Abstract

Understanding factors that influence local community support for conservation projects is critical to their success. Perceptions of wildlife are particularly important in countries where people rely heavily on natural resources for their survival, as is the case in Madagascar. Renowned as one of the “hottest” regions for global biodiversity, Madagascar hosts an exceptional assemblage of lemurs. Yet little is known concerning the knowledge and perceptions of local people toward lemurs. The Lake Alaotra gentle lemur (Hapalemur alaotrensis) is classified as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List and restricted to marsh habitat in the Lake Alaotra New Protected Area. Habitat destruction and hunting have brought the lemur to the brink of extinction. In this study we characterize local people’s knowledge, awareness, and perceptions of Hapalemur alaotrensis. We conducted an initial survey with 180 participants in 6 villages with varying distance to Park Bandro, a high-priority conservation zone. During a second survey, we interviewed 50 people in the village adjacent to the park. Our findings demonstrate that fishers are the most knowledgeable local resource users despite having the lowest education levels, and they also are the most concerned with the endemic lemur’s decline. There is a link between environmental awareness and distance in both a literal and figurative sense; the more often people encounter Hapalemur alaotrensis, the more they know about it, and the more likely they are to be concerned about its future. Our study further shows that despite this concern, subsistence is prioritized over conservation in the Alaotra region. Ecological knowledge in the fishers’ communities is a valuable resource that can benefit the conservation of Hapalemur alaotrensis and its marshland habitat if conservation planning and management can align the resource users’ concerns and livelihood needs with biodiversity values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Linking conservation values with the livelihood needs of local communities is essential for any conservation strategy, particularly in a region where people rely heavily on natural resources for survival and income (Mehta and Kellert 1998; Nepal and Spiteri 2011; Nyaupane and Poudel 2011; Salafsky and Wollenberg 2000). Agrawal and Gibson (1999) demonstrated that local support for conservation projects was crucial and that conservation management would be more likely to be successful if the communities’ perceptions and values were understood. Qualitative information gained from ethnographic studies provides valuable insights toward the understanding of conservation problems (Setchell et al. 2016) and is invaluable in ensuring the inclusion of local community concerns within conservation planning.

Madagascar, renowned as one of the “hottest” regions for global biodiversity (Ganzhorn et al. 2001; Myers et al. 2000), hosts an outstanding assemblage of primates—lemurs—found nowhere else in the world (Mittermeier et al. 2008; Thalmann 2006). The number of described lemur species has increased from fewer than 50 to more than 105 different taxa over the last two decades (Tattersall 2013; Waeber et al. 2015), primarily owing to increased efforts in field research and advancements in molecular biology. However, lemurs are increasingly threatened with extinction (Schwitzer et al. 2013). Little is known concerning the knowledge and perceptions of local people toward lemurs.

While most lemur species are forest dwellers occupying a variety of forest types throughout Madagascar (Mittermeier et al. 2008), the Lake Alaotra gentle lemur (Hapalemur alaotrensis, known locally as bandro) is unique because of its restriction to the marshlands of the Lake Alaotra New Protected Area, where it feeds on sedges (particularly Cyperus spp.), reeds, and grasses (Mutschler et al. 1998). Hapalemur alaotrensis is the only primate species in the world known to live exclusively within a marsh habitat (Waeber et al. 2017a, b). It is one of five extant species in the genus Hapalemur along with the southern bamboo lemur (Hapalemur meridionalis), northern bamboo lemur (Hapalemur occidentalis), lesser bamboo lemur (Hapalemur griseus), and the golden bamboo lemur (Hapalemur aureus) (Ballhorn et al. 2016; Mittermeier et al. 2014).

Hapalemur alaotrensis is classified as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List (IUCN 2014). The species is at high risk of extinction due to a significant decline in population size and an ongoing reduction in area, extent, and quality of marsh habitat at Lake Alaotra. The species has been on a continuous decline since the first monitoring undertaken by Mutschler and Feistner (1995), who estimated 7500–11,000 individuals. Subsequent monitoring reported fewer than 2500 individuals between 2003 (Ralainasolo 2004) and 2005 (Ralainasolo et al. 2006). Current numbers are assumed to be even less due to ongoing habitat loss (Ratsimbazafy et al. 2013). Although former intensive hunting pressure had declined (Andrianandrasana et al. 2005; Mutschler et al. 2001), increased marsh fragmentation and lack of local enforcement appear to have resulted in renewed poaching both for bushmeat and the local pet trade. At the same time, marsh destruction continues unabated and presents a serious threat to the species survival (Ratsimbazafy et al. 2013; Waeber and Wilmé 2013).

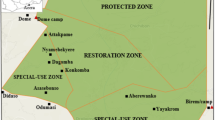

Lake Alaotra is located in the eastern-central highlands of Madagascar, in the Alaotra–Mangoro Region (Fig. 1). It is the largest lake in Madagascar, covering some 20,000 ha of open water, surrounded by 23,000 ha of marshland (Andrianandrasana et al. 2005). The area is of high socioeconomic importance as Madagascar’s greatest producer of rice and fish (Copsey et al. 2009b; Ranarijaona 2007; Wallace et al. 2015). Human pressure on the ecosystem is high, with more than 550,000 people living around the lake (INSTAT 2012). Marsh burning, draining, conversion to rice fields, and siltation from erosion of topsoil have reduced the marshes around Lake Alaotra to <25% of its historic 60,000–80,000 ha levels (Bakoariniaina et al. 2006). Located at the southeastern shore of the lake, Park Bandro is a small (originally 85 ha) protected area within the larger New Protected Area (Fig. 1) that was established as a special conservation zone in 2004. The park is of high conservation importance, as it hosts the biggest known subpopulation of Hapalemur alaotrensis (Ratsimbazafy et al. 2013). It was created by the local VOI (vondron’ olona ifotony, a local community association for natural resource management) from the nearby village of Andreba with support from the conservation organizations Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust and Madagascar Wildlife Conservation. Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust has been working in the region since the mid-1990s, and Madagascar Wildlife Conservation has been present since 2003. Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust has focused on creation of the Lake Alaotra New Protected Area and ecological monitoring (Andrianandrasana et al. 2005), supporting 90 local people carrying out weekly patrols in the marsh around the lake, while Madagascar Wildlife Conservation has focused on environmental education and ecotourism (Maminirina et al. 2006; Rendigs et al. 2015).

Lake Alaotra with surrounding marshes and rice fields. The map shows the Lake Alaotra New Protected Area (NPA) boundaries, the location of Park Bandro, and the six study sites. We recorded sightings of Hapalemur alaotrensis since 2014 in three participatory mapping workshops with local experts in January 2017.

We developed the current research project to understand levels of environmental awareness and what lemurs mean to resource users around Lake Alaotra, specifically whether there were differences in levels of knowledge and concern among user groups and among villages located at varying distances from the high-priority conservation zone Park Bandro. With this explorative qualitative research we characterize local people’s knowledge and awareness of Hapalemur alaotrensis. We further explore their attitudes toward, and values concerning the lemur within the context of developing future environmental awareness and conservation management plans.

Methods

We carried out two questionnaire surveys in 2015 to examine local people’s knowledge, awareness, and perceptions of Hapalemur alaotrensis. Ethnographic experiences gained during previous studies (Rakotoarisoa et al. 2015; Ralainasolo 2004; Reibelt et al. 2014) and the composition of our research team (locals from various areas around Lake Alaotra) helped in questionnaire design, pretesting, and data analysis. To examine differences in levels of awareness between sites and user groups we compared years of schooling between smaller, remote villages around the lake (Anororo, Vohimarina, Ambatosoratra, Andreba, Angoja) and the regional capital Ambatondrazaka, as well as between user groups. In July 2015 we carried out survey 1 and involved 180 participants from 6 sites around Lake Alaotra (Fig. 1). We chose villages to represent varying distances from the community managed ecotourism and conservation area at Park Bandro near Andreba. In September of the same year, we interviewed 50 participants from Andreba in survey 2. We collected baseline data on the participants including their main livelihood activity in both surveys (Table I).

Survey 1 focused on quantifying people’s knowledge of Hapalemur alaotrensis at the scale of the entire lake. Questions focused on whether, when, where, and how many lemurs they had encountered. Survey 2 explored people’s perceptions of the value of different animal types at Andreba, the village nearest to Park Bandro. We asked participants to rank wild and domestic animals according to importance and to provide the reasons for their ranking. Both surveys contained questions concerning the conservation value of H. alaotrensis.

We applied purposive sampling (Bernard 2006) by interviewing people at the lake, close to the marshland border, and along the main route between each village market and the lake shores. We assumed that these people are natural resource users and that they influence or depend on the marsh and/or lake in some way. For the second survey we focused on people who we encountered along the border of the lake or marsh near Andreba to focus on direct resource users who earn their living by working on the lake or in the marsh. In both surveys we divided the interviews equally among morning, mid-day, and evening. Participation was voluntary, and we informed all participants about the aims and scope of the research project before obtaining their consent to take part in the study. A small number of participants were 14–16 years old (Table I). We treated these participants in the same manner as those in other age groups, as it is common for younger people to be engaged in livelihoods reliant on natural resource use and we did not want to exclude them from the survey.

Surveys were anonymous and administered in Malagasy by two local research assistants whom we trained before starting the data collection. A female research assistant presented the survey verbally, and a male assistant recorded responses, allowing for an open discussion style interview. The open questions allowed participants to express knowledge and perceptions in their own words so that qualitative information was not lost (Drury et al. 2011; Setchell et al. 2016). We administered surveys over 1–4 days per site. Questionnaires contained open questions as well as ranking and yes/no questions. For open questions we conducted quantitative content analysis with inductive creation and establishment of categories (Lamnek 2005). We discussed and adapted the categories in an iterative process within the research team. During analysis, we calculated summary statistics including percentages of all answers. To test for differences between sites and between professions, we used Fisher’s exact test, the t-test, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test using R (versions 3.0.3 and R 3.2.1; R Core Team 2015).

Ethical Note

Our research followed the principles outlined in the ethical code for research by Wilmé et al. (2016).

Results

Survey Participants

Of the 180 participants from the initial survey, the median age was 35 yr. (mean 36, range 14–75), and the median years of schooling was 8 yr. (mean 7.4, range 1–14, Table I). Participants from the city of Ambatondrazaka had significantly more years of schooling than any of the villages (two-sample t-tests with Bonferroni correction, all P < 0.001; details in Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] Table SI). Of the 50 participants from survey 2 in Andreba, the median age was 37 (mean 38, range 15–73), and the median years of schooling was 8 yr. (mean 8, range 0–14 yr.; Table I).

Local Knowledge of Hapalemur alaotrensis

Of the 180 participants in the initial survey, 89% said that they knew of Hapalemur alaotrensis. When describing the lemur, 63% of the participants drew comparison with humans, cats, and other lemurs (Fig. 2, Table SX). Sixty-one percent of those who knew of H. alaotrensis mentioned physical characteristics related to color, size, pelage, and body shape while 8% described the lemur’s character as shy, gentle, or sympathetic (Table SX). Twenty-four percent pointed out that H. alaotrensis has a diet based on marshland vegetation, including mentions of specific vegetation such as reeds (11%) and sedges (Cyperus spp.; 9%).

The most common responses to “What do you know about Hapalemur alaotrensis, called bandro?” in survey 1 (N = 180) at Lake Alaotra in 2015. Percentages are from the “Yes” subsample of 160 people who knew the lemur (89% of total sample). Overall, participants gave a range of 1–6 answers, with a mean of 2 (median = 2). See Table SVIII for a complete list of descriptions of the lemur.

When we asked participants whether they knew where Hapalemur alaotrensis lived, 83% said yes, and 17% didn’t know. Of the participants, 83% replied that the lemur lived in Madagascar, and of these, 13% said this lemur lived throughout the Alaotra region while others (87%) cited specific sites or villages around the lake. Of the 180 participants, 81% stated that H. alaotrensis lives in the marshes, while 2% wrongly referred to the open landscape and 1% mentioned forest. Significantly more fishers knew where H. alaotrensis lived (N = 94; 90% of fishers) when compared to nonfishers (N = 55; 72% of nonfishers; Fisher’s exact test, 95% confidence interval [0.110, 0.676], odds ratio: 0.281, P = 0.002; Table SIV).

When asked for information about personal encounters with Hapalemur alaotrensis, 86% of participants answered they had seen the lemur at some point during their life, with no significant difference among the six study sites (Table SVIII). Of these, 20% had seen the lemur in Park Bandro, 70% in the marshes outside of the park, and 10% in captivity (Fig. 3). These differences in lemur sighting locations between sites were significant between the regional capital of Ambatondrazaka and the villages of Anororo and Andreba (closest to Park Bandro), and also between Anororo and Vohimarina (Fisher’s exact test with Monte Carlo simulation, all P < 0.001; Table SVIII). Respondents from Ambatondrazaka stated that they had either seen H. alaotrensis in the marshes outside Park Bandro (55%) or in captivity (45%), while in Andreba, 69% of people surveyed had seen lemurs outside of Park Bandro compared to 31% within the park. None of the people interviewed from Andreba reported having seen H. alaotrensis in captivity. Fifty-eight percent of the respondents in Ambatondrazaka had last seen a H. alaotrensis more than a year ago, compared to a sighting during the last 6 mo for 58% of the people interviewed at Andreba (Fisher’s exact test with Monte Carlo simulation, P = 0.003; Table SVIII).

Of the 160 respondents who knew Hapalemur alaotrensis (Fig. 2), 61% were fishers and 39% were nonfishers, and significantly more fishers knew of H. alaotrensis than nonfishers (Fisher’s exact test, 95% confidence interval [0.082, 0.805], odds ratio: 0.273, P = 0.015; Table SIV).

Local Perceptions of and Values Concerning Hapalemur alaotrensis

When we asked participants to provide three open statements that best described what Hapalemur alaotrensis meant to them, the most common answers were that the lemur “lives in the marshes,” “feeds on marsh vegetation,” and is “catlike.” Other common replies were that the lemur “attracts tourists,” is a “mammal,” and is a “richness for the region” (Table II).

When we asked people whether they were personally affected by a decline in lemur numbers (survey 1, N = 180), 64% of participants said they were concerned while 20% said they were not concerned. Significantly more fishers than nonfishers were concerned by the decline in number of lemurs (Fisher’s exact test, 95% confidence interval [0.171, 0.909], odds ratio: 0.397, P = 0.019, Table SIV; Fig. 4). The sites with the highest concern were Ambatosoratra, Andreba, and Angoja, and those with the least concern were Anororo and Vohimarina (Fisher’s exact test with a Bonferroni correction; all P < 0.003, Table SIX; Fig. 5).

The most common reasons cited for being concerned about population declines were “bandro could go extinct,” “bandro is humanlike,” and “loss of richness” (Table III). Other reasons were “loss of prestige,” “environmental destruction,” “loss of pleasure,” “marsh destruction,” and “no tourism.” For those people that were not concerned, the two reasons cited were “it’s not important” and “the decline is a myth.”

When looking at the four closed questions regarding the lemur that could be answered with a yes or no, we summarized the number of “yes” answers to build a composite variable for awareness and concern. The composite variable correlated negatively with distance to Park Bandro (Kendall correlation: z = −4.165, P < 0.001, τ = −0.26; Fig. 6); in other words, more people from sites near Park Bandro were aware of and concerned about Hapalemur alaotrensis than in villages further away. Years of schooling did not have a significant effect on the composite variable (we compared more vs. less than mean years of schooling ≥8 yr. vs. <8 yr., with a Wilcoxon rank sum test: W = 4410, P = 0.092).

The relationship between distance of a village to Park Bandro and a composite variable measuring awareness/knowledge of Hapalemur alaotrensis based on surveys carried out at Lake Alaotra in 2015. The composite variable includes all closed questions regarding Hapalemur alaotrensis (answerable either yes or no; Fig. S1). The size of the bubbles indicates how many people answered yes at the respective distance/ study site.

The ranking of wild and domestic animals revealed that the study participants considered zebu and fish to be the most important, followed by pigs and chickens. Study participants ranked Hapalemur alaotrensis and ducks (domestic and wild) as least important (Fig. 7). The most common reasons for a high ranking were linked to income, e.g., fish, and usefulness, e.g., zebu as working tool, while interviewees justified the lowest ranking for wild ducks by being “difficult to hunt” and “forbidden to hunt.” For H. alaotrensis, the explanations for the least important ranking were that it is a “protected species” and “forbidden to hunt” (Table IV).

Ranking of animals by importance (1 = very important to 7 = not important at all) by 50 participants from the village of Andreba in 2015. We summarized ranks 1–3 and 5–7 for simplicity; see Fig. S3 for a detailed breakdown of rankings.

Discussion

Encouragingly, 89% of the people we surveyed around Lake Alaotra were aware of the existence of Hapalemur alaotrensis. Most participants could describe the lemur’s appearance, but fewer than half of the respondents could provide more detailed characteristics such as its diet. Years of schooling did not have a significant influence on levels of awareness and knowledge of H. alaotrensis. To the contrary, fishers exhibited the highest levels of knowledge and awareness despite having the lowest educational levels. Awareness and knowledge of participants from the city of Ambatondrazaka were lower than those of participants in the smaller, remote villages around the lake, although participants from the city had the highest levels of schooling. This supports findings by Reibelt et al. (2014) that the local natural environment is usually not addressed in primary schools in the region, a situation replicated throughout Madagascar (Dolins et al. 2010; Ratsimbazafy 2003; Reibelt et al. 2017).

A majority (86%) of the people we surveyed had seen Hapalemur alaotrensis at some time during their lives. This is likely representative of people living at or working on the border of, or close to and in the marshes and highlights local communities’ reliance on the marshes. Participants from all the surveyed villages had seen lemurs in the marshes, mainly in groups of two to four or more individuals. This shows that there still are patches of quality habitat for H. alaotrensis outside Park Bandro, and it is critical to protect and reconnect such key areas of marsh habitat to ensure the species’ survival in the long term.

Although 64% of respondents were concerned with the decline of Hapalemur alaotrensis, some felt that the decline was unimportant while others believed that its decline is a myth. Real-life experiences shape environmental attitudes, and are believed to be stronger than indirect experiences such as specific programs or learning in school aiming to change attitudes (Newhouse 1990; Rajecki 1982). This should be considered when shaping educational interventions. If local resource users learn or are told by nongovernmental organizations and educators that H. alaotrensis is highly threatened, but encounter these individuals on a regular basis in their environment due to the species being locally common in small fragments, they may not believe other messages from conservation organizations. This pattern seems to be confirmed in Andreba, where lemur encounters are most common because of the proximity to Park Bandro. No participants from this site explained their concern about H. alaotrensis with the species’ risk of extinction while 42% of all survey participants did.

People in general are attached to the environments they live and work in and can provide information on wildlife in these areas (Gandiwa 2012). In the Alaotra region, the marshes are a cultural heritage and its unique biodiversity creates prestige for the region. For many local people the marshes are a working environment needed for survival (Waeber et al. 2017c). Positive experiences in the natural environment lead to environmental awareness and concern (Chawla 1998), but in settings where people’s dependency on natural resources is high, the experience of loss and degradation of their environment can also lead to increased concern (Korhonen and Lappalainen 2004).

Our results demonstrate that fishers were the most knowledgeable local resource users and were more concerned about the decline and possible extinction of Hapalemur alaotrensis than nonfishers. Fishers are in the marshes and on the lake daily, and appear to have an intimate link to these ecosystems. Their experiences and frequent contact with wildlife have increased their awareness of the species’ existence and shaped positive attitudes toward them. We recommend further studies to explore in more detail the knowledge and perceptions of the various stakeholder groups, given that most inhabitants of the Alaotra region rely on several professions to pursue their livelihoods (Rakotoarisoa et al. 2015).

While fishers can be a valuable stakeholder in lemur conservation at Lake Alaotra, the extent to which different resource users, including fishers, are involved in lemur hunting at Alaotra is unclear. Trapping of Hapalemur alaotrensis was a major concern at Alaotra in the 1990s (Mutschler et al. 2001) and although this has declined significantly in recent years as a result of conservation efforts, there is anecdotal evidence that lemur trapping has begun to rise again with increased marsh fragmentation. Rapid social change leading to the degradation of historical taboos has resulted in an escalation in lemur hunting for bushmeat throughout Madagascar (Golden 2009; Jenkins et al. 2011; Reuter et al. 2016). Gardner and Davies (2014) found that bushmeat collection was primarily carried out opportunistically by people entering the forest for other reasons, rather than by specialist hunters. During the current study, 10% of people surveyed stated that they had seen H. alaotrensis in captivity at some point during their life, although there was a major difference between the city of Ambatondrazaka and Andreba, the village closest to Park Bandro. Forty-five percent of people surveyed in the city had seen H. alaotrensis in captivity compared to 0% in Andreba. To better understand dynamics among user groups and potential risks linked to poaching, we recommend that research be carried out at Alaotra to determine the typology of poachers, motivations, and the extent of collection of H. alaotrensis. The literature review by Muth and Bowe (1998) may provide a useful heuristic framework for empirical studies in the Alaotra, while this knowledge can then be incorporated within regional lemur conservation and environmental education programs.

We found a link among environmental knowledge, awareness, and concern, with distance in both a literal and figurative sense. The more often people encounter Hapalemur alaotrensis, the more they know about it, and the more likely they are to be concerned about its future. This is most obvious in the sites Andreba, Ambatosoratra, and Angoja which are the three closest to the park, where the highest lemur densities occur. In the city (Ambatondrazaka), where people have the highest educational levels but no direct access to the marsh, people know the least about H. alaotrensis. Half of the interviewees in the city replied “I don’t know” when asked whether they were concerned about population decline of H. alaotrensis, suggesting that they have a weak relation to the lemur. In Anororo and Vohimarina, despite knowledge levels similar to those in the other villages, about half of the interviewees said they were not concerned about the declining numbers of the lemur. It is not clear whether this is related to fewer lemur encounters in their marshes, to social tensions between pro and contra conservation groups in these villages, or to other factors.

Waeber et al. (2017c) reported a strong negative effect of distance on local peoples’ awareness levels of the high-priority conservation zone Park Bandro, which can be explained by the fact that Park Bandro is a single site, whereas lemur encounters as in the current study are possible throughout the marshes surrounding Lake Alaotra. Studies elsewhere have also reported a significant influence of distance on awareness of and attitudes toward wildlife and other natural resources. At Manompana in eastern Madagascar, interest in the preservation of forest fragments was related to walking distance between people’s homes and forest resources (Urech et al. 2012). People closer to forest fragments were more appreciative of the benefits provided by those fragments. In Kenya, proximity to a national reserve significantly increased positive attitudes toward conservation of the reserve in community members (Shibia 2010). Similarly, in the United States, distance was a significant factor in explaining knowledge and perceptions of residents concerning two creeks in Texas (Brody et al. 2004). In contrast, studies in Ecuador (Fiallo and Jacobson 1995) and Botswana (Parry and Campbell 1992) found increasingly negative attitudes with decreasing distance to protected areas. Negative attitudes were primarily based on the perceived negative influence of animals foraging on crops, land-use restrictions, and loss of land or livestock. Similar negative attitudes and perceptions were reported in various studies in settings with human–wildlife conflicts (Hill 1998; Hill and Webber 2010; Lee and Priston 2005; Oli et al. 1994). These different findings suggest that contact with wildlife can shape attitudes and perceptions both positively and negatively, depending on the nature of the experience. Neither Park Bandro nor Hapalemur alaotrensis carry negative connotations, likely because they are not perceived to have a restrictive impact on the primary natural resource uses of residents around Lake Alaotra. This is similar to the attitudes of local residents toward black howlers (Alouatta nigra) and a conservation sanctuary for their protection in Belize (Alexander 2000). Local people supported the conservation of the howler and its habitat but also stated that there was no negative impact on their lives associated with the sanctuary.

The fact that distance to Park Bandro also influences awareness of the lemur, and not only on knowledge and awareness of Park Bandro (Waeber et al. 2017a, b, c), may be due to the increased conservation efforts and awareness raising campaigns by conservation organizations such as Madagascar Wildlife Conservation and the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust who have focused much of their environmental awareness and education work around Park Bandro. At the same time, this highlights a challenge in undeveloped and economically depressed areas like Madagascar where infrastructure and means of communication are poorly developed. It suggests that communication tools that are more effective in reaching wider areas need to be prioritized around Lake Alaotra, for example, communication outreach workshops targeting specific segments of a society (Steinmetz et al. 2014).

Fish and zebu cattle were identified as culturally, socially, and economically significant. Fish is an important source of income and zebu are valuable working animals for agriculture and transport. Animals that provided direct benefits for subsistence and economic, e.g., fish, and/or social, e.g., zebu, well-being, the latter of which also represent social prestige (Kaufmann and Tsirahamba 2006), ranked the highest. Hapalemur alaotrensis and waterfowl (wild and domestic ducks) ranked lowest in terms of value, as they are either under protection and illegal to hunt, or they are difficult to catch or breed. The low ranking of H. alaotrensis suggests that the creation of Park Bandro as an ecotourism site where visitors can stay and pay to observe the lemur in the marshes has not provided a sense of economic importance of the lemur to people in Andreba. This may be because tourist numbers are too low to be economically significant (Rendigs et al. 2015) and it can also be challenging to understand how benefits from ecotourism interact with other economic, social, and cultural values (Waylen et al. 2009). Local people at Alaotra appear to prioritize direct livelihood benefits over conservation values. For example, despite the negative ecological impact of the invasive fish Channa maculata (Copsey et al. 2009a), primary school teachers in the Alaotra region did not perceive this to be an environmental problem, because it provided a source of food (Reibelt et al. 2014). Unless conservation and sustainable development projects ensure more than a minimal and short-term socioeconomic benefit, local people in areas with high levels of rural poverty will be unable to change their way of living (Marcus 2001).

Since the political crisis in Madagascar in 2009, the conversion of marshlands has been accelerated by wealthy and powerful nonlocal individuals who do not rely on local resources for survival. This has been facilitated by the vulnerability of the rural poor to follow illegal activities on behalf of these powerful individuals who are mostly based in the big cities (Ratsimbazafy et al. 2013; Waeber and Wilmé 2013), low levels of law enforcement, and the lack of formal legal protection for the marshes prior to the permanent status granted for the Lake Alaotra New Protected Area in June 2015. The combination of these factors has brought Hapalemur alaotrensis to the brink of extinction. However, the concern for the future of H. alaotrensis in villages around Lake Alaotra is encouraging and local people are also willing to discuss conservation zones, as long as areas are designated where they can pursue their daily livelihood activities such as fishing or rice farming (Waeber et al. 2017c). Fishers, in particular, preferred clear and effectively managed zoning for the benefit of resource users and biodiversity, including H. alaotrensis. Fishers prefer many, small no-take zones that correspond with important fish spawning areas (Wallace et al. 2015, 2016), confirming their awareness of the links among marsh vegetation, fish reproduction, and livelihood benefits to the fisher communities at Lake Alaotra. In Zambia, as awareness of the consequences of environmental degradation on livelihoods increased, so too did the likelihood of behavioral change by small-scale farmers to reduce the degradation (Wu and Mweemba 2010). This suggests that awareness raising and educational campaigns should target specific groups in the communities around Lake Alaotra, such as farmers, to increase the collective readiness to respect conservation areas and change behaviour. Increased contact with nature led to increased positive attitudes toward nature in children (increased biophilia and decreased biophobia), and biophilia significantly influenced their willingness for animal conservation in China (Zhang et al. 2014). Moreover, in line with the city–villages divide suggested by our study, children in urban areas had less biophilia and less readiness for conservation than most children from rural areas with more nature contact (Zhang et al. 2014).

The fact that local people are willing to discuss conservation zonation at Lake Alaotra provides hope for the future conservation of Hapalemur alaotrensis. However, conservation and development organizations need to ensure alignment between resource management planning and local community needs to avoid a disconnection between conservation policy and community needs. Such a disconnection has reduced the effectiveness of large-scale and long-term international and nation-wide conservation and development efforts in Madagascar in the past (Waeber et al. 2016). Restricting local livelihood needs also increases the risk of human–wildlife conflicts which could facilitate a shift toward negative perceptions of wildlife, and conservation in general.

Our findings for Lake Alaotra can also inform conservation in other regions of Madagascar. However, conservation planning is context dependent and it is important not to simplify cultural aspects (Keller 2009). Nevertheless, taboos can have important impacts on local perceptions and attitudes in Madagascar and are different from region to region (Lingard et al. 2003; Mittermeier et al. 1994; Rakotomamonjy et al. 2015; Ramanantsoa 1984).

Although based on a modest sample size of 230 participants, our study identified trends in local community knowledge, awareness, and perceptions of Hapalemur alaotrensis. We found differences between fishers and nonfishers and a negative correlation between levels of knowledge and distance from the high-priority conservation zone Park Bandro. People who encountered the lemur most often showed the highest levels of awareness and concern for the lemur’s future. Qualitative research examining people’s perceptions and priorities should be expanded at Lake Alaotra beyond fishers and farmers to provide further evidence of trends in conservation attitudes among a wider group of stakeholders. Community values, perceptions, and knowledge of H. alaotrensis should be used to guide future conservation planning, environmental education, and livelihood improvement activities at Lake Alaotra. The marshes and the Lake Alaotra gentle lemur can be protected only if local resource users are part of the solution and conservation and development organizations utilize information gained through qualitative studies to align resource users’ concerns and livelihood needs with biodiversity values.

References

Agrawal, A., & Gibson, C. C. (1999). Enchantment and disenchantment: The role of community in natural resource conservation. World Development, 27, 629–649.

Alexander, S. (2000). Resident attitudes toward conservation and black howler monkeys in Belize: The community baboon sanctuary. Environmental Conservation, 27(4), 341–350.

Andrianandrasana, H. T., Randriamahefasoa, J., Durbin, J., Lewis, R. E., & Ratsimbazafy, J. H. (2005). Participatory ecological monitoring of the Alaotra wetlands in Madagascar. Biodiversity and Conservation, 14, 2757–2774.

Bakoariniaina, L. N., Kusky, T., & Raharimahefa, T. (2006). Disappearing Lake Alaotra: Monitoring catastrophic erosion, waterway silting, and land degradation hazards in Madagascar using Landsat imagery. Journal of African Earth Science, 44, 241–252.

Ballhorn, D. J., Rakotoarivelo, F. P., & Kautz, S. (2016). Coevolution of cyanogenic bamboos and bamboo lemurs on Madagascar. PloS One, 11(8), e0158935.

Bernard, H. R. (2006). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). Walnut Creek: Alta Mira Press.

Brody, S. D., Highfield, W., & Alston, L. (2004). Does location matter? Measuring environmental perceptions of creeks in two San Antonio watersheds. Environment and Behavior, 36(2), 229–250.

Chawla, L. (1998). Significant life experiences revisited: A review of research on sources of environmental sensitivity. Journal of Environmental Education, 29, 11–21.

Copsey, J. A., Jones, J. P. G., Andrianandrasana, H. T., Rajaonarison, L. H., & Fa, J. E. (2009a). Burning to fish: Local explanations for wetland burning in lac Alaotra, Madagascar. Oryx, 43, 403–406.

Copsey, J. A., Rajaonarison, L. H., Randriamihamina, R., & Rakotoniaina, L. J. (2009b). Voices from the marsh: Livelihood concerns of fishers and rice cultivators in the Alaotra wetland. Madagascar Conservation & Development, 4(1), 24–30.

Dolins, F. L., Jolly, A., Rasamimanana, H., Ratsimbazafy, J., Feistner, A. T. C., et al (2010). Conservation education in Madagascar: three case studies in the biologically diverse island-continent. American Journal of Primatology, 72(5), 391–406.

Drury, R., Homewood, K., & Randall, S. (2011). Less is more: The potential of qualitative approaches in conservation research. Animal Conservation, 14, 18–24.

Fiallo, E. A., & Jacobson, S. K. (1995). Local communities and protected areas: Attitudes of rural residents towards conservation and Machalilla National Park, Ecuador. Environmental Conservation, 22(3), 241–249.

Gandiwa, E. (2012). Local knowledge and perceptions of animal population abundances by communities adjacent to the northern Gonarezhou National Park, Zimbabwe. Tropical Conservation Science, 5(3), 255–269.

Ganzhorn, J. U., Lowry, P. P., Schatz, G. E., & Sommer, S. (2001). The biodiversity of Madagascar: One of the world’s hottest hotspots on its way out. Oryx, 35(4), 346–348.

Gardner, C. J., & Davies, Z. G. (2014). Rural bushmeat consumption within multiple-use protected areas: Qualitative evidence from southwest Madagascar. Human Ecology, 42, 21–34.

Golden, C. D. (2009). Bushmeat hunting and use in the Makira Forest, north-eastern Madagascar: A conservation and livelihoods issue. Oryx, 43(3), 386–392.

Hill, C. M. (1998). Conflicting attitudes towards elephants around the Budongo Forest reserve, Uganda. Environmental Conservation, 25(3), 244–250.

Hill, C. M., & Webber, A. D. (2010). Perceptions of nonhuman primates in human–wildlife conflict scenarios. American Journal of Primatology, 72(10), 919–924.

INSTAT. (2012). Institut National de la Statistique de Madagascar. http://instat.mg/?option=com_content&view=article&id=33&Itemid=56 (Accessed March 16, 2016).

IUCN. (2014). Andriaholinirina, N., Baden, A., Blanco, M., Chikhi, L., et al. (2014) Hapalemur alaotrensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. doi: 10.2305/iucn.uk.2014-1.rlts.t9676a16119362.en (Accessed March 16, 2016).

Jenkins, R. K. B., Keane, A., Rakotoarivelo, A. R., Rakotomboavonjy, V., Randrianandrianina, F. H., et al (2011). Analysis of patterns of bushmeat consumption reveals extensive exploitation of protected species in eastern Madagascar. PloS One, 6(12), e27570.

Kaufmann, J. C., & Tsirahamba, S. (2006). Forests and thorns: Conditions of change affecting Mahafale pastoralists in southwestern Madagascar. Conservation and Society, 4, 231–261.

Keller, E. (2009). The danger of misunderstanding ‘culture’. Madagascar Conservation & Development, 4(2), 82–85.

Korhonen, K., & Lappalainen, A. (2004). Examining the environmental awareness of children and adolescents in the Ranomafana region, Madagascar. Environmental Education Research, 10, 195–216.

Lamnek, S. (2005). Qualitative Sozialforschung (4th edition). Weinheim: Lehrbuch. Beltz.

Lee, P. C., & Priston, N. E. (2005). Human attitudes to primates: Perceptions of pests, conflict and consequences for primate conservation. Commensalism and conflict: The human-primate interface, 4, 1–23.

Lingard, M., Raharison, N., Rabakonandrianina, E., Rakotoarisoa, J.-A., & Elmqvist, T. (2003). The role of local taboos in conservation and management of species: The radiated tortoise in southern Madagascar. Conservation and Society, 1, 223–246.

Maminirina, C. P., Girod, P., & Waeber, P. O. (2006). Comic strips as environmental educative tools for the Alaotra region. Madagascar Conservation & Development, 1(1), 11–14.

Marcus, R. (2001). Seeing the forest for the trees: Integrated conservation and development projects and local perceptions of conservation in Madagascar. Human Ecology, 29, 381–397.

Mehta, J. N., & Kellert, S. R. (1998). Local attitudes toward community-based conservation policy and programmes in Nepal: A case study in the Makalu-Barun conservation area. Environmental Conservation, 25(4), 320–333.

Mittermeier, R. A., Tattersall, I., Konstant, W. R., Meyers, D. M., Mast, R. B., & Nash, S. D. (1994). Lemurs of Madagascar. Washington, DC: Conservation International.

Mittermeier, R. A., Ganzhorn, J. U., Konstant, W. R., Glander, K., Tattersall, I., et al (2008). Lemur diversity in Madagascar. International Journal of Primatology, 29(6), 1607–1656.

Mittermeier, R. E., Louis Jr., E. E., Langrand, O., Schwitzer, C., Gauthier, C. A., et al (2014). Lémuriens de Madagascar. In Publications scientifiques du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle. Paris: Conservation International.

Muth, R. M., & Bowe Jr., J. F. (1998). Illegal harvest of renewable natural resources in North America: Toward a typology of the motivations for poaching. Society & Natural Resources, 11(1), 9–24.

Mutschler, T., & Feistner, A. T. C. (1995). Conservation status and distribution of the Alaotran gentle lemur Hapalemur griseus alaotrensis. Oryx, 29, 267–274.

Mutschler, T., Feistner, A. T. C., & Nievergelt, C. M. (1998). Preliminary field data on group size, diet and activity in the Alaotran gentle lemur Hapalemur griseus alaotrensis. Folia Primatologica, 69(5), 325–330.

Mutschler, T., Randrianarisoa, A. J., & Feistner, A. T. C. (2001). Population status of the Alaotran gentle lemur Hapalemur griseus alaotrensis. Oryx, 35, 152–157.

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., Da Fonseca, G. A., & Kent, J. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature, 403(6772), 853–858.

Nepal, S., & Spiteri, A. (2011). Linking livelihoods and conservation: An examination of local residents’ perceived linkages between conservation and livelihood benefits around Nepal’s Chitwan national park. Environmental Management, 47(5), 727–738.

Newhouse, N. (1990). Implications of attitude and behavior research for environmental conservation. Journal of Environmental Education, 2(1), 26–32.

Nyaupane, G. P., & Poudel, S. (2011). Linkages among biodiversity, livelihood, and tourism. Annuals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1344–1366.

Oli, M. K., Taylor, I. R., & Rogers, M. E. (1994). Snow leopard Panthera uncia predation of livestock: An assessment of local perceptions in the Annapurna conservation area, Nepal. Biological Conservation, 68(1), 63–68.

Parry, D., & Campbell, B. (1992). Attitudes of rural communities to animal wildlife and its utilization in Chobe enclave and Mababe depression, Botswana. Environmental Conservation, 19(3), 245–252.

Rajecki, D. W. (1982). Attitudes: Themes and advances. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates.

Rakotoarisoa, T. F., Waeber, P. O., Richter, T., & Mantilla Contreras, J. (2015). Water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), opportunity or threat for the Alaotra wetlands and livelihoods. Madagascar Conservation & Development, 10(S3), 128–136.

Rakotomamonjy, S. N., Jones, J. P. G., Razafimanahaka, J. H., Ramamonjisoa, B., & Williams, S. J. (2015). The effects of environmental education on children’s and parents’ knowledge and attitudes towards lemurs in rural Madagascar. Animal Conservation, 18(2), 157–166.

Ralainasolo, F. B. (2004). Influence des effets anthropiques sur la dynamique de la population de Hapalemur griseus alaotrensis ou “Bandro” dans son habitat naturel. Lemur News, 9, 32–35.

Ralainasolo, F. B., Waeber, P. O., Ratsimbazafy, J., Durbin, J., & Lewis, R. (2006). The Alaotra gentle lemur: Population estimation and subsequent implications. Madagascar Conservation & Development, 1(1), 9–10.

Ramanantsoa, G. A. (1984). The Malagasy and the chameleon: A traditional view of nature. In A. Jolly, P. Oberlé, & R. Albignac (Eds.), Key environments: Madagascar. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Ranarijaona, H. L. T. (2007). Concept de modèle écologique pour la zone humide Alaotra. Madagascar Conservation & Development, 2, 35–42.

Ratsimbazafy, J. (2003). Lemurs as the most appropriate and best didactic tool for teaching. Lemur News, 8, 19–21.

Ratsimbazafy, J. R., Ralainasolo, F. B., Rendigs, A., Mantilla-Contreras, J., Andrianandrasana, H., et al (2013). Gone in a puff of smoke? Hapalemur alaotrensis at great risk of extinction. Lemur News, 17, 14–18.

Reibelt, L. M., Richter, T., Waeber, P. O., Rakotoarimanana, S. H. N. H., & Mantilla Contreras, J. (2014). Environmental education in its infancy at Lake Alaotra, Madagascar. Madagascar Conservation & Development, 9(2), 71–82.

Reibelt, L. M., Richter, T., Rendigs, A., & Mantilla Contreras, J. (2017). Malagasy conservationists and environmental educators: Life paths into conservation. Sustainability, 9(2), 227.

Rendigs, A., Reibelt, L. M., Ralainasolo, F. B., Ratsimbazafy, J. H., & Waeber, P. O. (2015). Ten years into the marshes–Hapalemur alaotrensis conservation, one step forward and two steps back? Madagascar Conservation & Development, 10(1), 13–20.

Reuter, K. E., Gilles, H., Wills, A. R., & Sewall, B. J. (2016). Live capture and ownership of lemurs in Madagascar: Extent and conservation implications. Oryx, 50(2), 344–354.

Salafsky, N., & Wollenberg, N. (2000). Linking livelihoods and conservation: A conceptual framework and scale for assessing the integration of human needs and biodiversity. World Development, 28(8), 1421–1438.

Schwitzer, C., Mittermeier, R. A., Davies, N., Johnson, S., Ratsimbazafy, J., et al (2013). Lemurs of Madagascar: A strategy for their conservation 2013–2016. Bristol: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation, and Conservation International.

Setchell, J. M., Fairet, E., Shutt, K., Waters, S., & Bell, S. (2016). Biosocial conservation: Integrating biological and ethnographic methods to study human–primate interactions. International Journal of Primatology. doi:10.1007/s10764-016-9938-5.

Shibia, M. G. (2010). Determinants of attitudes and perceptions on resource use and management of Marsabit National Reserve, Kenya. Journal of Human Ecology, 30(1), 55–62.

Steinmetz, R., Srirattanaporn, S., Mor-Tip, J., & Seuaturien, N. (2014). Can community outreach alleviate poaching pressure and recover wildlife in south-east Asian protected areas? Journal of Applied Ecology, 51, 1469–1478.

Tattersall, I. (2013). Understanding species-level primate diversity in Madagascar. Madagascar Conservation & Development, 8(1), 7–11.

Thalmann, U. (2006). Lemurs: Ambassadors for Madagascar. Madagascar Conservation & Development, 1(1), 4–8.

Urech, Z. L., Felber, H. R., & Sorg, J.-P. (2012). Who wants to conserve remaining forest fragments in the Manompana corridor? Madagascar Conservation & Development, 7(3), 135–143.

Waeber, P. O., & Wilmé, L. (2013). Madagascar rich and intransparent. Madagascar Conservation & Development, 8, 52–54.

Waeber, P. O., Wilmé, L., Ramamonjisoa, B., Garcia, C., Rakotomalala, D., et al (2015). Dry forests in Madagascar: Neglected and under pressure. International Forestry Review, 17(S2), 127–148.

Waeber, P. O., Wilmé, L., Mercier, J.-R., Camara, C., & Lowry, P. P. (2016). How effective have thirty years of internationally driven conservation and development efforts been in Madagascar? PloS One, 11(8), e0161115.

Waeber, P. O., Ratsimbazafy, J. H., Andrianandrasana, H., Ralainasolo, F. B., & Nievergelt, C. M. (2017a). Hapalemur alaotrensis, a conservation case study from the swamps of Alaotra, Madagascar. In Primates in flooded habitats: Ecology and conservation. Cambridge University Press. In press.

Waeber, P. O., Ralainasolo, F. B., Ratsimbazafy, J. H., & Nievergelt, C. M. (2017b). Consequences of lakeside living for the diet and social ecology of the Alaotran gentle lemur. In Primates in flooded habitats: Ecology and conservation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. In press.

Waeber, P. O., Reibelt, L. M., Randriamalala, I. H., Moser, G., Raveloarimalala, L. M., et al (2017c). Local awareness and perceptions: Consequences for conservation of marsh habitat at Lake Alaotra for one of the world’s rarest lemurs. Oryx. doi:10.1017/S0030605316001198.

Wallace, A. P. C., Milner-Gulland, E. J., Jones, J. P. G., Bunnefeld, N., et al (2015). Quantifying the short-term costs of conservation interventions for fishers at Lake Alaotra, Madagascar. PloS One, 10(6), e0129440.

Wallace, A. P. C., Jones, J. P., Milner-Gulland, E. J., Wallace, G. E., et al (2016). Drivers of the distribution of fisher effort at Lake Alaotra, Madagascar. Human Ecology, 44(1), 105–117.

Waylen, K. A., McGowan, P. J. K., Pawi Study Group, & Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2009). Ecotourism positively affects awareness and attitudes but not conservation behaviours: A case study at Grande Riviere, Trinidad. Oryx, 43(3), 343–351.

Wilmé, L., Waeber, P. O., Moutou, F., Gardner, C. J., et al (2016). A proposal for ethical research conduct in Madagascar. Madagascar Conservation & Development, 11(1), 36–39.

Wu, H., & Mweemba, L. (2010). Environmental self-efficacy, attitude and behavior among small scale farmers in Zambia. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 12(5), 727–744.

Zhang, W., Goodale, E., & Chen, J. (2014). How contact with nature affects children’s biophilia, biophobia and conservation attitude in China. Biological Conservation, 177, 109–116.

Acknowledgements

We thank all study participants and our research assistants Vanessa Gisèle Aimée Rakotomalala and Olivier Pascal Randriamanjakahasina. The support of the regional authorities Kiady Rakotondravoninala (regional director of the Ministry of Environment, Ecology, Sea and Forests), Samuel Razafindrabe (regional director of the Ministry of Agriculture) and Herilalaina Andrianantenaina (regional director of the Ministry of Fisheries) is acknowledged. Thanks to the two anonymous reviewers whose comments helped to improve the article and a special thanks to the editor-in-chief for her great support and editing. This research was funded by the Margot Marsh Biodiversity Foundation under research grant PR15-021, and the Swiss Programme for Research on Global Issues for Development under research grant IZ01Z0_146852 as part of the AlaReLa Alaotra Resilience Landscape project.

L. M. Reibelt, P. O. Waeber, and I. H. Randriamalala conceived and designed the study. I. H. Randriamalala, L. M. Raveloarimalala, and F. B. Ralainasolo administered the questionnaires. G. Moser, L. M. Reibelt, and P. O. Waeber analyzed the data. L. M. Reibelt, L. Woolaver, P. O. Waeber, G. Moser, I. H. Randriamalala, and J. Ratsimbazafy wrote the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Joanna M. Setchell

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 106 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reibelt, L.M., Woolaver, L., Moser, G. et al. Contact Matters: Local People’s Perceptions of Hapalemur alaotrensis and Implications for Conservation. Int J Primatol 38, 588–608 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-017-9969-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-017-9969-6