Abstract

To investigate endorsement patterns among the 18 DSM-IV symptoms of ADHD in a longitudinal sample of children with and without ADHD (n = 144), as assessed at ages 4-5, 5-6, and 6-7 years. Symptom endorsements and diagnoses were determined at all time-points via K-SADS-PL interview administered to parents and supplemented by teacher questionnaires and clinician observations. Changes in endorsement patterns over time for each of the 18 DSM-IV symptoms were ascertained. Several symptoms, particularly those of inattention, were infrequently endorsed and of apparently limited diagnostic utility at ages 4-5; hyperactive/impulsive symptoms were more frequently endorsed among young children with ADHD than were inattentive symptoms. However, by ages 6-7, inattention items were somewhat superior at discriminating ADHD from Non-ADHD children. Several DSM-IV and now DSM-V symptoms provide limited diagnostic differentiation prior to school-age, particularly those most commonly observed in the context of formal schooling. Consideration should be made in future iterations of the DSM that account for such developmental and contextual differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is an impairing childhood psychiatric disorder, impacting roughly one in 20 school-age children (American Psychiatric Association 2000). ADHD commonly emerges during the preschool years and often persists into adulthood (Barkley et al. 2006). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition – Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association 2000) and DSM-V (American Psychiatric Association 2013) specify that a diagnosis in children be made via ascertainment of six of nine inattentive and/or hyperactive/impulsive behavioral characteristics that are present and impairing in at least two different settings.

Research supports the reliability and predictive validity of ADHD as early as 4 years of age through the application of DSM-IV-TR criteria (Egger et al. 2006b; Lahey et al. 2004; Lahey et al. 1998), with symptoms and impairment resembling those in later childhood (DuPaul et al. 2001; Greenhill et al. 2008). Nevertheless, DSM-IV/V behavioral indicators are largely descriptors of ADHD as it presents during the school-age years: children aged 4-5 comprised only 25% of the field study sample, adolescents 12 and older comprised another 25%, and school-aged children between 6 and 11 constituted the remaining 50% (Lahey et al. 1994). However, because the presentation of ADHD changes with development, and because certain symptoms are impacted by changing demands (e.g., formal school entry), the application of a single list of symptoms to all ages has raised concern (Chacko et al. 2009; Egger and Angold 2004, 2006). For instance, hyperactivity is predominant during the preschool years and becomes less evident throughout later childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (Biederman et al. 2000; Lahey et al. 2005). Additionally, application of school-age-based criteria to preschoolers can be problematic. For example, “Often makes careless mistakes” is difficult to assess in children who are not engaged in tasks or activities that require focused attention (e.g., homework, tests). In this regard, symptoms of inattention may have particularly poor sensitivity in preschool children who are not typically required to pay careful or sustained attention. While there are advantages to maintaining a single list of symptoms across age-groups, concern over the application and interpretation of certain individual symptoms in differential ages led to modifications in DSM-V to extend symptom descriptors to older (adult) individuals (American Psychiatric Association 2013). However, as far as their application to preschoolers, DSM-IV symptom criteria have not been changed.

The degree to which some ADHD symptoms may represent normative behavior in preschool children has also been debated; preschoolers are more active than older children, and children who are overly active as toddlers oftentimes normalize as they age (Campbell 2002; Romano et al. 2006). Fidgeting or squirming is common, regardless of diagnostic status, and has been suggested to be a less appropriate marker in preschool than in older children (Phillips et al. 2002). One review reported that, across studies, parents endorsed the ADHD symptom, “On the go,” in 2–72% of preschool children (Egger et al. 2006b). Thus, the specificity of DSM-IV hyperactivity symptoms may be problematic in preschool children because they are frequently reported in children with and without the disorder.

The DSM-IV and DSM-V address the issue of development by stating that for a symptom to be endorsed it must be “inconsistent” with the child’s developmental level (American Psychiatric Association 2000, 2013). As Egger et al. (2006a, b) pointed out, this requires clear delineation of what is developmentally appropriate. In the absence of such age-specific guidelines, ambiguity remains over what is considered normative versus pathological (Byrne et al. 2000).

Unease over how to interpret and apply these symptoms to young children is a familiar issue to many clinicians. Professionals and parents, alike, struggle to decide whether to treat early or whether a wait-and-see approach is more appropriate (Harvey et al. 2009). Clearly, the extent to which symptoms are impairing is an important issue in determining whether or not to treat. Nevertheless, some clinicians avoid diagnosing ADHD prior to age six altogether, potentially delaying much-needed treatment.

In recognition of these limitations, efforts have been made to revise symptom criteria for ADHD in this age group (Egger et al. 2006b; Task Force on Research Diagnostic Criteria: Infancy Preschool 2003). Inclusion of modified diagnostic criteria for preschoolers was considered, but was ultimately not adopted, by the committee developing the DSM-V (American Psychiatric Association 2012, 2013), This is in part because research examining the diagnostic utility of the 18 individual DSM-IV/V ADHD symptoms is remarkably sparse in preschoolers. Several studies have examined rates of parent and/or teacher endorsement of individual symptoms via rating scales (Egger et al. 2006b; Hardy et al. 2007; Phillips et al. 2002; Willoughby et al. 2012), and in general findings have indicated that hyperactive/impulsive symptoms are more relevant to ADHD than inattentive symptoms at this early age (Egger et al. 2006b; Hardy et al. 2007; Lahey et al. 2005). However, these studies were often limited by lack of diagnosed ADHD and comparison groups, and none used more rigorous interview techniques for symptom ratings. One preschool study employing clinical interview did not report individual symptom utility (Egger et al. 2006a; 2006b). While the DSM-IV field trials reported symptom utility based on interview, they included a much broader age range of children (Lahey et al. 1994).

To our knowledge, only one study has systematically assessed endorsement rates, ascertained via clinical interview, as indicators of relative utility of DSM ADHD symptoms during the preschool years. Byrne et al. (2000) found that several hyperactive/impulsive symptoms were endorsed frequently for children with and without ADHD (e.g., “Often talks excessively;” “Often interrupts or intrudes on others”), thereby suggesting high sensitivity but low specificity for these items. In contrast, far fewer children were reported as having certain symptoms of inattention (e.g., “Is forgetful in daily activities” was endorsed by only 20% of their ADHD sample), even though half of their ADHD sample met criteria for either the predominantly inattentive or combined type. The Byrne et al. (2000) study provides important empirical data on an issue otherwise largely informed by clinician experience and intuition. Nonetheless, it is limited by a small sample (25 ADHD and 25 Non-ADHD), the requirement that significant hyperactivity but not inattention be present for study entry (Hyperactivity T > 70 at screening), the fact that the ADHD sample was entirely clinically-referred, and that comorbid disorders including language delay and oppositional defiant disorder, both highly prevalent in preschoolers with ADHD, were excluded, limiting generalizability. However, the study does call attention to the notion that certain DSM-IV/V symptoms of ADHD may not be well suited to preschoolers. For a more empirically-grounded understanding of the utility of these symptoms among preschool children, investigation into this issue requires a larger, representative sample of preschool children, evaluated over time. Such a sample will allow for a better determination of the diagnostic utility of each ADHD symptom in preschool children, a critical yet understudied area of investigation.

The present study investigated endorsement patterns of the 18 DSM-IV (unchanged in DSM-V) ADHD symptoms in preschoolers from a larger, more community-based sample, including children with and without ADHD. Additionally, as part of a longitudinal study, data were collected at preschool age (ages 4-5), 1 year later (ages 5-6), and 2 years later (ages 6-7; early school-age), such that direct comparisons could be made within the same children over time.

We hypothesized that endorsement profiles of symptoms would differ between preschool- and school-age. We posited that: (1) certain symptoms, especially those related to school contexts, would be infrequently endorsed during preschool among ADHD as well as Non-ADHD children; (2) these symptoms would become more commonly endorsed among those with a diagnosis of ADHD by later years (ages 6-7), such that they would become better indicators of the disorder; and (3) in accordance with existing literature, hyperactive/impulsive (HI) symptoms, overall, would be stronger indicators of ADHD in preschool than inattentive (IN) symptoms, whereas by later in development this pattern would either disappear or skew in the reverse direction, with IN symptoms being stronger indicators of the disorder.

Method

Participants

The participants were children from a longitudinal study examining early risk factors for ADHD, for whom the Kiddie-Schedule of Affective Disorders – Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al. 1996) was administered at three annual time points: at ages 4-5 (T1), 5-6 (T2), and 6-7 years (T3). To ensure that the identical sample was compared at all times, children who missed one or more assessments were excluded. Of 188 children attending at T1, 38 missed one and six missed two of the subsequent assessments, yielding a sample size of 144. Occasionally children attended over 12 months past their prior appointment, and those who consequently “aged out” of their respective age bracket were included anyway (mean age at T1 = 5.32, SD = 0.51, range = 4.04–6.22; T2 mean = 6.34, SD = 0.50, range = 5.12–7.23; T3 mean = 7.36, SD = 0.52, range = 6.08–8.31).

Children were recruited 1 year prior to T1 as either “at-risk for ADHD” (AR) or “typically-developing” (TD) through community screening and direct referrals, to facilitate our achieving a wide range in symptom severity and to reach our target goal of a 2:1 ratio of AR:TD children. After obtaining permission from preschool principals in the surrounding area, parents of children ages 3-4 received materials inviting their participation, requesting they complete the ADHD-RS-IV, Home Version (DuPaul et al. 1998), and providing consent to collect the School Version of the scale from teachers. Similarly, parents and teachers of children referred to the study via schools and pediatricians for observed hyperactivity and attention problems were asked to complete the ADHD-RS-IV. Based on the questionnaires, children were entered into one of two groups: (i) TD (n = 76), defined by fewer than three of nine hyperactive/impulsive and inattention symptoms (rated either “Often” or “Very Often”) on both parent and teacher ADHD-RS-IV; or (ii) AR (n = 140), defined by at least six different symptoms (“Often” or “Very Often”) of either Hyperactivity/Impulsivity or Inattention across the Home and School Versions of the ADHD-RS-IV (e.g., a child could have four symptoms from the parent and two different symptoms from the teacher). Those not meeting criteria for either group (17% of those rated) were excluded from the longitudinal study. Other exclusion criteria at baseline were evidence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, a diagnosed neurological condition, Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Full Scale IQ less than 80 (ascertained via the Wechsler Primary and Preschool Scale of Intelligence – Third Edition, WPPSI-III; Wechsler 2002) at baseline), or use of medication for a chronic medical or psychiatric disorder, including ADHD. Parent and teacher rating scales were received for 529 children, of whom 400 met screening criteria (186 AR, 214 TD). After matching for sex (roughly 2:1 boy:girl ratio) and meeting our enrollment goal of 140 AR and 75 TD, we closed enrollment at 216. Of these 216, complete K-SADS-PL data were available at T1, T2, and T3 for 144 children, 59 of whom entered as TD and 85 of whom were identified as AR. A greater proportion of those children who completed all follow-up points had ADHD at baseline than did not (47 of 109 versus 25 of 107). Comparisons of Non-ADHD subjects who were and were not included revealed no significant differences in IQ, SES, or ADHD symptom severity. Comparisons of ADHD subjects who were included with those who were not revealed no significant differences in symptom severity or SES, but those not included had lower baseline IQ (p = 0.030). Nevertheless, the resultant sample was primarily middle class and ethnically and racially diverse, reflecting the urban region from which they were recruited. Among the sample, 71% were male; 59% were Caucasian, 12% were African American, 13% were of Asian descent, and 16% were of mixed racial background. 29% had at least one Hispanic parent.

Measures

ADHD Rating Scale-IV

(ADHD-RS-IV; DuPaul et al. 1998). The ADHD-RS-IV Home and School checklists consist of the nine inattention and nine hyperactive/impulsive items that comprise the ADHD symptom criteria in the DSM-IV. Each item is rated on a four-point scale (0 = never or rarely to 3 = very often). Parents and teachers completed the checklist for all children at screening and again at all follow-ups. The ADHD-RS-IV has demonstrated good reliability and validity both in preschoolers (McGoey et al. 2007) and school-age children (DuPaul et al. 1998). Coefficient alpha within our study across baseline, T1, T2, and T3 ranged from 0.948 to 0.962 on the Home version of the scale and from 0.962 to 0.966 on the School version.

Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia – Present and Lifetime Version

(K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al. 1996). The K-SADS-PL is a widely used, semi-structured interview for diagnosing psychiatric disorders in children that, for ADHD symptoms, inquires about the 6 months leading up to the interview. The K-SADS-PL was chosen over a preschool-specific instrument (Egger and Angold 2004) so that it could be repeatedly administered as children aged. Data suggest that the K-SADS-PL is reliable and valid for use in preschoolers (Birmaher et al. 2009). The K-SADS-PL allowed us to systematically evaluate each of the 18 DSM-IV ADHD symptoms. Coefficient alpha within our sample at T1, T2, and T3 ranged from 0.944 to 0.951.

Behavioral Rating Inventory for Children

(BRIC; Gopin et al. 2010). The BRIC is a brief checklist of ADHD-related behaviors based upon clinician observations that was shown to provide reliable and valid measures of ADHD-related behaviors to aid in diagnosis in the absence of teacher ratings. Test-retest reliability for the BRIC over a 1- to 2-week period, as assessed in the larger longitudinal sample from which this subsample was drawn, was 0.78.

Behavioral Assessment System for Children – 2nd Edition

(BASC-2, Reynolds and Kamphaus 2004). The BASC-2 is a widely used, standardized measure of clinical and adaptive dimensions of behavior. Parent and teacher versions were administered at each time point and the Attention Problems and Hyperactivity subscales are reported as independent indicators of sample characteristics.

Socioeconomic Status

The Nakao-Treas Socioeconomic Prestige Index (Nakao and Treas 1994) was used to assess socio-economic status (SES) at baseline. Mothers’ and fathers’ scores were separately coded and the higher of the two scores was adopted as an indicator of family SES. High scores on this index are indicative of higher SES.

Procedure

Parents of children who met screening criteria for either the AR or TD group were invited for evaluation. At this time, the nature and details of the longitudinal study were fully described to parents who then provided newly signed informed consent. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the College.

The K-SADS-PL was administered to parents at all three time points by well-trained graduate students who were blind to original group status and prior diagnoses. In addition, parent and teacher ADHD-RS-IV and BASC-2 ratings were collected annually. While parents were being interviewed, children received a neuropsychological test battery (lasting approximately 2.5–3 h) during which observations using the BRIC were obtained by well-trained graduate students who were blind to children’s status. Symptom endorsements and diagnoses according to DSM-IV criteria were formulated based on the K-SADS-PL interview, supplemented by teacher ADHD-RS-IV ratings, and under certain circumstances, clinician ratings on the BRIC. Specifically, a parent-endorsed symptom on the K-SADS-PL was always counted, regardless of teacher and observer ratings. If a parent endorsed subthreshold features of a symptom (i.e., present but not impairing), endorsement by a teacher (“often” or “very often” on the ADHD-RS) would suffice. Absence of a symptom according to parent report was overruled only when symptoms were strongly believed present, as based on clinician observation or a rating of “very often” on the ADHD-RS teacher form (Lahey et al. 1994). Although not common, in some circumstances where parents reported numerous, impairing symptoms, and teachers did not, or when teacher rating scales were unavailable, clinician observation of symptoms that interfered during testing were taken as evidence of cross-situationality. As specified in DSM-IV, evidence of cross-situationality of symptoms and impairment, as well as a persistence of symptoms for at least 6 months, were required for an ADHD diagnosis. All interviews were reviewed in supervision with a licensed psychologist, who provided oversight at an item-by-item level.

Data Analysis

For each of the 18 DSM-IV symptoms, we calculated the percentage among the ADHD and Non-ADHD groups for whom the symptom was endorsed at T1, T2, and T3; these will be referred to as “% ADHD endorsement” and “% Non-ADHD endorsement.” While analogous to assessing sensitivity and specificity, we refrained from using these terms due to the lack of independence between symptom endorsement and diagnostic status. Following the procedure employed by Byrne et al. (2000), we calculated “net endorsement” for each item: the percentage of ADHD participants for whom a given symptom was endorsed (i.e., % ADHD endorsement) minus percentage of Non-ADHD participants for whom the symptom was endorsed (% Non-ADHD endorsement) at each time-point. Byrne et al. (2000) proposed cuts in net endorsement to delineate High, (> 75%), Moderate, (50–75%), and Low (< 50%) discriminative value for items.

To test the hypothesis that certain symptoms might be differentially applicable at different ages, difference scores were calculated by subtracting % ADHD endorsement, % Non-ADHD endorsement, and net endorsement for each symptom at T1 from values obtained at T2; the same was computed by subtracting T1 from T3. As employed elsewhere (e.g., Fischer et al. 2008), an “appreciable difference” for specific items was defined as a change of 15% or greater.

To test the hypothesis that, as a complete domain, Hyperactivity/Impulsivity (HI) symptoms would be endorsed more frequently than Inattention (IN) symptoms at T1 but not at T3, 2-way mixed ANOVAs were run with Time (T1, T2, T3) being the within-groups variable and Symptom Type (IN versus HI symptoms) the between groups variable. % ADHD endorsement, % Non-ADHD endorsement, and net endorsement of symptoms within each domain served as the dependent measures.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Based on T1 evaluation, 44 children met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD (one of whom entered as TD) and 100 did not. Among those meeting criteria for ADHD at T1, four (9%), 24 (55%) and 16 (36%) met criteria for the predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive/impulsive, and combined type, respectively. Thirteen children who had five symptoms within a domain (12 AR, 1 TD) were included in the Non-ADHD group, in accordance with rigid adherence to threshold criteria (Lahey et al. 2005).

At T2, 49 children met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD; 95 did not. Among those with ADHD, nine (18%), 13 (27%), and 27 (55.1%) met criteria for the predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive/impulsive, and combined types, respectively. Eleven children had five symptoms within a domain and were considered Non-ADHD.

At T3, 56 children met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD and 88 did not. Among those meeting criteria at T3, 18 (32%), six (11%), and 32 (57%) had the predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive/impulsive and combined types, respectively. Eleven children with five symptoms in a domain were classified as Non-ADHD.

Table 1 shows descriptive characteristics of the ADHD and Non-ADHD groups at T1, T2, and T3. As can be seen, the groups differed slightly but significantly from each other at all time points with respect to baseline SES. There was a small (less than 3 months) but significant age difference between the groups at T1 and T3. As expected (Frazier et al. 2004), the ADHD group had significantly lower baseline IQ scores at T2 and T3) and was significantly more symptomatic at each time point, as measured by parent and teacher rating scales and clinical (K-SADS-PL) assessment.

Symptom Endorsement at Preschool Age (T1)

As shown in Table 2 (Column A), certain IN symptoms were endorsed in fewer than 50% of children with ADHD at T1 (e.g., “Avoids” = 34.1%; “Forgetful” = 45.5%; six of the nine symptoms were endorsed in fewer than two-thirds of the ADHD sample). In contrast, as shown in Table 3 (Column A), with the exception of “Difficulty playing quietly” (which was endorsed among only 47.7% of ADHD children), the remaining HI items were endorsed 70.5–95.5% of the time among those with ADHD. Only one IN symptom was endorsed more than 20% of the time in the Non-ADHD group (“Easily Distracted” = 21%), as opposed to four HI items. Applying the net endorsement guidelines described by Byrne et al. (Byrne et al. 2000), no symptoms, IN or HI, were classified as having High discriminative value (> 75% net endorsement) at T1. Five of the nine IN symptoms were found to be of Low value (< 50% net endorsement), with the remaining four meeting criteria for Moderate discriminative value. However, eight of nine HI symptoms had Moderate discriminative value; the remaining symptom, “Difficulty playing quietly” was of Low discriminative value.

Symptom Endorsement at T2

As seen in Table 2, Column B, shifts in endorsement patterns among children with ADHD led to a stronger profile of IN symptoms by T2, such that seven of the nine symptoms qualified as being of Moderate discriminative value, with two symptoms (“Avoids” and “Forgetful”) falling marginally short (net endorsement 48.6% and 49.7%, respectively). HI symptoms showed a similar profile, with seven of nine symptoms classifying as of Moderate value and two as Low (“Difficulty playing quietly” and “Talks excessively,” with net endorsement of 46.8% and 24.8%, respectively).

Symptom Endorsement at Early School-Age (T3)

As shown in Table 2, Column C, IN symptoms were increasingly endorsed among children with ADHD at T3. Only one IN symptom was classified as of Low value at T3 (“Avoids”). In contrast, four HI symptoms were of Low value by T3 (“Difficulty playing quietly,” “Talks excessively,” “Blurts out answers,” and “Interrupts or intrudes”). All other IN and HI symptoms fell within the Moderate range, with the exception of “Fidgets,” which reached the threshold for High discriminative value (net endorsement 75.2%).

Changes in Symptom Endorsement Over Time

T1 to T2

As described above, changes in individual symptom endorsement rates equal to or greater than 15% were taken as representing appreciable shifts (Fischer et al. 2008). Between T1 and T2, two symptoms of IN were found to increase appreciably in % ADHD endorsement and net endorsement: “Careless” and “Avoids.” The HI symptom, “Talks excessively,” showed an appreciable decrease.

T1 to T3

Changes were especially notable at T3 compared to T1 (see Tables 2 and 3, Column D). With regard to IN symptoms, five of the nine increased appreciably in endorsement rates. ADHD endorsement of “Careless,” increased 37.5% among children with ADHD and yielded a 31.3% improvement in net endorsement. “Does not follow through,” “Difficulty organizing,” and “Avoids” showed similar increases in % ADHD endorsement and net endorsement. “Difficulty sustaining attention,” which was already of Moderate discriminative value at T1, nevertheless increased appreciably in net endorsement. “Forgetful” was endorsed for appreciably more ADHD children at T3 than T1, although the change in net endorsement fell short of the threshold for an appreciable difference, and “Loses things” approached an appreciable increase in net endorsement.

Although the utility of “Talks excessively” no longer differed appreciably from T1 (in % ADHD or net endorsement) at T3, there were appreciable differences for four other HI symptoms. “Leaves seat,” “On the go,” “Blurts,” and “Difficulty waiting turn” were endorsed less frequently among ADHD children at T3 than at T1. Interestingly, despite reduced % ADHD endorsement, there was not an appreciable reduction in net endorsement for any of the HI items because rates of endorsement also declined in the Non-ADHD group.

Comparison of Symptom Domains Over Time

% ADHD Endorsement

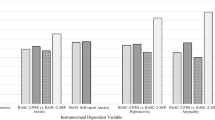

For endorsement among children with ADHD, two-way, mixed ANOVAs comparing Symptom Type (IN, HI) × Time (T1, T2, T3) revealed no main effect of Symptom Type, F(1,16) = 0.184, p = 0.674, ηp 2 = 0.011, or Time, F (2,32) = 1.640, p = 0.210, ηp 2 = 0.093. However, the Symptom Type × Time interaction was significant, F (2,32) = 28.629, p < 0.001, ηp 2 = 0.641. Post-hoc analyses revealed that, among children with ADHD, there was a significant increase in % ADHD endorsement of IN symptoms between T1 and T2 (p = 0.003), and a trend to the same effect between T2 and T3 (p = 0.063); across the three time points, mean % ADHD endorsement of IN symptoms rose from 58.3% at T1 to 76.2% at T3 (p < 0.001) (See Fig. 1). In contrast, there was a steady decrease in % ADHD endorsement of HI symptoms, such that by T3 HI items were endorsed significantly less frequently than at T1 (p < 0.001); T2 endorsement rates fell in between and did not differ significantly from either (p = 0.054 between T1 and T2; p = 0.054 between T2 and T3). HI symptoms were endorsed more frequently than IN symptoms among children with ADHD at T1 (p = 0.018). IN and HI symptoms no longer differed from one another in % ADHD endorsement at T2 (p = 0.882). By T3, IN symptoms tended to be endorsed more frequently than HI among children with ADHD (p = 0.068).

Mean percent endorsement among children with ADHD (% ADHD endorsement), children without ADHD (% Non-ADHD endorsement), and mean net endorsement (% ADHD endorsement - % Non-ADHD endorsement) for inattentive (IN) and hyperactive/impulsive (HI) symptom domains at three time-points (T1, T2, T3). Repeated measures ANOVAs of % ADHD endorsement and net endorsement yielded no significant main effects, but both yielded significant Symptom Type × Time interactions (p < 0.001 for both variables). For % Non-ADHD endorsement there was a significant main effect of Time (p = 0.017) and a Symptom Type × Time interaction (p = 0.001)

% Non-ADHD Endorsement

Among the Non-ADHD participants, a 2 × 3 ANOVA (Symptom Type × Time) revealed a main effect of Time, F(1,16) = 4.624, p = 0.017, ηp 2 = 0.224, as well as a Symptom Type × Time interaction, F(2,32) = 8.513, p = 0.001, ηp 2 = 0.347. Overall, % Non-ADHD endorsement decreased with time. Investigation into the interaction revealed that % Non-ADHD endorsement increased for IN items from T1 to T2 (p = 0.046) and leveled off by T3. In contrast, for HI items, there was a significant decline in % Non-ADHD endorsement between T1 and T3 (p = 0.003), as well as between T2 and T3 (p < 0.001), with no difference between T1 and T2. Thus, the endorsement patterns of IN and HI items among children without ADHD shifted in similar ways to the endorsement patterns among ADHD children. However, there was no significant difference in Non-ADHD endorsement rates of IN versus HI items at any of the three time points (see Fig. 1).

Net Endorsement

A 2 × 3 ANOVA (Symptom Type × Time) for net endorsement revealed no main effects of Symptom Type, F(1,16) = 0.003, p = 0.955, ηp 2 = 0.000, or Time, F(2,32) = 2.192, p = 0.128, ηp 2 = 0.121, but the interaction was significant, F(2,32) = 18.154, p < 0.001, ηp 2 = 0.532. Further investigation revealed a linear increase in net endorsement of IN symptoms between T1 and T3 (p = 0.001), from T1 to T2 (p = 0.010) and T2 to T3 (p = 0.031). In contrast, there was a significant drop in net endorsement of HI items between T1 and T3 (p = 0.002), with T2 endorsement falling in between (Fig. 1).

Comparisons of IN to HI net endorsement rates were similar to those of % ADHD endorsement. At T1, HI items had significantly greater net endorsement rates than did IN items (p = 024). By T2, net endorsement of IN and HI items was roughly similar (p = 0.659). However, by T3, the net endorsement rate of IN items was significantly greater than HI (p = 0.029).

Supplementary Analyses

Finally, to further examine the utility of the 18 individual ADHD symptoms at each of the three time-points, we completed 54 logistic regressions using each symptom as the predictor variable and diagnosis as the dependent variable. Supplementary Table 1 summarizes odds ratios for each of these regression analyses. As can be seen, in the younger age group (T1), odds ratios tended to be higher for HI symptoms, whereas by T3 they tended to be higher for IN symptoms. The symptom, “Fidgets or squirms,” had the highest odds ratios of any of the 18 symptoms at T1 as well as T3.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first study to systematically track endorsement patterns and utility of individual DSM ADHD symptoms from preschool through early school-age within the same sample of children. While many items appear apt descriptors of ADHD at all three time points, our findings provide evidence for differential utility of IN and HI items to identify young children with ADHD at difference ages.

The present findings replicate and expand upon those of Byrne et al. (2000), who reported Low discriminative value (<50% net endorsement) for four IN symptoms: “Careless Mistakes,” “Loses things,” “Forgetful,” and “Difficulty organizing” in a preschool sample. We similarly found poor utility during preschool for these items, as well as for a fifth item, “Avoids,” which was endorsed by just over a third of our ADHD sample at T1. However, we also found the discriminative value of these symptoms to improve by T3, three of the five by an appreciable amount and the other approaching the cut-off for an appreciable difference (14.8%, which was below our pre-selected threshold of 15%). By T3, only “Avoids” fell below 50% net endorsement. “Careless,” which showed very poor discriminative value at T2, improved by over 30% by T3 to be among the most discriminative of the IN symptoms. Thus, these items were good identifiers only once children were older.

The Task Force on Research Diagnostic Criteria: Infancy and Preschool (Task Force on Research Diagnostic Criteria: Infancy Preschool 2003) questioned certain DSM-IV items as well. Specifically, they suggested that “Careless,” “Forgetful,” “Driven by a motor,” and “Blurts out answers” were likely “developmentally inappropriate items,” but refrained from omitting them due to a lack of empirical evidence to support their intuitions. Our data supported the hypothesis that the former two IN symptoms may be of relatively weaker utility prior to school entry. We did not confirm problems for the latter two HI symptoms.

One reason for the limited utility of certain items in preschool may be that the behaviors are less evident in non-academic settings. For example, “Avoids tasks requiring sustained mental effort” and “Makes careless mistakes” cannot be gauged when children are not yet required to focus on attention-heavy material or be detail-oriented. It is possible that interview of teachers could have elicited responses that might increase the utility of inattention symptoms, as they observe children in the classroom. On the other hand, inattention (in contrast to hyperactivity) might also be observed more by parents (e.g., during homework time) than teachers, who may not notice a child whose mind is wandering. Additionally, responsibilities like organizing toys or activities, remembering obligations, and keeping track of belongings are not usually handled by very young children. Thus, our data provide evidence that certain symptoms are, as has been posited, developmentally improbable (Chacko et al. 2009). These symptoms had appreciably greater utility by the time children entered school-age. A reduced IN symptom threshold for ADHD diagnosis, as was adopted for both symptom domains by DSM-V for adults (American Psychiatric Association 2013), may be better suited to this young population as well, in that it might prevent the shift from hyperactive/impulsive to combined presentation that often occurs during the transition from preschool to school-age. Within our sample, 12 of the 24 children (50%) who met criteria for the hyperactive/impulsive subtype at T1 met for combined type at T3; of the remaining 12, five still met for hyperactive/impulsive type, three met for inattentive type, and four no longer met criteria for a diagnosis.

HI symptoms, which showed superior discriminative value to IN symptoms at ages 4-5, no longer outperformed IN items by ages 6-7. Four HI items were endorsed for appreciably fewer ADHD children by this later time point: “Leaves seat,” “On the go,” “Blurts out answers,” and “Difficulty waiting turn;” the symptom, “Runs or climbs,” showed a slightly less dramatic decrease. Thus, among children with ADHD, appreciably increased endorsement rates of IN symptoms were coupled with decreased endorsement rates of HI (a generally similar pattern was observed among Non-ADHD children, although endorsement rates did not change appreciably). These findings are not inconsistent with the epidemiological literature, which has suggested that HI symptoms often normalize, whereas high rates of early IN may predict later pathology (Galera et al. 2011; Romano et al. 2006).

“Difficulty playing quietly,” the one HI symptom identified as having Low discriminative value at T1, hardly changed in endorsement frequency with time, and remained the least discriminative HI symptom at T3. This symptom may therefore be of limited utility during preschool as well as early school-age. Three additional HI symptoms (“Talks excessively,” “Blurts,” and “Interrupts”) were of Low discriminative value at T3. Interestingly, these were all endorsed for a large portion of ADHD children at T1, yet they were also endorsed frequently in the Non-ADHD group as well (especially “Talks” and “Interrupts”) and consequently had among the lowest net endorsement rates among the HI symptoms at T1, in addition to at T3. Byrne et al. (2000) reported the same pattern for “Talks” and “Interrupts.” Given that net endorsement, according to our data, continued to decline for these symptoms by T3, they may occur frequently in all preschoolers, and, along with “Difficulty playing quietly,” be of limited utility during all time points. Further replication would be needed to confirm this possibility, as our data might also be influenced by the large number of symptomatic children in the Non-ADHD group. In contrast, the symptom identified as the most potent predictor of ADHD status at T1 as well as at T3, as indicated by the highest net endorsement and the highest odds ratios of any of the 18 symptoms, was “Fidgets or squirms.” Although this item was endorsed for a number of children without the disorder at T1 and T3, its sensitivity upward of 90% suggests that it is uncommon for 4 to 7 year-olds with ADHD not to present as excessively fidgety.

Unlike IN symptoms, which are less frequently observed, some argue that HI symptoms are too frequently reported in the young age group. However, our data do not support such an assertion. Rather, as measured by net endorsement, HI items were superior identifiers of ADHD at ages 4-5, whereas IN items were superior by ages 6-7. This was in part accounted for by the fact that, while four IN symptoms were of moderate value at T1, the remaining symptoms contributed less to the diagnosis.

Although not a central focus of this study, our data provide a unique perspective on changes in rates of ADHD over development. Epidemiological studies suggest that rates of ADHD in preschool children are somewhat lower than in older children, with estimates in preschoolers ranging from 2 to 5.7% (Egger et al. 2006b). However, such comparisons across age ranges have always come from cross-sectional comparisons, making it difficult to firmly conclude that the rate of ADHD actually increases across this age-range. While the non-representative nature of our sample in relation to the population precludes any statements regarding absolute prevalence rates, it is notable that within our sample of prospectively followed children with and without ADHD, the rate of ADHD increased systematically as the children moved from preschool- to school-age, suggesting that findings of lower rates in preschoolers are likely to be real. Further, consistent with findings that the hyperactive/impulsive subtype of ADHD is most commonly seen in younger children (75% of the DSM-IV field trial sample meeting criteria for this subtype were six or younger; Lahey et al. 1994), and with the longitudinal findings of Lahey et al. (2005) showing variations in subtypes over time, our sample demonstrated systematic changes in subtype patterns as children aged, with the rate of the hyperactive/impulsive type substantially decreasing with time, and the rate of the inattentive and combined types substantially increasing.

Our study had several strengths, most notably the longitudinal sample, which enabled us to evaluate endorsement rates and utility of symptoms at three time points in the same children. Nevertheless, some limitations should be mentioned. First, our sample did not include children who, at study entry, fell between our criteria for AR and TD groups as based on the ADHD-RS. This may have led to an artificial increase in the contrast between ADHD and Non-ADHD groups, as indicated by increased net endorsement. However, the percentage of children eliminated was relatively low (17%), and the bias was somewhat offset in that symptomatic (e.g., five ADHD symptoms within a domain) AR children were included in the Non-ADHD group. In fact, our net endorsement indices were lower than those reported by Byrne et al. (Byrne et al. 2000), suggesting that the effect of this filter may have been negligible.

A second limitation pertains to attrition. Our rates of attrition were comparable to those of other longitudinal studies of young children with ADHD (Arnett et al. 2012; Campbell et al. 1986; Lahey et al. 2005; Riddle et al. 2013) even with our requirement that children be present for all three time points to be included. However, a disproportionately high number of those lost to attrition (i.e., excluded for missing at least one time point) were those diagnosed with ADHD at BL, characterized by lower baseline IQ and lower SES. While it is likely that the resulting sample groups were representative of the populations they intended to represent, such differential attrition could potentially have had unmeasured effects.

Third, our symptom endorsement criteria were not independent of diagnostic decision-making. In other words, the symptoms assessed were also those applied toward diagnostic symptom counts. This lack of independence precludes us from investigating true sensitivity/specificity of symptoms. Thus, the present study should be taken as descriptive, and while “diagnostic utility” or “value” is used (Byrne et al. 2000) to assign relative worth to individual symptoms, generalization based on this descriptive approach should be made with caution. Another procedure-related limitation pertained to our non-inferential statistical approach. Despite the previously-described advantages of this approach, it did not allow us to quantify the possibility that differences observed were due to chance. For this reason, it is notable that the supplementary regression analyses highlighted similar trends in symptom endorsement over time.

A number of children (13 at T1 and 11 at T2 and T3) fell just short of the six-symptom threshold criterion, with five symptoms in a domain, and might be considered ADHD-Not-Otherwise-Specified (ADHD-NOS) and given a diagnosis in a clinic setting. A consideration, then, is that we included these children in the Non-ADHD group, and may thereby have inflated symptom endorsement rates in that group. While utilizing strict symptom counts is not unique to this study (Lahey et al. 2005), due to our recruitment process the rate of symptomatic Non-ADHD participants may have been disproportionately high. Including them in the ADHD group might have made our results more generalizeable clinically, but what we were interested in most was which features differentiated between children with by-the-book diagnoses and those who, along the continuum, fell shy (Hardy et al. 2007). Of course, this was compounded by the fact that a number of these children moved between ADHD and Non-ADHD groups, as movement above or below the six-symptom threshold is not uncommon (Lahey and Willcutt 2010). Seven (four hyperactive/impulsive, one inattentive, and two combined) of the original 44 children with ADHD at T1 no longer met diagnostic criteria by T3, although four of them still had five symptoms in a domain. In contrast, 19 children who did not meet criteria for ADHD at T1 did meet criteria at T3 (six of whom previously had five symptoms within a domain). Needless to say, our data highlight the substantial fluctuation in diagnostic profile over time. These age-related shifts reflect some of the difficulty in applying a categorical cut to a dimensional measure (Lahey et al. 2005; Lahey and Willcutt 2010).

Although cross-situational impairment was a requirement for a diagnosis of ADHD, and according to K-SADS-PL guidelines impairment is a requisite for symptom endorsement, we did not account for impairment severity, except to require that it be present. It is also worth noting that age 4-5 represents the upper end of the preschool age range, corresponding most closely to late preschool and early kindergarten. As such, it is possible, if not likely, that younger preschool-age children (e.g., ages 3-4) may differ even from those at T1. Although we recruited our sample at age 3-4, full K-SADS-PL interviews were not available for the entire sample, and thus systematic symptom comparisons could not be made until children were ages 4-5. The present results are best understood as trends in symptom endorsement over time, particularly because there was overlap in ages at each of the time points (e.g., some children were 5 years old at T1, whereas others were five at T2); consequently, it would be a mistake to draw conclusions about endorsement rates for a given age. With regard to K-SADS-PL interviews, although interviewer training and supervisory oversight was intensive, our lack of direct measurements of reliability is a limitation. Finally, the variety of types of preschools and levels of teacher training among them (e.g., licensed teachers versus daycare providers) may have influenced the way they completed questionnaires such as ours. Unfortunately, however, this cannot be prevented in this young age range.

Overall, our data are consistent with frequently described clinical observations and highlight important differences in the diagnostic utility of DSM symptoms of ADHD as a function of age. Compared with DSM-III-R, DSM-IV criteria for ADHD were found to identify significantly more preschool children (Byrne et al. 2000; Lahey et al. 1994). Whether this increase reflects an improvement in detection or an increase in false positives (poor specificity) in preschool is not clear. However, it highlights just how critical it is that symptoms be developmentally appropriate and empirically informed, particularly when it comes to the early age range, as this population may be especially sensitive to early intervention (Byrne et al. 2000; Halperin et al. 2012; Halperin and Healey 2011; Lahey et al. 1994). As we continue to learn more about the importance of early intervention and as new treatment options become available, accurate identification of ADHD as early as possible should be a goal.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (2012). DSM-V proposed revisions: Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Retrieved 5/1/2012, from http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=383.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Association.

Arnett, A. B., Pennington, B. F., Willcutt, E., Dmitrieva, J., Byrne, B., Samuelsson, S., et al. (2012). A cross-lagged model of the development of ADHD inattention symptoms and rapid naming speed. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(8), 1313–1326.

Barkley, R. A., Fischer, M., Smallish, L., & Fletcher, K. (2006). Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: adaptive functioning in major life activities. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(2), 192–202.

Biederman, J., Mick, E., & Faraone, S. V. (2000). Age-dependent decline of symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: impact of remission definition and symptom type. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(5), 816–818.

Birmaher, B., Ehmann, M., Axelson, D. A., Goldstein, B. I., Monk, K., Kalas, C., et al. (2009). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children (K-SADS-PL) for the assessment of preschool children – a preliminary psychometric study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(7), 680–686.

Byrne, J. M., Bawden, H. N., Beattie, T. L., & DeWolfe, N. A. (2000). Preschoolers classified as having attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): DSM-IV symptom endorsement pattern. Journal of Child Neurology, 15(8), 533–538.

Campbell, S. B. (2002). Behavior problems in preschool children: Clinical and developmental issues (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Campbell, S. B., Ewing, L. J., Breaux, A. M., & Szumowski, E. K. (1986). Parent-referred problem three-year-olds: follow-up at school entry. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 27(4), 473–488.

Chacko, A., Wakschlag, L., Hill, C., Danis, B., & Espy, K. A. (2009). Viewing preschool disruptive behavior disorders and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder through a developmental lens: what we know and what we need to know. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 18(3), 627–643.

DuPaul, G. J., Power, T. J., Anastopoulos, A. D., & Reid, R. (1998). ADHD Rating Scale-IV: Checklists, norms, and clinical interpretations. New York: Guilford.

DuPaul, G. J., McGoey, K. E., Eckert, T. L., & VanBrakle, J. (2001). Preschool children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: impairments in behavioral, social, and school functioning. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(5), 508–515.

Egger, H. L., & Angold, A. (2004). The preschool age psychiatric assessment (PAPA): A structured parent interview for diagnosing psychiatric disorders in preschool children. In R. DelCarmen-Wiggins & A. Carter (Eds.), Handbook of infant, toddler, and preschool mental assessment (pp. 223–243). New York: Oxford University Press.

Egger, H. L., & Angold, A. (2006). Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(3-4), 313–337.

Egger, H. L., Erkanli, A., Keeler, G., Potts, E., Walter, B. K., & Angold, A. (2006a). Test-retest reliability of the preschool age psychiatric assessment (PAPA). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(5), 538–549.

Egger, H. L., Kondo, D., & Angold, A. (2006b). The epidemiology and diagnostic issues in preschool attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a review. Infants and Young Children, 19, 109–122.

Fischer, A., Brooke, A., Liao, M., & Mosca, L. (2008). Physical activity as a potential mechanism through which social support may reduce cardiovascular disease risk. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 23, 90–96.

Frazier, T. W., Demaree, H. A., & Youngstrom, E. A. (2004). Meta-analysis of intellectual and neuropsychological test performance in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychology, 18(3), 543–555.

Galera, C., Cote, S. M., Bouvard, M. P., Pingault, J. B., Melchior, M., Michel, G., et al. (2011). Early risk factors for hyperactivity-impulsivity and inattention trajectories from age 17 months to 8 years. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(12), 1267–1275.

Gopin, C., Healey, D., Castelli, K., Marks, D., & Halperin, J. M. (2010). Usefulness of a clinician rating scale in identifying preschool children with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 13(5), 479–488.

Greenhill, L. L., Posner, K., Vaughan, B. S., & Kratochvil, C. J. (2008). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in preschool children. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 17(2), 347–366.

Halperin, J. M., & Healey, D. M. (2011). The influences of environmental enrichment, cognitive enhancement, and physical exercise on brain development: can we alter the developmental trajectory of ADHD? Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(3), 621–634.

Halperin, J. M., Bedard, A. C., & Curchack-Lichtin, J. T. (2012). Preventive interventions for adhd: a neurodevelopmental perspective. Neurotherapeutics, 9(3), 531–541.

Hardy, K. K., Kollins, S. H., Murray, D. W., Riddle, M. A., Greenhill, L., Cunningham, C., et al. (2007). Factor structure of parent- and teacher-rated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in the preschoolers with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder treatment study (PATS). Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 17(5), 621–634.

Harvey, E. A., Youngwirth, S. D., Thakar, D. A., & Errazuriz, P. A. (2009). Predicting attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder from preschool diagnostic assessments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(2), 349–354.

Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Brent, D. A., Rao, U., & Ryan, N. (1996). The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-age Children Present and Lifetime Version (Vol. 1.0). Pittsburg: Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburg School of Medicine.

Lahey, B. B., & Willcutt, E. G. (2010). Predictive validity of a continuous alternative to nominal subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder for DSM-V. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39(6), 761–775.

Lahey, B. B., Applegate, B., McBurnett, K., Biederman, J., Greenhill, L., Hynd, G. W., et al. (1994). Dsm-iv field trials for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 151(11), 1673–1685.

Lahey, B. B., Pelham, W. E., Stein, M. A., Loney, J., Trapani, C., Nugent, K., et al. (1998). Validity of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder for younger children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37(7), 695–702.

Lahey, B. B., Pelham, W. E., Loney, J., Kipp, H., Ehrhardt, A., Lee, S. S., et al. (2004). Three-year predictive validity of dsm-iv attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children diagnosed at 4-6 years of age. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(11), 2014–2020.

Lahey, B. B., Pelham, W. E., Loney, J., Lee, S. S., & Willcutt, E. (2005). Instability of the DSM-IV subtypes of ADHD from preschool through elementary school. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(8), 896–902.

McGoey, K. E., DuPaul, G. J., Haley, E., & Shelton, T. L. (2007). Parent and teacher ratings of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in preschool: the ADHD Rating Scale-IV preschool version. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29, 269–276.

Nakao, K., & Treas, J. (1994). Updating occupational prestige and socioeconomic scores: how the new measures measure up. Sociological Methodology, 24, 1–72.

Phillips, P. L., Greenson, J. N., Collett, B. R., & Gimpel, G. A. (2002). Assessing ADHD symptoms in preschool children: use of the ADHD Symptoms Rating Scale. Early Education and Development, 13, 283–299.

Reynolds, C. R., & Kamphaus, R. W. (2004). BASC-2: Behavior Assessment System for Children (2nd ed.). Circle Pines: American Guidance Service.

Riddle, M. A., Yershova, K., Lazzaretto, D., Paykina, N., Yenokyan, G., Greenhill, L., . . . Posner, K. (2013). The preschool attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder treatment study (PATS) 6-year follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(3), 264-278.

Romano, E., Tremblay, R. E., Farhat, A., & Cote, S. (2006). Development and prediction of hyperactive symptoms from 2 to 7 years in a population-based sample. Pediatrics, 117(6), 2101–2110.

Task Force on Research Diagnostic Criteria: Infancy Preschool. (2003). Research diagnostic criteria for infants and preschool children: the process and empirical support. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(12), 1504–1512.

Wechsler, D. (2002). Wechsler primary and preschool scale of intelligence - third edition (WPPSI-III). San Antonio: Harcourt Assessment.

Willoughby, M. T., Pek, J., & Greenberg, M. T. (2012). Parent-reported attention deficit/hyperactivity symptomatology in preschool-aged children: Factor structure, developmental change, and early risk factors. J Abnorm Child Psychol.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH R01-MH068286 to JMH. We acknowledge the statistical assistance of Drs. Yoko Nomura and Khushmand Rajendran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 81 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Curchack-Lichtin, J.T., Chacko, A. & Halperin, J.M. Changes in ADHD Symptom Endorsement: Preschool to School Age. J Abnorm Child Psychol 42, 993–1004 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9834-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9834-9