Abstract

Despite big gains from easing restrictions on international labor mobility, liberalizing migration flows is not pursued unilaterally or negotiated among countries in a way that international trade negotiations are pursued. Among several key explanations is the fiscal burden imposed by immigration on native-born. The paper focuses on a central tension faced by policy makers in countries that receive migrants from lower wage countries. Such countries are typically high productivity and capital rich, and the resulting high wages attract both skilled and unskilled migrants. A generous welfare state may attract low-skill migration deter skilled migration, since it is likely to be accompanied by higher redistributive taxes.

Assuming that a group of host countries faces an upward supply of immigrants, the analysis demonstrates that tax competition does not indeed lead to a race to the bottom; competition may lead to higher taxes than coordination. There exists a fiscal externality (fiscal leakage) that causes tax rates (on both labor and capital), and the volume of migration (of both skill types), to be higher in the competitive regime than in the coordinated regime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Price wedges in international markets for commodities and financial assets rarely exceed the ratio 2:1. Wages on labor services of similarly qualified individuals in advanced and low-income countries differ by a factor of 10. Clearly, the greatest impediments to international economic exchange are those associated with labor mobility. Restrictions on the international mobility of labor are arguably the single largest policy distortion that besets the international economy. A variety of studies suggest that even a small reduction in barriers to migration will result in large welfare benefits to the global economy.Footnote 1

Nevertheless, despite big gains from easing restrictions on international labor mobility, liberalizing migration flows is not pursued unilaterally or negotiated among countries in a way that international trade negotiations are pursued. Why is this? Evidently, this is because politicians face a backlash against immigration. Among several key explanations is the fiscal burden imposed by immigration on native-born. In this paper I focus on a central tension faced by policy makers in countries that receive migrants from lower wage countries. Such countries are typically high productivity and capital rich, and the resulting high wages attract both skilled and unskilled migrants. Reinforcing this migration is the nature of the host country’s welfare state: low-skilled migrants find a generous welfare state particularly attractive. However, such a generous welfare state may deter skilled migration since it is likely to be accompanied by higher redistributive taxes.

Indeed, over the last three decades, Europe’s generous social benefits encourage a massive surge of “welfare migration”, especially low-skilled labors. In the same period US has attracted a major portion of highly skilled migrants, boosting its innovative edge. While Europe ended up in the last two decades with 85 percent of all unskilled migrants to developed countries, US retains its innovative edge by attracting 55 percent of the world educated migrants.

Hainmueller and Hiscox (2010), using survey data in the US, find two critical economic concerns that appear to generate anti-immigrant sentiments among voters: concerns about labor-market competition, and concerns about the fiscal burden on public services. Employing opinion surveys, Hanson et al. (2007) bring evidence that in the United States native residents of states which provide generous benefits to migrants also prefer to reduce the number of migrants. Furthermore, the opposition is stronger among higher income groups. Similarly, Hanson et al. (2009), again employing opinion surveys, find for the United States that native-born residents of states with a high share of unskilled migrants, among the migrant population, prefer to restrict in migration, native-born residents of states with a high share of skilled migrants among the migrant population are less likely to favor restricting migration. Developed economies do attempt to sort out immigrants by skills (see, for instance, Bhagwati and Hanson 2009). Australia and Canada employ a point system based on selected immigrants’ characteristics. The US employs explicit preference for professional, technical and kindred immigrants under the so-called third-preference quota. Jasso and Rosenzweig (2009) find that both the Australian and American selection mechanisms are effective in sorting out the skilled migrants, and produce essentially similar outcomes despite of their different legal characteristics.

Labor mobility is directly related to tax competition. In this paper I analyze whether or not tax competition among competing host countries, with perfect mobility of capital among them, and facing an upward-sloping supply of would-be migrants, leads to a race to the bottom, as described by Oates (1972).Footnote 2

Considering international capital mobility, tax-competition among countries may lead to inefficiently low tax rates and welfare-state benefits because of three mutually reinforcing factors. First, in order to attract mobile factors or prevent their flight, tax rates on them are reduced. Second, the flight of mobile factors from relatively high tax to relatively low tax countries shrinks the tax base in the relatively high tax country. Third, the flight of the mobile factors from relatively high tax to relatively low tax is presumed to reduce the remuneration of the immobile factors, and, consequently, their contribution to the tax revenue. Such reinforcing factors reduce tax revenues and, consequently, the generosity of the welfare state. Our model is somewhat similar to Tiebout’s (1956) framework of competition among localities. Tiebout’s model features many “utility-taking” localities, analogously to the perfect competition setup of many “price-taking” agents. Naturally, Tiebout competition yields an efficient outcome. The Tiebout paradigm considers the allocation of a given population among competing localities. Our model of international tax-transfer and migration competition among host countries deviates from the Tiebout paradigm in that the total population in the host countries and its skill distribution are endogenously determined through migration of various skills. As a result, competition needs not be efficient.

The organization of this paper is as follows. In Sect. 2, I briefly survey the issue of measuring the fiscal burden of migration. In Sect. 3, I describe recent empirical evidence on the “magnet” and “fiscal Burden” hypotheses. In Sect. 4, I analyze a tax- and migration-competition theory. Section 5 concludes.

2 Fiscal burden of migration

Edmonston and Smith (1997) look comprehensibly at all layers of government (federal, state, and local), all programs (benefits), and all types of taxes. For each cohort, defined by age of arrival to the US, the benefits (cash or in kind) received by migrants over their own lifetimes and the lifetimes of their first-generation descendents were projected. These benefits include Medicare, Medicaid, Supplementary Security Income (SSI), Aid for Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), food stamps, Old Age, Survivors, Disability Insurance (OASDI), etc. Similarly, taxes paid directly by migrants and the incidence on migrants of other taxes (such as corporate taxes) were also projected for the lifetimes of the migrants and their first-generation descendants. Accordingly, the net fiscal burden was projected and discounted to the present. In this way, the net fiscal burden for each age cohort of migrants was calculated in present value terms. Within each age cohort, these calculations were disaggregated according to three educational levels: less than high school education, high school education, and more than high school education. Migrants with less than high school education are typically a net fiscal burden that can reach as high as approximately US$ 100,000 in present value, when the migrants’ age on arrival is between 20 and 30 years.

Khoudour-Castéras (2008), who studies emigration from the 19th century Europe, finds that the social insurance legislation, adopted by Bismarck in the 1880s, reduced the incentives of risk averse Germans to emigrate. He estimates that in the absence of social insurance, German emigration rate from 1886 to 1913 would have been more than doubled their actual level. Southwick (1981) shows with US data that high welfare-state benefit gap, between the origin and destination regions in the US, increases the share the welfare-state benefit recipients among the migrants. Gramlich and Laren (1984) analyze a sample from the 1980 US Census data and find that the high-benefit regions will have more welfare-recipient migrants than the low-benefit regions. Using the same data, Blank (1988) employs a multinomial logit model to show that welfare benefits have a significant positive effect over the location choice of female-headed households. Similarly, Enchautegui (1997) finds a positive effect of welfare benefits over the migration decision of women with young children. Meyer (2003) employs a conditional logit model, as well as a comparison-group method, to analyze the 1980 and 1990 US Census data and finds significant welfare-induced migration, particularly for high school dropouts. Borjas (1999), who uses the same data set, finds that low-skilled migrants are much more heavily clustered in high-benefit states, in comparison to other migrants or natives. Gelbach (2004) finds strong evidence of welfare migration in 1980, but less in 1990. McKinnish (2007) also finds evidence for welfare migration, especially for those who are located close to state borders (where migration costs are lower). Walker (1994) uses the 1990 US Census data and finds strong evidence in support of welfare-induced migration. Levine and Zimmerman (1999) estimate a probit model using a data set for the period 1979–1992 and find, on the contrary, that welfare benefits have little effect on the probability of female-headed households (the recipients of the benefits) to relocate. Dustmann et al. (2009) bring evidence of no welfare migration. The average age of the A8 migrants during the period 2004, or, more accurately, the period extending from the second quarter of 2004 through the first quarter of 2009, is 25.8 years, which is considerably lower than the native UK average age (38.7 years). The A8 migrants are also better educated than the native-born. For instance, the percentage of those that left full-time education at the age of 21 years or later is 35.5 among the A8 migrants, compared to only 17.1 among the UK natives. Another indication that the migration is not predominantly driven by welfare motives is the higher employment rate of the A8 migrants (83.1 %) relative to the UK natives (78.9 %). Furthermore, for the same period, the contribution of the A8 migrants to government revenues far exceeded the government expenditures attributed to them.

A recent study by Barbone et al. (2009), based on the 2006 European Union Survey of Income and Living Conditions, finds that migrants from the accession countries constitute only 1–2 % of the total population in the pre-enlargement EU countries (excluding Germany and Luxemburg); by comparison, about 6 % of the population in the latter EU countries were born outside the enlarged EU. The small share of migrants from the accession countries is, of course, not surprising in view of the restrictions imposed on migration from the accession countries to the EU-15 before the enlargement and during the transition period after the enlargement. The study shows also that there is, as expected, a positive correlation between the net current taxes (that is, taxes paid less benefits received) of migrants from all source countries and their education level.

3 Recent empirical evidence on the “magnet” vs. “fiscal burden” hypotheses

Razin and Whaba (2011), following Cohen and Razin (2009), decompose a cross-country sample into three groups. The first group contains source–host pairs of countries which enable free mobility of labor among them. They also prohibit any kind of discrimination between native-born and migrants, regarding labor market accessibility and welfare-state benefits eligibility. These are 16 European countries, 14 of them are a part of the EU (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and UK), and Norway and Switzerland. For notational brevity, we will nonetheless refer to this group as the EUR group. The other groups include source–host pairs of developed (second group) and developing countries (third group) countries, within which the source country residents cannot necessarily move freely into any of the host countries. That is, the host countries control migration from the source countries. The host countries are the same 16 countries from the first group, and the source countries are comprised of 10 developed non-European countries (US, Canada, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Israel, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea and Singapore). The 23 developing countries in the third group are: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Ecuador, Egypt, Jordan, India, Indonesia, Iran, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Lebanon, Nigeria, Peru, Philippines, Tunisia, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey and Venezuela. This decomposition enables to plausibly assume that migration is free among the 16 countries of the first group, and is effectively policy-controlled with respect to migrants from 10 source countries belonging to the second group. It is plausible to assume that the categorizing of both groups is exogenous to our dependent variable, the skill composition of immigrants. Thus, we can identify the differential effect of the generosity of the welfare state on the skill composition of immigrants across the two groups (the “free migration” group and the “policy-restricted migration” group) in an unbiased way. Since our interest is in the effect of the generosity of the welfare state on the skill composition of migration rates, controlling for the heterogeneity in the skill (education) measurement is essential. To address this potential problem, we adjust all the migration stocks and rates for quality of education, using Hanushek and Woessmann’s (2009) new measures of international differences of cognitive skills—average international assessments of student achievement in 12 international student achievement tests (ISATs). Hanushek and Woessmann (2009) use their schooling quality measure to provide evidence on the robust association between cognitive skills and economic growth. They also find that home-country cognitive-skill levels strongly affect the earnings of immigrants in the US labor market in a difference-in-differences model that compares home-educated to US-educated immigrants from the same country of origin, thus suggesting that controlling for the quality of schooling is important. Tables 1, 2 consist of two panels. Table 1 shows the test scores for math and science scores. Table 2 provides a numerical example of how we adjust for educational quality.

We standardize cross-country education quality differences by using the Hanushek and Woessmann (2009) cognitive skills measure, based on imputed average test scores in math and science for primary through end of secondary school, all years (scaled to PISA scale divided by 100) for all source countries in our sample as our measure of Education Quality (EQ).

Since our key hypothesis is that the effect of welfare benefits on the skill selectivity of immigrants varies according to the immigration regime, we use the skill difference in the migration rates as follows:

where \(m^{i}_{s,h,t}\) is the stock of migrants of skill level i who originated from source country s and reside in host country h, as a ratio of the stock of all native workers of skill level i in the source country s in \(t = \mbox{the year }2000~(p^{i}_{s,t})\). The skill difference selection equation is where the dependent variable is DM s,h measuring the skill difference in selectivity of migrants, t=the year 2000 and t−1=the year 1990:

The first specification with lagged dependent variable refers to the indirect way of measuring the effect of generosity on the flow variable, whereas the second specification refers to the direct way of doing so where the dependent variable is the difference between 2000 (t) and 1990 (t−1).

The first null hypothesis is that Δβ 2<0. It captures the migrants’ choice in the free-migration regime. Indeed, the coefficient is negative and significant in all four regressions. That is, the generosity of the welfare state adversely affects the skill composition of migrants in the free-migration regime. The magnitude of the coefficient is even higher in the IV regressions, Table 4, than in the OLS regressions, Table 3. Whether we include the full set of control variables in X{s,h} in the regressions (columns 2 and 4) or not (columns 1 and 3) does not seem to have much of an effect on the magnitude of the coefficient. The second null hypothesis is that Δβ 3>0, reflecting the policy preference of the host country’s voters in policy-controlled migration regimes. Indeed, the coefficient is positive and significant in all four regressions. That is, the effect of the generosity of the welfare state on the skill composition of migrants is more pronounced in the policy-controlled migration regime. The magnitude of the coefficient is even higher in the IV regressions than the OLS regressions. Again, whether we include the full set of control variables in X{s,h} in the regressions (columns 2 and 4) or not (columns 1 and 3) does not seem to have much of an effect on the magnitude of the coefficient.

The table shows that for both DCs and LDCs, the social magnet hypothesis holds, and that the findings support the fiscal burden hypothesis. When adjusting for the flows by Relative Education Quality, again, the estimates for LDCs are affected more than those for DCs, and our previous results are all upheld.

4 Tax and migration competition vs. international coordination

Oates (1972, p. 143) argues that competition may lead to inefficiently low tax rates (and benefits):

The result of tax competition may well be a tendency toward less than efficient levels of output of local services. In an attempt to keep taxes low to attract business investment, local officials may hold spending below those levels for which marginal benefits equal marginal costs, particularly for those programs that do not offer direct benefits to local business.

I assume that there is a large enough number of competing host countries, to allow us to treat each host country as a ”perfect competitor”. The rest of the world serves as a reservoir of migrants for the host countries. That is, the rest of the world provides exogenously given, upward sloping, supply curves of unskilled and skilled immigrants to the host countries. I am using a version of the Tiebout paradigm. My model of international tax-transfer and migration competition among host countries deviates from Tiebout paradigm in that the total population in the host countries and labor skill composition are endogenously determined through international migration of various skills.

Consider a static modelFootnote 3 with n identical host countries engaged in competition over migrants, skilled and unskilled, from the rest of the world. The model incorporates two channels through which native households are affected by migration: the wage channel and the fiscal channel. The former relates to the fact that skilled (unskilled) individuals favor unskilled (skilled) migration since it boosts their wage. The latter relates to the fact that all migrants contribute to the financing of the public good through a proportional income tax (on both labor and capital).

A representative host country produces a single good by employing two labor inputs, skilled and unskilled, and capital according to a Cobb–Douglas production function,

where Y is GDP, A denotes a Hicks-neutral productivity parameter, and L i denotes the input of labor of skill level i, where i=s,u respectively for skilled and unskilled, K denotes the input of capital, β denotes the share of capital, and α denotes the share of skilled labor in the total share, 1−β, of labor. The competitive wages of skilled and unskilled labor are, respectively,

Note that the abundance of skilled labor raises the wage of the unskilled, whereas abundance of unskilled labor raises the wage of the skilled. Aggregate labor supply, for skilled and unskilled workers, respectively, is given by

There is a continuum of workers, where the number of native-born is normalized to 1; S denotes the share of native-born skilled in the total native-born labor supply; m s denotes the number of skilled migrants; m u denotes the total number of unskilled migrants; and l i is the labor supply of an individual with skill level i∈{s,u}. Total population (native-born and migrants) is as follows:

The rental price of capital is given by the marginal productivity condition (we assume for simplicity that capital does not depreciate):

A skilled individual holds a stock of capital, \(\bar{K}_{s}\), which is larger than the stock of capital, \(\bar{K}_{u}\), which is held by an unskilled individual; that is, \(\bar{K}_{s} > \bar{K}_{u}\), so that the skilled is unambiguously richer than the unskilled. An individual can rent her capital either at home or at the other host countries. Thus, the total stock of capital owned by residents, \(S\bar{K}_{s} + (1 - S)\bar{K}_{u}\) (assuming that migrants own no capital), does not have to equal K, the total inputs of capital. Capital taxation, if any, is levied according to the source principle, according to which each country taxes only the capital employed in that country. Denote the net-of-tax rental price of capital in all other host countries by \(\bar{r}\). Then, the residents of the representative host country must enjoy the same net-of-tax rental price at home, that is,

where τ K is the tax rate on capital employed by our representative host country.

I specify a simple welfare-state system in which there is a dual tax system: a tax at the rate τ L on labor income and a tax at the rate τ K on capital income. We allow for different rates of taxation of labor and capital in order to examine the effects of migration and capital mobility separately on capital and labor taxation. The revenues from all taxes are redistributed equally to all residents (native-born and migrants alike) as a demogrant, b, per capita. The demogrant may capture not only a cash transfer but also outlays on public services such as education, health, and other provisions, that benefit all workers, regardless of their contribution to the finances of the system.Footnote 4 Thus, b is not necessarily a perfect substitute to private consumption. The government budget constraint is given by

Note that we assume that migrants are fully entitled to the welfare state system. That is, they pay the tax rate τ L on their labor income (they own no capital) and receive the benefit b. The two types of individuals share the same utility function:

where c denotes consumption and ε>0 is the labor supply elasticity. The budget constraint of an individual with skill level i is

Note that an individual earns a net-of-tax rental price of r on all the stock of capital she owns, no matter in which country it is employed. Individual utility-maximization yields the following labor supply equation:

The indirect utility function of an individual of skill level i∈{s,u} is given by

We also assume that

which ensures that the wage of the skilled always exceeds the wage of the unskilled (w s >w u ).

We assume that there is free migration according to an exogenously given upward supply of migrants of each skill type from the rest of the world to all host countries. Specifically, the number of migrants of each skill type that wish to emigrate to the host countries rises with the level of utility (well-being) that they will enjoy in the host countries. A possible interpretation for this upward supply is as follows. For each skill type there is heterogeneity of some migration cost (due to some individual characteristics such as age, family size, portability of pensions, etc.). This cost generates a heterogeneity of reservation utilities, giving rise to an upward sloping supply of migrants. We denote the supply function of skill i∈{s,u} by

where N i is the number of migrants of skill type i and V i is the level of utility enjoyed in the host counties, i∈{s,u}. We assume that would-be migrants are indifferent with respect to the identity of the would-be host country. All they care about is the level of utility they will enjoy. Therefore, in equilibrium, the utility enjoyed by migrants of each skill type is the same in all host countries. Denote this equilibrium cutoff utility level by V i ,i∈{s,u}. Being small enough, each host country takes these cutoff utility levels as given. That is, each host country behaves as a “utility taker”. in analogy to the “price taking” behavior of each agent in perfectly competitive market. A representative host country determines its fiscal policy by majority voting among the native-born. For concreteness, we describe in detail the case where the native-born skilled form the majority, that is S>0.5 (the other case is specified similarly). Thus, the fiscal policy variables, τ L , τ K and b, are chosen so as to maximize the indirect utility of the skilled (given in Eq. (11)), subject to the government budget constraint (given in Eq. (7)), and to the free migration constraints:

Assuming that the migrants have the same preferences as the native-born, and recalling that migrants own no capital, in determining their policy, the government takes also into account that w i ,l i ,L i ,r,K,N,Y,m s and m u are determined in equilibrium by Eqs. (1)–(6), and (10). Note that in setting the optimal fiscal policy, a representative host country takes the migrants cutoff utility levels, V s and V u , as given, and also takes the net of tax return to capital, r, as given. Denote by an asterisk (∗) the levels of the economic variables that ensue with optimal fiscal policy. Each one of the n identical host countries admits \(m_{s} ^{*}\) skilled migrants and \(m_{u} ^{*}\) unskilled migrants. Thus, the aggregate demand for skilled and unskilled migrants is \(nm_{s} ^{*}\) and \(nm_{u} ^{*}\). Therefore, the cutoff utilities enjoyed by migrants, V s and V u , are determined in a symmetric Nash-equilibrium, so as to equate supply and demand:

Also, the worldwide net-of-tax rental price of capital, r, is determined so as to equate world demand for capital, nK ∗, to world supply, \(n(S\bar{K}_{s} + (1 - S)\bar{K}_{u})\), that is:

So far we assumed that the host countries compete with each other with respect to the volume and the skill-composition of migrants, and for capital.

Presumably, an unskilled median voter opts to admit skilled migrants, for two reasons: First, such migrants are net contributors to the finances of the welfare state; that is, the tax that each one pays (namely, τ L w s l s ) exceeds the benefit she receives (namely, b). Second, skilled migrants raise the wage of the unskilled. On the other hand, a skilled median voter may opt for both types of migrants. Unskilled migration raises the wage of the skilled but imposes a fiscal burden on the welfare state. Skilled migration lowers the wage of the skilled but contributes positively to the finances of the welfare state. Thus, the volume and skill-composition of migration to each one of the n identical host countries are determined in a general, uncoordinated competitive equilibrium. An alternative, albeit difficult to sustain, is for the host countries to coordinate their fiscal policy so as to maximize the utility of their decisive median voter. Naturally, this coordination comes at the expense of the migrants. In a coordinated-policy regime the cutoff utilities, V s and V u , are also controlled by the host countries, taking into account that migration takes place according to the migration equations (14) and (15). They set also the common (by symmetry) tax rate on capital, and consequently r, taking into accounts the capital resource constraint (18). Evidently, coordination can only improve the well-being of the skilled which is in power (recall that we consider for concreteness the case S>0.5) compared to its well-being under competition. In this section we compare also the tax policies that arise under competition and under coordination. Specifically, we ask whether competition can lead to “a race to the bottom” in the sense that it yields lower tax rates and welfare-state benefits, relative to the coordination regime.

We carry this comparison via numerical simulations.

Parameters:

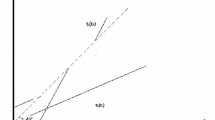

Figure 1(a) clearly refutes the race-to-the-bottom hypothesis for both the labor and the capital income taxes: the taxes are lower in the coordinated regime than in the competitive regime. The rationale for these somewhat surprising results seems to be quite basic: a fiscal externality associated with the volume of migration. There are gains and losses brought about by migration. A host country has an infra-marginal gain from migration because of the diminishing productivity of labor for a given stock of capital. On the other hand, the native-born population shares with migrants the tax collected from capital income (recall that migrants have no capital): the transfer b that the migrants receive in not financed fully by their labor income tax.

That is, the capital tax revenues paid by the native-born population “leak” also to the migrants. The infra-marginal gains from migration are due to diminishing marginal productivity of labor, as in a textbook case. There are also, rather standard, losses, or gains, to different skill groups among the native-born due to relative wage effects of migration. Each host country in a competitive regime evidently balances on the margin these gains and losses from migration. In doing so, each country takes the well-being of the migrants as given (see Eqs. (14)–(15)). It, however, ignores the fact that a tax-migration policy that admits an extra migrant raises the well-being that must be accorded to migrants by all the rest host countries, in order to elicit the migrant to come in. Thus, more capital income leaks, through capital taxation, to immigrants. As a result, it offers migrants too high level of b, levies higher taxes than under international coordination, and admits more migrants, than under coordination. Indeed, Fig. 1(b) shows that the number of both types of migrants is higher in the competitive than in the coordinated regime. Note also that tax rates on capital income are lower than tax rates on labor income. This is a way that native-born, who are endowed with capital, take advantage of the migrants, who have no capital. The literature on tax competition with free capital mobility cites several reasons for the race-to-the-bottom hypothesis in the sense that tax competition may yield significantly lower tax rates than tax coordination. With a fixed (exogenously given) population that can move from one fiscal jurisdiction to another, the Tiebout paradigm suggests that tax competition among these jurisdictions yields an efficient outcome, so that there are no gains from tax coordination.

5 Conclusion

So far we treated the immigration host countries as homogeneous group with identical endowments. Now, suppose there is continuum of R identical capital abundant (rich) countries, and a continuum of P identical capital-scarce (poor) countries.These countries are engaged in competition over migrants from the Rest of the World (ROW). The R countries are also engaged in competition over migrants from the P countries.

What are the benefits or losses from labor and capital mobility?

First, host-country gains have infra-marginal benefit from each migrant (regardless where he comes from).

Second, a similar infra-marginal benefit holds for the capital receiving country (presumably the capital scarce country), in view of capital mobility.

Third, there exists a fiscal leakage of capital tax revenues to immigrants from the rest of the world because they are endowed with no capital, and thus pay no capital tax. But they do share with native-born the revenues from capital taxation as they receive public goods.

Fourth, the capital which moves from R to P. P-country collects tax on foreign capital but pays no public goods to its native born who migrate to R country.

Outcomes of coordination among R and P countries depend on how the two types of host countries decide to divide between them the gains from coordination. There are two extreme cases: (i) All the gains accrue to R; (ii) All the gains accrue to P. All other possibilities are in between. In general, the predictions of the heterogeneous host country model are:

-

1.

Tax rates will be higher under competition than coordination for R countries.

-

2.

Tax rates will be lower under e than coordination for P countries, if the P−R difference in capital abundance is sufficiently big. This model may serve to understand Europe two-track tax completion: low taxes in the periphery, and high tax rates in the core.

In this paper I provide some support to the Tiebout hypothesis. It suggests that when a group of host countries faces an upward supply of immigrants, tax competition does not indeed lead to a race to the bottom; competition may lead to higher taxes than coordination. We identify a fiscal externality (fiscal leakage) that causes tax rates (on both labor and capital), and the volume of migration (of both skill types), to be higher in the competitive regime than in the coordinated regime. If the population growth rate is positive, the young are always in the majority. When raising period t payroll taxes, the young voter has a trade-off between the negative effect (an income transfer to the old) and a general equilibrium income boosting effect on her private pension in period t+1 and the social security benefit in period t+1. Tax rate is positive if the (state variable) capital stock is within a certain range, or zero, otherwise. Migration share of native-born population is at the maximum if the state variable, the capital stock, is in the above-mentioned range, or intermediate level, otherwise. In the case of private saving-only regime, the migration share is intermediate level. Thus, migration shares in the social security-cum-private-savings regime are either the same, or more liberal than in the private savings-only regime. A social security system effectively creates an incentive, through the political-economy mechanism, for a country to bring in migrants.

Since labor mobility wedges are to a large extent based on the political economy tensions within and between countries, to move forward from this, we need to develop institutions which will allow redesigning of the welfare state as we know it and coordination among countries which embed existing unilateral schemes of regulating labor mobility within multilateral schemes. Without multi-lateralizing the labor mobility schemes, there is a severe coordination failure: host countries’ competition for source countries’ skilled and unskilled labor could erode their welfare system, in the presence of welfare migration.

Notes

I draw on Razin and Sadka (2012).

For a dynamic model of social security with no intra- generational redistributions and capital accumulation, see Chap. 5 in Razin et al. (2011).

I can allow native born and migrants to receive different levels of the demogrants per capita. As long as unskilled receive a demogrant in excess of his/her tax contribution, the qualitative results hold. I am abstracting from the question how the migrants’ benefits are determined.

References

Barbone, L., Bontch-Osmolovsky, M., & Salman, Z. (2009). The foreign-born population in the European Union and its contribution to national tax and Benet systems. Policy research working paper, the World Bank (April).

Bhagwati, J. & Hanson, G. (Eds.) (2009). Skilled immigration today. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Blank, R. M. (1988). The effect of welfare and wage levels on the location decisions of female-headed households. Journal of Urban Economics, 24, 186.

Borjas, G. J. (1999). Heaven’s door: immigration policy and the American economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cohen, A., & Razin, A. (2009). Skill composition of migration and welfare state generosity: comparing free and policy-controlled migration regimes. NBER working papers 14738.

Dustmann, C., Frattini, T., & Halls, C. (2009). Assessing the fiscal costs and benets of A8 migration to the UK. CReAM discussion paper No. 18/09.

Edmonston, B. & Smith, J. P. (Eds.) (1997). The New Americans: economic, demographic, and fiscal effects of immigration. Washington: National Academy.

Enchautegui, M. E. (1997). Welfare payments and other determinants of female migration. Journal of Labor Economics, 15, 529–554.

Gelbach, J. B. (2004). The life-cycle welfare migration hypothesis: evidence from the 1980 and 1990 censuses. Journal of Political Economy, 112(5), 1091–1130.

Gramlich, E. M., & Laren, D. S. (1984). Migration and income redistribution responsibilities. The Journal of Human Resources, 19(4), 489.

Hainmueller, J., & Hiscox, M. J. (2010). Attitudes to ward highly skilled and low-skilled immigration: evidence from a survey experiment. The American Political Science Review, 104(1), 61–84.

Hanson, G., Kenneth, S., & Slaughter, M. J. (2007). Public finance and individual preferences over globalization strategies. Economics and Politics, 19(1), 1–33.

Hanson, G., Kenneth, S., & Slaughter, M. J. (2009). Individual preferences over high-skilled immigration in the United States. In J. Bhagwati & G. Hanson (Eds.), Skilled immigration today: prospects, problems and policies, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hanushek, E., & Woessmann, L. (2009). Do better schools lead to more growth? Cognitive skills, economic outcomes, and causation. NBER working papers 14633.

Jasso, G., & Rosenzweig, M. R. (2009). Selection criteria and the skill composition of immigrants: a comparative analysis of Australian and US employment immigration. In J. Bhagwati & G. Hanson (Eds.), Skilled immigration today, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Khoudour-Castéras, D. (2008). Welfare state and labor mobility: the impact of Bismarcks social legislation on German emigration before World War I. The Journal of Economic History, 68(1), 211–243.

Levine, P. B., & Zimmerman, D. J. (1999). An empirical analysis of the welfare magnet debate using the NLSY. Journal of Population Economics, 12(3), 391.

McKinnish, T. (2007). Welfare-induced migration at state borders: new evidence from micro-data. Journal of Public Economics, 91, 437–450.

Meyer, J.-B. (2003). Diasporas: concepts et pratiques. In R. Barre, V. Hernandez, J.-B. Meyer, & D. Vinck (Eds.), Diasporas scientifiques/Scientific Diasporas. Expertise collégiale. Expertise collégiale, IRD Editions.

Mukand, S. W. (2012). Review of “Migration and the welfare state: political-economy policy formation”. By Assaf Razin, Efraim Sadka, and Benjarong Suwankiri. Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2011. Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 806 (September 2012)

Oates, W. E. (1972). Fiscal federalism. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Pritchett, L. (2006). Let their people come: breaking the gridlock on international labor mobility. Washington, D.C.: Center for Global Development

Razin, A., & Sadka, E. (2012). Tax competition and migration: the race-to-the-bottom hypothesis revisited. CESifo Economic Studies, 58(1), 164–180.

Razin, A., & Whaba, J. (2011). Welfare magnet hypothesis, fiscal burden and immigration skill selectivity. NBER working paper 17515.

Razin, A., Sadka, E., & Suwankiri, B. (2011). Migration and the welfare state: political-economy based policy formation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Southwick, L. Jr. (1981). Public welfare programs and recipient migration. Growth and Change, 12(4), 22.

Tiebout, C. M. (1956). A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy, 64(5), 416–424.

Walker, J. (1994). Migration among low-Income households: helping he witch doctors reach consensus. unpublished paper.

Walmsley, T. L., & Winters, L. A. (2005). Relaxing the restrictions on the temporary movement of natural persons: a simulation analysis. Journal of Economic Integration, 20(4), 688–726.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge comments by a referee and the guest editor of the Journal issue.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Keynote address given at the IIPF 2012 Congress.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Razin, A. MIGRATION into the WELFARE STATE: tax and migration competition. Int Tax Public Finance 20, 548–563 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-013-9282-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-013-9282-z