In a sample of 299 children (grades 2, 4, and 6), we examined parenting and negative life events as predictors of depressive cognitions, specifically low self-perceived competence, depressive cognitive schemas, and depressogenic attributional style. We also examined developmental trends in these relations. Children completed measures of parenting, negative life events, and depressive cognitions. Parents also completed measures of parenting and negative life events. Consistent with our hypotheses, negative parenting and negative life events corresponded with higher levels of depressive cognitions, whereas positive parenting corresponded with lower levels of depressive cognitions. The relations between negative parenting and negative automatic thoughts were stronger for older children. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Many studies suggest that the origins of depression in children consist of certain cognitive diatheses. The current study examines the developmental origins of these cognitive diatheses. Among these cognitive diatheses are such factors as low self-perceived competence (Cole, 1990), depressive cognitive schemas (Beck, 1963, 1972), and depressogenic attributional style (Abramson, Alloy, & Metalsky, 1988; Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978). People who have low levels of self-perceived competence, who maintain negative beliefs about the self, world, and future (negative cognitive triad), and who make more internal, stable, and global attributions for the causes of negative events in their lives are at higher risk for the development of depression (e.g., Cole, Martin, Peeke, Seroczynski, & Hoffman, 1998; Cole, Martin, & Powers, 1997; Hilsman & Garber, 1995; Robinson, Garber, & Hilsman, 1995; Seroczynski, Cole, & Maxwell, 1997). Although research has implicated these cognitive variables as risk factors for depression, only a few studies have explored their developmental origins. Exploring the development of low self-perceived competence, depressive cognitive schemas, and a depressogenic attributional style, is an important next step in understanding the etiology of depression.

For the most part, depression theorists have only vaguely alluded to childhood as a time when the cognitive diatheses for depression develop. Childhood has been identified as an important time for the development of positive (and negative) competency beliefs about the self (Cole, 1990, 1991; Harter, 1982, 1985, 1988), beliefs that protect against (or predispose to) depression. In his cognitive model of depression, Beck (1963, 1972) suggested that real or perceived losses during childhood play a role in the development of negative schemas, which in turn facilitate the storage and processing of information in a dysfunctional manner. In their hopelessness theory of depression, Abramson and colleagues recognized the need to identify the developmental origins of depressogenic attributional style (Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989). Their more recent work suggests that various negative parenting practices may be important factors in the emergence of depressive attributions (Alloy et al., 2004; Alloy et al., 2001; Gibb et al., 2001).

Problematic parenting and negative life events during childhood are two important factors that may foment the development of cognitive diatheses for depression. Developmental theories support this contention in that parents provide a context in which children learn about themselves, their abilities, and the world around them. Beck and Young (1985) suggested that a “child learns to construct reality through his or her early experiences with the environment, especially with significant others. Sometimes, these early experiences lead children to accept attitudes and beliefs that will later prove maladaptive” (p. 207). From a cognitive-developmental perspective, parenting consists of a collection of patterned behaviors that convey information to the child, which may then be internalized by the child during self-concept development. Parenting characterized by warmth, acceptance, allowance of autonomy, and high levels of positive reinforcement provides children with positive experiences and feedback that engenders the development of positive views of self and the world. In contrast, parenting characterized by criticism, rejection, control, and low levels of warmth and positive reinforcement conveys negative self-relevant information, thereby engendering more depressogenic views (Cole, 1990; McCranie & Bass, 1984; see also Ainsworth, 1979; Bowlby, 1980, 1988). Negative life events also convey information pertinent to the development of cognitive diatheses for depression. Janoff-Bulman (1992) and Rose and Abramson (1992) suggested that people's views about themselves, the world, and the future are influenced by the experience of chronically aversive life circumstances and major traumatic life events. Abramson and colleagues (1989) suggested that the likelihood of developing depressogenic cognitions such as helplessness and hopelessness are even greater when the events are uncontrollable and result in multiple bad outcomes. Cole and Turner (1993) reminded us it is normative for young children to assume blame for negative life events, thereby constructing self-relevant information out of hardships for which they may have not had any real responsibility.

Preliminary empirical evidence supports the idea that parenting and negative life events may affect various cognitive diatheses for the development of depression. One set of studies described the relation between parenting and self-concept. High levels of parental acceptance, care, and autonomy granting were associated with a more positive self-concept in children, whereas high levels of parental rejection, restrictiveness, and inconsistent love were associated with a more negative self-concept (e.g., Jaenicke et al., 1987; Litovsky & Dusek, 1985; Liu, 2003). A second set of studies examined the relation between parenting and depressive cognitive schemas. High levels of parental control, indifference, and criticism, plus low levels of care and acceptance, were related to cognitive errors and dysfunctional attitudes in youth (e.g., Alloy et al., 2001; Garber & Flynn, 2001; Liu, 2003). A third set of studies described the relation of parenting to attributional style. Low levels of parental care and acceptance and high levels of criticism and control correlated with the emergence of an internal-stable-global attributional style in children (e.g., Alloy et al., 2001; Garber & Flynn, 2001; Jaenicke et al., 1987).

Other research has examined the relation between negative life events and cognitive diatheses for depression. Some studies document the relation between negative life events and poor self-perceptions (e.g., Fenzel, 2000; Garber & Flynn, 2001; Haine, Ayers, Sandler, Wolchik, & Weyer, 2003; Kliewer & Sandler, 1992; Lengua, Wolchik, & Braver, 1995; Wyman, Cowen, Hightower, & Pedro-Carroll, 1985). Other studies suggest that negative life events are associated with cognitive errors and negative views of self, world, and future (e.g., Cole & Turner, 1993; Garber & Flynn, 2001; Mazur, Wolchik, Virdin, Sandler, & West, 1999). Finally, several studies have examined the relation between negative life events and a dysfunctional attributional style. Children who are exposed to more frequent or more serious negative life events tend to make internal, stable, global attributions (e.g., Cole & Turner, 1993; Garber & Flynn, 2001; Nolen-Hoeksema, Girgus, & Seligman, 1992).

In general, research supports our contention that parenting and negative life events help to generate the various cognitive diatheses to depression. Nevertheless, a number of methodological limitations of these studies need to be considered. In many of these studies, the predictor and the dependent variable derived from the same informant. To the degree that measures share some degree of method variance, their correlation may overestimate the actual relation between the constructs of interest. Also common are data analytic strategies that focus on only one predictor variable at a time. Individually, these studies permit a relatively narrow examination of the relation of negative parenting, positive parenting, or negative life events to depressive cognitions and limit the ability to assess the combined and unique effects of these predictors. Examining parenting and life events together represents an important next step toward understanding the emergence of depressive cognitions.

Finally, the majority of the studies either focused on a relatively narrow age range or collapsed across a wide range of ages for data analyses. Such studies cannot test the possibility that the effects of parenting and negative life events vary with age. Developmental theories suggest that these effects may increase with development. Harter (1990) theorized that as children move through middle childhood they become more aware of the evaluations of others. During this transition they also begin to describe themselves in terms of more global, trait-like characteristics (Harter, 1986). As children grow older, they become more aware of parental evaluations and begin to integrate these evaluations into more global and stable views of themselves. From another perspective, young children tend to be globally positive about themselves and their abilities (Crain, 1996). Therefore, it may take more profoundly negative parenting or more serious negative life events to override this tendency early in middle childhood as compared to later. From a third perspective, we know that it simply takes time for parenting and negative life events to affect children. Children are remarkably resilient to the effects of discrete hardships (Masten, 2001; Masten, Best, & Garmezy, 1990). When stress is persistent and chronic, however, it may have more adverse effects. Therefore, the impact of such stressors on depressive cognitions may be more evident as children grow older.

The current study examines the relations of parenting and negative life events to three major types of depressive cognitions: low self-perceived competence, depressive cognitive schemas, and depressogenic attributional style. We designed the study to extend the existing literature in several ways. First, we used both parent- and child-report methods to assess parenting and negative life events. In this way we sought to confirm one set of results with those using qualitatively different sources of information. Second, by collecting data on negative parenting, positive parenting, and negative life events in the same study, we are able to examine the combined and unique contributions of each to the prediction of depressive cognitions. Finally, we collected data from children in three different grade levels (second, fourth, and sixth grade). Many of the cognitive changes that may affect the relation of parenting and negative life events to depressive cognitions are prominent during this time (e.g., Crain, 1996; Harter, 1986, 1990; Masten, 2001; Masten et al., 1990). We hypothesized that the relation of parenting and negative life events to depressive cognitions would increase with grade level.

METHOD

Participants

We recruited participants from five elementary and two middle schools in a midsize southern city at the beginning of the 2002–2003 academic year. We distributed consent forms to parents of 1040 students in second, fourth, and sixth grade. Consent forms were returned by 660 parents, with 526 parents agreeing to let their child participate. Eleven of the students for whom we had consent did not participate as a result of moving out of the school district or chronic absenteeism. We also requested the participation of the children's parents or guardians. In total, 299 parents returned questionnaires. In the current study, we examined only those cases in which we have both child- and parent-report data. We examined the census data for the school districts in which we collected data and confirmed that the sample for whom we received parental consent was representative of this larger population on several demographic variables (e.g., income, employment, ethnicity). Additionally, we compared the children for whom we had parent-return data to those for whom we did not. This comparison revealed that these children did not differ on any of the child-reported predictor or outcome variables.

Children were in second (N=91), fourth (N=104), and sixth (N=104) grades and their ages ranged from 6 to 13 years (M=9.50, SD=1.67). The sample included 43% male and 57% female participants. The sample was diverse, with 63.5% African-American, 31.5% Caucasian, 1% Latino, 1.5% Asian American, less than 1% Native-American, and 2% “other” or “mixed” participants. Parents identified their ethnic backgrounds as follows: 63.5% African-American; 30% Caucasian; 1.5% Latino; 1.5% Asian-American; 1% Native-American; and 2.5% “other” or “mixed.” In 86% of the cases, the mother of the child completed the questionnaires. The remainder were completed by grandmothers (7%), fathers (4.5%), stepmothers (<1%), and other relatives or guardians (2%). The majority of respondents (60%) reported not being currently married. Parents’ educational backgrounds were as follows: 27.5% less than high school education; 27% high school education; 35% some posthigh school education; 6% bachelor's degree; and 4.5% some postcollege education. Average family income in this sample was approximately $19,000.

Measures

Parenting

We used both child- and parent-report measures of parenting. Children completed the Parent Perception Inventory (PPI), a questionnaire based upon Hazzard, Christensen, and Margolin's (1983) Parent Perception Interview. The original interview inquired about children's perceptions of 18 parental behaviors (9 positive and 9 negative). We converted these 18 behaviors into a 36-item self-report questionnaire by generating two items designed to measure each of the 18 behaviors. Children rate how often their mother or primary caregiver engages in particular behaviors on 5-point scales (1: not at all to 5: all the time). The original interview provided a two-factor solution that Hazzard and colleagues labeled positive and negative parenting behavior. Our own factor analysis of the PPI questionnaire with the current sample also resulted in a two-factor solution. Representative positive parenting items were “How often does this person say something nice about you?” and “How often does this person help you with a problem?” Representative negative parenting items were “How often does this person yell at you?” and “How often does this person nag you or tell you what to do over and over again?” Two items did not load onto either the positive or negative parenting factor and were therefore excluded from any analyses. This resulted in a 34-item self-report questionnaire, with 18 items tapping children's perceptions of positive parenting behaviors and 16 items tapping children's perceptions of negative parenting behaviors. With these exclusions, potential scores on the positive parenting scale range from 18 to 90 with higher scores representing more positive parenting. Potential scores on the negative parenting scale range from 16 to 80 with higher scores representing more negative parenting. Two independent studies revealed the original PPI to have good internal consistency in samples of children ranging in age from 5 to 13 (Glaser, Horne, & Myers, 1995; Hazzard et al., 1983). An examination of our modified PPI using the current data set revealed good internal consistency at all three grade levels. For positive parenting, Cronbach's alphas were .78, .76, and .84; for negative parenting, alphas were .78, .82, and .82 in grade 2, 4, and 6, respectively.

Parents completed the Parent Behavior Inventory (PBI; Lovejoy, Weis, O’Hare, & Rubin, 1999). The PBI is a 20-item self-report questionnaire in which parents rate the frequency of a variety of parenting behaviors using 6-point scales (0: never true to 5: almost always true). Based on a confirmatory factor analysis of this measure, Lovejoy and colleagues suggested that the measure contained two factors: supportive/engaged parenting and hostile/coercive parenting. Our own factor analysis using the current sample replicated this factor structure. Items representing the supportive/engaged factor included, “I listen to my child's feelings and try to understand them” and “I thank or praise my child.” Items representing the hostile/coercive parenting factor included, “I lose my temper when my child doesn't do something I ask him/her to do” and “I threaten my child.” Three items either had very weak factor loadings or very high cross-loadings. These items were excluded from analyses resulting in a supportive/engaged factor comprised of 10 items and a hostile/coercive factor comprised of 7 items. With these exclusions, potential scores on the supportive/engaged scale range from 0 to 50 with higher scores representing higher levels of supportive/engaged parenting. Potential scores on the hostile/coercive scale range from 0 to 35 with higher scores representing higher levels of hostile/coercive parenting. Lovejoy and colleagues reported good internal consistency for the two factors in a sample of young children (Cronbach's alpha = .83 for supportive/engaged factor and .81 for the hostile/coercive factor). In our sample, reliabilities for both subscales were also adequate at all three grade levels. For supportive/engaged parenting, alphas were .87, .84, and .84; for hostile/coercive parenting, alphas were .69, .63, and .55 in grade 2, 4, and 6, respectively.

Negative Life Events

We used both a child- and parent-report version of a life events checklist (LEC) consisting of 30 negative life events (e.g., “Your family had to move a lot” and “A close family member was arrested or in jail”). Items on this checklist range from medium to major live events. Minor events (or daily hassles) are not included. Respondents indicate whether or not the child has been exposed to each of the events in the past 6 months using a yes/no format. We chose this life events measure because it was developed for inner city, low SES youth, and contained a high concentration of relevant items given the demographics of our sample. The specific items and the yes/no response format are the same as a life events checklist created by Work, Cowen, Parker, and Wyman (1990). We added an additional component to the checklist such that if the respondent endorsed an item, they were asked how upsetting the event was for the child using a 3-point scale (1: not much to 3: very much). By adding the upset score, we hoped to capture the degree to which different events impact children's lives. However, to avoid individual bias in these upset ratings, we calculated a mean upset rating (nomothetic weight) for each event using data from the entire sample. We used these nomothetic weights in our analyses, such that if an individual reported that a specific event happened to them, their score for that event was equal to the mean upset score for the group. Potential scores range from 0 to 90 with higher scores reflecting large numbers of more upsetting events.

Self-Perceived Competence

We used developmentally appropriate measures of personal competencies for use with different ages. With second grade students we used the Pictorial Scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance for Young Children (Harter & Pike, 1984). This self-report inventory consists of 24 items measuring four domains (cognitive competence, physical competence, peer acceptance, and maternal acceptance). For each item, children are presented with two pictures and read two sentences describing two different children (e.g., “This child isn't very good at numbers” and “This child is pretty good at numbers”). First, they indicate which child is most like themselves. Then they refine their choice further by selecting from two more specific choices (e.g., if the child says that they are pretty good at numbers they indicate if they are “pretty good” or “really good at numbers”). With fourth and sixth grade students we used Harter's (1985) Self-Perception Profile for Children. This self-report inventory contains 36 items measuring five domains of self-perceived competence (academic competence, social acceptance, athletic competence, physical appearance, and behavioral conduct) and global self-worth. For each item, children select one of two statements to indicate whether they are more like a child who is good or a child who is poor at a particular activity. Then they select statements indicating whether the selected statement is “sort of true” or “really true” about them. For both measures, items are scored on a 4-point rating scale such that high scores reflect greater self-perceived competence. Both instruments show a highly interpretable factor structure and their subscales have good internal consistency. In the current sample of second graders, Cronbach's alpha was .82 for the Pictorial Scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance for Young Children. In the current sample of fourth and sixth graders, Cronbach's alphas were .89 and .93 for the Self-Perception Profile for Children.

The self-perceived competence (SPC) variable used in the current study consisted of either the sum of the four domains on the Pictorial Scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance for Young Children (for second graders) or the sum of the five domains (excluding global self-worth) on the Self-Perception Profile for Children (for fourth and sixth graders). The scores were standardized within each group.

Depressive Cognitions

We used the Children's Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (CATQ; Hollon & Kendall, 1980) and the Cognitive Triad Interview for Children (CTI-C; Kaslow, Stark, Printz, Livingston, & Tsai, 1992) to measure children's depressive cognitive schemas. The CATQ is a 30-item questionnaire that assesses negative automatic thoughts. Children are asked to rate how often, in the past week, they have had specific negative thoughts, using 5-point scales (1: not at all to 5: all the time). Scores range from 30 to 150 with higher scores representing higher levels of negative automatic thoughts. This measure showed good internal consistency in a sample of child psychiatric inpatients (Cronbach's α=.96; Kazdin, 1990). In the current sample reliabilities were .90, .93, and .95 in grade 2, 4, and 6, respectively.

The CTI-C is a 36-item self-report questionnaire assessing children's views of themselves (e.g., “I am a failure”), their world (e.g., “The world is a very mean place”), and their future (e.g., “Nothing is likely to work out for me”). Children indicate having had specific thoughts, using a yes/maybe/no response format. Scores range from 0 to 72 with higher scores representing more negative views. The CTI-C has been shown to have acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach's α=.92 for full scale and range from .69 to .92 for subscales; Kaslow et al., 1992). In the current sample, Cronbach's alpha for the full scale was .94, .94, and .93 in grade 2, 4, and 6, respectively.

Attributional Style

We obtained information about children's attributions using the Children's Attributional Style Interview (CASI; Conley, Haines, Hilt, & Metalsky, 2001). The original version of the CASI included 8 positive and 8 negative items; however, we used only the negative items. Each item presents a hypothetical situation and an accompanying picture. Children are asked to imagine themselves in the situation and provide the one main reason that the situation happened to them. Children then rate their causal attribution on three 7-point scales: internality (how much their causal reason was “because of you”), stability (if their reason “would be true again”), and globality (if their reason would “make other bad things happen”). Total scores range from 24 to 169 with higher scores representing a more depressogenic attributional style. A validation study of this measure in a group of children (age range 5 to 10) revealed good subscale internal consistency (Cronbach's alphas range from .72 to .82; Conley et al., 2001). Cronbach's alpha for the 8 negative items used in the current sample was .81, .83, and .83 in grade 2, 4, and 6, respectively.

Procedure

Doctoral psychology students and advanced undergraduates received extensive training on all of the measures prior to data collection. We collected data in two separate 1-hr sessions scheduled during the regular school day within 1 month of each other. We counterbalanced questionnaires within each session. For students in second grade, we administered both Session 1 and Session 2 questionnaires individually. For students in fourth grade, we administered Session 1 questionnaires individually and Session 2 questionnaires in small groups (approximately 2 to 3 students each). For students in sixth grade, we administered both sessions to larger groups. For these larger group administrations, one research assistant read the questionnaires aloud, requiring all students to proceed at the same pace. Two or three additional research assistants circulated among the students ensuring correct completion of the items and answering questions as they arose. At the completion of each session, students received a candy bar and a decorative pencil as tokens of appreciation. In cases where children were absent from school for one or both of the sessions, we scheduled makeup sessions during the regular school hours.

To parents, we mailed questionnaires along with self-addressed stamped envelopes. We sent $15 to parents who returned completed questionnaires. We made follow-up calls to parents who did not return the questionnaires promptly.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics for all variables appear in Table I. Means on the cognitive outcome variables for the current sample are slightly higher than those for other nonreferred samples (Conley et al., 2001; Kazdin, 1990; Stark, Schmidt, & Joiner, 1996), perhaps because of the higher stress levels sometimes associated with lower socioeconomic samples. Correlations between all of the variables are also provided in Table I.

Canonical Correlations

In order to examine the combined effects of sex, grade, negative parenting, positive parenting, and negative life events on all four types of negative cognition, we performed two canonical correlation analyses. One was a within-source analysis, in which child-reported outcomes were regressed onto child-reported predictors. The second was an across-source analysis, in which child-reported outcomes were regressed onto parent-reported predictors. We included sex in the model as there is evidence to suggest that gender differences exist in some of the cognitive variables included in this study (e.g., Cole, Martin, Peeke, Seroczynski, & Fier, 1999; Cole et al., 2001; Nolen-Hoeksema, Girgus, & Seligman, 1991).

In the within-source canonical correlation, we regressed the four cognitive variables (SPC, CATQ, CTI, and CASI) onto sex, grade, and child-reported negative parenting, positive parenting, and negative life events. Interactions of grade with negative parenting, positive parenting, and negative life events were also examined.Footnote 1 The first canonical root was large and significant (R=.58, p < .01). (The second, third, and fourth roots were also significant, in part because of the relatively large N. However, their effect sizes were relatively small.). Examination of the standardized canonical weights revealed that female gender, lower grade, and higher levels of negative parenting and negative life events predicted higher levels of depressive cognitions (see Table II). The negative parenting×grade interaction was marginally significant (p=.05).

In the across-source canonical correlation, we regressed the four cognitive variables (SPC, CATQ, CTI, and CASI) onto sex, grade, and parent-reported negative parenting, positive parenting, and negative life events. The same interactions with grade were also examined. The first canonical root was large and significant (R=.42, p < .01). (Additional roots were also significant, albeit small). Examination of the standardized canonical weights revealed that lower grade and higher levels of negative parenting predicted higher levels of depressive cognitions. There was also a significant positive parenting×grade interaction (see Table II).

Multiple Regressions

We followed up both of the significant canonical correlations with a series of multiple regressions. In separate regressions, each of the four outcome variables was regressed onto the same set of predictors used in the canonical analyses, once using child-reports of negative parenting, positive parenting, and negative life events, and once using parent-reports of these variables. We assumed the family-wise alpha to be protected by the significant canonical tests.

Predicting Self-Perceived Competence

In the regression of self-perceived competence onto child-reported predictors, the main effects for sex, positive parenting, and negative life events were all significant. Female gender, lower levels of positive parenting, and higher levels of negative life events were associated with lower levels of self-perceived competence (see Table III). No significant interactions emerged. In the regression of self-perceived competence onto parent-reported predictors, no main effects or interactions were significant.

Predicting Automatic Thoughts

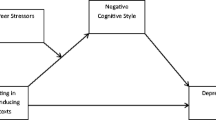

When the predictors were measured by child-report instruments, the main effects for sex, grade, negative parenting, and negative life events were significant. Female gender, lower grade, and higher levels of negative parenting and negative life events were associated with higher levels of negative automatic thoughts. A negative parenting×grade interaction also emerged such that the effects of negative parenting on negative automatic thoughts increased with grade (see Table IV and Fig. 1). When the predictors were represented by parent-report measures, the main effects for grade and negative parenting were significant and in the same direction as for the child-report measures (see Table IV). The interactions involving parent-reported variables were not significant.

Predicting Cognitive Triad

In the regression of the cognitive triad onto child-reported predictors, the main effects for grade, positive parenting, and negative life events were significant. Lower grade, lower levels of positive parenting, and higher levels of negative life events were associated with higher levels of negative thoughts about the self, world and future (see Table V). No significant interactions emerged. When parent-reported measures served as the predictors, the main effect for grade was significant (see Table V). The direction of the effect replicated the results for child-reported measures.

Predicting Attributional Style

When depressive attributional style was regressed onto child-report measures, the main effect for negative parenting was significant. Higher levels of negative parenting were associated with a more depressive attributional style (see Table VI). No significant interactions emerged. When parent-report measures served as the predictor, the main effect for positive parenting was significant, such that lower levels of positive parenting were associated with a more depressive attributional style (see Table VI).

DISCUSSION

The major findings that emerged from this study pertained to the relation of four types of depressive cognitions to parenting and negative life events. Self-perceived competence, negative automatic thoughts, the negative cognitive triad, and depressive attributional style were related to child and/or parent reports of negative parenting, positive parenting, and negative life events. The strength and significance of these relations varied, however, as a function of the informant, the type of depressive cognition, and (to some extent) the age of the child.

First, bivariate correlations revealed that children's self-perceived competence was positively related to positive parenting and negatively related to negative parenting and child-reported negative life events. Examining the unique effects of these predictors using multiple regression, we found that only child-reported positive parenting and negative life events related to children's self-perceived competence. Higher levels of positive parenting and lower rates of negative life events were associated with higher levels of self-perceived competence. These results are consistent with several previous studies (e.g., Fenzel, 2000; Garber & Flynn, 2001; Jaenicke et al., 1987; Kliewer & Sandler, 1992; Liu, 2003; Wyman et al., 1985).

Second, children's negative automatic thoughts were positively correlated with negative parenting and child-reported negative life events. Examination of the unique effects revealed the same pattern of results. Children who experienced higher levels of negative parenting and children who reported higher levels of negative events were more likely to report having negative automatic thoughts. Furthermore, the relation of automatic thoughts to child-reported negative parenting was stronger for older children. Other studies have reported a relation between parenting and negative cognitive schemas (e.g., Alloy et al., 2001; Liu, 2003), but evidence of age-related increases in this relation have not previously been examined.

Third, children's negative cognitive triad (i.e., negative thoughts about self, world, and future) was significantly correlated with negative life events, negative parenting, and child-reported positive parenting. Unique effects emerged for child-reported positive parenting and negative life events, after controlling for other variables. Reporting lower levels of positive parenting and higher levels of negative life events was associated with higher levels of negative thoughts about self, world, and future, in a manner consistent with previous research (Alloy et al., 2001; Cole & Turner, 1993; Garber & Flynn, 2001; Liu, 2003; Mazur et al., 1999).

Fourth, children's depressive attributional style was positively correlated with child-reported negative parenting and negative events. Attributional style was negatively correlated with parent-reported positive parenting. Unique effects emerged only for the two parenting variables. Children with more depressive attributional styles reported more negative parenting, and their parents reported lower levels of positive parenting. These effects are similar to those reported in several previous studies (e.g., Alloy et al., 2001; Garber & Flynn, 2001; Jaenicke et al., 1987).

We speculate upon causal relations that might underlie the observed correlation between negative life events and various depressive cognitions. Negative events likely convey negative self-relevant information to the child that becomes incorporated into their views of self, the world, and the future. On the one hand, certain negative life events (e.g., losing a friend, failing a test) may actually be the result of the child's behavior. On the other hand, children often assume blame for events that, in reality, are not their responsibility. In either case, the child walks away from the event with negative self-relevant information. If such events are chronic, children may, over time, learn that they are helpless to prevent them. As they incorporate their experiences in the present into their predictions about the future, children may become increasingly hopeless. The experiences of major trauma and chronic negative life events may be especially likely to impact children's views of the self, world, and future (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Rose & Abramson, 1992).

We also speculate upon two possible causal mechanisms that might underlie the correlation between parenting and children's development of depressive cognitions. One such mechanism is internalization. To a young child, parental feedback contains important self-relevant information. As children engage in the developmental task of self-concept construction, the information conveyed by parents constitutes some of the building material. Children come to think of themselves in a manner congruent with the way that they perceive others regard them (Cooley, 1902; Mead, 1934). The internalization of negative parental feedback will engender negative self-concept, whereas the internalization of positive parental feedback may inhibit the development of negative self-cognitions. Additionally, children construct their views of reality based on their early experiences with the environment (Beck & Young, 1985). Children incorporate experiences in the home environment into their views of the world and their expectations for the future. Children who experience high levels of negative parenting may begin to expect others in the world to treat them in a similarly negative way, whereas children who experience high levels of positive parenting will expect more positive treatment from others.

The apparent moderating effect of age (or grade level) may be due to at least two processes for which age serves as a proxy. One is children's “fall from grace” during the early elementary school years. Younger children tend to maintain unrealistically global positive views of themselves and the world around them (Crain, 1996; Harter, 1988). Over the course of middle childhood, children's conceptions become more realistic and, almost inevitably, less sanguine. During this time, children incorporate information from their environment into their developing views. This information naturally includes feedback from parents. Children who experience unmitigated negative parental feedback may drop further during what is otherwise a relatively normative fall from grace. A second potential explanation relates to the likelihood that older children have been exposed to parenting for a longer period of time. The repetition or chronicity of negative parenting, which likely correlates with age, may be the actual moderator of the relation between negative parenting and depressive automatic thoughts.

We found sex differences in self-perceived competence and negative automatic thoughts with girls reporting lower levels of perceived competence and higher levels of negative automatic thoughts. These findings are consistent with work examining gender differences in children's over- and underestimation of their abilities. Cole and colleagues (1999) found that in middle childhood, girls tend to underestimate their abilities whereas boys tend to overestimate them. An examination of the items on the automatic thoughts questionnaire revealed that it is highly saturated with competence related items (e.g., I can't do anything well and I can't finish anything). Sex differences on this measure may reflect the previously observed sex difference in self-perceived competence. Cole et al. suggested that this difference may be related to gender differences in depression and anxiety. Gender differences in depression do not emerge until seventh grade (Rutter, 1988) and therefore would not be expected to account for gender differences in perceived competence in the current sample. However, gender differences in anxiety are apparent even in kindergarten (Cohen et al., 1993) and therefore may account for some of the observed differences in self-perceptions of competence.

As expected, many of the findings of this study were stronger for child-reports of parenting and negative life events (within-informant analyses) than for parent-reports (across-informant analyses). Often this discrepancy is attributed to the shared-method variance that may contribute to the relation between two measures completed by the same informant (Cole, in press). However, other explanations are also possible (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). For example, parent and child appraisals of parenting and negative life events may tap qualitatively different constructs. The construct measured by child-reports may be more related to depressive cognitions. The construct measured by parent-reports may reflect parental mood and perhaps parental tendency to cast themselves in a positive light.

The current study makes several unique contributions to the existing literature. First, the sample was comprised of a high proportion of minority children, including many from relatively low-income families and many who live in single parent homes. Most previous work on depressive cognitions in children has relied on white, middle class families (e.g., Fenzel, 2000; Jaenicke et al., 1987). Interestingly, the findings of this study are consistent with the existing literature, suggesting that theories about depressive cognitions, though often supported by data from white, middle class samples, are equally relevant for minority populations. A second contribution of this study is the examination of parenting and negative life events in the same analyses. Most existing studies examine either parenting or negative life events as predictors of depressive cognitions, limiting the ability to assess the combined and unique effects of these predictors. In the current study, we found that parenting and negative life events do make independent contributions to the prediction of several depressive cognitions. Finally, this study is unique in its examination of age-related changes in the relations of parenting and negative life events to depressive cognitions. Although developmental theories suggest that these effects may increase with development, we found minimal support for this hypothesis.

Several shortcomings of the current study suggest avenues for future research. First, the current data were cross-sectional. A longitudinal examination of these relations would strengthen the argument that parenting and negative life events are causally linked to the emergence of depressive cognitions in children. Additionally, a longitudinal design would allow for an assessment of whether the observed developmental trend also occurs intra-individually. Second, including children from a wider age range would allow an examination of developmental shifts that may occur prior to second grade or after sixth grade. In the current sample, we only observed a developmental trend in the effects of negative parenting on negative automatic thoughts. Similar trends could emerge for self-perceived competence, cognitive triad, and attributional style at younger or older ages. Third, we have focused on only four putative cognitive diatheses for depression. The developmental precursors of other such diatheses, including those suggested in hopelessness theory (Abramson et al., 1989) warrant investigation in future studies. Fourth, we used two broad parenting constructs, negative and positive parenting. A more fine-grained analysis of parenting could allow for the determination of specific parenting behaviors, or specific combinations of behaviors, that are particularly predictive of depressive cognitions in children. Fifth, we did not include a measure of parental depression in the current study. Parental depression is clearly related to parenting, stressful life events, and child depression (e.g., Goodman & Gotlib, 2002) and may constitute a potential “third variable” in studies of children's depressive cognitions as well.

Additional avenues for future research relate to the choice of life events measure in the current study. Although our life events measure was selected for its relevance to low socio-economic urban children, it did not distinguish between subtypes of negative events. Distinguishing between dependent versus independent events, major versus minor events, chronic versus episodic events, or affiliation versus achievement events may reveal important moderator variables. Also, an examination of the role of more specific life events (e.g., divorce, abuse), as opposed to a more global stress score, could be useful in selected populations. Finally, the best measures of life events are protracted semistructured interviews, which take a more objective and contextual approach (e.g., Brewin, Andrews, & Gotlib, 1993; Katschnig, 1986; McQuaid, Monroe, Roberts, Kupfer, & Frank, 2000). One of the major advantages of these methods is that they are less affected than questionnaire assessments by the effects of mood on memory (e.g., Brewin et al., 1993; Monroe & Depue, 1991). Time constraints prevented the use of such measures in the current study.

The current study has clinical implications for the development of prevention and early intervention programs. Previous research provides evidence that negative cognitions are strong predictors of later depression (Cole & Turner, 1993; Kaslow et al., 1992; Kazdin, 1990; Liu, 2003; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1992; Stark, Schmidt, & Joiner, 1996). The identification of children who exhibit high levels of depressive cognitions will allow for implementation of interventions prior to the development of depression. Additionally, the identification of children exposed to risk factors for depressive cognitions may allow for even earlier intervention. The current study suggests that problematic parenting and negative life events are two such factors. The observed additive effect suggests that children exposed to both problematic parenting and negative life events are at a particularly high risk and should be targeted for intervention. The finding that parenting plays a role in the development of depressive cognitions in children suggests that it is important to target both parents and children in interventions. Parents need to be aware of the effects of their behaviors on their children and taught more adaptive parenting skills that will minimize depressive cognitions and bolster positive cognitions in their children.

Notes

A few studies have found an interaction between parenting and negative life events (e.g., Crossfield, Alloy, Gibb, & Abramson, 2002; Ge, Lorenz, Conger, Elder, & Simons, 1994). We examined the interaction between parenting and negative life events in predicting depressive cognitions. The results of these analyses were non-significant.

REFERENCES

Abramson, L. Y., Alloy, L. B., & Metalsky, G. I. (1988). The cognitive diathesis-stress theories of depression: Toward an adequate evaluation of the theories’ validities. In L. B. Alloy (Ed.), Cognitive processes in depression (pp. 3–30). New York: Guilford Press.

Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A therory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96, 358–372.

Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E. P., & Teasdale, J. D. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 49–74.

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1979). Infant-mother attachment. American Psychologist, 34, 932–937.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Gibb, B. E., Crossfield, A. G., Pieracci, A. M., Spasojevic, J., et al. (2004). Developmental antecedents of cognitive vulnerability to depression: Review of findings from the cognitive vulnerability to depression project. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 18, 115–133.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Tashman, N. A., Berrebbi, D. S., Hogan, M. E., Whitehouse, W. G., et al. (2001). Developmental origins of cognitive vulnerability to depression: Parenting, cognitive, and inferential feedback styles of the parents of individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 25, 397–423.

Beck, A. T. (1963). Thinking and depression: Idiosyncratic content and cognitive distortions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 9, 324–333.

Beck, A. T. (1972). Depression: Causes and treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Beck, A. T., & Young, J. E. (1985). Depression. In D. H. Barlow (Ed.), Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (pp. 206–244). New York: Guilford Press.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss, sadness and depression. New York: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1988). Developmental psychiatry comes of age. American Journal of Psychiatry, 145, 1–10.

Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B., & Gotlib, I. H. (1993). Psychopathology and early experience: A reappraisal of retrospective reports. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 82–98.

Cohen, P., Cohen, J., Kasen, S., Velez, C. H., Hartmark, C., Johnson, J., et al. (1993). An epidemiological study of disorders in late adolescence: I. Age- and gender-specific prevalence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 6, 851–867.

Cole, D. A. (1990). Relation of social and academic competence to depressive symptoms in childhood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 422–429.

Cole, D. A. (1991). Preliminary support for a competency-based model of child depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 181–190.

Cole, D. A. (2006). Coping with longitudinal data in research on developmental psychopathology. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30, 20–25.

Cole, D. A., Martin, J. M., Peeke, L. A., Seroczynski, A. D., & Hoffman, K. (1998). Are negative cognitive errors predictive or reflective of depressive symptoms in children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 481–496.

Cole, D. A., Martin, J. M., Peeke, L. A., Seroczynski, A. D., & Fier, J. (1999). Children's over- and underestimation of academic competence: A longitudinal study of gender differences, depression, and anxiety. Child Development, 70, 459–473.

Cole, D. A., Martin, J. M., & Powers, B. (1997). A competency-based model of child depression: A longitudinal study of peer, parent, teacher, and self-evaluations. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 505–514.

Cole, D. A., Maxwell, S. E., Martin, J. M., Peeke, L. G., Seroczynski, A. D., Tram, J. M., et al. (2001). The development of multiple domains of child and adolescent self-concept: A cohort sequential longitudinal design. Child Development, 72, 1723–1746.

Cole, D. A., & Turner, J. E. (1993). Models of cognitive mediation and moderation in child depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102, 271–281.

Conley, C. S., Haines, B. A., Hilt, L. M., & Metalsky, G. I. (2001). The Children's Attributional Style Interview: Developmental tests of cognitive diathesis-stress theories of depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29, 445–463.

Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. New York: Scribner.

Crain, R. M. (1996). The influence of age, race and gender on child and adolescent multidimensional self-concept. In B. A. Bracken (Ed.), Handbook of self-concept: Developmental, social, and clinical considerations (pp. 395–420). New York: Wiley.

Crossfield, A. G., Alloy, L. B., Gibb, B. E., & Abramson, L. Y. (2002). The development of depressogenic cognitive styles: The role of negative childhood life events and parental inferential feedback. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 16, 487–502.

De Los Reyes, A., & Kazdin, A. E. (2005). Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 483–509.

Fenzel, L. M. (2000). Prospective study of changes in global self-worth and strain during the transition to middle school. Journal of Early Adolescence, 20, 93–116.

Garber, J., & Flynn, C. (2001). Predictors of depressive cognitions in young adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 25, 353–376.

Ge, X., Lorenz, F. O., Conger, R. D., Elder, G. H., & Simons, R. L. (1994). Trajectories of stressful life events and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 30, 467–483.

Gibb, B. E., Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Rose, D. T., Whitehouse, W. G., Donovan, P., et al. (2001). History of childhood maltreatment, negative cognitive styles, and episodes of depression in adulthood. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 25, 425–446.

Glaser, B. A., Horne, A. M., & Myers, L. L. (1995). A cross-validation of the parent perception inventory. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 17, 21–34.

Goodman, S. H., & Gotlib, I. H. (Eds.). (2002). Children of depressed parents: Mechanisms of risk and implications for treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Haine, R. A., Ayers, T. S., Sandler, I. N., Wolchik, S. A., & Weyer, J. L. (2003). Locus of control and self-esteem as stress-moderators or stress-mediators in parentally bereaved children. Death Studies, 27, 619–640.

Harter, S. (1982). The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development, 53, 87–97.

Harter, S. (1985). Manual for the self-perception profile for children. Denver, CO: University of Denver.

Harter, S. (1986). Processes underlying the construction, maintenance, and enhancement of the self-concept in children. In J. Suls & A. Greenwald (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on the self (Vol 3, pp. 137–181). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Harter, S. (1988). Manual for the self-perception profile for adolescents. Denver, CO: University of Denver.

Harter, S. (1990). Causes, correlates, and the functional role of global self-worth: A life span perspective. In J. Kolligan & R. Sternberg (Eds.), Perception of competence and incompetence across the life span (pp. 67–98). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Harter, S., & Pike, S. (1984). The pictorial scale of percieved competence and social acceptance for young children. Child Development, 55, 1969–1982.

Hazzard, A., Christensen, A., & Margolin, G. (1983). Children's perceptions of parental behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 11, 49–60.

Hilsman, R., & Garber, J. (1995). A test of the cognitive diathesis-stress model of depression in children: Academic stressors, attributional style, perceived competence, and control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 370–380.

Hollon, S. D., & Kendall, P. C. (1980). Cognitive self-statements in depression: Development of an automatic thoughts questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 4, 383–395.

Jaenicke, C., Hammen, C., Zupan, B., Hiroto, D., Gordon, D., Adrian, C., et al. (1987). Cognitive vulnerability in children at risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 15, 559–572.

Janoff-Bulman, R. (1992). Shattered assumptions: Towards a new psychology of trauma. New York: Free Press.

Kaslow, N. J., Stark, K. D., Printz, B., Livingston, R., & Tsai, S. L. (1992). Cognitive triad interview for children: Development and relation to depression and anxiety. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21, 339–347.

Katschnig, H. (1986). Measuring life stress: A comparison of the checklist and the panel technique. In H. Katschnig (Ed.), Life stress and psychiatric disorders: Controversial issues (pp. 74–106). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kazdin, A. E. (1990). Evaluation of the automatic thoughts questionnaire: Negative cognitive processes and depression among children. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 2, 73–79.

Kliewer, W., & Sandler, I. N. (1992). Locus of control and self-esteem as moderators of stressor-symptom relations in children and adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 20, 393–413

Lengua, L. J., Wolchik, S. A., & Braver, S. L. (1995). Understanding children's divorce adjustment from an ecological perspective. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 22, 25–53.

Litovsky, V. G., & Dusek, J. B. (1985). Perceptions of child rearing and self-concept development during the early adolescent years. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 14, 373–387.

Liu, Y. (2003). The mediators between parenting and adolescent depressive symptoms: Dysfunctional attitudes and self-worth. International Journal of Psychology, 38, 91–100.

Lovejoy, M. C., Weis, R., O'Hare, E., & Rubin, E. C. (1999). Development and initial validation of the parent behavior inventory. Psychological Assessment, 11, 534–545.

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56, 227–238.

Masten, A. S., Best, K. M., & Garmezy, N. (1990). Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology, 2, 425–444.

Mazur, E., Wolchik, S. A., Virdin, L., Sandler, I. N., & West, S. G. (1999). Cognitive moderators of children's adjustment to stressful divorce events: The role of negative cognitive errors and positive illusions. Child Development, 70, 231–245.

McCranie, E. W., & Bass, J. D. (1984). Childhood family antecedents of dependency and self-criticism: Implications for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 93, 3–8.

McQuaid, J. R., Monroe, S. M., Roberts, J. E., Kupfer, D. J., & Frank, E. (2000). A comparison of two life stress assessment approaches: Prospective prediction of treatment outcome in recurrent depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 787–791.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Monroe, S. M., & Depue, R. A. (1991). Life stress and depression. In J. Becker & A. Kleinman (Eds.), Psychosocial aspects of depression (pp. 101–130). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Girgus, J. S., & Seligman, M. E. (1991). Sex differences in depression and explanatory style in children. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 20, 233–245.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Girgus, J. S., & Seligman, M. E. P. (1992). Predictors and consequences of childhood depressive symptoms: A 5-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 405–422.

Robinson, N. S., Garber, J., & Hilsman, R. (1995). Cognitions and stress: Direct and moderating effects on depressive versus externalizing symptoms during the junior high school transition. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 453–463.

Rose, D. T., & Abramson, L. Y. (1992). Developmental predictors of depressive cognitive style: Research and theory. In S. L. Toth & D. Cicchetti (Eds.), Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology: Vol. 4. Developmental perspectives on depression (pp. 323–349). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Rutter, M. (1988). Epidemiological approaches to developmental psychopathology. Archives of General Psychiatry, 45, 486–495.

Seroczynski, A., Cole, D., & Maxwell, S. (1997). Cumulative and compensatory effects of competence & incompetence on depressive symptoms in children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 586–587.

Stark, K. D., Schmidt, K. L., & Joiner, T. E. (1996). Cognitive triad: Relationship to depressive symptoms, parents’ cognitive triad, and perceived parental messages. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24, 615–631.

Work, W. C., Cowen, E. L., Parker, G. R., & Wyman, P. A. (1990). Stress resilient children in an urban setting. Journal of Primary Prevention, 11, 3–17.

Wyman, P. A., Cowen, E. L., Hightower, A. D., & Pedro-Carroll, J. L. (1985). Perceived competence, self-esteem, and anxiety in latency-aged children of divorce. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 14, 20–26.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Portions of this research were funded by National Institute of Mental Health Research Grant R01MH64650 and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Research Grant P30HD15052. We are grateful to the Nashville Metropolitan Public School System and Dr. Ed Binkley for assistance on this project. We are also immensely grateful for the hard work and support of Elizabeth Byrne, Erica Delgado, Kelly Lawver, Anne Cameron Morrow, Monique Ornelas, Mary Payne, Christy Resnick, Rebekah Travis, Katie Von Canon, Dana Warren, Dayna Watson, and Erica Williams.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bruce, A.E., Cole, D.A., Dallaire, D.H. et al. Relations of Parenting and Negative Life Events to Cognitive Diatheses for Depression in Children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 34, 310–322 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-006-9019-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-006-9019-x