., & Boivin, M. (2000). Reactive and proactive aggression: evidence of a two-factor model. Psychological Assessment, 12, 115–122. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.12.2.115.

Pouwels, J. L., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2013). Correlates and outcomes associated with aggression and victimization among elementary-school children in a low-income urban context. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 190–205. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9875-3.

Pouwels, J. L., Souren, P. M., Lansu, T. A. M., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2016). Stability of peer victimization: a meta-analysis of longitudinal research. Developmental Review, 40, 1–24. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2016.01.001.

Reijntjes, A., Kamphuis, J. H., Prinzie, P., & Telch, M. J. (2010). Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(4), 244–252. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009.

Reijntjes, A., Kamphuis, J. H., Prinzie, P., Boelen, P. A., van der Schoot, M., & Telch, M. J. (2011). Prospective linkages between peer victimization and externalizing problems in children: a meta-analysis. Aggressive Behavior, 37, 215–222. doi:10.1002/ab.20374.

Rudolph, K. D., Troop-Gordon, W., Hessel, E. T., & Schmidt, J. D. (2011). A latent growth curve analysis of early and increasing peer victimization as predictors of mental health across elementary school. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40, 111–122. doi:10.1080/15374416.2011.533413.

Salmivalli, C., & Helteenvuori, T. (2007). Reactive, but not proactive aggression predicts victimization among boys. Aggressive Behavior, 33, 198–206. doi:10.1002/ab.20210.

Swaim, R. C., Henry, K. L., & Kelly, K. (2006). Predictors of aggressive behaviors among rural middle school youth. Journal of Primary Prevention, 27, 229–243. doi:10.1007/s10935-006-0031-2.

Vernberg, E. M., Ewell, K. K., Beery, S. H., Freeman, C. M., & Abwender, D. A. (1995). Aversive exchanges with peers and adjustment during early adolescence: Is disclosure helpful. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 26, 43–56. doi:10.1007/BF02353229.

Vitaro, F., & Brendgen, M. (2011). Subtypes of aggressive behaviors: etiologies, development, and consequences. In T. Bliesner, A. Beelman, & M. Stemmler (Eds.), Antisocial behavior and crime: contributions of theory and evaluation research in prevention and intervention. Goettingen, Germany: Hogrefe.

Williford, A., Fite, P. J., & Cooley, J. L. (2015). Student-teacher congruence in reported rates of physical and relational victimization among elementary school-age children: the moderating role of gender and age. Journal of School Violence, 14, 177–195. doi:10.1080/15388220.2014.895943.

Zyphur, M. J., & Oswald, F. L. (2015). Bayesian estimation and inference: a user’s guide. Journal of Management, 41, 390–420. doi:10.1177/0149206313501200.

Acknowledgements

The research described in this paper was supported by the University of Kansas and by a Fellowship from the American Psychological Foundation awarded to the first author. We would like to thank the students, teachers, and school administrators whose continued participation in our project made this study possible. We are also appreciative of the other members of the KU Child Behavior Lab for their assistance throughout the data collection process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cooley, J.L., Fite, P.J. & Pederson, C.A. Bidirectional Associations between Peer Victimization and Functions of Aggression in Middle Childhood: Further Evaluation across Informants and Academic Years. J Abnorm Child Psychol 46, 99–111 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0283-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0283-8