Abstract

Despite much progress in improving the quality of preschool programs, there is still an uneven quality of instruction in early childhood settings. Providing support and professional development (PD) for teachers that is practical, systematic and sustainable is one potential avenue to increase classroom quality in preschool, including quality of literacy instruction. Preschool educators who want to focus on increasing the quality of literacy instruction need simple-to-use tools that can be implemented quickly and provide a means to assess progress towards the goal of improving literacy instruction. The Quality of Literacy Implementation checklist measures how well the teaching staff include intentional, instruction in literacy/oral language. Rather than focusing on a specific curriculum or intervention, quality of implementation focuses on the teacher’s delivery of key procedural features of evidence-based instruction. As is the case with fidelity of implementation, a quality of implementation checklist not only measures implementation but also provides a roadmap about how instruction might be modified to ensure that critical and essential skills are emphasized across the preschool day.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Rationale for the Use of a Quality of Implementation Checklist

Across the field of Literacy instruction, there is overwhelming evidence and consensus that becoming a skilled reader is a process that begins early. Preschool has become a critical time for teachers to build literacy skills, yet some evidence suggests that the actual amount and quality of literacy instruction in some preschool classrooms may be less than optimal (Early et al. 2005; Greenwood et al. 2013). Teachers have many competing demands on their day, such as developing social-emotional skills, physical skills, concepts, and even health and hygiene. High rates of turnover, low pay and low status compound the difficulty of delivering quality early literacy programs (Beauchat et al. 2009). Early childhood teaching practices, including literacy practices, should be embedded and distributed throughout the day (Dinnebeil and McInerney 2011), which can be a challenge for early childhood teachers who typically have children with a wide range of language and literacy skills (Shanahan and Lonigan 2008).

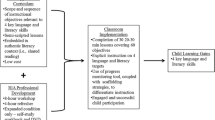

Providing support and professional development (PD) for teachers that is practical, systematic and sustainable is one potential avenue to increase classroom quality. In their review of best practices in early childhood, Sheridan et al. (2011) reported that the combination of didactic training workshops and teacher coaching led teachers from knowledge acquisition to classroom implementation. Professional development that is focused on strategies which increase the quality of teacher-child interactions can positively affect children’s acquisition of language and literacy (Dickinson and Caswell 2007). Teachers need the opportunity to apply and refine these practices through feedback in the classroom. Where instructional coaches are not available, peer coaching or mentoring may also be effective (Hanft et al. 2004). While coaching-based feedback is an empirically supported approach to increasing the quality of instruction, there are few observational tools specifically designed to be used for this purpose (Crawford et al. 2013). Preschool directors or school administrators wanting to focus on instructional practices known to increase the quality of literacy instruction need simple-to-use tools that can be implemented quickly and provide a means to assess progress towards the goal of improving literacy instruction.

Many educators have heard about the use of a fidelity of implementation checklist with a rubric format that measures how well instructional staff implement a particular intervention. However, some educators may not have heard about quality of instructional implementation checklists. A quality checklist measures how intentional and participatory the teaching staff’s instruction is in a given area such as literacy/oral language. Rather than focusing on a specific curriculum or intervention, quality of instructional implementation focuses on the teacher’s delivery of key procedural features of engaging, evidence-based instruction in a particular content area. Like fidelity of implementation, a quality of implementation checklist measures implementation but also provides a roadmap about how instruction might be modified to ensure that students are given plenty of opportunity to practice critical and essential skills throughout the day. Global classroom quality has been linked to children’s development of language and literacy skills (Howes et al. 2008; Justice et al. 2008). More specifically, for students who are considered at-risk, quality of the literacy learning environment in particular must be strong in order to meet their needs (Cunningham 2010).

Development of the Quality of Literacy Implementation Checklist

The Quality of Literacy Implementation Checklist (Quality; Abbott et al. 2012) was created and refined across research projects from three federal Department of Education grants that targeted children at risk for future academic failure (Abbott et al. 2011; Greenwood et al. 2012; Sheridan et al. 2011). The goal in all of these projects was to accelerate children’s early literacy learning by improving teacher instruction. To create the tool, the components of best practices and predictive early literacy skills that are needed to become ready to learn to read in kindergarten were identified. The identification was done through extensive searches of educational research literature that indicated what was needed for effective and developmentally appropriate implementation of literacy curriculum in preschool. For example, the work of Hart and Risley (2003) identifies the need for strong language skills. Greenwood et al. (2002) research focused on in increasing children’s opportunities to respond and identified the need for teachers to provide modeling and encourage guided and independent practice. Additionally, recommendations from national organizations concerned with literacy practices for young children were considered, such as the joint position statement from the International Reading Association (IRA) and the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) which emphasized providing intentional and enriching language and literacy experiences in the classroom (IRA and NAEYC 1999). Next, these components of best practices were translated into teacher behaviors that are both observable and quantifiable, and these behaviors are explicated in the Quality of Literacy Instruction Checklist, which starts with an observation of the instructional core of the day. During the observation, the observer also takes notes that provide a qualitative component to the tool. This information, along with the rubric rating, is used for PD planning and mentoring.

The Quality has been validated in terms of connecting teacher behaviors to improved child outcomes. In previous studies utilizing the Quality, which were conducted at both public preschool and Head Start programs in suburban and urban settings, there was a moderately significant relationship between the score on the Quality and children’s end of the year pre-literacy achievement scores as measured by the composite score on the PELI (Kaminski et al. 2012), [r (38) = .36, p < .05] (Greenwood and Beecher 2014). The tool is easy to use because it is specific about what teacher behaviors are measured and has demonstrated reliability.

In addition, across two federally-funded research projects (Greenwood et al. 2012; Sheridan et al. 2011) called Literacy Data-Driven Decisions (Literacy 3D, L3D) reliability ranged from 93 to 100 % agreement among 5 different observers. Traditionally, agreement should be at least 75 % or better so that users can feel confident about information gathered from the instrument (Stemler 2004), however 85 % was set as the lowest acceptable level of agreement in previous studies using the Quality.

Components of Early Literacy Measured by the Quality

Early literacy includes the development of skills that are precursors of reading, including phonological awareness, letter and sound knowledge, and oral language (Lonigan et al. 2000). Phonological awareness is the ability to perceive and control the sounds of a language. This awareness develops into phonics skills that enable a child to associate each sound of language with its corresponding alphabetic letter. Phonological awareness and early print knowledge are the strongest predictors of reading success. Future vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension skills are built on oral vocabulary knowledge and aural comprehension (Shanahan and Lonigan 2008).

Components of Effective Instruction Measured by the Quality

Early literacy research demonstrates that teachers can develop early reading skills in young children by providing enriching language and literacy environments and including purposeful instruction in letters and sounds (Howes et al. 2008). All children, including children with disabilities or considered at-risk, need intentional development of their early literacy skills. An essential component of effective instruction is that teachers employ behaviors that increase children’s opportunity to respond to prompts, thereby providing more practice, feedback and deeper learning. Effective early childhood teachers are also adept at scaffolding instruction and differentiating instruction (Ankrum et al. 2014). Differentiated instruction means providing specific targeted scaffolded instruction that is different from one child to another based on a child’s specific level of performance. Instruction can be provided that scaffolded but not necessarily differentiated. Likewise, instruction can be differentiated that does not necessarily include the components of scaffolded instruction. For example, a teacher may differentiate instruction by asking one child to clap the syllables in her name, while asking another child to clap the syllables of a new vocabulary word. The teacher may scaffold this task by doing a model and practice routine with each child. Both scaffolding and the model and practice routine are included on the Quality checklist.

In addition to teachers teaching the essential early literacy skills that are part of curriculum guidelines, an outside observer who can objectively look at instruction is a key element with the Quality checklist. A literacy coach, administrator, master teacher, or other professional observes during literacy instruction, makes notes about teacher implementation of literacy and oral language activities, and fills out the checklist. For programs that lack resources or staff, teachers may use the “buddy system”, observe each other and discuss the results. Although the Quality was developed with live observation, programs could use video recording in cases where there is not a staff member free to do the observation.

The coach/administrator/master teacher uses the checklist to guide teachers towards evidence-based practices known to support literacy and also to measure a teacher’s progress in improving literacy instruction, which is particularly useful to determine if PD is effective. For example, a preschool director could use the Quality at the beginning of the school year to determine where staff may need PD, create a plan to implement training, and then re-evaluate with periodic observations. As with other types of progress monitoring, the Quality checklist indicates if quality of literacy instruction has improved, or if teachers need more intensive support, such as coaching or peer mentoring. These activities should be carried out in a supportive, safe environment where teachers can feel free to learn from experience and develop a critical reflective personal growth stance (Onchwari and Keengwe 2010).

Implementation Steps

Below are the steps a program can use to gather quality of literacy implementation classroom data.

-

Step 1. Identify the person or persons who will observe in the classroom and fill out the Quality of Implementation Checklist. This could be a program administrator, a principal, a mentor or master teacher, or a coach already employed in supporting teachers.

-

Step 2. The observer gets to know the Quality.

Table 1 Literacy 3D Quality of Literacy Implementation Checklist presents the Quality (Table 1). There are three sections, Teacher Behavior—pertaining to what the teacher does to support literacy and language instruction, Other Adults Behavior—pertaining to what special services teachers, teacher’s assistants, aides, or volunteers do to support literacy and language instruction, and Student behavior—pertaining to students’ responses to the adults’ instruction. Each item was selected based on the evidence of its importance to support learning, especially in terms of enhancing the Literacy Learning Environment (LLE) in the preschool classroom. The first part of the checklist pertains to literacy skills specifically, while the second part of the checklist applies to teaching strategies. Items 9–12 address scaffolding and differentiation. Scaffolded instruction has three components. The first is teacher modeling the skill or skill content, (I Do It). Secondly is guided practice, where children are given a sufficient number of opportunities to practice that skill with teacher support (We Do It). The final component is that the student demonstrate the skill has been learned through independent practice (You Do It). In addition, item 12 of the Quality addresses differentiated instruction. Because children in classrooms are at many different levels of academic performance, teachers must modify instruction in order to meet the needs of all children. The Quality recommends that scaffolded instruction is a companion to differentiated instruction.

The Quality user’s guide gives the evidence-based explanation for the item, a definition of the scoring criteria (Scoring: 0 = Does not do, 1 = Does on limited basis, 2 = Fully implements, N/A), and examples plus non-examples of the type of behavior the item is meant to address. For instance, teacher item number 4, shown in Table 2. Quality Guide Example gives an example of the detail provided for each item.

Each item is scored, then each section is totaled and converted to a percentage score for ease of interpretation.

Each section (teacher, other staff, children) may be considered separately, or an overall score can be calculated by combining the section scores. The percentage scores give an easy way to see improvement over time. For example, in the L3D intervention study, the overall average beginning-of-the-year Quality score for the participating teachers was 66 %. After participating in the intervention (including coaching), the overall average end-of-the-year Quality score was 86 %, a statistically significant increase. The comparison group, which did not receive the intervention, did not show change in Quality scores (average of 62 % for both occasions). The percentages are not empirically derived, but intended to judge the relative strength of a classroom team’s instruction and provide a means to initiating and monitoring concrete improvement in the team’s implementation.

-

Step 3. Establish reliability. Once an observer has become familiar with the Quality, the observer should calibrate his or her scoring of the checklist to any other observers in the program to ensure that differences in scores are due to observed characteristics of teachers, not to differences in raters. For the purposes of program development (not evaluation), calibration reliability can be calculated by the total percentage of scores on which the two observers agree. During calibration, two observers conduct the observation together. Scores are then compared, and discrepancies discussed. If reliability is >75 %, further training or recalibration may be necessary. It is a good practice for knowledgeable observers to re-calibrate if more than 6 months pass without conducting Quality observations.

-

Step 4. Review the Quality checklist with the teaching staff so all teachers are familiar with the content and purpose. A Quality observation is not meant to be a punitive evaluation of teacher performance and should not be an intimidating process for teachers. The checklist is introduced and thoroughly reviewed with the teaching staff. The purpose of the Quality is for school staff to get input from another experienced educator who can, with a neutral eye, examine current instructional patterns, determine areas of strength and opportunities to include more evidence-based practices that increase the amount and/or quality of literacy instruction.

-

Step 5. The observer conducts the Quality. The observation is scheduled with the teacher during a typical day and time when the observer is most likely to see literacy instruction. It is best to observe large group, storybook reading, center/free time, and small group instructional times. However, observers may also choose the largest block of uninterrupted instructional time available. Days with special events or a disrupted schedule should be avoided, as the observation should capture the instructional core of the classroom. The observer creates narrative notes for future reference when scoring the Quality for all instructional staff present in the classroom. Notes should include examples of specific behaviors of all teaching staff and students that provide evidence for the rating, not descriptors. For example, in order to demonstrate evidence that the teacher has a plan to develop alphabet knowledge (T-5), an observer might note “Teacher asks each child to say the first letter of their name as they transition from circle to centers. Children get up and complete transition in less than 2 min”, rather than “Teacher does a nice letter recognition transition activity”. The ease with which the children do this task indicates that it is a familiar activity; therefore, it must be a part of the teacher’s regular patterns of instruction.

-

Step 6. The observer scores the Quality. Each section is tallied and given a score, and then the section scores are added up for an overall score. A percentage for the Teacher section is calculated by dividing the tallied score by the total possible. The same procedure is used for the Other Adults section. In the Student section, scores are given by estimating the percentage of children who demonstrated the behavior. To maintain reliability, it is good practice to conduct reliability checks with all observers during each observation period to ensure all observers are applying the checklist in the same manner. If there was another observer establishing reliability, the scores should be compared and reliability calculated by looking at the overall percentage score given by each observer and divided the lesser by the greater. The observation is considered to be reliable with a reliability score of 85 % or more. No two observation narratives will be identical, and some variation is expected in scoring based on differences in what each observer records. However, the overall percentage scores should be fairly similar and reflect the overall amount of literacy focus occurring in the classroom. If reliability is less than 85 % for program evaluation purposes, further training or recalibration is recommended.

-

Step 7. The observer provides feedback. The observer may or may not choose to discuss the actual score. In our coaching feedback we did not discuss the score, because it was not as relevant as the content of the observation. Performance-based feedback combined with PD has been demonstrated to be an effective way of improving teacher instructional quality (McCollum et al. 2013). Therefore, the checklist can also point towards specific PD needs. Any items that score below a 2 are potential topics for continuing PD or coaching. During feedback, the observer begins by asking the teacher what went well, and what he or she thinks is an area of improvement. Using the detailed observation notes, the observer reinforces or adds to the areas of strength noted by the teacher, works collaboratively to identify 1–2 areas to strengthen, and plans concrete steps to ensure that the teacher has the resources necessary to make the agreed upon changes to instruction. Any PD that is needed is provided immediately or scheduled to take place. Often times, if the observer also serves in a coaching or mentoring capacity, a simple strategy to address the need can be chosen by the teacher with coach guidance and practiced with the coach during the same feedback session. We call this mini-PD. At this time, the teacher and observer should also schedule an Instructional Modification Observation (IMO). IMOs are short and limited to the specific intervention or strategy that is being implemented to address the area of need. IMOs are repeated until the teaching team exhibits good implementation of the intervention or strategy. Then later in the year, the Quality can be used again to monitor progress towards the goals set by the teacher and observer.

Summary and Discussion

In our studies, the quality of the LLE was related to increases in children’s literacy skills. This finding is similar to Cunningham (2010), who found an r = .35 relationship between a rating of the literacy environment and children’s literacy skills as rated by the teacher. Therefore, assessing the quality of the literacy environment in preschool classrooms and providing support to the teacher based on the observation could be a viable method of increasing children’s growth in appropriate literacy skills. This is particularly important for children who are considered at-risk because of poverty. Research has consistently demonstrated that a high quality literacy environment is necessary in order to close or prevent potential academic achievement gaps (Cunningham 2010; Howes et al. 2008; Justice et al. 2008).

While there are many mandates and recommended practices for literacy in preschool classrooms today, as Crawford et al. (2013) noted, there are not many practical tools that early childhood professionals can use. The same is true for focusing on the quality of literacy instruction in a manner that is developmentally appropriate for preschoolers. In addition, many programs lack resources such as literacy coaches or substitutes that allow teachers to attend PD. The Quality can be used by any experienced early childhood professional to provide mini-PD support that is packaged within positive, non-judgmental feedback. Instructional issues that are systemic throughout the preschool teaching staff can be identified and specifically targeted during school-wide PD. The Quality also assists in evaluating PD in terms of how that PD was translated into improved classroom instruction. The Quality provides an easy-to-use rubric format that can be used to support preschool teachers’ PD, a stronger LLE, and ultimately children’s literacy development.

References

Abbott, M., Atwater, J., Lee, Y., & Edwards, L. (2011). A data-driven preschool PD model for literacy and oral language instruction. NHSA Dialog: A Research-to-Practice Journal for the Early Childhood Field, 14(4), 229–245.

Abbott, M., Peterson, S., Payette, C., & Beecher, C. C. (2012). The quality of literacy implementation checklist. Kansas City, KS: University of Kansas.

Ankrum, J. W., Genest, M. T., & Belcastro, E. G. (2014). The power of verbal scaffolding:“Showing” beginning readers how to use reading strategies. Early Childhood Education Journal, 42(1), 39–47.

Beauchat, K. A., Blamey, K. L., & Walpole, S. (2009). Building preschool children’s language and literacy one storybook at a time. The Reading Teacher, 63(1), 26–39.

Crawford, A. D., Zucker, T. A., Williams, J. M., Bhavsar, V., & Landry, S. H. (2013). Initial validation of the prekindergarten Classroom Observation Tool and goal setting system for data-based coaching. School Psychology Quarterly, 28(4), 277.

Cunningham, D. D. (2010). Relating preschool quality to children’s literacy development. Early Childhood Education Journal, 37(6), 501–507.

Dickinson, D. K., & Caswell, L. (2007). Building support for language and early literacy in preschool classrooms through in-service professional development: Effects of the Literacy Environment Enrichment Program (LEEP). Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(2), 243–260.

Dinnebeil, L. A., & McInerney, W. F. (2011). A guide to itinerant early childhood special education services. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Company.

Early, D., Barbarin, O., Bryan, B., Burchinal, M., Chang, F., & Clifford, R. et. al. (2005). Pre-kindergarten in eleven states: NCEDL’s multi-state study of pre-kindergarten and state-wide early educational programs (SWEEP) study. http://fcd-us.org/sites/default/files/Prekindergartenin11States.pdf.

Greenwood, C. R., Abbott, M., Atwater, J., Beecher, C. C., & Petersen, S. (2012). Pre-K EBASS efficacy study OSEP funded. Kansas City, KS: University of Kansas.

Greenwood, C. R., & Beecher, C. C. (2014, February). Where is the literacy instruction? Developing a coaching intervention to increase teacher-student literacy interactions in preschool. Poster presented at the conference on research in early intervention (CRIEI), San Diego, CA.

Greenwood, C. R., Carta, J. J., Atwater, J., Goldstein, H., Kaminski, R., & McConnell, S. R. (2013). Is a response to intervention (RTI) approach to preschool language and early literacy instruction needed? Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 33(1), 48–64.

Greenwood, C. R., Horton, B. T., & Utley, C. A. (2002). Academic engagement: Current perspectives on research and practice. School Psychology Review, 31(3), 328.

Hanft, B. E., Rush, D. D., & Shelden, M. L. L. (2004). Coaching families and colleagues in early childhood. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Company.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (2003). The early catastrophe: The 30 million word gap by age 3. American Educator, 27(1), 4–9.

Howes, C., Burchinal, M., Pianta, R., Bryant, D., Early, D., Clifford, R., et al. (2008). Ready to learn? Children’s pre-academic achievement in pre-kindergarten programs. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(1), 27–50.

International Reading Association and National Association for the Education of Young Children. (1999). Learning to read and write: Developmentally appropriate practices for young children. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Justice, L. M., Mashburn, A. J., Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2008). Quality of language and literacy instruction in preschool classrooms serving at-risk pupils. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(1), 51–68.

Kaminski, R. A., Abbott, M., Bravo-Aguayo, K., & Good, R. H. (2012). Preschool early literacy indicators. Eugene, OR: Dynamic Measurement Group.

Lonigan, C. J., Burgess, S. R., & Anthony, J. L. (2000). Development of emergent literacy and early reading skills in preschool children: evidence from a latent-variable longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 36(5), 596.

McCollum, J. A., Hemmeter, M. L., & Hsieh, W. Y. (2013). Coaching teachers for emergent literacy instruction using performance-based feedback. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 33(1), 28–37. doi:10.1177/0271121411431003.

Onchwari, G., & Keengwe, J. (2010). Teacher mentoring and early literacy learning: A case study of a mentor-coach initiative. Early Childhood Education Journal, 37(4), 311–317.

Shanahan, T., & Lonigan, C. J. (2008). Developing early literacy: A report of the national early literacy panel. http://www.nifl.gov/publications/pdf/NELPReport09.pdf.

Sheridan, S. M., Carta, J., Knoche, L. L., Abbott, M., & Clarke, B. (2011). IES Pre3T annual performance report. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska.

Stemler, S. E. (2004). A comparison of consensus, consistency, and measurement approaches to estimating interrater reliability. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 9(4). Retrieved from 2 Sep 2015. http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=9&n=4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beecher, C.C., Abbott, M.I., Petersen, S. et al. Using the Quality of Literacy Implementation Checklist to Improve Preschool Literacy Instruction. Early Childhood Educ J 45, 595–602 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-016-0816-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-016-0816-8