Abstract

The global economic impact of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) on household expenditures and poverty indicators remains less well understood. To conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature evaluating the global economic impact of six NCDs [including coronary heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), cancer (lung, colon, cervical and breast), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and chronic kidney disease (CKD)] on households and impoverishment. Medline, Embase and Google Scholar databases were searched from inception to November 6th 2014. To identify additional publications, reference lists of retrieved studies were searched. Randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, cohorts, case–control, cross-sectional, modeling and ecological studies carried out in adults and assessing the economic consequences of NCDs on households and impoverishment. No language restrictions. All abstract and full text selection was done by two independent reviewers. Data were extracted by two independent reviewers and checked by a third independent reviewer. Studies were included evaluating the impact of at least one of the selected NCDs and on at least one of the following measures: expenditure on medication, transport, co-morbidities, out-of-pocket (OOP) payments or other indirect costs; impoverishment, poverty line and catastrophic spending; household or individual financial cost. From 3,241 references, 64 studies met the inclusion criteria, 75 % of which originated from the Americas and Western Pacific WHO region. Breast cancer and DM were the most studied NCDs (42 in total); CKD and COPD were the least represented (five and three studies respectively). OOP payments and financial catastrophe, mostly defined as OOP exceeding a certain proportion of household income, were the most studied outcomes. OOP expenditure as a proportion of family income, ranged between 2 and 158 % across the different NCDs and countries. Financial catastrophe due to the selected NCDs was seen in all countries and at all income levels, and occurred in 6–84 % of the households depending on the chosen catastrophe threshold. In 16 low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), 6–11 % of the total population would be impoverished at a 1.25 US dollar/day poverty line if they would have to purchase lowest price generic diabetes medication. NCDs impose a large and growing global impact on households and impoverishment, in all continents and levels of income. The true extent, however, remains difficult to determine due to the heterogeneity across existing studies in terms of populations studied, outcomes reported and measures employed. The impact that NCDs exert on households and impoverishment is likely to be underestimated since important economic domains, such as coping strategies and the inclusion of marginalized and vulnerable people who do not seek health care due to financial reasons, are overlooked in literature. Given the scarcity of information on specific regions, further research to estimate impact of NCDs on households and impoverishment in LMIC, especially the Middle Eastern, African and Latin American regions is required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Improvements in healthcare, hygiene and sanitation have increased the possibility to live until older age. Together with a growing global population, this has meant that non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), cancer, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) and chronic kidney disease (CKD), are now the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The burden exerted by NCDs extends beyond morbidity and mortality and generates an enormous societal impact, including on households and impoverishment [1–5].

Limited insurance coverage and lack of social security nets can force households of NCD patients to spend large amounts of money out-of-pocket (OOP). NCDs reduce family income, savings and consumption of non-health items, and prompt early retirement [6, 7]. The impact of NCDs on households is likely to be especially severe in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) where low-income populations, many of whom already experience extreme absolute poverty and precarious living conditions, are especially vulnerable to impoverishment due to any degree of healthcare spending [1, 8–10]. With some exceptions, such vulnerable groups suffer a double burden of chronic and infectious diseases [2, 10–13]. The interplay between exposure to disease and financial vulnerability among low-income households can drive families and societies into deeper poverty.

Despite greater appreciation on the likely deleterious role of NCDs on households and impoverishment, the extent of this impact in various geographical regions, is unclear. While several studies have addressed the issue, they have not been systematically evaluated in a single comprehensive investigation. Therefore, we report a systematic review to investigate the economic consequences of the major NCDs on the micro-economic indicators (1) at the level of households (such as consumption choices, coping strategies, OOP, direct and indirect costs) and (2) of poverty (such as financial burden, catastrophic spending, impoverishment, poverty line and financial vulnerability), across various global regions.

Methods

Conceptual framework

To guide the systematic review of the literature regarding the household impact of NCDs, a conceptual framework was adopted. This theory, previously described by McIntyre and colleagues, focuses on the economic consequences of illness and paying for health care [14]. The economic consequences that NCDs incur on the household level are preceded by levels of perceived illness and the resulting treatment seeking behaviour. Seeking care can lead to economic consequences in the form of direct (e.g. costs for hospitalization, medicines, transportation) and indirect costs (e.g. time costs of informal caregivers, time costs of the ill). The indirect costs associated with not seeking care can exert a similar burden on the microeconomic level. Economic consequences in combination with divergent coping strategies (e.g. household labour substitution, use of savings, changing consumption choices) can result in poverty.

Although the importance of the first two steps (perceived illness and treatment seeking behaviour) is conclusive, the focus of this review was on economic consequences, coping strategies and poverty.

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

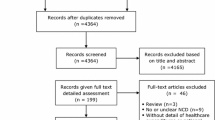

We conducted a systematic search of electronic medical databases (Medline, Embase and Google Scholar) from inception to November 6th 2014 to identify scientific articles assessing the economic consequences of NCDs on households and on impoverishment. Given their large burden in populations worldwide, the following NCDs were selected: CHD, stroke, COPD, DM, cancers (lung, colon, breast, and cervical) and CKD [1]. The step-wise inclusion and exclusion procedure outlined in Fig. 1 was followed. Eligible study designs included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), systematic reviews (used to identify further references), cohort, case–control, cross-sectional, ecological studies and modeling studies. Studies were included evaluating the impact of at least one of the selected NCDs and on at least one of the measures of interest: expenditure on medication, transport, co-morbidities, OOP or other indirect costs; consumption choices, coping strategies, impoverishment, poverty line and catastrophic spending; the household or individual financial cost. Only studies carried out in adults (>18 years old) were included and no language or date restrictions were considered. The search strategy in “Appendix 1” was applied.

Study selection

Two independent reviewers reviewed the abstracts and selected eligible studies. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved through consensus or consultation of a third reviewer. To ensure consistent application of the inclusion criteria, a sample of the full texts was reviewed by a third reviewer. The references of the retrieved studies were scanned to identify additional relevant publications that were missed by the initial search. Authors of included studies were contacted to retrieve missing full texts and to identify any missing studies.

Data extraction

A data collection form was prepared to extract the relevant information from the included full texts, including study design, World Health Organization (WHO) region, characteristics of study participants, and characteristics of the NCDs evaluated and measures included. Local currencies were converted to US dollars (USD) to enhance comparability between the eligible studies, preferably using exchange rates given by the studies, if used. If no exchange rate was given, a conversion rate of the publication year of the study was used. All USD were converted to dollars of 2013 using the consumer price index conversion factors [15].

Quality evaluation

To evaluate the quality of all studies included, the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was applied [16]. NOS scale assesses the quality of the articles in three domains of selection, comparability and exposure. Within the selection category, four items are assessed and maximum one star can be awarded to each item. Two stars can be awarded to the one item within the comparability category. Finally, one star can be awarded to each of the three items in the exposure category. A score was made by adding up the number of stars and therefore, NOS scale can have maximum nine stars for the highest quality. For cross-sectional and descriptive studies, an adapted version of NOS scale was used (“Appendix 2”).

Statistical methods

Heterogeneity permitting, we sought to pool the results using a random effects meta-analysis model. If pooled, results were expressed as the pooled estimate and the corresponding 95 % confidence intervals. All costs presented are converted in USD 2013.

Results

From 3,241 references initially identified, 64 studies met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1; Table 1) [17–80]. The eligible studies were published between 1999 and 2014, and included more than 835 million individuals.

General characteristics of the included studies

Of these 64 studies, three studies focused on multiple WHO regions, 20 studies originated from the WHO Western Pacific region and 25 from the WHO region of the Americas [22 from Canada or the United States of America (USA)]. Thirteen studies were from South-East Asia (eight from India); five studies from Europe and the African region contributed four studies. We found three studies from the Eastern Mediterranean region.

Fifty-seven studies had an observational design, of which twelve were prospective cohort studies, one was retrospective and 44 cross-sectional. One study presented a retrospective analysis of a randomized clinical trial and six were economic modeling studies. Most of the studies (51) used solely self-reported NCDs and economic measures data. Eligible participants were mostly sampled from hospitals, from disease registries or the general population. The remaining thirteen studies used data from regional, national and international databases and insurance data. In less than half of the studies, a control group was present; this was either a sample of the general population or sometimes sought within the same environment as the patients (e.g. same insurance company, same registry).

Sixteen studies focused on the impact of more than one NCD on households and impoverishment. The most frequently studied diseases were breast cancer and DM. Of the studies reporting on cancers, breast cancer was included in 21 studies, followed by colon cancer (eleven studies), lung cancer (eight studies) and cervical cancer (four studies). Two studies mentioned cancer, without specifying cancer types. DM was the NCD of interest in 21 studies, stroke in ten, CVD in eight and CKD in five studies. Three studies focused on COPD and three on NCDs in general terms.

Quality of the included studies

A quality score was appointed to all except 2 of the 64 included studies (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). In these two studies quality assessment was unfeasible due to their methodology and design. The median quality score over all the studies was 4.5 out of 9 (interquartile range 3–6). Two thirds of the eligible studies scored 5 points or less, indicating that the majority of the studies were of low or moderate quality.

Measures of economic impact on households and impoverishment

There was substantial heterogeneity among the studies in the measurement methods of the economic impact of NCDs on households and impoverishment. Therefore, pooling the outcomes of the included studies was not feasible.

For economic consequences (e.g. direct and indirect costs), OOP cost was the most common measure evaluated and was reported either as absolute costs or as a percentage of varying income proxies (e.g. individual income, family income, monthly non-food expenditure or household capacity to pay). Different OOP definitions were applied and could include the following expense types: cost of treatment or hospitalization (direct medical costs) and, among others, costs for transportation, food and lodging (referred to as direct non-medical costs or indirect costs). For catastrophic spending, mostly defined as a scenario in which OOP costs exceed a certain percentage of household income, different thresholds ranging from 10 to 40 % were used. Studies applying higher thresholds (e.g. 40 %) did not necessarily find lower percentages of households that experience financial catastrophe when compared to studies using lower thresholds (e.g. 10 %). Two other frequently reported measures of micro-economic burden were income loss and perceived financial hardship (e.g. worries about or change for the worse in financial situation), the latter capturing a different, more subjective perspective of the economic impact of NCDs on individuals and households.

Of the 64 eligible studies, five reported on the impact of NCDs on coping strategies, wherein the applied definitions differed between studies. Impoverishment was reported in three studies and was expressed as the percentage of people dropping below the 1, 1.25 or 2 USD per day poverty line due to the economic burden of treatment.

Impact of cardiovascular disease

Huffman et al. (Table 2) reported that 14.3 % of high-income families in China experienced some form of household income loss due to cardiovascular disease (CVD) hospitalization, rising to 26.3 % in India, to 63.5 % in Tanzania, and to 67.5 % in Argentina. This impact was patterned by socio-economic position, as greater household CVD-attributable income losses were reported for lower income groups [47]. In the USA, 10.4 % of CHD patients reported that OOP spending was more than 20 % of the family income [69]. CVD patients in India spent 30 % of their annual family income on direct CVD health care, where mean OOP per hospitalization increased from 364 USD in 1995–575 USD in 2004 [30, 59]. In CVD-affected households in India, >30 % borrowed or sold assets to pay for inpatient treatment, compared to 12 % in matched control households [78]. Also in India, the risk of impoverishment due to CVD was 37 % greater than for communicable diseases [95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.2–1.5] [59].

Impact of stroke

The average OOP burden as a percentage of income in Japan ranged between 5.1 and 17.2 % (Table 3) [33]. In China, OOP costs in the first 3 months after diagnosis of stroke was 158 % greater than the annual income. Catastrophic spending (e.g. OOP spending >30 % of annual income) was experienced by 71 %, pushing an estimated 23 % of insured and 62 % of uninsured stroke patients below the 1 USD per day poverty line [49]. In the USA, 27.8 % of stroke patients reported OOP spending at >20 % of the family income [69]. Among Australian stroke survivors, an estimated 473 USD were spent in the first year after diagnosis and 61 % perceived financial hardship after 12 months [57, 61].

Impact of cancer

All but five of the 28 studies reporting on cancer originated from high-income countries (Table 4). OOP spending as a percentage of annual income was estimated by two different studies at 9.7 and 44 % for breast cancer in the USA [32, 72]. In Canada, the percentage was 2.3 % [41]. In these countries, perceived financial hardship (e.g. worries about, or change for the worse in, financial situation) for breast cancer was reported by 1–92 % of women [40, 41, 52]. This perception of financial burden was experienced by 70 % of breast cancer patients in a study from Pakistan [18]. When comparing early to late expenditures for cervical cancer in Nigeria, the costs rose from 240 to 558 USD [34]. Among Norwegian women, income loss for cervical, breast, colon and lung cancer was experienced by 3.8, 5.7, 6.2 and 21.1 %, respectively. A loss in income due to cervical cancer was reported by 39 % of Argentinean women [71]. When comparing cancer to communicable diseases in India, the risk of catastrophic spending, defined as OOP costs exceeding 40 % of household income, and the risk of impoverishment was 2.7 times (95 % CI 2.1–3.1) and 2.3 times (95 % CI 1.9–2.9) higher [59].

Of the five studies focusing on coping strategies, all except one did so for the assessment of the impact of cancer [27, 64, 68, 77]. The results of a study by Chirikos and colleagues suggested that losses incurred by breast cancer patients were compensated by other individuals in the household [64]. Income and savings were used to pay for health care in up to 80 % of breast cancer patients, 10 % increased credit card debt, 7 % borrowed from friends or family and 5 % left some medical bills unpaid [77].

Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder

In Australia, financial hardship (e.g. worries about, or change for the worse in, financial situation) was felt by 36–78 % of COPD patients (Table 5) [46, 58]. Financial catastrophe, at a 10 % income threshold, was experienced by 46 % of COPD patients. In absolute terms, annual OOP expenditure among COPD sufferers was 2048 USD [58].

Impact of chronic kidney disease

57 % of Australian CKD patients reported financial hardship (Table 6). Using the same income threshold of 10 %, financial catastrophe was experienced by 71 % of CKD patients, which is equivalent in absolute terms to annual OOP expenditure of 3,755 USD [56]. In Japan, mean annual OOP expenditure was 2,604 USD [48]. OOP expenses due to CKD increased by 60 % between 2002 and 2005, and 32.6 % of CKD patients spent more than 10 % on income OOP [67, 69].

Impact of Type 2 diabetes mellitus

From the 21 studies focusing on DM, eight originated from India and showed a consistent impact on households (Table 7). Mean OOP expenditure per in-patient hospital stay for DM increased from 134 USD to 211 USD between 1995 and 2004 and direct total OOP spending per year was estimated at 262–280 USD [29, 50, 59]. The percent wise household consumption spent OOP ranged between 7.7 and 17.5 % [26, 30]. In Japan, the average OOP burden for DM, as a percentage of household income, ranged from 4.8 to 11.3 % [33].

In the USA, the mean annual OOP diabetes care cost was 1,237 USD and increased by 23 % from 2002 to 2005 [28, 67]. Nearly 40 % of DM cases in the USA experienced catastrophic spending (using the >10 % threshold); 13 % experienced catastrophic spending even above the 20 % threshold [69]. A cross-country analysis, performed by Niens et al., quantified the impoverishing effects of purchasing medicines for different diseases, including DM. Buying lowest price generic or originator brand glibenclamide would plunge either 2 million (5 %) or 3 million (10 %) chronic patients below the 1.25 USD/day poverty line, respectively. When stratifying across the 16 countries, these percentages ranged between 0 and 58 % [35].

Impact of NCDs in general terms

The proportion spent OOP on NCDs increased from 31.6 to 47.3 % between 1995 and 2004 in India (Table 8) [59]. In Japan, the average OOP burden was 2.1 % of available income [33]. The threshold for what is considered ‘catastrophic spending’ has a large impact on the proportion of households who experience it. For example, in Burkina Faso, the proportion of households experiencing catastrophic spending gradually increased from 4.5 to 10.6 % (and in absolute numbers from 79 to 108 USD annually) as the catastrophic threshold lowered, stepwise, from >60 to >40 %, >30, and >20 % [24]. The mean NCD expenditure as a proportion of household capacity to pay in Vietnam was 27.7 %. When using different catastrophic spending thresholds, nearly 60 % of the participants spent between 20 and 30 % of their income on NCDs [21].

Discussion

This systematic review summarizes 64 studies published worldwide of the impact of the major NCDs (CHD, stroke, COPD, major cancers, DM and CKD) at the micro-economic level on households and impoverishment. The studies show a steady global increase in household expenditure on NCDs between 1999 and 2014. The importance of these trends in global health is further underlined by the ‘WHO Global Action Plan for the Prevention of non-communicable diseases 2013–2020’, which highlights the need for further research into NCDs and their impact at the micro-economic level [81].

There is evidence that a substantial number of people experience financial hardship due to NCDs, as income losses affect patients and their caregivers and OOP medical expenditure for NCDs drive households into financial catastrophe and impoverishment. This rising burden is directly related to the global rise of NCDs, particularly in LMIC, many of which have under-resourced healthcare systems that impose OOP payments on individuals and households as a means to supplement other sources of revenue [1]. As healthcare systems in LMIC often experience a dual burden of infectious and chronic disease, they are less able to allocate resources towards primary prevention of NCDs. Most eligible studies used OOP expenditure to quantify the magnitude of the economic impact of NCDs on households and for mapping the extent of financial catastrophe, in particular. OOP expenditure was self-reported in most of the studies, with some exceptions where studies used health insurance claim data. Relative to different income proxies, OOP expenditure ranged widely between 2 and 158 % across different NCDs and countries.

The threshold for what is considered ‘catastrophic spending’ has a large impact on the proportion of households who experience it; depending on the income threshold taken by the study, the global proportion of households suffering from financial catastrophe ranged from 6 to 84 %. Heterogeneity in the use of an income threshold in combination with differences in study samples (among others, related to insurance coverage levels) undermine comparability across the studies, although evidence does suggest that financial catastrophe due to NCDs is an important issue for all countries and across all income strata. This observation is in accordance with other reports that took a broader (chronic) illness perspective [8, 10, 14, 82]. Variations in OOP spending and financial catastrophe across and within countries depend a great deal on the triad of factors, described by Xu and colleagues, as poverty levels, healthcare service access and use, and the presence or absence of financial risk pooling mechanisms such as health insurance or taxed-based systems [9]. Although it was outside the scope of this study to review the impact of this triad on catastrophic spending, these factors are very likely to be key components of the (varying) relation between OOP spending and catastrophic spending. Therefore, although OOP spending and financial catastrophe are valuable methodological approaches to provide insights into the impact on households, these measures cannot be interpreted without being placed within the specific health system perspective from which the sample is drawn. Standardized definitions and thresholds would facilitate unbiased and cross-country comparisons.

A minority of the studies addressed the absolute impoverishing effects of NCDs. A large study by Niens et al., in 16 LMICs, showed that the purchase of lowest price generic medication rather than originator brand DM (and other) medication could reduce absolute impoverishment, at the 1.25 USD/day poverty line, from 11 to 6 % of the total population. This finding reinforces the need to improve availability of low-priced generics, which for NCDs receives comparatively little attention compared to infectious disease treatment [83, 84].

The extent to which NCDs drive households into relative poverty were more difficult to estimate from the eligible studies, partly due to the fact that relative poverty is more difficult to measure and the definitions are less clear. We observed that some eligible studies used income losses to estimate the relative impoverishing influence of NCDs. For instance, for Norwegian women suffering from cervical, breast or lung cancer, the percent-wise income deviation compared to healthy women was 3.8, 5.7 and 20 % respectively [22]. Household income losses after CVD diagnosis were 67.5, 14.3, 26.3 and 63.5 % in high-income groups in Argentina, China, India and Tanzania respectively, and were even higher in the lower income groups [47]. These findings are consistent with similar studies, which showed that poor households are less able to cope with healthcare costs compared to more affluent households [9, 85, 86]. Solely five eligible studies provided insights in the coping strategies adopted by households to cope with a family member suffering from NCDs. The paucity of evidence regarding coping strategies, together with the significant role that illness perceiving and absence of health care seeking due to financial reasons play, are likely to reflect a considerable underestimation of the true extent to which NCDs impact households.

Findings of this systematic review generally concur with and further extend previous reviews on this topic. Previous work was focused on specific types of NCDs, was focused in specific regions of the world or provided methodological commentaries [10, 87–100]. A recent narrative review emphasized the importance of standardized definitions for OOP spending, the use of larger sample sizes and prospective study designs and a better collecting of data on economic consequences of NCDs (e.g. direct and indirect costs) [89]. Kankeu and colleagues assessed financial burden of four domains of NCDs (cancers, CVD, COPD, and diabetes) but did not include CKD in their review. In addition and interestingly, they included only studies conducted in LMICs [91]. Mahal and colleagues summarized the economic impact of NCDs for India [94]. A second study, conducted by Engelgau et al. [10], non-systematically reviewed studies mostly conducted in India. Costs involved in cancer care, without stratifying for cancer type, were reviewed in three domains in a systematic review by Pearce and colleagues. The domains included cost-effectiveness and cancer treatment, the indirect cancer costs and human costs of cancer. Definite conclusions were missing due to conceptual and methodological limitations of the included studies. Nevertheless, the complexity of the costs attached to cancer care was observed [95]. Pisu et al. [96] reviewed OOP expenses in breast cancer patients only. Tong and colleagues thematically synthesized patient and caregiver perspectives in CKD. Out of 26 included studies in this review, one study from Thailand focused on economic consequences, and found a large economic strain due to forced early retirement [97]. Coping with OOP health payments was assessed in 15 African countries and showed that borrowing and selling assets was an important coping mechanism, its prevalence ranging from 23 to 68 %. Unfortunately a specification of the included diseases was not provided [93].

The strength and limitations of our work merit careful consideration. An important strength of this review is the exhaustive search for relevant articles. We used extensive, precise search terms and applied stringent inclusion criteria, specifically the exclusion of studies focusing solely on ‘chronic diseases’ or ‘illness’. We feel that this specific approach gave rise to a comprehensive undiluted perspective of the micro-economic impact of NCDs, since all available evidence was gathered via the initial search and was supplemented by an extensive screening of reference lists for possibly missed eligible studies. However, we do emphasize that precisely defining included chronic illnesses would greatly benefit future research and the disease specific policy implications this research could give rise to.

The methods used by the eligible studies to measure household impact and impoverishment were remarkably heterogeneous which, along with a broader disease burden perspective than NCDs, is a recurrent challenge in similar reviews and did not allow us to pool the reported estimates in a meta-analysis [14, 91]. Furthermore, in many studies convenience sampling was used to assemble study samples, and the overall quality of the included studies was moderate to low. Therefore, country-wide and disease-specific implications of the results must be interpreted with caution. Given the already wide scope of our systematic evaluation, we were unable to explore wider impacts associated with NCDs such as non-economic and indirect impacts including educational dropout among children, healthcare utilization and costs of premature death. Estimation of the number and experiences of marginalized and vulnerable people who do not seek care for NCDs for financial reasons is currently neglected and their inclusion could give a more comprehensive overview of the impact of NCDs on households and impoverishment.

Conclusions

NCDs impose a large and growing global impact on households and impoverishment, in all continents and levels of income. The true extent, however, remains difficult to determine due to heterogeneity across existing studies in terms of populations evaluated, outcomes reported and measures employed. The impact that NCDs exert on households and impoverishment is likely to be underestimated since important economic domains, such as coping strategies and the inclusion of marginalized and vulnerable people who do not seek health care due to financial reasons, are overlooked in literature. Given the scarcity of information on specific regions, further research is required to estimate impact of NCDs on households and impoverishment in LMIC, especially the Middle Eastern, African and Latin American regions.

References

Alwan A. World Health Organization (WHO). Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010

Allotey P, Reidpath DD, Yasin S, Chan CK, de Graft Aikins A. Rethinking health-care systems: a focus on chronicity. Lancet. 2011;376:450–1.

Bloom DE, Cafiero ET, Jané-Llopis E, et al. The global economic burden of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Economic Forum; 2011.

Boutayeb A, Boutayeb S. The burden of non communicable diseases in developing countries. Int J Equity Health. 2005;4(1):2.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World population prospects: the 2012 revision, highlights and advance tables. Working Paper No. ESA/P/WP.228. 2013.

Bloom D, Cafiero E, McGovern M, et al. The economic impact of non-communicable disease in China and India: estimates, projections, and comparisons. PDGA Working Paper No. 107. 2013.

WHO guide to identifying the economic consequences of disease and injury. Department of Health Systems Financing. Health systems and services. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

Xu K, Evans DB, Carrin G, Aguilar-Rivera AM, Musgrove P, Evans T. Protecting households from catastrophic health spending. Health Aff. 2007;26(4):972–83. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.972.

Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray CJL. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet. 2003;362:111–7. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13861-5.

Engelgau M, Rosenhouse S, El-Saharty S, Mahal A. The economic effect of noncommunicable diseases on households and nations: a review of existing evidence. J Health Commun: Int Perspect. 2011;16(sup2):78–81.

de Graft Aikins A, Unwin N, Agyemang C, Allotey P, Campbell C, Arhinful D. Tackling Africa’s chronic disease burden: from the local to the global. Glob Health. 2010;6(1):5.

Maher D, Sekajugo J, Harries AD, Grosskurth H. Research needs for an improved primary care response to chronic non-communicable diseases in Africa. (1365-3156 (Electronic)).

Abe S. Japan’s strategy for global health diplomacy: why it matters. Lancet. 2013;382(9896):915–6.

McIntyre D, Thiede M, Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. What are the economic consequences for households of illness and of paying for health care in low- and middle-income country contexts? Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(4):858–65. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.001.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) conversion factors for years 1774 to estimated 2024 to convert to dollars of 2013. http://oregonstate.edu/cla/polisci/sites/default/files/faculty-research/sahr/inflation-conversion/pdf/cv2013.pdf. Accessed 23-04-2014.

Wells G, Shea B, O’Connel D, et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2010. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 13 Feb 2014.

Zhou B, Yang L, Sun Q, Gu H, Wang B. Social health insurance and drug spending among cancer inpatients in China. Health Aff (Proj Hope). 2008;27(4):1020–7.

Zaidi AA, Ansari TZ, Khan A. The financial burden of cancer: estimates from patients undergoing cancer care in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11(1):60. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-11-60.

Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(9):630–41.

van Houtven CH, Ramsey SD, Hornbrook MC, Atienza AA, van Ryn M. Economic burden for informal caregivers of lung and colorectal cancer patients. Oncologist. 2010;15(8):883–93. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0005.

Thuan NBT, Lofgren C, Chuc NKT, Janlert U, Lindholm L. Household out-of-pocket payments for illness: evidence from Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:283. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-283.

Syse A, Tonnessen M. Cancer’s unequal impact on incomes in Norway. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(4):480–9. doi:10.3109/0284186x.2011.640710.

Sun Q, Liu X, Meng Q, Tang S, Yu B, Tolhurst R. Evaluating the financial protection of patients with chronic disease by health insurance in rural China. Int J Equity Health. 2009;8:42. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-8-42.

Su TT, Kouyate B, Flessa S. Catastrophic household expenditure for health care in a low-income society: a study from Nouna District, Burkina Faso. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(1):21–7.

Shugarman LR, Bird CE, Schuster CR, Lynn J. Age and gender differences in Medicare expenditures at the end of life for colorectal cancer decedents. J Women’s Health. 2007;16(2):214–27. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.0012.

Shobhana R, Rama Rao P, Lavanya A, Williams R, Vijay V, Ramachandran A. Expenditure on health care incurred by diabetic subjects in a developing country—a study from southern India. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;48(1):37–42.

Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, Ramsey SD. Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: a population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1608–14.

Rodbard HW, Green AJ, Fox KM, Grandy S. Impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus on prescription medication burden and out-of-pocket healthcare expenses. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87(3):360–5. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2009.11.021.

Rayappa PH, Raju KNM, Kapur A, Bjork S, Sylvest C, Dilip Kumar KM. Economic cost of diabetes care: the Bangalore urban district diabetes study. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 1999;9:87–97.

Rao KD, Bhatnagar A, Murphy A. Socio-economic inequalities in the financing of cardiovascular & diabetes inpatient treatment in India. Indian J Med Res. 2011;133:57–63.

Ramachandran A, Ramachandran S, Snehalatha C, et al. Increasing expenditure on health care incurred by diabetic subjects in a developing country: a study from India. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(2):252–6.

Pisu M, Azuero A, Meneses K, Burkhardt J, McNees P. Out of pocket cost comparison between Caucasian and minority breast cancer survivors in the Breast Cancer Education Intervention (BCEI). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127(2):521–9. doi:10.1007/s10549-010-1225-0.

Okumura Y, Ito H. Out-of-pocket expenditure burdens in patients with cardiovascular conditions and psychological distress: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(3):233–8. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.12.013.

Obi SN, Ozumba BC. Cervical cancer: socioeconomic implications of management in a developing nation. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28(5):526–8.

Niens LM, Cameron A, Van de Poel E, Ewen M, Brouwer WBF, Laing R. Quantifying the impoverishing effects of purchasing medicines: a cross-country comparison of the affordability of medicines in the developing world. PLoS Med. 2010;. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000333.

Moore KA. Breast cancer patients’ out-of-pocket expenses. Cancer Nurs. 1999;22(5):389–96.

McKevitt C, Fudge N, Redfern J, et al. Self-reported long-term needs after stroke. Stroke. 2011;42(5):1398–403.

Markman M, Luce R. Impact of the cost of cancer treatment: an internet-based survey. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6(2):69–73.

Longo CJ, Bereza BG. A comparative analysis of monthly out-of-pocket costs for patients with breast cancer as compared with other common cancers in Ontario, Canada. Curr Oncol. 2011;18(1):e1–8.

Lauzier S, Maunsell E, Drolet M, et al. Wage losses in the year after breast cancer: extent and determinants among Canadian women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(5):321–32. doi:10.1093/jnci/djn028.

Lauzier S, Levesque P, Mondor M, et al. Out-of-pocket costs in the year after early breast cancer among Canadian women and spouses. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(4):280–92. doi:10.1093/jnci/djs512.

Lauzier S, Levesque P, Drolet M, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for accessing adjuvant radiotherapy among Canadian women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(30):4007–13.

Khowaja LA, Khuwaja AK, Cosgrove P. Cost of diabetes care in out-patient clinics of Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:189.

Kang HY, Lim SJ, Suh HS, Liew D. Estimating the lifetime economic burden of stroke according to the age of onset in South Korea: a cost of illness study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:646.

Joshi A, Mohan K, Grin G, Perin DMP. Burden of healthcare utilization and out-of-pocket costs among individuals with NCDs in an Indian setting. J Commun Health. 2013;38(2):320–7.

Jeon YH, Essue B, Jan S, Wells R, Whitworth JA. Economic hardship associated with managing chronic illness: a qualitative inquiry. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:182.

Huffman MD, Rao KD, Pichon-Riviere A, et al. A cross-sectional study of the microeconomic impact of cardiovascular disease hospitalization in four low- and middle-income countries. PLoS ONE. 2011;. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020821.

Higashiyama A, Okamura T, Watanabe M, et al. Effect of chronic kidney disease on individual and population medical expenditures in the Japanese population. Hypertens Res. 2009;32(6):450–4. doi:10.1038/hr.2009.51.

Heeley E, Anderson CS, Huang Y, et al. Role of health insurance in averting economic hardship in families after acute stroke in China. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2149–56. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.108.540054.

Grover S, Avasthi A, Bhansali A, Chakrabarti S, Kulhara P. Cost of ambulatory care of diabetes mellitus: a study from north India. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81(956):391–5.

Gordon LG, Ferguson M, Chambers SK, Dunn J. Fuel, beds, meals and meds: out-of-pocket expenses for patients with cancer in rural Queensland. Cancer Forum. 2009;33(3):204.

Gordon L, Scuffham P, Hayes S, Newman B. Exploring the economic impact of breast cancers during the 18 months following diagnosis. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16(12):1130–9. doi:10.1002/pon.1182.

Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Li H, Ratanawijitrasin S, et al. Inpatient treatment of diabetic patients in Asia: evidence from India, China, Thailand and Malaysia. Diabet Med. 2010;27(1):101–8.

Gerzeli S, Tarricone R, Zolo P, Colangelo I, Busca MR, Gandolfo C. The economic burden of stroke in Italy. The EcLIPSE Study: economic longitudinal incidence-based project for stroke evaluation. Neurol Sci. 2005;26(2):72–80. doi:10.1007/s10072-005-0439-0.

Falconer DG, Buckley A, Colagiuri R. Counting the cost of type 2 diabetes in Vanuatu. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87(1):92–7.

Essue BM, Wong G, Chapman J, Li Q, Jan S. How are patients managing with the costs of care for chronic kidney disease in Australia? A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;. doi:10.1186/1471-2369-14-5.

Essue BM, Hackett ML, Li Q, Glozier N, Lindley R, Jan S. How are household economic circumstances affected after a stroke? The psychosocial outcomes in stroke (POISE) study. Stroke. 2012;43(11):3110–3. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.112.666453.

Essue B, Kelly P, Roberts M, Leeder S, Jan S. We can’t afford my chronic illness! The out-of-pocket burden associated with managing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in western Sydney, Australia. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2011;16(4):226–31. doi:10.1258/jhsrp.2011.010159.

Engelgau MM, Karan A, Mahal A. The economic impact of non-communicable diseases on households in India. Glob Health. 2012;8:9. doi:10.1186/1744-8603-8-9.

Eaker S, Wigertz A, Lambert PC, Bergkvist L, Ahlgren J, Lambe M. Breast cancer, sickness absence, income and marital status. A study on life situation 1 year prior diagnosis compared to 3 and 5 years after diagnosis. PLoS ONE. 2011;. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018040.

Dewey HM, Thrift AG, Mihalopoulos C, et al. Lifetime cost of stroke subtypes in Australia: findings from the North East Melbourne Stroke Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Stroke. 2003;34(10):2502–7. doi:10.1161/01.str.0000091395.85357.09.

Davidoff AJ, Erten M, Shaffer T, et al. Out-of-pocket health care expenditure burden for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(6):1257–65. doi:10.1002/cncr.27848.

Chirikos TN, Russell-Jacobs A, Jacobsen PB. Functional impairment and the economic consequences of female breast cancer. Women Health. 2002;36(1):1–20.

Chirikos TN, Russell-Jacobs A, Cantor AB. Indirect economic effects of long-term breast cancer survival. Cancer Pract. 2002;10(5):248–55.

Chatterjee S, Riewpaiboon A, Piyauthakit P, Riewpaiboon W. Cost of informal care for diabetic patients in Thailand. Prim Care Diabetes. 2011;5(2):109–15.

Chang K. Comorbidities, quality of life and patients’ willingness to pay for a cure for type 2 diabetes in Taiwan. Public Health. 2010;124(5):284–94. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2010.02.019.

Campbell RS, Patel V, Gleeson M, Calimlim BM, Zagari MJ, Curkendall SM. Out-of-pocket healthcare expenditures and caps in patients with chronic conditions. Am J Pharm Benefits. 2011;3(2):98–105.

Bennett JA, Brown P, Cameron L, Whitehead LC, Porter D, McPherson KM. Changes in employment and household income during the 24 months following a cancer diagnosis. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(8):1057–64.

Banthin JS, Bernard DM. Changes in financial burdens for health care: national estimates for the population younger than 65 years, 1996 to 2003. JAMA. 2006;296(22):2712–9. doi:10.1001/jama.296.22.2712.

Baanders AN, Heijmans MJ. The impact of chronic diseases: the partner’s perspective. Fam Community Health. 2007;30(4):305–17.

Arrossi S, Matos E, Zengarini N, Roth B, Sankaranayananan R, Parkin M. The socio-economic impact of cervical cancer on patients and their families in Argentina, and its influence on radiotherapy compliance. Results from a cross-sectional study. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105(2):335–40. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.12.010.

Arozullah AM, Calhoun EA, Wolf M, et al. The financial burden of cancer estimates from a study of insured women with breast cancer. J Support Oncol. 2004;2(3):271–8.

Bernard DM, Banthin JS, Encinosa WE. Health care expenditure burdens among adults with diabetes in 2001. Med Care. 2006;44(3):210–5. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000199729.25503.60.

Chang S, Long SR, Kutikova L, et al. Estimating the cost of cancer: results on the basis of claims data analyses for cancer patients diagnosed with seven types of cancer during 1999 to 2000. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(17):3524–30. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.10.170.

Dewey HM, Thrift AG, Mihalopoulos C, et al. ‘Out of pocket’ costs to stroke patients during the first year after stroke—results from the North East Melbourne Stroke Incidence Study. J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11(2):134–7.

Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Whelan T, et al. Family caregiver burden: results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. Can Med Assoc J. 2004;170(12):1795–801.

Jagsi R, Pottow JAE, Griffith KA, et al. Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(12):1269–76. doi:10.1200/jco.2013.53.0956.

Karan A, Engelgau M, Mahal A. The household-level economic burden of heart disease in India. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(5):581–91. doi:10.1111/tmi.12281.

Kelley AS, McGarry K, Fahle S, Marshall SM, Du Q, Skinner JS. Out-of-pocket spending in the last five years of life. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):304–9. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2199-x.

Riewpaiboon A, Riewpaiboon W, Ponsoongnern K, Van den Berg B. Economic valuation of informal care in Asia: a case study of care for disabled stroke survivors in Thailand. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(4):648–53. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.033.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Van Doorslaer E, O’Donnell O, Rannan-Eliya R, et al. Paying out-of-pocket for health care in Asia: catastrophic and poverty impact. EQUITAP Project: working paper #2, Erasmus University, Rotterdam and IPS, Colombo. 2005.

Mendis S, Fukino K, Cameron A, et al. The availability and affordability of selected essential medicines for chronic diseases in six low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:279–88. doi:10.2471/BLT.06.033647.

Cameron A, Ewen M, Ross-Degnan D, Ball D, Laing R. Medicine prices, availability, and affordability in 36 developing and middle-income countries: a secondary analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:240–9. doi:10.1016/S01406736(08)61762-6.

Wagstaff A. Poverty and health sector inequalities. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(2):97–105.

WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Noncommunicable disease and poverty: the need for pro-poor strategies in the Western Pacific region: a review. World Health Organization; 2006.

Brooks J, Wilson K, Amir Z. Additional financial costs borne by cancer patients: a narrative review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(4):302–10. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2010.10.005.

Girgis A, Lambert S, Johnson C, Waller A, Currow D. Physical, psychosocial, relationship, and economic burden of caring for people with cancer: a review. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(4):197–202. doi:10.1200/jop.2012.000690.

Goryakin Y, Suhrcke M. The prevalence and determinants of catastrophic health expenditures attributable to non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: a review-based commentary on the methodological challenges involved. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13(1):107. doi:10.1186/s12939-014-0107-1.

Haley WE. The costs of family caregiving: implications for geriatric oncology. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;48(2):151–8.

Kankeu HT, Saksena P, Xu K, Evans DB. The financial burden from non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: a literature review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:31.

Kim P. Cost of cancer care: the patient perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(2):228–32. doi:10.1200/jco.2006.07.9111.

Leive A, Xu K. Coping with out-of-pocket health payments: empirical evidence from 15 African countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(11):849–56.

Mahal A, Karan A, Engelgau M. The economic implications of non-communicable disease for India. Health, Nutrition and Population (HNP) Discussion Paper. The World Bank. 2010.

Pearce S, Kelly D, Stevens W. ‘More than just money’—widening the understanding of the costs involved in cancer care. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33(3):371–9.

Pisu M, Azuero A, McNees P, Burkhardt J, Benz R, Meneses K. The out of pocket cost of breast cancer survivors: a review. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4(3):202–9. doi:10.1007/s11764-010-0125-y.

Tong A, Cheung KL, Nair SS, Kurella Tamura M, Craig JC, Winkelmayer WC. Thematic synthesis of qualitative studies on patient and caregiver perspectives on end-of-life care in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(6):913–27. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.11.017.

Valtorta NK, Hanratty B. Socioeconomic variation in the financial consequences of ill health for older people with chronic diseases: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2013;74(4):313–33.

Wagner L, Lacey MD. The hidden costs of cancer care: an overview with implications and referral resources for oncology nurses. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2004;8(3):279–87. doi:10.1188/04.cjon.279-287.

Yabroff KR, Borowski L, Lipscomb J. Economic studies in colorectal cancer: challenges in measuring and comparing costs. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2013;2013(46):62–78. doi:10.1093/jncimonographs/lgt001.

Acknowledgments

Completion of this manuscript was supported by a Grant from the WHO. O.H. Franco and L. Jaspers work in ErasmusAGE, a center for aging research across the life course funded by Nestlé Nutrition (Nestec Ltd.); Metagenics Inc.; and AXA. Nestlé Nutrition (Nestec Ltd.); Metagenics Inc.; and AXA had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript. V. Colpani is a visiting researcher supported by CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior), in Brazil. Dr. Shanthi Mendis from the WHO and co-author on this manuscript participated in the interpretation and preparation of this manuscript. The manuscript was approved by the WHO for submission.

Conflict of interest

With regard to potential conflicts of interest, there is nothing to disclose. Drs. Jaspers, Colpani and Franco had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Loes Jaspers and Veronica Colpani have contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Search strategy 6 November 2014

(‘non communicable disease’/de OR ‘ischemic heart disease’/exp OR ‘cerebrovascular accident’/exp OR ‘chronic obstructive lung disease’/de OR ‘lung cancer’/exp OR ‘colon cancer’/exp OR ‘breast cancer’/exp OR ‘chronic kidney disease’/de OR ‘non insulin dependent diabetes mellitus’/de OR ‘uterine cervix cancer’/exp OR (‘non communicable’ OR noncommunicable OR ((heart OR cardiac OR cardial OR cardiopath* OR cardiomyopath* OR coronar* OR myocard*) NEAR/3 (ischem* OR ischaem* OR anoxia OR hypoxia)) OR (coronary NEAR/3 (insufficien* OR occlus* OR disease* OR acute OR atherosclero* OR arteriosclero* OR sclero* OR cardiosclero* OR constrict* OR vasoconstrict* OR obstruct* OR stenosis* OR thrombo*)) OR angina* OR ((heart OR myocard* OR cardiac OR cardial) NEAR/3 infarct*) OR ((cerebrovascul* OR brain OR ‘cerebral vascular’ OR ‘cerebro vascular’) NEAR/3 (accident* OR lesion* OR attack OR ischem* OR ischaem* OR insult* OR insuffucien* OR arrest* OR apoplex*)) OR cva OR stroke OR (chronic AND (obstruct* NEAR/3 (lung* OR pulmonar* OR airway* OR bronch* OR respirat*))) OR ((lung* OR pulmonar* OR colon* OR colorect* OR breast* OR mamma*) NEAR/3 (neoplas* OR cancer* OR carcino* OR adenocarcino* OR metasta* OR sarcom*)) OR (chronic NEAR/3 (kidney* OR nephropathy* OR renal)) OR ((‘adult onset’ OR ‘type 2’ OR ‘type ii’ OR ‘non-insulin dependent’ OR ‘noninsulin dependent’ OR ‘insulin independent’) NEAR/3 diabet*) OR ((cervix OR cervical) NEAR/3 (cancer* OR neoplas* OR tumo* OR carcinom* OR malign*))):ab,ti) AND (adult/exp) AND (‘randomized controlled trial’/exp OR ‘cohort analysis’/de OR ‘case control study’/exp OR ‘cross-sectional study’/de OR ‘systematic review’/de OR ‘meta analysis’/de OR ecology/exp OR ‘ecosystem health’/exp OR ‘ecosystem monitoring’/exp OR model/exp OR ((random* NEAR/3 (trial* OR control*)) OR rct* OR cohort* OR ‘case control’ OR ‘cross-sectional’ OR (systematic* NEAR/3 review*) OR metaanaly* OR (meta NEXT/1 analy*) OR ecolog* OR ecosystem* OR model*):ab,ti) NOT ([animals]/lim NOT [humans]/lim) NOT ([Conference Abstract]/lim OR [Conference Paper]/lim OR [Letter]/lim OR [Note]/lim OR [Conference Review]/lim OR [Editorial]/lim OR [Erratum]/lim).

AND (((‘cost of living’/de OR budget/de OR ‘financial deficit’/exp OR income/de OR ‘health care cost’/de OR ‘hospitalization cost’/de OR insurance/exp OR ‘cost of illness’/de OR socioeconomics/exp OR (((cost* OR econom* OR expen*) NEAR/6 (living OR individu* OR famil* OR personal* OR patient* OR illness* OR direct* OR indirect*)) OR budget* OR deficit* OR debt* OR income OR insurance* OR socioeconom* OR pover* OR impover* OR poor OR wealth):ab,ti) AND (family/exp OR home/de OR household/de OR (famil* OR home OR household* OR personal):ab,ti)) OR ‘caregiver burden’/de OR (microeconom* OR (micro NEXT/1 econom*) OR ‘Out of pocket’ OR ‘Willingness to pay’ OR (catastroph* NEAR/3 (spend* OR expend*)) OR ‘Poverty line’ OR (Value* NEXT/2 ‘statistical life’)):ab,ti).

Appendix 2: Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale, cross-sectional and descriptive studies

Note: A study can be awarded a maximum of one star for each numbered item within the Selection and Exposure categories. A maximum of two stars can be given for Comparability.

Selection

-

1.

Is definition of NCDs adequate?

-

(a)

Yes, according to a clear and widely used definition*

-

(b)

Yes, e.g. record linkage or based on self-reports

-

(c)

No description

-

(a)

-

2.

Representativeness of the cases

-

(a)

Consecutive or obviously representative series of cases*

-

(b)

Excluded cases are random*

-

(c)

No description of the excluded cases or potential for selection biases or not stated

-

(a)

-

3.

Comparison with a reference group

-

(a)

The results are compared with a reference from community or with the status of the cases prior to the disease*

-

(b)

The results are compared with the results from other patients

-

(c)

No description/no comparison available

-

(a)

-

4.

Definition of reference

-

(a)

Individuals with no NCD or sample from general population or the same individuals before NCD suffering*

-

(b)

Non community comparator is described

-

(c)

No description of source

-

(a)

Comparability

-

1.

Comparability of the results on the basis of the design or analysis

-

(a)

The results are described in age and sex sub groups (sex is not applicable for female diseases)*

-

(b)

The results are additionally adjusted for/described in different socioeconomic factors or disease related confounders*

-

(a)

Exposure (costs, productivity, households)

-

1.

Ascertainment of exposure

-

(a)

Secure record (e.g. surgical records, hospital records, and administrative records, national…)*

-

(b)

Structured interview where blind to case/control status*

-

(c)

Interview not blinded to case/control status

-

(d)

Written self-report or medical record only

-

(e)

No description

-

(a)

-

2.

Same method of ascertainment for NCDs and comparators

-

(a)

Yes*

-

(b)

No

-

(c)

No comparator group exist

-

(a)

-

3.

Non-Response rate

-

(a)

All participants included or same rate for both groups or respondents and non-respondents have the same characteristics*

-

(b)

Non respondents described

-

(c)

Rate different and no designation

-

(d)

Response rate not described

-

(a)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jaspers, L., Colpani, V., Chaker, L. et al. The global impact of non-communicable diseases on households and impoverishment: a systematic review. Eur J Epidemiol 30, 163–188 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-014-9983-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-014-9983-3