Abstract

Crime and fear of crime are significant aspects of daily life and the occurrence of crime shows strong spatio-temporal variations. The valley of Kashmir is facing political instability, while violation of human rights has become a daily routine. However, women face more atrocities than men. Braid chopping is a new phenomenon of violence against women. The incidents of braid chopping started suddenly on 5 September 2017 and ended on 22 October 2017. In the present study, we have analysed spatio-temporal pattern of braid chopping incidents in order to understand whether the reported cases are randomly distributed across the valley or if there are geographical clusters of these incidents. Kernel density was worked out to make hotspots of the crime apparent on the map. We have identified two major hotspots of braid chopping, one in south Kashmir i.e. district Kulgam and the other in south western parts of Srinagar. This is a pioneering research attempt to represent a case study of braid chopping and also the first research article to carry out such type of work in GIS environment. The GIS maps generated in this study can helps authorities to carry out investigation in the identified areas instead of spreading resource to the entire valley.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Crimes against women are on the rise, along with crime in general (Mukherjee et al. 2001). Crimes against women have roots in male dominated socio-economic, legal and political order (Verma 1990). Assaults on women are often visibly associated with their social status, their communal, ethnic and caste identities (Mukherjee et al. 2001). Although women may be victims of any of the general crimes such as ‘murder’, ‘robbery’, ‘cheating’, etc. only the crimes which are directed specifically against women i.e. gender specific crimes are characterised as ‘Crimes against Women’ (NCRB 2015). According to Article 1 of United Nations Declaration, Violence against Women is to be defined as:

Any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivations of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life (UN 1993).

Traditional Kashmir society was patriarchal and patrilocal (Shafi 2002), i.e. the couple lives with the husband’s family. Although the practices of infanticide, foeticide, and dowry deaths were not resorted to, women were generally abused, maltreated, subjugated and physically victimized right from their childhood because of the socially structured inequality (Akhtar 2013). However, the family patterns are changing significantly and so are the traditionally defined roles of women (Shafi 2002). However, the changing social structure, which exposed the Kashmiri women (belonging to all social strata) to outside world, has made them more vulnerable to all types of sexual abuse. They are subjected to the abuses like sexual harassment, molestation, eve-teasing and even to immoral trafficking, kidnapping, abduction and rape. Especially during the conflict situation in Kashmir a striking increase in the sexual violence against women has been witnessed. While entire communities suffer the consequences of armed conflict and terrorism, women and girls are particularly affected because of their status in society and their sex (Akhtar 2013).

The state of Jammu and Kashmir is a perpetual zone of conflict between India and Pakistan. The Kashmir Valley, a Muslim dominated area of the state, has been witnessing a lot of violence in recent years; however, women bear the scars of violence deeper than men and face all kinds of injustices and crimes (Dabla 2009). Braid chopping is a new disturbing episode of crime in which culprits have used a pair of scissors or a sharp knife to trim or shave the hair locks of the women in the valley. Therefore it seems that the idea of culprits behind braid chopping is to humiliate, embarrass and terrify women. The police claim that it began on 6 September 2017, when a woman’s braid was cut for the first time in south Kashmir, later it diffused to other parts and more than 100 such incidents were registered (Thapar 2017). These incidents created fear among the female population who were scared to step out of their houses and some even stopped attending schools and other work places. It also resulted in protests across the region resulting in violent clashes between people and government forces (Tamim 2017). The level of chaos, confusion, anger and anxiety of people can be gauged from the fact that in Baramulla district an innocent boy was severely beaten by an angry mob, accusing him of being a braid chopper. After proper investigation, it was found that he was not a braid chopper. In another case in Pulwama district, four laborers, hailing from Bihar were violently thrashed by a mob for being alleged braid choppers, later it was found that they had some dispute with their boss over wages and had nothing to do with braid chopping. In another incident four foreign tourists, who were on evening walk along the banks of famous Dal Lake in Srinagar city, were perceived as braid choppers by locals and fortunately police intervened at right time and rescued them (Hakeem 2017; India Today 2017). In order to tackle the menace, Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) Police constituted special investigation team to probe these incidents and also announced a reward of INR 6 lakh to one who would arrest or help in arresting the braid choppers.

Crime and fear of crime are significant aspects of daily life and the occurrence of crime shows strong spatio-temporal variations. Human geographers try to do mapping and explain patterns of crime occurrence (Fyfe 2000). However, the diffusion of sophisticated GIS techniques has further enhanced their capabilities to provide critical inputs for policy implications. Braid chopping has occurred randomly over space in Kashmir Valley, which makes it a fit case to be investigated in GIS environment and facilitate mapping of its occurrence in spatio-temporal context. In the present study, we have used GIS based methodology to understand spatio-temporal pattern of braid chopping in Kashmir Valley and have also done hotspot analysis, to make crime areas very much discernable on the map. The key idea behind the hotspot analysis is to identify areas where the number of crime occurrence is disproportionately higher than other parts of the region. It will help the authorities to carry out investigation in the identified hotspots, instead of spreading resources to the entire region. For example, Sherman et al. (1998) showed areas which are in need of deployment of additional police forces to better respond to the crime areas (Figs. 1, 2).

A Kashmiri Women Displays her Chopped Braid. Source: https://www.hindustantimes.com/columns/what-is-one-to-make-of-the-braid-chopping-panic-in-kashmir/story-rX4Wpc3UZc9EWgkuBj18eJ.html

Students Protesting against Braid Chopping in Kashmir. Source: https://kashmirlife.net/stop-braid-chopping-i-protest-kgp-students-hold-protests-153033/

Violence against women and its geography

There is one universal truth, applicable to all countries, cultures and communities: violence against women is never acceptable, never excusable, and never tolerable. -United Nations Secretary General, Ban Ki-Moon (UNDPI 2008).

Violence against women is not a new phenomenon, nor are its consequences to women’s physical, mental and reproductive health. It is a global public health problem that affects approximately one third of women globally (WHO 2013). The World Bank (1993) estimated that in developing countries rape and domestic violence reduce the healthy years of life for reproductive age women by 5%. Female-focused violence also represents a hidden obstacle to economic and social development. By sapping women’s energy, undermining their confidence, and compromising their health, gender violence deprives society of women’s full participation (Heise 1994). The United Nations Fund for Women (UNIFEM) also observed, “Women cannot lend their labor or creative ideas fully if they are burdened with the physical and psychological scars of abuse” (Carrillo 1992).

In different countries and at different times there may be focus on only certain forms of violence as violence against women. For example, in the United Kingdom the term violence against women has in the past decade come to represent mainly domestic violence (Hester 2004). The most pervasive form of gender violence is abuse of women by intimate male partners (Heise 1994). Although spousal physical violence is a near universal phenomenon that threatens the health, well-being, rights and dignity of women, it is only recently that it has emerged as a global issue (Jeyaseelan et al. 2007). According to a review in the Journal of the American Medical Association, “Women in the United States are more likely to be assaulted and injured, raped or killed by a current or ex-male partner than all other assailants combined” (American Medical Association 1992). In countries as diverse as Brazil, Israel, Canada, and Papua New Guinea, over half of all women murdered are killed by a current or former partner (Heise et al. 1994). In India, despite the tremendous impact it has on the woman, her family and society, domestic violence continues to be a ‘crime of silence’ (Pillai 2001). One of its expressions is the dowry system through which women are oppressed or even tortured and killed (Rastogi and Therly 2006). There were 1319 cases of dowry deaths reported nationally in 1986 (Times of India 1988). However, in year 2015 the number reached 7634 (Table 1) i.e. an increase of 478% in 29 years.

In India crimes against women are classified under two broad categories:

- 1.

Crime Heads under the Indian Penal Code (IPC)

- 2.

Crime Heads under the Special & Local Laws (SLL)

The problem of gender-based violence runs very deep in India. They start with the practice of sex-selective abortion and infanticide, and continue through adolescent and adult life with high levels of female infant mortality, child marriage, teenage pregnancy, lesser wages for women, unsafe workplaces, domestic violence, maternal mortality, sexual assault and neglect of elderly women (Himabindu et al. 2014). Crimes against women are on an increase with each passing year (Table 1). Ranging from the so-called eve teasing and outright sexual harassment on the street or workplace, to harassment for dowry, molestation in public transport vehicles, and the often-reported rape, these crimes against women reflect the vulnerability and deep-rooted problems related to the position of women in Indian society (Himabindu et al. 2014). As per the NCRB (2015) report, cruelty by husband or his relatives and assault on women with intent to outrage her/their modesty, represent the largest percentage i.e. 36% and 26% of all crimes under IPC in year 2015. The NCRB statistics show that the total reported cases of rape in 2015 were 34,651. In India women become targets of violence even before birth. Sex selective abortions have become a significant social phenomenon in several parts of India. It transcends all castes, class and communities and even the North–South dichotomy (Tandon and Sharma 2006). Diaz (1988) states that in a well-known Abortion Centre in Mumbai, after undertaking the sex determination tests, out of the 15,914 abortions performed during 1984–1985 almost 100% were those of girl foetuses.

The occurrence of crime shows strong spatio-temporal variations. Human geographers try to do mapping and explain patterns of crime occurrence (Fyfe 2000). In order to better understand the geographical extent of crime against women, many important studies have been carried out to understand the spatial context, e.g. Pawson and Banks (1993) studied the geography of rape in New Zealand and the distribution of fear and violence, concluding that younger women find private spaces less safe than public spaces. They also suggested that those people most at risk of rape i.e. younger women had a clear understanding of its geography. Canter and Larkinms (1993) modeled the spatial activities of sex offenders. They noted that there is no relationship between crime location and the residence of offenders. While Kocsis and Irwin (1997) focused on spatial patterns in serial violence, Vetten (1998) investigated the possible effect of urban design upon women right violation. Amin, et al. (2015) while studying the geographical clusters of rape in the United States identified geographical areas with exceptionally high (low) rates of reported rape. They concluded that the identified geographical problem areas were prime candidates for more intensive preventive counseling and criminal prosecution efforts by public health, social service, and law enforcement agencies. Thornton and Voigt (2007) studied the possible impact of Hurricane Katrina on the rates of violent crimes against women in New Orleans. Warren et al. (2010) analyzed crime scene and distance correlates of serial events. Weisburd and Braga (2006) noted that identification of hotspot crime areas leads to more criminal arrests. Similarly, Sherman et al. (1998) showed areas which were in need of deployment of additional police forces to better respond to the crime areas. According to Eck et al. (2005), the hotspot analysis method assumes that not criminals but locations of crime occurrences must be mapped, thus understand why certain locations are more prone to criminal activities than others in the same area.

However, little research has been carried out regarding violence against women in Kashmir. Few studies that can be cited like, Bilal and Gul (2015) attempted to highlight various types of violence against women in Jammu and Kashmir caused by militancy and armed conflict. Naik (2015) has presented a summary profile of atrocities and assaults committed against women from 1989 to 2011 in Kashmir Valley. This is probably the first research article regarding braid chopping of women in Kashmir. The interesting thing related to these incidents is that they started suddenly on 5 September 2017 and ended suddenly on 22 October 2017. We have carried out a GIS based spatio-temporal and hotspot analysis of braid chopping incidents in Kashmir, to understand their pattern of occurrence and identify the areas where the crime rate was disproportionately higher than other areas.

Study area

Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) is India’s northern most state. The state of J&K strategically located in the north-west corner of India, shares borders with China in the east, Pakistan in the north west and plains of Punjab and Himachal in the south and south-east. The Indian part of Kashmir has three divisions: Jammu in the south, Ladakh in the northeast, and Kashmir Valley in the center. Muslims are the majority population in the Vale and Sikhs and Hindus are in minority. After the partition of Indian sub-continent in 1947, the accession of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) to India happened immediately. Both India and Pakistan have their own narratives regarding legitimate right over the state, making the state a zone of perpetual conflict and the women of Kashmir have suffered endlessly (Khan 2015; Ray 2009).

Akhtar (2013) notes that while entire communities suffer the consequences of armed conflict and terrorism, women and girls are particularly affected because of their status in society and their sex. Several national as well as international human rights bodies blame AFSPA for this pathetic human rights situation, which grants a virtual amnesty to the perpetrators (Rabbani 2011). In 1990, Kashmir was declared a “disturbed” area by virtue of which it became subject to the provisions of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA). This particular piece of legislation arms the State with extraordinary powers. It allows the security forces untrammelled power in “disturbed” areas without the safeguards applicable in states of emergency: the right to life is suspended and security forces have the right to shoot to kill civilians; arrest or detain civilians without warrant; enter and search homes, and destroy homes and property (Kazi 2014). According to a 1994 United Nations publication (E/CN.4/1995/42: 63–69), during 1992 alone 882 women were reportedly gang raped by Indian security forces in J&K. Some estimates put the number of incidents of rapes at 20,000 during the last 21 years since 1989. About 100 women including minors and the elderly were raped in the year 1991 alone (Independent People’s Tribunal 2010: 60) (Rabbani 2011). The mass rapes of Kashmiri women in the 1990s in the twin hamlets of Kunan-Poshpora where 31 women between the ages of 8 and 80 were raped become intelligible as systematic patriarchal gendered strategies of occupation by the Indian army in Kashmir to humiliate an entire community (Kazi 2014). It is almost impossible to lodge a complaint against men in the police and the armed forces, or in government services (Mukherjee et al. 2001).

According to the NCRB Report (2015), the total number of reported cases of Crimes against Women during 2015 was 3363 i.e. around 1% of the total cases reported in the country. Of these 296 cases of rape were reported, constituting 8.8% of total crimes in the state. Also, 1071 cases of kidnapping and abduction & 244 cases of sexual harassment were reported. However, the reported cases of dowry deaths were only 6, while the national average is around 212 deaths. There were no cases of immoral trafficking or incest rapes in the state in 2015. Braid chopping is a new wave of violence against women in Kashmir Valley which has terrified the entire population. By the end of October 2017, there were more than 150 cases of braid chopping in the state (Fig. 3).

Materials and methods

In this article, we have used geospatial tools and socio-economic data to investigate the spatio-temporal pattern of braid chopping incidents in Kashmir Valley. The study area was delineated using Survey of India toposheets for the year 1971 at 1:50,000 scale. These toposheets were first scanned and then imported in the Esri’s ArcGIS 10.3 software. These toposheets were individually geo-referenced in the same software and mosaic together to carve out the study area. In order to develop the base map for this study, village level map of Kashmir Valley was obtained from Census Handbook (2011) which was geo-referenced and integrated with Survey of India toposheet (1971). The information regarding braid chopping incidents was retrieved from the daily newspapers, published in both Urdu and English across the Valley. However, the newspapers published only those incidents for which FIR was registered with the police department. The braid chopping incidents are shown as point data on the map and other information like name of victim, residence, age, sex, date and time of occurrence of the event were added in the attribute table in AcrGIS. The integration of these data sets facilitated spatial analysis and development of data layers like age of victim, time and date of crime occurrence and location of crime.

The kernel density estimation was used to produce hotspot map of braid chopping. The growing availability of KDE in popular GIS applications, the perceived accuracy of its hotspot identification, and the aesthetically pleasing and easily understandable output are among the driving forces behind its popularity (Hart and Zandbergen 2014). Ainsworth (2001) notes, “A crime hot-spot is usually understood as a small area with boundaries clearly identified, where there is an increase in concentration of criminal incidents in a given period of time”. Hot spot analysis is the most common method used in criminal interpretations. It assumes that past crime locations will persist into the future, however the actual results of this method depend on the time period under review. By and large, this robust method only produces good results when applied to short time period (Anselin 2000). This type of methodology is fit for our study because the menace of braid chopping started suddenly on 5 September 2017 and ended suddenly on 22 October 2017 in a short span of time. Besides, we investigated how these incidents cluster in spatio-temporal context for which GIS technologies provide powerful toolset (Sherman et al. 1998; Livingston 2008; Bell and Schuurman 2010; Walker, et al. 2014), to draw useful conclusions for investigation and implementation of counter measure policies.

Results and discussion

Spatio-temporal diffusion of braid chopping in Kashmir Valley

The braid chopping incident was first reported in mid of June, 2017, in Rajasthan’s Jodhpur district (India Today 2017; ABP News 2017). As this incident went viral on media to almost every part of India, especially in the northern states like Delhi, Bihar, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Indian Administered Kashmir (Mukherjee 2017; Dey 2017), it left people frightened and terrified. By this time, the braid chopping incidents reached Jammu division of Jammu and Kashmir and there were no reports of braid chopping from other Indian states. Similarly, when it reached Kashmir Valley, it completely disappeared from Jammu division. However there is an interesting spatio-temporal pattern of braid chopping incidents in Kashmir Valley. Initially the incidents occurred in backward rural areas of the valley. Their narratives were mostly considered superstitious, being reported from countryside, where people are generally simple. However, when these cases reached the urban areas of valley, the stories changed and it sparked fear and anger among locals. People start blaming the government for not acting quickly and positively, which triggered clashes between locals and government forces.

So far as the spatio-temporal distribution is concerned, the first incident was reported on 5th September 2017 from Kokernag area, district Anatnag (Suhail 2017; Ahmad 2017) located in south of Kashmir as shown in the Fig. 4. After 19th September 2017, cases were reported from central Kashmir, particularly from Srinagar i.e. the capital city. The braid chopping incidents started proceeding like a wave towards the center of the Valley. After 26th September 2017, it reached north Kashmir particularly Baramulla and Bandipora districts. Figure 4 clearly shows that the first case of was reported from south Kashmir and the last one from north Kashmir, therefore, the general trend of braid chopping was from south to north Kashmir. More than 100 cases were reported from the valley. The women claimed that attackers sprayed chemicals on their faces and left them unconscious. Upon waking up, they found their hair chopped off (Tamim 2017). The confusion and chaos was so high that somewhere police personnel, laborers from outside the state or mentally retarded people were wrongly blamed as culprits and they became targets of anger (Fayaz 2017). It is also pertinent to mention that on October 6 2017, six foreign tourists: three Australians and one each from South Korea, Ireland and England had a narrow escape in Srinagar when locals mistook them as braid choppers; fortunately police rescued them at right time (Ahmad 2017).

The braid chopping incidents were reported from almost all the districts of Kashmir (Fig. 5). Srinagar and Kulgam, each accounted for more than 20 incidents. However, Shopian, Bandipora and Kupwara recorded the lowest number of incidents. Figure 5 suggests that there were no violence-free areas in the Valley, but south Kashmir was the worst affected. This area has also witnessed a spurt in terror activities recently (Yasir 2017; Livemint 2017; Chakravarty and Naqash 2016). However, there seems no relationship between presence of militancy in the area and occurrence of braid chopping incidents. For example, Shopian district, a hotspot of militancy in Kashmir, witnessed only 3 such incidents. Srinagar, the summer capital of the state usually a peaceful area where militancy is negligible, witnessed highest number of braid chopping incidents.

Age group of victims

It is clear from Fig. 6 that almost all age groups were victimized in the valley. However, women of age group 15–29 were targeted more than any other group. The reason could be that the population of Kashmir is composed mostly of juvenile age group (Census 2011). Moreover, young women have always experienced significantly higher rate of physical violence than women in older age groups (UNFPA 2010; ABS 2016).

Time of braid chopping occurrence

Most of the incidents were attempted during evening (Fig. 7). The fear of braid chopping prevented most people from travelling outside their homes after dusk which made movement of culprits easy during evening. The braid choppers took advantage of darkness and managed to flee from the crime spot easily. However, only a few incidents took place during night time because people mostly remained inside their homes and rarely moved out. It is also evident that a good number of incidents occurred during day time because men moved out for work, leaving behind women members of the family alone, that proved soft targets for the criminals. Some events have also occurred in the morning time because of very limited movement of people on streets and roads in the early morning time.

Hotspots of braid chopping in Kashmir Valley

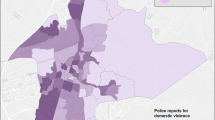

The kernel density of braid chopping incidents was worked out to identify geographical areas with exceptionally high rates of the crime. The major hotspot developed south west of Srinagar city where rate of braid chopping was highest, including Batmaloo, Bemina, Nowgam, Hyderpora, Kralpora and Sanatnagar areas. The second important hotspot developed in southern portion of Kashmir Valley in district Kulgam. While as other districts had small hot spots. All these clusters of braid chopping have Z score < 1, means statistically significant at 99% confidence interval. The key purpose behind the hot-spot analysis is to identify areas where the occurrence of a crime is disproportionately higher than other areas of a city or region. For example, Sherman et al. (1998) used hotspot analysis method, showing areas which are in need of deployment of additional police forces to better respond to the crime. Identification of hotspot crime areas also leads to more criminal arrests (Weisburd and Braga 2006). According to Eck, J. et al. (2005), the hotspot analysis method assumes that we must map the location of crime occurrences and not criminals, in order to understand why certain locations are more prone to criminal activities than others in the same area. This type of mapping can immensely assist police to carry out the investigation and response to solve serial crimes (Wortley and Mazerolle 2008) (Fig. 8).

Conclusion

Putting crime data into GIS and creating a map with clear visualization and purpose is the starting point of crime analysis in many cases. Once the location of crime occurrence is identified, half the problem is solved for different stakeholders, especially administrators, police personnel, civil society, planners and researchers. More resources can be deployed in such locations, to increase response capacity and stop the crime from happening in the first place. Besides, it assists in understanding the spatial characteristics of the problem areas only, instead of focusing on and allocating resources haphazardly to the entire region.

The purpose of the present study was to analyse spatio-temporal pattern of braid chopping incidents in Kashmir Valley in order to understand whether the reported cases are randomly distributed or if there are geographical clusters of these incidents. The most important outcome of this study is the identification of hotspot areas of braid chopping in the valley. There is an interesting spatio-temporal pattern of braid chopping incidents in Kashmir Valley. Initially the incidents occurred in backward rural areas of the valley. Gradually they spread to the urban areas. The general trend of braid chopping was from south to north Kashmir. There were no violence-free areas in the Valley, but south Kashmir was the worst affected. Srinagar, the summer capital of the state witnessed highest number of braid chopping incidents. The major hotspot developed south west of Srinagar city where rate of braid chopping was highest, including Batmaloo, Bemina, Nowgam, Hyderpora, Kralpora and Sanatnagar areas. The second important hotspot developed in southern portion of Kashmir Valley in district Kulgam. While as other districts had small hot spots. Young women were targeted more than any other group, since young women have always experienced significantly higher rate of physical violence than women in older age groups (UNFPA 2010; ABS 2016).

The administration needs to deploy additional manpower, in terms of police personnel and investigation teams, to carryout intensive counter measures, instead of spreading manpower over a large area and spending too much of time and resources. We have identified geographical areas with exceptionally high intensity of reported cases. Geographical clusters with high rates of braid chopping are prime areas of concern for administration and civil society.

Who is the real culprit behind the crime? This is a very intriguing question, but in light of this research only recommendations can be made to reduce the occurrence of such crimes in future. Following are some of the proposed solutions for this and other such crime cases:

- 1.

Patrolling by police and local youth in identified crime areas.

- 2.

Another solution could be the installation of CCTVs, in both rural and urban areas, to track the movement of culprits.

- 3.

Women should be trained to use nonlethal substance like chilies over attacker and other self-defense techniques.

- 4.

Another important solution could be to keep trained dogs in home for watch and ward.

The final results of this research can be vital to devise an effective police strategy. The present study suggests that there is an immediate need to carry out in-depth research regarding the social, economic, political and cultural components of given areas to identify the reasons for the occurrence this crime. While this is the first study regarding women braid chopping, the methodology and baseline GIS data generated can effectively enrich research efforts for other crimes in this conflict zone and outside.

References

ABP News. (2017). Retrieved 22 August, 2017. http://abpnews.abplive.in/videos/viral-sach-is-there-a-witch-who-chops-off-people-s-hair-while-they-are-asleep-642035.

Ahmad, S. (2017). First mysterious hair cutting incident in Kashmir. Kashmir observer. https://kashmirobserver.net/breaking-news/22640. Accessed 16 January, 2018.

Ainsworth, P. B. (2001). Offender profiling and crime analysis. Devon: William Publishing.

Akhtar, C. (2013). Eve teasing as a form of violence against women: A case study of District Srinagar, Kashmir. International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology,5(5), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJSA2013.0445.

American Medical Association/Council on Scientific Affairs. (1992). Violence against women: Relevance for medical practitioners. Journal of the American Medical Association,267, 3184–3189.

Amin, R., et al. (2015). Geographical clusters of rape in the United States: 2000–2012. Statistics and Public policy,2(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/2330443X.2015.1092899.

Anselin, L., et al. (2000). Spatial analyses of crime. Criminal Justice, 4, 21–23.

Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS). (2016). Personal safety survey. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4906.0. Accessed 18 January, 2018.

Bell, N., & Schuurman, N. (2010). GIS and injury prevention and control: History, challenges, and opportunities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,7, 1002–1017.

Bilal, S., & Gul, A. (2015). Women and violence: A study of women’s empowerment and its challenges in Jammu and Kashmir. Reviews of Literature,2(7), 1–9.

Canter, D., & Larkin, P. (1993). The environmental range of serial rapists. Journal of Environmental Psychology,13, 63–69.

Carrillo, R. (1992). Battered dreams: Violence against women as an obstacle to development. New York: United Nations Fund for Women.

Census. (2011). Population of Jammu and Kashmir, India. http://www.ccensusofindia.com//index.html. Accessed 17 January, 2018.

Chakravarty, I., & Naqash, R. (2016). What makes South Kashmir fertile ground for militancy? Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/811419/what-makes-south-kashmir-fertile-ground-for-militancy. Accessed 17 January, 2018.

Dabla, B. A. (2009). Violence against women in Kashmir. Retrieved from http://www.kashmirlife.net/violence-against-women-in-kashmir-369/. Accessed 18 January, 2018.

Dey, A. (2017). A mysterious “braid-chopper” is cutting off women’s hair in northern India. quartz India. https://qz.com/1046374/a-mysterious-braid-chopper-is-cutting-off-womens-hair-in-northern-india/. Accessed 16 January, 2018.

Diaz, A. A. (1988). Amniocentesis and Female Foeticide. Bulletin of the Indian Federation of Medical Guild, 56, 41–47

Eck, J., Chainey, S., Cameron, J., Leitner, M., & Wilson, R. (2005). Mapping crime: Understanding hot spots. Washington: National Institute of Justice.

Fayaz, K. (2017). Braid chopping: Mass hysteria or planned conspiracy? WANDE Magazine. http://www.wandemag.com/braid-chopping-hysteria-conspiracy/.

Fyfe, N. (2000). Geography of crime. In R. Johnston, D. Gregory, G. Pratt, & M. Watts (Eds.), Dictionary of human geography (4th ed., pp. 120–123). Oxford: Blackwell.

Hakeem, I. (2017). Braid chopping incidents taking political turn in Kashmir, the Economic times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/braid-chopping-incidents-taking-political-turn-in-kashmir/articleshow/60950819.cms. Accessed 18 January, 2018.

Hart, T. C., & Zandbergen, P. A. (2014). Kernel density estimation and hotspot mapping: Examining the influence of interpolation method, grid cell size, and bandwidth on crime forecasting. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management,37(2), 305–323. https://doi.org/10.1108/pijpsm-04-2013-0039.

Heise, L. (1994). Gender-based abuse: The global epidemic. Cad. Saúde Públ.,10(supplement 1), 135–145.

Heise, L., Pitanguy, A., & Germaine, A. (1994). Violence against women: The hidden health burden. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

Hester, M. (2004). Violence against women. Sage Publications,10(12), 1431–1448. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801204270559.

Himabindu, B. L., Arora, R., & Prashanth, N. S. (2014). Whose problem is it anyway? Crimes against women in India. Global Health Action,7(1), 23718. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.23718.

India Today. (2017). Mystery of braid chopping: How mass hysteria travelled from Rajasthan to Kashmir. https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/braid-chopping-mystery-mass-hysteria-rajasthan-kashmir-H1067908-2017-10-20. Accessed 17 January, 2018.

Jeyaseelan, L., et al. (2007). Physical spousal violence against women in India: Some risk factors. Journal of Biosocial Science,39(5), 657–670. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021932007001836.

Kazi, S. (2014). Rape, impunity and justice in Kashmir. Socio-Legal Review,10(2014), 14–46.

Khan, K. S. (2015). Discerning women’s discursive frames in CyberKashmir. Contemporary South Asia,23(3), 334–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2015.1040737.

Kocsis, R. N., & Irwin, H. J. (1997). An analysis of spatial patterns in serial rape, arson, and burglary: The utility of the circle theory of environmental range for psychological profiling. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law,4(2), 195–206.

Livemint. (2017). Over 100 militants active in South Kashmir: Army official. http://www.livemint.com/Politics/6xUJOxI49FkPXwwBVGaWGL/Over-100-militants-active-in-south-Kashmir-Army-official.html. Accessed 18 January, 2018.

Livingston, M. (2008). Alcohol outlet density and assault: A spatial analysis. Addiction,103(6), 19–28.

Mukherjee, C., et al. (2001). Crimes against women in India: Analysis of official statistics. Economic and Political Weekly,36(43), 407–408.

Mukherjee, D. (2017). Rajasthan’s scissorhands? Panic in villages after ‘ghost’ chops off women’s hair. http://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/rajasthan-s-scissorhands-panic-in-villages-after-ghost-chops-off-women-s-hair/story-bQ0ZHij1WVQGOeHTPzybaI.html. Accessed 18 January, 2018.

Naik. (2015). Feminine oppression: A study of the conflict in Kashmir. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 2(4), 2349–3429. http://www.ijip.in.

National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). (2015). Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. http://ncrb.nic.in. Accessed 17 January, 2018.

Pawson, E., & Banks, G. (1993). Rape and fear in a New Zealand City. Area,25(2), 55–63.

Pillai, S. (2001). Domestic violence in New Zealand: An Asian immigrant perspective. Economic and Political Weekly,36(11), 965–974.

Rabbani, A. (2011). Jammu & Kashmir and the armed forces special powers act. South Asian Survey,18(2), 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971523113513377.

Rastogi, M., & Therly, P. (2006). Dowry and its link to violence against women in India: Feminist psychological perspectives. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse,7(1), 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838005283927.

Ray, A. (2009). Kashmiri women and the politics of identity. Paper presented to SHUR Final Conference on Human Rights and Civil Society, Rome.

Shafi, A. (2002). Working women in Kashmir: Problems and prospects. New Delhi: APH Publishers.

Sherman, L. W., Gottfredson, D., MacKenzie, D., Eck, J., Reuter, P., & Bushway, S. (1998). Preventing crime: What works, what doesn’t, what’s promising. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice.

Suhail, S. (2017). Fresh case of mysterious ‘braid-chopping’ surfaces in Kokernag, Early Times. http://www.earlytimes.in/newsdet.aspx?q=211868. Accessed 18 January, 2018.

Tamim, B. (2017). Braid-chopping sparks fear and unrest in Kashmir. http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/10/sparks-fear-unrest-kashmir-171012095359240.html. Accessed 18 January, 2018.

Tandon, S. L., & Sharma, R. (2006). Female foeticide and infanticide in India: An analysis of crimes against girl children. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences,1(1), 1–10.

Thapar, K. (2017). What is one to make of the braid chopping panic in Kashmir? Hindustan Times, Oct 14, 2017 16:24 IST. http://www.hindustantimes.com/columns/what-is-one-to-make-of-the-braid-chopping-panic-in-kashmir/story-rX4Wpc3UZc9EWgkuBj18eJ.html.

The United Nations. (1993). Declaration on the elimination of violence against women. San Francisco: General Assembly Resolution.

Thornton, W. E., & Voigt, L. (2007). Disaster rape: Vulnerability of women to sexual assaults during Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Public Management and Social Policy,13(2), 23–49.

Times of India. (1988). January 10. In Willigen, J. V. and Channa, V. C. (1991). Law, custom, and crimes against women: The problem of dowry death in India. Human Organization, 50(4). 0018-7259/91/040369-09.

UNDPI (United Nations Department of Public Information). (2008). News and Media Division. (SG/SM/11437 WOM/1665). New York.

UNFPA. (2010). Gender equality: Calling for an end to female genital mutilation/cutting. Accessed from http://www.unfpa.org/gender/practices1.htm. Accessed 16 January, 2018.

Verma, U. (1990). Crime against women. In S. Sood (Ed.), Violence against women. Jaipur: Arihant Publishers.

Vetten, L. (1998). The rape surveillance project. Agenda Empowering Women for Gender Equity,13(36), 45–49.

Walker, B. B., Schuurman, N., & Hameed, S. M. (2014). A GIS-based spatiotemporal analysis of violent trauma hotspots in Vancouver, Canada: identification, contextualisation and intervention. British Medical Journal Open,4(2), e003642. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003642.

Warren, J. M., Ekelund, U., Besson, H., Mezzani, A., Geladas, N., & Vanhees, L. (2010). Crime scene and distance correlates of serial rape. Journal of Quantitative Criminology,14, 35–59.

Weisburd, D., & Braga, A. (2006). Police innovation: Contrasting perspectives. Cambridge studies in criminolog. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

WHO (World Health Organization). (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence.

World Bank. (1993). World Development Report 1993: Investing in health. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wortley, R., & Mazerolle, L. (2008). Environmental criminology and crime analysis. Milton: Willan Publishing.

Yasir, S. (2017). What is driving south Kashmir’s youth to militancy? Firstpost. http://www.firstpost.com/india/what-is-driving-south-kashmirs-youth-to-militancy-2376980.html. Accessed 18 January, 2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wani, M.A., Shah, S.A., Skinder, S. et al. Mapping crimes against women: spatio-temporal analysis of braid chopping incidents in Kashmir Valley, India. GeoJournal 85, 551–564 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-019-09979-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-019-09979-z