Abstract

The healthcare sector was one of the few sectors of the US economy that created new positions in spite of the recent economic downturn. Economic contractions are associated with worsening morbidity and mortality, declining private health insurance coverage, and budgetary pressure on public health programs. This study examines the causes of healthcare employment growth and workforce composition in the US and evaluates the labor market’s impact on healthcare spending and health outcomes. Data are collected for 50 states and the District of Columbia from 1999–2009. Labor market and healthcare workforce data are obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Mortality and health status data are collected from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vital Statistics program and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Healthcare spending data are derived from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Dynamic panel data regression models, with instrumental variables, are used to examine the effect of the labor market on healthcare spending, morbidity, and mortality. Regression analysis is also performed to model the effects of healthcare spending on the healthcare workforce composition. All statistical tests are based on a two-sided \(\alpha \) significance of \(p\,<\) .05. Analyses are performed with STATA and SAS. The labor force participation rate shows a more robust effect on healthcare spending, morbidity, and mortality than the unemployment rate. Study results also show that declining labor force participation negatively impacts overall health status (\(p\,<\) .01), and mortality for males (\(p\,<\) .05) and females (\(p\,<\) .001), aged 16–64. Further, the Medicaid and Medicare spending share increases as labor force participation declines (\(p\,<\) .001); whereas, the private healthcare spending share decreases (\(p\,<\) .001). Public and private healthcare spending also has a differing effect on healthcare occupational employment per 100,000 people. Private healthcare spending positively impacts primary care physician employment (\(p\,<\) .001); whereas, Medicare spending drives up employment of physician assistants, registered nurses, and personal care attendants (\(p\,<\) .001). Medicaid and Medicare spending has a negative effect on surgeon employment (\(p\,<\) .05); the effect of private healthcare spending is positive but not statistically significant. Labor force participation, as opposed to unemployment, is a better proxy for measuring the effect of the economic environment on healthcare spending and health outcomes. Further, during economic contractions, Medicaid and Medicare’s share of overall healthcare spending increases with meaningful effects on the configuration of state healthcare workforces and subsequently, provision of care for populations at-risk for worsening morbidity and mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The labor market, health outcomes, and health insurance

As unemployment increases, affected individuals might confront an increased risk for developing or aggravating mental and physical health problems (Catalano 2009; Idler and Benyamini 1997; Jin et al. 1995; Roelfs et al. 2011). There is conflicting evidence concerning the relationship between unemployment, health status, and all-cause mortality. Studies show a countercyclical relationship between economic conditions, health status, and death rates (Brenner and Mooney 1983; Browning and Moller Dano 2006; Catalano 1991; Catalano et al. 2011; Dooley et al. 1996; Franks et al. 2003; Frey 1982; Kasl et al. 1975; Moser et al. 1987; Neumayer 2004; Tapia Granados 2005). Some studies show that unemployment duration impacts health most (Garcy and Vågerö 2012; Janlert 1997; Wadsworth et al. 1999); other studies evidence that individuals may be selected into unemployment as a result of declining health status (Bockerman and Ilmakunnas 2009).

Studies also evidence morbidity and mortality are pro-cyclical, increasing during periods of economic growth (Gerdtham and Ruhm 2006; Gerdtham and Johannesson 2003; Ruhm 2000, 2003, 2005). This relationship is more detrimental for educated, working age males when compared to the general population (Edwards 2008). During economic expansions, individuals may engage in fewer positive health behaviors, such as preventative healthcare utilization, maintaining a healthy diet, and regular physical activity, due to increased opportunity costs (Ruhm 2000). Self-reported health is a strong and independent predicator of morbidity and mortality (Connelly et al. 1989; Idler and Benyamini 1997; McCallum et al. 1994).

Health insurance in the United States (US) is predominantly employment-based. As the economy deteriorates, unemployed individuals may lose their private insurance coverage and experience an increased risk of developing or aggravating adverse health conditions. Previous research identifies a pro-cyclical relationship between employment and employer-provided health insurance coverage; tighter labor markets negatively impact employers’ decisions to provide health insurance (Marquis and Long 2001); in addition, economic expansions are also associated with higher quality private health insurance schemes (Marquis and Long 2001).

Unemployed and uninsured individuals may become eligible for publicly funded health insurance schemes, including poverty and asset tested Medicaid coverage, and age or disability tested Medicare coverage. Medicaid is a state administered program, jointly funded by the Federal government through income taxes. Covered services are for individuals who meet means and asset-based testing criteria, including Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2013a). Medicare is a Federal administered program funded through payroll taxes. Covered services are for individuals aged 65 and older, or for those who have qualifying disabilities, including end-stage renal disease (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2013b). Studies show a countercyclical relationship between Medicaid coverage and unemployment (Cawley and Simon 2005; Perreira 2006).

Health insurance and healthcare workforce composition

In the US, health insurance is associated with high healthcare utilization and spending. In the 1950s through 1990s period, fifty percent of the increase in per-capita healthcare spending in the US is related with expanded health insurance. Medicare provisions have a large effect on hospital services growth (Finkelstein 2007); whereas, expanded state Medicaid coverage increases access to outpatient and hospital services and pharmaceuticals (Finkelstein et al. 2012). Likewise, healthcare provider supply is associated with reimbursement fees and risk pooling opportunities (Newhouse 1996). Medicaid provisions are associated with increased employment of mid-level mental health professionals (Pellegrini and Rodriguez-Monguio 2013). However, no research has examined the effect of healthcare spending on the configuration of the US healthcare industry.

Conceptual framework and objectives

Previous research uses the unemployment rate to evaluate the relationship between labor market conditions and health outcomes. An alternative approach is to use the labor force participation rate to proxy the economic environment. The labor force participation rate captures two segments of the population potentially at risk for worsening health status and increased risk of mortality: long-term unemployed who have withdrawn efforts to search actively for work, and other non-participating members of the labor force potentially reliant on public health insurance programs. This study utilizes both labor market related measures to evaluate the impact of economic conditions on morbidity and mortality. Study hypotheses are: (1) the labor force participation rate is a better predictor of health outcomes than the unemployment rate, and (2) the labor force participation rate is related with the share of health insurance payer sources (i.e., Medicare, Medicaid, and private health insurance) funding provision of care. Furthermore, the conceptual model also illustrates health insurance payers’ impact on the healthcare workforce.

Hence, study objectives are to assess whether the labor market affects healthcare spending and health outcomes, and to examine the effect of healthcare spending on the healthcare workforce composition (Fig. 1).

Data

Annual, state level data are collected for all states and the District of Columbia for the period 1999–2009. Unemployment and labor force participation rates are obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Local Area Unemployment Statistics (LAUS) survey (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2013b). The unemployment rate reflects the percentage of the labor force that is unemployed and looking for a job. The labor force participation rate reflects the percentage of working age individuals (aged 16–64) who are either employed or unemployed, and looking for a job.

Adult all-cause mortality rates and self-reported health status data are obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vital Statistics program and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, respectively (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013b, a). Adult all-cause mortality rates are for the population aged 16–64. This group aligns with the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ examined age group for its labor force measures (aged 16 and older), while considering eligibility for Medicare (aged 65 and older). Self-reported health status, a measure of personal well-being, is broken down into five groups: excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor.

Medicaid, Medicare, and overall healthcare expenditures data are derived from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMMS) Medicaid Statistical Information System (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2013c).The difference between Medicaid and Medicare expenditures and overall healthcare expenditures serves as a proxy for private sector healthcare expenditures. Medicaid, Medicare, and the private sector’s share of state healthcare expenditures equals the ratio between Medicaid, Medicare, and private sector healthcare spending and overall state healthcare expenditures.

Healthcare workforce (i.e. occupational employment and average hourly wage) data are obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Employment Statistics program. Occupations and their corresponding 2011 average hourly rates included in the analysis are; (1) primary care physicians ($85.26) (i.e. family and general practitioners), (2) general internists ($90.97), (3) surgeons ($111.32), (4) physician assistants ($43.01), (5) registered nurses ($33.23), (6) personal care attendants ($9.88), (7) occupational therapists ($36.05), (8) physical therapists ($38.38), (9) physical therapy assistants ($24.57), (10) respiratory therapists ($27.05), (11) pharmacists ($53.92), and (12) pharmacy technicians ($14.43) (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2013c). Healthcare occupational employment data are converted to rates per 100,000 people. Population data are obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Bridged Race Population Statistics program (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013c).

Methods

This study seeks to isolate two pathways: (1) effect of labor market conditions on healthcare spending and health outcomes; and (2) effect of healthcare spending on occupational employment per 100,000 people. Dynamic panel data analysis is used to model relationships between the labor market (i.e. unemployment and labor force participation) and health outcomes (i.e. self-reported health status, and all-cause mortality rates for males and females, aged 16–64), and healthcare spending (i.e. Medicaid, Medicare, and private sector share of state healthcare spending).

where \(\hbox {Y}_\mathrm{it}\) represents either the mortality rate, health status, or healthcare spending, \(\hbox {X}_\mathrm{it}\) represents labor market indicators, \(\upalpha _\mathrm{i}\) is the cross-sectional fixed effect, and \(\upmu _\mathrm{it}\) represents the error term.

Analysis is also performed to model the effect of healthcare spending, \(\hbox {Y}_\mathrm{it}\), on occupational employment per 100,000 people. For these models, \(\hbox {Y}_{\mathrm{it}}\) represents healthcare occupational employment per 100,000 people, \(\hbox {X}_\mathrm{it}\) represents healthcare spending, \(\upalpha _\mathrm{i}\) is the cross-sectional fixed effect, and \(\upmu _\mathrm{it}\) represents the error term.

Four instrumental variables are included in the analysis to isolate variation that is plausibly exogenous: (1) State Unemployment Insurance (SUI) recipiency rate, (2) SUI average annual benefit (3) food stamp expenditures (i.e. Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program-SNAP), (4) Social Security expenditures, and (5) average disposable income. The SUI recipiency rate represents the percentage of each state’s unemployed receiving cash assistance. The SUI average annual benefit is the average annualized payment received per beneficiary enrolled in the program. SUI data are obtained from the Employment and Training Administration through the US Department of Labor (2013). Food stamp and Social Security expenditures and average disposable income data are obtained from the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ US economic accounts (2013). Monetary values (i.e. expenditures and income data) are converted to 2011 dollars using the consumer price index for all urban consumers (CPI-U) as obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2013a). Count data are converted to per-capita rates.

The labor market and healthcare spending models include the SUI recipiency rate and SUI average annual payment as instrumental variables for unemployment and labor force participation, respectively. Unemployment is the enrollment criteria for the SUI program (SUI recipiency rate), whereas labor force participation is related with the program’s funding mechanisms (SUI average annual benefit). However, both health status and healthcare spending are independent of SUI coverage. Further, per-capita food stamp expenditures serve as the instrumental variable for Medicaid spending; poverty is the enrollment criteria for both programs. Likewise, per-capita Social Security and Medicare spending are related through age and/or disability testing criteria. Last, average state disposable income serves as the instrumental variable for private healthcare spending; higher income levels are correlated with increasing private insurance coverage, and vice versa. However, food stamp and Social Security expenditures, and average disposable income do not impact healthcare occupational employment. Main sources of payment for healthcare professionals’ fees are third party payers (Medicaid, Medicare, and private sources). All p values of statistical tests are two-sided and are considered statistically significant if \(<\).05. Analyses are performed with STATA and SAS.

Results

Descriptive statistics

During the study period, the average unemployment rate for 50 states and DC was 5.1 %; increasing from 4.1 % in 1999 to 8.5 % in 2009. The study period average labor force participation rate was 67.2 %; declining from 68.0 % in 1999 to 66.2 % in 2009 (Table 1). The overall health status worsened and the mortality rate increased. The average percentage of individuals reporting their health status as excellent declined by 8.9 % over the study period, while more individuals reported fair (6.3 % increase) or poor (8.4 % increase) health. In 1999, the all-cause mortality rate for males and females, aged 16–64, was 228.9 and 391.8, respectively, increasing to 245.6 and 408.9 in 2009, respectively.

Public health insurance programs increased their share of average state healthcare spending. In 1999, the average Medicaid, Medicare, and private sector share of state healthcare spending was 14.8, 17.7, and 67.6 %, respectively. By 2009, Medicaid and Medicare increased their share of average state healthcare spending by 8.0 and 20.3 %, respectively, while the private sector share decreased by 7.1 % (Table 1).

There were also changes in healthcare workforce employment in the study period. For example, state average employment of primary care physicians, internists, and surgeons per 100,000 people declined by 16.8, 12.9, and 12.4 %, respectively. To the contrary, employment of physician assistants per 100,000 people increased by 32.7 %. Further, in 1999, there were an average of 83.5 pharmacists and 72.1 pharmacy technicians per 100,000 people. In 2009, pharmacy technician employment was greater than that of pharmacists; pharmacy technicians’ employment growth exceeded that of pharmacists by 500 %.

Effect of labor market conditions on healthcare spending and health outcomes

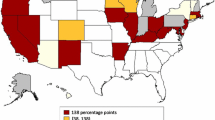

Scatter plots show a linear relationship between the labor force participation rate and healthcare spending and health outcomes. As labor force participation increases, health status worsens and the mortality rate increases for males and females, aged 16–64. Further, as labor force participation increases, Medicaid and Medicare’s share of state healthcare spending declines while private healthcare spending increases (Fig. 2).

Labor force participation, health outcomes, and healthcare spending, United States, 1999–2009. Source: Labor force data derived from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Local Area Unemployment Statistics survey. Mortality and health status data derived from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vital Statistics and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Systems, respectively. Healthcare spending data derived from the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services

Unemployment, healthcare spending, and health status measures exhibit similar relationships. Nevertheless, unemployment associations display greater variation when compared to the labor force participation rate (Fig. 3).

Unemployment, health outcomes, and healthcare spending, United States, 1999–2009. Source: Labor force data derived from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Local Area Unemployment Statistics survey. Mortality and health status data derived from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vital Statistics and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Systems, respectively. Healthcare spending data derived from the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services

Study results show that states experiencing declines in labor force participation had lower overall self-reported health status and increased risk of death for both males and females aged 16–64 years old. A one percentage point increase in the labor force participation rate is associated with an 8.1 (\(p <\).001) and 5.6 percent (\(p <\).05) decrease in the female and male mortality rates, respectively. Further, a one percentage point increase in the labor force participation rate is associated with a .55 % increase in the percentage of the population rating their health as excellent (\(p <\).001). Increasing labor force participation is also associated with a decreasing percentage of the population rating their health as good or fair (\(p <\).01) (Table 2). Similar to the labor force participation rate, unemployment is also associated with increased mortality rates for males and females aged 16-64 years old (\(p <\).01) and deteriorating self-reported health status, although not statistically significant.

As the state labor force participation rate increases, Medicaid and Medicare spending (\(p <\).001) as a share of total state healthcare spending decreases, and the private healthcare spending share increases (\(p <\).001). A one percentage point increase in the labor force participation rate is associated with a 1.1 and .61 (\(p <\).001) percent decrease in Medicaid and Medicare’s share of total state healthcare spending, respectively, and a 1.7 % (\(p <\).001) increase in the private healthcare spending share. As expected, unemployment exhibits a similar effect on state healthcare spending share when compared to labor force participation.

Effect of healthcare spending on the healthcare workforce

Study results show that Medicaid, Medicare, and private healthcare spending have differing effects on healthcare occupational employment. As Medicaid and Medicare’s share of total healthcare spending increases, surgeon employment decreases (\(p <\).05). To the contrary, as the share of private sector spending increases, primary care physician employment increases (\(p <\).001); the effect on surgeon employment is also positive, but not statistically significant (Table 3).

Both Medicaid and Medicare have a statistically significant and positive effect on employment of mid-level providers. As the share of Medicare spending increases, employment of physician assistants also increases (\(p <\).001). Further, increasing public health program spending share leads to increases in employment of registered nurses (\(p <\).001), personal care attendants (\(p <\).001), occupational therapists (\(p <\).05), physical therapists (\(p <\).001) and assistants (\(p <\).05), respiratory therapists (\(p <\).001), and pharmacy techs (\(p <\).001). To the contrary, an increase in the private healthcare spending share is negatively related with employment for these providers. Medicare spending drives up pharmacist employment (\(p <\).001); whereas Medicaid and private healthcare spending has the opposite effect (Table 3).

Discussion

This study adds to the literature by estimating a dynamic panel data model to examine the relationship between the labor market and healthcare spending and health outcomes, and to provide empirical evidence of the effect of healthcare spending on occupational employment.

This study provides further empirical evidence of the countercyclical relationship between economic conditions, health status, and all-cause mortality; health status worsens and mortality rates increase during economic downturns (Brenner and Mooney 1983; Browning and Moller Dano 2006; Catalano 1991; Catalano et al. 2011; Dooley et al. 1996; Franks et al. 2003; Frey 1982; Kasl et al. 1975; Moser et al. 1987; Neumayer 2004; Tapia Granados 2005).

Most previous research uses the unemployment rate to evaluate associations between economic recessions and health (Catalano 2009; Idler and Benyamini 1997; Jin et al. 1995; Roelfs et al. 2011). This study employs both unemployment and labor force participation measures to proxy economic conditions. Study results provide empirical evidence of more robust associations between the labor force participation rate and measures of well-being and mortality and healthcare spending compared to unemployment. During periods of recession, long-term unemployed may become discouraged and ultimately withdraw efforts to search actively for work. As a result, such individuals are no longer considered unemployed nor are they part of the participating labor force. Long-term unemployed often lack access to healthcare increasing risk for health status depreciation and premature death. This may occur through less access to employment-based health insurance or an inability to afford consumer-driven private insurance schemes. Furthermore, the non-participating component of the labor force participation rate reveals the level of each state’s population potentially reliant on employed individuals to support their care as paid for through taxes (i.e. public health insurance programs).

This study shows that, during economic downturns, public payer sources comprise an increasingly larger component of the multi-payer insurance system; as labor force participation declines, the share of public healthcare spending increases, and the private healthcare spending share decreases. There are several challenges associated with the provision of Medicaid and Medicare coverage during periods of economic contraction. As the state labor force participation rate decreases, income tax revenue to support state Medicaid programs comes under pressure during times when more individuals qualify for coverage. Further, state benefit cuts to Medicaid programs may result in a loss of Federal matching funds (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013a) potentially further constraining healthcare provisions.

This study finds that, during economic contractions, characterized by increased unemployment/decreased labor force participation, individuals experience worsening self-reported health status and increased risk of mortality. At the same time, the Medicaid safety net significantly weakens for most financially and clinically vulnerable population groups potentially jeopardizing access to cost-effective prevention services, and healthcare promotion, and indirectly inducing costly utilization of emergency care as a primary source of care. Furthermore, as the nationwide labor force participation rate declines, payroll tax revenue to support the Medicare program funding decreases. Similar to Medicaid, during economic contractions, Medicare is also challenged with the demands of providing services for increasing numbers of disabled enrollees and retirees with strained revenue sources.

Public health programs shape the composition of the US healthcare workforce as a main source of payment for professionals and services. Novel study findings relate to the effects of public and private healthcare spending on occupational employment. Public healthcare spending is associated with employment growth for registered nurses, personal care attendants, physical therapists and assistants and occupational and recreational therapists. Medicare spending, in particular, is linked to physician assistants employment; whereas, private healthcare spending is positively associated with primary care physician employment. Differing impacts on the healthcare workforce relate with underlying reimbursement rates differences between public and private systems. Thus, financing mechanisms lead to recruitment of mid-level, lower cost healthcare professionals for publicly funded provision of services. Literature shows that reduced access to healthcare services, in general, and primary care, in particular, negatively affects health outcomes (Fihn and Wicher 1988; Fisher 2003; Starfield et al. 2005).

Last, Medicare Part D program enacted as part of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, which went into effect on January 1, 2006, likely affects pharmacist and pharmacy technician employment. In addition to differences in pharmaceutical coverage and state reimbursement rates between both public health programs, the Medicaid pharmaceutical spending share for dual eligible population (i.e. Medicaid-Medicare patients) shifted towards the Medicare Part D program.

Limitations

Some limitations must be taken into account in the interpretation of study results. First, our proxy variable for healthcare spending does not account for Veteran Affairs (VA) related healthcare services. However, VA administration is less dependent upon labor market conditions.

Second, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) health status measure is a self-reported survey. Survey respondents are selected in accordance to CDC sampling methodologies and data are aggregated to create a statewide representative average. Response reliability may be related with age, income, or occupation (Crossley and Kennedy 2002). However, BRFSS weighting adjustments minimize the impact of differences in non-coverage, under-coverage, and non-response at the state level.

Third, regression models may be subject to reverse causality. Attainment of public health insurance coverage may affect an individual’s labor market participation much like public healthcare financing is dependent upon healthy labor markets (i.e. low unemployment and high labor force participation) for revenue generation. Likewise, healthcare professional services supply may influence healthcare spending, similarly as health insurance provisions shape workforce supply. Last, health may be endogenous to labor supply; health status may affect an individual’s decision to participate in the labor market much like unemployment and labor force participation may influence an individual’s health status (Bartley 1987; Berkowitz and Johnson 1974; Bockerman and Ilmakunnas 2009; Cai and Kalb 2006; Chirikos 1993). Nevertheless, the literature examining the sources of endogeneity of health is scarce (Cai 2010). Regression models may also be subject to omitted variable bias; both the labor market and health insurance expenditures’ models may be correlated with other time varying confounders that influence the mortality rate, health status, healthcare spending, and healthcare professionals’ employment. Nevertheless, causality among these relationships is ambiguous (Levy and Meltzer 2008). Instrumental variables approach is used to deal with endogeneity so that consistent estimates for the labor market effect are obtained. The validity of the study instrumental variables relies on the arguments based on economic theory. Correlation tests between the instrumental variables and the error term are not methodologically sound in the regression models performed.

Conclusion

Recessions are characterized by increased unemployment, declining labor force participation, and worsening health status. Economic contractions are additionally associated with declining private healthcare spending, and strain on the public health safety net. Labor force participation, as opposed to unemployment, is a stronger predictor of morbidity, mortality, and healthcare spending. As labor force participation declines, measures of well-being deteriorate while Medicare and Medicaid programs take a larger share of state healthcare budgets.

Public health insurance provisions have differing effects on the configuration of the healthcare workforce. In the study period, increasing Medicaid and Medicare share of state healthcare expenditures is significantly related with employment growth of mid-level providers; whereas, private healthcare spending is positively associated with employment of primary care physicians per 100,000 people. During economic contractions, Medicaid and Medicare’s share of overall state healthcare spending increases with meaningful effects on the configuration of state healthcare workforces and subsequently, provision of care for populations at-risk for worsening morbidity and mortality.

References

Bartley, M. (1987). Unemployment and health: Causation or selection—a false antithesis? Sociology of Health and Illness, 10, 41–67.

Berkowitz, M., & Johnson, W. G. (1974). Health and labor force participation. Journal of Human Resources, 9, 117–128.

Bockerman, P., & Ilmakunnas, P. (2009). Unemployment and self-assessed health: Evidence from panel data. Health Economics, 18(2), 161–179.

Brenner, M. H., & Mooney, A. (1983). Unemployment and health in the context of economic change. Social Science and Medicine, 17(16), 1125–1138.

Browning, M., & Moller Dano, A. (2006). Job displacement and stress related health outcomes. Health Economics, 15(10), 1061–1075.

Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2013). Regional economic accounts: State annual personal income and employment. Retrieved, from http://bea.gov/regional/index.htm/

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2013a). Consumer price index. Retrieved, from http://www.bls.gov/cpi/

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2013b). Labor force statistics from the local area unemployment statistics survey. Retrieved, from http://www.bls.gov/lau/

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2013c). Occupational employment statistics. Retrieved, from http://www.bls.gov/oes/

Cai, L. (2010). The relationship between health and labour force participation: Evidence from a panel data simultaneous equation model. Labour Economics, 17(1), 77–90.

Cai, L., & Kalb, G. (2006). Health status and labour force participation: Evidence from Australia. Health Economics, 15(3), 241–261.

Catalano, R. (1991). The health effects of economic insecurity. American Journal of Public Health, 81, 1148–1152.

Catalano, R. (2009). Health, medical care, and economic crisis. New England Journal of Medicine, 360, 749–751.

Catalano, R., Goldman-Mellor, S., Saxton, K., Margerison-Zilko, C., Subbaraman, M., LeWinn, K., et al. (2011). The health effects of economic decline. Annual Review of Public Health, 32, 431–450.

Connelly, J. E., Philbric, J. T., Smith, R. G., Kaiser, D. L., & Wymer, A. (1989). Health perceptions of primary care patients and the influence on health care utilization. Medical Care, 27, S99–S109.

Cawley, J., & Simon, K. L. (2005). Health insurance coverage and the macroeconomy. Journal of Health Economics, 24(2), 299–315.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013a). The behavioral risk factor surveillance system (BRFSS). Retrieved, from http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013b). WONDER online databases. Retrieved, from http://wonder.cdc.gov/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013c). Bridged-race population estimates. Retrieved, from http://wonder.cdc.gov/bridged-race-population.html

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2013a). Medicaid. Retrieved, from http://www.medicaid.gov/

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2013b). Medicare. Retrieved, from http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare.html

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2013c). Medicaid statistical information system (MSIS). Retrieved, from http://www.medicaid.gov

Chirikos, T. N. (1993). The relationship between health and labor market status. Annual Review of Public Health, 14(1), 293–312.

Crossley, T. F., & Kennedy, S. (2002). The reliability of self-assessed health status. Journal of Health Economics, 21, 643–658.

Dooley, D., Fielding, J., & Levi, L. (1996). Health and unemployment. Annual Review of Public Health, 17, 449–465.

Edwards, R. (2008). Who is hurt by procyclical mortality? Social Science & Medicine, 67(12), 2051–2058.

Fihn, S. D., & Wicher, J. B. (1988). Withdrawing routine outpatient medical services, effects on access and health. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 3, 356–362.

Finkelstein, A. (2007). The aggregate effects of health insurance: Evidence from the introduction of Medicare. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(1), 1–37.

Finkelstein, A., Taubman, S., Wright, B., Bernstein, M., Gruber, J., Newhouse, J. P., et al. (2012). The Oregon health insurance experiment: Evidence from the first year. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(3), 1057–1106.

Fisher, E. S. (2003). Medical care—is more always better? New England Journal of Medicine, 349(17), 1665–1667.

Franks, P., Gold, M. R., & Fiscella, K. (2003). Sociodemographics, self-rated health, and mortality in the US. Social Science and Medicine, 56, 2505–2514.

Frey, J. J. (1982). Unemployment and health in the United States. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition), 284(6322), 1112–1113.

Garcy, A., & Vågerö, D. (2012). The length of unemployment predicts mortality differently in men and women, and by cause of death: A six year mortality follow-up of the Swedish 1992–1996 recession. Social Science and Medicine, 74, 1911–1920.

Gerdtham, U. G., & Johannesson, M. (2003). A note on the effect of unemployment on mortality. Journal of Health Economics, 22(3), 505–518.

Gerdtham, U. G., & Ruhm, C. J. (2006). Deaths rise in good economic times: Evidence from the OECD. Economics of Human Biology, 4, 298–316.

Idler, E. L., & Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 38, 21–37.

Janlert, U. (1997). Unemployment as a disease and diseases of the unemployed. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Environmental Health, 23(Suppl. 3), 79–83.

Jin, R. L., Shah, C. P., & Svoboda, T. J. (1995). The impact of unemployment on health: A review of the evidence. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 153(5), 529–540.

Kasl, S. V., Gore, S., & Cobb, S. (1975). The experience of losing a job: Reported changes in health, symptoms and illness behavior. Psychosomatic Medicine, 37(2), 106–122.

Levy, H., & Meltzer, D. (2008). The impact of health insurance on health. Annual Review of Public Health, 29, 399–409.

Marquis, M. S., & Long, S. H. (2001). Employer health insurance and local labor market conditions. International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics, 1(3), 273–292.

McCallum, J., Shadbolt, B., & Wang, D. (1994). Self-rated health and survival: A 7 year follow-up study of Australian elderly. American Journal of Public Health, 847, 1100–1105.

Moser, K., Goldblatt, P. O., Fox, A. J., & Jones, D. R. (1987). Unemployment and mortality. British Medical Journal, 294, 509.

Neumayer, E. (2004). Recessions lower (some) mortality rates: Evidence from Germany. Social Science and Medicine, 58, 1037–1047.

Newhouse, J. P. (1996). Reimbursing health plans and health providers: Efficiency in production versus selection. Journal of Economic Literature, 34(3), 1236–1263.

Pellegrini, L. C., & Rodriguez-Monguio, R. (2013). Unemployment, Medicaid provisions, the mental health industry, and suicide. The Social Science Journal, 50(4), 482–490.

Perreira, K. M. (2006). Crowd-in: The effect of private health insurance markets on the demand for Medicaid. Health Services Research, 41(5), 1762–1781.

Roelfs, D. J., Shor, E., Davidson, K. W., & Schwartz, J. E. (2011). Losing life and livelihood: A systematic review and meta-analysis of unemployment and all-cause mortality. Social Science and Medicine, 72, 840–854.

Ruhm, C. J. (2000). Are recessions good for your health? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(2), 617–650.

Ruhm, C. J. (2003). Good times make you sick. Journal of Health Economics, 22(3), 637–658.

Ruhm, C. J. (2005). Healthy living in hard times. Journal of Health Economics, 24, 341–363.

Starfield, B., Shi, L., & Macinko, J. (2005). Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Quarterly, 83, 457–502.

Tapia Granados, J. A. (2005). Increasing mortality during the expansions of the US economy, 1900–1996. International Journal of Epidemiology, 34, 1194–1202.

US Department of Labor: Employment and Training Administration. (2013). State Unemployment Insurance (SUI). Retrieved, from http://www.doleta.gov/

Wadsworth, M. E. J., Montgomery, S. M., & Bartley, M. J. (1999). The persisting effect of unemployment on health and social well-being in men early in working life. Social Science and Medicine, 48(10), 1491–1499.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank the editor and two referees for useful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pellegrini, L.C., Rodriguez-Monguio, R. & Qian, J. The US healthcare workforce and the labor market effect on healthcare spending and health outcomes. Int J Health Care Finance Econ 14, 127–141 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-014-9142-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-014-9142-0