Abstract

Studies have shown that improved parenting mediates treatment outcomes for aggressive children, but we lack fine-grained descriptions of how parent–child interactions change with treatment. The current study addresses this gap by applying new dynamic systems methods to study parent–child emotional behavior patterns. These methods tap moment-to-moment changes in interaction processes within and across sessions and quantify previously unmeasured processes of change related to treatment success. Aggressive children and their parents were recruited from combined Parent Management Training and Cognitive-behavioral programs in “real world” clinical settings. Behavioral outcomes were assessed by reports from parents and clinicians. At pre- and post-treatment, home visits were videotaped while parents and children discussed consecutively: a positive topic, a mutually unresolved problem, and another positive topic. Results showed that significant improvements in children’s externalizing behavior were associated with increases in parent–child emotional flexibility during the problem-solving discussion. Also, dyads who improved still expressed negative emotions, but they acquired the skills to repair conflicts, shifting out of their negative interactions to mutually positive patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Perhaps the most thoroughly studied childhood behaviour problem is aggression. Much has been accomplished in terms of establishing the risk factors, developmental trajectories, and long-term outcomes of childhood aggression. This research base has long-informed treatment development and implementation. Interventions for childhood aggression are among the most thoroughly researched, with several randomized clinical trials having shown the efficacy of a handful of treatment modalities (e.g., Brestan and Eyberg 1998; Kazdin 2001). Despite this considerable progress, significant gaps in the intervention literature persist. Specifically, Kazdin (2002) and Hinshaw (2002), as well as other scholars, have argued that not enough attention has been paid to (1) the processes of change related to treatment success and (2) how treatment works in “real world” settings. The current study is a preliminary attempt to address these limitations as they apply to interventions with aggressive children and their families.

Specifically, despite the success of empirically-based interventions for aggressive children, there remains considerable variability in treatment outcome and effect sizes are generally moderate (e.g., Brestan and Eyberg 1998; Dumas 1989; Kazdin 2001). We do not know why some children fail to show improvements because we have little understanding of the change process itself. What exactly changes when treatment works for aggressive children (and, conversely, when these interventions are ineffective, what fails to change)? Moreover, are these mechanisms of change accessible to families in “real world” community settings?

Flexibility in Parent–child Interactions

Several studies have shown that improvement in parenting (e.g., decreases in coercive parenting, increases in effective discipline practices) is one of the means by which successful outcomes are achieved (Forgatch and Degarmo 1999; Martinez and Forgatch 2001; Patterson et al. 1982). What is less clear is how global measures of parenting such as coercion manifest in changes in moment-to-moment parent–child interactions. We are most interested in these changes in parent–child interactions because we view real-time interactions as the proximal engines of development (Bronfenbrenner and Morris 1998; Snyder and Stoolmiller 2002). If moment-to-moment, day-to-day direct experiences are the “materials” out of which antisocial outcomes emerge, then they must also be the context through which these outcomes change. But it is unclear what exactly changes when children become less aggressive.

An implicit, if not explicit, assumption made by most clinicians and clinical researchers is that, when treatment works, family interactions change from being emotionally “negative” or “angry” to “positive” or “supportive.” But according to emotion theorists (e.g., Izard 1977; Magai and McFadden 1995; Tomkins 1963), the expression of anger or any other negative emotion is not pathogenic; all emotions are adaptive and important to express in appropriate contexts. It is the effective regulation of these emotions that is critical for healthy development (e.g., Cole et al. 2004; Southam-Gerow and Kendall 2002). Indeed, recent research supports the association between young children’s poor emotion regulation and externalizing outcomes (see Southam-Gerow and Kendall 2002 for a review).

Developmentalists agree that, in general, regulation skills are learned and practiced in the context of parent–child interactions. We go on to propose that flexibility in these interactions (i.e., the ability to shift from one emotional state to another, according to contextual demands) may be more important for healthy development than the complete avoidance of negative affect (see also Gottman and Notarius 2000, for a similar suggestion for marital relationships). This conceptualization is similar to the control vs regulation distinction made by Cole et al. (1994). They suggest that emotion regulation often involves the adjustment and “dynamic ordering” of emotional behavior, not just dampening negative emotions. Thus, healthy parent–child interactions may need to be emotionally flexible and reparative not simply “positive.”

A recently completed study supports the link between emotional flexibility in parent–child interactions and the prevention of childhood aggressive behavior (Hollenstein et al. 2004). This prospective study applied dynamic systems methods to analyze hundreds of parents and their prosocial and aggressive young children (about 5 years old at the beginning of the study). Parent–child dyads were videotaped interacting with one another while they engaged in different types of activities (e.g., playing games, problem-solving, cleaning up a mess). Results showed that rigid (inflexible) parent–child patterns measured in the fall of Kindergarten predicted aggressive behavior 18 months later. Compared to normally developing children, those children who developed problem behaviors expressed a smaller range of emotions and they became stuck with their parents for longer periods of time in one or very few emotional states. For example, it was common for families with children who became aggressive to become angry in the problem-solving interaction and then remain angry when asked to change activities (for instance, play a game). But it was just as common for these families to show neutral states across all activities. It was not the content of the emotions that predicted future problematic behavior but the inability to experience a variety of emotional states as the context shifted. Extending these insights to intervention processes, families that benefit from treatment may still engage in negative exchanges. However, what changes as a function of treatment may be the ability to quickly shift out of, and repair, these aversive interactions.

Dynamic Systems Analysis

One key reason why change processes associated with interventions have not been a main focus of research is that, until recently, researchers lacked the appropriate methodological tools to study them effectively (Cicchetti and Cohen 1995; Granic and Hollenstein 2003; Richters 1997). We have attempted to address this gap by developing new methods based on dynamic systems (DS) principles. DS theorists use the concept of a state space to represent the range of stable behavioral habits, or attractors, for a given system. Behavior is conceptualized as moving along a real-time trajectory on this hypothetical landscape, being pulled towards certain attractors and freed from others (e.g., Lewis 2000). Based on these abstract formalisms, Lewis et al. (1999) developed state space grid (SSG) analysis, a graphical approach that quantifies observational data according to a map constructed from two ordinal variables. Granic and colleagues extended this methodology to represent dyadic behavior as it changes moment-to-moment (e.g., Granic et al. 2003; Granic and Lamey 2002; Hollenstein et al. 2004).

SSGs are particularly well-suited for looking at differences in response to treatment. First, the methodology is both “person-oriented” (or in this case, dyad-oriented) as well as suitable for creating variables for multivariate analyses. This versatility is critical when we are interested in idiosyncratic within-dyad changes and differences between dyads from pre- to post-treatment. In fact, SSGs were developed specifically for tracking longitudinal change in interaction processes. Second, in addition to identifying content-specific changes (e.g., less mutual hostility and more positivity), this method can tap changes in the relative flexibility versus rigidity of parent–child interactions (e.g., number of transitions between states).

Studying Interventions in the “Real World”

Importantly, the current study examined evidence-based treatment as it is practiced in community mental health settings. What we know thus far about the effectiveness of these interventions comes from the academic, research context (Kazdin and Nock 2003). Most clinical research is funded by large-scale grants which allow incentives for family participation in treatment, minimize therapist attrition, provide funds for daycare for siblings, and so on. Community agencies simply do not have access to these resources. Extending intervention research into the “real world” is now a top priority in general (National Advisory Mental Health Council (NAMHC) 1999; National Advisory Mental Health Council’s Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment 2001) and treatment for aggressive children in particular needs to be studied in these settings. A few investigators have taken steps in this direction (e.g., Eddy and Chamberlain 2000; Huey et al. 2000).

Parent Management Training/Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

The clinical agencies with which we partnered for the current study provided Parent Management Training (PMT) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for aggressive children and families, two of the most well-recognized, evidence-based interventions (Dumas 1989; Brestan and Eyberg 1998). Randomized control studies have examined the impact of PMT on children’s problem behavior and confirmed that, on average, PMT decreases children’s level of aggression (Forgatch and Degarmo 1999; Martinez and Forgatch 2001; Patterson et al. 1982). Combining PMT with CBT has also been shown to be highly effective (Tremblay et al. 1995; Webster-Stratton and Hammond 1997). In studies that have compared treatment effects of CBT, PMT and combined programs, combined PMT/CBT was most effective, at least with children from 5 to 12 years old (Kazdin et al. 1992; Lochman and Wells 2004; Webster-Stratton and Hammond 1997).

Our intent was not to add to this corpus of data with another study comparing treated and nontreated children (e.g., in a randomized control design). Rather, it was to examine the high degree of variability in treatment outcomes, and to test the possibility that this variability can be partly explained by process level measures of emotional flexibility in family interactions.

Design and Hypotheses

Direct home observations of parent–child discussions were collected before and after the intervention period. SSG analysis was applied to uncover content-specific changes in parent–child interactions and content-free changes in the relative flexibility of these interactions. In addition, dyads’ ability to repair their conflicts was measured.

The parent–child interactions of children who showed clinically significant improvements (IMPs) were compared to those of children who did not improve (NIMPs). Three hypotheses were tested: (1) Compared to NIMPs, IMP children were expected to become significantly more flexible in their problem-solving interactions from pre- to post-treatment; (2) In contrast, changes in the content of the problem-solving discussions pre- to post-treatment were not expected to predict treatment outcomes; and (3) At post-treatment, more IMP than NIMP dyads were expected to repair their conflict interactions.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Parents and children were recruited from two children’s community mental health agencies that offered the same combined PMT/CBT treatment for aggressive children and their families. At the intake stage of these treatment programs, the parents were asked if they were willing to speak to a research assistant to get more information about the study. If families agreed to be contacted, a research assistant explained the study and asked if the parent and child were willing to participate. Families were offered $10.00 for each home visit.Footnote 1 Forty-one of the 60 families who were approached to participate consented to do so. The most common reason that parents gave for refusing to participate was feeling too much stress in their daily lives. The second most common reason was that their child refused to be involved. Because families who refused to participate in our research, by definition, did not consent to share information about themselves, we did not have the data to compare refusers with participants in the current study.

We began with 41 child participants and their mothers, referred by either a mental health professional, teacher, or parent. The children ranged in age from 7 to 11 years (M = 9.09, SD = 1.2). To be included in the study, children had to score within the clinical range (98th percentile) on the Externalizing subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach 1991a, b). Three children scored below this cutoff and were therefore eliminated from the study, leaving a total N of 38 (34 boys and 4 girls). Mothers and children needed to have sufficient command of the English language to complete questionnaires without an interpreter. The child had to be currently living with the mother. Children were excluded if they were diagnosed as mentally handicapped or if they had a pervasive developmental disorder.

Thirty-three percent of the children resided in intact families, 41% in single-parent (exclusively maternal) households, 20% in blended families, and 6% in other family configurations (e.g., grandparents). Based on parent-identified ethnicity, 74% of the children were European (Caucasian), 13% were African or Carribbean, 2% were Asian, 2% were Latin-American, and 9% were of mixed backgrounds. In terms of family income, 18% made under $20,000 per year, 26% made between $20,000 and $39,000, 26% made $40,000 to $59,000, and 30% made over $60,000.

Intervention

The treatment program was an evidence-based intervention for children between 6 and 12 years of age and their parents. The program is called SNAP™ (Stop Now and Plan; Earlscourt Child and Family Centre 2001a, b; Goldberg and Leggett 1990) and it combines PMT and CBT. The clinical directors of the program have been consulting with the original developer of PMT (Marion Forgatch at the Oregon Social Learning Center) for over 10 years in order to ensure fidelity to the original PMT model. Therapists were either social workers, child-care workers or M.A. or Ph.D.-level clinical psychology students. Like most social welfare programs in Canada, families were not charged for treatment services. The program was delivered to both parents (PMT) and children (CBT) once a week for 12 weeks in a group format. The groups met for 3 h during the evening at the community agencies. In the PMT groups, parents were taught to replace coercive or lax discipline strategies with mild sanctions (e.g., time-out) that contingently target misbehavior (Forehand 1986). The groups also promoted positive parenting practices such as skill encouragement (e.g., providing contingent praise for success, prompting for appropriate behavior), problem-solving, and monitoring (Forgatch and Degarmo 1999; Martinez and Forgatch 2001). In the CBT groups, aggressive behaviors and negatively-biased cognitions were targeted for change through well-documented strategies such as behavior management, role-playing, problem-solving, cognitive restructuring, social and token reinforcements, and generalization activities (Barkley 2000; Bloomquist and Schnell 2002).

As previously reviewed, there are numerous randomized control trials that have established the efficacy of PMT and CBT. In addition, the SNAP™ program itself has undergone two evaluations to assess its effectiveness. A within-group design comparing baseline, discharge (3 months later), and 6- and 12-month follow-up data for 104 children admitted between 1985 and 1988 showed significant decreases in children’s externalizing behaviour (as measured by the CBCL; Achenbach 1991a, b). These treatment gains were maintained over the 6- and 12-month follow-up period (Hrynkiw-Augimeri et al. 1993). A recently completed randomized control trial (Augimeri et al. 2006) indicated that children randomly assigned to the treatment group, compared to an “attention” control group, showed decreases in externalizing scores; treatment gains were maintained over 6- and 12-month follow-up periods. For child- and parent-reported delinquency, effect sizes (d) exceeded 1.2.

Procedure

Data were obtained before the start and after the completion of the 12-week treatment program. As part of the clinical agencies’ regular intake and post-treatment procedures, clinicians and parents were asked by clinic personnel to complete measures of the child’s emotional and behavioral functioning. Parent–child interactions were observed and videotaped in the home by an independent research team. Children from two-parent families were videotaped with their mothers, first because mothers were identified as the primary caregivers, and second to provide consistency with children from single-parent families (which were exclusively mother-led). Before the videotaping began, mothers and children were asked to complete consent forms (assent forms were completed for all children). Children and parents also completed a modified version of the Issues Checklist (Robin and Weiss 1980) which lists a number of potential sources of conflict between parents and children (e.g., bed time, lying, swearing). Participants were seated across from one another (e.g., at a kitchen table, on a couch). The interactions were recorded on a digital video camera in the room with the participants. The research assistant gave instructions before each of the three discussion topics and then left the room.

The first discussion was about a positive, hypothetical topic such as winning the lottery or planning a trip together. These topics were randomly assigned by the research assistant and counterbalanced across participants. The second topic discussion was based on Forgatch et al. (1985) procedure for studying problem-solving in families of antisocial children. The experimenter chose the issue from the Issues Checklist that the parent and child agreed was one of the most anger-provoking topics that remained unresolved. The dyad was instructed to solve the problem as best they could and end on a positive note. Immediately following this second discussion, the parent and child were asked to talk about another positive topic (again, assigned by the research assistant). The first and third discussions (the positive ones) were 4 min long and the second discussion (the conflict issue) was 6 min long.

Coding Procedures

Observational codes were recorded using the Noldus Observer 5.0. Trained observers entered codes for each participant independently in real time, yielding two synchronized streams of continuous data. A simplified version of the Specific Affect coding system (SPAFF; Gottman et al. 1996a, b) was used. Each code was based on a combination of facial expressions, gestures, posture, voice tone, volume, and speech rate that captured a gestalt of the affective tone of each moment of behavior. The modified SPAFF system consisted of ten mutually exclusive affect codes: contempt, anger, fear/anxiety, sad/withdrawn, whine/complain, neutral, interest/curiosity, humor, joy/excitement, and affection.

Prior to initiating coding of the video interactions, observers were intensively trained (for 3 months) to a minimum criterion of 75% agreement and 0.65 kappa using a frequency/sequence-based comparison and a criterion of 80% agreement using a duration/sequence based comparison (Noldus Observer 5.0). Both reliability methods were employed because SSG analysis requires accuracy in the onset of events as well as the duration of these events. Weekly recalibration training was conducted to minimize coder drift. Twenty percent of all sessions were coded by one of four coders and jointly coded by the two coding supervisors. This second file served as the “gold standard” to which each reliability file was compared. Coders were blind to which sessions were used to assess observer agreement. The average coder agreement with the gold standard was 82% and 0.76 kappa for the frequency-based method and 90% for the duration-based method.

Measures

Problem Solving Discussion Topic

The topics for the conflict discussion were chosen from a modified version of the Issues Checklist (Robin and Weiss 1980), completed by the mother and child separately. The conflicts listed in the checklist are common issues for parents and children such as going to bed on time, lying, and fighting with siblings. Participants were asked to identify whether they had argued about each issue in the past two weeks and, if they had, how ‘hot’ the discussion was (on a 5-point scale from calm to angry). Participants also indicated whether or not the issue was resolved. The hottest topic left unresolved (as indicated by both mother and child) was chosen for the conflict discussion.

Clinician Report of Problem Behavior

The Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale (CAFAS; Hodges and Wong 1996) was completed for each child. Before clinicians can complete the CAFAS, they undergo a training period conducted by a CAFAS-certified trainer and are subsequently tested on a number of vignettes; they must achieve a pre-specified level of reliability before they are CAFAS-certified. The CAFAS measures the degree of disruption in the child’s current functioning in eight psychosocial areas. To rate the child, the clinician collects information from multiple informants in different settings including the child’s parents, teachers, and any other significant adults that know the child (e.g., grandparent, school counselor). Each of the eight subscales are rated and scored for level of severity: severe (30), moderate (20), mild (10), and minimal or none (0). For assessing outcomes relevant to externalizing behavior problems, we focused on four scales: “school,” “home,” “community” and “behavior toward others.” The reliability and validity of the instrument have been well established (e.g., Hodges and Wong 1996; Hodges and Gust 1995). Critically, the CAFAS has been shown to be sensitive to clinical change over time (Hodges and Wong 1996; Hodges et al. 1998; Hodges 1999). A decrease of 20 points or more from pre- to post-treatment is considered clinically significant improvement (Hodges and Wong 1996; Hodges et al. 1998).

Parental Report of Externalizing Behavior

Parental ratings of child conduct problems were obtained from the CBCL (Achenbach 1991a, b). The CBCL consists of 113 items and assesses multiple problem areas on a 3-point scale. Parents were asked to rate their child’s behavior for the month prior to the start of treatment and again for the month after the group ended. The CBCL is a standardized, highly reliable and valid measure of children’s emotional and behavioral problems and yields a standardized T-score for Externalizing Problems.

Outcome Group Classification

Children were classified as “Improvers” (IMPs) or “Non-improvers” (NIMPs) based on a combination of information from the CBCL and CAFAS. As a result of the various challenges in doing research in community settings, some outcome measures were not completed (all families participated in both the pre- and post-treatment observational sessions). At pre-treatment, all 38 families completed the CBCLs but at post-treatment, four CBCLs were incomplete. In addition one therapist at each agency left the agency before the end of our study. To take their place, additional therapists had to be trained to reliability on the CAFAS. As a result, CAFASs were not completed for 10 families at pre-treatment and 12 families at post-treatment.

Clinically significant improvement was operationalized as decreasing by at least a half a standard deviation (a T-score of 5 or more) on the CBCL and dropping 20 or more points on the CAFAS (Hodges and Wong 1996; Hodges et al. 1998). If the two measures were inconsistent (i.e., if one measure indicated clinical improvement and the other did not), then priority was given to the information on the CAFAS because it combined information from multiple informants, not just the parent (this was the case for seven families). If the CAFAS was missing, classification was based solely on the CBCL. Based on these criteria, 20 children were classified as IMP and 18 were classified as NIMP. Supporting the internal validity of our group designations, t-test comparisons showed no significant group differences on the CBCL Externalizing scale or the CAFAS at pre-treatment, but significant differences on both scales at post-treatment: for the CBCL t(33) = 2.93, p < 0.01, and for the CAFAS, t(25) = 3.11, p < 0.01.

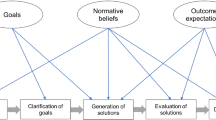

State Space Grid Analysis

In order to test our hypotheses, SSGs were constructed for all dyads for pre- and post-treatment observational sessions. With this method, the dyad’s trajectory (i.e., the sequence of behavioral states) is plotted as it proceeds in real time on a grid representing all possible behavioral combinations (Granic and Lamey 2002; Granic et al. 2003). One dyad member’s (e.g., parent’s) coded behavior is plotted on the x-axis and the other member’s (e.g., child’s) behavior is plotted on the y-axis. Each x–y coordinate represents a period of time in a particular state, a two-event sequence or a simultaneously coded parent–child event (i.e., a dyadic state). A trajectory is drawn through the successive dyadic points in the temporal sequence they were observed. SSGs were constructed separately for each dyad at pre- and post-treatment and for each discussion type (positive and conflict discussions). Figure 1 shows the template SSG on which all dyadic trajectories were mapped. On each of the axes, the SPAFF codes for the parent and child are represented on a quasi-ordinal scale from the most aversive emotions (contempt) to the most positive (affection). A hypothetical trajectory representing 21 s of coded behavior is presented in Fig. 1: the interaction starts with 2 s in contempt/contempt,Footnote 2 then 10 s in contempt/interest, 2 s in neutral/neutral, 5 s in neutral/anger, and 2 s in anger/anger. The shaded areas represent regions of theoretical interest in terms of the content of parent–child interactions.

State space with the four regions of interest and a dyadic trajectory representing the following sequence of events: 2 s in contempt/contempt, then 10 s in contempt/interest, 2 s in neutral/interest, 5 s in neutral/anger, and 2 s in anger/anger. The size of the circles represents the amount of time spent in that state (the longer the duration in the cell, the larger the circle)

To quantify different aspects of parent–child flexibility, several parameters were calculated from the grids: (1) Transitions (TRANS): a count of the number of movements between cells on the grid. A higher value on this measure indicates more frequent changes of dyadic behavioral states and therefore more flexibility; (2) Dispersion (DISP): The sum of the squared proportional durations across all cells corrected for the number of cells and inverted so that values range from 0 (no dispersion at all–all behavior in one cell) to 1 (maximum dispersion). This measure is created by the formula: \( {{\left[ {{\left( {n{\left( {di \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {i D}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} D} \right)}^{2} } \right)} - 1} \right]}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\left[ {{\left( {n{\left( {di \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {i D}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} D} \right)}^{2} } \right)} - 1} \right]}} {n - 1}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {n - 1} \), where D is the total duration, d is the duration in cell i and n is the total number of cells. Higher values indicate more flexibility; and (3) Average Mean Duration (AMD): The mean of the duration of each visit. This variable captures the overall “stickiness” of dyadic behavior. In contrast to the first two measures, high AMD values indicate a less flexible dyad (they remain in a state for long periods of time). The reliability of TRANS and AMD has been reported in studies examining parent–child and adolescent interactions (Granic et al. 2003; Hollenstein et al. 2004). Both measures have been shown to exhibit high test–retest reliability and moderate predictive validity.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Before proceeding to the main analyses comparing clinical improvers to non-improvers, we examined differences on the CBCL and CAFAS for the sample as a whole. Paired-sample t-tests revealed significant decreases from pre- to post-treatment on both the CBCL Externalizing subscale mean scores, M pre = 75.11, SD = 4.33; M post = 70.57, SD = ; 7.11; t (34) = 4.72, p < 0.0001, and the total score of the four relevant CAFAS mean scores, M pre = 94.58, SD = 27.50; M post = 60.42, SD = 34.83; t (24) = 5.03, p < 0.0001. For the sample as a whole, on average, the intervention seemed to have decreased levels of externalizing behavior.

Next, we examined whether outcome groups (IMPs and NIMPs) differed according to any demographic variables reported at pre-treatment. One-way ANOVAs were conducted on maternal age (M = 38.3) and child age (M = 9.1). Chi-square analyses were performed on three categorical variables: (1) ethnicity, (2) mother’s highest level of education, and (3) parent’s marital status. No significant differences between IMPs and NIMPs were found on any of these comparisons.

Flexibility in Problem-solving Discussions

The first set of analyses addressed the hypothesis that IMPs, but not NIMPs, would show significant increases in the flexibility of their parent–child interactions from pre- to post-treatment. As described in the previous section, three measures of flexibility were derived from the grids for pre- and post-treatment problem-solving sessions (the second discussion): TRANS, AMD, and DISP. Means and standard deviations for these measures are displayed by group in Table 1. First, we compared IMPs and NIMPs on the flexibility measures at pre-treatment: no significant differences were found. Next, we ran separate repeated measures ANOVAs for each flexibility measure to examine changes from pre- to post-treatment. No main effects were found for any of the analyses. As predicted, results showed significant group x flexibility interaction effects for all three flexibility measures: TRANS, F(1, 35) = 8.89, p < 0.01. and AMD F(1, 35) = 7.35, p = 0.01 and DISP, F (1, 35) = 4.55, p < 0.05. Thus, on all three measures, IMPs showed an increase in flexibility from pre-to post-treatment while NIMPs showed the opposite pattern.

Another analytic strategy for addressing our first hypothesis was to examine the correlations between our outcome measures (CBCL and CAFAS) and the flexibility measures for the sample as a whole. No significant correlations were found among outcome and flexibility measures at pre-treatment. However, as expected, post-treatment CAFAS scores were significantly associated with all three flexibility measures (TRANS: r = −0.55, p < 0.01; DISP: r = −0.38, p < 0.05; AMD: r = 0.46, p < 0.05)—higher flexibility scores were related to lower externalizing scores in all cases. Correlations with CBCL scores were in the right direction, but not significant.

Content Analysis

The second set of analyses examined whether IMP and NIMP groups would differ on pre- to post-treatment changes in the content of the problem-solving interactions. We divided the SSGs for all dyads into four specific regions, representing the emotional content that might be expected to differentiate groups. As shown in Fig. 1, these regions were labeled: mutual positivity (both the mother and child are expressing positive emotions), mother attack (the child is either positive, neutral, or expressing sadness or anxiety and the mother is angry or contemptuous), mutual hostility (both the parent and child are whining, angry or contemptuous) and permissiveness (the child is whining, angry or contemptuous and the mother is expressing positive emotions).

For each region, duration means and standard deviations at pre- and post-treatment are presented separately by outcome group in Table 2. First, to examine whether outcome groups’ parent–child interactions differed in content prior to treatment, we compared groups on pre-treatment durations in each region: no significant differences were found. Next, we compared outcome groups on the change in the total duration spent in each of the regions. As predicted, repeated measures ANOVAs revealed no differences between the groups in the change in the total duration spent in any of the negative regions: mother attack, mutual hostility, and permissiveness. There was no main effect of groups and the region x group interaction was not significant for any of these three negative regions (F values ranged from 0.08 to 0.30). Contrary to expectations, however, there was a significant region x group interaction effect for the total duration in the mutual positivity region, with IMPs showing an increase and NIMPs showing a decrease, F(1, 35) = 6.22, p < 0.05.

Emotional Repair

Finally, we expected that at post-treatment, IMPs would be more likely than NIMPs to repair their conflict interactions. To test this hypothesis, we examined post-treatment SSGs for the third, positive topic discussion. We classified dyads based on whether they were able to become mutually positive or neutral in the third discussion (immediately following the conflict discussion). Repair in the third discussion was operationalized as no time spent outside of the mutual neutral or positive regions of the state space. Figure 2 shows an example of a dyad who was unable to repair. In contrast, Fig. 3 depicts a dyad who did repair. After classifying dyads’ SSGs on “repair” or “no repair,” we ran a chi-square analysis with outcome groups (IMP and NIMP). A significant association was found in the predicted direction (χ 2 = 5.15, p < 0.05). As shown in Fig. 4, the majority of IMPs were able to repair their interactions whereas the majority of NIMPs were not. When the same analysis was performed on pre-treatment repair, no relation was found between outcome groups and the tendency to repair (χ 2 = 1.63, ns).

Discussion

The processes of change associated with successful interventions are rarely studied (e.g., Hinshaw 2002; Kazdin 2002). Moreover, these change processes are not studied in the context of “real-world” interventions for aggressive children and their families. The main objective of the present study was to begin addressing these gaps by examining how parent–child interactions change as a function of successful treatment for childhood aggression. Compared to children who failed to show clinically significant improvements in problem behavior, children who benefited from treatment were expected to: (1) show an increase in flexibility in parent–child interactions from pre- to post-treatment and (2) show evidence of repair processes after a problem-solving interaction at post-treatment. No differences between outcome groups were expected in changes in the content of parent–child interactions.

Our first prediction was supported by the data. IMPs, but not NIMPs, showed increases in the flexibility of their parent–child problem-solving interactions over the course of treatment. After treatment, IMPs showed increases in the number of times they changed emotional states, the breadth of their behavioral repertoire, and decreases in the amount of time they spent “stuck” in any one emotional state. Unexpectedly, however, NIMPs became more rigid after treatment.

There are at least two ways to interpret these results. First, some minimal level of emotional flexibility in parent–child relationships may be necessary for children’s healthy, adaptive development. Indeed, at least one previous prospective study has shown a relation between high levels of rigidity (a lack of flexibility) in parent–child interactions and the development of aggressive behavior problems (Hollenstein et al. 2004). Our results suggest that rigid interactions are amenable to change and that this change may be one mechanism through which improvements in children’s problem behavior are realized.

A second interpretation of our findings is that an increase in flexibility at post-treatment is a temporary phase through which parent–child interactions must pass for children’s behavior to improve. From this perspective, flexibility can be understood more as a measure of variability or reorganization (Granic et al. 2003). In other words, a period of increased variability may be a marker of the reorganization necessary for clinically significant change. This interpretation is consistent with those of psychotherapy researchers who suggest that treatment should trigger a reorganization of affective, cognitive and behavioural systems (e.g., Caspar et al. 1992; Greenberg et al. 1996; Schiepek et al. 1992). The only way to establish whether the IMP group’s interactions reached a stable level of flexibility or whether this phase was temporary is to track parent–child dyads for an extended follow-up period.

The decrease in flexibility (or increases in rigidity) observed in the NIMP group needs some discussion as well. We suspect that this pattern reflects a practice effect. That is, at post-treatment, parents and children have already done the same task before and, for those who have learned little from the intervention program, the second time around finds these dyads coalescing to their entrenched patterns of interaction even faster than the first time. Their rigid styles are therefore even more pronounced. If this is the case, then a decline in flexibility might be the base rate and the increases in flexibility evidenced by the IMPs is even more striking.

Overall, our findings supported our content-specific hypotheses, with an interesting exception. First, results showed that, for both outcome groups, there were no changes from pre- to post-treatment in the duration of time spent in any of the negative regions of the SSG: mother-attack, mutual hostility and permissiveness. As expected, clinical improvements for aggressive children did not translate into parents or children expressing fewer negative emotions during conflict interactions. These results may seem surprising to clinicians who often view their job as eliminating or dramatically decreasing negative affect in family interactions. However, the findings are consistent with basic emotion theories (Izard 1977; Magai and McFadden 1995; Malatesta and Wilson 1988; Tomkins 1963) that propose that negative emotions have important functions in parent–child interactions; their expression does not necessarily lead to pathogenic outcomes. Thus, the reduction or elimination of negative emotional interactions may not be the action mechanism associated with PMT/CBT success.

Contrary to predictions, however, IMP and NIMP groups did differ in terms of changes in their expression of positive emotions during problem-solving sessions. From pre- to post-treatment, IMPs significantly increased the amount of time they spent in the mutual positivity region of the SSG; NIMPs, on the other hand, spent significantly less time in mutual positivity. These results are consistent with previous clinical studies that have linked maternal warmth and sensitivity, positive verbal communication, joint activities of play and conversation and lower levels of aggression (Gardner 1994; Pettit and Bates 1989; Pettit et al. 1993). In non-clinical samples, warm affect reciprocity between parents and children has also been found to relate to greater compliance in children (see Maccoby and Martin 1983, for review).

It is important to note that, before treatment, outcome groups did not differ on the amount of mutual positivity in their interactions. It is not that parents and children who come to treatment with a more affectively warm relationship benefit more from treatment. There may be something about the intervention that promotes increases in mutual positivity. It may be that, as mothers began to implement the new parenting strategies promoted in PMT, children’s behavior began to improve and this, in turn, resulted in both parents and children feeling better in each other’s company. Conversely, reciprocal parent–child warmth and affection may be a cause of improvements in children’s aggressive behavior.

Our last hypothesis focused on dyads’ ability to repair their conflict interactions. As expected, children and parents who benefited from treatment learned to repair their conflicts and flexibly shift to more positive interaction patterns; in contrast, NIMP dyads remained stuck in their negative conflictual patterns. Recall that outcome groups did not differ in their repair capacities at pre-treatment. Thus, the dyadic ability to repair did not predispose children to benefit from PMT/CBT. Instead, our results suggest that another key process of change associated with children’s behavioural improvements is the capacity to repair.

From our perspective, emotional repair can be understood as a form of flexibility. That is, dyads in the IMP group were better able to flexibly shift their emotional patterns to accommodate changes in contextual demands whereas NIMP dyads more often became rigidly stuck in their conflict interactions. In sum, clinically significant improvements through PMT/CBT seem to have little to do with parents and children learning to avoid negative emotional interactions altogether. Instead, dyads acquire the skills to flexibly navigate between negative and positive emotional states and to repair their aversive interactions once they arise.

Implications

Despite the small sample size and limitations of the current research, a number of implications for clinical practice may be suggested, at least tentatively. First, it may be important to explicitly teach parents how to skillfully model and encourage emotional flexibility and repair in their interactions with their children. Parent–child interactions are the main “training ground” through which children learn to express, modulate, and shift out of negative emotions. Therefore, proportionally less emphasis may be placed on the avoidance of angry emotions and more placed on teaching parents and children specific strategies that lead to repair in conflict interactions. Second, an emphasis in PMT on the importance of repair may help parents feel less like “bad” parents when arguments inevitably do arise. Oftentimes, parents express hopelessness and guilt during PMT sessions because they continue to “blow up” at their children. Once mothers become angry and hostile with their children, they feel like they have failed and often they withdraw from their children. Interventions that emphasize the power of repair might ease some of the pressure parents feel to avoid conflicts altogether by introducing a “second chance.”

In addition to implications for clinical practice, the DS methodology applied in this study may be relevant to a wide range of clinical research. The SSG technique encourages us to conceptualize dyadic (or triadic, or individual) behavior as a trajectory through a space of all possible states; thus, patterns that may not have been of primary interest at the start of a study may emerge as potentially important processes. For example, we did not predict the changes in mutual positivity for IMPs, but this change was captured because of the flexible analytic approach. SSGs allowed us to investigate a broad range of dyadic patterns, the structure (i.e., flexibility) of these patterns, and the processes by which they changed over time and context.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are a number of limitations to the current study. First, our sample size was small. To be confident of the change processes we have identified, replication with a larger sample is critical. Second, changes in flexibility and repair capacities were measured concurrently with changes in children’s problem behavior. As a result, we are unable to infer causal status. Increases in parent–child flexibility may provide the context through which children learn to effectively regulate their angry and aggressive impulses. Alternatively, improvements in children’s problem behavior may permit or reflect increases in parent–child flexibility as well as the capacity to repair conflicts. Also, these alternatives are not mutually exclusive. Improvements in children’s behavior may lead to increases in parent–child flexibility which, in turn, may further enhance children’s clinical gains. Third, the decision not to use a randomized control design highlights our constrained focus on individual differences in treatment outcome rather than treatment efficacy more broadly. We cannot be absolutely sure that the observed changes were a result of treatment without the benefit of a control group.

Fourth, fathers could have been included in the study, but this would have necessitated analyzing both dyadic and triadic interactions, or else substituting fathers for mothers in a subgroup of participants, creating excessive complexity. Also, there may be several other key change processes associated with PMT/CBT that were unexamined in this study (e.g., parental discipline, parental psychopathology, marital conflict, and so on). These variables may be important to include in future studies to assess the relative importance of emotional flexibility as compared to other change processes in the prediction of successful outcomes.

Finally, we were unable to collect clinician-reported outcome data on several children and had to rely on parent reports of change, which limits our confidence in how these children were classified. As researchers, we had no control over therapist attrition and delays related to training clinicians to administer the CAFAS. Although the clinical directors were true champions of this research, factors such as cuts to funding and large case-loads often led to research priorities being placed second to clinical services. These limitations are important to note; however, the “real world” context in which this study was conducted is also one of its greater strengths. As far as we know, this study is one of only a few to identify parent–child processes of change associated with successful PMT/CBT outcomes with aggressive children. As such, the present results represent preliminary, but promising new directions for future clinical research.

Notes

To increase incentives to participate in the research, we had initially wanted to pay families more for their participation. However, because this study was conducted in the community, the IRB limited payment considerably in order to minimize the potential coerciveness that a large sum of money would represent to poorer families.

Note that the labeling of cells follows the x/y convention such that the first term represents the child’s code and the second term represents the parent’s code.

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1991a). Manual for the child behavior checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry.

Achenbach, T. M. (1991b). Manual for the child behavior checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile—Teacher version. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry.

Augimeri, L. K., Farrington, D. P., Koegl, C. J., & Day, D. M. (2006). The SNAP Under 12 Outreach Project: Effects of a community based program for children with conduct problems. Journal of Child and Family Studies, online publication first.

Barkley, R. A. (2000). Commentary on the multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28, 595–599.

Bloomquist, M. L., & Schnell, S. V. (2002). Helping children with aggression and conduct problems: Best practices for intervention. New York: Guildford (Xiv, 418 pp.).

Brestan, E. V., & Eyberg, S. M. (1998). Effective psychosocial treatments of conduct disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,272 kids. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 27, 180–189.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. In W. Damon (Ser. Ed.) & R. M. Lerner (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., pp. 993–1028). New York: Wiley.

Caspar, F., Rothenfluh, T., & Segal, Z. (1992). The appeal of connectionism for clinical psychology. Clinical Psychology Review, 12, 719–762.

Cicchetti, D., & Cohen, D. J. (1995). Perspectives on developmental psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti, & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology. Vol 1: Theory and methods (pp. 3–20). New York: Wiley.

Cole, P. M., Martin, S. E., & Dennis, T. A. (2004). Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development, 75, 317–333.

Cole, P. M., Michel, M. K., & Teti, L. O. (1994). The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59, 73–100.

Dumas, J. E. (1989). Treating antisocial behavior in children: Child and family approaches. Clinical Psychology Review, 9, 197–222.

Earlscourt Child and Family Centre (2001a). SNAP™ children’s group manual. Toronto, ON: Earlscourt Child and Family Centre.

Earlscourt Child and Family Centre (2001b). SNAP™ parent group manual. Toronto, ON: Earlscourt Child and Family Centre.

Eddy, J. M., & Chamberlain, P. (2000). Family management and deviant peer association as mediators of the impact of treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 857–863.

Forehand, R. (1986). Parental positive reinforcement with deviant children: Does it make a difference? Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 8, 19–25.

Forgatch, M. S., & DeGarmo, D. S. (1999). Two faces of Janus: Cohesion and conflict. In M. J. Cox, & J. Brooks-Gunn (Eds.), Conflict and cohesion in families: Causes and consequences (pp. 167–184). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Forgatch, M. S., Fetrow, B., & Lathrop, M. (1985). Solving problems in family interactions. Eugene, OR: Oregon Social Learning Center (Training manual).

Gardner, F. E. M. (1994). The quality of joint activity between mothers and their children with behaviour problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35, 935–948.

Goldberg, K. A., & Leggett, E. A. (1990). Earlscourt Child and Family Centre: Under 12 outreach project transformer club group leaders manual. Toronto, ON: Earlscourt Child and Family Centre.

Gottman, J. M., Katz, L. F., & Hooven, C. (1996a). Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: Theoretical models and preliminary data. Journal of Family Psychology, 10, 243–268.

Gottman, J. M., McCoy, K., Coan, J., & Collier, H. (1996b). The specific affect coding system (SPAFF) for observing emotional communication in marital and family interaction. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Gottman, J. M., & Notarius, C. I. (2000). Decade review: Observing marital interaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 927–947.

Granic, I., & Hollenstein, T. (2003). Dynamic systems methods for models of developmental psychopathology. Special issue: Conceptual, methodological, and statistical challenges. Development and Psychopathology, 15, 641–669.

Granic, I., Hollenstein, T., Dishion, T. J., & Patterson, G. R. (2003). Longitudinal analysis of flexibility and reorganization in early adolescence: A dynamic systems study of family interactions. Developmental Psychology, 39, 606–617.

Granic, I., & Lamey, A. K. (2002). Combining dynamic systems and multivariate analyses to compare the mother–child interactions of externalizing subtypes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 265–283.

Greenberg, L. S., Rice, L. N., & Elliott, R. K. (1996). Facilitating emotional change: The moment-by-moment process. New York: Guilford.

Hinshaw, S. P. (2002). Intervention research, theoretical mechanisms and causal processes related to externalizing behavior patterns. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 789–818.

Hodges, K. (1999). Child and adolescent functional assessment scale (CAFAS). In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (2nd ed.) (pp. 631–664). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hodges, K., & Gust, J. (1995). Measures of impairment for children and adolescents. The Journal of Mental Health Administration, 22, 403–413.

Hodges, K., & Wong, M. M. (1996). Psychometric characteristics of a multidimensional measure to assess impairment: The child and adolescent functional assessment scale. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 5, 445–467.

Hodges, K., & Wong, M. M., & Latessa, M. (1998). Use of the child and adolescent functional assessment scale (CAFAS) as an outcome measure in clinical settings. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 25, 325–336.

Hollenstein, T., Granic, I., Stoolmiller, M., & Snyder, J. (2004). Rigidity in parent–child interactions and the development of externalizing and internalizing behavior in early childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 595–607.

Hrynkiw-Augimeri, L., Pepler, D., & Goldberg, K. (1993). An outreach program for children having police contact. Canada’s Mental Health, 41, 7–12.

Huey, S. J., Henggeler, S. W., Brondino, M. J., & Pickrel, S. G. (2000). Mechanisms of change in multisystemic therapy: Reducing delinquent behavior through therapist adherence and improved family and peer functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 451–468.

Izard, C. E. (1977). Human emotions. New York: Plenum.

Kazdin, A. E. (2001). Progression of therapy research and clinical application of treatment require better understanding of the change process. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. Special Issue, 8, 143–151.

Kazdin, A. E. (2002). Psychosocial treatments for conduct disorder in children and adolescents. In P. E. Nathan, & J. M. Gorman (Eds.), A guide to treatments that work: 2nd ed. (pp. 57–85). London: Oxford University Press.

Kazdin, A. E., & Nock, M. K. (2003). Delineating mechanisms of change in child and adolescent therapy: Methodological issues and research recommendations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 1116–1129.

Kazdin, A. E., Siegel, T., Bass, D. (1992). Cognitive problem-solving skills training and parent management training in the treatment of antisocial behavior in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 733–747.

Lewis, M. D. (2000). The promise of dynamic systems approaches for an integrated account of human development. Child Development, 71, 36–43 (Special issue on New Directions for Child Development in the Twenty-first Century).

Lewis, M. D., Lamey, A. V., & Douglas, L. (1999). A new dynamic systems method for the analysis of early socioemotional development. Developmental Science, 2, 458–476.

Lochman, J. E., & Wells, K. C. (2004). The coping power program for preadolescent aggressive boys and their parents: outcome effects at the 1-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 571–578.

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent–child interaction. In P. H. Mussen (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology, Volume IV: Socialization, personality, and social development (pp. 1–101). New York: Wiley.

Magai, C., & McFadden, S. H. (1995). The role of emotions in social and personality development: History, theory, and research. New York: Plenum Press.

Malatesta, C., & Wilson, A. (1988). Emotion/cognition interaction in personality development: A discrete emotions, functionalist analysis. British Journal of Social Psychiatry, 27, 91–112.

Martinez, C. R. Jr., & Forgatch, M. S. (2001). Preventing problems with boys’ noncompliance: Effects of a parent training intervention for divorcing mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 416–428.

National Advisory Mental Health Council (NAMHC). (1999). Bridging science and service (NIH publication no. 99-4353). Washington, DC: NIH.

National Advisory Mental Health Council’s Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment (NAMCH-W). (2001). Blueprint for change: Research on child and adolescent mental health. Washington, DC: NIH

Patterson, G. R., Chamberlain, P., & Reid, J. B. (1982). A comparative evaluation of parent training procedures. Behavior Therapy, 13, 638–650.

Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (1989). Family interaction patterns and children’s behaviour problems from infancy to 4 years. Developmental Psychology, 25, 413–420.

Pettit, G. S., Bates, J. E., & Dodge, K. A. (1993). Family interaction patterns and children’s conduct problems at home and school: A longitudinal perspective. School Psychology Review, 22, 403–420.

Richters, J. E. (1997). The Hubble hypothesis and the developmentalist’s dilemma. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 193–229.

Robin, A. L., & Weiss, J. G. (1980). Citerion-related validity of behavioral and self-report measures of problem-solving communication skills in distressed and non-distressed parent–adolescent dyads. Behavioral Assessment, 2, 339–352.

Schiepek, G., Fricke, B., & Kaimer, P. (1992). Synergetics of psychotherapy. In W. Tschacher, G. Schiepek, & E. J. Brunner (Eds.), Self-organization and clinical psychology (pp. 239–267). Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Snyder, J. J., & Stoolmiller, M. (2002). Reinforcement and coercion mechanism in the development of antisocial behavior: The family. In J. B. Reid, G. R. Patterson, & J. Snyder (Eds.), Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention (pp. 65–100). Washington, DC: APA.

Southam-Gerow, M. A., & Kendall, P. C. (2002). Emotion regulation and understanding implications for child psychopathology and therapy. Clinical Psychology Review, 22, 189–222.

Tomkins, S. S. (1963). Affect, imagery, consciousness: Vol. II. The negative affects. New York: Springer.

Tremblay, R. E., Pagani-Kurtz, L., Masse, L. C., Vitaro, F., & Pihl, R. O. (1995). A bimodal preventative intervention for disruptive kindergarten boys: its impact through mid-adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 560–568.

Webster-Stratton, C., & Hammond, M. (1997). Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: A comparison of child and parent training interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 93–109.

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of Grant 1 R21 MH 67357 from the National Institute of Mental Health and Grant MOP-62930 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. We are also deeply indebted to the clinical directors and clinicians at the community mental health agencies that partnered with us; they championed this research and helped us realize our collective goal of bridging theory, research and practice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Granic, I., O’Hara, A., Pepler, D. et al. A Dynamic Systems Analysis of Parent–child Changes Associated with Successful “Real-world” Interventions for Aggressive Children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 35, 845–857 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9133-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9133-4