Abstract

Parent training (PT) delivered as a guided self-help intervention may be a cost- and time-effective intervention in the treatment of children with externalizing disorders. In face-to-face PT, parenting strategies have repeatedly been identified as mediating mechanisms for the decrease of children’s problem behavior. Few studies have examined possible mediating effects in guided self-help interventions for parents. The present study aimed to investigate possible mediating variables of a behaviorally oriented guided self-help program for parents of children with externalizing problems compared to a nondirective intervention in a clinical sample. A sample of 110 parents of children with externalizing disorders (80 % boys) were randomized to either a behaviorally oriented or a nondirective guided self-help program. Four putative mediating variables were examined simultaneously in a multiple mediation model using structural equation modelling. The outcomes were child symptoms of ADHD and ODD as well as child externalizing problems, assessed at posttreatment. Analyses showed a significant indirect effect for dysfunctional parental attributions in favor of the group receiving the behavioral program, and significant effects of the behavioral program on positive and negative parenting and parental self-efficacy, compared to the nondirective intervention. Our results indicate that a decrease of dysfunctional parental attributions leads to a decrease of child externalizing problems when parents take part in a behaviorally oriented guided self-help program. However, none of the putative mediating variables could explain the decrease in child externalizing behavior problems in the nondirective group. A change in dysfunctional parental attributions should be considered as a possible mediator in the context of PT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Externalizing disorders are among the most common mental disorders in children worldwide (Carter 2010), and include attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and conduct disorder (CD). ADHD is characterized by inattention and/or hyperactive/impulsive behavior (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Children with CD show a persistent pattern of aggressive and antisocial behavior as well as serious violations of rules. ODD essentially consists of a pattern of angry/irritable mood, temper tantrums, and argumentative/defiant behavior, but without severe aggressive or antisocial behavior (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Parent training (PT) is effective in reducing externalizing behavior problems of children, with moderate to large effect sizes (e.g., Corcoran and Dattalo 2006; Eyberg et al. 2008; Fabiano et al. 2009; Farmer et al. 2002; Kaminski et al. 2008; Thomas and Zimmer-Gembeck 2007). There is also strong evidence for positive effects of PT on parental practices as well as parental attitudes towards and perceptions of parenting (e.g., Cedar and Levant 1990; de Graaf et al. 2008). The goal of behaviorally oriented PT is to establish a shift in the social contingencies of a child’s behavior to increase the probability for desired behavior through positive reinforcement, and to decrease the probability for undesired behavior by ignoring or punishing it. In contrast, nonbehavioral PT focuses on the modification of processes in parent-child interactions, such as communication or joint problem solving (Lundahl et al. 2006). According to a meta-analysis on PT for disruptive child behavior (Lundahl et al. 2006), the effects of behavioral versus nonbehavioral PT did not differ for child or parent outcomes, although the studies examining nonbehavioral PT were based on nonclinical samples. For the treatment of children with clinically referred externalizing disorder, the authors suggested using behavioral PT because of the broader evidence base available (Lundahl et al. 2006). However, there may be several barriers preventing parental participation in PT; these include personal reasons or lack of financial resources, such as the need for child care, transportation costs, long journeys, or work schedules (O’Brien and Daley 2011).

Self-help interventions may reduce the gap in parental participation in PT and are defined as therapeutic interventions delivered as written materials (i.e., bibliotherapy) or in a multimedia format (O’Brien and Daley 2011). The contents of the self-help program can be applied by parents at home at a convenient time and at their own pace. Self-help interventions can be used to reach families living in rural areas and those with limited financial resources or time constraints (Kierfeld et al. 2013). They are also probably more cost-effective than traditional interventions even though a precise cost-benefit assessment has not yet been conducted (O’Brien and Daley 2011).

The differing types of self-help interventions can be differentiated by the extent of contact between the participant and therapist. Self-administered treatments take place without any therapeutic contact, whereas guided self-help interventions have minimal supplementary contact with a therapist, which is generally provided remotely via telephone calls or by mail (Glasgow and Rosen 1978). Lately, in accordance with technological development, an increase of technology assisted self-help interventions via internet or computer programs has occurred (e.g., Enebrink et al. 2012). Therapist-administered programs involve regular meetings with a therapist that focus on elaborating the contents of the self-help material (Glasgow and Rosen 1978).

Several studies demonstrated the effectiveness of PT provided as self-help interventions for parents of children with ADHD (Daley and O’Brien 2013), ODD and discipline problems (Lavigne et al. 2008; Markie-Dadds and Sanders 2006; Reid et al. 2013) or both (McGrath et al. 2011; for reviews see also Elgar and McGrath 2003; Montgomery et al. 2006; O’Brien and Daley 2011). The effects of a mere self-administered intervention seem to be enhanced by additional telephone contacts (Markie-Dadds and Sanders 2006). In a meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials, self-help interventions for parents of children with externalizing behavior problems were compared with routine care or waitlist control groups (Tarver et al. 2014). The results showed large effects on the reduction of child externalizing symptoms reported by parents, large effects on the increase of parental self-efficacy, and moderate effects on the reduction of dysfunctional parental behaviors (Tarver et al. 2014). There were no differences in treatment effects when the interventions were delivered as self-directed versus face-to-face with a therapist (Lundahl et al. 2006; Tarver et al. 2014). Another meta-analysis described medium effects of web-based parenting programs on child and parent outcomes, some of these programs are adaptations of well-established parenting interventions (Nieuwboer et al. 2013).

In a randomized controlled trial in Germany, a telephone-assisted self-administered parenting program using the German self-help book Wackelpeter & Trotzkopf (Döpfner et al. 2011) was shown to be effective in reducing parent-reported child externalizing behavior problems and dysfunctional parenting practices (Kierfeld et al. 2013), with the treatment effects maintained at 1-year follow-up (Ise et al. 2014). Furthermore, using a new edition of the program, there was some indication that the treatment effects are maintained under routine care conditions (Mokros et al. 2015).

The effectiveness of an intervention may be improved by identifying potential mediators of the change caused by the intervention (Kraemer et al. 2002). Mediating variables can be defined as the “characteristics of the individual that are changed by the treatment and that, in turn, produce change in the outcome of interest” (Whisman 1993, p. 248). Because PT aims to change parenting behavior in order to change children’s symptoms, we can theorize that variables associated with parenting could be possible mediators of the intervention. To our knowledge, only one study to date has addressed the question of mediating variables in behaviorally oriented guided self-help for parents of children with externalizing disorders (Kling et al. 2010). Those researchers found that improvement in child conduct was mediated by an improvement in positive parenting strategies and a reduction in negative parenting strategies (Kling et al. 2010). Similarly, several studies of behaviorally based PT delivered in a face-to-face format showed the effects were mediated by improvements in parenting practices (e.g., Beauchaine et al. 2005; Gardner et al. 2006; Hagen et al. 2011; Hanisch et al. 2014; Hektner et al. 2014). However, findings on the significance of positive and negative parenting practices have been inconclusive. Some researchers found that only positive parenting and not negative parenting had a mediating effect (Gardner et al. 2010), whereas others found that negative parenting mediated the treatment effect (Fossum et al. 2009). In addition, several studies have shown a mediating role of parental self-efficacy with regards to a positive change in parenting practices during the course of preventive PT (Dekovic et al. 2010; McTaggart and Sanders 2007). To our knowledge, there have been no mediation analyses of nonbehavioral PT to date. From a meta-analysis investigating the effects of Parent Effectiveness Training (PET; Gordon 1970), which can be described as a form of nondirective supportive PT, it is possible to consider both parenting behavior and parental attitudes towards parenting as potential mediating variables (Cedar and Levant 1990). So far, mediation analyses of behaviorally oriented PT have only considered reductions of child conduct problems or externalizing symptoms in general, and have not specifically examined reductions of ADHD symptoms.

Dysfunctional parental responsibility attributions may potentially mediate the effects of parent guided self-help for children’s externalizing problems. Dysfunctional parental responsibility attributions are defined as parents’ explanations of the cause of their children’s problem behavior regarding hostile or harmful intent (Snarr et al. 2009). Several behaviorally oriented PT interventions address the modification of parental attributions for their children’s behavior problems, by using psychoeducation or the development of an explanatory model for child behavior problems. Nondirective PT aims to enhance acceptance of a child’s needs by teaching the parents to take the child’s perspective, which can also be considered as an alteration of parental attributions. Several studies have demonstrated a significant relationship between dysfunctional parental responsibility attributions and externalizing behavioral problems (e.g., Halligan et al. 2007; Nix et al. 1999; Wilson et al. 2006), although the direction of causality has not yet been identified and has been presumed to be of a reciprocal nature (Johnston et al. 2009). In a review, Johnston and Ohan (2005) highlight the important role of parental attributions in the context of externalizing child behavior problems and parenting practices. Parental attributions also relate to an enhanced risk for child abuse (Montes et al. 2001). It has been shown that the effects of a preventive intervention for parents at risk for child abuse could be enhanced by additional interventions that explicitly targeted the alteration of parental cognitions including causal attributions for parents’ child’s behavior (Bugental et al. 2002). Furthermore, parental attributions can affect their engagement in PT and, thus, the success of the intervention (Morrissey-Kane and Prinz 1999).

From this research, the present study aimed to compare the mediating mechanisms in two different PT conditions, conducted as a guided self-help program for parents of children with externalizing behavior problems. We examined whether the reduction of children’s externalizing problem behaviors can be attributed to one or more of the following potential mediators: positive parenting practices, negative parenting practices, parental self-efficacy, and/or dysfunctional parental responsibility attributions. We compared a behaviorally oriented program with a nondirective supportive program, assuming that both interventions lead to a reduction in child externalizing behavior, but possibly through differing mediating mechanisms due to the different treatment techniques used. This is the first study to compare mechanisms of change in two different PT approaches and to analyze potential mediating mechanisms of guided self-help programs for externalizing or conduct disorders in Germany. Furthermore, our analyses are the first to examine the possible mediating mechanisms of effects on ADHD symptoms as an outcome measure, and to investigate dysfunctional parenting responsibility attributions as a potential mediator of the effects of PT.

Methods

Participants

Participating parents were enrolled from across Germany mostly by pediatricians, child and adolescent psychiatrists, and psychologists. Families were included if the target child showed symptoms of ADHD or ODD that met the diagnostic criteria of DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 2000) as determined from a semistructured clinical interview with the parent during the first telephone call. To be eligible for inclusion, the target child also had to be aged 4 to 11 years, show no signs of autism spectrum disorder (assessed by a short screening interview with the parent by telephone, and from the information provided on the study registration form), and have an IQ in the normal range (determined from the clinical evaluation of the enrolling doctor or psychologist). Also, there had to be no indication for more intense treatment of the child’s behavior problems, no psychotherapy with high amounts of PT, and no plans for a change in medical treatment of the child. In addition, the participating parent had to be motivated to take part in the study and be fluent in the German language, both written and verbal. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Participants were not only biological parents, but also step parents, foster parents, adoptive parents, and grandparents; for simplicity, we hereafter refer to them all as parents. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the behavior and nondirective groups. At pretreatment, no significant between-group differences were observed for the target children and the participating parents.

Study Design

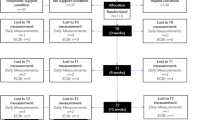

Parents of children with externalizing problem behavior were randomly assigned using computerized block randomization to either a behaviorally oriented self-help program (behavior group) or to a self-help program whose contents were based on nondirective supportive techniques (nondirective group). Parents in both groups received a parent booklet biweekly by mail up to a total of eight booklets, which contained information on parenting and strategies to deal with children. In the behavior group, these strategies explicitly targeted children with externalizing behavior problems, whereas the booklets for the nondirective group comprised strategies to deal with difficult parenting situations in general, consistent with the contents of PET (Gordon 1970). In addition, all participating parents received 10 biweekly telephone calls from a therapist during which they had the opportunity to discuss the advice given in the booklets and its implementation in the family’s daily routine. Each telephone call lasted about 20–30 min and was recorded with the participating parent’s permission. After the end of the 5-month intervention stage, participants received two booster telephone calls at 3- and 6-months follow-up. Because parents were recruited from across Germany, contact was by mail and telephone only and there was never any face-to-face contact. Accordingly, there was no contact between the staff members of the study and the target children.

Data were collected at pretreatment, 8 weeks after treatment start, immediately posttreatment, and at 6- and 12-months follow-up. The analyses in the present paper only included data at pretreatment and posttreatment. The five fully qualified therapists had university diplomas in psychology or education. To prevent effects due to the characteristics of the therapists, each therapist treated families in both intervention groups (behavior and nondirective). To ensure treatment adherence, therapists were trained by supervisors about the particular therapeutic techniques used in each intervention. Therapists received regular supervision during the course of the study. Detailed information about the study design and the findings from the main analysis has been presented previously (Hautmann and Döpfner 2015).

Interventions

The contents of the parent booklets for the behavior group were based on the German self-help book Wackelpeter & Trotzkopf (Döpfner et al. 2011). The booklets contained information about the etiology of externalizing problem behavior, as well as strategies for improving the parent-child interaction, giving effective commands, implementing family rules, positive and negative consequences and token systems, and for activating family resources. During the biweekly telephone calls, therapists conducted the conversation with the parents using a behavior therapy oriented and directive style.

By comparing the behavior group with the nondirective group, we also aimed to control for nonspecific intervention effects, such as attention, the therapeutic relationship, and feelings of support. For this purpose, nondirective supportive emotion-focused interventions provide the best possible control (Mohr et al. 2005). As PT based on the self-help books by Thomas Gordon (Gordon 1970) can be classified as nondirective supportive interventions, their contents were used for the parent booklets of the nondirective group. The booklets contained information about respectful communication methods between parent and child (e.g., I-messages, active listening), and how to resolve conflicts without defeat for either the parent or the child (the no-lose method). For the present study, therapists were trained to support parents during telephone calls in a nondirective supportive manner. No explicit advice was given by therapists on how to handle the children and parents were left to generate solutions by themselves.

Measures

Child Externalizing Behavior Problems

Symptoms of ADHD and ODD in children were assessed from the recorded semistructured interviews conducted by telephone with the participating parents. From each recorded interview, a blinded rater used the Diagnosis Checklist for ADHD (DCL-ADHD; Döpfner et al. 2008) to grade 18 symptoms of ADHD and the 9-item Diagnosis Checklist for Conduct Disorders (DCL-CD; Döpfner et al. 2008) to rate the level of oppositional-defiant behavior problems in the target child. For purposes of consistency between the blinded raters, we developed a standardized rating procedure with numerous practical examples for different grades of the symptomatology. The rating of pretreatment symptoms of ADHD and ODD was executed by a therapist in training with a university diploma in education, who was not part of the therapist team. The rating at posttreatment was carried out by two of the therapists. Each of them only rated interviews of parents, whom they had not treated themselves during the program. A student assistant made sure before the rating, that the record of the interview contained no names or information about group membership, and removed relevant parts of the record, if necessary. Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (nonexistent) to 3 (very strong). We then calculated item mean scores that, in the present sample, showed sufficient to good internal consistencies at pre- and posttreatment (Cronbach’s alphas = 0.85 and 0.79 for DCL-ADHD and 0.77 and 0.77 for DCL-CD).

Parent-reported children’s externalizing behavior problems were assessed using the externalizing problems subscale of the German version of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL/4–18; Arbeitsgruppe Deutsche Child Behavior Checklist 1998). The subscale consists of 33 items each rated on 3-point scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (true). A total externalizing problems score was generated by summing the individual item scores. Internal consistency was high with Cronbach’s alphas = 0.88 and 0.90 at pre- and posttreatment, respectively. Higher scores on all three outcome measures represent greater externalizing behavior problems.

Positive and Negative Parenting Practices

To assess parent-reported parenting practices, we constructed a new measure containing items from the Management of Children’s Behavior Scale (MCBS; Perepletchikova and Kazdin 2004) and the German Questionnaire About Parenting Behavior (FZEV; Naumann et al. 2007), as well as some newly generated items. The resulting Questionnaire for Positive and Negative Parenting Practices (QPNP) consists of two scales: positive parenting behavior (PPB; behavior to support a positive parent-child interaction), which consists of 21 items; and negative parenting behavior (NPB; inconsistent, impulsive, rigid parenting behavior), which consists of 17 items. The items are scored on 4-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (very often). For analysis, item mean scores are calculated for the two scales, with higher scores indicating a higher degree of the parenting behavior measured. In the present sample, the scales showed good to very good internal consistencies at pre- and posttreatment (Cronbach’s alphas = 0.90 and 0.91 for PPB and 0.81 and 0.81 for NPB). Detailed information about the construction and psychometric qualities of the QPNP can be found elsewhere (Imort et al. 2014).

Parental Self-Efficacy

We assessed parent-reported parental self-efficacy using the German version of the Questionnaire of Self-Efficacy (QSE; Naumann et al. 2007), which comprises 15 items rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much). For analysis, we calculated an item mean score, with higher scores indicating a higher degree of self-efficacy. In the present sample, the scale showed a good internal consistency with Cronbach’s alphas of 0.84 (pretreatment) and 0.81 (posttreatment).

Dysfunctional Parental Responsibility Attributions

We assessed parent-reported dysfunctional responsibility attributions of the parents for their child’s problem behavior using the child-related responsibility attributions subscale from the German version of the Parent Cognition Scale (PCS; Katzmann et al. 2015; Snarr et al. 2009), which consists of nine items. Parents are instructed to think about the problem behavior of their child during the last 2 months and to declare how much they agree with the proposed possible reasons for their child’s behavior on a scale ranging from 1 (always true) to 6 (never true). For analyses, items were recoded so that higher values indicate higher dysfunctional attributions, and an average score was calculated. In the present sample, the scale showed a good internal consistency with Cronbach’s alphas of 0.85 (pretreatment) and 0.87 (posttreatment).

Statistical Analyses

Baseline Differences

Demographics and baseline psychosocial variables were compared between the behavioral and nondirective groups using chi-square tests (for categorical variables) or t-tests for independent samples (for continuous variables).

Model Fit Indices

Model fit was determined using the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). The criteria for a good model fit were RMSEA values < 0.08, CFI values > 0.95, and SRMR values < 0.08 (Yu 2002).

Mediation Analyses

In a simple mediation model, the independent variable (X) affects the dependent variable (Y) through a mediating variable (M). The total effect of X on Y (expressed as the coefficient c) is the sum of the direct effect (c’) and the indirect or mediating effect (ab) (see Preacher and Hayes 2008, p. 880). The indirect effect consists of two paths, where X predicts M (a) and M predicts Y after controlling for X (b). The indirect effect is defined as the product of the unstandardized regression coefficients a and b (i.e., ab), which can also be tested for significance (Preacher and Hayes 2008). Some researchers consider that you can still conduct mediation analyses when the c coefficient for the total effect of X on Y is nonsignificant (e.g., Preacher and Hayes 2008; Rucker et al. 2011). Rucker et al. (2011) gave several reasons why a significant indirect effect can occur in the absence of a significant total effect.

When there are multiple possible mediating variables, Preacher and Hayes (2008, see p. 881) recommend they are tested in a multiple mediation model. Again, X and Y are the independent and dependent variables, respectively. Path c’ represents the direct effect of X on Y after controlling for the j mediating variables, where j stands for the number of mediating variables. The specific indirect effect ab j of each mediator is the product of the coefficients of path a j and path b j . It is noteworthy that interpretation of the specific indirect effects in a multiple mediation model differs from that of the indirect effect in a single mediation model because of covariation of the mediating variables. In a multiple mediation model, the specific indirect effect describes the mediating effect of one variable after accounting for other possible mediating effects of the other included putative mediators (Preacher and Hayes 2008). Because we are interested in the mediating role of each putative mediator in the presence of other possible mediating variables, our analyses concentrate on the significance of the specific indirect effects.

Mediation analyses were conducted using structural equation modeling with Mplus (Muthén and Muthén 2012). In our models, the independent variable was group membership, operationalized as a dichotomous variable (0 = nondirective group, 1 = behavior group). Three separate models examined the following outcome measures at posttreatment as the dependent variable: ADHD symptoms, ODD symptoms, and Externalizing Problems (from the CBCL/4–18). For each outcome measure at posttreatment, we tested a model with four putative mediating variables (positive parenting, negative parenting, parental self-efficacy, and dysfunctional parental responsibility attributions). To control for pretreatment differences, the pretreatment scores of the outcome measures and putative mediating variables were included as covariates in the models. We allowed the residuals of the mediating variables to covary (Preacher and Hayes 2008). The model was estimated using maximum likelihood estimation. For significance testing of the specific indirect effect, direct effect, and total effects, we calculated bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs) with 10,000 repetitions, as recommended by Preacher and Hayes (2008). The effects were regarded as significant if 0 was not included in the 95 % CI. In accordance with Hayes (2013), we report the effects as unstandardized regression coefficients.

Results

Attrition and Treatment of Missing Values

Figure 1 shows the flow of the participants through the study. Of the participating parents randomized to an intervention group, 22 (30 %) parents in the behavior group and 17 (22 %) parents in the nondirective group dropped out during the study. Because our study was aimed at investigating potential mediators for change of children’s behavior problems, our analysis only included those families that completed the program (per-protocol analysis). Among the final sample of 110 parents, missing values were handled using full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML; Enders 2001).

Multiple Mediation Models

The results of the separate multiple mediation models for the three outcome measures (DCL-ADHD, DCL-CD, and CBCL/4–18) are presented in Figs. 2, 3 and 4, respectively. For the ADHD symptoms (blinded clinical rating, DCL-ADHD), no significant total effect of treatment condition was observed after controlling for pretreatment scores (c = −0.01; see Fig. 2). However, there was a significant total effect for ODD symptoms (blinded clinical rating, DCL-CD) and for external behavior problems (parent-rated, CBCL/4–18), with c coefficients of −0.18 and c = −3.82, respectively (see Figs. 3 and 4). These total effects indicated that children in the behavior group displayed less behavior problems at posttreatment than children in the nondirective group.

Multiple mediation model for ADHD symptoms of the child in blinded clinical rating as outcome (n = 110). Notes: BG = behavioral group. NDG = non-directive group. a = unstandardized regression coefficient for effect of treatment on mediator. b = unstandardized regression coefficient for effect of mediator on outcome. c’ = unstandardized regression coefficient for direct effect of treatment on outcome, controlling for putative mediators. ab = indirect effect; product of a and b. c = unstandardized regression coefficient for total effect of treatment on outcome. * = significant effect based on bias corrected confidence interval. Measures: ADHD symptoms: DCL-ADHD. Positive parenting behavior: QPNP. Negative parenting behavior: QPNP. Parental self-efficacy: QSE. Parental attributions: PCS. Pretreatment scores of positive and negative parenting behavior, parental self-efficacy, parental attributions and ADHD symptoms are statistically controlled but not depicted in the model

Multiple mediation model for ODD symptoms of the child in blinded clinical rating as outcome (n = 110). Notes: BG = behavioral group. NDG = non-directive group. a = unstandardized regression coefficient for effect of treatment on mediator. b = unstandardized regression coefficient for effect of mediator on outcome. c’ = unstandardized regression coefficient for direct effect of treatment on outcome, controlling for putative mediators. ab = indirect effect; product of a and b. c = unstandardized regression coefficient for total effect of treatment on outcome. * = significant effect based on bias corrected confidence interval. Measures: ODD symptoms: DCL-CD. Positive parenting behavior: QPNP. Negative parenting behavior: QPNP. Parental self-efficacy: QSE. Parental attributions: PCS. Pretreatment scores of positive and negative parenting behavior, parental self-efficacy, parental attributions and ODD symptoms are statistically controlled but not depicted in the model

Multiple mediation model for externalizing problems of the child rated by the parents as outcome (n = 110). Notes: BG = behavioral group. NDG = non-directive group. a = unstandardized regression coefficient for effect of treatment on mediator. b = unstandardized regression coefficient for effect of mediator on outcome. c’ = unstandardized regression coefficient for direct effect of treatment on outcome, controlling for putative mediators. ab = indirect effect; product of a and b. c = unstandardized regression coefficient for total effect of treatment on outcome. * = significant effect based on bias corrected confidence interval. Measures: Externalizing problems: CBCL. Positive parenting behavior: QPNP. Negative parenting behavior: QPNP. Parental self-efficacy: QSE. Parental attributions: PCS. Pretreatment scores of positive and negative parenting behavior, parental self-efficacy, parental attributions and externalizing problems are statistically controlled but not depicted in the model

The three models showed a good to excellent fit to the data (χ 2 = 17.64 to χ 2 = 38.01, df = 25, p = 0.05 to p = 0.23, RMSEA = 0 to RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.97 to CFI = 1, SRMR = 0.05 to SRMR = 0.06).

Group membership significantly predicted the changes in positive and negative parenting behavior, parental self-efficacy, and dysfunctional parental responsibility attributions (see a coefficients in Figs. 2, 3, and 4). Parents in the behavior group had a greater improvement on each of the putative mediating variables than parents in the nondirective group. Among these mediators, only dysfunctional parental responsibility attributions predicted the extent of child externalizing behavior problems at posttreatment (see b coefficients in Figs. 2, 3, and 4). This finding applied to all three outcome measures (DCL-ADHD, DCL-CD, CBCL/4–18) and indicated that the more parents attributed the problem behavior of their child to a negative or hostile intent of the child, the worse the child’s symptoms were at posttreatment.

The test for indirect effects (mediating effects) of treatment group on outcome variables (DCL-ADHD, DCL-CD, CBCL/4–18) via dysfunctional parental attributions reached significance (see ab coefficients for parental attributions in Figs. 2, 3, and 4), indicating that children in the behavior group displayed less externalizing behavior at posttreatment due to fewer dysfunctional attributions of the parents. The test for direct effects failed to reach significance for ADHD and ODD symptoms (blinded clinical rating, DCL-ADHD/DCL-CD) as shown by the c’ coefficients in Figs. 2 and 3, whereas there was a significant direct effect of group membership in favor of the behavior group (c’ = −3.10, see Fig. 4) for the parent-rated externalizing problems of the child (CBCL/4–18) after controlling for the (putative) mediating variables.

Discussion

In summary, our findings suggest that the attribution by parents of a (less) hostile intent of the child works as a mediating mechanism for the reduction in externalizing behavior problems of their children in behaviorally oriented PT compared with nondirective PT. Parents who took part in the behavioral oriented guided self-help program showed a greater decrease in dysfunctional attributions than parents in the nondirective supportive program, and this, in turn, resulted in a stronger decrease of child externalizing behavior problems at the end of treatment. This finding indicates that a particular strength of the behavioral based approach is the ability to modify parental attributions (e.g., psychoeducation, explanatory models of the development of child behavior problems). The behavioral self-help intervention also led to a greater improvement in (negative and positive) parenting behavior as well as parental self-efficacy, compared with the nondirective treatment. However, these changes did not explain the children’s symptoms at the end of treatment when the dysfunctional parental attributions were also taken into account.

We cannot compare our results with previous research because no similar analyses of the mechanisms of change in behaviorally oriented PT versus nondirective PT have been performed. Furthermore, other mediation analyses of PT have focused on positive or negative parenting behavior as a mediator and did not examine a joint model with parental attributions (e.g., Fossum et al. 2009; Gardner et al. 2010; Kling et al. 2010). Therefore, it is possible that the factor that worked as a mediating mechanism in earlier studies was a change of parental attributions. We also tested each of the four putative mediating variables in single mediation models; the results showed only a significant indirect effect for dysfunctional parental attributions, thus ruling out the possibility that the variables were too strongly associated to contribute individually to the model. This indicates that the change of parental behavior in our study had no mediating effect on the outcomes, regardless of whether it was considered alone or in a joint model with other putative mediators. One might conclude that this finding is specific to the mechanisms of action of our guided self-help program. As there was a significant treatment effect on parenting behavior in favor of the behavioral program, we consider it unlikely that the lack of association between parenting behavior and external problem behavior of the child is due to the specific characteristics of the guided self-help program. A more likely reason for this finding is a differing operationalization of positive and negative parenting in comparison to other studies.

To our knowledge, this is the first mediation analysis of guided self-help interventions in the treatment of externalizing behavior disorders. Furthermore, in the broader context of PT, it is the first mediation analysis that considered dysfunctional parental attributions as a putative mediator variable. In line with the current recommendations from existing research (Preacher and Hayes 2008), we conducted a multiple mediation analysis rather than testing each putative mediator individually. Finally, we examined outcome variables from two different perspectives, making it possible to compare the (blinded) clinical ratings with parental evaluation of the behavior problems of the child.

A further strength of our study is the comparison of two different treatment groups. The study design allowed us to examine specific mechanisms of change in a behavior program in comparison with a nondirective intervention. Currently, there is limited knowledge on the importance of behavioral techniques for therapeutic success (Jensen et al. 2005). However, the design of our study limits the interpretation of our findings with respect to general mediation mechanisms in guided self-help interventions. Upon closer examination of the changes in externalizing symptomatology from pre- to posttreatment, we found a significant reduction in both groups for each of the three outcome variables. These results are consistent with other studies comparing behavioral and nonbehavioral PT (Lundahl et al. 2006). Since we had no waitlist control group, we could not detect common mechanisms of change as for example the (unmeasured) therapist-parent relationship that might have led to a reduction of external behavior problems in both groups.

Furthermore, our results do contribute to improved understanding of the behavioral intervention, but they do not shed light on the mechanisms of action in the nondirective condition. For example, for the blinded clinical rating of ADHD symptoms, we observed a reduction in both groups with no treatment advantage for either intervention. Yet, we could only detect mediating variables for the behavior group but none for the nondirective group. That is, for the nondirective group, we probably did not assess the relevant mediating variables. What we do know, however, is that the reduction in the outcome variables in the nondirective group did not take place through the change of parenting behavior, parental self-efficacy, or parental attributions.

Some other limitations also need to be mentioned. First, assessment of mediators and outcomes took place at the same time (both at posttreatment). Therefore, the assumed sequence (behavior intervention leads to change in attributions, leading to a decrease in behavior problems) is not definite. It is also possible that the behavior program led to a decrease in externalizing behavior problems through another mechanism that we did not consider in our analysis, and which resulted in a change of parental attributions. It would have been preferable to assess the mediation variables before a change in outcome was expected to occur. In a further analysis using the same models, we tested the potential mediators at posttreatment and the outcome parameters at 6-months follow-up: the significant effects disappeared when the outcome at posttreatment was included as a covariate, indicating that the relevant changes in both mediator and outcome occurred before the end of treatment. Nevertheless, we consider the proposed sequence of parental attributions as a mediator for the change in children’s symptomatology is theoretically reasonable because the intervention only had a direct connection to the parents. Furthermore, it would be difficult to explain why a reduction of children’s externalizing behavior would not have resulted in a decrease of dysfunctional parental attributions in the nondirective group as well. Although the reverse direction of change seems less likely, further research with more continuous assessment of mediators and outcomes is required to determine more accurately the causal direction of effect of the variables.

Second, the change in parental attributions alone is not sufficient to explain the change in child symptoms. Because attributions are a concept of social-cognitive information processing rather than actual (apparent) behavior, there should be at least one other mechanism that links the parental attributions to the behavior problems of the child. The change in parenting behavior would present a logical addition, but this is not supported by our findings of the lack of a significant connection between parental practices and symptomatology. Because this may be due to the operationalization of parenting behavior in our study, the proposed sequence of mediation would be worth further investigation. It is also reasonable that the less hostile parental attributions did not lead to an actual change of child’s behavior, but to a change in parent’s perception of their child’s behavior problems.

Third, the blinded clinical ratings were obtained from structured interviews with the parents rather than from direct observations of child behavior because participants were recruited from across the whole of Germany. We tried to increase reliability by developing a highly standardized procedure for conducting the interviews as well as performing the subsequent ratings. Yet, as mentioned earlier, it is possible that a change in parental perception of the child’s behavior instead of an actual reduction of problem behavior could have affected the clinical rating.

Finally, to minimize the influence of the characteristics of the different therapists, every therapist treated families in both treatment groups. However, because they all were behaviorally oriented therapists, we cannot rule out the possibility that, despite therapist training and supervision, there were more behavioral oriented elements in the nondirective group than planned, resulting in smaller group differences and, thus, smaller effects. The possibility of across condition leakage could also have lead to a stronger impact of common unspecific mechanisms of change such as the therapist-parent relationship which we already mentioned above. Nevertheless, the observed group differences for the four putative mediator variables at posttreatment indicate that the parents in the two groups received different treatments.

In conclusion, our study gives initial indications for the importance of the modification of parental attributions in behaviorally oriented PT presented as a self-help intervention when compared to nondirective supportive treatment. Parental attributions seem to play a significant role in the change of externalizing behavior problems and, therefore, should be considered as a mediating variable together with other (putative) mediators within a multiple mediation model. The behaviorally oriented self-help intervention also led to a stronger improvement on parenting practices and parental self-efficacy.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Arbeitsgruppe Deutsche Child Behavior Checklist (1998). Elternfragebogen über das Verhalten von Kindern und Jugendlichen; deutsche Bearbeitung der child behavior checklist (CBCL/4–18). In Köln: Arbeitsgruppe kinder-. Jugend- und: Familiendiagnostik (KJFD).

Beauchaine, T. P., Webster-Stratton, C., & Reid, M. J. (2005). Mediators, moderators, and predictors of 1-year outcomes among children treated for early-onset conduct problems: a latent growth curve analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 371–388.

Bugental, D. B., Crane Ellerson, P., Lin, E. K., Rainey, B., Kokotovic, A., & O’Hara, N. (2002). A cognitive approach to child abuse prevention. Journal of Family Psychology, 16, 243–258.

Carter, A. (2010). Prevalence of DSM-IV disorder in a representative, healthy birth cohort at school entry: sociodemographic risks and social adaption. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 686–698.

Cedar, B., & Levant, R. F. (1990). A meta-analysis of the effects of parent effectiveness training. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 18, 373–384.

Corcoran, J., & Dattalo, P. (2006). Parent involvement in treatment for ADHD: a meta-analysis of the published studies. Research on Social Work Practice, 16, 561–570.

Daley, D., & O’Brien, M. (2013). A small-scale randomized controlled trial of the self-help version of the new forest parent training programme for children with ADHD symptoms. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 22, 542–552.

de Graaf, I., Speetjens, P., Smit, F., de Wolff, M., & Tavecchio, L. (2008). Effectiveness of the triple P positive parenting program on parenting: a meta-analysis. Family Relations, 57, 553–566.

Dekovic, M., Asscher, J. J., Hermanns, J., Reitz, E., Prinzie, P., & van den Akker, A. L. (2010). Tracing changes in families who participated in the home-start parenting program: parental sense of competence as mechanism of change. Prevention Science, 11, 263–274.

Döpfner, M., Görtz-Dorten, A., & Lehmkuhl, G. (2008). Diagnostik-system für psychische Störungen im Kindes- und Jugendalter nach ICD-10 und DSM-IV, DISYPS-II. Bern: Huber.

Döpfner, M., Schürmann, S., & Lehmkuhl, G. (2011). Wackelpeter und Trotzkopf: Hilfen für Eltern bei ADHS-Symptomen, hyperkinetischem und oppositionellem Verhalten (4. Aufl ed.). Weinheim: Beltz.

Elgar, F. J., & McGrath, P. J. (2003). Self-administered psychosocial treatments for children and families. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59, 321–339.

Enders, C. K. (2001). The performance of the full information maximum likelihood estimator in multiple regression models with missing data. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61, 713–740.

Enebrink, P., Högström, J., Forster, M., & Ghaderi, A. (2012). Internet-based parent management training: a randomized controlled study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50, 240–249.

Eyberg, S. M., Nelson, M. M., & Boggs, S. R. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37, 215–237.

Fabiano, G. A., Pelham Jr., W. E., Coles, E. K., Gnagy, E. M., Chronis-Tuscano, A., & O’Connor, B. C. (2009). A meta-analysis of behavioral treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 129–140.

Farmer, E. M. Z., Compton, S. N., Burns, J. B., & Robertson, E. (2002). Review of the evidence base for treatment of childhood psychopathology: externalizing disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 1267–1302.

Fossum, S., Morch, W.-T., Handegard, B. H., Drugli, M. B., & Larsson, B. (2009). Parent training for young norwegian children with ODD and CD problems: predictors and mediators of treatment outcome. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 50, 173–181.

Gardner, F., Burton, J., & Klimes, I. (2006). Randomised controlled trial of a parenting intervention in the voluntary sector for reducing child conduct problems: outcomes and mechanisms of change. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 1123–1132.

Gardner, F., Hutchings, J., Bywater, T., & Whitaker, C. (2010). Who benefits and how does it work? Moderators and mediators of outcome in an effectiveness trial of a parenting intervention. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39, 568–580.

Glasgow, R. E., & Rosen, G. M. (1978). Behavioral bibliotherapy: a review of self-help behavior therapy manuals. Psychological Bulletin, 85, 1–23.

Gordon, T. (1970). P. E. T. Parent effectiveness training: the tested new way. Philadelphia: David McKay Company.

Hagen, K. A., Ogden, T., & Bjornebekk, G. (2011). Treatment outcomes and mediators of parent management training: a one-year follow-up of children with conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40, 165–178.

Halligan, S. L., Cooper, P. J., Healy, S. J., & Murray, L. (2007). The attribution of hostile intent in mothers, fathers and their children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 594–604.

Hanisch, C., Hautmann, C., Plück, J., Eichelberger, I., & Döpfner, M. (2014). The prevention program for externalizing problem behavior (PEP) improves child behavior by reducing negative parenting: analysis of mediating processes in a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55, 473–484.

Hautmann, C., & Döpfner, M. (2015). Comparison of behavioral and non-directive guided self-help for parents of children with externalizing behavior problems. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(Suppl. I), 17.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

Hektner, J. M., August, G. J., Bloomquist, M. L., Lee, S., & Klimes-Dougan, B. (2014). A 10-year randomized controlled trial of the early risers conduct problems preventive intervention: effects on externalizing and internalizing in late high school. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82, 355–360.

Imort, S., Hautmann, C., Greimel, L., Katzmann, J., Pinior, J., Scholz, K., & Döpfner, M. (2014, May). Der Fragebogen zum positiven und negativen Erziehungsverhalten (FPNE): eine psychometrische Zwischenanalyse. In Poster zum 32. Symposium der Fachgruppe Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie der: DGPs, Braunschweig, Germany.

Ise, E., Kierfeld, F., & Döpfner, M. (2014). One-year follow-up of guided self-help for parents of preschool children with externalizing behavior. Journal of Primary Prevention, 36, 33–40.

Jensen, P. S., Weersing, R., Hoagwood, K. E., & Goldman, E. (2005). What is the evidence for evidence-based treatments? A hard look at our soft underbelly. Mental Health Services Research, 7, 53–74.

Johnston, C., Hommersen, P., & Seipp, C. M. (2009). Maternal attributions and child oppositional behavior: a longitudinal study of boys with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 189–195.

Johnston, C., & Ohan, J. L. (2005). The importance of parental attributions in families of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity and disruptive behavior disorders. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 8, 167–182.

Kaminski, J. W., Valle, L. A., Filene, J. H., & Boyle, C. L. (2008). A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 567–589.

Katzmann, J., Hautmann, C., Greimel, L., Imort, S., Pinior, J., Scholz, K., & Döpfner, M. (2015). Dysfunktionale Attributionen von Eltern und ihre Bedeutung für ihr Erziehungsverhalten und für expansives Problemverhalten von Kindern – eine psychometrische Überprüfung und Anwendung der deutschen Fassung des Fragebogens zu dysfunktionalen elterlichen Attributionen (FDEA). Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 44, 266–271.

Kierfeld, F., Ise, E., Hanisch, C., Görtz-Dorten, A., & Döpfner, M. (2013). Effectiveness of telephone-assisted parent-administered behavioural family intervention for preschool children with externalizing problem behaviour: a randomized controlled trial. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 22, 553–565.

Kling, Å., Forster, M., Sundell, K., & Melin, L. (2010). A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of parent management training with varying degrees of therapist support. Behavior Therapy, 41, 530–542.

Kraemer, H. C., Wilson, G. T., Fairburn, C. G., & Agras, W. S. (2002). Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 877–883.

Lavigne, J. V., Lebailly, S. A., Gouze, K. R., Cicchetti, C., Pochyly, J., Arend, R., et al. (2008). Treating oppositional defiant disorder in primary care: a comparison of three models. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33, 449–461.

Lundahl, B., Risser, H. J., & Lovejoy, M. C. (2006). A meta-analysis of parent training: moderators and follow-up effects. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 86–104.

Markie-Dadds, C., & Sanders, M. R. (2006). A controlled evaluation of an enhanced self-directed behavioural family intervention for parents of children with conduct problems in rural and remote areas. Behaviour Change, 23, 55–72.

McGrath, P. J., Lingley-Pottie, P., Thurston, C., MacLean, C., Cunningham, C., Waschbusch, D. A., et al. (2011). Telephone-based mental health interventions for child disruptive behavior or anxiety disorders: randomized trials and overall analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 1162–1172.

McTaggart, P., & Sanders, M. R. (2007). Mediators and moderators of change in dysfunctional parenting in a school-based universal application of the triple-P positive parenting programme. Journal of Children’s Services, 2, 4–17.

Mohr, D. C., Hart, S. L., Julian, L., Catledge, C., Honos-Webb, L., Vella, L., & Tasch, E. T. (2005). Telephone-administered psychotherapy for depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 1007–1014.

Mokros, L., Benien, N., Mütsch, A., Kinnen, C., Schürmann, S., Metternich-Kaizman, T. W., et al. (2015). Angeleitete Selbsthilfe für Eltern von Kindern mit Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit−/Hyperaktivitätsstörung: Konzept, Inanspruchnahme und Effekte eines bundesweiten Angebotes – eine Beobachtungsstudie. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie, 43, 275–288.

Montes, M. P., de Paúl, J., & Milner, J. S. (2001). Evaluations, attributions, affect, and disciplinary choices in mothers at high and low risk for child physical abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25, 1015–1036.

Montgomery, P., Bjornstad, G. J., & Dennis, J. A. (2006). Media-based behavioural treatments for behavioural problems in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2006(1), 1–44. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002206.pub3.

Morrissey-Kane, E., & Prinz, R. J. (1999). Engagement in child and adolescent treatment: the role of parental cognitions and attributions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 2, 183–198.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus (version 7.0) [computer software]. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Naumann, S., Kuschel, A., Bertram, H., Heinrichs, N., & Hahlweg, K. (2007). Förderung der Elternkompetenz durch triple P-Elterntrainings. Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie, 56, 676–690.

Nieuwboer, C. C., Ruben, G. F., & Hermanns, J. M. A. (2013). Online programs as tools to improve parenting: a meta-analytic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 35, 1823–1829.

Nix, R. L., Pinderhughes, E. E., Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., Pettit, G. S., & McFadyen-Ketchum, S. A. (1999). The relation between mothers’ hostile attribution tendencies and children’s externalizing behavior problems: the mediating role of mothers’ harsh discipline practices. Child Development, 70, 896–909.

O’Brien, M., & Daley, D. (2011). Self-help parenting interventions for childhood behaviour disorders: a review of the evidence. Child: Care, Health & Development, 37, 623–637.

Perepletchikova, F., & Kazdin, A. E. (2004). Assessment of parenting practices related to conduct problems: development and validation of the management of children’s behavior scale. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 13, 385–403.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Reid, G. J., Stewart, M., Vingilis, E., Dozois, D. J., Wetmore, S., Jordan, J., et al. (2013). Randomized trial of distance-based treatment for young children with discipline problems seen in primary health care. Family Practice, 30, 14–24.

Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5, 359–371.

Snarr, J. D., Smith Slep, A. M., & Grande, V. P. (2009). Validation of a new self-report measure of parental attributions. Psychological Assessment, 21, 390–401.

Tarver, J., Daley, D., Lockwood, J., & Sayal, K. (2014). Are self-directed parenting interventions sufficient for externalising behaviour problems in childhood? A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 23, 1123–1137.

Thomas, R., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2007). Behavioral outcomes of parent-child interaction therapy and triple P–positive parenting program: a review and meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 475–495.

Whisman, M. A. (1993). Mediators and moderators of change in cognitive therapy of depression. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 248–265.

Wilson, C., Gardner, F., Burton, J., & Leung, S. (2006). Maternal attributions and young children’s conduct problems: a longitudinal study. Infant and Child Development, 15, 109–121.

Yu, C.-Y. (2002). Evaluating cutoff criteria of model fit indices for latent variable models with binary and continuous outcomes. University of California, Los Angeles: Unpublished manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; German Research Foundation) (grant number DO 620/5–1).

Conflict of Interest

Josepha Katzmann, Christopher Hautmann, Stephanie Imort, Julia Pinior, Kristin Scholz and Manfred Döpfner are authors of the parent booklets used in the behavioral intervention of this study. Manfred Döpfner received income as Head of the School for Child and Adolescent Behavior Therapy at the University of Cologne and royalties from treatment manuals, books and psychological tests published by Guilford, Hogrefe, Enke, Beltz, and Huber. Lisa Greimel declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University Hospital of Cologne (ref: 09–123).

Human and Animal Rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Katzmann, J., Hautmann, C., Greimel, L. et al. Behavioral and Nondirective Guided Self-Help for Parents of Children with Externalizing Behavior: Mediating Mechanisms in a Head-To-Head Comparison. J Abnorm Child Psychol 45, 719–730 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0195-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0195-z