Abstract

Although there has been several efforts made to reduce land degradation and improve land productivity in Ethiopia, farmers’ investments in sustainable land management (SLM) remain limited. Nevertheless, the results regarding determinants of farmers’ investments in SLM have been inconsistent and scattered. Moreover, these factors have not been reviewed and synthesized. Hence this paper reviews and synthesizes past research in order to identify determinants that affect farmers’ investments in SLM practices and thereby facilitate policy prescriptions to enhance adoption in Ethiopia, East Africa and potentially wider afield. The review identifies several determinants that affect farmers’ investments in SLM practices. These determinants are generally categorized into three groups. The first group is those factors that are related to farmers’ capacity to invest in SLM practices. The results show that farmers’ investments in SLM practices are limited by their limited capacity to invest in SLM. The second groups of factors are related to farmers’ incentives for investments in SLM practices. Farmers’ investments in SLM are limited due to restricted incentives from their investments related to land improvement. The third groups of factors are external factors beyond the control of farmers. The review also shows that farmers’ capacities to invest in SLM and their incentives from investments have been influenced by external factors such as institutional support and policies. This suggests that creating enabling conditions for enhancing farmers’ investment capacities in SLM and increasing the range of incentives from their investment is crucial to encourage wide-scale adoption of SLM practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Land degradation in the form of soil erosion and nutrient depletion has been major a national agenda and remains an important issues in Ethiopia because of its adverse impact on crop productivity, the environment, food security and the quality of life in general (Hurni 1996; Bewket and Sterk 2002; Kassie et al. 2009). Productivity impacts of soil erosion and nutrient depletion are due to a decline in soil fertility and moisture availability on-site where soil erosion and nutrient depletion occur (Stroosnijder 2009) and off-site where sediments are deposited (Pender and Gebremedhin 2007). As a result, vast areas of fertile lands in Ethiopia have become unproductive (Bewket and Sterk 2002; Kassie et al. 2009). As a response to these severe soil erosion and nutrient depletion, huge investments in sustainable land management (SLM) have been implemented since the 1980s in the country in collaboration with several donors (Berhe 1996; Shiferaw and Holden 1998; Admassie 2000; Beshah 2003). In this review we take SLM to mean a comprehensive set of land management practices, with the potential of making significant and lasting differences in the near future and over the long term in terms of reducing land degradation and improving land productivity (after Liniger et al. 2011).

In Ethiopia (the focus of this review), farmers’ investments in SLM remain limited (Adimassu et al. 2012; Bewket 2007). An analysis of the determinants that influence farmers’ investments in SLM would help to understand why farmers often refrain from investing in their land and to develop strategies to improve their investments in SLM. In order to identify determinants that affect farmers’ investments in SLM, researchers typically select a number of potential independent variables for inclusion in their analysis based on prior theorization and test. Usually, logit, probit or tobit regression model was used to determine factors that affect farmers’ investments in SLM practices (Adimassu et al. 2012; Amsalu and De Graaff 2007; Pender and Gebremedhin 2007). Many studies indicated that SLM investments were influenced by several socioeconomic characteristics of the household, biophysical characteristics of farm plots (Gebremedhin and Swinton 2003; Kessler 2006; Requier-Desjardins et al. 2011) and institutional factors (Shiferaw and Holden 2000; Shiferaw et al. 2009). At the household level, differences between farm households concerning social, economic and cultural characteristics lead to differences in how much households invest in SLM (Adimassu et al. 2012; Amsalu and De Graaff 2007). Similarly, differences in biophysical conditions between the study plots such as slope, soil fertility status and size of plots influenced farmers’ choice of where to invest (Adimassu et al. 2012; Amsalu and De Graaff 2007). However, it is clear that the empirical records regarding these factors contain many ambiguities and inconsistent results. So, it is crucial to review and synthesize these inconsistent results and to ascertain whether there is a more discernible pattern among the variables typically included in a site-specific analysis of investments in SLM in Ethiopia.

Therefore, the main objective of this study is to investigate the major determinants of farmers’ investments in SLM in Ethiopia based on a comprehensive review and further synthesis of previous research results.

2 Methodology

Sustainable land management (SLM) practices comprise of both technologies and approaches (Liniger et al. 2011). In this paper only SLM technologies are considered. The most important SLM technologies considered include stone bunds (level/graded), soil bunds (level/graded), fanya juu (level/graded), tree planting, compost, farmyard manure (FYM), minimum tillage and contour plowing. Physical SLM practices such as stone and soil bunds were considered as practices with long-term economic benefits, while agronomic SLM practices such as application of compost and FYM were considered as practices with short-term economic benefits (Liniger et al. 2011). This is because physical SLM practices occupy and essentially remove considerable areas from the cultivable land which reduce the economic benefit (Adimassu et al. 2014). Electronic and hard copy literature sources were used to collect data on determinants of farmers’ investments in SLM technologies. Several key words were used in searching electronic literatures. These include investments, adoption, determinants, factors, willingness to pay, acceptability, constraints, challenges, soil and water conservation, SLM, land management, stone bunds, soil bunds, fanya juu, rehabilitation, trees, Ethiopian highlands, food-for-work, productive safety net (PSN), effects, impacts, economics of SLM, Ethiopia, etc. Moreover, publications in hard copies were obtained from libraries of different institutions such as Ministry of Agriculture (MoA), World Food Programme (WFP), Water and Land Resource Center (WLRC) and Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR).

To carry out the synthesis on the determinants of farmers’ investments in SLM, a database was created containing 30 variables used in more than 90 peer reviewed articles using Microsoft Excel and SPSS. For each of the variables, the number of incidences where its coefficient was significantly negative or positive was recorded. All significant coefficients at 10, 5, and 1 % were considered as significant for this synthesis. Before summarizing and analyzing the explanatory variables that affect farmers’ investments in SLM practices, it is necessary to present the description of each explanatory variable (Table 1). Of the variables, twenty-five were household characteristics, whereas only five were plot characteristics. The effects of these explanatory variables on farmers’ investments in SLM were summarized and further grouped into similar categories.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characteristics of published results

This section presents the highlights of characteristics of the studies reviewed regarding determinants of SLM practices in Ethiopia. The average sample size in these published articles was 399 with a standard deviation of 455 (Table 2). The sample size ranged from 94 respondents to 2900 respondents.

Probit, logit and tobit models were the most important econometric techniques applied in most of the adoption literature (Table 2). Accordingly, 46, 30 and 21 % of the studies employed were probit, logit and Tobit regressions, respectively. Only 4 % of the studies applied other techniques such as Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression and factor analysis (FA). In the studies reviewed, farmers’ investments in land management were considered as a binary choice in logit and probit models. This means logit and probit models are more conservative than the other tobit models in identifying the factors that affects farmers’ investments in land management. Logit and probit models are similar except in the distribution of the error term in which logit model assumes logistic distribution, while the probit model assumes standard normal distribution. Logit and probit models do not consider how much farmers actually invest on their land, and results from these models are similar. However, tobit model considers not only whether farmers invest or not on their plots but also how much do farmers invest on their land. Therefore, tobit models are more important to identify factors that affect how much do farmers invest in SLM on their plots. In terms of adoption of SLM practices by farmers, the logit and probit models identify factors that affect whether or not farmers invest in SLM practice on their plots, while tobit model identifies factors that affect farmers on how much farmers invest.

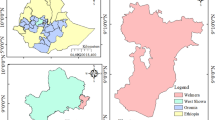

The geographical distribution of the studies reviewed is also shown in Table 2. Most of the studies were carried out in Tigray (37 %) and Amhara (25 %) regions of Ethiopia. This shows that the study is skewed to the North and North-western parts of the country where these two regions are located. This is mainly due to the fact that most SLM practices have been implemented in these two regions resulted from relatively severe land degradation (Berhe 1996; Hurni 1996). Moreover, these areas are characterized by rugged topography, highland altitude and relatively torrential rainfall.

3.2 Determinants of farmers’ investments in sustainable land management: review

This section presents the review of factors that affect farmers’ investments in SLM in Ethiopia at the household and plot levels.

3.2.1 Household-level determinants

Table 3 presents household-level determinants that affect farmers’ investments at a household level in SLM. As shown in Table 3, twenty-five household-level factors have been identified as affecting, negatively or positively, farmers’ investments in SLM practices. For example, the effect of age and farm experience of a farmer on investment in SLM practices can be either negative or positive, and older farmers (longer farm experience) were expected to have a positive effect on SLM investment because they have longer farming experience (Bekele and Drake 2003; Amsalu and De Graaff 2007). In contrast, younger farmers may have longer planning horizons and, hence, may be more likely to invest in SLM (Tiwari et al. 2008). Similar to age, the effect of education status of a farmer to invest in SLM is either positive or negative. This is because education increases farmers’ ability to acquire, process and use information about the negative effect of soil erosion to have a positive role in the decision to invest in SLM (Pender and Kerr 1998; Lapar and Ehui 2004; Pender and Gebremedhin 2007; Tiwari, et al. 2008). However, the negative effect is largely due to the fact that education increases a farmers’ analytical capacity to calculate the costs and benefits of SLM investments and they do not invest if they think that it is not profitable. Moreover, education can create better access to off-farm employment that makes them reluctant to land related investments such as SLM.

Land holdings including total land size of households, land per economically active family members and land per capita can have either positive or negative effect on famers’ investments in SLM practices. The positive effect is because of the fact that these factors are often correlated with the wealth that may help ease the needed financial constraint and the potential loss of land for conservation measures may not discourage investments on large farms (Kassie et al. 2008a, 2010; Beshir 2014). On the contrary, these factors are negatively correlated with farmers’ investments in SLM practices. The negative correlation between land holdings and farmers’ investments in SLM is because when land is more available farmers may not worry about land degradation and consequently may reduce their investment in land. Negative correlations between landholding and farmers’ investments in SLM practices have been reported by previous research findings in Ethiopia (Gebremedhin and Swinton 2003; Hagos and Holden 2006; Pender and Gebremedhin 2006). In most of the studies, family size and economically active family members influenced farmers’ investment in SLM practices positively (Clay et al. 1998; Gebremedhin and Swinton 2003; Pender and Gebremedhin 2007; Asrat et al. 2004). This is because most SLM practices (e.g., construction of bunds) are labor intensive to construct/maintain and hence households with large family labor can invest more in SLM practices (Pender and Gebremedhin 2007; Asrat et al. 2004). Moreover, the larger the family, the higher the probability that future generations will farm the land and use the future benefits of investment in SLM (Featherstone and Goodwin 1993).

Livestock holding such as livestock number per household, livestock number per hectare and number of oxen is generally considered to be an asset that could be used either in the production process or be exchanged for cash or other productive assets that help farmers’ to invest in SLM practices. However, the effects of livestock holding on farmers’ investments in SLM practices are inconsistent. This is because there are some farmers whose livelihoods depend on livestock production and do not want to invest in land improvement activities such as SLM.

3.2.2 Plot-level factors that affect farmers’ investments in SLM

Table 4 presents the results of the review of plot-level determinants of farmers’ investments in SLM. Only five major determinants affected farmers’ investments in SLM practices in Ethiopia. Like household-level determinants, the effects of plot-level determinants on farmers’ investments were inconsistent. The results show that plot size had positive correlation with farmers’ investment in SLM. This is partly because most physical SLM practices take proportionally more space on small plots and the benefit from conservation on such plots may not be enough to compensate for the decline in production due to the loss in area devoted to conservation structures. Similarly, the result show that farmers invest more in physical SLM practices on plots with steep slopes, which have higher, more obvious erosion risks and rates of loss as compared to plots with gentle slope (Ervin and Ervin 1982; Shiferaw and Holden 1998; Mbaga-Semgalawe and Folmer 2000). Effects of fertility condition of plots, plot distance and number of plots on farmers’ investments in SLM practices reviewed were inconsistent.

3.3 Determinants of farmers’ investments in sustainable land management: synthesis

The review of the determinants of farmers’ investments in SLM (Tables 3, 4) revealed that the empirical records contain a number of inconsistent results. To address this, an attempt is made to synthesize these inconsistent results and to ascertain whether there is a more distinct pattern among the variables typically included in a site-specific analysis of determinants of farmers’ investments in SLM (Table 5). This was done by grouping all of the variables into categories which are more plausible for policy makers and a wider, non-academic audience. As stated previously, most physical SLM practices were considered as investments for “long-term return,” while agronomic SLM practices were considered as investments for “short-term returns.” The rationale for this classification is that farmers’ investments in different SLM practices depend on the how quick the return from their investments is (Shiferaw and Holden 2001).

Table 5 presents the frequency analysis of 30 variables that determine farmers’ investments in SLM practices. Although the average effect of household and plot-level variables have similar trend for both long-term and short-term returns, there are some inconsistencies. For example, 87 % of the studies showed positive relation between land size and farmers investments in long-term SLM practices. However, 63 % of the studies showed negative relation between land size and farmers’ investments for short-term return.

Generally, as opposed to the review in Tables 3 and 4, the results in Table 5 showed clearer pattern of effect of variables on farmers’ investments in SLM. For example, the overall effect of variable related to landholding (LANDSIZE, LAND/LAB and LAND/LAB) shows that farmers with higher landholding invest more as compared to farmers with smaller landholding in both short and long-term investments. Similarly, labor availability (FAMSIZE, ECOACT) affects farmers’ investments in land management implying that farmers with higher family labor invested more as compared to farmers with lower family labor.

Education and knowledge (EDU, EXPERI, Aware-EROS, Aware-SLM and RADIO) influenced farmers’ investments in SLM positively. Similarly, factors related to financial capita (CREDIT, OFFFARMI, TLU, TLU/ha, OXEN) influenced farmers’ investments in SLM positively. This implies farmers with higher financial capital invested more in SLM as compared to farmers with lower financial capital. Farmers with better institutional support (EXTENSI, TRAINING, ROADIS, and MARDIS) invest more in SLM practices than farmers with poor institutional services.

Although the results in Table 5 show greater clustering than seen in Tables 3 and 4, further analysis is required for simple presentation of these factors. Accordingly, farmers’ investments in SLM are a direct function of two categories of variables: capacity to invest and incentives to invest. Farmers’ capacities to invest in SLM and the incentives of investments are, in turn, affected by external factors/conditioners such as lack of institutional support and poor infrastructure. This is shown graphically in Fig. 1 and further discussed below.

3.3.1 Capacity to invest in SLM practices

As shown in Fig. 1, a farmers’ capacity to invest in SLM depends on the household’s landholdings, labor availability, knowledge and experience, social capital, physical capital and financial capital. Limited investment in SLM by farmers might be due to the fact that farmers’ may not have enough landholding, knowledge/experience, social capital, physical capital and financial capital.

Landholding is the major source of wealth and livelihood in Ethiopia. The quantity and quality of land affect the types and intensity of investments which are technically feasible and profitable. Mostly, it has been hypothesized that farmers with larger plot and farm sizes are more capable of undertaking investments because they can spare land areas for terraces, for fallow, and for trees while putting larger portions of their lands under cultivation (Hayes et al. 1997; Asrat et al. 2004; Smith 2004). There are also empirical studies in other part of the world suggesting that farmers who hold large farms are more likely to invest in land management (Hayes et al. 1997; Asrat et al. 2004; Smith 2004; Tenge et al. 2004; Amsalu and De Graaff 2007; De Graaff et al. 2008). This is because farmers with more land can take more risks, including relatively high investment, if required, and survive crop failure due to pests, hailstones and excess rainfall (Nowak 1987; Reardon et al. 1996).

Labor availability in quantity and quality terms is critically important in land management. The quantity aspect of labor is important when considering labor as an input used in the labor-intensive land management activities such as construction of stone terrace. Empirical studies in Ethiopia and elsewhere have shown that large family size and economically active population have positive and significant effect in investment in labor-intensive land management practices (Pender and Kerr 1998; Mbaga-Semgalawe and Folmer 2000; Gebremedhin and Swinton 2003).

The quality of labor which includes the worker’s education and technical knowledge are also important to the farmers’ ability to make appropriate investment decisions (Smith 2004). The variable “education” has been included in many studies as a proxy for the capacity of the head of household to understand technical aspects related to land management (Jumbe and Angelsen 2007). In most of the studies, higher education levels are associated with more access to information on land degradation problem and improved land management measures (Swinton and Quiroz 2003; Sheikh et al. 2003). Education of the household head increased their ability to assess information, better understanding of the new technology and strengthened his/her analytical capabilities with new technology (Swinton and Quiroz 2003). Many authors report that education has a positive impact on farmers’ investments in improved land management technology in general (Mbaga-Semgalawe and Folmer 2000; Lapar and Ehui 2004).

Physical capital to invest in land management practices includes infrastructure and physical characteristics of plots. Steeper plots are more susceptible to higher rates of erosion and increase the incentive to invest in land management and to adopt less erosive forms of land use (Clay et al. 1998). The greater the land degradation in a village, the more likely the resident farmers will be to invest in land management (Clay et al. 1998; Gebremedhin and Swinton 2003). Empirical studies reveal that distance from homesteads to farmers’ fields affect the type and intensity of land management investment in Ethiopia (Pender and Gebremedhin 2007; Pender et al. 2004; Gebremedhin and Swinton 2003). Studies have shown that farmers are more likely to invest in land management (e.g., application of compost/farm yard manure) on plots closer to their residence is partly due to the difficulty of transporting inputs to distant plots (Clay et al. 1998; Nkonya et al. 2004, 2005).

Financial capital consists of not only cash but also liquid assets such as livestock and crop sales that are used to finance an investment in land management. Livestock and crop sales, off-farm activities and credit are the main sources of cash for Ethiopian farmers (Pender and Gebremedhin 2007). Livestock husbandry is a boon to farm investments as it provides cash income (Hayes et al. 1997). Greater ownership of livestock is associated with greater use of beneficial land management practices, probably because income generated from livestock products helps farmers afford to buy inputs (Hayes et al. 1997; Pender and Gebremedhin 2007). Another financial capital is the availability of credit. Research on adoption of land management technologies indicates that there is a positive relationship between the level of adoption and the availability of credit in sub-Saharan Africa (Shiferaw and Holden 1999; Benin and Pender 2001; Pattanayak et al. 2003; Yirga 2007). Evidence from Zambia shows that farmers’ investments in land management are small/minimal due to their limited social capital (Smith 2004; Ngombe et al. 2014).

Generally, this review suggests that farmers with better capacity in terms of landholding, experience, knowledge, social capital, physical capital and financial capital invest more as compared to other farmers with limited capacity in terms of these variables. This suggests that supporting farmers to improve their capacity to invest in SLM is crucial for adoption and sustainability of farmers’ investments in SLM in Ethiopia.

3.3.2 Incentives to invest in SLM practices

The factors that affect farmers’ incentives to invest in SLM are related to those conditions that affect the net/relative return of investments and riskiness of investments in SLM. Most farmers in Ethiopia are sensitive to net/relative return to their labor or financial investments in land. Usually, net/relative returns from labor and finance can be higher in non-farm business (e.g., casual labor, petty trading) relative to investments in long-term SLM practices.

Net return/profitability is one of the most important factors governing investments in land management (Ervin and Ervin 1982). If the costs of land management practices exceed the short-term and the long-term benefits, farmers have no incentive to adopt them (Napier et al. 1998). Net returns of a given investment depend on the yields and input requirements per unit of output and the prices of inputs and outputs. Leaving aside the question of capacity constraints, the better the net return of a potential investment in land management, the greater the probability of a farmers’ investment will be. In general, Ethiopian farmers are sensitive to net returns and implicitly compare the expected costs and benefits and then invest in options that offer highest net returns in terms of either income or reduced risk (Shiferaw et al. 2009). Their decision to invest in land management is affected by the (perceived) profitability of the technology (Kelly et al. 2003; Langyintuo and Dogbe 2005; Crook and Decker 2006). For instance, studies on the adoption and continuous use of stone terrace in Tanzania and Ethiopia revealed that farmers’ investments are highly influenced by the (perceived) profitability of the technology (Tenge et al. 2004; Amsalu and De Graaff 2007; De Graaff et al. 2008). Similarly, a given investment may be profitable, yet not sufficiently attractive relative to alternative farm and non-farm investments to motivate farmers to invest. A number of authors have reported that the availability of off-farm income has a negative impact on farmers’ land management investment (Pender and Kerr 1998; Shiferaw and Holden 1998; Mbaga-Semgalawe and Folmer 2000; Gebremedhin and Swinton 2003; Holden et al. 2004; Tenge et al. 2004; Amsalu and De Graaff 2007). Two common reasons are given in the literature for the negative outcomes. The first reason is that household workers face higher opportunity costs and prefer to allocate family labor into off-farm activities where it fetches higher returns than on-farm land management. The second reason is that off-farm employment often directly overlaps with high season land management activities and reduces the labor available for land management practices.

Another important factor affecting farmers’ incentives to invest in land management is risk. Climatic risk (e.g., rainfall) and risk of losing their property (e.g., land tenure) can affect farmers’ investments in land. The importance of secure and transferable land rights has long been identified as a key element to bring about higher levels of long-term investment (Gebremedhin and Swinton 2003; Deininger and Jin 2006). Most empirical studies have shown that security of tenure is important for long-term investment and positively correlated with long-term land management practices (Shiferaw and Holden 1998; Gebremedhin et al. 1999; Gebremedhin and Swinton 2003; Otsuka et al. 2003; Asrat et al. 2004; Kabubo-Mariara 2007; Nyangena 2008). Moreover, the characteristics of physical capital such as the slope and fertility status of plots affect the farmers’ investments because it determines the profitability of investments in SLM. For example, farmers’ investments in more fertile soils may be profitable as compared to their investments in infertile soils. Farmers invest more in fertile plots than in infertile ones (Bekele and Drake 2003). This is because marginal productivity loss due to erosion from plots with fertile topsoil will be higher than those with less fertile topsoil and expected to give higher return in the short term. Generally, areas with good soil fertility and relatively abundant rainfall may have a good agricultural profit and farmer reinvest this profit in land management (Gebremedhin and Swinton 2003).

3.3.3 External factors/conditioners

External factors affect farmers’ investments in SLM indirectly by influencing their capacities to invest in SLM and the incentives of their investments. External factors common to all households in a particular agro-climatic/policy context include institutional support (provisions of trainings, extension services, and technologies), policies (e.g., land tenure) and access to infrastructure (e.g., road, market) (Reardon and Vosti 1995). These factors could affect farmers’ investments in SLM by either motivating or discouraging farmers’ investments in SLM (Yirga 2007). Most of the factors under this category are beyond the control of farmers, and hence support from governmental and non-governmental institutions is vital for enhancing farmers’ capacities to invest in SLM and their incentives from SLM investments.

The effectiveness of land management depends on how institutions can work together most efficiently to provide technical support to the farmers (Hoffmann et al. 2007). However, lack of transparency, accountability, capacity, access to information and networking are the main features of most institutions in sub-Saharan Africa (Ribot 2003). Most farmers in sub-Saharan Africa have insufficient access to markets because they are producing in remote areas and roads are bad or nonexistence (Bryceson 2002). The quality and quantity of roads affect transaction costs, risk and price fluctuations, and non-farm activities. Transport and communication infrastructure determines the availability of information, access to markets, and costs and returns of investments. Better access can increase the labor and/or capital intensity of investment in land management by increasing output to input price ratios (Binswanger and McIntire 1987; Osbahr et al. 2008). Better access to roads and markets also promote higher income per capita, by providing greater economic opportunities to rural households and in turn investment in land management (Tiffen 2003). Poor infrastructure raises the prices of inputs and reduces the agricultural outputs which further diminish the profitability of the technology (Shiferaw et al. 2009). An increase in the price of agricultural products may make certain land management interventions profitable or attractive to farmers. Accordingly, some studies find a positive relation between the increase in the price of agricultural produce and adoption of land management technologies (Shiferaw and Holden 2000). However, in some cases better infrastructure may increase non-farm opportunities and thus reduce the intensity of land management (Grothmann and Patt 2005).

4 Conclusions and recommendation

This paper reviews and synthesizes past research in order to identify the determinants that affect farmers’ investments in SLM practices/technologies in Ethiopia and thereby facilitate further evidence to evolve thinking and policy prescriptions to enhance adoption. The review has identified several determinants that affect farmers’ investments in SLM practices. Generally, our review and synthesis identified three major factors for the limited investments in SLM by smallholder farmers in Ethiopia. Firstly, farmers’ capacity to invest in SLM is very limited. Secondly, farmers’ incentives from their investments in SLM practices are limited. Thirdly, there are insufficient enabling conditions for motivating farmers to invest in SLM practices/technologies.

Our review and synthesis indicates the need for improving farmers’ capacity to invest in SLM. Different approaches such as provision of credit and training can be used to enhance farmers’ capacities to invest in SLM. When farmers are poor and risk adverse, and SLM investments appear to have only long-term payoffs that are perceived as more uncertain than productivity or income diversification investments, SLM measures may be ranked quite low in the farmers’ priorities. Hence increasing farmers’ incentives to invest in SLM practices should be an important element for SLM in Ethiopia. One of the most important approaches to increase farmers’ incentives to invest in SLM is to reduce risk related to long-term investments in land. Our synthesis has suggested that a proxy variable related to land tenure insecurity reduced farmers’ investments in SLM practices with long-term economic benefits. This suggests the need to create stable and secure land tenure system in the country.

The review and synthesis showed that external factors such as policies, institutional support and infrastructure influenced farmers’ capacities to invest in SLM and their incentives from SLM investments. This suggests there is a need to create enabling conditions to enhance their investment capacities in SLM practices and increase their economic incentives from SLM investments.

References

Adimassu, Z., Kessler, A., & Hengsdijk, H. (2012). Exploring determinants of farmers’ investments in land management in the Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia. Applied Geography, 35, 191–198.

Adimassu, Z., Mekonnen, K., Yirga, C., & Kessler, A. (2014). The effect of soil bunds on runoff, losses of soil and nutrients, and crop yield in the central highlands of Ethiopia. Land Degradation and Development, 25, 554–564.

Admassie, Y. (2000). Twenty years to nowhere: Property rights, land management and conservation in Ethiopia. Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press.

Amsalu, A., & De Graaff, J. (2007). Determinants of adoption and continued use of stone terraces for soil and water conservation in an Ethiopian highland watershed. Ecological Economics, 61, 294–305.

Anley, Y., Bogale, A., & Haile-Gabriel, A. (2007). Adoption decision and use intensity of soil and water conservation measures by smallholder subsistence farmers in Dedo district, Western Ethiopia. Land Degradation and Development, 18, 289–302.

Asrat, P., Belay, K., & Hamito, D. (2004). Determinants of farmers’ willingness to pay for soil conservation practices in the southeastern highlands of Ethiopia. Land Degradation and Development, 15, 423–438.

Bekele, W., & Drake, L. (2003). Soil and water conservation decision behavior of subsistence farmers in the Eastern Highlands of Ethiopia: A case study of the Hunde-Lafto area. Ecological Economics, 46, 437–451.

Benin, S. (2006). Policies and programmes affecting land management practices, input use, and productivity in the highlands of Amhara Region, Ethiopia. In J. Pender, F. Place, & S. Ehui (Eds.), Strategies for sustainable land management in the East African highlands. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Benin, S., & Pender, J. (2001). Impact of land distribution on land management and productivity in the Ethiopian Highlands. Land Degradation and Development, 12, 555–568.

Berhe, W. (1996). Twenty years of soil and water conservation in Ethiopia: A personal overview. Nairobi, Kenya: Regional Soil Conservation Unit/SIDA.

Beshah, T. (2003). Understanding farmers: Explaining soil and water conservation in Konso, Wolaita and Wello, Ethiopia. Doctoral Thesis, Wageningen University, The Netherlands.

Beshir, H. (2014). Economics of soil and water conservation: the case of smallholder farmers in north eastern highlands of Ethiopia. The Experiment, 23(3), 1611–1627.

Bewket, W. (2007). Soil and water conservation intervention with conventional technologies in Northwestern highlands of Ethiopia: Acceptance and adoption by farmers. Land Use Policy, 24, 404–416.

Bewket, W., & Sterk, G. (2002). Farmers’ participation in soil and water conservation activities in the Chemoga watershed, Blue Nile basin, Ethiopia. Land Degradation and Development, 13, 189–200.

Binswanger, H. P., & McIntire, J. (1987). Behavioral and material determinants of production relations in land-abundant tropical agriculture. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 36(1), 73–99.

Birhanu, A., & Meseret, D. (2013). Structural soil and water conservation practices in Farta District, North Western Ethiopia: An investigation on factors influencing continued use. Science, Technology and Arts Research Journal, 2(4), 114–121.

Bryceson, D. F. (2002). The scramble in Africa: Reorienting rural livelihoods. World Development, 30(5), 2002.

Clay, D. C., Reardon, T., & Kangasniemi, J. (1998). ‘Sustainable intensification in the highland tropics: Rwandan farmers’ investments in land conservation and soil fertility. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 46(2), 351–378.

Crook, B. J., & Decker, E. (2006). Factors affecting community-based natural resource use programs in Southern Africa. Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 22(3), 111–133.

De Graaff, J., Amsalu, A., Bodna, F., Kessler, A., Posthumus, H., & Tenge, A. (2008). Factors influencing adoption and continued use of long-term soil and water conservation measures in five developing countries. Applied Geography, 28, 271–280.

Deininger, K., & Jin, S. (2006). Tenure security and land-related investment: Evidence from Ethiopia. European Economic Review, 50, 1245–1277.

Deressa, T. T., Hassan, R. M., Ringler, C., Alemu, T., & Yesuf, M. (2009). Determinants of farmers’ choice of adaptation methods to climate change in the Nile Basin of Ethiopia. Global Environmental Change, 19, 248–255.

Enki, M., Kassa Belay, K., & Dadi, L. (2001). Determinants of adoption of physical soil conservation measures in Central Highlands of Ethiopia the case of three districts of North-Shewa, Agrekon. Agricultural Economics Research, Policy and Practice in Southern Africa, 40(3), 293–315.

Ervin, C. A., & Ervin, D. E. (1982). Factors affecting the use of soil conservation practices: Hypotheses, evidence and policy implications. Land Economics, 58, 277–292.

Featherstone, A. M., & Goodwin, B. K. (1993). Factors influencing a farmer’s decision to invest in long-term conservation improvements. Land Economics, 69, 67–81.

Gebregziabher, G., Rebelo, L.-M., Notenbaert, A., Ergano, K., & Abebe, Y. (2013). Determinants of adoption of rainwater management technologies among farm households in the Nile River Basin. Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute (IWMI). 34 p. (IWMI Research Report 154). doi:10.5337/2013.218.

Gebremariam, G., & Edriss, A. K. (2012). Valuation of soil conservation practices in Adwa Woreda, Ethiopia: A contingent valuation study. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 3(13), 97–107.

Gebremedhin, B., Pender, J., & Tesfay, G. (2003). Community natural resource management: The case of woodlots in Northern Ethiopia. Environment and Development Economics, 8, 129–148.

Gebremedhin, B., & Swinton, S. (2003). Investment in soil conservation in northern Ethiopia: The role of land tenure security and public programs. Agricultural Economics, 29, 69–84.

Gebremedhin, B., Swinton, S. M., & Tilahun, Y. (1999). Effects of stone terraces on crop yields and farm profitability: Results of on-farm research in Tigray, northern Ethiopia. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 54, 568–573.

Grothmann, T., & Patt, A. (2005). Adaptive capacity and human cognition: The process of individual adaptation to climate change. Global Environmental Change, 15(3), 199–213.

Hagos, F., & Holden, S. (2006). Tenure security, resource poverty, public programs, and household plot-level conservation investments in the highlands of northern Ethiopia. Agricultural Economics, 34, 183–196.

Hayes, J., Roth, M., & Zepeda, L. (1997). Tenure security, investment and productivity in Gambian agriculture: A generalized probit analysis. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 79, 369–382.

Heyi, D. D., & Mberengwa, I. (2012). Determinants of farmers’ land management practices: The case of Tole District, South West Shewa Zone, Oromia National Regional State, Ethiopia. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 14(1), 2012.

Hoffmann, V., Probst, K., & Christinck, A. (2007). Farmers and researchers: How can collaborative advantages be created in participatory research and technology development? Agriculture and Human Values, 24, 355–368.

Holden, S., Shiferaw, B., & Pender, J. (2004). Non-farm income, household welfare and sustainable land management in the less favored area in the Ethiopian highlands. Food Policy, 29, 369–392.

Holden, S., & Yohannes, H. (2002). Land redistribution, tenure Insecurity, and intensity of production: A study of farm households in Southern Ethiopia. Land Economics, 78(4), 573–590.

Hurni, H. (1996). Precious earth: From soil and water conservation to sustainable land management (p. 89). Berne: International Soil Conservation (ISC) and Centre for Development and Environment (CDE).

Jumbe, C. B. L., & Angelsen, A. (2007). Forest dependence and participation in CPR management: Empirical evidence from forest co-management in Malawi. Ecological Economics, 62, 661–672.

Kabubo-Mariara, J. (2007). Land conservation and tenure security in Kenya: Boserup’s hypothesis revisited. Ecological Economics, 64, 25–35.

Kassie, M., Pender, J., Yesuf, M., Kohlin, G., Bluffstone, R., & Mulugeta, E. (2008a). Estimating returns to soil conservation adoption in the northern Ethiopian highlands. Agricultural Economics, 38, 213–232.

Kassie, M., Zikhali, P., Manjur, K., & Edwards, S. (2008b). Adoption of organic farming technologies: Evidence from semi-arid regions of Ethiopia. In Working paper in economics, No. 335, University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

Kassie, M., Zikhali, P., Manjur, K., & Edwards, S. (2009). Adoption of sustainable agriculture practices: Evidence from a semi-arid region of Ethiopia. Natural Resources Forum, 33, 189–198.

Kassie, M., Zikhali, P., Pender, J., & Kohlin, G. (2010). The economics of sustainable land management practices in the Ethiopian highlands. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 61(3), 605–627.

Kelly, V., Adesina, A., & Gordon, A. (2003). Expanding access to agricultural inputs in Africa: A review of recent market development experience. Food Policy, 28, 379–404.

Kessler, C. A. (2006). Decisive key-factors influencing farm households’ soil and water conservation investments. Applied Geography, 26, 40–60.

Ketema, M., & Bauer, S. (2012). Determinants of adoption and labour intensity of stone terraces in Eastern Highlands of Ethiopia. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 3(5), 7–17.

Langyintuo, A., & Dogbe, W. (2005). Characterizing the constraints for the adoption of a Callopogonium mucunoides improved fallow in rice production systems in northern Ghana. Agriculture, Ecosystem and Environment, 110, 78–90.

Lapar, M. L. A., & Ehui, S. K. (2004). Factors affecting adoption of dual-purpose forages in the Philippine uplands. Agricultural Systems, 81(2), 95–114.

Liniger, H. P., Studer, R. M., Hauert, C., & Gurtner, M. (2011). Sustainable land management in practice—guidelines and best practices for sub-Saharan Africa. TerrAfrica, World Overview of Conservation Approaches and Technologies (WOCAT) and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Mbaga-Semgalawe, Z., & Folmer, H. (2000). Household adoption behaviour of improved soil conservation: The case of the North Pare and West Usambara Mountains of Tanzania. Land Use Policy, 17(4), 321–336.

Mengstie, F. A. (2009). Assessment of adoption behavior of soil and water conservation practices in the Koga watershed, highlands of Ethiopia. M.Sc. Thesis, Cornell University, p. 62.

Napier, T. L., Thraen, C. S., & Camboni, S. M. (1998). Willingness of land operators to participate in government-sponsored soil erosion control programs. Journal of Rural Studies, 4(4), 339–347.

Ngombe, J., Kalinda, T., Tembo, G., & Kuntashula, E. (2014). Econometric analysis of the factors that affect adoption of conservation farming practices by smallholder farmers in Zambia. Journal of Sustainable Development, 7(4), 124–138.

Nkonya, E., Pender, J., Jagger, P., Sserunkuuma, D., Kaizzi, C. K., & Ssali, H. (2004). Strategies for sustainable land management and poverty reduction in Uganda, Research Report No. 133, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC.

Nkonya, E., Pender, J., Kaizzi, C., Edward, K., & Mugarura, S. (2005). Policy options for increasing crop productivity and reducing soil nutrient depletion and poverty in Uganda. Environment and Production Technology Division Discussion Paper No. 134, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC.

Nowak, P. J. (1987). The adoption of conservation technologies: economic and diffusion explanations. Rural Sociology, 42, 208–220.

Nyangena, W. (2008). Social determinants of soil and water conservation in rural Kenya. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 10, 745–767.

Osbahr, H., Twyman, C., Adger, W. N., & Thomas, D. S. G. (2008). Effective livelihood adaptation to climate change disturbance: Scale dimensions of practice in Mozambique. Geoforum, 39, 1951–1964.

Otsuka, K., Quisumbing, A. R., Payongayong, E., & Aidoo, J. B. (2003). Land tenure and the management of land and trees: The case of customary land tenure areas of Ghana. Environment and Development Economics, 8, 77–104.

Pattanayak, S. K., Mercer, D. E., Sills, E., & Jui-Chen, Y. (2003). Taking stock of agroforestry adoption studies. Agroforestry Systems, 57(3), 173–186.

Pender, J., & Gebremedhin, B. (2006). Land management, crop production and household income in the highlands of Tigray, northern Ethiopia: an econometric analysis. In J. Pender, F. Place, & S. Ehui (Eds.), Strategies for sustainable land management in the East African highlands. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Pender, J., & Gebremedhin, B. (2007). Determinants of agricultural and land management practices and impacts on crop production and household Income in the highlands of Tigray, Ethiopia. Journal of African Economies, 17, 395–450.

Pender, J., Jagger, P., Nkonya, E., & Sserunkuuma, D. (2004). Development pathways and land management in Uganda. World Development, 32(5), 767–792.

Pender, J., & Kerr, M. (1998). Determinants of farmers’ indigenous soil and water conservation investment in semi-arid India. Agricultural Economics, 19, 113–125.

Reardon, T., Crawford, E., Kelly, V., & Diagana, B. (1996). Promoting farm investment for sustainable intensification of African agriculture. Technical Paper No. 26. Department of Economics, Michigan State University.

Reardon, T., & Vosti, S. A. (1995). Links between rural poverty and environment in developing countries: Asset categories and investment poverty. World Development, 23, 1495–1503.

Requier-Desjardins, M., Adhikari, B., & Sperlich, S. (2011). Some notes on the economic assessment of land degradation. Land Degradation and Development, 22, 285–298.

Ribot, J. C. (2003). Democratic decentralization of natural resources: Institutionalizing choice and discretionary power transfer in sub-Saharan Africa. Public Administration and Development, 23, 53–65.

Schmidt, E., & Tadesse, F. (2012). Household and plot level impact of sustainable land and watershed management (SLWM) practices in the Blue Nile. In ESSP II working paper 42, International Food Policy Research Institute.

Sheikh, A. D., Rehman, T., & Yates, C. M. (2003). Logit models for identifying the factors that influence the uptake of new ‘no-tillage’ technologies by farmers in the rice–wheat and the cotton–wheat farming systems of Pakistan’s Punjab. Agricultural Systems, 75(1), 79–95.

Shiferaw, B., & Holden, S. (1998). Resource degradation and adoption of land conservation technologies in the Ethiopian highlands: A case study in Andit Tid, North Shewa. Agricultural Economics, 18(3), 233–247.

Shiferaw, B., & Holden, S. (1999). Soil erosion and smallholders’ conservation decisions in the highlands of Ethiopia. World Development, 27(4), 739–752.

Shiferaw, B., & Holden, S. (2000). Policy instruments for sustainable land management: the case of highland smallholders in Ethiopia. Agricultural Economics, 22, 217–232.

Shiferaw, B., & Holden, S. (2001). Farm-level benefits to investments for mitigating land degradation: empirical evidence from Ethiopia. Environment and Development Economics, 6, 335–358.

Shiferaw, B., Okello, J., & Reddy, R. V. (2009). Adoption and adaptation of natural resource management innovations in smallholder agriculture: Reflections on key lessons and best practices. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 11, 601–619.

Smith, R. E. (2004). Land tenure, fixed investment, and farm productivity: Evidence from Zambia’s Southern Province. World Development, 32(10), 641–1661.

Stroosnijder, L. (2009). Modifying land management in order to improve efficiency of rainwater use in the African highlands. Soil and Tillage Research, 103, 247–256.

Swinton, S. M., & Quiroz, R. (2003). Is poverty to blame for soil, pasture, and forest degradation in Peru Altiplano? World Development, 31, 1903–1919.

Tadesse, M., & Belay, K. (2004). Factors influencing adoption of soil conservation measures in Southern Ethiopia: The case of Gununo area. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics, 105(1), 49–62.

Teklewold, H., Kassie, M., & Shiferaw, B. (2013). Adoption of multiple sustainable agricultural practices in rural Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 64(3), 597–623.

Tenge, A., De Graaff, J., & Hella, J. P. (2004). Social and economic factors affecting the adoption of soil and water conservation in West Usambara highlands, Tanzania. Land Degradation and Development, 15(2), 99–114.

Tesfaye, A., Negatu, W., Brouwer, R., & Van der Zaag, P. (2014). Understanding soil conservation decision of farmers in the Gedeb watershed, Ethiopia. Land Degradation and Development, 25, 71–79.

Teshome, A. (2014). Tenure security and soil conservation investment decisions: Empirical evidence from East Gojam, Ethiopia. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 6(1), 22–32.

Tiffen, M. (2003). Transition in sub-Saharan Africa: Agriculture, urbanization and income growth. World Development, 31(8), 1343–1366.

Tiwari, K. R., Sitaula, B. K., Nyborg, I. L. P., & Paudel, G. S. (2008). Determinants of farmers’ adoption of improved soil conservation technology in a middle mountain watershed of central Nepal. Environmental Management, 42, 210–222.

Wossen, T., Berger, T., Mequaninte, T., & Alamirew, B. (2013). Social network effects on the adoption of sustainable natural resource management practices in Ethiopia. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology, 20(6), 477–483.

Yesuf, M., & Köhlin, G. (2009). Market imperfections and farm technology adoption decisions: A case study from the highlands of Ethiopia. In Working papers in economics No. 403. School of Business, Economics and Law at University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

Yirga, C. (2007). The dynamics of soil degradation and incentives for optimal management in Central Highlands of Ethiopia. Ph.D. thesis. Department of Agricultural Economics, Extension, and Rural Development. University of Pretoria, South Africa, p. 284.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adimassu, Z., Langan, S. & Johnston, R. Understanding determinants of farmers’ investments in sustainable land management practices in Ethiopia: review and synthesis. Environ Dev Sustain 18, 1005–1023 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-015-9683-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-015-9683-5