Abstract

Over the past decade, a growing number of Anglo-American and Scandinavian researchers have documented the extent to which the university environment provides opportunities for workplace bullying. By contrast, there has been a visible lack of similar studies in non-Western national contexts, such as the Czech Republic and other Central Eastern European (CEE) countries. The present article addresses this gap by reporting the findings of the first large-scale study into workplace bullying among university employees in the Czech Republic. The exposure to bullying was assessed with the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R) in a sample of 1,533 university employees. The results showed that 13.6 % of the respondents were classified as bullying targets based on an operational definition of bullying (weekly exposure to one negative act), while 7.9 % of the respondents were identified as targets based on self-reports. This prevalence is comparable to bullying rates in Scandinavia but considerably lower than in Anglo-American universities. Differences between Anglo-American and Czech universities were also found with respect to the status of perpetrators (bullying was perpetrated mostly by individual supervisors in the Czech sample), perceived causes of bullying (structural causes perceived as relatively unimportant in the Czech sample), and targets’ responses to bullying (minimal use of formal responses in the Czech sample). The authors propose that cross-cultural differences as well as differences between the Anglo-American model of “neoliberal university” and the Czech model of university governance based on “academic oligarchy” can be used to explain these different findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The phenomenon of workplace bullying refers to a prolonged and repeated negative behaviour at work directed against one or more employees who are unable to defend themselves (Einarsen et al. 2003; Leymann 1996), leading to numerous negative outcomes for the affected workers (Einarsen and Mikkelsen 2003) as well as organizations (Hoel et al. 2003). Over the past two decades, research has demonstrated that workplace bullying is a relevant issue in almost every type of organization (see e.g., Einarsen and Skogstad 1996; Hoel and Cooper 2000), with the highest prevalence being reported in social and health sectors, public administration, and education (Zapf et al. 2003). Given the prominence of education on the list of risk sectors, it is interesting that, until the beginning of the new millennium, bullying in higher education was on the margins of researcher interest (Keashly and Neuman 2010; for exceptions see, Björkqvist et al. 1994; Lewis 1999; Spratlen 1995). However, the situation has changed notably during the past decade. With the diversification of bullying research and the restructuring of higher education in Western Europe and the U.S., a growing number of researchers have begun to explore the ways in which the academic environment provides opportunities for workplace bullying (cf. Keashly and Neuman 2010).

A number of studies have documented a relatively high bullying rates in higher education, mostly in university settings (see e.g., Björkqvist et al. 1994; Giorgi 2012; Keashly and Neuman 2008; Lampman et al. 2009; Lewis 1999, 2004; McCarthy et al. 2003; McKay et al. 2008; Simpson and Cohen 2004). The relatively high incidence of bullying in universities have been attributed to specific social and work features of the academic profession (Keashly and Neuman 2010) and, perhaps more prominently, to the recent corporatization of Western universities and other higher education institutions (Lewis 2004; Twale and De Luca 2008; Thornton 2004; Zabrodska et al. 2011). In particular, researchers have argued that the universities’ shift towards a market-oriented philosophy “has induced a resiling from the civility conventionally associated with universities” (Thornton 2004: 164) and contributed to a deterioration in workplace relations and an increase in bullying and incivility (Lewis 2004; Twale and De Luca 2008). The discussion of the negative impact of neoliberalism on higher education mirrors the critique of neoliberalism in other occupational sectors, in which bullying has been described as a form of managerial control characteristic of neoliberal workplaces and “an endemic feature of work relations in a capitalist society” (Beale and Hoel 2011: 7).

It is important to note, however, that the studies which focused on bullying in higher education have been almost exclusively conducted in Western contexts, predominantly Anglo-American countries (e.g., Keashly and Neuman 2008; Lampman et al. 2009; Lewis 1999; McCarthy et al. 2003; McKay et al. 2008). By contrast, there has been a visible lack of similar studies in non-Western national contexts, such as Central Eastern and Eastern European countries (an exception is a Turkish study conducted by Tigrel and Kokolan (2009)). Yet, as Einarsen et al. (2009) observe, important differences in organizational behaviour and practices exist across cultures, implying that the prevalence, forms, and perceptions of abusive behaviour at work may also differ. For this reason, it is vital to compare current findings regarding workplace bullying in higher education in Anglo-American cultures with studies undertaken in non-Western cultural settings. Such a comparison seems particularly important because so far little is known about the impact of different cultural contexts on the extent and experience of workplace bullying (Escartín et al. 2011).

Several recent studies have discussed cross-cultural variations in workplace bullying. Within the European context, for instance, it has been suggested (Giorgi 2012; Giorgi et al. 2011) that bullying is more widespread in Southern Europe than in Northern European countries. These differences have been linked to national values, such as a higher tolerance of bullying in masculine cultures in Southern Europe (Giorgi 2012). In addition, Hofstede’s model (1980) of four cultural dimensions has been used to propose that countries typified by low power distance, low uncertainty avoidance, and feminine values (e.g., Northern Europe) exhibit a lower prevalence of bullying in the workplace, while in countries with high power distance, high uncertainty avoidance, and masculine orientation (e.g., Southern Europe), bullying is both more prevalent and acceptable (Escartín et al. 2011). Power et al. (2011) also found that cultures with a short-term and high performance orientation consider bullying more acceptable than do human-oriented cultures. However, in this recent surge of interest in cross-cultural variations in workplace bullying, the Czech Republic and other Central Eastern European countries have rarely been considered.

The Czech Republic belongs to a cluster of Central Eastern European (CEE) countries, whose development was significantly hampered by 40 years of communist rule (1948–1989). After the fall of communism in 1989, CEE countries began a transformative process of integration into the European Union, retaining, however, work-related practices and values which differ from those in Western Europe (Kolman et al. 2003; Smith et al. 1996; Suutari and Riusala 2001). For instance, in a comprehensive European study on work-related values (Smith et al. 1996), CEE countries scored significantly lower on equality, and higher on hierarchy and conservativism than did Western European countries. Relatedly, workplace relations in CEE countries were found to be characterized by acceptance of power asymmetries, autocratic leadership, paternalism, and nepotism (ibid).Footnote 1 In the Czech Republic specifically, a study by Kolman et al. (2003) found that work-related values exhibited a large power distance, strong individualism and uncertainty avoidance, preference of masculine values, and a short-term orientation. As discussed above, these cultural tendencies are typically associated with a higher incidence and acceptability of workplace bullying (Escartín et al. 2011; Power et al. 2011). Overall, the few existing studies suggest that significant differences may exist in the prevalence and acceptability of workplace bullying between Central Eastern Europe and Western countries, and that an East–West comparison is a worthwhile but neglected area of bullying research.

This article addresses the lack of research into workplace bullying in CEE national contexts by reporting the findings of the first large-scale study into workplace bullying in the Czech Republic. In this way, the article makes a contribution to current knowledge of workplace bullying by examining this harmful phenomenon in a new and under-researched national context. The article also provides a detailed discussion on the organizational and social conditions linked to workplace bullying in the university sector, an organizational environment of growing interest in bullying research (McKay et al. 2008; Keashly and Neuman 2010). As McKay et al. (2008: 81) argue, understanding bullying in universities is vital because “the workplace experience of the academic impacts the education of students and the behaviours they take with them into the workplace.” Furthermore, the study provides new findings regarding some contested issues in workplace bullying research, such as demographic and work situation factors which increase the risk of bullying for specific employee groups (see Moreno-Jiménez et al. 2008).

Workplace Bullying in Higher Education

A recent review study conducted by Keashly and Neuman (2010) shows that the prevalence of bullying in higher education is relatively high and ranges between 18 % and 32 %.Footnote 2 In a study conducted in a U.S. university, Keashly and Neuman (2008) found that as many as 32 % of the respondents self-identified as targets of bullying, and 23 % were classified as bullying targets based on a checklist of negative behaviours. Lewis (1999) examined higher and further education institutions in Wales, finding that 18 % of the respondents reported being subjected to bullying, with 22 % witnessing bullying. Björkqvist et al. (1994) conducted a study in a Finnish university, showing that 24.4 % of women and 16.9 % of men had experienced bullying, and 32 % reported witnessing bullying in their university. McKay et al. (2008) examined bullying in a Canadian university, where 32 % of teaching faculty, instructors, and librarians reported “serious” bullying, and Giorgi (2012) found that its prevalence among administrative staff in an Italian university was 19 %. Overall, these findings seem to indicate that the prevalence of bullying in universities is considerably higher than in other occupational sectors. This conclusion is in contrast with a smaller number of comparative studies which found that bullying in higher education was less prevalent than in other sectors. For example, in a representative Norwegian study, Einarsen and Skogstad (1996) found that universities were among the occupational sectors with the lowest bullying rates. In another large-scale study, Hoel and Cooper (2000) found that only 7.2 % of employees in British higher education had been bullied during the past 6 months, as compared to 16.2 % in telecommunication and 15.6 % in teaching. However, as with research on bullying in other work sectors (see Nielsen et al. 2009), a comparison across university-based studies is complicated due to the disparate methodologies used.

In their review study, Keashly and Neuman (2010) identified several work and organizational features of the academic profession that might help explain the high bullying rates in higher education reported by most studies. For instance, drawing on conflict and aggression research, they note that longer relationships among employees provide greater opportunities for interpersonal conflicts, thus potentially increasing the incidence of bullying. For this reason, academia may be “a particularly vulnerable setting for such persistent aggression as a result of tenure, which has faculty and some staff in very long-term relationships with one another” (Keashly and Neuman 2010: 53). The authors also observe that academic workers characteristically have a strong sense of entitlement and demands for individual autonomy which, if unmet, may trigger bullying. Other potential factors include high performance expectations typical of academia which are combined with subjective and vague criteria for performance evaluation (Keashly and Neuman 2010; Tigrel and Kokolan 2009). The ambiguity in evaluations of employees may lead to perceptions of injustice triggering bullying (Keashly and Neuman 2010) and provide perpetrators in supervisory positions with numerous opportunities to negatively influence their subordinates’ work lives. Finally, Keashly and Neuman (ibid: 60) observe that the strongly valued imperative of academic freedom seems to prevent faculty from engaging with interpersonal conflicts at work, thus “allowing situations to escalate, resulting in a toxic climate and an increased likelihood of aggression and bullying”.

Apart from specific organizational and work features, researchers have discussed the changing nature of academic work as a potential factor increasing the incidence of bullying. A number of researchers (e.g., Lewis 2004; Thornton 2004; Twale and De Luca 2008) have argued that newly reformed neoliberal universities, with their micro-management of ever-increasing productivity, competitiveness, and individualization, create conditions that incite workplace bullying and other forms of employee abuse (Zabrodska et al. 2011). By neoliberalization (or corporatization) of academia, researchers generally refer to the transformation of Western universities from institutions producing public good to institutions directed by the values of entrepreneurialism and profit-making (Thornton 2004). This shift has initiated a number of significant organizational changes, some of which are perceived by university employees as integral to workplace bullying. These include, for instance, reduced public funding, increased research and teaching loads, short-term contracts, a preference for authoritarian management, and increasing power asymmetries among academics and managers (McCarthy et al. 2003; Lewis 2004; Simpson and Cohen 2004; Thornton 2004).

It is important to bear in mind, however, that the above factors have been identified by studies conducted in Anglo-American higher education. The situation in Czech higher education (and specifically, in universities) differs significantly. After 1989, the integration of the Czech Republic into the European Union resulted in a transformation of Czech higher education (Dobbins and Knill 2009; Pabian 2009). While the aim of the transformation was to emulate the higher education system in Western Europe, a unique model was produced (Pabian 2009). In particular, following the extreme state control of universities during communism, post-1989 Czech universities have gained considerable independence (Dobbins and Knill 2009), their system of governance being described as “academic oligarchy” or “Humboldian model of academic self-rule” (Dobbins and Knill 2009). Thus, a recent study of Czech universities (Hundlova et al. 2010) found that governance at all levels (university, faculty, department) was dominated by academics in managerial positions, whilst the influence of other actors, including students, the state, and external actors (e.g. businesses), was minimal.

While the dominance of the “academic self-rule” continues to today in Czech public universities, the ideal of liberal university begins to be disputed by emerging discourses of marketisation of higher education. These discourses have been promoted by the Czech government who argue that a transition to a more market-oriented education is needed to increase international competitiveness (Pesik and Gounko 2011). The goals of this neoliberal-inspired reform are summarized in the White Paper on Tertiary Education (2009); these include a shift towards corporate governance, the involvement of external actors, cooperation with businesses, and cost-sharing (e.g., implementation of student tuition fees). The reform, however, has been deeply contested by many Czech academics. The representatives of Czech universities argued that it would threaten the universities autonomy, transform university to for-profit organization, and intensify problems with the current underfinancing of Czech universities (Pesik and Gounko 2011).

The current situation in Czech public universities therefore does not correspond to the model of “neoliberal university” or “academic capitalism” (Brown and Clignet 2000) as it has been discussed in Anglo-American contexts, but can be best described as a unique mix of the Humboldian model of academic self-rule combined with the emerging elements of the market orientation (Pesik and Gounko 2011). Relatedly, some of the current pressures faced by Czech universities also seem to differ from market-oriented Anglo-American universities. According to a recent survey (Mateju and Fischer 2009), weak management, lack of strategic vision, and ineffective financial management were experienced by Czech academics as pressing problems of Czech public universities, particularly among younger employees. Given these different organizational and social conditions in Czech and Anglo-American universities, it can be expected that the prevalence and forms of bullying may also differ.

Aim of the Study

The aim of the present study was to extend the current knowledge of workplace bullying in higher education by examining the prevalence and forms of workplace bullying among university employees in the Czech Republic. The study comprised a survey conducted at three large public Czech universities in the academic year 2010/2011 and follow-up interviews with 40 targets and witnesses of bullying (conducted by the first author). Due to space limitations, we constrain ourselves in this article to the discussion of the main finding from our survey. The specific objectives of the survey were the following. First, the survey aimed to examine how many research participants had been subjected to bullying, how many had witnessed bullying, and what the most prevalent forms of bullying were. The second aim was to collect additional information regarding the experience of bullying, including the status of targets and perpetrators, perceived causes of bullying, the duration of bullying, and targets’ responses to bullying.

Method

Data Collection

The Czech academic community is small and the phenomenon of workplace bullying has rarely been openly discussed in this organizational context. Considering this, we presumed that research participants could be concerned about their anonymity. Our priority was therefore to ensure full confidentiality for the university employees who participated in our study. For this reason, we decided to conduct the study via an electronic questionnaire which protects the anonymity of the participants and simultaneously contributes to their openness (Hewson et al. 1996). The electronic questionnaire was sent to three large public universities in three different regions of the Czech Republic, allowing us to collect data from a wide range of respondents spanning diverse regions, faculties, and disciplines. Before administering the questionnaire, the first author sought permission to conduct the research from the upper management of the three selected universities. After obtaining the permissions, a link to our web-based questionnaire was provided via university e-mail to the university employees and Ph.D. candidates, together with relevant information about the research.Footnote 3 The questionnaire was described as being focused on “the quality of workplace relations, including workplace bullying”, rather than solely on workplace bullying. We opted for this broader description to ensure that a wider range of participants responded than only employees who had had personal experience of workplace bullying.

Sample

In total, 1,558 university employees responded to our call. After elimination of incomplete questionnaire responses, we obtained a research sample of 1,533 respondents (F = 58.0 %, M = 42.0 %). All age groups were represented, spanning 25 to 75 years of age, with the most represented age group being 30–39 years (30.8 %). The majority of participants were academic workers employed in research and teaching (51.9 %). Ph.D candidates also involved in teaching and research made up 30.1 % of the respondents, and 18.0 % worked in administration, finance and services. In terms of research discipline, 54.3 % of the respondents were employed in the natural sciences, 33.5 % in social sciences and humanities, 6.8 % in technical and formal sciences, and 5.3 % in other fields (e.g., sport sciences). Most respondents had been employed with their current employer for 1–5 years (36.3 %), with 18.9 % having been employed with the same university for 6–10 years, 17.2 % for 11–20 years, and 14.7 % for more than 20 years.

Measurements

We designed our own questionnaire based on previously established findings concerning workplace bullying in higher education (for an overview see, Keashly and Neuman 2010). The questionnaire was divided into seven sections. The first section included questions concerning the demographic characteristics of the respondents (age, gender, family status, nationality). The second section consisted of questions about the respondents’ employment (formal position, academic degree, length of employment, type of contract, etc.). The third section addressed the quality of workplace relations and the work climate at the respondent’s workplace. The fourth section measured perceived exposure to workplace bullying.

In order to assess the incidence of bullying, we used the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R—Einarsen et al. 2009) adapted to Czech by a standard back translation procedure. The NAQ-R is currently the most commonly used instrument for the measurement of exposure to workplace bullying (Power et al. 2011). Evidence of its satisfactory validity and reliability was provided by Einarsen et al. (2009) as well as by numerous other studies, including those using modified versions of the NAQ-R (e.g., Giorgi et al. 2011; Giorgi 2012). The adapted Czech version showed a reasonably high reliability (Cronbach’s α = .89), which is comparable to reliability reported by Einarsen et al. (2009).

The NAQ-R combines two strategies for measuring the incidence of workplace bullying. The first strategy corresponds to “behavioral approach” (referred to also as “operational approach”, see Giorgi 2012; Nielsen et al. 2009) and requires respondents to evaluate how often they had been subjected to 22 negative acts during the past 6 months, with the response alternatives: “Never,” “Now and then,” “Monthly,” “Weekly” and “Daily”. While the NAQ-R measures the exposure to 6 months prior, the reporting period was extended to 12 months in our study. The reason for this modification was that academics typically spend extended periods of time outside their workplace (e.g., working from a home-office or travelling), which indicates that the period of 6 months may be too short to adequately reflect their experience with negative workplace behaviour.

In addition to the behavioral approach, the NAQ-R incorporates 1 item in which respondents assess the extent to which they have been subjected to bullying based on a well-established definition (“self-labeling approach”). The following definition, provided by the NAQ-R was used:

We define bullying as a situation where one or several individuals persistently over a period of time perceive themselves to be on the receiving end of negative actions from one or several persons, in a situation where the target of bullying has difficulty in defending him or herself against these actions. We will not refer to a one-off incident as bullying.

The respondents were asked whether, based on this definition, they had been subjected to workplace bullying during the past 12 months, with the response alternatives “No”, “Yes, but only rarely”, “Yes, now and then, “Yes, several times per week”, “Yes, almost daily”. This item which measures the subjective perception of being bullied was used to evaluate the criterion validity of the Czech version of the NAQ-R. The overall score from the exposure to 22 negative acts correlated with the subjective perception of being a bullying victim (r = .50, p < .01). This level of validity is almost as high as reported by Einarsen et al. (2009).

The fifth section of the questionnaire was reserved for respondents who considered themselves to be targets of bullying. These respondents were asked additional questions regarding the experience of bullying, such as who the main perpetrators were, duration of the experience, perceived causes of bullying, individual responses to bullying, etc. The respondents were also provided space where they could describe up to three examples of their bullying experiences. The sixth section of the questionnaire measured perceived exposure to student-initiated bullying and was reserved for respondents who had taught at least one course during the past 12 months. In the final section of the questionnaire, we asked the respondents to evaluate the research and provide their e-mail contacts in case of willingness to participate in follow-up interviews.

Results

Prevalence and Forms of Bullying

When provided a definition of workplace bullying, 7.9 % of the respondents reported that they had been bullied during the past 12 months at least occasionally and 0.7 % reported that they had been bullied at least weekly. Regarding the indirect experience of bullying, 28.8 % of the respondents reported that they had witnessed others being bullied during the past 12 months. In addition, 13.8 % of the respondents reported that they had been bullied in their previous job. Of these, 38.8 % had been bullied in a job at a university, 35.3 % in the public sector, and 21.9 % in the private sector. These findings showed that workplace bullying was relevant and recognizable problem for the respondents. The relevance of this issue was also made apparent in the evaluation section of the questionnaire in which 87.4 % of the respondents reported that they considered research into bullying at universities to be an important subject of study.

When administered the list of 22 negative acts, 13.6 % of the respondents reported that they had experienced at least one negative act ‘at least once a week’ during the past 12 months and could therefore be considered bullying victims (Einarsen et al. 2009; Zapf et al. 2003). When using a stricter criterion proposed by Mikkelsen and Einarsen (2001) of being exposed to at least two negative acts ‘at least once a week’, 6.8 % of the respondents could be classified as bullying victims. The most commonly reported negative acts experienced by the respondents on a weekly basis were work-related. In particular, the respondents reported ‘being ordered to do work below their level of competence’ (5.8 % of the respondents had experienced this negative behaviour at least weekly), ‘being exposed to an unmanageable workload’ (3.3 %), and ‘having their opinions and views ignored’ (2.9 %). The list of the most commonly experienced negative acts is presented in Table 1. Following Hoel and Cooper (2000), we have made a distinction between occasional and regular exposure to negative behaviour. Occasional exposure combines categories “now and then” and “monthly”, whereas regular exposure combines the answers for “weekly” and “daily”.

Targets

Analyses were undertaken to examine if there were particular risk groups of bullying victims. A significant difference was found with respect to the length of employment (χ 2 = 12,16, df = 4, p < .05; Cramers’s V = .09). The respondents who had spent less than 1 year and more than 20 years in their present job self-identified more often as targets of bullying than respondents who had been in their present jobs for 1–5 years, 6–10 years, or 11–20 years. No significant differences between the two groups were found with respect to other demographic and work variables, including age (χ 2 = 2.24, df = 4), gender (χ 2 = 2.65, df = 1), academic degree (χ 2 = 3.15, df = 3), type of contract (χ 2 = 1.33, df = 4), or family status (χ 2 = 0.43; df = 1).

In addition to self-labeling, we examined whether there were any risk groups based on exposure to the 22 negative acts. We divided the respondents into two groups: those who had been bullied in their present job (i.e. respondents who had experienced at least one negative act at least weekly during the past 12 months), and those who had not. The percentage of those who had been exposed to at least one negative act on a weekly basis was significantly higher among employees aged 25–29 and significantly lower among employees aged 60–69 years (χ 2 = 22.37, df = 6, p < .01; Cramer’s V = .12). Respondents in the natural sciences were more frequently exposed to negative acts than employees in the humanities and social sciences (χ 2 = 36.02, df = 2, p < .01; Cramer’s V = .16). No significant differences were found with respect to gender (χ 2 = 0.30; df = 1), family status (χ 2 = 8.48, df = 7), academic degree (χ 2 = 5.59, df = 3), length of employment (χ 2 = 10.01, df = 6), or type of contract (χ 2 = 1.77, df = 4).

Perpetrators

The results showed that the formal position of the perpetrator in the university hierarchy was a crucial factor. Of those respondents who considered themselves to be bullied during the past 12 months, 73.3 % reported that they had been bullied by their superior/s. Considerably fewer respondents reported being bullied by a colleague/s (23.3 %). Only two respondents reported being bullied by a subordinate or a student. The results further showed that bullying was most frequently perpetrated by only one person (62.2 %). Two to four persons were involved in 36.3 % of the reported cases. Only one respondent reported having been bullied by more than five people. Regarding the gender of the perpetrator/s, 52.7 % of the respondents reported that they had been bullied by a man, whilst 36.9 % were bullied by a woman. Both a man and a woman were involved as reported by 7.7 % of the respondents.

Perceived Causes of Bullying

A list of plausible causes of bullying was presented to the respondents who were asked to indicate which of the listed items they considered to be the cause/s of bullying directed toward them.

As Fig. 1 shows, the most commonly experienced cause of bullying was seen to be ‘the personality of the perpetrator’ (65.9 %). Some respondents specified the perpetrator’s personality in semi-closed responses, using descriptions such as “psychopathic”, “narcissistic”, “aggressive”, and “uncertain about himself/herself”. The second most frequently experienced cause was ‘poor management’ (59.3 %), indicating that the respondents perceived organizational factors related to managerial incompetence as another central factor. ‘Ideological disagreements’, ‘rivalry’, ‘personal animosity’ between the targets and the perpetrator/s were also considered important causes. Interestingly, in almost one quarter of the reported cases, respondents believed that the perpetrators were unaware of their involvement in bullying (‘lack of awareness’). A surprisingly small number of the respondents nominated financial or structural motives (economic crisis, downsizing, etc.) as the cause of the bullying, indicating that socio-political factors were perceived as relatively unimportant.

Duration of Bullying

The majority of the respondents bullied during the past 12 months reported that the bullying had been a long-term experience, lasting for 1–5 years (28.9 %). For 11.1 % of the respondents, bullying had lasted longer than 5 years. However, a considerable number of the respondents also reported that bullying lasted 6–12 months (23.3 %) or 1–6 months (26.7 %), indicating that their experience was relatively recent.

Responses to Bullying

Finally, we aimed to identify actions which the targeted employees took to stop bullying. When presented with a plausible list of actions, the majority of the respondents reported ‘discussing the problem with work colleagues’ (44.9 %) and ‘discussing the problem with friends’ (40.7 %). A considerably smaller number of the respondents tried to stop bullying by ‘discussing the problem with superior/s’ (24.6 %) or by ‘confronting the perpetrator/s’ (22.9 %). A smaller number again (7.6 %) sought psychological counselling. Notably, only 1.7 % of the targeted respondents had lodged a formal grievance. Those respondents who reported that they had not taken any action to stop bullying made up 11.0 %.

Discussion

Our findings clearly showed that Czech universities are not immune to workplace bullying: 7.9 % of the respondents reported that they had been targets of occasional bullying during the past year, and 0.7 % reported being bullied on a weekly basis. These percentages are relatively consistent with findings reported by studies which were conducted in Scandinavia and which used similar strategies of measurement. For instance, in a comparative Norwegian study, Einarsen and Skogstad (1996) obtained very similar results, finding that, in their university sample, 6.2 % of the respondents reported being bullied at least occasionally, and 0.7 % weekly. In a study among Finnish professionals, Salin (2001) found that 8.8 % of the respondents reported being bullied at least occasionally and 1.6 % at least weekly. Thus, the self-reported bullying frequencies obtained in our sample did not indicate significant differences in the prevalence of bullying between professionals in Scandinavia and in the Czech Republic. This is also true for the prevalence of bullying assessed by the behavioural approach. In our sample, 13.6 % of the respondents were classified as bullying targets based on a criterion of being exposed to at least one negative act at least weekly, while 6.8 % were classified as bullying targets based on a stricter criterion of exposure to at least two negative acts. In a recent representative study among Norwegian employees which also used the NAQ-R, Nielsen et al. (2009) arrived at similar results, finding that 14.3 % of their respondents were classified as targets of bullying based on the first criterion, and 6.2 % based on the second criterion. We can therefore conclude that neither the self-labeling nor the behaviour strategy suggest that bullying prevalence in our research sample differs in any significant way from the prevalence reported by Scandinavian studies employing a similar methodology.

By contrast, a comparison with non-Scandinavian studies which also used a similar methodology shows that the prevalence of bullying in our sample is considerably lower. For instance, studies in Southern Europe which used a 17-item version of the NAQ-R found that, compared to the 6.8 % in our sample, as many as 19 % of Italian non-academic university employees (Giorgi 2012) and 15.2 % of employees of varied Italian organizations (Giorgi et al. 2011) were identified as victims of bullying based on the strictest criterion of exposure to at least two negative acts weekly. Considering that both Southern Europe and the Czech Republic have been described as national regions with relatively high power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and masculine orientation (Escartín et al. 2011; Kolman et al. 2003), these varied findings are interesting. Yet, a comparison between these studies must be made with caution because they were conducted among different employee groups. While we showed that some factors potentially increase the risk of bullying among academics, the incidence of bullying in this group may still be lower than in other employee groups, as indicated by the comparative studies discussed above (e.g., Hoel and Cooper 2000). Thus, it is possible that the bullying rates among non-academic workers in the Czech Republic would be higher than in our, mostly academic, sample and would correspond more closely to studies in Southern Europe.

Interestingly, a comparison with studies conducted in Anglo-American universities also shows that the bullying rates in our sample are much lower. As discussed above, most university-based studies reported the prevalence of bullying as being between 18 % and 32 % (e.g., McKay et al. 2008; Simpson and Cohen 2004). For instance, in the U.S. study conducted by Keashly and Neuman (2008), 32 % of the respondents self-identified as targets of bullying, and 23 % were identified as bullying targets based on behavioural measurements (though the list of negative acts differed from the one used by the NAQ-R). Because of the disparate methodologies used, these different findings, however, do not necessarily indicate that the incidence of bullying in Czech universities is lower than in Anglo-American universities. Most likely, the lower incidence in our research sample should be at least partially attributed to the stringent definition of workplace bullying used in our study. Most studies conducted in Anglo-American universities employed a broader definition of bullying than the one used by the NAQ-R. These studies also often did not specify the time frame of the bullying (Keashly and Neuman 2010), thus potentially measuring much longer exposure than only 12 months. It is therefore possible that some of these studies overestimated the prevalence of bullying in university settings.

At the same time, the lower prevalence in our research sample as compared to Anglo-American universities can be caused by other factors linked to cross-cultural differences. In particular, cross-cultural studies have indicated that considerable differences exist regarding the threshold for experiencing negative behaviours as abusive (Escartín et al. 2011). Different bullying rates across countries may therefore reflect cultural variations in the acceptability of bullying behaviours (Power et al. 2011). Thus, the negative acts which are experienced as bullying by employees in UK or U.S. universities may be perceived by Czech employees as relatively commonplace conflicts, thus reducing the likelihood that these employees would remember and report these acts. Unfortunately, the only cross-cultural study on the acceptability of workplace bullying (Power et al. 2011) did not include the Czech Republic. The effect of cultural tolerance on the bullying rates reported in our sample is therefore difficult to evaluate. A relatively high mean score on the acceptability of bullying in other CEE countries (Power et al. 2011) nonetheless indicates that the tolerance of negative acts in the Czech Republic may be higher than in Anglo-American contexts, thus reducing the reported prevalence of bullying.

Finally, we cannot disregard the possibility that the incidence of bullying is in fact lower in Czech universities than in Anglo-American universities due to the different organization of the education systems, including the differences linked to the neoliberalization of Anglo-American universities. As discussed above, a number of key aspects of neoliberal universities—which have been linked to bullying in Anglo-American university-based studies (e.g., Lewis 2004; Lampman et al. 2009)—are yet to be implemented in the Czech context, including a shift in university governance from academics to external managers, the introduction of tuition fees which transforms students into clients, or the emphasis on research and teaching as a marketable commodity. In addition, considering the relative autonomy of Czech universities from external demands, such as businesses, it is plausible to assume that Czech academic cultures are less productivity-driven and therefore less competitive than Anglo-American universities, which may also reduce the incidence of bullying among Czech academics. Thus, the different systems of university governance in Czech and Anglo-American universities may explain the currently lower bullying rates in Czech universities, but also predict a future increase in bullying with the transition toward the neoliberal model.

In line with previous research which has measured exposure to negative behaviours (e.g., Nielsen et al. 2009; Salin 2001), we found that the most frequently experienced negative acts reported by our respondents were work-related. In particular, the respondents reported being ordered to do work below their level of competence, being exposed to an unmanageable workload, and having their opinions and views ignored. In their discussion of faculty bullying, Keashly and Neuman (2010: 53) observed that “the behaviors most frequently cited in academia involve threats to professional status and isolating and obstructional behavior”. These negative behaviours seem to be prominent “due to the critical importance placed in academia on one’s accomplishments, intellectual rigor, and reputation” (ibid: 53). Our findings support this observation. Being forced to work below one’s level of competence or having one’s opinions ignored clearly damages one’s professional reputation. At the same time, being ordered to work below one’s competence can be regarded as an obstructional behaviour as it prevents the targeted employees from dealing with more important or prestigious tasks, thus reducing their opportunities for career development and promotion. However, it should be noted that these work-related forms of bullying have also been reported to be the most prevalent in other work sectors (e.g., Salin 2001), and thus do not seem to be specific to the university environment.

As Zapf et al. (2003) observe, relatively little information is available concerning the status of targeted employees. Moreover, studies aiming to identify specific demographic and work variables that increase the risk of being bullied have yielded contradictory results (Moreno-Jiménez et al. 2008). In our study, we found that employees who had spent less than 1 year and more than 20 years in their present job more often reported being bullied than did other employees. This finding indicates that two groups of university employees are at higher risk of bullying: recent employees and employees who have spent most of their career in the same workplace. The higher risk for the first group corresponds with Rayner’s (1997) observation that bullying in universities often coincides with moving to a new job. A more recent study among Spanish municipal employees (Moreno-Jiménez et al. 2008) also found that most bullying was reported by employees with the shortest work experience. The newly employed may be at higher risk of being targeted due to their lack of familiarity with the organizational culture, their status as outsiders (see Zapf and Einarsen 2003), as well as their relatively low organizational status (Moreno-Jiménez et al. 2008). The higher self-reported incidence of bullying among the second group, on the other hand, seems to support the hypothesis discussed by Keashly and Neuman (2010: 53) that “the longer and more interactive the relationship, the greater the opportunity for conflict and potential for aggression”. After more than two decades in one job, these long-term employees may be involved in numerous organizational conflicts and power struggles, which may increase the likelihood that they themselves become targets of bullying. Overall, these findings indicate that both a very short and a very long period of employment in one workplace may represent a risk factor.

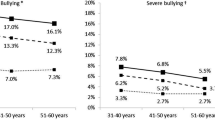

The identification of risk groups based on exposure to negative acts showed that young employees under 29 experienced more negative acts than any other age group, whilst employees above 60 experienced fewer negative acts that any other age group. A plausible explanation for these findings seems to be the different positions of younger and older employees in the organizational hierarchy. In university settings, organizational position is strongly dependent on one’s academic degree which is generally unavailable to employees under 29. By contrast, employees above 60 typically hold senior positions at the highest levels in the university hierarchy, which presumably protects them from negative behaviour. A similar finding was reported by Einarsen and Skogstad (1996) who found that, in a Norwegian university sample, respondents above 50 years of age were significantly less bullied than younger respondents. (This finding was not reported in other work sectors.). Overall, the higher exposure of young employees to bullying in our sample indicates that the position of these employees is considerably less satisfactory than the position of older employees and that an intergenerational gap exists in the workplace experiences of younger and older employees in Czech universities. This finding may provide further explanation for the stronger support of the Czech university reform from younger employees (Mateju and Fischer 2009), as this reform will presumably transform current academic practices and power hierarchies in Czech universities.

Interestingly, we also found that employees in the natural sciences more often experienced negative acts than employees in the humanities and social sciences. As the ethnography by Stockelova (2009) of Czech sciences indicates, the organizational practices and cultures in these scientific disciplines differ considerably in the Czech context, with the natural sciences evincing more signs of the recently promoted neoliberalization than humanities and social sciences. The higher exposure to bullying in the natural sciences in our research sample is therefore of a particular interest, as it may provide evidence for the assumption that neoliberalization impact negatively on the quality of workplace relations in higher education, for instance due to an increased work-load, competitiveness, and tendency towards “top-down managerialism” (Thornton 2004: 163). However, there may be other organizational and work features specific to the natural sciences which contribute to the higher exposure in this discipline, such as longer working hours due to experimental work or higher interdependence among team members. Further research is needed to explore this issue.

Regarding the perpetrators of bullying, we found a number of significant factors. In almost 2/3 of the reported cases, individuals in supervisory positions were identified as perpetrators, indicating that bullying was strongly related to the organizational power derived from the perpetrator’s formal position. Our findings are in line with British studies which have also found a strong prevalence of supervisor bullying (e.g., Beale and Hoel 2011; Simpson and Cohen 2004). By contrast, university-based research in North America tends to report a more balanced ratio between supervisor and co-worker bullying (see e.g., Keashly and Neuman 2008; 2010; McKay et al. 2008). For instance, Keashly and Neuman (2008) found that 39 % of the faculty in their study identified their peers as perpetrators, and 36 % identified their superiors. As previous research implies (Escartín et al. 2011), the prevalence of supervisory bullying in our sample indicates that strong hierarchical relations exist in Czech universities. This interpretation can be supported by several studies (e.g., Kolman et al. 2003; Smith et al. 1996) which found that the Czech Republic, together with other CEE countries, exhibited a high score on power distance, which indicates a relatively high acceptance of inequality (Hofstede 1980). Such acceptance presumably increases the risks of supervisory bullying as compared to co-worker bullying because supervisors may feel entitled to misuse power by virtue of their formally superior position. The tendency towards supervisory bullying may be further multiplied by the model of academic oligarchy characteristic of Czech universities. As we would suggest, academic oligarchy can provide a fruitful ground for supervisory bullying because governance at the faculty and department level is held by a relatively small group of academics in managerial positions who have considerable power over key decisions, including HR issues. The combination of strong institutional autonomy, limited external control, and lack of anti-bullying policies suggests that if some of these employees decide to resort to bullying, they may be in relatively easy position to do so.

Regarding other attributes of the perpetrators, we found that the majority of bullying cases were perpetrated by a single person, rather than by two or more persons. This finding is in contrast with a number of previous studies which have found that collective forms of bullying were more prevalent than bullying perpetrated by only one person (e.g., Keashly and Neuman 2010; Leymann 1996; Zapf 1999). Our finding can be attributed to the fact that the majority of perpetrators in our sample were superiors who are usually individuals (rather than collectives). In addition, the number of perpetrators has been found to be associated with the duration of bullying. As Zapf and Gross (2001) found, the longer the duration, the more perpetrators tend to become involved. In our sample, half of the reported cases lasted less than 12 months (and were presumably still continuing), implying that more perpetrators had not yet had the opportunity to become involved. Perhaps more importantly, the lower number of perpetrators may reflect the nature of academic work, which tends to be highly individualistic and autonomous (at least in the Czech Republic), thus limiting opportunities and perhaps willingness for more participants to be involved (see also Keashly and Neuman 2010).

Finally, we found that men were more likely to be identified as perpetrators than women. This is in line with previous research which consistently shows that “men seem to be clearly over-represented among the bullies in most studies” (Zapf et al. 2003: 113). The prevalence of men among bullying perpetrators has been explained by the fact that men usually hold more powerful positions in organizations than women (Zapf et al. 2003) and thus have more opportunities to engage in bullying. This explanation seems relevant also for Czech universities, as the overwhelming majority of positions in university senior management and at higher academic levels are held by men (Prudky et al. 2010). For example, in 2010, women comprised only 11 % of all professorial positions at Czech universities (ibid). Since the majority of perpetrators in our sample were superiors, and since the majority of superiors were presumably men, our finding that men were also more often identified as perpetrators is not surprising.

The perceived causes of bullying are highly subjective, particularly when their identification is based solely on targets’ responses (Zapf 1999). In our sample, the most frequently perceived cause was the personality of the perpetrator. This finding is not unexpected, as previous surveys and interviews with bullying targets showed that the perpetrator’s personality (particularly its “pathological” features) is typically experienced by targets as one of the prominent causes (see e.g., Björkqvist et al. 1994; Tracy et al. 2006; Zapf 1999). The second most important cause reported by the respondents was poor management. This finding is also consistent with previous studies which highlighted poor management as a central antecedent of bullying (e.g., Hoel and Cooper 2000; Kelloway et al. 2004). For example, in Lewis’s (1999) university-based study, respondents felt that a lack of professionally trained managers was the most prominent cause of bullying. The problem of poor management may be even more pronounced in the Czech model of academic oligarchy, in which faculties and departments are generally governed by academics without formal managerial training and who, consequently, may have proper scientific skills, but lack managerial competency (as indicated in follow-up interviews with targets of bullying). Other important causes reported by our respondents included ideological disagreements, rivalry, and personal animosity, indicating that bullying was attributed to personal antipathies and internal power struggles among employees.

Notably, structural and financial causes were not experienced as an important factor in our research sample. This is in contrast to the strong emphasis on structural change as a potential cause of bullying in studies examining bullying in Anglo-American higher education (see Lewis 1999, 2004; Thornton 2004). For example, Lewis (1999) reported that increasing pressure on public organizations and growing financial control were identified by his respondents as crucial factors contributing to the increased bullying in British tertiary education. Our finding indicates that, in contrast to Anglo-American higher education, structural changes have not so far had a strong impact on Czech university employees. This interpretation is plausible, as the corporatization of higher education, which has been discussed as a major factor in the increased bullying rates in Anglo-American universities, has not yet been put into practice in the Czech Republic. As a recent study (Pabian 2012) found, even partial reforms have not so far been successfully implemented in Czech universities because they were discrepant with dominant institutional practices and were not embraced by academics themselves. Thus, rather than resulting from the structural changes induced by corporatization of the university sector as discussed in Anglo-American contexts, bullying in Czech universities seems to be linked with individual pathologies, poor management, and internal power struggles among employees.

Most studies report that bullying tends to be long-lasting, with an average duration between 15 and 18 months (Zapf et al. 2003). In our study, 40 % of the respondents reported that the duration of bullying was more than 12 months. However, as many as 50 % of the respondents reported that the bullying lasted less than 12 months, indicating that their experience of bullying was of a recent date. The relatively short duration of the bullying reported by our respondents may be at least partially attributed to the relative flexibility of academic work in the Czech Republic. It is not uncommon for Czech academics to combine a job in a university with projects at other institutions; e.g., research institutes or private universities. Thus, when problems arise at one workplace, targeted employees may opt for an early exit from the job and a move to another institution with which they already cooperate (as also became apparent in follow-up interviews with targeted employees).

As Lutgen-Sandvik (2006) pointed out, researchers have so far paid relatively little attention to the actions which the targeted employees use to resist bullying. To date, only a few surveys have included questions regarding the targets’ reactions to bullying (e.g., Hoel and Cooper 2000; McKay et al. 2008). Similarly to these studies, we found that targeted employees in our sample mostly responded informally by talking about the problem to their co-workers and friends. These actions were presumably taken in order to receive social support and possibly also to devise a strategy to defy the perpetrator/s. Discussing the problem with one’s superior or confronting the perpetrator were less common, presumably because these actions involve considerable risk and can further escalate bullying (Lutgen-Sandvik 2007). Of particular interest is the minimal use of formal strategies reported by our respondents, which contrasts with studies conducted in Anglo-American cultures. For instance, while Hoel and Cooper (2000) in their UK study also found a preference for informal responses, about 1/4 of their respondents reported bullying to unions/staff associations, and almost 1/10 used the organization’s grievances mechanisms. By contrast, the use of grievances was exceptional in our sample, and none of the bullied employees reported contacting unions or other professional bodies (e.g., academic senates). The lack of formal responses among our respondents is most likely due to the absence of formal mechanisms for the management of bullying at Czech universities, and possibly also due to employees’ distrust of formal procedures.

Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions

This study has contributed to the global picture of workplace bullying by demonstrating that workplace bullying represents a relevant problem in the so far under-research national context of the Czech Republic. While a considerable number of our respondents reported both direct and indirect experience with bullying, the prevalence rates in our sample were still relatively low in an international comparison. This can be caused by number of factors, including a possible higher tolerance of bullying behaviours in Czech employees, inconsistent methodology used across previous studies, or the fact that universities may exhibit lower bullying rates compared to other sectors. We also proposed that the lower prevalence in our sample as compared to Anglo-American universities may reflect the differences between the Anglo-American model of neoliberal university and the Czech system of governance based on academic self-rule. In particular, the lower incidence in our sample may indicate that workplace bullying is indeed more widespread in neoliberal universities than in universities which have not yet been corporatized, such as public universities in the Czech Republic; a finding that would support the link between neoliberalism and workplace bullying proposed by other studies (e.g., Beale and Hoel 2011; Thornton 2004). Further research is needed to explore this possibility.

The study has also added value to workplace bullying research in that it provided a detailed discussion of organizational and social conditions that incite bullying in higher education, with a close focus—unique in the international context—on the university sector in a post-communist country. In comparison with Anglo-American universities, some interesting differences were found. In contrast to most Anglo-American studies, bullying in the Czech sample was predominantly an individual affair, perpetrated by only one person in a supervisory position, rather than by colleagues or collectives. In addition, structural and financial factors were not seen as important causes of bullying among the Czech respondents, a view which will presumably change after neoliberal-inspired reforms are implemented in Czech universities. Finally, our findings point to a marked lack of formal responses to bullying in the Czech sample, indicating that Czech universities are not well-prepared to deal with bullying cases. Considering the substantial negative effects of bullying on employee productivity and other organizational outcomes (Hoel et al. 2003), our findings suggest that Czech universities should be advised to implement anti-bullying policies to address the issue.

Our findings also highlight the importance of specific demographic and work variables which increase the risks of being bullied in the university environment. In our sample, employees who had spent less than 1 year and more than 20 years in their present job, young employees between 25 and 29 years of age, and employees in the natural sciences reported the most bullying. These findings indicate that age, length of employment, and research field represent important factors in the occurrence of bullying in universities, whereas demographic variables such as gender and marital status may be less significant. Our findings thus contribute to current discussions regarding the identification of risk groups across diverse organizational contexts (e.g., Moreno-Jiménez et al. 2008) and provide an incentive for future studies to explore a wider range of work-situation variables. These findings also have important practical implications, as they suggest that preventive measures could be taken to protect those employees at increased risk of being bullied. For example, universities in the Czech Republic could implement mentoring programs for young employees and integration programs for the newly employed to reduce the risk of these employees being targeted.

The study, nonetheless, has several limitations. First, our findings draw on the self-reports of a self-selected sample of university employees, and their generalizability is therefore limited. Second, although the bullying rates reported in our study are based on internationally recognized criteria, these criteria have not been unanimously accepted. For instance, some studies identify bullying victims based on exposure to one act weekly; others use the criterion of exposure to two acts weekly. Researchers (e.g., Giorgi 2012) who used an alternative estimation method based on a cluster analysis found that the latter, stricter criterion seems to provide a more precise estimation of bullying prevalence. Third, any discussion on cross-cultural differences in bullying prevalence has to be approached with caution because workplace bullying studies differ in definitions and measures of bullying. The most valid comparison of our findings can be made with studies that used the NAQ-R and were conducted on a sample of academic workers. Because such studies have so far been rare, we compared our findings to studies that were either conducted in higher education institutions and/or used similar methodology. While some of these studies were recent, others were of older date, which might have biased the comparison. Finally, the study’s focus was necessarily limited and not all relevant issues were addressed. For instance, the study examined the relationship between targets and perpetrators, but the role of other vital actors, such as witnesses or university management, was not addressed. Further research could explore the role of these actors in more detail.

Our findings have several other implications for the future research. Above all, the difficulties in comparing the bullying prevalence across national contexts emphasize the importance of more systematic cross-cultural research based on unified measures of bullying, such as the NAQ-R. Our findings also illustrate the need for a more systematic focus on the relationship between workplace bullying and organizational structures and practices within specific work sectors. As Power et al. (2011: 6) observe, specific industries develop their own cultures, which can significantly influence the practices and acceptability of bullying, and may even “have a higher influence than the culture of the individual countries”. For this reason, it is not sufficient to study workplace bullying only in relation to cross-cultural differences, but it must also be studied with regard to specific organizational sectors within each country. In the Czech Republic specifically, a study of bullying beyond universities is needed, as other work sectors would presumably exhibit different prevalence, forms, and risk groups than reported in our study. Such organization-specific knowledge would then allow the design and implementation of anti-bullying policies targeted at specific industries, thus increasing their efficiency.

Future research would also benefit from a more complex methodology than used in our study. Qualitative or mixed-methods designs would provide more complex and nuanced insights into the organizational practices that stimulate workplace bullying within specific industries. As our findings indicated, a fruitful area of such research in the university sector could involve a more sustained cross-cultural comparison of different systems of university governance (e.g., neoliberal model as compared to academic oligarchy) and of their impact on the incidence of bullying and other forms of unethical workplace behaviour. In light of current turbulent debates on the transformation of higher education globally, an understanding of how these different systems influence employee workplace experiences and well-being is highly relevant.

Notes

Some of these tendencies, including the acceptance of power hierarchies, can be explained by the continuing communist legacy in CEE countries. As Suutari and Riusala (2001: 251) discuss, despite the communist rhetoric of equality, the organizational structure during communism was highly formalized and “[t]he power differential between management and workers was very large and the hierarchy was clear and well-established.” This legacy may still effect work relations in today’s Czech society, particularly in state organizations, which have been much slower to transform than privately owned companies.

We exclude those studies which defined separate incidents as bullying (e.g., McCarthy et al. 2003).

Due to administrative regulations at Czech universities, we were prohibited from contacting our respondents directly, but were required to do so via an e-mail distributed by university administrators. This was a considerable limitation, as it prevented us from establishing the number of employees who received the questionnaire and thus the response rate. However, no other approach was viable under the current regulations.

References

Beale, D., & Hoel, H. (2011). Workplace bullying and the employment relationship: exploring questions of prevention, control and context. Work, Employment and Society, 25, 5–18.

Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Hjelt-Bäck, M. (1994). Aggression among university employees. Aggressive Behaviour, 20, 173–184.

Brown, R. H., & Clignet, R. (2000). Democracy and capitalism in the academy: The commercialization of American higher education. In R. H. Brown & J. D. Schubert (Eds.), Knowledge and power in higher education. A Reader (pp. 17–48). New York: Teachers College Press.

Dobbins, M., & Knill, C. (2009). Higher education policies in Central and Eastern Europe: convergence toward a common model? Governance, 22, 397–430.

Einarsen, S., & Mikkelsen, E. G. (2003). Individual effects of exposure to bullying at work. In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace. International perspectives in research and practice (pp. 127–144). London: Taylor & Francis.

Einarsen, S., & Skogstad, A. (1996). Bullying at work: epidemiological findings in public and private organizations. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5, 185–201.

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C. L. (2003). The concept of bullying at work: The European tradition. In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace. International perspectives in research and practice (pp. 3–30). London: Taylor & Francis.

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Notelaers, G. (2009). Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised. Work & Stress, 23, 24–44.

Escartín, J., Zapf, D., Arrieta, C., & Rodríguez-Carballeira, Á. (2011). Workers’ perception of workplace bullying: a cross-cultural study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20, 178–205.

Giorgi, G. (2012). Workplace bullying in academia creates a negative work environment. An Italian study. Employees Rights and Responsibilities Journal. Online First, doi:10.1007/s10672-012-9193-7

Giorgi, G., Arenas, A., & Leon-Perez, J. M. (2011). An operative measure of workplace bullying: the Negative Acts Questionnaire across Italian companies. Industrial Health, 49, 686–695.

Hewson, C. M., Laurent, D., & Vogel, C. M. (1996). Proper methodologies for psychological studies conducted via the internet. Behavioral Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 28, 186–191.

Hoel, H., & Cooper, C. L. (2000). Destructive conflict and bullying at work. Manchester School of Management, UK: UMIST. Retrieved from http://www.socialpartnershipforum.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/UMIST%20report.pdf

Hoel, H., Einarsen, S., & Cooper, C. (2003). Organizational effects of bullying. In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace. International perspectives in research and practice (pp. 145–161). London: Taylor & Francis.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences. International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Hundlova, L., Provazkova, K., & Pabian, P. (2010). Kdo vladne ceskym vysokym skolam? [Who governs at Czech universities?]. Aula, 18, 2–16.

Keashly, L., & Neuman, J. H. (2008). Final report: Workplace behaviour (bullying) project survey. Mankato: Minnesota State University. Retrieved from http://www.mnsu.edu/csw/workplacebullying/workplace_bullying_final_report.pdf

Keashly, L., & Neuman, J. H. (2010). Faculty experiences with bullying in higher education. Causes, consequences, and management. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 32, 48–70.

Kelloway, E. K., Sivanathan, N., Francis, L., & Barling, J. (2004). Poor leadership. In J. Barling, E. K. Kelloway, & M. R. Frone (Eds.), Handbook of workplace stress (pp. 89–112). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Kolman, L., Noorderhaven, N. G., Hofstede, G., & Dienes, E. (2003). Cross-cultural differences in Central Europe. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18, 76–88.

Lampman, C., Phelps, A., Bancroft, S., & Beneke, M. (2009). Contrapower harassment in academe: a survey of faculty experience with student incivility, bullying, and sexual attention. Sex Roles, 60, 331–346.

Lewis, D. (1999). Workplace bullying—Interim findings of a study in further and higher education in Wales. International Journal of Manpower, 20, 106–119.

Lewis, D. (2004). Bullying at work: the impact of shame among university and college lecturers. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 32, 281–299.

Leymann, H. (1996). The content and development of mobbing at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5, 165–184.

Lutgen-Sandvik, P. (2006). ‘Take this job and …’: quitting and other forms of resistance to workplace bullying. Communication Monographs, 73, 406–433.

Lutgen-Sandvik, P. (2007). How employees fight back against workplace bullying. Communication Currents, 2(1). Retrieved from http://www.communicationcurrents.com/

Mateju, P., & Fischer, J. (2009). Vyzkum akademickych pracovniku vysokych skol. [A survey of academic university employees]. Prague: Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports.

McCarthy, P., Mayhew, C., Barker, M., & Sheehan, M. (2003). Bullying and occupational violence in tertiary education: risk factors, perpetrators and prevention. Journal of Occupational Health and Safety, 19, 319–326.

McKay, R., Arnold, D. H., Fratzl, J., & Thomas, R. (2008). Workplace bullying in academia: a Canadian study. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 20, 77–100.

Mikkelsen, E. G., & Einarsen, S. (2001). Bullying in Danish work-life: prevalence and health correlates. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10, 393–413.

Moreno-Jiménez, B., Muñoz, A., Salin, D., & Morante Benadero, M. (2008). Workplace bullying in Southern Europe: prevalence, forms and risk groups in a Spanish sample. International Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 13, 95–109.

Nielsen, M. B., Skogstad, A., Matthiesen, S. B., Glasø, L., Aasland, M. S., Notelaers, G., & Einarsen, S. (2009). Prevalence of workplace bullying in Norway: comparisons across time and estimation methods. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 18, 81–101.

Pabian, P. (2009). Europeanisation of higher education governance in the post-communist context: the case of the Czech Republic. In A. Amaral et al. (Eds.), European integration and the governance of higher education and research (pp. 257–278). Dordrecht: Springer.

Pabian, P. (2012). Proc nevedou reformy vysokych skol k zamyslenym vysledkum? [Why higher education reforms do not lead to intended outcomes?] Paper presented at the workshop Mass higher education in institutional settings: An ethnography of Czech university departments. 6 Sept 2012, Prague, Czech Republic.

Pesik, R., & Gounko, T. (2011). Higher education in the Czech Republic: the pathway to change. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 41, 735–750.

Power, J. L., et al. (2011). Acceptability of workplace bullying: a comparative study on six continents. Journal of Business Research, Online First, doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.08.018

Prudky, L., Pabian, P., & Sima, K. (2010). Ceske vysoke skolstvi. Na ceste od elitniho k univerzalnimu vzdelavani 1989–2009 [Czech higher education: From elite to universal education 1989–2009]. Prague: Grada.

Rayner, C. (1997). The incidence of workplace bullying. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 7, 199–208.

Salin, D. (2001). Prevalence and forms of bullying among business professionals: a comparison of two different strategies for measuring bullying. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10, 425–441.

Simpson, R., & Cohen, C. (2004). Dangerous work: the gendered nature of bullying in the context of higher education. Gender, Work and Organization, 11, 163–186.

Smith, P. B., Dugan, S., & Trompenaars, F. (1996). National culture and the values of organizational employees. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 27, 231–264.

Spratlen, L. P. (1995). Interpersonal conflict which includes mistreatment in a university workplace. Violence and Victims, 10, 285–297.

Stockelova, T. (Ed.). (2009). Akademicke poznavani, vykazovani a podnikani. Etnografie menici se ceske vedy [Making, administering and enterprising knowledge in the academy: An ethnography of Czech science in flux]. Prague: SLON.

Suutari, V., & Riusala, K. (2001). Leadership styles in Central Eastern Europe: experiences of Finnish expatriates in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 17, 249–280.

Thornton, M. (2004). Corrosive leadership (or bullying by another name): A corollary of the corporatized academy? Australian Journal of Labour Law, 17, 161–184. Retrieved from http://firgoa.usc.es/drupal/files/AJLL_finalThornton.pdf.

Tigrel, Y. E., & Kokolan, O. (2009). Academic mobbing in Turkey. International Journal of Behavioral, Cognitive, Educational and Psychological Sciences, 1, 91–99. Retrieved from www.waset.org/journals/ijhss/v4/v4-10-93.pdf.

Tracy, S. J., Lutgen-Sandvik, P., & Alberts, J. K. (2006). Nightmares, demons, and slaves: exploring the painful metaphors of workplace bullying. Management Communication Quarterly, 20, 148–185.

Twale, D. J., & De Luca, B. M. (2008). Faculty incivility. The rise of the academic bully culture and what to do about it. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. A Wiley Imprint.

White paper on tertiary education (2009). Prague, CR: Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport. Retrieved from www.msmt.cz/White_Paper_on_Tertiary_Education_fin.pdf

Zabrodska, K., Linnell, S., Laws, C., & Davies, B. (2011). Bullying as intra-active process in neoliberal universities. Qualitative Inquiry, 17, 709–719.

Zapf, D. (1999). Organizational, work group related and personal causes of mobbing/bullying at work. International Journal of Manpower, 20, 70–85.

Zapf, D., & Einarsen, S. (2003). Individual antecedents of bullying: Victims and perpetrators. In Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace. International perspectives in research and practice (pp. 165–184). London: Taylor & Francis.

Zapf, D., & Gross, C. (2001). Conflict escalation and coping with workplace bullying: a replication and extension. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10, 497–522.

Zapf, D., Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Vartia, M. (2003). Empirical findings on bullying in the workplace. In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace. International perspectives in research and practice (pp. 103–126). London, UK: Taylor & Francis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The writing of this article was supported by the Czech Science Foundation research grant no. P407/10/P146 awarded to Katerina Zabrodska.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zabrodska, K., Kveton, P. Prevalence and Forms of Workplace Bullying Among University Employees. Employ Respons Rights J 25, 89–108 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-012-9210-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-012-9210-x