Abstract

A growing body of literature is demonstrating associations between childhood maltreatment and bullying involvement at school. In this literature review, four potential mediators (explanatory) and three potential moderators (mitigates or exacerbates) of the association between childhood maltreatment and school bullying are proposed. Mediators include emotional dysregulation, depression, anger, and social skills deficits. Moderators reviewed include quality of parent–child relationships, peer relationships, and teacher relationships. Although there might be insurmountable challenges to addressing child maltreatment in primary or universal school-based prevention programs, it is possible to intervene to improve these potentially mediating and moderating factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A recent report from the US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth and Families (2009) indicates that approximately three million cases of child maltreatment are reported annually. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, child maltreatment is defined as any act or series of acts of commission (physical, emotional, and sexual abuse) or omission (neglect) by a parent or a caregiver, which results in harm, potential for harm, or threat of harm to a child (Leeb et al. 2008). The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act also defines child maltreatment as “any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker that results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse, or exploitation or that presents an imminent risk of serious harm” (as cited by Child Welfare Information Gateway 2007). Since the 1960s, child maltreatment has been a major focus of social research (Tajima 2004), and during the past 30 years, there has been unprecedented interest in child outcomes associated with experiences in maltreatment (English 1998). Findings from studies have consistently reported that children and adolescents who are physically, emotionally, and sexually abused are likely to engage in risk-taking (Bornovalova et al. 2008; Holmes 2008; Roode et al. 2009) and delinquent (Stewart et al. 2008) behaviors.

Recent events in the USA such as school shootings and bullycide (i.e., suicide attributed to bullying victimization) have also generated a major research interest in understanding factors that are associated with children’s experiences in bullying perpetration and victimization in school (see Garbarino 2004). Although a number of definitions of bullying perpetration and victimization exist in research, bullying is commonly identified as verbal, physical, or social forms of aggression inflicted by an individual or a group of individuals and directed against a child or adolescent who is not able to defend himself or herself (for a review, see Espelage and Swearer 2003). Individuals can be perpetrators, victims, or both. Bullying perpetration and victimization differ from normal peer conflict because the aggression is proactive, intentional, and repeated and involves differential power relationships (Olweus 1993). Although the exact prevalence of bullying perpetration and victimization in schools is difficult to ascertain due to variations in the measures across studies (Espelage and Horne 2008; Espelage and Swearer 2003), findings from several studies suggest that bullying is a common occurrence in schools. The National Center for Education Statistics of the US Department of Justice found that, in 2007–2008, 25% of public schools reported that bullying was a daily or weekly occurrence (Robers et al. 2010). Studies also consistently report several negative outcomes associated with bullying perpetration and victimization in school, such as depression (Klomek et al. 2008; Klomek et al. 2007; Sourander et al. 2009), psychopathologic behaviors (Kim et al. 2006), health problems (Rigby 2003), and suicidal behaviors (Klomek et al. 2009).

Family is where children first observe and experience interpersonal relationships; it is through the family that children learn what to expect, how to behave, and the necessary interpersonal skills in relationships outside of the home (Stocker and Youngblade 1999). Research has documented that maltreatment at home can potentially increase the risk of bullying perpetration and victimization in school (Duncan 1999; Dussich and Maekoya 2007), a relationship which can also be explained by several theories. For instance, attachment theorists argue that abuse during childhood can lead to the development of a negative or insecure attachment with an abusive caregiver (Cicchetti 1989; Toth et al. 1992), which can result in difficulties in establishing positive peer relationships in school. Social learning theorists hypothesize that aggressive behavior is learned and reinforced through child observation of parental modeling, of abusive caregivers, as well as of deviant and antisocial peers (Akers 1998; Bender 2010). Finally, life course theorists suggest that bonding to conventional people or institutions that adhere to law-abiding and prosocial behavior would enable children and adolescents to refrain from antisocial behaviors, such as bullying (Bender 2010; Sampson and Laub 1993). Youth who are abused or neglected during childhood may feel disconnected from conventional institutions (e.g., school) and might not develop this critical bond in turn (Bender 2010). Consequently, these youth may be more likely to engage in aggressive peer interactions.

Despite the significance of research findings and theoretical support, rarely do children who experience violence at home immediately become aggressive individuals (Grogan-Kaylor and Otis 2003; Moffitt and Caspi 2001; Widom 1989). Rather, violence emerges in some children through complex pathways where a developing child’s risk for violence increases with each added exposure to violence or engagement in misconduct as wells as continued exposure to deviant role models (Bender 2010; Moffitt and Caspi 2001). Consistent with Widom’s (1989) cycle of violence theory, abused and victimized children are at risk of engaging in violent and delinquent acts, yet this propensity is not always realized. Relatedly, children who are victimized at home are also likely to experience developmental, behavioral, interpersonal, and school-related problems, increasing their vulnerability and placing them at risk of bullying victimization in school.

The purpose of this article is to enhance our understanding of the relation between maltreatment and bullying perpetration and victimization by examining a number of potential mediating factors that can explain this association and moderating factors that can either exacerbate or reduce this association. A recent study by Bender (2010), which investigated the linkage between maltreatment and juvenile delinquency, suggested that research studies that focus on identifying mediators and moderators will assist greatly in designing and implementing programs to address the needs of these children and adolescents through child welfare and juvenile justice systems as well as school-based programs.

Current Findings and Research Gaps

Parent–child relationships at home can influence peer relationships outside the home (Bolger and Patterson 2001; Knutson et al. 2004; Mohr 2006; Ohene et al. 2006; Shields and Cicchetti 2001). Evidence from research suggests that childhood maltreatment experiences can place adolescents at risk of bullying victimization and perpetration in school. Findings from several studies also indicate that physical and sexual abuse (Duncan 1999; Mohr 2006; Schwartz et al. 1997) and parental neglect at home (Bolger and Patterson 2001; Bolger et al. 1998; Chapple et al. 2005) are significantly associated with greater peer rejection. The longitudinal study of Chapple et al. (2005) found that, in a representative community sample, youth who were emotionally and physically neglected by their parents during childhood were likely to be rejected by their peers in early adolescence and to subsequently develop violent tendencies during late adolescence.

Researchers have also found that abused children are likely to be submissive in an effort to maintain their safety in a violent home situation. These children become easy targets for peer rejection and bullying victimization outside the home (Schwartz et al. 1993) as they are unlikely to retreat or defend themselves when they are victimized by their peers (Shields and Cicchetti 2001). An earlier study by Browne and Finkelhor (1986) also proposed that children who are sexually or physically abused can develop a sense of powerlessness and lower self-confidence, lack of assertiveness, and inability to establish trust with others. Because of this sense of powerlessness, these children may come to expect to be harmed and consequently fail to protect themselves, all of which may lead bullying perpetrators to single them out for targets of bullying victimization.

Studies also report that bullying perpetration is a common outcome of child abuse and neglect (Bolger and Patterson 2001; Knutson et al. 2004; Knutson and Schartz 1997; Ohene et al. 2006). Several researchers have posited that children who are physically, emotionally, or sexually abused or neglected by their parents or primary caregivers are more likely to experience other forms of victimization outside the family (Cicchetti et al. 1992; Shields and Cicchetti 2001). Bolger and Patterson’s (2001) longitudinal study investigated peer rejection, aggressive behavior, and social withdrawal among a representative community sample of 107 maltreated (physical, emotional, and sexual abuse and neglect) and an equal number of nonmaltreated children. Findings indicate that experiences with abuse were associated with risk of peer rejection repeatedly from childhood to early adolescence and that abused children were significantly more likely to exhibit aggressive behavior, as reported by peers, teachers, and children themselves. The results held for both boys and girls, from childhood through early adolescence, which indicated that negative parent–child interactions can influence children’s aggressive behavior while leading to a failure to develop positive interpersonal skills. The researchers hypothesize that parents’ failure to use appropriate discipline techniques was a major predictor of children’s subsequent aggressive behavior. These researchers have confirmed the existence of maltreatment–bullying association.

Few research studies have focused on the potential mediating and moderating factors between child abuse and neglect and bullying behavior. One possible reason for this gap is that the research literature on bullying and those focusing on child maltreatment have largely developed independent of one another. Also, it is likely to be challenging to assess all forms of child maltreatment within school-based studies given the safeguards around mandated reporting of abuse. On one hand, child welfare research has identified numerous predictors of maltreatment. On the other hand, a body of school violence research studies has established several risk factors for bullying perpetration and victimization, which is consonant with the broader research literature linking parental behavior with the development of child behavior problems (Gershoff 2002; Gershoff et al. 2010). Bullying behavior encompasses various subcategories (see Hong and Espelage, forthcoming), such as physical, emotional, mental, and emotional aggression. Despite these subcategories, researchers have commonly identified bullying as a subset of aggressive behavior (Olweus 1993) directed against a particular individual or a group of individuals. Thus, mediating and moderating factors that are relevant to all forms of maltreatment (i.e., physical, psychological, emotional, and sexual abuse) and bullying perpetration and victimization (i.e., verbal, physical, and social aggression) were considered in this review. We suggest a number of potential mediating and moderating factors that need to be considered in research on child maltreatment and bullying perpetration and victimization, which overlap considerably.

Potential Mediating Factors

A mediator is a variable that intervenes between an independent variable and a dependent variable and that statistically explains some amount of the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable. For example, child maltreatment (independent variable) might be associated with depression in children (mediator), which then might in turn be associated with bullying perpetration (Baron and Kenny 1986). A mediator effect is often tested when there appears to be a significant direct effect between the predictor variable and outcome variable (Baron and Kenny 1986; Bennett 2000); however, when the association between the predictor and outcome variable is more distal (such as childhood abuse with adolescent outcomes), it is also permissible to proceed with the mediator analyses (Shrout and Bolger 2002). However, we should also note that, even if the relationship tends toward small effect sizes, it is not necessarily weak. In this section, four potential mediating factors explaining the maltreatment–bullying perpetration/victimization relationship are examined: (1) emotional dysregulation, (2) depression, (3) anger, and (4) social skills deficit.

Emotional dysregulation

Emotional dysregulation represents the first mediating factor, which can potentially explicate the relation between child maltreatment and bullying perpetration/victimization. Emotional dysregulation can be defined as the inability of an individual to recognize, understand, and modulate their emotions and to match their emotions to the reality of the situation around them (Gratz and Roemer 2004; see also Keenan 2000). Children who are unable to regulate their emotions may manifest both elevated levels of aggression and antisocial behavior, as well as heightened levels of depression and anxiety, that are not warranted by the particular social situation in which they are involved (Chang et al. 2003; Lee and Hoaken 2007). Children’s emotional dysregulation is recognized as a significant outcome of abuse (Gil et al. 2009; Kelly 1992). As research evidence suggests, physical and emotional abuse and neglect adversely affect children’s physical, cognitive, social, and emotional development, which can accumulate over time (English 1998). Glaser (2000) also argued that physical and emotional abuse and neglect are a potential source of stress, which can increase the likelihood of children’s emotional dysregulation. As noted earlier, child maltreatment impedes the ability of a child to develop health models of attachment. A large and growing body of literature has highlighted the importance of the development of healthy attachments in providing a child with the opportunity to develop some level of ability to emotionally regulate (see Cassady and Shaver 2008; Mikulincer et al. 2003; Zimmermann et al. 2001), which is associated with quality of peer relationships (Contreras and Kerns 2000; Contreras et al. 2000; Kerns et al. 2007). Consequently, when the development of healthy attachment bonds is disrupted, as in the case of situations where parents maltreat their children, the development of ability to emotionally self-regulate is seriously compromised.

Children transfer negative emotional response strategies they have acquired from their parents’ punitive and abusive emotions to other contexts (Chang et al. 2003). Until recently, there have been relatively few studies on the association between children’s emotional dysregulation and bullying perpetration or victimization. A limited number of studies have found that aggressive behavior in school is significantly high for children and adolescents with emotional dysregulation (Chang et al. 2003; Kaukiainen et al. 2002). The study of Chang et al. (2003) reports from a sample of 325 Chinese children and their parents that harsh parenting practices have direct and indirect effects on children’s aggressive behavior in school through the mediating process of children’s emotional dysregulation. Findings from a limited number of research studies also indicate that children with poorly regulated emotion are at risk of bullying victimization and peer rejection (Shields et al. 2001). There is a well-established literature linking emotional dysregulation to both increased aggression and antisocial behavior as well as to increased anxiety and depression (Leadbeater et al. 1999; Shields and Cicchetti 1998; Marsee and Frick 2007). Emotional dysregulation is particularly high among peer-victimized children who are also identified as aggressive (Schwartz and Proctor 2000; Schwartz et al. 2001; Toblin et al. 2005), compared to passive victims and bullies. Toblin et al. (2005) examined the social–cognitive and behavioral attributes of 240 children in a Los Angeles elementary school identified as “aggressive victims” (i.e., peer-victimized children who display aggressive behavioral tendencies) in comparison to those identified as bullies, passive victims, and normative comparison group. The researchers found that “aggressive victims” were characterized by impairment in emotional regulation and difficulties across domains of functioning. Aggressive victims may experience problems with displaying proper emotion, which can hamper their ability to successfully establish peer relationships in school and increase the likelihood of bullying victimization. Consequently, these children might exhibit aggressive behavioral tendencies as a result.

Depression

Depression is the second potential mediator, which explains the association between maltreatment and bullying perpetration or victimization (Fig. 1). Studies have consistently shown that physically, emotionally, or sexually abused youth report high levels of internalizing behaviors, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (Grassi-Oliveira and Stein 2008; Lev-Wiesel et al. 2009; Runyon and Kenny 2002) and depression (Danielson et al. 2005; Gilbert et al. 2009; Stuwig 2005; Turner et al. 2006) during childhood, as well as adolescence and adult years (Hussey et al. 2006; Johnsona et al. 2002; Runyon and Kenny 2002; Stuewig and McCloskey 2005). Such findings are congruent with the growing cross-cultural research literature linking harsh parenting and harsh physical discipline to increases in internalizing behavior (Gershoff et al. 2010; Han and Grogan-Kaylor 2011).

Depression has also been empirically linked to bullying victimization and perpetration by a limited number of researchers. Studies have reported that depression has been found to be a common mental health symptom experienced by victims of bullying (for a review, see Espelage and Swearer 2003). Longitudinal studies have found that bullying victims (Klomek et al. 2008; Sourander et al. 2009) and perpetrators (Klomek et al. 2007) are likely to be at risk for subsequent depression. Researchers also report that depression is a predictor of bullying victimization (Klomek et al. 2007; Espelage et al. 2001; Fekkes et al. 2004). A study by Fekkes et al. (2006), which examined the association between health-related symptoms and bullying victimization among 1,118 school-age children in the Netherlands, found that children with depressive symptoms were significantly more likely of being newly victimized by their peers than children who had a history of victimization. The researchers theorized that depressed or anxious behaviors could make the child an easy target for bullying victimization, as they appear to be more vulnerable than children without depression or anxiety. These children are perceived as less likely to stand up for themselves when they are picked on, and the perpetrators may fear less retaliation from them.

Anger

The third potential mediator, which may explain the relationship of maltreatment to bullying perpetration and victimization, is anger. Studies consistently report that anger is a common adaptive response to physical, emotional, and sexual abuse and neglect (Bennett et al. 2005; Briere and Elliott 2003; Harper and Arias 2004; Springer et al. 2007). Victims of abuse struggle with unexplained emotions such as anger and hostility throughout childhood and then adult years. Springer et al. (2007) explored the impact of physical abuse on mental and physical health of 2,000 men and women, controlling for family background and childhood adversities. Findings from the study indicate that childhood physical abuse by parents was a significant correlate of anger, depression, and anxiety.

Anger has also been consistently found to be a significant predictor of bullying and aggression among children and adolescents (Arsenio and Lemerise 2001; Bosworth et al. 1999; Camodeca and Goossens 2005; Espelage et al. 2001). In particular, anger is a key element of reactive aggression (i.e., a defensive response to abuse, which involves both bullies and victims) than proactive aggression (i.e., goal-directed and deliberate action in order to achieve one’s goals and involves bullies only; Roland and Idsoe 2001). One study (Camodeca and Goossens 2005), which examined social information processing and emotion in a bullying situation (both reactive and proactive aggression) of 242 Dutch children, found that both bullies and victims were more likely to exhibit anger and aggressive behavior, compared to children identified as bullies only and those who were not involved in bullying situations. Moreover, anger has also been found to mediate the association between maltreatment at home and peer aggression in school, as indicated in one research finding (Dodge 1991). Dodge’s (1991) study found that children’s experience with physical abuse and neglect is a pathway to the development of angry and hypervigilant style of interpersonal interactions that could lead to aggressive behaviors toward peers. These findings suggest that anger is a common reaction to abuse in various settings (e.g., home, school). Victimized children may be easily angered and retaliate through bullying and aggression (Arsenio and Lemerise 2001).

Social skills deficit

The fourth and final potential mediating factor that could explain the pathway from maltreatment to bullying behavior is that of social skills deficit. Social skills are critical to successful functioning for children and adolescents in school (Schneider et al. 1989). Healthy and prosocial participation in peer and school settings requires the ability to develop social skills to negotiate situations of potential conflict and disagreement. Most recently, researchers have investigated a wide range of correlates and consequences of poor social skills among children and adolescents (Fox and Boulton 2005). Earlier research studies have documented that experiences of physical abuse and neglect can be detrimental to a child’s emotional and social skills development (e.g., Browne and Finkelhor 1986; Trickett and Kuczynski 1986; Zingraff et al. 1993). A more recent study by Ohene et al. (2006) also reports that children whose parents employ harsh and abusive disciplinary practices run the risk of developing poor social skills outside the home. Abused and neglected children are more likely to experience difficulty in forming secure attachments with their caregivers than nonabused children. Lack of secure attachments frequently leads to difficulties in establishing positive social relationships outside the family. A study by Elliott et al. (2005), which examined the link between physical abuse and social isolation from the National Youth Survey, reported that youth who experienced violence were found to be more socially isolated from their friends and from school than those who had not been physically abused. The researchers note that additional research is needed to identify additional mediators of the connection between physical abuse and social isolation. However, the authors theorized that, not only is abuse detrimental to secure attachment to others, but lack of attachments to others is related to compromised social skills development and low self-esteem, which in turn are associated with social isolation. Interestingly, one study also reported that parents who physically abuse their children are isolated from their own personal social support networks, which may further influence children’s social development because the children are also isolated from role models of adults exhibiting positive social relationships (Howe and Espinosa 1985). Although the researchers found that abused children in newly formed peer groups were less socially competent than nonabused children, abused children in well-established peer groups were similar to nonabused children in frequency of social interactions and in their expression of positive emotions. They concluded that abused children might benefit from social skills instruction when interacting within well-established peer groups.

Several researchers consistently report that children with poorly developed social skills and those who are socially withdrawn are more likely to experience negative interpersonal relations outside the home, such as bullying and peer conflicts (Champion et al. 2003; Dill et al. 2004; Fox and Boulton 2005). An earlier study by Elliott (1991) found that “bully victims lack social skills, have no sense of humour [humor], have a serious ‘demeanor’ and are incapable of the relaxed give and take of everyday life” (p. 11), which suggests that social skills training programs for bully victims are indicated (DeRosier 2004; Fox and Boulton 2003). A limited number of studies also report that victims of bullying display nonassertive behavior, making them vulnerable to victimization (Champion et al. 2003; Schwartz et al. 1993). Champion et al. (2003), for example, found from a sample of 54 early adolescents classified as “nonbullying victims” that these adolescents have subtle difficulties managing confrontation adaptively in various situations where peer interactions occur. These types of behaviors mark children out as easy targets. Once they are targeted for victimization, these individuals reward the bullying perpetrators through acts of submission (Schwartz et al. 1993).

Potential Moderating Factors

A moderator is a categorical variable (e.g., gender, race) or continuous variable (e.g., social support, school belonging) that affects or modifies the strength, and possibly even the direction, of the association between an independent variable and a dependent variable (Baron and Kenny 1986). Moderators imply that relations of two variables vary across levels of a third variable—the moderator (Hinshaw 2007). An examination of moderating factors is important in investigating when or under what conditions the relationship is likely to occur between the independent and dependent variables. A number of researchers have commonly identified parent-, peer-, and school-level risk factors for bullying victimization and perpetration in school (for a review, see Hong and Espelage, forthcoming). However, little is known empirically as to whether these factors can also potentially inhibit bullying perpetration and victimization.

In this section, three potential moderating factors that could potentially buffer the link between maltreatment and bullying perpetration or victimization are explored: (1) parent–child relationship, (2) peer relationship, and (3) teacher relationship.

Parent–child relationship

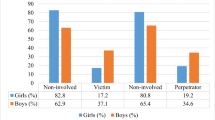

Empirical evidence from research findings suggest that hostile, conflictive, and distant parent–child relationships are evident in abusive homes and are associated with negative child outcomes, such as bullying perpetration and victimization (Fig. 2) (Espelage and Swearer 2003; Hong and Espelage, forthcoming). However, despite the presence of maltreatment, a secure relationship and attachment to a nonabusive parent or other caring and supportive adult figure has also been reported as a moderator, which mitigates the negative effects of childhood physical, emotional, and sexual abuse (Aspelmeier et al. 2007; Bacon 2001; Egeland et al. 1993; Herrenkohl et al. 1994). Aspelmeier et al. (2007) examined the relations between attachment security and psychological functioning of 324 female university students who reported experiencing sexual abuse during childhood. Results from the research indicate that positive relationship and attachment security in parent and peer relationships buffered the negative outcomes of child sexual abuse (e.g., trauma). Other researchers also reported that maltreated children and adolescents who had at least one supportive parent were more likely to develop self-confidence and experience mastery of the environment (Egeland et al. 1993) and remain in school (Herrenkohl et al. 1994). There are parallels in the broader literature on parenting, which provides limited evidence that the presence of a warm and supportive relationship with a parent may, to some extent, offset the degree to which harsh parenting is associated with the development of problem behaviors. However, it is worth noting that, even though a warm and supportive relationship with parents may somewhat moderate other aspects of parenting, an important review of the literature on physical discipline found evidence of many studies that indicated that the relationship between physical punishment and undesirable child outcomes persisted even in the presence of warm and supportive parenting (Gershoff 2002).

Parent–child relationships shape children and adolescents’ interpersonal relationship and socialization skills outside of the family environment. Researchers have consistently found that positive familial relationships and supportive adult figures also reduce youths’ propensity to engage in bullying behavior (Baldry and Farrington 2005; Espelage et al. 2000). A study by Baldry and Farrington (2005), which consisted of a sample of 679 male adolescents in an Italian high school, reported that the quality of family relationships could foster or inhibit youths’ experiences with bullying and victimization. Results suggested that youth whose parents were characterized as punitive, or with whom youth had a conflictual relationship, were at a heightened risk of bullying and victimization, while those with supportive and authoritative parents were less likely to be involved in bullying and victimization. Findings from the research of Espelage et al. (2000), which included 558 middle school students in the USA, also indicated that parental physical discipline was positively associated with bullying behavior, while the presence of positive adult role modeling in the home reduced youths’ propensity for engaging in bullying at school. Thus, it is imperative that researchers and practitioners further assess the quality of parent–child relationships and parenting practices when examining factors that are associated with bullying and victimization.

Relationship with peers

A youth’s relationship with peers is the second potentially relevant moderating factor. Negative peer relationships (e.g., deviant peer affiliation) can exacerbate adverse outcomes associated with maltreatment, such as bullying perpetration and victimization. In contrast, positive peer relationships might buffer the effects of maltreatment. Relatively few studies have examined the relations between maltreatment and children’s peer association (Fergusson and Horwood 1999; Herrenkohl et al. 2003; Tyler et al. 2003). Nevertheless, these studies have found that children who are physically, emotionally, or sexually abused at home are more likely to become “loners” or to establish friendships with deviant and antisocial peer groups (see also Bender 2010). Likewise, youth who were frequently maltreated are more likely to run away from home where they are susceptible to deviant peer affiliation. This is evident in the study of Tyler et al. (2003), which investigated the impact of childhood sexual abuse on later sexual victimization among 372 homeless youth in Seattle. The researchers reported that sexually abused youth who ran away from home and became homeless then interacted with deviant peers and engaged in risky sexual practices. Moreover, a limited number of studies have also found that maltreated children who are placed in residential care or group home settings through the child welfare system also are likely to be exposed to negative peer influences (Bender 2010; Dishion et al. 1999; Ryan et al. 2008). In contrast, Lee and Thompson (2009) reported that positive peer influences in a group home setting could potentially buffer the iatrogenic effects of peer group association and relationships by providing structure and expectations for behavior.

Adolescence is a developmental time when friendships and peer affiliations are crucial for healthy identity and social development. Adolescents seek autonomy from their caregivers and turn to their friends and peers for social support (Hong and Espelage, forthcoming). Findings from a number of researchers (Barboza et al. 2009; Holt and Espelage 2007; Mouttapa et al. 2004; Rodkin and Hodges 2003; Schmidt and Bagwell 2007) suggest that peer association is correlated with involvement in bullying situations. Thus, it is no surprise that negative peer affiliations can be a significant predictor for bullying and aggressive behavior. Longitudinal studies reveal that “deviancy and antisocial training” within adolescent friendships are predictors for subsequent delinquent behavior, substance use, and aggressive behaviors (Dishion et al. 2002; Poulin et al. 2001; Weiss et al. 2005). Findings from two experimentally controlled intervention studies of Dishion et al. (1999) suggest that high-risk adolescents are particularly vulnerable to aggressive peer interactions, compared with low-risk adolescents.

However, positive peer relationships characterized as having high levels of peer acceptance and social support can also be a protective factor against bullying victimization, as evident in research findings. Demaray and Malecki’s (2003) research findings indicate that youth with high levels of peer acceptance and peer social support are less likely to be victimized by their peers at school. In addition to peer acceptance and social support, positive friendships can also protect youth from bullying victimization (Bollmer et al. 2005; Hugh-Jones and Smith 1999; Schmidt and Bagwell 2007). Rigby (2005) found that positive peer relationships and friendships reduced the likelihood of bullying victimization in school among a sample of 400 elementary and middle school students in Australia.

Relationship with teachers

The third potential moderator for the relationship of child maltreatment with bullying perpetration or victimization is children’s relationships with teachers at school. A limited number of research findings suggest that physically, emotionally, or sexually abused children face barriers to normal developmental activities, which manifest as poor coping skills in the classroom and school (Miller 2003). Consequently, these children develop negative relationships with their teachers at school (Lynch and Cicchetti 1992). On the other hand, some maltreated children with an insecure attachment with their abusive caregiver may turn to teachers as an alternative or secondary attachment figure. Considering that children have frequent contact with their teachers at school, some maltreated children might seek supportive experiences with caring and involved teachers or other nonabusive adult figures (see Lynch and Cicchetti 1992).

The quality of teacher–student relationships can also determine whether children are likely to engage in bullying at school. Teacher–student relationships that are characterized as lacking in support and involvement might contribute to bullying in school, as research findings suggest (for a review, see Espelage and Swearer 2003). Teachers might foster or prevent bullying incidents, depending on whether they promote positive interactions among students or if they are aware of bullying and conflictual situations with peers among students (Espelage and Swearer 2003). Studies have documented that teachers are sometimes not aware of bullying in their classrooms and schools, as evidenced by their reporting lower prevalence rates of bullying than teachers (Stockdale et al. 2002). Considering that teachers are uninvolved or unaware of bullying situations, students are less likely to turn to their teachers when confronted with bullying at school. A study by Rigby and Bagshaw (2003), which asked 7,000 middle school students about their relationships with their teachers and whether their teachers intervened in bullying incidents, found that 40% responded “not really” or “only sometimes interested” in deterring these behaviors.

Discussion

Four potentially relevant mediating factors (i.e., emotional dysregulation, depression, anger, and social skills deficits) and three moderating factors (i.e., parent–child relationship, peer relationship, and teacher relationship) were identified in this review. These mediators and moderators need to be further examined empirically, which can enhance our understanding of how physically, emotionally, and sexually abused and neglected youth are involved in bullying perpetration and victimization at school. The relationship between abuse and neglect and bullying is highly complex, but additional empirical investigations could disentangle the complexity of the pathways linking the two phenomena.

Research implications

Despite a dearth of literature available on the connection between child maltreatment and bullying involvement, there appears to be enough support for an association to forge a major research agenda. It is imperative that scholars conducting longitudinal studies on child abuse and neglect assess bullying and victimization experiences, including bullying involvement as a bully, victim, or bully–victim in community, clinically, and nationally representative samples. Only with longitudinal data and appropriately sophisticated statistical analysis can researchers begin the process of examining the complex relationship between child maltreatment, bullying, and victimization, as well as the existence of potential mediators and moderators whose discovery will enrich our scientific understanding of these relationships and our ability to develop appropriate sophisticated and targeted interventions.

Furthermore, the school-based research community must learn to negotiate with Institutional Review Boards (IRB) in order to appropriately ask about child maltreatment experiences. Indeed, children and adolescents who report current or past maltreatment must be provided with referral information after completing a research protocol and encouraged to seek help from teachers, counselors, or other trusted adults if they are in danger. Most school-based bullying researchers have not asked these questions because they have been required by their IRB to report the abuse to school administrators. Researchers must learn to think creatively about how to provide appropriate referrals to services for study participants who indicate that they have been subject to bullying. We will never completely be able to assess the link between maltreatment and bullying involvement in large-scale studies unless we address the human subjects’ realities of such research.

That said, future research could also assess constructs related to child maltreatment by studying harsh parenting, sibling aggression, or family conflict or hostility. For example, in a sample of American middle school children, significant differences were found in the prevalence of bullying of and victimization by siblings among bullies, victims, those who were both bullies and victims, and those not involved in bullying (Duncan 1999). Nearly one third of students who reported bullying their peers were also bullied by their siblings (29.03%). More than half of those who bullied their peers (56.45%) reported bullying siblings. Generally, children who witness or experience the perpetration of violence in the home may identify with the perpetrator and may learn that violent and aggressive acts are appropriate behaviors, especially when the behavior goes unpunished (Baldry and Farrington 1998; Espelage and Low, under review). Thus, future research should ask about sibling aggression and witnessing of violence within the home as a proxy of child maltreatment or neglect.

Practice implications

Child welfare

Child safety and well-being are paramount to the mission of child welfare. An awareness of the links between child maltreatment in the home and community must incorporate an extended awareness of the school setting as another context in which these relationships may play out. Practitioners must consider the school environment as a place in which victimized children and adolescents are at risk for revictimization. Case management plans must include school-related goals and objectives and community–school collaborations need to be fostered. The differentiation of subpopulations within the category of children who have been maltreated takes on considerable importance in this review of empirical studies and theories. The relationship between child welfare and the fields of counseling and social work practices in the school settings becomes critically important in the design and implementation of preventative and remedial strategies.

We should also note, however, that collaborative efforts between child welfare and school systems have been faced with heavy challenges, considering that few mechanisms exist to support successful collaborations (Altshuler 2003). Both institutions have different foci and have difficulty working collaboratively with each other, and children who are being served by either system often receive inadequate services from both systems (Altshuler 1997; Goren 1996). As suggested by Altshuler (2003), administrators in both child welfare and school settings can help facilitate collaborative efforts through commitment to joint planning and goal setting. Moreover, school social workers, in particular, are in a unique position to bridge a gap between the two systems, as they “speak the same language” as caseworkers and understand the “educational language” that permeates school systems (Altshuler 2003).

School services

Despite the growing evidence that violence in the home is a strong predictor of bullying victimization and perpetration in school (see Espelage and Low, under review; Swearer et al. 2006), none of the large-scale comprehensive school-based bullying prevention programs or frameworks specifically address exposure to family violence or child maltreatment. However, school-based bullying programs can focus on the potential mediating variables of emotional dysregulation, depression, anger, and social skills deficit. One approach that is gaining more attention in bullying prevention is the social and emotional learning (SEL) approach (Frey et al. 2005). SEL as a framework emerged from influences across different movements that focused on resiliency and teaching social and emotional competencies to children and adolescents (Elias et al. 1997). In response, advocates for SEL use social skill instruction to address behavior, discipline, safety, and academics to help youth become self-aware, manage their emotions, build social skills (empathy, perspective-taking, respect for diversity), friendship skill building, and make positive decisions (Zins et al. 2004). An SEL framework includes five interrelated skill areas: self-awareness, social awareness, self-management and organization, responsible problem solving, and relationship management. Recently, a meta-analytic study of more than 213 bullying prevention and intervention programs found that, if a school implements a quality SEL curriculum, the school can expect better student behavior and an 11-point increase in standardized test scores (Durlak et al. 2011). The gains that schools see in achievement come from a variety of factors—students feel safer and more connected to school and academics, SEL programs build work habits in addition to social skills, and kids and teachers build stronger relationships (Zins et al. 2004).

Indeed, as demonstrated by our review of the potential moderating factors, it is our contention that strong relationships among parents, peers, students, and teachers and staff in classrooms and schools can ameliorate many of the negative outcomes associated with negative home environment. While it is likely that school-based programs will improve the social–emotional skills of individual children and adolescents, some adolescents will need more targeted interventions to fully address their negative home environments.

Conclusion

In summary, to reduce and prevent the occurrence of bullying in our nation’s schools, disparate research and theoretical literatures on the various consequences of childhood maltreatment must be thoroughly analyzed and reviewed. In the absence of this effort, the development of effective interventions will be at risk. Clearly, the modeling of parental physical, emotional, and sexual abuse and neglect can have differential outcomes, depending on the child’s developmental stage, cognition and social skills, and other positive adult role models in their life space. Researchers have consistently found that negative outcomes associated with childhood physical, emotional, and sexual abuse and neglect are likely to occur in multiple contexts, such as family, school, and neighborhood (e.g., Thornberry et al. 2001). Moreover, the effects of child maltreatment are likely to occur in later years. A number of studies have suggested that maltreated children are more likely to experience other forms of violence in later years, such as dating violence during adolescence (Cyr et al. 2006; Wolfe et al. 2001, 2004) and domestic violence during adult years (Bevan and Higgins 2002; Ehrensaft et al. 2003; Ileana 2004). Identifying the potential factors that link past experiences of maltreatment to subsequent bullying is the first step, which will illuminate effective strategies for breaking the cycle of violence. This article serves as a blueprint for researchers and practitioners in the fields of school psychology, educational psychology, counseling, and social work in understanding the pathways from maltreatment to bullying perpetration and victimization in school that explain or inhibit this association, which has major implications for research and practice.

References

Akers, R. (1998). Social learning and social structure: A general theory of crime and deviance. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Altshuler, S. J. (1997). A reveille for school social workers: Children in foster care need our help! [Trends & issues]. Social Work Education, 19, 121–127.

Altshuler, S. J. (2003). From barriers to successful collaboration: Public schools and child welfare working together. Social Work, 48, 52–63.

Arsenio, W. F., & Lemerise, E. A. (2001). Varieties of childhood bullying: Values, emotion processes, and social competences. Social Development, 10, 59–73.

Aspelmeier, J. E., Elliott, A. N., & Smith, C. H. (2007). Childhood sexual abuse, attachment, and trauma symptoms in college females: The moderating role of attachment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 549–566.

Bacon, H. (2001). Attachment, trauma and child sexual abuse: An exploration. In S. Richardson & H. Bacon (Eds.), Creative responses to child sexual abuse: Challenges and dilemmas (pp. 44–59). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Baldry, A. C., & Farrington, D. P. (1998). Parenting influences on bullying and victimization. Criminal and Legal Psychology, 3, 237–254.

Baldry, A. C., & Farrington, D. P. (2005). Protective factors as moderators of risk factors in adolescence bullying. Social Psychology of Education, 8, 263–284.

Barboza, G. E., Schiamberg, L. B., Oehmke, J., Korzeniewski, S. J., Post, L. A., & Heraux, C. G. (2009). Individual characteristics and the multiple contexts of adolescent bullying: An ecological perspective. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 101–121.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bender, K. (2010). Why do some maltreated youth become juvenile offenders? A call for further investigation and adaptation of youth services. Children and Youth Services Review, 32, 466–473.

Bennett, J. A. (2000). Mediator and moderator variables in nursing research: Conceptual and statistical differences. Research in Nursing & Health, 23, 415–420.

Bennett, D. S., Sullivan, M. W., & Lewis, M. (2005). Young children’s adjustment as a function of maltreatment, shame, and anger. Child Maltreatment, 10, 311–323.

Bevan, E., & Higgins, D. J. (2002). Is domestic violence learned? The contribution of five forms of child maltreatment to men’s violence and adjustment. Journal of Family Violence, 17, 223–245.

Bolger, K. E., & Patterson, C. J. (2001). Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to peer rejection. Child Development, 72, 549–568.

Bolger, K. E., Patterson, C. J., & Kupersmidt, J. B. (1998). Peer relationships and self-esteem among children who have been maltreated. Child Development, 69, 1171–1197.

Bollmer, J. M., Milich, R., Harris, M. J., & Maras, M. A. (2005). A friend in need: The role of friendship quality as a protective factor in peer victimization and bullying. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 701–712.

Bornovalova, M. A., Gwadz, M. A., Kahler, C., Aklin, W. M., & Lejuez, C. W. (2008). Sensation seeking and risk-taking propensity as mediators in the relationship between childhood abuse and HIV-related risk behavior. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 99–109.

Bosworth, K., Espelage, D. L., & Simon, T. (1999). Factors associated with bullying behavior in middle school students. Journal of Early Adolescence, 19, 341–362.

Briere, J., & Elliott, D. M. (2003). Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 1205–1222.

Browne, A., & Finkelhor, D. (1986). Impact of child sexual abuse: A review of research. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 66–77.

Camodeca, M., & Goossens, F. A. (2005). Aggression, social cognitions, anger and sadness in bullies and victims. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 186–197.

Cassady, J., & Shaver, P. R. (Eds.). (2008). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 348–365). New York: Guilford.

Champion, K., Vernberg, E., & Shipman, K. (2003). Nonbullying victims of bullies: Aggression, social skills, and friendship characteristics. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 24, 535–551.

Chang, L., Schwartz, D., Dodge, K. A., & McBride-Chang, C. (2003). Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 598–606.

Chapple, C. L., Tyler, K. A., & Bersani, B. E. (2005). Child neglect and adolescent violence: Examining the effects of self-control and peer rejection. Violence and Victims, 20, 39–53.

Child Welfare Information Gateway (2007). Definitions in federal law. Retrieved July 14, 2011, from http://www.childwelfare.gov/can/defining/federal.cfm.

Cicchetti, D. (1989). How research on child maltreatment has informed the study of child development: Perspectives from developmental psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti & V. Carlson (Eds.), Child maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect (pp. 377–431). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cicchetti, D., Lynch, M. L., Shonk, S., & Manly, J. T. (1992). An organizational perspective on peer relations in maltreated children. In R. D. Parke & G. W. Ladd (Eds.), Family-peer relationships: Modes of linkage (pp. 345–383). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Contreras, J. M., & Kerns, K. A. (2000). Emotional regulation processes: Explaining links between parent–child attachment and peer relationships. In K. A. Kerns, J. M. Contreras, & A. M. Neal-Barnett (Eds.), Family and peers: Linking two social worlds (pp. 137–168). Westport: Praefer.

Contreras, J. M., Kerns, K. A., Weimer, B. L., Gentzler, A. L., & Tomich, P. L. (2000). Emotion regulation as a mediator of associations between mother–child attachment and peer relationships in middle childhood. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 111–124.

Cyr, M., McDuff, P., & Wright, J. (2006). Prevalence and predictors of dating violence among adolescent female victims of child sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21, 1000–1017.

Danielson, C. K., de Arellano, M. A., Kilpatrick, D. G., Saunders, B. E., & Resnick, H. S. (2005). Child maltreatment in depressed adolescents: Differences in symptomatology based on history of abuse. Child Maltreatment, 10, 37–48.

Demaray, M. K., & Malecki, C. K. (2003). Perceptions of the frequency and importance of social support by students classified as victims, bullies and bully/victims in an urban middle school. School Psychology Review, 32, 471–489.

DeRosier, M. E. (2004). Building relationships and combating bullying: Effectiveness of a school-based social skills group intervention. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 196–201.

Dill, E. J., Vernberg, E. M., Fonagy, P., Twemlow, S. W., & Gamm, B. K. (2004). Negative affect in victimized children: The roles of social withdrawal, peer rejection, and attitudes toward bullying. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 159–173.

Dishion, T., McCord, J., & Poulin, F. (1999). When intervention harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist, 54, 755–764.

Dishion, T. J., Poulin, F., & Burraston, B. (2002). Peer group dynamics associated with iatrogenic effect in group interventions with high-risk young adolescents. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 91, 79–92.

Dodge, K. A. (1991). The structure and function of reactive and proactive aggression. In D. Pepler & K. Rubin (Eds.), The development and treatment of childhood aggression (pp. 201–218). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Duncan, R. D. (1999). Maltreatment by parents and peers: The relationship between child abuse, bully victimization, and psychological distress. Child Maltreatment, 4, 45–55.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82, 405–432.

Dussich, J. P. J., & Maekoya, C. (2007). Physical child harm and bullying-related behaviors: A comparative study in Japan, South Africa, and the United States. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 51, 495–509.

Egeland, B., Carlson, E., & Sroufe, L. A. (1993). Resilience and process. Development and Psychopathology, 5, 517–528.

Ehrensaft, M. K., Cohen, P., Brown, J., Smailes, E., Chen, H., & Johnson, J. G. (2003). Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 741–753.

Elias, M. J., Zins, J. E., Weissberg, K. S., Greenberg, M. T., Haynes, M., Kessler, R., et al. (1997). Promoting social and emotional learning: Guidelines for educators. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Elliott, M. (Ed.). (1991). Bullying: A practical guide to coping for schools. Exeter: Longman.

Elliott, G. C., Cunningham, S. M., Linder, M., Colangelo, M., & Gross, M. (2005). Child physical abuse and self-perceived social isolation among adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 1663–1684.

English, D. J. (1998). The extent and consequences of child maltreatment. The Future of Children, 8, 39–53.

Espelage, D., & Horne, A. (2008). School violence and bullying prevention: From research based explanations to empirically based solutions. In S. Brown & R. Lent (Eds.), Handbook of counseling psychology (4th ed., pp. 588–606). Hoboken: Wiley.

Espelage, D. L., & Swearer, S. M. (2003). Research on school bullying and victimization: What have we learned and where do we go from here? School Psychology Review, 32, 365–383.

Espelage, D. L., Bosworth, K., & Simon, T. R. (2000). Examining the social context of bullying behaviors in early adolescence. Journal of Counseling and Development, 78, 326–333.

Espelage, D. L., Bosworth, K., & Simon, T. R. (2001). Short-term stability and prospective correlates of bullying in middle-school students: An examination of potential demographic, psychosocial, and environmental influences. Violence and Victims, 16, 411–426.

Fekkes, M., Pijpers, F. I. M., & Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P. (2004). Bullying behavior and associations with psychosomatic complaints and depression in victims. The Journal of Pediatrics, 144, 17–22.

Fekkes, M., Pijpers, F. I. M., Fredriks, A. M., Vogels, T., & Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P. (2006). Do bullied children get ill, or do ill children get bullied? A prospective cohort study on the relationship between bullying and health-related symptoms. Pediatrics, 117, 1568–1574.

Fergusson, D. M., & Horwood, L. J. (1999). Prospective childhood predictors of deviant peer affiliation in adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40, 581–592.

Fox, C., & Boulton, M. (2003). Evaluating the effectiveness of a social skills training (SST) programme for victims of bullying. Educational Research, 45, 231–247.

Fox, C. L., & Boulton, M. J. (2005). The social skills problems of victims of bullying: Self, peer and teacher perceptions. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 75, 313–328.

Frey, K. S., Nolen, S. B., Van Schoiack Edstrom, L., & Hirschstein, M. K. (2005). Effects of a school-based social-emotional competence program: Linking children's goals, attributions and behavior. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 26, 171–200.

Garbarino, J. G. (2004). Foreword. In D. L. Espelage & S. M. Swearer (Eds.), Bullying in American schools: A social-ecological perspective on prevention and intervention (pp. 6–8). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 539–579.

Gershoff, E. T., Grogan-Kaylor, A., Lansford, J. E., Chang, L., Zelli, A., Deater-Deckard, K., et al. (2010). Parent discipline practices in an international sample: Associations with child behaviors and moderation by perceived normativeness. Child Development, 81, 487–502.

Gil, A., Gama, C. S., de Jesus, D. R., Lobato, M. I., Zimmer, M., & Belmonte-de-Abreu, P. (2009). The association of child abuse and neglect with adult disability in schizophrenia and the prominent role of physical neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 618–624.

Gilbert, R., Widom, C. S., Browne, K., Fergusson, D., Webb, E., & Janson, S. (2009). Child maltreatment 1: Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet, 373, 68–81.

Glaser, D. (2000). Child abuse and neglect and the brain: A review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41, 97–116.

Goren, S. G. (1996). Child protection and the school social worker. In R. Constable, S. McDonald, & J. P. Flynn (Eds.), School social work: Practice, policy & research perspectives (pp. 355–366). Chicago: Lyceum Books.

Grassi-Oliveira, R., & Stein, L. M. (2008). Childhood maltreatment associated with PTSD and emotional distress in low-income adults: The burden of neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 1089–1094.

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26, 41–54.

Grogan-Kaylor, A., & Otis, M. D. (2003). The effect of childhood maltreatment on adult criminality: A tobit regression analysis. Child Maltreatment, 8(2), 129–137.

Han, Y., & Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2011). Parenting and youth mental health in South Korea using fixed effects model. Journal of Family Issues, in press.

Harper, F. W. K., & Arias, I. (2004). The role of shame in predicting adult anger and depressive symptoms among victims of child psychological maltreatment. Journal of Family Violence, 19, 359–367.

Herrenkohl, E. C., Herrenkohl, R. R., & Egolf, B. (1994). Resilient early school-age children from maltreating homes: Outcomes in late adolescence. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 64, 301–309.

Herrenkohl, T. I., Huang, B., Tajima, E. A., & Whitney, S. D. (2003). Examining the link between child abuse and youth violence: An analysis of mediating mechanisms. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18, 1189–1208.

Hinshaw, S. P. (2007). Moderators and mediators of treatment outcome for youth with ADHD: Understanding for whom and how interventions work. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 664–675.

Holmes, W. C. (2008). Men’s self-definition of abusive childhood sexual experiences, and potentially related risky behavioral and psychiatric outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 83–97.

Holt, M. K., & Espelage, D. L. (2007). Perceived social support among bullies, victims, and bully–victims. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 984–994.

Howe, C., & Espinosa, M. P. (1985). The consequences of child abuse for the formation of relationships with peers. Child Abuse & Neglect, 9, 397–404.

Hugh-Jones, S., & Smith, P. K. (1999). Self-reports of short- and long-term effects of bullying on children who stammer. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 69, 141–158.

Hussey, J. M., Chang, J. J., & Kotch, J. B. (2006). Child maltreatment in the United States: Prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics, 118, 933–942.

Ileana, A. (2004). The legacy of child maltreatment: Long-term health consequences for women. Journal of Women's Health, 13, 468–473.

Johnsona, R. M., Kotch, J. B., Catellier, D. J., Winsor, J. R., Duroft, V., Hunter, W., et al. (2002). Adverse behavioral and emotional outcomes from child abuse and witnessed violence. Child Maltreatment, 7, 179–186.

Kaukiainen, A., Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Tamminen, M., Vauras, M., Maki, H., et al. (2002). Learning difficulties, social intelligence, and self-concept: Connections to bully–victim problems. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 43, 269–278.

Keenan, K. (2000). Emotion dysregulation as a risk factor for child psychopathology. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 7, 418–434.

Kelly, L. (1992). The connections between disability and child abuse: A review of the research evidence. Child Abuse Review, 1, 157–167.

Kerns, K. A., Abraham, M. M., Schlegelmilch, A., & Morgan, T. A. (2007). Mother–child attachment in later middle childhood: Assessment approaches and associations with mood and emotion regulation. Attachment & Human Development, 9, 33–53.

Kim, Y. S., Leventhal, B. L., Koh, Y. J., Hubbard, A., & Boyce, W. T. (2006). School bullying and youth violence: Causes or consequences of psychopathologic behavior? Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 1035–1041.

Klomek, A. B., Marrocco, F., Kleinman, M., Schonfeld, I. S., & Gould, M. S. (2007). Bullying, depression, and suicidality in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 40–49.

Klomek, A. B., Marrocco, F., Kleinman, M., Schonfeld, I. S., & Gould, M. S. (2008). Peer victimization, depression, and suicidality in adolescents. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 38, 166–180.

Klomek, A. B., Sourander, A., Niemela, S., Kumpulainen, K., Piha, J., Tamminen, T., et al. (2009). Childhood bullying behaviors as a risk for suicide attempts and completed suicides: A population-based birth cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 254–261.

Knutson, J. F., & Schartz, H. A. (1997). Physical abuse and neglect of children. In T. A. Widiger, A. J. Frances, H. A. Pincus, R. Ross, M. B. First, & W. Davis (Eds.), DSM-IV sources, vol. 3 (pp. 713–804). Washington: American Psychiatric Association Press.

Knutson, J. F., DeGarmo, D. S., & Reid, J. B. (2004). Social disadvantage and neglectful parenting as precursors to the development of antisocial and aggressive child behavior: Testing a theoretical model. Aggressive Behavior, 30, 187–205.

Leadbeater, B. J., Kupermine, G. P., Hertzog, C., & Blatt, S. J. (1999). A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Developmental Psychology, 35, 1268–1282.

Lee, V., & Hoaken, P. N. S. (2007). Cognition, emotion, and neurobiological development: Mediating the relation between maltreatment and aggression. Child Maltreatment, 12, 281–298.

Lee, B. R., & Thompson, R. (2009). Examining externalizing behavior trajectories of youth in group homes: Is there evidence for peer contagion? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 31–44.

Leeb, R. T., Paulozzi, L., Melanson, C., Smith, T., & Arias, I. (2008). Child maltreatment surveillance: Uniform definition for public health and recommended data elements, version 1.0. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

Lev-Wiesel, R., Daphna-Tekoah, S., & Hallak, M. (2009). Childhood sexual abuse as a predictor of birth-related posttraumatic stress and postpartum posttraumatic stress. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 877–887.

Lynch, M., & Cicchetti, D. (1992). Maltreated children’s reports of relatedness to their teachers. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 57, 81–107.

Marsee, M. A., & Frick, P. J. (2007). Exploring the cognitive and emotional correlates to proactive and reactive aggression in a sample of detained girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 969–981.

Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., & Pereg, D. (2003). Attachment theory and affect regulation: The dynamics, development, and cognitive consequences of attachment-related strategies. Motivation and Emotion, 27, 77–102.

Miller, K. (2003). Understanding and treating reactive attachment disorder. A workshop presented by Medial Educational Services, Eau Claire, Wisconsin in Arlington, TX.

Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A. (2001). Childhood predictors differentiate life-course persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways among males and females. Development and Psychopathology, 13, 355–375.

Mohr, A. (2006). Family variables associated with peer victimization: Does family violence enhance the probability of being victimized by peers? Swiss Journal of Psychology, 65, 107–116.

Mouttapa, M., Valente, T., Gallaher, P., Rohrbach, L. A., & Unger, J. B. (2004). Social network predictors of bullying and victimization. Adolescence, 39, 315–335.

Ohene, S.-A., Ireland, M., McNeely, C., & Borowsky, I. W. (2006). Parental expectations, physical punishment, and violence among adolescents who score positive on a psychosocial screening test in primary care. Pediatrics, 117, 441–447.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bully/victim problems among school-children: Long-term consequences and an effective intervention program. In S. Hodgins (Ed.), Mental disorder and crime (pp. 317–349). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Poulin, F., Dishion, T. J., & Burraston, B. (2001). 3-year iatrogenic effects associated with aggregating high-risk adolescents in cognitive-behavioral preventive interventions. Applied Developmental Science, 5, 214–224.

Rigby, K. (2003). Consequences of bullying in schools. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 48, 583–590.

Rigby, K. (2005). Why do some children bully at school? School Psychology International, 26, 147–161.

Rigby, R., & Bagshaw, D. (2003). Prospects of adolescent students collaborating with teachers in addressing issues of bullying and conflict in schools. Educational Psychologist, 23, 535–546.

Robers, S., Zhang, J., Truman, J., & Snyder, T. D. (2010). Indicators of school crime and safety: 2010 (NCES 2011-002/NCJ 230812). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, US Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, US Department of Justice.

Rodkin, P. C., & Hodges, E. V. E. (2003). Bullies and victims in the peer ecology: Four questions for psychologists and school professionals. School Psychology Review, 32, 384–400.

Roland, E., & Idsoe, T. (2001). Aggression and bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 27, 446–462.

Roode, Tv, Dickson, N., Herbison, P., & Paul, C. (2009). Child sexual abuse and persistence of risky sexual behaviors and negative sexual outcomes over adulthood: Findings from a birth cohort. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 161–172.

Runyon, M. K., & Kenny, M. C. (2002). Relationship of attributional style, depression, and posttrauma distress among children who suffered physical or sexual abuse. Child Maltreatment, 7, 254–264.

Ryan, J. P., Marshall, J. M., Herz, D., & Hernandez, P. M. (2008). Juvenile delinquency in child welfare: Investigating group home effects. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 1088–1099.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1993). Crime in the making. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Schmidt, M. E., & Bagwell, C. L. (2007). The protective role of friendships in overtly and relationally victimized boys and girls. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 53, 439–460.

Schneider, B. H., Attilli, G., Nadel, J., & Weissberg, R. P. (1989). Social competence in developmental perspective. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Schwartz, D., & Proctor, L. (2000). Community violence exposure and children’s social adjustment in the school peer group: The mediating roles of emotion regulation and social cognition. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 670–683.

Schwartz, D., Dodge, K. A., & Cowie, J. D. (1993). The emergence of chronic peer victimization in boy’s play groups. Child Development, 64, 1755–1772.

Schwartz, D., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (1997). The early socialization of aggressive victims of bullying. Child Development, 68, 665–675.

Schwartz, D., Proctor, L. J., & Chien, D. H. (2001). The aggressive victim of bullying: Emotional and behavioral dysregulation as a pathway to victimization by peers. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized (pp. 147–174). New York: Guilford.

Shields, A., & Cicchetti, D. (1998). Reactive aggression among maltreated children: The contributions of attention and emotion dysregulation. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 27, 381–395.

Shields, A., & Cicchetti, D. (2001). Parental maltreatment and emotion dysregulation as risk factors for bullying and victimization in middle childhood. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30, 349–363.

Shields, A., Ryan, R. M., & Cicchetti, D. (2001). Narrative representations of caregivers and emotion dysregulation as predictors of maltreated children’s rejection by peers. Developmental Psychology, 37, 321–337.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445.

Sourander, A., Klomek, A. B., Niemela, S., Haavisto, A., Gyllenberg, D., Helenius, H., et al. (2009). Childhood predictors of completed and severe suicide attempts: Findings from the Finnish 1981 Birth Cohort Study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 398–406.

Springer, K. W., Sheridan, J., Kuo, D., & Carnes, M. (2007). Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: Results from a large population-based sample of men and women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 517–530.

Stewart, A., Livingston, M., & Dennison, S. (2008). Transitions and turning points: Examining the links between child maltreatment and juvenile offending. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 51–66.

Stockdale, M. S., Hangaduambo, S., Duys, D., Larson, K., & Sarvela, P. D. (2002). Rural elementary students’, parents’, and teachers’ perceptions of bullying. American Journal of Health Behavior, 26, 266–277.

Stocker, C. M., & Youngblade, L. (1999). Marital conflict and parental hostility: Links with children’s sibling and peer relationships. Journal of Family Psychology, 13, 598–609.

Stuewig, J., & McCloskey, L. A. (2005). The relation of child maltreatment to shame and guilt among adolescents: Psychological routes to depression and delinquency. Child Maltreatment, 10, 324–336.

Stuwig, J. (2005). The relation of child maltreatment to shame and guilt among adolescents: Psychological routes to depression and delinquency. Child Maltreatment, 10, 324–336.

Swearer, S. M., Peugh, J., Espelage, D. L., Siebecker, A. B., Kingsbury, W. L., & Bevins, K. S. (2006). A socioecological model for bullying prevention and intervention in early adolescence: An exploratory examination. In S. R. Jimerson & M. J. Furlong (Eds.), Handbook of school violence and school safety: From research to practice (pp. 257–273). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Tajima, E. A. (2004). Correlates of the co-occurrence of wife abuse and child abuse among a representative sample. Journal of Family Violence, 19, 399–410.

Thornberry, T. P., Ireland, T. O., & Smith, C. A. (2001). The importance of timing: The varying impact of childhood and adolescent maltreatment on multiple problem outcomes. Development and Psychopathology, 13, 957–979.

Toblin, R. L., Schwartz, D., Gorman, A. H., & Abou-ezzeddine, T. (2005). Social-cognitive and behavioral attributes of aggressive victims of bullying. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 26, 329–346.

Toth, S. L., Manly, J. T., & Cicchetti, D. (1992). Child maltreatment and vulnerability to depression. Development and Psychopathology, 4, 97–112.

Trickett, P. K., & Kuczynski, L. (1986). Children’s misbehaviors and parental discipline strategies in abusive and nonabusive families. Developmental Psychology, 22, 115–123.

Turner, H. A., Finkelhor, D., & Ormrod, R. (2006). The effect of lifetime victimization on the mental health of children and adolescents. Social Science & Medicine, 62, 13–27.

Tyler, K. A., Hoyt, D. R., Whitbeck, L. B., & Cauce, A. M. (2003). The impact of childhood sexual abuse on later sexual victimization among runaway youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11, 151–176.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth and Families. (2009). Child maltreatment 2007. Washington: US Government Printing Office.

Weiss, B., Caron, A., Ball, S., Tapp, J., Johnson, M., & Weisz, J. R. (2005). Iatrogenic effects of group treatment for antisocial youths. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 1036–1044.

Widom, C. (1989). The cycle of violence. Science, 244, 160–166.

Wolfe, D. A., Scott, K., Wekerle, C., & Pittman, A. L. (2001). Child maltreatment: Risk of adjustment problems and dating violence in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 282–289.

Wolfe, D. A., Wekerle, C., Scott, K., Straatman, A. L., & Grasley, C. (2004). Predicting abuse in adolescent dating relationships over 1 year: The role of child maltreatment and trauma. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 406–415.

Zimmermann, P., Maier, M. A., Winter, M., & Grossmann, K. E. (2001). Attachment and adolescents’ emotion regulation during a joint problem-solving task with a friend. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25, 331–343.

Zingraff, M. T., Leiter, J., Myers, K. A., & Johnsen, M. C. (1993). Child maltreatment and youthful problem behavior. Criminology, 31, 173–202.

Zins, J. E., Weissberg, R. P., Wang, M. C., & Walberg, H. J. (Eds.). (2004). Building school success through social and emotional learning. New York: Teachers College Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, J.S., Espelage, D.L., Grogan-Kaylor, A. et al. Identifying Potential Mediators and Moderators of the Association Between Child Maltreatment and Bullying Perpetration and Victimization in School. Educ Psychol Rev 24, 167–186 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9185-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9185-4