Abstract

This study examined associations of peer socialization and selection, over time, with nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) among 5,787 (54.2 % females) Chinese community adolescents. Both effects were tested using two aspects of adolescents’ friendship networks: the best friend and the friendship group. Participants completed questionnaires assessing NSSI, depressive symptoms and maladaptive impulsive behaviors at two waves of time over a 6-month period. Results showed that even after controlling for the effects of depressive symptoms and maladaptive impulsive behaviors, the best friends’ engagement in NSSI still significantly predicted adolescents’ own engagement in NSSI. Adolescents’ friendship groups’ NSSI status also significantly predicted their own NSSI status and frequency. Additionally, adolescents with NSSI tended to join peer groups with other members also engaging in NSSI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI), the socially unacceptable, deliberate, direct destruction of body tissue without conscious suicidal intent (Favazza 1998; Nock 2010), has become a major public health concern in adolescents (Jacobson and Gould 2007). The lifetime prevalence estimates for NSSI among adolescents vary from 5.5 % to 30.7 %, the 12-month prevalence rates vary from 7.5 % to 37.2 %, and the 6-month prevalence rates vary from 13.9 % to 16.3 % (Muehlenkamp et al. 2012). This large discrepancy in the prevalence estimates of NSSI may partly result from the different methodologies for assessing NSSI used across studies (i.e., single item vs. checklist vs. open-ended questions). NSSI is an indicator of various psychosocial disturbances and a potent predictor of suicide attempts in adolescents (Esposito et al. 2003; Jenkins et al. 2002; Muehlenkamp and Gutierrez 2007). Given the prevalence and clinical significance of NSSI, understanding why adolescents engage in this behavior is of particular importance.

Peer influence, or peer socialization, may be one of the sources of involvement in NSSI among adolescents (Heilbron and Prinstein 2008). Adolescents’ engagement in NSSI may be predicted by the extent to which they perceive that their peers engage in similar behaviors. Evidence supporting the peer influence effect on NSSI comes from clinical studies. For instance, Rada and James (1982) examined hospital records of acts of urethral self-injury by insertion of a foreign body in six male patients. Analysis of the temporal sequence of these self-injurious acts and relationships among the self-injurers indicated that each new incident occurred following direct personal contact with a previous self-injurer. Also using archival data, Ghaziuddin et al. (1992) reviewed psychiatric charts, social workers’ reports, school reports and nursing observations of a group of adolescent inpatients with self-cutting behaviors. Findings showed that two patients cut themselves as a pair on two occasions and two others cut themselves within 3 days following a similar incident on the unit. In another study, Walsh and Rosen (1985) prospectively recorded the occurrence or nonoccurrence of self-mutilation among 25 adolescent psychiatric patients over a 1-year period. Self-mutilation contagion was defined as two or more acts of self-mutilation that involved two or more individuals and occurred on the same day or consecutive days. Using sample run tests, this study confirmed that self-mutilative acts were bunched or clustered in time across participants, suggesting that the adolescents were triggering the behavior in each other or that staff or other peers’ responses to the act of NSSI led to the contagion. Using the same definition of contagion and the same methodology as in Walsh and Rosen’s study, the phenomenon of NSSI contagion was also demonstrated by Rosen and Walsh (1989) and by Taiminen et al. (1998).

Apart from using other informants’ (i.e., social workers, nurses and clinicians) reports, the peer influence effect on NSSI in adolescent psychiatric patients was also examined using participants’ self-reports of their own NSSI and their perceptions of friends’ NSSI. In a study by Prinstein et al. (2010), perceptions of friends’ self-injury was defined as the average percentage of friends who a) had attempted to kill themselves; b) had talked about wanting to hurt themselves or about suicide; and c) seemed down about themselves most of the time. This definition of friends’ self-injury was very broad, including not only NSSI but also suicide attempts and depression. After controlling for the effects of participants’ own depressive symptoms, path analysis showed that participants’ own NSSI was associated longitudinally with higher levels of perceptions of friends’ self-injury 9 months later. Perceptions of friends’ self-injury were also associated longitudinally with adolescents’ own NSSI 18 months later. Additionally, results suggested that both selection and socialization effects were moderated by gender; significant associations were revealed only in girls.

In addition to adolescent psychiatric patients, Prinstein et al.’s (2010) study also included adolescent students from Grades 6–8. Among this community sample, the frequency of NSSI within the past year was obtained for both participants and their best friends. Results from regression analysis suggested that even after controlling for depressive symptom as a longitudinal predictor for adolescents’ own NSSI, adolescents’ best friends’ independent reports of NSSI were still a significant longitudinal predictor. This effect was again found only in girls.

Other studies examining the peer influence effect on NSSI among community samples also reveal that peers’ NSSI is influential to ones’ own NSSI. For example, 38 % of adolescent participants with a recent history of NSSI in Deliberto and Nock’s (2008) study reported learning the behavior from peers. De Leo and Heller (2004) found among 3,757 high school students that participants’ self-reported exposure to deliberate self-harm (DSH) in friends or family increased the risk for their own engagement in NSSI more than three times. Hawton et al. (2002) reported an even larger effect of DSH in friends, which increased the risk for adolescents’ own DSH 5.17 times in girls and 6.99 times in boys. It should be noted, however, that the concept of DSH included both NSSI and suicide attempt.

Evidence for the peer influence effect on NSSI among nonclinical populations comes from not only self-report questionnaire studies, but also from experimental studies. In an experiment conducted by Berman and Walley (2003), participants were given the opportunity to self-administer electronic shock while competing with a single fictitious opponent in a reaction-time task. The intensity of participants’ self-administered electric shock was found to be positively associated with that of their peer “opponents”. When participants perceived that their peer “opponents” increased the intensity of the self-administered electric shock, they tended to increase their own shock intensity. Using the same competitive reaction time task as that in Berman and Walley’s study, Sloan et al. (2006) led participants to believe that they were completing the task with a group of four opponents rather than a single opponent. Participants were exposed either to high–, low–, or mixed–self–aggressive group normative information, or were provided no normative information. Results showed that participants’ selected shock intensity was largely influenced by group norms, such that participants being assigned to the high-self-aggressive group selected high shock intensity while those in the low-self-aggressive group selected low intensity.

The studies reviewed above suggest peer influence as one potential cause of adolescent NSSI. The mechanism and the importance of peer influence, however, are not clear. This may be partly due to several limitations of previous peer influence studies on NSSI. First, the majority of influence studies have not separated the effect of peer selection from that of peer socialization, or what might more generally be called “peer influence”. The peer selection effect refers to the fact that adolescents tend to select friends who are similar to themselves. The peer socialization effect, on the other hand, refers to the fact that peers’ engagement in specific behaviors may increase the likelihood of similar behaviors among others. Many of the studies reviewed above have documented the co-occurrence of NSSI among several individuals, but have not specifically suggested an active peer influence (socialization) effect on NSSI (De Leo and Heller 2004; Deliberto and Nock 2008; Ghaziuddin et al. 1992; Hawton et al. 2006; Rada and James 1982; Rosen and Walsh 1989; Taiminen et al. 1998; Walsh and Rosen 1985).

A second concern regarding previous peer influence studies on NSSI is that they did not include both aspects of adolescent’s peer group networks: the best friend and the friendship group. Some of them did not even distinguish the two aspects (e.g., Walsh and Rosen 1985). Although the best friends and the friendship groups overlap to some extent, they may exert differential influences on adolescents. On the one hand, if adolescents want to please or be like the close, intimate friends, these close friends would be very influential for adolescents. On the other hand, if adolescents want to feel a sense of belongingness to a group and participate in the experiences that are relevant to the group, the friendship group will be influential. Findings from existing studies indicate the dyad influence on NSSI within both clinical and nonclinical settings (Ghaziuddin et al. 1992; Prinstein et al. 2010; Rosen and Walsh 1989). With the exception of the experimental study conducted by Sloan et al. (2006), little data, however, has been reported on the friendship group influence on NSSI.

With the exception of Prinstein et al.’s (2010) study, a third limitation of previous studies is that they cannot rule out the possibility that “third variables” may explain the co-occurrence of NSSI among individuals. It is possible that the seeming contagion effect of NSSI is due to some common risk factors shared by individuals. Prinstein et al. controlled for one of the robust risk factors for NSSI in their study, depressive symptoms, and demonstrated that the best friends’ NSSI still affected adolescents’ own engagement in NSSI above and beyond the effect of adolescents’ depressive mood. Another risk factor of NSSI that needs special attention in studying peer influence effect is adolescents’ engagement in maladaptive impulsive behaviors (e.g., binge eating, alcohol abuse, substance abuse, and aggressive behaviors). This is not only because maladaptive impulsive behaviors have often been found to co-occur with NSSI in adolescents (De Leo and Heller 2004; Hawton et al. 2006; Hilt et al. 2008; Patton et al. 1997), but they have also been revealed as potent longitudinal predictors for NSSI (You and Leung 2012; You et al. 2012). Moreover, numerous studies have demonstrated peer involvement in maladaptive behaviors (e.g., substance use, alcohol use, cigarette smoking and sexual risk behavior), to be highly correlated with adolescents’ own involvement in such behaviors (Andrews et al. 2002; Henry et al. 2007; Urberg et al. 1997). Thus, it would be of interest to examine the peer influence effect on NSSI after controlling for adolescents’ engagement in maladaptive impulsive behaviors as a longitudinal predictor for NSSI.

To address the limitations of previous studies, the present study examined the association of peer selection and socialization with adolescent NSSI using two aspects of the adolescent’s friendship networks, the best friend and the friendship group, as predictors. We included gender as a moderator because gender differences have been found in both peer socialization and selection effects (Hawton et al. 2002; Prinstein et al. 2010). We also controlled for the effects of adolescents’ depressive symptoms and their engagement in maladaptive impulsive behaviors. Based on findings of previous studies, we hypothesized that both adolescents’ best friends and their friendship groups may exert socialization and selection effects on NSSI.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from eight co-educational high schools (five of the schools are Band 1 schools and the other three are Band 2 schools) distributed in eight districts in Hong Kong and were surveyed twice over a 6-month interval. We initially contacted these eight schools and because none of them declined to participate in this study, we did not contact other schools. At Time 1 (T1), 6,911 adolescents (52.6 % female) participated. Thanks to the cooperation of school authorities and their strong encouragement for their students to participate in this study, student participation rates were close to 99 % in all schools. Participants aged between 12 and 18 years (M = 14.63 years, SD = 1.25) and studied in Grades 7–11 at T1. At Time 2 (T2), 6,831 adolescents (52.6 % female) were included and 5,787 (54.2 % female) of them were retained from the T1 sample. The participant retention rate was 84.7 %. Attrition was mainly due to students transferring to other schools or being absent from school on the day of assessment. Comparisons between the retained and the attrited samples revealed no significant differences on all studied variables.

Procedure

All students from the participating schools were invited to participate in this study, yet participation was on a voluntary basis. We obtained written informed consent from participants’ parents before the testing. Both of the adolescent and parental informed consent rates were about 99 %. During each assessment, the same questionnaires were group administered in classrooms of 35–42 students under the supervision of school personnel. A unique ID number for each student was created for data-matching purpose. Participants were assured strict confidentiality of the collected data. Only research personnel had access to the questionnaires. All testing materials and procedures were approved by the Ethics in Human Research Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Measures

Nonsuicidal Self-injury (NSSI)

Seven NSSI behaviors, i.e., self-cutting, burning, biting, punching, scratching skin, inserting objects to the nail or skin, and banging the head or other parts of the body against the wall, were assessed in the present study. Participants were asked “In the past 6 months, have you engaged in the following behaviors to deliberately injure yourself but without suicidal intent?” All the seven NSSI behavior items were rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 “never”, 1 “once or twice”, 2 “three to five times” to 3 “six times or more”. A dichotomous variable of NSSI status was computed based on the seven items. It was coded “0” when participants endorsed “never” on all seven NSSI items, and it was coded “1” when participants reported having engaged in one or more NSSI acts. A continuous variable of NSSI frequency was also computed by summing up the scores of all seven items. This scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86 and 0.84 for the T1 and T2 data, respectively.

Maladaptive Impulsive Behaviors (MIB)

We assessed 10 maladaptive impulsive behaviors including binge eating, spending sprees, falling in love at first sight, verbal outbursts, physical fights, physical threats, physical assaults, property damage, alcohol abuse and substance abuse. These items were derived from the impulsivity section of the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R; Zanarini et al. 1989). Participants rated the frequency of engaging in these behaviors during the past 6 months using a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 “never”, 1 “once or twice”, 2 “three to five times” to 3 “six times or more”. This scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.69 for the T1 data and 0.73 for the T2 data in this study.

Depressive Symptoms (DEP)

We assessed depressive symptoms using the Chinese version of the Depression subscale of the short Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS21; Taouk et al. 2001). The DASS-21 has good convergent and discrimant validities (Antony et al. 1998). Sample items of the DEP included “I felt that life was meaningless”, “I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feelings at all”, and “I felt that I had nothing to look forward to”. Responses were made on a 4-point scale (0 = do not apply to me at all and 3 = apply to me very much or most of the time). This scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 and 0.86 for the T1 and T2 data, respectively.

Friendship Selection

To identify participants’ best friend and to define peer friendship groups, participants named a maximum of five of their close friends in the class (Urberg et al. 1997), starting with their most important friend, then the second best friend, and so on (Wang et al. 2006). Participants were free to nominate either same-sex or other-sex classmates as their best friends. They were instructed to put number one next to the name of their first best friend, and number two next to the name of their second best friend, and so forth.

Data Analysis

To examine the best friends’ influence on NSSI, we first identified reciprocated best friend dyads (i.e., both persons identified each other as the first best friend) within the T1 and T2 data, respectively. Within the T1 data, 1,223 reciprocated best friend dyads were identified. Within the T2 data, 1,506 dyads were identified. We randomly deleted one participant’s data in all cases of best friend reciprocity (i.e., 1,223 and 1,506 cases were deleted respectively for the T1 and T2 data). This was because in each case of reciprocated best friend dyad, participants’ data were used twice—once as the target participant and once as the very best friend (Prinstein et al. 2010). Deletion of the other half of the reciprocated best friends led to similar results to those reported below. The final T1 sample thus included 5,688 adolescents, with a mean age of 14.76 years (SD = 1.32). The final T2 sample included 5,325 participants, with a mean age of 15.23 years (SD = 1.76). Combining the reduced T1 and T2 datasets, we obtained a sample of 3,906 participants who completed both waves of assessment.

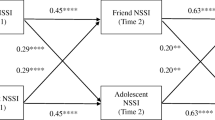

We then computed bivariate correlations among all study variables with the combined and reduced dataset (N = 3,906). To examine the best friends’ socialization and selection as predictors of NSSI status (frequency), we performed two separate longitudinal cross-lag logistic (multiple) regression analyses. To examine the best friends’ socialization effect, we used T2 participants’ own NSSI status (frequency) as the dependent variable. Independent variables included T1 participants’ own NSSI status (frequency) entered in an initial block, T1 participants’ own MIB and DEP scores entered in a second block, and T1 best friends’ NSSI status (frequency) entered in a third block. To examine the best friends’ selection effect, we used T2 best friends’ NSSI status (frequency) as the dependent variable. Independent variables included T1 best friends’ NSSI status (frequency) entered in an initial block, T1 best friends’ MIB and DEP scores entered in a second block, and T1 participants’ own NSSI status (frequency) entered in a third block. We also examined whether the best friends’ NSSI status at T1 predicted participants’ initiation of NSSI at T2 by performing another logistic regression. In this analysis, the dependent variable was membership in one of two groups: a) adolescents without NSSI at both T1 and T2 and b) adolescents without NSSI at T1 but initiating NSSI at T2. Independent variables included adolescents’ own MIB and DEP scores at T1 entered in the first block and the best friends’ NSSI status at T1 entered in the second block.

To examine the peer groups’ influence effects on NSSI, we first defined peer friendship groups separately for T1 and T2 data by conducting social network analysis using UCINET 6 (Borgatti et al. 2002). Friendship group members were adolescents belonging to a peer group of at least three persons (Paxton et al. 1999; Wang et al. 2006). The allocation to friendship group membership was restricted to members with reciprocal ties (bilateral nominations). If more than one group was eligible, membership was decided by position nomination of the members (i.e., giving more weight to friends who were nominated as closer friends). Independent sample t-tests comparing adolescents who were and were not assigned to a friendship group revealed no significant differences on all studied variables, indicating no average bias in participant selection. We defined the friendship group NSSI status as a dichotomous variable. It was coded “0” when all the other members of the group had no NSSI acts, and it was coded “1” when one or more of the other group members had NSSI behaviors.

To study the peer group selection and socialization effects on NSSI, we conducted three stages of analyses. First, we used analysis of variance to determine whether there was less within-friendship-group than between-friendship-group variance on NSSI status after consideration of the within-group similarities in NSSI correlates, i.e., MIB and DEP. Second, we examined cross-sectional correlations between friendship group NSSI status and friendship group means of MIB and DEP separately for T1 and T2 data. Third, as in examining the best friends’ socialization and selection effects, we performed two separate longitudinal cross-lag logistic regression analyses and two multiple regression analyses to examine peer group socialization and selection effects on the status and frequency of NSSI, respectively. Peer group socialization effect on NSSI status (frequency) was modeled by the effects of T1 friendship group NSSI status on T2 individual NSSI status (frequency), controlling for T1 individual NSSI status (frequency), MIB and DEP. Peer group selection on NSSI status (frequency) was modeled by the effects of T1 individual NSSI status (frequency) on T2 friendship group NSSI status, controlling for T1 friendship group NSSI status, MIB and DEP. Additionally, we conducted another logistic regression analysis examining whether friendship group NSSI status at T1 predicted participants’ own initiation of NSSI at T2. The dependent variable was membership in one of two groups: a) adolescents without NSSI at both T1 and T2 and b) adolescents without NSSI at T1 but initiating NSSI at T2. Independent variables included adolescents’ own MIB and DEP scores at T1 entering in the first block and the friendship group NSSI status at T1 entering in the second block.

Results

Descriptive Analyses of NSSI

Among the T1 sample, 12.7 % (n = 869) endorsed one or more of the seven NSSI behaviors in the past 6 months, with females (15.1 %, n = 546) being significantly more likely than males (10.0 %, n = 323) to conduct NSSI, χ 2 (1, N = 6,859) = 40.82, p < 0.001. Overall, about 44.4 % (n = 386) of the T1 self-injurers conducted NSSI once or twice in the preceding 6 months, while 55.6 % (n = 483) of them conducted NSSI repetitively (three times or more). Among the T2 sample, 9.2 % (n = 621) reported having engaged in at least one NSSI behavior in the past 6 months. Females (10.8 %, n = 382) were also significantly more likely than males (7.5 %, n = 239) to conduct NSSI, χ 2 (1, N = 6,749) = 22.23, p < 0.001. Among T2 self-injurers, about 38.3 % (n = 238) conducted NSSI once or twice in the preceding 6 months, and the other 61.7 % (n = 383) conducted NSSI repetitively. Additionally, 167 participants (3.1 % of the T2 sample) initiated NSSI at T2 (no NSSI at T1).

The Best Friends’ Influence Effects on NSSI

Table 1 presents bivariate correlations among all study variables. To reduce the likelihood of Type I errors, all correlation coefficients were only considered statistically significant with an alpha level of 0.001. Within both participants and their best friends, results revealed significant associations between NSSI status at T1 and T2, as well as significant relations of T1 NSSI status to T1 MIB, and to T1 DEP. Moreover, best friends’ NSSI status at T1 was significantly associated with adolescents’ own NSSI status at both T1 and T2. Adolescents’ own NSSI status at T1 was also significantly associated with best friends’ NSSI status at T2.

To examine the socialization and selection effects exerted by participants’ best friends on NSSI status and frequency, we conducted two separate longitudinal cross-lag logistic regressions and two multiple regressions as described in the Data Analysis section. We initially included gender as a moderator of the effects in all equations and age as a covariate. Since the main effects and the moderating effects of gender were not significant in any equations and results with and without age did not differ significantly, we removed gender and age from the final models.

Results for the two final logistic regression models predicting NSSI status are presented in Table 2. In the logistic regression model examining the socialization effect, T1 best friends’ NSSI status was significant in predicting T2 participants’ own NSSI status after controlling for T1 participants’ own NSSI status, MIB and DEP. This suggests that having a best friend who had engaged in NSSI at T1 may significantly enhance the risk for participants engaging in NSSI at T2. Regarding the peer selection effect, the result did not reach statistical significance. Youth who had engaged in NSSI at T1 did not tend to have a best friend at T2 who also engaged in NSSI.

Results for the two multiple regression models predicting NSSI frequency are presented in Table 3. In the multiple regression model examining the socialization effect on NSSI frequency, T1 best friends’ NSSI frequency was not significant in predicting T2 participants’ own NSSI frequency after controlling for T1 participants’ own NSSI frequency, MIB and DEP. Regarding the best friends’ selection effect, T1 participants’ own NSSI frequency was again not significant in predicting T2 best friends’ NSSI frequency after controlling for T1 best friends’ NSSI frequency, MIB and DEP. These results suggest that adolescents’ NSSI frequency was not significantly affected by their best friends’ NSSI frequency, and vice versa.

We also examined how the best friends’ NSSI status at T1 impacted the initiation of NSSI at T2 by conducting another logistic regression analysis. Results are summarized in Table 4. Results showed that the best friends’ NSSI status at T1 did not significantly differentiate between those who initiated NSSI later and those who did not. This suggests that the engagement in NSSI by participants’ best friends could not successfully predict participants’ own initiation of NSSI at T2.

The Friendship Groups’ Influence Effects on NSSI

Description of the Participants Being Selected into Friendship Groups

We indentified 647 friendship groups for the T1 data. Of the original T1 sample of 6,911 adolescents, 2,407 were selected into friendship groups. The friendship group sample, as compared to the non-friendship group sample, included significantly more girls (64.2 % vs. 46.5 %), χ 2 (1, N = 6911) = 196.27, p < 0.001; and older adolescents (mean age of 14.69 years vs. 10.61 years), t(6,881) = 3.94, p < 0.001. Friendship group sizes ranged from three to five adolescents: 51.5 % of the groups consisted of three, 28.3 % of four, and 20.2 % of five adolescents. The majority of friendship groups (90.4 %, n = 585) consisted of adolescents with the same sex. Among these same-sex friendship groups, 64.6 % (n = 378) were female groups and 36.4 % (n = 207) were male groups.

For the T2 data, 747 friendship groups were identified. Of the original 6,821 T2 participants, 2,779 were selected into friendship groups. The T2 friendship group sample also included significantly more girls (61.2 % vs. 46.7 %), χ 2 (1, N = 6911) = 139.18, p < 0.001, and older adolescents (mean age of 14.70 years vs. 12.83 years), t(6,821) = 2.32, p < 0.05, than the non-friendship group sample. Friendship group sizes ranged from three to five adolescents: 48.6 % of the groups consisted of three, 32.5 % of four, and 18.9 % of five adolescents. The majority of friendship groups (92.4 %, n = 690) consisted of adolescents with the same sex. Among these same-sex friendship groups, 60.7 % (n = 419) were female groups and 39.3 % (n = 271) were male groups.

A friendship group was considered stable if at least 50 % of the members at T1 were still together in a friendship group at T2. This is the same definition of group stability used by Urberg et al. (1997). Defined this way, 55.0 % (n = 356) of the T1 friendship groups were stable. Friendship group membership for an adolescent was considered stable if their T1 group was stable and they continued membership in that group. Defined this way, 41.6 % of adolescents were in stable groups from T1 to T2.

Intra- versus Inter-friendship Group Variability in NSSI

Because, within individuals, NSSI frequency was related to MIB and DEP, the possibility that members of friendship groups were similar on MIB and DEP was first considered. To examine this question, we conducted analyses of variance (ANOVAs) to compare within- and between-friendship group variance on these measures. Analyses were conducted separately for T1 and T2 data. For the T1 data, the ANOVA did indicate greater between-group than within-group differences in MIB, F(646, 1752) = 1.46, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.35, and DEP, F(646, 1706) = 1.35, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.34. Thus, MIB and DEP were entered as covariates in the analysis examining T1 NSSI status.

To ascertain whether members of friendship groups resembled one another with respect to NSSI status after controlling for group similarities observed on MIB and DEP, we performed an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) in which T1 NSSI status was the dependent variable and T1 MIB and DEP were entered as covariates. The ANCOVA was significant, F(646, 1691) = 1.17, p < 0.01, partial η 2 = 0.31, indicating significantly less within- than between-group variance in T1 NSSI status, despite significant covariation with MIB and DEP.

For the T2 data, the ANOVA also indicated greater between-group than within-group differences in MIB, F(746, 2032) = 1.25, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.31, and DEP, F(746, 2002) = 1.32, p < 0.01, η 2 = 0.33. Thus, MIB and DEP were entered as covariates in the analysis examining T2 NSSI status. As the analysis used with the T1 data, we performed an ANCOVA in which T2 NSSI status was the dependent variable and T2 MIB and DEP were the covariates. The ANCOVA was significant, F(746, 1969) = 1.17, p < 0.01, partial η 2 = 0.31, indicating significantly less within- than between-group variance in T2 NSSI status, despite significant covariation with MIB and DEP.

It was concluded that, independent of the psychological status of the groups, friendship groups could be characterized by their NSSI status.

Correlations Between Friendship Group NSSI Status and Friendship Group MIB and DEP

Since the previous analyses indicated that friendship groups could be characterized by NSSI status, we conducted correlation analyses to examine the association between friendship group NSSI status and friendship group MIB and DEP. Mean friendship group scores of MIB and DEP were used as characterizations for each group. As expected on the basis of the previous analysis with individuals, T1 friendship group NSSI status significantly (p < 0.001) correlated with T1 friendship group MIB at 0.44, and with DEP at 0.34. Similarly, T2 friendship group NSSI status correlated with T2 friendship group MIB at 0.43, and with DEP at 0.31 (p < 0.001 for both coefficients).

Peer groups’ Socialization and Selection Effects on NSSI

To examine the socialization and selection effects exerted by friendship groups on NSSI status and frequency, two longitudinal cross-lag logistic and multiple regression analyses were again conducted, respectively. Results for the logistic regressions are summarized in Table 5. In the logistic regression examining the socialization effect, T1 friendship group NSSI status was not significant in predicting T2 individual NSSI status after controlling for T1 individual NSSI status, MIB and DEP. This suggests that being in a group with other members having engaged in NSSI at T1 may not significantly enhance the risk for individuals engaging in NSSI at T2. Regarding the peer group selection effect, T1 individual NSSI status was significant in predicting T2 friendship group NSSI status after controlling for T1 friendship group NSSI status, MIB and DEP. Youth who had engaged in NSSI at T1 tended to join a peer group with other members also engaging in NSSI at T2.

Results for the multiple regression analyses are summarized in Table 6. Regarding the peer groups’ socialization effect on NSSI frequency, T1 friendship group NSSI status was significant in predicting T2 participants’ own NSSI frequency after controlling for T1 participants’ own NSSI frequency, MIB and DEP. This suggests that being in a group with other members having engaged in NSSI might increase adolescents’ own NSSI frequency. Regarding the peer groups’ selection effect, T1 individual NSSI frequency was also significant in predicting T2 friendship group NSSI status after controlling for T1 friendship group NSSI status, MIB and DEP.

We also examined whether the friendship group NSSI status at T1 influenced participants’ own initiation of NSSI at T2 by conducting another logistic regression analysis. Results are summarized in Table 7. Results showed that T1 friendship group NSSI status did not significantly differentiate between adolescents who initiated NSSI later and those who did not. This suggests that the engagement in NSSI at T1 by other members in adolescents’ friendship group could not successfully predict participants’ own initiation of NSSI at T2.

Discussion

This study examined the peer socialization and selection effects on adolescent NSSI as predicted from two aspects of adolescents’ friendship networks: the best friend and the friendship group. Regarding the socialization effects, after controlling for depressive symptoms and maladaptive impulsive behaviors, adolescents’ best friends’ NSSI status significantly predicted adolescents’ own NSSI status over a 6-month period. On the other hand, adolescents’ friendship groups’ NSSI status longitudinally predicted adolescents’ own NSSI frequency. Regarding the selection effects, adolescents with NSSI tended to join peer groups with other members also conducting NSSI. Adolescents with frequent NSSI might also be likely to join some peer groups with other members also engaging in NSSI frequently.

Best Friends’ Influence on NSSI

The best friends’ influence effect on NSSI revealed in this study is consistent with previous clinical reports and nonclinical studies (Ghaziuddin et al. 1992; Prinstein et al. 2010; Rosen and Walsh 1989). Clinical studies have documented that the contagion effect of NSSI occurred repeatedly for specific dyads. Our result is also in line with previous research revealing the best friends’ influence on other negative behaviors, such as smoking and alcohol use among adolescents (e.g., Harakeh et al. 2007; Urberg et al. 1997). Our finding of the best friends’ influence as a predictor of NSSI concurs with Bandura’s Social Learning Theory (Bandura 1986), indicating that individuals observe, model and imitate behavior of other important persons in their environment. According to this theory, the best friends set an example as a role model for adolescents, and therefore, their NSSI status may be predictive of adolescents’ own NSSI status.

This study also examines possible mechanisms through which adolescents’ own NSSI is related to their best friends’ NSSI. Previous studies suggest that adolescents with certain vulnerabilities, e.g., low self-esteem, may be especially likely to copy NSSI to deal with their problems (Claes et al. 2010). By including two frequently reported vulnerability factors of NSSI, i.e., depressive symptoms and maladaptive impulsive behaviors, this study showed that after controlling for the predictive abilities of both factors, the best friends’ NSSI was still longitudinally associated with adolescents’ own NSSI. This suggests that the association might not be due to adolescents’ depressive mood or impulsivity.

Another possible mechanism explaining the association between adolescents’ and their best friends’ NSSI may be the direct discussion of NSSI, which may serve as a behavioral reinforcement. Adolescents who are subject to their best friends’ influence and decide to continue NSSI might have difficulty with more conventional forms of intimacy. They may find discussion of and engagement in deviant acts, such as shared NSSI, to be compelling and exciting. These individuals may then be likely to use NSSI to ensure a tight bond within a relationship. It is also possible that teachers or other peers’ responses to the act of NSSI lead to the contagion. Teachers and/or other peers may give special attention and care to those who engage in NSSI. Adolescents who want others’ care and attention may then repeat this behavior.

The present study also tested gender differences in the predictive ability of the best friends’ socialization on NSSI, and revealed no significant findings. Previous studies demonstrated mixed results in this regard. Prinstein et al. (2010) found that the best friends’ socialization predicted NSSI in girls only, while Hawton et al. (2002) revealed that the association between peers’ and one’s own NSSI was stronger in boys than in girls. Additionally, we also revealed no significant age differences in predicting adolescents’ NSSI by their best friends’ NSSI. Perhaps other than gender and age, the family, school or community context are important in determining the strength of the association. It should also be noted that while significant, the bivariate correlations between the best friends’ and ones’ own NSSI status at T1 and T2 were quite small. This indicates that while important, there are also other variables related to the onset of NSSI.

Apart from examining the best friends’ socialization as a predictor on NSSI status, this study also examined its predictive utility on NSSI frequency. Results showed that adolescents’ NSSI frequency was not longitudinally associated with their best friends’ NSSI frequency. The frequency of NSSI might be predicted by other factors, e.g., psychological distress.

In this study, we examined not only the relation of the best friends’ socialization to adolescents’ NSSI but also the relation of the best friends’ selection to adolescents’ NSSI. Results showed that adolescents with NSSI did not tend to associate with best friends who were also engaging in NSSI. This may be because adolescents’ selection of best friends was based not only on shared deviant behaviors, but also on other personality features.

Friendship Groups’ Influence on NSSI

Apart from demonstrating the best friends’ NSSI as a predictor for adolescents’ own NSSI, this study was also the first one to examine the friendship groups’ NSSI status as a predictor for adolescents’ NSSI using a longitudinal design. We found that adolescents within friendship groups resembled each other with respect to NSSI, even after we considered their similarities on depressive symptoms and maladaptive impulsive behaviors. This similarity on NSSI may be due to friendship groups’ socialization effect. Although the friendship group NSSI status did not predict adolescents’ own NSSI status and initiation at a later time, it did predict adolescents’ NSSI frequency. This finding is consistent with that of the experimental study assessing group norms and self-administered electricity shock conducted by Sloan et al. (2006), as well as those of previous studies revealing significant group influence on other negative behaviors, such as binge eating, alcohol use and smoking (Crandall 1988; Urberg et al. 1997). This finding suggests that adolescents tend to conform to group norms regarding the engagement in NSSI.

The similarity on NSSI across group members may also be due to the selection effect, such that adolescents who had already engaged in NSSI tended to join a peer group with other members also engaging in NSSI. Given the relative scarcity of NSSI among community adolescents, self-injurers may regard their NSSI acts as weird and feel themselves as oddballs. They may thus want to join a group with self-injuring members to feel a sense of belongingness. Joining a self-injuring group may also reinforce and legitimize adolescents’ own NSSI behaviors.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study sheds light on the over time relation of peer socialization and selection to NSSI from adolescents’ best friends and friendship groups. This study made significant contributions to the extant literature. Several limitations, however, should be considered when interpreting findings of this study.

First, despite the large sample size, all participants in this study were Chinese high school students in Hong Kong. It is unclear to what extent one can generalize our findings to adolescents in other countries or cultures, or to populations of older ages. Additionally, school leavers were not included in this study and perhaps they should be, given that the out-of-school population tends to manifest increased psychopathology (Patton et al. 1997; Zweig et al. 2001) and also increased NSSI.

Second, some of the behaviors assessed for NSSI in this study were rather mild and considered to be “low severity” behaviors, e.g., self-biting. These behaviors are often excluded from studies examining more clinically relevant NSSI. Additionally, the frequency of NSSI was relatively low in this sample. Both factors may limit the generalizability of the present findings to clinical samples.

Third, in this study, participants were limited to selecting close friends from among their classmates. Given that adolescents often form significant and meaningful friendships outside of the classroom context, it follows that the reported friendships may not necessarily reflect adolescents’ closest relationships. It is thus worth to explore the peer influence effect of NSSI when participants are not limited to a classroom in their selection of close friendships.

Fourth, although we made attempts to control for preexisting risk factors for NSSI, i.e., depressive symptoms and maladaptive impulsive behaviors, it is possible that NSSI may have covaried with some other factors not assessed, such as interpersonal stressors, and these factors may also account for the peer influence effects on NSSI.

Last but not least, because of the time and budget constraints, this study followed the participants for only two waves over a 6-month period. It would be more fruitful if future studies could follow NSSI in adolescents and their friends for a longer period of time, as peer influence across several years may have a large cumulative impact (Berndt and Keefe 1995). Additionally, despite the longitudinal nature of the design, this study was still studying associations. Interpretation of the results should thus be made with caution.

Clinical Implications

Despite the limitations, this study has implications for school prevention and intervention programs for NSSI. First, given the socialization effects on NSSI from both adolescents’ best friends and friendship groups, school adolescents should be taught peer resistance skills in order to prevent NSSI. Specific peer resistance training programs working better with a close friend and working better in a group should also be designed separately. Second, since adolescents with NSSI tend to join NSSI groups, intervention program of NSSI may consider group intervention, such as social norm intervention (Perkins 2003).

References

Andrews, J. A., Tildesley, E., Hops, H., & Li, F. (2002). The influence of peers on young adult substance use. Health Psychology, 21, 349–357. doi:10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.349.

Antony, M. M., Bieling, P. J., Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., & Swinson, R. P. (1998). Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the depression anxiety stress scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment, 10, 176–181.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. New York: Prentice-Hall.

Berman, M. E., & Walley, J. C. (2003). Imitation of self-aggressive behavior: an experimental test of the contagion hypothesis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 1036–1057.

Berndt, T. J., & Keefe, K. (1995). Friends’ influence on adolescents’ adjustment to school. Child Development, 66, 1312–1329. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.ep9510075265.

Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., & Freeman, L. C. (2002). UCINET 6 for Windows: Software for social network analysis. Natik: Analytic Technologies, Inc.

Claes, L., Houben, A., Vandereycken, W., & Bijttebier, P. (2010). The association between non-suicidal self-injury, self-concept and acquaintance with self-injurious peers in a sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 33, 775–778. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.10.012.

Crandall, C. S. (1988). Social contagion of binge eating. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 588–598. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.55.4.588.

De Leo, D., & Heller, T. S. (2004). Who are the kids who self-harm? An Australian self-report school survey. Medical Journal of Australia, 181, 140–144.

Deliberto, T. L., & Nock, M. K. (2008). An exploratory study of correlates, onset, and offset of non-suicidal self-injury. Archives of Suicide Research, 12, 219–231. doi:10.1080/13811110802101096.

Esposito, C., Spirito, A., Boergers, J., & Donaldson, D. (2003). Affective, behavioral, and cognitive functioning in adolescents with multiple suicide attempts. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 33, 389–399.

Favazza, A. R. (1998). The coming of age of self-mutilation. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 186, 259–268.

Ghaziuddin, M., Tsai, L., Naylor, M., & Ghaziuddin, N. (1992). Mood disorder in a group of self-cutting adolescents. Acta Paedopsychiatrica, 55, 103–105.

Harakeh, Z., Engels, R. C. M. E., Vermulst, A. A., Vries, H. D., & Scholte, R. H. J. (2007). The influence of best friends and siblings on adolescent smoking: a longitudinal study. Psychology and Health, 22, 269–289. doi:10.1080/14768320600843218.

Hawton, K., Rodham, K., Evans, E., & Weatherall, R. (2002). Deliberate self harm in adolescents: self report survey in schools in England. British Medical Journal, 325, 1207–1211.

Hawton, K., Bale, L., Casey, D., Shepherd, A., Simkin, S., & Harriss, L. (2006). Monitoring deliberate self-harm presentations to general hospitals. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 27, 157–163. doi:10.1027/0227-5910.27.4.157.

Heilbron, N., & Prinstein, M. J. (2008). Peer influence and adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: a theoretical review of mechanisms and moderators. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 12, 169–177. doi:10.1016/j.appsy.2008.05.004.

Henry, D. B., Schoeny, M. E., Deptula, D. P., & Slavick, J. T. (2007). Peer selection and socialization effects on adolescent intercourse without a condom and attitudes about the costs of sex. Child Development, 78, 825–838. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01035.x.

Hilt, L. M., Nock, M. K., Lloyd-Richardson, E. E., & Prinstein, M. J. (2008). Longitudinal study of nonsuicidal self-injury among young adolescents: rates, correlates, and preliminary test of an interpersonal model. Journal of Early Adolescence, 28, 455–469. doi:10.1177/0272431608316604.

Jacobson, C. M., & Gould, M. (2007). The epidemiology and phenomenology of non-suicidal self-injurious behavior among adolescents: a critical review of the literature. Archives of Suicide Research, 11, 129–147. doi:10.1080/13811110701247602.

Jenkins, G. R., Hale, R., Papanastassiou, M., Crawford, M. J., & Tyrer, P. (2002). Suicide rate 22 years after parasuicide: cohort study. British Medical Journal, 325, 1155.

Muehlenkamp, J. J., & Gutierrez, P. M. (2007). Risk for suicide attempts among adolescents who engage in non-suicidal self-injury. Archives of Suicide Research, 11, 69–82. doi:10.1080/13811110600992902.

Muehlenkamp, J., Claes, L., Havertape, L., & Plener, P. (2012). International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 6, 1–9. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-6-10.

Nock, M. K. (2010). Self-Injury. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 339–363. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258.

Patton, G. C., Harris, R., Carlin, J. B., Hibbert, M. E., Coffey, C., Schwartz, M., et al. (1997). Adolescent suicidal behaviours: a population-based study of risk. Psychological Medicine, 27, 715–724.

Paxton, S. J., Schutz, H. K., Wertheim, E. H., & Muir, S. L. (1999). Friendship clique and peer influences on body image concerns, dietary restraint, extreme weight-loss behaviors, and binge eating in adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108, 255–266. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.108.2.255.

Perkins, H. W. (2003). The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse: A handbook for educators, counselors, and clinicians. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Prinstein, M., Heilbron, N., Guerry, J., Franklin, J., Rancourt, D., Simon, V., et al. (2010). Peer Influence and nonsuicidal self injury: longitudinal results in community and clinically-referred adolescent samples. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 669–682. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9423-0.

Rada, R. T., & James, W. (1982). Urethral insertion of foreign bodies: a report of contagious self-mutilation in a maximum-security hospital. Archives of General Psychiatry, 39, 423–429.

Rosen, P. M., & Walsh, B. W. (1989). Patterns of contagion in self-mutilation epidemics. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 146, 656–658.

Sloan, P. A., Berman, M. E., Zeigler-Hill, V., Greer, T. F., & Mae, L. (2006). Group norms and self-aggressive behavior. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25, 1107–1121.

Taiminen, T. J., Kallio-Soukainen, K., Nokso-Koivisto, H., Kaljonen, A., & Helenius, H. (1998). Contagion of deliberate self-harm among adolescent inpatients. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 211–217.

Taouk, M., Lovibond, P. F., & Laube, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of a Chinese version of the short Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS21). Sydney: New South Wales Transcultural Mental Health Centre, Cumberland Hospital.

Urberg, K. A., Degirmencioglu, S. M., & Pilgrim, C. (1997). Close Friend and group influence on adolescent cigarette smoking and alcohol use. Developmental Psychology, 33, 834–844. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.33.5.834.

Walsh, B. W., & Rosen, P. (1985). Self-mutilation and contagion: an empirical test. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 142, 119–120.

Wang, F., Moreno, Y., & Sun, Y. (2006). Structure of peer-to-peer social networks. Physical Review. E, Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics, 73, 036123. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.73.036123.

You, J., & Leung, F. (2012). The role of depressive symptoms, family invalidation and behavioral impulsivity in the occurrence and repetition of non-suicidal self-injury in Chinese adolescents: a 2-year follow-up study. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 389–395. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.07.020.

You, J., Leung, F., & Fu, K. (2012). Exploring the reciprocal relations between nonsuicidal self-injury, negative emotions and relationship problems in Chinese adolescents: a longitudinal cross-lag study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 829–836.

Zanarini, M. C., Gunderson, J. G., Frankenburg, F. R., & Chauncey, D. L. (1989). The revised diagnostic interview for borderlines: discriminating BPD from other Axis II disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 3, 10–18.

Zweig, J., Lindberg, L., & McGinley, K. (2001). Adolescent health risk profiles: the co-occurrence of health risks among females and males. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30, 707–728. doi:10.1023/a:1012281628792.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This research was supported in part by South China Normal University Young Teacher Research Cultivation Grant 2012KJ013 awarded to Dr. Jianing You.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

You, J., Lin, M., Fu, K. et al. The Best Friend and Friendship Group Influence on Adolescent Nonsuicidal Self-injury. J Abnorm Child Psychol 41, 993–1004 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9734-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9734-z