Abstract

Over the last decade, bank industry has made a significant investment on mobile banking (MB) as an innovative tool with an expectation that MB services increase customer satisfaction. While the focus has been increasingly on MB adoption, banking research shows more value is generated with frequent and continued usage of MB services, an area that has been given little attention. This study integrates privacy and personalization into TAM theoretical model to address this gap. SEM analysis of a sample of 486 MB customers from a US local bank reveals that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are significant predictors of satisfaction, while satisfaction can determine continued usage intention of MB. However, the interaction effect shows statistical significance for privacy, but not for personalization. Limitations and implications for academia and industry are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Approximately 75.8% of the U.S. population owns a smartphone today (Lella 2015). Smartphone ownership has been growing steadily over the last decade since the introduction of iPhone. This growth, combined with a surge in mobile commerce (m-commerce) and sharing economy, has driven the demand for both mobile banking (MB) and mobile payment (MP) systems. MB focuses on connecting users to the bank from their smartphones to conduct interactive transactions such as account information, transfer funds, bill payment, and others (Crowe et al. 2015). The same report finds that 78% of U.S. banks currently offer MB and another 16% plan to offer within the next year. MB is considered a strategic service by banks today to build customer loyalty and increase customer retention. Multiple studies from the banking industry (Fiserv 2014; Fiserv 2012) show a meteoric rise of MB services, with roughly 35% of bank interactions in U.S., and 30% of bank interactions globally are conducted through MB - a surge of 19% from 2013. MB has, thus, become a dominant method for consumers to interact with their banks. Today, more bank interactions are handled through MB than ATM or bank branches due to the tremendous economic benefits. Digital transactions cost about 17 cents each, compared with 85 cents for ATM transaction, and $4 for a branch transaction (Fiserv 2014). Prior studies on mobile technology have shown that both adoption and usage increase with higher levels of ease of use and customer satisfaction (Hong et al. 2006; Laumer et al. 2010). Although the primary focus of academic research has been on MB adoption (Carter and Weerakkody 2008; Lin 2011; Chang 2010; Shen et al. 2010; Zhou 2012) rather than on continued usage intention of mobile banking (CUMB), banking research shows more strategic and economic benefits to banks from the latter. Payoffs are higher when customers keep using MB on an ongoing basis, as they purchase more services, thereby generating more revenue for banks (Fiserv 2014). Usefulness and ease of use have been widely used in MB adoption research with the use of Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Chung and Kwon 2009). However, because the focus of the above studies is on initial adoption and not continued usage intention, they have not explored the influence of privacy issues or personalization on mobile banking. Post-adoption studies on mobile technology have shown that privacy and personalization tend to either decrease or increase satisfaction and continued usage intention (Park 2014; Sutanto et al. 2013; Xu et al. 2011).

Privacy is about individual rights to protect personal information from service providers. Consumers have cited privacy as a major reason for not using mobile payment and mobile commerce systems (Zhang et al. 2013). For example, 70% percent of banking institutions have highlighted security concern as the biggest barrier to MB adoption while customer privacy protection, identity theft, malware and data breaches as top concerns for improving MB security (Crowe et al. 2015: p. 43–44). Privacy fears affect consumer behavior when using mobile devices with real-time tracking features (Keith et al. 2013) and inhibit their acceptance by consumers (Xu et al. 2011). Banks that address privacy concerns with better communication and awareness have higher MB usage (Fiserv 2014). Therefore, it is important to study the influence of consumer privacy on CUMB.

Personalization involves customizing the user interface and graphics to each users’ need. Research shows that apps with personalization capability increase customer satisfaction, loyalty, continued usage and provide a higher return on investment for the banks (Fiserv 2012). Personalized MB applications require the use of customer profiles, customer preferences, prior usage data of MB service and social media data. Personalization increases adoption and can sustain continued usage of IT due to the increase in user satisfaction (Park 2014). However, information collection process can restrain usage of IT as users feel an invasion of their privacy (Dhar and Varshney 2011), which creates a conflict between personalization and privacy. This personalization-privacy paradox is a prominent phenomenon in mobile usage studies (Xu et al. 2011). Mobile location-tracking services are a great resource for personalized service but privacy restrictions limit sharing personal information with third parties (Sutanto et al. 2013). This suggests both personalization and privacy could have a reverse impact on customer satisfaction and in-turn on CUMB. Thus, our study focuses on the post-adoption behavior of users on mobile banking. The study’s main contribution is to address an existing gap found in MB literature by exploring the impact of both privacy and personalization on user satisfaction and continued usage intention with MB services. The rest of this paper is structured as follows; the next section provides related work on mobile continued usage intention and CUMB followed by our research model and hypotheses development, research method, data analysis and results from SEM analysis of our survey data. The last three sections end the paper with discussion, limitations and conclusion from our study.

2 Related Work

2.1 Continued Usage Intention of Mobile Technology

Prior research has considered continued usage intention of mobile technology as a crucial outcome to determine the success of mobile technology because it is cheaper to retain current customers and loyal customers generate more revenue (Chen 2012; Dai et al. 2014). Both Chong (2013) and Lu (2014) examined mobile commerce and proposed that when customers perceive mobile commerce to be useful, easy to use, and innovative tool, along with having an enjoyable interaction, they become more satisfied and willing to continue using it. Zhou (2013 and 2014) has examined post-adoption of mobile payment and found that continued usage is reinforced when users perceive trust, flow, higher performance expectancy, and satisfaction.

Prior studies on post-adoption have combined TAM with other models, such as Expectation-Confirmation Model for IT (ECM-IT), to provide a better prediction power (Hong et al. 2006) for continued usage intention of both IT and mobile technology (Boakye et al. 2012; Hong et al. 2006; Thong et al. 2006; Hsu et al. 2006). Besides TAM and ECM-IT, value-based model predicts usage of mobile users through applying the concept of IS behavior- habit, which is the output construct of initial adoption but is the input construct to continued usage intention (Setterstrom et al. 2013). Another value-based model shows strong prediction of continued usage when evaluating the mobile service value based on the analysis of benefit and cost (Dai et al. 2014).

TAM has been a very popular model for IT adoption studies since its introduction by Davis (1989). TAM helps determining users’ intention to accept new systems based on its’ perceived usefulness and ease of use. Due to its parsimony and simplicity, TAM is preferred over the theory of planned behavior (TPB) (Hong et al. 2006). Both TAM’s elements of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, which are deeply rooted in theory of reasoned action (TRA) (Davis et al. 1989), have been considered the most popular two factors employed in examining mobile technology adoption. In a MB context, perceived usefulness assesses to what extent MB can improve conducting banking services, whereas perceived ease of use assesses to what extent MB can be perceived as a user-friendly app (Davis 1989).

Many studies have extended TAM to study continued usage intention; the post-adoption stage that follows initial usage (Zhang et al. 2011; Boakye et al. 2012; Chong 2013; Thong et al. 2006). Hong et al. (2006), also, emphasize that TAM has been used extensively to examine the intention of experienced users to continually using IT applications rather than those inexperienced ones. In addition, the model of ECM-IT has integrated TAM constructs, perceived usefulness and ease of use, as antecedents to user satisfaction, which is considered a significant predictor of continued usage intention (Bhattacherjee 2001; Chong 2013; Hong et al. 2006; Lee and Park 2008). Therefore, we believe TAM constructs would be good predictors for measuring MB user satisfaction and continued usage intention.

2.2 CUMB

CUMB is defined as the intent to continue using MB after the initial adoption phase (Bhattacherjee 2001). While flow theory and task-technology fit (TTF) model have been employed to study CUMB through satisfaction, ECM-IT besides TAM plays more significant role in predicting CUMB (Chen 2012; Yuan et al. 2016; Zhou and Liu 2014). ECM-IT was developed and advocated by Bhattacherjee (2001) after being adapted from Expectation-Confirmation Theory (ECT) that is well-known theory in the literature of consumer behavior. Nevertheless ECM-IT may be considered the dominant model in determining CUMB, it does not account for the impact of either personalization and privacy. The privacy-personalization paradox has revealed its inevitable impact in different but similar contexts (Xu et al. 2011; Sutanto et al. 2013). This does not only give relevance but also makes it one of the missing links in MB literature as per our review in Table 1. Both privacy and personalization are of a great significance and manifested to be pertinent determinants of satisfaction and IS continued usage intention as well as have been abundantly emphasized in IS literature (Chang et al. 2011; Tong et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2006). On the other hand, our review shows that CUMB has been given sparse attention (Table 1) though there is a greater economical value associated with it (Chen 2012) as it reflects retention and loyalty rate among customers.

3 Research Model & Hypotheses

TAM, when integrated with other models, can improve the prediction and analytical power of continued usage intention (Hong et al. 2006). Accordingly, our research model incorporates two factors - perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use - from TAM (Davis 1989) with three other factors - satisfaction, personalization, and continuance usage - from the Park model (Park 2014). Privacy is underlined to play a crucial role on satisfaction (Chang et al. 2011). Sutanto et al. (2013), also, propose there is a paradox between personalization and privacy of IS usage. This study attempts to inform on this hypothetical phenomenon, thus, privacy is incorporated into the research model.

Drawing on prior research (Bansal et al. 2008; Thongpapanl and Ashraf 2011; Wang and Groth 2014), we indicate that privacy and personalization can show a reverse moderating role on satisfaction, which in turn serves as a mediating factor to CUMB (Hong et al. 2006). Thus, our conceptual model has perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use as independent variables, privacy and personalization as independent and moderating variables, while satisfaction and continued usage intention of MB as dependent variables (Fig. 1).

3.1 Perceived Usefulness (PU) & Perceived Ease of Use (PEU)

TAM is based on TRA (Davis et al. 1989) and is often used by IS researchers to determine behavioral intention and actual use based on its PU and PEU (Taylor and Todd 1995). These two factors are found to play a major role in determining satisfaction in contexts similar to MB, for example, in online banking (Bhattacherjee 2001), in mobile internet (Hong et al. 2006), in online university (Joo et al. 2011), and in mobile technology (Lee and Park 2008). Thus, we replicate and hypothesize that:

-

H1: Perceived usefulness is positively related to customer satisfaction in MB.

-

H2: Perceived ease of use is positively related to customer satisfaction in MB.

3.2 The Role of Privacy

Privacy reflects the extent an individual has control over his/her personal information when interacting with MB (Hong and Thong 2013). Not having the control over personal information may result in an elevated level of privacy concerns. Mobile users usually show their privacy concerns when interacting with online products or services (Sutanto et al. 2013). Two empirical studies suggest that online gamers and shoppers become more satisfied when they less concern about their privacy in cyberspace (Chang et al. 2011; Dharmesti and Nugroho 2013). As well, once the level of privacy concerns is getting high in MB, trust and satisfaction become low among customers, which in turn may lead to decrease continued usage intention of MB (Wang et al. 2006; Zhou 2012). This suggests that privacy concerns can influence the level of satisfaction among MB users negatively. On the other hand, MB users most likely find themselves less productive and comfortable when their privacy concerns are highly elevated. The moderating effect of privacy has been evidenced in a number of different milieus, including but not limited to the usage of e-commerce and health systems (Bansal et al. 2008; Xu et al. 2011). According to the above, we believe privacy concerns can be a negative predictor and moderator:

-

H3: Privacy concerns are negatively related to customer satisfaction in MB.

-

H3.1: Privacy concerns will moderate the effect of perceived usefulness on customer satisfaction, such that the effect will be weaker for MB users with more privacy concerns.

-

H3.2: Privacy concerns will moderate the effect of perceived ease of use on customer satisfaction, such that the effect will be weaker for MB users with more privacy concerns.

3.3 The Role of Personalization

Personalization considers providing tailored services to MB users based on their behaviors and preferences (Xu et al. 2011). Since personalized services help to conduct financial transactions in a quicker manner and easier fashion, they can make MB users more efficient and effective in their interaction with MB services; therefore, they could lead to higher satisfaction among those users. Prior studies have shown that personalized services predict satisfaction among Internet banking users (Tong et al. 2012). This suggests that personalization can influence the level of satisfaction among MB users positively. Empirical studies have validated the moderating role of personalization on the level of satisfaction (Thongpapanl and Ashraf 2011; Wang and Groth 2014). For example, through personalization a bank can improve on the usefulness and ease of use of MB app by conveniently placing the services frequently used by the customers at the primary user interface, which enhances their usability, thereby increasing user satisfaction. Thus, we believe when customers are provided with a personalized experience, their satisfaction level will shift up. Accordingly, we hypothesize that personalization can be a positive predictor and moderator:

-

H4: Personalization is positively related to customer satisfaction in MB.

-

H4.1: Personalization will moderate the effect of perceived usefulness on customer satisfaction, such that the effect will be stronger for MB users with higher personalization.

-

H4.2: Personalization will moderate the effect of perceived ease of use on customer satisfaction, such that the effect will be stronger for MB users with higher personalization.

3.4 Customer Satisfaction

In our study context, satisfaction refers to what extent a person feels satisfied towards services provided by MB (Bailey and Pearson 1983). Consumer satisfaction, as cited in extant research, has significant influence on continued usage intention of IT (Park 2014). Satisfaction is a critical antecedent of continued usage intention due to consumers’ sensitivity towards switching cost in online commerce (Hsu 2014). Therefore, consumers that are satisfied with existing MB services do not switch to competing services according to the rational decision-making perspective (Kim and Gupta 2009). According to Delone and Mclean (2003), customer satisfaction can play a major role in determining IS usage. Bhattacherjee (2001), also, validates empirically the relationship between customer satisfaction and continued usage intention of online banking. Thus, we replicate and hypothesize that:

-

H5: Customer satisfaction is positively related to CUMB.

4 Research Method

4.1 Survey and Data Collection

Our study data was collected from customers of a local bank, headquartered in the northeastern region of the United States, via an online survey. The survey, with closed-ended questions, consisted of two sections; (i) demographic questions about gender, age, education, and work; and (ii) research questions about the variables of interest. For more efficient recruitment procedure: (i) the questionnaire had been administrated directly by the bank; (ii) an incentive was provided from the bank to donate $1000 to a charity organization for completing the survey; and (iii) the survey was open for nearly a month with two follow-up reminders sent to customers. Participation was voluntary and customers could opt out any time during the survey.

Our data collection approach was successful with a 16% response rate (939 customers) but due to critical missing data, our sample had been reduced to 851 valid respondents. We included both users and non-users of MB, but our research analysis focused primarily on MB users only (486 participants). We analyzed the reasons for not using MB (e.g., inconvenience to use MB, unaware of MB, security threats in MB, etc) and communicated them to the bank to help in finding a good addressing strategy. Log data of MB services from the system reporting file was included to compare between actual usage and perceived usage.

4.2 Pilot and Measurement Instruments

The survey items were assessed for content validity first by subject matter experts and later for face validity. These items were pilot tested with 130 internal bank customers and preliminary evidence had been found for the scales validity and reliability. The 130-bank respondents were asked to comment on clarity and understandability of the questions at the end of the survey. Pilot study helped us revise the survey and making it more clear and understandable before the final survey was sent to all online customers of the bank.

Our survey constructs and items (Tables 1 and 2) were adapted from literature in a similar area. The items were measured by a 7-point, Likert-scale with a range of 1, “strongly disagree” to 7, “strongly agree”. TAM factors of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use were adapted from Davis (1989). These two factors showed to have a composite reliability of 0.94 and 0.89, respectively. Privacy was adapted from Hong and Thong (2013) and personalization was adapted from Xu et al. (2011). Privacy and personalization showed to have a composite reliability of 0.88 and 0.93, respectively. Customer satisfaction was adapted from Fornell et al. (1996) and Thong et al. (2006) while continued MB usage intention was adapted from Bhattacherjee (2001) and Hong et al. 2006. Satisfaction and continued usage intention showed to have composite reliability of 0.92 and 0.85, respectively. The adapted variables were analyzed statistically and described in terms of their means and standard deviations in the below table.

4.3 Participants’ Demographics and Actual Usage Comparison

Participants’ demographics (Table 3) were divided into three groups (full sample, MB-users, and non-users). Our main focus in this study is on MB-users sample, which showed that the majority group of the respondents is full-time employed females who aged between 56 and 65 and have a college degree while the minority group is part-time employed males who aged less than 25 years and have associate degree “2-year diploma”. However, non-users group can help the bank to investigate their demographics and accordingly design a specific marketing campaign for promoting MB services among them.

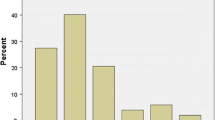

The bank provided us with access to actual usage data of MB services from the system reporting log file. This data was collected during the period of our survey and then averaged on a weekly basis so that we can compare it with survey responses (Fig. 2). MB usage survey questions were designed to capture the same data provided by the log file to enable a valid and reliable comparison.

From Fig. 2, it is evident that customer actual usage of MB exceeded their perception (survey) in all the categories above except for “Transfer funds to pay a loan or overdraft”. Overall, the gap between actual usage data and survey is not significant. This inference was supported with t-test (p-value = 1.079). Therefore, we can conclude that participants were truthful in their responses on the usage of MB services.

5 Data Analysis and Results

5.1 Measurement Model

Our data analysis shows no high correlation between the variables (Table 4). It is, also, notable that the square root of average variance extracted (AVE) for each factor (numbers in bold diagonal) has a greater value than other correlation coefficients of the same factor. Hence, discriminant validity is acceptable.

Data was, also, analyzed for convergent validity to determine to what extent the items are reflecting their relevant constructs. Factor loading and communality (COM) for each item, composite reliability (CR), AVE, internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) and variance inflation factor (VIF) for the constructs are indicated in Table 5 below. All item loadings are good (0.6 or greater) on their corresponding factor. This suggests that the items are relevant, non-redundant and form independent constructs. Communality for each item is greater than 0.5, which denotes that items share common features except for CUMB3 which can be rounded up to 0.5. All CRs and AVEs are greater than 0.7 and 0.5, respectively, which establishes a good convergent validity. Alpha values are greater than 0.7 for each factor and the total Cronbach’s alpha for all factors is 0.914. Thus, all factors demonstrate good reliability (Zhou 2013). VIF for all factors is smaller than 5, which indicates there is no collinearity between the variables.

5.2 Structural Model

Since structural equation modeling-partial least square (SEM-PLS) is immune to violation of normality assumption, it was used to test the model hypotheses and generate path coefficients. SmartPLS software was used for testing the model. We have four independent variables: PU, PEU, PY, and PR; two moderating variables: PY and PR; and two dependent variables: CS and CUMB. The tested model is depicted in Fig. 3 with path coefficients, signs, and R-squares and the detailed SEM-PLS results are shown in Table 6.

As per Table 6 below, perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are significant determinants of satisfaction, while privacy and personalization are not significant in the SEM regression model. Thus, H1 and H2 are supported whereas H3 and H4 are not. For the interaction effects, privacy was found significantly moderating both perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use but with an unexpected sign to perceived ease of use. Personalization was found to have no significant moderating effect. Thus, H3.1 is supported and H3.2 is partially supported but both H4.1 and H4.2 are not supported. Customer satisfaction is positively related to continued usage intention of MB, thus, H5 is supported. Besides the path coefficients, the quality of the model can be evaluated by the variance explained or R-square. And as per our tested model, the variance explained accounted for customer satisfaction and continued usage of MB is 0.693 and 0.459, respectively.

To further our understanding of (i) the privacy-personalization paradox; and (ii) the mediation role of satisfaction, we only analyzed the direct relationships between all predictors and CUMB. As per Table 7 below, perceived usefulness and privacy concerns appear to be insignificant in predicting CUMB while perceived ease of use and personalization appear to be significant in determining CUMB. Customer satisfaction, surprisingly, is not related to CUMB. We further illustrate these results with providing some reasonable interpretations in the next section.

6 Discussion

6.1 Summary of Findings

The results of privacy and personalization as predictors and interaction effects are unexpected and hence need more prudent investigation to reveal the reasons behind. As per our investigation, we find that, we find that, first, although privacy is very crucial aspect in MB app, some customers have a high confidence in the bank that their information will not be accessed or shared with a third party, hence, they don’t show a high concern about privacy. Second, the surveyed customers are not provided with any options from the bank to personalize their MB experience. This may have contributed to making both privacy and personalization insignificant determinants of satisfaction as well as it may affect the interaction of personalization with TAM factors. Additionally, most likely both privacy and personalization have not been given a considerable attention by the customers. Being relatively a mid-sized bank, customers usually have a close relationship with the bank representatives, and therefore, show a higher level of trust in banking services. In other words, participants of our study focused on efficient and flexible performance of their banking interactions without giving much thought to the aspects of privacy and personalization. However, we find that personalization has a direct significant impact on CUMB, and hence, it might not be mediated by satisfaction as confirmed by Park (2014). Privacy, in contrast, is not significantly related to CUMB. This supports the paradox existed between these two factors; when customers are looking for more personalized services, they overlook their privacy concerns. Overall, we do consider that both of these factors could be important in the long-run with mature usage of MB services.

The interaction effect of privacy with perceived usefulness is significantly supported. This means that the bank customers like to be more productive with MB but when their privacy concerns are not addressed in a proper way, they tend to be less productive and hence less attached to MB, which leads to less satisfaction; they may even go to branch for conducting their financial transactions. On the other hand, the interaction effect of privacy with perceived ease of use is significant but with a reverse direction. This means that the bank customers see an increase in MB flexibility to handle their transactions even if they have high concerns about privacy. This is extremely unexpected but may indicate these customers do not link the easiness part of the system with their privacy concerns. In other words, they think that MB is getting easy with the services it provides even its privacy is not getting any high. Our findings indicate that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are significant determinants of satisfaction; consistent with Joo et al. (2011) and Lee and Park (2008). Privacy and personalization show no impact on satisfaction directly; these relationships are found in prior research (Alawneh et al. 2013; Tomovska-Misoska et al. 2014; Thongpapanl and Ashraf 2011; Wang and Groth 2014). While personalization seems not to have an interaction effect on satisfaction, privacy shows to have it with both perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. This moderating effect of privacy is confirmed with the studies of Bansal et al. (2008) and Xu et al. (2011). Our conclusion regarding satisfaction, as an important predictor to CUMB, is consistent with the findings of Bhattacherjee (2001) and Hong et al. (2006).

6.2 Implications for IS Theory

The area of mobile technology is rich with opportunities for IS researchers who want to examine either adoption or post-adoption through refining the existing theoretical models. TAM is considered a well-established model in predicting IS usage (Davis 1989; Davis et al. 1989), but it focuses on two specific beliefs, which limits its theoretical boundary for providing a sufficient explanation of this phenomenon. Our study attempts to break this boundary by extending TAM with relevant belief factors from other models, like ECT-IT and Park, to improve its theoretical contribution in the MB continued usage context. Our research has empirically validated the extended model and hence increase the understanding of MB usage. In particular, TAM does not account for the customers’ perception of privacy and personalization of IS services. Once those factors are integrated to TAM, its analytical power considerably increases (Davis et al. 1989); which indicates that TAM is developed with an embedded capability to explain various types of IT innovations, including MB.

Considering the paradox of privacy and personalization proposed by Xu et al. (2011), this study taps on this phenomenon and shows such paradox may exist in mobile technologies (e.g., MB). We restrict this study to examine the privacy-personalization paradox on satisfaction and CUMB. According to our analysis, MB users tend to have a high level of privacy concerns when interacting with TAM factors, which in turn influences personalized services to be at the minimum. As well, the reverse impact of privacy and personalization is clearly manifested on CUMB. This indicates that there is an evident trade-off between those two factors (Xu et al. 2011). However, the main goal achieved by the study is revealing their moderating role in a MB context and accordingly contributing to the knowledge stock of mobile banking research. In other words, we address the existing gaps in the previous studies of Chen (2012), Yuan et al. (2016), and Zhou and Liu (2014) by complementing TAM and ECM-IT with the privacy-personalization paradox. Hence, this study has brought this paradox phenomenon to MB area and can be a starting point to further investigating different segments of MB users. For example, MB users can be divided into homogeneous groups based on their demographics and then compared under the scope of such paradox to generate insightful conclusions.

6.3 Implications for Practice

Our study finds that customers who perceive the current MB services to be convenient, helpful, effective, easy, and effortless show a higher level of satisfaction, which results in a higher tendency to continue using MB in the future. Our focus about the relationship between the privacy-personalization paradox and CUMB is central to our discourse, but satisfaction, affected by the level of privacy concerns, is heavily weighted among customers as it can have a huge impact on their loyalty and retention (Fornell et al. 1996).

In the light of these findings, we can state that mid-sized banks should address their MB services by focusing on: 1) enhancing the aspects of productivity and performance to reflect usefulness, 2) increasing flexibility and agility to reflect easiness, and 3) augmenting their privacy level with better security firewalls against data breaches and stronger policies against data sharing. Hence, MB future strategies initiated by banks should integrate the mentioned recommendations into their business strategic plan which will help improve their customer retention rate and loyalty, as reflected in this study by the intention to continue using MB services. As per the demographics, banks can also increase MB usage by targeting the MB minority groups, such as, the male customers less than 25 years old who have part-time jobs and 2-year diploma, with a specific poll to survey their reasons for the low involvement with MB.

7 Limitations and Conclusion

Our study has a few limitations which provide future research opportunities. First, although we have a good sample size, it had been obtained from one bank at a single point of time (cross-sectional sample), which limits our scope to interpret the results. This interpretation could be extended to other US mid-sized banks with similar customers; however, the findings may not be generalizable to all bank customers. Thus, we recommend further research in this area by including banks of different sizes and various geographic regions to enhance our model’s external validity. Second, this study suggests association rather than causality; the causal relationship should be addressed in future research through a longitudinal study or time-based regression analysis. Third, the survey is considered a self-reported data, which sometimes conveys unnoticed bias. For example, some customers may be pleased with bank services or representatives; hence, they give the highest rating for anything asked about MB.

Nowadays, mobile users like to have more personalized services but at the same time they show concerns about their privacy, which makes it a paradox. This paradox provides an opportunistic research area in MB and hence has been investigated in our study. We conclude that personalization should be addressed with better data collection and analytics on consumers while respecting privacy concerns raised by the customers. At the same time, the bank needs to provide quicker and easier ways for their users to complete financial transactions. This will improve MB services and increase trust and confidence of the customers in MB. Contributions from our study are two-fold. First, it reveals the direct and indirect effect of both privacy and personalization on continued usage intention of MB; therefore, it leverages our understanding and expand our knowledge of this phenomenon. Second, it unfolds practical implications for banks on how to improve MB services for increased customer loyalty and usage which ultimately nets more profits to the banks.

References

Alawneh, A., Al-Refai, H., & Batiha, K. (2013). Measuring user satisfaction from e-government services: lessons from Jordan. Government Information Quarterly, 30(3), 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.03.001.

Bailey, J. E., & Pearson, S. W. (1983). Development of a tool for measuring and analyzing computer user satisfaction. Management Science, 29(5), 530–545. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.29.5.530.

Bansal, G., Zahedi, F., & Gefen, D. (2008). The moderating influence of privacy concern on the efficacy of privacy assurance mechanisms for building trust: a multiple-context investigation. ICIS 2008 Proceedings - Twenty Ninth International Conference on Information Systems, Paris, France, 1–7.

Bhattacherjee, A. (2001). Understanding information systems continuance: an expectation-confirmation model. MIS Quarterly, 25(3), 351–370. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250921.

Boakye, K., Prybutok, V., & Ryan, S. (2012). The intention of continued web-enabled phone service usage: a quality perspective. Operations Management Research, 5(1–2), 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-012-0062-1.

Carter, L., & Weerakkody, V. (2008). E-government adoption: A cultural comparison. Information Systems Frontiers, 10(4), 473–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-008-9103-6.

Chang, H. H. (2010). Task-technology fit and user acceptance of online auction. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 68(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2009.09.010.

Chang, Y., Zhu, D., & Wang, H. (2011). The influence of service quality on gamer loyalty in massively multiplayer online role-playing games. Social Behavior and Personality, 39(10), 1297–1302. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2011.39.10.1297.

Chen, S. C. (2012). To use or not to use: understanding the factors affecting continuance intention of mobile banking. International Journal of Mobile Communications, 10(5), 490–507. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMC.2012.048883.

Chong, A. Y. L. (2013). Understanding mobile commerce continuance intentions: an empirical analysis of Chinese consumers. The Journal of Computer Information Systems, 53(4), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2013.11645647.

Chung, N., & Kwon, S. J. (2009). The effects of customers’ mobile experience and technical support on the intention to use mobile banking. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(5), 539–543. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2009.0014.

Crowe, M., Tavilla, E., & McGuire, B. (2015). Mobile banking and mobile payment practices of US financial institutions: results from 2014 survey of FIs in Five Federal Reserve Districts. 1-66.

Dai, H., Hu, T., & Zhang, X. (2014). Continued use of mobile technology mediated services: a value perspective. The Journal of Computer Information Systems, 54(2), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2014.11645690.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: a comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982–1003. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982.

Delone, W. H., & Mclean, E. R. (2003). The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: a ten-year update. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(4), 9–30.

Dhar, S., & Varshney, U. (2011). Challenges and business models for mobile location-based services and advertising. Communications of the ACM, 54(5), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1145/1941487.1941515.

Dharmesti, M., & Nugroho, S. (2013). The antecedents of online customer satisfaction and customer loyalty. Journal of Business and Retail Management Research, 7(2), 57–68.

Fiserv (2012). Breaking the mobile banking glass ceiling: five factors will drive consumer adoption. Fiserv White Paper, 1–7. https://www.fiserv.com/resources/mobile-banking-adoption.aspx. Accessed May 2016.

Fiserv (2014). Exceeding the mobile adoption benchmark: effective strategies for driving greater adoption and usage. Fiserv White Paper, 1–10. https://www.fiserv.com/resources/Mobile-Adoption-Strategies-White-Paper-August-2014.pdf. Accessed May 2016.

Fornell, C., Johnson, M. D., Anderson, E. W., Cha, J., & Bryant, B. E. (1996). The American customer satisfaction index: nature, purpose, and findings. Journal of Marketing, 60(4), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251898.

Hong, W., & Thong, J. (2013). Internet privacy concerns: an integrated conceptualization and four empirical studies. MIS Quarterly, 37(1), 275–298. 10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.1.12.

Hong, S. J., Thong, J. Y., & Tam, K. Y. (2006). Understanding continued information technology usage behavior: a comparison of three models in the context of mobile internet. Decision Support Systems, 42(3), 1819–1834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2006.03.009.

Hsu, J. S. (2014). Understanding the role of satisfaction in the formation of perceived switching value. Decision Support Systems, 59, 152–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2013.11.003.

Hsu, M. H., Yen, C. H., Chiu, C. M., & Chang, C. M. (2006). A longitudinal investigation of continued online shopping behavior: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 64(9), 889–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2006.04.004.

Joo, Y. J., Lim, K. Y., & Kim, E. K. (2011). Online university students’ satisfaction and persistence: examining perceived level of presence, usefulness and ease of use as predictors in a structural model. Computers in Education, 57(2), 1654–1664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.02.008.

Keith, M. J., Thompson, S., Hale, J., & Lowry, P. B. (2013). Information disclosure on mobile devices: re-examining privacy calculus with actual user behavior. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 71(12), 1163–1173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2013.08.016.

Kim, H.-W., & Gupta, S. A. (2009). Comparison of purchase decision calculus between potential and repeat customers of an online store. Decision Support Systems, 47(4), 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2009.04.014.

Laumer, S., Eckhardt, A., & Trunk, N. (2010). Do as your parents say?—Analyzing IT adoption influencing factors for full and under age applicants. Information Systems Frontiers, 12(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-008-9136-x.

Lee, T. M., & Park, C. (2008). Mobile technology usage and B2B market performance under mandatory adoption. Industrial Marketing Management, 37(7), 833–840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.02.008.

Lella, A. (2015). Smartphone subscriber market share. comScore, Inc. http://www.comscore.com/Insights/Market-Rankings/comScore-Reports-January-2015-US-Smartphone-Subscriber-Market-Share.

Lin, H. F. (2011). An empirical investigation of mobile banking adoption: The effect of innovation attributes and knowledge-based trust. International Journal of Information Management, 31(3), 252–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2010.07.006.

Lu, J. (2014). Are personal innovativeness and social influence critical to continue with mobile commerce? Internet Research, 24(2), 134–159. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-05-2012-0100.

Park, J. (2014). The effects of personalization on user continuance in social networking sites. Information Processing and Management, 50(3), 462–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2014.02.002.

Rejikumar, G., & Ravindran, S. (2012). An empirical study on service quality perceptions and continuance intention in mobile banking context in India. Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce, 17(1), 1–22.

Setterstrom, A. J., Pearson, J. M., & Orwig, R. A. (2013). Web-enabled wireless technology: an exploratory study of adoption and continued use intentions. Behaviour & Information Technology, 32(11), 1139–1154. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2012.708785.

Shen, Y.-C., Huang, C.-Y., Chu, C.-H., & Hsu, C. T. (2010). A benefit-cost perspective of the consumer adoption of the mobile banking system. Behaviour & Information Technology, 29(5), 497–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/01449290903490658.

Sutanto, J., Palme, E., Tan, C., & Phang, C. W. (2013). Addressing the personalization-privacy paradox: an empirical assessment from a field experiment on smartphone users. MIS Quarterly, 37(4), 1141–1164. 10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.4.07.

Taylor, S., & Todd, P. A. (1995). Understanding information technology usage: a test of competing models. Information Systems Research, 6(2), 144–176. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.6.2.144.

Thong, J. Y., Hong, S., & Tam, K. Y. (2006). The effects of post-adoption beliefs on the expectation-confirmation model for information technology continuance. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 64(9), 799–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2006.05.001.

Thongpapanl, N., & Ashraf, A. (2011). Enhancing online performance through website content and personalization. The Journal of Computer Information Systems, 52(1), 3–13.

Tomovska-Misoska, A., Stefanovska-Petkovska, M., Ralev, M., & Krliu-Handjiski, V. (2014). Workspace as a factor of job satisfaction in the banking and ICT industries in Macedonia. Serbian Journal of Management, 9(2), 159–171.

Tong, C., Wong, S., & Lui, K. (2012). The influence of service personalization, customer satisfaction and switching cost on e-loyalty. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 4(3), 105–114.

Wang, K., & Groth, M. (2014). Buffering the negative effects of employee surface acting: the moderating role of employee-customer relationship strength and personalized services. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(2), 341–350. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034428.

Wang, Y.-S., Lin, H.-H., & Luarn, P. (2006). Predicting consumer intention to use mobile service. Information Systems Journal, 16(2), 157–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2575.2006.00213.x.

Xu, H., Luo, X., Carroll, J. M., & Rosson, M. B. (2011). The personalization privacy paradox: an exploratory study of decision making process for location-aware marketing. Decision Support Systems, 51(1), 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2010.11.017.

Yuan, S., Liu, Y., Yao, R., & Liu, J. (2016). An investigation of users’ continuance intention towards mobile banking in China. Information Development, 32(1), 20–34.

Zhang, N., Guo, X., & Chen, G. (2011). Why adoption and use behavior of IT/IS cannot last?—Two studies in China. Information Systems Frontiers, 13(3), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-010-9288-3.

Zhang, R., Chen, J., & Lee, C. (2013). Mobile commerce and consumer privacy concerns. The Journal of Computer Information Systems, 53(4), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2013.11645648.

Zhou, T. (2012). Examining mobile banking user adoption from the perspectives of trust and flow experience. Information Technology and Management, 13(1), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10799-011-0111-8.

Zhou, T. (2013). An empirical examination of continuance intention of mobile payment services. Decision Support Systems, 54(2), 1085–1091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.10.034.

Zhou, T. (2014). Understanding the determinants of mobile payment continuance usage. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 114(6), 936–948. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-02-2014-0068.

Zhou, T., & Liu, Y. (2014). Examining continuance usage of mobile banking from the perspectives of ECT and flow. International Journal of Services, Technology and Management, 20(4/5/6), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSTM.2014.068844.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the two bank representatives who helped in distributing the survey and collecting the data. We thank them, too, for providing us with actual usage data on MB services from the system log data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Albashrawi, M., Motiwalla, L. Privacy and Personalization in Continued Usage Intention of Mobile Banking: An Integrative Perspective. Inf Syst Front 21, 1031–1043 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-017-9814-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-017-9814-7