Abstract

Current evidence on the association between body mass index (BMI) and age at menopause remains unclear. We investigated the relationship between BMI and age at menopause using data from 11 prospective studies. A total of 24,196 women who experienced menopause after recruitment was included. Baseline BMI was categorised according to the WHO criteria. Age at menopause, confirmed by natural cessation of menses for ≥ 12 months, was categorised as < 45 years (early menopause), 45–49, 50–51 (reference category), 52–53, 54–55, and ≥ 56 years (late age at menopause). We used multinomial logistic regression models to estimate multivariable relative risk ratios (RRRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the associations between BMI and age at menopause. The mean (standard deviation) age at menopause was 51.4 (3.3) years, with 2.5% of the women having early and 8.1% late menopause. Compared with those with normal BMI (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), underweight women were at a higher risk of early menopause (RRR 2.15, 95% CI 1.50–3.06), while overweight (1.52, 1.31–1.77) and obese women (1.54, 1.18–2.01) were at increased risk of late menopause. Overweight and obesity were also significantly associated with around 20% increased risk of menopause at ages 52–53 and 54–55 years. We observed no association between underweight and late menopause. The risk of early menopause was higher among obese women albeit not significant (1.23, 0.89–1.71). Underweight women had over twice the risk of experiencing early menopause, while overweight and obese women had over 50% higher risk of experiencing late menopause.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Age at natural menopause, defined as the time when a woman has experienced 12 consecutive months of amenorrhea, has a range of health implications as a marker for biological ageing and subsequent morbidity and mortality. Early menopause is associated with higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality, all-cause mortality [1, 2], type 2 diabetes [3], low bone density and osteoporosis [4], while late menopause increases the risk of breast cancer [5] and probably endometrial cancer [6].

In high-income countries, average age at menopause is 51.4 years [7], but varies between populations from 49 to 52 years [8]. Factors shown to be associated with the timing of menopause include genetic, demographic, and reproductive characteristics, as well as lifestyle and body weight [9]. If a mother has an early menopause, her daughter is more likely to also reach menopause early [8, 9]. Early menarche and nulliparity are both linked with earlier age at menopause [10] as is also lower education and low socioeconomic status [11]. Cigarette smoking, the most established modifiable determinant of age at menopause, hastens the onset of menopause by almost a year [11].

Another potentially modifiable factor that might affect age at menopause is body mass index (BMI). To date, evidence on the relationship between BMI and age at menopause has been inconsistent. High BMI has been linked to both later [7, 11,12,13,14,15], and earlier menopause [16, 17] whilst some studies have found no association [18,19,20]. Low BMI has been related to early menopause [14, 21], but some studies report no significant relationship [17, 22]. Inconsistent results across studies could be due to differences in study samples, study designs, classification of BMI levels, and adjustment for confounding variables.

Our aim was to investigate the relationship between different categories of BMI and the timing of age at menopause across several studies that include data from multiple racial/ethnic groups of women, whilst taking into account a range of potential confounding factors. We have available pooled participant-level data for over 24,000 postmenopausal women from prospective studies contributing to the International Collaboration for a Life Course Approach to Reproductive Health and Chronic Disease Events (InterLACE) [23, 24].

Materials and methods

Study participants

InterLACE has brought together 23 observational, mostly longitudinal cohort studies with data on women’s health as previously described in detail [23, 24]. Participating studies collected survey data on key reproductive, sociodemographic, lifestyle, and disease outcome variables. In the present analyses, we used prospective design to examine the association between baseline BMI categories and age at menopause which occurred after baseline survey. Thus, women who experienced menopause before baseline were excluded (n = 37,691). This pooled study therefore consisted of 24,196 women who were premenopausal at baseline and reached menopause at a subsequent survey, had reported age at natural menopause, and had complete data on BMI as well as key covariates at baseline, including smoking status, education level, race/ethnicity, and number of children. As a consequence, 11 prospective studies were included (Table 1). NSHD (1946 British Birth Cohort) and NCDS (1958 British Birth Cohort) are birth cohort studies which collected information on women’s reproductive health from 1993 (women aged 47 years) and 2008 (women aged 50 years), respectively. The sampling strategy with exclusion criteria is presented in Supplementary Figure 1.

Outcome and exposure variables

The outcome was age at menopause, confirmed by at least 12 months of cessation of menses that did not result from interventions (such as bilateral oophorectomy, hysterectomy, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy); women having these procedures were excluded. For women who were currently taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) (unless natural or surgical menopausal was specifically reported), we defined their menopausal status separately as “unknown due to hormone use”, and the data on menopause age were not available for this group [24]. Age at menopause was categorised as < 45 years (early menopause), 45–49, 50–51 (reference category), 52–53, 54–55, or 56 years and above (late menopause).

The exposure variable was BMI, based on either self-recorded or measured data at the baseline survey. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2) and was categorised according to the WHO criteria [25], into: underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25 to 29.9 kg/m2) and obese (≥ 30 kg/m2). Because the two birth cohort studies (NSHD and NCDS) collected BMI information at each follow-up survey after birth, BMI from the survey before women reported having undergone menopause was treated as the baseline.

The following demographic and lifestyle factors reported at baseline surveys (or at mid age surveys for the birth cohort studies) were included in the analysis as covariates: smoking status (never smokers, past smokers, and current smokers), years of education (≤ 10, 11–12, and > 12 years), race/ethnicity (Caucasian-European, Caucasian-Australian/New Zealand, Caucasian-American/Canadian, and non-Caucasian (including Asian, African Americans, Middle Eastern, etc.)), number of children (none, 1, 2, and 3 or more children) and age at menarche (≤ 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15 years or more). Employment and marital status were not included as covariates for missing in MCCS and NCDS study. Also, genetic factors, early life factors and comorbidities (e.g., cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease(COPD)) were unmeasured and may lead to residual confounding.

Statistical analysis

We used multinomial (polytomous) logistic regression models with six categories of outcome for age at menopause (< 45, 45–49, 50–51, 52–53, 54–55, 56 years and older) to examine the associations between baseline BMI categories and age at menopause. We used age 50–51 years at menopause as reference group for the outcome, and BMI 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2 as reference group for the exposure. Statistical models were adjusted for smoking status, education level, race/ethnicity, and number of children. Variables were retained in model at P ≤ 0.05. Multivariable relative risk ratios (RRRs) [26] and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated for the relation between BMI categories and each category of age at menopause, adjusting for covariates. Age at menarche is also a potential confounder that could affect the association between BMI and age at menopause. Thus, the models were additionally adjusted for age at menarche but with only ten studies included in the analysis (n = 21,991), because no information on age at menarche was available from the WHITEHALL study. We also used fractional-polynomial model to examine possible non-linear relationship between BMI and age at menopause by treating them as continuous variables using total sample of 24,196 women.

We undertook several sensitivity analyses to examine the robustness of our findings. To minimise the possible influence of peri-menopause on BMI at midlife, we analysed the association of BMI with age at menopause for women who experienced menopause at least 1, 2, 3, and 5 years after their baseline BMI was collected. Body weight may increase with age, and women enrolled at older ages are likely to have a higher BMI and have a higher chance of later menopause. We therefore performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding women who enrolled after the age of 50 years. Specific BMI cut-off points have been recommended for Asians [27]. Hence, we also did a sensitivity analysis by using the “Asian BMI criteria” (underweight, < 18.5 kg/m2; normal weight, 18.5–22.9 kg/m2; overweight, 23–27.4 kg/m2; obese, ≥ 27.5 kg/m2) for women of Asian ethnicity. We also performed an analysis excluding women whose BMI was obtained by self-reported height and weight at baseline. Additionally, we performed study-specific regression and random-effects meta-analysis for studies which had sufficient data to estimate the between-study heterogeneity in the effect size estimates.

The SURVEYLOGISTIC procedure was carried out with the generalised logit link that estimates sampling errors based on the clustered sample survey from multiple studies and incorporates that in the estimates. All tests of statistical hypothesis were two-sided, and the level of significance was 5%. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC), and the METAN command in Stata (version 14.0, Stata Corp., College Station, TX) was used to perform meta-analysis.

Each study in the InterLACE consortium has been undertaken with ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board or Human Research Ethics Committee at each participating institution, and all participants provided consent for that study.

Results

Study characteristics

Altogether 24,196 women experienced natural menopause after baseline. Most of them were born between 1940 and 1949 (Table 1). The mean (standard deviation, SD) BMI was 24.9 (4.8) kg/m2 (median 23.9 kg/m2, interquartile range 21.7–26.9 kg/m2), with 1.6, 26.5, and 12.8% of the women underweight, overweight, and obese, respectively. The mean age at baseline BMI was 46.0 (3.8) years, and the mean age at menopause was 51.4 (3.3) years (median 52.0 years, interquartile range 50.0–54.0 years) (supplementary Tables S1 and S2). A small percentage (2.5%) had early menopause (age at menopause < 45 years) and 8.1% late menopause (age at menopause ≥ 56 years).

Compared with the women who were never-smokers or past smokers, women who were current smokers had the highest proportion of underweight (2.7%) and early menopause (4.0%) and the lowest proportion of late menopause (5.5%) (Table 2). The proportions of women who were both underweight (from 2.2 to 1.3%) and had early menopause (from 3.8 to 1.9%) decreased with increasing number of children, while the proportions of overweight/obese women and those with late menopause increased. Conversely, with increasing age at menarche, the proportions of women in the underweight category and with late menopause increased, while the proportions of overweight/obese women and those with early menopause decreased.

Association between BMI and age at menopause

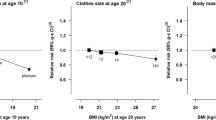

BMI was positively associated with age at menopause, and the strength of this relationship remained after adjusting for race/ethnicity, education level, smoking status, and number of children (Table 3). Compared with normal weight women, underweight women had more than twice the risk of experiencing early menopause (RRR: 2.15, 95% CI 1.50, 3.06; age at menopause 50–51 years as the reference group). The overweight and obese categories were both associated with late menopause, with multivariable RRR of 1.52 (95% CI 1.31, 1.77) and 1.54 (95% CI 1.18, 2.01), respectively. Being overweight/obese was also significantly associated with age at menopause categories of 52–53 and 54–55 with an approximately 20% higher risk (RRRs range from 1.20 to 1.26). The associations were also graphically demonstrated in Fig. 1. We observed that the association appeared linear in the overweight group, while it followed a semi-J shape association in the underweight and obese groups. An increased risk of early menopause was not found to be significant for the obese group (RRR: 1.23, 95% CI 0.89, 1.71). When further adjusted for age at menarche (i.e. WHITEHALL study was not included, data not shown), the estimates remained unchanged. In addition, when we considered BMI and age at menopause as continuous variables, a nonlinear relationship was observed between BMI and age at menopause (Supplementary Figure 2).

Sensitivity analyses

The results of the sensitivity analysis which took into account whether onset of menopause occurred 1, 2, 3, and 5 years after baseline BMI indicated that associations remained for all groups and were particularly strong for the women in the underweight or obese categories with BMI data at least 5 years prior to the onset of natural menopause (n = 13,519) (Table 4). These underweight women were at over threefold higher risk of experiencing early menopause (RRR 3.11, 95% CI 2.23–4.44), while obese women were at nearly twice the risk of having late menopause (RRR 1.80, 95% CI 1.41–2.31), compared with women with normal BMI. Sensitivity analyses that excluded women who enrolled after 50 years of age or women with self-reported BMI and that used “Asian BMI criteria” for women in Asian ethnicity all showed results consistent with those from main analyses (data not shown).

Meta-analyses

Of the 11 studies, four had sufficient data to conduct study-specific analyses of the relation of underweight with early menopause, and eight had sufficient data to contribute to the study-specific analyses of the estimates of the association of overweight and obesity with late menopause (Fig. 2). Random-effects meta-analysis of the estimates from the four studies produced a pooled RRR of 2.14 (95% CI 1.21–3.77) for the association of underweight with early menopause. In addition, meta-analysis from the eight studies resulted in a pooled RRR of 1.52 (95% CI 1.29–1.79) and 1.35 (95% CI 1.14–1.60) for the effect of overweight and obesity on late menopause, respectively. We found no significant heterogeneity between studies (P > 0.05).

Discussion

Our results indicate that underweight women are over twice as likely to experience early menopause, and overweight and obese women are 50% more likely to have late menopause. These associations were stronger for women with underweight or obese BMI being reported at least 5 years prior to onset of menopause. These findings provide strong evidence that being underweight may trigger early menopause and confirm that being overweight or obese may delay menopause.

In line with our findings, several studies have reported higher BMI to be significantly associated with later menopause [7, 11, 13,14,15], although some studies have reported no association [18,19,20,21]. A recent systematic review reported a weak association [hazard ratio (HR) (95% CI): 0.93 (0.91, 0.96)], indicating that overweight women were less likely to experience an earlier menopause. Yet no relationship was found between obesity and later menopause, compared with women with normal BMI [28]. The differences between our findings and those of the systematic review might have arisen because the HRs of the systematic review were extracted and pooled from studies with a mix of designs (heterogeneity test: P < 0.01), including five cross-sectional studies, three prospective cohorts, and one retrospective cohort. In contrast, all studies included in our present analyses had a prospective design. In addition, different BMI cut-off points were used among studies, and some studies did not control for smoking, an important confounder. Our findings indicate that being overweight or obese entails a 50% higher risk of late menopause, after controlling for confounding, including smoking. Two previous cross-sectional studies with limited sample size found overweight [16] or obesity [17] related to earlier menopause. In our study, a higher RRR 1.23 (95% CI 0.89, 1.71) for early menopause among obese women was suggested but not significant, potentially due to the small number of cases. Given the semi-J shape of the associations between BMI and early menopause, the overall findings suggest obesity was not only associated with late menopause but also has some association with early menopause. This was also supported by the nonlinear relationship we observed by treating BMI and age at menopause as continuous variables.

The link between overweight or obesity and late age at menopause may be explained by the complex functions of adipose tissue. Adipose tissue functions as a specialized endocrine and paracrine organ. One of its roles is the production of an array of adipokines [29]. Leptin, the most investigated adipokine, is produced and secreted in proportion to body fat mass and inhibits hunger. It communicates information about body energy reserves, nutritional state, and metabolic shifts to the reproductive axis. Leptin can act peripherally at the ovary or centrally at the hypothalamus to augment female reproductive function [30, 31]. A recent study has shown that early menopause is associated with low leptin levels [32]. However, specific roles for adipose tissue and adipokines in maintaining cyclicity and postponing menopause remain to be studied. In addition, Sowers et al. [33] has found the type 1 β17HSD genes were associated with five single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) variation in obese women. These SNPs variation were related to a lower estradiol’s decline rate in the menopausal transition period, and the estradiol’s decline rate in obese women was half that of non-obese women. The observed genetic correlations between reproductive hormones and BMI may suggest genetic polymorphisms play a role in the relationship.

Our major finding was that underweight BMI was linked to early menopause. Previous studies which had women with underweight or lower BMI as the reference group precluded the possibility of examining the effect of lower BMI directly on age at menopause [7, 13, 15, 19]. In our study, women with normal BMI formed the reference category, and in comparison, underweight women had over twice the risk of early menopause. This is consistent with findings from a cross-sectional study [HR (95% CI): 1.13 (1.02, 1.25)] [14] and a prospective study [HR (95% CI): 1.30 (1.02, 1.65)] [21], although our adjusted risk estimate is greater. Even though the prevalence of underweight among mid-age women was low (only 1.6%, N = 398) in this study), and the prevalence of early menopause was less than 5%, the study had sufficient statistical power to detect an association based on the 24 cases of underweight women with early menopause (RRR: 2.15, 95% CI 1.50–3.06). Being underweight may trigger early menopause as a result of malnutrition [34], concurrent or previous chronic illness (such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) [35], over-exercising [36], and weight-loss diet [18]. Also, less adipose tissue leads to lower leptin levels, which also relate to early menopause [32].

Weight change during the period of menopausal transition may influence the association between overweight/obesity and age at menopause. Because some studies have found that the menopausal transition is associated with weight gain [37, 38], causal inference about the relationship between overweight/obesity and age at menopause is complicated if women reported being overweight/obese during their menopausal transition period. Our sensitivity analysis, which examined the association for women who experienced onset of menopause from one to 5 years after the collection of baseline BMI data, showed that both the relations of underweight and overweight/obesity to age at menopause were maintained or strengthened, especially for women with BMI not in the normal range five or more years prior to their onset of menopause. These stronger results from the sensitivity analyses suggest that the associations of BMI in the main analysis may have been partly attenuated by baseline BMI collected in the perimenopausal period. However, the association between menopausal transition and weight change may not be strong. Using longitudinal data, SWAN showed that menopausal status was not associated with the increase in weight but more with ageing, and weight gain preceded changes in serum hormone levels [39]. Also, weight increases with age in many populations [40]. Thus, the women who enrolled at older ages would tend to have had a higher BMI and have a higher risk of later menopause. Nevertheless, in a sensitivity analysis excluding women who enrolled after the age of 50 years, we found results similar to those from the main analyses.

The main strength of this study was the use of pooled individual-level data from 11 prospective studies across different geographic regions and racial/ethnic populations. This provided a large number of women who were followed-up prospectively from pre or peri-menopause at baseline to post-menopause. The large sample size also ensured sufficient power to analyse the association of BMI levels with six categories of age at menopause, especially with early and late menopause, while many previous studies were limited by small sample sizes or short lengths of follow-up [18, 19, 21, 22, 41, 42] and were cross-sectional or retrospective in nature [7, 14, 15, 17, 20, 43]. Also, the participant-level data in InterLACE enabled harmonising variables using common definitions, coding and cut points which are not usually possible with meta-analyses of published results.

A number of limitations also need to be acknowledged. First, InterLACE pooled data mainly from longitudinal studies of women in midlife, most of whom were enrolled when they were in their 40 s or 50 s (except for the birth cohorts). Thus, the mean age of baseline BMI in the present study was 46.0 years. This limitation restricted our ability to consider an influence of BMI at earlier ages. Our results should be applied with some caution to women in younger age groups. Nevertheless, one individual study (NSHD) in InterLACE found underweight women at age 36 years had significantly earlier menopause than normal weight women [21]. Two other/studies found obesity at age 18 years [44] and higher BMI (BMI in upper 25%) at age 40 or 41 years [41] was linked with later age at menopause. Second, our study only used one single measurement of BMI at midlife. It would provide a better understanding with the timing of menopause if the information on BMI history or trajectories of BMI was available. NSHD study has evaluated the BMI trajectories (from 20 to 36 years) and age at menopause using a prospective cohort design and found no significant associations [21]. Although we have adjusted for a range of confounding factors, some unmeasured confounders, such as genetic factors, early childhood factors, and comorbidities (e.g., cancer [45] and COPD [35]), could affect our observed results. Another limitation was that of the 11 prospective studies included, five of them contributed 31% of the women with self-reported baseline height and weight which may have led to some degree of bias, but a sensitivity analysis conducted only including women with measured baseline BMI showed estimates consistent with the main results.

In summary, in addition to supporting a previously reported association between higher BMI and later menopause, our study also provides strong evidence that underweight is a risk factor for early menopause. Underweight women are at increased risk of early age at menopause, which they should be warned is a risk factor for CVD [1, 2], and osteoporosis [4]. Obese women are more likely to have late menopause, which is a risk factor for breast cancer and is in addition to the risks of poor health outcomes directly attributed to obesity [5, 46].

References

Gong D, Sun J, Zhou Y, Zou C, Fan Y. Early age at natural menopause and risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Int J Cardiol. 2016;203:115–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.092.

Muka T, Oliver-Williams C, Kunutsor S, Laven JS, Fauser BC, Chowdhury R, et al. Association of age at onset of menopause and time since onset of menopause with cardiovascular outcomes, intermediate vascular traits, and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(7):767–76. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2016.2415.

Brand JS, Onland-Moret NC, Eijkemans MJ, Tjonneland A, Roswall N, Overvad K, et al. Diabetes and onset of natural menopause: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(6):1491–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev054.

Kritz-Silverstein D, Barrett-Connor E. Early menopause, number of reproductive years, and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(7):983–8.

Kelsey JL, Gammon MD, John EM. Reproductive factors and breast cancer. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15(1):36–47.

Kaaks R, Lukanova A, Kurzer MS. Obesity, endogenous hormones, and endometrial cancer risk: a synthetic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2002;11(12):1531–43.

Henderson KD, Bernstein L, Henderson B, Kolonel L, Pike MC. Predictors of the timing of natural menopause in the Multiethnic Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(11):1287–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwn046.

Morabia A, Costanza MC. International variability in ages at menarche, first livebirth, and menopause. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Neoplasia and Steroid Contraceptives. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(12):1195–205.

Gold EB. The timing of the age at which natural menopause occurs. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2011;38(3):425–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2011.05.002.

Mishra GD, Pandeya N, Dobson AJ, Chung HF, Anderson D, Kuh D, et al. Early menarche, nulliparity and the risk for premature and early natural menopause. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(3):679–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dew350.

Schoenaker DA, Jackson CA, Rowlands JV, Mishra GD. Socioeconomic position, lifestyle factors and age at natural menopause: a systematic review and meta-analyses of studies across six continents. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(5):1542–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu094.

Gold EB, Crawford SL, Avis NE, Crandall CJ, Matthews KA, Waetjen LE, et al. Factors related to age at natural menopause: longitudinal analyses from SWAN. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:70–83.

Li L, Wu J, Pu D, Zhao Y, Wan C, Sun L, et al. Factors associated with the age of natural menopause and menopausal symptoms in Chinese women. Maturitas. 2012;73(4):354–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.09.008.

Morris DH, Jones ME, Schoemaker MJ, McFadden E, Ashworth A, Swerdlow AJ. Body mass index, exercise, and other lifestyle factors in relation to age at natural menopause: analyses from the breakthrough generations study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(10):998–1005. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr447.

Yasui T, Hayashi K, Mizunuma H, Kubota T, Aso T, Matsumura Y, et al. Factors associated with premature ovarian failure, early menopause and earlier onset of menopause in Japanese women. Maturitas. 2012;72(3):249–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.04.002.

Beser E, Aydemir V, Bozkaya H. Body mass index and age at natural menopause. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1994;37(1):40–2.

Dratva J, Gomez Real F, Schindler C, Ackermann-Liebrich U, Gerbase MW, Probst-Hensch NM, et al. Is age at menopause increasing across Europe? Results on age at menopause and determinants from two population-based studies. Menopause (New York, NY). 2009;16(2):385–94. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e31818aefef.

Bromberger JT, Matthews KA, Kuller LH, Wing RR, Meilahn EN, Plantinga P. Prospective study of the determinants of age at menopause. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(2):124–33.

Hardy R, Kuh D, Wadsworth M. Smoking, body mass index, socioeconomic status and the menopausal transition in a British national cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(5):845–51.

Gold EB, Bromberger J, Crawford S, Samuels S, Greendale GA, Harlow SD, et al. Factors associated with age at natural menopause in a multiethnic sample of midlife women. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(9):865–74.

Hardy R, Mishra GD, Kuh D. Body mass index trajectories and age at menopause in a British birth cohort. Maturitas. 2008;59(4):304–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.02.009.

Palmer JR, Rosenberg L, Wise LA, Horton NJ, Adams-Campbell LL. Onset of natural menopause in African American women. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):299–306.

Mishra GD, Anderson D, Schoenaker DA, Adami H-O, Avis NE, Brown D, et al. InterLACE: a new international collaboration for a life course approach to women’s reproductive health and chronic disease events. Maturitas. 2013;74(3):235–40.

Mishra GD, Chung H-F, Pandeya N, Dobson AJ, Jones L, Avis NE, et al. The InterLACE study: design, data harmonization and characteristics across 20 studies on women’s health. Maturitas. 2016;92:176–85.

World Health Organization. Obesity. Preventing and managing the global endemic. Geneva: WHO; 2000.

Borooah VK. Logit and probit: Ordered and multinomial models, vol. 138. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2002.

WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet (London, England). 2004;363(9403):157–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15268-3.

Tao X, Jiang A, Yin L, Li Y, Tao F, Hu H. Body mass index and age at natural menopause: a meta-analysis. Menopause (New York, NY). 2015;22(4):469–74. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0000000000000324.

Kershaw EE, Flier JS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2548–56. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-0395.

Mitchell M, Armstrong D, Robker R, Norman R. Adipokines: implications for female fertility and obesity. Reproduction (Cambridge, England). 2005;130(5):583–97.

Hausman GJ, Barb CR, Lents CA. Leptin and reproductive function. Biochimie. 2012;94(10):2075–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2012.02.022.

Saraç F, Öztekin K, Çelebi G. Early menopause association with employment, smoking, divorced marital status and low leptin levels. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27(4):273–8.

Sowers MR, Randolph JF, Zheng H, Jannausch M, McConnell D, Kardia SR, et al. Genetic polymorphisms and obesity influence estradiol decline during the menopause. Clin Endocrinol. 2011;74(5):618–23.

Jungari SB, Chauhan BG. Prevalence and determinants of premature menopause among indian women: issues and challenges ahead. Health Soc Work. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlx010.

Schwartz DB. Malnutrition in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Care Clin N Am. 2006;12(4):521–31.

Master-Hunter T, Heiman DL. Amenorrhea: evaluation and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73(8):1374–82.

Wing RR, Matthews KA, Kuller LH, Meilahn EN, Plantinga PL. Weight gain at the time of menopause. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(1):97–102. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1991.00400010111016.

Macdonald HM, New SA, Campbell MK, Reid DM. Longitudinal changes in weight in perimenopausal and early postmenopausal women: effects of dietary energy intake, energy expenditure, dietary calcium intake and hormone replacement therapy. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(6):669–76. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802283.

Wildman RP, Tepper PG, Crawford S, Finkelstein JS, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Thurston RC, et al. Do changes in sex steroid hormones precede or follow increases in body weight during the menopause transition? Results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):E1695–704. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-1614.

Ogden CL, Yanovski SZ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(6):2087–102. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.052.

Akahoshi M, Soda M, Nakashima E, Tominaga T, Ichimaru S, Seto S, et al. The effects of body mass index on age at menopause. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(7):961–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802039.

Rodstrom K, Bengtsson C, Milsom I, Lissner L, Sundh V, Bjourkelund C. Evidence for a secular trend in menopausal age: a population study of women in Gothenburg. Menopause (New York, NY). 2003;10(6):538–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.gme.0000094395.59028.0f.

Li L, Wu J, Pu D, Zhao Y, Wan C, Sun L, et al. Factors associated with the age of natural menopause and menopausal symptoms in Chinese women. Maturitas. 2012;73(4):354–60.

Sherman B, Wallace R, Bean J, Schlabaugh L. Relationship of body weight to menarcheal and menopausal age: implications for breast cancer risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1981;52(3):488–93. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-52-3-488.

Byrne J, Fears TR, Gail MH, Pee D, Connelly RR, Austin DF, et al. Early menopause in long-term survivors of cancer during adolescence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(3):788–93.

Liu Z, Zhang T-T, Zhao J-J, Qi S-F, Du P, Liu D-W, et al. The association between overweight, obesity and ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2015;45(12):1107–15.

Acknowledgements

The data on which this research is based were drawn from 11 observational studies. The research included data from the ALSWH, the University of Newcastle, Australia, and the University of Queensland, Australia. We are grateful to the Australian Government Department of Health for funding and to the women who provided the survey data. MCCS was supported by VicHealth and the Cancer Council, Victoria, Australia. DNCS was supported by the National Institute of Public Health, Copenhagen, Denmark. WLHS was funded by a grant from the Swedish Research Council (Grant Number 521-2011-2955). NSHD has core funding from the UK Medical Research Council (MC UU 12019/1). NCDS is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council. ELSA is funded by the National Institute on Aging (Grants 2RO1AG7644 and 2RO1AG017644-01A1) and a consortium of UK government departments. UKWCS was funded by the World Cancer Research Fund. The Whitehall II study has been supported by grants from the Medical Research Council. SMWHS was supported by grants from the National Institute for Nursing Research.

SWAN has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), DHHS, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) (Grants U01NR004061; U01AG012505, U01AG012535, U01AG012531, U01AG012539, U01AG012546, U01AG012553, U01AG012554, U01AG012495). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, NINR, ORWH or the NIH. Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor – Siobán Harlow, PI 2011 – present, MaryFran Sowers, PI 1994-2011; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA – Joel Finkelstein, PI 1999 – present; Robert Neer, PI 1994 – 1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL – Howard Kravitz, PI 2009 – present; Lynda Powell, PI 1994 – 2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser – Ellen Gold, PI; University of California, Los Angeles – Gail Greendale, PI; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY – Carol Derby, PI 2011 – present, Rachel Wildman, PI 2010 – 2011; Nanette Santoro, PI 2004 – 2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry – New Jersey Medical School, Newark – Gerson Weiss, PI 1994 – 2004; and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – Karen Matthews, PI.

NIH Program Office: National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD – Chhanda Dutta 2016 – present; Winifred Rossi 2012 – 2016; Sherry Sherman 1994 – 2012; Marcia Ory 1994 – 2001; National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, MD – Program Officers.

Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor – Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services).

Coordinating Center: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – Maria Mori Brooks, PI 2012 - present; Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, PI 2001 – 2012; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA - Sonja McKinlay, PI 1995 – 2001.

Steering Committee: Susan Johnson, Current Chair; Chris Gallagher, Former Chair

All studies would like to thank the participants for volunteering their time to be involved in the respective studies. The findings and views in this paper are not necessarily those of the original studies or their respective funding agencies.

Author’s contribution

DZ performed statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. HFC and NP harmonised the data and contributed to critical revision of the manuscript. AJD, DK, SLC, EBG, NEA, GGG, FB, HOA, EW, DCG, JEC, ESM, NFW, EJB, and MKS provided study data and contributed to critical revision of the manuscript. GDM conceptualized the study and provided critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content.

Funding

InterLACE project is funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Project Grant (APP1027196). GDM is supported by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Principal Research Fellowship (APP1121844). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, D., Chung, HF., Pandeya, N. et al. Body mass index and age at natural menopause: an international pooled analysis of 11 prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol 33, 699–710 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-018-0367-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-018-0367-y