Abstract

We draw upon the evolutionary model of change in order to examine the organizational transformation of three liberal arts colleges (Albion College, Allegheny College, Kenyon College). Relying on our prior research (Baker, Baldwin, & Makker, 2012), we seek to continue our exploration and understanding of the evolution occurring in the important liberal arts college sector of higher education. We seek to understand why and how these colleges change, what changes occur, and, especially, what makes liberal arts colleges susceptible to change. The findings of this study have the potential to illuminate change in other types of higher education institutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Dramatic change is underway throughout higher education; and, at times, the changes are not trivial (Hearn, 1996). Among the forces that account for recent changes are technology, new teaching and learning approaches, cost constraints, changing demographics, and international competition (Kezar, 2001). The consequences of these changes are particularly apparent in the “distinctively American” (Lang, 1999, p. 133) liberal arts college (LAC). In this article, we seek to extend our previous work on the evolution of liberal arts colleges (Baker et al., 2012) to determine whether this sector of higher education is, in fact, disappearing from the higher education landscape as many one-time liberal arts colleges close or evolve into ”professional colleges” (Breneman, 1990). With our study we wished to determine if what we are seeing would be appropriately described as evolutionary change resulting in a redefinition of what a liberal arts college education means in the twenty-first century. We also wanted to clarify the forces and factors contributing to the change process that is occurring.

Clear evidence confirms that liberal arts colleges are changing and moving in new directions. Many are compelled to develop a clear “brand” identity in an effort to differentiate themselves from their competition (Rodgers and Jackson, 2012). Returning to Breneman’s research nearly 25 years later, we confirmed that the number of liberal arts colleges continues to decrease, according to his definition, with only 130 institutions remaining from the 212 he originally reported in 1990 (Baker et al., 2012). Freeland (2009) wrote of a challenge to the version of liberal education (based almost exclusively in arts and science fields) that was the prototype for a liberal arts college education for most of the 20th century. In its place, many LACs have added academic programs in vocationally-oriented fields (e.g., business, nursing) and supplemented traditional classroom learning strategies with technology-enhanced instruction and with out-of-class learning opportunities (e.g., internships, service learning).

Changes in liberal arts colleges are not an isolated phenomenon. All types of higher education institutions confront powerful forces that require adjustments in their programs; delivery systems; and, sometimes, even in their basic missions. Kezar (2001) noted that higher education institutions do, in fact, change and that there is a need to better understand how, why, and under what circumstances such changes occur. Our aim is to rely on the evolutionary model of change as a theoretical framework to explore the transformations we identified that are occurring in LACs (Baker et al., 2012). We believe the evolutionary model of change to be particularly appropriate because it a) emphasizes the role of external influences, b) acknowledges that the process of change is slow, c) addresses the structural- and process-based nature of change, and d) recognizes the inextricable connection of change to resources and strategic imperatives. We relied on our national longitudinal data (Baker et al., 2012) on changes in liberal arts colleges as well as case studies of three LACs -- Albion College, Allegheny College, and Kenyon College. The questions we explored were as follows.

-

How and why do LACs change?

-

What makes LACs susceptible to change (e.g., responsiveness to market forces, changing regional and national environments)?

-

What are the outcomes of forces promoting change among LACs?

Relevant Literature

In Stark and Lowther’s (1988) report, which is entitled Strengthening the Ties that Bind, the authors discussed a long-standing debate that is fundamental to American higher education – “how to integrate liberal and professional study effectively building upon the best that each has to offer” (p. 16). This question has held the attention of researchers, faculty, and administrators and has continued to persist within all institution types. At present approximately 60 % of undergraduate degrees awarded are in occupational fields, and this line of research has revealed a long-term historical trend toward more professional education (Brint, Riddle, Turk-Bicakci, & Levy, 2005).

Liberal arts colleges, most notably, have struggled with this tension. In today’s 21st century world, there is an increased need for highly specialized knowledge and a demand for more vocationally-oriented educational programs and degrees. However, technical training and skill development alone are not enough to ensure that students develop the habits of mind and spirit necessary to be life-long learners; engaged citizens; and effective, adaptable leaders. How to balance the best of liberal and professional education remains a vigorous source of dialogue and debate in the higher education community (Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2011; Humphreys & Kelly, 2014).

The history of American higher education is rich with evidence that institutional missions, programs, and even values and principles change over time (Brint et al., 2005; Gumport, 2000; Hartley, 2003; Hartley & Schall, 2005; Morphew, 2002). Hartley and Schall (2005) reported that certain educational values gain ascendancy during particular periods, and institutions struggle periodically to redefine their purpose. This is part of a necessary effort from time to time to refit or revitalize institutions. While the missions of successful colleges may remain rooted in core values, they still must adapt to changing demographic and environmental conditions (Hartley, 2003; Hartely & Schall, 2005). Part of this change is rooted in the competitive pressures colleges encounter in the U.S. educational marketplace. In order to compete for resources such as students and revenue, many liberal arts colleges have added professional programs to their curriculum. As Martin (1984) observed 30 years ago, “Liberal arts colleges are a curious mixture of traditions and innovation” (p.287). The continuous debate over the mission and curriculum of the liberal arts college is “the endless good argument” as Hartley & Schall (2005, p. 11) described it.

In a related trend, some observers (Morphew, 2009) have verified a gradual decline in institutional diversity in U.S. higher education. For example, Morphew (2002) documented a large number of former colleges that have added programs and changed their names from “college” to “university” in recent years. Essentially, these institutions redefined their identity to become more like comprehensive universities. In so doing, these institutions became less sharply focused than they had been. This decline in institutional diversity may be attributable to the adjustments and compromises institutions must make in a dynamic environment. Morphew (2009) viewed this as a disturbing trend as diversity has generally been regarded as one of the key strengths of our U.S. system of colleges and universities. Morphew argued that diverse systems are likely to be more responsive to the needs of diverse populations of learners and more cost effective than those that are not (Morphew, 2009). Interestingly, this trend to less institutional diversity has occurred in spite of major changes in the context of a higher education system that now serves more women, minority, part-time and older students (Kena, Johnson, Wang, Zhang, Rathbun, Wilkinson-Flicker, & Kristapovich, 2014; Morphew, 2009). This phenomenon of “academic drift,” as Morphew (2009) described it, is “the tendency of colleges and universities to ape the programmatic offerings of the most prestigious [institutions]” and “as the gravest threat to institutional diversity” (p. 246).

The reasons institutions change over time are varied and complex (Gumport, 2000; Hartley, 2003; Hartley & Schall, 2005; Loomis & Rodriguez, 2009; Morphew, 2002, 2009). Hence, it is not surprising that individual institutions, even within the same institutional classification, follow different paths as they move forward and work to remain viable in a turbulent and unpredictable environment. Morphew (2009) explained that institutions seek balance among the many demands and pressures they encounter. Traditional higher education institutions, such as liberal arts colleges, usually have a solid core of professionals (i.e., faculty, administrators, and staff) with strong ideas about mission, purpose, norms, and procedures and about what constitutes legitimate practice. The views of this internal core often compete with demands for adaptation, change, and reform that come from external forces and constituents such as the economy, technology, government regulations, parents, taxpayers, and donors (Morphew, 2009). Institutions typically seek equilibrium among these powerful and competing forces. Understanding this complex process calls for careful examination of institutional processes through an illuminating conceptual framework. In the following section, we explain the theoretical framework that served as a guide for our research – the evolutionary model of change.

Theoretical Framework

Kezar (2001) noted that “…higher education environments differ from other organizations that are highly vulnerable to the external environment” (p. 81); therefore, it is important to select appropriate models of change that account for such differences. We relied on the evolutionary model of change, focusing on the tenets as described by Kezar (2001), as an appropriate lens with which to explore the types of changes occurring among LACs because it provides insights into the manner with which organizations naturally make adjustments to adapt to their environments. In the following section, we briefly discuss the basic concepts of change, as outlined by Kezar (2001), in order to provide a common language with which to discuss the three institutional case studies we feature in this article. This common language addresses why change is occurring, what is changing, how change occurs, and what the outcomes or targets of that change are. We then provide a discussion of the tenets of the evolutionary model of change.

The two primary sources prompting organizational change are external and internal factors. The evolutionary model of change emphasizes the interplay between the external environment and the organization as critical to understanding why change is occurring. To determine the degree of change, or what is changing, Kezar discussed first and second-order changes. She defined first-order changes as minor adjustments or improvements, whereas second-order changes are transformational in nature and result in changes in mission and values. Additionally, understanding the timing of change (e.g., revolutionary or evolutionary), the scale of change (e.g., individual versus organizational level change), and the focus of change (e.g., organizational aspects affected by change) is also critical to addressing the “what question” of change. Responsiveness is an important consideration of change, particularly to understanding how change occurs and an institution’s response to that change. Institutional responses can be characterized as adaptive (e.g., one-time response), planned/managed (e.g., deliberately shaped by organizational members), proactive or reactive (e.g., happening before or after a crisis), and active or static (e.g., organizational member involvement or limited organizational member involvement). Finally, outcomes or targets of change can include new structures, processes, missions, rituals, and cultural changes.

In her review of typologies of organizational change, Kezar (2001) discussed the role of the evolutionary model of organizational change and the underlying assumptions and tenets associated with that model. The main assumption of the evolutionary model of change is that change is dependent on circumstances, situational variables, and the environment within which the organization operates. Institutions tend to manage rather than plan for change, prompting a survival response. Key tenets of evolutionary models of change include a) interaction between the organization and its environment; b) openness of the relationship between the environment and internal transformation, which is regarded as highly dependent on the external environment; c) homeostasis and, or self-regulation, which is particularly important given that it describes an institution’s ability to maintain a steady state; and d) evolution.

While we believe the evolutionary model of change to be the most appropriate theoretical frame through which to examine the institutional case studies presented in this manuscript, we believe it is also appropriate to acknowledge one of the major criticisms of this model, which is the minimized regard for internal factors as important influences and indicators of change. However, given that LACs are heavily dependent on fluctuations and changes in external influences (e.g., competition, consumerism, economic cycles) and are more vulnerable to market shifts and student/parent preferences than less tuition-driven institutions, it is our opinion that the evolutionary model of change has strong explanatory power in this sector of higher education (Cameron, 1991; Kezar, 2001).

Methods

In our prior research, we identified three trends among the LAC institutions that still meet Breneman’s (1990) classification criteria: (1) schools that have experienced no change in terms of percentage of professional degrees awarded, (2) schools that increased the percentage of professional degrees awarded, and (3) schools that decreased the percentage of professional degrees awarded over a twenty year period (Baker et al., 2012). While this research shed light on the current state of LACs and revealed that a process of evolution is underway, questions remain about the factors that influenced those changes. We therefore engaged in a purposeful sampling of three liberal arts institutions to supplement our past research. As such, we picked one institution from each of the trends noted above: Albion College (increase in professional degrees awarded), Allegheny College (decrease in professional degrees awarded), and Kenyon College (no change). We also selected these institutions because they are all members of the Great Lakes Colleges Association with member schools from Indiana, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Ohio; and they share somewhat similar institutional environments. We want to note, however, that, while Kenyon College experienced no change in terms of pre-professional or vocationally-oriented offerings, it has in fact made first and second order changes which we will discuss later in the article.

When we began this line of research we initially interviewed administrators, faculty members, and executive leaders in a range of academic and administrative areas resulting in a total of 24 interviews during phase one of data collection and analysis. Each institution selected the faculty members and arranged the interviews based on our request to speak with persons who had been employed by the institution for a significant time and had been involved in key institutional committees such as curriculum and resources, faculty development, and strategic planning. Each of these institutions was either undergoing or about to undergo leadership change. Given the leadership changes that subsequently occurred at these institutions, we completed an additional six interviews with administrators (i.e., presidents and academic deans) to ensure that we were working with the most recent information available. The addition of these interviews resulted in a total of 30 interviews which informed the case studies presented in this research. The 30 interviews were spread among the three institutions (Albion =11 interviews, Allegheny =10 interviews, Kenyon =9 interviews). IRB approval had been secured for all phases of this research.

We shared the interview protocol with each participant prior to the interview, and each set of questions was tailored to the individual’s institutional perspective. The interview protocol captured information about the following broad categories: context and institutional environment (e.g., What have been your institution’s priority concerns, challenges in the last five to ten years?), mission and academic programs (e.g., Has your curriculum changed in the past 5-10 years?, How do you balance the liberal arts mission of your institution with students’ vocational goals?), and recruitment and institutional advancement (e.g., Have you added or changed any academic programs to enhance your recruitment efforts?, What is the relationship between institutional advancement/development efforts and the college’s academic program?). We spent two days at each of the three sites conducting interviews; exploring the campus; and reading local publications to learn more about the campus, its traditions, and culture.

We relied on the broad interview categories to guide our data analysis efforts; and we employed an inductive data analysis strategy that involved iterating between and among data collection, data analysis, and the extant literature (Eisenhardt, 1989). This approach was particularly important given that our goal was to identify the key factors associated with change within LACs. We developed themes independently, compared notes, and agreed upon final themes on a per institution basis as part of the within case analysis. We also compared emergent themes with our prior research and other research that explored curricular and mission change within LACs. We created mini-case studies to develop per-institution themes (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Yin, 2008). We then used the broad categories noted above as a guide, but also relied on emergent themes from the data to develop additional coding categories. We next engaged in cross-case comparisons among the three institutions using the framework described in the Analysis section.

To ensure trustworthiness, we engaged in triangulation and member checks to confirm information shared during the interviews (Creswell, 2009). First, to ensure consistency across faculty members’ and administrator interviews, we relied on the same protocol for each interview. We reviewed each transcript for accuracy upon completion; and, when necessary, we cross checked transcripts against the actual recordings if statements were unclear. We also reviewed institutional strategic plans as well as institutional websites, press releases, and event transcripts (e.g., presidential inauguration) to ensure consistency among all sources of data. Lastly, we shared final drafts of institutional case studies with the current presidents and academic deans for fact checking purposes.

As with any research, inherent limitations exist. While each of these institutions was selected based on our prior quantitative analysis of trends among liberal arts colleges, we relied on convenience sampling given the geographical location of the three institutions and one of the study author’s connections to the Great Lakes Colleges Association. Second, generalizability is always a concern when conducting institutional case study research. Each of these institutions represented a trend, and the stories shared may not be generalizable to the other LACs in these categories (e.g., experienced no change, increased percentage of professional programs, decreased percentage of professional programs) or to other liberal arts colleges across the country. However, we believe our efforts to triangulate the data (e.g., interviews with faculty members and administrators, review of strategic plans) and complete member checks for accuracy have helped to manage these limitations appropriately.

Case Studies

Albion College (increased percentage of professional degrees awarded)

Founded with a pioneering heritage rooted in the Methodist tradition, Albion College is a mid-western liberal arts college located in Albion, Michigan. The College experienced rapid change in the 1800’s and 1900’s, which brought with it coeducation, increased enrollment, and the honor of being the first private college in Michigan to be awarded a chapter of Phi Beta Kappa. Within the past fifteen years, Albion has added several pre-professional programs and institutes, an award-winning first-year experience, and an undergraduate research program (FURSCA).

Albion College was in a time of transition after welcoming its first female president in 2007. Dr. Donna Randall Footnote 1began an intensive strategic planning process upon her arrival that coincided with the 2008 recession, resulting in challenges faced by the “Big Three” automobile companies and a struggling Michigan economy. She resigned from her Presidency after 6 years and moved into a new role as Chancellor of the College for a 1-year term. During the 2013-2014 academic year, Mike Frandsen served as Interim President, working towards developing a sense of community, both globally and locally, with a focus on relationships prior to the arrival of Albion’s next President, Dr. Mauri Ditzler, who joined the campus community in 2014. Frandsen characterized these relationships as strategic partnerships which touched upon the academic, operational, and communal aspects of the College.

A conversation with Albion’s Interim President and the Provost immediately began with the strengths of a liberal arts education with both individuals characterizing it as timeless. The College has adopted an integrated view of a liberal arts education in which they argue that a focus on career readiness is timely given the recent economic challenges and increased competition for students. “Academically, they [LACs] have defined themselves well over the years. The challenging piece, particularly in this environment, is the messaging” as Susan Conner, Albion’s Provost, noted.

Albion’s focus on strategic partnerships aims to strengthen academic programs, college operations, and the local and global communities with which they are involved. On a global scale, academic partnerships have evolved over the past five years that allow students and faculty members to travel abroad and experience the broader world. Institutional connections in France, for example, helped to broaden the global experiences for students, faculty and staff and enhance the academic offerings.

Operationally, one important strategic partnership that Albion recently entered into was with Bon Appetit Management Company. An alignment of values brought these two organizations together around a focus on nutrition and sustainability that is the cornerstone of Bon Appetit’s mission. During the past three years, Albion has supported “Theme Years” which addressed sustainability, wellness, and global diversity; and Bon Appetit has supported these themes through the dining experience on campus. Locally, Albion College students are actively engaged in philanthropic efforts. Approximately 55 % of Albion students engage in volunteer work in the community each academic year (e.g., mentors in public schools, youth sports clinics).

We asked each person interviewed two important, related questions. ”How has the mission of Albion changed in the past 10 years,” and how do you balance the traditional ideals of a liberal arts education with more vocationally-oriented fields and training?” All believed that the mission of the college had not changed in the past ten years; rather the changes that occurred were more an issue of articulating and implementing the mission in a more strategic way. Albion was and still is a liberal arts college that exposes its students to a breadth of disciplinary and interdisciplinary experiences; helps them develop strong analytical, communication, and conceptual skills; and encourages them to engage in social and political issues to develop their attitudes and skills as effective citizens. However, all interviewees said that they believed Albion’s institutional strategy had changed in recent years in connection with a need for greater transparency (i.e., branding of Albion College education in connection to the return on investment).

When discussing the issue of balance, many were quick to say they preferred not to use the word balance as it implies a tipping of sorts and that one of these areas (e.g., traditional liberal arts vs. vocationally-oriented training) would be dominant. Rather, many believed the more appropriate term and focus was on the successful integration of the traditional liberal arts with pre-professional training. This idea has been further honed given the integrated view of a liberal arts education with career readiness. During our interviews, a faculty member raised the following idea. “Is a liberal arts college education a process or approach to education more than exposure to certain fields?” This question supports Albion’s integrative approach, and it also supports Albion’s strategic goal of making a more explicit connection between educational programs offered by the College and job opportunities and graduate school programs.

We concluded our interviews by asking what the biggest challenges were for liberal arts colleges. The Albion participants kept coming back to the idea of differentiation and the need to offer a distinctive experience to attract and retain students. Several individuals talked about students wanting the small class sizes; the personalized attention; and the ability to participate in athletics, extra-curricular and co-curricular activities. Interim President Frandsen focused on the entire package of what Albion College has to offer as he helped the College seamlessly manage the transition, and he commented as follows.

We are in the business of providing opportunities and outcomes. In everything we do, we must seek to maximize those. We need to emphasize the benefits of what we do. We need to demonstrate that our students obtain great outcomes, in their first post-Albion experiences and in their lives.

Allegheny College (decrease in percentage of professional degrees awarded)

Allegheny College, located in Meadville, Pennsylvania, ranks among the oldest 1 % of colleges and universities in the United States. Approximately 2100 students attend the College, which is regarded as a “college that changes lives” according to Loren Pope (2013). It is ranked as the #1“Up-and-Comer” by U.S. News and World Report rankings of Top liberal arts colleges in the nation (2012). Allegheny’s brand, “Unusual Combinations,” attracts students with a mix of interests, while aptly describing many of its faculty members and also the institution itself, which “combines” academic rigor with a supportive environment.

Allegheny has undergone two major strategic planning processes since the mid-1990s, both of which were driven to some extent by a focus on career development. The first strategic plan, which covered the years 1998 – 2008, followed closely upon an institutional downsizing for financial reasons and established the Allegheny College Center for Experiential Learning (ACCEL), among other new initiatives. This new Center, which brought together internships, career services, international experiences, and service learning, can be understood as a direct result of the need to address student and parental concern about the practicality of the liberal arts.

In addition to the creation of ACCEL, Allegheny at that time also developed a national brand that was intended both to set it apart from other liberal arts colleges and to appeal to parents and students increasingly anxious about job prospects upon graduation. That brand, “Unusual Combinations, Extraordinary Outcomes,” is supported by a curriculum that requires students to have a major in one academic division and a minor in a second division.

Strategic planning has helped the College to determine budgeting priorities and allowed it to make difficult choices about the allocation of limited resources. Thus the College has continued to thrive, even during the recent recession. During a time when many colleges and universities were instituting salary freezes and layoffs, Allegheny College was firm in its commitment to reward the faculty and staff with raises. Enrollments remained strong, and new buildings arose. During the summer of 2009, Allegheny College embarked on its latest strategic planning initiative. President Jim Mullen posed the following question. “What kind of an education do we need to offer our students to ensure they thrive in the 21st century world they will encounter upon graduation from Allegheny?” To that end, the development of The Allegheny Gateway can be considered the signature new initiative coming out of the current strategic planning process as a response to this question. Building on the success of ACCEL, it brings together and integrates the issues of civic engagement, U.S. diversity, and global learning, while also emphasizing that knowledge and competence in these areas are essential for career success in the 21st century.

During the planning process for the Gateway initiative, conversations often began with someone drawing a picture of a triangle and noting the three vertices of civic engagement, U.S. diversity, and global learning. Discussion then turned to questions of why these vertices are important and how best to ensure connections among the three vertices. In fact, the College is revising the general education requirements to align with the three vertices as well as offering new interdisciplinary programs such as a major and minor in global health studies and a minor in journalism in the public interest.

Like all colleges and universities, however, Allegheny has its share of challenges and is not immune to the question of career preparation faced by LACs in particular. The Provost and Dean of the College noted a “disconnect that exists out there for LACs.” She went on to argue that she believes a liberal arts college education is the best education an individual can receive in order to succeed in the 21st century. In a world that is more diverse, more complex, and smaller that it was even 10 years ago, students must learn to approach a problem from multiple perspectives, think creatively and critically, work with people different from themselves, and communicate effectively. Allegheny tackles this disconnect by making greater connections to experiential learning and practical application of classroom theory as well as through applied liberal learning, recognizing that learning inside and outside of the classroom are equally important.

The notion of “vocationalism” was apparent during our interviews at Allegheny and is a challenge the College is facing, that is, the need to meet the professional interests of students and parents alike while still maintaining a liberal arts core. One faculty member described this as an “inevitable reality of the times,” while another described this movement as “the typical evolution that occurs in higher education.” To address the vocational interests of students, in 2009 the College began placing more emphasis on skill development and experiential learning opportunities through the newly established office of ACCEL, as well as developing a brand that spoke to students and their parents by providing depth in two, rather than just one, possible career tracks.

Allegheny has managed to keep its liberal arts roots strongly intact. The Gateway vertices of civic engagement, domestic diversity, and internationalization and the common thread of interdisciplinarity are very much rooted in a strong liberal arts core. However, the challenges the college faces are not unlike those experienced by Albion or Kenyon Colleges.

Kenyon College (experienced no change in terms of professional degrees awarded)

Kenyon College, located in the village of Gambier, Ohio, could be a movie set portraying the idyllic undergraduate institution. Dating back to 1824, it is the oldest private college in Ohio. With a beautiful physical plant, including many new and renovated buildings, record high applications for admission, and four decades of balanced budgets, Kenyon is a clear example of a successful liberal arts college. While individuals external to the College may say that little to no change has occurred at the College, those internal to Kenyon argue that their ability to keep moving forward and to remain consistent and focused is a testament to their notion of community.

The college is built around “Middle Path,” a narrow, unpaved walkway, extending from one end of campus to the other. The Kenyon website describes Middle Path as “a metaphor…embodying the ideal of community.” Ceremonies such as opening convocation and graduation take place on Middle Path; and students, faculty members, and village residents greet each other along the path daily. Cell phone use on Middle Path, for example, was highly frowned upon, demonstrating the important role this walkway plays in the life of the college. However, given the ever changing technology (and improved network coverage at the College) more cell phones are now seen on Middle Path.

Kenyon’s mission, as described by both faculty and administrators during our interviews, is to be “an outstanding liberal arts college,” or “the quintessential liberal arts college” providing education in the traditional liberal arts disciplines. Kenyon offers no professional education programs. As one professor noted, “There is a lot of resistance at Kenyon to applied, technical education…We don’t consider dumping the classics.” Another professor observed, “We don’t pursue fads.” Likewise, a senior administrator commented, “We have no drifters here,” meaning that the whole Kenyon community is committed to its traditional liberal arts mission.

A key hallmark of Kenyon is tradition, and it permeates every aspect of the institution. A social science professor acknowledged that “Kenyon has always been a conservative place. It doesn’t jump on the bandwagon.” The Vice President for Finance reported that there has been “no fundamental change” to Kenyon’s basic program. However, Kenyon’s current Provost, Joseph Klesner, noted that, although the College has not experienced dramatic change, important changes have occurred and continue to occur. This deliberateness and thoughtfulness is a testament to a strong reputation and belief in the quality of education the College provides to students. For example, the College added a quantitative reasoning requirement as well as a language proficiency requirement to the core requirements. Also, many interdisciplinary programs have been developed in areas such as International Studies, Women’s and Gender Studies, and Asian Studies.

The high level of consensus on Kenyon’s mission and form of education is quite remarkable. As one professor observed, “Everyone seems to understand the mission.” Administrators as well as faculty members express many of the same ideas and use similar phrases (e.g., traditional liberal arts mission, faculty interests drive curriculum change, tension between innovation and tradition) when discussing the college’s mission, curricula, and challenges. Key challenges mentioned include staying true to the college’s historic mission, incorporating interdisciplinary subjects into a traditional discipline-based curriculum, and effectively communicating the value of the education that Kenyon offers. Kenyon’s former President, S. Georgia Nugent, described one challenge as “evolutionary change, not revolutionary change,” which aligns with their tradition and focus on moving forward as an institution while remaining true to the liberal arts. Kenyon’s current President, Sean M. Decatur, took office in 2013. He sees the power and potential of a Kenyon education. Echoing Former President Nugent’s sentiments, he noted:

We must work together to clearly articulate the value and power of a Kenyon education. We must assert clearly why this education matters, what impact it has not only on the lives of our students and graduates but also on the world that they transform.

In spite of the challenge of sustaining a traditional liberal arts college in a time of limited resources and rapid educational change, Kenyon has resisted temptations to compromise. In fact, during our initial visit in 2009, members of the College community noted a widespread aversion to the notion of strategic planning. One professor exclaimed, “Strategic planning is a dirty word”, while former President Nugent explained, “I’m allergic to strategic planning.” However, in 2013 strategic planning was one of the charges articulated by President Decatur. He plans to embark on such a process with a guiding focus on what the College, and its graduates, will need to be successful in the year 2020.

Change at Kenyon College is not a reaction to competitive forces or uncertainty about the future. For example, a former senior academic administrator stated that the college has not changed or added programs to enhance recruitment. Similarly, former President Nugent stated that Kenyon does not balance its liberal arts mission with students’ vocational interests. As a “quintessential liberal arts college,” Kenyon has successfully resisted pressures to add professional fields to its arts and sciences-based curriculum.

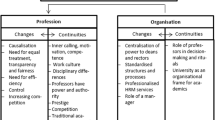

Returning to the common change language Kezar (2001) provided, we summarize the change factors for each institution in Table 1 for comparative purposes. As evidenced in the table, both Albion and Allegheny were more susceptible to external factors, which influenced the types of changes each institution implemented. However, all three institutions engaged in both first and second order changes with Allegheny and Kenyon being more proactive in their response. Finally, the change initiatives of all three institutions resulted in new programs (either organizationally or individually driven) that were substantial in nature.

Analysis

Evolutionary models of change focus on the notion of a system or the interdependence and interrelatedness of structures. Changes to one aspect of the structure result in changes or implications for other structures within the system. The concept of interactivity is foundational to the systems approach in that it describes the connected nature of activities within organizations. Albion, Allegheny, and Kenyon all engaged in institutional changes that affected other organizational aspects or structures. Albion’s change initiative focused on relationships both internal and external to the College as a result of the 2008 recession (external influences). Allegheny’s two most recent strategic planning initiatives were in response to students’ and parents’ need for greater emphasis on career development and the need for clearer branding/messaging (external influences). Finally, Kenyon was the only institution of the three to be guided primarily by internal factors (e.g., mission and values, faculty interests) prompting change at both the individual and organizational levels that resulted in modifications to the core requirements and the creation of interdisciplinary programs based on faculty interest.

Openness, as described by Kezar (2001), “…tends to characterize change as highly dependent on the external environment. Open systems exhibit an interdependence between internal and external environments” (p 29). Both Albion and Allegheny sought to bring together internal and external environments either by way of strategic partnerships as was the case for Albion (e.g., international institutional partnerships) or through a focus on global learning as addressed in one of the vertices at Allegheny. While Kenyon, too, focused on global and international experiences, they were less overt about such initiatives. Rather, their focus of change efforts was on the interdependence of internal structures of the College, reflecting their lack of interest in succumbing to “fads.”

Homeostasis, or equilibrium between the system and the environment, was the goal for all three institutions. We would argue that Kenyon has been the most successful in achieving this goal given the record of balanced budgets, the lack of outside influence on programming, and faculty driven development of new majors which we believe is a result of Kenyon’s national reputation. Kenyon will, however, engage explicitly in strategic planning for the first time in its history as per the request of the Board of Trustees; and time will only tell what role, if any, external influences will play in strategic planning at Kenyon. We would argue that Allegheny is gaining a greater national reputation among LACs as a result of its ability to honor its commitment to reward the faculty and staff with raises as well as manage enrollments and new construction despite the recession. We believe that this is a testament to the College’s commitment to strategic planning and its ability to manage internal and external factors. Despite its national ranking, Albion College faced the most challenges given its regional recruitment base. From 2008 to present, the College has faced leadership challenges at the executive level because of significant turnover, which exacerbated the challenges resulting from the recession.

Lastly, we discuss the notion of evolution. We would argue that the changes noted among the three institutional case studies are examples of evolutionary rather than revolutionary change. Each of these institutions would still be classified as a Liberal Arts I institution as per Breneman’s (1990) original definition, thus remaining true to the traditional liberal arts. Kenyon is the most traditional of the three in terms of academic focus with the decision not to offer any “pre-professional” programming. Both Albion and Allegheny Colleges offer “pre-professional” programming; however, they still confer the majority of their majors/degrees in the traditional arts and sciences.

Discussion & Future Research Directions

Our goal in this study was to build upon our prior research (Baker et al., 2012) in an effort to understand the evolutionary change that is underway in an important sector of higher education - liberal arts colleges. We relied on the evolutionary model of change to help guide our analysis and discussion of this research. We return to our original research questions to help frame our discussion as well as implications for practice and future research directions.

How and why do LAC’s change?

Given that all LAC’s essentially operate in the same macro environment, we conclude that achieving homeostasis is an important foundational step towards institutional survival. All three institutions featured in this research responded to external (and internal) stimuli in different ways, yet each of those responses represented an effort to achieve homeostasis or equilibrium. Both representatives of Albion and Allegheny Colleges spoke about the need to embody their brand more concretely and discussed the need to communicate their mission more clearly both internally and externally. Kenyon appears to have a strong handle on its mission and brand and has been successful at cornering a segment of the market and attracting a specific type of student. In each of these cases, the colleges are making key adjustments to achieve a viable balance among the varied forces and factors that shape what they are and what they will become.

Evidence suggests that LAC’s change existing programs and create new ones in an effort to respond to the challenges they are facing. More research is needed that examines institutions in each of the three trends we identified in our prior work (and noted earlier) to understand more fully why some institutions make significant changes while others appear just to fine tune their programs and public image. Evolutionary theory suggests that institutions are changing in an effort to achieve homeostasis or self-regulation. We believe that when homeostasis cannot be achieved through first-order or evolutionary changes, for example, institutions seek to make second-order changes that may be more revolutionary. This is the case with the many instances of mission creep in higher education at present.

We need to develop a clearer understanding of what factors trigger and direct change processes in LACs. Likewise, we need research that examines the success and long-term impact of the types of change (e.g., first and second order; motivated by external versus internal factors) we have discussed. Over time it would also be illuminating to study how institutions that followed these different paths are faring? What is the evidence that they have succeeded or failed? Do some approaches to institutional change appear to be more effective than others?

What makes LACs susceptible to change?

Given our reliance on the evolutionary model of change, we focus mostly on the role of external influences to provide important insights into issues of susceptibility. As noted earlier, Albion College is located in the state of Michigan and currently recruits 80 to 90% of its students from within the state. Given the economic issues and the challenges faced recently by the Michigan auto industry, Albion must be more responsive to the needs of its market (students and parents in the state of Michigan). In contrast, Kenyon College in the economically challenged state of Ohio has developed national visibility and a national student market. Furthermore, the Kenyon community has the clearest sense of who they are and what they do (and do not do), which is guided more directly by internal than external factors. The wider visibility and more geographically dispersed clientele have protected Kenyon from regional downturns much like a diversified portfolio protects an investor from problems occurring in a specific company or industry. Hence, Kenyon’s changes have been considerably more modest that Albion’s. We would argue that Allegheny’s experience is somewhere in the middle of this continuum (e.g., regional recruiting base versus national recruiting base). Allegheny’s change efforts have largely been guided by successful strategic initiatives which have been influenced by external factors. Allegheny is not immune to market forces but has been able to weather them more effectively given the foundation of strategic planning.

What are the outcomes of change in LACs?

Relying on Kezar’s (2001) notion of first and second order change, we illustrate how all three institutions engaged in change efforts that affected peripheral and central programming. Albion sought to address external influences by way of partnerships that touched upon the academic, operational, and communal areas the College. Allegheny chose to focus on progressive and complementary change efforts which built upon the prior strategic initiatives of the College. Finally, Kenyon focused on internal factors including the values and the mission of the College to guide curricular changes and developments.

We argue that one contributing factor for the evolution we see underway in liberal arts colleges as a sector is the increase in second order changes as institutions seek to achieve homeostasis. When homeostasis cannot be achieved, more second order changes occur resulting in what Morphew (2009) described as academic drift thus causing the decline in the numbers of liberal arts colleges that meet Breneman’s (1990) definition. Future research should continue to explore the evolution underway among LACs and identify the types of first and second order changes that are occurring and should explore the factors that influence change.

Conclusion

Liberal arts colleges have had an influential role in the history of U.S. higher education. For quite some time, a competitive market, students’ growing vocational orientation, and precarious finances have been eroding the clear purpose of many liberal arts colleges (Neely, 1999). The changes that we examined are part of a much larger phenomenon that is underway to various degrees throughout higher education. Our effort to study change in one specific institutional sector (liberal arts colleges) can shed light on change in postsecondary education institutions more broadly. We believe the evolutionary change model and the questions we asked in this study are a useful starting point for this line of research. Such a theory helps to clarify the diverse factors contributing to change and the potential consequences of modest (first-order) and dramatic (second-order) changes. We also believe it can help to illuminate the varied forces that pressure institutions to adapt and enable academic leaders and their institutions to keep these forces balanced (e.g., maintain institutional equilibrium). Likewise the model helps to emphasize the benefits of protecting core institutional values and traditions while simultaneously adapting to the changing environment of higher education.

Notes

Names of persons interviewed are used with permission.

References

Association of American Colleges & Universities. (2011). The LEAP vision for learning: Outcomes, practices, impact, and employers’ views. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Baker, V. L., Baldwin, R. G., & Makker, S. (2012). Where are they now? Revisiting Breneman’s study of liberal arts colleges. Liberal Education, 98(3), 48–53.

Breneman, D. W. (1990). Are we losing our liberal arts colleges? AAHE Bulletin, 43(2), 3–6.

Brint, S., Riddle, M., Turk-Bicakci, L., & Levy, C. S. (2005). From the liberal to the practical arts in American colleges and universities: Organizational analysis and curricular change. Journal of Higher Education, 76, 151–180.

Cameron, K. S. (1991). Organizational adaptation and higher education. In M. W. Peterson, E. E. Chaffee, & T. H. White (Eds.), ASHE Reader on Organizations and Governance in Higher Education (4th ed.). Heights, MA: Ginn Press.

Creswell, J. (2009). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Incorporated.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 4, 532–550.

Freeland, R. M. (2009). Liberal education and the necessary revolution in undergraduate education. Liberal Education, 95, 6–13.

Gumport, P. J. (2000). Academic restructuring: Organizational change and institutional imperatives. Higher Education, 39, 67–91.

Hartley, M. (2003). “There is no way without a because”: Revitalization of purpose at three liberal arts colleges. The Review of Higher Education, 27, 75–102.

Hartley, M., & Schall, L. (2005). The endless good argument: The adaptation of mission at two liberal arts colleges. GSE Publications, 17, 5–11.

Hearn, J. C. (1996). Transforming US higher education: An organizational perspective. Innovative Higher Education, 21, 141–154.

Humphreys, D., & Kelly, P. (2014). How liberal arts and sciences majors fare in employment: A report on earnings and long-term career paths. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Kena, G., Aud, S., Johnson, F., Wang, X., Zhang, J., Rathbun, A., Wilkinson-Flicker, S., & Kristapovich, P. (2014). The condition of education 2014 (NCES 2014-083). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Kezar, A. J. (2001). Understanding and facilitating organizational change in the 21st century: Recent research and conceptualizations: ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, 28(4), 4. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Lang, E. M. (1999). Distinctively American: The liberal arts college. Daedalus, 128, 133–150.

Loomis, S., & Rodriguez, J. (2009). Institutional change in higher education. Higher Education, 58, 475–498.

Martin, W. B. (1984) Adaptation and Distinctiveness. The Journal of Higher Education, 55(2), 286–296.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). An expanded sourcebook: Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Morphew, C. C. (2009). Conceptualizing change in the institutional diversity of US colleges and universities. The Journal of Higher Education, 80, 243–269.

Morphew, C. C. (2002). “A rose by any other name”: Which colleges became universities. The Review of Higher Education, 25, 207–223.

Neely, P. (1999). The treats to liberal arts colleges. Daedalus, 128, 27–46.

Pope, L. (2013). Colleges that change lives: 40 schools that will make you change the way you think about college (4th edn), H. M. Oswald (Ed.). London, England: Penguin Books.

Rodgers, J. L., & Jackson, M. W. (2012). Are we who we think we are: Evaluating brand promise at a liberal-arts institution. Innovative Higher Education, 37, 153–166.

Stark, J., & Lowther, M. (1988). Strengthening the ties that bind: Integrating undergraduate liberal and professional study. Report of the Professional Preparation Network. Ann Arbor, MI: The Regents of the University of Michigan.

Yin, R. K. (2008). Case study research: Design and methods (applied social research methods). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Melissa McDaniels and David Tritelli for their support and helpful comments during the writing of this manuscript. This research was supported by a grant from the Hewlett-Mellon Fund for Faculty Development at Albion College in Albion, Michigan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baker, V.L., Baldwin, R.G. A Case Study of Liberal Arts Colleges in the 21st Century: Understanding Organizational Change and Evolution in Higher Education. Innov High Educ 40, 247–261 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-014-9311-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-014-9311-6