Abstract

The present research tested the hypotheses that (a) working-class students have fewer friends at university than middle-class students and (b) this social class difference occurs because working-class students tend to be older than middle-class students. A sample of 376 first-year undergraduate students from an Australian university completed an online survey that contained measures of social class and age as well as quality and quantity of actual and desired friendship at university. Consistent with predictions, age differences significantly mediated social class differences in friendship. The discussion focuses on potential policy implications for improving working-class students’ friendships at university in order to improve their transition and retention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social integration provides an important source of informational and emotional support at university (Karp 2011; Rubin 2012b; Thomas 2012), and this support is beneficial to students’ transition and retention (Allen et al. 2008; McConnell 2000; Napoli and Wortman 1996; Robbins et al. 2004; Tinto 1975, p. 109; Thomas 2012; Tripp 1997; for reviews, see Karp 2011; Pascarella and Terenzini 1991, 2005). In particular, the development of friendships during the first semester of university can form a crucial base for building future social networks that facilitate the transition to university and promote student persistence (Thomas 2012; Yorke and Thomas 2003). For example, Thomas (2012) found that students who made friends at a welcome lunch were more likely to continue with their program than those who did not attend the lunch. Student feedback indicated that this initial social contact often developed into deeper long-term friendships.

Greater social integration at university also predicts better learning, cognitive growth, critical thinking, personal and moral development, confidence, academic self-efficacy, and academic performance (e.g., Allen et al. 2008; Brooman and Darwent 2014; Thomas 2012; for reviews, see Gellin 2003; Hernandez et al. 1999; Karp 2011; McConnell 2000; Moore et al. 1998; Pascarella and Terenzini 1991, 2005; Robbins et al. 2004; Terenzini et al. 1999). Social integration also leads to changes in students’ attitudes, articulateness, dress sense, and sociability, which can increase their job prospects (Moore et al. 1998, p. 8; Stuber 2009, p. 880). Finally, there is some evidence that social integration at university is positively related to mental health (Hefner and Eisenberg 2009).

However, not all students integrate well at university. In particular, a recent meta-analysis of 35 studies and over 62,000 students found that working-class students were less socially integrated than middle-class students, and that they felt less of a sense of belonging at university (Rubin 2012a). The present research follows up on this previous work by investigating social class differences in students’ friendship as a key aspect of social integration at university.

Social class differences in friendship at university

The present research tested the hypothesis that working-class students have fewer friends at university than middle-class students. There is already some limited support for this hypothesis. Rubin (2012a) found that working-class students engaged in less informal social integration than middle-class students, where informal social integration included number of friends on campus, dates, parties, and non-classroom conversations. However, the size of the observed effect for this social class difference was quite small (r = .05), which casts doubt on its practical significance.

The strongest evidence in this area comes from Fischer (2007), who found correlations of around .08 between social class (measured in terms of parental education and income) and friendship (measured as number of on-campus close friends and hours per week spent partying and with friends). Other studies have found more mixed results (Martinez et al. 2009; Sandler 2000).

It is important to investigate social class differences in students’ friendship because they help to explain social class differences in academic experiences. For example, social class differences in campus social life are related to social class differences in satisfaction with university experience (Martin 2012; Soria et al. 2013). In addition, students’ sense of belonging at college mediates the relation between social class and academic adjustment (Ostrove and Long 2007). Finally, social integration (loneliness and school attachment) mediates the relation between demographic marginalization (based on socioeconomic status and ethnicity) and educational performance and attainment among school children (Benner and Wang 2014). Hence, working-class students’ relative deficit in friendships at university is important because it may hold the key to reducing their deficits in satisfaction, adjustment, and performance.

The need to investigate social class differences of this type has become particularly pressing with recent efforts to increase the proportion of working-class students in higher education. For example, the White House (2014) recently released a report about increasing college opportunities for low-income students. Similarly, Australia’s (2015) Higher Education Participation Programme aims to ensure that people from low socioeconomic backgrounds have the opportunity to study at university.

Do age differences explain social class differences in university friendship?

The present research also aimed to extend our understanding of social class differences in university friendship effect by investigating a potential explanation for these differences. Following Rubin (2012a), we hypothesized that working-class students tend to have fewer friends at university than middle-class students because they tend to be older than middle-class students, and older students have less time to develop friendships. A number of lines of evidence are consistent with this age difference explanation.

First, working-class students tend to be older than middle-class students (Inman and Mayes 1999; Kasworm and Pike 1994; Kuh and Ardaiolo 1979; Nuñez and Cuccaro-Alamin 1998; Shields 2002; Terenzini et al. 1996). Social class may be negatively related to age because a lack of financial capital deters working-class school leavers from commencing university immediately and, instead, motivates them to enter the workforce and/or study for vocational qualifications (James 2002). It is only after they have accrued sufficient financial capital over a number of years that they feel able to commence university.

Second, students’ age is negatively related to their social integration at university, with younger students integrating more than older students (Bean and Metzner 1985; Brooks and DuBois 1995; Chapman and Pascarella 1983; Kasworm and Pike 1994; Lundberg 2003; Napoli and Wortman 1998; Stage 1988; for a review, see Kasworm and Pike 1994).

Third, age may be negatively related to social integration because older students have more external commitments than younger students, such as childcare and employment, and consequently, they have less time to develop social relationships. Consistent with this reasoning, there is some evidence that older people have less time to engage in social activities due to their other commitments (Campbell and Lee 1992, p. 1083–1084; Hartup and Stevens 1997; Nuñez and Cuccaro-Alamin 1998, footnote 18; for a brief review, see Bean and Metzner 1985, p. 508).

Considering these various relations together, it is possible that working-class students have fewer friends at university than middle-class students because they are older than middle-class students. In other words, age differences may account for, or mediate, social class differences in friendship. Although previous evidence forms a firm foundation for predicting this mediation effect, it remains a novel and previously untested hypothesis. It is important to test this age difference hypothesis in order to establish whether social class differences in university friendship occur separate from or as a result of age differences in university friendship. It is only in the latter case that interventions that aim to improve working-class students’ university friendships will need to take age differences into consideration.

Methods

Participants

Participants were undergraduate students who were enrolled in first-year psychology courses at a non-metropolitan university located in New South Wales, Australia. The study received approval from the university’s Human Research Ethics Committee.

The university was a 3- and 4-year public university with around 37,500 enrolments. It was a multi-campus, non-elite university that did not specialize in external or mixed-mode education. Based on institutional data, 27.32 % of the domestic students had a low socioeconomic status.

The sample consisted of 376 students. Of these, only 19.15 % were men (72 men and 304 women). Although this gender imbalance is typical for psychology courses, it was not representative of the university population (44.83 % men). However, in his meta-analysis, Rubin (2012a) found no evidence that gender moderates the size of the relation between social class and social integration. Hence, we did not view this sampling bias as a major threat to the validity of our conclusions.

The sample had a mean age of 22.11 years (SD = 6.09) and ranged from 17 to 53 years. The mean age was below the institutional mean of 25.08 years, reflecting the fact that we sampled only first-year students. However, friendship and social integration among first-year students is of particular interest to researchers because they are key predictors of subsequent retention and academic performance (e.g., Thomas 2012; Yorke and Thomas 2003). Hence, again, we viewed this sampling bias as being acceptable.

Based on the subjective measure of social class (see below for details), 28.72 % of participants described themselves as poor or working-class, 10.64 % as lower middle-class, 33.51 % as middle-class, and 19.68 % as upper middle-class. The remaining participants indicated that they were upper class (.80 %) or that they did not know their social class (6.65 %). Hence, our participants were representative of the university population in terms of their social class.

Procedure and measures

Students completed an anonymous online self-report survey that was titled “Making Friends at Uni.” The survey was available to students over a 4-month period that spanned all of Semester 1 and the first part of Semester 2. Students took part on a voluntary basis, and they received course credit in exchange for their participation. The modal time for students to complete the survey was 9 min.

Friendship measures

In the survey, students estimated the number of friends who were important to their identity and sense of self. Close friends measures such as this reduce ambiguity about what constitutes a “friend,” and they have been used in previous research in this area (e.g., Chapman and Pascarella 1983; Sandler 2000).

We also measured the quality of friendships at university (e.g., Berger and Milem 1999; Beil et al. 1999; Brooman and Darwent, 2014; Langhout et al. 2009; Martinez et al. 2009; Sandler 2000). Specifically, we designed a Relevance of Friends to Identity scale to assess the extent to which students perceived their friends to be an important part of their self-image and personal identity. The scale consisted of six items. Three were created from Cross et al. (2000) Relational Interdependent Self-Construal scale, and three were created specifically for the present study. Example items are “my friends are an important part of my self-image” and “my friends are an important part of who I am.” Students responded using a 7-point Likert-type scale that was anchored strongly disagree and strongly agree.

We complemented our measures of current levels friendship with three measures of desired levels of friendship. We reasoned that this aspect of friendship would be particularly relevant to first-year undergraduate students.

First, students estimated the number of new friends that they wanted to make in the next year at university. For comparative purposes, we also asked students to estimate the number of new friends that they wanted to make in the next year outside university.

Second, students completed an adapted version of Buote et al.’s (2007) ten-item Openness to Friendships scale. We made minor changes to the wording of half of the items in this scale in order to make them relevant to current university students rather than prospective university students. Students responded using a 7-point Likert-type scale that was anchored strongly disagree and strongly agree.

Finally, students completed Paul and Kelleher’s (1995) 4-item New Friends Concern scale. Students responded using a 7-point Likert-type scale that was anchored not concerned at all and extremely concerned. We randomized the order of presentation of the above friendship measures and the items within each measure for each student.

Measures of social class

We included measures of social class at the end of the survey in order to avoid cuing students to the relevance of this variable prior to their reports of friendship (Langhout et al. 2009). Education level is the most widely used proxy for social class (e.g., Martin 2012; Martinez et al. 2009; Sirin 2005). In the present research, we asked students to indicate their mother’s and father’s highest education levels using the following categories: no formal schooling, preschool, primary school (years 1–7), secondary or high school (years 7–10), senior secondary school (years 11 and 12), technical and further education (TAFE), university—undergraduate degree (bachelor degree), university—postgraduate degree (masters or PhD), and don’t know.

Students also completed three subjective measures of social class (e.g., Ostrove and Long 2007; Soria et al. 2013; for a review, see Rubin et al. 2014). They indicated the social class that they felt best described themselves, their mother, and their father using the following categories: poor, working class, lower middle-class, middle-class, upper middle-class, upper class, and don’t know.

Finally, students provided a subjective indication of their family income during childhood (e.g., Gofen 2009; Griskevicius et al. 2011): well below average, slightly below average, average, slightly above average, well above average, and don’t know. Students also indicated their gender and their age to the nearest year.

Psychometric analyses

The data for students’ age and number of friends were not normally distributed. In order to produce more normal distributions, we transformed these variables by computing their log 10 values after adding 1 to the number of friends variables (it is not possible to log 10 transform values of 0). These transformations resulted in more normal distributions.

The Relevance of Friends to Identity scale, Openness to Friendships scale, and New Friends Concern scale all had good internal reliabilities (αs = .78, .89, and .81, respectively). Consequently, we computed mean values for each of these scales.

After conversion to z scores, the six measures of social class (mother’s education, father’s education, subjective social class of self, mother, and father, and subjective family income) had a good mean correlation with one another (r = .36). Furthermore, these measures combined together to form a reliable scale (Cronbach’s α = .77). Consequently, we computed the mean of these z scores in order to provide a more reliable, valid, and powerful index of social class than any of the individual measures.

Results

Zero-order correlations

The zero-order correlations between social class, age, and the friendship variables are presented in Table 1.Footnote 1

As can be seen in Table 1, social class and age showed significant, small-to-medium-sized relations with each of the friendship variables. Hence, the higher students’ social class and the younger their age, the more friends they had who were important to their identity, the more relevant they felt that their friends were to their identity, the more friends they wanted to make at university and outside university, and the more open and concerned they were about making friends. It is important to note that students’ age had a significant, medium-sized, negative relation with social class.Footnote 2

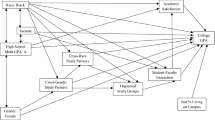

Mediation analyses

The pattern of results in Table 1 suggests that students’ age may mediate the relations between social class and friendship. To provide a powerful test of this mediation effect, we used Hayes’ (2013) bootstrapping method. This method examined the relations between social class (predictor variable), age (mediator variable), and each of the six indexes of friendship (outcome variables). We used 5,000 iterations of the bootstrapping analysis to obtain the bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap confidence intervals. The results of these analyses are presented in Table 2.

Looking at the indirect effect columns of Table 2, it can be seen that, consistent with predictions, students’ age acted as a significant mediator in all cases (i.e., none of the 95 % confidence intervals included 0). Full mediation effects were obtained in four of the six tests. In other words, the originally significant effect of social class on the friendship variable (see the total effect columns) became nonsignificant after age was included in the model (see the direct effect columns). A partial mediation effects was obtained in the case of relevance of friends to identity. In other words, the originally significant effect of social class on this variable remained significant after age was included in the model.

Note that the total effect of social class on openness to make new friends was only approaching the conventional level of significance (p = .066). Although it is not necessary for a total effect to be significant in order to confirm a significant mediation effect (Hayes 2013), this marginally significant effect casts doubt on the robustness of the relation between social class and openness to make friends.

Additional analyses replicated our key mediation results for each individual measure of social class. In addition, tests of reverse mediation showed that, in general, age mediated the effect of social class on friendship rather than social class mediated the effect of age of friendship. Finally, there were no significant gender differences in social class, age, or any of the friendship variables (ps ≥ .133).

Discussion

Social class differences in friendship at university

Consistent with preliminary findings (Fischer 2007; Rubin 2012a), we found clear evidence of social class differences in friendship at university. Compared with middle-class students, working-class students reported having fewer identity-relevant friends and regarded the friends that they did have as being less relevant to their identity. In addition, they were less concerned and less open toward making friends.

The social class–friendship effect that we observed was small-to-medium in size (mean r = .14) but almost twice the size of the largest effect that has been found in previous research (Fischer 2007; r ~ .08). This difference in effect size may be due to a number of factors, including the specific institutional and/or cultural climate that we investigated. It may also be due to the sensitivity in measurement gained by using multiple, articulated measures of social class and friendship in the present research (Rubin 2012a). In either case, the present research demonstrates that the social class–friendship effect can have practical significance and, consequently, that it deserves greater attention from university administrators.

Age differences explain social class differences in university friendship

The present research advances our understanding of the social class–friendship effect by demonstrating the intervening role of age differences. Mediation tests showed that working-class students tended to have a lower quality and quantity of actual and desired friendships than middle-class students because they tended to be older than middle-class students. This novel finding provides the first empirical evidence in support of the hypothesis that age differences explain social class differences in students’ friendships at university.

To be clear, our evidence does not indicate that age is in any way primary to or more important than other factors that affect friendship at university, including social class. Age is one of several variables that influence university friendship, and the relative importance of each variable is likely to depend on numerous contextual factors. Hence, universities should consider a wide range of explanatory variables when considering social class differences in friendship, and we discuss some of these variables in the next section. Our mediation evidence only indicates that age differences can help to explain social class differences in university friendship and that, consequently, age is a factor that should be taken into account when considering interventions that are intended to reduce such differences.

Notably, working-class students wanted to make fewer friends than middle-class students outside university as well as inside university. Hence, it is possible that social class differences in friendship at university may reflect broader social class differences in society at large. Importantly, however, this broader effect is unlikely to be explicable in terms of age differences: Working-class people are not generally older than middle-class people in the general population; this age difference is restricted to university students. Consequently, although broader social class differences in friendship may contribute to the social class–friendship effect at university, they are unlikely to be related to age differences.

Limitations and directions for future research

Our research has two key limitations. First, the research used a cross-sectional correlational research design. Consequently, we are unable to make definitive statements about the causal direction of the relations that we identified. Having said this, we can be relatively confident about the causal direction of the relations between (a) social class and friendship and (b) age and friendship. Due to their relatively intransient nature, social class and age are much more likely to cause differences in friendship than vice versa. In other words, it is unlikely that differences in the quality and quantity of students’ friendships caused differences in their social class or age. Nonetheless, future research in this area should consider the use of longitudinal research designs in order to determine the extent to which social class influences age of entry into university.

Second, our finding that age tended to fully mediate the effect of social class on friendship does not preclude the potential influence of additional variables in this relation (Hayes 2013, p. 171). As Rubin (2012a) suggested, other potential mediators may include accommodation arrangements, campus attendance, finances for socializing, time spent studying, ethnicity, minority group status, and perceived interpersonal similarity. For example, living on-campus versus off-campus may mediate the social class–friendship relation because working-class students are less likely to live on campus than middle-class students (Nuñez and Cuccaro-Alamin 1998; Pike and Kuh 2005), and off-campus accommodation limits students’ opportunities for developing friendships (Bean and Metzner 1985, p. 508; Brooman and Darwent, 2014; Holdsworth 2006; Thomas 2012; Turley and Wodtke 2010). To take another example, perceived interpersonal similarity in socioeconomic status predicts friendships among university students (Mayer and Puller 2008). Hence, working-class students may not integrate well with middle-class students because they feel that they do not have much in common with this majority group (Lynch and O’Riordan 1998, pp. 461–462). Future research should investigate these additional explanations of the social class–friendship relation.

Implications

The practical significance of the proposed research lies in its potential to inform the development of policies and interventions that increase working-class students’ social inclusion at university and, in turn, improve their transition, persistence, performance, and satisfaction. Compared with middle-class students, working-class students are less likely to be academically engaged, obtain good grades, develop intellectually, stay enrolled in their courses, and complete their degrees (Allen et al. 2008; Arulampalam et al. 2005; Attewell et al. 2011; Inman and Mayes 1999; Ishitani 2006; Martinez et al. 2009; Nuñez and Cuccaro-Alamin 1998; Pike and Kuh 2005; Pittman and Richmond 2007; Riehl 1994; Robbins et al. 2004, 2006; Tinto 1975). Given that social integration is positively related to academic outcomes and retention (e.g., Allen et al. 2008; Brooman and Darwent 2014; Thomas 2012; for reviews, see Karp 2011; McConnell 2000; Napoli and Wortman 1996; Pascarella and Terenzini 1991, 2005; Robbins et al. 2004; Tinto 1975; Tripp 1997), a potentially important method of improving working-class students’ academic outcomes is to improve the quality and quantity of their university friendships (Rubin 2012b). Consistent with this reasoning, there is evidence that social integration mediates the relation between social class and academic performance and adjustment (Benner and Wang 2014; Ostrove and Long 2007).

The present research findings suggest that policies and strategies that aim to increase working-class students’ university friendship should take students’ age into account. To illustrate, we consider how our findings might inform interventions that aim to improve transition and retention.

The transition to university can be more difficult for working-class students than for middle-class students because it involves a break with family tradition and a potential change in social class identity. One approach to improving working-class students’ transition and subsequent retention is to attract them to live in on-campus accommodation rather than in their family homes. In general, this on-campus approach improves students’ social integration and engagement at university (e.g., Bean and Metzner 1985, p. 508; Brooman and Darwent 2014; Holdsworth 2006; Thomas 2012; Turley and Wodtke 2010). Indeed, Holdsworth (2006) found that living on campus versus at home makes a significant positive impact on students’ friendships and social life even after controlling for age and social class. Hence, on-campus accommodation is a powerful method of improving students’ friendships and social integration, and some researchers have gone so far as to recommend that on-campus accommodation should be mandatory for first- and second-year students (Braxton and McClendon 2001, p. 60).

However, the present research findings raise concerns about the feasibility of traditional on-campus accommodation for improving the transition and retention of working-class students. In particular, the present research shows that working-class students have a lower quality and quantity of friendships than middle-class students because they are older than middle-class students. Older working-class students are more likely to have spouses and young children than younger middle-class students. Consequently, older working-class students are more likely to prefer to live at their family home than in traditional student accommodation (e.g., Nuñez and Cuccaro-Alamin 1998; Pike and Kuh 2005). A key implication of the present research is that arrangements for on-campus accommodation should take into account students’ social class, age, and concomitant family commitments. In particular, universities should invest in affordable on-campus family accommodation and campus-based childcare facilities (for similar suggestions in relation to international students and single-mother students, see Poyrazli and Grahame 2007; Yakaboski 2010). These arrangements may encourage more working-class students to live on campus and allow them to reap the associated benefits vis-à-vis university friendships and social integration.

Transition and retention can also be improved through more direct and intrusive methods of promoting university friendships. As Thomas (2012) recommended, “academic staff can promote social integration through induction activities, collaborative learning and teaching, field trips, opt-out peer mentoring and staff-organized social events” (p. 48). Again, however, the message from the present research is that these activities need to be age-appropriate and held at suitable times of the day in order to attract older working-class students, who have work and/or family commitments (Yakaboski 2010). In this respect, online social networking may be a particularly useful method of developing friendships among older working-class students because it can be undertaken at low cost and at any time (for recent examples of online approaches that have improved student transition, see DeAndrea et al. 2012; Madge et al. 2009).

Finally, by investigating desired, as well as current, levels of friendship, the present research also highlights the role of students’ motivations in the social class–friendship relation. Working-class students had not only fewer friends than middle-class students but also less desire and concern about making new friends. Hence, simply providing opportunities for friendship building is unlikely to be sufficient. Universities also need to motivate older working-class students to participate in social life at university, perhaps through the use of information campaigns that highlight the informational and emotional support that is provided by university friends.

Notes

Social class and age also had significant curvilinear (quadratic) relations with most of the outcome variables. In the case of social class, initial increases from working-class to middle-class might be expected to result in increases in university friendships. However, as social class becomes even higher, and students start to become part of a minority of upper-class students, the opportunities for friendship with similar others may decrease. In the case of age, initial increases may lead to decreases in friendship. However, as age increases further, and students become less likely to have childcare commitments, there are likely to be more, rather than less, opportunities for developing friendships at university.

References

Allen, J., Robbins, S. B., Casillas, A., & Oh, I. S. (2008). Third-year college retention and transfer: Effects of academic performance, motivation, and social connectedness. Research in Higher Education, 49, 647–664. doi:10.1007/s11162-008-9098-3

Arulampalam, W., Naylor, R. A., & Smith, J. P. (2005). Effects of in-class variation and student rank on the probability of withdrawal: Cross-section and time-series analysis for UK university students. Economics of Education Review, 24, 251–262. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2004.05.007

Attewell, P., Heil, S., & Reisel, L. (2011). Competing explanations of undergraduate noncompletion. American Educational Research Journal, 48, 536–559. doi:10.3102/0002831210392018

Bean, J. P., & Metzner, B. S. (1985). A conceptual model of nontraditional undergraduate student attrition. Review of Educational Research, 55, 485–540. doi:10.2307/1170245

Beil, C., Reisen, C. A., & Zea, M. C. (1999). A longitudinal study of the effects of academic and social integration and commitment on retention. NASPA Journal, 37, 376–385. doi:10.2202/1949-6605.1094

Benner, A. D., & Wang, Y. (2014). Demographic marginalization, social integration, and adolescents’ educational success. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 1611–1627. doi:10.1007/s10964-014-0151-6

Berger, J. B., & Milem, J. F. (1999). The role of student involvement and perceptions of integration in a causal model of student persistence. Research in Higher Education, 40, 641–664. doi:10.1023/A:1018708813711

Braxton, J. M., & McClendon, S. A. (2001). The fostering of social integration and retention through institutional practice. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 3, 57–71. doi:10.2190/RGXJ-U08C-06VB-JK7D

Brooks, J. H., & DuBois, D. L. (1995). Individual and environmental predictors of adjustment during the first year of college. Journal of College Student Development, 36, 347–360.

Brooman, S., & Darwent, S. (2014). Measuring the beginning: A quantitative study of the transition to higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 39, 1523–1541. doi:10.1080/03075079.2013.801428

Buote, V. M., Pancer, S. M., Pratt, M. W., Adams, G., Birnie-Lefcovitch, S., Polivy, J., & Wintre, M. G. (2007). The importance of friends: Friendship and adjustment among 1st-year university students. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22, 665–689. doi:10.1177/0743558407306344

Campbell, K. E., & Lee, B. A. (1992). Sources of personal neighbor networks: Social integration, need, or time? Social Forces, 70, 1077–1100. doi:10.1093/sf/70.4.1077

Chapman, D. W., & Pascarella, E. T. (1983). Predictors of academic and social integration of college students. Research in Higher Education, 19, 295–322. doi:10.1007/BF00976509

Cross, S. E., Bacon, P. L., & Morris, M. L. (2000). The relational-interdependent self-construal and relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 791–808. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.791

DeAndrea, D. C., Ellison, N. B., LaRose, R., Steinfield, C., & Fiore, A. (2012). Serious social media: On the use of social media for improving students’ adjustment to college. The Internet and Higher Education, 15, 15–23. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.05.009

Fischer, M. J. (2007). Settling into campus life: Differences by race/ethnicity in college involvement and outcomes. Journal of Higher Education, 78, 125–161. doi:10.1353/jhe.2007.0009

Gellin, A. (2003). The effect of undergraduate student involvement on critical thinking: A meta-analysis of the literature 1991–2000. Journal of College Student Development, 44, 746–762. doi:10.1353/csd.2003.0066

Gofen, A. (2009). Family capital: How first-generation higher education students break the intergenerational cycle. Family Relations, 58, 104–120. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00538.x

Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J. M., Delton, A. W., & Robertson, T. E. (2011). The influence of mortality and socioeconomic status on risk and delayed rewards: A life history theory approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 1015–1026. doi:10.1037/a0022403

Hartup, W. W., & Stevens, N. (1997). Friendships and adaptation in the life course. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 355–370. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.355

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Hefner, J., & Eisenberg, D. (2009). Social support and mental health among college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79, 491–499. doi:10.1037/a0016918

Hernandez, K., Hogan, S., Hathaway, C., & Lovell, C. D. (1999). Analysis of the literature on the impact of student involvement on student development and learning: More questions than answers? NASPA Journal, 36, 184–197. doi:10.2202/1949-6605.1082

Holdsworth, C. (2006). ‘Don’t you think you’re missing out, living at home?’ Student experiences and residential transitions. The Sociological Review, 54, 495–519. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2006.00627.x

Inman, W. E., & Mayes, L. D. (1999). The importance of being first: Unique characteristics of first-generation community college students. Community College Review, 26, 3–22. doi:10.1177/009155219902600402

Ishitani, T. T. (2006). Studying attrition and degree completion behavior among first-generation college students in the United States. Journal of Higher Education, 77, 860–886. doi:10.1353/jhe.2006.0042

James, R. (2002). Socioeconomic background and higher education participation: An analysis of school students’ aspirations and expectations. Canberra, ACT, Australia: Evaluations and Investigations Programme of the Department of Education, Science and Training. Retrieved from http://www.dest.gov.au/archive/highered/eippubs/eip02_5/eip02_5.pdf

Karp, M. M. (2011). Toward a new understanding of non-academic student support: four mechanisms encouraging positive student outcomes in the community college. CCRC Working Paper No. 28. Assessment of Evidence Series. Community College Research Center, Columbia University.

Kasworm, C. E., & Pike, G. R. (1994). Adult undergraduate students: Evaluating the appropriateness of a traditional model of academic performance. Research in Higher Education, 35, 689–710. doi:10.1007/BF02497082

Kuh, G. D., & Ardaiolo, F. P. (1979). Adult learners and traditional-age freshmen: Comparing the “new” pool with the “old” pool of students. Research in Higher Education, 10, 207–219. doi:10.1007/BF00976265

Langhout, R. D., Drake, P., & Rosselli, F. (2009). Classism in the university setting: Examining student antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 2, 166–181. doi:10.1037/a0016209

Lundberg, C. A. (2003). The influence of time-limitations, faculty, and peer relationships on adult student learning: A causal model. Journal of Higher Education, 74, 665–688. doi:10.1353/jhe.2003.0045

Lynch, K., & O’Riordan, C. (1998). Inequality in higher education: A study of class barriers. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 19, 445–478.

Madge, C., Meek, J., Wellens, J., & Hooley, T. (2009). Facebook, social integration and informal learning at university: ‘It is more for socialising and talking to friends about work than for actually doing work’. Learning, Media and Technology, 34, 141–155. doi:10.1080/17439880902923606

Martin, N. D. (2012). The privilege of ease: Social class and campus life at highly selective, private universities. Research in Higher Education, 53, 426–452. doi:10.1007/s11162-011-9234-3

Martinez, J. A., Sher, K. J., Krull, J. L., & Wood, P. K. (2009). Blue-collar scholars?: Mediators and moderators of university attrition in first-generation college students. Journal of College Student Development, 50, 87–103. doi:10.1353/csd.0.0053

Mayer, A., & Puller, S. L. (2008). The old boy (and girl) network: Social network formation on university campuses. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 329–347. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2007.09.001

McConnell, P. J. (2000). ERIC review: What community colleges should do to assist first-generation students. Community College Review, 28, 75–87. doi:10.1177/009155210002800305

Moore, J., Lovell, C. D., McGann, T., & Wyrick, J. (1998). Why involvement matters: A review of research on student involvement in the collegiate setting. College Student Affairs Journal, 17, 4–17.

Napoli, A. R., & Wortman, P. M. (1996). A meta-analysis of the impact of academic and social integration on persistence of community college students. Journal of Applied Research in the Community College, 4, 5–21.

Napoli, A. R., & Wortman, P. M. (1998). Psychosocial factors related to retention and early departure of two-year community college students. Research in Higher Education, 39, 419–455. doi:10.1023/A:1018789320129

Nuñez, A-.M., & Cuccaro-Alamin, S. (1998). First-generation students: Undergraduates whose parents never enrolled in postsecondary education (Report No. NCES 98-082). Washington, DC: US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs98/98082.pdf

Ostrove, J. M., & Long, S. M. (2007). Social class and belonging: Implications for college adjustment. Review of Higher Education, 30, 363–389.

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (1991). How college affects students: Findings and insights from twenty years of research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects students volume 2: A third decade of research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Paul, E. L., & Kelleher, M. (1995). Precollege concerns about losing and making friends in college: Implications for friendship satisfaction and self-esteem during the college transition. Journal of College Student Development, 36, 513–521.

Pike, G. R., & Kuh, G. D. (2005). First- and second-generation college students: A comparison of their engagement and intellectual development. Journal of Higher Education, 76, 276–300.

Pittman, L. D., & Richmond, A. (2007). Academic and psychological functioning in late adolescence: The importance of school belonging. Journal of Experimental Education, 75, 270–290. doi:10.3200/JEXE.75.4.270-292

Poyrazli, S., & Grahame, K. M. (2007). Barriers to adjustment: Needs of international students within a semi-urban campus community. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 34, 28–45.

Riehl, R. J. (1994). The academic preparation, aspirations, and first-year performance of first-generation students. College and University, 70, 14–19.

Robbins, S. B., Allen, J., Casillas, A., Peterson, C. H., & Le, H. (2006). Unraveling the differential effects of motivation and skills, social, and self-management measures from traditional predictors of college outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 598–616. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.98.3.598

Robbins, S. B., Le, H., Davis, D., Lauver, K., Langley, R., & Carlstrom, A. (2004). Do psychosocial and study skill factors predict college outcomes? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 261–288. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.261

Rubin, M. (2012a). Social class differences in social integration among students in higher education: A meta analysis and recommendations for future research. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 5, 22–38. doi:10.1037/a0026162

Rubin, M. (2012b). Working-class students need more friends at university: A cautionary note for Australia’s higher education equity initiative. Higher Education Research and Development, 31, 431–433. doi:10.1080/07294360.2012.689246

Rubin, M., Denson, N., Kilpatrick, S., Matthews, K. E., Stehlik, T., & Zyngier, D. (2014). “I am working-class”: Subjective self-definition as a missing measure of social class and socioeconomic status in higher education research. Educational Researcher, 43, 196–200. doi:10.3102/0013189X14528373

Sandler, M. E. (2000). Career decision-making self-efficacy, perceived stress, and an integrated model of student persistence: A structural model of finances, attitudes, behavior, and career development. Research in Higher Education, 41, 537–580. doi:10.1023/A:1007032525530

Shields, N. (2002). Anticipatory socialization, adjustment to university life, and perceived stress: Generational and sibling stress. Social Psychology of Education, 5, 365–392. doi:10.1023/A:1020929822361

Sirin, S. R. (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 75, 417–453. doi:10.3102/00346543075003417

Soria, K. M., Stebleton, M. J., & Huesman, R. L. (2013). Class counts: Exploring differences in academic and social integration between working-class and middle/upper-class students at large, public research universities. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory and Practice, 15, 215–242. doi:10.2190/CS.15.2.e

Stage, F. K. (1988). University attrition: LISREL with logistic regression for the persistence criterion. Research in Higher Education, 29, 343–357. doi:10.1007/BF00992775

Stuber, J. M. (2009). Class, culture, and participation in the collegiate extra-curriculum. Sociological Forum, 24, 877–900. doi:10.1111/j.1573-7861.2009.01140.x

Terenzini, P. T., Pascarella, E. T., & Blimling, G. S. (1999). Students’ out-of-class experiences and their influence on learning and cognitive development: A literature review. Journal of College Student Development, 40, 610–623.

Terenzini, P. T., Springer, L., Yaeger, P. M., Pascarella, E. T., & Nora, A. (1996). First-generation college students: Characteristics, experiences, and cognitive development. Research in Higher Education, 37, 1–22. doi:10.1007/BF01680039

The White House. (2014). Increasing college opportunity for low-income students: Promising models and a call to action. The Executive Office of the President. Retrieved from http://1.usa.gov/1dagqsh

Thomas, L. (2012). Building student engagement and belonging in Higher Education at a time of change: Final report from the What Works? Student Retention & Success programme. Paul Hamlyn Foundation. Retrieved from: http://www-new2.heacademy.ac.uk/assets/documents/what-works-student-retention/What_works_final_report.pdf

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45, 89–125. doi:10.3102/00346543045001089

Tripp, R. (1997). Greek organizations and student development: A review of the research. College Student Affairs Journal, 16, 31–39.

Turley, R. N. L., & Wodtke, G. (2010). College residence and academic performance: Who benefits from living on campus? Urban Education, 45, 506–532. doi:10.1177/0042085910372351

Yakaboski, T. (2010). Going at it alone: Single-mother undergraduate’s experiences. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 47, 456–474. doi:10.2202/1949-6605.6185

Yorke, M., & Thomas, L. (2003). Improving the retention of students from lower socio-economic groups. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 25, 63–74. doi:10.1080/13600800305737

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the following people for their helpful suggestions regarding this research: Belinda Apostolovski, Joshua Ayscough, Jessica Bradley, Edward Broadbent, Michelle Downey, Madeleine Drew, Yasmina Dzenanovic, Margaret Ellis, Kate Ismay, Buruschke Kahts, Tracy Lawrence, Rhianna Mott, and Phillipa Newham.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rubin, M., Wright, C.L. Age differences explain social class differences in students’ friendship at university: implications for transition and retention. High Educ 70, 427–439 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9844-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9844-8