Abstract

Thellungiella halophila (salt cress) is a salt tolerant species with high genetic and morphological similarity to model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. The role of growth regulators in imposing seed dormancy and a release from it while responding to environmental signals has been examined. Seeds of salt cress possess a deep dormancy at maturity which decreased during after-ripening and cold stratification. After-ripened seeds of salt cress failed to germinate in dark and in strong light (134 µmol m−2 s−1) while best seed germination was obtained in weak white light (1–10 µmol m−2 s−1) at 22 °C. The germination of non-dormant salt cress seeds was also regulated by red and far-red light. Light enhanced the sensitivity to gibberellin in dark-imbibed salt cress seeds and strong light inhibited biosynthesis of gibberellins. The endogenous abscisic acid was not affected by strong light implying that inhibition of seed germination is not mediated through ABA signals. Higher seed germination was recorded at a constant temperature of 20 °C and a thermoperiod of 15/25 °C (12 h strong light/12 h dark). Seeds of salt cress when exposed to 400 mM NaCl for 10 days maintain their viability however there was a heavy mortality among Arbidopsis seeds under similar conditions. Our data indicates that seed germination in salt cress is highly regulated by environmental and hormonal signals to provide opportunities to germinate under natural conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Soil salinity is the main factor in controlling seed germination, a critical stage in the life history, leading to the establishment of halophyte populations (Ungar 1995; Katembe et al. 1998; Gul et al. 2013). There are different ecological strategies adapted by halophytes for the successful seed germination in saline habitat (Song et al. 2005). Seed of a number of halophytes could germinate in high salinity (Khan et al. 2001a, b), while others remained a part of the seed bank despite high salinity and temperature stress to exploit windows of the opportunity offered through rainfall (Khan and Gul 2002). Halophytes like Atriplex and Salicornia and Suaeda species produced dimorphic or polymorphic seeds (Ungar 1979; Khan et al. 2001a, b; Li et al. 2005, 2008) to provide differential opportunities to germinate and recruit in a population (Ungar 1979; Khan et al. 2001a, b; Li et al. 2005, 2008).

Seed germination is a complex physiological process regulated by variety of endogenous factors including plant growth regulators and ambient conditions such as light, temperature, cold stratification and storage (Bewley and Black 1994). Light (low-fluence response, LFR) and cold stratification promote germination of smaller sized seeds (Bewley and Black 1994; Kigel 1995; Milberg et al. 2000), and seed germination in Arabidopsis is mediated through enhanced biosynthesis of gibberellins through red/far red and phytochrome B (Yamaguchi and Kamiya 2002; Yamaguchi et al. 2004). Continuous white light (High-irradiance response, HIR) inhibits germination of some species from desert such as Bromus sterilis, B. erectus, Nemophila insignis, Phacelia tanacetifolie, Agriophyllum squarrosum, Artemisia ordosica (Thompson 1989; Bewley and Black 1994; Kigel 1995; Zheng et al. 2004, 2005), through the action of phytochrom A (Shichijo et al. 2001). Light can both promote and inhibit seed germination of a species under different conditions e.g. Oryzopsis miliaceae, Sinapis arvensis and Datura ferox (Negbi and Koller 1964; Bartley and Frankland 1982; de Miguel et al. 2000; Arana et al. 2007). The dual roles of light in seed germination might be mediated by different types of phytochromes (Shinomura et al. 1994, 1996; Shichijo et al. 2001; Arana et al. 2007). Physiological basis of plant responses to HIR and LFR has not been adequately explored (Arana et al. 2007).

Temperature regulates seed dormancy and the rate of germination (Bewley and Black 1994; Gul and Weber 1999; Khan et al. 2001a, b; Zheng et al. 2004, 2005). Alternating temperature regimes have been reported to promote seed germination more than the constant temperatures (Thompson and Grime 1983; Khan et al. 2001a, b; Zheng et al. 2004, 2005). The dormancy level is reduced through after-ripening (dry and warm storage) and cold stratification in several grass species (Bungard et al. 1997; Schutz et al. 2002; Li et al. 2005).

Hormonal and environmental regulation of seed dormancy and germination has been best understood at the molecular level in the model species Arabidopsis (Bewley 1997; Koornneef et al. 2002; Finkelstein et al. 2008). Gibberellin (GA) is positive regulators of seed germination, while abscisic acid (ABA) plays an essential role in inducing seed dormancy (Jacobsen et al. 2002; Koornneef et al. 2002; Finkelstein et al. 2008).

Salt cress (Thellungiella halophila) is a close relative of model plant, Arabidopsis, and exhibits high tolerance to salinity, drought, cold and nitrogen deficiency (Inan et al. 2004; Kant et al. 2006, 2008; Griffith et al. 2007). It has emerged as a new model halophyte for the molecular elucidation of abiotic stress tolerance recently and information on full genome sequence is available (Inan et al. 2004; Kant et al. 2006, 2008; Griffith et al. 2007; Kant et al. 2008; Amtmann 2009; Oh et al. 2010; Dassanayake et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2012). However, previous investigations have focused on physiological, metabolic, and molecular aspects of abiotic stress tolerance mainly at the vegetative stage (Inan et al. 2004; Kant et al. 2006; Griffith et al. 2007; Kant et al. 2008; Amtmann 2009; Pang et al. 2010; Pedras and Zheng 2010). The mechanisms of plant tolerance to stress usually are different at various stages of growth (Mass and Poss 1989; Mass and Grieve 1994; Khan and Gul 2002; Zeng et al. 2002). Effect of salinity and other environmental factors (such as light, cold stratification and temperature) along with the mechanisms through which they control seed germination of salt cress is not well known. Information about the seeds germination strategies of salt cress is critical in its success as a model plant to study high salinity tolerance.

We would like to test the hypothesis that: (1) seed germination of salt cress is highly regulated by plant hormones and (2) Salinity tolerance of salt cress is similar to halophytes. The present investigation is designed to determine if the application of plant hormones could alleviate the effects of salinity on the germination of salt cress seeds under both strong light and dark as well as salt stress conditions.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Seeds of salt cress (T. halophila) were collected during May of 2005 from Hebei Province in China. Seeds after cleaning were stored in paper bags inside desiccators (with silica gel) at room temperature (herein after called field batch). In order to get same batch of Arabidopsis and salt cress seeds, they were propagated together in a growth chamber. Seeds of salt cress were sown in soil (Metro mix 500; Scotts) spread on propagation trays. After sowing, the trays were placed at 4 °C in dark cold room for 10 days for cold stratification. Then seed trays were transferred to growth chamber under 25 °C-day/15 °C-night temperature and 16-h photoperiods (photosynthetic photon flux at 134 µmol m−2 s−1 from cool-white fluorescent lamps) for 10 days. To mimic vernalization periods, the trays were moved back to the cold room at 4 °C for 21 days, with a 16 h photoperiod. After vernalization trays with seedlings of salt cress were transferred to growth chamber again for getting seeds. After maturity, the seeds of salt cress were cleaned and stored in paper bags inside desiccators (with silica gel) at room temperature until germination experiments (herein after called growth chamber batch).

Germination tests

The seeds were washed with 0.02 % Triton X solution, rinsed with water and then placed on a layer of wet filter paper (3MM; Whatman, Maidstone, UK) in a sealed plastic Petri dish. Germination tests were performed using triplicate samples. Unless otherwise mentioned, seeds from growth chamber batch were used and incubated at 22 °C under continuous white light (134 µmol m−2 s−1 from fluorescent lamp). Seeds were scored as germinated when radicle protrusion was visible.

Light treatments

The light intensity regimes included 134, 32, 8, 0.87, 0.09, 0.01 µmol m−2 s−1 and dark, with 22 °C constant temperature. Seeds were handled under a dim green safety light for dark treatment, and black boxes were used to provide completely dark environments. For the other light treatment, seeds were placed under a photosynthetic photon fluxed intensity of 134 μ mol m−2 s−1 (measured at the top of the Petri dish) and inspected daily. The light intensity (measured using a light sensor at the bottom of different layers of paper) was adjusted by wrapping the outside of plastic petri-dish with layers of thin white papers.

The far-red (FR) light pulse treatment consisted of 3 min of FR light irradiation (91 µmol m−2 s−1) supplied from light-emitting diodes (MIL-IF18; Sanyo Biomedical, Osaka, Japan) passed through a FR acrylic filter (Deraglass A900, 2 mm thick; Asahikasei, Tokyo, Japan). The red-light-pulse treatment consisted of 3 min of red (R) light irradiation (120 µmol m−2 s−1) supplied from light-emitting diodes (MIL-R18; Sanyo Biomedical). Seed were checked daily for different light intensity treatments. Seeds were observed only on the last day for the dark, R and FR treatments. The tests continued until the germination percentage became effectively constant.

Chemicals

Plant growth regulators, GA1, GA3, GA4 were used at 0.1, 1, 5, 10, 50 μM in the presence of 50 μM Paclobutrazol for seed germination in strong light (134 µmol m−2 s−1) and in dark. GAs was purchased from Lewis Mander (Australian National University, Australia).

Temperature

The five alternating temperature regimes: 5/15, 10/20, 15/25, 20/30, 25/35 °C (12 h night temperature/12 h day temperature, light intensity at 134 µmol m−2 s−1 for day time) were used. These regimes closely approximate the spring and summer germination conditions in the habitats located in China. In order to identify suitable germination temperature, five constant temperature regimes (viz. 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 °C) were also used under 10 µmol m−2 s−1 light intensity.

Salinity

To determine the effect of salinity on seed germination, NaCl solutions (0, 50, 100, 150, 200, 300 and 400 mM) were used. Germination of Arabidopsis and salt cress seeds was checked 10 days after the start of treatment with different concentration of NaCl then un-germinated seeds were transferred to distilled water for 4 days to determine whether seeds survived high salinity, light and temperature stresses (recovery), and remaining un-germinated seeds were incubated with 10 µM GA4 for another 4 days for determining final germination under 15/25 °C temperature regime (night temperature/day temperature, light intensity at 134 µmol m−2 s−1 for day time).

Quantitation of ABA and GAs

Three replicates of 50 mg (for ABA analysis) and 500 mg (for GAs analysis) of dry salt cress seeds of growth chamber batch (pre-imbibition weight) were allowed to imbibe in water under 10 and 134 µmol m−2 s−1 light intensity for 4 days. Endogenous ABA and GA levels were determined by LC–MS/MS analysis using a Quadrupole/Time-of-flight Tandem Mass Spectrometer (Q-tof Premier; Waters) and an Acquity Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatograph (Waters) as described by Saika et al. (2007) and Varbanova et al. (2007). The amount of each compound was determined by spectrometer software (MassLynxTM v. 4.1, Micromass).

Statistical analyses

Germination data were arcsine transformed before statistical analyses to ensure homogeneity of variance. Analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to test whether the treatments had significant effect on germination and other parameters. Significant differences among individual means were determined using a Bonferroni test at 1 % level (SPSS version 11.0 for windows, 2001).

Results

Release from seed dormancy by after-ripening and stratification

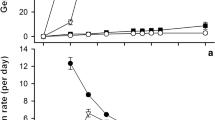

Fresh seeds of salt cress were highly dormant, as shown in Fig. 1a. They became free from dormancy 10 months after the harvest from growth batch. Cold stratification treatment (dark imbibition at 4 °C for several days) induced germination in all dormant salt cress seeds obtained from growth chamber batch (Fig. 1b). In the following experiments, unless otherwise mentioned, we used non-dormant growth chamber batch seeds (i.e., after-ripened for approximately 1 year).

Effect of after-ripening and cold treatment on breaking salt cress seed dormancy. a Dry seeds were stored at room temperature after the harvest, and then imbibed for 10 days under continuous white light (10 µmol m−2 s−1) at 22 °C to score germination. b For cold treatment, seeds were imbibed in the dark, incubated at 4 °C for the indicated period, and then incubated at 22 °C under continuous light (10 µmol m−2 s−1) for 10 days before scoring for germination

Light regulation of seed germination via phytochrome (light intensity and quality)

To examine if light is required for germination of salt cress seeds, after-ripened seeds were exposed to fluorescent white light (10 µmol m−2 s−1) during imbibition for given periods, and then incubated in the dark (Fig. 2a, c). Dark-imbibed seeds germinated only poorly, while light irradiation during the first 200 min after imbibition induced germination in most of the seeds (Fig. 2a, c). Light application for 50 min from the start of imbibition did not induce germination in this experiment.

Light and gibberellins on salt cress seed germination. a Light conditions. White bar indicates light-imbibition (10 µmol m−2 s−1) and black bar depicts incubation in the dark. The start of imbibition is shown by a reverse triangle. b Light treatments for phytochrome-regulation. Seeds were imbibed in the dark, and then irradiated with a pulse of FR-light, R-light or a combination of pulses of FR- and R-light. Black bar indicates dark-imbibition and the start of imbibition is shown by a reverse triangle. c As outlined in (a), imbibed seeds were irradiated with fluorescent white light for a given period (20–360 min), and then incubated in the dark until germination was scored at 10 days at 22 °C. d Germination percentage under different light conditions. FR/R: an R-pulse was given following an FR-pulse. FR/Stratification: a cold stratification was given following an FR-pulse. e Light intensity on salt cress seed germination. Seeds were incubated in different white light intensity until germination was scored at 10 day at 22 °C. f Effect of GA1 GA3 and GA4 in the presence of 50 μM paclobutrazol on the germination of salt cress in strong light (134 μmol m−2 s−1) and dark at 22 °C

The role of phytochrome in the control of salt cress seed germination was studied using non-dormant seeds that were imbibed in the dark and then exposed to different combinations of R- and/or FR-light pulses (Fig. 2b, d). A pulse of R-light and cold stratification stimulated germination of dark-imbibed seeds, while a following FR pulse inhibited germination in a photo-reversible manner (Fig. 2b, d). Results of repeated pulse treatments (FR/R and FR/R/FR) also indicated the involvement of phytochrome in the control of seed germination (Fig. 2b, d). However, strong continuous light (more than 32 µmol m−2 s−1) also significantly inhibited seed germination (Fig. 2e). All seeds germinated at relatively mild light intensity (1–10 µmol m−2 s−1).

Effect of phytohormones on seed germination in strong light

Seeds imbibed in strong light were more sensitive (nearly ten-fold) to exogenous GA4 than dark-imbibed seeds. GA4 showed higher activities than GA1 and GA3 in promoting seed germination in strong light (Fig. 2f).

Temperature

Alternating temperature treatments showed higher germination than constant temperature treatments (Fig. 3). Under 15/25 °C alternating temperature regime, salt cress seeds showed highest germination percentage. While among the constant temperature treatments higher seed germination was recoded at 10, 15 or 20 °C (Fig. 3).

Salinity

Salinity significantly inhibited seed germination of salt cress and Arabidopsis showing similar germination responses (Fig. 4) under mild light intensity (10 µmol m−2 s−1). After imbibition in 400 mM NaCl solution for 10 days, salt cress showed almost 100 % recovery from germination, while Arabidopsis showed only about 20 % recovery of germination while remaining seeds were considered dead because they did not germinate even after 10 µM GA4 treatment (Fig. 4).

Seed germination percentage salt cress and Arabidopsis. Seeds were checked when treated in different concentration of NaCl for 10 days (Germination), then un-germinated seeds were transferred to distilled water for recovery (Recovery), and remaining un-germinated seeds were incubated with 10 µM GA4 for another 4 days for determining final germination under 15/25 °C in 12 h/12 h (night/day) temperature regime

Endogenous hormones

There was little difference in the ABA content between germinating seeds under strong and weak (Fig. 5) light intensity after imbibition in water for 4 days. The content of active GA (GA4) was higher in seeds under week light intensity than the seeds under strong light, although level of its direct precursor (GA9) was similar (Fig. 5). At the same time, the contents of other precursors (GA12, GA15, GA24) of active GA were higher in seeds under week light intensity than the seeds under strong light (Fig. 5).

Discussion

We report here environmental and hormonal regulation of seed dormancy and germination in salt cress. In seeds of some halophytes, the level of dormancy is modulated seasonally to allow seedling development under subsequent favorable soil conditions (Karssen 1982; Ungar 1995; Benech-Arnold et al. 2000). Besides seasonal regulation, the seeds appear to respond to the quality and quantity of light by varying depth of their location in the soil (Milberg et al. 2000). Our data on salt cress seeds are consistent with these reports. Fresh salt cress seeds were highly dormant, and after-ripening in our experimental condition proceeded for over 1 years. Cold stratification (4 °C in the dark for 10–20 days) was effective to break seed dormancy (Fig. 1b). The results implied that salt cress might control its dormancy level to build a large seed bank and survive in soil for a longer period and germinate in early spring when soil condition becomes more favorable.

After-ripened seeds could not germinate in dark, while stronger light (higher than 32 µmol m−2 s−1) also inhibited seed germination. This specific light requirement for seed germination would prevent seeds from germination and may lead to secondary dormancy if they are buried deep in the soil. Seeds present on the surface of the soil also exposed to the risk of high light intensity, high salinity and the loss of moisture during early spring (Jin et al. 1999).

Light can both promote and inhibit seed germination of salt cress (Fig. 2c, d, f). The dose dependent dual role of light on germination has also been reported in other plant species (Negbi and Koller 1964; Bartley and Frankland 1982; Arana et al. 2007). Light and cold stratification promote seed germination through increase in endogenous GA levels by increasing GA3ox transcripts levels and GA sensitivity (Yamaguchi and Kamiya 2002; Yamauchi et al. 2004) in Arabidopsis. However, nature of photoinhibition is not clear although it is possible that continuous excitation of phytochrome is involved (Bartley and Frankland 1982). Our results also support the assumption that endogenous levels of GA or signals (Fig. 2f) were involved in photoinhibition of salt cress germination. However, the content of ABA showed little difference between seeds under strong or weak light intensity (Fig. 5), indicating that the variation in seed germination due to light is not regulated by ABA (Chae et al. 2004; Kusumoto et al. 2006). ABA is known to inhibit seed germination of salt cress therefore its role cannot be totally ruled out (Inan et al. 2004). Generally, GA4 could induce nearly 100 % seed germination of both batches (data not shown) in strong light and in dark, while GA1 and GA3 could partially promote seed germination. It implied that GA4 might be the active GA that was regulated by strong light (Arana et al. 2007). The detail mechanism of photo-inhibition of salt cress seed germination needs further studies (Arana et al. 2007).

Previous investigation showed that germination of Zygophyllum dumosum seeds was not affected by temperature in the range of 10–25 °C but was strongly inhibited at 30 °C (Agami 1986). Similarly, our results showed that seed germination of salt cress did not differ significantly in the temperature range of 10–20 °C for constant temperature and 10/20–15/25 °C for alternating temperature regimes. Lower temperature regimes (5 and 5/15 °C) and high temperature regimes (25 and 20/30 °C) inhibited seed germination. Similar effects have been reported in some halophytes (Khan et al. 2001a, b) and non-halophytes (Zheng et al. 2004, 2005).

When comparing the effects of alternating temperature regimes with constant temperature, the former generally led to higher germination percentage than the later. Similar results have been reported by some other plant species as well (Khan et al. 2001a, b; Zheng et al. 2004, 2005). The results implied that temperature change naturally occurring world promote seed germination in spring. The mechanism might be related to the expression of different hormone related genes that are temperature-sensitive (Argyris et al. 2008).

Salt tolerance of halophytes and many crops may vary with stage of their growth (Mass and Grieve 1994; Khan and Gul 2002; Zeng et al. 2002). It could also be expressed as: (1) the ability to tolerate high salinity without losing viability while lying in the soil (dormancy seed stage or seed bank); (2) the ability to germinate under high salinity (germination stage); (3) the ability to complete its life cycle at high salinity (vegetative and reproductive stages) (Khan and Gul 2002). Previous results showed that salt cress is more tolerant to salinity than Arabidopsis in vegetative and reproductive stages (Inan et al. 2004; Kant et al. 2006; Griffith et al. 2007; Kant et al. 2008; Amtmann 2009). Our result showed that salt cress was more tolerant to salinity than Arabidopsis in seed bank, similar result was showed in previous report (Guo et al. 2012). There is little information available on the salt tolerance mechanism in seed stage and needs further research.

Comparing with previous investigation (Inan et al. 2004), our salt cress batch seeds showed relatively high germination percentage in water and salt solution. This may due to the use of after ripened seeds in this study along with the appropriate light intensity used. When seeds were treated with cold stratification or exogenous application of GA4, salt cress seeds showed higher germination percentage than Arabidopsis under same salinity stress (data not shown). The results implied that ability to tolerate salts at germination was also affected by seed dormancy level.

In conclusion our data indicate various endogenous and environmental signals that control dormancy and germination of salt cress seeds. Seeds respond to the environmental change and break dormancy when time is appropriate for germination and recruitment. The sensitivity to environmental factors (light, salinity, cold stratification) and tolerance to salinity as well as very dormancy can explain why the species can survive in salt habitat. In addition, light enhanced the sensitivity to gibberellin in dark-imbibed salt cress seeds and strong light inhibited biosynthesis of gibberellins, and GA4 is the most active forms of GAs on seed germination.

References

Agami M (1986) The effects of different soil water potentials, temperature and salinity on germination of seeds of desert shrub Zygophyllum dumosum. Physiol Plant 67:305–309

Amtmann A (2009) Learning from evolution: Thellungiella generates new knowledge on essential and critical components of abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Mol Plant 2:3–12. doi:10.1093/mp/ssn094

Arana MV, Burgin MJ, de Miguel LC, Sánchez RA (2007) The very-low-fluence and high-irradiance responses of the phytochromes have antagonistic effects on germination, mannan-degrading activities, and DfGA3ox transcript levels in Datura ferox seeds. J Exp Bot 58:3997–4004

Argyris J, Dahal P, Hayashi E, Still DW, Bradford KJ (2008) Genetic variation for lettuce seed thermoinhibition is associated with temperature-sensitive expression of abscisic acid, gibberellin, and ethylene biosynthesis, metabolism, and response genes. Plant Physiol 148:926–947. doi:10.1104/pp.108.125807

Bartley MR, Frankland B (1982) Analysis of the dual role of phytochrome in the photoinhibition of seed germination. Nature 300:750–752

Benech-Arnold RL, Sáncheza RA, Forcellab F, Kruka BC, Ghersaa CM (2000) Environmental control of dormancy in weed seed banks in soil. Field Crops Res 67:105–122

Bewley JD (1997) Seed germination and dormancy. Plant Cell 9:1055–1066

Bewley JD, Black M (1994) Seeds: physiology of development and germination, 2nd edn. Plenum Press, New York, pp 230–267

Bungard RA, Mcneil D, Morton JD (1997) Effects of chilling, light and nitrogen-containing compounds on germination, rate of germination and seed imbibition of Clematis vitalba L. Ann Bot 79:643–650

Chae SH, Yoneyama K, Takeuchi Y, Joel DM (2004) Fluridone and norflurazon, carotenoid-biosynthesis inhibitors, promote seed conditioning and germination of the holoparasite Orobanche minor. Physiol Plant 120:328–337

Dassanayake M, Oh DH, Haas JS, Hernandez A, Hong H, Ali S, Yun DJ, Bressan RA, Zhu JK, Bohnert HJ, Cheeseman JM (2011) The genome of the extremophile crucifer Thellungiella parvula. Nat Genet 43:913–918. doi:10.1038/ng.889

de Miguel L, Burgin M, Casal J, Sánchez R (2000) Antagonistic action of low-fluence and high-irradiance modes of response of phytochrome on germination and b-mannanase activity in Datura ferox seeds. J Exp Bot 347:1127–1133

Finkelstein R, Reeves W, Ariizumi T, Steber C (2008) Molecular aspects of seed dormancy. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59:387–415

Griffith M, Timonin M, Wong ACE, Gray GR, Akhter SR, Saldanha M, Rogers MA, Weretilnyk EA, Moffatt B (2007) Thellungiella: an Arabidopsis-related model plant adapted to cold temperatures. Plant Cell Environ 30:529–538

Gul B, Weber DJ (1999) Effect of salinity, light, and thermopheriod on the seed germination of Allenrolfea occidentails. Can J Bot 77:1–7

Gul B, Ansari R, Flowers TJ, Khan MA (2013) Germination strategies of halophyte seeds under salinity. Environ Exp Bot 92:4–18

Guo YH, Jia WJ, Song J, Wang DA, Chen M, Wang BS (2012) Thellungilla halophila is more adaptive to salinity than Arabidopsis thaliana at stages of seed germination and seedling establishment. Acta Physiol Plant 34:1287–1294

Inan G, Zhang Q, Li P, Wang Z, Cao Z, Zhang H, Zhang C, Quist TM, Goodwin SM, Zhu J, Shi H, Damsz B, Charbaji T, Gong Q, Ma S, Fredricksen M, Galbraith DW, Jenks MA, Rhodes D, Hasegawa PM, Bohnert HJ, Joly RJ, Bressan RA, Zhu JK (2004) Salt cress: a halophyte and cryophyte Arabidopsis relative model system and its applicability to molecular genetic analyses of growth and development of extremophiles. Plant Physiol 135:1718–1737

Jacobsen JV, Pearce DW, Poole AT, Pharis RP, Mander LN (2002) Abscisic acid, phaseic acid and gibberellin contents associated with dormancy and germination in barley. Physiol Plant 115:428–441

Jin M, Zhang R, Sun L, Gao Y (1999) Temporal and spatial soil water management: a case study in the Heilonggang region, PR China. Agr Water Manage 42:173–187

Kant S, Kant P, Raveh E, Barak S (2006) Evidence that differential gene expression between the halophyte, Thellungiella halophila, and Arabidopsis thaliana is responsible for higher levels of the compatible osmolyte proline and tight control of Na+ uptake in Thalophila. Plant Cell Environ 29:1220–1234

Kant S, Bi YM, Weretilnyk E, Barak S, Rothstein SJ (2008) The Arabidopsis halophytic relative Thellungiella halophila tolerates nitrogen-limiting conditions by maintaining growth, nitrogen uptake, and assimilation. Plant Physiol 147:1168–1180. doi:10.1104/pp.108.118125

Karssen CM (1982) Seasonal patterns of dormancy in weed seeds. In: Khan AA (ed) The physiology and biochemistry of seed development, dormancy and germination. Elsevier Biomedical Press, Amsterdam, pp 243–270

Katembe WJ, Ungar IA, Mitchell JP (1998) Effect of salinity on germination and seedling growth of two Atriplex species (Chenopodiaceae). Ann Bot 82:167–175

Khan MA, Gul B (2002) Some ecophysiological aspects of seed germination in halophytes. In: Liu X, Liu M (eds) Halophytes utilization and regional sustainable development of agriculture. Meteorological Press of China, Beijing, pp 59–68

Khan MA, Gul B, Weber DJ (2001a) Germination of dimorphic seeds of Suaeda moquinii under high salinity stress. Aust J Bot 49:185–192

Khan MA, Gul B, Weber DJ (2001b) Seed germination characteristics of Halogeton glomeratus. Can J Bot 79:1189–1194

Kigel J (1995) Seed germination in arid and semi-arid regions. In: Kigel J, Galili G (eds) Seed development and germination. Marcel Dekker, New York, pp 645–699

Koornneef M, Bentsink L, Hilhorst H (2002) Seed dormancy and germination. Curr Opin Plant Biol 5:33–36

Kusumoto D, Yoneyama K, Yoneyama K, Joel DM, Takeuchi Y (2006) Effects of fluridone and norflurazon on conditioning and germination of Striga asiatica seeds. Plant Growth Regul 48:73–78

Li W, Liu X, Khan MA, Yamaguchi S (2005) The effect of plant growth regulators, nitric oxide, nitrate, nitrite and light on the germination of dimorphic seed of Suaeda salsa under saline conditions. J Plant Res 118:207–214

Li W, An P, Liu X, Khan MA, Tsuji W, Tanaka K (2008) The effect of light, temperature and bracteoles on germination of polymorphic seeds of Atriplex centralasiatica Iljin under saline conditions. Seed Sci Technol 36:325–338

Mass EV, Grieve CM (1994) Tiller development in salt-stressed wheat. Crop Sci 34:1594–1603

Mass EV, Poss JA (1989) Salt sensitivity of cowpea at various growth stages. Irrig Sci 10:313–320

Milberg P, Andersson L, Thompson K (2000) Large-seeded species are less dependent on light for germination than small-seeded ones. Seed Sci Res 10:99–104

Negbi M, Koller D (1964) Dual action of white light in the photocontrol of germination of Oryzopsis miliacea. Plant Physiol 39:247–253

Oh DH, Dassanayake M, Haas JS, Kropornika A, Wright C, d’Urzo MP, Hong H, Ali S, Hernandez A, Lambert GM, Inan G, Galbraith DW, Bressan RA, Yun DJ, Zhu JK, Cheeseman JM, Bohnert HJ (2010) Genome structures and halophyte-specific gene expression of the extremophile Thellungiella parvula in comparison with Thellungiella salsuginea (Thellungiella halophila) and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 154:1040–1052. doi:10.1104/pp.110.163923

Pang QY, Chen SX, Dai SJ, Chen YZ, Wang Y, Yan XF (2010) Comparative proteomics of salt tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana and Thellungiella halophila. J Proteome Res 9:2584–2599. doi:10.1021/pr100034f

Pedras MSC, Zheng QA (2010) Metabolic responses of Thellungiella halophila/salsuginea to biotic and abiotic stresses: metabolite profiles and quantitative analyses. Phytochemistry 71:5–6. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.12.008

Saika H, Okamoto M, Miyoshi K, Kushiro T, Shinoda S, Jikumaru Y, Fujimoto M, Arikawa T, Takahashi H, Ando M, Arimura S, Miyao A, Hirochika H, Kamiya Y, Tsutsumi N, Nambara E, Nakazono M (2007) Ethylene promotes submergence-induced expression of OsABA8ox1, a gene that encodes ABA 8′-hydroxylase in rice. Plant Cell Physiol 48:287–298

Schutz W, Milberg P, Lamont BB (2002) Seed dormancy, after-ripening and light requirements of four annual Asterace in South-western Australia. Ann Bot 90:704–717

Shichijo C, Katada K, Tanaka O, Hashimoto T (2001) Phytochrome A-mediated inhibition of seed germination in tomato. Planta 213:764–769

Shinomura T, Nagatani A, Chory J, Furuya M (1994) The induction of seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana is regulated principally by phytochrome B and secondarily by phytochrome A. Plant Physiol 104:363–371

Shinomura T, Nagatani A, Hanzawa H, Kubota M, Watanabe M, Furuya M (1996) Action spectra for phytochrome A- and B-specific photoinduction of seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:8129–8133

Song J, Feng G, Tian C, Zhang F (2005) Strategies for adaptation of Suaeda physophora, Haloxylon ammodendron and Haloxylon persicum to a saline environment during seed-germination stage. Ann Bot 96:399–405

Thompson K (1989) A comparative study of germination responses to high irradiance light. Ann Bot 63:159–162

Thompson K, Grime JP (1983) A comparative study of germination responses to diurnally-fluctuating temperatures. J Appl Ecol 20:141–156

Ungar IA (1979) Seed dimorphism in Saliconia europaea L. Bot Gaz 140:102–108

Ungar IA (1995) Seed germination and seed-bank ecology in halophytes. In: Kigel J, Galili G (eds) Seed development and germination. Marcel Dekker, NewYork, pp 629–644

Varbanova M, Yamaguchi S, Yang Y, McKelvey K, Hanada A, Borochov R, Yu F, Jikumaru Y, Ross J, Cortes D, Ma CJ, Noel JP, Mander L, Shulaev V, Kamiya Y, Rodermel S, Weiss D, Pichersky E (2007) Methylation of gibberellins by Arabidopsis GAMT1 and GAMT2. Plant Cell 19:32–45

Wu HJ, Zhang Z, Wang JY, Oh DH, Dassanayake M, Liu B, Huang Q, Sun HX, Xia R, Wu Y, Wang YN, Yang Z, Liu Y, Zhang W, Zhang H, Chu J, Yan C, Fang S, Zhang J, Wang Y, Zhang F, Wang G, Lee SY, Cheeseman JM, Yang B, Li B, Min J, Yang L, Wang J, Chu C, Chen SY, Bohnert HJ, Zhu JK, Wang XJ, Xie Q (2012) Insights into salt tolerance from the genome of Thellungiella salsuginea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:12219–12224. doi:10.1073/pnas.1209954109

Yamaguchi S, Kamiya Y (2002) Gibberellins and light-stimulated seed germination. J Plant Growth Regul 20:369–376

Yamauchi Y, Ogawa M, Kuwahara A, Hanada A, Kamiya Y, Yamaguchi S (2004) Activation of gibberellin biosynthesis and response pathways by low temperature during imbibition of Arabidopsis thaliana seeds. Plant Cell 16:367–378

Zeng L, Shannon MC, Grieve CM (2002) Evaluation of salt tolerance in rice genotypes by multiple agronomic parameters. Euphytica 127:235–245

Zheng Y, Gao Y, An P, Shimizu H, Rimmington GM (2004) Germination characteristics of Agriophyllum squarrosum. Can J Bot 82:1662–1670

Zheng Y, Rimmington GM, Gao Y, Jiang L, Xing X, An P, El-Sidding K, Shimizu H (2005) Germination characteristics of Artemisia ordosica (Asteraceae) in relation to ecological restoration in northern China. Can J Bot 83:1021–1028

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Dr. Mohan C. Saxena for revision of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Khan, M.A., Yamaguchi, S. et al. Hormonal and environmental regulation of seed germination in salt cress (Thellungiella halophila). Plant Growth Regul 76, 41–49 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-014-0007-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-014-0007-9