Abstract

Using West German panel data constructed from the 1988 and 1994/1995 wave of the DJI Familiensurvey, we analyze the stability and determinants of individuals’ total desired fertility. We find considerable variation of total desired fertility across respondents and across interviews. In particular, up to 50% of individuals report a different total desired fertility across survey waves. Multivariate analysis confirms the importance of background factors including growing up with both parents, having more siblings, and being Catholic for preference formation. Consistent with the idea that life course experiences provide new information regarding the expected costs and benefits of different family sizes, the influence of background factors on total desired fertility is strong early in life and weakens as subsequent life course experiences, including childbearing, take effect. Accounting for unobserved individual heterogeneity, we estimate that an additional child may increase the total desired fertility of women with children by 0.14 children, less than what conventional estimates from cross-sectional data would have suggested.

Résumé

Sur la base du panel de données d’Allemagne de l’Ouest constitué à partir des vagues de 1988 et 1994/95 de l’Enquête Famille “DJI Familiensurvey”, nous analysons la stabilité et les déterminants de la fécondité totale désirée par les individus. Une variation considérable de la fécondité totale désirée apparaît entre individus et entre interviews. En particulier, jusqu’à 50% des individus déclarent une fécondité totale désirée différente d’une vague d’enquête à l’autre. L’analyse multivariée confirme l’importance des facteurs de contexte pour la formation des préférences en la matière, y compris le fait d’avoir grandi avec ses deux parents, d’avoir plus de frères et soeurs ou d’être de religion Catholique. En accord avec l’idée que les expériences vécues apportent des informations nouvelles par rapport au coûts et bénéfices de différentes tailles de famille, l’influence des facteurs de contexte sur la fécondité totale désirée est forte au début de la vie, et s’affaiblit au fur et à mesure des expériences, y compris de la procréation. En prenant en compte l’hétérogénéité individuelle non observée, nous estimons qu’un enfant de plus pourrait élever la fécondité totale désirée par les femmes ayant déjà des enfants de 0.14 enfant, un résultat en deçà de ce que laisseraient supposer les estimations conventionnelles basées sur des données transversales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As period fertility has fallen below replacement level in most developed countries and total cohort fertility rates confirm a dramatic decline in completed fertility (see Frejka and Calot 2001; among others), population researchers have increasingly turned to fertility intention and preference data to look for clues regarding future trends in fertility and to gain insight into the determinants of fertility behavior.

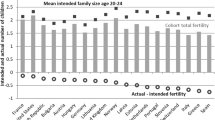

The renewed interest in these measures is reflected in the diverse and growing body of empirical work using instruments of fertility intentions and preferences from large surveys. Studies that seek to document trends in fertility desires across cohorts and regions have shown that the average number of children individuals want has fallen, consistent with the observed decline in actual fertility (Lutz 1996; Bongaarts 2001).Footnote 1 Recent findings from this line of research indicate that while the average number of children wanted has remained above two in most Western European countries, the personal ideal number of children is now below replacement in Germany and Austria (see Goldstein et al. 2003).

A major line of this research seeks to assess the predictive qualities of these measures at the individual level (Coombs 1979; Thomson et al. 1990; Morgan and Chen 1992; Schoen et al. 1999; Joyce et al. 2002: all U.S.; Symeonidou 2000: Greece; Menniti 2001: Italy; Noack and Østby 2002: Norway; Van Hoorn and Keilman 1997: 11 Western European countries and U.S.; Van Peer 2002: 9 Western European countries).Footnote 2 Several authors explicitly examine the determinants of the gap between fertility outcomes and stated fertility (Coombs 1979; Freedman et al. 1980; Hendershot and Placek 1981; Thornton et al. 1984; Thomson et al. 1990; Thomson 1997; Quesnel-Vallée and Morgan 2003: all U.S.; Löhr 1991; Heiland and Prskawetz 2004: West Germany; Symeonidou 2000: Greece; Menniti 2001: Italy; Noack and Østby 2002: Norway; Van Peer 2002: 9 Western European countries; Adsera 2005: Spain). Finally, several authors have analyzed the determinants of individuals’ fertility intentions and preferences directly. This literature includes articles using data from the low fertility regions of Europe (Philipov et al. 2004: Bulgaria and Hungary; Gisser et al. 1985; Engelhardt 2004: Austria; Freedman et al. 1959; Löhr 1991; Kreyenfeld 2001; Heiland et al. 2005: Germany; Monnier 1987: France; Calhoun and De Beer 1991: The Netherlands; Testa and Grilli 2006: EU-15) as well as from the U.S. (Freedman et al. 1965; Schoen et al. 1997; Miller and Pasta 1995, Hirsch et al. 1981; among many others).

Existing studies using measures of fertility intentions and preferences have relied primarily on cross-sectional samples, i.e. samples that contain only one measurement per person.Footnote 3 If individuals’ fertility desires are fairly stable over the life course (and determine fertility behavior), then knowledge of a person’s total desired fertility when young provides useful information regarding their expected completed fertility. On the other hand, if the desired family size varies over the life course, then a single (early) measurement may be of little value to predict subsequent fertility outcomes. In that case, understanding who is likely to change their stated fertility and what factors cause adjustments (and by how much) will be important to obtain better predictions from fertility intention and preference data. Given the lack of studies using longitudinal data on individuals’ fertility intentions and preferences, however, little is known, for example, about the extent to which individuals’ total wanted fertility is stable, which individuals are likely to adjust it, and what factors attenuate its predictive strength.

This paper attempts to address these issues using a measure of individuals’ total wanted (desired) fertility from West German longitudinal survey data collected in 1988 and 1994/95. We find that up to 50% of individuals report a different total desired family size across the two survey waves (6–7 years apart) and stability is only slightly higher among older individuals. The results confirm the importance of background factors including growing up with both parents and more siblings and being Catholic for preference formation. As conjectured, these background factors affect the total number of children wanted early in life and their impact weakens over time as later life course experiences, including childbearing, take effect. Multivariate analysis of the determinants of total desired fertility suggests that women with children respond more strongly to further childbearing. Fixed effects estimates suggest that an additional child may increase total desired family size for women with children by about 0.14 children.

2 Conceptual Background and Existing Evidence

Fertility research conceptualizes childbearing as the outcome of a decision-process that involves (1) biology (age and fecundity), (2) control over contraception (availability, knowledge, cost, social factors), (3) chance (fertility as unintended outcome of sexual activity; contraception and abortion have reduced the number of chance births), and (4) a person’s desire or preference for children (e.g., Friedman et al. 1994, p. 376; Rindfuss et al. 1988, p. 17). This suggests that fertility desires are an important dimension of attained fertility, especially in developed countries where there is less concern over lack of control over conception.Footnote 4

Fertility desires or preferences capture how individuals rank different fertility sizes given their relative assessment of the net benefits associated with different family sizes. A woman’s wanted or desired fertility then captures “the number of children a woman would choose to have at the time of the survey, based on her assessment of the costs and benefits of childbearing and with complete control over her fertility,” (Bongaarts 1990, p. 488; see also Easterlin 1978; McCleland 1983). Several theories regarding the determinants of (wanted) fertility have been proposed. Since they provide important theoretical background for formulating hypotheses regarding the stability of individuals’ stated fertility and help identify its determinants, we survey them briefly in the following section.

2.1 Determinants of Fertility Desires

2.1.1 Benefits and Costs of Children

Children may provide their parents with a special type of pleasure (Becker 1960, Becker and Lewis 1973, Willis 1973, Caldwell 1982). It may reflect any number of direct benefits of children including extending one’s legacy beyond one’s lifetime, avoiding an impersonal lifestyle, obtaining stimulation and an element of surprise, providing an opportunity to teach and exercise control, satisfying the need to experience one’s creativity, and to feel competent and accomplished (see Schoen et al. 1997 and Friedman et al. 1994 for recent surveys). Friedman et al. (1994) propose an additional motive for wanting children: uncertainty reduction (‘Uncertainty Reduction Hypothesis’). They argue that stable careers, marriage, and children are the three commitments to “reduce uncertainty by embedding actors in recurrent social relations” (p. 381).

Schoen et al. (1997; also Astone et al. 1999; Huinink 1995), extending Coleman (1988), argue that the continuing desire for children may be due to resources that become available through greater social ties and social exchange when individuals have a family (e.g., emotional, physical, or financial support from family members, other relatives, and friends). Huinink (2001, p. 5), a prominent observer of fertility development in Germany, suggests that the social capital provided by children in modern societies is “not serving for skill and material oriented support anymore but psychological and identity sustaining support.”

Hoffman and Manis (1979) show in U.S. survey data that individuals associate children with a number of these intrinsic values. Also using U.S. data, Schoen et al. (1997, p. 349) find “strong support for the hypothesis that persons for whom relationships created by children are important considerations in childbearing decisions are more likely to intend to have a (another) child.” Since there is little documentation to date of how individual characteristics may relate to these perceived intrinsic benefits, these sources of child benefits do not readily lead to specific predictions in the context of total desired fertility. However, it is clear that the value-of-children hypotheses predict greater desires for a large family among individuals who perceive greater benefits from children in any of these dimensions.

Childbearing and rearing is associated with a number of costs including the parental time and economic resources required to raise the children. The value of these resources depends on what alternative uses are available to the parents (Becker 1960; Becker and Lewis 1973; Willis 1973). For example, having a child may be more costly to parents who are highly educated (have a high earnings potential in the labor market) since they would have to forego a greater amount of income when allocating their time to childrearing.

Individuals’ fertility desires are expected to reflect a person’s assessment of the (expected) benefits and costs of different family sizes. As a result, new information regarding the costs of children as well as the benefits from alternative uses of the resources may lead to an adjustment of the desired family size.Footnote 5 Since many of the benefits associated with children can be realized by having only one child while the costs may be more closely (and positively) related to family size, total desired fertility may be particularly responsive to changes in the expected costs of having children.

2.1.2 Societal Fertility Norms

Researchers have long recognized the possibility that family size norms play a role in fertility desires and attainment (Freedman et al. 1959; Blake 1966; Gustavus and Nam 1970; Caldwell 1982; Preston 1987; Rindfuss et al. 1988; Kohler 2001; among others). Many observers believe that an increasing acceptance of non-traditional life styles such as voluntary childlessness and a greater emphasis on personal fulfillment (which conflicts with the traditional high fertility family according to the argument) contributes to the decline in fertility (e.g., Lesthaeghe and Surkyn 1988; Van de Kaa 1987, 2001). The characteristic frequency distribution of family size is taken to be, at least in part, the result of norms regarding how many children individuals ought to have. Mechanisms to sanction individuals who deviate from the norm range of children may be in place (see Rindfuss et al. 1988, p. 20; Gustavus and Nam 1970, p. 44).

These non-compliance costs can affect desired fertility since they change the expected net benefit associated with different family size alternatives (including not having children at all). The social norm hypothesis suggests that stated fertility may differ across individuals who are subjected to different norms or who differ with respect to their tolerance to social pressures. Wanted fertility may change over a person’s lifetime as the acceptable number (or range) changes or the person’s tolerance changes. In the first case, the desired family size will change in the direction of the fertility norm, whereas if a person grows more tolerant (or there is less pressure to conform to any particular fertility norm) then desired fertility is expected to reflect more strongly other aspects of individuals’ benefits and costs of children.

2.1.3 Resources

Family resources (monetary as well as non-monetary) may make a larger family more affordable. The presence of a partner and the size of the extended family likely mean that additional support and resources are available. We note, however, that Becker and Lewis (1973) argue that greater income prospects do not necessarily lead to larger families. According to their child quantity–quality model, a person with greater (expected) family income may plan for a smaller family (less child quantity) and concentrate resources toward enhancing the achievement of each child (child quality). In any case, to the extent that the economic situation and/or the partnership changes (e.g., as a result of unemployment or separation), individuals may adjust their desired family size up or down.

2.1.4 Behavioral Predispositions

Fertility motivations may also have a biological root. Udry (1996) argues that fertility behavior is genetically predispositioned. Kohler et al. (1999) provide evidence from historic Danish twin data that genetic influences explain up to 50% of the variation in attained fertility within cohorts. They conclude that genetic influences in conjunction with (varying) social conditions (including fertility norms) shape fertility motivations and desires. Miller et al. (1999, p. 55) conjecture that the “motive forces underlying human childbearing can be said to some extent to be ‘hard-wired’ into the central nervous system,” and show that genetic variation related to the organism’s responsiveness to environmental influences regarding reproduction and survival contributes to the explanation of individuals’ self-reported childbearing motivations. While the biological predisposition may differ across individuals (and the evidence mentioned seems to support this), it is unlikely to change over a person’s life course.

2.2 Existing Evidence

Fertility researchers have long recognized the possibility that individuals’ perception of the benefits and costs of children may be shaped through early experiences with family life during parental socialization. Duncan et al. (1965, p. 514) conjecture that “[s]ocial interaction in [children’s] families of orientation influence them so profoundly and interaction in their families of procreation is so important to them and calls for so many different decisions that they will tend to recreate a familiar setting resembling the one in which they grew up in order to mobilize familiar resources, relationships, and roles. ” Consistent with the idea that early experiences in the family of origin influence a person’s fertility desires, studies have documented effects of parental fertility behavior on desired fertility (Huestis and Maxwell 1932; Kantner and Potter 1954; Hendershot 1969; McAllister et al. 1974; Stolzenberg and Waite 1977; Hirsch et al. 1981).

Gustavus and Nam (1970) provide evidence that early socialization influences fertility preferences using a measure of ideal family size from a sample of sixth, ninth, and twelfth graders in two Southern counties of the U.S. In one of the first efforts to analyze the stability of fertility preferences, they discuss the possibility that the influence of background factors may change over time. Specifically, they note that (p. 50) “size of family of orientation seems less clearly related to ideals among the twelfth graders than among younger students, and socioeconomic factors seem to be more clearly related to ideals among the older students.” The possibility that fertility desires are formed early in life but are subsequently modified by life course events has been investigated in detail in Udry (1983). He considers adjustments to individuals’ intended family size by parity and finds evidence in favor of sequential adjustment of fertility plans over the life course.

Among life course events, own childbearing experiences have been found to exert an influence on fertility intentions and desires in U.S. samples. Freedman et al. (1965) report a greater expected family size among women who experience a pregnancy using longitudinal data on married women in the Detroit area in the early 1960s. More recently, and using a measure of desired family size, Miller and Pasta (1995) document a positive association between childbearing and desired fertility among a sample of married individuals from the San Francisco Bay Area. On the other hand, using Austrian panel data and comparisons of sample means, Gisser et al. (1985) examined whether the personal ideal number of children fell after women experienced their first birth and found no evidence to support what was known at that time as the ‘Baby-Shock Hypothesis.’

Recent studies on individuals’ fertility intentions and desires in European populations have documented influences of various life course events on different measures of fertility preferences. Philipov et al. (2004) find that the intention to have a first or second child decreases with the age of a woman in Bulgaria and Hungary. Engelhardt (2004) finds that married and divorced or separated women in Austria desire a larger family size than those who are never-married. She also provides some evidence that women who are employed full-time at the time of the interview desire a smaller family than women who spend less time in the labor market. Heiland et al. (2005) provide evidence from West German and Eurobarometer (EU 15 nations) data that upper-secondary and tertiary education may increase the total number of children wanted.

With the exception of the (mostly descriptive) works by Freedman et al. (1965), Gisser et al. (1985), and Miller and Pasta (1995), existing studies on the determinants of fertility preferences rely on cross-sectional data, limiting the researcher’s ability to study the stability of individuals’ total desired fertility. This paper employs individual-level panel data and descriptive as well as multivariate analyses to investigate the characteristics of respondents with stable family size desires over a 6- to 7-year period, and potential causes of preference adjustment. While previous findings have provided some evidence in support of the idea that individuals’ experiences (such as childbearing) may have a causal effect on fertility intentions and preferences, existing estimates of these effects may suffer from omitted variables bias. The longitudinal data enable us to provide estimates of the effect of life course experiences on total desired fertility from models that allow for arbitrary correlation between observed life course factors and unobserved individual-specific determinants of fertility desires as discussed in the next section.

3 Hypotheses and Empirical Strategy

The conceptual background discussion provides reasons to expect that the wanted (preferred) number of children varies with individuals’ experiences and life course events. If different family sizes constitute different net benefits to individuals (due to instrumental and non-instrumental values of children and social pressures), we expect a person’s total desired number of children to change as new information which alters the family size that the person associates with the highest net benefit becomes available. Given this conceptual background we can now formulate hypotheses regarding the sets of influences and individuals factors associated with instability and a higher or lower level of total desired fertility, respectively.

3.1 Hypotheses

We will examine three groups of potential determinants of stability and the level of total desired family size: (1) individual background characteristics such as gender, religion, and attitudinal measures; (2) family background factors and early influences such as whether the person grew up with both parents and how many siblings he or she has; (3) subsequent life course events including marriage, divorce/separation, secondary and tertiary schooling, child birth, health, financial conditions, and labor force status.Footnote 6

We expect young individuals’ perceptions of the benefits, costs, and resource requirements associated with different family sizes to be influenced by family background experiences and individual characteristics. Over time, as individuals are subjected to other life course experiences, earlier influences may become less predictive of the desired number of children and hence less relevant for stability. This suggests that the effect of background factors and life course experiences on total desired fertility and its stability may vary by age. These effects may also differ by past experiences. In particular, we conjecture that childbearing and rearing may have a lasting impact on a person, resulting in individuals with children responding differently to life course events than respondents without children.

In addition to testing hypotheses regarding the overall significance of background and life course influences, we will also investigate specific effects. In particular, we expect Catholics to report a higher total desired family size than individuals with other religious affiliations as the social stigma of having a small or no family may be particularly strong for this group. To the extent that the influence from the traditional ideal of a large family associated with Catholicism gives way to a smaller desired family size over time, Catholics’ desires may be less stable (when young). Respondents who grew up with both parents may be more likely to desire a larger family since the traditional family arrangement may be more familiar and they may be able to count on greater parental support and economic resources compared to those who were raised by an only-parent. As a result, the former individuals may desire more children, on average, and be less likely to adjust the desired number. Similarly, having more siblings is expected to increase desired family size and stability as individuals with a larger family network may have more support to accommodate a large family.

Employment, marriage, more income, and education and training are expected to make a larger family more affordable and—to the extent that these increases in resources are unanticipated and individuals care sufficiently for a larger family—may hence increase the desired number of children (‘Resource Hypothesis’). However, the effect of resources on desired fertility may be negative, if richer parents increase total expenditures on children by investing more in the quality of each child in the family (e.g., each child’s education) rather than by increasing the family size (Becker and Lewis 1973). Moreover, more educated individuals may also face greater time opportunity costs of having children. Holding income and employment constant, more schooling or training may hence reduce the desired family size (‘Opportunity Cost Hypothesis’).

A negative income and education effect would also be consistent with the uncertainty reduction hypothesis (Friedman et al. 1994), which predicts that the desire to remain childless should increase as more opportunities to have a stable working career become available. Uncertainty reduction furthermore suggests that the desire to have children should increase as individuals’ prospects in the labor market weaken, a situation that may be reflected in a greater chance of becoming unemployed. Income, education, and stable employment may also serve as insurance against higher than expected costs of having children and hence be associated with greater stability.

3.2 Empirical Strategy

To investigate these hypotheses, we analyze the distribution of individuals’ desired family size by age group, childbearing experience, and gender using descriptive as well as multivariate analysis. Specifically, to test for characteristics associated with instability, we estimate linear probability models of whether individual i’s total desired family size is unstable, i.e. whether the total desired number of children, D, differs across the 1988 and 1994/1995 survey waves:

where Y i,1988 is a vector of individual characteristics from the first survey. To investigate how a set of life course experiences affects wanted fertility, we estimate linear panel models of person i’s desired family size at time t, D i,t :Footnote 7

where X i,t and Z i are measures of time-varying and time-invariant explanatory factors with coefficient vectors β and δ, respectively. The data provide two observations per person corresponding to the two survey waves, t = 1988 and t = 1994/95. Unmeasured individual- and period-specific influences are captured by the error term, u i + ε i,t .

The fixed effects (FE) approach allows for arbitrary correlation between the individual-specific component, u i , and our measures of life course experiences of interest X i,t , thereby reducing the chance of faulty inference.Footnote 8 If there are person-specific characteristics affecting desired fertility that also influence the observed life course experiences, conventional estimates of the effects of the latter may be biased (see McCallum 1972). For example, some individuals may attach a particularly high value to family life as a result of a childhood experience that is unobserved by the researcher. If these individuals are also more likely to get married than the average person, the life course event of getting married may falsely be seen as having a positive effect on the desired number of children.

Systematic differences in responses to the wanted fertility instrument across individuals constitute another important source of individual-level unobserved heterogeneity that, if unaccounted for, may bias the effect of life course factors on wanted fertility. For example, some individuals may be reluctant to reveal in the interview that they prefer a number that deviates from the two-child-norm family (see Livi Bacci 2001). If these individuals were also more likely to experience certain life course events or to be subjected to certain influences (i.e. if the misreporting occurs systematically), then conventional estimates of the effect of these experiences or influences on desired fertility would be biased upward. If there are individuals who consistently over or understate their true number of children wanted, then the fixed effect approach can purge the estimates of misreporting bias since it accounts for unobserved person-specific heterogeneity that may be correlated with life course events.

4 Empirical Analysis

4.1 Data

The data for this study were taken from the 1988 and the 1994/95 wave of the West German Familiensurvey of the German Youth Institute (DJI Familiensurvey 1988, 1994/95).Footnote 9 The first wave gathered data on 10,043 individuals from a random sample of German citizens of aged 18–55 years in 1988 who resided in West German households.Footnote 10 Of all first-wave individuals, 4,997 were interviewed again in 1994/95. We construct our samples from this two-period panel. We exclude individuals with any missing values for desired children (308 initial respondents or 6.2%). We also exclude individuals with incomplete information on educational attainment or training (8), health status (14), labor force status (43), actual number of children (1), traditional values (73), Inglehart Scale (121), income (836), and Catholic (2). In total there are 2,127 women and 1,661 men in our samples. Table 1 presents the definitions of the main variables and the corresponding sample means for women by survey wave (W1 = 1988 vs. W2 = 1994/95), age (age 18–25 in 1988 vs. age 26–35 in 1988), and actual fertility (childless in 1988 vs. w/children in 1988).

4.1.1 Measure of Wanted Fertility

Like most studies on fertility intention and preferences, we rely on a measure of the most preferred number of children (‘first preference’).Footnote 11 Our measure of total wanted (desired) fertility is based on the instrument If it was entirely up to you: How many children in total do you want or rather would you have wanted? Footnote 12 , Footnote 13 The answer is coded on a scale from zero to four with the maximum representing four or more children.Footnote 14 Given the qualification “if it was entirely up to you,” this instrument emphasizes the individual’s own wanted fertility and may hence have a greater tendency to abstract from the influence of parents, a partner, or society.Footnote 15 Of course, individuals may have internalized external views on the acceptable family sizes as a result of (social) interaction and sanctioning (Rindfuss et al. 1988, p. 20). Since the instrument is designed to measure wanted fertility of respondents of all ages, including those who have completed their reproductive period, older individuals will respond to the retrospective part (“How many children in total would you have wanted?”).Footnote 16 It is not clear that this affects how individuals respond to the question, but in order to minimize interpretational concerns, we conduct the analysis separately by age group and childbearing experience as of the initial interview (see Sect. 3) and focus on individuals early in their reproductive span, the group least likely to respond to the retrospective part of the question. In addition, all multivariate models that we estimate control for respondents’ age and the panel estimates correct for unmeasured differences in survey responses across individuals as discussed above.

4.1.2 Sample Descriptives

As shown in Table 1, the majority of respondents want two children. More than 20% of female respondents aged 18–25 years at the first interview desire three children and a sizable fraction wants four or more children. Among young women without children at the time of the first interview, 7% state childlessness as their preferred family size, while 5% want exactly one child. Women with children report higher desired family size than childless women. The sample descriptives also provide some evidence that the desired family size declines for women who are initially childless while it is approximately constant for women with children. We also find that the desired number of children is greater for women than men (not shown).

About 45% of women aged 18–25 years in 1988 experience a birth in the 6- to 7-year period between the interviews regardless of whether they have children initially or not. On the other hand, 41% of women aged 26–35 years and childless in 1988 have a child in 1994/95, compared to 25% of women in that age group that already had children. As expected, individuals are more likely to be single (less likely to be married, separated or divorced) when they are younger or childless. The average person reports to be in good health and younger respondents tend to be in better health than older ones. Labor force participation increases over the life course at the expense of home production, schooling, and other activities outside the labor force. This is especially true for women who started childbearing early. Consistent with greater labor force participation, schooling, and transition into a stable relationship over time, the descriptives show that household income levels rise with age.

The most common educational attainment is a basic high school degree with job training (about 60%).Footnote 17 Some respondents complete post-secondary schooling between waves: Among 18- to 25-year-old childless women in 1988 the fraction with a college degree is 2% compared to 10% in 1994/95. As expected, women in the same age group who started childbearing earlier are more likely to have completed their education and their educational attainment tends to be lower. On average, men have slightly greater educational attainment than women (e.g., overall 18% of men graduated from college compared to 10% of women; results not shown).

We find that women who have children early are more likely to be Catholic, to live in rural areas, and to agree with the statement that women should work less in the labor market than men. Overall, about 40% of respondents report that they are Catholic and men hold more conservative views on gender roles than women. About one third of the respondents express strong post-materialistic values according to the Inglehart scale compared to 8–11% with strong materialistic views (results not shown).Footnote 18 More than 80% of the respondents grew up with both parents in the household (as opposed to with one parent only), and the majority of respondents have one or two siblings. Respondents with fewer siblings are also more likely to be childless at the first interview.

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Distribution of Total Desired Fertility

Table 2 displays the distribution of women’s desired number of children at the second interview conditional on stated fertility as of the initial interview (desired fertility in 1988 varies vertically and horizontally for 1994/95) by age group and childbearing history (childless vs. with children) at the initial interview. The table also indicates statistically significant differences in average stability among women in the same age range and fertility history (relative to the stable two child desire) and across women with different initial fertility (initially childless women in the same age range are the reference group).

The distribution shows that the majority of women report the same number in the 1994/95 survey as in 1988 (see elements in bold on diagonal). Overall stability is lowest (48.9%) for women aged 18–25 years in 1988 who had started a family by then and highest (64.5%) for women aged 26–35 years in 1988 with family. Younger women without a child at the initial interview report the same number 57.4% of the time, a level similar to that of older initially childless women. Additional results show that overall stability reaches 67% for individuals at the end of (or past) their reproductive life span. The overall stability pattern is similar for men and women. However, men with children at the first interview appear to be more likely to lower their desired family size over time compared to women. (These results are available from the authors upon request.) The frequent adjustment to the wanted family size that is apparent in these descriptives is not an isolated finding. Calculations based on the responses to a similar measure of wanted fertility among (recently) married Austrian women first interviewed in 1978 with a follow-up in 1981/82 indicate that 59.5% of these women did not change their desired number of children over the 3-year period (Gisser 1985, p. 51).

Table 2 also shows that the instability of desired family size among young women who are initially childless is primarily due to reductions in the desired number of children across interviews. The fraction of these women who want three children declines from 21.6% at the time of the first interview to 16.7% six years later while the fraction of women who desire one child rises from 5.4 to 14.7%. Women in the same age group who already had at least one child when first interviewed desire larger families throughout compared to their counterparts without children and the former are about equally likely to revise up or down. The greater likelihood of a downward adjustment among those without family initially may reflect (unexpected) difficulties in transitioning into stable partnerships and marriage.Footnote 19 A similar pattern holds for women age 26–35 with children in 1988; the changes, however, are less pronounced, resulting in greater overall stability of total desired fertility. Stability among women in this age group who did not have children at the first interview is significantly lower (55.7 vs. 64.5%), and these women tend to reduce their total desired fertility between interviews.

Another interesting pattern is the stability of wanted fertility among those reporting two as the total desired number of children in the first interview. Those stating two initially report the same number again at the follow-up interview in the majority of cases, i.e. display significantly greater stability than individuals with a different initial desired family size. The differential stability of wanted family size by initial desire may originate either from differential responsiveness or from different experiences between interviews. To systematically analyze the patterns of adjustment in desired fertility, including the greater stability of those reporting two children as desired initially and the tendency for women with children to revise their total desired number of children upward and for young women without children to adjust them downward, we now turn to multivariate models of stability and desired fertility.

4.2.2 Multivariate Evidence

Columns 1 and 2 in Table 3 show estimates from linear probability models of changing fertility desires for women by age groups. These models are useful to identify background characteristics and experiences associated with subsequent change in total desired fertility. The reference woman (omitted categories) is married and lives with the spouse, has a basic high school education and job training, is currently employed, and has strong post-materialistic views (Ingle Type PPM). The estimates provide some evidence that women aged 18–25 years who are Catholic change their desired fertility more frequently than other women. Religious background, however, does not appear to play a role at a later point in life. The results in Table 3 may explain the somewhat greater instability among young women with children (relative to women without children; see Table 2), since Catholic women are more likely to start childbearing early (see Table 1). As they are more likely to be concerned with family development at a young age, Catholics may be more responsive to information regarding the costs and benefits of having a larger family. The data support the interpretation that many hold a desire to realize a traditional large family when young and lower their desired fertility subsequently.Footnote 20

Growing up in an intact family and completion of a college preparatory high school degree are other early experiences that appear to affect subsequent stability. Young women who were raised in a two-parent household are 18% less likely to change their desired fertility across the two surveys compared to women who did not grow up in an intact family. Women aged 18–25 years whose highest degree at the time of the first interview was a college preparatory high school degree, and who may have had additional training, are 20% more likely to change their desired family size between surveys. We note that many of these women are attending college between the initial and the follow-up interview (see Table 1). A positive family experience during childhood may result in strongly held desires for a large family and greater ability to cope with the demands of family life. The greater instability associated with the college preparatory high school degree is consistent with more education resulting in higher opportunity costs as well as income, causing some women to revise their expected costs from a larger family downward and some upward.

The estimates in column 2 in Table 3 also provide some support that life course experiences become more important for stability over time while the influence of family background factors diminishes. Among women aged 26–35 years in 1988, those with greater household income at the first interview display more stable desired fertility, while women who experienced a divorce or separation tend to change their desired family size more frequently. As discussed above, economic resources may serve as insurance against factors that negatively impact the expected value of children. Divorce or separation appears to increase a person’s responsiveness to subsequent life course events related to the costs of children, reflecting, perhaps, lack of continuous support.

Returning to our earlier observation that individuals who initially report two children as desired display the highest stability of desired fertility (see Table 2), additional analysis reveals that individuals reporting a desired family size of two at the first interview differ from other respondents with respect to important attributes and experiences. The former are more likely to have grown up in an intact family and less likely to have experienced a divorce or a separation. As discussed above, the stability analysis shows that these are experiences (or lack thereof in the case of divorce and separation) that are particularly predictive of greater stability.

Columns 3–10 in Table 3 report the panel estimates of the determinants of total desired number of children among women aged 18–25 years and women aged 26–35 years in 1988 (wave 1) by childbearing experience in 1988.Footnote 21 , Footnote 22 These models help identify to what extent individual background factors and experiences directly affect the level of desired fertility. The models fit the data moderately well with coefficients of determination, R 2, ranging from 0.18 to 0.30 for the RE models to 0.43–0.59 for the FE models. The better fit of the FE models testifies to the importance of person-specific effects that are included in the (adjusted) R 2 calculations. We also find some statistical support against the RE models in favor of the FE models: Hausman specification tests (Hausman 1978) suggest that the hypothesis that the individual-specific effects (the u i ’s in Eq. 2) are uncorrelated with the other regressors—as assumed in the RE approach—is rejected in our samples. This supports the concern stated above that there may be important unobserved time-invariant individual-specific determinants of fertility desires that are correlated with life course experiences, and hence could lead to biased estimates of life course influences if ignored.

While the fixed effects results (FE models) do not reveal which factors exert persistent influence on individuals, the RE results provide evidence that early influences and background factors such as being Catholic and growing up with both parents are associated with a greater desire to have children among young women who were initially childless. The evidence of greater desired fertility and greater instability among young Catholics is consistent with earlier evidence from longitudinal data from the U.S. (Freedman et al. 1965; using a measure of expected family size). Having a larger number of siblings is associated with a greater total desired family size for all childless women, consistent with the earlier literature (Huestis and Maxwell 1932; Kantner and Potter 1954; Hendershot 1969; McAllister et al. 1974; Stolzenberg and Waite 1977; Hirsch et al. 1981; among others). This relationship may be due to greater knowledge of how to cope with family tasks that individuals raised in larger families have acquired (Duncan et al. 1965). It may also reflect societal fertility norms or family-specific characteristics. The absence of these effects among women with children and for older women supports the hypothesis that the effect of background factors and early influences weakens as the childbearing experience and other (more recent) life course influences take effect.

The panel analysis supports the hypothesis that childbearing and rearing affects the total number of children wanted. We find that having children between the first and the second wave increases the total number of children wanted among women with children. The effect is smaller in the FE models which only consider variation over the life course of an individual compared to the RE models but remains significant in the larger sample of women aged 26–35 years with children in 1988 (pooled estimates confirm this result). On average, the number of children wanted increases by 0.14 children based on the within-individual variation for these women. The weaker response to having a(nother) child among initially childless women compared to women who started childbearing earlier is consistent with a downward trend of total desired fertility among initially childless women (see Table 2) while they are at least as likely to have a(nother) child between interviews (see Table 1). The negative age effect in the FE model for young childless women suggests that there are time-varying factors not captured by the observed life course experiences that contribute to this downward trend (see column 4 in Table 3).

While the finding of a positive effect of realized births on desired family size confirms earlier results from U.S. data (Miller and Pasta 1995), our analysis reveals important differences by childbearing history: For initially childless women the effect of having a child on the desired family size is smaller (and statistically not different from zero in most models) than for women with childbearing experience. Consistent with earlier descriptive findings from Austrian data (Gisser et al. 1985) this implies that there is no evidence to support the idea that the experience with the first child causes a significant revision of desired fertility (‘Baby-Shock Hypothesis’). The positive relationship between a higher-order birth and total desired fertility may reflect increasing benefits of having a large family among women who start childbearing early. This group is likely to be more homogenous and shares characteristics (being Catholic and growing up in large families; see Table 1) that are associated with realizing greater perceived benefits from having another child on average.

The effect of experiencing an unemployment spell on desired family size is estimated to be negative and in pooled samples (not shown) this effect is also statistically significant. A negative effect of unemployment is consistent with the ‘Resource Hypothesis’ discussed above and contrary to the ‘Uncertainty Reduction Hypothesis’ (Friedman et al. 1994). The latter would suggest that greater career uncertainty should make childbearing and becoming a stay-at-home mom relatively more attractive (as a way to reduce uncertainty). Greater labor market uncertainty and the resulting income instability should cause larger families to be perceived as relatively less affordable. There is also some evidence (primarily based on the RE estimates) in support of a positive relationship between education and total desired fertility. A positive effect is consistent with earlier findings (Heiland et al. 2005) and may reflect a greater ability to afford a large family among the more-educated (‘Resource Hypothesis’) rather than greater time opportunity costs of having children, which would imply the opposite effect (‘Opportunity Cost Hypothesis’). Controlling for unemployment and education, total desired family size appears unrelated to income, which may be due to collinearity between income and education and unemployment.

While we are aware of one multivariate study (Engelhardt 2004) that finds that never-married women in Austria desire smaller families using cross-sectional data, the transition from single to married or from married to separated or divorced does not systematically affect the level of total desired fertility among West German women (there is some evidence that divorce and separation leads to lower desired fertility among men). The absence of relationship effects may be due to collinearity with the income, education, or unemployment measures or it may be related to the type of instrument used here that explicitly abstracts from partner influences (“if it was entirely up to you”; see Sect. 4.1.1).

While statistical tests indicate that the measures of experiences during adulthood employed in our analysis are jointly significant in most panel models, their explanatory power appears limited. Also, few of the time-varying variables appear systematically related to total desired fertility individually. For example, the estimate of the coefficient of the health status variable tends to be positive, suggesting that women with poorer self-reported health desire a larger family, but the effect is not statistically significant. The limited association between individuals’ experiences during adulthood and desired fertility indicates that the information provided by the experiences observed here has little effect on which family size is associated with the highest net benefit.

4.2.3 Additional Results

We also estimated the models shown in Table 3 for men by age and initial parity and for respondents past the age of 36 at the initial interview. As for women, we find that men who already have children tend to increase their desired total fertility after having another child. There is evidence that divorce and separation negatively affect the desired family size of men. Interestingly, while being unemployed at the time of the interview may lower desired fertility among women, there is evidence that unemployment increases desired fertility among (young) men. Background factors are equally important in explaining total desired family size for men with similar positive effects of respondent’s siblings, being Catholic, and growing up with both parents on desired family size. Lastly, similar effects of life course experiences on desired fertility are observed among men and women aged 36 years and above in 1988 and among respondents aged 26–35 years. Consistently across age groups, we find that additional children raise the desire to have a larger family.

5 Conclusions

We hypothesized that family background and early experiences as well as subsequent life course events influence the expected benefits, costs, and resource considerations that individuals take into account to derive their desired family sizes. Using samples based on representative data from West Germans interviewed in 1988 and 1994/95, we find considerable variation in the total desired number of children across respondents and for the same individual across survey waves. In particular, we document that respondents’ total desired number of children changes in up to 50% of the cases in the 6- to 7-year period between the initial and the follow-up interview. Adjustments of the preferred family size are less common among older individuals but the fraction of respondents with stable family size desires does not exceed 70% in our samples.

Using multivariate analysis we further investigate the determinants of the number of children wanted and the characteristics of individuals who change their total desired fertility. The results confirm the importance of early influences and background factors. Growing up in a two-parent household, having more siblings, and being Catholic are associated with a greater desired family size. Consistent with earlier longitudinal research (Freedman et al. 1965), we are able to identify some individual characteristics that are associated with greater instability. Desired fertility is more likely to change among young Catholics and respondents with higher education, while being raised in an intact family and greater financial resources are associated with greater stability. As conjectured, background factors and early experiences tend to affect total desired fertility and hence its stability early in life and their impact weakens over time as later life course experiences, including childbearing, take effect. These findings provide further support for the longstanding hypothesis that early socialization exercises a strong influence on fertility motivations and desires (Duncan et al. 1965, among many others).

While Gisser et al. (1985) find no evidence that a first-birth affects fertility desires among Austrian women, Miller and Pasta (1995) report a positive association between childbearing and the desired number of children in similar data from the San Francisco Bay Area. Our finding of a positive effect of childbearing on total desired family size among women who already started childbearing, even after accounting for individual-specific unobserved heterogeneity correlated with desired and actual fertility, reconciles the earlier results. It suggests that higher-order births increase, on balance, the net benefits associated with a larger family. We conclude with Miller and Pasta (1995, p. 196) that “childbearing itself should be included among the factors that tend to attenuate the predictive strength of child-number desires...,” but note that our evidence from fixed effects models suggests that the true effect of the childbearing experience on a person’s total desired fertility may be smaller than conventional evidence based on cross-sectional data would suggest.

Overall, the life course experiences that we investigate show relatively little systematic association with the observed variation in individuals’ total desired family size. This does not necessarily mean that individuals’ fertility desires are noisy or unreliable in predicting individual behavior. In fact, while studies on the predictive validity of fertility intention and preference data at the individual or aggregate level frequently echo these concerns, they also find that these measures tend to have greater validity than other individual characteristics (Westoff and Ryder 1977; Van Hoorn and Keilman 1997; among others), suggesting that they contain information that is valuable to understand subsequent fertility behavior. The somewhat limited explanatory power of the models documented here may be overcome with richer data on life course events, experiences, and conditions affecting the individuals’ perceived costs and benefits of different family sizes. Specifically, further evidence on the longitudinal properties of fertility intentions and preferences using longer panels with more closely spaced observations, richer sets of controls for life course events than available in the DJI Familiensurvey, different measures of total desired fertility, and from different regions is needed. In addition, future research may use the estimates of total desired fertility models like the ones presented here to assess whether individuals’ predicted desired fertility can serve as a better signal of subsequent fertility behavior than individuals’ stated desires.

Notes

Among West German women, for example, completed cohort fertility has fallen from 2.2 to 1.6 children per women between the 1935 and the 1956 birth cohorts, while the corresponding desired number of children is estimated to have declined from 2.5 to 2.2 (see Heiland et al. 2005, Fig. 1). Other studies report on the trends for specific countries or regions (e.g., Toulemon 1996, 2001 for France).

The predictive value of preference data has been controversially debated for at least four decades (see Blake 1966; Westoff and Ryder 1977; Westoff 1981; and Long and Wetrogan 1981 for early critiques based on U.S. data and Van Hoorn and Keilman 1997 and Hagewen and Morgan 2005 for recent surveys of this literature).

Notable exceptions are Freedman et al. (1965), Gisser et al. (1985), Miller and Pasta (1995), and Quesnel-Vallée and Morgan (2003). Freedman et al. (1965) study the characteristics associated with revisions in expected family size during the first two years of marriage among a sample of couples in the Detroit area interviewed annually between 1961 and 1963. Gisser et al. examined fertility preferences of married women in Austria interviewed in 1978 and 1981/82. Miller and Pasta study the determinants of fertility motivations and preferences in a small sample of married individuals from the San Francisco Bay Area. Unlike the present article, Quesnel-Vallée and Morgan do not focus on the determinants of fertility preferences but study the gap between birth intentions and subsequent fertility outcomes.

We note that attained fertility and wanted fertility could diverge if there are significant social influences that are reflected in attained fertility but not in wanted fertility. As discussed in Bongaarts (1990), actual and wanted fertility can also differ due to biological forces, chance, or competing objectives. Recent evidence from European populations shows that achieved family size falls short of the desired one rather than the other way around (Heiland et al. 2005; Noack and Østby 2002; Van Peer 2002; Symeonidou 2000; Van Hoorn and Keilman 1997).

To what extent individuals, on average, correctly anticipate the benefits and costs of having (a particular number of) children is unclear. Udry (1983), for example, argues that fertility plans are updated at each parity. Evidence from individuals’ retirement behavior, for example, suggests that individuals are able to formulate very accurate expectations regarding the timing of their retirement (Benítez-Silva and Dwyer 2005).

The Familiensurvey does not collect data on spousal family size preferences. While we do not limit our sample to individuals with partners, it would be interesting to control for spousal preferences given evidence that they have an independent effect on fertility preferences and actual fertility (e.g., Morgan 1985; Thomson et al. 1990; Thomson 1997; Van Peer 2002; Voas 2003). However, we do not expect this to be a major limitation for those respondents with partners since the instrument of wanted fertility that we use explicitly asks that individuals answer for themselves as discussed below in more detail.

Models that allow for non-linear effects have been used in a cross-sectional context (see e.g., Philipov et al. 2004 and Heiland et al. 2005) but these papers do not provide strong evidence against a linear specification. The advantage of our statistical approach over alternative strategies allowing for non-linearities is its ability to account for person-specific unobserved heterogeneity that may be correlated with the time-varying variables as discussed below.

The limitations of this estimation strategy are well-known. In particular, fixed-effects estimates may be considered inefficient as they do not utilize the variation across individuals. This also implies that the effect of time-invariant individual characteristics cannot be identified. For a more detailed discussion of the assumptions of fixed effect panel models see Wooldridge (2002).

Data from the most recent wave of the DJI Familiensurvey (2000) are not used in this study since the survey instrument on desired number of children does not compare to the earlier waves.

Since individuals living in East Germany were not sampled until after the reunification (they were sampled in 1994/95), the panel starting in 1988 does not contain respondents from East Germany. For details on the sample construction and the comparisons to census data see Bender et al. (1996).

Coombs (1974) introduced a scale of family size preference capturing a person’s first, second and third preference using a series of questions on the most-preferred, second-most-preferred, etc. number of children. Unfortunately, the present data do not permit construction of Coombs’ scale.

For further detail regarding the construction of the measure see Heiland et al. (2005).

Morgan (1981 1982) suggests that respondents who answer “don’t know” to questions relating to fertility intentions are an important group that should not be discarded. Unfortunately, in the DJI Familiensurvey a distinction between “don’t know” and missing for other reasons cannot be made. Hence, we do not include this group in our analysis.

Comparison with a similar measure in the 2001 Eurobarometer (EUROSTAT 2001) for West Germany suggests that this cut-off affects only about 1% of the respondents. The maximum number of children reported there is seven.

Studies have employed different instruments of fertility preferences but desired, intended, wanted, or ideal number of children, which are similar to the one used here, are most common. Ryder and Westoff (1969) compare responses to questions on desired, intended, and expected number of children among American women and find insignificant differences between intended and expected number of children and only slightly higher desired numbers of children. Freedman et al. (1959) find higher desired than expected fertility among West German adults in 1958, but their question on desired fertility is qualified by if financial and other conditions of life were very good, which suggests a more hypothetical situation where having children is less costly.

We emphasize that information from older respondents is of interest since it may provide an important contrast to test hypotheses about stability and the determinants of preferred family size. Specifically, individuals may be able to better assess the net benefits of a particular family arrangement later in life, especially if they have children. Hence, we expect their preferred number of children to be more stable.

We constructed five binary indicators to measure different levels of completed education at the time of the interview: (1) no high school degree, (2) lowest or middle track high school degree (‘Volks-/Hauptschule’ or ‘Realschule’), (3) lowest or middle track high school degree with job training/apprenticeship (‘Lehre’, ‘Berufsfachschule’, ‘Volontariat’, ‘Laufbahnprüfung’, or equivalent), (4) college preparatory (college track) high school degree (‘Fachhochschulreife’ or ‘Hochschulreife’) with or without training, and (5) college degree or higher (‘Fachhochschule’, ‘Universität’ or equivalent). The ranking is based on the level of general schooling (basic secondary=ISCED2A, upper secondary=ISCED3A, tertiary/college=ISCED5A/5B/6) differentiated by additional vocational or job training programs. The ISCED codes stand for the education attained according to the International Standard Classification of Education. A helpful summary chart of the German education system can be found on the web at http://www.ed.gov/pubs/GermanCaseStudy/chapter1a.html.

The Inglehart scale measures a person’s post-materialism by how he or she ranks two post-materialistic societal objectives (‘giving the people more say in important government decisions’ and ‘protecting freedom of speech’) relative to two materialistic objectives (‘maintaining the order of nation’ and ‘fighting inflation’). A strong priority for post-materialistic goals is expressed by individuals who select the two post-materialistic objectives first (‘PPM’). A strong materialistic view is expressed by ranking the two materialistic goals first (‘MMP’). Other combinations express different degrees of post-materialism that lie between these extremes.

Gisser et al. (1985, p. 51) find that upward revisions are more common than downward revisions among married Austrian women.

Gender roles are progressing only slowly in West Germany (e.g., Stöbel-Richter and Brähler 2005) and combining family and career is difficult for women here given these inflexible labor markets, traditional gender roles, and social policies that favor the male breadwinner and female homemaker arrangement (see Kreyenfeld 2002; Brewster and Rindfuss 2000; Chesnais 1996; Gauthier 1996).

Due to space limitations, we do not report the estimates for other age groups or men. We also note that the coefficients for some variables (regional dummies and post-materialistic views) included in the models are not reported here. The additional results are available upon request.

Given evidence of greater stability among those initially reporting two as desired, the preference data may be heteroskedastic as discussed above. To address this issue, we also calculated the robust standard errors for the FE estimates. The results did not change the inference presented here.

References

Adsera, A. (2005). Differences in desired and actual fertility: An economic analysis of the Spanish case, IZA Discussion Paper No. 1584: http://ftp.iza.org/dp1584.pdf.

Astone, N. M., Nathanson, C. A., Schoen, R., & Kim, Y. J. (1999). Family demography, social theory, and investment in social capital. Population and Development Review, 25, 1–31.

Becker, G. S. (1960). An economic analysis of fertility. In Demographic and Economic Change in Developed Countries. NBER Conference Series (Vol. 11, pp 209–231). Princeton, NJ: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Becker, G. S., & Lewis, H. G. (1973). On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 279–288.

Bender, D., Bien, W., & Bayer, H. (1996). Wandel und Entwicklung familialer Lebensformen: Datenstruktur des DJI-Familiensurvey. München (unpublished manuscript).

Blake, J. (1966). Ideal family size among White Americans: A quarter of a century’s evidence. Demography, 11, 25–44.

Benítez-Silva, H., & Dwyer, D. S. (2005). The rationality of retirement expectations and the role of new information. Review of Economics and Statistics, 87, 587–592.

Bongaarts, J. (1990). The measurement of wanted fertility. Population and Development Review, 16, 487–506.

Bongaarts, J. (2001). Fertility and reproductive preferences in post-transitional societies. In R. A. Bulatao, & J. B. Casterline (Eds.), Global fertility transition. New York, NY: Population Council.

Brewster, K. L., & Rindfuss, R. R. (2000). Fertility and women’s employment in industrialized nations. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 271–296.

Caldwell, J. C. (1982). Theory of fertility decline. London: Academic Press.

Calhoun, C., & de Beer, J. (1991). Birth expectations and fertility forecasts: The case of the Netherlands. In W. Lutz (Ed.), Future demographic trends in Europe and North America: What can we assume today? London: Academic Press.

Chesnais, J.-C. (1996). Fertility, family and social policy. Population and Development Review, 22, 729–739.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94(Supplement), S95–S120.

Coombs, L. C. (1974). The measurement of family size preferences and subsequent fertility. Demography, 11, 587–611.

Coombs, L. C. (1979). Reproductive goals and achieved fertility: A fifteen-year perspective. Demography, 16, 523–534.

DJI Familiensurvey (various years). Wandel und Entwicklung familialer Lebensformen, Welle, various. Deutsches Jugendinstitut, DJI. München.

Duncan, O. D., Freedman, R., Coble, J. M., & Slesinger, D. (1965). Marital fertility and family size of orientation. Demography, 2, 508–515.

Easterlin, R. A. (1978). The economics and sociology of fertility: A synthesis. In C. Tilly (Eds.), Historical Studies of Changing Fertility (pp. 57–133). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Engelhardt, H. (2004). Fertility intentions and preferences: Effects of structural and financial incentives and constraints in Austria, Vienna Institute of Demography Working Paper No. 02/2004: http://www.oeaw.ac.at/vid/download/WP2004_2.pdf.

EUROSTAT (2001). Europäische Sozialstatistik Bevölkerung. Luxembourg: European Communities.

Friedman, D., Hechter, M., & Kanazawa, S. (1994). A theory of the value of children. Demography, 31, 375–401.

Frejka, T., & Calot, G. (2001). Cohort reproductive patterns in low-fertility countries. Population and Development Review, 27, 103–132.

Freedman, R., Baumert, G., & Bolte, M. (1959). Expected family size and family size values in West Germany. Population Studies, 13, 136–150.

Freedman, R., Coombs, L. C., & Bumpass, L. (1965). Stability and change in expectations about family size: A longitudinal study. Demography, 2, 250–275.

Freedman, R., Freedman, D. S., & Thornton, A. D. (1980). Changes in fertility expectations and preferences between 1962 and 1977: Their relation to final parity. Demography, 17, 1–11.

Gauthier, A. H. (1996). The state and the family. A comparative analysis of family policies in industrialized countries. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gisser, R., Lutz, W., & Münz, R. (1985). Kinderwunsch und Kinderzahl. In R. Münz (Eds.), Leben mit Kindern. Wunsch und Wirklichkeit (pp. 33–94). Wien: Franz Deuticke.

Goldstein, J., Lutz, W., & Testa, M. R. (2003). The emergence of sub-replacement family size ideals in Europe. Population Research and Policy Review, 22, 479–496 (Special Issue on Very Low Fertility).

Gustavus, S. O., & Nam, C. B. (1970). The formation and stability of ideal family size among young people. Demography, 7, 43–51.

Hausman, J. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica, 46, 1251–1271.

Hagewen, K., & Morgan, P. S. (2005). Intended and ideal family size in the United States, 1970–2002. Population and Development Review, 31, 507–527.

Heiland, F. & Prskawetz, A. (2004). Female life cycle fertility, demand for higher education and desired family size in post-transitional societies: Theory and evidence from West Germany, Paper presented at the Economic Demography Workshop, Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, Boston, USA.

Heiland, F., Prskawetz, A. & Sanderson, W. C. (2005). Do the more-educated prefer smaller families? Vienna Institute of Demography Working Paper No. 03/2005: http://www.oeaw.ac.at/vid/download/WP2005_3.pdf.

Hendershot, G. E. (1969). Familial satisfaction, birth order, and fertility values. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 31, 27–33.

Hendershot, G. E., & Placek, P. J. (1981). Predicting fertility, demographic studies of birth expectations. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Hirsch, M. B., Seltzer, J. R., & Zelnik, M. (1981). Desired family size of young American women, 1971 and 1976. In G. E. Hendershot, & P. J. Placek (Eds.), Predicting Fertility (pp. 207–234). Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Hoffman, L. W., & Manis, J. D. (1979). The value of children in the United States. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41, 583–596.

Huestis, R. R., & Maxwell, A. (1932). Does family size run in families?. The Journal of Heredity, 21, 77–79.

Huinink, J. (1995). Warum noch Familie? Zur Attraktivität von Partnerschaft und Elternschaft in unserer Gesellschaft. Frankfurt/Main: Campus.

Huinink, J. (2001). The Macro-micro-link in demography – explanations of demographic change, Paper presented at the Conference “The second demographic transition in Europe”, 23–28 June 2001, Bad Herrenalb, Germany: http://www.demogr.mpg.de/Papers/workshops/010623 paper08.pdf.

Joyce, T., Kaestner, R., & Korenman, S. (2002). Retrospective assessments of pregnancy intentions. Demography, 39, 199–213.

Kantner, J. F., & Potter, R. G. Jr. (1954). The relationship of family size in two successive generations. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 32, 294–311.

Kohler, H.-P. (2001). Fertility and social interactions: An economic perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kohler, H. P., Rodgers, J. L., & Christensen, K. (1999). Is fertility behavior in our genes? Findings from a Danish twin study. Population and Development Review, 25, 253–288.

Kreyenfeld, M. (2001). Employment and fertility – East Germany in the 1990s. Dissertation, Rostock University.

Kreyenfeld, M. (2002). Time squeeze, partner effect or self-selection? An investigation into the positive effect of womens’ education on second birth risks in West Germany. Demographic Research, 7, 15–48.

Löhr, C. (1991). Kinderwunsch und Kinderzahl. In H. Bertram (Ed.), Die Familie in Westdeutschland, Stabilität und Wandel familialer Lebensformen Deutsches Jugendinstitut, Familien-Survey (Vol. 1, 461–496), Opladen: Leske Budrich.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Surkyn, J. 1988. Cultural dynamics and economic theories of fertility change. Population and Development Review, 14, 1–45.

Livi Bacci, M. (2001). Comment: Desired family size and the future course of fertility. Population and Development Review, 27, 282–289 (Supplement, “Global fertility transition”).

Long, J. F., & Wetrogan, S. I. (1981). The utility of birth expectations in population projections. In G. E. Hendershot, & P. J. Placek (Eds.), Predicting fertility (pp. 29–50). Lexington: Lexington Books.

Lutz, W. (1996). Future reproductive behavior in industrialized countries. In W. Lutz (Ed.), The future population of the world: What can we assume today? London: Earthscan Publications.

McAllister, P., Stokes, C. S., & Knapp, M. (1974). Size of family of orientation, birth order, and fertility values: A reexamination. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 36, 337–342.

McCallum, B. T. (1972). Relative asymptotic bias from errors of omission and measurement. Econometrica, 40, 757–758.

McCleland, G. H. (1983). Family size desires as measures of demand. In R. A. Bulatao, & R. Lee (Eds.), Determinants of fertility in developing countries (Vol. 1). New York: Academic Press.

Menniti, A. (2001). Fertility intentions and subsequent behavior: first results of a panel study, Paper presented at the European Population Conference, Helsinki, June 7–9.

Miller, W. B., & Pasta, D. J. (1995). How does childbearing affect fertility motivations and desires? Social Biology, 42, 185–198.

Miller, W. B., Pasta, D. J., MacMurray, J., Chiu, C., Wu, S., & Comings, D. E. (1999). Genetic influences on childbearing motivation and parental satisfaction: A theoretical framework and some empirical evidence. In L. Severy, & W. B. Miller (Eds.), Advances in population: Psychological perspectives (Vol. III). London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley.

Monnier, A. (1987). Projects de fécondité et fécondité effective. Une enquête longitudinal: 1974, 1976, 1979. Population, 6, 819–842.

Morgan, P. S. (1981). Intention and uncertainty at later stages of childbearing: the United States 1965 to 1970. Demography, 18, 267–285.

Morgan, P. S. (1982). Parity-specific fertility intentions and uncertainty: the United States, 1970 to 1976. Demography, 19, 215–334.

Morgan, P. S. (1985). Individual and couple intentions for more children: A research note. Demography, 22, 125–132.

Morgan, P. S., & Chen, R. (1992). Predicting childlessness for recent cohorts of American women. International Journal of Forecasting, 8, 477–493.

Noack, T., & Østby, L. (2002). Free to choose – but unable to stick to it? Norwegian fertility expectations and subsequent behaviour in the following 20 years. In M. Macura, G. Beets (Eds.), Dynamics of fertility and partnership in Europe: Insights and lessons from comparative research (Vol. 1). New York and Geneva, United Nations.

Philipov, D., Spéder, Z. & Billari, F. C. (2004). Fertility intentions in a time of massive societal transformation: theory and evidence from Bulgaria and Hungary, Paper presented at the 2004 Annual Meetings of the Population Association of America, Boston, March 31–April 3.

Preston, S. H. (1987). Changing values and falling birth rates. In K. Davis, M. S. Bernstam, & R. Ricardo-Campbell (Eds.), Below replacement fertility in industrialized societies: causes, consequences, policies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Quesnel-Vallée, A. & Morgan, S. P. (2003). Missing the target? Correspondence of fertility intentions and behavior in the U.S.Population Research and Policy Review, 22, 497–525 (Special Issue on Very Low Fertility).

Rindfuss, R. R., Morgan, S. P., & Swicegood, G. (1988). First births in America: changes in the timing of parenthood. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Ryder, N. B., & Westoff, C. F. (1969). Relationships among intended, expected, desired and ideal family size: United States, 1965. Washington: U.S. Center for Population Research.

Schoen, R., Astone, N. M., Kim, J. Y., Nathanson, C. A., & Fields, J. M. (1999). Do fertility intentions affect fertility behavior? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 790–799.

Schoen, R., Kim, Y. J., Nathanson, C. A., Fields, J., & Astone, N. M. (1997). Why do Americans want children? Population and Development Review, 23, 333–358.

Stöbel-Richter, Y., & Brähler, E. (2005). Einstellungen zur Vereinbarkeit von Familie und weiblicher Berufstätigkeit und Schwangerschaftsabbruch in den neuen und alten Bundesländern. Zeitschrift für Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde, 65, 256–265.

Stolzenberg, R. M., & Waite, L. J. (1977). Age, fertility expectations and plans for employment. American Sociological Review, 42, 769–783.

Symeonidou, H. (2000). Expected and actual family size in Greece. European Journal of Population, 16, 335–352.

Testa, M. R. & Grilli, L., 2006, The influence of childbearing regional contexts on ideal family size in Europe. Population, 61, 99–127 (English Edition).

Thomson, E. (1997). Couple childbearing desires, intentions, and births. Demography, 34, 343–354.

Thomson, E., McDonald, E., & Bumpass, L. L. (1990). Fertility desires and fertility: Hers, his, and theirs. Demography, 27, 579–588.

Thornton, A. D., Freedman, R., & Freedman, D. S. (1984). Further reflections on changes in fertility expectations and preferences. Demography, 21, 423–429.

Toulemon, L. (1996). Very few couples remain voluntarily childless. Population, 8, 1–27 (English Edition).