Abstract

The relative financial strength of Islamic banks is assessed empirically based on evidence covering individual Islamic and commercial banks in 19 banking systems with a substantial presence of Islamic banking. We find that (a) small Islamic banks tend to be financially stronger than small commercial banks; (b) large commercial banks tend to be financially stronger than large Islamic banks; and (c) small Islamic banks tend to be financially stronger than large Islamic banks, which may reflect challenges of credit risk management in large Islamic banks. We also find that the market share of Islamic banks does not have a significant impact on the financial strength of other banks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Institutions offering Islamic financial services constitute a significant and growing share of the financial system in a number of countries.Footnote 1 Since the inception of Islamic banking about three decades ago, the number and reach of Islamic financial institutions worldwide has risen from one institution in one country in 1975 to over 300 institutions operating in more than 75 countries (El Qorchi 2005). In Sudan and Iran, the entire banking system is currently based on Islamic finance principles. Islamic banks are concentrated in the Middle East and Southeast Asia, but they are also present as niche players in Europe and the United States. There is currently more than US$800 billion worth of deposits and investments lodged in Islamic banks, mutual funds, insurance schemes (known as takaful), and Islamic branches of conventional banks (Hesse et al 2008).

Reflecting the increased role of Islamic finance, the literature on Islamic banking has grown. A large part of the literature contains comparisons of the instruments used in Islamic and commercial banking, and discusses the regulatory and supervisory challenges related to Islamic banking (e.g., Sundararajan and Errico 2002; Ainley et al. 2007; Sole 2007; Jobst 2007).

There is, however, relatively little empirical analysis of the role of Islamic banks in financial stability.Footnote 2 With the unraveling of the global financial crisis, differences between both commercial and Islamic banks in financial stability have become more important. A number of papers discuss risks in Islamic financial institutions, but do so in theoretical terms instead of through analysis of data, while empirical papers on Islamic banks focus on issues related to efficiency (e.g., Yudistira 2004; Moktar et al. 2006). Although several International Monetary Fund (IMF)/World Bank missions in countries with a substantial presence of Islamic banks have included those banks in the overall financial stability assessments,Footnote 3 the role of Islamic banks in financial stability has not yet been analyzed in a consistent, cross-country, empirical fashion.

This paper attempts to fill the gap in the empirical literature on Islamic banking. To our knowledge, it is the first paper to provide a cross-country empirical analysis of the role of Islamic banks in financial stability. Analyzing the issue in a cross-country context is important because data on Islamic banks in individual countries are not sufficient to distinguish the impact of Islamic banking from the myriad of other factors that have an impact on financial stability. The use of cross-country data requires adjustment for country-specific factors, but this is possible because the methodology employed in this paper dramatically increases the number of observations for the analysis.

Using the z-score as a measure of bank-specific stability, we find for a sample comprising 19 countries, that larger Islamic banks tend to be riskier than smaller Islamic banks and similar large commercial banks, while smaller Islamic banks tend to be more stable than small commercial banks. Furthermore, as the presence of Islamic banks grows in a country’s financial system, there is no significant impact on the soundness of other banks. This suggests that Islamic and commercial banks can co-exist in the same system without substantial “crowding out” effects through competition and deteriorating soundness.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 provides a short overview of the specifics of Islamic banking from a prudential perspective, and discusses the associated risks. Section 3 discusses the methodology, and introduces the variables and data used in the paper (characterized in more detail in Appendix II). Section 4 presents the empirical results. Section 5 summarizes the conclusions, and suggests topics for further research.

2 Specifics of Islamic banking from a prudential perspective

Islamic or Shari’ah-compliant banking can be defined as the provision and use of financial services and products that conform to Islamic religious practices and laws.Footnote 4 In particular, Islamic financial services are characterized by a prohibition against the payment and receipt of interest at a fixed or predetermined rate. Instead, profit-and-loss sharing arrangements (PLS), purchase and resale of goods and services, and the provision of services for fees form the basis of contracts. In PLS modes, the rate of return on financial assets is not known or fixed prior to undertaking the transaction. In purchase-resale transactions, a mark-up is determined based on a benchmark rate of return, typically a return determined in international markets such as LIBOR. A range of Islamic contracts is available depending on the rights of investors in project management and the timing of cash flows. Another feature of Islamic banks is that they are generally prohibited from trading in financial risk (which is seen as a form of gambling) and from financing production or trade in alcoholic beverages or pork, non-Islamic media, and gambling operations.

At the heart of our paper is the question of whether Islamic banks are more or less stable than other banks, in particular conventional commercial banks.Footnote 5 , Footnote 6 A review of the existing literature does not provide a clear-cut answer to this question.

In a recent study, Choong and Liu (2006) argue that Islamic banking, at least as practiced in Malaysia, deviates from the PLS paradigm, and in practice is not very different from conventional banking. The authors therefore suggest that for purposes of financial sector analysis, Islamic banks should be treated similarly to their commercial counterparts.

This is a minority view, however, and may be less relevant for other countries. Most of the relevant literature suggests (using theoretical arguments rather than a formal empirical analysis) that Islamic banks pose risks to the financial system that in many regards differ from those posed by conventional banks. Risks unique to Islamic banks arise from the specific features of Islamic contracts, and the overall legal, governance, and liquidity infrastructure of Islamic finance.

Authors such as Sundararajan and Errico (2002); Iqbal and Llewellyn (2002); and World Bank and International Monetary Fund (2005) note that the following features need to be taken into account when assessing stability in a financial system with a significant presence of Islamic banks:

-

The PLS financing shifts the direct credit risk from banks to their investment depositors, but it also increases the overall degree of risk on the asset side of banks’ balance sheets, as it makes Islamic banks vulnerable to risks normally borne by equity investors rather than holders of debt.

-

Operational risk is crucial in Islamic finance. Operational risk is defined as the risk of losses resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events, which includes but is not limited to, legal risk and Sharī’ah compliance risk. According to the theoretical literature reviewed here, the importance of operational risk in Islamic finance reflects the complexities associated with the administration of PLS modes, including the fact that Islamic banks often have limited legal means to control the agent-entrepreneur.

-

PLS cannot be made dependent on collateral or guarantees to reduce credit risk.

-

Product standardization is more difficult due to the multiplicity of potential financing methods, increasing operational risk and legal uncertainty in interpreting contracts.

-

Islamic banks can use fewer risk-hedging instruments and techniques than conventional banks and traditionally have operated in environments with underdeveloped or nonexistent interbank and money markets and government securities, and with limited availability of and access to lender-of-last-resort facilities operated by central banks. However, the significance of these differences has decreased due to recent developments in Islamic money market instruments and Islamic lender-of-last-resort modes and the implicit commitment to provide liquidity support to all banks during exceptional circumstances in most countries.

-

Non-PLS modes of financing are less risky and more closely resemble conventional financing facilities, but they also carry risks (such as elevated operational risk in some cases) that need to be recognized.

-

Another specific risk inherent in Islamic banks stems from the special nature of investment deposits, whose capital value and rate of return are not guaranteed. Some of the authors quoted above argue that this increases the potential for moral hazard, and creates an incentive for risk taking and for operating financial institutions without adequate capital.

Sundararajan and Errico (2002) and other authors quoted in the previous paragraph argue (but do not empirically test) that this has most likely affected Islamic banks’ competitiveness and resilience to external shocks, with potential systemic consequences. They note that addressing the unique risks of Islamic banking requires adequate capital and reserves, appropriate pricing and control of risks, strong rules and practices for governance, disclosure, accounting, and auditing rules, and an infrastructure that facilitates liquidity management.

There are also several features that could make Islamic banks less vulnerable to risk than conventional banks. For example, Islamic banks are able to pass through a negative shock on the asset side (e.g., a Musharaka loss) to the investment depositors (a Mudaraba arrangement). The risk-sharing arrangements on the deposit side provide another layer of protection to the bank, in addition to its book capital. Also, the need to provide stable and competitive return to investors, the shareholders’ responsibility for negligence or misconduct (operational risk), and the more difficult access to liquidity put pressures on Islamic banks to be more conservative (resulting in less moral hazard and risk taking). Furthermore, because investors (depositors) share in the risks (and typically do not have deposit insurance), they have more incentives to exercise tight oversight over bank management. Finally, Islamic banks have traditionally been holding a comparatively larger proportion of their assets than commercial banks in reserve accounts with central banks or in correspondent accounts. So, even if Islamic investments are more risky than conventional investments, the question from the financial stability perspective is whether or not these higher risks are compensated for by higher buffers.

Is it possible to determine whether Islamic banks are more or less stable than conventional banks? This is clearly an empirical question, the answer to which depends on the relative sizes of the effects discussed above, and it may in principle differ from country to country and even from bank to bank. The aim of the rest of this paper is to contribute to finding the empirical answer to this question.

3 Methodology and data

3.1 Measuring bank stability

Our primary dependent variable is the z-score as a measure of individual bank risk. The z-score has become a popular measure of bank soundness (see, e.g., Boyd and Runkle 1993; and Maechler et al. 2005). Its popularity stems from the fact that it is inversely related to the probability of a bank’s insolvency, i.e., the probability that the value of its assets becomes lower than the value of the debt. The z-score can be summarized as \( {\hbox{z}} \equiv \left( {k + \mu } \right)/\sigma \), where k is equity capital and reserves as percent of assets, μ is average return as percent of assets, and σ is standard deviation of return on assets as a proxy for return volatility. The z-score measures the number of standard deviations a return realization has to fall in order to deplete equity, under the assumption of normality of banks’ returns. A higher z-score corresponds to a lower upper bound of insolvency risk—a higher z-score therefore implies a lower probability of insolvency risk.Footnote 7

Why does our metric for risk apply to Islamic banks? An important feature of the z-score is that it is a fairly objective measure of soundness across different groups of financial institutions. It is an objective measure because it focuses on the risk of insolvency, i.e., on the risk that a bank (whether commercial, Islamic, or other) runs out of capital and reserves. The z-score applies equally to banks that use a high risk/high return strategy and those that use a low risk/row return strategy, provided that those strategies lead to the same risk-adjusted returns. If an institution “chooses” to have lower risk-adjusted returns, it can still have the same or higher z-score if it has a higher capitalization. In this sense, the z-score provides an objective measure of soundness.

A possible criticism of the z-score as applied to Islamic banks is that the risk-sharing arrangements provide an additional protective buffer in deposit liabilities, meaning that the book values of capital and reserves may underestimate financial strength of these banks. A large portion of Islamic banks’ financial liabilities consists of investment accounts that can be viewed as a form of equity investment (generally based on the principle of Mudarabah). Investment accounts are offered in different forms, often linked to a pre-agreed period of maturity, which may be from 1 month upwards, and the funds in the accounts can generally be withdrawn if advance notice of 1 month is given. The profits and returns are distributed between the depositors and the bank, according to a pre-determined ratio, e.g., 80% to the depositors and 20% to the bank (Iqbal and Mirakhor 1987). At the extreme, it could be argued that a bank with only restricted investment accounts would be close to a mutual fund in terms of its risk profile, with almost all risk passed to investors. Even with unrestricted investment accounts, much of the risk is in principle borne by investors.

A counterargument against this possible criticism is that even conventional banks usually have the ability to pass on risks to their customers, for example through their ability to adjust (and delay adjustments in) deposit and loan rates. Only after Islamic banks’ layers of protection have been exhausted and after the bank has started to incur losses, does a shock have an impact on capital and reserves. In other words, these additional layers of protection are ultimately reflected in the banks’ returns and capital, and thereby in their z-score. Moreover, the fact that most of the investment accounts can be withdrawn in a relatively short period of time, as well as the fact that the return distribution between the bank and the depositors/investors is pre-determined, diminishes the factual differences in risk profiles associated with the investment accounts, compared with floating-rate deposits and other conventional funding used by commercial banks. So, while the differences between Islamic and conventional banks should be born in mind, capital and reserves are still a reasonable proxy variable to assess the “bottom line” default risk.Footnote 8

As a preliminary step in the analysis, we perform basic statistical tests for the z-scores. We compare z-scores in Islamic and commercial banks. Because bank size is an important factor in some of the existing papers on bank soundness, we also subdivide banks into large and small Islamic banks and large and small commercial banks (using total assets of US$ 1 billion as the cut-off point between small and large banks), and carry out pairwise comparisons of z-scores for these various subgroups.

3.2 Regression analysis

The main part of our approach is to test, using regressions of z-scores as a function of a number of variables, whether Islamic banks are less or more stable than commercial banks. We estimate a general class of panel models of the form

where the dependent variable is the z-score z i,j,t for bank i in country j at time t; B i,j,t-1 is a vector of bank-specific variables; I j,t-1 contains time-varying industry-specific variables; Ts and T s I j,t-1 are the type of banks and the interaction between the type and some of the industry-specific variables; B i,j,t-1 T s is the interaction between bank-specific variables and the type of banks; M j,t , C j , and D t are vectors of macroeconomic variables, country and yearly dummy variables, respectively; finally, ε i,j,t is the residual.

To distinguish the impact of bank type on the z-score, we include a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the bank in question is an Islamic bank, and 0 otherwise (i.e., if it is a commercial bank). For example, if Islamic banks are relatively weaker than commercial banks, the dummy variable would have a negative sign in the regression explaining z-scores.

At the systemic (country) level, we want to examine the Islamic banks’ impact on other banks and the hypothesis that the presence of Islamic banks lowers systemic stability. For this reason, we have calculated the market share of Islamic banks by assets for each year and country and interacted it with Islamic and commercial bank dummies. For example, a negative sign for the interaction of the Islamic banks’ market share and the Islamic bank dummy would indicate that a higher share of Islamic banks reduces their soundness (reduces their z-scores).

In addition to the above key variables of interest, the regression includes a number of other control variables, both at the individual bank level and the country level.Footnote 9 To control for bank-level differences in size, asset composition, and cost efficiency, we include the bank’s asset size in U.S. dollars billion, loans over assets, and the cost-income ratio. Also, to control for differences in the structure of the bank’s income, we calculate a measure of income diversity that follows Laeven and Levine (2007).Footnote 10 This variable captures the degree to which banks diversify from traditional lending activities (those generating net interest income) to other activities. For Islamic banks, the net interest income is generally defined as the sum of the positive and negative income flows associated with the PLS arrangements (see, e.g., International Monetary Fund 2004). To further capture differences of Islamic banks in their business orientation, we interact the income diversity variable with the Islamic bank dummy. Controlling for these variables is important because there are differences in these variables between Islamic banks and the other groups.

At the country level, we include a number of variables that take on the same value for all banks in a given country. In particular, we adjust for the impact of the macroeconomic cycle by including three macroeconomic variables (GDP growth rate, inflation rate, and exchange rate depreciation). To account for cross-country variation in financial stability caused by differences in market concentration, we include the Herfindahl index, defined as the sum of squared market shares (in terms of total assets) of all banks in the country. The index can have values from 0 to 10,000 (for a system with only one bank).Footnote 11 Furthermore, to control for the possible impact of any country-specific banking crisis (e.g. Malaysia 1997), we include yearly dummy variables into the regressions without the macroeconomic control factors. This helps to pick up any potential unobserved time-varying effects of the banking crisis.

We also account for the impact of governance on stability by using the governance indicator that was compiled by Kaufmann et al. (2005). We average the 6 governance measures of voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption across the available years 2004, 2002, 2000, 1998, and 1996 into a single index per country. The governance indicator captures cross-country differences in institutional developments that might have an effect on banking risk.

All bank-specific and macroeconomic variables, the Herfindahl index, and the Islamic banks’ market share and its interaction with the Islamic and commercial bank dummies are lagged to capture the possible past effects of these variables on the banks’ individual risk. We also test for the robustness of the lagged effects by restricting the explanatory variables to contemporaneous effects.

We start the regression analysis by the pooled ordinary least squares (OLS) technique. To control for outliers, we exclude the 1st and 99th percentile of the distribution of the z-score.

To alternatively control for the outliers, we use a robust estimation technique as an important estimation method. Hamilton (2002) provides a detailed description of the technique. In a nutshell, it assigns, through an iterative process, lower weights to observations with large residuals, making the estimation less sensitive to outliers. Standard errors are calculated using the pseudovalues approach (Street et al. 1988).

To further test the sensitivity of the results with respect to the estimation method, we also estimate fixed effects and median least squares regressions. The median least squares regressor minimizes the median square of residuals rather than the average and thus reduces the effect of outliers.

We also assess the robustness of the results with respect to the selected sample. To do that, we estimate the same regressions for different bank sizes. Specifically, we estimate the regressions separately for sub-samples of large banks (those with total assets of more than US$1 billion) and small banks (all others).

3.3 Data

Our calculations are based on individual bank data drawn from the commercially available (and widely used) BankScope database. We use data on all Islamic and commercial banks in the database from 20 banking systems with a non-negligible presence of Islamic banks. Our sample covers banks in the following jurisdictions (alphabetically ordered): Bahrain, Bangladesh, Brunei, Egypt, Gambia, Indonesia, Iran, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mauritania, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, West Bank and Gaza, and Yemen. In total, we have up to 520 observations for 77 Islamic banks (and 3,248 observations for 397 commercial banks) over the period 1993 to 2004 (see Table 1 and Appendix II for additional information on sample coverage).

To capture the importance of bank size on stability in Islamic and commercial banks, we present some of the results separately for sub-samples of large banks (assets over US$ 1 billion) and small banks (all others), using the same threshold for both Islamic and commercial banks. The threshold is arbitrary, but it has been used in previous research on small banks (e.g., Mercieca et al. 2007), and, more importantly, the main results of our analysis are not sensitive with respect to moderate changes in the threshold. About 49% of the Islamic banks and about 62% of the commercial banks fall into the large bank category.

Several general issues relating to the BankScope data need to be mentioned. First, to be able to analyze Islamic banks’ impact on systemic stability, we have focused on countries where Islamic banks have a higher than negligible share of the financial system. El Qorchi (2005) notes that Islamic institutions operate in 75 countries, yet in most of those countries, Islamic banks have a very small market share. We have included all the systems where Islamic banks according to the BankScope data accounted for more than 1% of the total assets in at least 1 year in the period under observation (1993–2004). The exclusion of the Islamic banks from the other countries does not appear material, since our sample still has a good worldwide coverage of Islamic banks. This is confirmed by the fact that Islamic banks covered in our starting sample have total assets of US$253 billion as of 2004, which is in line with the estimate of “about US$250 billion” worldwide assets of Islamic banks quoted for example by El Qorchi (2005). The 19 countries in our sample include fully Islamic banking systems (Iran and Sudan), systems where Islamic banks are about the same or only slightly lower weight than commercial banks (e.g., Yemen and Saudi Arabia, with the share of Islamic banking assets in total banking assets at 42% and 40%, respectively), and systems where Islamic banks have a smaller share of the market (e.g., Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates, with the share of Islamic banking assets in total banking assets at 17% and 16%, respectively).

Second, our empirical analysis relies to a large extent on unconsolidated bank statements. Ideally, we would have opted for using only consolidated statements for all financial institutions. However, only about 1/3 of the relevant observations in BankScope are based on consolidated data; the rest are unconsolidated data. This scarcity of consolidated data limits their usefulness for econometric analysis. We therefore use consolidated data when available, but when consolidated data are not available for a bank, we use unconsolidated data instead.

Third, BankScope, while being the most comprehensive commercially available database of banking sector data, is not exhaustive. Coverage varies from country to country; for most countries in our sample, the BankScope data cover 80–90% of the banking systems in terms of total assets. Moreover, Lebanon was excluded from our analysis because of insufficient number of Islamic banking observations in BankScope, bringing the number of countries on which the aggregate results are based from 20 to 19. The coverage of our paper, while less than 100%, is still higher than that for most banking studies (and in particular studies that focus on banks with particular features, such as large banks or banks that are listed on the stock market). Even after the exclusions, total assets of the Islamic banks included in the panel are about the same as the estimated total assets of Islamic banks in the world reported in earlier literature (see above). Our sample should therefore be large enough to provide reliable inferences.Footnote 12

Fourth, we largely rely on BankScope for data quality. There are a number of important issues relating to definitions of financial indicators for Islamic banks, for example what to include in capital, or how to measure (the equivalent of) interest income. The issue of financial soundness indicators in Islamic banks is discussed in more detail for instance in International Monetary Fund (2004). For the purposes of this paper, we have largely relied on BankScope’s definitions of the key variables, even though we have done basic cross-checking and also excluded outliers, some of which may be the result of deviations from common definitions.

Fifth, some commercial banks (including several major global players) have opened dedicated Islamic windows or Islamic branches conducting business according to Islamic banking principles. However, the available financial data do not allow us to distinguish the financial performance (and importance) of these windows or branches and analyze their separate impact on financial stability. We therefore focus only on the comparison offully-fledged Islamic banks and commercial banks.

Sixth, data limitations prevent us from taking fully into account all aspects of Islamic financial contracts, for example, by controlling for type of Islamic instruments, distinguishing between PLS and other investments, distinguishing the different types of investment accounts, and return equalization funds.

In addition to the bank-by-bank data, we also use a number of macroeconomic and other system-wide indicators. Those are described in more detail in Appendix II.

4 Results

4.1 Pairwise comparisons

A preliminary look at the z-scores suggests high variability across the sample, with the z-score varying from -81 to 203,347. The high variability reflects the presence of outliers, which have a substantial impact on the reported average z-score, and this underscores the need for a robust estimation method, such as the one we use in the regression analysis (see Table 2, which presents basic summary statistics for the sample). Given the presence of a few large outliers, we show the average z-score for a sample excluding the 1st and 99th percentile from the distribution of the z-score. This choice of tails is somewhat arbitrary, but common in the literature, and it is done only to allow a meaningful discussion of the basic data. In the regression analysis, the presence of outliers is addressed in a more sophisticated fashion by the robust estimation technique.

The basic data analysis suggests that Islamic banks may be more stable than commercial banks. Islamic banks’ z-scores are on average higher than those of commercial banks (Table 2). This result seems driven by small Islamic banks that have higher z-scores than small commercial banks (indicating higher stability), while large Islamic banks have lower z-scores than large commercial banks.

A pairwise comparison of means suggests that in both cases the difference is significant at the 1% level.Footnote 13 For the whole sample, Islamic banks show slightly higher z-scores than commercial banks (significant at the 5% level).Footnote 14

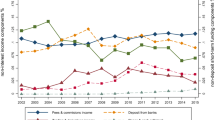

As to the other variables, Table 2 shows that large Islamic banks have on average higher loan to asset ratios than large commercial banks, reflecting the fact that Islamic banking prohibits of investment in non-lending operations such as regular bonds or T-bills in Islamic banking. The difference is insignificant for small banks as well as for all banks taken together. Large Islamic banks have higher cost-to-income ratios than large commercial banks, which is in line with at least a part of the literature on efficiency.Footnote 15 Again, there is no significant difference for small banks. There is no significant difference in terms of income diversity between Islamic banks and commercial banks Islamic banks (large or small). Finally, the Islamic banks in the sample are on average bigger than commercial banks, the difference being significant for the large sample when large Islamic banks are compared with large commercial banks.Footnote 16 Figure 1 summarizes the basic comparison of z-scores for large commercial, large Islamic, small commercial, and small Islamic banks.

To examine the robustness of these preliminary findings, we have also tried some alternatives to the standard definition of the z-score (Table 3). The underlying idea behind these alternative approaches is that the standard deviation underlying the z-score gives only a part of the information about the behavior of z-scores (see Hesse and Čihák 2007). In particular, when assessing stability, we are much more interested in the downward spikes in ROAs (and z-scores) than in the upticks. Table 3 has three columns, corresponding to three alternative variables that we have investigated. In particular:

-

We have calculated a modified z-score, defined as capitalization plus the ROA over the absolute value of the downward volatility of ROA. Results for this modified z-score are in line with the results for the “regular” z-score, namely that large Islamic banks are less stable than both small Islamic banks and large commercial banks. Small banks are about as stable as small commercial banks.

-

We have defined the downward (upward) volatility of the z-scores as the sample average of the difference between the bank-specific z-score per year and its mean of the z-score if the z-score is below (above) the bank-specific mean. Again, large Islamic banks are characterized by larger downward volatility of the z-scores, suggesting lower stability.

These robustness checks support the findings for the simple z-scores. These comparisons of z-scores are useful, but may overlook some additional factors that explain bank-to-bank variation in z-scores. We will therefore examine this issue more formally using regression analysis.Footnote 17

4.2 Regression analysis

To separate the financial stability impact of the Islamic nature of a bank from the impact of other bank-level characteristics, and from macroeconomic and other system-level impacts, we turn to regression analysis, following the methodology described in Section 3. We run several specifications. The results for the OLS estimation are shown in Table 4, while Table 5 shows results of a robust estimation technique, which assigns lower weights to observations with large residuals, thereby making the estimation less sensitive to outliers.

The regressions confirm the result from the simple comparison of z-scores that large Islamic banks tend to be less stable than large commercial banks, while small Islamic banks tend to be more stable than small commercial banks. The sign of the Islamic dummy variable is predominantly negative and significant at the 1% level in the regressions for large banks both for the OLS regression and for the robust regressions (see specifications (5) to (8) in Tables 4 and 5). Footnote 18 For small banks, the sign of the Islamic dummy is consistently positive across all regressions (see specifications (9) to (12) in Tables 4 and 5), and significant at the 5% level in all the OLS regressions and one of the robust regressions. Looking at the full sample regressions in Tables 4 and 5, the comparison of Islamic and commercial banks becomes less clear-cut, reflecting the opposite signs of differences for large and small banks.

As to the control variables, they have generally the expected signs. In particular, banks with higher loan to asset ratios tend to have lower z-scores. This slope coefficient is consistently negative with two exceptions across all specifications; it is significant in eleven of the robust estimate specifications and in four OLS specifications. Similarly, higher cost-to-income ratios have a consistently negative link to the z-scores; the sign is consistently significant except for several regressions for small banks.

Z-scores tend to increase with bank size for large banks, but decrease with size for the small banks. Greater income diversity tends to increase z-scores in large Islamic banks, suggesting that a move from lending-based operation to other sources of income might improve stability in those banks.

The governance variable tends to be positive in all regressions in which it is entered, and is strongly positive in some. This is the expected sign, suggesting that better governance is generally correlated with higher z-scores.

In the OLS model specification, a higher presence of Islamic banks in a banking system has a negative impact on z-scores in large commercial banks, but a positive impact on z-scores in commercial banks in general. The above findings become less strong in the robust estimation. Interestingly, a higher presence of Islamic banks in a banking sector tends to weaken the Islamic banks’ own z-scores.

The impact of the Herfindahl index is significantly negative. This is in line with the part of the literature on banking sector concentration and stability that finds higher concentration to be associated with lower stability (e.g., Schaeck et al. 2006). However, the result becomes less significant in the robustness regressions, so overall the effect of the Herfindahl is less clear.

In terms of the macroeconomic variables, depreciation tends to lead to significantly higher banking risk, which also makes sense since banks' balance sheet positions that are denominated in foreign currency will be eroded with a depreciating domestic currency. Real GDP growth and inflation do not appear to have significant separate effects on stability in our sample.Footnote 19

In other regressions, we also include a liquidity variable, defined as liquid assets over deposits. There is some evidence that large banks with higher liquidity buffers are more stable. Comparing large commercial and Islamic banks reveals that especially large Islamic banks with higher liquidity levels benefit. In other words, this is consistent with the story that large Islamic banks are potentially more prone to liquidity risk than large commercial banks given their very limited access to an interbanking market or hedging instruments.

In addition to testing different estimation methods, we have conducted several additional checks to test the robustness of our results. In particular, we have estimated the regressions without Iran and Sudan, two countries with fully Islamic banking systems. It had no significant impact on our main results. We have also run the same estimates using only unconsolidated or only consolidated data, and again found that the results were consistent with, but less strong than those presented in the paper. Finally, we have also tested for the robustness of the lagged effects by restricting the explanatory variables to contemporaneous effects, finding again no substantive change in the main results.Footnote 20

4.3 Conclusions and topics for further research

In this paper, we have presented the first cross-country empirical analysis of Islamic banks’ impact on financial stability. Using z-scores as a measure of stability, we find that (a) small Islamic banks tend to be financially stronger than small commercial banks; (b) large commercial banks tend to be financially stronger than large Islamic banks; and (c) small Islamic banks tend to be financially stronger than large Islamic banks.

The contrast between the high stability in small Islamic banks and the relatively low stability in large Islamic banks is particularly interesting. It suggests that Islamic banks, while relatively more stable when operating on a small scale, are less stable when operating on a large scale. Since we have adjusted for differences in variables such as bank size, the structure of the balance sheet, and system-wide variables, these effects reflect characteristics of Islamic banks. A plausible explanation for the above findings is that it is significantly more complex for Islamic banks to adjust their credit risk monitoring system as they become bigger. Given their limitations on standardization in credit risk management, monitoring the various profit-loss-arrangements becomes rapidly much more complex as the scale of the banking operation grows, resulting in problems relating to adverse selection and moral hazard becoming more prominent. Another possibility is that small banks concentrate on low-risk investments and fee income, while large banks do more PLS business.

The comparison between large and small Islamic banks is interesting in view of the analysis of data on Malaysian banks undertaken by Yudistira (2004). Yudistira finds that mergers of small Islamic banks should be encouraged from an efficiency viewpoint. Our findings suggest that to reap these efficiency benefits, appropriate attention needs to be paid also to prudential risks, which—other things being equal—tend to be greater for larger Islamic banks.

We also examine the impact of a bigger presence of Islamic banks on the soundness of other banks in a country’s financial system. We find that the impact is not significant.

The findings presented in this paper should be viewed as preliminary, given the numerous caveats relating to the cross-country data on Islamic banks. These caveats include less than complete coverage of the database, reliance (in part) on unconsolidated statements, and the fact that we have focused on fully-fledged Islamic banks and not on Islamic “windows” or Islamic branches operated by some commercial banks. Furthermore, data limitations prevented us from taking fully into account all aspects of Islamic financial contracts, for example, by distinguishing between PLS and other investments.

There is still wide scope for improvement and for further research. In particular, the coverage of our sample can be extended to a larger number of countries and banks, if some of the data gaps from BankScope could be filled using other data sources. Also, a more comprehensive data collection may help address some of the other data-related issues recognized in Section 3. Finally, further research may attempt to analyze the financial stability impacts of other forms of Islamic finance rather than the fully-fledged Islamic banks analyzed in this paper.

Notes

The term “country” as used in this paper covers also territorial entities that are not states as understood by international law and practice, but for which separate data are maintained.

Among the exceptions is the IMF (2009) which finds that Islamic banks in the Middle East were less affected in the first phase of the financial crisis in 2008 but also suffered strong profitability declines in 2009 especially in countries with high exposure to real estate and construction sectors.

For example, a recent Financial Sector Stability Assessment for Bahrain (IMF 2006) included stress tests for both commercial banks and Islamic banks.

For convenience, the term “commercial banks” is used to refer to non-Islamic banks.

It would also be possible to examine Islamic banks compared with cooperative banks, savings banks, or investment banks. However, given the dominance of commercial banks in most financial systems in the world, commercial banks are a convenient comparator. Hesse and Čihák (2007) provide an analysis of the role of cooperative, savings, and commercial banks in financial stability in a range of advanced economies and emerging markets, using a methodology similar to that applied in this paper.

For banks that are listed in liquid equity markets, a popular version of the z-score is distance to default, which uses the stock price data to estimate the volatility in the economic capital of the bank (see e.g., Danmark Nationalbank, 2004). However, given the lack of reliable market price data on Islamic banks, this paper relies on the specification of the z-score that uses accounting data.

We have discussed these arguments and counterarguments with various experts, including at the conferences and seminars mentioned in the acknowledgement. On balance, the arguments in favor of the z-score seem stronger. In addition to the arguments mentioned above, some experts noted that Islamic banks can protect investment account holders and shift risks to shareholders (so-called displaced commercial risk), and for competitive reasons, they can hold back profits in good years and pay out in bad years.

The income diversity measure is defined as \( 1 - \left| {\frac{{\left( {Net\;{\rm int} erest\;income - Other\;operating\;income} \right)}}{{Total\;operating\;income}}} \right| \) . Higher values of the variable correspond to a higher degree of diversification.

We do not have a strong prior on the impact of the Herfindahl index, because the existing literature contains two contrasting views on the relationship between concentration and stability. For example, Allen and Gale (2004) put forth arguments why more concentrated markets are likely to be more stable, while, for example, Mishkin (1999) suggests that more concentrated systems are characterized by increased risk-taking by banks.

To ensure sufficiently comprehensive coverage of Islamic banks, we have cross-checked the BankScope data on Islamic banks against the list of Islamic banks provided by the Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance at http://www.islamic-banking.com/ibanking/ifi_list.php and by IBF.net at http://islamic-finance.net/bank.html.

Also, large Islamic banks have significantly lower z-scores than small Islamic banks (at 1% level), and large commercial banks have significantly higher z-scores than small commercial banks (at 1% level).

To examine the skewness of the z-score distribution, we also calculate the median for the z-score. While there is some evidence for skewness, this is more pronounced for the Islamic banks indicating the expected heterogeneity of Islamic banks across the sample as well as the fact that commercial banks are likely to be better captured with BankScope data.

For example, Moktar et al. (2006) found that Islamic banks are less efficient than commercial banks in Malaysia, even though they also find that the gap has been declining over time.

The difference reflects the relatively higher concentration among commercial banks. There is a small number of very large commercial banks, but their impact on the (unweighted) average for all large banks is limited.

To further assess the robustness of our findings, we have also looked at other measures of financial soundness that are alternative to the z-scores. Measures such as nonperforming loans are not a viable alternative, since they focus on only one of the risks faced by banks and by themselves do not fully capture a bank’s soundness. An obvious alternative to z-scores are credit ratings by rating agencies, which also aim to be a comprehensive measure of a bank’s soundness. However, the sample of credit ratings for Islamic banks is rather small to allow for a meaningful analysis of the statistical distribution of the ratings. To perform an econometric analysis, we therefore focus on the z-scores.

As mentioned earlier, we have also estimated fixed effects and median least squares regressions. The median least squares regressor minimizes the median square of residuals rather than the average and thus reduces the effect of outliers. These regressions yielded results that were consistent with those presented here.

As an additional robustness check, we included a variable for private sector credit growth as well as an interest rate proxying for the monetary policy stance. The results did not change.

The results are available from the authors upon request. We have also tried, as an additional check, to distinguish majority government-owned and other banks, and the distinction appears to have no impact on our result. However, this last result needs to be taken with a grain of salt, given the limited availability of cross-country data on ultimate ownership of Islamic banks (BankScope distinguishes a category of government-owned banks, but it only includes commercial banks).

References

Ainley M, Mashayekhi A, Hicks R, Rahman A, Ravalia A (2007) Islamic finance in the UK: regulation and challenges. Financial Services Authority, London

Allen F, Gale D (2004) Competition and financial stability. J Money Credit Bank 36(3):453–80

Boyd JH, Runkle DE (1993) Size and performance of banking firms. J Monetary Econ 31:47–67

Choong BS, Liu M-H (2006) Islamic banking: interest-free or interest-based? Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=868567.

El-Hawary D, Grais W, Iqbal Z (2004) Regulating Islamic financial institutions: the nature of the regulated. World Bank working paper 3227. World Bank, Washington

El Qorchi M (2005) Islamic finance gears up, finance and development. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Errico L, Farrahbaksh M (1998) Islamic banking: issues in prudential regulation and supervision. IMF Working Paper 98/30. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Hamilton LC (2002) Statistics with stata. Duxbury, Belmon

Hesse H, Čihák M (2007) Cooperative banks and financial stability. IMF Working Paper No. 07/02. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Hesse H, Jobst A, Sole J (2008) Trends and challenges in Islamic finance. World Economics, forthcoming

Iqbal Z, Mirakhor A (1987) Islamic banking. International Monetary Fund occasional paper 49. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Iqbal M, Llewellyn DT (eds) (2002) Islamic banking and finance: new perspective on profit-sharing and risk. Cheltenham Edward Elgar, United Kingdom

International Monetary Fund (2006) Kingdom of Bahrain: financial system stability assessment. IMF Country Report No. 06/91 (Washington: International Monetary Fund). http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2006/cr0691.pdf.

International Monetary Fund (2009) Regional economic outlook Middle East and Central Asia. World Economic and Financial Surveys (Washington, October)

Jobst A (2007) The economics of Islamic finance and securitization. IMF Working Paper No. 07/117. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Mastruzzi M (2005) Governance matters IV: governance indicators for 1996–2004. World Bank, Washington, mimeo

Laeven L, Levine R (2007) Is there a diversification discount in financial conglomerates? J Financ Econ 85:331–367

Maechler A, Mitra S, Worrell D (2005) Exploring financial risks and vulnerabilities in new and potential EU member states. Second Annual DG ECFIN Research Conference: “Financial Stability and the Convergence Process in Europe,” October 6–7, 2005.

Mercieca S, Schaeck K, Wolfe S (2007) Small European banks: benefits from diversification? J Bank Finance 31:1975–1998

Mishkin FS (1999) Financial consolidation: dangers and opportunities. J Bank Finance 23:675–91

Moktar HS, Abdullah N, Al-Habshi SM (2006) Efficiency of Islamic banks in Malaysia: a stochastic frontier approach. J Econ Coop Among Islam Ctries 27(2):37–70

Schaeck K, Čihák M, Wolfe S (2006) Are more competitive banking systems more stable? IMF Working Paper 06/143. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Sole J (2007) Introducing Islamic banks into conventional banking systems. IMF Working Paper 07/175. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Street JO, Carroll RJ, Ruppert D (1988) A note on computing robust regression estimates via iteratively reweighted least squares. Am Stat 42:151–154

Sundararajan V, Errico L (2002) Islamic financial institutions and products in the global financial system: key issues in risk management and challenges ahead. IMF Working Paper No. 02/192. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Yudistira D (2004) Efficiency in Islamic banking: an empirical analysis of eighteen banks. Islam Econ Stud 12(1):1–19

Acknowledgement

The paper has benefited from detailed suggestions by Daniel Hardy. We also thank Patricia Brenner, Maher Hasan, Nadeem Ilahi, Andreas Jobst, Paul Mills, Abbas Mirakhor, V. Sundararajan, Ramasamy Thillainathan, and participants at the 14th World Islamic Banking Conference in Bahrain, Southwestern Finance Association Annual Conference in Houston, 2nd Emerging Markets Group Conference in London, 4th International Islamic Finance Forum in Hong Kong, seminars at the IMF, Bank Negara Malaysia, and Monash University Malaysia for helpful comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their institutions. Any remaining errors are ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix II: data issues

Appendix II: data issues

Our initial sample covered banks in the following 20 countries and jurisdictions (alphabetically ordered): Bahrain, Bangladesh, Brunei, Egypt, Gambia, Indonesia, Iran, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mauritania, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, West Bank and Gaza, and Yemen.

Our calculations are based on individual bank data drawn from the BankScope database, provided by Bureau van Dijk. We use annual data on all Islamic and commercial banks in the database from the above 20 countries. In total, we have up to 520 observations for 77 Islamic banks (and 3,248 observations for 397 comparable commercial banks) over a period of 1993 to 2004. However, BankScope does not have a sufficient number of observations for Islamic banks for Lebanon , so these countries are excluded from the regression analysis, bringing the number of countries on which the aggregate results are based from 20 to 19. Even after the exclusions, Islamic banks included in the panel have total assets of US$253 billion as of 2004, which is in line with the “about US$250 billion” estimated worldwide assets of Islamic banks (see, e.g., El Qorchi 2005).

We use consolidated data when available, but when consolidated data are not available for a bank, we use unconsolidated data instead.

To classify whether a bank is commercial or Islamic, we have used the BankScope classification as a starting point. BankScope defines as Islamic banks that are members of the “International Association of Islamic Banks” plus 20 non-member banks that are considered to be “Islamic” by FitchRatings. However, we have found that in several cases, BankScope misclassifies Islamic banks as commercial, and vice versa. Therefore, we have cross-checked the BankScope classification with the information available from the FSAP exercises in the relevant countries, the information available on the respective banks’ websites, and the list of Islamic banks provided by the Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance at http://www.islamic-banking.com/ibanking/ifi_list.php and by IBF.net at http://islamic-finance.net/bank.html.

In all calculations, large banks are defined as those with total assets of more thanUS$1 billion. All other banks are classified as small banks.

The table on the following two pages describes the individual variables used in the paper and their sources.

Variable | Description | Source |

Z-score | Defined as \( {\hbox{z}} \equiv \left( {k + \mu } \right)/\sigma \), where k is equity capital as percent of assets, μ is average return as percent of assets, and σ is standard deviation of return on assets as a proxy for return volatility. Measures the number of standard deviations a return realization has to fall in order to deplete equity, under the assumption of normality of banks’ returns. | Authors’ calculations based on BankScope data. |

Assets_bln | Total assets of a bank (In U.S. dollars billion). | BankScope. |

Loans_assets | Ratio of loans to assets (percent). | BankScope. |

Cost_income | Ratio of cost to income (percent). | BankScope. |

Income diversity | \( 1 - \left| {\frac{{\left( {Net\;{\rm int} erest\;income - Other\;operating\;income} \right)}}{{Total\;operating\;income}}} \right| \) | Authors’ calculations based on Laeven and Levine (2007) and BankScope. |

Income diversity* Islamic bank dummy | Interaction of income diversity and Islamic bank dummy. | Authors’ calculations based on BankScope. |

Herfindahl index | Sum of squared market shares of banks in the system. | Authors’ calculations based on BankScope. |

GDP growth | Growth rate of nominal GDP, adjusted for inflation (in local currency). | IMF (International Financial Statistics). |

Inflation | Year-on-year change of the CPI index (percent). | IMF (International Financial Statistics). |

Exch. rate depreciation | Year-on-year change in the nominal exchange rate, local currency per U.S. dollars (percent). | IMF (International Financial Statistics). |

Islamic bank dummy | Equals 1 for Islamic banks; 0 otherwise. | Authors’ calculations based on BankScope. |

Share of Islamic banks | Market share of Islamic banks in a country per year. | Authors’ calculations based on BankScope. |

Share of Islamic banks * Islamic bank dummy | Interaction of share of Islamic banks and the Islamic bank dummy. | Authors’ calculations based on BankScope. |

Share of Islamic Banks * commercial bank dummy | Interaction of share of Islamic banks and the commercial bank dummy. | Authors’ calculations based on BankScope. |

Governance | Average of the six governance measures- voice & accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law and control of corruption- across the available years 2004, 2002, 2000, 1998 and 1996 into one single index per country. | Authors’ calculations based on Kaufmann et al. (2005). |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Čihák, M., Hesse, H. Islamic Banks and Financial Stability: An Empirical Analysis. J Financ Serv Res 38, 95–113 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-010-0089-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-010-0089-0