Abstract

This study compares internal and external sources of capital in the insurance industry by analyzing reinsurance activity between affiliated and unaffiliated insurers. Tests are performed using data from a large sample of property-liability insurers that are affiliated with at least one other property-liability insurer. Results indicate that while demands for internal and external reinsurance have some factors in common, there are cost-based differences in internal and external capital, as well as structural differences in the use of internal and external reinsurance. Results are consistent with previous theories related to internal versus external capital markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Reinsurance is a critically important part of the insurance industry. In 1999, insurers paid $233 billion in reinsurance premiums. Many reinsurance transactions take place between insurers and unaffiliated reinsurers, but the bulk of reinsurance transactions actually occur between affiliated insurers. Insurance firms are often affiliated as members of an insurance group. In 1999, 1928 out of 2707 US property casualty insurance companies were affiliated with insurance groups. These 1,928 group members accounted for 96% of industry direct written premium in that year. Reinsurance activity within insurance groups is a common practice. In 1999, $181 billion were ceded within property casualty insurance groups as reinsurance premiums. Roughly 80% of reinsurance activity (by premium volume) occurs within groups rather than between insurers and unaffiliated external reinsurers. The use of reinsurance contracts among affiliated insurers may represent an extremely active internal capital market.

Mayers and Smith (1982, 1990) propose hypotheses about the demand for insurance and subsequently test these hypotheses using data from the insurance industry. They contend the purchase of reinsurance by an insurance company is comparable to the purchase of insurance by firms in other industries. They hypothesize that demand for reinsurance may be a function of the structure of the tax code, expected costs of financial distress, the insurer’s ownership structure, investment incentives, information asymmetry, and comparative advantages in real service production, among other factors. In their study, internal and external reinsurance are not separated due to data limitations.Footnote 1 As will be discussed in the next section, it is not clear that all of the hypotheses of Mayers and Smith (1982, 1990) regarding the demand for reinsurance would apply equally to intra-group reinsurance as to reinsurance with unaffiliated reinsurers. Garven and Lamm-Tennant (2003) examine the demand for reinsurance from a capital-structure perspective, but only include unaffiliated insurers in their sample, which represent only a small segment of the industry. Jean-Baptiste and Santomero (2000) examine the effect of asymmetric information on the trading of underwriting risk between insurers and reinsurers, concluding that such information asymmetry affects both the cost of reinsurance and the amount of reinsurance purchased. Their analysis does not consider the reduced level of information asymmetry involved when the insurer and reinsurer are part of the same affiliated group, and how that might influence the amount of reinsurance transacted.

Purchasing reinsurance is essentially a capital structure decision, with equity capital and reinsurance acting as substitutes (Berger et al. 1992; Garven and Lamm-Tennant 2003). Extensive work in the corporate finance literature seeks to explain how corporations choose their capital structure. Many studies focus on capital sources that are external to the firm such as debt and equity. Some focus on the single firm’s preferences among various sources of capital used to fund projects (Myers 1984; Myers and Majluf 1984; Greenwald et al. 1984). Fazzari et al. (1988) show that information asymmetries between recipients and providers of capital increase the cost of external capital relative to the cost of internal capital. As mentioned above, Jean-Baptiste and Santomero (2000) argue that information asymmetry increases the cost of reinsurance. In contrast to studies focusing on external capital, another line of research investigates internal capital markets in which a corporate headquarters allocates capital among members of a conglomerate. Several studies present hypotheses of costs and benefits of internal capital markets. Alchian (1969), Williamson (1975), and Gertner et al. (1994) progress to a theory where consequences of internal and external capital markets differ by relative effects of asymmetric information and agency problems. Specifically relevant to the current study, they show that internal capital markets should be associated with decreased information asymmetries compared to capital acquisition from external sources.

This study examines separately demand for internal and external reinsurance, using both traditional reinsurance demand theory and internal capital markets theory to develop hypotheses. The paper makes a number of contributions. First, it will serve as a test of whether the results of previous literature, which treated internal and external reinsurance the same or looked only at single unaffiliated insurers, are supported when the data are refined so that internal and external reinsurance are disaggregated. Second, this paper will examine whether the factors that influence internal reinsurance purchases differ from those factors that influence external reinsurance purchases. In so doing, the paper will shed light on the dynamics of internal versus external capital markets, an issue that is only beginning to be explored in the insurance industry.

This research is of potential interest to parties both inside and outside of the insurance industry. The importance of reinsurance in the industry is without question. However, despite the fact that the majority of reinsurance transactions occur between group members rather than with external reinsurers, previous research has not explored the topic of intra-group reinsurance. More broadly, analyzing internal reinsurance along with external reinsurance provides a unique opportunity to explore issues related to the general finance topic of internal capital markets.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 1 provides a very basic framework for looking at the reinsurance purchase decision, drawing from the insights of Jean-Baptiste and Santomero (2000). Section 2 describes the empirical approach used, develops hypotheses related to demand for internal and external reinsurance, and describes the variables used in the empirical analysis. Section 3 describes the data and presents the empirical results. Section 4 concludes.

The Reinsurance Purchase Decision

The purchase of reinsurance can yield a number of benefits. It can reduce expected taxes, reduce expected costs of bankruptcy, and allow access to real services of the reinsurer where the reinsurer has a comparative advantage over the ceding insurer in the provision of these services (Mayers and Smith 1982, 1990; Berger et al. 1992; Garven and Lamm-Tennant 2003). Obviously, the purchase of reinsurance also involves costs for the ceding insurer. In the model of Jean-Baptiste and Santomero (2000), the premium for reinsurance reflects both the true riskiness of the primary insurer’s policies that are being reinsured, as well as the noisiness of the reinsurer’s signal regarding the true quality of the reinsured business. This noisiness arises as a result of asymmetric information between the insurer and the reinsurer. The insurer has more information than the reinsurer regarding the risk being transferred, as well as more control over the ultimate outcome of the risk (through claims settlement processes). Jean-Baptiste and Santomero (2000) demonstrate that this asymmetric information leads to higher reinsurance premiums, lower expected profit by the ceding insurer, and a lower quantity of reinsurance being purchased compared to the first-best outcome.

The Jean-Baptiste and Santomero (2000) analysis implicitly assumes that reinsurance transactions occur between entities with no affiliation to each other aside from the reinsurance arrangement itself. As stated earlier, however, the majority of reinsurance premiums involve transactions between insurers that are affiliated as part of the same insurer group. Assuming the individual companies within an insurer group are being managed to maximize the value of the group as a whole, reinsurance transactions among group members should involve dramatically lower asymmetric information costs compared to transactions between an insurer and an unaffiliated reinsurer. Without the noise created by asymmetric information, internal reinsurance (i.e., reinsurance between affiliates of the same group) should be cheaper than external reinsurance.

While internal reinsurance may have a lower cost than external reinsurance due to reduced asymmetric information, internal and external reinsurance may have different levels of benefit as well. For example, a key benefit to external reinsurance, as mentioned earlier, is the ability to access certain expertise in real services possessed by the reinsurer. Within a group being managed to maximize the group’s overall value, such expertise (to the extent it exists within the group) would be shared among members without the need for reinsurance deals. Alternatively, the required expertise may simply not exist within the group, making external reinsurance the only option for accessing the expertise. As another example, if an insurer’s motivation for reinsurance is to reduce the probability of bankruptcy, but the rest of the insurer group has no better capacity for holding the risk than the insurer that currently holds the risk, there may be no benefit (to the group) of reinsuring within the group. In such a case, external reinsurance would be the more beneficial option. The key point is simply that both the cost and benefit of any particular reinsurance transaction may differ between internal and external reinsurance. Thus, there may be some cases where internal reinsurance dominates external reinsurance, and other cases where external reinsurance dominates internal reinsurance. Within a particular insurer with multiple lines of business and multiple motivations for purchasing reinsurance, it may well be optimal to simultaneously purchase some internal reinsurance and some external reinsurance.

With this general framework in mind, the next section describes specific hypotheses related to quantities of internal and external reinsurance purchased by insurers, as well as the variables to be used in the empirical analysis to test the hypotheses. While for expositional convenience and comparability to previous studies the hypotheses generally are worded to focus on the demand for reinsurance, note that the analysis implicitly considers supply factors as well, because it is assumed that the decision to purchase reinsurance is based on the equilibrium price available to the insurer, which will depend on things such as the level of information asymmetry between the parties. In addition, the empirical model includes variables to control for the capacity constraints that may apply to reinsurance transactions.

Empirical Models and Development of Hypotheses

Empirical Approach

To analyze internal and external reinsurance decisions, the empirical approach will be to estimate the following two equations using robust least squares regression.

Internal Reinsurance it and External Reinsurance it represent observations of the two dependent variables for insurer i in year t. X it is a vector of independent variables expected to affect reinsurance activity; α and ϕ are constant intercept coefficients; and ɛ it and λ it are random error terms. Both models control for year fixed effects and standard errors are robust to clustering within affiliates of a given group.Footnote 2

Hypotheses Development and Description of Variables

In this section, both the dependent and independent variables used in the empirical analysis are described, along with the hypotheses associated with each independent variable. Table 1 contains a summary of the definitions of all of the variables.

Reinsurance Activity

The measures of both external and internal reinsurance are similar to the measure used by Mayers and Smith (1990) and Garven and Lamm-Tennant (2003). The dependent variables are designed to capture the ratio of reinsurance premium ceded to total premium written. In the current study, measures of external and internal reinsurance are modified to net out the distorting effects of inter-company pooling.Footnote 3 Affiliated insurers often participate in inter-company pooling arrangements. All premiums for insurance included in the arrangement are ceded to the lead insurer of the group. The lead insurer then retrocedes some portion of the collective risk back to each participating insurer based on financial capacity. Consider a simple example of two insurers (A and B) involved in a pooling arrangement. Each insurer writes $100 in direct premium. Insurer B cedes 100% of this premium to Insurer A. Insurer A retrocedes $50 premium back to Insurer B. The net effect is that Insurer B writes $100 and cedes $50, while Insurer A writes $150 and cedes none. However, without modification the measure used for internal reinsurance would show that Insurer A wrote $200 and ceded $50, while Insurer B wrote $150 and ceded $100, obviously distorting the substance of the transactions. To correct for this bias, only the net effect of pooling arrangements is included in the numerator of the internal reinsurance measure and the denominators of both the external and internal reinsurance measures. Thus, the measure of internal reinsurance would be equal to zero for Insurer A and 0.5 for Insurer B. The independent variables used in the study, and their associated hypotheses, are explained below.

Taxes

Provisions in the United States Tax Code may play a role in an insurer’s decision to purchase reinsurance. Insurance firms are likely to be on the convex portion of the tax schedule.Footnote 4 Mayers and Smith (1982, 1990) point out that the purchase of reinsurance can lower the volatility of an insurer’s pretax earnings thereby decreasing its expected tax liability. Garven and Louberge (1996) develop a model that implies insurers use reinsurance to achieve the optimal allocation of tax shield benefits. To empirically test the tax motivation for purchasing reinsurance, Garven and Lamm-Tennant (2003) offer the following testable hypothesis: “Other things equal, the demand for reinsurance will be greater for firms that concentrate their investments in tax favored assets.” Insurers may deduct incurred losses from pre-tax income. Large unexpected losses may more than offset an insurer’s earned premium income. In this case the insurer would not be able to fully recognize the tax shield provided by the tax-favored asset. Because after-tax certainty-equivalent returns must be equal across all securities, the chance of not being able to recognize the tax shield reduces the value of tax-favored securities. The purchase of reinsurance reduces the probability of experiencing a large unexpected loss. Contrary to expectations, Garven and Lamm-Tennant (2003) do not find evidence to support the hypothesis that investment in tax favored assets increases demand for external reinsurance.

The Garven and Lamm-Tennant tax hypothesis is now expanded as follows: if internal reinsurance costs less than external reinsurance, this difference may be great enough to make the cost of internal reinsurance less than the expected cost of not realizing the tax shield on these investments even if the cost of external reinsurance is greater than the expected tax savings. This result would support Mayers and Smith’s more general hypothesis that provisions in the tax code affect insurers’ demand for reinsurance, even if the impact is only large enough to affect internal reinsurance purchases. Furthermore, it would be consistent with Jean-Baptiste and Santomero’s (2000) prediction that information asymmetry increases the cost of reinsurance, and that information and agency problems increase the cost of external capital relative to internal capital (Myers and Majluf 1984; Fazzari et al. 1988).

The ratio of tax-exempt investment income to total investment income (Tax-Exempt Investment Income) is estimated as follows. Tax-exempt investment income equals bond interest exempt from federal taxes plus 70% of dividends on common and preferred stock. This calculation is similar to that used by D’Arcy and Garven (1990) and Garven and Lamm-Tennant (2003), but it is adjusted to reflect changes in the tax code since 1987. The 70% multiplier for dividends is a conservative estimate because, according to IRS form 1120pc, property-casualty insurers may deduct 80% of dividend income received from a company of which it owns at least 20%. The 70% figure is chosen because the data provides limited information about insurers’ ownership share of non-insurance firms, and the lower percentage biases against the hypothesized result. This method also partially mitigates the unobservable cost of the Alternative Minimum Tax. Similar results were calculated by assuming dividends from affiliates were in the 20% ownership classification.

State premium taxes and regulatory costs could also affect internal reinsurance behavior. Petroni and Shackelford (1995) show that insurers create subsidiaries to minimize tax and regulatory costs when entering new state markets. At the group level, the insurers may be financially strong and well diversified, but because they split into multiple companies they have to redistribute capital and exposures among group members. Thus, some internal reinsurance is likely the result of creating subsidiaries for tax and regulatory reasons. This motivation for creating subsidiaries does not lead to bias in testing our hypotheses, but it may add noise to the analysis.

Information Asymmetry

Information asymmetry between recipients and providers of capital will increase the cost of capital in the presence of incentive conflicts between the two parties.Footnote 5 Such asymmetric information is likely to increase transaction costs involved in correctly assessing the recipient’s characteristics. One way to mitigate this agency cost is to remove the incentive conflict by combining the two parties, as is the case with internal capital markets. To the extent that affiliation reduces information and agency costs, these factors are already incorporated in the model by separating the dependent variables. Two variables are added to the regression models to explicitly capture the effects of information asymmetry. The first information proxy is Age, equal to the natural logarithm of the firm’s age in years. Jean-Baptiste and Santomero (2000) show that insurers assimilate information about each other over time; therefore, all else equal, older firms should face smaller information costs. The second information proxy only appears in the external equation, since it should have no direct impact on internal reinsurance. It is a dummy variable, Publicly Traded, equal to one if the insurer is publicly traded, or belongs to a group or holding company that is publicly traded. Information asymmetry between insurers and external parties should be lower for publicly traded firms due to disclosure requirements and the efforts of analysts who follow these firms (Pottier and Sommer 1999). While each firm does not have its own ticker symbol, it should be examined by analysts in the process of assessing the publicly traded entity. The decrease in information costs yields a prediction of a positive relation between Publicly Traded and External Reinsurance. It is important to note, however, that although Publicly Traded is used here to proxy for improved information, Mayers and Smith (1982, 1990) hypothesize that owners of widely held firms are less averse to nonsystematic risk because they can hold diversified portfolios. Publicly traded firms are likely to be widely held. This argument implies a negative relation between Publicly Traded and External Reinsurance. Thus, the difference in reinsurance activity between publicly traded firms and other insurers is left as an empirical question.

Relative Size within Group

The size of member companies is not consistent within groups. While the absolute size of a company, as will be discussed, may affect its demand for reinsurance, the size of the company relative to the rest of its group may affect the supply of internal and external reinsurance available to the company. In the case of internal reinsurance, supply may be dictated by capacity. If the company is large relative to the rest of its group, its affiliates may not be able to reinsure a large percentage of the company’s direct written premiums. However, relatively large firms may face less external capital market friction than smaller firms when contracting for external reinsurance. This suggests group value could be maximized by having the largest insurers in a group access external capital markets (cede external reinsurance) on behalf of other affiliates, and then distribute this capital by assuming reinsurance internally. Size differences within groups are controlled for in the regression models with the ratio of the company’s total assets to the total assets of the group (Company-to-Group Size Ratio).

Number of Affiliates

In the sample used for this study, the number of affiliated property-liability insurers in a given group ranges from two to 47. The number of affiliates may affect the amount of internal reinsurance ceded by a company in two ways. First, if each affiliate specializes in a different type or types of insurance (based on line of business, geographic location, or commission schedule) then the companies might reinsure internally to spread the risks evenly across the group based on financial capacity. Second, using the same internal capacity rationale as the Company-to-Group Size Ratio variable, it may be the case that an insurer with more affiliates faces a greater supply of internal reinsurance. For these two reasons, insurers with a greater number of affiliates are expected to cede more internal reinsurance and less external reinsurance. The variable used to control for these effects (Number of Affiliates) is the natural logarithm of the number of affiliates in the insurer’s group.

Catastrophe Exposure

Prior studies hypothesize exposure to catastrophic loss increases demand for external reinsurance via increased capitalization requirements (Mayers and Smith 1982, 1990; Garven and Lamm-Tennant 2003). However, affiliated insurers with catastrophe exposure have an incentive to cede less reinsurance to group members. One reason to create a subsidiary is to compartmentalize catastrophic losses so they do not affect other group members. For example, several large insurance groups with homeowners exposure in Florida write this coverage via a subsidiary (e.g. Allstate Floridian Insurance Company and State Farm Florida Insurance Company). The group then holds a put option on homeowners losses in Florida with strike price equal to the value of the subsidiary’s assets. It is important to note that the possibility of insureds piercing the corporate veil, and the decrease in value of the insurer’s intangible assets reduce the benefit to the group of exercising the put option. Even if the group does not intend to exercise the put option, they can benefit from writing catastrophic lines of insurance via a subsidiary to insulate the rest of the group from negative changes in financial strength ratings. Indeed, State Farm Florida Insurance Company currently carries a lower A.M. Best rating (A-u) than most other members of the State Farm Insurance Group (A++). Therefore, if insurer groups use this strategy to compartmentalize catastrophe exposure, there should be a negative relation between catastrophe exposure and internal reinsurance, and a positive relation between catastrophe exposure and external reinsurance.

A.M. Best, arguably the most important financial strength rating agency for insurance companies, considers reinsurance a form of explicit support among affiliates (see A.M. Best 2005). In the absence of such an indicator of support, an affiliate’s financial strength rating will not be improved by the financial strength of the group or holding company to which it belongs. This suggests that residual uncertainty exists regarding consumers’ ability to pierce the corporate veil.

The model includes three variables measuring exposure to catastrophic losses at the firm level. The first is Catastrophe Exposure, the ratio of property insurance premium written in eastern coastal states and earthquake premium in California to total premium written (Gron 1999). A positive relation should exist between Catastrophe Exposure and External Reinsurance and a negative relation between Catastrophe Exposure and Internal Reinsurance. The next two variables measure concentration of premium by geographic area and line of business. Geographic Concentration is a herfindahl index of premium written by state and Line of Business Concentration is a herfindahl index of premium written by line of business.

All else equal, insurers that concentrate premiums in fewer areas or lines of business are expected to have more exposure to catastrophic loss; however, as described below, there are two other potential effects of concentration that cannot be adequately measured. First, insurers that concentrate exposures in fewer lines of business or fewer geographic areas may choose less risky lines of business, or select less risky insureds within each line or area. Available data do not provide information for within-line or -area heterogeneity. Second, Mayers and Smith (1990) offer that insurers’ demand for real services may depend on concentration of premiums in geographic areas or lines of business creating the opposite relation between concentration and demand for reinsurance. These hypotheses are described in the following paragraph. For these reasons, the effects of concentration on demand for reinsurance must be determined empirically.

Real Service Efficiencies

Mayers and Smith (1990) offer comparative advantages in real service production as a factor influencing the demand for reinsurance. They measure the benefit of real services inversely by the geographic concentration and line of business concentration of risks insured. If risks covered by an insurer are spread across regions and lines of business they may benefit more than other insurers from a reinsurer’s expertise or infrastructure in a given area or line. If a reinsurer has valuable expertise in real services such as claims handling or insurance pricing, an insurer may choose to enter into a reinsurance contract to gain access to those services (Webb et al. 2002). Therefore, the real services hypothesis predicts a negative relation between the two measures of concentration and demand for reinsurance. This argument applies to external reinsurance, but not to internal reinsurance. If sharing these services can add value to the group, these services should be shared among members of the group without need for a reinsurance contract. It is also important to note, as stated in the previous paragraph, that insurers with concentrated exposures may choose insureds with less catastrophic exposure, leading to the same negative relation between concentration and demand for reinsurance.

Expected Cost of Bankruptcy

If the loading costs in a reinsurance agreement are less than the subsequent reduction in expected bankruptcy costs, an insurer can increase its value by shifting risk to a reinsurer to decrease its probability of insolvency. Warner (1977) provides evidence that bankruptcy costs are less than proportional to firm size. Mayers and Smith (1990) and Garven and Lamm-Tennant (2003) find evidence of an inverse relationship between firm size and the demand for external reinsurance, consistent with the bankruptcy cost hypothesis. The same result would be expected here. The variable Company Size is equal to the natural logarithm of total admitted assets.

Investment Incentives

Myers (1977) shows that some firms may have incentives to forego valuable investment opportunities. In some circumstances, with risky debt in the capital structure, taking a positive net present value (NPV) project makes stockholders worse off because the benefits accrue to the bondholders. Bondholders anticipate the owner’s incentive and factor this into the rate of return they demand for debt. Both parties can be made better off if the owner can bond itself against such activity. Mayers and Smith (1987) show that the purchase of insurance can control this underinvestment problem by softening the impact of large unexpected losses.

Policyholders have a claim to the insurance company’s assets similar to debtholders in other firms. Large unexpected losses may cause equity-holders of an insurance company to reject a positive NPV project because the benefits would accrue primarily to the policyholders. By purchasing reinsurance an insurer can transfer the risk of large unexpected losses, reducing the expected cost of foregoing valuable projects. In an insurance company with higher leverage, policyholders have a proportionally greater claim to the company’s assets. This increases the probability of foregoing valuable projects because returns will primarily benefit policyholders rather than owners. Thus, insurers with higher leverage are expected to demand more reinsurance because of investment incentives. Insurer financial leverage (Leverage) is measured as the ratio of total liabilities to total assets, gross of reinsurance transactions.

Default Risk

The quality of insurance products is a negative function of the insurer’s default risk. Sommer (1996) finds evidence that policyholders will pay higher premiums to be insured by less risky insurers. This provides an additional incentive for insurers to reduce default risk by purchasing reinsurance. Mayers and Smith (1990) use A.M. Best insurer ratings as a proxy for default risk. However, because A.M. Best considers reinsurance in their financial strength rating, and thus the rating already reflects reinsurance transactions, alternative measures of default risk are used in the current study. All else equal, insurers with more assets and less financial leverage are less likely to become insolvent. Sommer (1996) finds evidence that consumers pay higher prices to be insured by companies with more total assets and less financial leverage. Cummins et al. (1995) find that smaller insurers are more likely to become insolvent. BarNiv and Hershbarger (1990) and Carson and Hoyt (1995) find that insurers with higher financial leverage have greater risk of insolvency. Size and Leverage are used as measures of default risk prior to reinsurance transactions. The above arguments imply a positive relation between an insurer’s default risk and demand for reinsurance.Footnote 6 Recall that Leverage is also discussed above regarding investment incentives. Both the default risk hypothesis and the investment incentives hypothesis lead to the same expected positive relation with reinsurance ceded.

Organizational Form

Mayers and Smith (1990) find organizational form is an important factor in the demand for reinsurance. The sample used in the current study includes insurers organized as mutual firms and stock firms. For both stock and mutual firms, policyholders are equivalent to bondholders in other firms. However, the organizational forms differ in terms of ownership rights. The owners of a mutual company are its policyholders, whereas equity holders retain the residual rights to a stock company. Organizational form may impact internal and external reinsurance decisions along a variety of dimensions. First, agency problems between policyholders and equity holders are inherently mitigated in a mutual insurer because the policyholders and the equity holders of the company are one and the same. Eliminating the incentive conflict between policyholders and equity holders may result in mutual insurers taking less risk (Lamm-Tennant and Starks 1993). Also, because of the relative lack of external monitoring of mutual firms, mutuals could face greater information costs when accessing external reinsurance. If this information deficit increases the cost of external reinsurance, mutual insurers should prefer internal reinsurance to external reinsurance. Additionally, because mutual insurers have only limited access to other sources of capital, they may rely more heavily on reinsurance. Mutual, a dummy variable equal to one if the insurer is organized as a mutual company is included to control for organizational form. For the reasons described above, there should be a positive relation between Mutual and demand for internal reinsurance. However, the relation between Mutual and external reinsurance is indeterminate, with information cost factors implying a negative relation and capital constraints implying a positive relation.

Lines of Business

Some lines of insurance present significantly different risks based on expected size, timing, and volatility of cash flows. It follows that these differences among lines would affect an insurer’s demand for reinsurance. Mayers and Smith (1990) note significant improvement in their model’s explanatory power when they control for the insurer’s business mix. Similar to Mayers and Smith (1990) the percentage of direct premiums written in each line for each insurer is added to the regression model to control for business mix.Footnote 7 Mayers and Smith (1990) comment that one limitation of their data is that direct premiums written by line of business do not account for within-line policy heterogeneity. For example, NAIC data does not differentiate among homeowners policies, even though the risk insured by a homeowners policy (from wind and hail) in Florida is significantly greater than a policy insuring an identical home in Minnesota. These differences are partially accounted for by adding the proxy for catastrophe exposure discussed earlier.?>

Data and Empirical Results

Description of Sample and Summary Statistics

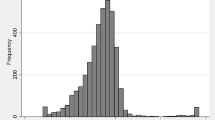

Table 2 displays descriptive statistics for the sample used in the empirical analysis. Company level data for insurers for data years 1996 through 1999 are from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC). A total of 8,878 observations of active stock or mutual insurance companies were reported to the NAIC during the 4-year sample period. Of these, 6,223 were affiliated with at least one other property-liability insurer. The appropriate sample for this study includes active insurers that write direct business and then have the opportunity to cede some portion of direct premiums to other insurers in their group, in addition to the opportunity to cede to external reinsurers. Insurers that reported non-positive numbers for direct written premiums or total assets are excluded. Another step in the sample selection process was to exclude insurers reporting extraordinary or incomplete figures for the dependent variables. Some insurers report a value greater than one for one of the dependent variables, indicating premiums ceded were greater than the sum of premiums written and assumed. Mayers and Smith (1990) attribute this phenomenon to an insurer’s decision to exit from a line of business, or a geographic region, because it has stopped issuing new policies, but reinsures policies still in force. These observations are excluded because they represent extraordinary operating characteristics. Firms for which external reinsurance premiums account for more than 75% of total written premiums are also excluded, since our focus is in primary insurers rather than reinsurers.Footnote 8 The final sample includes 4,495 affiliated insurer observations. These insurers wrote 82% of the industry’s total premium and 87% of premium written by affiliated insurers during the sample period.

Table 3 displays a summary of the reinsurance activity in the sample. The occurrence of reinsurance transactions among insurers is quite common. Sixty-six percent of the observations in the sample cede some reinsurance to affiliates, and 76% cede reinsurance outside of their groups. Only 6% of the observations do not cede any reinsurance. Some insurers cede reinsurance only to their affiliates, while others cede premiums only to insurers outside of their groups. Forty-eight percent of observations in the sample cede reinsurance both internally and externally. It is also common for insurers to assume reinsurance from both their affiliates and other insurers.

Empirical Results

Results for the regression equations appear in Table 4. The tax variable yields results of primary interest. The coefficient estimate for the percentage of an insurer’s assets invested in tax-favored securities is not statistically significant in the external reinsurance equation, consistent with the findings of Garven and Lamm-Tennant (2003), despite the hypothesis of a positive relation. However, in the equation for internal reinsurance the coefficient estimate for the tax variable is significant and positive. Thus, it appears that taxes provide a sufficient motive to purchase internal reinsurance, but are insufficient to motivate external reinsurance. These results are consistent with internal reinsurance costing less than external reinsurance due to reduced information asymmetry. The cost of internal reinsurance may be less than the expected cost of not realizing the tax shield on tax-favored securities; however, information and agency problems may raise the cost of external reinsurance above the expected cost of not realizing tax shields.

The coefficient on the variable measuring the age of the insurer is positive but insignificant in both equations. The age variable was included as a proxy for information asymmetry between insurers and reinsurers, since older insurers would have established track records with reinsurers that might lower such asymmetry. However, our findings do not support this hypothesis.

The number of affiliates is positively related to internal reinsurance and negatively related to external reinsurance, consistent with the idea that an insurer that has few affiliates has only limited opportunities to cede reinsurance internally. Similarly, the coefficient estimate for the company-to-group size ratio is negative in the internal reinsurance equation and positive in the external reinsurance equation. This is consistent with capacity constraints for internal reinsurance. It also suggests that larger insurers access external capital markets on behalf of the rest of the group.

Consistent with expectations, the coefficient estimate for Catastrophe Exposure is significant and positive in the external reinsurance equation. It is not significantly different from zero in the internal reinsurance equation. This evidence is consistent with internal and external reinsurance serving different purposes. Specifically, external reinsurance appears to be an appropriate tool for shifting catastrophic risk outside of a group; however, insurers may prefer to compartmentalize risk of catastrophic losses, such as hurricane damage, within one subsidiary, insulating the rest of the group from adverse loss experience.

The other two variables that could measure underwriting exposure, Geographic Concentration and Line of Business Concentration, display negative relations with internal reinsurance, but the coefficient estimates in the external reinsurance equation are not statistically different from zero. Firms with concentrated exposure cede less reinsurance internally than those with more diverse portfolios of risks. Because internal and external reinsurance are separated in this analysis, the results are interpreted differently from similar results in the extant literature. Mayers and Smith (1990) conclude that the negative relation between concentration and reinsurance ceded is consistent with the real services benefit of reinsurance empirically dominating its risk reducing effect. The authors also offer as an alternative explanation that insurers with more concentrated exposures may systematically insure less-risky applicants within each line of insurance. The negative coefficient estimates for both of the two concentration variables in the internal reinsurance equation favor the latter interpretation. Because insurers belonging to the same group or holding company have incentives to share expertise or other real services without the need for a reinsurance contract, it is unlikely that the results for internal reinsurance are driven by the real services hypothesis. Thus, these results suggest that concentrated insurers systematically choose liabilities that are ultimately less risky.

As anticipated, the coefficient estimate for Size is significant and negative in both equations, demonstrating that larger firms cede less reinsurance, both internally and externally. These results are consistent with the bankruptcy cost hypothesis, and support the findings of previous studies. Also consistent with the bankruptcy cost hypothesis, as well as the investment incentives hypothesis, the coefficient estimate for Leverage is significant and positive in both equations. Results for both Size and Leverage are also consistent with the hypothesis that insurers with greater default risk will cede more reinsurance. These results are consistent for both internal and external reinsurance, thus providing no evidence that consumers see internal reinsurance as irrelevant due to the possibility of corporate veil-piercing.

The coefficient estimate for Mutual is significant and positive in the internal reinsurance equation, as was anticipated. Mutual is not statistically significant in the external reinsurance equation. Thus, mutual insurers appear to cede more internal reinsurance than do stock insurers, but the same is not true for external reinsurance. Recall that the expected relation between mutual and external reinsurance was indeterminate, since risk aversion and capital constraints would imply a greater general demand for reinsurance, but increased information asymmetry implies a greater cost for external reinsurance. These competing factors may be offsetting each other, yielding the insignificant results for Mutual in the external equation.

Conclusions

The empirical results of this article provide evidence that internal and external reinsurance are not perfect substitutes for affiliated insurance companies. Some of the results also apply to the more general hypothesis that internal and external sources of capital differ in cost. It appears that there are both structural and cost differences between internal and external reinsurance. The results also reaffirm and clarify some findings of previous studies of the demand for external reinsurance.

The amounts of both internal and external reinsurance ceded are affected by expected costs of bankruptcy and investment incentives. Smaller insurers face greater expected costs of bankruptcy as a proportion of assets, and they are more likely to become insolvent. All else equal, highly levered insurers are also more likely to default, and they are more susceptible to the underinvestment problem. Consistent with these hypotheses, results indicate that insurers with more assets cede less reinsurance, and insurers with higher financial leverage cede more reinsurance.

Evidence suggests structural differences in the use of internal and external reinsurance. Insurers appear to cede reinsurance externally to mitigate risk of catastrophic loss, but within a group catastrophe exposure is compartmentalized in one affiliate to insulate the rest of the group from adverse outcomes.

Evidence is presented consistent with internal reinsurance costing less than external reinsurance. Results show that the proportion of assets invested in tax-favored securities is positively related to demand for internal reinsurance, but not external reinsurance. One explanation of this result is that the cost of internal reinsurance is less than the expected cost of not realizing the tax shield on tax-favored investments, while information and agency problems raise the cost of external reinsurance above that of potentially wasted tax shields.

Notes

As a robustness check, Mayers and Smith (1990) use a subsample of single unaffiliated insurers.

Because our data include only four relatively large cross sections, we employ robust standard errors rather than group fixed effects. Results from fixed effects estimation are consistent with those from standard errors robust to group clusters.

Because inter-company pooling cannot occur among unaffiliated insurers, the adjustment for pooling only affects the denominator in the measure of external reinsurance.

According to IRS form 1120pc the federal income tax schedule for property-casualty insurers becomes a linear function for income in excess of $18,333,333. This number must be considered a rough estimate because it does not fully account for implications of the Alternative Minimum Tax introduced in 1986.

If consumers assume that they will be able to pierce the corporate veil in the event of the insolvency of their group-affiliated insurer, then this relation between default risk and reinsurance would only be expected to hold for external reinsurance.

One line of business, commercial multiple peril, is omitted to avoid singularity in the model. This line is chosen arbitrarily. The choice of omitted line does not impact the results.

This definition of a primarily reinsurance firm is used by A.M. Bests in insurance publications. It was also used by Cole and McCullough (2007).

References

Alchian A (1969) Corporate management and property rights. In: Manne H (ed) Economic policy and the regulation of corporate securities. American Enterprise Institute, Washington, DC, pp 337–360

A.M. Best (2005) Rating members of insurance groups. A.M. Best, Oldwick, NJ. Available from http://www.ambest.com/ratings/membergroups.pdf (accessed 9/03/2006)

BarNiv R, Hershbarger RA (1990) Classifying financial distress in the life insurance industry. J Risk Insur 57:110–136

Berger LA, Cummins JD, Tennyson S (1992) Reinsurance and the liability crisis. J Risk Uncertain 5:253–272

Carson JM, Hoyt RE (1995) Life insurer financial distress: classification models and empirical evidence. J Risk Insur 62:764–775

Cole CR, McCullough KA (2006) A reexamination of the corporate demand for reinsurance. J Risk Insur 73:169–192

Cummins JD, Harrington SE, Klein R (1995) Insolvency experience, risk-based capital, and prompt corrective action in property-liability insurance. J Bank Financ 19:511–528

D’Arcy SP, Garven JR (1990) Property-liability insurance pricing models: an empirical evaluation. J Risk Insur 57:391–430

Fazzari SM, Hubbard RG, Petersen BC (1988) Financing constraints and corporate investment. Brookings Pap Econ Act 1:141–195

Garven JR, Loubergè H (1996) Reinsurance, taxes, and efficiency: a contingent claims model of insurance market equilibrium. J Finan Intermediation 4:74–93

Garven JR, Lamm-Tennant J (2003) Demand for reinsurance: theory and empirical tests. Assurances 7(3):217–238, July

Gertner RH, Scharfstein DS, Stein JC (1994) Internal versus external capital markets. Q J Econ 109(4):1211–1230

Greenwald B, Stiglitz JE, Weiss A (1984) Information imperfections in the capital market and macroeconomic fluctuations. Am Econ Rev 74:194–199

Gron A (1999) Insurer demand for catastrophe reinsurance. In: Froot KA (ed) The financing of catastrophe risk. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Jean-Baptiste EL, Santomero AM (2000) The design of private reinsurance contracts. J Financ Intermed 9:274–297

Lamm-Tennant J, Starks LT (1993) Stock versus mutual ownership structures: the risk implications. J Bus 66(1):29–46

Mayers D, Smith CW (1982) On the corporate demand for insurance. J Bus 55(2):281–296

Mayers D, Smith CW (1987) Corporate insurance and the underinvestment problem. J Risk Insur 54:45–54

Mayers D, Smith CW (1990) On the corporate demand for insurance: evidence from the reinsurance market. J Bus 63:19–40

Myers SC (1977) Determinants of corporate borrowing. J Financ Econ 5(2):147–175

Myers SC (1984) The capital structure puzzle. J Finance 39(3):575–592

Myers SC, Majluf NS (1984) Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. J Financ Econ 13:187–221

Petroni K, Shackelford D (1995) Taxation, regulation, and the organizational structure of property-casualty insurers. J Account Econ 74(3):229–253

Pottier SW, Sommer DW (1999) Property-liability insurer financial strength ratings: differences across agencies. J Risk Insur 66(4):621–642

Sommer DW (1996) The impact of firm risk on property-liability insurance prices. J Risk Insur 63(3):501–514

Warner J (1977) Bankruptcy costs: some evidence. J Finance 32:337–348

Webb BL, Harrison CM, Markham JJ (2002) Insurance operation and regulation. American Institute for Chartered Property Casualty Underwriters/Insurance Institute of America, Malvern, PA

Williamson O (1975) Markets and hierarchies: analysis and antitrust implications: a study in the economics of internal organization. Free Press, New York

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Financial support for this research was provided by a Terry-Sanford Research Grant from the Terry College of Business, University of Georgia.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Powell, L.S., Sommer, D.W. Internal Versus External Capital Markets in the Insurance Industry: The Role of Reinsurance. J Finan Serv Res 31, 173–188 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-007-0007-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-007-0007-2