Abstract

This study empirically evaluates the effectiveness of different health care cost containment measures. The measures investigated were introduced in Germany in 1997 to reduce moral hazard and public health expenditures in the market for rehabilitation care. Of the analyzed measures, doubling the daily copayments was clearly the most effective cost containment measure, resulting in a reduction in utilization of about \(20\,\%\) . Indirect measures such as allowing employers to cut federally mandated sick pay or paid vacation during inpatient post-acute care stays did not significantly reduce utilization. There is evidence neither for adverse health effects nor for substitution effects in terms of more doctor visits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For decades health expenditures have increased exponentially in most industrialized countries. In the US, real health spending per capita increased a staggering 500 % between 1970 and 2010 (in 2000 prices, OECD 2012). In Germany, real health spending per capita increased by 350 % over the same time period, consuming 11.6 % of GDP in 2010 (German Federal Statistical Office 2013). In light of these figures, it is not surprising that rising health care expenditures are one of the most contentious issues and a matter of great concern for policy makers around the world (cf. Spithoven 2009; Stoltzfus 2012).

In the demand-side research, cost-sharing is identified as one main tool to reduce moral hazard and overconsumption of medical services (Pauly 1968; Pauly and Blavin 2008; van Kleef et al. 2009). In this strand of the literature, the RAND health insurance experiment (HIE) is still the largest and most influential health policy study. In this 1970s era study, families at six different sites in the US were randomly assigned to 14 different health insurance plans with a varying degree of cost-sharing and observed for periods up to 5 years (Manning et al. 1987; Newhouse 1993). Since then, a large number of studies on the impact of cost-sharing on the demand for medical care emerged from the HIE, most published in the 1980s (see Zweifel and Manning 2000 for an overview). In addition to the HIE, there exists more recent empirical evidence on how cost-sharing affects the demand for health care (Chiappori et al. 1998; Van De Voorde et al. 2001; Cockx and Brasseur 2003; Goldman et al. 2004; Winkelmann 2004; Crown et al. 2004; van Vliet 2004; Landsman et al. 2005; Gerfin and Schellhorn 2006; Gaynor et al. 2007; Goldman et al. 2007; Schreyögg and Grabka 2010; Chandra et al. 2010). Baicker and Goldman (2011) as well as Swartz (2007) provide excellent state-of-the-art overviews of the effects of demand-side cost-sharing on health care utilization, health outcomes, and health spending.

Most studies cited above study solely the impact of cost-sharing for a particular health care service on the demand for this particular health care service, assuming the absence of substitution or “offset” effects. Substitution effects would occur if an increase in cost-sharing for health care service X led to a decrease in the utilization of X but to an increase in the utilization of health care service Y. Within the context of the HIE, no evidence for substitution effects due to higher cost-sharing is found. Nor did the HIE provide evidence for adverse health effects due to a lower health care utilization—for the general population. However, among the poor and sick, the HIE does find evidence for adverse health effects (Newhouse 2004). In addition, recent US studies show that an increase in cost-sharing for medically necessary prescription drugs may not only decrease the demand for prescription drugs, but may also result in higher outpatient and inpatient care utilization (Chandra et al. 2010; Gaynor et al. 2007). On the other hand, with respect to non-prescription drug medical services, there exists empirical evidence that different treatments may be complements rather than substitutes (cf. Phelps and Mooney 1993).

This paper evaluates the effectiveness of different cost containment measures in the market for rehabilitation care using rich individual-level household survey data from the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP). These data are representative for Germany, the most populous European country with 82 million citizens. Beginning in 1997, Germany implemented various health reforms in order to reduce the utilization of rehabilitation care services. Before the reforms went into effect, experts claimed that around a quarter of all inpatient rehabilitation treatments were medically unnecessary (Schmitz 1996; Sauga 1996).

Ziebarth (2010) shows that the price elasticity of demand for rehabilitation care is about \(-0.4\)—an estimate that is in line with the consensus price elasticity estimates in the literature on health care (Wedig 1988; Keeler et al. 1988; Zweifel and Manning 2000). An general example of rehabilitation care is physical therapy to restore functioning and avoid work disability after an accident, disease, or injury. Hence, rehabilitation care has an inherent preventive component (cf. Mukhopadhyay and Wendel 2013). Rehabilitation services play an important role both in Germany as well as in many other health care systems; however the health economics literature on this topic is surprisingly scant (cf. Frölich et al. 2004; Ziebarth 2010; Augurzky et al. 2013; Sood et al. 2013 for notable exceptions).

In 1995, 1.9 million patients in Germany underwent inpatient rehabilitation therapy and €7.6 billion (0.4 % of GDP) were spent on these programs. In 2011, despite population aging, the total number of treatments still amounts to 1.9 million and has been fluctuating procyclically in the last two decades. However, the relative importance of rehabilitation care has declined over time. The €8.4 billion spent in 2011 only represented 0.3 % of GDP (German Federal Statistical Office 2013). In Germany, every year, almost 8 % of the elderly and 3.5 % of the nonelderly have post-acute rehabilitation treatments, demonstrating the relevance of this type of medical care. In the representative dataset underlying this analysis for Germany—as in the US—13 % of the population are over 65. The US operates currently 1,200 Medicare-certified Inpatient Rehabilitation Facilities (IRF) and spent $6.3 billion for 360,000 Medicare beneficiaries in 2010 (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) 2012). Relating the 360,000 Medicare rehabilitation treatments to the 50 million total beneficiaries, the rate for the US would be lower than in Germany—0.7 %. However, the costs per case are almost three times as large ($17,000 vs. €4,400=$6,000).

The first cost containment reform evaluated in this paper doubled the daily copayments for rehabilitation care. The second reform increased waiting times between two treatments and reduced the legally codified standard length of the therapy. The third reform gave employers the right to deduct 2 days of paid vacation for every 5 days that employees were unable to work while in inpatient rehabilitation care. The fourth reform cut the federally mandated sick pay level from 100 to 80 % of foregone gross wages during rehabilitation care.

The first two reforms only affected people insured under the German mandatory health insurance (MHI), which covers 90 % of the population. Only specific subgroups have the right to opt out of this public system and to insure their health risks in a private health insurance (PHI) market. People insured under this second tier of the German health insurance system—the PHI—were not affected by the first two reforms. The other two reforms, cutting paid leave, affected only employees in the private sector. The differential treatment of the reforms provides mutually exclusive subgroups that were affected differently by the reforms. By means of conventional difference-in-differences (DID) models and with use of the SOEP panel data, one can then disentangle the causal effects of these cost containment measures on the utilization of inpatient rehabilitation care.

Ziebarth (2010) solely exploits the copayment reform to estimate the price elasticity of demand for different types of rehabilitation services. Thus, the first contribution of this paper is to evaluate the effectiveness of direct cost containment measures—such as copayment increases, which apply to a defined population and do not allow partial compliance—as compared to indirect measures—such as decreasing legal minimum requirements. Such indirect measures necessarily lead to partial compliance since they only increase employers’ options to regulate work conditions at the firm level. The second contribution of this paper is to test for substitution effects, i.e., whether the decrease in the utilization of post-acute rehabilitative care increased non-acute outpatient doctor visits. The third contribution of this paper is to analyze whether the decrease in rehabilitation treatments led to adverse health outcomes and increased (work) disability. Finally, given the absence of offset and adverse health effects, one can then roughly calculate the cost savings effect from the perspective of the public insurance scheme. Note that the assessment of substitution and health effects is essential for a comprehensive evaluation of cost containment measures.

The empirical results show that doubling the copayments was, by far, the most effective cost containment instrument. It led to a significant decrease in rehabilitation care therapies of about 20 %. Moreover, evidence from aggregated administrative data suggests that the reduction in the legally defined standard length of the therapies was effective in reducing the average duration of treatments. However, there is no evidence that the cuts in paid vacation and sick pay levels significantly reduced the demand for rehabilitation care. Unlike Chandra et al. (2010) and Gaynor et al. (2007), but in line with the HIE and McKnight (2006), this study does not find evidence for substitution effects in the form of increased outpatient doctor visits. Nor does it find evidence for (short-term) adverse health effects.

Based on aggregated administrative data, back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that, jointly, all reforms reduced annual public spending for rehabilitation care by €800 million or 13 %. Although the length of treatments decreased, the doubling of daily copayments raised additional revenues for the social insurance system of about €400 million per year.

The next section describes some features of the German health care system and gives more details about the reform. The “Dataset and variable definitions” section explains the dataset and the variables used. The subsequent section specifies the estimation and identification strategy. Estimation results are presented in the “Results” section and the “Discussion and conclusion” section concludes.

The German health care system and the policy reforms

The German market for rehabilitation care services

In Europe, there is a long tradition of rehabilitation care treatments at health spas to recover from poor health. Since the time of the Roman Empire, doctors have sent patients to “take the waters” in order to recover from various disorders. In Germany, inpatient rehabilitation care treatments are usually combined with various types of physical therapy, often including electrotherapy, massage, underwater exercise, ultrasonic therapy, health and diet education, stress reduction therapy, and cold and hot baths as well as mud packs.Footnote 1 Rehabilitation care therapies require the patients to follow a strict daily schedule. At the beginning of a rehabilitation therapy, depending on the patient’s diagnosis and medical necessities, a physician determines the type and frequency of the physical therapies and the daily schedule is set up. The exact daily schedule varies from patient to patient but, in general, therapies are scheduled from 9 am until 5 pm.

The German MHI covers about 90 % of the German population. Employees whose gross income from salary is below a defined income threshold (2013: €4,350 per month) are compulsorily insured under the MHI (cf. Schut et al. 2003). The MHI fully covers, apart from small copayments, rehabilitation care therapies. The German market for rehabilitation care is said to be the largest worldwide. In 1995, a total of €7.6 billion was spent on rehabilitation care, accounting for more than 4 % of all health expenditures in Germany. Around 1,400 medical facilities with 100,000 full-time (equivalent) staff members treated 1.9 million patients, who stayed an average of 31 days each (German Federal Statistical Office 2013). Providers are reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis. The reimbursement scheme did not change in the time period studied.

Rehabilitation care services require a physician’s prescription, and the individual must submit an application for treatment to his or her MHI sickness fund (=health plan).Footnote 2 The role of the patient in the application process is central. On the one hand, well informed patients may push their doctors to recommend them for rehabilitation care, and doctors may comply simply out of the fear of losing patients given the competition on the market and the free choice of doctors. On the other hand, patients may not accept their doctor’s recommendation for rehabilitation care.

After authorization by the MHI sickness fund, the prescribed treatment is provided in an approved inpatient medical facility under contract with the MHI fund. These medical facilities are usually located in rural communities licensed by the state as Kurorte, or spa towns. For a community to be granted such a license, it must fulfill several conditions established in state legislation: pure air and location near the seaside or mineral springs. The idea of providing patients a healthy change of environment is integral to the treatment program.

Germany is one of the few countries worldwide with two coexisting independent health insurance systems. In addition to MHI, PHI covers private-sector employees above the aforementioned income threshold who opted out of the MHI, public-sector employees, and the self-employed who opted out of the MHI. Coverage is provided under a range of different health plans and insurance contracts are subject to private law. Health care benefits, including rehabilitation treatments, are determined in a variety of private contracts at the beginning of the insurance period. Switching between the MHI and PHI is (almost) prohibited. Even switching between private health insurers is extremely rare since private insurers are legally required to build up reserves for each individual. Until 2009, these reserves were not transferable.

Consequently, in Germany, public health care reforms apply only to the MHI, not to the PHI. This paper uses privately insured as a control group in the assessment of the MHI policy reforms.

The cost containment policy reforms

At the end of 1996, the German government implemented four health care reforms. The first three were designed to directly dampen the demand for rehabilitation care, based on the suspicion of a high degree of moral hazard in the market for rehabilitation care. Prior to the reform, experts estimated that around a quarter of all treatments prescribed were medically unnecessary and rather a form of subsidized wellness holiday (Schmitz 1996; Sauga 1996). The fourth reform was designed to tackle moral hazard in the decision to take sick leave and may have indirectly affected the demand for rehabilitation care as well.

The first reform doubled daily copayments. In West Germany, as of January 1, 1997, copayments for rehabilitation care therapies increased from DM 12 (€6.14) per day to DM 25 (€12.78) per day. In East Germany, the copayments increased from DM 8 (€4.09) to DM 20 (€10.23) per day. This reflects an increase of 108 (150) %. The absolute increase per treatment amounted to around €150 in East and West Germany (German Federal Statistical Office 2013). Before the reform, for those who received rehabilitation care in the SOEP, the total copayment per treatment was 12 % of the monthly net wage. After the copayment doubling, the copayment sum also doubled to 24 % of the monthly net wage.Footnote 3

The second reform reduced the standard length of rehabilitation care therapies from 3 to 4 weeks. Only the medical personnel of the facility—after consultation with the health insurance—have the authority to approve deviations from the standard, legally codified, length of therapy. Together with this reduction in therapy duration, the minimum interval between treatments was increased from 3 to 4 years. Both reform elements—the reduced standard length of therapy and the extended waiting period—are only effective conditional on the non-existence of urgent medical reasons for treatment.

The third reform allowed employers to deduct 2 days of paid vacation for every 5 days that an employee was unable to work due to a rehabilitation care treatment.

The fourth reform decreased statutory short-term sick pay from 100 to 80 % of foregone gross wages. German social legislation provides employees with paid sick leave for rehabilitation care treatments in addition to paid vacation. Hence, one would expect that the latter two reforms, which allowed employers more leeway in reducing paid leave, to have an effect on the demand for rehabilitation care. Using the average net wage of the treatment group in the sample, the 20 % cut in sick pay would represent an increase in costs for a 3-week rehabilitation care therapy of about €180 or 14 % of the monthly net wage, i.e., it is almost identical to the copayment increase. However, this calculation is based on the underlying assumption that employees take a 3-week extra sick leave when they go on rehabilitation care—in addition to their paid vacation and in comparison to the counterfactual scenario of no consumption of rehabilitation care.

Table 1 displays the various subgroups of insured people who were affected differently by the four cost containment measures. Subgroup (1) comprises the vast majority of Germans: private-sector employees who are insured under the MHI. They were affected by all reforms discussed above (Treatment Group 1). Treatment Group 1 contains 23,530 observations.

In contrast, subgroups (2) to (5) were not affected by either the cut in statutory sick pay or the cut in paid vacation. Non-working and self-employed people are not eligible for paid leave. Public-sector employees and apprentices were exempted from the cuts in paid leave. However, since they were insured under the MHI, they were affected by the first two reforms. These subgroups are jointly defined as Treatment Group 2. Treatment Group 2 contains 37,758 observations.

Subgroups (6) to (9) were completely unaffected by all legislative changes; this Control Group contains 4,261 observations.

Dataset and variable definitions

Dataset

The empirical analysis relies on micro data from the German SOEP. The SOEP is an annual representative household panel dataset that started in 1984 and includes more than 20,000 respondents. It is similar to the BHPS in the UK, HILDA in Australia, and the PSID in the US. The SOEP surveys an extremely rich set of individual socio-economic background information with a special emphasis on the household structure and the workplace. The SOEP includes the health insurance statuses of the respondents, various health measures, as well as measures of health care utilization, such as doctor visits, hospital stays, or rehabilitation care utilization. Detailed individual-level medical claim or expenditure information is not surveyed. The SOEP is the only German dataset that covers rehabilitation treatments and is also representative for the German population. Wagner et al. (2007) provide further details about the SOEP.

Information on rehabilitation care treatments is only available for two post-reform years. In addition, the information was not surveyed in 1994. Hence, for the core analyses, data from the 1995 to 1999 waves are used, which include time-invariant information, current information, and retrospective information about the previous year. The dependent variable contains information about the calendar year prior to the interview; thus the data employed refer to the years 1994 to 1998.Footnote 4

Respondents under the age of 18, who are exempted from copayments, are excluded. The focus is on the subgroups defined in Table 1.

Dependent variable and covariates

Main dependent variable

The SOEP contains various questions about health insurance and the use of health care services. The main dependent variable rehabilitation care measures whether a respondent received inpatient rehabilitation care in a spa town in the calendar year prior to the interview; it takes the value 1 if the respondent received care, and 0 if not. The variable has been generated from the following question, which was asked in every wave from 1995 to 1999: “Did you receive inpatient rehabilitation care in a spa town in 199X?” In German, this question is even clearer because of the well-known umbrella term Kur and the inpatient treatment this entails, at a location other than the recipient’s place of residence, a Kurort or spa town, which minimizes measurement errors. The fact that we do not know the exact date of the therapy does not severely hamper the analysis, especially since such treatments are not usually carried out over Christmas or New Year’s. Hence, there is little doubt as to what year the care was received. Table 2 shows that about 4 % of all 65,549 respondents received a rehabilitation therapy in a given year.

While rehabilitation care can be considered a fairly good measure of the incidence of rehabilitation care treatments, the SOEP does not include a measure of their duration. However, as explained above, the length of treatment is regulated by social law and deviations from it are solely determined by the medical personnel and the MHI sickness fund, not by the patient. Therefore, the empirical analysis focuses mainly on the effects on the incidence, which is the key behavioral parameter in this setting and mainly influenced by the patient. Aggregated administrative data on the average duration of treatments is used as an additional outcome measure in descriptive assessments later on.

Covariates

The main empirical models make use of various control variables. These control variables capture personal and family-related characteristics such as age, female, immigrant, partner, and children. Moreover, they control for educational characteristics by using data on the highest educational degree obtained. An important determinant of the demand for rehabilitation care programs is the health status of the respondents, which is observed and controlled for (in the form of self-assessed health). The models also include covariates that measure whether the person was employed full-time, part-time, marginally, or not at all. In additional, they control for gross monthly income. To capture time-invariant regional characteristics, the models employ 15 state dummies. Regional labor market dynamics are controlled for by the inclusion of the annual state unemployment rate. Time trends are captured by year dummies. Table 2 shows a list of the covariates, as well as their means and standard deviations (SD).

Dependent variables to test for substitution effects

The SOEP surveys the number of outpatient doctor visits in the last 3 months prior to the interview. It also includes information on whether the respondent had a hospital stay and asks about the number of workplace absence days in the calendar year prior to the interview. Hence, to test for substitution effects, the additional dependent variables #doctor visits, hospital stay as well as #sick days are generated. Table 2 shows that the mean annual number of sick days is 9.7. Respondents have on average 3.1 outpatient doctor visits in the winter quarter.Footnote 5 Fourteen percent of all respondents have an inpatient overnight hospital stay.

Dependent variables to test for health effects

To test whether the reform triggered adverse health effects, four different measures of bad health as well as two measures of good health are employed as dependent variables in adverse health effects models.Footnote 6 Collapsing the highest and lowest category of the standard 5-scale self-assessed health (SAH) measure, two binary variables excellent health (mean: 0.091) and poor health (mean: 0.045) are generated. Health satisfaction is surveyed on a scale from 0 (“completely dissatisfied”) to 10 (“completely satisfied”) with the question: “How satisfied are you with your health?” The 7.2 % of all respondents who indicated a 10 are coded with a 1 on the high health satisfaction measure and the 6.3 % who indicated a value between 0 and 2 are coded with a 1 on the low health satisfaction measure. Ten percent of all respondents answered “to a great extent” to the following question “Not regarding occasional illnesses, is the fulfillment of everyday activities, e.g., in the household, your job or education, hindered by your condition of health, and to what extent?”, and they are coded with a one on the handicapped variable. Finally, the models make use of a binary variable disabled indicating the 12.9 % who are officially registered as disabled.

Treatment indicators

The “The cost containment policy reforms” section defines three mutually exclusive subsamples that were affected by different reform elements (Table 1). The empirical section makes use of three distinct DID models to assess the effectiveness of the various reforms. This requires three distinct treatment indicators for the three models in order to compare the different subsamples.

T1 has a one for the 23,530 employees in Treatment Group 1 and a zero for the 4,261 respondents in the Control Group (see Table 2). Using this treatment indicator, Model 1 with its 27,791 observations compares those who were affected by all reforms with those who were completely unaffected to assess the net effect of all reforms on the demand for rehabilitation care programs.

T2 has a one for the 37,758 respondents in Treatment Group 2 and again a zero for the 4,261 respondents in the Control Group. Thus, Model 2 has 42,019 observations and contrasts those who were affected by the first two reforms with the Control Group. In this model, the main intention is to evaluate the effectiveness of the copayment doubling, i.e., the first reform. Extended robustness checks also assess the effect of the second reform by means of Model 2.

T3 is used in Model 3, which assesses the effectiveness of reforms three and four jointly by comparing Treatment Group 1 with Treatment Group 2. It uses 61,288 person-year observations to extract the effect of the first two reforms from the net reform effect to obtain the effect of the cuts in sick leave and paid vacation during rehabilitation stays.

Estimation strategy

Difference-in-differences (DID)

One would like to measure how each reform affected the utilization of rehabilitation care programs. Thinking of the policy intervention as a treatment, one can then fit estimation models of the form:

where \(y_{ist}\) stands for the incidence of rehabilitation care programs, rehabilitation care. \(post97_{t}\) is a dummy that takes on the value 1 for post-reform years and 0 for pre-reform years. Depending on the model, \(T_{it}\) stands for one the three treatment indicators (see “Treatment indicators” section above). The interaction term between the two dummies gives us the DID estimator. To evaluate how the reform affected the outcome variable \(y_{ist}\), henceforth, the marginal effect of the interaction term \(\frac{\Delta \Phi (.)}{\Delta (post97\times T)}\) is always computed and displayed.Footnote 7 \(\Phi (.)\) is the cumulative distribution function for the standard normal distribution. Additional time dummies, \(\rho _t\), control for common time shocks. State dummies, \(\phi _s\), account for permanent differences across the 16 German states along with the annual state unemployment rate that controls for changes in the tightness of the regional labor market and that is included in the \(K\times 1\) column vector \(x^{\prime }_{ist}\). The other \(K-1\) regressors are made up of personal controls including health status, educational controls, and job-related controls as explained in “Dataset” section.

Identification

The main identification assumption of DID models is the common time trend assumption. This assumption should hold conditional on all available covariates. In almost all natural experiments and non-randomized settings, controlling for a rich set of covariates is important since the control and treatment groups mostly differ with respect to their observed characteristics. This is also true in the present case. For example, in comparison to the Control Group, Treatment Group 1 includes more females and immigrants, and the employees are less educated. As compared to the Control Group, the people in Treatment Group 2 are younger and more likely to be full-time employed. Differences in the sample composition are adjusted using the described rich set of socio-economic background characteristics. Recall that we observe and control for the health status of the respondents. Likewise, adjustments are made for time effects, persistent differences between states, and the annual state unemployment rate.Footnote 8

The common time trend assumption assumes the absence of unobservables that generate different outcome dynamics for the treatment and control group. It is worth mentioning that a selection on observables story is very plausible in the present setting. In the first place, it is the MHI/PHI insurance status that determines treatment (see Table 1). Almost all factors that determine whether respondents are insured under the MHI or PHI—such as occupational status and income—are observed. It is important to understand that selection into the different treatment groups happens by design, based on observables, but is not treatment-related. However, one can also empirically test for the presence of distorting unobservable effects by estimating placebo regressions for years without a reform. The next section makes use of this method.

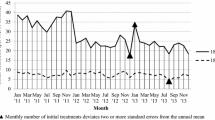

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the outcome variable for the treatment and control groups over time. Figure 1a displays the “raw” variable means. Please note that level differences in the outcome variable are no threat to the DID estimates since the treatment indicator dummy nets out these level differences. Despite level differences, one observes very parallel unconditional trends for the treatment groups. After the reform, rehabilitation care utilization in the control group remained fairly stable—even increased from 1997 to 1998—while we observe a clear, distinct, and parallel decrease for the treatment groups.

Figure 1b displays the predicted probabilities for each group and calendar year based on estimated probit models similar to Eq. (1). Controls include a set of time and state dummies, the set of socio-economic covariates, and a treatment indicator. While Fig. 1a yields the unconditional picture, this graph allows us to check whether the common time trend assumption holds after one adjusts for available covariates. The picture is reassuring. One observes a very parallel evolution of the predicted rehabilitation treatment probabilities for all groups over time.

The drawbacks and limitations of DID estimation are extensively debated. A particular concern is the underestimation of OLS standard errors (SE) due to serial correlation in the case of long time horizons as well as unobserved (treatment and control) group effects (Bertrand et al. 2004; Donald and Lang 2007; Angrist and Pischke 2009). To address the serial correlation issue, this paper focuses on short time horizons. In addition, to provide evidence on whether unobserved common group errors might be a serious threat to the estimates, a robustness check clusters SE on the state (16 clusters) level (Angrist and Pischke 2009).

One crucial issue—besides the absence of a control group—in most studies trying to evaluate policy reforms is selection into or out of the policy intervention. Selection issues are addressed since two almost totally independent health care systems exist side by side in Germany. On the one hand, this provides a well-defined control group. On the other hand, one does not need to fear that reform-induced selection distorted the results, as there is virtually no switching between the MHI and the PHI, and since all MHI-insured persons are covered by universal health plans. Due to strict German regulations, a switch to the PHI was only legally allowed for a small fraction of optionally MHI-insured individuals, and one can identify and exclude these cases when running robustness checks. In the dataset, only 1.6 % of those who were insured under the MHI for at least 1 year switched to the PHI between 1994 and 1998. The rate did not increase after the reform. Only 1.3 % of those who were insured under the MHI in 1995 switched to the PHI in 1997 or 1998.

To be able to fully attribute changes in the incidence to changes in the demand for rehabilitation care programs, supply-side effects should not play a role. The fee-for-service reimbursement scheme did not change over the time period studied. Moreover, there is no evidence of supply-side constraints. In contrast, there are reports about the deepest crisis in the market for rehabilitation care since the end of the Second World War (Handelsblatt 1998). According to official statistics, the occupancy rate of inpatient rehabilitation facilities strongly decreased, from 83.2 % in 1996 to 62.3 % in 1997 (German Federal Statistical Office 2013). According to economic theory, supply side shocks may also lead to changes in price and quantity. However, this paper only studies short-term effects. Reducing overcapacities usually takes time and happens in the medium- to long-terms, not in the short-run. The strong decrease in the occupancy rate can rather be seen as strong evidence for an abrupt decrease in demand triggered by the demand-side reforms.

Although the MHI and the PHI system operate independently, one might worry that spas operating at half-capacity due to the reform negotiated lower reimbursement rates with private health insurers. This was not the case since, in Germany, neither in the public nor in the private system do providers negotiate reimbursement rates individually with insurers. Also, even in the private system, reimbursement rates are centrally fixed and relative rates barely vary over time. However, one cannot totally exclude the possibility that the slight increase in rehabilitation treatments for the privately insured from 1997 to 1998 goes back to some form of provider-induced demand. If that was indeed the case, the models might slightly overestimate the reform effects.

Individuals insured under the MHI who were for some reason exempted from copayments are not identifiable. For example, people whose annual copayments for prescription drugs, health care services, or medical devices exceeded a certain percentage of their disposable household income could have applied for a case of hardship.Footnote 9 However, at that time, the German Spa Association claimed that the public was widely unaware of the exemption clauses. Therefore this should not downwardly bias the results severely.

The third reform allowed employers to deduct 2 days of paid vacation for every 5 days that an employee was absent from work due to rehabilitation care therapy. The fourth reform cut statutory sick pay up to 6 weeks per sickness episode. As shown in Table 1, the empirical models can only evaluate the two reforms jointly. In contrast to the other reforms, these two reforms are rather indirect cost containment measures, since they decreased the federally mandated minimum standards in the labor market. Since employers are always free to provide fringe benefits above the legal minimum requirements, compliance was imperfect. One cannot observe which employers enforced these reforms strictly and directly passed on the decrease in social law minimum standards to their employees. Anecdotal evidence and polls suggest that this might have been the case for about 50 % of all potentially treated, i.e., private-sector employees (Ridinger 1997; Jahn 1998). Using all private-sector employees together as the treatment group, Ziebarth and Karlsson (2010) show that the cut in statutory short-term sick pay significantly reduced workplace absences in general. This paper applies the same intention-to-treat (ITT) approach using the same data. Hence the models used here should be able to identify potential reform effects. Note that one of the main objectives of this paper is precisely to evaluate the effectiveness of direct cost containment measures—such as copayment increases, which apply to a specific population—as compared to indirect measures—such as decreasing legal minimum requirements, which only increase employers’ options to regulate work conditions at the firm level.

Results

Assessing the reforms’ effectiveness

Main models

Table 3 shows the results for Model 1, 2, and 3 and displays the “plain” DID estimate as well as the estimates obtained from Probit and OLS specifications with the full set of covariates. All models in Table 3 use an unbalanced panel, and each column represents one DID model. DID always stands for the DID estimate.

Model 1 makes use of the treatment indicator T1 and compares Treatment Group 1, which was affected by all four cost containment measures to the Control Group. All three estimates for Model 1 yield significantly negative reform effects on the utilization of rehabilitation care. Moreover, all three estimates are fairly robust and lie within the same confidence intervals. The Probit and the OLS estimates in columns (2) and (3) are especially close to one another, which suggest that functional form assumptions do not seem to matter here. The pre-reform incidence of rehabilitation care programs for Treatment Group 1 is 0.0355, i.e., 3.55 %. Relating the percentage point estimate (\(-0.0081\)) from the preferred specification in column (2) to this pre-reform incidence rate suggests that all reforms jointly decreased the demand for rehabilitation care therapies by 23 %.

Model 2 disentangles the effects of reforms one and two from the effects of reforms three and four. Reform 1 doubled the daily copayments for rehabilitation care treatments. Reform 2 reduced the legally codified standard length of the therapy and increased the waiting period between two therapies. Reform 3 cut paid vacation and Reform 4 cut statutory sick pay during rehabilitation treatments. Model 2 contrasts those who were affected by reforms one and two (Treatment Group 2) with those who were completely unaffected by any health reforms (Control Group). It employs the treatment indicator T2.

Again, all three estimates are similar in magnitude: all are negative and significantly different from zero, they are insensitive to the inclusion of covariates, and the results from the OLS and Probit models barely differ. All DID point estimates fall within the same confidence intervals as the ones in Model 1. The average pre-reform rehabilitation care incidence for Treatment Group 2 was 0.0502, and hence the \(-0.0136\) percentage point estimate of the Probit model in column (5) translates into a reform-induced decrease of about 27 %. This suggests that reforms one and two are responsible for the decrease in utilization of rehabilitation care programs. The robustness checks below provide evidence that the copayment doubling is very likely to be responsible for the bulk of this decrease. The findings suggest that the increase in waiting times did not contribute much to the decrease and that the legally codified reduction in the standard length of treatments primarily reduced the average duration of treatments.

Note that an alternative way to estimate Models 1 and 2 would be to pool groups (1) to (5) in Table 1 and include interaction terms. The resulting model contains 65,549 observations [23,530 + 37,758 (treatment group) + 4,261 (control group)]. The interaction term between the treatment indicator and the post-reform dummy yields a highly significant estimate of \(-0.0142\)—the weighted average of columns (3) and (6) of Table 3.

Model 3 compares those affected by all four reforms (Treatment Group 1) to those affected by reforms one and two (Treatment Group 2). One thereby assesses the effects of reforms three and four jointly, i.e., the cuts in paid vacation and sick pay. The results of Model 3 strongly confirm the findings of Model 1 and Model 2: columns (7) to (9) of Table 3 all yield point estimates that are very close to zero, but not statistically different from zero. The point estimates are even positive and the SE are fairly tight. All in all, there is no evidence that the statutory cuts in paid vacation and in sick pay reduced rehabilitation care significantly. There are two potential explanations for this finding. First, the cut in vacation days may not have been a binding constraint, since many employees use all or part of their paid vacation for rehabilitation care. Although entitled to take paid leave in addition to their paid vacation, many employees may fear negative job consequences, especially when unemployment rates are high (cf. Augurzky et al. 2013; Ziebarth and Karlsson 2013). Second, the cut in sick pay did not necessarily impose a limitation on the insured since their decision may have been between either going to an inpatient rehabilitation facility or simply staying home to recover. In any case, they would have been on sick leave. If necessary, physicians usually recommend inpatient treatments in spa towns, but if patients prefer to stay home on sick leave, their wishes are usually respected.

The entire setup and the fact that all results are based on a comparison of three mutually exclusive subsamples gives rise to another (suggestive) means of calculating the effects for Model 2 and the first two reforms: one can subtract the estimates from Model 3 from those from Model 1, i.e., subtract the effects of reforms three and four from the net effect of all reforms. It is easy to see that this back-of-the-envelope exercise yields very consistent alternative estimates for Model 2 that are almost identical to the direct estimates in columns (5) and (6).

Robustness checks

Table 4 displays various robustness checks. All cases focus on Model 2 and the Probit specification with all covariates included.Footnote 10

The first column of Panel A estimates a fixed-effects model. The point estimate is \(-0.0163\), significant at the 1 % level, and slightly larger—albeit within the same confidence interval—than the “standard” estimate in column (5) of Table 3 (\(-0.0136\)). Column (2) excludes 1996 from the specification. Since the reforms were first announced in December 1995, it might be that pre-reform 1996 is contaminated by either pull-forward effects triggered by the insured or by supply-side effects triggered by MHI sickness funds. For example, MHI sickness funds might have been more restrictive in the authorization of treatments due to rising public awareness and political pressure. Indeed there is some evidence of this. Omitting 1996, the DID estimate shrinks slightly in size and translates into a decrease of about 21 % in demand. Column (3) also supports this result, since the short-run reform effect obtained by comparing 1996 to 1997 is larger than the standard estimate in column (1). Please note that this is not true in a strict statistical sense since the confidence intervals overlap. Column (4) excludes the years 1996 and 1997 since pull-forward effects for 1996 might have artificially reduced demand in 1997.

Reform 2 increased the waiting period between treatments for MHI-insured from 3 to 4 years. The last column in Panel A tests whether the increase in waiting times reduced the utilization of rehabilitation care programs in the short run. The extension of the waiting period did not apply to individuals needing urgent medical treatment. People insured under the MHI have free choice of doctors, and there are almost no waiting times for doctor appointments in Germany. Thus, it is unlikely that the increase in waiting times had a substantial effect, since finding a doctor to write a prescription for treatment is not difficult. The increase in the waiting period forced patients who received treatment in 1994 (1995) to wait until 1998 (1999) instead of 1997 (1998) in the absence of urgent medical reasons. Thus, if the increased waiting period had a substantial impact, one would measure a stronger reform effect for 1997 than for 1998. Column (5) of Table 4 shows that the reform effect in 1997 was not stronger than in 1998. This is evidence that the increased waiting period had no significant (short-term) effect on the demand for rehabilitation care.

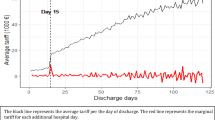

The second element of Reform 2 was the reduction of the legally codified standard length of rehabilitation care from 3 to 4 weeks. Since the SOEP does not include information on the length of therapy, one cannot estimate the effect of the reduction in the standard length using a regression model. However, official data is available on the average treatment length and the total number of days spent in inpatient medical facilities for rehabilitation care treatments. According to these data that represent average values for the whole of Germany, the average treatment length for all insured individuals decreased by almost 4 days from 31.0 (30.2) days in 1995 (1996) to 27.3 (26.4) days in 1997 (1998) (German Federal Statistical Office 2013). This yields evidence that reducing the legally codified standard length was an effective tool to reduce the real length of treatments. On the other hand, it is unlikely that reducing the legal standard length of therapies had a substantial impact on the incidence of rehabilitation care therapy, i.e., on the decision to go to a health spa. From a theoretical point of view, it is not clear whether reducing the standard length from 4 to 3 weeks made rehabilitation therapies more or less attractive. However, after all, one cannot ultimately prove that the extensive margin was not significantly affected by an exogenous change in the intensive margin.

Panel B of Table 4 presents additional robustness checks. The first three columns imply that treatment selection and panel attrition pose no threat to the results. The first column balances the sample. Column (2) weights the standard regression with the inverse probability that a respondent did not drop out of the sample in the post-reform period. The third column excludes the only population group that could have avoided the reforms. Only respondents who were optionally insured under the MHI system had the possibility by opting out of the MHI. However, opting out is essentially a lifetime decision—since switching back is almost impossible—and therefore very rare. Column (4) excludes all individuals who switched between the control group and one of the treatment groups in one of the years under consideration. The DID estimates from all four robustness checks are close in size to the standard estimate in column (5) of Table 3 and confidence intervals largely overlap. Each estimate is significantly different from zero.

Column (5) excludes health variables since the health status might be endogenous if measured after a rehabilitation care therapy. However, since the models routinely employ the reported health status of the previous interview, this should not be an issue. The robustness check estimate confirms this assumption.

The last column in Panel B clusters SE on a higher aggregated level to test whether the common group error structure might be a serious issue in this setting (Angrist and Pischke 2009). As can be seen, there is no evidence of this.

Table 5 displays placebo regressions for Model 1, 2, and 3. Placebo regressions are a common way of testing the common time trend assumption. Finding significant reform effects for years without a reform would cast serious doubts on the plausibility of the common time trend assumption. Table 5 uses 1994 and 1995 as pseudo-reform years and, apart from that, the same setup as above. All twelve placebo regression estimates are close to, and not significantly different from, zero.

Testing for substitution effects

To test for substitution effects, we run the same model as in Eq. (1), but use the number of sick days, outpatient doctor visits, and inpatient stays as dependent variables in three different models. As in Table 4, we focus on Model 2 (Treatment Group 2 vs. the Control Group). Running Model 1 and comparing Treatment Group 1 to the Control Group essentially does not alter the results.Footnote 11

Column (1) of Panel A shows the effect on the number of paid sick leave days.Footnote 12 The point estimate is \(-0.4038\), not statistically significant, and the results yield no evidence that employees called in sick more often as a result of the decreased utilization of rehabilitation care. Interestingly, a rough back-of-the envelope calculation would suggest that the average annual number of absence days due to rehabilitation care would have decreased by about 0.3 days per employee as a result of the reform—under the assumption that, pre-reform, employees did not use their vacation days for rehabilitation care.Footnote 13

Column (2) tests whether individuals substituted outpatient doctor visits for post-acute rehabilitation treatments. One does not find evidence that this was the case, but rather a precisely estimated 0.4239 decrease in the number of office visits. A closer look facilitates the interpretation of this finding: In the pre-reform period, respondents in the treatment group with rehabilitation care treatments had 5.9 outpatient office visits in the 3 months preceding the interview. The number of office visits among these respondents (with pre-reform rehabilitation care) decreased to 5.1 in the post-reform period.Footnote 14 Among respondents without rehabilitation care treatments in the pre-reform period, the number of doctor visits remained fairly stable (2.7 pre-reform vs. 2.8 post-reform). This means that those who had a rehabilitation stay pre-reform reduced both their likelihood of a rehabilitation therapy and their doctor visits post-reform. In contrast, those who did not use rehabilitation therapy pre-reform did not reduce their doctor visits. Taken together, this is strong evidence against the notion that patients systematically substituted outpatient doctor visits for post-acute rehabilitation care. It is evidence that these two types of medical care are complements rather than substitutes.

Column (3) reinforces what we found in columns (1) and (2). There is not much evidence for offset effects. The estimated hospitalization effect is statistically significant and negative. However, in light of very inelastic price elasticity estimates for inpatient treatments of around \(-0.1\) (Manning et al. 1987), it is unlikely that the drop implies that these people forwent medically necessary acute care treatments because of the higher cost-sharing for post-acute treatments. In fact, the phrasing of the German SOEP hospital stay question strongly suggests that respondents counted post-acute inpatient rehabilitation facility stays as “hospital stays”, which is technically true. This may help to explain the significant decrease in inpatient stays, which can be seen as a robustness check for the main findings. Note that the reported decrease in overall inpatient treatments of about 17 % matches the decrease in inpatient rehabilitation treatments almost exactly. Repeating the descriptive exercise from above also reinforces the conclusion: 32 % of all respondents with pre-reform rehabilitation treatments also indicated that they stayed in an inpatient facility overnight. Tracking these respondents reveals that this figure dropped to 24 % in the post-reform period. In contrast, only 11 % of respondents in Treatment Group 2 without rehabilitation therapies in pre-reform years had hospital stays. This share remained fairly constant in post-reform years (13 %).

Unfortunately, the SOEP data does not include information on prescription drug intake. Hence, theoretically, patients might have systematically substituted pharmaceuticals for rehabilitation care. This is, however, very unlikely for various reasons: First, from a medical point of view, post-acute rehabilitation is mainly about physical and preventive therapy to recover from a disease or injury in order to prevent (work) disability. If medication is needed, prescription drugs are usually taken in addition to, not as substitute for, rehabilitation therapy. Second, in Germany—unlike in the US—commercials for prescription drugs are prohibited and drug use is less common. In the US, per capita sales for pharmaceuticals sum to a total of $687 in 2009. In Germany, this figure was only $337 (in US$ PPP, VFA (2011).) Finally, administrative aggregate data does not provide any evidence for offset effects. The sales of self-medication drugs only increased slightly from 1996 to 1997 (€4.4bn to €4.6bn) and did not increase at all from 1997 to 1998. Total MHI spending on prescription drugs decreased from 1996 to 1997 from €18.9 to €18.6 billion (German Federal Statistical Office 2013).

Testing for adverse health effects

Panel B and C of Table 6 display six DID models that all test for adverse health effects which may have been induced by the decrease in rehabilitation care utilization. Again, DID models similar to the one in Eq. (1) are run; however, they use six different health measures as dependent variables (see Table 2). Again, Model 2 (Treatment Group 2 vs. Control Group) is employed but the results also hold for Model 1 (Treatment Group 1 vs. Control Group).

As seen, there is no evidence for adverse health effects. All point estimates are close to zero in size and the SE are relatively tight. The absence of negative health effects, at least in the short-run, is also confirmed when focussing on subsamples of respondents in poor health.Footnote 15

Reduction in health expenditures

Since reducing moral hazard and hence public health expenditures was the main goal behind the policy reforms, one can perform a rough calculation of the decrease in public rehabilitation care expenditures using official data. Official data is available on the total sum that was spent on rehabilitation care by the public social insurance. Taking the simple difference in expenditures in 1997/1998 versus 1994/1995Footnote 16 yields a total public insurance savings estimate of €835 million per year. This represents a decrease in spending of 12.5 % (German Federal Statistical Office 2013). It should be kept in mind, however, that this is a before-after savings estimate and assumes zero trends in the control group. Also note that the total savings estimate is smaller than the estimated decrease in the number of treatments since the length of the treatments decreased as well.

As copayments were doubled, this reform raised additional revenues for the public social insurance. Official data show that the total number of rehabilitation care days consumed decreased by 22 % from 57 million in 1994/1995 to 44.5 million in 1997/1998 (German Federal Statistical Office 2013). Multiplying each sum by the pre- and post-reform copayments and taking the difference suggests that increasing copayments not only effectively dampened the demand for rehabilitation care but it also raised additional social insurance revenues of about €435 million per year.

Of course, generalizing this rehabilitation care savings estimate to an overall health care expenditure savings estimate is only valid in the absence of substitution and adverse health effects. As shown in Table 6 there is no empirical evidence for substitution or adverse health effects. It should be kept in mind, however, that this paper exclusively focuses on short-run estimates up to two post-reform years. Hence the interpretation and discussion of the results cannot be generalized to the medium- and long-run (also see Discussion and Conclusion section below). Also keep in mind that this savings estimate is a savings estimate from the public insurance perspective, which ignores increased out-of-pocket spending and the financial burden for affected individuals.

Lastly, the official data cited above show an increase in rehabilitation treatments from 1997 to 2000. This could be evidence for catch-up demand and that the cost containment measures were only effective in the short run. However, no causal inference can be drawn from the aggregated data since they blend treatment and control groups together. Maybe more importantly, one cannot net out any confounding factors that may play a significant role in the causal analysis. For example, from 1997 to 2000, the unemployment rate in Germany strongly decreased from 11.4 to 9.6 %. It has been shown that fear of unemployment is a highly significant determinant of the demand for rehabilitation care in Germany (Augurzky et al. 2013). While the econometric models in this paper control for the annual county-level unemployment rate, it is likely that the aggregated increase in rehabilitation treatments from 1997 to 2000 was due to the decrease in unemployment and not due to catch-up demand. This is in line with column (6) of Panel A in Table 4, which does not provide any empirical evidence for catch-up demand from 1997 to 1998.

Elasticity estimates and evaluation of cost containment measures

Health economic studies that assess health care demand elasticities are not necessarily evaluating cost containment aspects from a health care system perspective. For example, Ziebarth (2010) exploits solely the copayment reform also studied in this paper, but only to derive the demand effects and price elasticities for various types of rehabilitation care. In contrast, this paper does not derive elasticities and does not differentiate between different types of rehabilitation treatments. Instead it makes the following contributions:

First, this paper compares the relative effectiveness of four different cost containment measures that all targeted the demand for rehabilitation treatments, were implemented at the federal level at the same time, and can be evaluated within a unifying framework from a public policy perspective.

Second, to be able to conclude that a reduction in health care demand translates into true cost savings for the health care system, one has to demonstrate the absence of substitution effects.

Third, a comprehensive assessment of public policy cost containment strategies requires to look at health effects. If reductions in health care consumption lead to adverse health effects one could question the welfare effects of the according cost containment measures.

Finally, considering the finding for substitution and health effects, this paper derives the short-run health care cost savings effects for the German health care system. Ziebarth (2010) neither compares different cost containment measures nor does he assess substitution or health effects or evaluate the reforms from a public policy cost containment perspective. Consequently, only this study can estimate the health care cost effects of the reforms studied.

Discussion and conclusion

This article empirically compares the effectiveness of different cost containment measures. In 1995, the German public social insurance system spent €7.6 billion for 1.9 million rehabilitation care treatments. Starting in 1997, several health care reforms were implemented in order to dampen the demand for rehabilitation care therapies, to fight moral hazard, and to decrease public health expenditures.

The consistency of the findings across different DID models, combined with the results of the robustness checks, lets us conclude the following: first, the combined reforms decreased the demand for rehabilitation care therapies by about 20 %. Second, doubling the daily copayments for rehabilitation care treatments was the most effective cost containment measure. This measure was responsible for the major part of the total decline in demand.

Third, descriptive evidence from official data suggests that a legally codified reduction in the standard length of the therapies was effective in reducing the true length of the therapies. On the other hand, this study finds no evidence that increasing the waiting times between two treatments had any significant effect on the decision to go for rehabilitation care.

Fourth, while these policy measures applied universally to every publicly insured person, two other measures evaluated here applied in a rather indirect way. They reduced federally mandated labor market minimum standards and increased the employers’ options to set firm-specific employment conditions. The first of these indirect measures allowed employers to deduct 2 days of paid vacation for every 5 days that an employee was unable to work due to a rehabilitation care therapy. The second reform cut the statutory sick pay that employees are eligible for while undergoing rehabilitation care treatments. There is no evidence that these soft cost containment measures were effective in reducing the demand for rehabilitation care. The latter finding could be due to the fact that many employees use their paid vacation for rehabilitation care treatments because they fear negative job consequences, especially when unemployment rates are high (Augurzky et al. 2013). Thus indirect measures that leave room for partial compliance are far less effective in achieving a specific predetermined policy goal; direct measures that lead to full compliance among the target group are much more effective.

Fifth, in contrast to Gaynor et al. (2007) and Chandra et al. (2010), but in line with the findings from the RAND HIE and McKnight (2006), this paper does not find evidence for substitution effects in the form of higher outpatient doctor visits as a result of the reforms. The empirical findings suggest that inpatient rehabilitation treatments and outpatient doctor visits are complements rather than substitutes.

Sixth, there is no evidence that the decrease in rehabilitation treatments led to adverse health effects in the short-run. Like the offset effect result, this finding is also in contrast to Gaynor et al. (2007) and Chandra et al. (2010), but in line with the findings from the RAND HIE and McKnight (2006). The difference in findings might be due to several reasons: Chandra et al. (2010) focus on the elderly, while this study—as well as the HIE study—covers the entire population. Also, it should be taken into account that Germany has a fairly generous universal public health insurance scheme with very low access barriers and free choice of providers. There exist no deductibles or coinsurance rates and the overall degree of cost-sharing is low—thus the initial coverage level from which cuts were implemented was quite high. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, while this paper studies the market for rehabilitation services, Chandra et al. (2010) and Gaynor et al. (2007) analyze the effects of an increase in prescription drug copayments on prescription drug utilization, doctor visits, and hospitalization. Hence, the findings do not contradict each other. While it is perfectly plausible that a decrease in the consumption of medically necessary physician-prescribed acute care drugs leads to an increase in hospitalizations, it is also plausible that a decrease in post-acute rehabilitation care does not necessarily lead to offset effects. For example, McKnight (2006) finds that a reduction in the use of home health care was not associated with negative health effects in the US.

A last exercise uses aggregated administrative data and roughly calculates the (short-term) reduction in public health expenditures that was induced by all cost containment reforms. The back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that rehabilitation care expenditures decreased by about €800 million (\(-12.5\,\%\)) per year due to the utilization decline. Moreover, doubling copayments raised additional annual revenues of about €400 for the public insurance.

Every health care system has unique institutional features, and coverage for rehabilitation care in the German market is extremely generous in an international comparison. In this respect, it is unlikely that the findings of this study can be directly applied to other countries. For example, in the US, the rate of the elderly who undergo rehabilitation care is below 1 % as compared to 8 % for the German elderly. In addition, the rehabilitation care provided in the German system is broader defined and includes more preventive elements like diet education and physical therapy—even for inpatient post-acute therapies which are typically carried out in scenic state licensed spa towns. However, despite the differences in institutional features, rehabilitation care also plays an important role in the US and other health care systems and is an underresearched field in health economics. In 2011, Medicare provided 360,000 inpatient rehabilitation treatments with an average length of stay of 13 days (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) 2012). Population aging leads to an increasing importance of this type of health care services, particularly in interaction with the disability insurance (DI) system and in order to prevent work disability (cf. Autor and Duggan 2003; Burkhauser and Daly 2011). Since consumer cost-sharing seems to be a very effective demand parameter, fostering rehabilitation treatments to prevent rising DI rolls would suggest low(er) cost-sharing amounts for this type of preventive medical care.

A second example illustrating the broader relevance of the findings refers to Medicare reimbursement. While Medicare Part A pays 100 % for a stay in a Medicare certified IRF as long as it is considered “medically necessary” and requires 3 hours of daily treatment, recent US cost-containment policies focused on the supply side. In 2002, policymakers radically changed IRF provider reimbursement from a retrospective to a prospective system, which led to controversial discussions, not only about the quality of care provided (Congressional Research Service 2006; Buntin et al. 2005; Paddock et al. 2007). Sood et al. (2013) conclude that the change in reimbursement actually increased per case payments to IRFs as well as the overall admission volume but decreased the intensity of care. Sood et al. (2013) also provide evidence for negative health effects and spillover effects to other post-acute settings.

At least in the short-run, the German setting provides neither evidence of negative health effects nor evidence that the decrease in post-acute rehabilitation care led to substitutive outpatient care consumption. These findings, together with the estimated 20 % decrease in utilization, allows one to conclude that the policy reforms succeeded in reducing a large degree of moral hazard in the German market for rehabilitation care. Such a conclusion would be reinforced by the pre-reform claims of health experts suggesting that up to a quarter of all pre-reform therapies were of questionable medical benefit.

It should be kept in mind, however, that one cannot prove that the decrease in demand goes back to a decrease in medically unnecessary treatments. First of all, demand for medical care may decrease with increasing prices, independent of the medical necessity of the care provided. Second, it is out of the scope of this paper to conduct a cost-effectiveness or cost-benefit analysis, which would shed more light on the issue of medical necessity. Third, this paper only estimates the short-term effects—up to two post-reform years—on health and utilization. In particular post-acute rehabilitation care has an inherent preventive care component. Post-acute rehabilitation care may lead to long-term health improvements that could exert positive external effects and reduce health expenditures in the long-run.

Notes

This paper does not differentiate between different “types” of rehabilitation therapies. Distinctions are mostly made by German Social Law and are rather technical. Here the outcome variable in the empirical models captures all types of rehabilitation treatments. The reforms analyzed apply to “inpatient” medical rehabilitation, which was quantitatively, by far, the most dominant type of rehabilitation treatments. Vocational rehabilitation that intends to integrate disabled people into the labor market is disregarded here (cf. Jönsson and Skogman Thoursie 2012). In 2007, only 68,000 cases were counted in Germany (Rauch et al. 2008). “Outpatient” medical rehabilitation is carried out at the place of residence of the patient and has become increasingly popular in recent years; it is also outside the scope of this paper. In 1997, it accounted for only 1 % of all rehabilitation therapies (Rauch et al. 2008).

In the German system, there exist about 150 different MHI sickness funds (=health plans). Individuals are free to choose among those plans. The health plan coverage is heavily regulated under Social Law. Rehabilitation treatments are federally mandated benefits; coverage, including cost-sharing, is identical for all 150 health plans.

Using aggregated administrative data and dividing total spending (€7.6 billion) by the total number of days consumed (58.8 million) one obtains a daily cost estimate of about €130 in 1995 (German Federal Statistical Office 2013). Thus, the post-reform copay would equal 10 % of total costs.

If the respondent was interviewed in two subsequent waves, e.g., in 1994 and 1995, time-variant data from questions posed in the first year dealing with the first year are matched with retrospective data obtained from questions posed in the second year dealing with the first year. For example, in 1994 and 1995, respondents were asked about their current health status and about their insurance status during the previous year. Hence, the 1994 data on health status is used together with the 1995 data on insurance status if the respondent was interviewed in both years.

More than 80 % of all respondents were interviewed between January and April. Because of seasonal effects, doctor visits are always higher in the winter months, which is why we would substantially overestimate the annual number of doctor visits if we multiplied these figures by the factor four.

In contrast to the control variables, when the health measures are used as dependent variables, they are generated differently: Since one would like to test for health effects post rehabilitation, we leave the information as it was surveyed. This means that the models use information about rehabilitation care in the calendar year prior to the interview together with information about the respondents’ health status at the time of the interview, i.e., the health status is definitely measured after a potential rehabilitation therapy.

Puhani (2012) shows that the advice of Ai and Norton (2004) to compute the discrete double difference \(\frac{\Delta ^2 \Phi (.)}{\Delta post97 \Delta T}\) is not relevant in nonlinear models when the interest lies in the estimation of a treatment effect in a DID model. Using treatment indicators, the average treatment effect on the treated is given by \(\frac{\Delta \Phi (.)}{\Delta (post97 \times T)} = \Phi (\alpha + \beta \text {post97} + \gamma \text {T} + \delta \text {DID}+ x^{\prime }\psi + \rho + \phi )- \Phi (\alpha + \beta \text {post97} + \gamma \text {T} + x^{\prime }\psi + \rho + \phi \)), which is exactly what is calculated and presented throughout the paper.

The detailed descriptive statistics by treatment groups as well as the regression results showing the determinants of rehabilitation care are available upon request.

The usual threshold is 2 % of disposable household income; for people with chronic diseases it is 1 %.

The results for Model 1 are similar and available upon request.

The estimation results are available upon request.

This specification excludes non-working respondents, which is why the sample size drops to 17,878 obs. Note that this specification estimates the effect of the copayment doubling, and hence the decrease in rehabilitation care utilization, on workplace absences. Treatment Group 2 was not affected by the cuts in statutory sick pay.

This simple exercise multiplies the number of working respondents in Treatment Group 2 with the pre-reform treatment length from administrative data (see above) and subtract the total number of post-reform rehabilitation care absence days. Dividing the resulting decrease in the number of rehabilitation care-related absence days (4,725) by the number of working respondents in Treatment Group 2 (14,678), one obtains a reform-related decrease in absence days of 0.32 per employee.

Under the assumption that the necessary prescription for rehabilitation care “mechanically” triggers an additional 1–2 office visits per year, the estimated decrease in doctor visits might entirely be triggered by the decrease in rehabilitation care utilization. An alternative explanation could refer to a supply-side reform that was implemented in July 1997 and introduced quarterly budgets for outpatient physician reimbursement. However, from a theoretical point of view, it is unclear whether these budgets actually decreased annual office visits or just postponed re-appointments to the next quarter. Moreover, it is not clear how reimbursement incentives actually affect physician treatment behavior (Glied and Zivin 2002). As discussed in “The German market for rehabilitation care services” section, in Germany, the competition among primary care physicians for patients is intense and there exists free provider choice. Part of the decrease in office visits might also be triggered by an increase in copayments for prescription drugs and MHI-insured that went into effect in July 1997 (Winkelmann 2004). However, according to a survey conducted at the time of the reform, 80 % of all respondents claimed that it did not affect their number of office visits (Lauterbach et al. 2000). In addition, various hardship clauses and exemptions—especially for needy people—applied. If substitution effects in terms of more office visits were triggered by this reform, it would still not be a threat to the estimates and conclusions from Panel A. In that case we would underestimate the negative effects on office visits.

The results are available upon request.

The year 1996 is omitted in order to take potential anticipation effects into account.

References

Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2004). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80, 123–129.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion (1st ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Augurzky, B., Reichert, A., & Tauchmann, H. (2013). Self-perceived job insecurity and the demand for medical rehabilitation: does fear of unemployment reduce health care utilization? Health economics. forthcoming.

Autor, D. H., & Duggan, M. G. (2003). The rise in the disability rolls and the decline in unemployment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 157–205.

Baicker, K., & Goldman, D. (2011). Patient cost-sharing and healthcare spending growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(2), 47–68.

Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Sendhil, M. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 249–275.

Buntin M. B., Escarce J. J., Hoverman C., Paddock S. M., Totten M. E., & Wynn B. O. (2005). Effects of payment changes on trends in access to post-acute care. Technical report, RAND Corporation. http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR259, last accessed on February 27, 2012.

Burkhauser, R. V., & Daly, M. C. (2011). The declining work and welfare of people with disabilities: What went wrong and a strategy for change (1st ed.). Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute.

Chandra, A., Gruber, J., & McKnight, R. (2010). Patient cost-sharing, hospitalization offsets, and the design of optimal health insurance for the elderly. American Economic Review, 100(1), 193–213.

Chiappori, P.-A., Durand, F., & Geoffard, P.-Y. (1998). Moral hazard and the demand for physician services: First lessons from a natural experiment. European Economic Review, 42, 499–511.

Cockx, B., & Brasseur, C. (2003). The demand for physician services: Evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Health Economics, 22(6), 881–913.

Congressional Research Service (2006). Medicare payment issues affecting Inpatient Rehabilitation Facilities (IRFs). CRS Report for Congress. http://www.policyarchive.org/handle/10207/bitstreams/2254.pdf, last accessed on February 27, 2012.

Crown, W. H., Berndt, E. R., Baser, O., Finkelstein, S. N., Witt, W. P., Maguire, J., et al. (2004). Benefit plan design and prescription drug utilization among asthmatics: Do patient copayments matter? Forum for Health Economics & Policy, 7(1), 1–5.

Donald, S. G., & Lang, K. (2007). Inference with difference-in-differences and other panel data. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(2), 221–233.

Frölich, M., Heshmati, A., & Lechner, M. (2004). A microeconometric evaluation of rehabilitation of long-term sickness in Sweden. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 19(3), 375–396.

Gaynor M., Li J., & Vogt W. B. (2007). Substitution, spending offsets, and prescription drug benefit design. Forum for Health Economics & Policy, 10(2), article 4.

Gerfin, M., & Schellhorn, M. (2006). Nonparametric bounds on the effect of deductibles in health care insurance on doctor visits–Swiss evidence. Health Economics, 15(9), 1011–1020.

German Federal Statistical Office (2013). Federal health monitoring. http://www.gbe-bund.de, last accessed on October 11, 2013.

Glied, S., & Zivin, J. G. (2002). How do doctors behave when some (but not all) of their patients are in managed care? Journal of Health Economics, 21(2), 337–353.

Goldman, D. P., Joyce, G. F., Escarce, J. J., Pace, J. E., Solomon, M. D., Laouri, M., et al. (2004). Pharmacy benefits and the use of drugs by the chronically ill. Journal of the American Medical Association, 291(19), 2344–2350.

Goldman, Dana P, Joyce, Geoffrey F, & Zheng, Yuhui. (2007). Prescription drug cost sharing. Journal of the American Medical Association, 298(1), 61–69.