Abstract

The link between callous-unemotional (CU) traits in youth and delinquent, aggressive and violent behavior is well-replicated in the literature. However, the mediating effects of violence exposure on this relationship are unclear. The current study addresses this important gap in the literature with a sample of 88 detained, primarily ethnic minority adolescent boys (M age = 15.57; SD = 1.28). Results indicate that exposure to violence fully mediated the relationship between CU traits and violent delinquency, and this pattern of mediation was accounted for by exposure to witnessed violence, but not direct violent victimization. Secondly, exposure to violence, both direct and witnessed forms, also mediated the relationship between CU traits and drug delinquency. These findings suggest that (a) the well-established link between CU traits and violence may be attributed to high rates of witnessed violence among this subpopulation, and (b) specific types of violence exposure may be important for predicting the offending patterns of youth high on CU traits. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Callous-unemotional (CU) traits—theorized to be the childhood manifestation of adult psychopathy—distinguish a subset of youth with conduct problems who are characterized by a lack of remorse and empathy, uncaring behaviors, and an inability to express emotion (Christian et al. 1997; Frick 2006; Frick et al. 2000). Several studies find that CU traits are moderately stable from late childhood to early adolescence (Frick et al. 2003b; Muñoz and Frick 2007), and from adolescence to adulthood (Lynam et al. 2007, 2009). Compared with youth low on CU traits, antisocial youth high on CU traits present with a particularly severe and stable pattern of conduct problems and delinquent behavior (Frick et al. 2003a, 2005; Loney et al. 2007), tend to show greater substance-related delinquency (Taylor and Lang 2005), and show higher rates of aggression, and violent and sexual offending (Caputo et al. 1999; Frick and White 2008). In their review of 24 published studies, Frick and Dickens (2006) found consistent support for an association between CU traits and more severe conduct problems, delinquency, violence and aggression. Antisocial youth scoring high on CU traits also show different risk factors and correlates compared to youth scoring low, such as greater thrill-seeking and a reward dominant response style (Frick et al. 1999), insensitivity to punishment (see Frick and White 2008) and poor recognition of and attention to others’ distress cues (Blair 1999; Kimonis et al. 2006), suggestive of a divergent developmental pathway to their antisocial behavior (Frick 2009).

Although much research attempting to understand the developmental origins of CU traits focuses on biological-temperamental factors—with compelling evidence to suggest a strong genetic basis (Larson, Andershed, & Lichtenstein, 2006; Taylor et al. 2003; Viding et al. 2008)—there are also important environmental factors associated with CU traits and psychopathy. For example, Porter (1996) theorized that a secondary variant of psychopathy develops due to the “deactivation” of a developing affective conscience through a dissociative process, following trauma exposure such as abuse or maltreatment. (It is important to acknowledge evidence of genetic contributions to environmental factors such as exposure to trauma, e.g., Jang, Stein, Taylor, Asmundson, & Livesley, 2003). In contrast, the primary variant of psychopathy is theorized to be born without the ability to form affective bonds. In the mid twentieth century, Karpman (1941) theorized the existence of a trauma-based etiological pathway to psychopathy. Several studies have since documented a link between psychopathic traits and childhood trauma. For example, in their seminal longitudinal study of 652 young adults, Weiler and Widom (1996) found that individuals with a legally documented history of childhood abuse/neglect were significantly more likely than a matched control sample of 489 individuals without a documented history of maltreatment to develop psychopathic traits and violent behavior approximately 20 years later (see also Bernstein et al. 1998; Campbell et al. 2004; Krischer and Sevecke 2008). Similarly, developmental research indicates that trauma exposure (abuse, neglect) during toddlerhood is associated with early affective deficits consistent with CU traits, namely a lack of empathy and concern for others (Main and George 1985).

A considerable proportion of individuals with a history of maltreatment, particularly that occurring at a young age, are re-victimized later in development (Thompson and Wiley 2009). When these youth are also high on CU traits they may be at even greater risk for repeated victimization given evidence that they tend to elicit more punitive parenting practices (Hawes et al. 2011; Muñoz et al. 2011). Youth high on CU traits may also be more likely to enter into situations that place them at risk for exposure to dangerous and violent experiences as witnesses, given their thrill and novelty seeking tendencies (Frick et al. 1999). In a prior investigation with the present sample, exposure to community violence was significantly positively associated with CU traits (r = 0.38) (Kimonis, Frick, Munoz, and Aucoin 2008); however it is not clear to what extent this association is specific to exposure to direct victimization versus witnessed violence.

Some researchers suggest that chronic exposure to witnessed violence affects the normative development of empathy and morality, resulting in an uncaring and callous personality (Farrell and Bruce 1997; Fitzpatrick 1993). Witnessing violence may also lead to desensitization to others’ distress cues, a deficit common to youth with CU traits. Only rigorous longitudinal research can adequately address whether violence exposure leads to the development of CU traits or vice versa. However, witnessed violent events recalled by adolescents may be more temporally proximal and less likely to have occurred prior to the onset of CU traits, which are observable as early as the preschool years when moral development occurs (Kimonis et al. 2006a; Willoughby et al. 2011). The purpose of the present study was less to understand the temporal ordering of these variables but rather to determine whether exposure to violence accounts for why some individuals high on psychopathic traits engage in more violent forms of delinquency whereas others engage in more nonviolent forms.

Thus, research suggests CU traits are associated with both a) more severe and violent offending and b) greater rates of direct victimization and witnessed violence. What has not been the focus of much research is whether or not the victimization and exposure to violence accounts for the offending patterns in those with CU traits. Specifically, exposure to violence is an important risk factor for aggressive and violent behavior. Social learning theory suggests that violence exposure plays a significant role in shaping the integration and transmission of violent behavior (Bandura 1977; Widom 1989). This viewpoint suggests that if a youth witnesses or experiences violent acts, he or she in turn is more likely to later engage in violence. Consistent with this theory, research finds that a history of childhood abuse and witnessing of severe violence is associated with later violent behavior, including sexual offending, particularly among youth high on CU traits (Caputo et al. 1999). Furthermore, juveniles adjudicated of a sexual offense are more likely to report a history of both physical abuse and witnessing of family violence, compared with non-sexual offenders (Ford and Linney 1995; Righthand and Welch 2001). Thus, it is possible that violence exposure could mediate the well-established link between CU traits and violent and sexual offending.

Youth who are directly victimized or exposed to witnessed violence are also more likely to engage in drug delinquency (Mrug and Windle 2009; Simpson 2002). It has been suggested that ongoing exposure to stress or traumatic abuse increases susceptibility to abuse substances (Breslau et al. 2003; Piazza and Le Moal 1996; Simpson and Miller 2002). Although substance use is moderately associated with psychopathic traits, generally (Taylor and Lang 2005), research suggests a stronger link with secondary psychopathy (Blackburn and Coid 1998; Skeem et al. 2007; Smith and Newman 1990; Vassileva et al. 2005). Given high rates of trauma exposure and anxiety among secondary variants of psychopathy (Poythress and Skeem 2005), these individuals would be likely to use substances for their anxiety-reducing effects and ability to numb feelings of emotional distress associated with traumatic events. Further, substances affect reward systems of the brain (e.g. amygdala, nucleus accumbens; Volkow and Fowler 2000), which are particularly sensitive among secondary psychopathy variants who are theorized to have an overactive behavioral activation system (BAS; Newman et al. 2005; Lykken 1995). Thus, it is likely that traumatic life events, which are common to secondary psychopathy variants, will fully account for the link between CU traits and drug delinquency.

The Present Study

Despite the established link between CU traits and delinquency, there has been relatively little study of potential mediating factors between them, such as violence exposure, which may offer important theoretical insights. While environmental factors may be less associated with the underlying cause of CU traits (Viding et al. 2008), they may be helpful for understanding the mechanisms by which these youth come to engage in distinct patterns of offending. The present study moves the field forward by addressing the possible mediating effects of victimization and violence exposure on CU traits and patterns of delinquency. The primary aims of the present study were to test whether violence exposure (a) accounts for the association between CU traits and violent forms of delinquency, including sexual delinquency and (b) also mediates the link between CU traits and drug delinquency.Footnote 1 There is little rationale to expect that violence exposure would explain the link between CU traits and non-violent forms of delinquency (i.e., property), however, this outcome was included in analyses described below for exploratory purposes. It was hypothesized that CU traits would be associated with property delinquency given consistent prior research findings (e.g., Frick et al. 2003a, 2005). A second exploratory aim was to examine the independent contributions of witnessed violence and direct victimization, separately, to these mediating processes.

Method

Participants

Participants included 88 male adolescents between the ages of 13 and 18 (M = 15.57; SD = 1.28) detained in a juvenile detention center for youth who have committed a variety of delinquent acts. The participants were a subset of 102 males who provided assent to participate and whose parents also provided consent. Thirteen males were excluded from the study because they showed impaired verbal abilities (scores below 66) on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Third Edition (PPVT-III; Dunn and Dunn 1997), making it unclear wether they could understand the study questionnaires and another was unable to complete questionnaires. The mean PPVT score of the final sample fell approximately one standard deviation below average at 85.6 (SD = 13.5).

The majority (68 %) of the sample self-identified as African American and 23 % as Caucasian, which is representative of the broader ethnic composition of the detention center population. Additionally, 4.5 % of the sample identified as Hispanic, 2.3 % as Native American, and 2.3 % as “Other.” The most common family structure reported by participants was living with a biological mother alone (45 %), followed by living with a biological mother and step-father (25 %), living with both biological parents (8 %), living with a biological father and step-mother (8 %), living with a biological father alone (5 %), and other living arrangements (5 %). Participants reported an average of 2.75 (SD = 1.38) siblings living in the home with them prior to being detained. Based on self-report, 17 % were prescribed psychotropic medication, 50 % were placed in special education classes in school, and 69 % had a history of mental health treatment. According to a review of their detention center records, 59 % of youth had either a current arrest for a violent offense or a history of at least one violent arrest and the sample had an average of 6.08 (SD = 5.57, Range = 0–28) previous arrests.

Procedures

All procedures were approved by a university Institutional Review Board. A staff member from the detention center contacted the parents or legal guardians of all detained youth to inform them of a study being conducted at a local university and to ask their permission to forward their contact information to the researchers. Of the 126 parents contacted, nine parents declined their child’s participation. Researchers met with the remaining youth in a private room at the detention center to request their assent to participate; ten youth declined participation. Five additional youth were released from the facility before assent could be obtained.

Youth participating in the study were individually administered a demographic interview followed by a questionnaire requiring him to report on his ethnicity. Later in the day, and at least half an hour following the initial session, boys were escorted in groups to a larger visitor’s room (groups ranged from one to four youth), where they were read questionnaires by a researcher, with an assistant available to help answer participant questions and to ensure that each participant was working independently and completed every item. The group was compensated for their participation with a choice of refreshment (i.e., soft drink and candy bar).

Measures

Callous-unemotional Traits

CU traits were assessed using the 24-item Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits (ICU; Frick 2004). Items (e.g., “I do not show my emotions to others”) are rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all true) to 3 (definitely true). The construct validity of the ICU was supported in a large community sample (n = 1,443) of 13- to 18-year-old nonreferred German adolescents (774 boys and 669 girls; Essau et al. 2006), as well as an American sample (n = 248) of male and female juvenile offenders (188 boys, 60 girls) between the ages of 12 and 20 (Kimonis et al. 2008b; see also Fanti et al. 2009). Specifically, the total scale showed predicted associations with aggression, delinquency, personality traits (e.g., sensation seeking, Big Five dimensions), psychophysiology, and psychosocial impairment (Essau et al. 2006; Kimonis et al. 2008). Consistent with these past studies, items 2 and 10 from the ICU were deleted because of low corrected item-total correlations. The remaining 22 items were summed for a total score. Descriptive statistics and internal consistencies for all measures are reported in Table 1.

Exposure to Violence

Children’s self-reported exposure to violence was assessed using the Children’s Report of Exposure to Violence-Revised (CREV-R: Cooley et al. 1995). The CREV-R is a 33-item scale that assesses exposure to violence, including such situations as being robbed or mugged, stabbed, or killed. For the first 29 items, youth rate the frequency of their exposure to violence on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (every day). The CREV also includes four open-ended questions for youth to indicate whether they have ever been exposed to other types of violent acts not listed. The youth’s lifetime total exposure to violence score was used in the current study by summing all of the 29 rated items. Also, the ten-item witnessed violence scale (e.g., seeing a stranger beaten up) and the four-item violent victimization scales (e.g., being beaten up or shot) were computed for the present study. The CREV has demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.78) and 2-week test–retest reliability (r = 0.75), and has been used in research with high-risk African American youth between the ages of 9 and 15 (i.e., Cooley et al. 1995; Cooley-Quille et al. 2001).

In the current study the total exposure to violence score ranged from 13 to 92 with a mean of 46.64 (SD = 17.04), which is consistent with findings from a community sample of inner-city high school students (M = 52.03, SD = 16.21; Cooley-Quille et al. 2001). Mean scores across CREV items are reported in Table 1. The total CREV, witnessed violence and violent victimization scales demonstrated good internal consistency in the current detained sample (see Table 1).

Delinquency

Delinquency was measured using the Self-Reported Delinquency Scale (SRD; Elliott and Ageton 1980). The SRD scale assesses the number of crimes committed by the youth by listing 36 questions about illegal juvenile acts selected from a list of all offenses reported in the Uniform Crime Report with a juvenile base rate of greater than 1 % (Elliott and Huizinga 1984). For each question the youth is asked to respond with a “yes” or “no” regarding whether he has ever done the behavior. The current study used the 8-item violent offenses subscale (e.g., “have you ever been involved in gang fights?”), 7-item property offenses subscale (e.g. “have you ever purposely damaged or destroyed property belonging to school?”), and the 9-item drug offenses subscale (e.g. “have you ever sold hard drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and LSD?”). Given the small number of items included in the SRD assessing sexual delinquency (n = 2), a dichotomous variable was computed by coding an endorsement of either item or a history of sexual offending reported in the youth’s institutional file as present (“1”) and no such endorsement as not present (“0”). To account for this dichotomous variable in the models, we used weighted least-squares with mean and variance (WLSMV) estimation (Muthén et al. 1997). Internal consistencies for the continuous delinquency scales are reported in Table 1.

Results

Prior to addressing the study aims, the correlations among the main study variables were examined (see Table 1). CU traits were significantly positively correlated with total, direct, and witnessed violence exposure, as well as violent, property, and drug delinquency. CU traits were not significantly associated with sexual delinquency, thus not meeting the necessary preconditions for mediation (MacKinnon 2008). However, we retained this variable in the models tested, given its significant association with violence exposure. Specifically, there was a significant positive correlation between sexual delinquency and exposure to witnessed violence (r = 0.35, p < 0.05), but not direct victimization.

Primary Aims: Does Exposure to Violence Mediate the Associations Between CU Traits and Violent, Sexual and Drug—but not Property—Delinquency?

In the current study, we tested for mediation within a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework. Mediation is established when the following conditions are met: (a) the independent variable (X: CU traits) must relate significantly to the dependent variables (Y: delinquency types). To test this direct effect we fit a simple SEM model that specified CU traits (X) statistically predicting the dependent variables of interest (Y); (b) X must relate significantly to the mediator (violence exposure); (c) The mediator must relate significantly to Y when X is controlled; (d) The direct effect must become nonsignificant (full mediation) or reduced in significance (partial mediation) when the effect of the mediator is controlled (MacKinnon 2008).

All models were tested using Mplus 6 (Muthen and Muthen 2003). WLSMV estimation was used in all analyses as the models included the dichotomous sexual delinquency variable. The indirect paths between CU traits and delinquency types through exposure to violence (mediator) were tested using the MODEL INDIRECT/VIA commands in Mplus. We assessed quality of model fit using multiple indices, as each index has limitations (Kline 1998; MacCallum and Austin 2000) and there is no consensus criterion for evaluating model fit. Different aspects of fit were evaluated, including absolute fit (χ2) and fit relative to a null model (Comparative Fit Index, or CFI, and root mean square error of approximation, or RMSEA). Following convention, the criteria for good fit was defined as CFI > 0.95 and RMSEA < 0.06 and adequate fit was defined as CFI > 0.90 and RMSEA < 0.08 (Byrne 1994; Hu and Bentler 1995).

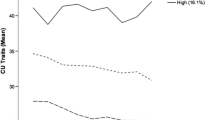

As depicted in Fig. 1, we fit a path model with CU traits (X) predicting property, drug, violent and sexual delinquency, with total exposure to violence specified as a mediator (χ 2 = 1.58, df = 2, n.s., CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00). Applying MacKinnon’s (2008) guidelines, we deleted all non-significant paths to create a more parsimonious model. There was support for full mediation of CU traits on violent delinquency by exposure to violence. Specifically, (a) there was a significant indirect effect between CU traits and violent delinquency through violence exposure (indirect, β = 0.16, p < 0.01) and (b) a reduction of the direct effect of CU traits on violent delinquency to nonsignificance (from β = 0.28, p < 0.05 in the first model to β = 0.12, p = 0.24 in the second model above). Additionally, there was support for partial mediation of CU traits on drug delinquency via violence exposure. Specifically, (a) there was a significant indirect effect between CU traits and drug delinquency through total violence exposure (indirect, β = 0.13, p < 0.05) and (b) a reduction of the direct effect of CU traits on drug delinquency to indicate decreased significance (from β = 0.35, p < 0.01 in the first model to β = 0.23, p < 0.05 in the second model above).

Second Exploratory Aim: Do Direct Victimization and Witnessed Exposure to Violence Mediate the Associations Between CU Traits and Types of Delinquency?

Our second aim focused specifically on exploring the relative contribution of types of violence exposure to mediating the CU-delinquency link. As seen in Fig. 2, we fit a path model with CU traits (X) predicting drug, violent, property, and sexual delinquency, with direct and witnessed exposure to violence specified as separate mediators (χ 2 = 13.02, df = 6, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.12). Again, we deleted all non-significant paths to create a more parsimonious model (MacKinnon 2008). We found support for full mediation of CU traits on violent delinquency by exposure to witnessed violence. Specifically, (a) there was a significant indirect effect between CU traits and violent delinquency through witnessed violence exposure (indirect, β = 0.11, p < 0.05) and (b) a reduction of the direct effect of CU traits on violent delinquency to nonsignificance (from β = 0.24 p < 0.05 in the first model to β = 0.07, p = 0.54 in the second model above).

Additionally, there was support for full mediation of CU traits on drug delinquency by exposure to both direct and witnessed violence. Specifically, (a) there was a significant indirect effect between CU traits and drug delinquency through direct violence exposure (indirect, β = 0.11, p < 0.05) and (b) a reduction of the direct effect of CU traits on drug delinquency to nonsignificance (from β = 0.33 p < 0.01 in the first model to β = 0.13, p = 0.24 in the second model above). Furthermore, (a) there was a significant indirect effect between CU traits and drug delinquency through witnessed violence exposure (indirect, β = 0.10, p < 0.05) and (b) a reduction of the direct effect of CU traits on drug delinquency to nonsignificance (from β = 0.33 p < 0.01 in the first model to β = 0.13, p = 0.24 in the second model above).Footnote 2

Discussion

The current study contributes several novel findings for improving our understanding of the effects of violence exposure on offending patterns in incarcerated boys high on CU traits. First, in line with our hypothesis, exposure to violence fully mediated the relationship between CU traits and violent delinquency. Moreover, this pattern of mediation was accounted for by exposure to witnessed violence, but not violent victimization. Second, exposure to violence, both direct and witnessed forms, also mediated the relationship between CU traits and drug delinquency. Third, exposure to witnessed violence—but not direct victimization—was associated with not only violent and drug delinquency, but also sexual delinquency. These findings are discussed in turn below.

Exposure to Violence Mediates the Link Between CU Traits and Violent Delinquency

In support of our hypothesis, the well-established link between CU traits and violence reported in several prior studies (e.g., Caputo et al. 1999; Frick and Dickens 2006; Frick and White 2008) was fully accounted for by a history of violence exposure in our sample of ethnically diverse detained boys. Furthermore, this pattern of mediation was driven by exposure to witnessed forms of violence. That is, boys who were high on CU traits tended to commit violent acts if they had witnessed violence around them. Witnessing violence perpetrated by others may lead youth to model such behavior through a social learning process (Bandura 1977; Widom 1989); however, victims of violence are likely to have a more personal understanding of its negative impact, potentially explaining our finding that direct victimization was not a significant mediator. Although it is certainly true that exposure to violence may be harmful whether or not CU traits are present, supported by our finding of an independent association between witnessed violence and violent delinquency, their presence is particularly relevant to this process because these youth may be at even greater risk for persistent violence given that they are also prone to deficits in empathy (Frick 2006; Frick et al. 2000), are less affected by the negative consequences of their aggressive behavior, such as the victim’s distress (Pardini et al. 2003), and are less emotionally engaged by or physiologically responsive to such cues (Blair 1999; Kimonis et al. 2006b; 2008a). Importantly, these dispositional differences are also used to argue for divergent developmental processes relative to antisocial youth scoring low on CU traits and likely explain the more severe and persistent violence that youth high on CU traits display (Frick et al. 2003a, b; 2005; Loney et al. 2007).

These findings are disconcerting given that youth high on CU traits report greater exposure to stressful life events, including witnessing violence done to others (Kimonis et al. 2008a). At least some researchers suggest that youth high on CU traits may be exposed to more stressful life events because they are more thrill and adventure seeking (Frick et al. 1999) or their impulsive tendencies place them in risky situations (Blonigen et al. 2011). Children high on CU traits, who are insensitive to punishment, also undermine parenting practices to evoke more harsh, inconsistent, and punitive discipline (Hawes et al. 2011), placing them at risk for witnessing and becoming victims of violence in the home. Similarly, a child who is emotionally unresponsive may lead the parent to disengage over time, resulting in reduced levels of parental warmth and rejection, or neglect at its extreme (Muñoz et al. 2011). Consistent with this notion, research documents an association between psychopathic traits and neglect (Weiler and Widom 1996). This transactional process can be particularly damaging given findings that CU traits and antisocial behavior increased 1 year later as reported parental warmth and involvement decreased (Pardini et al. 2003).

Exposure to Violence Mediates the Link Between CU Traits and Drug Delinquency

Our findings suggest that youth high on CU traits are more likely to engage in drug-related delinquency consistent with prior research (Wareham et al. 2009), and this association is fully attributable to their exposure to witnessed violence and direct victimization. Youth with CU traits tend to be highly reward-sensitive (Frick et al. 1999) and research suggests that this tendency is greatest among those who are secondary variants, theorized to be underpinned by an overactive behavioral activation system (Newman et al. 2005). Trauma exposure and anxiety are consistently linked with secondary psychopathy (Poythress and Skeem 2005) and the self-medication hypothesis, which has been used to explain the link between violence exposure and drug use, explains that the emotional sequelae of a traumatic event leads to subsequent substance use as a method of relieving painful symptoms or memories (Brown and Wolfe 1994; Khantzian 1985; Stewart 1996). This process may help explain drug abuse among those who are both directly exposed to aggression through physical abuse or neglect and those who witness severe violence in the family or community; thus, the association is strengthened among CU youth, who may be already susceptible to substance-related problems due to their heightened reward sensitivity.

Exposure to Violence is Associated with Sexual Delinquency

In the present study, we found a significant association between sexual delinquency and exposure to witnessed violence (r = 0.35, p < 0.05), but not direct victimization. This finding is consistent with prior research indicating that witnessing of severe domestic violence is related to juvenile sexual offending, as well as nonsexual violent offending (Caputo et al. 1999; Haapasalo and Hamalainen 1996; SpaccarelIi et al. 1997). Some authors suggest that youth exposed to violence, particularly domestic violence, come to develop a poor sense of interpersonal boundaries and attitudes supportive of violence, which places them at risk for sexually violent behavior (Spaccarelli et al. 1995). Our finding that CU traits were not associated with sexual delinquency contradicts prior research reporting greater sexual offending among youth high on CU traits, namely increased number of sexual offense victims and premeditated violent sexual behavior (Caputo et al. 1999; Lawing et al. 2010). However, it is important to consider that our dichotomous measure of sexual delinquency was a limitation to our study given that it was based on either the youth’s endorsement of engaging in sexual relations in exchange for payment or against an individual’s will, or on a past or current sexual offense in the youth’s institutional file.

In the process of interpreting our findings, some additional limitations beyond our measure of sexual delinquency must also be taken into consideration. First, the cross-sectional study design prevents any causal inferences regarding the study findings. In addition to examining whether exposure to violence mediates the relationship between CU traits and specific delinquency types, we also reversed the model to specify violence exposure as the IV and CU as the moderator (Caputo et al. 1999); however, mediation analyses were not significant. While it is possible that such effects may have been significant with a larger sample, results of a Monte Carlo simulation procedure suggested that our sample size maintained adequate power >0.84. Future rigorous longitudinal research is needed to gain clarity on the temporal ordering of these variables to better ascertain causality and resolve the important question of whether early stress and trauma (e.g., violence exposure) leads to the development of CU traits through a desensitization process as Porter (1996) and Karpman (1941) hypothesize, or whether youth high on CU traits elicit more stressors in their environments (Kimonis et al. 2008a), or both. Second, our measure of violence exposure did not allow us to differentiate between specific types of violence exposure beyond those that are directly experienced by the youth first-hand or witnessed acts of violence perpetrated by others. Future research may wish to explore the mediating effects of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse or neglect. We were also unable to distinguish between witnessing of domestic versus community violence, preventing any firm conclusions regarding the relevance of the proximity of witnessed violence to outcomes of interest. Further, we were unable to ascertain whether reported witnessed violence was perpetrated by the youth himself, leaving open the possibility of criterion contamination. Third, the current detained sample consisted primarily of African–American boys. Although this allowed us to examine the importance of violence exposure in the association between CU traits and types of delinquency in an understudied group at greater risk for violence exposure, it also limits the generalizability of our findings to other populations, such as community youth and girls. Lastly, future research is needed to confirm preliminary findings reported in the present study for witnessed violence and direct victimization, separately, given the exploratory nature of these results. It will be critical for future research to replicate these findings in independent samples to determine their robustness.

Despite these limitations, the results of the present study emphasize the importance of considering the environmental contexts of incarcerated youth high on CU traits. Youth characterized by a lack of remorse and empathy, uncaring behaviors, and an inability to express emotion are at greater risk for antisocial and aggressive behavior and our findings suggest that a history of violence exposure may be important for explaining this risk. Our findings suggest that if the home or neighborhood environments of youth with CU traits model violence these youth may channel their antisocial tendencies into violent or self-destructive acts. They may also choose to cope with their stressful life experiences by engaging in substance abuse, particularly when they have been the direct victims of a violent act. If their psychosocial histories are not marked with trauma, youth with CU traits may instead channel their antisocial tendencies into nonviolent acts of property delinquency, such as vandalism and theft. This was evidenced by the direct association between property delinquency and CU traits, but not violence exposure.

Overall, these results support the need for further research regarding contextual factors that contribute to the development of delinquent behavior among youth with CU traits, who are at risk for severe conduct problems. Theory and accumulating research suggest differing variants of psychopathic traits may exist with distinct causal factors and correlates—a primary variant theorized to have an innate inability to form affective bonds, and a secondary high-anxious variant associated with trauma exposure and maltreatment (Porter 1996). Although we were unable to directly test whether variants of callous-unemotional traits exist in the current sample, future research may expect the mediational processes reported to be most characteristic of secondary variants due to their greater experiences of maltreatment and other traumatic life events (Hicks et al. 2004; Tatar et al. 2012). Such research has important implications for improving developmental models that detail specific pathways leading to the development of conduct problems and delinquency in youth. These results also have important implications for identifying specific groups of youth that may be more susceptible to trauma exposure, and in turn, more at-risk for behaviors that harm the self and others. For example, low socioeconomic status is consistently documented as a correlate to violence exposure (Gerwirtz and Edleson 2007; Lee et al. 2004) and is found to predict a more stable course of conduct problems among youth with CU traits (Frick and Dantagnan 2005). Taking such factors into account may also assist in planning and tailoring treatment to the unique needs of CU youth who have different processes leading to their development of specific types of delinquency. Importantly, our results suggests that addressing trauma exposure among youth with CU traits may be critical in the prevention of violence, although it is also important that interventions are comprehensive and not focused solely on individual personality traits or psychosocial risk factors. Given the substantial rate of delinquent or violent behavior often displayed by youth with CU traits, the development of more comprehensive risk assessments and evidence-based interventions is crucial to violence and crime prevention efforts.

Notes

Although the primary aim was to examine the relationship between CU traits and delinquent outcomes, given prior literature suggesting that CU traits may develop as a consequence to violence exposure we also ran a reverse path model to test the possibility that CU traits mediated the association between violence exposure and delinquency. In this model we specified violence exposure as the IV and CU traits as the moderator. Results indicated mediation analyses were non-significant in this direction.

To differentiate the mediating effects of drug use relative to selling of drugs, we repeated the analysis removing SRD items tapping into selling drugs, thus limiting only to those items specifically involving drug use. Results held for full mediation of CU traits on drug use by direct victimization (indirect, β = 0.12, p < 0.05, Δ direct effect from β = 0.30 p < 0.05 in the first model to β = 0.10, p = 0.38 in the second), and were marginal for witnessing violence (indirect, β = 0.08, p = 0.07, Δ direct effect from β = 0.30 p < 0.05 in the first model to β = 0.10, p = 0.38 in the second).

To test whether the model was specific to CU traits and whether violence exposure accounts for the link between other types of antisocial/externalizing traits and violent delinquency, we re-ran a second mediation model substituting impulsivity for CU traits. Impulsivity was measured using the Antisocial Process Screening Device (Frick and Hare 2001). This alternative model did not reveal any significant effects. This suggests that violence exposure fully accounts for greater violent delinquency specifically among youth high on CU traits, who are at greater risk for antisocial outcomes due to weak moral development, but does not account for violent delinquency among youth with more general externalizing tendencies, namely disinhibition.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., & Handelsman, L. (1998). Predicting personality pathology among adult patients with substance use disorders: effects of childhood maltreatment. Addictive Behaviors, 6, 855–868.

Blackburn, R., & Coid, J. W. (1998). Psychopathy and the dimensions of personality disorder in violent offenders. Personality and Individual Differences, 25, 129–145.

Blair, R. J. R. (1999). Responsiveness to distress cues in the child with psychopathic tendencies. Personality and Individual Differences, 27, 135–145.

Blonigen, D. M., Sullivan, E. A., Hicks, B. M., & Patrick, C. J. (2011). Facets of PCLR psychopathy in relation to trauma exposure and PTSD symptomatology in an incarcerated sample of women: Mediation via borderline personality traits. In J. Blair (Chair), Society for the Study of Psychopathy 4th Biennial Meeting. Symposium conducted at the meeting of the Society for the Study of Psychopathy, Montreal, CA.

Breslau, N., Davis, G. C., & Schultz, L. R. (2003). Posttraumatic stress disorder and the incidence of nicotine, alcohol, and other drug disorders in persons who have experienced trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 289–294.

Brown, P. J., & Wolfe, J. (1994). Substance abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder comorbidity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 35, 51–59.

Byrne, B. (1994). Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Campbell, M. A., Porter, S., & Santor, D. (2004). Psychopathic traits in adolescent offenders: an evaluation of criminal history, clinical, and psychosocial correlates. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 22, 23–47.

Caputo, A. A., Frick, P. J., & Brodsky, S. L. (1999). Family violence and juvenile sex offending: the potential mediating role of psychopathic traits and negative attitudes toward women. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 26, 338–356.

Christian, R. E., Frick, P. J., Hill, N. L., Tyler, L., & Frazer, D. R. (1997). Psychopathy and conduct problems in children: II. Implications for subtyping children with conduct problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(2), 233–241.

Cooley, M. R., Turner, S. M., & Beidel, D. C. (1995). The emotional impact of children’s exposure to community violence: a preliminary study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34, 1362–1368.

Cooley-Quille, M., Boyd, R. C., Frantz, E., & Walsh, J. (2001). Emotional and behavioral impact of exposure to community violence in inner-city adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(1), 199–206.

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, L. M. (1997). Peabody Picture Vocabulary

Elliott, D. S., & Ageton, S. (1980). Reconciling ethnicity and class differences in self-reported and official estimates of delinquency. American Sociological Review, 45(1), 95–110.

Elliott, D. S., & Huizinga, D. (1984). The relationship between delinquent behavior and ADM problems. Boulder: Behavioral Research Institute.

Essau, C. A., Sasagawa, S., & Frick, P. J. (2006). Callous-unemotional traits in a community sample of adolescents. Assessment, 13, 454–469.

Fanti, K. A., Frick, P. J., & Georgiou, S. (2009). Linking callous-unemotional traits to instrumental and non-instrumental forms of aggression. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31, 285–298.

Farrell, A. D., & Bruce, S. E. (1997). Impact of exposure to community violence on violent behavior and emotional distress among urban adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 26(1), 2–14.

Fitzpatrick, K. M. (1993). Exposure to violence and presence of depression among low-income African American youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 528–531.

Ford, M. E., & Linney, J. A. (1995). Comparative analysis of juvenile sexual offenders, violent nonsexual offenders, and status offenders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 10, 56–70.

Frick, P. J. (2004). The Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits. Unpublished rating scale.

Frick, P. J. (2006). Developmental pathways to conduct disorder. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 15(2), 311–331.

Frick, P. J. (2009). Extending the construct of psychopathy to youths: implications for understanding, diagnosing, and treating antisocial children and adolescents. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 12, 803–812.

Frick, P. J., & Dantagnan, A. L. (2005). Predicting the stability of conduct problems in children with and without callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14(4), 469–485.

Frick, P. J., & Dickens, C. (2006). Current perspectives on conduct disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 8, 59–72.

Frick, P.J., & Hare, R.D. (2001). The antisocial process screening device. Toronto:Multi-Health Systems.

Frick, P. J., & White, S. F. (2008). The importance of callous-unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 359–375.

Frick, P. J., Lilienfeld, S. O., Ellis, M., Loney, B., & Silverthorn, P. (1999). The association between anxiety and psychopathic traits dimensions in children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27(5), 383–392.

Frick, P. J., Bodin, S. D., & Barry, C. T. (2000). Psychopathic traits and conduct problems in community and clinic-referred samples of children: further development of the Psychopathic traits Screening Device. Psychological Assessment, 12, 382–393.

Frick, P. J., Cornell, A. H., Barry, C. T., Bodin, S. D., & Dane, H. E. (2003a). Callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems in the prediction of conduct problem severity, aggression, and self-report of delinquency. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(4), 457–470.

Frick, P. J., Kimonis, E. R., Dandreaux, D. M., & Farrell, J. M. (2003b). The 4 year stability of psychopathic traits in non-referred youth. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 21(6), 713–736.

Frick, P. J., Stickle, T. R., Dandreaux, D. M., Farrell, J. M., & Kimonis, E. R. (2005). Callous-unemotional traits in predicting the severity and stability of conduct problems and delinquency. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(4), 471–487.

Gerwirtz, A. H., & Edleson, J. L. (2007). Young children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: towards a developmental risk and resilience framework for research and intervention. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 151–163.

Haapasalo, J., & Hamalainen, T. (1996). Childhood family problems and current psychiatric problems among young violent and property offenders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34, 1394–1401.

Hawes, D. J., Dadds, M. R., Frost, A. D. J., & Hasking, P. A. (2011). Do childhood callous-unemotional traits drive change in parenting choices? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40(4), 507–518.

Hicks, B. M., Markon, K., Patrick, C. J., Krueger, R., & Newman, J. P. (2004). Identifying psychopathy subtypes on the basis of personality structure. Psychological Assessment, 16, 276–288.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. (1995). Evaluating model fit. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling. Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 76–99). London: Sage.

Jang, K.L., Stein, M.B., Taylor, S., Asmundson, G.J., & Livesley, W.J. (2003). Exposure to traumatic events and experiences: aetiological relationships with personality function. Psychiatry Research, 120(1), 61–69.

Karpman, B. (1941). On the need for separating psychopathy into two distinct clinical types: symptomatic and idiopathic. Journal of Clinical Psychopathology, 3, 112–137.

Khantzian, E. J. (1985). The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 142, 1259–1264.

Kimonis, E. R., Frick, P. J., Boris, N. W., Smyke, A. T., Cornell, A. H., Farrell, J. M., et al. (2006a). Callous-unemotional features, behavioral inhibition, and parenting: independent predictors of aggression in a high-risk preschool sample. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15(6), 745–756.

Kimonis, E. R., Frick, P. J., Fazekas, H., & Loney, B. R. (2006b). Psychopathic traits, aggression, and the processing of emotional stimuli in non-referred children. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 24, 21–37.

Kimonis, E. R., Frick, P. J., Munoz, L. C., & Aucoin, K. J. (2008a). Callous-unemotional traits and the emotional processing of distress cues in detained boys: testing the moderating role of aggression, exposure to community violence, and histories of abuse. Development and Psychopathology, 20, 569–589.

Kimonis, E. R., Frick, P. J., Skeem, J. L., Marsee, M. A., Cruise, K., Muñoz, L. C., Aucoin, K. J., & Morris, A. S. (2008b). Assessing callous-unemotional traits in adolescent offenders: Validation of the inventory of callous-unemotional traits. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. Special Issue: Psychopathy and risk assessment in children and adolescents, 31(3), 241–252. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.04.002.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Krischer, M. K., & Sevecke, K. (2008). Early traumatization and psychopathy in female and male juvenile offenders. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 31(3), 253–262.

Larson, H., Andershed, H., & Lichtenstein, P. (2006). A genetic factor explains most of the variation in the psychopathic personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115, 221–230.

Lawing, K., Frick, P. J., & Cruise, K. R. (2010). Differences in offending patterns between adolescent sex offenders high or low in callous-unemotional traits. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 298–305.

Lee, L. C., Kotch, J. B., & Cox, C. E. (2004). Child maltreatment in families experiencing domestic violence. Violence and Victims, 19(5), 573–591.

Loney, B. R., Taylor, J., Butler, M. A., & Iacono, W. G. (2007). Adolescent psychopathy features: 6-year temporal stability and the prediction of externalizing symptoms during the transition to adulthood. Aggressive Behavior, 33, 242–252.

Lykken, D. T. (1995). The antisocial personalities. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Lynam, D. R., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Loeber, R., & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (2007). Longitudinal evidence that psychopathy scores in early adolescence predict adult psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 155–165.

Lynam, D. R., Miller, D. J., Vachon, D., Loeber, R., & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (2009). Psychopathy in adolescence predicts official reports of offending in adulthood. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 7(3), 189–207.

MacCallum, R. C., & Austin, J. T. (2000). Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 201–226.

MacKinnon, D. (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah: Erlbaum Psychological Press.

Main, M., & George, C. (1985). Responses of abused and disadvantaged toddlers to distress in agemates: a study in the day-care setting. Developmental Psychology, 21, 407–412.

Mrug, S., & Windle, M. (2009). Initiation of alcohol use in early adolescence: links with exposure to community violence across time. Addictive Behaviors, 34(9), 779–781.

Muñoz, L. C., & Frick, P. J. (2007). The reliability, stability, and predictive utility of the self-report version of the antisocial process screening device. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 48(4), 299–312.

Muñoz, L. C., Pakalniskiene, V., & Frick, P. J. (2011). Parental monitoring and youth behavior problems: moderation by callous-unemotional traits over time. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 20, 261–269. doi:10.1007/s00787-011-0172-6.

Muthen, B. O., & Muthen, L. K. (2003). MPlus Version 5.1.

Muthén, B., du Toit, S. H. C., & Spisic, D. (1997). Robust inference using weighted least squares and quadratic estimating equations in latent variable modeling with categorical and continuous outcomes.<http://gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/muthen/articles/Article_075.pdf> Accepted for publication in Psychometrika. Found on http://gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/muthen/psychometrics.htm.

Newman, J. P., MacCoon, D. G., Vaughn, L. J., & Sadeh, N. (2005). Validating a distinction between primary and secondary psychopathy with measures of Gray’s BIS and BAS constructs. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 319–323.

Pardini, D. A., Lochman, J. E., & Frick, P. J. (2003). Callous-unemotional traits and social-cognitive processes in adjudicated youths. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(3), 364–371.

Piazza, P. V., & Le Moal, M. L. (1996). Pathophysiological basis of vulnerability to drug abuse: role of an interaction between stress, glucocorticoids, and dopaminergic neurons. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 36, 359–378.

Porter, S. (1996). Without conscience or without active conscience? The etiology of psychopathy revisited. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 1(2), 179–189.

Poythress, N. G., & Skeem, J. L. (2005). Disaggregating psychopathy: Where and how to look for variants. In C. J. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of psychopathy (pp. 172–192). New York: Guilford Press.

Righthand, S., & Welch, C. (2001). Juveniles who have sexually offended: A review of the professional literature. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 3-4.

Simpson, T. L. (2002). Women’s treatment utilization and its relationship to childhood sexual abuse history and lifetime PTSD. Substance Abuse, 23, 17–30.

Simpson, T. L., & Miller, W. R. (2002). Concomittance between childhood sexual and physical abuse and substance use problems. A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 22, 27–77.

Skeem, J., Johansson, P., Andershed, H., Kerr, M., & Louden, J. E. (2007). Two subtypes of psychopathic violent offenders that parallel primary and secondary variants. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(2), 395–409.

Smith, S. S., & Newman, J. P. (1990). Drug abuse-dependence disorders in psychopathic and nonpsychopathic criminal offenders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99(4), 430–439.

SpaccarelIi, S., Bowden, B., Coatsworth, J. D., & Kim, S. (1997). Psychosocial correlates of male sexual aggression in a chronic delinquent sample. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 24, 71–95.

Spaccarelli, S., Coatsworth, J. D., & Bowden, B. S. (1995). Exposure to serious family violence among incarcerated boys: its association with violent offending and potential mediating variables. Violence and Victims, 10(3), 163–182.

Stewart, S. H. (1996). Alcohol abuse in individuals exposed to trauma: a critical review. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 83–112.

Tatar, J. R., Cauffman, E., Kimonis, E. R., & Skeem, J. L. (2012). Victimization history and post-traumatic stress: an analysis of psychopathy variants in male juvenile offenders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 5, 102–113. doi:10.1080/19361521.2012.671794.

Taylor, J., & Lang, A. R. (2005). Psychopathy and substance use disorders. In C. J. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of psychopathy (pp. 495–511). New York: Guilford Press.

Taylor, J., Loney, B. R., Babadilla, L., Iacono, W. G., & McGue, M. (2003). Genetic and environmental influences on psychopathy trait dimensions in a community sample of male twins. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(6), 633–645.

Thompson, R., & Wiley, T. R. (2009). Predictors of re-referral to child protective services: a longitudinal follow-up of an urban cohort maltreated as infants. Child Maltreatment, 14(1), 89–99.

Vassileva, J., Kosson, D. S., Abramowitz, C., & Conrod, P. (2005). Psychopathy versus psychopathies in classifying criminal offenders. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 10, 1–18.

Viding, E., Jones, A. P., Paul, J. F., Moffitt, T. E., & Plomin, R. (2008). Heritability of antisocial behavior at 9: do callous-unemotional traits matter? Developmental Science, 11, 17–22.

Volkow, N. D., & Fowler, J. S. (2000). Addiction, a disease of compulsion and drive: involvement of the orbitofrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex, 10, 318–325.

Wareham, J., Dembo, R., Poythress, N. G., Childs, K., & Schmeidler, J. (2009). A latent class factor approach to identifying subtypes of juvenile diversion youths based on psychopathic features. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 27(1), 71–95.

Weiler, B. L., & Widom, C. S. (1996). Psychopathy and violent behaviour in abused and neglected young adults. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 6(3), 253–271.

Widom, C. S. (1989). Child abuse, neglect, and adult behavior: research design and findings on criminality, violence, and child abuse. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 59(3), 355–367.

Willoughby, M. T., Waschbusch, D., Moore, G. A., & Propper, C. B. (2011). Using the ASEBA to screen for callous-unemotional traits in early childhood factor structure, temporal stability, and utility. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 33(1), 19–30. doi:10.1007/s10862-010-9195-4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Howard, A.L., Kimonis, E.R., Muñoz, L.C. et al. Violence Exposure Mediates the Relation Between Callous-Unemotional Traits and Offending Patterns in Adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol 40, 1237–1247 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9647-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9647-2