Abstract

Despite a delay of 20–25 years, when it comes to cohabitation, Italy has now begun to resemble other Western countries. In addition, the increase in legal separations has accelerated since 1995, although their number still remains far from that observed in countries such as the USA, the UK, and France. Finally, Italy’s fertility decline has come to a halt: the cohort of women born in the early 1970s will likely have the same TFR as those born in the mid-1960s (around 1.55). Moreover, in the Centre–North areas, period TFR rose from 1.1 in 1995 to 1.35 children per woman 10 years later. The territorial diffusion of cohabitation, legal separation, out-of-wedlock births, and fertility recovery overlaps closely with that of the decline in births during the first half of the twentieth century. A similar geographical pattern has been observed for the diffusion of school enrolment, industrialization, secularization, and (during the last 20 years) foreign immigration.

Résumé

Malgré un retard de 20 à 25 ans, en matière de cohabitation l’Italie commence à présent à ressembler aux autres pays occidentaux. De plus, la hausse des séparations légales s’est accélérée depuis 1995, bien que leur niveau demeure encore bien en-deçà de celui qui est observé dans des pays tels que les Etats-Unis d’Amérique, le Royaume-Uni, et la France. Finalement, la fécondité a cessé de baisser en Italie: la cohorte des femmes nées au début des années 1970 aura selon toute vraisemblance le même indice synthétique de fécondité que celle des femmes nées au milieu des années 60 (environ 1,55). De plus, dans les régions du centre-nord, l’indice synthétique de fécondité est passé de 1,1 enfant par femme en 1995 à 1,35 dix ans plus tard. La diffusion territoriale de la cohabitation, des séparations légales, des naissances hors mariage et du rattrapage de la fécondité recouvre de façon étroite celle de la baisse des naissances au cours de la première moitié du vingtième siècle. Le même schéma géographique est observé dans la diffusion de la scolarisation, de l’industrialisation, de la sécularisation et (pendant les 20 dernières années) de l’immigration en provenance de l’étranger.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the early 1980s, several signs of new marital and reproductive behaviors began to appear in Italy (Istat 1986). In the fifteen years that followed, however, the Italian family changed in some rather unexpected ways (Castiglioni and Dalla Zuanna 1994). Although age at first marriage increased rapidly, other behaviors which would have questioned the centrality of marriage remained rare. Indeed, cohabitation and out-of-wedlock births did not increase and marital separation was still uncommon. Fertility, on the other hand, decreased to levels much lower than those ever experienced by northern European or overseas English speaking countries. During the 1990s, Italy—especially in the north–central regions—became the “title-holder” of the so-called “lowest-low” fertility (Kohler et al. 2002) and “latest-late” departure from the parental home (Billari et al. 2001; Billari 2004). Italy shared these behavioral changes with other southern European countries (mainly Spain and Greece) and the rich nations of East Asia (Caldwell and Schindlmayr 2003).

In this article, we discuss whether these Italian “anomalies” have become less prominent over the last decade (since 1995) and hence whether Italy is beginning to assimilate marital and reproductive models already quite widespread in most other developed countries. In order to do this, we have analysed the results from several recent studies and developed original analyses using data from a variety of sources.

In the sections that follow, we discuss each of the following issues: the living arrangements of young people (Sect. 2), legal separations (Sect. 3), and fertility (Sect. 4). Our approach is primarily descriptive in nature although in order to formulate hypotheses with regard to future developments, we also present some interpretive elements garnered from a review of previous literature and a territorial analysis. Observation of the substantial regional differences in Italy—particularly between the rich areas of the Centre–North and the less economically developed southern regions—provides a useful means of identifying the direction of future family change (Fig. 1).

2 The Living Arrangements of Young People

2.1 The Delay of Marriage and Postponed Departure from the Parental Home

The cohorts born in the mid-1950s have the lowest average age at marriage in Italy (Castiglioni and Dalla Zuanna 1994; Righi 1997; Barbagli et al. 2003, Chap. 2). Half of the women were married before their 24th birthday while half of the men wed before they turned 27. The cohorts that followed, however, began to postpone marriage, especially in the northern and central regions (Table 1). We do not yet know to what extent this delay in marriage will evolve toward a decline in the proportion of married people. Nonetheless, it would be difficult for the cohorts born after 1960 to match the low proportion of never-married individuals among those born in 1954. In this cohort, only 9% of women and 11% of men had never married by age 50 (see the National Register Data at demo.istat.it). These are the lowest values for all those born in the twentieth century.

The ensuing “flight” from marriage can only be understood within the context of an increasingly long period of time spent before entry into adulthood. For example, in Italy the average age at first marriage for men dramatically parallels the average age of the ordination of priests, rising from 27 years of age in 1976 to 31 years of age in 2001 (Diotallevi 2005, p. 210).

Table 2 shows that the proportion of individuals aged 25–34 living in the parental home also increases from one cohort to the next, reaching 44% for those born between 1969 and 1978 (Ongaro 2006). This value is strikingly different from that observed in north–western Europe and in the overseas English speaking countries where by the age of 25 the majority of youth have already left the parental home (Sgritta 1999; Corijn and Klijzing 2001; Iacovu 2002; Billari 2004; Guizzardi 2007). On the other hand, since the mid-1990s, the proportion of young people living with their parents has risen across Europe (EurLife 2005).

2.2 The Rapid Increase in Cohabitation and Out-of-Wedlock Births After 1995

Recently available data show that the persistent delay in the departure from the parental home has not prevented the diffusion of unmarried cohabitation in Italy for the cohorts born after the mid-1960s (Rosina and Fraboni 2004; Istat 2005, Chap. 4). The proportion of women with at least one experience of cohabitation has increased (Fig. 2). In addition, the number of marriages preceded by cohabitation has rapidly risen in recent years (Fig. 3). This is particularly true in the Centre–North regions. At a national level, only 6% of first weddings celebrated in the 1980s and 12% of those celebrated in the 1990s were preceded by cohabitation, compared to 22% of those celebrated in the 5-year period from 1999 to 2003. The diffusion of births outside of marriage follows a similar trend, with a considerable acceleration in the Centre–North after 1994 (Fig. 4).

2.3 Interpreting Past Delays and the Contemporary Acceleration of Change

Numerous researchers have attempted to explain the motives behind Italian delayed entry into adulthood, yet several questions remain unanswered. Why do young Italians leave the parental home at a later age with respect to young people in central and northern Europe? And why have new marital and reproductive behaviors spread so much later?

One possible interpretive framework for explaining delayed departure from the parental home concerns restraint factors. Young Italians may be forced to remain at home due to a series of material constraints such as elevated levels of unemployment, scarcity of available housing at reasonable renting rates, prolonged university studies beyond the expected number of years, and a lack of policies to support departure from the parental home at a young age (Livi Bacci 2001; Kohler et al., 2002).

Several counterarguments, however, contradict this apparently neat linear explanation. Youth unemployment, for example, has been essentially absent in most of the provinces in the Centre and the North of Italy. Yet this is exactly where a rapid increase has occurred in the proportion of individuals over the age of 30 who still lived with their parents.

The following “natural experiment” reveals interesting information with regard to the material welfare of youth and their behavior. In 1996, researchers studied the living arrangements of second-generation immigrants in Australia (Table 3). In terms of the labor market, housing, and welfare, children of Italians and Greeks were similar to native children and to children of immigrants from northern Europe and New Zealand. However, the children of Greeks and Italians differed sharply from Australian children or other immigrants of the same age, in that they had rarely lived alone or with friends, or cohabited (a similar description was applicable to the young people who came from other southern European countries, as well as Lebanon and China—the latter when they immigrated with the entire family). These empirical results suggest that young Italians are not “forced” to stay in the parental home.

Although it cannot be said that material constraints are the primary explanatory factor for Italy’s unique situation, during recent years their weight might have increased. As mentioned above, the proportion of young people living in the parental home increased from 1998 to 2003 (Table 2). In addition, in both 1998 and 2003, young people living in the parental home were asked about the reasons for their living arrangements (Istat 2005, p. 247). The two items related to “constraints” were “Because I do not have a permanent job” and “I cannot afford to rent or buy a house.” While the proportion of youth who had employment difficulties did not change from 1998 to 2003 (indicated by 17% of never-married individuals aged 20–34 living in the parental home), housing related constraints increased from 18 to 24% for the same group. At the same time, the percentage of people who gave “positive” motives have declined: in 1998, 50% answered “I’m fine with how things are; at any rate, I maintain my sense of freedom,” but 5 years later this proportion dropped to 43%. More generally, understanding the considerable constraints faced by young people with regard to the housing market (difficulty obtaining a mortgage and affording high rental rates) may be helpful in explaining behavioral change (Mulder 2006).

A second possible explanation in answer to the questions posed at the beginning of this section concerns the strong ties that exist between parents and children in Italy. Indeed, it has become evident that the existence of a homogenous “bourgeois family” across the developed world is not necessarily a reality. Certainly in the past, significant differences in family relationships could be found between north–western European and overseas English speaking countries, and southern European and eastern Asian countries. With regard to the former two, intergenerational relationships traditionally weakened as an individual entered adolescence, while in the latter two, these relationships remained strong throughout life. Deeply rooted historical patterns of family relationships (Reher 1998) do not so much result in a dissimilar love between parents and children, as they do in different practical manifestations (Bonifazi et al. 1999; Palomba and Schinaia 1999; Dalla Zuanna 2004; Mazzuco 2006).

In societies where intergenerational relationships are strong, innovative behavior among the younger generations can spread only if it is not obstructed by their parents (Rosina 2001). Parents are extremely influential and powerful in their ability to conduct their children toward marital behaviors which are in line with their expectations. Not only do they use moral pressure (enhanced by a significant portion of life spent together), but parents can also adopt more concrete tools of persuasion, such as substantial monetary help for the construction or purchase of a home. Indeed, more than 50% of couples in Italy who married in the 1990s received this sort of aid from their parents (Barbagli et al. 2003). In order to become widespread, the practice of cohabitation had to wait for a generation of parents who were willing to accept it—or those who grew up during the “cultural revolution” in Italy during the 1970s. Footnote 1

Data supporting this interpretive theory seem convincing. By 1983, a significant proportion of young Italians considered cohabitation to be admissible and did not exclude the idea of doing so themselves (Table 4). However, among these young people, there was a widely held perception that society was hostile toward this choice, and only a limited number actually cohabited. The same questions were asked again every 4–5 years. Over time, the number of youth who considered cohabitation to be admissible and did not exclude the possibility of doing so themselves grew only slightly, while the perception of societal acceptance towards this choice changed precisely for those born during the 1970s and 1980s, i.e., for the children of parents who were young just before or during the “cultural revolution” of the 1970s.

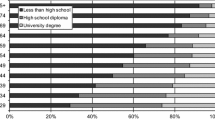

The notion that cohabitation in Italy spread only with the acquiescence of parents (and a generation later than in northern European countries) has also been suggested by more sophisticated analyses. Rosina and Fraboni (2004), Schroder (2006), Di Giulio and Rosina (2007) demonstrated that in order to “explain”—with statistical models—the probability of cohabiting, it was more useful to examine certain characteristics of the parents, rather than those of the children. Ceteris paribus, the probability of individuals cohabiting or having cohabited was higher if their parents held a high school or university degree than if they themselves held a high school or university degree.

A third and final explicative framework concerns the connection between new marital behaviors and the process of secularization (Lesthaeghe 1995). In Italy, this development has taken place more slowly than in the other Western countries due to the overwhelming presence of the Catholic Church and its influence on family matters (Ginsborg 1989; Dalla Zuanna et al. 2005; Caltabiano et al. 2005). For example, 3.02% of young Italian Catholic men baptized between 1971 and 1975 were enrolled in seminaries to become priests by 1996. This same indicator was only 0.99 in France, 1.10 in Belgium, 0.94 in the Netherlands, 2.28 in Germany, 1.89 in Spain, and 2.21 in Ireland (Dalla Zuanna and Ronzoni 2003, p. 23). The secularization process has accelerated since the mid-1990s, as shown by the downward trend of several other indicators (i.e., proportion of people attending Mass every week; proportion of individuals baptized who then received Confirmation; proportion of volunteers belonging to Catholic organizations, Coppi 2005). On the other hand, there are several other important indicators which do not show a clear decline after 1995: the proportion of people who choose to devolve 8% of their taxes to the Catholic Church (rather than to the state or other religions) and the proportion just mentioned, of men studying to become priests (Dalla Zuanna and Ronzoni 2003; Chiesa in Italia, Annali 2002–06; Coppi 2005).

If secularization continues to spread, it will most likely favor the diffusion of new marital behaviors. In Sect. 3, we provide evidence of a strong ecological correlation between, on the one hand, premarital cohabitation, out-of-wedlock births, and legal separations, and on the other hand, votes in favor of divorce in the 1974 referendum (a very relevant indicator of secularization in Italy, Livi Bacci 1977). Other authors have obtained similar ecological results using more sophisticated methodologies (Dalla Zuanna and Righi 1999; Billari and Borgoni 2002a, b). More specifically, a number of studies have demonstrated that those individuals more involved in the Catholic Church have a lower probability of cohabiting and separating. They also have a lower probability of using modern contraception and of having sexual intercourse at a young age (De Sandre and Dalla Zuanna 1999; De Rose and Rosina 1999; Dalla Zuanna et al. 2005; Castiglioni 2004; Caltabiano et al. 2005; Di Giulio and Rosina 2007).

3 The Increase of Legal Separations

3.1 Rapid Change, But Still in its First Phase

In the last 15 years, legal separations in Italy have almost doubled (Table 5). Footnote 2 In 2004, one legal separation was recorded for every three marriages; 15 years earlier, this ratio was one in every eight marriages. In order to study this diffusion process in an analytical manner, we have built life-tables by separation, for the marriage cohorts who celebrated their weddings in Italy from 1969 to 1998 (Castiglioni and Dalla Zuanna 2007). For the earliest cohorts, the tables refer to the first 25 years of marriage; for the following cohorts, some of the probabilities of separation (for the various durations up until the 25th year of marriage) are projected (Table 6).Footnote 3

The occurrence of legal separations steadily increases cohort after cohort and then accelerates after 1995 for each 5-year marriage cohort, regardless of the duration (see the gray-colored figures in Table 6). If our projections are correct, the proportion of marriages legally separated before their 20th anniversary will rise from 8% (1974–78) to 25% (1994–98). This result seems to be realistic, because the last available period life-table (for 2003) shows that 20% of marriages are dissolved by a legal separation before their 20th anniversary, and 24% at the duration 30 (Castiglioni and Dalla Zuanna 2007).

The increase in marital separations in Italy may still be in its first phase. Our projections suggest that 19% of weddings celebrated in the early 1990s will end in a legal separation before their 20th anniversary. Yet this proportion had already been reached or surpassed for marriages celebrated in the early 1940s in the USA, in the 1960s in the UK, and in the 1970s in France. Furthermore, during these respective time periods, the distribution by duration of marriage for these countries was very similar to the distribution by duration for marriages celebrated in Italy in the early 1990s (Castiglioni and Dalla Zuanna 2007). As marital separations have become ever more frequent in the USA, UK, and France, they have also increasingly occurred during the 5 to 9 year duration. Only future observations will tell us whether Italian marriages will follow a similar trend.

3.2 Describing and Explaning Enormous Territorial Differences

A territorial analysis is particularly useful for understanding the factors behind the diffusion of legal separations in Italy. More specifically, the relatively low level of marital separations in Italy conceals large geographical differences (Figs. 5, 6, see also Salvini 2005; Ferro and Salvini 2006). Separations most commonly occur in the north–western regions (Piemonte, Val d’Aosta and Liguria), in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, and in the two predominantly “red” regions (Toscana and Emilia-Romagna). In the latter two regions, the Communist Party (since WWII) has consistently received the majority of votes, and the process of secularization was relatively rapid. The region of Lazio, where half of the inhabitants live in the urban area of Rome, also has a higher percentage of legal separations. The lowest levels are in the South, with the exception of Sardegna (Sardinia).

Legal separations in different areas of Italy. Proportion of marriages celebrated in 1973–1998, dissolved before the twentieth anniversary. Source: Castiglioni and Dalla Zuanna (2007)

Estimate of the proportion of marriages celebrated in 1998 ending in legal separation before their twentieth anniversary (%), by region. Source: Castiglioni and Dalla Zuanna (2007)

Our estimates suggest that only 15% of marriages celebrated in the South in 1998 will end in legal separation before their 20th anniversary. This is the same level recorded for the north–western regions 20-years earlier. The other regions have medium levels of legal separations. The region of Veneto, in the north–east, provides an interesting case, in that the proportion of legal separations is quite low, likely due to the considerable influence of the Catholic Church during the twentieth century.

Generally speaking, a geographical perspective reveals that the diffusion of legal separations overlaps with a pattern of “modernization,” even when the relatively backward regions of South are excluded from the analysis in order to avoid polarization (Table 7). In fact, the diffusion of legal separations follows the same geographical gradients of literacy, the historical spread of birth control, wealth, secularization, and female participation in the labor force. In addition to these elements, Table 7 also illustrates the consistency between the territorial diffusion of legal separations, and out-of-wedlock births.

The strength of modernization in influencing the diffusion of marital disruption in Italy is also confirmed by more sophisticated analyses which use both ecological (Rivellini et al. 2005, 2006) and individual data (De Rose 1992; De Rose and Rosina 1999; De Rose and Di Cesare 2003; Ferro et al. 2006; Impicciatore and Billari 2007). Results from the former are robust enough to suggest that the spread of legal separations in Italy recounts a familiar tale. More specifically, the pattern of diffusion of “new” marital and reproductive behaviors overlaps with that of the modernization process over the last century (Livi Bacci 1977; Dalla Zuanna and Righi 1999). Despite recent changes (i.e., the rapid secularization of Veneto and Sardegna in the last few years), territorial continuity clearly prevails. Consequently, we believe that the process of territorial diffusion of legal separations will continue, such that the regions of the South will eventually follow in the footsteps of the forerunner regions in the North–West.

4 Fertility

4.1 Intensity and Age Patterns Among Cohorts: From Change to Stabilization

Fertility decline among Italian women persisted up to the cohorts born in the mid-1960s (Santini 1988, 1995, 1997; Istat, 1997; Caltabiano 2006). Beginning with the cohort of 1955, mean age at first birth gradually began to increase (Table 8). Although the TFR of the cohort born in 1965 is rather low (around 1.55), it is still much higher than the period TFR recorded when these women were about 30 years of age (1.22). Such measurements demonstrate that the recovery of fertility in Italy after age 30 is not negligible (Sobotka 2004).

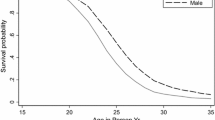

Although the more recent cohorts have not yet finished their reproductive lives, censored data show that cohort fertility decline seems to have come to a halt (Fig. 7). The cohort of women born in 1970 had few children before their 30th birthday, but with respect to those born in 1965, they had more children in the age-class 30–34. In all probability, they will also have more children after the age of 35. In addition, the cohorts born in 1975, 1980, and 1985 resemble one another quite closely in terms of fertility during the first part of their reproductive lives.

Fertility by age and cohort for women born in 1960–85. Italy, North–Centre and South. Source: Caltabiano (2006)

Territorial data reinforce the notion of a gradual stabilization with regard to cohort fertility. In the Centre–North regions, the recovery of fertility after age 30 by the 1970 cohort is more intense than the national average. In addition, the stabilization of fertility in the first phase of a woman’s reproductive life is a relatively consolidated phenomenon, in that it reflects the behavior of all the cohorts born after 1970. The pattern observed for the cohorts from the South is similar to that seen in the Centre–North, but with a delay of about 10 years. In particular, the age-specific fertility of the 1970 cohort from the South almost perfectly matches the level and age pattern of the 1960 cohort in the Centre–North. The same emerges when observing the cohorts born in the following 10-years. Consistent with this interpretive reading of a southern “lag,” we do not observe an end to fertility decline in the South until the cohort of 1980.

4.2 Period Fertility: From Decline to Recovery

In addition to considerations of fertility by cohorts, it is also interesting to briefly analyze changing period fertility, both at the national and territorial levels. After having reached a minimum value of 515,000 in 1998, the number of births in Italy began to increase, surpassing 550,000 in 2004, 2005, and 2006. The actual number of women aged 20–39 during this same time period decreased as the numerous women born during the baby boom (1955–70) slowly began to be “replaced” by the smaller cohorts of women born after 1980. The rapid decrease in the number of Italian women of childbearing age reached its lowest point in the first decade of the new century. More specifically, at the beginning of 2004, women resident in Italy aged 15–19 numbered 1,400,000, while those aged 40–44 numbered 2,200,000. Since 1998, a declining number of women have had a growing number of births, such that the TFR surpassed 1.3 children per woman in 2004, 2005, and 2006. This is 15–16% higher than the minimum reached in 1998 (Table 9).

As already observed in the cohort analysis above, national-level data reflect the sum of quite diverse territorial fertility histories (see Sect. 4.1). The differences among regions at the turn of the century, however, are not as striking as those seen in the early 1980s (the variation coefficient of the TFR among the 20 Italian regions drops from 0.24 in 1983–85 to 0.09 in 2003–05). In other words, an “upset” in the traditional geographical distribution of Italian fertility has occurred (Fig. 8a, b).

Geographical perspective of fertility indicators by region in Italy. (a) Mean number of children per woman, 1983–85 (National average: 1.33); (b) Mean number of children per woman, 2003–05 (National average: 1.33); (c) Proportion of births to foreigners, 2004 (National average: 9%); (d) Proportion of out-of-wedlock births, 2004 (National average: 15%). The twenty Italian regions are ranked into three groups (of six, seven, and six units)

Descriptions of period fertility can easily be reconsidered from a cohort perspective. Very low fertility during the period of 1980–95 was caused by a combination of “missing children” from two cohorts in two different age groups. Women born in the 1940s and 1950s make up the first group; they married on average at 23–24 years of age, they had most of their children before age 30, and had very few children at older ages. The second group is composed of those women born in the 1960s and 1970s who had very few children at young ages. The upturn of fertility rates in the Centre–North of Italy after 1995 is due both to the stabilization in fertility rates at younger ages for the cohorts born in the 1970s, and to the rising fertility rates at older ages for the cohorts born in the 1960s.

4.3 Interpreting the Increase in Period Fertility in the Centre–North Regions

The upturn of fertility in the regions of the Centre–North is one of the most important demographic changes to have occurred in Italy in recent years. It seems appropriate to reflect on several possible explanations, in an effort to surmise what might occur in the near future. This reflection also gives us the opportunity to reconsider several interpretive frameworks put forth for lowest-low Italian fertility over the last 20-years.

Although not mutually exclusive, we employ the following four hypotheses in order to interpret rising fertility in the Centre–North after 1995:

-

(1)

Postponement effect. The general upturn of fertility levels after 1998 may be due to the combined result of an absence of fertility decline among the younger age groups, and an increase in birth rates among the older age groups.

-

(2)

Fertility of foreigners. The striking increase in the foreign population living in Italy in the last 20 years is an absolutely new phenomenon. In 1986, the number of foreigners living in Italy was counted in the tens of thousands; by mid-2006, their number had increased to three and a half million. This group largely comprise young adults and children. If the fertility of foreigners has been higher than that of Italians, then the recent escalation of immigration may push up fertility rates.

-

(3)

New marital behaviors. Fertility may be higher in those areas in which behaviors, such as cohabitation, out-of-wedlock births, and separations are more widespread. This would follow the pattern already observed in many other European countries.

-

(4)

A more favorable context for procreation. Lowest-low fertility may be the result of a series of constraints, especially lack of money and time for children. If these factors become less of a hindrance, fertility may increase.

As we have already discussed the first hypothesis in detail (Sects. 4.1 and 4.2), in the following sections, we further explore the other three explanations.

4.3.1 Foreign Fertility Contribution

Between 1996–2006, the number of children born to foreign parents rose from 11,000 to 55,000 (Table 10). The increase in the total number of births during this decade is thus due to births to foreigners, as the number of Italian births remained more or less constant. If we consider fertility rates, however, then the picture slightly changes. Fertility for Italian women has risen as their numbers have decreased. From 1996 to 2006 the number of Italian women aged 18–49, resident in Italy, fell from 13,300,000 to 12,100,000. Half of these “missing women” were “replaced” by new foreign female citizens, who during the same time period increased in number from 250,000 to 885,000. Foreigners tend to have higher fertility rates than native Italians, meaning that they generally push up overall fertility levels. On the other hand, the proportion of foreign women living in Italy remains relatively low—less than a tenth of the total of women of reproductive age in 2006. In addition, when suitable fertility measures are used, the contribution of foreigners to the increase in period fertility does not appear to be overwhelmingly large (see Appendix). In 1996, the general fertility rate was 39.1 for Italian women, 43.1 for foreign women and 39.1 for the total population (Table 10). The increase from 1996 to 2006 was 6% (Italians), 44% (foreigners), and 10% (total population). Consequently, the contribution of foreigners to the increase of general fertility in Italy was (10−6)/10 × 100 = 40%. Moreover, because the mean age at birth of foreign women is relatively low, their contribution to halting fertility decline before age 30 (for the cohorts born during the 1970s) may be quite significant (Sect. 4.1). However, the lack of detailed fertility data by age and citizenship prevents further analysis.

These considerations, however, do not exclude the possibility that in some areas the influence of foreign fertility may hold greater significance. More specifically, in the time frame under consideration, almost all of the births to foreign women took place in the Centre–North. Not only were there far fewer women immigrants in the South, but they also tended to have rather low fertility rates, due to the fact that few of them had settled down in one place (Table 10; Fig. 8(c). Moreover, in some areas, the proportion of foreigners is particularly high; studies in several Italian cities show the growing importance of foreign births for the replacement of the population (i.e., for Florence: see Magherini and Mencarini 2001; Regina et al. 2003; Ferro 2005; for Verona: Bressan et al. 2005; for Milan: Comune di Milano 2005).

4.3.2 New Marital Behaviors and Fertility

Dalla Zuanna and Righi (1999, pp. 30–31) constructed an indicator for the diffusion of new marital and reproductive behaviors for eighteen western European countries. They compared this indicator with fertility levels at the beginning of the 1990s and found a linear correlation of 0.93: the more widespread the new behaviors, the higher the fertility levels. This territorial regularity may also be present within Italy. In some areas, higher fertility coexists with more widespread cohabitation and births out of wedlock (Fig. 8, compare b and d). At a micro-level, Billari and Rosina (2004) have shown that for the period preceding 1997, couples in cohabiting unions had on average lower fertility with respect to first unions by marriage. On the other hand, they noted that beginning cohabitation early enough compensated for this difference. To our knowledge, there is a gap in the micro-analysis literature for the period that follows (i.e., when out-of-wedlock fertility rapidly increases).

In the absence of nationally representative studies, we make use of an investigation conducted in the late 1990s on Milan in order to further explore this issue (De Sandre and Ongaro 2003). Milan is both the most populated city in northern Italy (with 1,300,000 inhabitants at the end of 2004) and the most economically dynamic. By the 1990s, new marital behaviors were already quite widespread. More than 40% of first marriages of women born in 1965–1974 were preceded by cohabitation, compared to less than 20% of women born in the 1950s. Moreover, during the period 1995–99, 52% of first unions were cohabitations. However, the increase in cohabitations throughout the 1990s was not accompanied by a similar rise in out-of-wedlock births, but rather accelerated the shift to marriage and to legitimate births. This rapid move toward marriage was facilitated by a younger age (of about a year) for first cohabitating unions, compared to first unions by marriage. By 2004, fertility levels were at an average of 1.46 children per woman, or 70% higher than the fertility rate in the mid-1980s, and fertility had increased for all ages.

It is difficult to tell whether Milan of the mid-1990s, as described above, was a true forerunner of what is now occurring in all of central and northern Italy. These behavioral observations do, however, allow us to argue that in Italy—as elsewhere—relatively high fertility can coexist, and indeed may be favored by, very different marital choices than those made in the past.

4.3.3 A More Favorable Context for Procreation?

Today, developed countries characterized by higher levels of fertility are those where a large proportion of women participate in the labor force and where couples with children are able to take advantage of public and/or private systems that allow them to balance domestic and paid labor (Cantisani and Dalla Zuanna 1999; Billari and Kohler 2004). In these countries, fathers also tend to contribute significantly to household chores and childcare (McDonald 2000). Finding equilibrium between childcare and paid labor has been more difficult for women in Italy than elsewhere (Pinnelli 1995; Bettio and Villa 1998; Rampichini and Salvini 2001; Ongaro 2002; Ongaro and Salvini 2003; Piazza 2003; Salvini 2004). In the context of Italy’s contemporary social system, there exists what one might call the “trap” of having an additional child. Women who continue to work outside the home earn sufficient income to raise their children but often do not have enough time to spend with them as a consequence of unsatisfactory family policies, and at best inadequate market for private childcare, and low levels of paternal participation in domestic and childcare activities (Saraceno 1994; Livi Bacci 2004; Istat 2005, part 4.3; Mencarini 2007). Those women, on the other hand, who decide to leave the labor force after the birth of a child, have more time to spend with their children, but not enough financial means to support them. When forced to confront this catch-22 predicament, many couples decide, against their wishes, to abandon any plans for a second, third, or fourth child. Nevertheless, in the last decade, even in Italy, couples who were less constrained by these issues have had an additional child.

More specifically, there are several factors which seem to characterize a more favorable context for fertility in Italy. First, fertility rates have risen mainly in the richest and most economically dynamic provinces (i.e., where a larger proportion of women participate in the labor force). Footnote 4 Secondly, since the late 1990s, several national and local administrative measures—economically favorable to families with children—have been approved. While certainly not comparable to the more extensive policies already adopted in other European countries, recent national political programs have had a statistically significant impact on the propensity of couples to have a third child in poor families Footnote 5 (Billari et al. 2005). These policies, however, have had very little impact on the absolute number of births.

Finally, in families in which both partners work and the father does not leave the running of the household and childcare to the mother alone, the probability of having a second or third child is significantly higher (Mencarini and Tanturri 2004; Mencarini 2007). Recently, the proportion of partners sharing housework and childcare has increased, such that this constraint may eventually become less of a barrier to fertility.

4.3.4 A Joint Analysis of the Four Effects on Fertility

To conclude, we want to determine if each of the four effects has an independent influence on fertility. We used a procedure previously employed in other territorial studies of Italian fertility (see for example, Livi Bacci 1977; Dalla Zuanna and Righi 1999). We applied a multiple linear regression model, using as statistical units the 63 Italian provinces of the Centre–North. We excluded, however, the provinces of Lazio where fertility continued to decline into the late twentieth century, although we did include the province of Rome where the fertility levels have increased. The dependent variable is the upturn of fertility between 1986–1995 and 1996–2000. We calculated four indicators (described under Table 11) for each of the respective explicative hypotheses discussed up to this point. Before being inserted into the model, the four indicators were standardized (mean 0 and variance 1) in order to make the beta regression coefficients comparable.

The four indicators are all statistically associated with the increase in fertility at the end of the century and agree with the hypotheses suggested above. All four maintain a significant association, even when they are put in “competition” with one another, and the fit is good R 2 corrected = 0.57.

5 Conclusion

Since the close of the twentieth century, the gap between Italy and central and northern European countries with regard to marital and reproductive behaviors has consistently narrowed. Cohabitation and legal separation are increasingly frequent, a growing number of children are born out-of-wedlock, cohort fertility seems to have stabilized at around 1.55 children per woman, and fertility is increasingly concentrated in the period following the woman’s 30th birthday. These changes, however, do not signify that other distinctive Italian characteristics have disappeared. In fact, even in the regions where many couples cohabit, the very late age at leaving the parental home has meant that cohabitation is practiced more by young adults (25–34 and older) than by youth (15–24 years of age). Over the next few years the general diffusion of cohabitation and out-of-wedlock births in Italy will likely continue to be accompanied by a prolonged stay in the parental home.

With specific regard to cohabitation, Italy—despite a delay of 20–25 years—has begun to resemble other European countries. This postponement was probably caused by the attitudes and behaviors of generations of parents born before the Second World War, who refused to accept such new behavior on the part of their children. In Italy, very strong intergenerational ties render a young son’s or daughter’s decision to cohabit extremely difficult without the (implicit and explicit) agreement of their parents.

The number of legal separations has also rapidly increased, although Italy’s current mean national level remains far lower than rates observed in countries such as the USA, the UK, and France. Moreover, the Italian pattern of legal separation by marriage duration (the probabilities are constant between the 5th and the 25th anniversary) is closer to that observed in these three countries when separations in the former were at the same level as present-day Italy.

Italy’s very low fertility rates have also begun to change. The upturn in fertility has taken place primarily in the Centre–North areas, where the TFR went from 1.1 children per woman in 1995 to 1.35 ten years later. In the South, on the other hand, fertility decline has not yet come to a halt, although its pace seems to have slowed. Moreover, for the cohorts of women born after 1970 (in the Centre–North) and after 1980 (in the South), fertility before the age of 30 is no longer in decline. The upturn in fertility since 1995 has been particularly strong in the more economically dynamic areas located in the Centre–North, where a greater proportion of the population is made up of foreigners, where new marital behaviors have spread more rapidly, and where, in previous years, fertility declined to extremely low levels. The “message” conveyed by these results is that lowest-low fertility is not Italy’s “destiny.” On the other hand, if Italy is to reach the current fertility levels of France and Northern European countries (1.8 children per woman or more for the cohorts born in the 1960s) two considerable hurdles concerning the reconciliation of female participation in the labor force and child-care must be overcome: (1) the scarcity of fiscal policies, allowances, and cheap public and private services for families with children; (2) the low levels of fathers’ participation in family care (Esping-Andersen 2007).

The study of Italian territorial differences in marital and reproductive behavior aids in understanding their determinants. A geographical perspective of the diffusion of legal separation, cohabitation, and out-of-wedlock births reveals a close overlap with the major decline in births during the first half of the twentieth century. During this period, a similar pattern of territorial differences emerged with the spread of school enrolment, industrialization, and (above all) secularization. Despite some locally specific exceptions and the slight decrease in interregional differences over the last decade, territorial continuities over time (such as the dramatic contrast between the Centre–North and South) remain a predominant characteristic of Italian marital and reproductive behavior.

Notes

Several important dates with regard to the “cultural revolution” in Italy during the 1970s should be mentioned: 1970, divorce became legal; 1971, contraceptive advertising was legalized; 1974, confirmative referendum in favor of divorce; 1975, new family law equalized the rights of children born out-of-wedlock and those born within marriage; 1978, abortion was legalized; 1981, confirmative referendum in favor of abortion.

In Italy, divorce was made legal in 1970 and entails two stages: a period of legal separation followed by divorce. The Divorce Act (1970) stipulated the minimum interval between legal separation and divorce to be 5 years, but in 1987 this was reduced to 3 years. Although only about 50% of legal separations are followed through to a final divorce (where the official sanctions of marriage disappear completely) only a negligible proportion of legal separations actually lead to reconciliation between spouses (Barbagli 1990). Given this context, an analysis of marital dissolution in Italy is best carried out by focusing on legal separations rather than on divorces, although legal separation does not formally dissolve marriage, but simply authorizes the husband and wife to live separately. Indeed, in Italy legal separation is comparable with divorce in the countries here considered for comparative purpose (USA, UK, and France). In this article, we do not consider dissolution of cohabitations, as their diffusion is very recent in Italy (see Sect. 2).

For further information with regard to the methodology employed, see Castiglioni and Dalla Zuanna (2007). The probabilities have been projected extrapolating the observed probabilities of marital separation by each marriage duration, without introducing further behavioral hypotheses.

This point is of particular interest in that during the 1990s, income development rates in the provinces of the Centre–North (measured by current prices) varied widely. The increase in the annual per capita income ranged from +7% for a few of the provinces in the North–East (i.e., Gorizia, Treviso, Verona, Vicenza, and Bolzano) to below +4% for the provinces of Belluno (Veneto), of Genova and Imperia (Liguria), and of Livorno (Toscana). In the late 1990s, income level was quite variable, ranging from 51 million lire annually per capita in Milan to slightly more than 26 million in Massa Carrara (Toscana).

One program, for example, gives a cash allowance to those families with at least three children under the age of 18 and below a certain income level. More specifically, since 1999 the sum of 120 euros a month has been given to families for every child from the third-born on. For a detailed analysis of the political measures in favor of families with children (conducted on a national and regional level), refer to the internet site: http://www.politichefamiliari.stat.unipd.it.

References

Barbagli, M. (1990). Provando e riprovando. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Barbagli, M., Castiglioni, M., & Dalla Zuanna, G. (2003). Fare famiglia in Italia. Un secolo di cambiamenti. Bologna: il Mulino.

Barban, N., & Dalla Zuanna, G. (2007). Giovani veneti vecchi e nuovi. In Osservatorio Regionale sulle Immigrazioni (Ed.), Immigrazione straniera in Veneto. Dati demografici, dinamiche del lavoro, inserimento sociale. Rapporto 2006. Franco Angeli: Milano.

Bettio, F., & Villa, P. (1998). A Mediterranean perspective on the break-down of the relationship between participation and fertility. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 22(2), 137–171.

Billari, F. C. (2004). Choices, opportunities and constraints of partnership, childbearing and parenting: The patterns in the 1990s. Background paper of the European Population Forum, Geneva (Switzerland) 12–14 January.

Billari, F. C., & Borgoni, R. (2002a). A multilevel sample selection probit model with application to contraceptive use. Paper presented at the 41st Conference of the Italian Statistical Society.

Billari, F. C., & Borgoni, R. (2002b). Spatial profile in the analysis of event histories: An application to first sexual intercourse in Italy. International Journal of Population Geography, 8, 261–275.

Billari, F. C., & Kohler, H. P. (2004). Patterns of low and lowest-low fertility in Europe. Population Studies, 58, 161–176.

Billari, F. C., & Rosina, A. (2004). Italian latest-late transition to adulthood: An exploration of its consequences on fertility. Genus, 60(1), 71–87.

Billari, F. C., Dalla Zuanna, G., & Loghi, M. (2005). Assessing the impact of national and regional incentives assessing the impact of family-friendly monetary transfers in a lowest-low fertility setting. IUSSP, XXV General Conference, July 18–23, Tours, France.

Billari, F. C., Philipov, D., & Baizan, P. (2001). Leaving home in Europe: The experience of cohorts born around 1960. International Journal of Population Geography, 7, 339–356.

Bonifazi, C., Menniti, A., Misiti, M., & Palomba, R. (1999). Giovani che non lasciano il nido. IRP/W.P.01/1999, Roma.

Bressan, F., Zenga, E., & Rocchi, E. (2005). Natalità a Verona: analisi diacronica e prospettive. In P. Di Nicola & M. G. Landuzzi (Eds.), Crisi della natalità e nuovi modelli riproduttivi: chi raccoglie la sfida della crescita zero? (pp. 147–177). Milano: Franco Angeli.

Buzzi, C., Cavalli, A., & de Lillo, A. (Eds.) (2002). Giovani del nuovo secolo. Quinto rapporto IARD sulla condizione giovanile in Italia. Bologna: il Mulino.

Caldwell, J., & Schindlmayr, T. (2003). Explanations of the fertility crisis in modern societies: A search for commonalities. Population Studies, 57(3), 241–263.

Caltabiano, M. (2006). Recenti sviluppi della fecondità per coorti in Italia. Dipartimento di Scienze Statistiche, Working Paper, 2. www.stat.unipd.it/v2/ricerca/wp.

Caltabiano, M., Dalla Zuanna, G., & Rosina, A. (2005). Interdependence between sexual debut and church attendance in Italy, Demographic Research, 14, 453–484, www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol14/19/.

Cantisani, G., & Dalla Zuanna, G. (1999). The new fertility transition in Europe. Have the gaps been bridged? In Proceedings of the Third African Population Conference (Vol. 3, pp. 503–520). Durban, South Africa, UAPS-IUSSP.

Castiglioni, M. (2004). First sexual intercourse and contraceptive use in Italy. In G. Dalla Zuanna & C. Crisafulli (Eds.), Sexual behaviour of Italian students (pp. 19–39). Department of Statistics, University of Messina.

Castiglioni, M., & Dalla Zuanna, G. (1988). Le variazioni nel livello di istruzione e nel comportamento fecondo: un’analisi empirica. Atti della XXXIV Riunione Scientifica della SIS, 3, 89–92.

Castiglioni, M., & Dalla Zuanna, G. (1994). Innovation and tradition: Reproductive and marital behaviour in Italy in the 1970s and 1980s. European Journal of Population, 10(2), 107–142.

Castiglioni, M., & Dalla Zuanna, G. (2007). A Marriage-cohort analysis of marital dissolutions in Italy. WP of the Department of Statistical Sciences, University of Padova, Italy, http://www.stat.unipd.it.

Chiesa in Italia, Annali. (2002–06). Supplement of the journal il Regno, Edizioni Dehoniane, Bologna.

Comune di Milano. (2005). Secondo rapporto sulla situazione demografica e sanitaria Milanese 2004. Comune di Milano, Settore Statistica, Quaderni di Documentazione e Studio, 45.

Coppi, R. (2005). L’indicatore di secolarizzazione. Critica liberale, 12(111), 4–9.

Corijn, M., & Klijzing, E. (Eds.) (2001) Transitions to adulthood in Europe. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Dalla Zuanna, G. (2001). The banquet of aeolus. A familistic interpretation of Italy’s lowest low fertility. Demographic Research, 4, http://www.demographic-research.org/

Dalla Zuanna, G. (2004). Few children in strong families. Values and low fertility in Italy. Genus, 60(1), 39–70.

Dalla Zuanna, G., & Righi, A. (1999). Nascere nelle cento Italie. ISTAT, Coll. Argomenti, 18, Roma.

Dalla Zuanna, G., & Ronzoni, G. (2003). Meno preti, quale chiesa? Bologna: Edizioni Dehoniane

Dalla Zuanna, G., De Rose, A., Racioppi, F. (2005). Low fertility and limited diffusion of modern contraception in Italy during the second half of twentieth century. Journal of Population Research, 22(1), 21–48.

De Rose, A. (1992). Socio economic factors and family size as determinants of marital dissolution in Italy. European Sociological Review, 8, 71–91.

De Rose, A., & Di Cesare, M. (2003). Genere e scioglimento della prima unione. In: A. Pinnelli, F. Racioppi, & R. Rettaroli (Eds.), Genere e demografia (pp. 339–365). Bologna: il Mulino.

De Rose, A., & Rosina, A. (1999). Scioglimento delle unioni. In P. De Sandre, A. Pinnelli, & A. Santini (Eds.), Nuzialità e fecondità in trasformazione: percorsi e fattori del cambiamento (pp. 379–391). Bologna: il Mulino.

De Sandre, I., & Dalla Zuanna, G. (1999). Correnti socioculturali e comportamento riproduttivo. In P. De Sandre, A. Pinnelli, & A. Santini (Eds.), Nuzialità e fecondità in trasformazione: percorsi e fattori del cambiamento (pp. 273–294). Bologna: il Mulino.

De Sandre, P., & Ongaro, F. (2003). Fecondità, contraccezione, figli attesi: cambiamenti e incertezze. In Comune di Milano (Ed.), Fecondità e contesto: tra certezze e aspettative. Dalla Seconda Indagine Nazionale sulla Fecondità alla realtà locale. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Di Giulio, P., & Rosina, A. (2007). Intergenerational family ties and the diffusion of cohabitation in Italy. Demographic Research, 16, 441–468, www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol16/14/.

Diotallevi, L. (Ed.) (2005). La parabola del clero. Torino: Edizione della Fondazione Giovanni Agnelli.

Esping-Andersen, G. (Ed.) (2007). Family formation and family dilemmas in contemporary Europe. Bilbao, Spain: Fundacion BBVA.

EurLife. (2005). Database on living conditions and quality of life in Europe, www.eurofound.eu.int.

Ferro, I. (2005). Le dinamiche naturali e migratorie nell’area fiorentina. Paper presented at workshop: Demografia e sviluppo della città – La popolazione a Firenze, Firenze, 1 dicembre 2005.

Ferro, I., & Salvini, S. (2006). Separazione e divorzio in Italia, le tendenze e le differenze regionali. Paper presented at the workshop: Instabilità familiare: aspetti causali e conseguenze demografiche, economiche e sociali, Messina, 10–11 November.

Ferro, I., Salvini, S., & Vignoli, D. (2006). Percorsi lavorativi, vulnerabilità economica e instabilità matrimoniale: quali relazioni? Paper presented at the workshop Instabilità familiare: aspetti causali e conseguenze demografiche, economiche e sociali, November 10–11, Messina (Italy).

Ginsborg, P. (1989). Storia d’Italia dal dopoguerra a oggi. Torino: Einaudi.

Guizzardi, L. (2007). La transizione all’età adulta in Italia e in Europa: un’analisi comparativa. In P. Donati (Ed.), Famiglie e bisogni sociali: la frontiera delle buone prassi (pp. 26–55). Milano: Franco Angeli.

Iacovu, M. (2002). Regional differences in the transition to adulthood. Annals of the America Academy of Political and Social Science, 580, 40–69.

Impicciatore, R., & Billari, F. (2007). Do civil marriage and premarital cohabitation have a negative impact on marital stability? Empirical evidence for the Italian case. Paper presented at PAA Annual Meeting, April, New York.

Istat. (1986). Atti del convegno La famiglia in Italia. Annali di statistica, serie IX, Vol. 6.

Istat. (1997). La fecondità nelle regioni italiane. Analisi per coorti. Anni 1952–1993. Collana Informazioni, 35, Roma.

Istat. (2005). Rapporto annuale 2004. Roma.

Khoo, S.-E., McDonald, P., Giorgias, D., & Birrel, B. (2002). Second generation Australians. Australian Centre of Population Research and the Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, Canberra, Australia.

Kohler, H.-P., Billari, F. C., & Ortega, J. A. (2002). The emergence of lowest-low fertility in Europe during the 1990s. 28(4), 641–680.

Lesthaeghe, R. (1995). The second demographic transition in Western countries: An interpretation. In K. O. Mason & A.-M. Jensen (Eds.), Gender and family changes in industrialized countries. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Livi Bacci, M. (1977). A history of Italian fertility during the last two centuries. Princeton, USA: Princeton University Press.

Livi Bacci, M. (2001). Too few children and too much family. Daedalus, 3, 139–156.

Livi Bacci, M. (2004). The narrow path of policies. Genus, 60(1), 207–231.

Magherini, C. e L. Mencarini (2001). La fecondità a Firenze. 1981–2000. Un’analisi dei dati anagrafici. Paper presented at the Workshop: La bassa fecondità italiana fra costrizioni economiche e cambio di valori, 8–9 November, Statistical Department, University of Florence.

Mazzuco, S. (2006). The impact of children leaving home on the parents’ wellbeing: A comparative analysis of France and Italy. Genus, 62(3–4), 35–52.

McDonald, P. (2000). Gender equity in theory of fertility transition. Population and Development Review, 26, 427–439.

Mencarini, M. L. (2007) Sistema di genere asimmetrico e bassa fecondità. In G. Gesano, F. Ongaro, & A. Rosina (Eds.), Rapporto sulla popolazione. L’Italia all’inizio del 21° secolo (pp. 83–85). Bologna: il Mulino.

Mencarini, L., & Tanturri, M. L. (2004). Time use, family role-set and childbearing among Italian working women. Genus, 60(1), 111–137.

Mulder, C. H. (2006). Home-ownership and family formation. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 21, 281–298.

Ongaro, F. (2002). Low fertility in Italy between explanatory factors and socio and economic implications: consequences for research. In Proceedings of the 41st Meeting of the Italian Statistical Society, Plenary and Specialized Sessions, 13–18, Cleup, Padova.

Ongaro, F. (2006). I giovani e la prima autonomia residenziale: analisi del ritardo. In Atti dei Convegni Lincei, Convegno Famiglie, nascite e politiche sociali, Roma, 28–29 aprile 2005, Bardi Editore, Roma.

Ongaro, F. (2007). Il comportamento riproduttivo. In G. Gesano, F. Ongaro, & A. Rosina (Eds.), Rapporto sulla popolazione. L’Italia all’inizio del 21° secolo (pp. 61–86). Bologna: il Mulino.

Ongaro, F., & Salvini, S. (2003). Variazioni lavorative e passaggi di parità. In M. Livi Bacci & M. Breschi (Eds.), La bassa fecondità italiana fra costrizioni economiche e cambio di valori, Presentazione delle indagini e dei risultati (pp. 151–168). Udine: Forum.

Palomba, R., & Schinaia, G. (1999). Nest leaving or staying at home? Paper presented at the European Population Conference, The Hague, 30 August–3 September.

Piazza, M. (2003). Le trentenni fra maternità e lavoro alla ricerca di una nuova identità. Mondadori Saggi, Milano, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore.

Pinnelli, A. (1995). Women’s condition, low fertility, and emerging union patterns in Europe. In K. O. Mason & A. M. Jensen (Eds.), Gender and family change in industrialized countries. Oxford: Claredon Press.

Rampichini, C., & Salvini, S. (2001). A dynamic study of the work-fertility relationship in Italy. Statistica, 61(3), 386–405.

Regina, F., Salvini, S., & Vignoli, D. (2003). La popolazione a Firenze. Il profilo demografico della città. Firenze: Comune di Firenze.

Reher, D. (1998). Family ties in Western countries: persistent contrasts. Population and Development Review, 24(2), 203–234.

Righi, A. (1997) La nuzialità. In M. Barbagli & C. Saraceno (Eds.), Lo stato delle famiglie in Italia (pp. 53–64). Bologna: il Mulino.

Rivellini, G., Micheli, G., Rosina, A., & Preda, M. (2006). Instabilità e modernizzazione: un’analisi ecologica a livello provinciale. Paper presented at the workshop Instabilità familiare: aspetti causali e conseguenze demografiche, economiche e sociali, November 10–11, Messina (Italy).

Rivellini, G., Rosina, A., & Preda, M. (2005). Instabilità familiare e modernizzazione: ripartendo da un esercizio di analisi ecologica e georeferenziata. Paper presented at the workshop Instabilità familiare: aspetti causali e conseguenze demografiche, economiche e sociali, September 15–16, Urbino (Italy).

Rosina, A. (2001). Questa unione informale non s’ha da fare. Matrimonio e famiglia: un binomio indissolubile in Italia? Paper presented at the workshop La bassa fecondità fra costrizioni economiche e cambio di valori, Firenze, Dipartimento Statistico, 1–2 December.

Rosina, A., & Fraboni, R. (2004). Is marriage loosing its centrality in Italy? Demographic Research, 11, 149–172. www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol11/6/

Salvini, S. (2004). Low Italian Fertility: the Bonaccia of Antilles? Genus, 60(1), 19–38.

Salvini, S. (2005). Aspetti territoriali delle separazioni e dei divorzi in Italia: 1984–2002. Paper presented at the workshop Instabilità familiare: aspetti causali e conseguenze demografiche, economiche e sociali, September 15–16, Urbino (Italy).

Santini, A. (1988). Natalità e fecondità, in IRP (National Institute for Population Research) Secondo rapporto sulla situazione demografica in Italia, 61–74, Roma.

Santini, A. (1995). Continuità e discontinuità nel comportamento riproduttivo delle donne italiane nel dopoguerra: tendenze generali della fecondità delle coorti nelle ripartizioni tra il 1952 e il 1991. Working Paper no. 53, Dipartimento Statistico Università di Firenze.

Santini, A. (1997). La fecondità. In M. Barbagli & C. Saraceno (Eds.), Lo stato delle famiglie in Italia (pp. 113–121). Bologna: il Mulino.

Saraceno, C. (1994). The ambivalent familism of the Italian welfare state. Social Politics, 1, 60–82.

Schroder, C. (2006). Cohabitation in Italy: Do parents matter? Genus, 62(3), 53–85

Sgritta, G. B. (1999). Too late, too low. The difficult process of becoming adult in Italy. In Jacob Fundation Conference, The transition to adulthood: Explaining national differences, Marbach Castle, 28–30 October.

Sobotka, T. (2004). Is lowest-low fertility in Europe explained by the postponement of childbearing? Population and Development Review, 30(2), 195–220.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix. The Challenges of Calculating Fertility Rates for Foreign Women

Appendix. The Challenges of Calculating Fertility Rates for Foreign Women

Assigning a value to the fertility of foreign women who live in Italy is not a simple task as their fertility histories are intimately tied to their migratory experience. In Table 12, we provide three different measures of fertility for Italian and foreign women reported in 2004 and in 2006. The data from 2004 come from Istat’s information on both TFR and the ratio of births to women age 18–49. The data for 2006 report the fertility of mothers of a representative sample of 8,000 Italian and 8,000 foreign students in junior high schools. As these women were born around 1960–65, their reproductive lives are nearly over. Upon comparing the results from these different sources, however, one immediately notices the rather large discrepancy between the fertility of Italians and foreign women in terms of TFR, and the more moderate differences between the two groups when using the other measures. This is particularly true with regard to the “final” measure by cohorts, which is not influenced by the reproductive calendar.

In light of these differences, it seems unwise to employ the period TFR to measure the fertility of foreign women. The period TFR refers to the average number of children a woman would have, if throughout her reproductive life, she were to bear children at the current age-specific fertility rates. Given that the number of foreign women in Italy has risen incredibly rapidly in the past few years, the premise on which period TFR is based doesn’t seem to be appropriate for observing differences between Italian and foreign women, especially given the latter’s deeply interconnected migratory and reproductive histories. Consequently, we chose to use as our reference measurement the general fertility rate (Births/Women 18–49) which, although also a period measure, is less sensitive to the concentration of births within certain age groups. The downside of this measurement is that it does not allow us to take into account the age structure of women of reproductive age. In any case, the similarity between the comparison of Italian and foreign women made using this measure, and that using a retrospective cohort estimate, confirmed that this was not a poor decision.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Castiglioni, M., Dalla Zuanna, G. Marital and Reproductive Behavior in Italy After 1995: Bridging the Gap with Western Europe?. Eur J Population 25, 1–26 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-008-9155-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-008-9155-9

Keywords

- Italy

- Marriage

- Cohabitation

- Living arrangements

- Legal marital separations

- Fertility changes

- Territorial pattern