Abstract

Prompted by the advent of new standards for increased text complexity in elementary classrooms in the USA, the current integrative review investigates the relationships between the level of text difficulty and elementary students’ reading fluency and reading comprehension. After application of content and methodological criteria, a total of 26 research studies were reviewed. Characteristics of the reviewed studies are reported including the different conceptualizations of text, reader, and task interactions. Regarding the relationships between text difficulty and reading fluency and comprehension, for students’ reading fluency, on average, increased text difficulty level was related to decreased reading fluency, with a small number of exceptions. For comprehension, on average, text difficulty level was negatively related to reading comprehension, although a few studies found no relationship. Text difficulty was widely conceptualized across studies and included characteristics particular to texts as well as relationships between readers and texts. Implications for theory, policy, curriculum, and instruction are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Does Text Difficulty Matter? A Research Synthesis of Text Difficulty and Elementary Students’ Reading Fluency and Comprehension

The advent of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS; National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGACBP) and Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) 2010) has ushered in a renewed focus on the types of texts used in instruction. Inspired by the claim that students graduating from high school are not prepared for the texts of both college and career, the standards call for an increase in text complexity in grades 2–12. Although the standards do not directly call for an increase in grades K-1, meeting the new standards in grade 2 likely necessitates increasing text complexity in grades K-1.

While this push might be warranted, its implementation precedes a clear understanding of effects on classroom achievement, particularly for students at the elementary level. On the one hand, the practice runs counter to a longstanding tradition in U.S. schools of matching texts to students’ instructional reading levels (e.g., Betts 1946; Fountas and Pinnell 1996). Further, some have demonstrated that when elementary children read more complex texts, their decoding accuracy, fluency rate, and comprehension decline (e.g., Amendum et al. 2016; Morris et al. 2013). But with achievement gaps among groups of students persisting (National Center for Education Statistics 2015), others have questioned the efficacy of the instructional level match (Shanahan 2011), suggesting instead that student achievement would accelerate with increased text complexity during reading instruction. Regardless, the current research base is unclear at best, and more research is necessary (Cunningham 2013; Mesmer et al. 2012).

Current conceptualizations of text complexity vary widely. On the one hand, some have used the term to refer to the readability of the text—reflected, for example, in the number of multisyllabic or rare words in a given sentence, the cohesion of the sentences, and other factors (see Benjamin 2011, for a review). According to this view, certain text characteristics make one text more complex than another. For example, a text about planets or the solar system might be deemed a fourth-grade level text based on a variety of text factors such as sentence length, word difficulty, or syntactic complexity. Others, however, conceptualize text complexity as dependent on what a reader brings to the text, coupled with characteristics of the text, arguing that what makes one text more complex than another depends on the interaction between reader and text characteristics (e.g., Fountas and Pinnell 1996; Morris et al. 2013). One reader’s extensive conceptual knowledge of planets, for example, would make the text about the solar system—despite its technical vocabulary—far less complex than it would be for a less knowledgeable reader. Further confounding what makes a text more or less complex than another is how the teacher supports the reading task to facilitate students’ successful reading (Valencia et al. 2014). In this scenario, a teacher’s choice of pedagogical techniques, for example, pre-teaching key vocabulary, choral reading, or using advance organizers, can provide conditions for students to learn from text that otherwise might be deemed too difficult.

Herein lies the central problem for meaningful and efficacious implementation of the Common Core State Standards: some students across the USA continue to struggle with reading achievement, yet at the same time, schools are “upping the ante” (Hiebert and Mesmer 2013, p. 44) by incorporating more difficult texts during classroom reading instruction. The evidence for this shift—specifically, for how reading these complex texts affects students’ reading achievement—remains tenuous, at best. The lack of research consensus on the topic of text complexity, coupled with its relevance, inspired this review. Our goal with the present review is to synthesize the evidence related to increased text difficulty and students’ reading achievement in the elementary grades.

How We Got here: Varying Perspectives of Texts

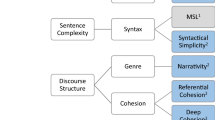

What makes one text more difficult than another has been an interest of researchers for almost a century, with readability formulas extending back to Thorndike (1921). Traditionally, text readability was deemed an issue of either its syntactic complexity (e.g., Fry Readability Graph; Fry 1968) or its semantic difficulty (e.g., Dale-Chall readability formula; Chall and Dale 1995). The conventional assumption was that texts with a higher frequency of longer words and sentences were more difficult for students to read, as evidenced by these traditional readability formulas (Benjamin 2011). More recently, however, measures of text readability have focused on added features, including aspects such as text cohesion and narrativity (e.g., Coh-Metrix; Graesser et al. 2011).

Still, others move beyond text-centric conceptualizations, arguing instead that there should be a match between the text and the skills of the learner (e.g., Betts 1946; Gray 1915). Rooted in the Vygotskian notion of zone of proximal development (ZPD; 1978), Betts argued that there was an ideal match possible between the reader and the text, based on the reader’s ability to accurately decode the words and comprehend the text. This model inspired several assessments and instructional programs still widely used today, such as informal reading inventories (e.g., Leslie and Caldwell 2011; Woods and Moe 2014), the Lexile Framework (MetaMetrics 2015), and the guided reading instructional format (Fountas and Pinnell 1996, 1999). Furthermore, from the 1940s until controlled vocabulary stopped the design of core reading programs, both assessments and instructional texts were constructed using the same difficulty algorithms, to closely align students’ assessment, placement, and instruction (Hiebert and Raphael 1996), a practice no longer common.

There has been criticism of various attempts to match readers to texts, largely due to the lack of research evidence (Allington 1984; Cunningham 2013; Shanahan 2011). Powell (1970), for example, argued early on in the era of the algorithmic model of texts for instruction and assessment that the usefulness of the construct might differ as a function of the capabilities of the reader. Others have argued that the match is imperfect because it fails to take into account the role that interest or other aspects of motivation might play (Halladay 2012; Hunt 1970), specifically, that readers can handle more difficult texts when they are motivated to read them.

Valencia et al. (2014) have recently advanced another perspective, arguing for a conceptualization that features the role of the task—which includes instructional conditions, curricular demands, or even assessment. They argue that tasks, which are malleable, can be used by the teacher to make a text more or less difficult for the reader (Goldman and Lee 2014).

Given these different foci, in undertaking this review, we acknowledge some problems with operationalization of terms from the outset. Thus, we find it helpful to distinguish between different terms presented in the literature. We refer to Mesmer et al.’s (2012) distinction that text complexity refers to properties of a text, regardless of reader or task, while text difficulty refers to how easy or hard a text is for readers. A text’s complexity is established relative to other texts. The orientation for text difficulty is the reader (and possibly, task). Presumably, any text can be difficult for at least some readers, depending on their capacity. For the present review, we join others in underscoring the centrality of comprehension (Valencia et al. 2014); text difficulty, therefore, becomes the central focus (see Fig. 1).

Model of text difficulty, based on the reading comprehension heuristic provided by RAND (NGACBP & CCSSO, 2010, p. 8) and conceptualization of text complexity and text difficulty from Mesmer et al. (2012)

Theoretical Framework

We view the conceptualization of text difficulty within the theoretical framework of reading comprehension presented by the RAND Reading Study Group (2002), which closely relates to the perspective on text complexity presented in the Common Core State Standards (NGACBP and CCSSO 2010). The RAND model highlights how interactions among reader, text, and activity, within a specific sociocultural context, are central to the act of reading comprehension. Presumably, a reader’s proficiency in negotiating particular texts is affected by characteristics of the reader, specific aspects of the text itself, and the task (or activity) that the student completes. When a text (no matter how complex it is judged to be relative to other texts) has features with which the reader is facile, a text would be viewed as easier. When a text (again, regardless of its designation of complexity with respect to other texts) has features with which the reader is not completely facile, reading the text will present increased challenge, unless accompanied by a supportive task. The challenge, it would be assumed, is a matter of degree. Further, some features may figure more heavily than others into the challenge of reading difficult texts for readers with particular proficiencies.

In undertaking this review, we were also guided by the notion of challenge—which is present in many theories of learning. Though some have argued that challenge has been regarded as inappropriate in classrooms (Clifford 1984), others point to the benefits of challenge, noting that working through challenging tasks––even when the outcomes are not successful––is necessary for students to increase their capacity in a domain, a notion known as productive failure (e.g., Kapur 2008). Still others highlight that a learner’s disposition towards challenge depends on their goals or mindset (Atkinson 1957; Dweck 2006; Eccles et al. 1998; Maehr 1984). For example, if the learner has a growth mindset or a goal of mastery, he or she will be more willing to persevere in the face of challenging tasks.

Present Study

Providing students with difficult texts has become a central issue as a result of perspectives within the Common Core State Standards (CCSS). But this shift has come with little empirical evidence. In the present review, we examine research studies, conducted over the last 45 years, that considered the relationships of text difficulty and elementary students’ reading achievement. Our interests included relationships between text difficulty and aspects of reading achievement, as well as characteristics of the studies themselves, such as the theoretical framing of each as well as potentially different ways that researchers conceptualized text/reader/task interactions. Specifically, we ask:

-

1.

What are the characteristics of rigorous research studies that investigate relationships between text difficulty and students’ reading fluency and/or comprehension?

-

2.

How are text/reader/task interactions conceptualized across the included studies?

-

3.

What is the relationship between text difficulty and students’ reading fluency?

-

4.

What is the relationship between text difficulty and students’ reading comprehension?

Method

To investigate what relationships exist between text difficulty and students’ reading achievement, we conducted an integrative review of the research literature (e.g., Fitzgerald 1995; Torraco 2005). The goals of integrative reviews are to synthesize ideas and to clarify concepts that are not well-defined. Our goal was to integrate empirical findings related to text difficulty and reading achievement. Central to our purpose, we focused on studies, conducted at the elementary level (kindergarten through fifth grade; approximately ages 5–10 in U.S. schools), that included the reading of at least two levels of text (more and less difficult) and that reported fluency and/or comprehension outcomes.

Data Collection

The Initial Review Process

Since our goal was to establish what previous research has demonstrated, we limited our review to empirical studies only (see Table 1 for an overview of the process presented below). We used several different keywords in our search. These included “text complexity,” “text difficulty,” “text challenge, “text characteristics,” “text level,” “readability,” and “reading level.” Initial searches yielded a total of 4872 unique articles. Within this large database, we searched for, and excluded, duplicate articles and articles clearly lacking connection to our study, which led to the exclusion of 1236 articles. Of the remaining 3636 articles, we next limited our sampling frame to the last 45 years. Any studies published prior to 1970 were thus excluded. This led to the exclusion of 2874 additional articles.

For the remaining 762 articles, we read the titles to further ascertain their appropriateness for this review. For many articles, it was clear—from just reading the title—that the article represented a study lacking relevance to our review. For example, articles related to cultural representation in children’s literature (e.g., Your Place or Mine? Reading Art, Place, and Culture in Multicultural Picture Books), or text difficulty in science textbooks for adolescents (e.g., The Reading Difficulty of Textbooks in Junior High School Science), were excluded. If we were unsure about the relevance of the study, based on the title alone, we included the article for the next round of review.

Study Review

After applying all of these exclusionary criteria and conducting the initial review based on titles, 329 articles remained in our database. We reviewed the remaining studies in two sequential phases. In the first phase, we reviewed abstracts only. Again, our goal was to ensure that all included articles presented a clear representation of text difficulty and had a reading achievement outcome related to reading fluency (including accuracy, rate, and/or prosody) or reading comprehension. If it was clear in reading the abstract that a study was not related to our review, it was excluded; however, if relevance was unclear from the abstract only, we included the article for review in the subsequent phase. After review of all abstracts, 79 articles remained for further review.

In the second phase, we applied methodological standards for inclusion adopted from previous reviews (i.e., Alvermann et al. 2006; Amendum and Fitzgerald 2011). We carefully read relevant parts of the article, focusing mainly in the methods and results sections. Beyond including a text difficulty construct and a reading achievement outcome, we adopted additional inclusionary criteria for studies. These inclusionary criteria for quantitative studies included (a) inclusion of a control or comparison group for experimental or quasi-experimental designs or inclusion of normative data for comparison; (b) at least four subjects present in comparison groups for experimental or quasi-experimental designs; (c) pretests for outcomes of interest for quasi-experiments (with the exception of regression discontinuity designs, if applicable); and (d) a minimum sample size of 20 participants for correlational studies. For qualitative study designs, criteria for inclusion were dependent on the particular research paradigm used and generally included (a) sufficient methodological detail (e.g., an audit trail); (b) reflection on findings and/or perspectives by the researcher (s); (c) documentation of consideration of alternative explanations; (d) presentation of primary data, such as quotations or stories; (e) conclusions that reflected confirmation of learning from study results and not validation of author (s)’ prior beliefs; and (f) description or discussion of the study findings related to wider discourse. After careful analysis of 79 articles, we were left with a set of 23 articles for the review.

Additional Search

We next added two types of searches to find additional studies. The first type, often called “footnote chasing” (White 1994, p. 218) involved looking through the references of our included articles. In doing so, we were looking for articles published before those included in ours to ascertain whether any might be relevant or appropriate for inclusion in our review. Such a review invites consideration of relevant studies that have leaned on each other and can go back “generations” (Shanahan 2000, p. 218).

We added to this well-established approach by also finding articles that were published after ours, but that had cited those included in our set. We did this by entering each included article in Google Scholar and clicking on “cited by” and then “search within citing articles.” In doing so, we were hoping to find related research that cited our included studies—this process served as a way to include future generations of relevant work.

Collectively, these two search processes led to the consideration of an additional 109 articles. After applying the same inclusionary criteria we describe above, 21 articles were reviewed for inclusion in the final database, of which three met all criteria for inclusion.

Data Analysis

Our final set of articles included 26 studies (see Table 2). With this final set, two of the authors independently reread each article. For each article, each of the two authors noted the following specific information in a table: authors, year of publication, design, theoretical frame, participants, conceptualization of text challenge, measure of text difficulty, outcome measures, support during measurement of reading outcomes, length of reading outcome measure/material, and major findings. Each article was discussed and information from each of the two author’s notes was aggregated onto the final version of the table. We describe the coding of each variable below.

Design

Studies fell into four types of designs: single-subject, correlational, quasi-experimental, and experimental. Single-subject designs were characterized as studies where students’ outcomes were tracked at the individual, rather than the group level, typically with very small samples. Correlational studies were characterized as studies that investigated relationships among two or more variables. Quasi-experimental studies attempted to establish cause/effect relationships, but without random assignment to groups. Experimental studies were like quasi-experimental, except researchers used random assignment to groups.

Theoretical Frame

Given the differences in how the topic of text difficulty has been conceptualized over the years, it was important for us to examine which theories were used to guide authors’ investigations. We considered not only whether a theory was stated (and what that theory was), but also how explicit authors were in presenting how theory guided their study. For example, if the author had a subheading Theory, accompanied by a paragraph describing how that theory informed their study, we considered that to be an explicit and specific presentation. On the other hand, if a theory was mentioned in passing, we coded these as broad. Finally, some studies failed to present theories at all and were coded as “not present.”

Participants

Our studies all included participants who were elementary-aged. Beyond this, we felt it was vital to establish if the sample was drawn from a specialized population (e.g., students identified as learning disabled). We coded the studies for the number of participants, participants’ grade level (s), and noted any special characteristics of the sample (e.g., all low-performing readers).

Conceptualization of Text Difficulty

It became apparent, early on in our search process, that authors conceptualize text difficulty differently. We noted that all the studies conceptualized text difficulty in one of two ways—with respect to an individual reader/text match (often conceptualized as independent, instructional, or frustration levels; see Morris et al. 2013) or with respect to a group or grade level/text match (readability of text relative to grade level of group; see Benjamin and Schwanenflugel 2010). Thus, we ended up coding for conceptualization in two ways.

Measure of Text Complexity

Although all included studies necessarily conceptualized more/less difficult text, we coded for the specific metrics or indices presented to note text complexity. There is a long history of measuring text complexity with readability formulas (Benjamin 2011), but more recent computerized measures account for more sophisticated text characteristics such as cohesion and nominalization (McNamara et al. 2012). In considering how some texts were more complex than others, researchers most often pointed to vocabulary used (e.g., number of difficult words, number of unique words) and sentence length.

Reading Outcome Measures

The variable of interest for the present investigation is reading—specifically, how text difficulty level relates to students’ reading. As such, studies included had to have an outcome variable related to reading connected text, rather than word lists. We were specifically interested in outcome measures related to fluency or comprehension. Fluency has typically been conceptualized as a three-pronged construct, and we included any studies that measured how text difficulty related to students’ reading accuracy, their reading rate, or their reading prosody (Kuhn and Stahl 2003) using connected texts/reading passages. Thus, some studies that did look at word reading, but that measured it using word lists (e.g., Vadasy and Sanders 2009), were not considered. In addition, since the main goal of reading is to derive meaning from text (e.g., Kintsch 1998), we also were interested in how students’ comprehension was related to text difficulty. Comprehension is typically measured using questions that follow a reading of text or using a cloze task procedure.

Support During Assessment of Reading Outcomes

Additionally, given the role task might play, we considered the context in which students’ reading fluency and/or comprehension outcomes were measured. We felt there could be differences if measurement took place during an instructional context versus an assessment context (i.e., curriculum-based measurement or standardized testing). As such, we coded each study to reflect whether any support was provided to students within the measurement context, and if so the extent of the support.

Length of Assessment

Because the measures of students’ reading fluency and/or comprehension varied across studies, we felt it was important to capture differences among the studies with respect to the measures themselves. In coding the length of assessment, we attempted to consider the length of time needed for students to complete the assessment, as longer assessments could be more taxing for students than quick assessment tasks. We considered indicators of length and from the studies reviewed we were able to consider whether the assessment was timed or whether the length of the text(s) used for assessment was described. For example, students’ fluency may have been measured as a one-minute sample of reading or measured within the context of reading a longer text. Comprehension may have been measured after reading a single passage or after reading a number of passages with corresponding questions, which is often the case in standardized tests of comprehension. Thus, we provide brief descriptive information about the length of time in which the outcome data were captured or the length of the material used if the time was not clear from the study.

Major Findings

Each study was coded for the major findings directly related to fluency and comprehension outcomes. Although studies often investigated broader questions than how text difficulty may have mattered, we only focused on the parts of the studies that were related to this review.

Results

What Are the Characteristics of the Studies?

The final set of 26 studies (Table 2) was published between 1970 and 2015 in 17 different journals, representing reading research, educational psychology, special education, and school psychology. Below we provide brief descriptive data about the studies and follow with results related to relationships between text difficulty and reading achievement. Table 3 provides a broad overview of all results and may be useful to orient readers.

Types of Outcomes

A criterion for inclusion in our review was that the studies included a fluency or comprehension outcome. Half (13) of our studies used only a fluency outcome to assess relationships with text difficulty. Most of these studies relied on common measures of reading fluency, which involved considerations of reading accuracy, rate, or a combination of the two (e.g., words read correctly per minute). Three studies (Benjamin and Schwanenflugel 2010; Hoffman et al. 2001; Young and Bowers 1995) also included measures of prosody.

Four of our studies (15.38%) focused only on reading comprehension outcomes. For two of the studies (Spanjers et al. 2008; Treptow et al. 2007), outcomes were typical comprehension measures used in school settings; specifically, students read a short passage and answered corresponding comprehension questions. The percentage of questions answered correctly represented students’ comprehension. One study (Topping et al. 2008) used a computer adaptive standardized reading comprehension measure. The remaining nine articles (34.62%) included measures of both fluency and comprehension.

Participants

The number of participants in the studies ranged from 3 to 45,670, with a median number of 84. Participants were in first through sixth grades, with the majority of studies focused on students in second through fourth grades. The characteristics of students within the studies varied considerably. Some studies were conducted with relatively homogeneous samples, focusing on struggling readers (e.g., Vadasy and Sanders 2009) or students living in poverty (e.g., Hoffman et al. 2001). Others were more varied with respect to students’ reading abilities or racial/ethnic composition (see Table 2 for additional detail).

Designs/Types of Studies

For inclusion in our review, we only included studies that met rigorous methodological criteria. The majority of studies (18; 69.23%) in our final corpus employed correlational designs. An additional number were quasi-experimental (4; 15.38%) or experimental (n = 3; 11.54%). One study employed a single-subject design (3.85%).

Theoretical Frameworks

Over half of the studies (15; 57.69%) were not situated in any explicit theoretical framework or perspective (e.g., Ardoin et al. 2005; Morgan et al. 2000). Other studies stated theory but varied in the degree to which these theories were articulated. Seven studies (26.92%) only mentioned a theory (for example, Benjamin and Schwanenflugel 2010), whereas four studies (15.38%) explicitly presented how theoretical frameworks undergirded their study. For example, Vadasy and Sanders (2009) explicitly referenced how both the Simple View (Gough and Tunmer 1986) and Verbal Efficiency Theory (Perfetti 1985) informed their work.

The theory most often mentioned was LaBerge and Samuels’ Automatic Information Processing Theory (1974)—mentioned in seven different articles. Five articles also mentioned Perfetti’s Verbal Efficiency Theory (1985) and three articles mentioned the Simple View of Reading (Gough and Tunmer 1986). One each mentioned Situated Cognition (Brown et al. 1989), top-down (e.g., Smith 1973) vs. bottom-up models (e.g., Biemiller 1970), and a theoretical model of text complexity (Mesmer et al. 2012).

How Were Text/Reader/Task Interactions Conceptualized?

Conceptualization of Text/Reader

Even though theories were not explicitly presented as framing most of the studies, how researchers conceptualized the notion of text difficulty within their studies provides some insight into the lenses applied to this type of research. Specifically, as we coded the articles in the final corpus, we considered whether text difficulty was conceptualized as a function of the interaction between the individual reader and text or whether text difficulty was conceptualized more in terms of its measurable complexity relative to grade-level expectations of the readers. In the former situation, a text is deemed appropriate for a particular student to read because he has demonstrated that he can read similar texts with success; in the latter, a text is deemed appropriate for a student if he is in the grade level that matches the readability of the text.

Individual Reader/Text Match

Eight studies (30.77%) conceptualized text difficulty by considering an interaction between individual readers and the text (Amendum et al. 2016; Cramer and Rosenfield 2008; Ehri et al. 2007; Morgan et al. 2000; O’Connor et al. 2002, 2010; Sindelar et al. 1990; Treptow et al. 2007). These studies typically presented texts as more difficult relative to a student’s reading level; conceptualizations, therefore, were contingent to some degree on a student’s performance on a particular text. For example, O’Connor et al. (2010) judged texts to be more difficult for students if they were only 80%–90% accurate when decoding them, as compared to texts they could decode with higher accuracy.

Though these conceptualizations accounted for student performance, studies often still presented measures of text complexity to further describe texts (e.g., Morgan et al. 2000; O’Connor et al. 2002, 2010). However, not all studies presented specific details about the text. Two studies provided no specific calculations of text complexity and instead relied on the established and publisher-reported text levels (Cramer and Rosenfield 2008; Ehri et al. 2007). Two relied only on student performance (i.e., reading rate and reading accuracy) in determining text difficulty (Sindelar et al. 1990; Treptow et al. 2007). In both cases, less difficult texts were conceptualized as those read with increased performance (higher rate or higher accuracy).

Group or Grade/Text Match

Eighteen studies (69.23%) conceptualized text difficulty by examining characteristics inherent to the text and its appropriateness for a particular grade or group. Of these 18 studies, 12 used traditional readability formulas that tend to consider word length, sentence length, and characteristics of vocabulary as factors that make a text harder (Ardoin et al. 2005; Benjamin and Schwanenflugel 2010; Chinn et al. 1993; Compton et al. 2004; Faulkner and Levy 1994; Hintze et al. 1998; Powell-Smith and Bradley-Klug 2001; Ryder and Hughes 1985; Spanjers et al. 2008; Topping et al. 2008; Vadasy and Sanders 2009; Young and Bowers 1995). Within those studies, the most common readability formula used was the Flesch-Kincaid (five studies). The remaining studies employed less traditional calculations. These included Critical Word Factor (Cheatham et al. 2014; Hiebert and Fisher 2007; Hoffman et al. 2001), percentage of preprimer words and/or basal levels (Biemiller 1979; Cecconi et al. 1977), STAS-1 (Hoffman et al. 2001), and passage levels from a standardized test (Blaxall and Willows 1984).

It was not uncommon for studies to present multiple indices of text complexity beyond readability formulas. For example, in addition to calculating the Flesch-Kincaid and Spache readability formulas for the 15 texts used in their study, Compton et al. (2004) also considered the decodability, the percentage of high-frequency words, the percentage of multisyllabic words, and the average sentence length of each of the passages.

The Role of Task

Prior to synthesizing results related to text difficulty and reading achievement, consideration of tasks is warranted. We coded two key issues related to measurement tasks—support during measurement and length of outcome measure or reading material. Detailed descriptions of the two issues follow below.

Due to the varied nature of the studies reviewed, there were differences in the support provided to students during the measurement of reading outcomes. The majority of studies (17; 65.38%) provided no support at all to students—a true assessment task context. Four studies (15.38%) provided minimal support to students prior to reading (Benjamin and Schwanenflugel 2010; Cheatham et al. 2014; Hiebert and Fisher 2007; Ryder and Hughes 1985). The types of minimal support provided prior to reading included that the teacher read the directions or title, activated prior knowledge or told students the subject of the passage, or provided a bookmark with decoding reminders. Three studies (11.54%) provided minimal support during reading (Biemiller 1979; Blaxall and Willows 1984; Powell-Smith and Bradley-Klug 2001). The type of minimal support provided during reading included teachers providing unknown words after a particular number of seconds (range = 3 to 10). In one study (3.85%) (Chinn et al. 1993) students received more moderate support during reading in the form of teacher feedback while reading. One final article (Hoffman et al. 2001) had a range of support across different conditions, ranging from reading the title to students to providing modeled reading prior to students’ reading.

There were also differences in the length of the outcome measures or reading materials used, and some studies employed multiple measures. Five studies (19.23%) included measures of reading using a one-minute sample of time (Ardoin et al. 2005; Cheatham et al. 2014; Compton et al. 2004; Hintze et al. 1998; Powell-Smith and Bradley-Klug 2001). Other studies used untimed measures; six (23.08%) included passages and open-ended questions from informal reading inventories (Amendum et al. 2016; Cramer and Rosenfield 2008; Morgan et al. 2000; O’Connor et al. 2002, 2010; Young and Bowers 1995), nine (34.62%) included passages constructed from basal readers or other materials with either open-ended or multiple choice questions (Biemiller 1979; Blaxall and Willows 1984; Cecconi et al. 1977; Faulkner and Levy 1994; Ryder and Hughes 1985; Sindelar et al. 1990; Spanjers et al. 2008; Treptow et al. 2007; Vadasy and Sanders 2009), and four (15.38%) included intact stories or texts with either open-ended or multiple choice questions (Chinn et al. 1993; Hiebert and Fisher 2007; Hoffman et al. 2001; Topping et al. 2008). Five studies employed standardized tests of reading comprehension, using the protocols dictated by the test (Benjamin and Schwanenflugel 2010; Ehri et al. 2007; O’Connor et al. 2002, 2010; Vadasy and Sanders 2009).

What Is the Relationship Between Text Difficulty and Students’ Reading Fluency?

Twenty of the studies (76.92%) focused on some aspect of reading fluency as an outcome (see Table 2). Many of these studies looked at more than one aspect of fluency, so we separate findings below into those related to accuracy, rate, and prosody.

Accuracy

Researchers in 12 studies considered the effect text difficulty might have on students’ reading accuracy (Biemiller 1979; Blaxall and Willows 1984; Cecconi et al. 1977; Chinn et al. 1993; Compton et al. 2004; Cramer and Rosenfield 2008; Faulkner and Levy 1994; Hiebert and Fisher 2007; Hoffman et al. 2001; Morgan et al. 2000; Sindelar et al. 1990; Young and Bowers 1995). By and large, accuracy was approximated as the percentage of words read correctly, though four studies instead considered error rates (Biemiller 1979; Blaxall and Willows 1984; Chinn et al. 1993; Sindelar et al. 1990), and one considered frequency of disfluencies (Cecconi et al. 1977).

Overall, with only one exception (i.e., Morgan et al. 2000), there was a negative relationship between text difficulty level and students’ reading accuracy. Specifically, students were more likely to make errors when texts increased in difficulty and this problem was particularly acute for poorer readers (Young and Bowers 1995) and for beginning readers (Hiebert and Fisher 2007; Hoffman et al. 2001). Interestingly, 10 of the 11 studies that demonstrated a negative relationship employed untimed measures of accuracy, rather than one-minute time samples.

How text difficulty was conceptualized or measured also mattered for results. Compton et al. (2004) found that there was no association between accuracy and estimates of readability or percentage of multisyllabic words or average sentence length but that the number of high-frequency words did relate to accuracy. Students were more likely to be accurate in texts with a larger percentage of high-frequency words. Chinn et al. (1993) found that certain measures of text difficulty—specifically the density of hard words on a page—was more related to high-meaning change errors than other measures of story difficulty. On the other hand, Hoffman et al. (2001) found that across all types of measures of difficulty, students’ accuracy decreased.

Study condition (i.e., the role of task) also played a role in the relationship between text difficulty and accuracy. When students encountered the same words across texts––as a deliberate task––they were more likely to be accurate. For example, in one study (Sindelar et al. 1990), the researchers had participants read pairs of easy and difficult texts in one of four conditions. Each condition involved different types of text manipulation. For the first condition, students read the same text twice. For other conditions, there was word overlap (with 75.60% of same words); paraphrase (with 28.28% of same words) or unrelated (with 12.85% of same words). Although, students overall were more accurate with easier texts than with more difficult texts, analyses do suggest that the type of text also mattered. For more difficult texts, students were more accurate when they read pairs of difficult texts that involved word overlap or repetition than they were when fewer shared words were used. This practice—of students reading texts multiple times—also led to increased accuracy in other studies (Sindelar et al. 1990).

Similarly, other studies highlight that the negative relationship between text difficulty and word-reading accuracy even within a context of supportive teacher/student interactions (Chinn et al. 1993; Hoffman et al. 2001). For example, Chinn et al. (1993) investigated patterns of oral reading errors, student responses, and teacher feedback for 116 students during four reading lessons, each with progressively more challenging passages. On average, even with varying levels of feedback from teachers, students demonstrated lower accuracy as passage difficulty increased.

Rate

Fifteen studies examined rate as an outcome. Rate was measured in two different ways—either words per minute (wpm; N = 5) or words correct per minute (wcpm; N = 10). Notably, although the latter measure accounts for accuracy as well as rate, we separated rate and accuracy because some of the studies examined accuracy separately and because the distinct constructs were of interest to us. Additionally, the use of wcpm instead of wpm as a measure of rate is typical (e.g., Kuhn and Rasinski 2011), and Morris et al. (2013) used a conversion factor of 0.95 in converting wcpm to wpm.

Collectively, 73.33% (11) of the studies demonstrated, on average, that as text difficulty levels increased, students’ reading rates decreased (Ardoin et al. 2005; Compton et al. 2004; Cramer and Rosenfield 2008; Faulkner and Levy 1994; Hiebert and Fisher 2007; Hintze et al. 1998; Hoffman et al. 2001; O’Connor et al. 2002; Sindelar et al. 1990; Vadasy and Sanders 2009; Young and Bowers 1995). For example, students reading texts with higher task demands for word recognition read significantly fewer words correct per minute (Hiebert and Fisher 2007). Notably, this finding held across different types of outcome measures (i.e., single minute vs. untimed); however, most measurement of fluency outcomes was characterized by no teacher support within the measurement task. In another study, second-grade students had improved reading rates when reading easier texts, defined as those with greater percentages of high-frequency words and/or a greater percentage of decodable words (Compton et al. 2004). Four studies found no relationship between the level of text difficulty and students’ reading rates (Cheatham et al. 2014; Morgan et al. 2000; O’Connor et al. 2010; Powell-Smith and Bradley-Klug 2001).

In some studies, the role of task affected students’ reading rates. For example, two studies had students engage in repeated readings (Faulkner and Levy 1994; Sindelar et al. 1990), and results from both demonstrated the positive effect of repeated reading on students’ reading rate; however, only one demonstrated the repeated reading effect on rate for both less and more difficult texts (Faulkner and Levy 1994). Results from the other study demonstrated the overall positive effect of repeated reading but did not include text difficulty in that particular analysis (Sindelar et al. 1990). Students also demonstrated improved reading rates when reading aloud to an adult who provided support and motivation, regardless of text difficulty (O’Connor et al. 2010) or when reading a text previously read aloud by the teacher (Hoffman et al. 2001).

Notably, developmental level/skill level of the readers in some studies played a significant role. In general, for students with less advanced reading skill and/or in earlier grade levels/ages, the negative relationship between text difficulty and reading rate was strong. However, for students with more decoding skill (Cheatham et al. 2014), more fluent reading (O’Connor et al. 2002), or in later elementary grades (4th/5th; Hintze et al., 1998), the negative effect of text difficulty either decreased (Young and Bowers, 1995) or disappeared (Cheatham et al. 2014; Hintze et al. 1998; O’Connor et al. 2002). To be clear, there was not a positive relationship with difficulty, but rather, there was no effect in these situations.

Prosody

Three studies looked at prosody as a fluency outcome (Benjamin and Schwanenflugel 2010; Hoffman et al. 2001; Young and Bowers 1995). Two studies suggested that students’ reading prosody with more difficult texts depended in part on their reading skills (e.g., Benjamin and Schwanenflugel 2010; Young and Bowers 1995). That is, higher skilled readers’ prosody was not necessarily negatively affected by an increase in text difficulty. For example, students who had scored high on two measures of word reading were actually more likely to pause in between sentences and according to the sentence’s grammar. These behaviors were consistent with skilled adult readers and for this sample, higher skilled students’ prosody accounted for more variance in comprehension for more difficult texts than for less difficult ones (Benjamin and Schwanenflugel 2010). On the other hand, in both studies, lower skilled readers’ prosody declined with more difficult texts. For example, less skilled readers—which in one study, were defined as readers on grade-level—paused more often and pauses were often ungrammatical (Benjamin and Schwanenflugel 2010).

The findings for lower-skilled readers are more consistent with findings from a study conducted with beginning readers (i.e., Hoffman et al. 2001). In that study, conducted with first grade students, students’ prosody, which was evaluated using ratings of students’ reading, on average, declined when students read more difficult texts.

What Is the Relationship Between Text Difficulty and Students’ Reading Comprehension?

Thirteen (50%) of the studies focused on reading comprehension as an outcome. Although results were mixed, no study indicated that increased text difficulty was related to an increase in students’ comprehension. Seven studies (53.85%), however, demonstrated a negative relationship between text difficulty and reading comprehension (Amendum et al. 2016; Cramer and Rosenfield 2008; Ehri et al. 2007; Hiebert and Fisher 2007; Spanjers et al. 2008; Treptow et al. 2007; Vadasy and Sanders 2009). Specifically, as text difficulty increased, on average, students’ reading comprehension decreased. For example, Hiebert and Fisher (2007) demonstrated that as students read texts with increasing Critical Word Factor scores (more difficult text), on average, their comprehension decreased. Amendum et al. (2016) showed that students who read texts well above their grade level, even with at least 90% accuracy, had significantly lower comprehension than students reading texts near grade level.

One study (7.69%) demonstrated an optimum degree of text difficulty for comprehension (Topping et al. 2008). Topping et al. (2008) showed that a moderate amount of text difficulty was most beneficial for students’ comprehension. Students, on average, had lower comprehension scores with texts that were either too easy or too difficult.

Finally, five studies (38.46%) found no significant relationship between text difficulty and comprehension (Morgan et al. 2000; O’Connor et al. 2002, 2010; Ryder and Hughes 1985; Sindelar et al. 1990). That is, students’ comprehension performance did not differ significantly when text difficulty was increased or decreased. For example, O’Connor et al. (2002) employed a quasi-experimental design to, in part, investigate whether reading level-matched text or grade level-matched text was more beneficial for students’ reading comprehension compared with a control group. Their results showed that neither level of text difficulty was more beneficial for comprehension; however, students in both intervention conditions, on average, outperformed students in the control condition.

Results varied for a few different reasons. The type of measure used to assess comprehension mattered. Even within one study (Vadasy and Sanders 2009), significant differences were found for one comprehension measure but not another. In addition, the developmental level of students may have been related to the outcome. For younger (e.g., Ehri et al. 2007) or lower skilled/struggling readers (e.g., Vadasy and Sanders 2009), there was often a clear negative relationship between text difficulty and comprehension. On the other hand, for older students with more advanced reading skills (e.g., O’Connor et al. 2002; Sindelar et al. 1990), there may not have been a clear relationship between text difficulty and comprehension. Finally, the conditions of the study may also have been related to the outcomes. Interestingly, of the five studies that demonstrated no relationship between text difficulty and comprehension, three were experimental or quasi-experimental intervention studies (Morgan et al. 2000; O’Connor et al. 2002, 2010) where students received small group or one-on-one interventions.

Discussion

In undertaking this integrative research review, we set out to investigate the evidence base related to the relationship between text difficulty and reading achievement, specifically fluency and comprehension, for elementary students. Before engaging in discussion related to the main review findings, we turn to the question posed in the title, does text complexity matter in the elementary grades? Based on the findings from the review, text complexity matters in important ways. In the simplest form, more difficult texts are negatively related to fluency and either negatively related, or unrelated to, comprehension. In a more sophisticated form, the difficulty of a text is best captured by the interaction of the reader’s characteristics and the complexity of the text and is likely further moderated by the context of the task or activity in which the reader/text interaction occurs (Valencia et al. 2014). Clearly, our answer to the question of whether text complexity matters in the elementary grades is tentative at best, as more research is needed to address this important and relevant question.

Below, we turn to the findings from the review and first discuss the characteristics of the studies, findings related to fluency, and findings related to comprehension. We follow with implications for theory, for research, and for policy, curriculum, and instruction, before concluding with limitations and recommendations for future research.

Characteristics of the Studies

Lack of Theoretical Frameworks

The fact that most studies included in this review were absent of any theoretical framework highlights the need for researchers to ground investigations in theory. Existing theories might provide useful starting points. For example, current theories often used relative to text difficulty are derived from the widely cited and accepted RAND model of reading (2002) and the CCSS, Appendix A (NGACBP and CCSSO 2010). The RAND model includes four variables—the reader, the text, the activity, all embedded in the surrounding sociocultural context. The majority of the studies reviewed here address the reader and text and highlight the importance of how these variables might interact to make a text more or less difficult for readers. But the research literature is less clear about how activity and the sociocultural context affect reading comprehension for texts with different levels of difficulty, and it is vital that researchers address these gaps in the literature.

In addition, future theories of text difficulty and/or complexity might consider potential developmental differences. Specifically, it is important to consider how reading development might affect theory related to text difficulty. One can hypothesize that the relationships among the text, reader, and activity might change over time as students become more proficient readers. Stage theories hypothesize this very idea—that over time, students master beginning skills and move to more complex skills as their reading proficiency develops (e.g., Chall 1996; Ehri 1991). Our findings demonstrate these potentially changing relationships; for example, the negative relationships found between reading rate and text difficulty level either decreased (Young and Bowers 1995) or disappeared (Cheatham et al. 2014; Hintze et al. 1998; O’Connor et al. 2002).

Conceptualizations of Text/Reader/Task

The majority of studies (18 studies; 70%) conceptualized text difficulty as a group or grade/text match, whereas seven studies (27%) considered text difficulty in terms of an individual reader/text match, and one study (O’Connor et al. 2002) conceptualized text difficulty in both ways. This divide disables the field from drawing clear implications. Consider a classroom of second grade students: if researchers conceptualize text difficulty only in terms of a group or grade/reader text match, according to the CCSS (Appendix A, p. 8), Henry and Mudge: The First Book (460 L)Footnote 1 (Rylant 1996), would be considered a beginning of second-grade level text. Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People’s Ears (770L) (Aardema 1975) would be considered a beginning of fourth-grade level text. In this case, the assumption is that the latter text would always present more of a challenge to second-grade readers, and likewise, because of the similar Lexile levels, Danny, the Champion of the World (770L) (Dahl 1975) would be approximately the same level of difficulty as Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People’s Ears for second grade students. Studies that conceptualize text/reader/task in this way typically consider readers’ grade levels or other grouping variable and orient the text accordingly. On the other hand, researchers conceptualizing text difficulty in terms of an individual reader/text match would orient the difficulty level of any of the books based primarily on an individual reader’s established reading skills (typically an aspect of their fluency and/or comprehension) but also related to other factors, such as the reader’s background knowledge, linguistic knowledge, or motivation. In this conceptualization of text/reader/task, individual readers’ reading accuracy, reading rate, comprehension, background or linguistic knowledge, and/or motivation provide the orientation, and the assumption is that the difficulty of a given text could vary according to the specific reader.

Although task was not often a central focus of the studies reviewed, we coded for the support provided during measurement and the length of outcome measure or reading material. The majority of studies were not interventions and thus did not provide support for students in what was a testing context. However, minimal to moderate support was provided either before or during reading in the remaining studies. Whether or not support was provided tended to depend on the context of each research study. The length of the outcome measure or reading material varied from one-minute timed samples to untimed measures of whole texts to standardized tests of reading comprehension. This range also seemed to depend on the context of the research studies.

Text Difficulty and Reading Fluency

Results from the current study suggest that on average, as the level of text difficulty increases, students’ accuracy and reading rate decreased, particularly for less skilled readers. One logical explanation for such a finding is how text difficulty is typically measured. For example, Lexile scores are calculated using a formula that incorporates sentence length and the commonality of individual words (e.g., Stenner and Fisher 2013). Logically, on average, one might expect most students’ reading accuracy, rate, and prosody to decline as they encounter increasingly longer sentences that contain less common words.

In our review, there were notable differences in the findings based on the skill level of the readers (e.g., Cheatham et al. 2014; Young and Bowers 1995). Differences in findings by readers’ skill-levels held true for all aspects of fluency—accuracy, rate, and prosody. For younger or less skilled readers, on average, increased text difficulty was related to decreased accuracy, rate, and prosody. However, for skilled readers, different from findings related to accuracy and rate, one study showed that prosody could actually improve as text difficulty increased. More complex texts include longer sentences and phrasing that would lend themselves to more prosodic readings and Benjamin and Schwanenflugel (2010) noted that more skilled readers actually “seemed to marshal prosodic resources” (p. 399) to read these texts.

Findings related to fluency also differed based on how text difficulty was conceptualized and measured (e.g., Chinn et al. 1993; Compton et al. 2004). For example, in one study improved reading rates were related to reading easier texts, defined as those with greater percentages of high-frequency words and/or a greater percentage of decodable words (Compton et al. 2004). Findings also differed based whether support or scaffolding was provided during reading, such as reading aloud to an adult who provided support and motivation (O’Connor et al. 2010), when reading a text previously read aloud by the teacher (Hoffman et al. 2001), or when engaging in repeated readings (Faulkner and Levy 1994; Sindelar et al. 1990). These findings make sense—the greater the support received by students during reading, on average, the better their fluency.

Text Difficulty and Reading Comprehension

Overall, we found that when text difficulty increased, there was either a negative relationship to comprehension or a non-significant one. In no study did a higher difficulty relate to greater comprehension. That said, it may be important to consider the degree of text difficulty. In one study, some increased difficulty was better than no increase at all, but students struggled when text was too difficult (Topping et al. 2008). This finding may align with previous discussion on theory (e.g., Vygotsky 1978): students may have a “zone of proximal development” (p. 86) for text difficulty or they may need some prerequisite level of fluency in order to comprehend more difficult texts (see Samuels 2013 for a discussion of the facilitative role of fluency on comprehension).

It is important to remember that differences in this construct could easily be due to issues related to measurement. The measurement of comprehension has historically been plagued by problems (Fletcher 2006; Sabatini et al. 2012). In comparison to fluency, which is a relatively clear construct, comprehension is a complex, unconstrained construct that continues to develop over time (Paris 2005). As such, there are many different ways to assess it (Pearson and Hamm 2005) and studies have demonstrated that students’ outcomes on comprehension measures vary considerably, depending on the measure used (Conradi et al. 2016; Keenan et al. 2008). The lack of consensus established in this review could actually be a function of differences in on measures used across studies. With advances in comprehension measurement (Sabatini et al. 2012), we have much to gain in understanding how comprehension is related to text difficulty.

On a related note, certain aspects of comprehension might be more sensitive to changes in text difficulty than others. O’Connor et al. (2002) contend that a measure of vocabulary might have been more sensitive to text difficulty differences and that students participating in a reading intervention with texts matched at their grade level (that were more difficult from texts matched at students’ instructional levels) were exposed to higher vocabulary words in their intervention. This holds significant implications for researchers who should consider the effects of text difficulty on more discrete measures of language or inferencing skills.

Finally, the contexts of the studies themselves may have also contributed to a lack of consensus in results. Interestingly, three of the five studies that demonstrated no relationship between text difficulty and comprehension were intervention studies where some degree of scaffolding and support was provided for students during intervention (Morgan et al. 2000; O’Connor et al. 2002, 2010). These studies showed that students may be able to access more difficult texts when provided a certain level of support. Still, there was no evidence that students performed better with more difficult texts; instead, given support, on average, they performed as well as they did with less difficult texts. Careful study is needed of the types of support/scaffolds that can be provided to students reading difficult texts and how those might lead to better comprehension.

Implications

Although variation in how studies operationalized text difficulty somewhat complicates the findings established in the review, results nevertheless suggest evidence of a relationship between the degree of text difficulty and students’ reading fluency and comprehension. Implications for theory, research, and policy, curriculum, and instruction are discussed below.

Implications for Theory

The lack of theoretical frameworks undergirding much of the work presented in this review signals the need for a more refined, comprehensive theory of text difficulty. Although theories exist that capture how readers might rely differentially on skills when reading (e.g., Interactive Compensatory Theory; Stanovich 1980), we lack a theory that also captures how that reader shifts or compensates when encountering increasingly difficult texts. The absence of such a theory is likely due the sheer complexity of the issue. A reading outcome is affected not only by many text characteristics and student-centered variables but also the tasks, contexts, and scaffolding of the teacher (e.g., RAND Reading Study Group 2002).

Some question the sufficiency of the RAND heuristic, however, in capturing the interactions of these three aspects. Cunningham, for example, questions whether the three parts should be treated equally: in short, does reading comprehension always require a “task,” and still—are readers and text weighted equally in terms of how they might affect one another (Cunningham 2016, December). Mesmer et al. (2012) present a compelling initial step to considering text challenge for beginning readers, when word recognition still requires significant cognitive resources. Previous and future research can confirm or disconfirm their model, allowing it to be revised and updated as needed. However, we propose that researchers must consider a similar model for fluent readers, when automaticity has been achieved with word recognition, freeing up cognitive resources for text-level analyses.

Implications for Research

Much of the research and practice of the past 20 years has dealt with how to support students with instructional level reading, consistent with Betts’ (1946) view, described earlier. Researchers have addressed instructional level reading as part of intervention (e.g., Schwartz 2005) as well as more general classroom instruction (e.g., Iaquinta 2006), but there is little research, and certainly no consensus, on the best ways to support students in reading more challenging texts (i.e., frustration level, according to Betts 1946). At the same time, there is little evidence to suggest that Betts’ guidelines––or various adaptations of Betts, like those used by Fountas and Pinnell (1996), Leslie and Caldwell (2011), or Morris (2008)—hold any standing (e.g., Cunningham 2013). While there is a long history of employing thresholds for accuracy in considering text difficulty, no definitive word recognition percentage exists to guide matching readers with texts. Instead, research on reading instruction should likely consider how aspects of the text, (such as its structure, cohesion, or narrativity) might interact with the reader’s word recognition and comprehension skills.

Implications for Policy, Curriculum, and Instruction

This review was instigated by the adoption of the Common Core State Standards, which call for an increase in the complexity of texts that students encounter in U.S. classrooms. Although the goal of having elementary students read more complex texts may be worthy, the design and enactment of the corresponding state and federal policies was based on a limited evidence base (Hiebert 2011/2012); in fact, some argue that the text reading levels recommended by the CCSS actually preceded a clear evidence base (Pearson, 2013; Pearson and Hiebert, 2013). A review of the research, such as the present one, suggests that the implications of this policy may not be necessarily positive. When students read texts that are more challenging, various reading outcomes tend, as a whole, to decline. If we give students more complex texts without any support, we are unlikely to see the intended benefits of the policy. Any future instantiations, therefore, need to be considerate of the types of contexts necessary to facilitate students’ successful reading of complex texts. Specifically, we draw attention to the importance of scaffolds and instructional supports to assist students as they read more challenging texts.

Appropriate evidence-based instructional techniques for supporting students’ reading of more complex texts must be established. Moreover, it is likely that these supportive techniques will vary according to students’ developmental stage of reading, characteristics of the text itself, as well as characteristics of the instructional task or activity (RAND Reading Study Group 2002). If students are to read more complex texts, commensurate with the CCSS guidelines for text complexity (see NGACBP and CCSSO 2010, Appendix A)—we must attend to the types of scaffolds necessary in order to avoid negative repercussions. Three intervention studies (Morgan et al. 2000; O’Connor et al. 2002, 2010) included in this review demonstrated no significant differences for reading comprehension when students read texts that were more difficult than others. In each of these studies, students were receiving fluency support, whether from peers (Morgan et al. 2000) or in a supportive small-group setting from their teacher (O’Connor et al. 2002, 2010). These findings echo previous work (Stahl and Heubach 2005) about the benefits of reading difficult texts with others within supportive instructional contexts.

Furthermore, the expectation that teachers include more complex texts in their classrooms must be accompanied by professional development for teachers to build a clearer understanding of what makes one text more complex than another. Teachers are often left to rely on disparate and even competing metrics—that often privilege certain aspects of text complexity (word and sentence length) over others. Currently, researchers use a variety of metrics to determine text complexity that are often inaccessible to practitioners. Other metrics are available to teachers but relatively unknown. For example, the Text Easability Assessor (Graesser et al. 2014), available to the public, provides scores for texts based on five characteristics, including narrativity, syntactic simplicity, word concreteness, referential cohesion, and deep cohesion. If teachers were to be made aware of additional text features that contribute to a text’s complexity, they may be able to provide more effective support for students.

In the CCSS Appendix, the authors stated that the “development of new and improved text complexity tools should follow the release of the Standards as quickly as possible” (NGACBP and CCSSO 2010, p. 8), yet this recommendation remains unrealized. We renew this call for development of new and improved text complexity tools, especially one for practical, everyday use in schools by teachers, administrators, and students. Any newly developed tools should support teachers in not only determining text complexity but also in using professional judgment to consider text difficulty for individual students based on a variety of factors.

Limitations and Future Research

Although important findings related to research on text difficulty were detailed in the current review, as with all studies, there were limitations that should be stated. Additionally, through conducting the review, clear directions for future research became apparent.

For inclusion in this review, studies had to clearly demonstrate that text difficulty was an independent variable, framing how one text might be perceived as more difficult than another. This operationalization meant that we did not include studies that might have used the same text but manipulated other factors potentially related to text difficulty. For example, how might reading a short passage from one text be different from reading a considerably longer passage from the same text? Or, how might students fare reading a text with no support versus differing levels of support? Future research should investigate this more closely.

We also imposed strict contextual and methodological limits on studies included in the review. While we stand by our limits, a wider body of studies may have included additional findings. Though beyond the scope of a general review, descriptive studies that attend to both cognitive and motivational behaviors displayed by students as they read increasingly difficult texts could broaden our understanding of this issue.

Furthermore, since we were specifically interested in the effects of implementing the increased levels of text difficulty from the CCSS with elementary students, we limited our search to studies conducted with elementary students. Research findings for students in grades 6–12, or even for students in college and university settings, may prove different than those for elementary students and should be the focus of future review.

Finally, as already acknowledged, implications drawn from this effort are necessarily limited by competing conceptualizations and the consequent lack of clarity within the field. We call for greater coherence: situated within theory, future researchers should better define and operationalize text complexity, text difficulty, and other related constructs. Until some consensus is reached, the impact of any reviews will be weakened.

Notes

The text levels (460 L and 770 L) presented for each book represent the Lexile scores for each text. See https://lexile.com for an explanation of how the Lexile score is derived.

References

Aardema, V. (1975). Why mosquitoes buzz in people’s ears. New York: Puffin Books

Allington, R. L. (1984). Oral reading. In P. D. Pearson, R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, & P. Mosenthal eds. Handbook of reading research. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum,.Vol. 1, pp. 829–864

Alvermann, D. E., Fitzgerald, J., & Simpson, M. (2006). Teaching and learning in reading. In P. A. Alexander & P. H. Winne eds., Handbook of educational psychology 2nd ed., Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum. pp. 427–455

Amendum, S. J., Conradi, K., & Liebfreund, M. D. (2016). The push for more challenging texts: an analysis of early readers’ rate, accuracy, and comprehension. Reading Psychology, 37, 570–600. doi:10.1080/02702711.2015.1072609.

Amendum, S. J., & Fitzgerald, J. (2011). Reading instruction research for English-language learners in kindergarten through sixth grade: the last fifteen years. In R. Allington & A. McGill-Franzen eds., Handbook of reading disabilities research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. pp. 373–391

Ardoin, S. P., Suldo, S. M., Witt, J., Aldrich, S., & McDonald, E. (2005). Accuracy of readability estimates’ predictions of CBM performance. School Psychology Quarterly, 20, 1–22. doi:10.1521/scpq.20.1.1.64193.

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64, 359–372. doi:10.1037/h0043445.

Benjamin, R. G. (2011). Reconstructing readability: recent developments and recommendations in the analysis of text difficulty. Educational Psychology Review, 24, 63–88. doi:10.1007/s10648-011-9181-8.

Benjamin, R. G., & Schwanenflugel, P. J. (2010). Test complexity and oral reading prosody in young readers. Reading Research Quarterly, 45, 388–404. doi:10.1598/rrq.45.4.2.

Betts, E. A. (1946). Foundations of reading instruction. New York: American Book.

Biemiller, A. (1970). The development of the use of graphic and contextual information as children learn to read. Reading Research Quarterly, 6, 75–96. doi:10.2307/747049.

Biemiller, A. (1979). Changes in the use of graphic and contextual information as functions of passage difficulty and reading achievement level. Journal of Literacy Research, 11, 307–318. doi:10.1080/10862967909547337.

Blaxall, J., & Willows, D. M. (1984). Reading ability and text difficulty as influences on second graders’ oral reading errors. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(2), 330–341. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.76.2.330.

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18, 32–42. doi:10.3102/0013189x018001032.

Cecconi, C. P., Hood, S. B., & Tucker, R. K. (1977). Influence of reading level difficulty on the disfluencies of normal children. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research, 20, 475–484.

Chall, J. S. (1996). Stages of reading development 2nd ed. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace.

Chall, J. S., & Dale, E. (1995). Readability revisited: the new Dale–Chall readability formula. Cambridge: Brookline Books.

Cheatham, J. P., Allor, J. H., & Roberts, J. K. (2014). How does independent practice of multiple-criteria text influence the reading performance and development of second graders? Learning Disability Quarterly, 37, 3–14. doi:10.1177/0731948713494016.

Chinn, C. A., Waggoner, M. A., Anderson, R. C., Schommer, M., & Wilkinson, I. A. G. (1993). Situated actions during reading lessons: a microanalysis of oral reading error episodes. American Educational Research Journal, 30, 361–392. doi:10.2307/1163240.

Clifford, M. M. (1984). Thoughts on a theory of constructive failure. Educational Psychologist, 19, 108–120. doi:10.1080/00461528409529286.

Compton, D. L., Appleton, A. C., & Hosp, M. K. (2004). Exploring the relationship between text-leveling systems and reading accuracy and fluency in second-grade students who are average and poor decoders. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 19, 176–184. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5826.2004.00102.x.

Conradi, K., Amendum, S. J., & Liebfreund, M. D. (2016). Explaining variance in comprehension for students in a high-poverty setting. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 32, 427–453. doi:10.1080/10573569.2014.994251.

Cramer, K., & Rosenfield, S. (2008). Effect of degree of challenge on reading performance. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 24, 119–137. doi:10.1080/10573560701501586.

Cunningham, J. W. (2013). Research on text complexity: the Common Core State Standards as catalyst. In S. B. Neuman & L. Gambrell (Eds.), Quality reading instruction in the age of common core. Newark: International Reading Association.pp. 136–148

Cunningham, J. W. (2016). RAND’s reading comprehension heuristic, 14 years later. In “There is nothing so practical as a good theory”: looking at theory and text complexity, symposium conducted at the annual meeting of the Literacy Research Association: Carlsbad.

Dahl, R. (1975). Danny, the champion of the world. New York: Puffin Books.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: the new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books.

Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., & Schiefele, U. (1998). Motivation to succeed. In W. Damon & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology 5th ed. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 1017–1095

Ehri, L. C. (1991). Development of the ability to read words. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research Vol. 2,. New York: Longman. pp. 383–417

Ehri, L. C., Dreyer, L. G., Flugman, B., & Gross, A. (2007). Reading rescue: an effective tutoring intervention model for language-minority students who are struggling readers in first grade. American Educational Research Journal, 44, 414–448. doi:10.2307/30069443.

Faulkner, H. J., & Levy, B. A. (1994). How text difficulty and reader skill interact to produce differential reliance on word and content overlap in reading transfer. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 58, 1–24. doi:10.1006/jecp.1994.1023.

Fitzgerald, J. (1995). English-as-a-second-language learners’ cognitive reading processes: a review of research in the United States. Review of Educational Research, 65, 145–190.

Fletcher, J. M. (2006). Measuring reading comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 10, 323–330.

Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (1996). Guided reading: good first teaching for all children. Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (1999). Matching books to readers: using leveled books in guided reading, K-3. Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Fry, E. (1968). A readability formula that saves time. Journal of Reading, 11, 513–516.

Goldman, S. R., & Lee, C. D. (2014). Text complexity. State of the art and the conundrums it raises. The Elementary School Journal, 115, 290–300. doi:10.1086/678298.

Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), 6–10. doi:10.1177/074193258600700104.

Graesser, A. C., McNamara, D. S., Cai, Z., Conley, M. W., Li, H., & Pennebaker, J. (2014). Coh-Metrix measures text characteristics at multiple levels of language and discourse. The Elementary School Journal, 115, 210–229. doi:10.1086/678293.

Graesser, A. C., McNamara, D. S., & Kulikowich, J. M. (2011). Coh-Metrix: providing multilevel analyses of text characteristics. Educational Researcher, 40, 223–234. doi:10.3102/0013189x11413260.

Gray, W. S. (1915). Standardized oral reading paragraphs test. Bloomington: Public School Publishing Co.

Halladay, J. L. (2012). Revisiting key assumptions of the reading level framework. The Reading Teacher, 66(1), 53–62. doi:10.1002/trtr.01093.

Hiebert, E. H. (2011). The common core’s staircase of text complexity: getting the size of the first step right. Reading Today, 29(3), 26–27.

Hiebert, E. H., & Fisher, C. W. (2007). Critical word factor in texts for beginning readers. The Journal of Educational Research, 101, 3–11. doi:10.2307/27548210.

Hiebert, E. H., & Mesmer, H. A. (2013). Upping the ante of text complexity in the Common Core State Standards: examining its potential impact on young readers. Educational Researcher, 42, 44–51. doi:10.3102/0013189x12459802.

Hiebert, E. H., & Raphael, T. E. (1996). Psychological perspectives on literacy and extensions to educational practice. In D. C. Berliner & R. Calfee (Eds.), Handboook of educational psychology. New York: MacMillan. pp. 550–602

Hintze, J. M., Daly, E. J., & Shapiro, E. S. (1998). An investigation of the effects of passage difficulty level on outcomes of oral reading fluency progress monitoring. School Psychology Review, 27, 433–445.

Hoffman, J. V., Roser, N. L., Salas, R., Patterson, E., & Pennington, J. (2001). Test leveling and ‘little books’ in first-grade reading. Journal of Literacy Research, 33, 507–528. doi:10.1080/10862960109548121.

Hunt, L. C. (1970). The effect of self-selection, interest, and motivation upon independent, instructional, and frustational levels. The Reading Teacher, 24, 146–158.

Iaquinta, A. (2006). Guided reading: a research-based response to the challenges of early reading instruction. Early Childhood Education Journal, 33, 413–418. doi:10.1007/s10643-006-0074-2.

Kapur, M. (2008). Productive failure. Cognition and Instruction, 26, 379–424. doi:10.1080/07370000802212669.

Keenan, J. M., Betjemann, R. S., & Olson, R. K. (2008). Reading comprehension tests vary in the skills they assess: differential dependence on decoding and oral comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 12, 281–300. doi:10.1080/10888430802132279.

Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension: a paradigm for cognition. New York: Cambridge Univerisity Press.