Abstract

New public governance emphasises less state, more market and more hierarchy as the cornerstones for effective steering of higher education institutions. Based on an explorative analysis of qualitative and quantitative data of fourteen German and European economics departments, we investigate the steering effects of six new public management instruments in the years 2001 and 2002 on subsequent placement success of PhD graduates. Using crisp set Qualitative Comparative Analysis to analyse the data, our results deliver strong support for the positive effects of competition for resources and the varying effects of hierarchy on PhD education. Governance of successful departments is characterised by two solutions: transparency over academic achievements as one single success factor in each solution or a combination of additional funding based on national competitive performance with either no public policy regulations for departments or no university regulations for departments. Governance of unsuccessful departments is characterised by one solution: university regulations for departments or a combination of no additional funding based on national competitive performance and no transparency over academic achievements. Our results strengthen the strong impact of selected competitive mechanisms as an effective governance instrument and the partially detrimental effects of state regulations. University regulations turn out to be successful if they increase transparency over academic achievements by faculty members. Success is unlikely if those rules intervene into PhD education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the early 1990s, almost all European countries viewed their doctoral programs as falling short of the primordial objective of doctoral education: qualifying young academics to do original research on their own. Given this diagnosis, initiatives were taken in many countries to remedy this dismal situation by applying new governance regimes to PhD education (Sadlak 2004) and the university system in general (Leisyte et al. 2006).

Although the changes in the doctoral education of many European countries led to considerable success, several countries, among them Germany, have done little to modify their PhD education (Wissenschaftsrat 2002; DFG 2003). The “German Research Foundation” (DFG 2003), for example, documents that in Germany, only 2% of all doctoral students in the social sciences received some kind of structured education in 2002, which is supposed to indicate reforms in PhD education; most German economics departments remain in the traditional pure master-apprenticeship model (Berning and Falk 2004, pp. 54–55). Neglecting the importance of PhD education reforms is surprising when we consider the arguable reliance of departments on research conducted by PhD students. PhD students and postgraduates contribute a lot to scientific research in German economics departments (Fabel et al. 2002), but as recent research grant allocations by the European Research Council (2008) indicate, the potential of young German researchers is still valued poorly against many other European researchers. Failing to produce competitive PhD graduates threatens the academic prestige, if not the existence of German departments, as the Wissenschaftsrat (2006, p. 56), a constitutional body, recommended to ban non-performing departments from awarding doctoral degrees.

Governments are the main players in German higher education. They are facing increasing financial constraints and at the same time higher accountability claims of tax payers. Measures to “reinvent government” abound (Davis 2003) and higher education too saw the introduction of administered market competition and a reduction of state regulations in favour of more autonomy in public organisations (Grüning 2000; Schedler and Proeller 2000; Schimank 2005).

Taking these new governance perspectives as frame of reference, we scrutinise the effects of six new public management (NPM) instruments on one central element of higher education: PhD education.

The assessment of the impact of NPM instruments on PhD education is surprisingly unexplored. The relative impact of different management devices to shape academic behaviour must be of interest for policy-makers trying to introduce more market elements and to achieve more hierarchical self-governance in the spirit of New Public Management.

In the following chapter, we will link NPM to PhD education and unfold our level of analysis. In chapter three, we explain our empirical design and define the conditions under examination. Results for NPM instruments of successful and unsuccessful PhD education are described in chapter four. The results are then discussed in chapter five and we conclude with limitations to our study and an outlook for further research.

Linking new public management to PhD education

A quick glance at the analysis of governance of higher education in Europe

We can claim that until the mid 1980s, the common governance model of most continental European universities was a combination of academic self-governance and high levels of state regulation and control. Since then, new public management initiatives have aimed for less state regulations and more “quasi-market” elements (Kehm and Lanzendorf 2006b). There is the expectation that universities with autonomy in internal affairs and a managerial hierarchy will master the competition more efficiently.

Early analysis of higher education systems is based on the macro level to explain differences in the governance between countries. Clark (1983), for example, proposed that governance can be distinguished according to three different dimensions of co-ordination: market, state and academic oligarchy.Footnote 1 Accordingly, van Vught (1997) classified governance in a two-dimensional model of state control and state supervision. McDaniel (1996), however, suggests that a comparison of governing structure of higher institutions cannot be limited to country differences, but has to reach down to organisational levels and the instruments in force. Recently, de Boer et al. (2007) have offered a more refined categorisation of new public governance styles of higher education by using five basic dimensions: competition, academic self-governance, stakeholder guidance, state regulation and managerial self-governance.

By contrasting governance regimes based on traditional steering and NPM and referring to a crude dichotomous characteristic of each governance dimension as either a “low” or a “high” value, Schimank (2007) distinguishes two ideal types of governance in universities: the “perfect” new governance of universities combines high competition, low academic self governance, high stakeholder guidance, low state regulation, and high managerial self-governance. A “perfect” traditional governance model shows the exact opposite characteristic in each of these five governance dimensions.

But even policy regimes in Europe with the longest experience in implementing these NPM instruments like Great Britain (Leisyte et al. 2006) or The Netherlands (de Boer et al. 2006) have by far not reached “perfect” NPM governance yet. Latecomer countries like Germany (Kehm and Lanzendorf 2006a) or Austria (Lanzendorf 2006) have only implemented some NPM instruments (de Boer et al. 2007). German universities and departments experience steering attempts by many political actors with, at least from a new public governance perspective, inconsistent directions. While the federal government, for example, introduces more competition with the ‘initiative for excellence’, which is a form of indirect or distant steering (BMBF 2005), states impose direct regulations, e.g. as to the particular design of PhD education (ENB 2008). Schimank (2008), however, convincingly suggested that not only extreme realisations, but also mixed configurations could be effective.

New public management in PhD education

We can witness that higher education institutions demonstrate different paces in changing their governance structure on different levels, resulting in heterogeneous patterns of higher education governance between and within countries (de Boer et al. 2007).

In the governance of PhD education, neither Great Britain nor The Netherlands come anywhere close to ideal NPM models (Metcalfe et al. 2002; Park 2005; de Weert 2004, respectively). While hardly any NPM instruments have reached PhD education in Italy (Moscati 2004), some other European countries are experimenting with to date unclear results: France (Lemerle 2004; Dahan 2007), Switzerland (Groneberg 2007) and Germany (Hüfner 2004).

Great Britain has introduced a system of competitive allocation of research funds through the Research Assessment Exercise. Universities and departments are accountable for their academic activities, and this comprises PhD education. Departments are autonomous in the way they conduct PhD education, but only if they fulfill certain output criteria and receive an accreditation will students be eligible to apply for scholarships.

The Netherlands have introduced a new policy for PhD education in the mid-1980s (de Weert 2004). The state regulates that a PhD trainee has a position in between a student and an employee and determines their remuneration. In addition, doctoral training has to be conducted in a structured way since 1991 (Bartelse 1999). At the same time, universities and departments have autonomy in the selection of their PhD candidates and the recognition of supervisors.

Since 1996 (after a period of a very centralised higher education policy in Italy), university governance has become much more autonomous and decentralised. This decentralisation also holds true for PhD education, but university managers and individual professors are free in deciding on curricula and supervision, while the Ministry of Education determines the formal requirements (Moscati 2004).

For French universities, the formal requirements for doctoral education have become more regulated since 1999 through the introduction of doctoral schools as the formal requirement for PhD education (Dahan 2007). Additionally, the position of a director of a graduate school has established a new element of managerial hierarchy (Dahan and Mangematin 2007).

PhD education in Switzerland is characterised by high level of decentralisation and little state regulation. Each university and each department is responsible for their PhD education, which is still conducted in a traditional master-apprenticeship model. For PhD education in economics, a joint centre for structured education exists, but it is not mandatory to attend, and the centre reserves to select the potential candidates.

In Germany, governance of universities and hence PhD education is highly decentralised in the federal states. Many federal states have introduced performance-related funding based on incentive models (e.g. number of PhD students, number of female PhDs students, number of habilitations; Leszczensky and Orr 2004) or “Centres of Excellence” to improve PhD production. On a national level, the “German Research Foundation (DFG)” tenders funds for “Collaborative Research Centres” or “Research Training Groups” to enhance efforts in PhD education. The departments stay autonomous in their decisions about how to conduct PhD education.

These examples demonstrate that the governance of higher education between and within countries varies on the level of universities and in particular with regard to PhD education. Empirical studies of the impact of NPM must therefore transcend country differences.

Such systematic research on the influence of NPM instruments on activities of departments or individuals is still rare. There is even some evidence that shows that different governance instruments might enhance PhD education efforts in departments and universities (Colander 2008; Veugelers and van der Ploeg 2008). But in general, the effects of different governance instruments vary according to the academic performance criteria under consideration, as Kehm and Lanzendorf (2007) show on a university level for performance-based allocations of resources, evaluations, performance agreements, and hierarchical decision-making. Effects need not be linear. Jansen et al. (2007) have shown curvilinear effects of competition for third party funding on publication output.

In this paper, we focus on the impact of NPM on PhD education by simplifying and then applying the framework of de Boer et al. (2007) to our organisational unit of reference, the department. We examine the effect of three governance dimensions: competition, managerial self-governance/hierarchy and state regulation.Footnote 2 We distinguish two competition instruments: competition for additional funding based on local competitive performance and competition for additional funding based on national competitive performance. Under competition, individuals and departments decide autonomously whether it is worthwhile to increase academic performance, given certain incentives. We further include transparency over academic achievements, regulatory interventions on PhD education by university management and target agreements between university management and faculty members as instruments of managerial self-governance. Finally, we consider regulatory interventions by public policy actors into PhD education as state regulations.

New public management instruments

(Quasi-) markets are held responsible for the success of departments in American universities (Backes-Gellner 1992, 2001; Aghion et al. 2009). Participants in the market for PhD students compete for scarce financial resources to pay scholarships or reimburse travel expenses in order to attract excellent PhD students (DFG 2000, pp. 15–16; DFG 2003, p. 30). Many European countries, such as The Netherlands or Great Britain, have implemented radical, but transparent funding models to allocate research budgets according to academic performance criteria (European Commission 2004; Hammen 2005), whereas other continental European countries like Germany, France or Italy, still stick to traditional budgeting rules with only some exceptions.Footnote 3

Additional funding based on local competitive performance

This form of funding includes two different funding schemes: the first is characterised by low threshold criteria where public authorities or universities determine relevant academic indicators like number of undergraduates, time to degree, or gender equality, and reward results exceeding that threshold with a certain amount of money (Leszczensky and Orr 2004). For PhD education, this usually means achievements like total number of graduating PhD students, female/male-ratio or total number of post doc positions (Leszczensky and Orr 2004). The second funding scheme has more, though limited competitive elements. Political actors tender competition for research projects that only address departments of a certain region, often with political expectations in mind.

Additional funding based on national competitive performance

Additional funding based on highly competitive performance is a very strict version of administered competition that is done regularly on a national basis. It usually follows a peer review process. Compared to individuals who apply for individual research grants, the funding of co-ordinated programmes of departments or departmental networks (in Germany for example through “Research Training Groups” or “Collaborative Research Centres”) provides large scale funding for PhD education and at the same time integrates the students into a scientific community.

Transparency over academic achievements

Although sometimes fiercely criticised (e.g. Frey 2007), university management may demand transparency of the academic output of departments and faculty members through evaluations to assess the academic activities of their institutions and members. Transparency through evaluations may end up in accreditations or audits (Stensaker and Harvey 2006), with each of them following a different logic.

University management may subject departments to an accreditation procedure in which external evaluators focus on a limited and established number of input and output criteria for the whole institution or programme and arrive at a final dichotomous decision: “accredited or not accredited” (Harvey 2004). Their decision signals a quality standard in the domains under examination to the outside world. Usually, accreditations take place rather seldom,Footnote 4 but university managers might gain from a positive evaluation by raising tuition fees, attracting better students, and recruiting a top faculty. The refusal of an accreditation can have drastic negative consequences for student and professorial applications, funding, and tuition fees.

Transparency in the context of audits reflects quite a different approach. Audits need not confine themselves to established performance criteria and standards, and they in general do not result in cut-off judgements. Evaluators in quality audits compare the achievements of an institution and its programme, for instance, to the average or to some benchmark institution (Stensaker 2000) or its own mission statement. Favourable as well as unfavourable decisions are meant to support organisational development or the internal renegotiation of resources.

University regulations for departments

Regulations could be imposed by university management on departments with regard to the selection procedures, the scale, and the maximum length of studies.

Target agreements

Although Schimank (2006) portrays a sobering picture of the effects of target agreements as means of governing universities and departments, target agreements are nowadays one of the popular governance instruments in higher education (Jaeger et al. 2005; Weichselbaumer 2007). Their efficacy has been demonstrated for judges who, like professors, are faced with a complex task and with various performance criteria (Schneider 2007). The same should apply to the academic world where, however, performance criteria are even more diversified and where performance levels may show a considerable time lag (Schneider and Sadowski 2004, p. 395). The main difference to regulatory interventions lies in their negotiated character which takes individual or organisational characteristics into account.

Public policy regulations for departments

Academic behaviour of departments and individuals can also be steered by regulations of public policy actors requiring, for instance, a certain ratio of foreign PhD students in a programme (ENB 2008) or the fixing of the financial assistance or the legal status of PhD students (de Weert 2004). Table 1 summarises the six NPM instruments that are divided into three governance dimensions.

As Schimank (2007) and de Boer et al. (2007) have already demonstrated, configurations of pure traditional models as well as pure NPM models hardly exist. High academic quality also occurs among “mixed” governance regimesFootnote 5—at least according to NPM standards. They presume that the effectiveness of governance regimes depends on the intended results and that a certain combination of governance elements might be favourable for one academic performance indicator (e.g. PhD placement in the general labour market), while another governance regime might be conducive to another performance indicator (e.g. publication record of PhD students). We share these assumptions and claim that it might be the interplay of several governance mechanisms that either leads to or prevents an intended result (similarly Braun and Merrien 1999, p. 19). Our empirical study wants to answer this very question: Which NPM instruments or combinations thereof lead to successful PhD education?

Empirical design

We focus on the producers of PhD education, university departments and their faculty. We assess how a faculty perceives and experiences NPM instruments and whether these instruments enable successful PhD education. By focusing on the field of economics, which is highly comparable internationally, we expect that variations in the organisational setting are accountable for successful PhD education, and not country differences.

In a case study design, the information is retrieved through in-depth interviews combined with document analyses. Interviewees were asked whether they perceive an influence of either one of the instruments under consideration, either personally or for the department’s PhD education. We decided to ask several interviewees in each department to check their reliability in the statements.

We assume, as shown above, that governance regimes for PhD education are characterised by heterogeneous governance structures within countries and that clear governance patterns for PhD education hardly exist on a country level. Therefore, we selected departments according to the organisational form of their PhD education and their research record (measured by quality-weighted publications according to Combes and Linnemer 2003), assuming that these configurations can be understood as organisational and behavioural reactions to governance regimes. In line with Mayntz (2005), we argue that departments operate in a unique (local) governance regime which offers a set of incentives and consequences that lead to a particular form of PhD production and publication output as ‘corps d’esprit’.

We distinguish departments with an unstructured PhD education in a pure master-apprenticeship model, ones with a structured PhD education embedded in graduate schools or graduate centres, and mixtures between structured and unstructured PhD education. We then assigned them their publication output to receive a wide variety of different governance forms.

In pure master-apprenticeship models, PhD students are selected by a single professor who often knows these students from undergraduate classes. Students acquire new methods by working on the research topics of their supervisors and are connected tightly to the administrative and teaching duties of a professor and his chair. Professors introduce their students to the scientific community, finance them and finally grade their dissertations. We suspect that PhD education according to this model is not very susceptible to regulations and gives autonomy in details of PhD education to the individual professor. Incentives and consequences through market (in) activity may only be effective if the individuals assign value to market success.

Structured PhD education is characterised by the selection of candidates from a large pool of candidates through a committee of delegates. Students acquire new methods and additional academic knowledge in seminars and lectures, do assignments and write examinations. Supervisors and students do not match from the beginning, but only after a year or so, the grading is done by a committee, not solely by the supervisor. Several forms of structured PhD education exist. Graduate schools often comprise a variety of departments. They may be run by a dean with the competence to control the procedures and overall outcomes for all departments. Structured and centred PhD education gives only little process autonomy to the individual professor; it requires more co-ordination and collective action and should therefore be susceptible to NPM instruments that favour hierarchical co-ordination or set incentives based on joint performance.

For the analysis, we construct a set of input conditionsFootnote 6 (the six above-mentioned instruments) as described in Table 1 and relate them to successful PhD education, which in our perspective means: generating young researchers.

Sample

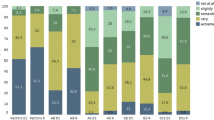

Our data consists of 14 European economics departments that vary in the organisation of their PhD education and are indicated as D1 to D14. They are from Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Great Britain, France and The Netherlands. The number of faculty members in the departments spans from 6 professors to 58 professors, although the number of 58 represents an outlier in the sample. The median is 10.5 professors, and the mean number of faculty members is 12.2 professors (neglecting the outlier). It was not possible to retrieve total numbers of students for all 14 departments, but only for 12 of them. The total number of Bachelor and Master students in economics and business studies among these 12 departments varies between 900 and 4,500 students (and one outlier of 0 students). The mean is 2,260 students, and the median 2,370 students (again neglecting the outlier). The average total number of PhD graduates varies from 2.6 graduates per year to 24.8 graduates per year with a mean of 9.0 PhD graduates and a median of 5.7 PhD graduates annually per department.

PhD students were trained in a master-apprenticeship setting in three departments (D11, D12 and D13), in a graduate school in two departments (D6 and D8), in a graduate centre in three departments (D3, D7 and D9) and in a mixed way in six departments (D1, D2, D4, D5, D10 and D14). Departments are defined to be research active if their publication output was among the best 150 European economics departments and “inactive in research” if their publication output was not among the top 150 departments (Combes and Linnemer 2003). Table 2 describes the sample.

We conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews with 43 academic and administrative key persons between May 2005 and March 2007 and probed into the influence of NPM instruments on departments and individuals.

We asked questions about the steering of a variety of their daily academic activities like administration, teaching, research in general and PhD education for the years 2001–2002 in particular. We left the interviewees unaware of our definition of a successful department. We wanted them to compare the governance styles and instruments in 2001 and 2002 to the ones predominant when the interviews took place. We were interested in their perception of individual and departmental effects. The characteristics of each instrument were scrutinised for each case and then related to the outcome and placement success for the years 2002–2006.

Analysis

Classical statistical models (e.g. regression analysis) deliver “unifinal” results that are represented in a single regression equation. Our method of analysis, “crisp set Qualitative Comparative Analysis, csQCA” (Ragin 1987, 2000), makes “equifinal” results possible, meaning that different conditions may lead to the same outcome. Instead of using the QCA software by Ragin et al. (2006), we opted for the free software TOSMANA by Cronqvist (2007). TOSMANA calculates csQCA and follows each calculation stepwise, which ensures transparency. In our case, csQCA is the method of choice for our research question.

Conditions

Output: PhD placement ratio

The choice of criteria for performance in PhD education is complex and not always easy to agree on (Colander 2008). One common measure is the publication record of PhD graduates (Hilmer and Hilmer 2007) or professors (Rauber and Ursprung 2008), but the total number of graduates (Leszczensky and Orr 2004) or the reputation of a graduate school (Ehrenberg 2004; Burris 2004) also serve as indicators for success. Yet these criteria suffer from pitfalls. Total numbers of PhD graduates do not speak for quality; publication records are watered down by long time lags, and for European institutions, there is no agreed-upon prestige hierarchy of PhD programmes.

We therefore choose the share of PhD graduates who gain an appointment as post docs or professors in the academic sector, i.e. at a PhD granting university or a university-related research institute. To create this unique dataset, we obtained the names of all PhD graduates in our sample departments for the years 2002–2006 and followed each individual career.Footnote 7

The threshold for successful and unsuccessful departments was based on theoretical assumptions at a ratio of 0.3, which is also reflected by the mathematical threshold of TOSMANA after the clustering of the data and which is in line with the average of academic placements in Europe.Footnote 8 The ratio of placements in our sample varies from 0.09 (9% of PhD graduates find a position as post docs in the academic sector) to 0.60 (60% of PhD graduates find a position as post docs in the academic sector). The condition is divided into two categories:

Input conditions: NPM instruments

All six NPM instruments of Table 1 serve as input conditions. The coding is again dichotomous and will be explained in more detail shortly. The ratio of input conditions to cases matches the theoretical findings of Marx (2006) and limits the risk of random results in the data.

Funding based on local competitive performance (condition NPM1) indicates whether a department jointly competes for additional resources with departments in the same local area like a state, a city or the same university. The application and allocation of funding is much less competitive than in funding based on peer reviews and often reflects local political goals. The condition is divided into two categories:

We coded “0” if statements were as follows: “… questions about in what direction we want to specialise and take respective initiatives have shown us that in the last few years, we rather continue to pursue third party funding in our individual research area where we have chances to compete for additional funding.”

The condition was coded “1” in the following case: “… we tried to compete for the research centre [which was tendered by the state], but it was promised to another institute [in the same state] … so our university president said that he could support us with scholarships for a little while, but his budget does not let him finance everything for a longer period of time….”

Funding based on national competitive performance (condition NPM2) indicates whether a department regularly competes for additional resources based on refereed research funding on a (supra-) national level. It is considered to be present if the interviewees indicate that several people of the faculty regularly apply for this kind of funding. The condition is divided into two categories:

Statements of the first case (code = 0) were for example: “…I am not participating in the efforts of the departments. I know from experience that they never finish arguing. I only have bad experiences. They waste too much time and in the end, all the envy comes up again, so it’s not worth the effort.”

Statements of the second case (code = 1) were for example: “… we all agreed that we do it pretty well [the research programme], but money has to come from somewhere, so we just applied for it again [the research programme] and I just wrote the application.”

Or: “It was worth several millions [the research programme] and Mr. X and Mr. Y reeled it in. I was with them as well. And that’s a good way to employ PhD students for a long time and to make them aware of the research subject.”

The condition transparency over academic achievements (condition NPM3) captures whether departments are faced with evaluations of their academic performances in the context of either accreditations or audits. It is coded “to be present” if the interviewees indicated that university management expects them to reveal their academic performance, like the number of refereed journal articles or the average duration of PhD training. We code the condition:

The condition was coded “0” for statements as in the following quoteFootnote 9: “… if they finally started assessing your performance in research and teaching as a criterion now, you would pay more attention to the external presentation. That I would actually strongly welcome.”

The condition was coded “1” for statements like: “…They come three times per year and have a look at what we do. I actually have to write a self-evaluation report, where everything is included about what we have done. We actually have to compare ourselves with other institutions, that’s very developed here. I actually think that this is not bad at all because you always have arguments to get top guys when you have to staff new faculty and it even has financial implications.”

The condition university regulations for departments (condition NPM4) reflects the influence or attempts of individuals in a managing position within the university or the department to influence the faculty and to align their academic activities to a certain academic direction, sometimes even against the majority of the faculty. The condition pertains to different issues including PhD education. It is divided into two categories:

Statements of interviewees that were coded with “0” are descriptions like the following: “…no, there is absolutely nothing I perceive in this direction [positions of deans or university president towards department activities].”

Statements of interviewees that were coded with “1” would comprise statements like the following: “…and indeed we have a university director who actually wants to enforce the [new higher education] law.”

Or: “I like Mr. X [the department chairman] quite a lot, but the independence is not granted, I don’t have the impression that I can work freely.”

The condition target agreements (condition NPM5) denotes whether university or department leaders agree on shared goals of academic performances with the faculty. The main difference to university regulations for departments lies in the joint agreement of two parties based on negotiations or shared traditions, but not on unilateral regulations. The condition is divided into two categories:

We coded the condition “0” if the interviewees had answers like: “Not yet [target agreements], but they have been talking about it for a long time.”

Or: “God beware, no [target agreements].”

We coded “1”, if the interviewees made statements like: “…well, our goal is the number of graduates, the number of articles and the time to degree.”

The condition public policy regulations for departments (condition NPM6) captures whether PhD education in departments is affected by regulations of public authorities, e.g. a fixed financial level of scholarships or a fixed goal for foreign PhD students. The condition is divided into two categories:

We coded “0” in the case of: “They [politics] can impose nothing on you. You are totally free in your research. … and being under pressure is quite impossible.”

An example for coding “1” is : “… well yes, we received X PhD positions and X assistant professorships, but then afterwards we were told that we can pay them only X% of the full salary, which I personally find quite annoying.”

The configurations of all conditions for each case are shown in the data table (Table 3). There is a great variety in the way NPM is carried out among the departments, demonstrating that we realised a sample with great variance in the application of instruments.

Results

Successful PhD education

The csQCA delivers two most parsimonious solutions of NPM instruments to explain success in PhD education (outcome = 1). Each solution consists of two configurations of instruments and their characteristics for achieving successful PhD education. The first configuration of each solution is always alike, while the second configuration of each solution disposes of different instruments. Yet the first instrument of the second configuration also remains the same in both solutions. Altogether, the most parsimonious solutions consist of four NPM instruments with different combinations, as summarised in Table 4.

Analysis of configurations 1a and 2a of solutions 1 and 2 demonstrates that successful PhD education (outcome = 1) takes place in four departments (D6, D7, D8 and D9) which face transparency over academic achievements (NPM3 {1}). Yet as can be seen in Table 3, the data demonstrates that successful PhD education also takes place in departments (D1, D10 and D14) that do not experience transparency (NPM3 {0}), which indicates that the presence of transparency over academic achievements (NPM3 {1}) is a sufficient, but not necessary condition for successful PhD education.

The analysis of configuration 1b of solution 1 gives a combination of two further NPM instruments for success. Competition for additional funding based on national competitive performance (NPM2 {1}) with no public policy regulations for departments (NPM6 {0}) is present in four successful departments (D1, D6, D10 and D14). Since successful PhD education also takes place in departments without this combination (D7, D8 and D9), configuration 1b is a sufficient, but not necessary configuration for success.

Accordingly, configuration 2b of solution 2 adds a second combination of two NPM instruments. It identifies that the configuration of additional funding based on national competitive performance (NPM2 {1}) in accordance with no university regulations for departments (NPM4 {0}) is present in five successful departments (D1, D6, D7, D10 and D14). As in configurations 1a, 2a and 1b, successful PhD education also takes place in departments (D8 and D9) which do not exhibit this combination. Configuration 2b is therefore a sufficient, but not necessary configuration for success. None of the four configurations is a necessary condition.

The relative importance of each solution and its configurations for explaining success in PhD education can be evaluated through coverage scores (Ragin 2006). Coverage scores for sufficient conditions reflect the proportion of cases in one configuration in relation to all cases and configurations in the same solution. They illustrate the weight of each configuration in a solution to explain the outcome in relation to the additional configurations of the same solution.

A coverage score yields two types of information: the first, the raw coverage, provides data on the total coverage of all cases of one configuration in relation to all cases with the same outcome. In configuration 1a, a raw coverage is composed of 4 cases (D6, D7, D8 and D9) divided by 7 cases (D1, D6, D7, D8 and D9, D10 and D14), which equals 0.57 or 57% raw coverage. This means that 57% of the outcome in solution 1 is explained by configuration 1a (the presence of transparency). In configuration 1b, the raw coverage also consists of four cases (D1, D6, D10, and D14), yielding also a raw coverage for configuration 1b of 0.57 or 57%. The raw coverage scores in solution 2 are calculated respectively. Since configuration 2a equals configuration 1a, it also has a raw coverage score of 57%. Configuration 2b though consists of five cases (D1, D6, D7, D10 and D14) and, divided by the total seven cases, leads to a raw coverage score of 71%.

The second type of information provides data on the unique coverage of the configuration. Unique coverage takes overlapping cases into account (case D6 in solution 1 and cases D6 and D7 in solution 2) that belong to more than one configuration and might therefore inflate the relevance of certain configurations. Unique coverage scores of each configuration are therefore calculated by subtracting the cases that are present in both configurations (overlap) from the cases of the configuration under consideration. Therefore, solution 1 leads to a unique coverage score for configuration 1a of 43% (0.57–0.14 = 0.43) and for configuration 1b of 43% (0.57–0.14 = 0.43) as well.Footnote 10 Solution 2 leads to a unique coverage score for configuration 2a of 29% (0.57–0.28) and a unique coverage score for configuration 2b of 43% (0.71–0.28).

The coverage scores (Table 5) demonstrate that although unique coverage scores turn out to be lower in each configuration than their raw value, the unique coverage scores still remain high for all configurations (between 0.29 and 0.43).Footnote 11 The results indicate that each configuration of the NPM instruments deliver a substantial explanation for success in PhD education with robust coverage scores.

Apart from the analysis of favourable NPM configurations for successful departments, csQCA also offers the possibility to scrutinise for configurations of unsuccessful departments, information that interestingly enough cannot be directly inferred from the success stories.

Unsuccessful PhD education

The analysis of NPM instruments for unsuccessful departments (outcome = 0) delivers one solution (Table 6) with two configurations. In three departments (D5, D11 and D12), university regulations for departments (NPM4 {1}) cause PhD education to be “unsuccessful”, according to our definition. The data table (Table 3) though demonstrates that non-successful PhD education also takes place in departments (D2, D3, D4 and D13) that do not face university regulations for departments, which indicates that configuration 3a is a sufficient, but not necessary condition for unsuccessful PhD education.

In addition, solution 3 exhibits a second configuration consisting of two conditions. Unsuccessful PhD education takes place in departments (D2, D3, D4, D11, D12 and D13) with no additional funding based on national competitive performance (NPM2 {0}) in combination with no transparency over academic achievements (NPM3 {0}). Since department D5 does not succeed either, but does not show this combination, configuration 3b is a sufficient, but not necessary configuration for a department to be unsuccessful by our definition.

The coverage scores are calculated the same as before. They are shown in Table 7. Regarding configuration 3a, 43% of the outcome “0” is explained by university regulations for departments. Two cases (D11 and D12) overlap with configuration 3b so that we subtract this fraction from the raw coverage, which leaves us with 15% unique coverage for configuration 3a.

Discussion

We analysed the NPM assumptions or convictions that a combination of less state regulations, more managerial self-governance and more market elements will be more effective for academic performance than the traditional combination of state regulations and academic self-governance.

The instrument transparency over academic achievements explains successful PhD education in four out of seven departments (D6, D7, D8 and D9). The raw and unique coverage scores (Table 5) underline the potential of this instrument alone. Its absence in combination with no joint efforts to apply for additional funding based on national competitive performance, in turn, can explain unsuccessful PhD education (configuration 3b) for six departments (D2, D3, D4, D11, D12 and D13), thus demonstrating its strong influence on faculty behaviour.

We suspect that two mechanisms explain this positive effect despite the high investment costs usually involved in realising transparency through evaluations in accreditations or audits. Positive accreditations signal the quality of the infrastructure as well as the relative performance level of departments, which will lead to higher revenues in tuition fees and also enlarge the pool of attractive applicants. Favourable audits, on the other hand, strengthen the position for departments to negotiate for resources within a university; the same might be true for unfavourable ones in so far as they justify the demand for more resources for improvement often in the preparation of an accreditation.

If incentives are connected to favourable evaluation of a department, such incentives ease collective action and perhaps the view that the local collective good PhD education is beneficial to the reputation and the quality of the research output of a department.

Additional funding based on national competitive performance is also an effective steering instrument, but only sufficiently explains successful PhD education in combination with the absence of two additional NPM instruments. Only if departments face nopublic policy regulations (departments D1, D6, D10 and D14) and nouniversity regulations (departments D1, D6, D7, D10 and D14) is funding based on national competitive performance effective.

Although the second competitive instrument under consideration, funding based on local competitive performance, is one possibility for departments to take advantage of additional resources on a lower academic threshold in order to improve research and PhD education, it is not part of the final solutions in our csQCA analysis. Although only one department (D1) is successful without this extra financial support, and two successful departments (D8 and D9) use it as an additional financing base, funding based on national competitive performance, even though in combination with additional instruments, facilitates success in PhD education. According to our results, departments which are already financing themselves through highly competitive peer-reviewed funding benefit more than departments at the eve of highly competitive research, which questions the intended effects of this instrument to initiate more PhD education and hence research.

For the analysis of managerial self-governance/hierarchy and state regulation, our results indicate that the absence of regulations for departments either by public policy or by university in combination with strong competitive elements for peer-reviewed funding are sufficient configurations for successful departments, while the presence of university regulations for departments is by itself sufficient to explain failure. We suspect that the positive effects of absence of regulations points to the fact that joint actions follow local patterns and that faculty has to find its best way to locally arrange PhD education where regulations might impede activities conducive for successful PhD education. As can be seen in Table 2, the successful departments D1, D10 and D14 conduct mixed models of PhD education and might therefore still be on their way to a final model. The absence of regulations in accordance with funding based on national competitive performance is sufficient to explain their successful PhD education.

In sum, our results demonstrate that different governance configurations lead to the same outcome and that only a few governance instruments determine successful PhD education. They point to the importance of highly competitive resources for successful PhD education and the mixed effects of hierarchy. On the one hand, side transparency or accountability of a faculty in academic achievements serves as a successful managerial steering tool. On the other hand, side direct interventions in academic behaviour through regulations by university management or state legislators will result in detrimental effects if a faculty is already engaging in competition, indicated by its regular participation in additional funding based on national competitive performance.

Limitations and outlook

The design of our study followed the theoretical assumptions of Schimank (2007, 2008) that governance in higher education can be grouped according to (five) broad dimensions, and the empirical findings by de Boer et al. (2007) state that to date internationally differently mixed new public management patterns exist that potentially produce similar results. By using csQCA, the present study focuses on the level of departments as recipients of governing attempts, in particular on the interplay of multiple instruments that aim for improving the education of PhD students to become future researchers. We demonstrated that different NPM instruments cause successful and unsuccessful PhD education and that it depends on a distinct combination of NPM instruments to enable (un-)successful PhD education. We have to account for some limitations in our study though.

One of the main NPM instruments proposed is the allocation of lump sum budgets to universities, which enables universities to administer these funds autonomously according to their preferences. We have not taken them into account because none of the interviewees indicated any awareness. The same holds true for the governance dimension of stakeholder guidance and academic self-governance, as used in the study by de Boer et al. (2007). Not a single interviewee reported much influence of university managers on their daily activities or a cut in academic self-governance. This is not completely in line with earlier findings by Leisyte (2007), Lucas (2006) or Henkel (2000), who report mixed results for the influence of university managers on departments. According to our interviewees though, the decision-making power is more or less the same because they consider the deans to be one of them: well-established professors who are usually elected for short terms, and not professional managers. After their time as deans, they step back into the faculty as regular professors. Therefore, we were told that they would generally decide in accordance with the interest of the majority (see also Leisyte 2007, p. 158).

The opposite was true for rankings of departments either by the press, public institutions or in scientific research (e.g. Combes and Linnemer 2003; Coupé 2003; Berghoff et al. 2002; Shanghai Jiao Tong University Ranking 2005). Almost everyone was concerned about the relative standing of their departments in league tables, leaving us with no variance of this particular condition.

Furthermore, in contrast to findings in the field of health (Henkel 2000) or biotechnology (Leisyte 2007), economics is a field which relies more on public third party funding for its research than on industrial funding. Therefore, a faculty may be less prone to external (industrial) influence and can decide rather autonomously how to organise the department in order to reach faculty goals. Our results of low stakeholder guidance by industrial actors may be closely related to the financial funding situation in economics, thus leaving us with no variance. In general, the different findings between our study and those of other authors match the statement by Lucas (2006, p. 22): “A number of complex models and forms of organisation continue to coexist within universities.”

As this case study covers only 14 economics departments, the number of input conditions was limited to six new public management instruments. By using csQCA and coverage scores, we were able to find and weight distinct configurations, but it was not possible to find the relative or marginal influence of each instrument on academic performances. Statistical analyses are yet to be done. This would make it possible to integrate control variables, such as the goal orientation of departments (Breneman 1976; Bartelse 1999; Sadowski et al. 2008), the didactic elements of PhD education (Bowen and Rudenstine 1992; Hilmer and Hilmer 2007) or differing resource levels (Schneider et al. 2009) and the interaction of these variables.

The departments in our sample are predominately located in continental Europe. This also means that the governance of higher education is still characterised by high degrees of political authority. It would be of utmost research interest to scrutinise the effects of governance forms which realise a much higher degree of an ideal type of “no state” and “real markets” for the higher education sector, as seems to be the case for the university system in Great Britain and the research universities in the US.

Our study focuses only on one discipline: economics. An extension to less standardised academic fields might shed more light on the influence of NPM instruments on PhD education. Finally, we restricted our PhD success variable on its value to academia. Beyond any doubt, other goals are certainly legitimate.

Notes

He later extended the framework to ‘hierarchy’ as a fourth dimension (Clark 1998).

We do not analyse the dimensions “stakeholder guidance” and “academic self-governance” because, in contrast to findings by Henkel (2000) and Leisyte (2007), nobody in our sample of interviewees indicated any external stakeholder or any reduction of academic self-governance, thus leaving us with no variance in these two dimensions.

A majority of German states, for example, established a regime of quasi-competitive elements where they first forced university departments to cut their basic resources with the perspective to establish a kind of research foundation which will redistribute these savings according to a prospective reward system (Leszczensky and Orr 2004).

Accreditation in the English Research Assessment Exercise took place in 2001 and 2008, for example.

According to Combes and Linnemers (2003) weighted ranking of publications, the economics department in Toulouse (France), which would operate under a suboptimal governance regime, is ranked 1st and the London School of Economics (Great Britain), operating in a governance regime very close to “perfect” NPM criteria, is ranked 2nd for publications in Europe.

In order not to confuse the basic assumptions of statistical methods with csQCA, we use the term “condition” instead of “independent variable”.

Amir and Knauff (2008) point out the high correlation between placement success of PhD graduates and the academic level of the departments they graduated from.

The figures match calculations of post-doc positions in several countries in the EU. In France and The Netherlands, around 29% of all PhD graduates obtain a job in academia. In Great Britain, about 27% of all PhD graduates pursue a job in universities (STRATA-ETAN 2002, pp. 84–86). In Germany, only little data exists regarding post-doc positions. But, as Enders and Bornmann (2001) have shown, around 29% of PhD graduates in biology and mathematics find a job in academia.

Several statements were not made in English, which made the authors translate them in order to come as closely as possible to the original statements.

We calculate the unique coverage scores with overlapping cases, but it is also possible to come to the same conclusion by subtracting the percentage of the raw coverage score of the opposite configuration from the total coverage, 100% (e.g. 100–57% = 43%). The latter procedure only works for two configurations.

According to Ragin (2006), a coverage score of 0.326 is “substantial”, at least for fuzzy sets.

References

Aghion, P., Dewatripont, M., Hoxby, C. M., Mas-Colell, A., & Sapir, A. (2009). The governance and performance of research universities: Evidence from Europe and the U.S. NBER Working Paper 14851. http://www.nber.org/papers/w14851. Accessed May 2009.

Amir, R., & Knauff, M. (2008). Ranking economics departments worldwide on the basis of PhD placement. Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(1), 185–190.

Backes-Gellner, U. (1992). Berufsethos und akademische Bürokratie–Zur Effizienz alternativer Motivations- und Kontrollmechanismen im Vergleich deutscher und US-amerikanischer Hochschulen. Zeitschrift für Personalforschung, 6(4), 403–435.

Backes-Gellner, U. (2001). Indikatorenorientierte Mittelvergabe in der Universität: Chancen und Risiken. In I. Ebsen & R. Ewert (Eds.), Das Neue Steuerungsmodell und die Universitätsreform (pp. 61–78). Frankfurt am Main: Ein Tagungsband.

Bartelse, J. (1999). Concentrating the minds. Utrecht: Uitgeverij Lemma.

Berghoff, S., Federkeil, G., Giebisch, P., Hachmeister, C.-D., & Müller-Böling, D. (2002). Das Forschungsranking deutscher Universitäten. Centrum für Hochschulentwicklung, Arbeitspapier 40. http://www.che.de/downloads/AP40.pdf. Accessed July 2009.

Berning, E., & Falk, S. (2004). Promotionsstudien: ein Beitrag zur Eliteförderung. Beiträge zur Hochschulforschung, 3, 54–77.

BMBF. (2005). Bund-Länder-Vereinbarung gemäß Artikel 91 b des Grundgesetzes (Forschungsförderung) über die Exzellenzinitiative des Bundes und der Länder zur Förderung von Wissenschaft und Forschung an deutschen Hochschulen. Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung. http://www.bmbf.de/pub/pm19_2005-anlage-vereinbarung.pdf. Accessed Aug 2008.

Bowen, W. G., & Rudenstine, N. L. (1992). In pursuit of the Ph.D. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Braun, D., & Merrien, F.-X. (1999). Governance of universities and modernization of the state: Analytical aspects. In D. Braun & F.-X. Merrien (Eds.), Towards a new model of governance for universities? A comparative view (pp. 9–33). London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley.

Breneman, D. W. (1976). The Ph.D. production process. In J. T. Froomkin, D. T. Jamison, & R. Radner (Eds.), Education as an industry (pp. 1–52). Cambridge: Ballinger.

Burris, V. (2004). The academic caste system: Prestige hierarchies in PhD exchange networks. American Sociological Review, 69, 239–264.

Clark, B. R. (1983). The higher education system. Academic organizations in cross-national perspective. Berkeley CA: University of California Press.

Clark, B. R. (1998). Creating entrepreneurial universities: Organizational pathways of transformation. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Colander, D. (2008). The making of a global european economist. Kyklos, 1(2), 215–236.

Combes, P.-P., & Linnemer, L. (2003). Where are the economists who publish? Publication concentration and rankings in Europe based on cumulative publications. Journal of the European Economic Association, 1(6), 1250–1308.

Coupé, T. (2003). Revealed performances: Worldwide ranking of economists and economics departments, 1990–2000. Journal of the European Economic Association, 1(6), 1309–1345.

Cronqvist, L. (2007). TOSMANA. Tool for small-N analysis. http://www.tosmana.net/. Accessed 1 June 2008.

Dahan, A. (2007). Institutional change and professional practices: The case of the French doctoral studies. In Paper presented at AOM Academy of Management, 8. Philadelphia (USA).

Dahan, A., & Mangematin, V. (2007). Institutional change and professional practices: The case of the French doctoral education. In Paper presented at the Première conférence internationale du RESUP “Les Universités et leurs marchés” in Paris, Feb, 1st–3rd 2007.

Davis, G. (2003). A contract state? New public management in Australia. In P. Koch & P. Conrad (Eds.), New public service (pp. 177–197). Wiesbaden: Gabler.

De Boer, H., Leisyte, L., & Enders, J. (2006). The Netherlands—steering from a distance. In B. Kehm & U. Lanzendorf (Eds.), Reforming university governance. Changing conditions for research in four European countries (pp. 29–96). Bonn: Lemmens.

De Boer, H., Enders, J., & Schimank, U. (2007). On the way towards new public management? The governance of university systems in England, the Netherlands, Austria and Germany. In D. Jansen (Ed.), New forms of governance in research organizations (pp. 137–152). Dordrecht: Springer.

De Weert, E. (2004). The Netherlands. In J. Sadlak (Ed.), Doctoral studies and qualifications in Europe and the United States: Status and prospects (pp. 77–97). Bucharest: UNESCO-Cepes.

DFG. (2000). Die zukünftige Förderung des wissenschaftlichen Nachwuchses durch die DFG. Empfehlungen der Präsidialarbeitsgruppe Nachwuchsförderung. Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. http://www.dfg.de/aktuelles_presse/reden_stellungnahmen/2000/index.html. Accessed 17 Oct 2003.

DFG. (2003). Entwicklung und Stand des Programms “Graduiertenkollegs”—Erhebung 2003. http://www.dfg.de/forschungsfoerderung/koordinierte_programme/graduiertenkollegs/download/erhebung2003.pdf. Accessed 1 Aug 2008.

Ehrenberg, R. G. (2004). Prospects in the academic labor market for economists. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18, 227–238.

ENB. (2008). Incentives—Bavarian graduate program in economics (BGPE). Elitenetzwerk Bayern. http://www.elitenetzwerk.bayern.de/54.0.html. Accessed 5 Aug 2008.

Enders, J., & Bornmann, L. (2001). Karriere mit Doktortitel? Ausbildung, Berufsverlauf und Berufserfolg von Promovierten. Frankfurt: Campus.

European Commission. (2004). Mapping of excellence in economics. ftp://ftp.cordis.europa.eu/pub/indicators/docs/mpe_en.pdf. Accessed 1 Sep 2008.

European Research Council. (2008). ERC starting grant competition 2007—results. European Research Council. http://erc.europa.eu/pdf/Listfinal.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2008.

Fabel, O., Lehmann, E., & Warning, S. (2002). Vorträge im offenen Teil der Jahrestagung des Vereins für Socialpolitik und Promotionshäufigkeiten als Qualitätsindikatoren für Universitäten. In U. Backes-Gellner & C. Schmidtke (Eds.), Hochschulökonomie–Analyse interner Steuerungsprobleme und gesamtwirtschaftliche Effekte (pp. 13–31). Berlin: Duncker und Humblot.

Frey, B. (2007). Evaluierungen, evaluierungen… evaluitis. Perspektiven der Wirtschaftspolitik, 8(3), 207–220.

Groneberg, M. (2007). Doktorierende in der Schweiz. Portrait 2006. Center for Science and Technology Studies. http://www.cest.ch/Publikationen/2007/Doktorierende%20in%20der%20Schweiz.pdf. Accessed Aug 2008.

Grüning, G. (2000). Grundlagen des new public management: Entwicklung, theoretischer Hintergrund und wissenschaftliche Bedeutung des New Public Management aus Sicht der politisch-administrativen Wissenschaften der USA. Münster: LIT.

Hammen, A. (2005). Hochschulen im Positionierungswettbewerb. Ehemalige britische Polytechnics im Forschungswettbewerb–Eine empirische analyse. Trier: Diplomarbeit.

Harvey, L. (2004). The power of accreditation: View of academics. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 26(2), 207–223.

Henkel, M. (2000). Academic identities and policy change in higher education. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Hilmer, C. E., & Hilmer, M. J. (2007). On the relationship between the student–advisor match and early career research productivity for agricultural and resource economics Ph.D.s. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 89(1), 162–175.

Hüfner, K. (2004). Germany. In J. Sadlak (Ed.), Doctoral studies and qualifications in Europe and the United States: Status and prospects (pp. 51–61). Bucharest: UNESCO-Cepes.

Jaeger, M., Leszczensky, M., Orr, D., & Schwarzenberger, A. (2005). Formelgebundene Mittelvergabe und Zielvereinbarungen als Instrumente der Budgetierung an deutschen Universitäten: Ergebnisse einer bundesweiten Befragung. HIS-Kurzinformation, A13.

Jansen, D., Wald, A., Franke, K., Schmoch, U., & Schubert, T. (2007). Drittmittel als Performanzindikator der wissenschaftlichen Forschung. Zum Einfluss von Rahmenbedingungen auf Forschungsleistung. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 59(1), 125–149.

Kehm, B., & Lanzendorf, U. (2006a). Germany—16 Länder approaches to reform. In B. Kehm & U. Lanzendorf (Eds.), Reforming university governance. Changing conditions for research in four European countries (pp. 135–186). Bonn: Lemmens.

Kehm, B., & Lanzendorf, U. (2006b). Comparison: Changing conditions for research through new governance. In B. Kehm & U. Lanzendorf (Eds.), Reforming university governance. Changing conditions for research in four European countries (pp. 187–212). Bonn: Lemmens.

Kehm, B., & Lanzendorf, U. (2007). The impacts of university management on academic work: Reform experiences in Austria and Germany. Management Revue, 18(2), 153–173.

Lanzendorf, U. (2006). Austria—from hesitation to rapid breakthrough. In B. Kehm & U. Lanzendorf (Eds.), Reforming university governance. Changing conditions for research in four European countries (pp. 99–134). Bonn: Lemmens.

Leisyte, L. (2007). University governance and academic research. http://www.utwente.nl/cheps/phdportal/CHEPS%20Alumni%20and%20Their%20Theses/thesisleisyte.pdf. Accessed April 2009.

Leisyte, L., de Boer, H., & Enders, J. (2006). England–the prototype of the ‚evaluative state’. In B. Kehm & U. Lanzendorf (Eds.), Reforming university governance. Changing conditions for research in four European countries (pp. 21–57). Bonn: Lemmens.

Lemerle, J. (2004). France. In J. Sadlak (Ed.), Doctoral studies and qualifications in Europe and the United States: status and prospects (pp. 37–50). Bucharest: UNESCO-Cepes.

Leszczensky, M., & Orr, D. (2004). Kurzinformation A2/2004: Staatliche Hochschulfinanzierung durch indikatorgestützte Mittelverteilung. Hannover: HIS.

Lucas, L. (2006). The research game in academic life. Maidenhead: SRHE and Open University Press.

Marx, A. (2006). Towards more robust model specification in QCA results from a methodological experiment. In Compass Working Paper (p. 43).

Mayntz, R. (2005). Governance theory als fortentwickelte Steuerungstheorie? In G. F. Schuppert (Ed.), Governance-forschung. Vergewisserung über stand und entwicklungslinien (pp. 11–20). Baden-Baden: Nomos.

McDaniel, O. C. (1996). The paradigms of governance in higher education systems. Higher Education Policy, 9(2), 137–158.

Metcalfe, J., Thomson, Q., & Green, H. (2002). Improving standards in postgraduate research degree programmes. Higher Education funding council for England. http://www.hefce.ac.uk/pubs/RDreports/2002/rD6_02/rD6_02.pdf. Accessed Aug 2008.

Moscati, R. (2004). Italy. In J. Sadlak (Ed.), Doctoral studies and qualifications in Europe and the United States: Status and prospects (pp. 63–76). Bucharest: UNESCO-Cepes.

Park, C. (2005). New variant PhD: The changing nature of the doctorate in the UK. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 27(2), 189–207.

Ragin, C. C. (1987). The comparative method. Moving beyond qualitative and quantitative strategies. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

Ragin, C. C. (2000). Fuzzy-set social science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ragin, C. C. (2006). Set relations in social research: Evaluating their consistency and coverage. Political Analysis, 14(3), 291–310.

Ragin, C. C., Drass, K. A., & Davey, S. (2006). Fuzzy-set/qualitative comparative analysis 2.0. Tucson, AZ: Department of Sociology, University of Arizona.

Rauber, M., & Ursprung, H. W. (2008). Evaluation of researchers: A life cycle analysis of German academic economists. In M. Albert, D. Schmidtchen, & S. Voigt (Eds.), Conferences on new political economy 25, scientific competition (pp. 101–122). Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Sadlak, J. (2004). Doctoral studies and qualifications in Europe and the United States: Status and prospects. Bucharest: UNESCO-Cepes.

Sadowski, D., Schneider, P., & Thaller, N. (2008). Do we need incentives for PhD supervisors? European Journal of Education, 43(3), 315–329.

Schedler, K., & Proeller, I. (2000). New public management. Bern: Haupt.

Schimank, U. (2005). ‘New public management’ and the academic profession: Reflections on the German situation. Minerva, 43, 361–376.

Schimank, U. (2006). Zielvereinbarungen in der Misstrauensfalle. Die Hochschule, 2, 7–18.

Schimank, U. (2007). Die governance-perspektive: Analytisches potenzial und anstehende konzeptionelle Fragen. In H. Altrichter, T. Brüsemeister, & J. Wissinger (Eds.), Educational governance. Handlungskoordination und steuerung im Bildungssystem (pp. 231–260). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Schimank, U. (2008). Ökonomisierung der Hochschulen–eine Makro-Meso-Mikro-Perspektive. In K.-S. Rehberg (Ed.), Die natur der gesellschaft. Verhandlungen des 33. Kongresses der Deutschen Gesellschaft für soziologie in Kassel 2006 (pp. 622–635). Frankfurt: Campus.

Schneider, M. (2007). Zielvorgaben und organisationskultur: Eine fallstudie. Die Betriebswirtschaft, 6, 621–639.

Schneider, M., & Sadowski, D. (2004). Performancemanagement in der öffentlichen Verwaltung–eine unlösbare Aufgabe. Die Verwaltung, 37(3), 377–399.

Schneider, P., Thaller, N., & Sadowski, D. (2009). Success and failure of PhD programs: An empirical study of the interplay between interests, resources and organizations. In D. Jansen (Ed.), Governance and performance in the German public research sector; disciplinary differences. Dordrecht: Springer. (forthcoming).

Shanghai Jiao Tong University Ranking. (2005). Top 500 world universities. Institute of Higher Education, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. http://ed.sjtu.edu.cn/rank/2005/ARWU2005TOP500list.htm. Accessed 1 Aug 2008.

Stensaker, B. (2000). Quality as discourse: An analysis of external audit reports in Sweden 1995–1998. Tertiary Education and Management, 6, 305–317.

Stensaker, B., & Harvey, L. (2006). Old wine in new bottles? A comparison of public and private accreditation schemes in higher education. Higher Education Policy, 19, 65–85.

STRATA-ETAN Expert Working Group. (2002). Human resources in RTD (including attractiveness of S&T professions). ftp://ftp.cordis.europa.eu/pub/era/docs/bench_0802.pdf. Accessed Aug 2008.

Van Vught, F. A. (1997). Combining planning and the market: an analysis of the government strategy towards higher education in the Netherlands. Higher Education Policy, 10(3/4), 211–224.

Veugelers, R., & van der Ploeg, F. (2008). Reforming European universities: Scope for an evidence-based process. CESIFO Working Paper (p. 2298).

Weichselbaumer, J. (2007). Hochschulinterne Steuerung über Zielvereinbarungen–ein prozessbegleitender ökonomischer Ansatz an der TU München. Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft, 5, 157–172.

Wissenschaftsrat. (2002). Empfehlungen zur Doktorandenausbildung. Wissenschaftsrat. http://www.wissenschaftsrat.de/texte/5459-02.pdf. Accessed 1 Aug 2008.

Wissenschaftsrat. (2006). Empfehlungen zur künftigen Rolle der Universitäten im Wissenschaftssystem. http://www.wissenschaftsrat.de/texte/7067-06.pdf. Accessed 1 Aug 2008.

Acknowledgments

Study was financially supported by the German Research Foundation “Internationale Wettbewerbs- und Innovationsfähigkeit von Universitäten und Forschungsorganisationen – Neue Governanceformen (FOR 517)”. Project title: “Die Förderung wissenschaftlichen Nachwuchses: ein (lokales) Kollektivgut?” We would like to thank Martin Schneider, Lasse Cronqvist, Gregory Jackson, Jürgen Enders, Christine Musselin with her Centre de Sociologie des Organisations and the Fondation Maison des Sciences de l’Homme as well as two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on earlier versions of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schneider, P., Sadowski, D. The impact of new public management instruments on PhD education. High Educ 59, 543–565 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9264-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9264-3