Abstract

Coal is the most aggressive energy sources in the environment. Several adverse outcomes on children’s health exposure to coal pollutants have been reported. Pollutants from coal power plants adversely affect the intellectual development and capacity. The present study aimed to evaluate the intellectual development and associated factors among children living a city under the direct influence (DI) and six neighboring municipalities under the indirect influence (II) of coal mining activity in the largest coal reserve of Brazil. A structured questionnaire was completed by the child’s guardian, and Raven's Progressive Color Matrices were administered to each child to assess intellectual development. A total of 778 children participated. In general, no significant difference was observed between the two cities. The DI city had better socioeconomic conditions than the II municipalities according to family income (< 0.001). The prevalence of children who were intellectually below average or with intellectual disabilities was 22.9%, and there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) between municipalities. In both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, intellectual development was associated with maternal age, marital situation and maternal education level, birth weight, breast feeding, frequent children's daycare, paternal participation in children’s care and child growth. Living in the DI area was not associated with intellectual disability. The results suggest that socioeconomic conditions and maternal and neonatal outcomes are more important than environmental factors for intellectual development of children living in a coal mining area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coal is the world’s most polluting fossil fuel, due the large amounts of coal dust particles are emitted to the environmental from the extraction and combustion (World Energy Council 2016; Landrigan et al. 2018). Coal consists of a mixture of substances including carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, small mineral particles, quartz (crystalline silica) and other chemical compounds (Chen et al. 2004). Coal combustion releases 84 compounds listed as “hazardous air pollutants” by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA Agency Environmental Protection 2016). Coal-fired thermoelectric plants generate environmental contamination in each step of coal activities, which can represent a health risk (Gorriz et al. 2002; Rodriguez-iruretagoiena et al. 2015), especially for vulnerable groups such as children under 15 years old (Cortés et al. 2019). Exposure to pollutants in pediatric populations is worrisome because their anatomy, physiology, and neurologic and metabolic systems are developing. Additionally, children are unable to recognize environmental hazards (Amster and Levy 2019).

Several researchers have demonstrated adverse outcomes on children’s health exposure to coal pollutants, such as birth outcomes, respiratory disease, gastrointestinal problems, multiple sleep problems and mortality (Ahern et al. 2011a, b; Ha et al. 2015; Lamm et al. 2015; Victora et al. 2015; Sears and Zierold 2017; Kravchenko and Lyerly 2018). Additionally, evidence suggests that pollution exposure may be associated with neurological function (Xu et al. 2016; Emerson et al. 2018). Pollutants from coal power plants adversely affect the intellectual development and capacity of children living in the region (Tang et al. 2008; Dupont-soares et al. 2015; Cortés et al. 2019). When pollutant levels are reduced, improvements in neurodevelopment are observed (Tang et al. 2014; Kalia et al. 2017).

In recent years, various factors have been associated with children's intellect, such as living in more socioeconomically deprived areas (Emerson 2012; Noble et al. 2015) where higher levels of air pollutants are typically more common (Royal College of Physicians 2016). Kravchenko (2017) reported that children exposed prenatally to coal ash had decreased motor, language and social development later in childhood. Additionally, more frequent emotional, behavioral and learning disorders, as well as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, were observed than children living far from these coal power plants (Tang et al. 2008, 2014; Sears and Zierold 2017; Cortés et al. 2019).

In the US, it is estimated that the aggregate cost of environmentally mediated diseases among children is $76.6 billion (Trasande and Liu 2011). The public health impact of coal-based energy production on children is a concern. Worldwide, more than 1600 coal-fired power plants are either under construction or planned. Consequently, the negative impact of coal emissions on child health will likely increase and continue to be a significant public health concern (Amster and Levy 2019). Several studies carried out on the largest Brazilian coal mining have shown negative impact of coal on human health (Pinto et al. 2017; da Silva Júnior et al. 2018; Santos et al. 2018, 2019; Bigliardi et al. 2020).

The Brazilian coal reserve has approximately 7 million tons (Energy Information Administration 2020). The largest national reserve is located in the southern region of the country, in Candiota city, where one coal-fired power plant, and two coal surface-mining operators are located (Migliavacca et al. 2004). This region has become a model for studying the effects of exposure to coal by-products, due to having approximately 40% of Brazil's coal reserves and in a sparsely populated and socioeconomically vulnerable region (Bigliardi et al. 2020). Therefore, considering this context of environmental pollution associated with the risk to adverse intellectual capacity in the pediatric population, this study aimed to evaluate maternal, neonatal and socio-economic factors associated with intellectual development among children living in Candiota and neighboring municipalities.

Methods

Study area

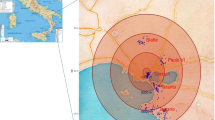

This cross-sectional study was conducted in seven cities in the state of Rio Grande do Sul–Brazil (Fig. 1) (Pinto et al. 2017). The direct influence (DI) of coal mining activity is concentrated in Candiota (31°33′28″S/53°40′22"W), where a power plant and two coal surface mines are situated. Six neighboring municipalities, Aceguá (31°52′S 54°09′W), Bagé (31°19′51"S 54°06′25"W), Hulha Negra (31°24′14"S 53°52′08"W), Pedras Altas (31°43′58"S 53°35′02"W), Pinheiro Machado (31°34′40"S 53°22′51"W), and Herval (32°01′26"S 53°23′45"W), are indirectly influenced (II) by coal mining activity due to their proximity to Candiota and wind dispersion.

Map of the state of Rio Grande do Sul highlighting the cities involved in the study (Pinto et al. 2017)

Sample and data collection

A random sampling process was conducted from the list of education departments from each city, according to the geographical representation of all municipalities from rural and urban zones, the proportionality of total number of students enrolled in the school and their distribution in the age group of interest (children aged 6 years to 11 years and 11 months). The sample included all public schools in the area (51 schools) and 778 students (6 schools and 78 children in DI and 45 schools and 700 children in II). Twinning and schoolchildren who had malformations, genetic syndromes or cognitive disabilities were excluded.

A structured questionnaire to collect socioeconomic and demographic information was applied in the child’s guardian. The questionnaire also included information on prenatal and postnatal care, neonatal outcomes, children’s development and morbidity. Children were weighed with a digital balance scale with increments of 0.1 kg. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using tape on the wall within 50.0 cm of the floor. The children were measured while wearing light clothing and no shoes. Child growth was classified according to the World Health Organization (2007) height-for-age (HA), determined by the z score (≥−2.00 adequate and ≥ −3.00 to <−2.00 inadequate nutritional status).

To assess intellectual development, a trial test, Raven's Progressive Color Matrices (Angelini et al., 1988), was used. This test is indicated to assess intellectual development in school and validated and standardized to Brazilian population. It comprises three series of 12 items: A, Ab, and B. The items are arranged in ascending order of difficulty in each series, and each series is more difficult than the previous one. Items are composed of a drawing or matrix with a part missing below which six alternatives are presented, one of which correctly completes the matrix. The examinee must choose one of the alternatives to complete the missing part (Bandeira et al. 2004). This evaluation was carried out by a psychologist and the application time was approximately 20 to 30 min. All data were collected in the same school and shift of activities of the students, in classrooms or in specific rooms available.

After the application of the Raven Color Progressive Matrices Scale, the answers were classified according to the standardization determined in the scale's prerogatives. The results were expressed in percentiles, and suspicion of intellectual development impairment was classified as a total percentile score less than 49. This value is established as a median and reveals the individual's position in relation to the group where it is inserted, which may indicate the degree of intellectual development (Angelini et al., 1988).

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards proposed by Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council of the Ministry of Health, which regulates research involving human subjects. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee in Health at the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande-FURG (CEPAS/FURG no° 36/2015).

Statistical analysis

The sample size was defined considering an alpha error of 0.05, relative risk of 2.0 and power of 80%. The prevalence of intellectual impairment is 28.9% (Dupont-soares et al. 2015). Ten percent was added for losses, 20% for possible confounding factors and 20% for design purposes. Thus, the sample size should be 758 children. The data were duplicate digitalized, checked and corrected for possible errors. Additionally, the consistency of the data was evaluated. First, frequency distribution was performed to describe the variables investigated. In descriptive analysis was excluded 59 siblings to avoid overestimating sample characterization; thus, the variables referring socioeconomic characteristics and maternal outcomes were separately analyzed, including a total of 685 family's information. A Chi-square test was applied to verify the statistical difference between the two areas. To estimate the crude and adjusted prevalence ratios and their respective confidence intervals (95%) as well as the p value, Poisson regression with robust variance estimates was used to analyze the outcome and associated factors. To avoid confounding factors, variables that presented p ≤ 0.20 were maintained in the model until the end. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 10.0. Statistical significance was established at p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 778 children participated, including both boys and girls. In general, no significant difference was observed between the DI city and the II municipalities by maternal outcomes (Table 1). Most mothers were more than 35 years old (49.6%), Caucasian (56.2%), married (80.1) and had 4 to 8 years of education (54.2). In both the DI city and the II municipalities, most families had more than two children, and 20.6% had experienced a previous child’s death. More than half of this population (61.9%) had low family income (< 385.00 R$). In addition, the DI city had better socioeconomic conditions than the II municipalities according to family income (< 0.001).

Approximately one-third of mothers (33.7%) reported smoking during pregnancy, and 1.7% mentioned no prenatal care. The DI city had a significantly higher prevalence of cesarean delivery (51.9%) compared to the II municipalities (37.9%). Approximately 12% of neonates were born preterm and weighed less than 2.500 g (11.6%), and 8.0% needed ventilatory assistance (Table 2).

A total of 72 children (9.3%) were not breastfed, whereas the majority were breastfed for more than six months (55.1%). In general, the children did not attend day care centers (63.5%). Children from II municipalities were more exposed to passive smoking (49.8%) than those from the DI city (29.6%) (p = 0.01). Additionally, mothers from II municipalities reported lower participation by fathers in children’s care (24.7%) than those in the DI city (17.7%) (p < 0.001). Most of the children had pets (86.7%). Only 1.5% of the children had chronic disease, 44.9% had previous hospitalization, and 2.1% had inadequate growth (Table 3).

According to Raven's Colored Progressive Matrices, 178 (22.9%) children were intellectually below average. Most cases were identified in II municipalities (93.3%), without a significant statistic (p = 0.5). Figure 2 shows the prevalence of suspicion of intellectual development impairment in both areas.

Table 4 shows the significant variables associated with intellectual development. In both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, mothers who were 35 years old or older (OR = 0.79; p < 0.001), unmarried (OR = 1.18; p = 0.04) and with less than 4 years of education (OR = 2.26; p < 0.001) remained significant. Family income per capita and skin color lost statistical significance in the adjusted analyses. Living in the area under DI was not associated with intellectual development. Birth type, gestational age and birth weight were significantly associated only in the unadjusted analysis. Cesarean delivery represents protection of intellectual development (OR = 0.61; p = < 0.001) and there is a risk of approximately 30% to intellectual development among neonatal who born preterm and birth weigh less than < 2500 g. While the need of ventilatory assistance in neonatal represent neonates represented protection (OR = 0.69; p < 0.001) in the adjusted analysis. Children who were not breastfed and did not attend day care centers had a 94% and 29% higher risk of intellectual development, respectively. Additionally, children whose fathers had low participation in the children’s care had a 7% higher risk of intellectual development. Finally, children with inadequate growth had a 75% higher risk of intellectual development (OR = 1,75; p < 0,00). Other variables did not show an association with the outcome studied in either unadjusted or adjusted analyses.

Discussion

This study evaluated the association of socioeconomic, maternal and neonatal outcomes with intellectual development among children living in municipalities under DI and II of coal mining activity. The suspicion of intellectual development impairment was higher in II municipalities, without significance. Intellectual development was associated in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses with maternal age, marital situation and maternal education level. Preterm birth, birth weight less than < 2500 g, no breastfeeding, no day care, low participation of the father in children’s care and inadequate growth represented risks for intellectual development. However, living in areas under DI was not associated with poor intellectual development.

There are many socioeconomic and demographic variables associated with intellectual capacity. Advanced maternal age (> 35 years) is considered a risk for several adverse neonatal outcomes, and these children are more likely to have intellectual disability (Tearne 2015; Huang et al. 2016). However, new evidence indicates that the relationship between maternal age and child intellectual development is still controversial (Rubenstein et al. 2019). In this study, maternal age represented a protective factor against intellectual development, which could be related to a better family environment (Bear 2004).

Children of single mothers were at risk of intellectual development. Families composed of mothers and partners represent a better family environment that is positive for children's cognitive development (Andrade et al. 2005). Additionally, confirming our results, a recent cohort study in the US reported that children with mothers who had a college degree of higher were least likely to have adverse intellectual outcomes (Fonseca et al. 2013; Harding 2015; Zablotsky et al. 2019). Parents with higher education levels expose their children to different stimuli, which enhance the child's development (Paula et al. 2002).

There is a high prevalence of families living in socioeconomic vulnerability in the study region, and most families lived on less than one minimum wage. Coal activity provides an important economic contribution to this region. II municipalities have worse socioeconomic conditions than the DI city, highlighting the economic importance of coal activity. Socioeconomic status influences the population’s health and susceptibility to the adverse effects of air pollution (Lima-Costa et al. 2003; Inoue et al. 2014; Emerson et al. 2018). Although socioeconomic conditions are considered an important indicator of cognitive development (Macedo and Andreucci 2004), low family income represents a risk of intellectual development only in the unadjusted analysis.

This study observed a high prevalence of smoking during gestation and children’s exposure to passive smoking. These situations represent a significantly higher risk of intellectual development among children. Maternal smoking during pregnancy was previously associated with a decline in child intelligence and memory (Boucher et al. 2012) as well as cognitive problems and brain dysfunctions (Marroun et al. 2013). Other studies emphasize that children exposed to passive smoking are more likely to have difficulties expressing nonverbal reasoning and intellectual disabilities (Alwis et al. 2015; Emerson et al. 2016; Xu et al. 2016).

The DI city had significantly more cesarean delivery births than the II municipalities, which may be related to better socioeconomic conditions. However, cesarean birth delivery represents protection to intellectual development in the unadjusted analysis. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have associated cesarean delivery births with autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, irrespective of the cesarean delivery modality, compared with vaginal delivery (Zhang et al. 2019).

The prevalence of low birth weight was similar between both regions and represents a significant risk to intellectual development. Kwinta et al. (2012) observed abnormal motor capacity and learning and concentration problems in children with low birth weight (Kwinta et al. 2012). Living in coal mining areas has been associated with low and very low birth weight, preterm gestation and other negative outcomes (Ahern et al. 2011b; Cortes-Ramirez et al. 2018; Amster and Levy 2019).

Almost 10% of mothers in the study did not breastfeed their children, and an important portion of mothers stopped breastfeeding before 6 months. Breastfeeding has clear short-term benefits for children and has been associated with better intellectual development (Kramer and Kakuma 2012; Fonseca et al. 2013; Belfort et al. 2014). Additionally, appropriately breastfed children had better performance in intelligence tests 30 years later, which might suggest an increase in educational level and income in adulthood (Victora et al. 2015).

Children who did not attend day care centers and had lower paternal care participation were at risk of intellectual development. The involvement of fathers in child care has increased in recent years and has been associated with better socioemotional and cognitive development of the child (Redshaw and Henderson 2013). Similarly, children's daycare attendance has been associated with positive language development, and adequate communication contributes to children’s cognitive development (Cachapuz et al. 2006). Children who receive greater care, whether by parents or caregivers, have better development of their abilities, especially with regard to linguistics (Manso and Alonso 2008).

Children’s nutritional status influences their survival, cognitive development and lifelong health. Inadequate child growth, measured by height-for-age, is an indicator of overall nutritional status. The global prevalence of inadequate child growth is approximately 7.7% (Stevens et al. 2016). Linear growth failure serves as a marker of multiple pathological disorders associated with increased morbidity and mortality, loss of physical growth potential, reduced neurodevelopmental and cognitive function and an elevated risk of chronic disease in adults (Onis and Branca 2016). Corroborating the findings of our study that inadequate child growth represents an important risk to intellectual development, and some researchers indicate that there is a reduction in intellectual capacity due inadequate nutrition status (Liu and Raine 2017).

Intellectual development is a complex and multifactorial outcome. The Raven Colored Progressive Matrices is a measure of reasoning ability that is often used to evaluated suspicion of intellectual development impairment among children in research studies. It is nonverbal and easily and quickly applied (Fonseca et al. 2013; Goharpey et al. 2013). Despite the limitation of this study used only one test to measure the intellectual capacity, it is a validated and standardized test for Brazilian population (Cardoso et al. 2017). The prevalence of suspicion of intellectual development impairment was higher than that observed by Fonseca et al. (2013) (7.7%) in a nearby city with better socioeconomic characteristics than the study region. When the results were compared with schoolchildren of the same age group living in other Brazilian cities with high levels of environmental contamination (Macedo and Andreucci 2004; Dupont-soares et al. 2015), children from this coal area seem to have worst intellectual development than that in other cities.

There was no significant difference between intellectual development among DI and II. Additionally, living in the DI city did not represent a risk of intellectual development. Similarly, Amers et al. (2019) did not find an association between the distance of residence to coal-fired power plants and adverse birth outcomes. After the closure of a coal power plant in China, molecular and neurodevelopmental benefits to children of this region were observed (Tang et al. 2014).

The study region has five air pollutant monitoring stations, and the study of Bigliardi et al. (2020) showed that the average annual concentration of PM10, NO2 and SO2 did not exceed the Brazilian (CONAMA 2018) and WHO (World Health Organization 2006) limits. Furthermore, studies have pointed out that there are no notable differences in the levels of air pollutants between Candiota and the other municipalities in the study region (Bigliardi et al. 2020; Da Silva Júnior et al. 2020). Interestingly, these studies in the region have pointed out that health outcomes are not worse in the host city for coal activities. In general, health outcomes are similar in all municipalities in the region or worse in some cities of indirect influence. In this sense, socioeconomic factors and health conditions seem to have a predominant influence on this population.

Conclusion

This is the first study to examine intellectual development in children living in the largest coal mining region of Brazil. The results suggest that socioeconomic, maternal and neonatal outcomes might be more important to intellectual development than environmental factors since living in the DI city did not represent a risk to the outcome. The study highlights the importance of socioeconomic and maternal outcomes as confounder’s factors in studies that evaluate the impact of environmental exposure in this population. Public health actions are needed to improve socioeconomic status, which is directly associated with intellectual development in this region. Furthermore, it is necessary to consistently control and monitor child health in vulnerable environmental conditions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahern, M., Hendryx, M., Conley, J., et al. (2011a). The association between mountaintop mining and birth defects among live births in central Appalachia, 1996–2003. Environmental Research, 111, 838–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2011.05.019.

Ahern, M., Mullett, M., MacKay, K., & Hamilton, C. (2011b). Residence in coal-mining areas and low-birth-weight outcomes. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15, 974–979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-009-0555-1.

Alwis D De, Tandon M, Tillman R, Luby J (2015) HHS Public Access

Amster E, Levy CL (2019) Impact of Coal-fired Power Plant Emissions on Children’s Health: A Systematic Review of the Epidemiological Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 1–11

Andrade, S. A., Santos, D. N., Bastos, A. C., et al. (2005). Family environment and child’s cognitive development: An epidemiological approach. Revista de Saude Publica, 39, 4–9.

Bandeira, D. R., Alves, I. C., Giacomel, A. E., et al. (2004). The raven’s coloured progressive matrices: Norms for Porto Alegre, RS. Psicol Estud, 9, 479–486.

Bear, L. M. (2004). Early identification of infants at risk for developmental disabilities. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 51, 685–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2004.01.015.

Belfort MB, Rifas-shiman SL, Kleinman KP, et al (2014) NIH Public Access. 167:836–844. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.455.Infant

Bigliardi, A. P., Fernandes, C. L. F., Pinto, E. A., et al. (2020). Blood markers among residents from a coal mining area. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-10400-3.

Boucher, O., Jacobson, S. W., Plusquellec, P., et al. (2012). Prenatal Methylmercury, Postnatal Lead Exposure, and Evidence of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder among Inuit Children in Arctic Québec. Environmental Health Perspectives, 1456, 1456–1461.

Cachapuz, R. F., Especialista, C. U., Halpern, R., et al. (2006). Influência das variáveis ambientais no desenvolvimento da linguagem em uma amostra de crianças. Rev Assoc Med Rio Grande Do Sul, 50, 292–301.

Cardoso, L. M., Lopes, É. I. X., de Oliveira, J. C., & Braga, A. P. (2017). Análise da Produção Científica Brasileira sobre o Teste das Matrizes Progressivas de Raven. Psicol Ciência e Profissão, 37, 62–77. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-3703000212015.

Chen, Y., Shah, N., Huggins, F. E., et al. (2004). Investigation of primary fine particulate matter from coal combustion by computer-controlled scanning electron microscopy. Fuel Processing Technology, 85, 743–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2003.11.017.

CONAMA (2018) Resolução no 491/18 de 18 de novembro de 2018. 7

Cortes-Ramirez, J., Naish, S., Sly, P. D., & Jagals, P. (2018). Mortality and morbidity in populations in the vicinity of coal mining: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5505-7.

Cortés AS, Yohannessen VK, Tellerías LC, Ahumada EP (2019) Exposición a contaminantes provenientes de termoeléctricas a carbón y salud infantil: ¿ Cuál es la evidencia internacional y nacional? Revista Chilena de Pediatría 90:102–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.32641/rchped.v90i1.748

Ćujić, M., Dragović, S., Dordević, M., et al. (2016). Environmental assessment of heavy metals around the largest coal fired power plant in Serbia. CATENA, 139, 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2015.12.001.

da Silva Júnior, F. M. R., Ramires, P. F., dos Santos, M., et al. (2019). Distribution of potentially harmful elements in soils around a large coal-fired power plant. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 41, 2131–2143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-019-00267-w.

da Silva Júnior, F. M. R., Tavella, R. A., Fernandes, C. L. F., et al. (2018). Genotoxicity in Brazilian coal miners and its associated factors. Human and Experimental Toxicology, 37, 891–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0960327117745692.

Da Silva Júnior, F. M. R., Honscha, L. C., Brum, R. D. L., Ramires, P. F., Tavella, R. A., Fernandes, C. L. F., et al. (2020). Air quality in cities of the extreme south of Brazil. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Contamination, 15(1), 61–67. https://doi.org/10.5132/eec.2020.01.08.

De, O. M., & Branca, F. (2016). Childhood stunting: A global perspective. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12, 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12231.

dos Santos, M., Flores Soares, M. C., Martins Baisch, P. R., et al. (2018). Biomonitoring of trace elements in urine samples of children from a coal-mining region. Chemosphere, 197, 622–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.01.082.

Dupont-Soares M, Muccillo-Baisch AL, Roberto P, et al (2015) Intellectual capacity of children exposed to environmental pollution in the extreme South of Brazil. Journal of Health Science 3:183–195. https://doi.org/10.17265/2328-7136/2015.04.007

Emerson, E. (2012). Deprivation, ethnicity and the prevalence of intellectual and developmental disabilities. Epidemiol Community Heal, 66, 218–224. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2010.111773.

El, M. H., Schmidt, M. N., Franken, I. H. A., et al. (2013). Prenatal tobacco exposure and brain morphology: A prospective study in young children. Neuropsychopharmacology, 39, 792–800. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2013.273.

Emerson, E., Hatton, C., Robertson, J., & Baines, S. (2016). Exposure to second hand tobacco smoke at home and child smoking at age 11 among British children with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 3, 274–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12247.

Emerson, E., Robertson, J., Hatton, C., & Baines, S. (2018). Risk of exposure to air pollution among British children with and without intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12561.

Energy Information Administration (2020) Annual Coal Distribution Archive: Coal production, Brazil, Annual. In: Dep. Energy; Washingt. DC

EPA Agency Environmental Protection (2016) National Emissions Inventory

Fonseca, A. L. M., Albernaz, E. P., Kaufmann, C. C., et al. (2013). Impact of breastfeeding on the intelligence quotient of eight-year-old children. Jornal de Pediatria., 89, 346–353.

Goharpey, N., Crewther, D. P., & Crewther, S. G. (2013). Research in Developmental Disabilities Problem solving ability in children with intellectual disability as measured by the Raven ’ s Colored Progressive Matrices. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34, 4366–4374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2013.09.013.

Gorriz, A., Llacuna, S., & Nadal, M. R. J. (2002). Effects of Air Pollution on Hematological and Plasma Parameters in Apodemus sylvaticus and Mus musculus. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002449900091.

Ha, S., Hu, H., Roth, J., et al. (2015). Associations between residential proximity to power plants and adverse birth outcomes. American Journal of Epidemiology, 182, 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwv042.

Harding, J. F. (2015). Increases in Maternal Education and Low-Income Children’s Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 51, 583–599.

Huang, J., Zhu, T., Qu, Y., & Mu, D. (2016). Prenatal Perinatal and Neonatal Risk Factors for Intellectual Disability: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153655.

Inoue, Y., Umezaki, M., Jiang, H., et al. (2014). Urinary concentrations of toxic and essential trace elements among rural residents in Hainan Island China. International Journal Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111213047.

Kalia, V., Perera, F., & Tang, D. (2017). Environmental pollutants and neurodevelopment: Review of benefits from closure of a coal-burning power plant in Tongliang. Global Pediatric Health. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X17721609.

Kramer, M., & Kakuma, R. (2012). Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Systematic Review. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003517.pub2.www.cochranelibrary.com.

Kravchenko, J., & Lyerly, H. K. (2018). The Impact of coal-powered electrical plants and coal Ash impoundments on the health of residential communities. North Carolina Medical Journal, 79, 289–300.

Kwinta, P., Klimek, M., Grudzień, A., et al. (2012). Intellectual and motor development of extremely low birth weight (≤1000 g) children in the 7th year of life; a multicenter, cross-sectional study of children born in the Malopolska voivodship between 2002 and 2004. Medycyna Wieku Rozwojowego, 16, 222–231.

Lamm, S. H., Li, J., Robbins, S. A., et al. (2015). Are residents of mountain-top mining counties more likely to have infants with birth defects? The west virginia experience. Birth Defects Res Part A - Clin Mol Teratol, 103, 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdra.23322.

Landrigan, P. J., Fuller, R., Acosta, N. J. R., et al. (2018). The lancet commission on pollution and health. The Lancet, 391, 461–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32345-0.

Lima-Costa, M. F., Barreto, S. M., Giatti, L., & Uchoa, E. (2003). Socioeconomic circumstances and health among the brazilian elderly: A study using data from a National Household Survey. Cad Saude Publica. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2003000300007.

Liu, J., & Raine, A. (2017). Nutritional status and social behavior in preschool children: The mediating effects of neurocognitive functioning. Matern Child Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12321.Nutritional.

Macedo, C. S., & Andreucci, L. C. (2004). Alterações cognitivas em escolares de classe socio-econômica desfavorecida resultados de intervenção psicopedagógica. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, 62, 852–857.

Manso, J. M. M., & Alonso, M. B. (2008). Habilidades psicolingüísticas y dimensiones de inadaptación en niños en situación de acogimiento residencial. Revista Logopedia Foniatría y Audiologia, 28, 166–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0214-4603(08)70054-8.

Migliavacca, D., Teixeira, E. C., Pires, M., & Fachel, J. (2004). Study of chemical elements in atmospheric precipitation in South Brazil. Atmospheric Environment, 38, 1641–1656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2003.11.040.

Noble KG, Ph D, Houston SM, et al (2015) HHS Public Access. 18:773–778. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3983.Family

Paula A, Kobarg R, Vieira ML (2002) Crenças e práticas de mães sobre o desenvolvimento infantil nos contextos rural e Urbano. 401–408

Pinto, E. A. D. S., Garcia, E. M., De Almeida, K. A., et al. (2017). Genotoxicity in adult residents in mineral coal region-a cross-sectional study. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 24, 16806–16814. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-9312-y.

Redshaw M, Henderson J (2013) Fathers ’ engagement in pregnancy and childbirth: evidence from a national survey

Rodriguez-iruretagoiena, A., De, V. S. F., Gredilla, A., et al. (2015). Science of the total environment fate of hazardous elements in agricultural soils surrounding a coal power plant complex from Santa Catarina ( Brazil ). Science of the Total Environment, 508, 374–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.12.015.

Rubenstein, E., Durkin, M. S., Harrington, R. A., et al. (2019). Relationship between advanced maternal age and timing of first developmental evaluation in children with autism. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 39, 601–609. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000601.Relationship.

Santos, M., Penteado, J. O., Cristina, M., et al. (2019). Association between DNA damage, dietary patterns, nutritional status, and non-communicable diseases in coal miners. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26, 15600–15607.

Sears, C. G., & Zierold, K. M. (2017). Health of children living near coal ash. Global Pediatric Health. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X17720330.

Stafilov, T., Šajn, R., & Ahmeti, L. (2019). Environmental engineering geochemical characteristics of soil of the city of Skopje, Republic of Macedonia. J Environ Sci Heal Part A. https://doi.org/10.1080/10934529.2019.1620042.

Stevens GA, Finucane MM, Paciorek CJ (2016) Levels and Trends in Low Height-for-Age. Black RE, Laxminarayan R, Temmerman M, Walk N, eds Reprod Matern Newborn, Child Heal Dis Control Priorities, Third Ed (Volume 2) Washingt Int Bank Reconstr Dev/orld Bank;

Tang, D., Lee, J., Muirhead, L., et al. (2014). Molecular and neurodevelopmental benefits to children of closure of a coal burning power plant in China. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0091966.

Tang, D., Li, T., Liu, J. J., et al. (2008). Research | children’s health effects of prenatal exposure to coal-burning pollutants on children’s development in China. Environmental Health Perspectives, 116, 674–679. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.10471.

Tanić, M. N., Ćujić, M. R., Gajić, B. A., et al. (2018). Content of the potentially harmful elements in soil around the major coal-fired power plant in Serbia: relation to soil characteristics, evaluation of spatial distribution and source apportionment. Environmental Earth Sciences, 77, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-017-7214-4.

Tearne, J. E. (2015). Older maternal age and child behavioral and cognitive outcomes: A review of the literature. Fertility and Sterility, 103, 1381–1391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.04.027.

Trasande, L., & Liu, Y. (2011). Reducing the staggering costs of environmental disease in children, estimated At $76.6 Billion In 2008. Health Affairs, 30, 863–870. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1239.

Victora, C. G., Horta, B. L., De, M. C. L., et al. (2015). Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: A prospective birth cohort study from Brazil. Lancet Glob Heal, 3, 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70002-1.

World Energy Council (2016) World Energy Resources

World Health Organization (2006) WHO Air Quality Guidelines for particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide. Global Update 2005

Xu, X., Ha, S. U., & Basnet, R. (2016). A review of epidemiological research on adverse neurological effects of exposure to ambient air pollution. Front Publlic Heal. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00157.

Zablotsky, B., Black, L. I., Maenner, M. J., et al. (2019). Prevalence and trends of developmental disabilities among children in the United States: 2009–2017. Pediatrics, 144, 2009–2017. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0811.

Zhang, T., Sidorchuk, A., Sevilla-cermeño, L., et al. (2019). Association of cesarean delivery with risk of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders in the offspring a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10236.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the CAPES for providing doctoral scholarships and express their gratitude to the subjects who provided critical information for this study.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior-Brasil (CAPES)-Finance Code 001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MDS, MS and EMG were responsible for the elaboration of the research project, for the collection of epidemiological data and for scientific writing; MCFS and ALMB were responsible for designing the proposal and discussing the results. FMRSJ was the study advisor.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to all the ethical precepts recommended by Declaration of Helsinki, which regulates research involving human beings. Besides, the study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee in the Health Area of the Federal University of Rio Grande (CEPAS—FURG) under No. 36/2013.

Consent to participate

A written informed consent was obtained from all children and their guardians.

Consent to publication

The manuscript is reviewed and approved by all authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dupont-Soares, M., dos Santos, M., Garcia, E.M. et al. Maternal, neonatal and socio-economic factors associated with intellectual development among children from a coal mining region in Brazil. Environ Geochem Health 43, 3055–3066 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-021-00817-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-021-00817-1