Abstract

In this paper, we examine the effects of investments in Information Technology (IT) on the long term business values of organizations. The regression discontinuity design is used in this research to examine eight hundred and ten IT investment announcements collected from the period 1982–2007. Our results found that press releases can affect the market value of a firm by possibly providing investors with a better idea of a firm’s current and future operations and strategy. On the other hand, these press releases also appear to attract more transient investors. The attraction of transient investors likely suggests the market believes the IT investing firm is serious about its potential for growth and expansion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Information systems (IS) researchers have questioned the added value of the billions of dollars spent by firms on information technology (IT) over the past thirty years and the business value of IT has long been a subject for research and intensive debate (Li et al. 2009; Lui et al. 2015). In spite of this uncertainty, IT spending steadily increased over the years. According to Gartner Group, worldwide IT spending reached 3.6 trillion dollar in 2012, and the spending is expected to continue to grow by 5.2% in 2013 (Gartner 2013). With the significant amount of money spent on information technology, companies are often challenged whether such investments will result in business value (Mithas and Rust 2016).

The results of studies that have examined the business value of information technology (BVIT) have been mixed. Early BVIT studies sought to explain the “productivity paradox,” the fact that intensive IT expenditures during the 1980’s did not appear to result in significant increases in firm productivity at that time (Erik Brynjolfsson 1993; Dos Santos et al. 1993). Subsequent studies suggested that the effects of IT investments on firm productivity took much longer to realize. This was supported by research showing that many firms with substantial investments in IT reported significant increases in firm value after 1991 (E. Brynjolfsson and Hitt 1996).

Later BVIT studies focused on firm and technology-specific characteristics to explain the valued added from investments in IT. For example, several researchers suggested that only small, healthy firms (regardless of industry type) (see Chatterjee et al. 2001; Im et al. 2001) would experience an increase in firm value as a result of IT investments (Hayes et al. 2000; Im et al. 2001). When researchers examined type of industry more closely, it was found to make a difference, especially when considering the strategic role of the technology within the firm and industry (Dehning et al. 2003). Several BVIT researchers also suggested that the type of technology affected the impact of IT investments on the value of the firm - both the specific characteristics of IT investments (Agrawal et al. 2006) and how those investments were implemented (Hendrick et al. 2007; Khallaf and Skantz 2007; Oh et al. 2006a; b; Thiesse et al. 2009) affected firm value. Hendricks et al. (Hendrick et al. 2007) in their study on enterprise systems implementations announcements, found mixed results in the types of IT implementations (e.g. Enterprise Resource Planning , Customer Relationship Management, and Supply Chain Management Systems) with regards to stock price performance and profitability. While some BVIT studies have examined the long-term effect of IT investments (using return on assets, return on investment and return on equity), these studies focused on overall and not specific investments in IT (E. Brynjolfsson and Hitt 1996). These BVIT studies led some to examine whether the impact of IT investments is lagged over even longer periods of time. Although Hendricks et al. (Hendrick et al. 2007) examined different types of IT enterprise systems investment, their study was conducted on announcements within a 5 year period. Unlike prior long-term BVIT studies that focused on overall firm IT investments (i.e. IT budgets, IT spending), this research complements the current BVIT literature by examining the long-term effect of different, specific IT investments on firm value.

Researchers have examined the effect of announcements of IT investments by examining changes in short-term cumulative abnormal returns (CARs). One limitation of this approach is that it can capture the short-term effect but not the longer-term overall added value of these IT investments. Firms invest large amounts of capital on IT, and it is fair to question whether these firms receive their investment’s worth. This research uses the regression discontinuity methodology to address the question, do specific investments in IT contribute to firm value?

The regression discontinuity design is used in this research to examine the change in a firm’s long-term market value as a result of specific IT investments. Eight hundred and ten IT investment announcements were collected from the period 1982–2007. This allows us to cover major phases of IT investments from the introduction of IT to organizations, to the growing period of IT investments in the 1990s before the dot-com bubble resulting in significant drop in the investments in IT before the recovery and continual growing phase of the mid-2000s (Asekome and Agbonkhese 2015). Firm-level performance data prior to the announcement are assigned to the control group and data after the announcement are assigned to the treatment group. This permits a direct comparison of the change in the market model after the announcement to see how a specific IT investment affects the long-term market value of the firm.

This research contributes to the IS research in three meaningful ways. First, this research uses the regression discontinuity design to examine the long-term effect of specific IT investments on firm performance. This approach addresses limitations of other event study methodologies, especially the small event-window. The regression discontinuity design, on the other hand, tests the effect of the event by comparing the changes in regression lines before and after the event regardless of the duration of the event window.

The second contribution of this research is that it examines the long-term impact of specific IT investments. As noted, because of restrictions related to the methodologies used (e.g. inability to isolate the long term IT effect), most prior BVIT studies have focused on short-term event windows. Having a short-term focus provides researchers with only a partial explanation of the value of IT investments, and therefore may be misleading. For example, some IT investments might increase the short-term but not the long-term value of the firm (the reverse might also be true). Thus, examining both the short and long-term impact of IT investments on firm value is essential to better understanding the nomological network within which IT valuation exists. Only by examining the short and long-term impact of IT investments can we meaningfully understand the true impact of investments in IT on firm market value.

Lastly, by examining over a large period of time, we are able to cover the different types of IT from the 1980s to 2000s. For example, the 1980s saw firms investing in systems such as Electronic Data Interchange (EDI), while during the 1990s, firms spent heavily on electronic business systems (Chou et al. 2004; Chong and Bai 2014), and the late 1990s and early 2000s was the dot-com bubble (Panko 2008; Chan 2014) which may bring negative association between IT investments and firms’ business value.

2 Business value of information technology

IT investments are expected to positively affect business outcomes important to firms either directly or indirectly. Direct effects have a positive impact on major operational and financial business activities. Indirect effects are not as easily measurable. However they can have an impact on business operations. Unfortunately, the effects of IT investments are not always quickly apparent; they often take time to develop.

Studies have examined IT spending by manufacturing firms where results similar to those for service firms obtained. For example, (Loveman 1994) examined the relationship between firm productivity and IT spending using the ratio of the contribution of IT capital to output and found the ratio remained flat over time. (Barua et al. 1995) re-examined Loveman’s data using intermediate measures of productivity (e. g., capacity utilization, inventory turnover, quality, relative price and new product introduction). Although they found that firm productivity did improve on three of their measures, there was no improvement on return on sales and market share.

IT investments may take several months or even years to positively affect firm value due to the learning curve associated with the technology. Furthermore, firms may need to restructure their business processes to better fit the technology, which may take some time, and the scope of the technology may also create a problem, especially if the firm does not completely understand the likely impact of the technology or provide the training necessary to effectively use the technology.

Many BVIT studies use accounting metrics to measure IT investing firms’ financial performance. Common metrics used in early BVIT studies included return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), and return on investment (ROI) (Alpar and Kim 1990; E. Brynjolfsson and Hitt 1996; Li and Ye 1999; Mahmood and Mann 1993; Rai et al. 1996; Tam 1998; Weill 1992). ROA, ROE, and ROI are measures of firm profitability (Alpar and Kim 1990) that are highly correlated with alternative measures of profitability (Weill 1992). BVIT studies typically examine changes in these variables after an IT investment to better determine the effect of the adoption. Early studies found little or no change in these ratios at the macro (i.e., industry) level (Alpar and Kim 1990; Mahmood and Mann 1993; Weill 1992). However, as BVIT studies began to focus on firm and technology specifics, some researchers reported positive changes in these profitability ratios (Erik Brynjolfsson and Hitt 1996; Li and Ye 1999; Tam 1998). Studies focusing on firm-specific characteristics (e.g., management structure, corporate strategy, competition, etc.) allowed researchers to better isolate and measure more concisely changes in ROA, ROE and ROI (Li and Ye 1999). However, a weakness of these accounting metrics is that they only capture historical financial information (Mitra 2005).

The BVIT literature has also used several less common metrics including: risk (Dewan and Fei 2007), earnings volatility (Kobelsky et al. 2008a; b) and analysts’ forecasts (Dehning et al. 2006). For example, VBIT research has shown that the risk premium increases due to IT investments (Dewan and Fei 2007). Similarly, (Dehning et al. 2006) report that investments in IT increase analysts’ forecasting error due to the increase in information risk associated with the IT’s characteristics.

Based on Table 1, our paper has extended and differentiated our study by focusing on the investment of IT on the long term business values of firms. Our data covered a period of 27 years which have provide clear evidence and understanding of the long term business values of IT investments. Our study also applied the regression discontinuity design methodology to examine the long-term effects of IT investment announcements. By employing the regression discontinuity design method, it allows us to better assess the impact of IT investments and at the same time address many of the statistical constraints associated with other techniques (e.g., assumptions related to randomization).

3 Theory and hypotheses development

Our theoretical development of this paper is based on Roztocki and Weistroffer (2015)‘s research in which they applied the Signaling Theory to explain stock reactions to enterprise integration technology. Although our paper examines market’s reactions towards IT investments rather than specific enterprise integration technology, we believe Signaling Theory is also relevant given that this research has employed an event study approach similar to Roztocki and Weistroffer (2015)‘s paper. Signaling theory examines the communications between the different participants who have various accesses to information and with different interests. When the sender communicates the information to the receiver, the receiver has to decide how to interpret the information (or signal) (Roztocki and Weistroffer 2015). The sender would send the information that will be received in a way that is advantageous to the sender, while the receiving party interprets the information in order to gain accurate information about the sender (Roztocki and Weistroffer 2015). Signaling theory is applied in this study by treating the signal as the event (i.e. IT investments). The sender in our research is the releaser of the announcement while the receiver is the potential investor that interprets the announcements and takes the necessary actions. When the IT investment announcement is interpreted as a prediction of a substantial change in a company’s future cash flow, the investor will react to the announcement by buying or selling the stock. For more detailed explanation of the application of signaling theory to event study, please refer to Roztocki and Weistroffer (2015).

Firms that invest in technology may also gain a competitive advantage over their competitors by adopting technologies that fit well the firm’s long-term goals and mission. Although the technology itself (i.e. its processes, standards, skill sets, etc.) may be replicable by its competitors, the technology is much more difficult to imitate when the technology is matched with the specific needs of a particular firm (Chatterjee et al. 2002).

Developing and implementing a successful technology investment can take a long time and involves a significant amount of capital, human and other resources. While the success of the investment may not be realized as quickly as expected or meet the original estimated budget, in the end most technology investments are deemed successful by their adopters. For example, the Standish Group (The Standish Group International 2009) reports that over time, more and more technology investments have been implemented successfully. Its survey of 9236 projects reported that from 1994 to 2000, successful technology adoptions increased from 16% to 28% and challenged adoptions remained about the same (from 53% to 49%). The report defines a successful project as one that is completed on time and within budget with all expected technological features implemented. A challenged project is one that is completed later than expected, over budget, and with less than the expected technological features implemented. While it may be alarming that roughly half of all projects were over budget and delayed, even these projects were implemented with some degree of success. As noted by (Compass 2009), most executives believe that in the end their firm’s technological investments improved firm performance, competitiveness, and cost management.

In the long run, investments in IT (even partially successful ones) should have a positive effect on firm value that would be reflected in Jensen’s alpha. Thus, if Jensen’s alpha increases after the announcement of an investment in technology, investors should perceive the IT investment as value adding. Thus, hypothesis one is:

-

H1: Firms that announce investments in information technology will experience a positive shift in the abnormal rate of return (i.e. a positive shift in the alpha coefficient).

Transient investors typically search for news announcements that suggest an increase in a stock’s momentum as a result of changes in firm growth due to development and expansion (Serwer 1997) or changes in other important firm information including investments in IT (Bushee and Noe 2000). For example, firms that invest in transformational technologies are often planning an overhaul of their business that leads to substantial future growth (Tanriverdi and Ruefli 2004). Thus, we would expect IT investments to attract transient investors in the short-term while attracting other institutional investors in the long-term. Thus, hypothesis two is:

-

H2: Firms that announce investments in information technology will experience positive shifts in relative volatility (i.e. a positive shift in the beta coefficient).

4 Regression discontinuity

The regression discontinuity design (RDD), a pre-post two-group design used to measure the causal and treatment effects within different groups, is used to test the hypotheses in this research. While RDD has had little exposure in the business literature, it has been used extensively in the psychology and education literatures. Interestingly, a number of recent studies in economics have used RDD as an alternative method for examining causal effects for non-experimental data (Cook 2008; Imbens and Lemieux 2008).

(Thistlethwaite and Campbell 1960) argue that RDD is preferable to the ex-post design because RDD does not require the random assignment of subjects to experimental and control groups. The process of assigning subjects to groups depends on a subject’s score on a relevant assignment variable (Campbell and Stanley 1963).

This research uses RDD to examine the effect of firm announcements of specific information technology investments (i.e., the treatment) on the business valuation of the firm. This assumes that firms do not make investments in IT randomly (Kobelsky et al. 2008a; b).

RDD is the preferred methodology for this research because it does not require strict statistical compliance (i.e. sample size) except for a clearly, defined cutoff between the control group and the treatment group for the assignment variable (Battistin and Rettore 2002). In addition, the assignment variable does not have to be correlated with the dependent variable and more than one assignment variable can be used (Shadish et al. 2002). Finally, RDD does not require the sample to randomize the assignment of IT investing firms to treatment and control groups (unlike OLS where we assume the sample is randomly collected) (Campbell and Stanley 1963). These firms likely share similar characteristics, including large financial resources, high institutional investor followings and complex operations (Dehning et al. 2006; Khallaf and Skantz 2007).

The requirements to use RDD are quite simple. First, the cutoff point must be clearly defined. In this study, the cutoff point is the date of the IT investment announcement. Second, the cutoff point must clearly separate the data into two groups: control and treatment groups. For this study, the control group is the time prior to the IT announcement and the treatment group is the time after the IT announcement. Third, when selecting the cutoff point, there cannot be any contemporaneous factors associated with the cutoff score. For example, when the firm announces an investment in IT there cannot be an earnings or dividend announcement on the same date. Finally, both the treatment and control groups must have complete sets of data.

While prior studies have typically used a small event window (often ten to forty days) to capture the firm’s CAR, this study uses RDD to capture the firm’s CAR using a long-term event window. RDD is acceptable under these circumstances as long as there are no discontinuous changes in the firm’s behavior (e.g. the firm’s industry membership changes as a result of the IT investment).

This study estimates the impact of IT investment announcements on the business value of the firm using the CAPM model in regression form based on Jensen’s modifications (Eq. 1):

Where

-

Rit = return for firm I at time t,

-

Rft = risk free rate at time t,

-

RMt = market return at time t.

-

αi is Jensen’s alpha, a risk adjusted performance measurement capturing excess returns,

-

βiM = captures the relative volatility of the individual firm’s rate of return compared to the market’s rate of return.

IT investment announcements were grouped based on the specific type of IT as well as other firm and performance-related characteristics. The grouping criteria are described below.

4.1 Additional control variables

The IT literature suggests that not all technologies are equal and that different technologies provide different financial benefits to a firm. This section describes the individual technologies and IT strategies that are used in this study.

IT strategic role

IT Strategic Role is applied to the firm. These strategic roles include automate, informate, or transformate. To code the IT strategic role for each announcement, three recognized scholars in the area of IT strategy were independently asked to indicate the role that IT served in the particular announcement – whether automate, informate, or transformate using the coding rules established by Dehning et al. [24]. The inter-rater reliability was 0.83, and all differences were reconciled as a group.

4.2 Performance metrics

This section describes the performance metrics used to group the IT investment announcements for testing. The performance metrics described below are often used to measure the short-term effect of IT investments. However, these metrics were used in this study to determine whether firms that show a short-term benefit from IT investments maintain the benefit over a longer period of time.

-

Return on Sales (ROS) – ROS is net income (before interest and taxes) divided by sales. This ratio is used to evaluate the firm’s operating efficiency. Investors use ROS to assess how much profit the firm generates per dollar of sales.

-

Return on Assets (ROA) – ROA equals net income divided by total assets. It signals to investors how well the firm’s assets are managed to generate profits.

-

Return on Equity (ROE) – ROE is net income divided by shareholders equity and is expressed as a percentage. ROE tells investors how well shareholder investments are managed by the firm to generate profits.

4.3 Firm characteristics

Finally, IT investment announcements are grouped based on firm characteristics. Firm characteristics will likely have an effect on the results because not all firms that make investments in IT share similar firm characteristics. These characteristics have often been used as control variables in prior research studies and are used similarly in this study.

-

Size – Size is defined as the natural log of the firm’s total assets for the year of the IT investment announcement. The inclusion of size as a control variable has produced mixed results in prior studies. For example, while (Im et al. 2001) reported that small firms are much more sensitive to IT investments, their results were not replicated in other studies.

-

Industry – Whether the firm is a member of the financial industry is examined for the sake of consistency. This was done in spite of the fact that prior studies have not found that being a member of the financial industry affects a firm’s return (Chatterjee et al. 2002; Davis et al. 2003; Dos Santos et al. 1993; Im et al. 2001; Oh et al. 2006a; b). Thus, if the firm is a member of the financial industry it is coded as a “1”; otherwise it is coded as “0”.

-

Quick Ratio (slack) – The quick ratio equals the firm’s current assets less any inventories, divided by the firm’s current liabilities. The quick ratio is a proxy for slack.

4.4 IT investment announcements

The IT investment announcements used in this research included 238 announcements collected by(Im et al. 2001), 96 announcements collected by (Chatterjee et al. 2001), 112 additional unique announcements collected by (Chatterjee et al. 2002), 150 announcements collected by Hunter (Hunter 2003), and 85 ERP announcements that were collected by (Hayes et al. 2001). After both duplicate and non-locatable announcements were removed, a total of 532 existing IT investment announcements remained.

A total of 287 additional IT investment announcements were collected using the procedure described by (Im et al. 2001) and (Duan et al. 2009): using pre-selected keywords, the Lexis Nexus and Business and Industry databases were searched for IT investment announcements during the period 1982–2007. We selected the early 1980s as the starting time period of our study as this is the time period when the IBM PCs, IBM PC Clones and Apple computers were introduced and organizations started to invest in computers and IT as a result of more affordable computers. The time period selected in our study also include the emergence of the Internet as well as the pre and post Internet Bubble period. The pre-selected keywords included: hardware, software, ecommerce, chief investment officer, enterprise resource planning (ERP), infrastructure, and IT outsourcing. The additional requirements for the inclusion of the 287 new announcements where:

-

The firms investing in IT were traded only on the NYSE, NASDAQ, and AMEX.

-

No potentially confounding events took place within three days surrounding the announcement period (e.g. earnings, dividends, mergers/acquisition, etc.)

-

Financial information about the IT investing firms was available from CRSP and Compustat.

Table 2 provides a summary of the announcements by source and Table 3 provides a summary of the announcements by year. After duplicate and non-locatable announcements were removed, the combined total of usable existing and new IT investment announcements was 810.

Daily firm and market returns were collected from the CRSP database. The one-month Treasury bill rate was used as the risk-free rate. Each firm’s financial and other characteristics were taken from the Research Insight Compustat database.

4.5 Summary statistics

Table 4 presents descriptive statistics for the study variables. As indicated, the average firm return is smaller than the average market return and firm returns vary slightly more than market returns (standard deviation of firm return = .0298; market return = .0071). Thus, it appears that alpha and beta did not change much across the time period surrounding the IT investment announcement. The average size of the firms included in the study is large: average firm sales = $14.0 billion; average number of employees =75,000; average (median) total assets = $9.4 ($0.669) billion and average (median) total debt = $10.2 ($1.01) billion.

4.6 Regression discontinuity analysis

The general linear model (GLM) was used to analyze the shifts in alpha and beta related to firm announcements of IT investments (see Eq. 2).

The dependent variable in this analysis is the firm’s daily return adjusted for the daily risk-free rateRit − Rft. The independent variables are the market’s daily return adjusted for the daily risk-free rate Rmt − Rft henceforth labeled as market RMt − Rft, a timing variable (prepost), signified as a 1 if the observation occurred after the event date and a zero if before, and an interaction term [(Rmt − Rft) ∗ prepost] [(RMt − Rft) ∗ prepost] involving adjusted market returns and the timing variable.

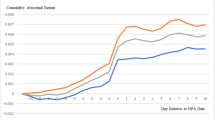

The results of the regression discontinuity analysis are presented in Table 5: αi is the Jensen’s alpha for the overall model and β1iM the overall model’s beta1.Footnote 1 The alpha and beta shifts, β3it and β2itβ3it, respectively, measure the changes in alpha and beta at the post-IT investment announcement discontinuity point.

According to Hypothesis One, there will be a positive shift in a firm’s alpha after the firm announces an investment in IT. As indicated in Table 5, there is a small, positive alpha shift β3it〚(β3)〛↓it, p = .0386) after an IT investment announcement that supports Hypothesis One β3it. This suggests that investors can increase their returns by investing in firms that invest in IT even though this would have only a small effect on the size of their portfolios.

According to Hypothesis Two, there will be a positive shift in a firm’s beta after the firm announces an IT investment. As shown in Table 5, the model supports a positive beta shift after the IT investment announcement (β2it, p = .00003). Thus, although investors who invest in firms that invest in IT would increase their risk, over the long term in a growing market investor returns would also increase.

4.7 Additional analyses

Additional analyses, including the timing of the announcement (pre or post productivity paradox), firm size, IT intensity and IT strategic role, were performed to determine the effect of these variables on the observed alpha and beta shifts in the overall model. This section describe these additional analyses.

4.8 Timing of the IT investment announcement (pre or post productivity paradox)

The existing BVIT literature suggests that firms did not benefit from IT investment investments until after 1992 (E. Brynjolfsson and Hitt 1996). This phenomenon was labeled the “productivity paradox”. It is important to examine the productivity paradox because IT investment announcements prior to 1992 may reduce the size and significance of alpha and beta shifts after 1992. To test for the productivity paradox affect, firms are classified as pre and post 1992 by the year of the announcement.

Table 6 presents the results of the regression discontinuity analysis of IT investment announcements made pre (Panel A) and post (Panel B) 1992. Pre-Productivity Paradox results indicate that neither alpha nor beta shifts occurred prior to 1992 (p = .0592 and .1851 respectively). The Post-Productivity Paradox results indicate there were positive shifts in both alpha (.0647, p < .0001) and beta (.0003, p = .0085) after 1992. The post-1992 increase in alpha suggests that the returns of investors who invest in firms that announced investments in IT after 1992 will increase (E. Brynjolfsson and Hitt 1996). However, the magnitude of the increase will be very small. The post 1992 increase in beta suggests IT investment announcements attract more investor types, such as transient investors (Ke and Petroni 2004).

4.8.1 Firm size

Prior BVIT studies have also examined the effect of firm size on shifts in alpha and beta. For example, (Im et al. 2001) and (Dehning et al. 2003) reported that small firms often have lower stock prices and higher volatility than large firms because small firms have the ability to incorporate technology quickly. On the other hand, results reported by (Chatterjee et al. 2002) and (Oh et al. 2006a; b) did not support a firm-size effect.

Firm size is defined as the total asset value of the firm at the time of its IT investment announcement. The median asset value of the firms in the study ($670 million) was used to differentiate between large and small firms. The regression discontinuity results for firm size are presented in Panels A and B in Table 6. These results suggest that firms with total assets above $670 million experience a positive alpha shift (p = .0493) while firms with total assets below $670 million experience a positive beta shift (p = .0002). The results for firms with total assets below $670 million are not unexpected because small firms tend to be more volatile (Bushee and Noe 2000; Im et al. 2001). In additions, investors may believe smaller firms will generate greater future cash flows from their IT investments than larger firms will (Nagm and Kautz 2008). The positive alpha shift for firms with total assets above $670 million suggests that the returns of investors who invest in large firms that invest in IT will increase. However, the magnitude of the increase will be small.

4.8.2 IT intensive firms

(Mittal and Nault 2009) note that some firms are more IT intensive in their operations due to the nature of their business and industry; as IT intensive firms have a greater need to maintain industry standards and competitiveness. The IT Intensity of firms can be estimated based on the business sector in which the firm is classified. Absent several exceptions (e.g., firms in the chemical and petroleum or the electrical and controlling equipment industries), manufacturing firms are generally considered low in IT intensity (Mittal and Nault 2009). Firms are classified as highly IT intensive by their SIC code and membership in the following industries: transportation, retail, financial and service. All remaining industries are classified as low IT intensive. Tables 7 and 8 presents the study results for low and high IT Intensive firms.

The results show that high IT intensive firms experience both significant alpha and beta shifts, although low IT intensive firms experience no effect. The beta shift suggests that high IT intensive firms may attract greater numbers of transient investors than firms low in IT intensity (Ke and Petroni 2004; Oh et al. 2006a; b; Oh et al. 2006a; b). The significant Jensen’s alpha suggests that the returns of investors who invest in firms high in IT intensity will increase. However, once again, the magnitude of the increase will be small.

5 Key findings

Several interesting findings emerged from this study. First, prior to a firm’s IT investment announcement, the average firm’s Jensen’s alpha is −.0006 (suggesting investors would realize a 0.06% reduction in their returns if they invested in the firm rather than the market). Second, prior to its IT investment announcement the average firm is riskier than the market, as indicated by the average firm beta of 1.18 (suggesting that the average firm is 18% more volatile than the market). Following a firm’s IT Investment announcement, however, both alpha and beta shifted positively (alpha shifted by 0.0002, p = 0.0386, while beta shifted by 0.0472, p = .0003). These results support the finding that in general, IT investments positively affect the value of the firm.

Because the average firm’s alpha increased after its IT announcement, investors benefited long term from the firm’s IT investment through an increase in their excess returns. Unlike earlier short-term event studies that found no overall effect on firm value (Dos Santos et al. 1993; Im et al. 2001; Oh et al. 2006a; b), the current results suggest that (Armstrong and Sambamurthy 1999; Bharadwaj et al. 1999) IT adds value in the long term. Given the fact that investments in IT can take years to implement successfully (Armstrong and Sambamurthy 1999; Bharadwaj et al. 1999), it should not be surprising that the related financial benefits are also more likely to materialize in the long term rather than short term.

The overall positive beta shift suggests firms that invest in IT are perceived as riskier investments over the long-term. However, during the time period examined in this study (1982–2007) the market displayed bull characteristics [(when stock prices are rising or are expected to rise based on optimism, investor confidence and expectations that strong results will continue (Ritter and Warr 2002). Investors’ expected returns increase during a bull market, which is likely due to an increase in risk because of bloated investor expectations. On the other hand, this beta increase may indicate an attraction of a different type of investor: transient investors. Transient investors are attracted to firms that display expansion and growth characteristics and to stocks that have a change in momentum. IT investments provide firms these opportunities, and as observed in the beta shift, it appears transient investors are attracted to IT investing firms.

Another possible explanation for the positive beta shift is that an IT investment increases a firm’s leverage (represented by d/e). Eq. 3 represents the structure of the firm’s beta based on the cost of capital model (Brealey et al. 2007).

Where d = firm debt, e = firm equity, and t = marginal tax rate.

As firms invest in technology, risk increases as a result of the uncertainty associated with the future benefits of IT investments (Dehning et al. 2006). Moreover, firms often fund their large capital purchases through additional borrowing. As borrowing increases, a firm’s cost of capital will increase as a result of the increase in beta. Thus, as a firm invests in IT, its debt increases over time, which in turn increases the firm’s beta.

To better understand the long-term benefits of IT investments, this study examined the alpha and beta shifts for the influence of time, firm, and technology characteristics. Early studies examining the affect of IT investments on firm value did not find any until after 1992 and, has been termed the “productivity paradox” (E. Brynjolfsson and Hitt 1996; Erik Brynjolfsson 1993). This study tests alpha and beta shifts for the productivity paradox. During the productivity paradox (prior to 1992), IT investing firms display a negative Jensen’s alpha shift (−.0003; p < .0592) while after the productivity paradox these firms display a positive alpha shift (.0003; p < .0085). This alpha shift suggests that investors did not view IT investments as value adding until after 1992. On the other hand, the pre-productivity paradox beta shift was not significant while the post-productivity paradox beta shift was positive (.0647; p < <.0001). This is likely due to the fact that transient investors invested more heavily in IT investing firms after 1992.

The current study also examined the effect of firm size on a firm’s return. These results showed that large firms display a positive alpha shift (.0002; p < .0493) while small firms display a positive beta shift (.0764; p < .0002). The positive alpha shift suggests that investors view IT investments by large firms as value adding. The positive beta shift for small firms was not unexpected as small firms tend to have higher, more volatile growth rates, more internal changes and often display greater stock momentum, all of which increase investor perceptions of risk (Oh et al. 2006a; b). In fact, these are the same characteristics that attract transient investors, who are interested in the short-term potential associated with more volatile, smaller firms (Tanriverdi and Ruefli 2004).

Next, the current study examined the effect of a firm’s IT intensity on the firm’s return. These results showed that only high IT-intensive firms had both positive alpha (.0002; p < .0421) and beta (.0720; p < .0001) shifts. The positive alpha shift suggests that the market views IT investments as an important investment-related consideration, yet the positive beta shift suggests that high IT-intensive firms are also viewed as riskier investments.

Finally, automate, informate and transformate IT strategic roles were examined for their effects on a firm’s return. While an alpha shift was not found for firms with an Automate IT strategic role, a negative beta shift (−0.0724; p < .003) was found. In fact, firms with an Automate strategic role were the only firms to exhibit a negative beta shift, which suggests that the market views Automate IT investments as less risky. This is likely due to the fact that investors believe that Automate IT investments have little impact on a firm’s growth and this decreases the volatility of the firm’s return. As a result, firms that invest in Automate IT are also unlikely to attract transient investors.

Firms that invest in Informate IT exhibit both positive alpha (0.0002; p < 0.036) and beta (0.0584; p < 0.0005) shifts, which is consistent with the results of prior research. Investments in Informate IT are expected to increase the quantity and quality of the flow of information, which is expected to improve decision-making firm wide. This apparently attracts both non-transient investors who believe that investments in Informate IT positively impact firm growth (Verrecchia 2001) and transient investors who believe Informate IT investments increase the volatility of a firm’s return (Bushee and Noe 2000).

Interestingly, firms that invest in Transformate IT did not exhibit a shift in their Jensen’s alpha but did exhibit a positive beta shift (0.0814; p < 0.0103) that was the largest beta shift reported in this study. It appears that investors view Transformate IT investments as quite risky. This may be because Tranformate IT investments attempt to completely re-engineer a firm’s business processes/operations, a risky endeavor under most any circumstances. The increase in risk associated with Transformate IT investments also likely attracts transient investors.

6 Implications

6.1 Implications for theory

Earlier BVIT studies that examined the impact of investment announcements on firm value tended to produce non-significant results (Hendrick et al. 2007). The results reported in the current study suggest that these non-significant results are due to the short event-windows used in these earlier studies. Studies with short-term event windows provided a starting point to examining BVIT, yet a change in the short term value of a firm does not necessarily suggest its IT investments added value. For example, if a firm is installing a new inventory tracking system (and they believe it will take up to five months to be fully operational), the firm will not realize financial benefits until after the five-month period. The value adding effect would not show up until after the installation period. In this example, using a long-term event window would more likely capture the firm’s change in market value because the event window would extend beyond the investment period.

The findings of this study show that IT investments do cause alpha and beta shifts after the IT Investment announcement. Thus, this study’s results support findings reported in the finance and accounting literatures that press releases can affect the market value of a firm by possibly providing investors with a better idea of a firm’s current and future operations and strategy. On the other hand, these press releases also appear to attract more transient investors. The attraction of transient investors likely suggests the market believes the IT investing firm is serious about its potential for growth and expansion.

Unlike existing studies, this study covers IT announcements ranging from the 1980s to the mid-2000s. By including such extensive time period, we were able to take into account of the different phases of IT investments by organizations ranging from the 1980s when IT investment is still relatively new, to the 1990s which saw the emergence of the Internet and the subsequent Internet dot com bubble, and finally to the recovery from the bubble which saw firms making more careful and strategic IT investment decisions.

Theoretically, this study has employed Signaling Theory to explain stock reactions to IT investments. (Roztocki and Weistroffer 2015). Signaling theory allows us to examine the communications between the different participants who have various accesses to information and with different interests. We applied Signaling theory by treating the signal as the event (i.e. IT investments). The senders are the releasers of the announcements, while the receivers are the potential investor that interprets the announcements and takes the necessary actions. When the IT investment announcement is interpreted as a prediction of a substantial change in a company’s future cash flow, the investor will react to the announcement by buying or selling the stock.

Finally, this study introduces the regression discontinuity design methodology as an acceptable method for examining the long-term effects of IT investment announcements. Among its many advantages, RDD allows researchers to better assess the impact of IT investments absent many of the statistical constraints associated with other techniques (e.g., assumptions related to randomization). Thus, we can come to a better understanding of the BVIT phenomenon using RDD by expanding the reach of this research beyond the typical five-day event window. Moreover, the current research suggests that researchers should be able to more easily apply the RDD methodology to the study of other important business phenomenon.

6.2 Implications for practice

Carr (2003) asked “Does IT matter” and today, practitioners and researchers are still debating whether investing in IT can bring significant competitive advantage and business value to organization. The primary managerial implication of the current research is that IT investment announcements do matter to investors. Investments in IT are viewed as a major component of a firm’s operations; investors view IT investments as necessary for a firm’s success. More importantly, our study has shown that ever since organizations are being introduced more affordable PCs by IBM and IBM cloned PCs resulting in more investments in IT and until the period of post Internet Bubble, investments in IT have bring values to organizations. This finding helps decision makers such as CEOs and CIOs to take a long term and strategic approach when it comes to investing in IT. We believe that with recent work on business process reengineering, big data analytics, and organization change can ultimately converge with our results and facilitate more prescriptive implications on the deployment of IT in organizations.

However, not all IT investments have equal effects nor do all firms benefit from IT investments equally. For average, individual investors, the small alpha shifts reported in this study would likely have little major impact on their portfolios. On the other hand, large investors (e.g., managed funds and institutional investors) are likely to experience a material change in the overall value of their portfolios. Even if an alpha shift is positive and small, institutional investors would add dollars to their portfolios while individual investors would add pennies, at most. One interesting note about this study is the post announcement window start ten days after. Thus, even if the investor did not invest until days after the announcement he would still see an increase in his portfolio.

The results of this study also show that IT investment announcements have a greater effect on beta than alpha. Both individual and institutional investors may capitalize on the change in beta to grow their portfolios. For example, investors would see significant growth in their portfolios during a bull market if they traded based on the IT Investment announcements. However, institutional investors are more likely to trade on this information because they have access to the necessary financial and human resources to accomplish this successfully. Thus, a substantial portion of the portfolio growth would go to institutional investors.

Lastly, it should be noted that this study has made an empirical contribution to existing studies by examining data over 26 year periods. Although previous studies have provided inconsistent result on the impact of IT investments on business performances, by looking at data over a long period of time, we are able to examine the long term business values of IT investments.

7 Limitations

There is always the possibility the current results were driven by contemporaneous variables that influence market movements not attributable to the IT announcements. The current study controls for the effects of a number of important variables that influence market movements by examining the IT announcements using the Fama-French 3 factor model.Footnote 2 The results of this analysis were consistent with the market model.

As noted earlier, due care was also taken to isolate the IT announcements from other firm-specific events (e.g. earnings, dividends and/or acquisition announcements). Finally, a case can be made that the large sample size covering a substantial time period would most likely result in any contemporaneous firm effects being randomized across the sample firms without any material impact on the results.

Another potential limitation is that not all IT investment announcements during the time period examined were included in the analyses. The likelihood is small that IT announcements were either systematically excluded or enough were excluded to change the study results. The robustness of the study results also attests to this fact.

Another possible study limitation is that the results reported above took place during a bull market where stock prices typically increase and investors are euphoric. During a bear market, however, stock prices decrease and investor pessimism increases (as occurred over the last 20 years in Japan). As a result, transient investors are less likely to invest during a bear market because stock prices are not increasing.

8 Conclusions and future research directions

This study used regression discontinuity methodology to examine long-term shifts in alpha and beta following the announcement of specific IT investments. The analysis of 810 IT investment announcements showed that IT investments result in positive shifts in both alpha and beta overall. Additional analyses showed that positive alpha shifts occurred for high IT-intensive firms, larger firms, firms that invest in informate technologies and firms investing in IT after 1992. There were also positive beta shifts for small firms, high IT-intensive firms and firms that invest in informate and transformate technologies. Only firms that invest in automate technologies displayed negative beta shifts.

These results show that investors who invest in firms that adopt IT increase their portfolio returns. However, not all investors have the resources needed to invest wisely in IT investing firms. Thus, this raises the question of “Who is investing in IT investing firms?”

Future researchers can address this question using both experimental and market data. For example, experimental data can be used to compare the investment results of expert and novice investors. Using market data, researchers should be able to examine the buying/selling of the stock of IT investing firms surrounding an IT investment announcement. This examination should provide additional support for prior studies’ conclusions that IT investment announcements matter. This research should also provide practical insight about the types of investors who profit from investing in IT investing firms.

Another question that should be addressed in future research is “Does the timing or informational content of IT investment announcements affect investor behavior?” Because IT investment announcements are selectively written and released, it would appear that the management of IT investing firms believes they do. This examination could be best accomplished using content-analytic methods such as those developed in the behavioral sciences (Asquith et al. 2005).

Lastly, our research used data from 1982 to 2007. Future studies can extend this by examining data from 2007 onwards.

Notes

We tested the robustness of the regression model (Leamer 1983; Wooldridge 2015) found in equation 2 to determine the relative stability of the parameter estimates. To do so, we included control variables as described in Table 4 in the regression specification. When different control variables were introduced to the regression model, the overall direction and magnitude of the parameter estimates were structurally similar to the regression model found in equation 2 – which indicates the regression model is not likely to have been misspecified.

Because the CAPM oversimplifies the market by comparing excess investor returns to the market using only beta, the Fama-French 3 factor model was used to control for the impact of important variables that influence the market’s movements including differences between small and large cap stocks and value and growth stocks.

References

Agrawal, M., Kishore, R., & Rao, H. (2006). Market reactions to E-business outsourcing announcements: an event study. Information & Management, 43(7), 861–873.

Asekome, M. O., & Agbonkhese, A. O. (2015). Macroeconomic variables, stock market bubble, meltdown and recovery: evidence from Nigeria. Journal of Finance, 3(2), 25–34.

Alpar, P., & Kim, M. (1990). A microeconomic approach to the measurement of information technology value. Journal of Management Information Systems, 7(2), 55–69.

Armstrong, C., & Sambamurthy, V. (1999). Information technology assimilation in firms: the influence of senior leadership and IT infrastructures. Information Systems Research, 10(4), 304–327.

Asquith, P., Mikhail, M., & Au, A. (2005). Information content of equity analyst reports. Journal of Financial Economics, 75(2), 245–282.

Barua, A., Kriebel, C. H., & Mukhopadhyay, T. (1995). Information technologies and business value - an analytic and empirical-investigation. Information Systems Research, 6(1), 3–23.

Battistin, E., & Rettore, E. (2002). Testing for programme effects in a regression discontinuity design with imperfect compliance. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 165(1), 39–57.

Bharadwaj, A. S., Bharadwaj, S. G., & Konsynski, B. R. (1999). Information technology effects on firm performance as measured by Tobin's q. Management Science, 45(7), 1008–1024.

Brealey, R., Myers, S., & Marcus, A. (2007). Fundamentals of corporate finance (5th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Brynjolfsson, E. (1993). The productivity paradox of information technology. Communications of the ACM, 36(12), 67–77.

Brynjolfsson, E., & Hitt, L. (1996). Paradox lost? Firm-level evidence on the returns to information systems spending. Management Science, 42(4), 541–558.

Bushee, B. J., & Noe, C. F. (2000). Corporate disclosure practices, institutional investors, and stock return volatility. Journal of Accounting Research, 38(3), 171–202.

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research on teaching. Chicago: American Educational Research Association.

Carr, N. G. (2003). IT doesn’t matter. Harvard Business Review, 81(5), 41–59.

Chan, Y. C. (2014). How does retail sentiment affect IPO returns? Evidence from the internet bubble period. International Review of Economics & Finance, 29, 235–248.

Chatterjee, D., Pacini, C., & Sambamurthy, V. (2002). The shareholder-wealth and trading-volume effects of information-technology infrastructure investments. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(2), 7–42.

Chatterjee, D., Richardson, V. J., & Zmud, R. W. (2001). Examining the shareholder wealth effects of announcements of newly created CIO positions. MIS Quarterly, 25(1), 43–70.

Chong, A. Y. L., & Bai, R. (2014). Predicting open IOS adoption in SMEs: an integrated SEM-neural network approach. Expert Systems with Applications, 41(1), 221–229.

Chou, D. C., Tan, X., & Yen, D. C. (2004). Web technology and supply chain management. Information Management & Computer Security, 12(4), 338–349.

Compass (2009). Aim low: The key to IT value contribution lies deep within business processes., from http://www.compassmc.com/admin/uploaded/aim%20low.pdf.

Cook, T. D. (2008). "waiting for life to arrive": a history of the regression-discontinuity design in psychology, statistics and economics. Journal of Econometrics, 142(2), 636–654.

Davis, L., Dehning, B., & Stratopoulos, T. (2003). Does the market recognize IT-enabled competitive advantage? Information & Management, 40(7), 705.

Dehning, B., Pfeiffer, G. M., & Richardson, V. J. (2006). Analysts' forecasts and investments in information technology. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 7(3), 238–250.

Dehning, B., Richardson, V. J., & Zmud, R. W. (2003). The value relevance of announcements of transformational information technology investments. MIS Quarterly, 27(4), 637–656.

Dewan, S., & Fei, R. (2007). Risk and return of information technology initiatives: evidence from electronic commerce announcements. Information Systems Research, 18(4), 370–394.

Dos Santos, B., Peffers, G. K., & Mauer, D. C. (1993). The impact of information technology investment announcements on the market value of the firm. Information Systems Research, 4, 1–23.

Duan, C., Grover, V., & Balakrishnan, N. R. (2009). Business process outsourcing: an event study on the nature of processes and firm valuation. European Journal of Information Systems, 18(5), 442–457.

Gartner Group (2013). Gartner Says Worldwide IT Spending Forecast to Reach $3.7 Trillion in 2013, http://www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/2292815 [accessed 18th of February, 2016].

Hayes, D. C., Hunton, J. E., & Reck, J. L. (2000). Information systems outsourcing announcements: investigating the impact on the market value of contract-granting firms. Journal of Information Systems, 14(2), 109.

Hayes, D. C., Hunton, J. E., & Reck, J. L. (2001). Market reactions to ERP implementation announcements. Journal of Information Systems, 15(1), 3.

Hendrick, K. B., Singhal, V. R., & Stratman, J. K. (2007). The impact of enterprise systems on corporate performance: a study of ERP, SCM, and CRM system implementations. Journal of Operations Management, 25(1), 65–82.

Hunter, S. D. (2003). Information technology, organizational learning, and the market value of the firm. Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application, 5(1), 1–28.

Im, K., Dow, K., & Grover, V. (2001). A reexamination of IT investment and the market value of the firm: an event study methodology. Information Systems Research, 12, 103–117.

Imbens, G., & Lemieux, T. (2008). Special issue editors' introduction: the regression discontinuity designs' theory and applications. Journal of Econometrics, 142, 611–614.

Ke, B., & Petroni, K. (2004). How informed are actively trading institutional investors? Evidence from their trading behavior before a break in a string of consecutive earnings increases. Journal of Accounting Research, 42(5), 895–927.

Khallaf, A., & Skantz, T. R. (2007). The effects of information technology expertise on the market value of a firm. Journal of Information Systems, 21(1), 83–105.

Kobelsky, K., Hunter, S., & Richardson, V. J. (2008a). Information technology, contextual factors and the volatility of firm performance. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 9(3), 154–174.

Kobelsky, K., Richardson, V. J., Smith, R. E., & Zmud, R. W. (2008b). Determinants and consequences of firm information technology budgets. Accounting Review, 83(4), 957–995.

Leamer, E. E. (1983). Let’s take the con out of econometrics. American Economic Review, 73, 31–43.

Li, M. F., & Ye, L. R. (1999). Information technology and firm performance: linking with environmental, strategic and managerial contexts. Information & Management, 35(1), 43–51.

Li, T., Van Heck, E., & Vervest, P. (2009). Information capability and value creation strategy: advancing revenue management through mobile ticketing technologies. European Journal of Information Systems, 18(1), 38–51.

Loveman, G. W. (1994). An assessment of the productivity impact of information technologies. In T. J. Allen & M. S. S. Morton (Eds.), Information technology and the corporation of the 1990s: Research studies B2 - information technology and the corporation of the 1990s: Research studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lui, A. K., Ngai, E. W., & Lo, C. K. (2015). Disruptive information technology innovations and the cost of equity capital: the moderating effect of CEO incentives and institutional pressures. Information & Management, 53(3), 345–354.

Mahmood, M. A., & Mann, G. J. (1993). Measuring the organizational impact of information technology investment: an exploratory study. Journal of Management Information Systems, 10(1), 97–122.

Mithas, S., & Rust, R. T. (2016). How information technology strategy and investments influence firm performance: Conjecture and empirical evidence. MIS Quarterly, 40(1), 223–245.

Mitra, S. (2005). Information technology as an enabler of growth in firms: an empirical assessment. Journal of Management Information Systems, 22(2), 279–300.

Mittal, N., & Nault, B. (2009). Investments in information technology: indirect effects and information technology intensity. Information Systems Research, 20(1), 140.

Nagm, F., & Kautz, K. (2008). The market value impact of IT investment announcements - an event study. JITTA : Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application, 9(3), 61.

Oh, W., Gallivan, M. J., & Kim, J. W. (2006a). The market's perception of the transactional risks of information technology outsourcing announcements. Journal of Management Information Systems, 22(4), 271–303.

Oh, W., Kim, J. W., & Richardson, V. J. (2006b). The moderating effect of context on the market reaction to IT investments. Journal of Information Systems, 20(1), 19–44.

Panko, R. R. (2008). IT employment prospects: beyond the dotcom bubble. European Journal of Information Systems, 17(3), 182–197.

Rai, A., Patnayakuni, R., & Patnayakuni, N. (1996). Refocusing where and how IT value is realized: an empirical investigation. Omega-International Journal of Management Science, 24(4), 399–412.

Ritter, J., & Warr, R. (2002). The decline of inflation and the bull market of 1982-1999. The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 37(1), 29–61.

Roztocki, N., & Weistroffer, H. R. (2015). Investments in enterprise integration technology: an event study. Information Systems Frontiers, 17(3), 659–672.

Serwer, A. (1997). The scariest tech stock ever! Fortune, 136(9), 223–224.

Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

StandishGroup (2009). Extreme chaos, from http://www.standishgroup.com/sample_research/showfile.php?File=extreme_chaos.pdf.

Subramani, M., & Walden, E. (2001). The impact of e-commerce announcements on the market value of firms. Information Systems Research, 12(2), 135.

Tam, K. Y. (1998). The impact of information technology investments on firm performance and evaluation: evidence from newly industrialized economies. Information Systems Research, 9(1), 85–98.

Tanriverdi, H., & Ruefli, T. (2004). The role of information technology in risk/return relations of firms. Journal of the Association of Information Systems, 5(11–12), 421–447.

Thiesse, F., Al-Kassab, J., & Fleisch, E. (2009). Understanding the value of integrated RFID systems: a case study from apparel retail. European Journal of Information Systems, 18(6), 592–614.

Thistlethwaite, D. L., & Campbell, D. T. (1960). Regression-discontinuity analysis: an alternative to the ex post facto experiment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 51(6), 309–317.

Verrecchia, R. (2001). Essays on disclosure. Journal of Accounting & Economics, 32, 97–180.

Weill, P. (1992). The relationship between investment in information technology and firm performance: a study of the value manufacturing sector. Information Systems Research, 3, 307–333.

Wooldridge, J. (2015). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach. Mason: Nelson Education.

Acknowledgements

Alain Chong would like to acknowledge the support from National Science Foundation of China (NSFC). The project is partially supported by NSFC No. 71402076.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shea, V.J., Dow, K.E., Chong, A.YL. et al. An examination of the long-term business value of investments in information technology. Inf Syst Front 21, 213–227 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-017-9735-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-017-9735-5