Abstract

This paper puts forward a framework for evaluating the effects of governmental decentralization on the shadow economy and corruption. The theoretical analysis demonstrates that decentralization exerts both a direct and an indirect impact on the shadow economy and corruption. First, decentralization helps to mitigate government-induced distortions, thus limiting the extent of corruption and the informal sector in a direct way. Second, in more decentralized systems, individuals have the option to avoid corruption by moving to other jurisdictions, rather than going underground. This limits the impact of corruption on the shadow economy and implies that decentralization is also beneficial in an indirect way. As a result, our analysis documents a positive relationship between corruption and the shadow economy; however, this link proves to be lower in decentralized countries. To test these predictions, we developed an empirical analysis based on a cross-country database of 145 countries that includes different indexes of decentralization, corruption and shadow economy. The empirical evidence is consistent with the theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper intends to cast light on the relationship between decentralization, corruption, and the shadow economy. Corruption and shadow economies are pervasive and significant around the world and are widely believed to constitute a major obstacle to economic and social development. At the same time, they are two related phenomena that prove to affect and reinforce each other, as countries characterized by high levels of corruption also exhibit larger informal sectors. This is probably due to the fact that they share common roots: they are both illegal, are deeply rooted in cultural and social attitudes, and represent a consequence of inefficient and low-quality governments.

For these reasons, a more in-depth understanding of the causes and the channels of the relationship between corruption and shadow economies deserve particular attention, especially in relation to the debate over institutional design, such as, for example, the optimal degree of decentralization.

The existing literature on related topics follows three main directions. A number of studies concentrate on the relationship between the decentralization of government activities and corruption (e.g., Treisman 2000; Fan et al. 2009; Enikolopov and Zhuravskaya 2007), while other analyses focus on the relationship between corruption and the shadow economy (e.g., Friedman et al. 2000; Dreher and Schneider 2010; Buehn and Schneider 2012a). Moreover, some more recent works investigate the effect of decentralization on the size of the informal sector, finding a negative correlation (e.g., Torgler et al. 2010; Teobaldelli 2011).

Our work attempts to contribute to this debate by assuming a different perspective. We aim to understand whether decentralization may help keeping both corruption and the shadow economy in check and, at the same time, we want to identify how decentralization affects the relationship between corruption and the shadow economy.

To our knowledge, the literature that explicitly addresses this issue is scant. A previous attempt in this respect is provided by Alexeev and Habodaszova (2012), who examine the implications of decentralization for the incentives of local governments to provide productivity-enhancing local public goods and extort bribes from local entrepreneurs. They show that locally raised tax revenues help limiting the size of the informal sector, while corruption—measured by the size of bribes that local officials extort for issuing licenses—may increase or decrease, depending on the extent to which public goods are capable of enhancing the entrepreneur’s productivity. Echazu and Bose (2008) study the impact of a centralized bureaucracy on corruption, taking into account economies with formal and informal sectors. The authors demonstrate that when corrupt officials are active in both sectors, bureaucratic centralization is advantageous only if restricted to the formal sector, since cross-sector centralization can lead to higher corruption and lower welfare. They conclude that the shadow economy may cause adverse effects on bribes and welfare, depending on the organization of bureaucracy and the productivity of the informal sector.

In line with this field of research, we try to advance and improve upon the literature in two ways. In terms of theory, we develop a model that provides an explanation of the transmission channels through which decentralization may influence, both directly and indirectly, the size of the informal sector as well as corruption. Our analysis indicates that the link between the shadow economy and corruption is higher in centralized systems than in decentralized ones. In a unified country, individuals can avoid inefficient business regulations and taxes either by exiting from the official sector and going underground, or by bribing public officials, when this is possible. This implies that the level of corruption should be closely (and positively) linked to the size of the shadow economy. In a decentralized country, the competition among jurisdictions and the mobility of the agents might generate two kinds of effects on both corruption and the shadow economy. A first effect lies in the improvement of policies that leads directly to a reduction of both corruption and the shadow economy. A second effect proves to be indirect and relates to the fact that producers may now avoid the consequences of corruption by moving to other jurisdictions, that is, they do not necessarily need to go underground. This implies that in a federal system, a higher degree of corruption exerts a lower impact on the size of the shadow economy relative to a centralized one, because some of the agents will prefer moving to other jurisdictions and remain in the formal sector rather than going underground. As a result, the impact of corruption on the shadow economy is expected to be larger in centralized political systems relative to decentralized ones.

To test these predictions, we developed an empirical analysis based on a cross-country database of 145 countries that includes different indexes of decentralization, corruption and shadow economy.

The empirical evidence is consistent with the theory. We find that decentralized countries have smaller informal sectors than centralized ones and the difference between the sizes of the unofficial economy between the two institutional settings is important (on average, this is about ten percentage points, ceteris paribus). Moreover, we find a larger effect of corruption on the shadow economy in centralized states relative to decentralized ones. Results are usually robust and significant even after controlling for the endogeneity bias. In some cases, however, findings based on regressions including shadow economy show a lack of robustness. It may be due to measurement issues, endogeneity and/or sample bias. Hence, these results should be treated with some caution.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the related theoretical and empirical literature. Section 3 presents our theoretical approach and develops our hypotheses. Section 4 describes the empirical methodology, database and the estimation results. Section 5 concludes with a summary and discussion of the main results.

2 Related literature

Our work has roots in two independent strains of literature: (1) works that analyze the implications of decentralization for corruption; and (2) works that investigate the relationship between the shadow economy and corruption. We review them below.

2.1 Previous studies on decentralization and corruption

A number of studies concentrated on the relationship between the decentralization of government activities and corruption, intended as the abuse of public power for private gains through rent extraction.

Theories suggested two alternative perspectives on why the structure of government institutions and of the political process may have an impact on the level of corruption. On the one hand, the classical channels through which decentralization exerts its beneficial effects, in terms of higher government accountability and efficiency, are competition among the different levels of government for mobile resources (Tiebout 1956; Oates 1999) and informational advantages (Hayek 1948; Oates 1972). On the other hand, the main drawback of decentralization is its propensity to impede coordination between the different levels of government, which lead to inefficiently high taxes and regulatory burdens.

At the empirical level, several scholars analyze the relationship between decentralization and corruption, reaching conflicting findings. Most studies find a higher degree of decentralization to be associated with lower levels of corruption (Shleifer and Vishny 1993; Fisman and Gatti 2002a, 2002b; Arikan 2004; Lessmann and Markwardt 2010), yet other studies reach the opposite conclusion (Treisman 2000, 2006; Fan et al. 2009).

Treisman (2000) analyzes the determinants of corruption and finds that federal countries are associated with higher levels of corruption, controlling for the level of economic development. The author interprets this result, arguing that “in unitary states more effective hierarchies of control enable central officials to limit the extraction of subnational officials to more reasonable levels” (p. 441). He concludes that in countries characterized by low levels of development that are more exposed to corruption, the decentralization of political power may be problematic.

Fan et al. (2009) advance this analysis by using a new data set constructed by combining a cross-national data set on different indicators of decentralization and firm-level survey data on corruption collected for 80 countries. They show that a larger number of administrative or governmental tiers and a larger fraction of local bureaucratic personnel are related to a greater occurrence of reported corruption. However, greater subnational revenues are linked to lower corruption. The authors conclude that as governmental structures become more complex, the possibility of uncoordinated rent-seeking increases, whereas providing local governments with more autonomy in the administration of revenues helps to reduce the public officials’ incentive to accept bribes.

Fisman and Gatti (2002a) analyze the cross-country relation between decentralization and corruption and find that fiscal decentralization in government expenditure is associated with lower corruption. Their empirical results are strong and robust, even controlling, for a wide number of control variables as well as endogeneity bias, thus providing some support for theories of decentralization that highlight its benefits.

Taking a different perspective on the same topic, Fisman and Gatti (2002b) investigate whether distinct forms of decentralization differently affect corruption. In particular, they focus on the mismatch between revenue generation and expenditure decentralization in the U.S. states in order to test the theoretical hypothesis that expenditure decentralization is effective only when combined with the devolution of revenue generation to local governments. The authors find empirical evidence that large federal transfers are related to a higher rate of conviction for bureaucratic corruption.

Arikan (2004) analyzes, both theoretically and empirically, the influence of fiscal decentralization on the level of corruption and shows that a higher degree of decentralization is associated with a lower level of corruption. At the empirical level, this negative relationship is less clear and depends on the explanatory variables used.

Lederman et al. (2005) study the impact of political institutions, including decentralization, on corruption. Their empirical analysis, based on panel data, indicates that political decentralization seems to increase corruption, while fiscal decentralization is likely to lower corruption. The authors however suggest that these conclusions need to be investigated more in depth.

Enikolopov and Zhuravskaya (2007) develop an empirical analysis on a sample of 75 developing and transition countries based on a cross-sectional and panel data for 25 years in order to study the impact of fiscal decentralization on growth, public goods provision, and corruption as a measure of government quality. Their findings suggest that the beneficial effects of decentralization on corruption and economic outcomes crucially depend on the national political party system’s strength that favors local politicians’ discipline.

Lessmann and Markwardt (2010) examine a cross section of 64 countries using alternative decentralization and corruption measures in order to evaluate the positive effects of decentralization on corruption. They show that decentralization is effective in counteracting corruption if there is a supervisory body, such as a free press, able to guarantee the monitoring of bureaucrats’ behaviors.

The empirical analysis of the effects of decentralization on economic outcomes clearly needs to place problems of the decentralization proxies’ choice at its forefront. It has been argued that decentralization is beneficial in terms of accountability and good governance if accompanied by the devolution of decision-making powers to local units. Fisman and Gatti (2002a) highlight that it would be useful to have “a set of homogeneous and informative indicators of the extent of decision-making decentralization” in order to develop informative comparative analysis at cross-country level. The issue is also discussed by Rodden (2004) and Stegarescu (2005). An index sometimes used in the literature to this purpose is a dummy variable that reflects whether a country has a political federal structure, based on the Riker’s (1964) definition of a federal state, where the constitution guarantees subnational governments the power to autonomously rule and legislate.Footnote 1 However, it has been noticed that federalism may be an imperfect measure to the intention pursued, as “there can be both centralized and decentralized federations and, similarly, centralized and decentralized unitary states” (Lijphart 1984: 176), even if federalism and decentralization tend to go hand in hand, especially in developed countries. An alternative measure often employed in the literature is the subnational share of total government expenditures (or revenues), but this measure is not immune from criticism either. Fisman and Gatti (2002a) recognize that there could be a weak correspondence between budgetary items and actual decision making. If the budgets of local governments are mandated from above, then greater decentralization does not correspond to effective expenditures and the revenue-raising power of subnational units. We try to contribute to the debate by proposing a new index of governmental decentralization that reflects the extent of the resources’ devolution as well as the transfer of political responsibility to local entities.

2.2 Previous studies on corruption and the shadow economy

A growing body of literature analyzes the relationship between corruption and the shadow economy (and vice versa), trying to assess the complementarity and substitution effects, that is, whether the shadow economy and corruption are positively or negatively related to each other. The underlying idea is that in countries with a large informal sector, individuals bribe public officials in order to avoid taxation and regulatory burden. As a result, the shadow economy supports corruption since bureaucrats are induced to abuse their position because of the firm’s propensity to pay bribes in order to hide their economic activities. At the same time, a pervasive corruption may act as an additional tax in the official sector, leading individuals to go underground in order to avoid government-induced distortions. This, in turn, may increase the size of the informal sector and trigger a detrimental vicious circle in which the shadow economy and corruption foster each other, making it difficult to assess the direction of the causal link between the two related phenomena.Footnote 2

Both theoretical and empirical analyses have been put forward in trying to disentangle the interaction between the shadow economy and corruption. Johnson et al. (1998, 1999) develop a full-employment model in which individuals are employed either in the official or in the shadow economy in order to analyze the relationship between taxation and the provision of productive public goods. They derive implications about the effect of taxes and regulatory burden on the size of the informal sector and economic growth and highlight two different equilibriums that may characterize the economies. In the first case, tax distortions and the regulatory burden are low, public revenues are high, and the provision of public services is efficient, which leads to a small size of the informal sector. In the opposite scenario, the burden of taxes and regulation in the context of government-induced distortions induces a low quality provision of public services; as a consequence, people escape the official sector’s inefficiencies by going underground. In this case, especially the financing of market-supporting institutions, including regulatory agencies and an honest public administration play a key role in limiting the informal sector development. Following the predictions of the theoretical model, the authors analyze the relationship between regulatory discretion and the unofficial economy by developing a cross-sectional analysis based on a sample of 49 countries from OECD, Latin America, and transition economies during the mid-1990s. They find evidence that countries with an intensive regulatory burden are characterized by higher shares of the shadow economy, in a context of great bureaucracy inefficiencies and discretion in the implementation of regulatory rules. Corruption—as perceived by business—and a rule of law that is weak and ineffective in protecting economic activity against the public officials’ abuses of power tend to be associated with larger unofficial economies.

In line with these findings, Friedman et al. (2000) evaluate the determinants of underground activity in 169 countries using data from the 1990s and find that firms operate unofficially not to avoid taxation, but to mitigate regulatory burden and corruption. Corruption, bureaucracy and a weak legal system are systematically associated with a higher level of the informal sector.

Choi and Thum (2005) present a model in which the entrepreneur’s option to move underground constrains the corrupt bureaucrat’s ability to ask for bribes. They argue that the existence of the shadow economy helps to mitigate the public institutions’ failures to support an efficient official economy and reduces corruption.

Dreher et al. (2009) reach similar results. They develop a theoretical model that explains the relationship among institutional quality, corruption, and the shadow economy. They show that corruption and the shadow economy are substitutes as the presence of the informal sector limits the ability of bureaucrats to extract bribes from economic activities. Moreover, institutional quality is likely to reduce both the shadow economy and corruption. The predictions of the model are tested and confirmed by using a structural equation model that treats corruption and the shadow economy as latent variables in a sample of 18 OECD countries.

Dreher and Schneider (2010) develop an empirical analysis based on both a cross section of 120 countries and a panel of 70 countries for the period 1994–2002. They find that corruption and the shadow economy are substitutes in high-income countries while they are complements in low income countries. In high income countries, characterized by a good rule of law, firms have the option to bring corrupted public officials to the court, when asked for bribes. In this case, corruption is more likely to take place in order to facilitate the official economic activity and obtain benefits from the public sector. In low income countries, on the contrary, the shadow economy and corruption are likely to reinforce each other, since corruption is employed by firms to keep their activity underground. Consequently, in these countries, it is natural to observe a positive relationship between the shadow economy and corruption, while in high income countries, the opposite holds true. However, the authors specify that this mixed result depends on the indicators chosen to measure corruption as well as on how regressions are specified.

Buehn and Schneider (2012b) test the relationship between the shadow economy and corruption using a structural equation model that treats the shadow economy and corruption as latent variables. They find a positive relationship between the shadow economy and corruption and show that the causal effect of the shadow economy on corruption is stronger than the effect of corruption on the shadow economy.

3 The model

3.1 The framework

We consider an economy with a unique final good that can be produced by two sectors, the formal and the informal one. Following Teobaldelli (2011), we assume that each agent i is a consumer–producer that can produce in the formal sector using a Cobb–Douglas production function with constant returns to scale in labor x i,f and in the quantity of per capita (private) goods and services g publicly provided, that is,

where 0<α<1.Footnote 3 Production in the informal sector does not require the input provided by the public sector and the production function of this sector is

where x i,s is the amount of labor employed in shadow activities and A is a positive constant related to the efficiency of underground production.Footnote 4

Each agent i supplies inelastically 1 unit of labor, x i,f +x i,s =1, and chooses his optimal allocation between the two sectors, maximizing the income produced net of taxes. We assume that income in the formal sector is perfectly observable by the tax authorities and can be taxed at a constant rate t∈[0,1], while production in the unofficial economy is completely unobservable and, therefore, cannot be taxed. The economy consists of a continuum of individuals of measure 1.

We assume that the production in the formal sector by each individual is controlled by the bureaucracy when it comes to the respect of regulations.Footnote 5 The bureaucrat can impose a sanction equal to a fraction a∈[0,1] of the net income in the formal sector even when the producer is respecting the rules; in this case, the net income in the formal sector is equal to (1−a)(1−t)y i,f .Footnote 6 The inefficiency of the bureaucratic system and regulations implies that producers will have to incur the payment of the sanction imposed with a certain probability. We assume that this probability is a function of the inefficiency of the bureaucratic system, which is denoted by θ∈[0,1], so that with probability q(θ), with ∂q(θ)/∂θ>0, the producer has to pay the sanction, while with probability 1−q(θ), the sanction is canceled. To simplify the analysis, we assume that q(θ) is a linear function, that is, q(θ)=qθ, with q∈[0,1].Footnote 7 The producers can avoid the risk of paying the sanction by bribing the bureaucrat. The bribe B is set by the bureaucrat by making a take-it-or-leave-it offer to the producer; the offer maximizes the level of bribe that the agent is willing to pay.

The revenues of the public sector are all spent on the provision of the productive public services. The government budget constraint can therefore be written as

where G is the total amount of goods and services provided (so that g=G/n), n is the number of individuals, and ω is a parameter measuring the efficiency of the public sector in producing the goods and services. We assume that higher inefficiency θ of the bureaucracy and regulations reduces the efficiency of the public sector in this production, so that ω≡ω(θ), with ω θ ≡∂ω/∂θ<0. At some point, we also require that the function ω(θ) is “not too concave,” or more simply that ω θθ ≡∂ 2 ω/∂θ 2≤0.Footnote 8

The idea behind our framework is that higher levels of inefficiency of the bureaucracy and regulations allow the bureaucrats to extract more bribes from the producers. At the same time, such inefficiencies and over-regulations make the government provision of productive public services, such as law and order, the protection of property rights and, more generally, the functioning of market-supporting institutions, more costly. Both mechanisms have been discussed and documented in the literature of shadow economy and corruption (e.g., Johnson et al. 1997; Friedman et al. 2000; Treisman 2000).

The degree of inefficiency θ and the tax rate t are chosen by an incumbent politician whose monetary rent R corresponds to a fraction β∈[0,1] of the bribes of bureaucrats. In other words, we are assuming here that the rents from corruption benefit the politicians and bureaucrats and we abstract from the principal–agent conflicts between the two parts that may arise in some models (for a discussion, see Besley 2006). In choosing the two policy variables (θ and t), the politician maximizes a weighted average of its own utility and the utility of the median voter (e.g., Panizza 1999; Teobaldelli 2011). The objective function of the politician can be written as

where y i is the net income of the median voter. The parameter λ can be interpreted as an inverse measure of the democratic quality of the country.

We will consider two organizational models of society: a centralized state in which policy decisions (t,θ) are made at the centralized level and a federal state within which policy decisions are the responsibility of each jurisdiction. In order to simplify the analysis and exposition, we assume the existence of two identical jurisdictions. Each individual can move freely among the two jurisdictions by bearing a cost C i . Individuals are heterogeneous with respect to moving costs and the probability distribution function is denoted by f(C i ).

3.2 Characterization of the equilibrium

We now solve the model by determining the equilibrium policy in a unitary state. Then, we characterize the equilibrium policy in a federal system and discuss the implications for the shadow economy and corruption.

3.2.1 The equilibrium in a centralized state

The level of bribe set by the bureaucrat is such that each producer is indifferent to choosing between bribing the bureaucrat and accepting the gamble represented by the sanction, that is,

where the left-hand side represents the expected income when the individual does not bribe the bureaucrat while the right-hand side is the income when the latter is bribed. In the first case, the citizen pays a fine a(1−t)y f with probability qθ and nothing is extorted with the complementary probability. From (5), it follows that the level of bribe paid to the bureaucrat isFootnote 9

which implies a monetary rent R=βB for the politician equal to

where we have used the fact that all agents are identical and have a mass equal to 1.

From (1) and (3) and the fact that all agents are identical, and therefore x i =x for all i, it follows that the government budget constraint can be rewritten as

Taking into account (1), (2) and (6), the disposable income of agent i is

where x i denotes the amount worked by agent i in the informal sector.

For any given level of taxation t and inefficiency θ of bureaucracy and regulations, the individual chooses an allocation of labor in the two sectors that maximizes y i . The following lemma reports the solution to this problem.

Lemma 1

The optimal amount of labor employed in the informal sector by each individual is

The amount worked in the informal sector is monotonically increasing in the degree of inefficiency of the bureaucracy θ and is minimum at t=1−α; it is decreasing in t when t<1−α, and vice versa. Also,x=1 for t=0 and t=1.

Proof

From (9), we obtain that the first-order condition isFootnote 10

Substituting the government budget constraint (8) and taking into account that x i =x for all i, we obtain (10). Also, x(t,θ) is monotonically increasing in θ as

from ω θ <0. By deriving x(t,θ) with respect to t, we obtain

which means that the function has a minimum at t=1−α. It is decreasing for t<1−α and vice versa. That x(t,θ)=1 at t=0 and t=1 is immediate from (9). □

The optimal allocation of labor is such that the marginal revenues in the two sectors are equalized. A higher inefficiency of the bureaucracy and regulations increases the amount of labor employed in the shadow economy through two channels. On the one hand, it reduces the productivity in the formal sector by increasing corruption by bureaucrats and politicians and, on the other hand, it reduces the level of public goods and services for any given level of taxation. Instead, a higher level of taxation has non-monotonic effects on the shadow economy. It reduces the labor in the informal sector when it is relatively low and increases it at higher levels. In fact, a higher tax rate reduces the income in the formal sector, but it also allows more provision of productive public services and, therefore, a higher marginal productivity of labor in the formal sector. At low levels of taxation, the latter effect dominates, and vice versa.

We now determine the optimal policy choice (t,θ) of the politician. As he maximizes a convex combination of its rent and the utility of the median voter, we first consider the extreme cases and focus on the values of (t,θ) that maximize the R and y i .

From (9), y i is monotonically decreasing in θ, and therefore all citizens prefer θ=θ m ≡0.Footnote 11 Using the government budget constraint (8), we obtain that the disposable income of each citizen is

Using the envelope theorem, it follows that

which implies that y i is maximized at t=t m ≡1−α.

Using the expression (1) of the production function in the formal sector and the government budget constraint (8), the monetary rent of the politician can be rewritten as

It can be shown (see the proof of Lemma 2) that the values of (t,θ) maximizing the politician’s rent are t p =t m ≡1−α and 0<θ p <1. The following lemma summarizes these results.

Lemma 2

The optimal policy for the citizens (median voter) is setting the tax rate at level t=t m ≡1−α and setting the most efficient bureaucracy and regulations corresponding to θ=θ m ≡0. The policy that maximizes the politician’s rent R involves the same level of taxation but a higher level of inefficiency of bureaucracy and regulations 0<θ p ≤1.

Proof

See the Appendix. □

The intuition behind the result of Lemma 2 is the following. The optimal level of taxation that maximizes the citizens’ net income corresponds to setting t=1−α and the efficiency of the state apparatus at maximal level (θ=0). The politician also prefers a tax rate t=1−α, because the monetary rent he can exploit through corruption is related to the production in the formal sector, and the level of taxation t=1−α maximizes the net income in the formal sector. However, the politician has a different preference for the level of efficiency of the state apparatus, whose optimal value corresponds in this case to the level which balances the two opposite effects that θ exerts on R. On the one hand, a higher θ allows the politician to appropriate a higher fraction of production in the formal sector. On the other hand, a higher θ fosters corruption and reduces the amount of productive public services provided. This latter effect increases the incentive to supply more labor in the shadow economy, which reduces both the production in the formal sector and the amount of politician’s monetary rents deriving from corruption. The presence of these opposite effects leads the politician to prefer intermediate values of θ.

The following proposition characterizes the optimal policy for the politician in a centralized system.

Proposition 1

The optimal policy for the politician in a centralized state is setting taxation at level t C =t m ≡1−α and the efficiency of the state apparatus and regulations at a level θ C ≡θ C (λ), where θ C is increasing in λ, ∂θ C /∂λ≥0, that is, θ C is decreasing in the quality of democracy, with θ C (0)=0 and θ C (1)=θ p .

Proof

The politician’s objective function V in (4) is a convex combination of R in (15) and y i in (13). Both are maximized at t=1−α for any θ∈[0,1], so that V is also maximized at t=1−α. The optimal level θ=θ C (λ) follows from the fact that y i is monotonically decreasing in θ and maximized at θ=0, while R is single-peaked and maximized at θ=θ p . □

3.2.2 The equilibrium in a federal state

We now move to characterize the policy (t,θ) in a federal system. In this case, the optimal policy of the median voter is unchanged. The rent of the politician in jurisdiction 1 is

where ω 1≡ω(θ 1), x 1≡x(t 1,θ 1) and n 1=(1/2)+h(t 1,θ 1,t 2,θ 2) is the size of individuals in jurisdiction 1 and h(t 1,θ 1,t 2,θ 2) is the net flow of individuals from jurisdiction 2 to jurisdiction 1. Note that the expression for R 1 has the same expression as the one at the centralized level reported in (15), with the difference that the size of the citizens is now n 1 rather than 1. Similarly, the rent of the politician in jurisdiction 2 is

where ω 2≡ω(θ 2), x 2≡x(t 2,θ 2) and n 2=(1/2)−h(t 1,θ 1,t 2,θ 2).

Assume that the policy vector (t 1,θ 1,t 2,θ 2) is such that y f (t 1,θ 1)>y f (t 2,θ 2), so that h(⋅)>0 and there is a net flow of individuals from jurisdiction 2 to jurisdiction 1. All individuals of jurisdiction 2 with migration cost C i such that y f (t 1,θ 1)−y f (t 2,θ 2)≥C i will move to jurisdiction 1. Let F(C i ) denote the cumulative probability distribution function of C i . Then, it follows that

From (18), it can be verified that the function h(t 1,θ 1,t 2,θ 2) has the following properties: ∂h(⋅)/∂θ 1<0;∂h(⋅)/∂θ 2>0;∂h(⋅)/∂t 1<0 for t 1<1−α and vice versa; ∂h(⋅)/∂t 2>0 for t 2<1−α and vice versa; h(⋅)=0 if t 1=t 2 and θ 1=θ 2 (as the citizens have no incentives to move when the policy is the same).

The following lemma characterizes the Nash equilibrium policy in a federal state when politicians maximize their rents and agents can move across jurisdictions.

Lemma 3

The Nash equilibrium policy in a federal state when politicians maximize their monetary rent R is t 1=t 2=1−α and θ 1=θ 2=θ r where 0<θ r <θ p .

Proof

See the Appendix. □

Lemma 3 states that the competition among jurisdictions leads them to improve the efficiency of the state apparatus, that is, to choose a more efficient bureaucracy and regulations (i.e., a lower θ).Footnote 12 The next proposition defines the Nash equilibrium policy in a federal state when politicians also take into account the utility of the median voter, and therefore maximize the utility reported in (4).

Proposition 2

The Nash equilibrium policy in a federal state is t F =t m ≡1−α and θ F ≡θ F (λ), where θ F is increasing in λ with θ F (0)=0 and θ F (1)=θ r . Moreover, θ F (λ)<θ C (λ) for any λ∈[0,1].

Proof

The results are straightforward from the proof of Lemma 3 and Proposition 1. □

From Proposition 2, it follows that the tax rate in a centralized and in a federal state are the same. The rationale is that the politicians choose the tax rate maximizing the income in the formal sector from which they can extract rents through bribing. However, the level of inefficiency of the state apparatus is lower in a federal state than in a centralized system. These two facts imply that both the level of corruption and of the shadow economy are lower in a federal system as shown in the following proposition.

Proposition 3

The level of the shadow economy and corruption are lower in a federal state than in a centralized country.

Proof

The result on the shadow economy follows from the fact that the labor employed in the informal sector is monotonically decreasing in θ (see Lemma 1) and that θ F (λ)<θ C (λ) while t F =t C (see Proposition 2). The result of corruption comes from the fact that the level of corruption B in (6) and the monetary rent R of the politician are positively related. Hence, from R(θ F (λ))<R(θ C (λ)) it follows that B(θ F (λ))<B(θ C (λ)). □

As we have clarified above, a higher level of corruption increases the production in the informal sector. However, the size of this effect is likely to be different in a centralized state with respect to a federal system. In particular, it can be shown that an increase in corruption in a federal system may have a lower impact on the level of the shadow economy relative to a centralized state. This is because in a federal state some individuals (those with lower moving costs) will find it optimal to move to those jurisdictions where the level of bribes is lower, so reducing the impact of the increase of corruption on the shadow economy. The following proposition states this point.

Proposition 4

The positive effect of corruption on the shadow economy is higher in a centralized country than in a federal state.

Proof

See the Appendix. □

In sum, we have proposed a framework to analyze the effect of decentralization on both corruption and the shadow economy. The analysis has led to two main results that we will test in the next section. First, federalism or higher degrees of decentralization should help reduce both corruption and the shadow economy. Second, in federal or more decentralized countries, the impact of corruption on the shadow economy should be lower.Footnote 13

4 Empirical analysis

In this section, we empirically test the two main policy implications of the theoretical model (Propositions 3 and 4). However, there are some practical problems associated with the empirical analysis of the relationships among measures of decentralization, the shadow economy and corruption. Section 4.1 describes these econometric hitches and how we deal with them. Section 4.2 illustrates the empirical methodology and the estimation results.

4.1 Data description

There are three major practical problems associated with the empirical analysis of the relationships among measures of decentralization, estimates of the shadow economy and indexes of (perceived) corruption. The first corresponds to the measurement errors of the existing proxies of these phenomena. Decentralization is a multidimensional concept that has political, fiscal, cultural and geographical features. Thus, defining a suitable index to compare the degree of decentralization among countries is a particularly hard task. Concerning the shadow economy, as specialists in this field know quite well, all the estimates of the shadow economy are indicative and no one can really claim to be confident of the full reliability of their estimates (Dell’Anno and Schneider 2008). A similar concern exists for corruption. While there are practical reasons for using the index of perception of the size of corruption, several studies consider this measurement approach as biased by cultural factors (e.g., Mocan 2004; Andvig 2005; Søreide 2005). As a result, the criticism that these indexes reflect the quality of a country’s institutions more than the actual size of “misuse of public power for private benefit”Footnote 14 is sound.

The second practical problem is the issue of endogeneity. In this study, this issue is due to the aim of explaining the interaction between two related phenomena, as the shadow economy and corruption conditioned to the degree of decentralization. For instance, Buehn and Schneider (2012a) find a bidirectional causal effect between the two phenomena. They estimate that the positive effect of the shadow economy on corruption is stronger than the positive effect of corruption on the shadow economy.

A third departure from the assumptions of the classical linear model is the potential bias due to multicollinearity. While highly correlated variables on the right-hand side of a regression equation do not reduce the reliability of the model as a whole, the coefficients are less significant with wider confidence intervals; therefore, the interpretation of the regression coefficients is harder. To examine the joint effect of decentralization and corruption on the shadow economy means to include among the regressors of informal economy some index of decentralization together with other control variables.Footnote 15 It makes this violation of one of the assumptions of the classical linear model a difficult issue to overcome.

In the following, we deal with these three concerns. On the first issue—measurement errors—several indexes of the perception of corruption, decentralization and the shadow economy are used. Although this approach does not correct the measurement errors, it is a reasonable way to check indirectly the robustness of the estimates across different “inexact” measures.

The consequences of measurement errors and the lack of reliable indexes for corruption, decentralization and the shadow economy is one of the most relevant shortcomings in this strand of literature. As a result, we describe below how we attempt to minimize these inaccuracies in the data. Appendix B presents a comprehensive overview of the variables, definitions, and data sources.

About the measures of corruption, we standardize the most-used indexes of perceived corruption proposed in literature (Transparency International—\(\mathit{Corr}_{i}^{\mathrm{CPI}}\); Worldwide Governance Indicators—\(\mathit{Corr}_{i}^{\mathrm{WGI}}\); International Country Risk Guide—\(\mathit{Corr}_{i}^{\mathrm{ICRG}}\); World Development Indicators based on Enterprise Surveys—\(\mathit{Corr}_{i}^{\mathrm {Bribe}1}\); Enterprise Surveys from World Bank—\(\mathit{Corr}_{i}^{\mathrm{Bribe}2}\)). These indexes are calculated as the average of annual scores for all available countries around the world. With the exclusion of \(\mathit{Corr}_{i}^{\mathrm{Bribe}2}\), the averages are aimed to cover the decade from 1999–2007. This purpose, however, encounters several obstacles due to the considerable presence of missing values. Thus, our main concern is to define the time period in order to preserve the sample size. To make it easier for the interpretation of the proxies of corruption, the five indexes are rescaled on observed bounds to take values between 0 and 10, with high scores to mean high corruption. Standardizations of the indexes are as followsFootnote 16:

with:

where the subscript i indicates the countries. Sample ranges from a minimum of \(88~(\mathit{Corr}_{i}^{\mathrm{Bribe}2} )\) to \(145~(\mathit {Corr}_{i}^{\mathrm{CPI}})\).

Data on shadow economy are extracted by Buehn and Schneider (2012a). They estimate the size of the shadow economy as a percentage of the official GDP by a MIMIC approach (Shadow i ). From their panel of countries, we calculate the average of all available estimates over the period from 1999 to 2007 for the 145 countries of our sample. To check if MIMIC estimates fit with alternative approaches to estimate the shadow economy, the correlations with other indexes of informality are shown in Table 1. These alternative proxies are calculated as the averages, from 2005 to 2010, of “Percent of firms competing against unregistered or informal firms” (Inf_Comp) and “Percent of firms identifying practices of competitors in the informal sector as a major constraint” (Inf_Relev). The source of data for both the variables is the World Bank (Enterprise Surveys).

Table 1 shows that these indicators are positively correlated as expected. Taking into account that Inf_Comp and Inf_Rel do not measure the same “item” estimated by Buehn and Schneider (2012a),Footnote 17 we are quite confident that this output supports, at least in a rough way, the reliability of Buehn and Schneider (2012a) estimates. Considering that their estimates have both the widest coverage of countries (145 instead of 108) and they are much closer to the concept of shadow economy relevant for this study, these estimates are thus employed in the following.

The most relevant measurement issue encountered in collecting the data set is to look for a suitable measure of decentralization. Two main approaches exist in literature to measure the degree of country decentralization. The first kind of measures focuses on fiscal decentralization. They usually estimate a ratio between the expenditure (or revenue) of subnational government and the total government expenditure (or revenue) at the national level. Following this approach, two indexes from the IMF—Government Finance Statistics over the period 1999–2007 (Exp_Dec and Rev_Dec) are calculated. To check the robustness of our own indicators, we also consider two proxies of fiscal decentralization estimated by the World Bank (Fiscal Decentralization Indicators) calculated for a longer time period (1972–2000). These are subnational expenditures as a percentage of total expenditures (Subexp 72−00) and subnational revenues as a percentage of total revenues (Subrev 72−00).Footnote 18 A second set of proxies of decentralization looks at the political and administrative dimensions of the public decision-making process. These are three dichotomous variables (where “1” denotes the federal state) provided by Treisman (2007, here labeled D1_Dec), Persson and Tabellini (2003, D2_Dec) and Fan et al. (2009, D3_Dec).

A preliminary investigation of the reliability of these proxies to measure the same topic and of the signs of correlation among the three analyzed phenomena is possible by examining the correlation matrix (Table 2).

In line with the main literature, we expect to have a positive sign between the shadow economy and corruption (e.g., Buehn and Schneider 2012b), a negative sign between the shadow economy and decentralization (e.g., Teobaldelli 2011) and a negative sign between corruption indexes and the decentralization dummy (e.g., Fan et al. 2009).

From Table 2, two main results emerge. First, looking at the correlations among alternative measures of corruption and decentralization, we find that the indexes of corruption are positively correlated to each other. On the contrary, the proxies of decentralization show a lack of robustness. While D1_Dec, D2_Dec, Subexp 72−00 and Subrev 72−00 positively correlate to each other, D3_Dec, Exp_Dec and Rev_Dec are not correlated to the other measures of decentralization. Second, we find expected negative correlations only between some indexes of corruption (i.e., Corr CPI, Corr WGI, Corr ICRG) and some indexes of decentralization (i.e., D1_Dec, Subexp 72−00 and Subrev 72−00) but the correlations between the remaining proxies of decentralization (i.e., D2_Dec, D3_Dec, Exp_Dec and Rev_Dec) and indexes of corruption (i.e., Corr Bribe1, Corr Bribe2) are not statistically significant. As there are no theoretical reasons behind these differences of statistical relationships among indexes, we interpret this result to be a consequence of data limitation. D1_Dec, D2_Dec, Subexp 72−00 and Subrev 72−00 include between 70 and 140 countries while D3_Dec, Exp_Dec and Rev_Dec have a sample size that ranges from 45 to 68. Thus, we hypothesize that different signs of correlations are due to the sample selection bias.Footnote 19 This hypothesis points out a potential drawback for cross-country analyses that use just one proxy of decentralization. It means that empirical results depend on scholar’s choice on which index of decentralization include in the econometric analysis. To control this shortcoming and preserve the sample size, a new dichotomous variable (DT_Dec) based on the seven indexes (K) collected in our data set is proposed. It aggregates different dimensions of decentralization, into one decentralization dummy taking value of 1 if the country is defined as decentralized. In essence, this means we accept the trade off to lose information of continuous variable on fiscal decentralization (e.g. Exp_Dec, Rev_Dec) to gain a broader definition of overall decentralization and, mainly, we obtain findings that are less affected by sample selection bias. In symbols this index is calculated as follows:

where:Footnote 20

According to the DT_Dec index, among the 145 countries of our sample, we count 20 decentralized states,Footnote 21 120 centralized (i.e., D k is a negative value) and 5 countries with D k equals to zero as a consequence of missing values for all the seven proxies (i.e., Croatia, Syria and Yemen) or due to contrasting scores among the original indexes (i.e., Colombia and Taiwan).

With reference to the second statistical difficulty of this analysis—endogeneity—we apply the instrumental variables (IV) approach to address the endogeneity of corruption, the shadow economy and other variables related to economic development.

On the third concern common in this strand of literature—multicollinearity—we utilize the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to quantify the severity of multicollinearity in OLS regressions. If the degree of collinearity is severe, we apply the main conventional methods proposed in literature to deal with this issue. First, we use alternative model specifications with several variables to check the robustness of statistical tests. Second, the high correlate explanatory variables are dropped. Third, to attenuate multicollinearity consequences, the models including variables with a larger sample size are preferred (e.g., Corr CPI, Shadow, DT_Dec). This is because the larger the sample size, the smaller is the standard error. In the following, this approach is applied in order to specify models where the estimated coefficients of the variables of main interest are not affected by severe collinearity.

Following previous guidelines, we include several control variables into the data set. They capture a broad range of theoretically plausible determinants of corruption and the shadow economy in the hope of reducing omitted variable bias, endogeneity and multicollinearity sources.

With reference to institutional quality, La Porta et al. (1999) state that greater protections of property against the state embodied in common law systems improve government performances, including reducing corruption. Thus, following Treisman (2000), we consider dummies for the legal origin. It is because civil law systems differ on this dimension from common law systems. Taking into account that these variables have good performances to control for endogeneity, we also include the colonial heritage of countries to analyze the effect of corruption on the size of the shadow economy in countries with different degree of decentralization. Treisman (2006) is the source for these variables: former British colony (BritCol), former French colony (FrenCol), former Spanish or Portuguese colony (SpanPorCol), former colony of state other than Britain, France, Spain, or Portugal (OtherCol) and never a colony (NonCol).Footnote 22 For the set of dummies taking into account the “legal origin,” the source is Global Development Network Growth Database. These variables identify the origin of the Company Law or Commercial Code in each country: British legal origin (LegBrit), French legal origin (LegFren), Socialist legal origin (LegSoc), German legal origin (LegGerm) and Scandinavian legal origin (LegScand).Footnote 23

A second set of control variable is selected by following Ades and Di Tella’s (1999) findings. According to the authors countries that are more open to foreign trade tend to be less corrupt. Consequently, Foreign Direct Investment as percentage of GDP (FDI) extracted by World Development Indicators of World Bank is included in regressions.Footnote 24

There is abundant empirical literature that includes, among the controls of corruption, regressions proxies of economic development. One of the most used is the (natural logarithm of) real GDP per capita (LGDP_cap).Footnote 25 Other controls are the level of education (School), the size of public sector (Gov_size) and some proxies of institutional environment, for example, index of political rights published by Gastil index, Freedom House, etc. About the latter, considering that the political indexes are relevant sources of multicollinearity and endogeneity for our variables of interest, we opt to drop these variables from regressions as their variability is already adequately accounted by the other explanatory variables. We also consider the urbanization rate (Urban), the share of women in government at ministerial level as percentage of total in the 2001 (Wom_gov) and an index of international trade (t_open) to instrument the logarithm of real GDP per capita and the size of public sector in TSLS specifications.

With reference to the controls of the shadow economy, we further include self-employment (Self), labor participation rate (lab_part), tax revenue as percentage of GDP (T_rev) and real GDP per capita. In literature these aggregates are considered among the most relevant determinant of the underground economy (e.g., Schneider and Enste 2000; Dell’Anno 2007). Taking into account the potential endogeneity between shadow economy and variables as tax revenue and real GDP per capita, in TSLS models, we instrument tax revenue by the size of public sector and FDI and logarithm of real GDP per capita by urbanization rate and the share of women in government at ministerial level as percentage of total in the 2001.

4.2 Empirical results

In this section, we convert the main conclusion of the theoretical model (Propositions 3 and 4) in testable regressions.

4.2.1 Test on Proposition 3

Proposition 5

The levels of the shadow economy and corruption are lower in a federal state than in a centralized country.

The econometric translation of this proposition is as follows:

with i=1,…,n and test if α 1<0 and β 1<0.

In Tables 3 and 4 regressions (25) and (26), respectively, are tested. The regressions are run by OLS and TSLS to deal with the endogeneity issue.Footnote 26 Instrumental variables methods rely on two assumptions: the excluded instruments are distributed independently of the error process, and they are sufficiently correlated with the included endogenous regressors. Endogeneity problems in regressions are estimated by the Durbin–Wu–Hausmann (DWH) test. In general we find that the DWH statistic suggests a rejection of the null hypothesis, therefore endogenous regressors’ effects on the OLS estimates are meaningful, and instrumental variables techniques are required. As a consequence we provide a battery of diagnostic tests on the validity of instruments used during estimation. In sum, these tests reveal that selected IV are uncorrelated with the error term, relevant, and that the excluded instruments are correctly excluded from the estimated equation.

Regressions are specified in order to minimize the estimation bias for multicollinearity. The estimated VIF are usually smaller than 10, which would indicate an insignificant amount of collinearity. In Table 3 we report estimated output of Eq. (25).

In Table 3, we find a robust negative correlation between decentralization and the size of the corruption, as expected. In average, decentralized country has a perception of the corruption lower than centralized State of about one/two percentage points, ceteris paribus.

In Table 4 we report findings of Eq. (26).

In Table 4, we find a negative correlation between decentralization and the size of the shadow economy for regressions 6a, 6b, 7a and 7b, as expected. Vice versa, in regressions 6c and 7c—including a wider vector of control variables but smaller sample sizes—we find a statistically insignificant effect. Taking into account that this analysis has shown a relevant trade-off between sample bias and omitted-variable bias, we consider the regressions using sample with wider coverage of countries (i.e., 6a, 6b and 7a) as the most reliable models. Accordingly, in average, the difference between the sizes of the unofficial economy in the two institutional settings is about eight/nine percentage points, ceteris paribus. According to these findings, we conclude that empirical evidence supports Proposition 3: Corruption (Table 3) and Shadow Economy (Table 4) will be lower in countries with greater decentralization.

4.2.2 Test on Proposition 4

Proposition 6

The positive effect of corruption on the shadow economy is higher in a centralized country than in a federal state.

The statistical test is performed by testing if the effect of the corruption on the shadow economy in centralized countries (γ 1) is higher than in federal states (γ 2). The models for centralized and decentralized countries are respectively:

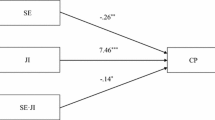

where i indexes the data for which \(\mathit{DT \_dec}=0\) in (27) and \(\mathit{DT\_dec}=1\) in (28), and X S is a vector of control variables.Footnote 27 To preserve sample size we do not split in two subsamples the data set (i.e., centralized and decentralized countries) but we opt to combine the previous regressions in an interactive model: \(\mathit{Shadow}_{i} = \gamma_{1}\mathit{Corr}_{i} + ( \gamma_{2} - \gamma_{1} ) ( \mathit{Corr}_{i}*\mathit{DT \_dec}_{i} ) + \gamma'X_{i}^{S} + \varepsilon_{i}\), where i ranges over all the data. It makes possible to test for a difference in effects of corruption between the two groups of countries preserving sample size. With this model specification when \(\mathit{DT\_dec}_{i} =0\) the multiplicative term drops out, giving the model (27), and when \(\mathit{DT \_dec}_{i} =1\) the two multiples of Corr i combine to give γ 2, yielding the model (28). Therefore, we test whether the slopes are the same by fitting the following regression:

Conclusively, if δ is negative, indicating that the regression coefficient γ 1 is significantly higher than in a centralized country than in a federal state (γ 2), it means that Proposition 4 holds.

In Table 5, we report empirical findings based on (29). Firstly, we find that results show a lack of robustness to both the choice of the index of the perceived corruption and model specifications. Unfortunately, the presence of missing values implies that alternative specifications yield different sample sizes. Accordingly, we cannot infer if the differences in the estimates are due to sample selection bias or incorrect model specification. That is, findings of this analysis should be treated with caution.

Tentatively, we conclude that, focusing on the differences between the effect of corruption on the shadow economy in the two institutional settings, in average, an increase of the CPI index of perceived corruptionFootnote 28 in a centralized (decentralized) country yields an increase of 4.2 (2.3) percentage points of the shadow economy, ceteris paribus. Thus, Proposition 4—which stipulates that the impact of corruption on the shadow economy will be lower in countries with greater decentralization—is empirically supported by data.

5 Conclusions

In this paper, we have examined theoretically and empirically how decentralization affects the relationship between corruption and the shadow economy. The literature that specifically analyzes this relationship appears to be limited and only focuses either on the implications of decentralization for the development of both the informal sector and corruption, or on the impact of a centralized bureaucracy on corruption, taking into account the existence of underground economic activities and their adverse effects on bribes and welfare.

We try to advance the existing literature on the subject in two ways. First, we theoretically analyze the transmission channels through which decentralization may influence both corruption and the development of the shadow economy, by also considering the occurrence of indirect effects that could lead these two related phenomena to affect each other. Second, from a methodological perspective, we propose a new proxy of decentralization that reflects the different indexes of decentralization. This is aimed to overcome the difficulty related to the empirical use of decentralization measures. It is due to both the complexity of the concept—which implies a scarce adherence of the existing indexes, singularly considered, to its real extent—and the large presence of missing values in available indicators—which implies that cross-country analyses may be not affected by sample selection bias.

In particular, our theoretical model predicts that decentralization is conducive to improving the quality of government intervention, leading to both a lower size of the shadow economy and a lower level of corruption. Moreover, we have demonstrated that decentralization also works indirectly in keeping the shadow economy and corruption at bay, as in more decentralized systems, individuals have the possibility to avoid corruption by moving to other jurisdictions, rather than operating informally. This implies that a higher degree of corruption exerts a lower impact on the shadow economy in more decentralized countries.

In order to test the model’s implications, we have developed an empirical analysis based on a cross-country database of 145 countries that includes a number of different indices of corruption, decentralization and the shadow economy.

The empirical evidence supported the main results of the theoretical model: (1) decentralization is significantly associated with lower shadow economy and corruption, and (2) the impact of corruption on the shadow economy will be lower in countries with greater decentralization. While the tests performed should be treated with caution, due to the problems associated with measurement issues, endogeneity and lack of robustness for estimates based on regressions including different both sample sizes and proxies of corruption, we can still derive substantial policy implications. Decentralization proves to be an essential precondition for the efficient government provision of productive goods and services as well as the accountability of governments, which facilitates the producer’s choice to operate in the official sector. This turns out to be particularly relevant in the debate over the optimal institutional design that concerns both developing and developed countries, before proceeding to welfare state reforms.

Notes

According to Riker’s definition, a federal state implies “(1) [at least] two levels of government rule the same land and people, (2) each level has at least one area of action in which it is autonomous, and (3) there is some guarantee (even though merely a statement in the constitution) of the autonomy of each government in its own sphere.”

For a comprehensive analysis of the determinants of the informal sector, see Schneider and Enste (2000).

The production function implies that the productive input provided by the public sector is rival as well as essential for production.

The technology that characterizes the informal production in our framework does not require public services as a productive input. Here, we want to capture the idea that because of their illegal status, informal agents do not benefit from government-provided goods and services that can facilitate the production by allowing them full, enforceable property rights over their capital and output. For example, Loayza (1996) refers to the protection of the police and the legal and judicial system from crimes committed against the property. Moreover, informal producers are unable to take full advantage of other public services such as social welfare, skill-training programs, and government-sponsored credit facilities.

We are not considering here the case where individuals have to pay bribes to stay underground, which could generate a negative effect of corruption on the shadow economy. We do not allow for this possibility because we recognize that firms in the formal sector are more exposed to bureaucracy than those operating in the underground economy as emphasized in the literature.

As it will be clear below, the assumption that the sanction imposed to the producer is on net output rather than on the gross one simplifies the algebra without changing the results.

The linearity of the q(θ) simplifies the analysis but is not essential as the nonlinear effects of the inefficiency of bureaucracy and regulation on the level of shadow economy and corruption may be captured by the nonlinear effect of θ on the government efficiency in the provision of the productive goods and services (see below). It is also worth remarking that even though sanctions can be imposed independently on the respect of regulation (which we assume to be costless), the probability that they have to be paid depends on the degree of inefficiencies in bureaucracy and regulations (and can well be zero in a perfect well-functioning system). This is a simple way to capture the fact that higher bureaucratic inefficiencies and over-regulation increase the production costs in the formal sector relative to the informal one and allow bureaucrats to extract more bribes from producers. However, other mechanisms might generate the same results. For example, one may assume that producers have to choose between compliance or not and that more regulations and bureaucratic inefficiencies increase compliance costs. If the producers are allowed to bribe the bureaucrats to avoid penalties, then bribes will be increasing in the level of bureaucratic inefficiency and regulation.

In the proof of Lemma 2 we require that ω(θ) is not too concave in the sense that ω θθ /ω<(ω θ /ω)2. It is clear that the non-convexity of ω(θ), i.e. ω θθ ≤0, always satisfies this condition although it is not a necessary condition.

It is worth noting that a higher level of bureaucratic inefficiencies and regulations θ has two opposing effects on the payoff of the bureaucrats. On the one hand, it benefits the bureaucrats by allowing them to extract more bribes from the producers, but, on the other hand, it also reduces the production in the formal sector (i.e., y f is decreasing in θ) so lowering the rents they can extract from the producers.

The second-order condition is always satisfied as \(\partial^{2}y_{i} / \partial x_{i}^{2} = - \alpha(1 - \alpha)[(1 - aq\theta)(1 - t)(1 - x_{i})^{\alpha- 2}g^{1 - \alpha} + Ax_{i}^{\alpha- 2}] < 0\).

As there is no heterogeneity among citizens, the median voter coincides with the representative individual in the society.

All subnational units set the tax rate at the level t=1−α as this maximizes the income of the individuals as well as the net income in the formal sector, which in turn allows extracting more rents.

While some works have addressed the first point (even though the effects of decentralization have always been considered on the two phenomena separately, i.e. either on corruption or on the shadow economy), the latter result is new as it was never emphasized theoretically or empirically tested before.

This is the definition of corruption followed by Dreher and Schneider (2010).

Buehn and Schneider (2012a) estimate shadow economy by the MIMIC approach. Their structural equation includes variables as the share of direct taxation, fiscal freedom, business freedom and GDP per capita. It implies that high correlation between the estimates of the shadow economy and these variables is expected.

We replicate the empirical analysis using scores of Corr CPI and Corr WGI rescaled on theoretical bounds. Findings are qualitatively the same.

The authors estimate shadow economy as percentage of official GDP, where shadow economy includes “All market-based legal production of goods and services that are deliberately concealed from public authorities for any of the following reasons: (a) to avoid payment of income, value added, or other taxes; (b) to avoid payment of social security contributions; (c) to avoid having to meet certain legal labor market standards, such as minimum wages, maximum working hours, safety standards, etc.; (d) to avoid complying with certain administrative procedures, such as completing statistical questionnaires, or other administrative forms.” Buehn and Schneider’s (2012a: 141).

Data set is available at: http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/decentralization/fiscalindicators.htm#Formulas.

Examining the distributions of data across the countries, missing values on the second group for decentralization proxies are concentrated on the less developed countries. Seeing that these countries are frequently characterized by higher levels of corruption, there is thus the suspicion that the orthogonality between D3_Dec, Exp_Dec or Rev_Dec and the indexes of corruption may be due to a selection bias.

We also discriminate between centralized and decentralized countries according to the threshold of 50 % of the ratio between subnational and national expenditure and revenue. However, following this procedure, only 13 countries out of 145 can be defined as “decentralized.” In the authors’ view, it is an unreasonable binding criterion to identify the decentralized country.

According to D k ranking: Canada (7); Switzerland (7); Argentina (5); Brazil (3); India (3); Japan (3); Turkey (3); United Kingdom (3); Austria (1); Denmark (1); Ireland (1); Lithuania (1); Luxembourg (1); Malaysia (1); Mexico (1); Morocco (1); Pakistan (1); Russia (1); Sweden (1); United States (1).

It is taken as dropped dummy.

It is taken as dropped dummy.

We also include an index of international trade calculated as the percentage of exports and imports of goods and services on the gross national expenditure (t_open), but it is not statistically significant.

We use the natural logarithm of real GDP per capita calculated from both countries’ averages from 1999 to 2007 and values in 1998. Results of empirical tests of Propositions 3 and 4 are robust to these alternative GDP definitions.

TSLS estimator is not applied for models 4 and 5 because Corr Bribe1 and Corr Bribe2 have small sample sizes (i.e., about 40 observations), thus these estimates are unreliable.

To take into account the problem of endogeneity for the control variables, we include both dummy variables of legal origin and colonial dominance. The other control variables are taken by Eq. (26).

This index is one of the most used in literature and has the widest sample size.

References

Ades, A., & Di Tella, R. (1999). Rents, competition and corruption. The American Economic Review, 89(4), 982–993.

Alexeev, M., & Habodaszova, L. (2012). Decentralization, corruption, and the shadow economy. Public Finance and Management, 12, 74–99.

Andvig, J. C. (2005). A house of straw, sticks or bricks’? Some notes on corruption empirics. Paper presented to IV Global Forum on Fighting Corruption and Safeguarding Integrity, Session Measuring Integrity, June 7, 2005.

Arikan, G. (2004). Fiscal decentralization: a remedy for corruption? International Tax and Public Finance, 11(2), 175–195.

Besley, T. (2006). Principled agents? The political economy of good government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Buehn, A., & Schneider, F. (2012a). Shadow economies around the world: novel insights, accepted knowledge, and new estimates. International Tax and Public Finance, 19(1), 139–171.

Buehn, A., & Schneider, F. (2012b). Corruption and the shadow economy: like oil and vinegar, like water and fire? International Tax and Public Finance, 19(1), 172–194.

Choi, J. P., & Thum, M. (2005). Corruption and the shadow economy. International Economic Review, 46(3), 817–836.

Dell’Anno, R. (2007). Shadow economy in Portugal: an analysis with the MIMIC approach. Journal of Applied Economics, 10(2), 253–277.

Dell’Anno, R., & Schneider, F. (2008). A complex approach to estimate shadow economy: the structural equation modelling. In M. Faggini & T. Lux (Eds.), Coping with the complexity of economics. Springer-Verlag new economic windows series.

Dreher, A., & Schneider, F. (2010). Corruption and the shadow economy: an empirical analysis. Public Choice, 144(1), 215–238.

Dreher, A., Kotsogiannis, C., & McCorriston, S. (2009). How do institutions affect corruption and the shadow economy? International Tax and Public Finance, 16(6), 773–796.

Echazu, L., & Bose, P. (2008). Corruption, centralization, and the shadow economy. Southern Economic Journal, 75(2), 524–537.

Elazar, D. J. (1995). From statism to federalism: a paradigm shift. Publius, 25(2), 5–18.

Enikolopov, R., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2007). Decentralization and political institutions. Journal of Public Economics, 91(2), 2261–2290.

Fan, S., Lin, C., & Treisman, D. (2009). Political decentralization and corruption: evidence around the world. Journal of Public Economics, 93(1–2), 14–34.

Fisman, R., & Gatti, R. (2002a). Decentralization and corruption: evidence across countries. Journal of Public Economics, 83(3), 325–345.

Fisman, R., & Gatti, R. (2002b). Decentralization and corruption: evidence from U.S. federal transfer programs. Public Choice, 113, 25–35.

Friedman, E., Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., & Zoido-Lobatón, P. (2000). Dodging the grabbing hand: the determinants of unofficial activity in 69 countries. Journal of Public Economics, 76, 459–493.

Hayek, F. A. (1948). Individualism and economic order. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., & Schleifer, A. (1997). The unofficial economy in transition. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2, 159–220.

Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., & Zoido-Lobatón, P. (1998). Regulatory discretion and the unofficial economy. The American Economic Review, 88(2), 387–392.

Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., & Zoido-Lobatón, P. (1999). Corruption, public finances and the unofficial economy (Policy Research Working Paper Series 2169). The World Bank.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1999). The quality of government. Journal of Economics, Law and Organization, 15(1), 222–279.

Lederman, D., Loayza, N. V., & Soares, R. (2005). Accountability and corruption: political institutions matter. Economics and Politics, 17, 1–35.

Lessmann, C., & Markwardt, G. (2010). One size fits all? Decentralization, corruption, and the monitoring of bureaucrats. World Development, 38(4), 631–646.

Lijphart, A. (1984). Democracies: patterns of majoritarian and consensus government in twenty-one countries. New Haven/London: Yale University Press.

Loayza, N. A. (1996). The economics of the informal sector. A simple model and some empirical evidence from Latin America. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 45, 129–162.

Mocan, N. (2004). What determines corruption? International evidence from micro data (NBER working paper 10460).

Oates, W. E. (1972). Fiscal federalism. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Oates, W. E. (1999). An essay on fiscal federalism. Journal of Economic Literature, 37, 1120–1149.

Panizza, U. (1999). On the determinants of fiscal centralization: theory and evidence. Journal of Public Economics, 74, 97–139.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2003). The economic effects of constitutions. Munich lectures in economics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Riker, W. S. (1964). Federalism. Origin, operation, significance. Boston: Little Brown.

Rodden, J. (2004). Comparative federalism and decentralization: on meaning and measurement. Comparative Politics, 36(4), 481–500.

Shea, J. (1997). Instrument relevance in multivariate linear models: a simple measure. Review of Economics and Statistics, 79, 348–352.

Schneider, F., & Enste, D. H. (2000). Shadow economies: size, causes, and consequences. Journal of Economic Literature, 38, 77–114.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1993). Corruption. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3), 599–617.

Søreide, T. (2005). Is it right to rank? Limitations, implications and potential improvements of corruption indices. Paper presented to IV Global Forum on Fighting Corruption and Safeguarding Integrity, Session Measuring Integrity, June 7, 2005.

Stegarescu, D. (2005). Public sector decentralization: measurement concepts and recent international trends. Fiscal Studies, 26(3), 301–333.

Teobaldelli, D. (2011). Federalism and the shadow economy. Public Choice, 146(3–4), 269–289.

Tiebout, C. (1956). A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy, 64, 416–424.

Torgler, B., Schneider, F., & Schaltegger, C. A. (2010). Local autonomy, tax morale and the shadow economy. Public Choice, 144(1), 293–321.

Treisman, D. (2000). The causes of corruption: a cross-national study. Journal of Public Economics, 76, 399–457.

Treisman, D. (2006). Decentralization, fiscal incentives, and economic performance: a reconsideration. Economics and Politics, 18, 219–235.

Treisman, D. (2007). What have we learned about the causes of corruption from ten years of cross-national empirical research? Annual Review of Political Science, 10, 211–244.

Treisman, D. (2008). Decentralization Data Set. Available at http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/polisci/faculty/treisman/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Proof of Lemma 2

From Lemma 1, it follows that politician’s monetary rent R is zero at t=0 and t=1 since x=1 in this case. R=0 also when θ=0 as there is no corruption and rents for the politician. This implies that the policy (t p ,θ p ) that maximizes monetary rents involves an intermediate level of the tax rate and a positive value of θ. The first-order conditions defining (t p ,θ p ) are the following:

Substituting (11) and (12) into respectively (30) and (31), we obtain

First, note that the sign of both derivatives is determined by the components within the square brackets. Rearranging terms in the square bracket of (33), we obtain the tax rate solving this equation to be t=1−α. From the square bracket of (32), it follows that there is a unique level of θ, which we call θ p , solving the equation

In fact, the first component is positive while the other three are negative since ω θ <0. Moreover, the first component is decreasing in θ as a higher level of θ increases the labor x employed in the shadow economy (see Lemma 1), while the other three components are increasing (in absolute value) in θ. This can be shown by considering the absolute value of these three components, and we can define

Then, we have that

since ω θ <0, ∂x/∂θ>0 and

from the assumption that function ω(θ) is “not too concave.” Finally, notice that θ p is not necessarily lower than 1 as it is possible that the square bracket of (32) is positive for all θ∈[0,1]. □

Proof of Lemma 3