Abstract

Over the last few years, the concept of online loyalty has been examined extensively in the literature, and it remains a topic of constant inquiry for both academics and marketing managers. The tremendous development of the Internet for both marketing and e-commerce settings, in conjunction with the growing desire of consumers to purchase online, has promoted two main outcomes: (a) increasing numbers of Business-to-Customer companies running businesses online and (b) the development of a variety of different e-loyalty research models. However, current research lacks a systematic review of the literature that provides a general conceptual framework on e-loyalty, which would help managers understand their customers better, take advantage of industry-related factors, and improve their service quality. The present study is an attempt to critically synthesize results from multiple empirical studies on e-loyalty. Our findings illustrate that 62 instruments for measuring e-loyalty–with two or more items—are currently in use, influenced predominantly by Zeithaml et al. (J. Marketing 60(2):31–46, 1996) and Oliver (Satisfaction: a behavioral perspective on the consumer. New York: McGraw Hill, 1997). Additionally, we propose a new general conceptual framework, which leads to e-loyalty dividing antecedents into prepurchase, during-purchase and after-purchase factors, based on the act of purchase. To conclude, a number of managerial implementations are suggested in order to help marketing managers increase their customers’ e-loyalty by making crucial changes in each purchase stage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction: loyalty in the Internet era

The penetration of the Internet in marketing and e-commerce settings has influenced, to a great extent, the entire business world. From the customer’s viewpoint, it has created new and possibly less costly ways of participating in commercial activities [182]. From the business perspective, market globalization, along with the decreasing effectiveness of offline marketing, has motivated organizations to shift their plans to include Internet marketing [120]. Hence, consumers have increasingly favored online shopping [166], gradually leading more Business-to-Customer (B2C) companies to establish an Internet presence in an effort to attract new and maintain existing customers for long-term profitability [203].

Building and maintaining brand loyalty has been a central theme of marketing theory and practice in traditional consumer marketing [71]. For this reason, businesses should be more interested in keeping long-lasting relationships with their customers than in accumulating occasional exchanges [17]. Presently, the notion of brand loyalty has been expanded to include online loyalty (also known as e-loyalty or website loyalty). The online shopping world has completely changed the relationship between customers and retailers. The minimal cost to a customer to switch brands (compared to the high costs for companies to acquire new e-customers) justifies the need for online businesses to create a loyal customer base, as well as to monitor the profitability of each segment in order to avoid unprofitable customer relationships during the initial years of online operation [7, 166, 167]. Moreover, Reichheld et al. [163, 164] and Day [51] have indicated that the notion of e-loyalty is the most important factor affecting online business performance.

E-loyalty is “the customer’s favorable attitude towards an electronic business, resulting in repeat purchasing behaviour” [7]. It encompasses high quality customer support, on-time delivery, compelling product presentations, convenient and reasonably priced shipping and handling, and clear and trustworthy privacy policies [166]. As a result, the study of e-loyalty’s antecedents has become essential [161]; satisfaction, trust, service quality, and perceived value among others are certain precursors.

Consequently, creating customer loyalty and satisfaction is the major objective for online companies to increase profitability and obtain and maintain competitive advantage. To do so, companies need to develop a thorough understanding of the antecedents of loyalty on the World Wide Web [120]. Shankar et al. [181, p. 154] note that “firms need to gain a better understanding of the relationship between satisfaction and loyalty in the online environment to allocate their online marketing efforts between satisfaction initiatives and loyalty programs”. Reichheld and Sasser [165] suggested that increasing a business’s number of loyal customers by 5 % can result in a 30 % to 85 % increase in profitability. However, the identification of factors that might affect e-loyalty has puzzled academic scholars over the last decade [189, 195].

2 Purpose

No problem facing the individual scientist today is more defeating than the effort to cope with the flood of published scientific research, even within one’s own narrow specialty.

Bentley Glass [70, p. 583]

Up to this point, various studies have tried to explain the concepts of loyalty and satisfaction in online markets as well as the potential factors that influence them [37, 154, 197]. However, many online companies fail to cultivate e-loyalty because they are not aware of the mechanisms involved in generating customer loyalty on the Internet [169]. To the best of our knowledge, and despite the importance of e-loyalty for a business’s success in the online market, there is a lack of comprehensive and systematic reviews on e-loyalty that incorporate empirical results from the last decade.

Hence, the purpose of this study is to concentrate all the available empirical literature on e-loyalty as studied in e-commerce settings and to answer the following questions:

-

(1)

What instruments are currently available to assess e-loyalty?

-

(2)

Is there a common definition of e-loyalty? What are considered to be its most widely accepted antecedents?

-

(3)

What are the limitations of current research in the e-loyalty literature?

3 Methodology

3.1 Literature search

The literature review was conducted sourcing the following electronic databases: Web of Science, Scopus, Business Source Premier, ABI Inform, and Google Scholar. Search terms included different combinations of “e-loyalty”, “web loyalty”, “online loyalty”, “web”, “e-commerce”, “intentions”, and “repurchase intentions”. Searches extended until July 2011 with no cut-off date for past studies. Only articles written in English were included. Articles could be from conference proceedings or journals, but only records with available abstracts were included. Dissertations, theses, and other material from the “grey literature” were excluded [170, 208]. We included studies that satisfied the following criteria: (a) They were sampling or experimental surveys and reported quantitative results and (b) They had e-loyalty as a dependent variable in the model the paper tested. Qualitative studies were excluded due to the present review’s interest in instruments used for measuring e-loyalty and their psychometric properties. Methodologically, a critical review of qualitative studies assesses different concepts (e.g., sampling, coding, etc.) than one of quantitative studies, while qualitative studies are predominantly theory building and not theory testing essays [53]. Our aim is to offer an evidence-based approach for all research questions based on tested theories.

Our search method also resulted in papers that investigated loyalty in mobile commerce (m-commerce) settings, loyalty towards social networking sites and online gaming platforms, and certain attitudes towards websites. These papers were excluded, since papers studying loyalty behaviors in e-commerce and marketing settings were the primary interest.

The next step in the data collection process involved a type of snowball sampling technique: the references listed in the obtained studies were used to locate additional studies [80, 154]. Also, major review papers were screened for references to ensure that all suitable papers were included. Our search method resulted in 3,128 academic papers, which were downsampled to 217 according to the inclusion criteria. The screening procedure is shown in Fig. 1.

3.2 Academic papers

The papers included in our sample came mainly from the marketing and e-commerce settings of various industries (book selling websites, travel websites, general retailing websites, etc.). The total sample size, taken from all studies, was 103,858 people. The first papers discussing some aspect of e-commerce loyalty appeared in 1998 and, following a steady increase from 2003 to 2008, articles peaked at 120 to 140 in 2009 and 2010 (Fig. 2). Many papers from 2011 were still in publication, but given the present review’s time limit and the fact that the number of papers up until that point equaled about half of 2010’s total number, a figure of about 140 is expected for 2011. This shows the ongoing interest of academic researchers for studying e-loyalty in e-commerce settings. From the Web of Science sample of papers on e-loyalty (590), most papers published are authored by researchers from the USA (31.4 %), Taiwan (16.1 %), China (14.3 %), South Korea (6.1 %), and the UK (8.2 %); the remaining studies are from various other European, Asian, and American countries.

3.3 Synthesis of the literature

Several steps were followed in the process of synthesizing the concepts presented in various studies and the impact they have had on e-commerce literature [234]. A table of all studies was created, noting the following information for each study: authors and year of publication, main area of study, scope of the paper, sample size, loyalty instrument used, number of items and Likert points, the instrument’s reliability, and results of its confirmatory factor analysis. For each study, we noted the other dimensions/concepts measured by authors and results of their hypotheses concerning e-loyalty. Finally, the number of citations each paper received from Google Scholar and an impact ratio (citations in Google Scholar/year) were included to assess the relative impact of each paper [37]. A detailed list of all papers identified is included in the Supplementary Appendix (Table A2). As a next step, we identified the instruments used for studying loyalty in e-commerce settings and constructed a unifying model of all of the studies’ results.

4 Critical assessment of e-loyalty instruments

4.1 Overview of e-loyalty instruments

A useful starting point in assessing the e-loyalty literature is identifying general trends across existing e-loyalty instruments. These questionnaires consist of a series of questions for the purpose of gathering information from respondents. Our search process resulted in noting 62 e-loyalty instruments with a number of items ranging from two to 16 (either on 5-point or 7-point Likert scales) and eight one-item instruments, outlined in Tables 1, 2, and 3, mentioning the information for each paper gathered from the literature search. Out of the 62 instruments, 23 were self-defined by authors and 39 were adaptations from previous loyalty or e-loyalty instruments.

The instruments are listed in chronological order in Tables 1, 2, and 3 with the instrument by Lynch et al. [123] being the earliest one-item instrument; that of Devaraj et al. [54] is the earliest self-defined instrument and Gefen and Straub’s [69] is the earliest adapted loyalty instrument. A certain number of the instruments are used more frequently than others, but most of them are unknown (as indicated by the small number of citations). A possible explanation for this is that authors might find many similarities between the least-cited and most-cited instruments, thus selecting the more popular ones even when they consider parts of them irrelevant. The surveys were created by researchers in a variety of disciplines, including e-commerce, business, marketing, and information science, suggesting that e-loyalty is a complex field that has drawn attention from multiple disciplines. The number of items per instrument ranged from one to 16. More than 100 factors or dimensions were measured, depending on the hypotheses made by the authors in their studies, and more than 33 factors were found to have some significant association with e-loyalty.

The impact ratio (IR) of each paper was also examined; it ranged from 0 [128] to 95.5 [108], with mean IR=4.1. The impact ratio controls for year so it clearly depicts the impact of each instrument independent of its year of publication [37]. According to their IR, the most important papers describing a new e-loyalty instrument are those by (a) Koufaris [108] (IR=95.5) and Shankar et al. [181] (IR=50.6) among the one-item instruments; (b) Yen and Gwinner [225] (IR=10.4) and Vatanasombut et al. [206] (IR=9.3) among the self-defined instruments; and (c) Srinivasan et al. [189] (instrument use by subsequent authors: 40 times) and Gefen and Straub [69] (instrument use by subsequent authors: 16 times) among the adapted instruments. From the adapted instruments, the study by Zeithaml et al. [233] appears to have significantly influenced e-loyalty literature, as 49 authors have adapted this instrument to measure e-loyalty. Second comes Oliver [143–145], whose customer satisfaction theories have been used as a basis to form an e-loyalty instrument in 11 studies.

4.2 Starting points for e-loyalty instruments: Zeithaml et al. [233] and Oliver [143, 144]

It is worth analyzing the properties of the instruments with the greatest conceptual influence, namely those of Zeithaml et al. [233] and Oliver [143, 144]. Zeithaml et al. [233] offered a conceptual model of the impact of service quality on particular behaviors that signaled whether customers remain with or defect from a company (loyalty or disloyalty). Their methodological approach resulted in a configuration of five items for loyalty, which had high internal consistency (0.93 to 0.94 across companies). These loyalty items stressed the importance of recommending a company to others, through positive words, advice, and friendly encouragement, or through repetitive behaviors of continuing to patronize a business over the next years and considering it a first choice for buying. Zeithaml et al. [233] considered these loyalty concepts more as behavioral intentions than active behaviors, introducing as well elements of word of mouth as a proxy for loyalty, since recommendations were a very important part of their instrument. Their analysis signified the crucial role of satisfaction as an antecedent of loyalty, as satisfaction is based on certain expectations for service quality that, when met, produce satisfaction and, eventually, loyalty.

Oliver [143–145] provides a detailed approach that considers satisfaction a variable that crucially affects loyalty, with satisfaction being just one antecedent of loyalty among others. He provides a series of six scenarios on the relationship of satisfaction to loyalty, which is not analyzed here. This framework provides practitioners with means to develop loyalty through satisfaction. In the development of loyalty, Oliver noted five phases, namely cognitions, affections, intentions (conative phase), actions, and fortitude. This approach emphasizes the customer’s personal feelings and emotions rather than word-of-mouth practices, as suggested by Zeithaml [233]. Intentions are also present but actions and emotions are a paramount element of Oliver’s loyalty. Oliver tries to limit the definition of loyalty to the customer’s immediate universe, without extending it to include the consequences of loyalty, such as word of mouth. The advantage of Oliver’s axiomatic conceptions is that they distinguish loyalty from consequential proxies of loyalty; this distinction provides opportunities for formation of loyalty instruments as well as identifying antecedents or consequences of loyalty in a multitude of situations.Footnote 1

In conclusion, there are various e-loyalty instruments in the literature, including some that are never used and some that appear quite frequently across different works. Moreover, the number of items varied with each instrument, even in those adapted from the same source. It would be useful for future studies to include several items with either 5- or 7-point Likert scales. One reason for this is that an instrument with five to 10 items usually produces acceptable reliability, making its use appropriate for a research study or a commercial setting. Finally, there is clearly a need to create a standardized e-loyalty instrument in order to ensure comparability among various studies.

5 Definitions of e-loyalty

Customers’ online loyalty has been discussed extensively in various scientific papers. The present review found that researchers often use concepts similar to e-loyalty, such as continuance intention [19, 20, 107], re-purchase intention [116, 123, 153, 202], re-patronize intention [106], commitment [76], stickiness [102, 119], and word of mouth [43, 103]. All of these approaches are measured by various items that depict the concepts approached. For example, if repurchase intention was stressed as loyalty behaviour, then the researcher would most probably ask, “How many times have you bought from this website since your first purchase?” On the other hand, if the author was interested in word of mouth as a loyalty proxy, the question asked might appear as “Would you recommend this website to others?” Thus, loyalty seems to have many aspects that may be relevant to its study.

According to Oh and Parks [142], there are three approaches towards loyalty: behavioral, attitudinal, and integrated. The first examines customers’ tendency to repeat and continue their past purchases, while the second refers to the customers’ psychological involvement, favoritism, and sense of goodwill towards a particular product or service [31]. The integrated approach is a combination of both behavioral and attitudinal approaches, with the aim of creating a new concept of loyalty. There is a general belief that the examination of loyalty must be based on both behavioral and attitudinal features [112, 177].

Oliver’s [143] definition comprises both of these types of features: he presented a loyalty framework based on a cognition-affect-conation-action historical pattern. According to Oliver [143, 145], loyalty is “a deeply held commitment to rebuy or repatronize a preferred product/service consistently in the future, thereby causing repetitive same-brand or same brand-set purchasing, despite situational influences and marketing efforts having the potential to cause switching behaviour.” Another conceptualization of loyalty used by e-loyalty researchers is that of Neal [138, p. 21], who defines customer loyalty as “the proportion of times a purchaser chooses the same product or service in a specific category compared to the total number of purchases made by the purchaser in that category, under the condition that other acceptable products or services are conveniently available in that category.”

The existence of various definitions denotes that loyalty remains a research topic under constant inquiry and their elements provide an opportunity for researchers and practitioners to grasp the multiple aspects attributed to loyalty. E-loyalty draws its definitions from classical customer behaviour theory, but can any approach be particularly preferred in an e-commerce setting? For the marketing researcher/practitioner, it seems more general to accept an integrated approach, which combines both behavioral and attitudinal aspects of loyalty. This approach provides the conceptual basis for specific e-loyalty instrument formation, both in real and research settings. This definition of e-loyalty also coincides with the fact that many authors base their studies on Oliver’s approach to loyalty (discussed in the previous section), which is very close to an integrated one. Definitions that deal with loyalty based on word-of-mouth concepts risk the danger of lacking specificity, since word of mouth is allegedly a consequence of loyalty and satisfaction [143–145], rather than a proxy of them.

6 Conceptual framework for e-loyalty

E-loyalty instruments have taken into account many factors that could be loyalty’s antecedent in the e-commerce environment. In the present section, an attempt to relate all factors in a conceptual framework is made. We will argue that antecedent factors of e-loyalty can be broadly categorized into three categories centred on purchase, including pre-purchase, during-purchase and after-purchase factors. The act of purchase has been suggested to comprise a series of activities:

As a consumer, you (1) recognize that you have a need to satisfy; (2) search for alternatives that might satisfy the need; (3) evaluate the alternatives and choose the best one; (4) purchase and use the chosen alternative; (5) evaluate how successfully your need has been satisfied; (6) provide feedback about your evaluation to others; and (7) end the consumer purchase process [216, p. 35].

Thus purchases are not isolated, one-time events that occur automatically [26], but involve a stepped process, based on gradual decision-making or simply situational/habitual conditions (e.g., necessity, cultural situations, recommendations, etc.) [147]. The purchase process establishes the need for a framework centred on it, since if sellers can influence this process (through certain factors), they will be able to convince buyers to make the desired purchase.

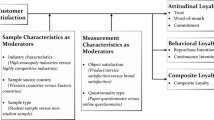

For e-loyalty, all studies included in the present review have demonstrated some association with pre-purchase, during-purchase, and after-purchase factors. Thus, it is valid to consider a theoretical model under which these are combined and can lead to e-loyalty. The framework is shown in Fig. 3, while references to each factor can be found in Table A1 of the Supplementary Appendix.Footnote 2

The model is read from left to right: Pre-purchase factors are considered as initial factors that are to some degree interrelated and directly affect during-purchase factors, but can’t directly affect loyalty. During-purchase factors are in general related attitudinal concepts that can affect loyalty both and through after-purchase factors. Finally, after-purchase factors are behavioral and attitudinal concepts that are directly related to e-loyalty, and their alteration can have pervasive effects on e-loyalty.

6.1 Pre-purchase factors

This first group of variables consists of two major sub-categories. First, there are general external factors that take into account the continuously changing views of the online market. These include the competitors’ attitudes and reputations (labeled e-competitors’ attitude and e-reputation, respectively). Second, there are customers’ specific and unchangeable characteristics, which include customer characteristics variables and PC knowledge variables. All of the pre-purchase factors have been studied extensively by researches who endeavor to understand e-loyalty and its determinants. As a result, these variables will be presented first.

6.1.1 E-competitors’ attitudes

In every industry, the knowledge of one’s competitors is crucial, and applying Porter’s Five Forces in marketing settings is imperative for defining strategies to cope with this issue.Footnote 3 Switching costs, switching barriers, and price variations are variables that involve competitors’ knowledge; as such, many authors have examined them as ancillary antecedents of e-loyalty, as they might not directly lead to loyalty but rather affect service quality dimensions, which are discussed below. Fuentes-Blasco et al. [65] examined the moderating effect of switching costs on e-loyalty in a sample of 191 online customers and noted that the higher the website switching costs, the stronger the link between perceived value and e-loyalty. Yen [226, 227] also investigated the effect of switching costs on e-loyalty in two different samples of online shopping customers and noted a positive direct association between perceived value and e-loyalty in both samples [path coefficient \(\beta_{\mathrm{during\ retention\ of\ the\ customer}}=0.55\), p<0.01 from Yen [227]]. Balabanis et al. [11] and Tsai et al. [202] describe similar results for switching barriers.

Price, however, seems to affect e-loyalty in an unclear way, despite the many studies that have discussed it as a possible determinant of e-loyalty [39, 54, 68, 107]. For instance, Jiang and Rosenbloom [95] examined the role of price on customer retention and found a positive direct, albeit weak, association between favorable price perceptions and customer intention to return (path coefficient=0.193, p<0.05). Swaid and Wigand [194] considered price an important internal parameter of loyalty behaviors and defined an aspect of it, which they named “price tolerance”. They noted a positive association of price tolerance with certain service quality factors. Nevertheless, the study by Wang et al. [211] on 491 Chinese online customers uncovered a non-significant negative association of e-loyalty with price, contradicting the previous findings. They explained this observation as a consequence of the infant stage of Chinese B2C e-commerce development, since most consumers give greater importance to service quality dimensions than price.

6.1.2 E-reputation

Reputation is generally regarded as the current assessment of a firm’s desirability, as seen by some external person or group of people [109, 191]. In classical strategic management, reputation sustains competitive advantages [86, 215], so e-reputation is closely connected to e-competitors’ attitudes [72]. For online websites, reputation either stems from the website itself or from certain offline corporate activities, if existent. Caruana and Ewing [28, p. 1104] argue for the significance of corporate reputation for websites and note that “many customers have difficulty remembering even prominent websites and are reluctant to pay for products from online retailers they know little about. Thus, a strong corporate reputation can be a major asset to online retailers.” Their hypothesis was confirmed by noting a strong positive association leading to e-loyalty from their own survey. Goode and Harris [72] examined the role of online reputation with regard to e-loyalty and found a positive direct path coefficient (0.37, p<0.001) from online reputation to behavioral intentions for an e-tailer website. Yee and Faziharudean [224] reported comparable results from the Malaysian online banking sector. Finally, rather than directly affecting loyalty, Yang and Jing [222] suggest that reputation leads to loyalty through the development of trust.

6.1.3 Customer characteristics

Customer characteristics comprise a type of rather constant variables in a customer’s profile, in the sense that a commercial agent cannot alter them and simply takes them into account. Thus it is reasonable to consider them as pre-purchase factors that affect the purchase process but are distinctly different from the two previous factors, which are centred more on strategic variables than consumer characteristics. The literature review revealed many studies examining the effect of demographic variables on e-loyalty [115, 131, 171, 203, 237]. Demographics broadly include the type of online buyer and his or her personal attitude, online buying habits, and general demographic characteristics, such as gender, age, income, and education. Computer knowledge has also been studied as an antecedent of e-loyalty, but due to the particularity of the e-commerce environment—which requires computer skills—this is discussed as a separate pre-purchase factor below.

Kim and Kim [104] examined the effect of certain demographic variables (gender, age, income, education, and number of children) on online purchase intentions and showed that gender, income, and number of children had significant direct effects, while education had an indirect effect. The positive influence of a customer’s age and gender on satisfaction and loyalty was also supported by O’Cass and Carlson [141], but their results were moderate and non-significant. Román [173] noted the moderating effects of customers’ demographics (age, education, gender) on loyalty intentions in his sample online customers. Finally, from Saudi Arabia, Abdul-Muhmin et al. [2] found that the adoption of B2C e-commerce is higher among older, highly educated, high-income respondents [1, 57]. Many other studies reported demographic associations with customer behaviour concepts [82, 171, 188], but as they didn’t fulfil the present review’s inclusion criteria they are not described here.

6.1.4 PC knowledge

Highly connected to demographic factors are customers’ computer and Internet literacy, knowledge, and skills (e.g., the described gender gap in computer/Internet Use) [58, 92, 159, 183]. These skills are necessary for carrying out online purchases and could increase satisfaction and/or loyalty. Studies measuring computer skills took into account customers’ Internet and online buying experience along with knowledge and skills. According to Dinev and Hart [55], computer literacy is defined as the ability to use an Internet-connected computer and Internet applications to accomplish practical tasks. As stated by Taylor and Strutton [197], consumers with high levels of positive feelings about computers and online shopping have higher levels of computer affinity than consumers who “can do without their computer for several days and would not miss them if they were broken” [190, p. 139].

For instance, Zhang et al. [235] investigated the factors that affect e-service satisfaction by using a sample of 704 university students. Their results showed a direct influence of the user’s computer skills and Internet experiences on his or her intention to use. Furthermore, Lee et al. [110] studied the influence of computer self-efficiency and computer anxiety on repurchase intention in a sample 274 online buyers. Their results indicated that the effect of website information satisfaction on efficiency is stronger for those with lower computer self-efficacy than for those with higher computer self-efficacy.

6.2 During-purchase factors

Moving on to factors affecting e-loyalty during purchase, web service quality and customer pleasure/enjoyment appear to be very important (Fig. 3). In the present model, they have been labeled as Web-ServQual and Customer e-Pleasure. These factors are asserted to have an interrelation, since e-pleasure can be affected by quality dimensions [47]. Pre-purchase factors, including e-competitors’ attitude and e-reputation, at least partially define service quality [15], since the force of competition can cause differentiation strategies for service quality to give competitive advantage in an industry [158]. Customer e-pleasure, on the contrary, arguably depends on customers’ characteristics or computer literacy, as psychological emotions are largely dependent on personal characteristics [27]. Thus, taking into account the associations noted in the literature, Web-ServQual includes website design, assurance, secure communications, usability, shopping process value, website brand, online atmosphere, information quality, and product assortment [137]. Customer e-pleasure includes shopping enjoyment and perceived ease of use.

6.2.1 Web-ServQual

Web-ServQual comprises many similar concepts that can lead to loyalty while the leading paths can vary (Fig. 3). It draws its dimensions from classical service quality models, but due to online settings there are additional factors to take into account [15, 234]. Web-ServQual can be defined as the extent to which a website facilitates efficient and effective shopping, purchasing, and delivery of products and service [234]. A range of academic articles from the present critical review found a positive direct or indirect—through satisfaction or trust—association between service quality dimensions and customer loyalty, with website design and associated usability factors being the most frequent features reported [28, 72, 97, 184, 218]. This association also depends on the sample examined, since website design, for instance, might not play a prominent role in affecting loyalty behaviors in novice e-commerce markets (e.g., in China, see Wang et al. [211]). The associated concepts of assurance, security on online websites, and privacy concerns are also very important variables for customers and are important components of Internet marketing strategies [197].

Regarding links with loyalty, Semeijn et al.’s [180] survey of 150 online customers, among others, resulted in a direct association between assurance and loyalty. Swaid and Wigand [194] found that assurance leads to loyalty through an indirect path, affecting initial price tolerance reliability. Finally, online atmosphere has also been advocated as an antecedent of e-loyalty, e.g., in the study of Verhagen and van Dolen [207], who found a direct positive link from online atmosphere to online purchase intentions.

Thus, web service quality can affect loyalty directly or through other factors. The direct effect of service quality on loyalty has been noted as early as Parasuraman’s original studies on service quality [150, 151]. Customers have expectations for the service quality they receive and if the service performance exceeds their expectations, they become satisfied and then loyal [44, 45]. In addition, when their expectations are surpassed, their attitudes and intentions towards rebuying also increase, thus effecting loyalty directly [233]. The link, however, of service quality with loyalty might be weaker than that with satisfaction [44, 45].

6.2.2 Customer e-pleasure

Pleasure is thought to be a feeling of enjoyment and entertainment, contrasted with things done out of necessity [176]. For e-commerce, customer e-pleasure includes shopping enjoyment and perceived ease of use, concepts linked together with their common roots in enjoyment and lack of uneasiness [41]. These attitudes and emotions are closely related to service quality as a during-purchase factor, because if customers’ expectations for quality are met and surpassed, an immediate reaction of pleasure occurs during the purchase process [46, 47]. Enjoyment as an emotion is dependent on demographic characteristics. In traditional commercial settings, Hart et al. [81] conducted a survey with a sample of 536 customers and found that shopping experience enjoyment has a significant positive influence upon customers’ repatronage intentions. Their results showed that men have a stronger relationship of enjoyment with repatronage than women. As an attitude and emotion, pleasure strongly affects post-purchase factors. In online shopping, Chiu et al.’s research [42], among many other similar studies [24, 25, 46, 47, 108, 217, 221], showed that perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and enjoyment are significant positive predictors of customers’ repurchase intentions. Thus, pleasure can conceivably be thought of as an antecedent of loyalty.

6.3 After-purchase factors

After-purchase factors essentially include those attitudes and perceptions that follow the purchase of a certain product from an online vendor. These involve trust, satisfaction, perceived value, and convenience motivation (Fig. 3). Many authors have reported these four factors as leading directly to e-loyalty, stressing the importance of these attitudinal factors in developing loyal behaviour [209, 214]. During-purchase factors previously described have been reported as affecting these factors [113], so direct links between Web-ServQual and Customer e-Pleasure and after-purchase factors have been added, explaining these associations.

6.3.1 E-satisfaction

Satisfaction is considered to be the most discussed factor in the literature that leads to e-loyalty [37, 197]. Customers become satisfied after they evaluate the quality of their purchase—as defined in the during-purchase stage—and their experience from a particular online purchase [197, 234]. According to Oliver [143, 145], satisfaction is defined as “the summary psychological state resulting when the emotion surrounding disconfirmed expectations is coupled with a consumer’s prior feeling about the customer experience.” Extending this definition, e-satisfaction can be considered to be “the contentment of the customer with respect to his/her prior purchasing experience with a given electronic commerce firm” [7]. In the present literature, Chang et al. [31, p. 427] defined customers’ satisfaction as “the psychological reaction of the customer with respect to his or her prior experience with the comparison between expected and perceived performance.” The noteworthy findings of Fournier and Mick [64] showed that satisfaction is an active and dynamic process with a strong social dimension, integrating meaning and emotion as well as contextual factors.

The positive relationship between satisfaction and e-loyalty has been investigated by a large number of studies [4, 7, 16, 75, 98, 122]. Almost all of these studies found a significant positive link between loyalty and satisfaction, which is frequently very strong. A frequent finding is that satisfaction is positively related to loyalty, with the effect moderated by inertia, convenience motivation, and purchase size [7, 61]. These observations have been constant over various countries and cultures. However, other studies who have found weaker associations between satisfaction and loyalty [48, 198]. Dai et al. [48] observed that satisfaction had a weak impact on customer loyalty (β=0.43, p<0.10), but was significantly associated with word-of-mouth communication (β=0.20, p<0.01).

6.3.2 E-trust

Trust is another significant factor affecting a customer’s intention to purchase or repurchase from the same online vendor [129, 185]. The majority of scientific papers from the fields of advertising, marketing, or e-commerce have established a positive and direct relationship between trust and e-loyalty [214]. Similar concepts in use include perceived risk, benevolence belief, and reliability [113]. Some marketing authors distinguish between trust, trusting beliefs, and trusting behaviors. Some argue that trusting beliefs are a necessary but not sufficient condition for the existence of trust, given that trusting beliefs do not always lead to trusting intentions [18, 178]. However, Morgan and Hunt [134] state that trusting beliefs are valid measures of trust, which they define as the “confidence in the exchange partner’s reliability and integrity”. Also, as noted by Doney and Cannon [56], trust is “the perceived credibility and benevolence of a target.” In the e-loyalty literature, Gefen [67, p. 30] has defined trust as “the willingness to make oneself vulnerable to actions taken by the trusted party based on the feelings of confidence or assurance.”

Many e-commerce studies have shown a positive association between e-trust and e-loyalty [8, 40, 61, 63, 122]. For example, Lee et al. [111], in a sample of 289 online customers, identified the key design factors for customer loyalty, and they found a strong impact of trust on customer loyalty (path coefficient=0.781, p<0.01). Also, Gefen [67] investigated the influence of service quality on trust and loyalty, and the findings again showed a similar positive direct relationship between trust and loyalty.

However, some researchers have found slight or even no association between trust and loyalty. For instance, Taylor and Hunter [198] investigated the antecedents of satisfaction, brand attitude, and loyalty within the B2B e-Customer Relationship Management (e-CRM) industry in a sample of 244 customers, and they found that trust does not lead to loyalty. Similarly, Herington and Weaven [83] and Jin et al. [99] found no direct or significant link with loyalty. The reasons for this lack of association could be the different approaches used regarding trust, as many consider trust to be the credibility of services or reputation or even whether a customer trusts the corporation in general. Also, the customer’s experience with online shopping affects the level of trust, illustrating that trust is a complex concept and demands caution when being studying.

Ribbink et al. [169] investigated the effects of trust, quality, and satisfaction on loyalty in a sample of 184 online book and CD customers. They concluded that e-trust leads less to e-loyalty than to satisfaction, which may imply that trust is not a major contributor to loyalty in the online environment [60]. Interestingly, Lynch et al. [123] found that the impact of trust on e-loyalty varies across regions of the world and across different product categories.

6.3.3 Perceived value

In marketing literature, the notion of perceived value has been extensively examined as an antecedent and mediator of e-loyalty. Perceived value has been examined through similar concepts such as perceived usefulness, benefits, and usability. Zeithaml [232, p. 14] defines value as “the consumer’s overall assessment of the utility of a product based on perceptions of what is received and what is given.” Almost concurrently, Oliver and DeSarbo [146] defined perceived value as the ratio of consumer’s outcome/input to that of the service provider’s outcome/input. They primarily stressed the root of perceived value in equity theory, which refers to the customer evaluation of what is fair, right, or deserved for the perceived cost of the offering [22]. In the present literature, the dominant definition of perceived value is similar to that of Zeithaml [232].

Perceived value contributes to loyalty towards an e-business by reducing an individual’s need to seek alternative service providers [31]. Characteristically, when customers feel that they are not getting the best value for their money, they will begin searching for alternatives, which means that their loyalty declines dramatically.

The association between perceived value and customers’ loyalty/intention to purchase or repurchase has been proven to be positive in many studies [48, 212, 213, 223]. Luarn and Lin [122] investigated the main antecedent influences on loyalty for the e-service context in a sample of 180 customers and found that perceived value is associated with loyalty both positively and directly (β=0.230, p<0.001). Also, Chiou [40] examined the antecedents of customers’ loyalty towards Internet Service Providers, and they similarly concluded that perceived value was linked directly and positively with e-loyalty (β=0.67, p<0.05). Moreover, Koufaris [108] measured the intention of 280 online customers to return to a specific web-based store, and he concluded that the perceived usefulness of an online store is associated positively and directly with the intention to return. A recent meta-analysis verified this association as well [197].

6.3.4 Convenience motivation

Convenience motivation is difficult to conceptualize, as it depends on customers’ motivations, which vary widely. Online customers are considered to be driven by a need for convenience as opposed to gathering information and saving money [7, 94]. Convenience motivation has been discussed broadly in marketing and e-commerce literature as it is regarded as a contributing factor that leads to their growth [174]. It can lead to loyalty either directly or indirectly. Anderson and Srinivasan [7] considered the mediating role of convenience motivation on loyalty. The parameter estimate for the main effect of convenience motivation on e-loyalty was insignificant, but the parameter estimate for the interaction aspect of e-satisfaction with convenience motivation proved significant (p<0.05). This confirmed the hypothesis that convenience motivation does indeed positively moderate the impact of e-satisfaction on e-loyalty. Wang et al. [211] measured the dimension of convenience in their model, and they found that convenience is directly and positively associated with loyalty (path coefficient=0.394, p<0.05). They suggested that retailers can take advantage of the customization and contact interactivity in order to enhance customers’ convenience and satisfaction, which will drive the user to visit the site again in the future.

7 Conclusion

This is the first systematic critical review of the e-loyalty literature comprising a large number of sources based on quantitative analyses. Concerning the first research question on available e-loyalty instruments, there appears to be no consensus on the process of measurement, with about 60 instruments currently in use. There is, however, a dominant influence from two particular sources [143, 233], thus showing at least a common theoretical background. Another issue that surfaced is that authors studied e-loyalty under a different perspective, with some focusing on behavioral aspects, some on attitudinal, some on integrated approaches and some on consequences of loyalty such as word-of-mouth advertising and recommendations. This was also the case in the definition of e-loyalty, discussed below. Nevertheless, one important contribution that should be attempted by e-commerce researchers is to standardize a common instrument to measure loyalty, in a manner similar to that followed by the American Psychiatric Society, which has created the Diagnostic and Statistic Manual for Mental Disorders. The importance for this common measure of loyalty would be underscored by the ability to compare studies more reliably and create convenience in qualitative or quantitative synthesis of the literature. This instrument should not be limited to a few items for the sake of brevity, but it should be concise, accurate, diverse, accessible, and adjustable for multiple settings and cultures. Accredited international or national marketing professional bodies could attempt this.

Regarding the second research question of the definition of e-loyalty, there are various approaches to this (behavioral, attitudinal, integrated). In terms of generality, a more appropriate definition is an integrated one, which comprises both attitudinal and behavioral aspects. This definition can provide a reasonable basis for a succinct e-loyalty instrument, which is necessary for the suggested standardization. The antecedents of e-loyalty were structured in a purchase-centred framework and categorized into pre-purchase, during-purchase and after-purchase factors. Each category contains from two to four factors, which comprise multiple similar concepts from the literature. This is the first evidence-based unifying approach in e-loyalty literature that creates a classification of customer behaviour concepts in e-commerce. The original point of the present framework compared to existing models is that it is categorized around the concept of purchase, which is theorized as a process and not a one-time event. Existing theories have focused on the analysis of online consumer behaviour around e-service quality [15, 234] or e-commerce in general [113, 139, 214], offering important classifications but neglecting to signify the importance of the ultimate consumer action [9], which is loyalty behaviour [145]. This new approach has immediate managerial implications, discussed below.

This approach first stresses the necessity of considering the role of pre-purchase customer and industry characteristics in the development of loyalty. A very common feature in existing models is to emphasize during- and after-purchase characteristics (e.g., service quality, satisfaction, perceived value), lacking the investigation of customer or industry characteristics; these are frequently considered as constants, which might not explain much of e-loyalty’s variability. Next, this new necessity is extended to all factors around the purchase process by links intertwining them, which signify that factors of one category have certain antecedents, whose lack of description leads to an incomplete model of e-loyalty. Thus, only simultaneous research of factors from each category can give the opportunity to approach a model, which explains the majority of variation in e-loyalty.

Finally, regarding the third research question, on limitations of the existing research, these were mentioned above: a standard definition followed by a standardized instrument for e-loyalty does not currently exist, leading to various interpretations of different models. Moreover, authors’ models appear to lack factors from all categories, thus inherently decreasing the possibility of giving a comprehensive model for e-loyalty. Methodological limitations of the studies in the present review include the possible presence of confirmation bias, which is a tendency to favor information that confirms authors’ beliefs or hypotheses [125, 140]. This can be indicated by the fact that the majority of studies have been strongly influenced by several few sources, which appear to be cited repeatedly. A final methodological limitation concerns the lack of reporting or performing confirmatory factor analysis in certain studies’ models (n=88), thus not assessing the models measurement fit. These limitations could affect the conclusions of the present systematic review, something that readers have to take into account.

This framework has certain progressive qualities that could influence managerial practice and strategy. First, pre-purchase factors are identified as relatively stable; thus, managers cannot tackle them immediately, and their alteration should be included in a long-term strategy. The optimal way to influence these factors is to obtain a deep knowledge of them. For example, extensive market and industry research will create a solid body of knowledge on customer characteristics and industry status. In this set of factors, the only aspect that can be altered is e-reputation. The corporation itself creates this, but it requires time and effort from the staff. Nevertheless, managing to influence these factors can assist companies in dealing with competition or even with threat of new entrances.

The second set of factors influencing e-loyalty is more easily altered by managers, as service quality and customer pleasure can be readily confronted by them [238, 239]. In an earlier review on web service quality, Zeithaml et al. [234] quoted Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon.com,Footnote 4 who stressed the importance of focusing an Internet company’s resources on providing a good online experience (i.e., good service quality). Customer pleasure can also be improved, although it has some dependence on each customer’s personality and characteristics. Finally, after-purchase factors are, in a way, an image of the efforts of the online company to attract the customer. If the company has created successful during-purchase factors, it will create satisfaction, trust, a sense of perceived value, and convenience. Together, these will lead to e-loyalty.

Notes

Researchers have used one or more concepts to express most factors. These have been included in the boxes under the main factor name. References to each concept are provided in the Supplementary Appendix and can be used for the specific definition of each concept.

Porter’s Five Forces model draws upon industrial organization economics to derive five forces that determine competitive intensity. They include three forces from ‘horizontal’ competition: threat of substitute products, threat of established rivals, and threat of new entrants; and two forces from ‘vertical’ competition: bargaining power of suppliers and bargaining power of customers [157, 187]. His models have been extended to the online commercial environment as well [158].

Over the Internet, word of mouth has a far wider reach. In the offline world, 30 % of a company’s resources are spent providing a good customer experience and 70 % goes to marketing. But online, he says, 70 % should be devoted to creating a great customer experience and 30 % should be spent “shouting” about it. Jeff Bezos, Amazon.com [192].

References

Abdul-Muhmin, A. G. (2011). Repeat purchase intentions in online shopping: the role of satisfaction, attitude, and online retailers’ performance. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 23(1), 5–20. doi:10.1080/08961530.2011.524571.

Abdul-Muhmin, A. G., & Al-Abdali, O. (2004). Adoption of online purchase by consumers in Saudi Arabia: an exploratory study. Paper presented at the 2nd Conference on Administrative Sciences, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, 19–21 April, 2011. http://faculty.kfupm.edu.sa/COE/sadiq/proceedings/SCAC2004/15.ASC077.EN.Muhmin&Abdali.Adoption%20of%20Online%20Purchase%20b%20_1_.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2011.

Algesheimer, R., Dholakia, U. M., & Herrmann, A. (2005). The social influence of brand community: evidence from European car clubs. Journal of Marketing, 69(3), 19–34. doi:10.1509/jmkg.69.3.19.66363.

Allagui, A., & Temessek, A. (2004). Testing an e-loyalty conceptual framework. Journal of E-Business, 4(1), 1–6.

Anderson, E. (1985). The salesperson as outside agent or employee: a transaction cost analysis. Marketing Science, 4(3), 234–254. doi:10.1287/mksc.4.3.234.

Anderson, E., & Barton, W. (1992). The use of pledges to build and sustain commitment in distribution channels. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(1), 18–34. doi:10.2307/3172490.

Anderson, R. E., & Srinivasan, S. S. (2003). E-satisfaction and e-loyalty: a contingency framework. Psychology & Marketing, 20(2), 123–138. doi:10.1002/mar.10063.

Angriawan, A., & Thakur, R. (2008). A parsimonious model of the antecedents and consequence of online trust: an uncertainty perspective. Journal of Internet Commerce, 7(1), 74–94. doi:10.1080/15332860802004337.

Antoniou, G., & Batten, L. (2011). E-commerce: protecting purchaser privacy to enforce trust. Electronic Commerce Research, 11(4), 421–456. doi:10.1007/s10660-011-9083-3.

Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Baumgartner, J. (1990). The level of effort required for behaviour as a moderator of the attitude-behaviour relation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 20(1), 45–59.

Balabanis, G., Reynolds, N., & Simintiras, A. (2006). Bases of e-store loyalty: perceived switching barriers and satisfaction. Journal of Business Research, 59(2), 214–224. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.06.001.

Bansal, H. S., Irving, P. G., & Taylor, S. F. (2004). A three-component model of customer to service providers. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(3), 234–250. doi:10.1177/0092070304263332.

Bansal, H. S., McDougall, G. H. G., Dikolli, S. S., & Sedatole, K. L. (2004). Relating e-satisfaction to behavioral outcomes: an empirical study. Journal of Services Marketing, 18(4), 290–302. doi:10.1108/08876040410542281.

Bansal, H. S., & Taylor, S. F. (2002). Investigating interactive effects in the theory of planned behavior in a service provider switching context. Psychology & Marketing, 19(5), 407–425. doi:10.1002/mar.10017.

Barrutia, J. M., & Gilsanz, A. (2011). e-Service quality: literature review and future avenues of research. In C.-P. Praeg & D. Spath (Eds.), Quality management for IT services: perspectives on business and process performance (pp. 22–44). Hershey: Business Science. doi:10.4018/978-1-61692-889-6.ch002.

Bauer, H. H., & Hammerschmidt, M. (2004). Kundenzufriedenheit und Kundenbindung bei Internet-Portalen–Eine kausalanalytische Studie. In H. H. Bauer, J. Rösger, & M. Neumann (Eds.), Konsumentenverhalten im Internet (pp. 189–214). München: Vahlen.

Beatty, S. E., Mayer, M., Coleman, J. E., Reynolds, K. E., & Lee, J. (1996). Customer-sales associate retail relationships. Journal of Retailing, 72(3), 223–247. doi:10.1016/S0022-4359(96)90028-7.

Beldad, A., de Jong, M., & Steehouder, M. (2010). How shall I trust the faceless and the intangible? A literature review on the antecedents of online trust. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 857–869. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.013.

Bhattacherjee, A. (2001). An empirical analysis of the antecedents of electronic commerce service continuance. Decision Support Systems, 32(2), 201–214. doi:10.1016/S0167-9236(01)00111-7.

Bhattacherjee, A. (2001). Understanding information systems continuance: an expectation-confirmation model. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 25(3), 351–370. doi:10.2307/3250921.

Bloemer, J. M. (1995). The complex relationship between consumer satisfaction and brand loyalty. Journal of Economic Psychology, 16(2), 311–329. doi:10.1016/0167-4870(95)00007-B.

Bolton, R. N., & Lemon, K. N. (1999). A dynamic model of customers’ usage of services: usage as an antecedent and consequence of satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(2), 171–186. doi:10.2307/3152091.

Burnham, T. A., Frels, J. K., & Mahajan, V. (2003). Consumer switching costs: a typology, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(2), 109–126. doi:10.1177/0092070302250897.

Cai, S., & Xu, Y. J. (2004). The relationship of online customer value, satisfaction, and loyalty: an empirical study. Paper presented at the 8th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS), Shanghai, China, 8–11 July. AIS. http://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2004/3. Accessed 31 December 2011.

Cai, S., & Xu, Y. J. (2006). Effects of outcome, process and shopping enjoyment on online consumer behaviour. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 5(4), 272–281. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2006.04.004.

Cano, C. R., Boles, J. S., & Bean, C. J. (2005). Communication media preferences in business-to-business transactions: an examination of the purchase process. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 25(3), 283–294.

Carlson, J., & O’Cass, A. (2010). Exploring the relationships between e-service quality, satisfaction, attitudes and behaviors in content-driven e-service web sites. Journal of Services Marketing, 24(2), 112–127. doi:10.1108/08876041011031091.

Caruana, A., & Ewing, M. T. (2010). How corporate reputation, quality, and value influence online loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 63(9–10), 1103–1110. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.04.030.

Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Guinalíu, M. (2008). The role of satisfaction and website usability in developing customer loyalty and positive word-of-mouth in the e-banking services. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 26(6), 399–417. doi:10.1108/02652320810902433.

Castañeda, J. A., Rodríguez, M. A., & Luque, T. (2009). Attitudes’ hierarchy of effects in online user behaviour. Online Information Review, 33(1), 7–21. doi:10.1108/14684520910944364.

Chang, H. H., Wang, Y. H., & Yang, W. Y. (2009). The impact of e-service quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty on e-marketing: moderating effect of perceived value. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 20(4), 423–443. doi:10.1080/14783360902781923.

Chang, Y., Hu, S., & Yan, X. (2009). An empirical research on the mechanism of service recovery and customer loyalty in network retail. Paper presented at the 2009 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Software Engineering (CiSE 2009), Wuhan, China, 11–13 December. IEEE. doi:10.1109/CISE.2009.5365629.

Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 81–93. doi:10.1509/jmkg.65.2.81.18255.

Chen, J., & Dibb, S. (2010). Consumer trust in the online retail context: exploring the antecedents and consequences. Psychology & Marketing, 27(4), 323–346. doi:10.1002/mar.20334.

Chen, J., Luo, M. M., Ching, R. K. H., & Liu, C. C. (2008). Virtual experiential marketing on online customer intentions and loyalty. Paper presented at the 41st Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS 2008), Big Island, HI, 7–10 January. Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE Computer Society. doi:10.1109/HICSS.2008.495.

Chen, J., Zhao, G., & Yan, Y. (2010). Research on customer loyalty of B2C E-commerce based on structural equation modeling. Paper presented at the 1st International Conference on E-Business and E-Government (ICEE 2010), Guangzhou, China, 7–9 May. IEEE. doi:10.1109/ICEE.2010.567.

Chen, Q., Rodgers, S., & He, Y. (2008). A critical review of the e-satisfaction literature. American Behavioral Scientist, 52(1), 38–59. doi:10.1177/0002764208321340.

Chiagouris, L., & Ray, I. (2010). Customers on the web are not all created equal: the moderating role of internet shopping experience. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 20(2), 251–271. doi:10.1080/09593961003701767.

Chiang, K.-P., & Dholakia, R. R. (2003). Factors driving consumer intention to shop online: an empirical investigation. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(1–2), 177–183. doi:10.1207/S15327663JCP13-1&2_16.

Chiou, J. S. (2004). The antecedents of consumers’ loyalty toward internet service providers. Information & Management, 41(6), 685–695. doi:10.1016/j.im.2003.08.006.

Chiu, C. M., Chang, C. C., Cheng, H. L., & Fang, Y. H. (2009). Determinants of customer repurchase intention in online shopping. Online Information Review, 33(4), 761–784. doi:10.1108/14684520910985710.

Chiu, C. M., Lin, H. Y., Sun, S. Y., & Hsu, M. H. (2009). Understanding customers’ loyalty intentions towards online shopping: an integration of technology acceptance model and fairness theory. Behavior & Information Technology, 28(4), 347–360. doi:10.1080/01449290801892492.

Chung, K. H., & Shin, J. I. (2010). The antecedents and consequents of relationship quality in internet shopping. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 22(4), 473–491. doi:10.1108/13555851011090510.

Cronin, J. J. Jr., & Taylor, S. A. (1992). Measuring service quality: a reexamination and extension. Journal of Marketing, 56(3), 55–68. doi:10.2307/1252296.

Cronin, J. J. Jr, & Taylor, S. A. (1994). SERVPERF versus SERVQUAL: reconciling performance-based and perceptions-minus-expectations measurement of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 58(1), 125–131. doi:10.2307/1252256.

Cyr, D., Hassanein, K., Head, M., & Ivanov, A. (2007). The role of social presence in establishing loyalty in e-Service environments. Interacting with Computers, 19(1), 43–56. doi:10.1016/j.intcom.2006.07.010.

Cyr, D., Head, M., & Ivanov, A. (2009). Perceived interactivity leading to e-loyalty: development of a model for cognitive-affective user responses. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 67(10), 850–869. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2009.07.004.

Dai, H., Salam, A. F., & King, R. (2008). Service convenience and relational exchange in electronic mediated environment: an empirical investigation. Paper presented at the 29th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2008), Paris, France, 14–17 December. AIS. http://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2008/63. Accessed 31 December 2011.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. doi:10.2307/249008.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: a comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982–1003. doi:10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982.

Day, G. S. (2000). Managing market relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 24–30. doi:10.1177/0092070300281003.

DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (1992). Information systems success: the quest for the dependent variable. Information Systems Research, 3(1), 60–95. doi:10.1287/isre.3.1.60.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Devaraj, S., Fan, M., & Kohli, R. (2003). E-loyalty: elusive ideal or competitive edge? Communications of the ACM, 46(9), 184–191. doi:10.1145/903893.903936.

Dinev, T., & Hart, P. (2005). Internet privacy concerns and social awareness as determinants of intention to transact. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 10(2), 7–29. doi:10.2753/JEC1086-4415100201.

Doney, P. M., & Cannon, J. P. (1997). An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 61(2), 35–51. doi:10.2307/1251829.

Eid, M., & Al-Anazi, F. U. (2008). Factors influencing Saudi consumers loyalty toward B2C E-commerce. Paper presented at the 14th Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS 2008), Toronto, ON, 14–17 August. AIS. http://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2008/405. Accessed 31 December 2011.

Ellis, R. D., & Allaire, J. C. (1999). Modeling computer interest in older adults: the role of age, education, computer knowledge, and computer anxiety. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 41(3), 345–355. doi:10.1518/001872099779610996.

Eroglu, S. A., Machleit, K. A., & Davis, L. M. (2003). Empirical testing of a model of online store atmospherics and shopper responses. Psychology & Marketing, 20(2), 139–150. doi:10.1002/mar.10064.

Finn, A., & Kayandé, U. (1999). Unmasking a phantom: a psychometric assessment of mystery shopping. Journal of Retailing, 75(2), 195–217. doi:10.1016/S0022-4359(99)00004-4.

Flavián, C., Guinalíu, M., & Gurrea, R. (2006). The role played by perceived usability, satisfaction and consumer trust on website loyalty. Information & Management, 43(1), 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.im.2005.01.002.

Flavián, C., Martínez, E., & Polo, Y. (2001). Loyalty to grocery stores in the Spanish market of the 1990s. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 8(2), 85–93. doi:10.1016/S0969-6989(99)00028-4.

Floh, A., & Treiblmaier, H. (2006). What keeps the e-banking customer loyal? A multigroup analysis of the moderating role of consumer characteristics on e-loyalty in the financial service industry. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 7(2), 97–110.

Fournier, S., & Mick, D. G. (1999). Rediscovering satisfaction. Journal of Marketing, 63(4), 5–23. doi:10.2307/1251971.

Fuentes-Blasco, M., Saura, I. G., Berenguer-Contri, G., & Moliner-Velazquez, B. (2010). Measuring the antecedents of e-loyalty and the effect of switching costs on website. Service Industries Journal, 30(11), 1837–1852. doi:10.1080/02642060802626774.

Garbarino, E., & Johnson, M. S. (1999). The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. Journal of Marketing, 63(2), 70–87. doi:10.2307/1251946.

Gefen, D. (2002). Customer loyalty in e-commerce. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 3(1), 27–51.

Gefen, D., & Devine, P. (2001). Customer loyalty to an online store: the meaning of online service quality. Paper presented at the 22nd International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, 16–19 December. Association for Information Systems. http://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2001/80. Accessed 31 December 2011.

Gefen, D., & Straub, D. W. (2000). The relative importance of perceived ease of use in IS adoption: a study of e-commerce adoption. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 1(8).

Glass, B. (1955). Survey of biological abstracting. Science, 121(3147), 583–584. doi:10.1126/science.121.3147.583.

Gommans, M., Krishnan, K. S., & Scheffold, K. B. (2001). From brand loyalty to e-loyalty: a conceptual framework. Journal of Economic and Social Research, 3(1), 43–58.

Goode, M. M. H., & Harris, L. C. (2007). Online behavioral intentions: an empirical investigation of antecedents and moderators. European Journal of Marketing, 41(5–6), 512–536. doi:10.1108/03090560710737589.

Gounaris, S., Dimitriadis, S., & Stathakopoulos, V. (2010). An examination of the effects of service quality and satisfaction on customers’ behavioral intentions in e-shopping. Journal of Services Marketing, 24(2–3), 142–156. doi:10.1108/08876041011031118.

Gremler, D. D. (1995). The effect of satisfaction, switching costs, and interpersonal bonds on service loyalty. Ph.D. Thesis, Arizona State University, Arizona.

Gummerus, J., Liljander, V., Pura, M., & van Riel, A. (2004). Customer loyalty to content-based web sites: the case of an online health-care service. Journal of Services Marketing, 18(3), 175–186. doi:10.1108/08876040410536486.

Ha, H. Y. (2004). Factors affecting online relationships and impacts. Marketing Review, 4(2), 189–209. doi:10.1362/1469347041569812.

Ha, H. Y., & Janda, S. (2008). An empirical test of a proposed customer satisfaction model in e-services. Journal of Services Marketing, 22(5), 399–408. doi:10.1108/08876040810889166.

Hackman, D., Gundergan, S. P., Wang, P., & Daniel, K. (2006). A service perspective on modelling intentions of on-line purchasing. Journal of Services Marketing, 20(7), 459–470. doi:10.1108/08876040610704892.

Harris, L. C., & Goode, M. M. H. (2004). The four levels of loyalty and the pivotal role of trust: a study of online service dynamics. Journal of Retailing, 80(2), 139–158. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2004.04.002.

Hart, C. (1998). Doing a literature review. London: Sage.

Hart, C., Farrell, A. M., Stachow, G., Reed, G., & Cadogan, J. W. (2007). Enjoyment of the shopping experience: impact on customers’ repatronage intentions and gender influence. Service Industries Journal, 27(5), 583–604. doi:10.1080/02642060701411757.

Hasan, B. (2010). Exploring gender differences in online shopping attitude. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(4), 597–601. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2009.12.012.

Herington, C., & Weaven, S. (2007). Can banks improve customer relationships with high quality online services? Managing Service Quality, 17(4), 404–427. doi:10.1108/09604520710760544.

Homburg, C., & Giering, A. (2001). Personal characteristics as moderators of the relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty—an empirical analysis. Psychology & Marketing, 18(1), 43–66. doi:10.1002/1520-6793(200101)18:1<43::AID-MAR3>3.0.CO;2-I.

Hong, W., Thong, J. Y. L., Wong, W. M., & Tam, K. Y. (2002). Determinants of user acceptance of digital libraries: an empirical examination of individual differences and system characteristics. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(3), 97–124.

Hörner, J. (2002). Reputation and competition. American Economic Review, 92(3), 644–663. doi:10.1257/00028280260136444.

Hsieh, Y. C., Chiu, H. C., & Chiang, M. Y. (2005). Maintaining a committed online customer: a study across search-experience-credence products. Journal of Retailing, 81(1), 75–82. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2005.01.006.

Hsu, C. I., Lin, B. Y., & Chang, K. C. (2009). On-line shopping loyalty and its antecedents. International Journal of Information, 5(1), 11–20.

Huang, L. (2008). Exploring the determinants of E-loyalty among travel agencies. Service Industries Journal, 28(2), 239–254. doi:10.1080/02642060701842316.

Huang, Y. K., Kuo, Y. W., & Xu, S. W. (2009). Applying Importance-performance analysis to evaluate logistics service quality for online shopping among retailing delivery. International Journal of Electronic Business, 7(2), 128–136.

Igbaria, M., Guimaraes, T., & Davis, G. B. (1995). Testing the determinants of microcomputer usage via a structural equation model. Journal of Management Information Systems, 11(4), 87–114.

Imhof, M., Vollmeyer, R., & Beierlein, C. (2007). Computer use and the gender gap: the issue of access, use, motivation, and performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(6), 2823–2837. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2006.05.007.

Jacoby, J., & Chestnut, R. W. (1978). Brand loyalty: measurement and management. New York: Wiley.

Jarvenpaa, S. L., & Todd, P. A. (1997). Consumer reactions to electronic shopping on the world wide web. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 1(2), 59–88.

Jiang, P., & Rosenbloom, B. (2005). Customer intention to return online: price perception, attribute-level performance, and satisfaction unfolding over time. European Journal of Marketing, 39(1–2), 150–174. doi:10.1108/03090560510572061.

Jiang, Z., Chan, J., Tan, B. C. Y., & Chua, W. S. (2010). Effects of interactivity on website involvement and purchase intention. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 11(1), 34–59.

Jin, B., & Kim, J. (2010). Multichannel versus pure e-tailers in Korea: evaluation of online store attributes and their impacts on e-loyalty. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 20(2), 217–236. doi:10.1080/09593961003701825.

Jin, B., & Park, J. Y. (2006). The moderating effect of online purchase experience on the evaluation of online store attributes and the subsequent impact on market response outcomes. In C. Pechmann & L. L. Price (Eds.), Advances in consumer research (Vol. 33, pp. 203–211). Valdosta: Association for Consumer Research.

Jin, B., Park, J. Y., & Kim, J. (2008). Cross-cultural examination of the relationships among firm reputation, e-satisfaction, e-trust, and e-loyalty. International Marketing Review, 25(3), 324–337. doi:10.1108/02651330810877243.

Jin, L. (2009). Dimensions and determinants of website brand equity: from the perspective of website contents. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 3(4), 514–542. doi:10.1007/s11782-009-0025-z.

Jones, C., & Kim, S. (2010). Influences of retail brand trust, off-line patronage, clothing involvement and website quality on online apparel shopping intention. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 34(6), 627–637. doi:10.1111/j.1470-6431.2010.00871.x.

Karahanna, E., Seligman, L., Polites, G. L., & Williams, C. K. (2009). Consumer e-satisfaction and site stickiness: an empirical investigation in the context of online hotel reservations. Paper presented at the 42nd Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS-42 2009), Waikoloa, HI, 5–8 January. Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE Computer Society. doi:10.1109/HICSS.2009.129.

Kassim, N. M., & Ismail, S. (2009). Investigating the complex drivers of loyalty in e-commerce settings. Measuring Business Excellence, 13(1), 56–71. doi:10.1108/13683040910943054.

Kim, E. Y., & Kim, Y. K. (2004). Predicting online purchase intentions for clothing products. European Journal of Marketing, 38(7), 883–897. doi:10.1108/03090560410539302.

Kim, M.-J., Chung, N., & Lee, C.-K. (2011). The effect of perceived trust on electronic commerce: shopping online for tourism products and services in South Korea. Tourism Management, 32(2), 256–265. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2010.01.011.

Koo, D. M. (2006). The fundamental reasons of e-consumers’ loyalty to an online store. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 5(2), 117–130. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2005.10.003.

Koppius, O., Speelman, W., Stulp, O., Verhoef, B., & van Heck, E. (2005). Why are customers coming back to buy their airline tickets online? Theoretical explanations and empirical evidence. Paper presented at the 7th International Conference on Electronic Commerce, Xi’an, China, New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/1089551.1089611.

Koufaris, M. (2002). Applying the technology acceptance model and flow theory to online consumer behavior. Information Systems Research, 13(2), 205–223. doi:10.1287/isre.13.2.205.83.

Lange, D., Lee, P. M., & Dai, Y. (2011). Organizational reputation: a review. Journal of Management, 37(1), 153–184. doi:10.1177/0149206310390963.

Lee, H., Choi, S. Y., & Kang, Y. S. (2009). Formation of e-satisfaction and repurchase intention: moderating roles of computer self-efficacy and computer anxiety. Expert Systems with Applications, 36(4), 7848–7859. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2008.11.005.

Lee, J., Kim, J., & Moon, J. Y. (2000). What makes internet users visit cyber stores again? Key design factors for customer loyalty. CHI Letters, 2(1), 305–312.

Lee, P.-M. (2002). Behavioral model of online purchasers in e-commerce environment. Electronic Commerce Research, 2(1), 75–85. doi:10.1023/a:1013340118965.

Lee, S. M., Hwang, T., & Lee, D. H. (2011). Evolution of research areas, themes, and methods in electronic commerce. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 21(3), 177–201. doi:10.1080/10919392.2011.590095.

Li, H., Daugherty, T., & Biocca, F. (2002). Impact of 3-D advertising on product knowledge, brand attitude, and purchase intention: the mediating role of presence. Journal of Advertising, 31(3), 43–57.

Li, H., Kuo, C., & Rusell, M. G. (1999). The impact of perceived channel utilities, shopping orientations, and demographics on the consumer’s online buying behavior. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 5(2). doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.1999.tb00336.x.

Lim, H., & Dubinsky, A. J. (2005). The theory of planned behavior in e-commerce: making a case for interdependencies between salient beliefs. Psychology & Marketing, 22(10), 833–855. doi:10.1002/mar.20086.

Limayem, M., Khalifa, M., & Frini, A. (2000). What makes consumers buy from Internet? A longitudinal study of online shopping. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Part A: Systems and Humans, 30(4), 421–432. doi:10.1109/3468.852436.

Lin, C.-Y., Tu, C.-C., & Fang, K. (2008). Modeling the trust with ECT in e-auction loyalty. Paper presented at the 3rd IEEE Asia-Pacific Services Computing Conference (APSCC 2008), Yilan, Taiwan, 9–12 December. IEEE. doi:10.1109/APSCC.2008.224.

Lin, J. C. C. (2007). Online stickiness: its antecedents and effect on purchasing intention. Behavior & Information Technology, 26(6), 507–516. doi:10.1080/01449290600740843.

Liong, L. S., Arif, M. S. M., Tat, H. H., Rasli, A., & Jusoh, A. (2011). Relationship between service quality, satisfaction, and loyalty of Google users. International Journal of Electronic Commerce Studies, 2(1), 35–56.

Liu, H. Y., & Hung, W. T. (2010). Online store trustworthiness and customer loyalty: moderating the effect of the customer’s perception of the virtual environment. African Journal of Business Management, 4(14), 2915–2920.

Luarn, P., & Lin, H. H. (2003). A customer loyalty model for e-service context. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 4(4), 156–167.

Lynch, P. D., Kent, R. J., & Srinivasan, S. S. (2001). The global internet shopper: evidence from shopping tasks in twelve countries. Journal of Advertising Research, 41(3), 15–23.

Ma, H. M., Meng, C. C., Zhu, K., & Xiao, J. Y. (2008). An empirical research of consumer loyalty model in B2C electronic commerce. Paper presented at the 4th International Conference on Wireless Communications, Networking and Mobile Computing, 2008 (WiCOM’08), Dalian, China, 12–17 October. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE. doi:10.1109/WiCom.2008.2231.

MacCoun, R. J. (1998). Biases in the interpretation and use of research results. Annual Review of Psychology, 49(1), 259–287. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.259.