Abstract

In this study, we examined potential two-way interaction effects of the Big Five personality traits extraversion and openness to experience on career commitment measured in terms of three components of career identity, career resilience, and career planning. Participants included 450 managers from public and private sector organizations in North India. The results indicated significant positive impacts of extraversion and openness interactions on the career resilience dimension of career commitment. Implications for practice and future research directions are also discussed.

Résumé

Vers une compréhension des effets d’interaction réciproques de l’extraversion et de l’ouverture à l’expérience sur l’engagement professionnel. Dans cette étude nous avons examiné les effets potentiels d’interaction réciproques entre les traits de personnalité de l’extraversion et de l’ouverture à l’expérience du modèle des Big Five sur l’engagement professionnel, mesuré en terme des trois composantes que sont l’identité professionnelle, la résilience professionnelle, et la planification de carrière. Les participants comprenaient 450 managers issus d’entreprises des secteurs privés et publics du nord de l’Inde. Les résultats indiquent un impact positif des interactions entre l’extraversion et l’ouverture sur la dimension de résilience de carrière et de l’engagement professionnel. Les implications pour la pratique et les directions pour de futures recherches sont également discutées.

Zusammenfassung

Auf dem Weg zu einem besseren Verständnis der Interaktionseffekte von Extraversion und Offenheit auf die berufliche Bindung. In dieser Studie untersuchten wir die möglichen Interaktionseffekte der Big Five Persönlichkeitseigenschaften Extraversion und Offenheit auf die berufliche Bindung: berufliche Identität, berufliche Belastbarkeit und Karriereplanung. Zu den Teilnehmern gehörten 450 Führungskräfte aus öffentlichen und privaten Organisationen in Nordindien. Die Ergebnisse zeigten signifikant positive Auswirkungen der Interaktion von Extraversion und Offenheit auf die berufliche Belastbarkeit. Implikationen für die Praxis und zukünftige Forschung werden ebenfalls diskutiert.

Resumen

Hacia la comprensión de los efectos de la interacción, en dos sentidos, de la extroversión y la apertura a la experiencia con el compromiso profesional. En este estudio examinamos los efectos potenciales de la interacción, en dos sentidos, de dos de los rasgos de personalidad del modelo de Cinco Factores: la extroversión y la apertura a la experiencia de compromiso profesional medidas en función de tres componentes: identidad profesional, resistencia/adaptabilidad en la carrera, planificación de la carrera. Participaron cuatrocientos cincuenta gerentes de organizaciones de los sectores público y privado del norte de India. Los resultados revelaron impactos positivos significativos, de las interacciones de la extroversión y la apertura, en la dimensión de la adaptabilidad/resistencia del compromiso profesional. También se presentan algunas implicaciones para la práctica y líneas de investigación futuras.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the past decade, there has been a growing focus from researchers towards understanding the role of individual differences in the achievement of career outcomes (Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2007; Vandenberghe & Ok, 2013). Career commitment is one such potential career outcome that represents an individual’s attachment, identification and involvement with his or her personal career goals (Noordin et al., 2002). Simultaneously, career commitment reflects, “people’s motivations to work toward personal advancement in their professions” (Ellemers et al., 1998, p. 718). Career commitment relates positively to a broad set of variables such as skill development, job satisfaction, career satisfaction, objective and subjective career success, and willingness to participate in professional training (Vandenberghe & Ok, 2013). Accordingly, retaining a career-committed workforce has become a highly critical priority for organizations in present times. In this context, a special emphasis must be given to managers’ career commitment to match their advancement within specific organizations (Noordin et al., 2002). Because managers exhibit greater potential for career advancement in organizations through the utilization of networking, seeking guidance, and creation of new opportunities, they are more likely to display higher levels of motivation to remain tuned into their career line than non-managers (e.g., professional and clerical employees; Noe et al., 1990).

The extent in which one remains motivated in a given career line is influenced by several personality dispositional variables, such as having an internal locus of control or a proactive personality (e.g., Cherniss, 1991; Vandenberghe & Ok, 2013). Existing studies provide adequate evidence about the personality antecedents of career commitment; yet very few researchers emphasize the role of complementary effects of trait interactions in predicting career commitment. Such joint interactions between personality dimensions follows the implicit assumption that, “the impact of a personality trait on behavior depends on other traits” so that each interacts with the other to produce an additive, or complementary, effect (Witt, 2002). In this context, earlier personality interactions studies have focused on job performance (Witt, 2002), and there is a substantial lack of research on joint interactions of personality with reference to career commitment.

To explore this issue, we have adopted the five-factor model theoretical framework of personality, which provides the most promising taxonomy for defining personality in terms of five factors: extraversion, openness, agreeableness, emotional stability, and conscientiousness (McCrae & Costa, 1997). Of these five major personality dimensions, we specifically focused on the Big Five traits of extraversion and openness to experience. First, both of these personality traits constitute beta category of the higher-order factors known for “personal growth” (Digman, 1997). Furthermore, the Big Five traits of emotional stability, conscientiousness, and agreeableness are categorized under the alpha category of the higher-order factors known for “socialization.” Second, extraversion and openness personality traits are predicted by “positive emotional expression,” whereas emotional stability, conscientiousness, and agreeableness are predicted by “negative emotional expression” (DeYoung et al., 2002). Third, both extraversion and openness personality traits govern the novelty and explorative tendencies in an individual, which can further be associated with plasticity or flexibility in behaviors and cognitions (DeYoung et al., 2002). For example, although extraversion acts as a predictor of functioning across a variety of domains and also determines co-variation of different behaviors (Funder, 2001; Ozer & Benet-Martinez, 2006), openness to experience reflects an employee’s ability to adapt to different cultures (Ones & Viswesvaran, 1999). Therefore, given the decisive role of the Big Five traits of extraversion and openness, we seek to examine their joint interaction effects on career commitment.

The current study takes into consideration the context of the Indian sub-continent due to its dynamic economic and socio-cultural characteristics that influences the Indian management practices and systems (Budhwar & Baruch, 2003). As a collectivist society, Indian people are socialized in such a way that they show stronger affinities toward and dependency on others (Budhwar & Baruch, 2003). Therefore, employees’ behavior in India is largely governed by in-group norms with full respect towards hierarchy and harmony (Konsky et al., 1999). Consequently, senior authorities also feel obligated to provide complete protection and security to junior employees (Konsky et al., 1999). Furthermore, Indian work culture is influenced by the principles of “particularism” and “stability.” As a result, employees carry a firm belief in holding a lifelong job and participating in experience-based career systems (Budhwar & Baruch, 2003; Sharma, 1984). Additionally, Indian culture strongly emphasizes relationships in which both employees and organizations express their mutual concern and care towards one other to stimulate employees’ career development (Krishnan, 2012; Overgaard, 2010). This is in contrast to the “protean” and “boundaryless” career orientations prompted by globalization and other competitive pressures (Budhwar & Baruch, 2003), that classify individuals as risk-takers and self-responsible for their career futures (Krishnan, 2012). This advent of career self-management may stem from the individual differences that influence the way individuals’ perceive their commitment levels (Bambacas, 2010). For example, an introverted employee who is low on Openness is less likely to show interest in developmental opportunities. As a result, he or she will not be able to contribute much towards strengthening his or her career identity. On the other hand, an extroverted person with a high Openness score is likely to show a greater preference towards growth opportunities to further improve his or her career prospects.

Although some studies may have explored the dispositional influence on career outcomes, there has been a dearth of published work on the role of personality interactions in predicting career commitment among managers. Therefore, in the present study, we focus upon studying the joint interaction effects of personality traits on career commitment by empirically investigating the Indian business environment to attempt to close these gaps in the literature. We hypothesized that the interaction of extraversion and openness would act as predictors of career commitment in the Indian context.

The Big Five personality traits—extraversion and openness to experience

The Big Five personality trait of extraversion reflects an approach towards social and material world (Witt, 2002). According to Hartman (2006), extraversion is about “feeling good and doing well” (p. 32). Extraversion is characterized by greater activity, spontaneity, and interpersonal competence (Bozionelos, 2004b). Extraversion also determines an individual’s approach to his or her motivation and level of interpersonal connectedness (Minbashian et al., 2009). Extroverted individuals, being social and assertive, enjoy cultivating and building new social connections, and also value relationships to a greater extent (Dachner, 2011; Judge et al., 2002). Being “surgent [ambitious and dominant] and active” (Judge, Higgins, Thoresen, & Barrick, 1999, p. 624), extraverts are more likely to assume significant leadership roles in the organizations. Furthermore, extraversion personality facets are known to influence individuals’ vocational behaviors through “perceptual-affective and motivational channels” (Hartman, 2006, p. 32). For example, the positive emotions facet of extraversion is closely related to career-related cognitive abilities, career-decidedness, and goal-stability (e.g., Hartman, 2006; Multon et al., 1995).

The openness to experience personality trait encompasses multiple interests, such as having an attitude of information seeking, creativity, imagination, and inquisitiveness (Bozionelos et al., 2014). Openness also highlights an individual’s tendency to seek performance feedback from others (Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). Individuals who are high on openness show greater interest in social relationships and new learning that further enables them to understand novel perspectives (Bozionelos et al., 2014; Sinha & Srivastava, 2014). Moreover, such people easily benefit from career enhancing prospects because of their greater ability to initiate relationships with mentors and peers (Bozionelos et al., 2014).

Conceptualizing career commitment

The study of workplace commitments has gained substantial recognition in the past two decades (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001). Career commitment is one such type of work commitment that defines an individual’s motivation to work in a chosen career role (Hall, 1971) and is characterized by strong development and commitment towards career goals. Career commitment is thus “described by the advancement and completing of individual vocational goals” (Mrayyan & Al-Faouri, 2008, p. 40). According to Ballout (2009) career commitment reflects an employee’s commitment toward their careers. And also represents an individual’s commitment towards self-related objectives (Zettler, Friedrich, & Hilbig, 2010). Individuals with high levels of career commitment display high levels of energy in the attainment of career goals (Zettler et al., 2010).

The extant careers literature conceptualizes career commitment both as a uni-dimensional and a multi-dimensional construct. Blau (1985) first propagated career commitment as a uni-dimensional construct, defining it as “one’s attitude towards one’s profession or vocation” (p. 278). Carson and Bedeian (1994) operationalized career commitment as a multidimensional construct based on Hall’s (1971) definition and London’s (1983, 1985) career motivation theory. According to these authors, the career commitment construct is comprised of three main dimensions: career identity, career resilience, and career planning. Career identity represents an individual’s emotional attachment with his or her chosen career line. It forms a directional component of career commitment that defines the extent to which “one defines oneself by one’s work” (Van Rijn et al., 2013, p. 612). Career resilience relates to a person’s persistence and willingness to stay motivated despite the challenges and fluctuations in the job market. Career resilience inculcates a risk-taking attitude in individuals to remain engaged in the informal learning process (Van Rijn et al., 2013). Career planning indicates an individual’s determination and activeness to pursue goal-setting activities (Carson & Bedeian, 1994).

Linking extraversion × openness interaction and career commitment

High Extraversion-High Openness to Experience individuals can be described as assertive, ambitious, sociable, sensation seeking, and receptive to new ideas. Such people possess multiplicative interests and exhibit a strong tendency to develop idealistic goals and ideas (Bozionelos, 2004a). On the other hand, High Extraversion-Low Openness individuals are sociable and interactive, however their low Openness scores indicate a limit in their creative thinking and effectiveness to stay open to new experiences (Borlongan, 2008). Low Extraversion-High Openness represents the novelty seeking, vivid imagination, intellectual, curious approach of introverts who may not show great enthusiasm, who prefer to keep their emotions to themselves and engage in solitary activities (Eldesouky, 2012). Low Extraversion-Low Openness individuals tend to be conservative, conventional, reserved, shy, boastful, quiet, and garrulous (John, 1990). Thus, given the important characteristics associated with high levels of extraversion and openness to experience, we assume that their joint interaction will play a pivotal role in determining an individual’s motivation to remain in a given career line. In this regard, Bozionelos (2004a) also stated that extraversion and openness interact in such a way that tendencies offered by openness, such as newer opportunities, novel situations, and varied perspectives, are better expressed only via the action and sensation-seeking characteristics of the extraversion personality trait.

Extraversion × openness interaction and career identity

High scorers on the extraversion personality trait are assertive, active, and gregarious individuals (Guthrie et al., 1998). Being higher on the dimension of positive affect, such people respond positively towards events and deal effectively with unsatisfactory career situations (Seibert & Kraimer, 2001). Moreover, such people guide their career development process by mapping their intrinsic vocational needs and remains satisfied with their careers (Seibert & Kraimer, 2001). This also helps them to develop specific “knowing why” competencies for deriving their personal meaning to strengthen their career identity (McArdle et al., 2007). Similarly high scores on Openness to experience represent an individual’s tendency to be creative, intellectual, unconventional, and always ready to learn new perspectives (Michel et al., 2011). Consequently, such persons show active participation in various developmental activities, which not only influences their career decidedness (Lounsbury et al., 2005) but also enhances their career identity (Van Rijn et al., 2013).

Henceforth, although high scores on extraversion stimulates individuals to work for the fulfillment of their intrinsic career needs, high scores on openness fosters appropriate conditions of “trust and communication” for initiating and entering into a protégé-mentor relationship (Waters, 2004). In addition, Bozionelos (2004a) found the combination of high extraversion and high openness to be crucial for enhancing work involvement. We thus, propose that interactive effects of extraversion and openness to experience will act as a significant predictor of career identity among Indian managers.

Hypothesis 1

Extraversion interacts with openness to influence career identity. The positive relationship between openness and career identity is stronger for Indian managers reporting high levels of extraversion than those with low levels of extraversion.

Extraversion × openness interaction and career resilience

High scores on Openness to experience is predictive of an individual’s adaptive behavior and managerial coping with stress, organizational change, and resilience (George & Zhou, 2001; Harrison et al., 2006; Judge et al., 1999; Uppal et al., 2014). Likewise, high scores on Extraversion reflect an individual’s nature of engaging in positive social interactions (Werner & Smith, 2001), which is considered a significant characteristic of resilient individuals (i.e., an individual’s ability to thrive in various social contexts; Friborg et al., 2005). Campbell-Sills et al. (2006) demonstrated extraversion as the strongest correlate of resilience. Based on these arguments, we thus assume that a specific interaction between these personality dispositions will be significant in influencing the extent to which individuals maintain their resilience towards their vocation or line of work. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 2

Extraversion interacts with openness to influence career resilience. The positive relationship between openness and career resilience is stronger for Indian managers reporting high levels of extraversion than those with low levels of extraversion.

Extraversion × openness interaction and career planning

Past studies have illustrated the noteworthy role of personality dispositions in influencing career development and career choice processes of the individuals (Rogers & Creed, 2011). Extraversion, for example, has been associated with planning and exploration tendencies (Savickas et al., 2002). Simultaneously, extraversion also reflects a person’s energetic and adaptive nature (Hogan et al., 1997; Matzler et al., 2005). On similar lines, career theorists like Rogers et al. (2008) stressed the association of openness to experience personality trait with planning. Guthrie et al. (1998) noted that this Big Five marker also possesses unique facets, such as “intellectual curiosity” which “lead individuals to be active rather than passive” (p. 375) and also remain engaged in career enhancing behaviors via their self-development. Based on this reasoning, we thus propose that the interactive effects of extraversion and openness will play an important role in predicting Indian managers’ career planning.

Hypothesis 3

Extraversion interacts with openness to experience to influence career planning. The positive relationship between openness to experience and career planning is stronger for Indian managers reporting high levels of extraversion than those with low levels of extraversion.

Method

Participants and procedure

Overall 520 questionnaires were distributed to participants and 450 were returned, yielding a response rate of 87 %. All participants were full-time Indian employees in public (51.6 %) and private sector organizations (48.4 %) in North India. Also, respondent managers were from a wide range of industries (i.e., 42.4 % power, 10.0 % logistics, 22.4 % software, 11.5 % retail, 9.9 % manufacturing, and other 3.8 %). Further, participant managers comprised 84.2 % males and 15.8 % females. Participants were well-educated; the majority were post-graduates (95.8 %) and predominantly between 36 and 40 years of age (79.1 %). The data were collected through establishing contacts with several organizations in North India. Initially, the human resources departments of the organizations were contacted via email and telephone. Upon their consent, researchers conducted personal visits to these organizations. Thus, with the support of HR managers and other staff members, survey questionnaires were distributed during office hours to the employees who met the description of “manager.” The major functions of managers are to fulfill the goals of the enterprise through utilization of key functions of planning, organizing, leading, and controlling, while performing various interpersonal (leader, liaison, and figurehead), information (spokesperson, monitor, and disseminator), and decision- making roles (resource-allocator, negotiator, and disturbance handler; Mintzberg, 2000; Papulová & Mokros, 2007).

Respondent managers were chosen randomly from different departments of each organization and were explained the purpose of the study. They were also assured about the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses, and were also promised with the feedback. Overall participation was kept on a voluntary basis. In some of the cases, where employees and organizations were interested to know the managers overall results on personality and career commitment, were acquainted with their scores on personality (extraversion and openness), and career commitment (career identity, career resilience, and career planning).

Instrument

In this study, we utilized established scales for the measurement of variables as described below. As the study participants were employed managers with high educational qualifications, scales were administered in English. No translation requirement was deemed necessary. All scale items employed a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Extraversion and openness to experience

These personality traits were assessed using the 10-item scale of Goldberg’s Big Five Markers (Goldberg, 1992), available from the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP; http://ipi.ori.org). Elucidative items of the extraversion personality trait included, “I feel comfortable around people,” and Openness to Experience included “I have a rich vocabulary.” To confirm the contextual usefulness of the IPIP scales in the Indian context, we conducted a pilot study on managers from multiple organizations (N = 55). The pilot testing was found to be reliable for both the traits (α >.7). This is in concordance with Uppal’s et al. (2014) findings, which showed the IPIP scales to be the most reliable and valid in the Indian context. Internal consistencies (Cronbach’s α) of extraversion and openness personality traits on an overall sample were .70 and .74, respectively.

Career commitment

This was assessed using the 12-item Career Commitment Measure (CCM; Carson & Bedeian, 1994). The items are grouped into three subscales that reflect the underlying dimensions of career commitment: Career Identity (four items; e.g., “This career field has a great deal of personal meaning to me”); Career Resilience (four items; e.g., “The costs associated with this career field sometimes seem too great”); Career Planning (four items; e.g., “I have created a plan for my development in this career field”). Carson and Bedeian (1994) reported factor analyses on the CCM scale to have well established discriminant and construct validities, along with alpha reliabilities of .79, .85 and .85, respectively for career identity, career resilience, and career planning.

Control variables

We included age, gender, educational level, and organization sector as covariates in the analyses to control their probable spurious effects on the dependent variable, as indicated in previous studies (e.g., Jones et al., 2006; Moscoso Riveros & Tsai, 2011). Coding of the control variables proceeded as follows: Age in years (1 = 21–25, 2 = 26–30, 3 = 31–35, 4 = 36–40, 5 = 41–45, 6 = above 45); gender (1 = male, 2 = female); education level in (1 = diploma, 2 = graduates, 3 = post-graduates, 4 = higher than post-graduate) and organization sector (1 = private, 2 = public).

Analyses

Dimensionality of career commitment on a managerial sample in the Indian context

Confirmatory Factorial Analyses (CFA) were conducted using AMOS version 20 (Arbuckle, 2011), to evaluate the factorial structure of the CCM in the Indian context in line with the methodology adopted in previous studies (e.g., Rossier et al., 2012). For this, we deployed maximum likelihood robust estimation to examine the goodness-of-fit of the three-factor hypothesized model in contrast to the one-factor model. The evaluation of model fit of the tested models proceeded by following a specific criteria of the fit indices used. For example, according to Byrne (2013), for the CFI and TLI, values ranging from .90 to .95 are considered as acceptable and values above .95 indicate a good fit. Similarly, RMSEA values between .05 and .08 indicate an acceptable fit, and values equal to or lower than .05 reflect good fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1992). In addition, we also checked for Akaike’s (1974) information criteria (AIC), with a lower AIC denoting a more parsimonious model (Fong & Ng, 2012). We also used Satorra-Bentler’s scaled Chi square difference test for the comparison of the models (Satorra, 2000). However, due to the sensitivity of the likelihood ratio (Chi square difference test) to non-normality and sample size, we included fit indices so as to provide an improved criteria for the testing of the models (Chen et al., 2005).

Table 1 represents the CFA results of the one-factor model and the three-factor model of the CCM (i.e., career identity, career resilience, and career planning). Additionally, we also computed one additional adjusted three-factor model by considering two covariances between the error terms associated with modification indices above 10. These covariances were below |.20|. The one-factor model of CCM exhibited a poor fit with the CFI and TLI not fulfilling the .90 criterion, and the RMSEA also exceeded the .08 criteria (Browne & Cudeck, 1992). Whereas, the three-factor solution of CCM (model with no adjustment) depicted a relatively good fit with the CFI and TLI closer to .90, and an RMSEA of .08. Further, upon considering two covariances of the item error terms associated with a modification index of above 10, the adjusted three-factor model yielded an acceptable fit with very good fit indices of χ2 (49, N = 450) = 171.82, p < .01; CFI = .93; TLI = .92; RMSEA = .06; and AIC = 229.821. The standardized loadings of the adjusted three-factor model of CCM ranged from .43 to .80, suggesting that all items are strong indicators of the respective constructs.

CFA results clearly showed that in the Indian context, the three-factor solution of CCM represents a better parsimony than a one-factor solution. Henceforth, we proceeded with the subsequent analyses by retaining the three factors of career commitment reported in previous studies (Kidd & Green, 2006): career identity, career resilience, and career planning.

Checks for common method bias

Because data for the current study were self-reported based on a single source, it was important to check for the presence of common method bias (CMB). Although CMB is less prevalent in career advancement research (Ballout, 2009; Crampton & Wagner, 1994), we deployed Harman’s single-factor test (cf. Podsakoff & Organ, 1986) for further confirmation. We subjected all of the study variables to exploratory factor analysis using un-rotated principal component analysis. Test results showed the emergence of a single factor that accounted for only 14.7 % of the variance. This indicated that there was still a lot of variance that needed to be explained by the single factor. This provided us with the confidence that the CMB was not a major threat to our study.

Moderated hierarchical regression analysis

We used moderated hierarchical regression analysis to test interaction hypotheses. Before proceeding, we adopted Aiken and West’s (1991) centering procedure to create the interaction terms. We then entered the control variables in the first step (age, gender, educational level, and organization sector), the main effects in the second step (extraversion and openness), and the interaction term (extraversion × openness) in the third step. These steps were repeated for the dependent variables of career identity, career resilience, and career planning. The analytical approach utilized is in line with previous moderation effect studies (e.g., Burnette et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2014).

Results

Descriptive analyses and reliabilities

Descriptive statistics, means, standard deviations and inter-correlations among the variables are shown in Table 2. All scales depicted an acceptable range of alpha reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) above .70, as suggested by Nunnally (1978). For example, the alpha reliabilities of the three sub-scales of career commitment were .70, .72 and .71 respectively, for career identity, career resilience, and career planning in this study. Further, for the Big Five traits of extraversion and openness to experience, the alpha reliability coefficients were found to be .70 and .74, respectively.

Correlation analyses

Table 2 reports the correlations among the study variables. As indicated in Table 2, career identity has a weak positive correlation with career resilience (r = .195, p < .01) and a very strong positive correlation with career planning (r = .457, p < .01). Career resilience has a small positive correlation with career planning (r = .164, p < .01). These inter-correlations between the three dimensions of career commitment indicate that those individuals who are emotionally attached to their career line (high career identity) are more likely to plan their career goals effectively (high career planning) and vice versa. In this context, London (1985) also stated about close linkage between career planning and career identity dimensions of career commitment in a way that it determines one’s developmental needs and setting of career goals (Noordin et al., 2002). Further, among the Big Five traits of extraversion and openness, while extraversion correlates only to the career planning (r = .118, p < .05), openness personality trait shows a positive correlation to career identity (r = .128, p < .01), career resilience (r = .126, p < .01), and career planning (r = .161, p < .01).

Moderated hierarchical regression analyses

Moderated hierarchical regression analyses were performed for the testing of interaction hypotheses. Hypothesis 1 evaluated the effect of two-way interaction of extraversion and openness personality traits on career identity. As shown in Table 3, the cross product term was not found to be significant predictors of career identity. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was not supported.

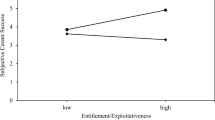

Similarly, for the testing of Hypothesis 2 another set of moderated hierarchical regression analysis was run. Results from Table 3 showed that the two-way interaction effect of extraversion and openness acts as a significant predictor of career resilience (β = .128, p < .01). We further examined this interaction by following Aiken and West’s (1991) procedural guidelines and plotting one standard deviation above and one standard deviation below the mean for extraversion (see Figure 1). In addition we also deployed Stone and Hollenbeck’s (1989) procedure for slope analysis, which further confirmed that a positive relationship between openness personality trait and career resilience was stronger for those managers who were high on extraversion (t = 3.104, p < .001) than their counterparts who were low on extraversion (t = 0.11, p = ns). This provided support to Hypothesis 2.

However, contrary to Hypothesis 3, the two-way interaction effect of extraversion and openness personality traits was not found to have any significant impact on the career planning component of career commitment. Henceforth, Hypothesis 3 was not supported.

Discussion

The current study contributed to the personality and careers literature by investigating the role of trait interactions in predicting career commitment in the Indian context. Until now, the majority of published studies have paid attention to probing the trait interaction effects on job performance (Guay et al., 2013; Witt, 2002). Thus, based on data from 450 Indian managers, our study attempted to fill this gap by examining the trait interaction effects of the Big Five traits of extraversion and openness on career commitment. To achieve the objective, we adopted a multidimensional conceptualization of career commitment studied in terms of three main components of career identity, career resilience, and career planning (Carson & Bedeian, 1994).

This study provided evidence about the significant role of extraversion and openness trait interaction in influencing the career resilience dimension of career commitment. Specifically, the slope analysis findings indicated that openness relates to career resilience among managers with high scores on extraversion; conversely, the openness—career resilience relationship is not significant for managers with low scores on extraversion. Even though extraversion and openness traits enhanced an individual’s strength to encounter challenges related to professional life effectively (de las Olas Palma-García & Hombrados-Mendieta, 2014), the presence of high extraversion is essential for managers with highly inquisitive and creative mind (i.e., high openness) to maintain persistence towards their career. In other words, in the absence of extraversion, an individual may lack expressiveness to show his or her quest for learning or seeking feedback, despite being high on openness, thereby adding a little towards increasing managers’ career resilience.

In addition to the influence of extraversion-openness trait interactions on career resilience, we also analyzed the trait interactive effects on the career identity and career planning dimensions of career commitment. Unexpectedly, trait interactions between extraversion and openness were not seen as significant predictors of career identity and career planning in the Indian context. This may be attributed to several contextual factors that influence the career decision-making and career-planning orientations of the participants studied, aside from other dispositional variables. For example, in the Indian environment, supporting the family, child-rearing practices, hierarchical social organization, and value systems are responsible for guiding interdependence and independent decision-making in the overall nurturing of a person (Arulmani et al., 2001). Noordin et al. (2002) also mentioned the decisive role of parents social-standing in influencing the goal- setting and goal-achievement of their children in the collectivist environment for Malaysian and Australian managers, thereby influencing their career identity and career planning. Also, cognitive variables, such as beliefs and attitudes (e.g., self-perceptions including feelings of happiness, self-image) are also known to influence the individuals’ career-planning orientations (Arulmani et al., 2001).

Implications for managerial practice

The results of the study have several important implications for practice. For example, the findings of this study may be used by organizations to design structured interviews for conducting a personality assessment for hiring candidates. For instance, when number of candidates with higher scores on both extraversion and openness to experience are not available to be hired, then applicants with moderate scores on both the factors might be considered for follow-up interviews to assess their behavioral characteristics in close association with these traits (Witt, 2002). Furthermore, “positive emotionality is considered to be the hallmark of extraverts” who have great confidence about their careers (Watson & Clark, 1997) and openness to experience indicates an individual’s need for novelty and intrinsic appreciation for the experience (Wang et al., 2013). To foster a career-committed workforce, it is important to enhance employees’ personality awareness to enable them to identify those work situations that are most conducive to the beneficial expression of their traits (Blickle et al., 2013). Aside from this, career resilience forms a significant component of an individual’s career commitment. Therefore, organizations should train managers to be resilient by being proactive in anticipating career challenges. Also, as reflected in our study findings, high extraversion enhances the positive association between openness and the career resilience relationship. Accordingly, managers may also be encouraged to engage in behaviors that can enhance their professional networking and connecting linkages with their co-workers and other significant organizational members.

Limitations and future research directions

There are several limitations to this research. First, this study deployed a cross–sectional survey-based research design. Therefore, any inferences regarding causal relationships between the variables must be made with caution. Further investigation using experimental and longitudinal research designs is recommended for making any causal conclusions.

Second, because participants of this study included managerial employees from public and private sector organizations in North India, no sample segregation in terms of occupational groups was considered. Therefore, one must be careful while generalizing current research findings to people with specific job profiles. For instance, one might expect somewhat different results in relation to effects of trait interactions for sales professionals and IT professionals. A further investigation focused on comparative analyses using varied occupational samples could be useful for arriving at more concrete conclusions.

Third, the selection of control variables limited to demographics and organization-relevant variables, and no controls were established for the other Big Five personality traits (i.e., emotional stability, conscientiousness, and agreeableness), because measuring them went beyond the focus of this study. This may have limited the variation in the results, considering that the possible categories overlap with the personality descriptors (Allen & Potkay, 1981; John & Srivastava, 1999), and one might question the findings. Thus, we suggest future research take this perspective into account.

Additionally, we also recommend that researchers employ cross-cultural studies using international samples to analyze the consistency patterns of the current research findings. Furthermore, the results of this research may be advanced by conducting replication studies in different business contexts and by looking at the career commitment relationship with those trait interactions that seem to have a strong intuitive appeal. While this research adds to the existing knowledge base of the available literature on personality and career outcomes by conducting an inquiry on the joint interactive effects of personality variables (extraversion and openness) and career commitment, including Hofstede’s (1984) cultural dimensions of power-distance, masculinity-femininity, uncertainty-avoidance, and individualism-collectivism as moderator variables into the present research would further help in comprehending this study from the cultural context. For example, it would be interesting to study how the three-way interactions of extraversion, openness, and the cultural dimension of power-distance influence managers’ career planning, given the fact that cultures with high power-distance ratios are likely to perceive high levels of career planning as necessary (Noordin et al., 2002).

Theoretically, the current study findings may be utilized for conducting experimental studies on trait interactions’ influence on career commitment using a multicultural sample approach. Additionally, this process may include mediator or moderator variables guided by adequate literature support. Furthermore, the Big Five traits constitute stable patterns of thought, feelings, and behavior. Subsequently, adopting a longitudinal research design may allow researchers to envisage the contribution of personality antecedents in the development of career commitment over time.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Akaike, H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. Automatic Control, IEEE Transactions On, 19, 716–723. doi:10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705.

Allen, B. P., & Potkay, C. R. (1981). On the arbitrary distinction between states and traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 916–992. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.41.5.916.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2011). IBM SPSS Amos 20 user’s guide. Amos Development Corporation, SPSS Inc.

Arulmani, G., Van Laar, D., & Easton, S. (2001). Career planning orientation of disadvantaged high school boys: A study of socioeconomic and social cognitive variables. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 27(1–2), 7–17. Retrieved from http://eprints.port.ac.uk/id/eprint/11310.

Ballout, H. I. (2009). Career commitment and career success: Moderating role of self-efficacy. Career Development International, 14, 655–670. doi:10.1108/13620430911005708.

Bambacas, M. (2010). Organizational handling of careers influences managers’ organizational commitment. Journal of Management Development, 29, 807–827. doi:10.1108/02621711011072513.

Blickle, G., Meurs, J. A., Wihler, A., Ewen, C., Plies, A., & Günther, S. (2013). The interactive effects of conscientiousness, openness to experience, and political skill on job performance in complex jobs: The importance of context. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34, 1145–1164. doi:10.1002/job.1843.

Borlongan, M. D. D. (2008). Goal orientation-creativity relationship: Openness to experience as a moderator. (Masters dissertation, Department of Psychology, San Jose State University). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. (UMI Number: 1458118).

Bozionelos, N. (2004a). The Big Five of personality and work involvement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 19(1), 69–81. doi:10.1108/02683940410520664.

Bozionelos, N. (2004b). Mentoring provided: Relation to mentor’s career success, personality, and mentoring received. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(1), 24–46. doi:10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00033-2.

Bozionelos, N., Bozionelos, G., Polychroniou, P., & Kostopoulos, K. (2014). Mentoring receipt and personality: Evidence for non-linear relationships. Journal of Business Research, 67, 171–181. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.10.007.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods and Research, 21, 230–258. doi:10.1177/0049124192021002005.

Budhwar, P. S., & Baruch, Y. (2003). Career management practices in India: An empirical study. International Journal of Manpower, 24, 699–719. doi:10.1108/01437720310496166.

Burnette, J. L., Pollack, J. M., & Hoyt, C. L. (2010). Individual differences in implicit theories of leadership ability and self-efficacy: Predicting responses to stereotype threat. Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(4), 46–56. doi:10.1002/jls.20138.

Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York: Routledge.

Campbell-Sills, L., Cohan, S. L., & Stein, M. B. (2006). Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behavior Research and Therapy, 44, 585–599. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.001.

Carson, K. D., & Bedeian, A. G. (1994). Career commitment: Construction of a measure and examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 44, 237–262. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1994.1017.

Chen, F. F., Sousa, K. H., & West, S. G. (2005). Teacher’s corner: Testing measurement invariance of second-order factor models. Structural Equation Modeling, 12(3), 471–492. doi:10.1207/s15328007sem1203_7.

Cherniss, C. (1991). Career commitment in human service professionals: A biographical study. Human Relations, 44, 419–437. doi:10.1177/001872679104400501.

Crampton, S. M., & Wagner, J. A. (1994). Percept-percept inflation in micro organizational research: An investigation of prevalence and effect. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(1), 67–76. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.79.1.67.

Dachner, A. (2011). Interpersonal relationships at work: An examination of dispositional influences and organizational citizenship behavior. Retrieved from http://kb.osu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/1811/48334/Knowedge_Bank_Submission_3-24-2011.pdf?sequence=1.

de las Olas Palma-García, M., & Hombrados-Mendieta, I. (2014). Resilience and personality in social work students and social workers. International Social Work, 1–13. doi:10.1177/0020872814537856.

DeYoung, C. G., Peterson, J. B., & Higgins, D. M. (2002). Higher-order factors of the Big Five predict conformity: Are there neuroses of health? Personality and Individual Differences, 33(4), 533–552. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00171-4.

Digman, J. M. (1997). Higher-order factors of the Big Five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 1246–1256. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.6.1246.

Eldesouky, L. (2012). Openness to experience and health: A review of the literature. The Yale Review of Undergraduate Research in Psychology, 5, 24–42. Retrieved from www.yale.edu/yrurp/issues/Eldesouky2013.pdf.

Ellemers, N., de Gilder, D., & van den Heuvel, H. (1998). Career-oriented versus team-oriented commitment and behavior at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 717. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.83.5.717.

Fong, T. C. T., & Ng, S. M. (2012). Measuring engagement at work: Validation of the Chinese version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 19(3), 391–397. doi:10.1007/s12529-011-9173-6.

Friborg, O., Barlaug, D., Martinussen, M., Rosenvinge, J. H., & Hjemdal, O. (2005). Resilience in relation to personality and intelligence. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 14(1), 29–42. doi:10.1002/mpr.15.

Funder, D. C. (2001). Personality. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 197–221. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.197.

George, J. M., & Zhou, J. (2001). When openness to experience and conscientiousness are related to creative behavior: An interactional approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 513–524. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.513.

Goldberg, L. R. (1992). The development of markers of the Big-Five factor structure. Psychological Assessment, 4, 26–42. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.26.

Guay, R. P., Oh, I. S., Choi, D., Mitchell, M. S., Mount, M. K., & Shin, K. (2013). The interactive effect of conscientiousness and agreeableness on job performance dimensions in South Korea. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 21, 233–238. doi:10.1111/ijsa.12033.

Guthrie, J. P., Coate, C. J., & Schwoerer, C. E. (1998). Career management strategies: The role of personality. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 13(5/6), 371–386. doi:10.1108/02683949810220024.

Hall, D. T. (1971). A theoretical model of career subidentity development in organizational settings. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 6(1), 50–76. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(71)90005-5.

Harrison, M. M., Neff, N. L., Schwall, A. R., & Zhao, X. (2006). A meta-analytic investigation of individual creativity and innovation. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Society of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Dallas, TX.

Hartman, R. O. (2006). The five factor model and career self-efficacy: General and domain specific relationships. (Doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University). Retrieved from https://etd.ohiolink.edu/rws_etd/document/get/osu1147867278/inline.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Cultural dimensions in management and planning. Asia Pacific journal of management, 1(2), 81–99. doi:10.1007/BF01733682.

Hogan, R., Johnson, J., & Briggs, S. (Eds.). (1997). Handbook of personality psychology. San Diego: Academic Press.

John, O. P. (1990). The “Big Five” factor taxonomy: Dimensions of personality in the natural language and in questionnaires. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 66–100). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The “Big Five” trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 102–138). New York: Guilford Press.

Jones, M. L., Zanko, M., & Kriflik, G. (2006). On the antecedents of career commitment. Retrieved from http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2944&context=commpapers.

Judge, T. A., Heller, D., & Mount, M. K. (2002). Five-factor model of personality and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 530–541. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.530.

Judge, T. A., Higgins, C. A., Thoresen, C. J., & Barrick, M. R. (1999a). The big five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Personnel Psychology, 52, 621–652. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1999.tb00174.x.

Judge, T. A., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2007). Personality and career success. In H. Gunz & M. Peiperl (Eds.), Handbook of career studies (pp. 59–78). London: Sage.

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Pucik, V., & Welbourne, T. M. (1999b). Managerial coping with organizational change: A dispositional perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(1), 107–122. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.84.1.107.

Kidd, J. M., & Green, F. (2004). The careers of research scientists: Predictors of three dimensions of career commitment and intention to leave science. Personnel Review, 35, 229–251. doi:10.1108/00483480610656676.

Konsky, C., Eguchi, M., Blue, J., & Kapoor, S. (1999). Individualist-collectivist values: American, Indian and Japanese cross-cultural study. Intercultural Communication Studies, 9(1), 69–84. Retrieved from http://www.uri.edu/iaics/content/1999v9n1/07%20Catherine%20Konsky,%20Mariko%20Eguchi,%20Janet%20Blue,%20&%20Suraj%20Kapoor.pdf.

Krishnan, T. N. (2012). Diversity in career systems: The role of employee work values. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 47, 685–699.

Liu, Y., Peng, K., & Wong, C. S. (2014). Career maturity and job attainment: The moderating roles of emotional intelligence and social vocational interest. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 14(3), 293–307. doi:10.1007/s10775-014-9271-5.

London, M. (1983). Toward a theory of career motivation. Academy of Management Review, 8(4), 620–630. doi:10.5465/AMR.1983.4284664.

London, M. (1985). Developing managers: A guide to motivating and preparing people for successful managerial careers. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Lounsbury, J. W., Hutchens, T., & Loveland, J. M. (2005). An investigation of Big Five personality traits and career decidedness among early and middle adolescents. Journal of Career Assessment, 13(1), 25–39. doi:10.1177/1069072704270272.

Matzler, K., Faullant, R., Renzl, B., & Leiter, V. (2005). The relationship between personality traits (extraversion and neuroticism), emotions and customer self-satisfaction. Innovative Marketing, 1(2), 32–39.

McArdle, S., Waters, L., Briscoe, J., & Hall, D. (2007). Employability during unemployment: Adaptability, career identity and human and social capital. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 71, 247–264. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2007.06.003.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1997). Personality trait structure as a human universal. American Psychologist, 52, 509–516. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.5.509.

Meyer, J. P., & Herscovitch, L. (2001). Commitment in the workplace: Toward a general model. Human Resource Management Review, 11, 299–326. doi:10.1016/S1053-4822(00)00053-X.

Michel, J. S., Clark, M. A., & Jaramillo, D. (2011). The role of the Five Factor Model of personality in the perceptions of negative and positive forms of work–nonworkspillover: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79, 191–203. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2010.12.010.

Minbashian, A., Bright, J. E., & Bird, K. D. (2009). Complexity in the relationships among the sub-dimensions of extraversion and job performance in managerial occupations. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82, 537–549. doi:10.1348/096317908X371097.

Mintzberg, H. (2000). The manager‘s job: Folklore and fact. Retrieved from http://mazinger.sisib.uchile.cl/repositorio/pa/ciencias_economicas_y_administrativas/m200211221010cita3.pdf.

Moscoso Riveros, A. M., & Tsai, T. S. T. (2011). Career commitment and organizational commitment in for-profit and non-profit sectors. International Journal of Emerging Sciences, 1(3), 324–340.

Mrayyan, M. T., & Al-Faouri, I. (2008). Predictors of career commitment and job performance of Jordanian nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 16, 246–256. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00797.x.

Multon, K. D., Heppner, M. J., & Lapan, R. T. (1995). An empirical derivation of career decision subtypes in a high school sample. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 47, 76–92. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1995.1030.

Noe, R. A., Noe, A. W., & Bachhuber, J. A. (1990). An investigation of the correlates of career motivation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 37, 340–356. doi:10.1016/0001-8791(90)90049-8.

Noordin, F., Williams, T., & Zimmer, C. (2002). Career commitment in collectivist and individualist cultures: A comparative study. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(1), 35–54. doi:10.1080/09585190110092785.

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric methods. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Ones, D. S., & Viswesvaran, C. (1999). Relative importance of personality dimensions for expatriate selection: A policy capturing study. Human Performance, 12, 275–294. doi:10.1080/08959289909539872.

Overgaard, L. (2010). An analysis of Indian culture in an era of globalization (Master’s Thesis, Aarhus University). Retrieved from http://pure.au.dk/portal/files/13754/236687.pdf.

Ozer, D. J., & Benet-Martinez, V. (2006). Personality and the prediction of consequential outcomes. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 401–421. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190127.

Papulová, Z., & Mokros, M. (2007). Importance of managerial skills and knowledge in management for small entrepreneurs. E-leader. Retrieved from http://www.g-casa.com/PDF/Papulova-Mokros.pdf.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12, 531–544. doi:10.1177/014920638601200408.

Rogers, M. E., & Creed, P. A. (2011). A longitudinal examination of adolescent career planning and exploration using a social cognitive career theory framework. Journal of Adolescence, 34(1), 163–172. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.12.010.

Rogers, M. E., Creed, P. A., & Glendon, A. I. (2008). The role of personality in adolescent career planning and exploration: A social cognitive perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73, 132–142. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2008.02.002.

Rossier, J., Zecca, G., Stauffer, S. D., Maggiori, C., & Dauwalder, J. P. (2012). Career adapt-abilities scale in a French-speaking Swiss sample: Psychometric properties and relationships to personality and work engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80, 734–743. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.004.

Satorra, A. (2000). Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. In R. D. H. Heijmans, D. S. G. Pollock, & A. Satorra, (Eds.), Innovations in multivariate statistical analysis. A Festschrift for Heinz Neudecker (pp. 233–247). London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Savickas, M. L., Briddick, W. C., & Watkins, C. E. (2002). The relation of career maturity to personality type and social adjustment. Journal of Career Assessment, 10, 24–41. doi:10.1177/1069072702010001002.

Seibert, S. E., & Kraimer, M. L. (2001). The five-factor model of personality and career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58, 1–21. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2000.1757.

Sharma, I. J. (1984). The culture context of Indian managers. Management and Labor Studies, 9(2), 72–80.

Sinha, N., & Srivastava, K. B. (2014). Examining the relationship between personality and work values across career stages. Psychological Studies, 59(1), 44–51. doi:10.1007/s12646-013-0227-5.

Stone, E. F., & Hollenbeck, J. R. (1989). Clarifying some controversial issues surrounding statistical procedures for detecting moderator variables: Empirical evidence and related evidence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 3–10. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.74.1.3.

Uppal, N., Mishra, S. K., & Vohra, N. (2014). Prior related work experience and job performance: Role of personality. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 22(1), 39–51. doi:10.1111/ijsa.12055.

Vandenberghe, C., & Ok, A. B. (2013). Career commitment, proactive personality, and work outcomes: A cross-lagged study. Career Development International, 18, 652–672. doi:10.1108/CDI-02-2013-0013.

Van Rijn, M. B., Yang, H., & Sanders, K. (2013). Understanding employees’ informal workplace learning: The joint influence of career motivation and self-construal. Career Development International, 18, 610–628. doi:10.1108/CDI-12-2012-0124.

Wanberg, C. R., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of proactivity in the socialization process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 373–385. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.373.

Wang, M., Olson, D. A., & Shultz, K. S. (2013). Mid and late career issues: An integrative perspective. New York: Routledge.

Waters, L. (2004). Protégé–mentor agreement about the provision of psychosocial support: The mentoring relationship, personality, and workload. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65, 519–532. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.004.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1997). Extraversion and its positive emotional core. In R. Hogan, J. Johnson, & S. Briggs (Eds.), Handbook of personality psychology. San Diego: Academic Press.

Werner, E. E., & Smith, R. S. (2001). Journeys from childhood to midlife: Risk, resilience, and recovery. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Witt, L. A. (2002). The interactive effects of extraversion and conscientiousness on performance. Journal of Management, 28, 835–851. doi:10.1177/014920630202800607.

Zettler, I., Friedrich, N., & Hilbig, B. E. (2011). Dissecting work commitment: The role of Machiavellianism. Career Development International, 16(1), 20–35. doi:10.1108/13620431111107793.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arora, R., Rangnekar, S. Towards understanding the two way interaction effects of extraversion and openness to experience on career commitment. Int J Educ Vocat Guidance 16, 213–232 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-015-9296-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-015-9296-4