Abstract

The present study extends earlier research identifying an increased risk of anxiety among children with chronic physical illness (CwCPI) by examining a more complete model that explains how physical illness leads to increased symptoms of anxiety and depression. We tested a stress-generation model linking chronic physical illness to symptoms of anxiety and depression in a population-based sample of children aged 10 to 15 years. We hypothesized that having a chronic physical illness would be associated with more symptoms of anxiety and depression, increased levels of maternal depressive symptoms, more family dysfunction, and lower self-esteem; and, that maternal depressive symptoms, family dysfunction, and child self-esteem would mediate the influence of chronic physical illness on symptoms of anxiety and depression. Data came from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (N = 10,646). Mediating processes were analyzed using latent growth curve modeling. Childhood chronic physical illness was associated with increases in symptoms of anxiety and depression, β = 0.20, p < 0.001. Mediating effects were also observed such that chronic physical illness resulted in increases in symptoms of maternal depression and family dysfunction, leading to declines in child self-esteem, and in turn, increases in symptoms of anxiety and depression. CwCPI are at-risk for symptoms of anxiety and depression. Some of this elevated risk appears to work through family processes and child self-esteem. This study supports the use of family-centered care approaches among CwCPI to minimize burden on families and promote healthy psychological development for children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Nearly 20 % of children have a chronic physical illness (e.g., asthma, diabetes, epilepsy; van der Lee et al. 2007) that exerts an adverse impact on them, their families, and society. Chronic physical illness is defined as having a biological basis, being present for at least one year, and resulting in one or more of the following sequelae: functional limitations, dependencies to compensate for limitations in function (e.g., medication, assistive devices), and the need for health care above the usual level of care for youth of that age (Stein et al. 1993). The five leading causes of mortality in childhood are chronic physical illnesses (Hoyertet al. 2006), and 42 % of health costs in children are attributable to such conditions (Newacheck and Kim 2005). Recent U.S. data show that chronic physical illness results in substantial functional disability and school activity limitations (Msall et al. 2003). Moreover, having a child with special health needs is associated with increased marital stress, divorce, and financial hardship (Reichman et al. 2004).

Children with chronic physical illness (CwCPI) face considerable challenges to their psychological well-being (Zashikhina and Hagglof 2007), reporting significantly higher levels of psychiatric disorder compared to healthy children (Pinquart and Shen 2011b). Cross-sectional studies suggest that CwCPI have almost a three-fold increase in the risk of developing emotional-behavioral problems compared to their healthy counterparts (Blackman et al. 2011). Furthermore, the differential risk for emotional-behavioral problems across chronic physical illness groups is generally negligible. For example, recent meta-analyses showed that effect sizes for symptoms of anxiety and depression were slightly larger among children with neurological illnesses versus other chronic physical illnesses (Pinquart and Shen 2011a); and that associations between child self-esteem and chronic physical illnesses were relatively homogenous across illness types (Ferro and Boyle 2013c). Elements of family functioning such as emotional expression, communication patterns, and conflict resolution also seem to exhibit few differences across illness types (Holmes and Deb 2003; McClellan and Cohen 2007).

Investigators have called for population-based research into family processes and child factors that mediate the health effects of having a chronic physical illness in childhood (Witt and DeLeire 2009; Zimmer and Minkovitz 2003) with a “plea for more developmentally appropriate, family-focused and child-led models of anxiety in young populations” (Cartwright-Hatton 2006, p. 813). Few studies have taken a causal modeling approach to examining the pathways through which exposure to chronic physical illness might increase risk for adverse childhood emotional-behavioral outcomes, particularly symptoms of anxiety. When chronic physical illness is present in children, parents report increased levels of depression (Singer 2006); families, more dysfunction (Wallander and Varni 1998); and, the children themselves, lower self-esteem (Ferro and Boyle 2013b, c). Unfortunately, the mechanisms linking these processes have not been modeled in CwCPI. Clarifying these mechanisms will lead to a better understanding of how we might mute these mechanisms, informing the development of prevention strategies, and refining treatment approaches for children with anxiety and depression.

There are good reasons to untangle the developmental mechanisms linking childhood chronic physical illness and symptoms of anxiety and depression in the context of the family environment. The diagnosis of a chronic physical illness in childhood is associated with elevated risk for maternal depression (Brehaut et al. 2009; Ferro and Speechley 2009; Whittemore et al. 2012). There is also evidence that family functioning mediates the impact of maternal depressive symptoms on behaviour and quality of life in CwCPI (Ferro et al. 2011; Lim et al. 2011) and that child self-esteem mediates the impact of maternal depressive symptoms and family functioning on anxiety disorders in children (Roustit et al. 2010; Yen et al. 2013). At least one meta-analysis supports the argument that the family environment is an important context for the development and treatment of symptoms of anxiety and depression in children (McLeod et al. 2007).

The notion that CwCPI may be at elevated risk for anxiety and depression is consistent with current theories linking physical and mental health. According to cognitive-behavioural theories, anxiety can arise from negatively-biased thought patterns that exaggerate the risk and adverse effects of illness episodes, and undermine confidence in handling potentially threatening situations (Beck et al. 1985). For example, the experience of unpredictable asthma attacks or seizures can lead to a state of learned helplessness that can lead to symptoms of anxiety (Chaney et al. 1999; Hoppe and Elger 2011).

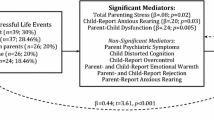

Furthermore, stress models suggest that CwCPI are exposed to higher allostatic load, which results in adverse effects on mental health (Bahreinian et al. 2013; McEwen 1998). The increased allostatic load in CwCPI may be the result of shared biological pathways or psychosocial and clinical factors which can have a negative impact on the stress levels of these children (Datta et al. 2005; McCaffery et al. 2012; Mullick et al. 2005). However, little is known empirically about additional stressors and how they mediate the adverse effects of chronic physical illness on mental health. Stress-generation theory (Hammen 1991) hypothesizes that some individuals, based on trait (e.g., having a chronic physical illness) or state (e.g., experiencing a current exacerbation of the illness) characteristics generate circumstances (i.e., dependent stressors/stress mediators) for themselves and intimate others, which can lead to further declines in physical and mental health of the individual in a potentially devastating cycle. As illustrated in Fig. 1, stressors such as the diagnosis of a chronic physical illness in childhood can increase the risk for symptoms of anxiety and depression directly, or its effect can be mediated, or transmitted by, symptoms of maternal depression, family dysfunction, and child self-esteem. In other words, having a potentially debilitating health condition may place CwCPI at increased risk for symptoms of anxiety and depression as a result of increasing maternal depressive symptoms, worsening family dysfunction, and declines in self-esteem. This model has been used previously to examine mediational pathways leading to symptoms of depression in adolescents (Auerbach et al. 2011; Kercher and Rapee 2009).

A Stress-Generation Model for Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression in Children. The model illustrates the hypothesized relationships linking chronic physical illness and symptoms of anxiety and depression in childhood. While there is some evidence for bidirectional associations within the model, the one-way arrows depict the direction of effect that was tested in the current study. Although not shown for simplicity, each construct (circles) was modeled using latent intercepts and slopes representing their respective initial status and growth rate. Each variable was measured at all three waves (ages 10–11, 12–13, and 14–15) to examine concurrent changes over time. Because the mediational model used to analyze the data focuses on how components of the model change over time, parameter estimates (β) and their associated standard errors for the slope of each construct are shown. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Symptoms of anxiety and depression are hypothesized to be the converging consequence of all components in the stress-generation model. The examination of symptoms of anxiety and depression during childhood/late adolescence is particularly important because of the academic, social, economic, and public health implications resulting from elevated symptoms (Costello et al. 2005; Ginsburg et al. 1998; Greenberg et al. 1999; Ialongo et al. 1996). Anxiety disorder is the most common mental health problem among children, with an estimated prevalence as high as 24 % and typically increasing from childhood to adolescence (Costello et al. 2005; Merikangas et al. 2009). The developmental processes that may explain this rise in prevalence include puberty-related hormonal changes, increased capacity for self-reflection and rumination associated with cognitive maturation, increased psychological stress resulting from normative developmental transitions, and changing relationships with parents and peers (Ge et al. 2001; Hankin et al. 2007). Given the evidence that many children experience subclinical symptoms of anxiety and depression and that anxiety disorder in childhood is a major risk factor for mental disorder in adulthood (Kim-Cohen et al. 2003), childhood is a critical period for identification, prevention, and intervention.

It is important to acknowledge that most CwCPI do not experience elevated symptoms of anxiety and depression suggesting that resilience in these children may be a prominent factor contributing to psychological well-being. There is a growing body of evidence that points to the family as the major determinant of resilience in CwCPI (Patterson and Blum 1996). Despite the difficulties associated with having a CwCPI, the ability of a family to maintain healthy functioning, adapt to stressors, and refocus priorities reflect their resilience, which in turn can foster healthy psychological development of children (Gannoni and Shute 2010; Rolland and Walsh 2006).

The objective of this study was to test a stress-generation model of putative mechanisms that may link chronic physical illness to symptoms of anxiety and depression in a population-based sample of children aged 10-15 years. Compared to healthy controls, we hypothesized that mothers of CwCPI would report more symptoms of depression, their families experience greater levels of dysfunction, and CwCPI report lower self-esteem and more symptoms of anxiety and depression. In addition, symptoms of maternal depression, family dysfunction, and child self-esteem would form a web of interconnected relationships mediating the negative impact of chronic physical illness on symptoms of child anxiety and depression: Chronic physical illness in childhood would lead to higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms leading to more family dysfunction, resulting in declines in child self-esteem, and in turn, leading to increases in symptoms of child anxiety and depression.

Methods

Data Source and Participants

Data came from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY) (Statistics Canada 2007). The NLSCY was a study of Canadian children from birth to early adulthood on factors influencing children’s social and behavioral development. The study methods are summarized here, with details available elsewhere (Statistics Canada 2007). Using a stratified, multistage, probability design based on Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey, the NLSCY enlisted a representative sample of newborns to 11 year-old children (N = 22,831). Institutionalized children and those living on Aboriginal reserves were excluded. At each 2-year interval, children and their corresponding person most knowledgeable (PMK) caregiver completed a survey battery assessing sociodemographic and health-related constructs, including medical, psychological, and behavioral variables.

Waves 1–8 of the NLSCY were merged and restricted to 10–15 year-old children. This identified 15,389 children with self-assessments on at least one of three assessment occasions when they were 10–11, 12–13, and 14–15 years old. All data were measured at each of these three waves. The sample was then restricted to children where the PMK was the mother, N = 12,740 (83 %) as mothers typically perform the role of primary caregiver to children (Marshall 2006). Children whose mothers reported inconsistent health status (e.g., asthma at 10–11 years, but no asthma at 12–13 years) were excluded, N = 10,714 (70 %). A total of 68 children were also excluded due to missing household identifiers, resulting in a final sample size of N = 10,646 (69 %). There were no significant sociodemographic differences between children included (N = 10,646) and excluded in the analysis (N = 4,743), with the exception that excluded participants reported more family dysfunction (8.3 vs. 7.9, p = 0.014). Children were included if they completed at least one assessment. Among participants, 8,091 (76 %) completed the three assessments. Comparing respondents who completed all three assessments versus those who did not, missing data was associated (p < 0.001) with mothers who were younger (age in years 38.6 vs. 39.2), not married (20 % vs. 14 %), lower education (post-secondary graduate: 37 % vs. 43 %), and lower household income (income ≥ $80,000: 18 % vs. 25 %). Participation in the NLSCY was voluntary and ethical approval was obtained from McMaster University.

Measures

Symptoms of anxiety and depression were measured using seven items adapted from the Ontario Child Health Study Checklist when adolescents were 10–11 years of age (Boyle et al. 1993). The items were assessed using a 3-point scale (0 = never or not true; 1 = sometimes or somewhat true; 2 = often or very true) such that higher scores indicated more symptoms. Sample questions included, “I am unhappy or sad”; “I worry a lot”; and “I have trouble enjoying myself”. The scale demonstrated good reliability (α = 0.76). Composite scores spanned 0–14 with higher scores indicating more symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Child self-esteem was measured using four items from the General Self-image subscale of the Self-Description Questionnaire (Marsh 1992). The four items were: “In general, I like the way I am”; “Overall, I have a lot to be proud of”; “A lot of things about me are good”; and “When I do something, I do it well” (Statistics Canada 2007). The items were rated using a 5-point Likert scale (0–4). Composite scores spanned 0–16 with higher scores indicating better self-esteem. The scale demonstrated good reliability (α = 0.84).

Maternal depressive symptoms were measured using a reduced version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977), a 12-item questionnaire designed to assess depressive symptoms over the past week (Poulin et al. 2005). A 4-point Likert scale (0–3) was used to rate the frequency of symptoms experienced (e.g., “I felt depressed”; “I felt lonely”). Composite scores spanned 0–36 with higher scores indicating greater impairment. The scale demonstrated good reliability (α = 0.86).

Mother-reported family dysfunction was measured using the 12-item General Functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD), providing an overall measure of the health/pathology of the family (Byles et al. 1988). Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0–3; e.g., “We confide in each other”; “We don’t get along well together”). Composite scores spanned 0–36 with higher scores indicating more family dysfunction. The scale demonstrated excellent reliability (α = 0.91).

Child chronic physical illness was measured by asking mothers, “Has a health professional diagnosed any of the following long-term conditions for this child…? (asthma; cerebral palsy; epilepsy; heart condition; kidney condition; any other long-term condition). As required by Statistics Canada, the categories were aggregated and coded as binary (1 = present; 0 = absent) due to low case counts for some conditions. This resulted in 1,932 children classified as having a chronic physical illness and 8,714 healthy controls.

Children reported on their age in years, sex, and immigrant status (born in/out of Canada). Parents reported their sex, age in years, immigrant status (born in/out of Canada), education attainment (elementary school, secondary school graduate, some post-secondary, postsecondary graduate), employment status (working full- or part-time/unemployed), marital status (yes [includes common-law relationships]/no), and annual household income (categorized by $20,000 intervals, from < $20,000 to ≥ $80,000).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline comparisons between children with and without chronic physical illness were conducted with χ 2 and t-tests using SAS 9.2. Effect sizes (d) were calculated using Hedges’s g to account for unequal sample sizes (Hedges and Olkin 1984) and interpreted according to published guidelines (Cohen 1988). The method of variance estimates recovery was used to calculate the 95 % confidence interval for differences in the magnitude of mediating effect estimates (Zou and Donner 2008). Concurrent mediating processes within the model were examined using latent growth curve modeling in Mplus 7.11 (MacKinnon 2008). Due to the complex, hierarchical structure of the NLSCY, the model was estimated using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (Muthén and Muthén 2010). In the multistep method described by MacKinnon (2008), modeling of each individual variable over time (i.e., maternal depressive symptoms, family dysfunction, child self-esteem, child anxiety and depression) was conducted first for each subgroup (i.e., CwCPI and controls). Next, each of these individual growth processes was combined in a single model to assess potential mediational relationships among the variables in the stress-generation model. Finally, estimates of mediated effects (αβ) and the associated standard errors and 95 % confidence intervals were calculated to determine the significance of the mediated effects (MacKinnon 2008). Mediated effects were not bootstrapped on account of the following: (1) the sample size was large; (2) the distribution of αβ typically does not deviate substantially from normality; and, (3) bootstrapping is not available in Mplus when the hierarchical structure of the data is accounted for using TYPE = COMPLEX.

Model fit was assessed using χ 2 goodness-of-fit, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) with 90 % confidence interval. Adequate model fit was defined using the following thresholds: χ 2 p > 0.05, CFI >0.95, and RMSEA <0.06 (Singh 2009). If ≥ 2 indices met the threshold, fit was deemed adequate. Analyses conducted in this study implemented sampling weights based on the probabilities of selection and participation, developed by Statistics Canada to ensure comparability between the NLSCY and Canadian population. Each child’s final survey weight was adjusted for the survey design and non-response, and post-stratified by province, age, and sex to match known population totals (Statistics Canada 2007). Full information maximum likelihood was used to account for data assumed to be missing at random (Graham 2009).

Results

Children were aged 10.5 (SD 0.5) years and 52 % were male at the time of study entry. Eighteen percent had a chronic physical illness (asthma = 715; cerebral palsy = 41; diabetes = 47; epilepsy = 69; heart condition = 89; kidney condition = 35; other = 937) and these children were more likely to be male. Mothers were mostly married (83 %), 39 % had post-secondary education, and 16 % had household incomes of ≥ $80,000 per year. As shown in Table 1, CwCPI had lower self-esteem and more symptoms of anxiety and depression compared to healthy controls, d = 0.13 and 0.25, respectively. Mothers of CwCPI reported more symptoms of depression compared to mothers of healthy controls, d = 0.21.

In the first step to test the stress-generation model, separate latent growth curve models for each variable were specified to examine change over time and to ensure adequate fit for each specific element of the stress-generation model in both groups of children. As shown by the slope estimates for CwCPI in Table 2, symptoms of maternal depression and family dysfunction increased significantly over time, β = 0.50 and β = 0.21, p < 0.001 for both. A significant decline in child-reported self-esteem was also observed, β = -0.46, p < 0.001. Symptoms of anxiety and depression increased significantly over time, β = 1.02, p < 0.001. Similar results were obtained for healthy controls (Table 3): family dysfunction increased, β = 0.18, p = 0.007, self-esteem decreased, β = -0.47, p < 0.001, and symptoms of anxiety and depression increased, β = 1.00, p < 0.001. The one exception was that for healthy controls, symptoms of maternal depression decreased significantly over time, β = -0.14, p = 0.038. The non-significant variance in the slopes of maternal depressive symptoms (CwCPI and healthy) and family dysfunction (CwCPI) suggested that there was little inter-individual deviation from the average change in these constructs over time. Fit indices for each model were excellent.

Given the specification of the growth models and their adequate fit to the data, there was sufficient justification to combine each of the growth models and examine the potential mediational relationships within the full stress-generation model (Fig. 1). Because there was a significantly higher proportion of male CwCPI, the mediation model controlled for the potential confounding effects of child sex. Two of the three fit indices for the model were good: χ 2(51) = 527.11, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.958, and RMSEA = 0.030, 90 % CI [0.027, 0.032]. Examination of the direct effects demonstrated that chronic physical illness in childhood was significantly associated with increases in symptoms of maternal depression, increases in family dysfunction, declines in child self-esteem, and increases in symptoms of anxiety and depression in children over time. Statistically significant associations between increases in symptoms of maternal depression, β = 0.47, p = 0.025 and family dysfunction, β = 0.44, p = 0.015 and increases in symptoms of anxiety and depression in children were also found. Likewise, declines in child self-esteem were associated with increases in symptoms of anxiety and depression, β = -0.73, p < 0.001. All other pathways in the model were statistically significant and in the anticipated direction, with the exception of the association between changes in family dysfunction and child self-esteem, β = -0.01, p = 0.949.

Mediated effects assessed in the model are shown in Table 4. In the single-mediator pathways, changes in symptoms of maternal depression, family dysfunction, and child self-esteem all independently mediated the impact of chronic physical illness in childhood on symptoms of anxiety and depression. Although there was no difference in the magnitude of the mediating effect between symptoms of maternal depression and family dysfunction, the mediating effect of child self-esteem was found to be significantly larger than both symptoms of maternal depression, Δαβ = 0.52 [0.20, 0.85], and family dysfunction, Δαβ = 0.43 [0.09, 0.78]. In the two-mediator pathways, chronic physical illness in childhood was found to increase symptoms of maternal depression, resulting in increases in family dysfunction, and in turn, leading to increases in symptoms of anxiety and depression. Similarly, increases in maternal depressive symptoms leading to declines in child self-esteem were also found to mediate the impact of chronic physical illness on child symptoms of anxiety and depression. There was no significant difference in the magnitude of the mediating effect for these two pathways, Δαβ = −0.08 [−0.19, 0.03].

Discussion

Data from this population study suggest that children aged 10–15 years with chronic physical illness compared to their healthy counterparts are at-risk for more symptoms of anxiety and depression. This finding is consistent with a recent meta-analysis of children with a chronic illness compared to healthy controls and population norms (Pinquart and Shen 2011a). This study also demonstrated support for the stress-generation model linking chronic physical illness, symptoms of maternal depression, family dysfunction, and child self-esteem with symptoms of anxiety and depression in children. Whereas previous research has typically only examined two or three constructs at a time, this study tested five constructs simultaneously which allowed for the examination of multiple mediating pathways.

Our results are generally consistent with research on specific stress-generation model components, particularly among CwCPI. For example, in a sample of children with asthma, family functioning was found to mediate the effect of maternal depressive symptoms on child internalizing problems (Lim et al. 2011). Among children with epilepsy, family processes mediated the effect of maternal depressive symptoms on child health-related quality of life (Ferro et al. 2011). In the general population, there is also evidence that family functioning mediates the relationship between maternal depressive symptoms and child anxiety (Hughes et al. 2008) and that child self-esteem mediates the relationship between maternal depressive symptoms and symptoms of anxiety in children (Roustit et al. 2010). Because all of the pathways included in our model are taken into account (i.e., controlled), the mediating effect of child self-esteem on the relationship between family dysfunction on symptoms of child anxiety and depression may have been muted.

The role of child self-esteem in our study is an important finding. Researchers have developed a competency-based model of depression in children (Cole et al. 1997) which argues that children internalize competency-related feedback from others to form self-perceptions related to several domains, including academic competence, social acceptance, and physical appearance. Whereas positive self-esteem is linked to various developmental outcomes and is fundamental to coping with adversity, negative self-esteem places children at risk for anxiety and depression (Ginsburg et al. 1998; Pelkonen et al. 2008). Self-perceptions are inherent to self-esteem (Harter 1982) and recent studies have provided evidence supporting this mediational process (Class et al. 2012; Jacquez et al. 2004). In addition to documented evidence, the consistency and strength of effects observed in our study argues that the mediating role of self-esteem may be a causal effect.

Combined with previous research, this study provides some insight into the potential linkages among chronic physical illness, maternal depressive symptoms, family dysfunction, and child self-esteem on symptoms of anxiety and depression in children. The diagnosis of chronic physical illnesses in childhood can have a variety of adverse consequences for mothers (Brehaut et al. 2009), including added care requirements and costs for treatment (Burton and Phipps 2009), experiences of grief or stigma (Hobdell et al. 2007), and increases in the manifestation of symptoms of depression (Brehaut et al. 2011; Ferro and Speechley 2012; Gray et al. 2011). These symptoms of maternal depression can lead to declines in family functioning (Celano et al. 2008; Ferro et al. 2011), attributable in part to strains in parent-child relationships, marital discord, and financial stress (Reichman et al. 2004). Mothers with elevated symptoms of depression typically direct more negative expressed emotion at their children. In addition to being an indicator of family dysfunction, exposure to negative expressed emotion can result in declines in self-esteem and poorer psychological functioning in CwCPI (Hodes et al. 1999). The relationship between maternal depression and lower child self-competence may be attributable to shared genetic and environmental liability (Class et al. 2012).

Using a developmental approach, this study provided some evidence to suggest that changes in self-esteem preceded changes in symptoms of anxiety and depression in children. Because of its large effect and central developmental role, self-esteem may be considered a priority target for intervention to prevent the onset or reduce the severity of symptoms of anxiety and depression among CwCPI. In children and adolescents, with and without chronic physical illness, there is strong evidence that self-esteem can be markedly improved using a variety of interventions within home, school, community, or clinical settings (O’Mara et al. 2006). Interventions specifically focused on improving child self-esteem have had stronger positive effects on behavioral and academic functioning compared to interventions that took aim at other aspects of function such as social skills (Haney and Durlak 1998).

This research contributes to the growing literature of family influences on the mental health of CwCPI and support the implementation of family-centered care strategies, which have shown to be associated with improved outcomes for parents and CwCPI, including satisfaction with care and fewer child developmental problems (Law et al. 2003). In providing individualized care, clinicians should be attuned to the family climate and proceed with recommendations (e.g., screening, referral, treatment) on a case-by-case basis. Clinicians should openly discuss how maternal mood can affect child outcomes by impacting the family climate. Such actions may exert their effects upstream in the stress-generation model to reduce the impact of childhood chronic physical illness on mothers’ mental health and family functioning. At a more active level, clinicians might use the Psychosocial Assessment Tool to assess parent and family functioning in families (Pai et al. 2008). Routine screening and the provision of supportive resources may also help families adapt more positively to the hardships associated with childhood chronic physical illness potentially warding off child emotional-behavioral problems.

There is strong evidence to suggest that symptoms of anxiety and depression can be treated using a variety of interventions in children with (Beebe et al. 2010) and without chronic physical illness (Settipani and Kendall 2013; Sportel et al. 2013). Among CwCPI, modalities that aim to increase capacity and improve self-management capabilities can reduce symptoms of anxiety (Chiang et al. 2009; Vazquez and Buceta 1993). Additionally, there has been a call for family-focused interventions that will enable families to draw on supportive resources to help them adapt to having a CwCPI (Svavarsdottir and Rayens 2005). Preliminary evidence suggests that structured behavioral group training to reduce parental stress and improve parenting skills is associated with an improvement in symptoms of anxiety among children with diabetes (Sassmann et al. 2012).

This study has several limitations. First, the sample represents a narrow age range and the differential attrition among participants may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, the study relied on brief measures of self-esteem and anxiety and depression; however, our measure of self-esteem is reliable and invariant in children aged 10–19 years (Ferro and Boyle 2013a; Ferro and Boyle 2013b) and the measure of symptoms of child anxiety and depression is psychometrically sound (Boyle et al. 1993). Third, while evidence suggests the direction of effects stem from mother and family to child (Elgar et al. 2003; Lim et al. 2011), alternate models depicting reciprocal effects between child behavior and family processes are possible (Gartstein and Sheeber 2004; Trautwein et al. 2006) and warrant investigation. Sensitivity analyses assessing various alternate models with the current dataset demonstrated considerably worse model fit compared to the model presented (data not shown). Fourth, the association between child self-esteem and symptoms of anxiety and depression may have been enhanced by overlapping method variance. Fifth, pooling chronic physical illnesses may have tempered effect sizes. While Stein and Silver have shown that a non-categorical approach to studying childhood chronic physical illness is valid (Stein and Silver 1999), low counts for some conditions prevented formal tests of between-group differences. For example, effects may be larger for children with epilepsy because it is a neurological illness manifested physically through unpredictable seizures (Hoare and Mann 1994). However, recent meta-analyses have shown relatively little heterogeneity in problem behavior across conditions (Ferro and Boyle 2013c; Pinquart and Shen 2011b). Finally, the measure of chronic physical illness is non-specific for the relatively large proportion of adolescents in the “any other long-term condition” category.

Conclusion

Children with chronic physical illness are at-risk for elevated symptoms of anxiety and depression. The effects of childhood chronic physical illness on symptoms of anxiety and depression were mediated by symptoms of maternal depression, family dysfunction, and child self-esteem. Consistent with the stress-generation model, this study supports the use of family-centered care approaches for CwCPI, with particular emphasis on child self-esteem as antecedent to more serious psychopathology. Future research is needed to examine these mediational pathways in high-risk clinical populations, as well as investigate protective factors and their mechanisms leading to child resilience against symptoms of anxiety and depression. Further research is also needed to determine the extent to which symptoms of anxiety are normative or even adaptive for CwCPI. An important contribution to child and adolescent psychology would be intervention studies that target child self-esteem and family processes to determine whether the negative influences of chronic physical illness, low self-esteem, maternal depressive symptoms, and family dysfunction on symptoms of anxiety and depression in children can be minimized.

References

Auerbach, R. P., Bigda-Peyton, J. S., Eberhart, N. K., Webb, C. A., & Ho, M. R. (2011). Conceptualizing the prospective relationship between social support, stress, and depressive symptoms among adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol, 39, 475–487.

Bahreinian, S., Ball, G. D., Vander Leek, T. K., Colman, I., McNeil, B. J., Becker, A. B., & Kozyrskyj, A. L. (2013). Allostatic load biomarkers and asthma in adolescents. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 187, 144–152.

Beck, A. T., Emery, G., & Greenberg, R. L. (1985). Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive perspective. New York: Guildford Press

Beebe, A., Gelfand, E. W., & Bender, B. (2010). A randomized trial to test the effectiveness of art therapy for children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 126, 263–266.

Blackman, J. A., Gurka, M. J., Gurka, K. K., & Oliver, M. N. (2011). Emotional, developmental and behavioural co-morbidities of children with chronic health conditions. J Pediatr Child Health, 47, 742–747.

Boyle, M. H., Offord, D. R., Racine, Y., Fleming, J. E., Szatmari, P., & Sanford, M. (1993). Evaluation of the revised Ontario child health study scales. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 34, 189–213.

Brehaut, J. C., Kohen, D. E., Garner, R. E., Miller, A. R., Lach, L. M., Klassen, A. F., & Rosenbaum, P. L. (2009). Health among caregivers of children with health problems: findings from a Canadian population-based study. Am J Public Health, 99, 1254–1262.

Brehaut, J. C., Garner, R. E., Miller, A. R., Lach, L. M., Klassen, A. F., Rosenbaum, P. L., & Kohen, D. E. (2011). Changes over time in the health of caregivers of children with health problems: growth-curve findings from a 10-year Canadian population-based study. Am J Public Health, 101, 2308–2316.

Burton, P., & Phipps, S. (2009). Economic costs of caring for children with disabilities in Canada. Can Public Policy, 35, 269–290.

Byles, J., Byrne, C., Boyle, M. H., & Offord, D. R. (1988). Ontario child health study: reliability and validity of the general functioning subscale of the mcmaster family assessment device. Fam Process, 27, 97–104.

Cartwright-Hatton, S. (2006). Anxiety of childhood and adolescence: challenges and opportunities. Clin Psychol Rev, 26, 813–816.

Celano, M., Bakeman, R., Gaytan, O., Smith, C. O., Koci, A., & Henderson, S. (2008). Caregiver depressive symptoms and observed family interaction in low-income children with persistent asthma. Fam Process, 47, 7–20.

Chaney, J. M., Mullins, L. L., Uretsky, D. L., Pace, T. M., Werden, D., & Hartman, V. L. (1999). An experimental examination of learned helplessness in older adolescents and young adults with long-standing asthma. J Pediatr Psychol, 24, 259–270.

Chiang, L. C., Ma, W. F., Huang, J. L., Tseng, L. F., & Hsueh, K. C. (2009). Effect of relaxation-breathing training on anxiety and asthma signs/symptoms of children with moderate-to-severe asthma: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud, 46, 1061–1070.

Class, Q. A., D’Onofrio, B. M., Singh, A. L., Ganiban, J. M., Spotts, E. L., Lichtenstein, P., & Neiderhiser, J. M. (2012). Current parental depression and offspring perceived self-competence: a quasi-experimental examination. Behav Genet, 42, 787–797.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Cole, D. A., Martin, J. M., & Powers, B. (1997). A competency-based model of child depression: a longitudinal study of peer, parent, teacher, and self-evaluations. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 38, 505–514.

Costello, E. J., Egger, H., & Angold, A. (2005). 10-year research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. methods and public health burden. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 44, 972–986.

Datta, S. S., Premkumar, T. S., Chandy, S., Kumar, S., Kirubakaran, C., Gnanamuthu, C., & Cherian, A. (2005). Behaviour problems in children and adolescents with seizure disorder: associations and risk factors. Seizure, 14, 190–197.

Elgar, F. J., Curtis, L. J., McGrath, P. J., Waschbusch, D. A., & Stewart, S. H. (2003). Antecedent-consequence conditions in maternal mood and child adjustment: a four-year cross-lagged study. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol, 32, 362–374.

Ferro, M. A., & Boyle, M. H. (2013a). Brief report: Testing measurement invariance and differences in self-concept between adolescents with and without physical illness or developmental disability. J Adolesc, 36, 947–951.

Ferro, M. A., & Boyle, M. H. (2013b). Longitudinal invariance of measurement and structure of global self-concept: a population-based study examining trajectories among adolescents with and without chronic illness. J Pediatr Psychol, 38, 425–437.

Ferro, M. A., & Boyle, M. H. (2013c). Self-concept among children and adolescents with a chronic illness: a meta-analytic review. Health Psychol, 32, 839–848.

Ferro, M. A., & Speechley, K. N. (2009). Depressive symptoms among mothers of children with epilepsy: a review of prevalence, associated factors, and impact on children. Epilepsia, 50, 2344–2354.

Ferro, M. A., & Speechley, K. N. (2012). Examining clinically relevant levels of depressive symptoms in mothers following a diagnosis of epilepsy in their children: a prospective analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, 47, 1419–1428.

Ferro, M. A., Avison, W. R., Campbell, M. K., & Speechley, K. N. (2011). The impact of maternal depressive symptoms on health-related quality of life in children with epilepsy: a prospective study of family environment as mediators and moderators. Epilepsia, 52, 316–325.

Gannoni, A. F., & Shute, R. H. (2010). Parental and child perspectives on adaptation to childhood chronic illness: a qualitative study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry, 15, 39–53.

Gartstein, M. A., & Sheeber, L. (2004). Child behavior problems and maternal symptoms of depression: a mediational model. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs, 17, 141–150.

Ge, X., Conger, R. D., & Elder, G. H., Jr. (2001). Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Dev Psychol, 37, 404–417.

Ginsburg, G. S., La Greca, A. M., & Silverman, W. K. (1998). Social anxiety in children with anxiety disorders: relation with social and emotional functioning. J Abnorm Child Psychol, 26, 175–185.

Graham, J. W. (2009). Missing data analysis: making it work in the real world. Annu Rev Psychol, 60, 549–576.

Gray, K. M., Piccinin, A. M., Hofer, S. M., Mackinnon, A., Bontempo, D. E., Einfeld, S. L., & Tonge, B. J. (2011). The longitudinal relationship between behavior and emotional disturbance in young people with intellectual disability and maternal mental health. Res Dev Disabil, 32, 1194–1204.

Greenberg, P. E., Sisitsky, T., Kessler, R. C., Finkelstein, S. N., Berndt, E. R., Davidson, J. R., & Fyer, A. J. (1999). The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. J Clin Psychiatry, 60, 427–435.

Hammen, C. (1991). Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. J Abnorm Psychol, 100, 555–561.

Haney, P., & Durlak, J. A. (1998). Changing self-esteem in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Child Psychol, 27, 423–433.

Hankin, B. L., Mermelstein, R., & Roesch, L. (2007). Sex differences in adolescent depression: stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Dev, 78, 279–295.

Harter, S. (1982). The perceived competence scale for children. Child Dev, 53, 87–97.

Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1984). Nonparametric estimators of effect size in meta-analysis. Psychol Bull, 96, 573–580.

Hoare, P., & Mann, H. (1994). Self-esteem and behavioural adjustment in children with epilepsy and children with diabetes. J Psychosom Res, 38, 859–869.

Hobdell, E. F., Grant, M. L., Valencia, I., Mare, J., Kothare, S. V., Legido, A., & Khurana, D. S. (2007). Chronic sorrow and coping in families of children with epilepsy. J Neurosci Nurs, 39, 76–82.

Hodes, M., Garralda, M. E., Rose, G., & Schwartz, R. (1999). Maternal expressed emotion and adjustment in children with epilepsy. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 40, 1083–1093.

Holmes, A. M., & Deb, P. (2003). The effect of chronic illness on the psychological health of family members. J Ment Health Policy Econ, 6, 13–22.

Hoppe, C., & Elger, C. E. (2011). Depression in epilepsy: a critical review from a clinical perspective. Nat Rev Neurol, 7, 462–472.

Hoyert, D. L., Mathews, T. J., Menacker, F., Strobino, D. M., & Guyer, B. (2006). Annual summary of vital statistics: 2004. Pediatrics, 117, 168–183.

Hughes, A. A., Hedtke, K. A., & Kendall, P. C. (2008). Family functioning in families of children with anxiety disorders. J Fam Psychol, 22, 325–328.

Ialongo, N., Edelsohn, G., Werthamer-Larsson, L., Crokettn, L., & Kellam, S. (1996). Social and cognitive impairment in first-grade children with anxious and depressive symptoms. J Clin Child Psychol, 25, 15–24.

Jacquez, F., Cole, D. A., & Searle, B. (2004). Self-perceived competence as a mediator between maternal feedback and depressive symptoms in adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol, 32, 355–367.

Kercher, A., & Rapee, R. M. (2009). A test of a cognitive diathesis-stress generation pathway in early adolescent depression. J Abnorm Child Psychol, 37, 845–855.

Kim-Cohen, J., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Harrington, H., Milne, B. J., & Poulton, R. (2003). Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Genernal Psychiatry, 60, 709–717.

Law, M., Hanna, S., King, G., Hurley, P., King, S., Kertoy, M., & Rosenbaum, P. (2003). Factors affecting family-centred service delivery for children with disabilities. Child Care Health Dev, 29, 357–366.

Lim, J., Wood, B. L., Miller, B. D., & Simmens, S. J. (2011). Effects of paternal and maternal depressive symptoms on child internalizing symptoms and asthma disease activity: mediation by interparental negativity and parenting. J Fam Psychol, 25, 137–146.

MacKinnon, D. P. (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Hoboken: Erlbaum Psych Press

Marsh, H. W. (1992). Self Description Questionnaire (SDQ) I: A theoretical and empirical basis for the measurement of multiple dimensions of preadolescent self-concept. An interim test manual and research monograph. University of Western Sydney, Macarthur

Marshall, K. (2006). Converging gender roles. Perspect Labour Income, 7, 5–17.

McCaffery, J. M., Marsland, A. L., Strohacker, K., Muldoon, M. F., & Manuck, S. B. (2012). Factor structure underlying components of allostatic load. PLoS One, 7, e47246.

McClellan, C. B., & Cohen, L. L. (2007). Family functioning in children with chronic illness compared with healthy controls: a critical review. J Pediatr, 150, 221–223. 223 e221-222.

McEwen, B. S. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease. allostasis and allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 840, 33–44.

McLeod, B. D., Wood, J. J., & Weisz, J. R. (2007). Examining the association between parenting and childhood anxiety: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev, 27, 155–172.

Merikangas, K. R., Nakamura, E. F., & Kessler, R. C. (2009). Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues Clin Neurosci, 11, 7–20.

Msall, M. E., Avery, R. C., Tremont, M. R., Lima, J. C., Rogers, M. L., & Hogan, D. P. (2003). Functional disability and school activity limitations in 41,300 school-age children: relationship to medical impairments. Pediatrics, 111, 548–553.

Mullick, M. S., Nahar, J. S., & Haq, S. A. (2005). Psychiatric morbidity, stressors, impact, and burden in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Health Popul Nutr, 23, 142–149.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2010). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén

Newacheck, P. W., & Kim, S. E. (2005). A national profile of health care utilization and expenditures for children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 159, 10–17.

O’Mara, A. J., Marsh, H. W., Craven, R. G., & Debus, R. L. (2006). Do self-concept interventions make a difference? a synergistic blend of construct validation and meta-analysis. Educ Psychol, 41, 181–206.

Pai, A. L., Patino-Fernandez, A. M., McSherry, M., Beele, D., Alderfer, M. A., Reilly, A. T., & Kazak, A. E. (2008). The Psychosocial assessment Tool (PAT2.0): psychometric properties of a screener for psychosocial distress in families of children newly diagnosed with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol, 33, 50–62.

Patterson, J., & Blum, R. W. (1996). Risk and resilience among children and youth with disabilities. Arch Pediatric Adolesc Medicine, 150, 692–698.

Pelkonen, M., Marttunen, M., Kaprio, J., Huurre, T., & Aro, H. (2008). Adolescent risk factors for episodic and persistent depression in adulthood. a 16-year prospective follow-up study of adolescents. J Affect Disord, 106, 123–131.

Pinquart, M., & Shen, Y. (2011a). Anxiety in children and adolescents with chronic physical illnesses: a meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr, 100, 1069–1076.

Pinquart, M., & Shen, Y. (2011b). Behavior problems in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol, 36, 1003–1016.

Poulin, C., Hand, D., & Boudreau, B. (2005). Validity of a 12-item version of the CES-D used in the national longitudinal study of children and youth. Chron Dis Can, 26, 65–72.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measures, 1, 385–401.

Reichman, N. E., Corman, H., & Noonan, K. (2004). Effects of child health on parents’ relationship status. Demography, 41, 569–584.

Rolland, J. S., & Walsh, F. (2006). Facilitating family resilience with childhood illness and disability. Curr Opin Pediatr, 18, 527–538.

Roustit, C., Campoy, E., Chaix, B., & Chauvin, P. (2010). Exploring mediating factors in the association between parental psychological distress and psychosocial maladjustment in adolescence. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 19, 597–604.

Sassmann, H., de Hair, M., Danne, T., & Lange, K. (2012). Reducing stress and supporting positive relations in families of young children with type 1 diabetes: a randomized controlled study for evaluating the effects of the DELFIN parenting program. BMC Pediatr, 12, 152.

Settipani, C. A., & Kendall, P. C. (2013). Social functioning in youth with anxiety disorders: association with anxiety severity and outcomes from cognitive-behavioral therapy. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev, 44, 1–18.

Singer, G. H. (2006). Meta-analysis of comparative studies of depression in mothers of children with and without developmental disabilities. Am J Ment Retard, 111, 155–169.

Singh, R. (2009). Does my structural model represent the real phenomenon? a review of the appropriate use of structural equation modeling (SEM) model fit indices. Mark Rev, 9, 199–212.

Sportel, B. E., de Hullu, E., de Jong, P. J., & Nauta, M. H. (2013). Cognitive bias modification versus CBT in reducing adolescent social anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One, 8, e64355.

Statistics Canada. (2007). Microdata user guide: National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth, cycle 8 September 2008 to July 2009. Retrieved Feb 15, 2013, from http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb-bmdi/document/4450_D4_T9_V8-eng.pdf

Stein, R. E., & Silver, E. J. (1999). Operationalizing a conceptually based noncategorical definition: aa first look at US children with chronic conditions. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 153, 68–74.

Stein, R. E., Bauman, L. J., Westbrook, L. E., Coupey, S. M., & Ireys, H. T. (1993). Framework for identifying children who have chronic conditions: the case for a new definition. J Pediatr, 122, 342–347.

Svavarsdottir, E. K., & Rayens, M. K. (2005). Hardiness in families of young children with asthma. J Adv Nurs, 50, 381–390.

Trautwein, U., Ludtke, O., Koller, O., & Baumert, J. (2006). Self-esteem, academic self-concept, and achievement: how the learning environment moderates the dynamics of self-concept. J Pers Soc Psychol, 90, 334–349.

van der Lee, J. H., Mokkink, L. B., Grootenhuis, M. A., Heymans, H. S., & Offringa, M. (2007). Definitions and measurement of chronic health conditions in childhood: a systematic review. JAMA, 297, 2741–2751.

Vazquez, M. I., & Buceta, J. M. (1993). Effectiveness of self-management programmes and relaxation training in the treatment of bronchial asthma: relationships with trait anxiety and emotional attack triggers. J Psychosom Res, 37, 71–81.

Wallander, J. L., & Varni, J. W. (1998). Effects of pediatric chronic physical disorders on child and family adjustment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 39, 29–46.

Whittemore, R., Jaser, S., Chao, A., Jang, M., & Grey, M. (2012). Psychological experience of parents of children with type 1 diabetes: a systematic mixed-studies review. Diabetes Educ, 38, 562–579.

Witt, W. P., & DeLeire, T. (2009). A family perspective on population health: the case of child health and the family. Wis Med J, 108, 240–245.

Yen, C. F., Yang, P., Wu, Y. Y., & Cheng, C. P. (2013). The relation between family adversity and social anxiety among adolescents in Taiwan: effects of family function and self-esteem. J Nerv Ment Disord, 201, 964–970.

Zashikhina, A., & Hagglof, B. (2007). Mental health in adolescents with chronic physical illness versus controls in Northern Russia. Acta Paediatr, 96, 890–896.

Zimmer, K. P., & Minkovitz, C. S. (2003). Maternal depression: an old problem that merits increased recognition by child healthcare practitioners. Curr Opin Pediatr, 15, 636–640.

Zou, G. Y., & Donner, A. (2008). Construction of confidence limits about effect measures: a general approach. Stat Med, 27, 1693–1702.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Ferro was the recipient of a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Government of Canada and is currently supported by a Research Early Career Award from Hamilton Health Sciences. Dr. Boyle holds a Canada Research Chair (Tier I) in the Social Determinants of Child Health from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. While the research and analyses are based on data from Statistics Canada, the opinions expressed do not represent the views of Statistics Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferro, M.A., Boyle, M.H. The Impact of Chronic Physical Illness, Maternal Depressive Symptoms, Family Functioning, and Self-esteem on Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression in Children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 43, 177–187 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9893-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9893-6