Abstract

We report findings from a pilot intervention that trained parents to be “friendship coaches” for their children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Parents of 62 children with ADHD (ages 6–10; 68% male) were randomly assigned to receive the parental friendship coaching (PFC) intervention, or to be in a no-treatment control group. Families of 62 children without ADHD were included as normative comparisons. PFC was administered in eight, 90-minute sessions to parents; there was no child treatment component. Parents were taught to arrange a social context in which their children were optimally likely to develop good peer relationships. Receipt of PFC predicted improvements in children’s social skills and friendship quality on playdates as reported by parents, and peer acceptance and rejection as reported by teachers unaware of treatment status. PFC also predicted increases in observed parental facilitation and corrective feedback, and reductions in criticism during the child’s peer interaction, which mediated the improvements in children’s peer relationships. However, no effects for PFC were found on the number of playdates hosted or on teacher report of child social skills. Findings lend initial support to a treatment model that targets parental behaviors to address children’s peer problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The social impairment faced by children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is difficult to overstate. These youth are frequently peer rejected, and often have few or no friends (Hoza et al. 2005b). Furthermore, the presence of peer difficulties may predict children’s subsequent risk for poor adolescent and adult adjustment (Mikami and Hinshaw 2006).

Despite the public health significance of reducing peer problems, the field has made only circumscribed progress towards developing interventions that achieve this goal (Mrug et al. 2001). Stimulant medication and behavioral therapy are well-validated for the core symptoms of ADHD (MTA Cooperative Group 1999a), yet their efficacy for improving peer relationships is modest. Children may reduce aggressive and intrusive behaviors as a result of treatment, however, improvements in peers’ liking do not always follow. In the Multimodal Treatment of Children with ADHD Study (MTA Cooperative Group 1999a), both intensive medication and behavioral management failed to increase peer reports of acceptance or friendship at the conclusion of the 14-month active treatment period (though treatments produced gains in adult informant-reported social skills). As noted by the authors, it is remarkable that even after receiving state-of-the art treatments delivered under ideal conditions, children with ADHD remained profoundly impaired in their peer functioning (Hoza et al. 2005a).

Social skills training is also widely-used among youth with ADHD, however efficacy is variable and fewer than half of programs may produce gains in peer relationships (Beelman et al. 1994; Quinn et al. 1999). In a study of 103 children with ADHD, Abikoff et al. (2004) found no added benefit of receiving social skills training plus medication over medication alone on adult ratings or observations of peer relationships, either at the end of a 1 year intensive treatment period or a 2 year follow-up where treatment was provided less frequently. Although this study lacks a comparison group of untreated youth, other work has tested short-term social skills training relative to no treatment and failed to find effects (Antshel and Remer 2003). Based on these findings, multiple investigators propose that social skills training may not be useful for youth with ADHD (Barkley 2004; de Boo and Prins 2007; Mrug et al. 2001; Pelham et al. 1998).

Parental Influences on the Peer Relationships of Children with ADHD

Treatments for the social impairment of children with ADHD have primarily focused on reducing problem behaviors enacted by the child with ADHD, while the influence of parents on their children’s peer relationships has been a less frequent intervention target. Yet, parents may create social contexts for their children that facilitate acceptance and friendship by networking with other families and by structuring good interactions on playdates between their children and peers (Parke et al. 1994). Parents may also directly instruct their children in friendship-making behaviors in vivo during their children’s peer interactions, or by modeling of their own behaviors (Parke et al. 1994). Please see (Mikami, Jack, Emeh, and Stephens, this issue) for a review of ways in which parents influence their children’s peer relationships.

In (Mikami, Jack, Emeh, and Stephens, this issue) we reported findings that parents of children with ADHD, relative to parents of age- and sex-matched comparison children, had lower social skills of their own and arranged fewer playdates for their children. They were also observed to be more critical of their child after a peer interaction, after statistical control of a host of covariates including the child’s observed aggressive behavior during the interaction. We posited that parents of children with ADHD may struggle, relative to parents of comparison children, to create positive social opportunities for their children and to coach their children in social skills in a manner that is likely to lead to children’s receptivity. We also found that parents’ own social skills, socialization with other parents, and facilitation of the child’s peer interactions predicted their children having good peer relationships, but parental criticism, corrective feedback, and praise predicted their child having poorer relationships. Intriguingly, the positive correlations between the parental behaviors of hosting playdates, socializing, and warmth, with children’s good peer relationships, were stronger for youth with ADHD than comparison youth (Mikami, Jack, Emeh, and Stephens, this issue).

Parents as Friendship Coaches for Children with ADHD

The development of parent-focused treatments for children’s peer problems has promise. Hoza et al. (2003) paired children with ADHD together as “buddies”. One component of the treatment was encouraging the parents of each child to foster the relationship. Results suggested that if parents set up playdates with their child’s assigned buddy, the child and buddy developed a closer relationship. However, this study lacked a control group not receiving the intervention.

Frankel and colleagues have developed an innovative program where children receive group-based social skills training while parents attend concurrent sessions where they are informed about the content being taught to their children and instructed to reinforce these skills at home (Frankel et al. 1997). Results suggest efficacy on improving adult-informant ratings of social behavior for children with ADHD (Frankel et al. 1997). Other investigators have similarly included concurrent parent groups in life skills interventions for children with ADHD, some focus of which is on the child’s behavior with peers (Pfiffner and McBurnett 1997; Pfiffner et al. 2007). Collectively, findings suggest that generalization may be strengthened by having parents actively involved in the treatment that the child is receiving.

Although efforts in this area have been encouraging, we propose that these existing interventions may not go far enough in conceptualizing the parent as the primary agent of change. Predominantly, they use parent involvement to reinforce the child for outside-of-session displays of the skills learned in therapy, but do not include other ways in which parents may assist their children to develop good peer relationships, such as having the parent: (a) network with other parents who have similar-age children; (b) facilitate the child’s peer interactions on playdates; and (c) instruct the child in social skills didactically or via modeling. The intervention of Frankel and colleagues (1997) is an exception, because it does teach parents to arrange playdates for their children and to manage conflict and disengagement during playdates. Yet the program design, in which parent involvement is added to child social skills training, does not allow determination of whether an exclusive focus on training parents in these behaviors without a child treatment component would be effective.

Treatment Moderators

Sex, comorbid Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), and medication use are important potential moderators of psychosocial treatments for peer problems. Available evidence suggests equal effectiveness of treatment on boys versus girls with ADHD (e.g., MTA Cooperative Group 1999b), but the high male predominance in most samples may have limited investigations (Mikami and Hinshaw 2008). The evidence for ODD as a treatment moderator has been mixed, with Frankel and colleagues reporting enhanced effectiveness of their parent-involved treatment for children without ODD in some work (Frankel et al. 1995), but equal effectiveness in others (Frankel et al. 1997). Finally, Frankel et al. (1997) suggest that medicated children with ADHD may benefit more from their program relative to unmedicated youth, although the provision of psychosocial treatment to youth already receiving medication has not resulted in improvements in other work (Abikoff et al. 2004; MTA Cooperative Group 1999a).

Study Hypotheses

We developed a novel intervention for parents of children with ADHD, Parental Friendship Coaching (PFC), in which parents are taught to create social opportunities for their children that encourage peer relationships and to instruct their children in social skills. Because of the emphasis on parents as the source of the intervention effect, there was no child treatment component. We assessed the effectiveness of PFC using a small randomized clinical trial.

Our primary hypothesis was that children whose parents had received PFC would display improvement in peer relationships relative to youth whose parents had not received PFC. Second, we hypothesized that receipt of PFC would predict improvement in the parental behaviors of playdates arranged, socializing with other parents, facilitation of the child’s peer interactions, corrective feedback, praise, warmth, and criticism. In line with the treatment model that PFC would improve children’s peer relationships through the mechanism of teaching parents to assist their children, we hypothesized that changes in parental behaviors would mediate the effect of PFC on the child’s functioning. Finally, we conducted exploratory analyses testing the moderating effects of child sex, ODD, and medication status on the effectiveness of PFC.

Method

Participants

Participants were families of 62 children (42 boys; ages 6–10) with ADHD, and a comparison sample of 62 age- and sex- matched children without ADHD. Children were 85% white, 5% African American, 2% Asian American, 1% Latino, and 7% were more than one race. Each child participated with one parent (94% female), who was the legal guardian, the parent “most involved in the child’s social life,” and with whom the child resided at least half of the time. Participants were recruited from clinics, schools, pediatricians, and from a database of families who had previously participated in research at the university. Parents provided written informed consent and children provided assent.

Children with ADHD exceeded clinical cutoffs on parent and teacher ratings on the Child Symptom Inventory (CSI; Gadow and Sprafkin 1994), and diagnosis was verified in a clinical interview with the parent (K-SADS; Kaufman et al. 1997). The majority of the children with ADHD were Combined Type (ADHD-C; n = 46), and the remainder Inattentive Type (ADHD-I; n = 16). Comparison youth could not meet criteria for ADHD on parent or teacher CSI, and could not receive a diagnosis of ADHD on the K-SADS. For the ADHD sample, mean T-scores on the Conners’ ADHD Symptom Index (Conners 2001) were 69.92 (SD = 13.21) for parent ratings and 65.37 (SD = 11.80) for teacher ratings. For the comparison sample, these same means were 44.29 (SD = 3.96) for parent ratings and 45.15 (SD = 4.95) for teacher ratings. Exclusion criteria for both ADHD and comparison groups were pervasive developmental disorders, Full Scale IQ below 70, or Verbal IQ below 75. Anxiety and depressive disorders, ODD, and conduct disorder (CD) were permitted in both groups, although no child met criteria for CD.

Children on medication (n = 40 ADHD, no comparison) had been receiving the same type and dosage of medication for at least 3 months before the start of the study and continued their same medication regimen throughout the treatment and follow-up assessments. Children could not be receiving other psychosocial treatment for social or behavioral issues. However, children receiving academic interventions were allowed, provided that these interventions had been occurring for at least 3 months before the start of the study and that the parent intended to continue these interventions throughout the study period. There were no significant differences between ADHD and comparison groups in most demographic variables, but comparison youth had higher parental education levels, t(122) = 3.53; p < 0.01. As expected, comparison youth had higher IQ scores, t(122) = 4.11; p < 0.01, and lower externalizing behaviors as rated by both parents, t(122) = 10.64; p < 0.01, and teachers, t(120) = 10.29 p < 0.01, on the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach 1991a, b) relative to youth with ADHD (Table 1). These differences parallel those found in other large samples in both direction and magnitude (Barkley 2006).

Procedure

Baseline Assessment

Once children had met inclusion criteria, parents and teachers completed additional questionnaires about children’s functioning. Children were then assigned to playgroups. Each playgroup consisted of four children (two children with ADHD and two comparison children) the same age and sex, and previously unacquainted with each other; similar size playgroups have been suggested to provide valid assessments of behavior (Hodgens et al. 2000). Each child’s parent who had completed the questionnaires was also present. The purpose of the playgroups was to assess parental behaviors during children’s peer interactions in a controlled environment free from previously-established reputations. We considered the alternative of observing home-based playdates with existing friends, which might have improved external validity, but were concerned that many children would not have any friends with whom this procedure could be conducted.

The playgroup was held for 1 h. Children participated in a structured activity and in unstructured free play. Parents were given the instruction to do what they thought would help their child make friends and get along with the other peers, but parents were provided with no direction regarding what behaviors to do, and parents had the choice of engaging with their child, socializing with other adults, or reading news magazines provided. At the conclusion of the playgroup, each parent-child dyad spent 4 min in a private room. Parents were asked to give their child feedback about his/her behaviors in the playgroup in such a way as to help their child to make friends and to get along with the other children. A sociometric procedure was administered (Coie et al. 1982) at the end of the playgroup.Footnote 1 Families were asked to not arrange outside contact with other playgroup members until the study concluded. See (Mikami, Jack, Emeh, and Stephens, this issue).

Randomization

After baseline assessments, parents of children with ADHD were randomly assigned to receive PFC, a novel treatment teaching them to be “friendship coaches” for their children, or to be in a no-treatment control group. Six cohorts were randomized, each cohort containing five to six playgroups. In every playgroup, one parent of a child with ADHD was randomized to receive PFC, the parent of the other child with ADHD was randomized to the no-treatment control group, and the parents of the two comparison children did not receive treatment. This resulted in one PFC group per cohort, with five or six parents in that group.

There was one exception to this procedure; in one cohort, one extra parent of a child with ADHD, chosen randomly, was assigned to treatment. Therefore (other than this one case), assignment to PFC and control groups was stratified by child sex and age. There were no demographic differences between ADHD-PFC and ADHD-control groups (see Table 1).

Midpoint

PFC was delivered for 8 weeks. At the midpoint of treatment, the same children and parents who had been in a playgroup together at baseline returned for a second playgroup, where the identical procedure was repeated.

Post-test

At the immediate conclusion of PFC, a final playgroup occurred. Parents and teachers also repeated questionnaire measures of child social functioning. Although parents were obviously aware of whether or not they had received PFC, study personnel kept teachers unaware of the family’s treatment status and asked parents to not give teachers this information.

Follow-up

One month after the study ended, parents were contacted by phone and interviewed regarding changes in their child’s peer relationships.

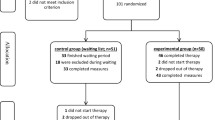

Please see Fig. 1 for a flowchart of study procedures. Some families dropped out of the PFC treatment (see Results). However, we attempted to collect midpoint, post-test, and follow-up data from all families including PFC dropouts and encouraged this by continuing to pay families for providing data at each assessment point.

Parental Friendship Coaching (PFC) Intervention

PFC consisted of eight 90-min group sessions, delivered once-weekly, involving five to six parents and led by two clinicians. The parent who completed the questionnaires and attended the playgroups was requested to attend PFC, but co-parents were allowed to join if desired. Sessions were manualized, although minor changes to content occurred based on parent feedback. Each PFC session began with a review of homework from the previous week. Then, the target parental coaching strategies of the week (see Table 2) were explained using handouts, activities, and role plays. Parents were encouraged to bring up ways in which strategies could be tailored to their child’s specific needs. Group viewing of videotapes of each parent’s interaction with his/her child during the playgroups was used as a teaching tool. To assess treatment fidelity, independent raters not involved in the therapy observed videotapes of all sessions and assessed content covered relative to the manual. Coverage of topics was 100%, although in a few cases material from a session was presented in the next because of insufficient time.

Parents completed consumer satisfaction ratings at the end of the treatment. For cohorts 3–6 only, parents completed additional ratings at the end of each session regarding whether they had completed the assigned homework the previous week, and the extent they found that week’s session helpful. Lastly, study personnel recorded parent attendance at sessions. When parents were unable to attend group, efforts were made to provide individualized make-up sessions.

Primary Outcomes: Child Peer Relationship Measures

All measures are described in greater detail in (Mikami, Jack, Emeh, and Stephens, this issue).

Social Skills Rating System (SSRS; Gresham and Elliott 1990)

Parents and teachers independently completed this well-normed scale. The parent form has 55 items and the teacher form has 57 items, each rated on a three-point metric (never, sometimes, or very often). We considered the child’s total social skills standard score, based on age and sex norms.

Dishion Social Acceptance Scale (DSAS; Dishion 1990)

Teachers reported the percentage of classmates who “like and accept” and “dislike and reject” the child, using a five-point scale: 1 (almost none, less than 25%); 2 (a few, 25–50%); 3 (about half, 50%); 4 (most, 50–75%); 5 (nearly all, over 75%). Moderate correlations have been found between this measure and peer sociometrics obtained in the classroom (Dishion 1990; Dishion and Kavanagh 2003).

Quality of Play Questionnaire (QPQ; Frankel 2003)

Because of the emphasis in PFC on teaching parents to structure their child’s playdates such that the child and peer get along, we included a parent-report measure regarding the quality of the child’s interaction with the peer on a playdate. Parents were instructed to think about the most recent playdate their child had, and to list the initials of the peer to aid recall. Parents answered 18 questions on a four-point scale from 0 to 3 (not at all, just a little, pretty much, and very much) as to how the child and the peer interacted during the visit (sample item: “They argued with each other”). Based on the loadings determined by Frankel (2003), two subscales were computed: Conflict and Disengagement.

Child Friendships at Follow-up

Parents reported the extent to which their child’s friendships had changed in the month since the end of the study period and since the post-test questionnaires had been completed. Parents reported globally on a five-point scale: 1= very much worse; 2= worse; 3=same; 4=better; 5=very much better.

Secondary Outcomes and Potential Mediators of Child Improvement: Parental Behaviors

Parental Behavior in Playgroup

Observers unaware of families’ diagnostic or treatment status viewed videotapes of the playgroup and coded parents’ behavior. Twenty-five percent of the videos were selected at random to be double coded, and intra-class correlations (ICCs) were calculated between the two raters. In addition, we also report the percentage of occurrence-only agreement within one step. Socializing was coded on a scale from 0 (socialized 0% of the time) to 10 (socialized 100% of the time). Facilitation and corrective feedback were rated on global Likert scales from 0 (absence) to 3 (more than one major instance or one major and at least one minor instance), that capture frequency and intensity of the behavior. More detailed descriptions may be found in (Mikami, Jack, Emeh, and Stephens, this issue). Codes were as follows:

-

(a)

Socializing. The parent converses with other parents in the playgroup. ICC = 0.96; occurrence only agreement within one step =87%.

-

(b)

Facilitation. The parent assists the child with skillfully engaging in activities with the other children, such as helping to reduce conflict or disengagement. ICC = 0.83; occurrence only agreement within one step = 88%.

-

(c)

Corrective feedback. The parent gives the child an instruction to change something about his/her behavior, or an explicit reminder to behave in a certain manner. ICC = 0.74; occurrence only agreement within one step = 85%.

Parental Behavior in Parent-child Interaction

Similarly, observers coded the parent-child interactions that occurred after the playgroup. All parent-child interaction codes were rated on the same Likert scale from 0 to 3 as were facilitation and corrective feedback.

-

(a)

Praise. The parent gives the child praise about the child’s actions, related to the playgroup that had just occurred. Comments must be framed positively, sound genuine, and be specifically directed at the child. ICC = 0.79; occurrence only agreement within one step = 90%.

-

(b)

Warmth. The parent projects love and seems to be genuinely happy to be in the child’s presence. The parent might display laughter, matched affect with the child, good-natured humor, and/or physical affection. ICC = 0.72; occurrence only agreement within one step = 100%.

-

(c)

Criticism. The parent makes a negative statement about the child’s actions or character, using a tone of exasperation, irritation, hostility, or contempt. ICC = 0.83; occurrence only agreement within one step = 93%.

Playdates Hosted

In this procedure, used by Frankel (2003), parents reported the number of playdates in which a friend came to play with their child during the past month.

Covariates

Demographics

Family income, parental education, child sex, and child receipt of psychotropic medication were reported by parents on a questionnaire.

Full Scale IQ

This was estimated from six subtests on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 4th edition (WISC-IV; Wechsler 2003).

ODD

This was considered present if parents endorsed this disorder on the KSADS, and teachers reported elevated (T-score >60) symptoms on the Connors’ Oppositional Behavior Index.

Observed Child Aggression in Playgroup

This was defined as instances of verbal or physical aggression expressed by the child, coded on the same 0–3 Likert metric as were the playgroup parental behaviors. ICC = 0.66; occurrence only agreement within one step = 85%.

Data Analytic Plan

Our primary hypothesis was that PFC would improve children’s peer relationships. We used an intent-to-treat design and included all participants (ADHD-PFC, ADHD-control, comparison). To examine treatment effects on the parent and teacher questionnaires (SSRS, DSAS, QPQ), we conducted ANCOVAs using full information maximum likelihood. Dependent variables were the questionnaire measures of child functioning at post-test. In order to assess the child’s level of change on that questionnaire during the study period, we covaried baseline functioning on that same questionnaire. The independent variable was whether PFC was received. In addition, we covaried child ADHD status, child IQ, income, and education because these constructs distinguished ADHD and comparison groups; and we covaried ODD, sex, and medication because of the rationale that they may moderate treatment effects.

If the effect of PFC was significant and associated with improvements in parent and teacher social skills (SSRS) and teacher report of peers who “like and accept” the child (DSAS), and associated with declines in teacher report of peers who “dislike and reject” the child (DSAS) and parent report of conflict and disengagement on playdates (QPQ), this hypothesis would be confirmed. We then tested the hypothesis that parents who had received PFC would report improvement in the follow-up period relative to parents who did not receive PFC. An ANCOVA was conducted comparing PFC and control groups with the same covariates listed above, except with no equivalent baseline measure in this case, because the question administered to parents at follow-up had not been given previous to this timepoint. Finally, normalization was considered.

Because of our treatment model, in which we intervened with the parents only to yield changes in child functioning, we thought it would be important to examine PFC-related effects on parental friendship coaching behaviors and test the potential for changes in these parental behaviors to mediate the child’s improvement. Similar to the way in which we assessed treatment effects on child functioning, we used ANCOVAs to predict the dependent variable of parental report of playdates hosted on post-test questionnaires, while controlling for playdates at baseline. However, in order to examine PFC-related changes in observed parental behaviors that occurred in the lab-based playgroup, we used Hierarchical Linear Modeling analyses (HLM; Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). HLM was necessary for these dependent variables for two reasons. First, the structure of the data is such that families were nested in playgroups, and parents’ behaviors may be influenced by the actions of the other parents in their playgroup (see Mikami, Jack, Emeh, and Stephens, this issue for further details). Therefore, in order to test the impact of PFC on parental behaviors in the playgroup, we used HLM to account for shared variance at the playgroup level in estimation of effects. Second, because we had assessed parental behaviors at three time points (baseline, mid-point, and post-test), we used HLM to model the trajectory in parent behaviors over these time points, as predicted by whether or not they had received PFC.Footnote 2

Thus, in HLM models, time point was placed at Level 1. At Level 2, the child level, we placed the covariates of ADHD status, ODD, sex, medication, IQ, income, and parental education. For these analyses, observed child aggression in the playgroup was included as an additional covariate because this child behavior might influence parental responses. Crucially, we tested the effect of receipt of PFC (at Level 2) as a predictor of the slope of change in the parent behavior (the criterion variable) over the three time points. Level 3, the playgroup level, had no predictors but controlled for shared variance. Further details about HLM models may be found in Mikami, Jack, Emeh, and Stephens, this issue, or obtained from the first author. If PFC was associated with increases in playdates, socialization, facilitation, corrective feedback, praise, and warmth (and decreases in criticism), this hypothesis would be confirmed.

Third, we tested the potential for changes in parental behaviors to mediate improvements in child social functioning by first selecting only (a) the child peer relationship measures, and (b) the parental behaviors for which changes as a result of PFC were found. A standardized residual for each parental behavior was calculated to estimate change on that measure over the study period. Using the procedure of Baron and Kenny (1986), we conducted hierarchical multiple regressions to predict the criterion variables of child social functioning at post-test, with the baseline measure of functioning at step 1. At step 2 we placed the indicator of whether PFC was received, and then, in order to reduce the number of regressions conducted, at step 3 we placed all the standardized residuals of parental behaviors together. Then, we reconducted regressions while switching the order of steps 2 and 3, so that step 2 included the standardized residuals of parental behaviors, and step 3 contained PFC. We considered the criteria for mediation met if, in the first set of regressions, the standardized residual of a parental behavior was significant in predicting the outcome after control of PFC, and in the second set of regressions, after control of the change in that parental behavior, the effect of PFC was reduced to nonsignificance.

As an exploratory analysis, we computed interaction terms between PFC and (a) sex, (b) ODD, and (c) medication status to examine whether treatment response was moderated by these constructs. In order to minimize the number of analyses conducted, all interaction terms were placed together and added to the models subsequent to testing the main effects, and interactions were only tested for the primary outcome variables of child social functioning. We also note that results were identical when analyses used ADHD subtype (ADHD-I, ADHD-C, comparison) as opposed to ADHD versus comparison, so subtypes are collapsed herein.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 shows that there were no significant differences between ADHD-PFC and ADHD-control groups at baseline on any peer relationship measures. However, as expected, comparison children were better functioning in peer relationship measures relative to children with ADHD. The ADHD group scored about one standard deviation (SD) below national norms on social measures, and this is similar to the impairment seen in other large samples of children with ADHD (Barkley 2006). We examined distributions of all study variables. Hosted playdates was skewed, so the square root of this variable was used in analyses; however, other variables with lesser skew were not transformed in order to capture meaningful variation. Outliers more than 3.5 SDs beyond the mean were trimmed to values exactly 3.5 SDs from the mean; this occurred for child aggression (n = 3) and DSAS “dislike and reject” (n = 3). See Mikami, Jack, Emeh, and Stephens, this issue, for further details.

Effects of PFC on Child Social Functioning

Social Skills (SSRS)

After accounting for demographic covariates and baseline parent reports on the SSRS, receipt of PFC predicted higher parent reports of the child’s social skills on the SSRS at post-test.Footnote 3 Effect size was between small and medium. There were no interactions between treatment and either sex, ODD, or medication status. Receipt of PFC was not significantly related to changes in teacher report SSRS. However, there was an interaction between treatment and child ODD, F(114) = 4.96; p = 0.03. Probing suggested that the positive effect of PFC on teacher reports of child social skills may be positive for the children without ODD, β = 0.16; p = 0.04, but not significant for those with ODD, β = −0.09; p = 0.47. Please see Table 4.

Quality of Playdates (QPQ)

Table 4 shows that after statistical control of covariates, receipt of PFC was associated with reductions in both the amount of conflict and the amount of disengagement that children displayed on playdates, as reported by parents. Effect size was between small and medium for conflict and between medium to large for disengagement. There were significant interactions between PFC and ODD for both conflict F(116) = 4.26; p = 0.04, and disengagement, F(116) = 4.59; p = 0.03. The benefit of PFC appeared strongest for youth with ODD in reduced conflict, β = −0.55; p < 0.01, and disengagement, β = −0.61; p < 0.01. For youth without ODD, reduction in conflict was β = −0.15 (p = 0.03) and disengagement was β = −0.25 (p = 0.01).

Social Acceptance (DSAS)

Receipt of PFC was associated with increases in teacher report of the proportion of classroom peers who “like and accept” the child, and also decreases in teacher report of classroom peers who “dislike and reject” the child. Effect sizes were between small and medium (Table 4). There were no interactions for the dependent variable of “like and accept”. However, there were interactions between treatment and medication status, F(115) = 6.68; p = 0.01, and between treatment and sex, F(115) = 4.18; p = 0.04, in predicting teacher report of peers who “dislike and reject” the child. Probing revealed that the effect of PFC in reducing “dislike and reject” was stronger for girls, β = −0.62; p < 0.01, relative to boys, β = −0.06; p = 0.59, and for medicated youth, β = −0.40; p < 0.01, relative to unmedicated youth, β = 0.09; p = 0.55.

One-month Follow-up

After statistical control of covariates, parents who received PFC reported significant continued improvement in their children’s friendships occurring since the post-test assessment point, relative to parents who did not receive PFC, F(1,110) = 27.62; p < 0.01. Using a Likert scale (1= very much worse, 2=worse, 3=same, 4=better, 5=very much better), the mean for the ADHD-PFC group was 4.0 (SD = 0.7), the mean for the ADHD-control group was 3.2 (SD = 0.6), and the mean for the comparison group was 3.0 (SD = 0.5).

Effects of PFC on Parental Behaviors

Playgroup Free Play

Regarding the parental behaviors observed in the children’s free play period, receipt of PFC predicted increases in the amount parents were observed to facilitate their children’s behaviors with peers in the playgroup, t(113) = 2.11; p = 0.04. Similarly, receipt of PFC significantly predicted increases in the amount parents were observed to be providing corrective feedback to their children in the playgroup, t(113) = 2.28; p = 0.02. However, there were no PFC-related changes in the amount parents were observed to be socializing with other parents, t(113) = −0.30; p = 0.76.

Parent-child Interaction

After control of covariates, receipt of PFC predicted reductions in parental criticism, t(113) = −2.01; p < 0.05 in the parent-child interaction that occurred after the playgroup. There were no significant changes in the amount of praise observed in the parent-child interaction, but there was a trend towards increased praise as a result of PFC, t(113) = 1.98; p = 0.050. Receipt of PFC did not predicted changes in observed warmth, t(113) = 0.85; p = 0.40.

Playdates Hosted

Receipt of PFC did not predict changes in the number of playdates arranged by parents, F(118) = 0.96; p = 0.33.

Change in Parental Behaviors as Mediators of Effects of PFC on Peer Relationships

Increases in observed parental facilitation significantly predicted improvements in parent-reported social skills (SSRS) after control of whether or not PFC was received, β = 0.14; p < 0.05, but none of the other parental variables on which change was suggested (corrective feedback, criticism) did so. After accounting for the effect of the change in parental facilitation, the effect of PFC on increases in parent-reported social skills was no longer significant, β = 0.03; p = 0.71.

Decreases in parental criticism predicted improvements in teacher report of peers who “like and accept” the child (DSAS) after control of PFC, β = −0.14; p = 0.04, but none of the other parental variables did so. After accounting for the change in parental criticism, the effect of PFC on predicting increases in teacher-reported “like and accept” (DSAS) was no longer significant, β = 0.02; p = 0.79. None of the changes in parental behaviors predicted improvements in DSAS “dislike and reject” or parent report of conflict or disengagement on playdates (QPQ).

Participant Satisfaction

Twenty-seven of the 32 parents randomly assigned to PFC attended 100% of the eight treatment sessions. The parents who did not complete PFC stated that the time commitment required to attend the sessions was too great (n = 3), thought it was not relevant for their child’s problems (n = 1), and had a personal emergency unrelated to PFC (n = 1). On average, parents self-reported that they had completed 70.1% of the homework assignments. The mean weekly rating for usefulness of the session was 6.01 (SD = 1.06) on the Likert scale of 1–7 (1=strongly not useful, 4=neutral/unsure, 7=strongly useful). All parents who had attended at least one session were also asked to complete a consumer satisfaction survey as part of their post-test assessment. Most (60.7%) reported they would “highly recommend” PFC, 35.7% indicated they would “recommend” PFC, 3.6% were “neutral” (one parent), and none indicated that they would “not recommend” or “strongly not recommend” PFC to other families of children with ADHD.

Normalization Analyses

Visual inspection of the raw means in Table 3 shows that overall, the treated group of children with ADHD improved on most measures, but comparison children remained better adjusted relative to both the treated and untreated ADHD groups. The one exception is for conflict and disengagement in playdates (QPQ), where the means for the ADHD-PFC group, but not the ADHD-control group, fell within the range of the comparison sample by post-test. Based on the suggestions of Jacobson and Truax (1991), we considered individuals with scores at least two SDs from the mean of the functional sample to be reliably outside the normative range. Because Jacobson and Truax (1991) recommend using well-normed measures to derive these calculations, we considered the parent SSRS social skills standard score. Following this criterion, 25.8% of the ADHD-PFC group and 30.0% of the ADHD-control group scored ≤70 at pre-test on the SSRS, deeming them outside the standardized mean of 100 (SD = 15). At post-test, however, only 6.9% of the ADHD-PFC group scored ≤70, whereas 30.0% of the ADHD-control group fell outside the normative range.

Discussion

We found that PFC, a novel treatment to improve the peer relationships of children with ADHD, showed some beneficial effects: Parents reported increases in the child’s social skills and reduced conflict and disengagement that occurred during playdates, and teachers reported increases in classroom peers that accept the child and decreases in peers that reject the child. PFC also predicted increases in observed parental facilitation and corrective feedback, and reductions in observed parental criticism during the child’s lab-based peer interactions. However, significant main effects were not found on parent report of playdates hosted or teacher reports of the child’s social skills.

Although most mediator analyses were not significant, there were suggestions that reductions in observed parental criticism during the child’s peer interaction accounted for PFC-related increases in teacher report of classroom peers who accept the child. Increases in observed parental facilitation during the child’s peer interaction accounted for PFC- related increases in parent-report of the child’s social skills. These results strengthen the conclusions obtained from cross-sectional analysis in (Mikami, Jack, Emeh, and Stephens, this issue), that these parental behaviors may indeed contribute to, not just result from, better child functioning with peers.

That PFC-related improvements were found in child social functioning on both parent and teacher report measures (when teachers were unaware of treatment condition), and for some observational measures of parent behaviors, bolsters confidence in results. Nonetheless, without peer-report measures, it is unknown if teacher reports of improvement in peer acceptance reflect actual sociometric changes. A considerable body of literature suggests that peers possess cognitive biases which may serve to maintain the negative reputation of a child with ADHD, even in the face of improved behavior by that child (see Mikami et al. in press). It is possible that even if parents succeed in optimally coaching their child towards displaying skilled behavior, other interventions are needed to change the perceptions of the peer group so that the child’s improvements are noticed. Nonetheless, parents receiving PFC are encouraged to network with other parents of their children’s peers, which may change other families’ impressions of the child with ADHD. Second, in PFC parents are taught to create a social context using playdates so that their child’s good behaviors are likely to become salient to the invited peer in this setting.

We also note that even though the name of the treatment was “Parental Friendship Coaching”, PFC focused on a broad range of peer skills, some specifically geared to close friendship (such as behavior on dyadic playdates, selecting the right friend, and skills in playing games suited for two children) but others related to social competence more generally. Treatment-related improvements were demonstrated some measures of friendship and social competence (adult-informant ratings of friendship quality on playdates, social skills, and peer acceptance), but not in others (parent-report of number of playdates). We speculate that PFC may ultimately be more effective in improving friendships than peer acceptance, because it is easier to change the perception of one close peer than to address the reputational bias of the entire peer group. Crucially, friendship may buffer youth against negative outcomes, even if they remain sociometrically unpopular (Ladd 1990). Unfortunately more measures of friendship were not used in the current study, but a future direction is to increase the emphasis on friendship in PFC and to include better assessment of friendship.

Other limitations involve the follow-up period assessment. This period of 1 month was quite short. Further, a single, non-standardized parent report measure was used to assess child social functioning at follow-up, and this measure was not given at baseline or post-test. Standardized measures, teacher report, or observational data are needed to strengthen speculations that children maintained gains after treatment ceased. In addition, the measure of parental socialization in the lab may not have been the most sensitive test of treatment effects. Although an emphasis in PFC was on teaching parents to socialize with other parents, they were predominately instructed to do so with the parents of possible friends of their children, and not in every global situation; the parents in our study may not have viewed the playgroup peers as having the potential to deepen a friendship with their child.

However, it is notable that for all child outcome measures, treated youth demonstrated improvement over the control group. Effect sizes were generally small to medium (d = 0.25–0.59). These effects compare favorably to those obtained in a meta-analysis of 35 social skills training interventions for youth with behavioral disorders, which reports the average effect size to be d = 0.19, or small (Quinn et al. 1999). More specifically related to ADHD, in a social skills intervention for children in this population, Antshel and Remer (2003) found most effect sizes at post-treatment to be nonsignificant and very small. By contrast, some of the most successful programs in the ADHD literature, which importantly involve parent training conducted concurrently with child groups, report medium to large effect sizes on social outcomes (Frankel et al. 1997; Pfiffner et al. 2007). Still, our effect sizes, which were obtained in a parent-only intervention, suggest that PFC may make a promising contribution to clinical practice, where it is sometimes impractical to conduct concurrent parent and child treatments. It is unknown whether the addition of a child treatment component to PFC may improve effectiveness. Because children’s comprehension of their parents’ coaching is a necessary condition for the success of PFC, we speculate that child treatment may prime some children to be more receptive to their parents’ efforts. However, the incremental efficacy of adding child treatment to PFC, or the optimal duration of child sessions, remains an empirical question.

Finally, findings for moderation of treatment by sex, medication status, and ODD comorbidity were not compelling, in that there were few interactions, and more importantly, the direction of effects was often contradictory between parents relative to teachers. Thus, in the absence of additional information, it may be that PFC is equally effective for these subgroups. Importantly, our findings also suggest that medicated youth with ADHD can benefit from the addition of psychosocial treatment, which has not been the case in notable large randomized controlled trials (Abikoff et al. 2004; MTA Cooperative Group 1999a).

In sum, results support a potentially intriguing model that parents can be trained to intervene in their child’s peer problems, without any child treatment component. PFC requires intensive parent involvement which may not be feasible for some families in clinical practice. However, for some families, making the parent the target of treatment may reduce stigmatization of the child for needing services and help to manage the resistance some children have towards individually-focused interventions.

Notes

Because of concerns raised by reviewers about the validity of changes in playgroup sociometric measures over the treatment period, they were not analyzed as primary outcomes. However, little change was suggested over the course of the three playgroups on sociometric measures overall, for either intervention-group or control-group children.

We note that, because parents were nested into six treatment groups, we also considered that treatment effects might be correlated between parents in the same PFC group. However, because the proportion of variance at the PFC group level for all outcome measures was low (all <5%, most <1%), accounting for the nested structure of parents into PFC groups was not needed (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002).

When full information maximum likelihood methods were not used for analyses, the significance level of PFC on the dependent variable of parent SSRS changed to F(1,111) = 3.85; p = 0.052. The effect of PFC on the other primary dependent variables of conflict and disengagement on playdates (QPQ) and classroom peer acceptance and rejection (DSAS) all remained significant at p < 0.05 when full information maximum likelihood methods were not used.

References

Abikoff, H. B., Hechtman, L., Klein, R. G., Gallagher, R., Fleiss, K., Etcovitch, J., et al. (2004). Social functioning in children with ADHD treated with long-term methylphenidate and multimodal psychosocial treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 820–829.

Achenbach, T. M. (1991a). Manual for child behavior checklist and revised child behavior profile. Burlington: University Associates in Psychiatry.

Achenbach, T. M. (1991b). Manual for teacher’s report form and 1991 profile. Burlington: University Associates in Psychiatry.

Antshel, K. M., & Remer, R. (2003). Social skills training in children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: a randomized-controlled clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 153–165.

Barkley, R. A. (2004). Adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an overview of empirically based treatments. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 10, 39–56.

Barkley, R. A. (2006). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Beelman, A., Pfingsten, U., & Losel, F. (1994). Effects of training social competence in children: a meta-analysis of recent evaluation studies. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 23, 260–271.

Bierman, K. L., Miller, C. M., & Stabb, S. (1987). Improving the social behavior and peer acceptance of rejected boys: effects of social skills training with instructions and prohibitions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 194–200.

Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., & Coppotelli, H. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: a cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18, 557–570.

Conners, C. K. (2001). Conners’ Rating Scales-Revised technical manual. New York: Multi-Health Systems Inc.

de Boo, G. M., & Prins, P. J. M. (2007). Social incompetence in children with ADHD: possible moderators and mediators in social skills training. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 78–97.

Dishion, T. J. (1990). The peer context of troublesome child and adolescent behavior. In P. E. Leone (Ed.), Understanding troubled and troubling youth: Multiple perspectives (pp. 128–153). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Dishion, T. J., & Kavanagh, K. (2003). Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. New York: Guilford.

Frankel, F. (2003). Measuring the quality of play dates.Unpublished manuscript.

Frankel, F., Myatt, R., & Cantwell, D. P. (1995). Training outpatient boys to conform with the social ecology of popular peers. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 24, 300–310.

Frankel, F., Myatt, R., Cantwell, D. P., & Feinberg, D. (1997). Parent-assisted transfer of children’s social skills training: effects on children with and without attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 1056–1064.

Gadow, K. D., & Sprafkin, J. (1994). Child Symptom Inventories manual. Stony Brook: Checkmate Plus.

Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (1990). Social skills rating system. Circle Pines: Assistance Service.

Hodgens, J. B., Cole, J., & Boldizar, J. (2000). Peer-based differences among boys with ADHD. Journal of Child Clinical Psychology, 29, 443–452.

Hoza, B., Mrug, S., Pelham, W. E., Greiner, A. R., & Gnagy, E. M. (2003). A friendship intervention for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: preliminary findings. Journal of Attention Disorders, 6, 87–98.

Hoza, B., Gerdes, A. C., Mrug, S., Hinshaw, S. P., Bukowski, W. M., Gold, J. A., et al. (2005). Peer-assessed outcomes in the Multimodal Treatment Study of children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 74–86.

Hoza, B., Mrug, S., Gerdes, A. C., Bukowski, W. M., Kraemer, H. C., Wigal, T., et al. (2005). What aspects of peer relationships are impaired in children with Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 411–423.

Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 59, 12–19.

Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Brent, D., Rao, U., Flynn, C., Moreci, P., et al. (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 695–702.

Ladd, G. W. (1990). Having friends, keeping friends, making friends, and being liked by peers in the classroom: predictors of children’s early school adjustment? Child Development, 61, 1081–1100.

Ladd, G. W., & Hart, C. H. (1992). Creating informal play opportunities: are parents’ and preschoolers’ initiations related to children’s competence with peers? Developmental Psychology, 28, 1179–1187.

Mikami, A. Y., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2006). Resilient adolescent adjustment among girls: buffers of childhood peer rejection and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26, 823–837.

Mikami, A. Y., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2008). Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in girls. In K. McBurnett & L. J. Pfiffner (Eds.), Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Concepts, controversies, new directions (pp. 259–272). New York: Informa Healthcare.

Mikami, A. Y., Lerner, M. D., & Lun, J. (in press). Social context influences on children’s rejection by their peers. Child Development Perspectives.

Mrug, S., Hoza, B., & Gerdes, A. C. (2001). Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: peer relationships and peer-oriented interventions. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 91, 51–77.

MTA Cooperative Group. (1999a). A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 1073–1086.

MTA Cooperative Group. (1999b). Moderators and mediators of treatment response for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 1088–1096.

Parke, R. D., Burks, V. M., Carson, J. L., Neville, B., & Boyum, L. A. (1994). Family-peer relationships: A tripartite model. In R. D. Parke & S. G. Kellam (Eds.), Exploring family relationships with other social contexts (pp. 115–146). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Pelham, W. E., Wheeler, T., & Chronis, A. M. (1998). Empirically supported psychosocial treatments for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child Clinical Psychology, 27, 190–205.

Pfiffner, L. J., & McBurnett, K. (1997). Social skills training with parent generalization: treatment effects for children with attention deficit disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 749–757.

Pfiffner, L. J., Mikami, A. Y., Huang-Pollock, C. L., Easterlin, B., Zalecki, C. A., & McBurnett, K. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of integrated home-school behavioral treatment for ADHD, Predominantly Inattentive Type. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 1041–1050.

Quinn, M. M., Kavale, K. A., Mathur, S. R., Rutherford, R. B., & Forness, S. R. (1999). A meta-analysis of social skills interventions for students with emotional or behavioral disorders. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 7, 54–65.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Russell, A., & Finnie, V. (1990). Preschool children’s social status and maternal instructions to assist group entry. Developmental Psychology, 26, 603–611.

Wechsler, D. (2003). Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—Fourth Edition (WISC-IV). New York: Psychological Corporation/Harcourt Brace.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by NIMH grant 1R03MH12838 to Amori Mikami. We would like to thank the children, parents, and teachers who participated, and the schools and doctors who provided referrals for this study. We are grateful to the graduate students who served as therapists on this project: Jennifer Cruz, Jena Saporito Fisher, and Tara Grover. We also appreciate the consultation of Betsy Hoza and Linda Pfiffner on the therapeutic intervention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mikami, A.Y., Lerner, M.D., Griggs, M.S. et al. Parental Influence on Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: II. Results of a Pilot Intervention Training Parents as Friendship Coaches for Children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 38, 737–749 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9403-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9403-4