Abstract

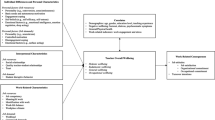

Surprisingly little is known about Head Start teachers; who teaches, why they teach, and how they think and feel about their work. To begin to address these issues, a survey was developed and distributed to Head Start teachers, assistant teachers, and aides in one three-county program to examine their motivation and well-being. Follow-up interviews were then conducted to gain deeper insights into the teachers’ lives, values, beliefs, plans, and concerns. Results suggest that Head Start teachers are motivated by a deep service ethic. Additionally, nearly all of the teachers reported high levels of satisfaction, efficacy and confidence with no differences based on age, level of education, or position. However, many reported dissatisfaction with their compensation. Analyses were also conducted from the perspective of life course theory and research. Results suggest recent policy changes emphasizing greater levels of education for teachers appear to have serious unanticipated consequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dramatic changes followed passage of the Improving Head Start for School Readiness Act of 2007 (Public Law 110–134). Following reauthorization, like public schools after passage of No Child Left Behind (NCLB), Head Start has found itself facing growing accountability pressures and a press toward standardization (Brown 2010). For the first time, grants were funded for a definite period, 5 years, and “only grantees delivering high-quality services [would be] given another five-year grant non-competitively” (Report 2008, p. 1). By law, determination of program quality would be based on data reliably gathered, program reviews, and annual audits. Changes were also made in eligibility requirements, monitoring and corrective action, including provision for unannounced program inspections, and, for Head Start teachers, credentialing requirements were raised. By 2013, 50 % of center-based teachers must have a bachelor’s degree (Tipton 2008).

Concerned about how Head Start teachers are faring under the new requirements, we conducted a rather far-reaching literature review. To our surprise, we found no studies of Head Start teacher well-being, although there are a few studies related to early childhood educator job satisfaction and stress (Jorde-Bloom 1988; Kelly and Berthelsen 1995; Sumsion 2002). Moreover, the conclusion offered by McGinty et al. (2008) appears accurate: “Little attention has been focused on the creation of workplace environments that are more rewarding and satisfying to preschool teachers, despite evidence that the preschool teaching environment provides unique and specific challenges” (p. 362). Accordingly, we undertook this exploratory study to illuminate some aspects of the “unique and specific challenges” of teaching in Head Start and in relation to their wider life challenges. We wanted to know more about the teachers, themselves, their goals, aspirations, commitment to teaching and sources of satisfaction and concern. It is to these questions that this study is addressed.

The Study

Meadowland (Meadow View) Head Start was incorporated in 1978 and since that time has served the children and families of three counties in the state of Utah. At the time of the study, the monthly enrollment at Meadow View was 817 children, serving 43 % of eligible children. Total program income was just over $6 million, all but $.5 million coming from a Federal Head Start grant. Meadow View operates ten centers with approximately 54 classes (48 are double session) and includes both rural and urban sites. Approximately 240 children are bused. Medical and dental exams are given to enrolled children and a wide range of family support services is provided, as is the case in Head Start Programs across the U.S.

Each Head Start classroom instructional team is composed of a Head Teacher (HT), an Assistant Teacher (AT), and most teams also have a Classroom Aide (Aide). There are additional bus aides. An effort is made to have one Spanish speaker on each team. The HT is responsible for the team and for completing assessments and paperwork required by Federal mandate to demonstrate grant compliance. HTs report to one of four Child Development Specialists, adding an additional level to the Head Start organization, one residing between the director and her assistants and the classroom teachers. At the time of this study, Meadow View Head Start employed 28 HTs, 28 ATs, 18 Aides and 15 Bus Aides.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, preschool pay varies dramatically across regions. Head Start teachers average about $30,000, or $14.42 an hour, well below average school teachers’ pay but generally better than pay in day care or many private preschools. Rates vary by position, level of education, and years of experience, but the range is narrow. Finally, aides averaged less than $10.00 an hour, and many were part time.

Survey Instrument

Following IRB approval, a survey instrument was developed and piloted that sought a range of information about Head Start teachers, including HTs, ATs, and aides. Arrangements were made to distribute the survey during the year-end full faculty meeting. In addition to a number of demographic questions and a detailed employment history, the survey included questions about reasons for becoming a Head Start teacher, description and assessment of present teaching roles and responsibilities, efficacy measures and measures of job satisfaction, levels of confidence and commitment, including future aspirations, and sources of concern and worry. Efficacy measures were drawn from the student engagement and classroom management subscales of the Teachers’ Sense of Teacher Efficacy Scale (Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy 2001) and job satisfaction measures from the Early Educators Survey (Sidelinger 2008), which was based on the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (Demerouti et al. 2001). The year-end faculty meeting was attended by all 89 of the Head Start teachers, representing all three work categories, noted above. Participants were paid $25 for completing and returning the survey. Forty-eight surveys were eventually returned: 16 from HTs (57 %); 18 from ATs (64 %); and 14 from aides (42 %).

Survey Results

Survey data were analyzed first through a series of ANOVAs to determine if levels of work satisfaction, efficacy or confidence differed based on position (HT, AT, and Aide), age (20–29; 30–38; 39–48; 50+), or level of education (BA/BS vs. no BA/BS). All respondents reported relatively high levels of job satisfaction (max score = 4; mean = 2.91; SD = 0.45 median = 2.93; range = 1.85), efficacy (max score = 9; mean = 6.61 SD = 1.11; median = 6.50; range = 4.50) and confidence (max score = 4; mean = 3.40; SD = 0.45 median = 3.45; range = 2.27). No significant statistical differences were found.

While it is not surprising the teachers and aides reported high levels of satisfaction, it is interesting to note some of the reasons why this may be the case and how it relates to the one area of shared dissatisfaction: low pay. Across the board, informants reported they liked their work with children, valued the goals of Head Start, with few exceptions enjoyed working with their teams, and felt able to do their work well. Sixty percent (n = 29) reported a significant event in their lives had prompted them to work with young children. Many spoke of experiences that led them to care about children in need. One teacher, for example, reported, “My family did foster care and I saw the lives they were living and I decided then that I wanted to help people, especially children. I want to help make their lives better in any way that I can.” (24 yr old, married, AT). Many also said they have always wanted to teach. “Not a single event, just a lifetime of being in this world.” (40 year-old, married AT). Each of these factors certainly plays a part in teacher and aide satisfaction that is separate from other contextual factors, such as pay.

As such, it may not be surprising that although the participants reported being satisfied with their work, many also expressed concern about their financial situations. Participants were asked if they had considered leaving Head Start and, if they had, the reasons why. They also were asked three different questions about their greatest worries, greatest disappointments, and the drawbacks of working at Head Start. When asked if they had considered leaving 28 of the 48 respondents (58 %) indicated that they had and 10 of those 28 potential leavers (36 %) reported that they would leave or had considered leaving primarily over concern about their pay. The second most frequently reported reason for leaving was also related to money as 8 of the 28 teachers (29 %) reported they would leave to pursue more education. Other reasons for leaving included age or health, to do something else, dissatisfaction with past leadership, family concerns, stress, underutilized skills, and children’s difficult behavior. Nineteen of the 48 respondents (40 %) also included financial issues as among of their greatest worries, disappointments or drawbacks related to working at Head Start.

Interview Protocol

Following analysis of the surveys, an interview protocol was developed for the purpose of gaining deeper insight into the teachers’ lives, values, beliefs, plans and concerns. All 48 of the teachers who completed the survey were invited to participate in an interview for which they would be paid $50. Twenty-five agreed to be interviewed: 14 HTs, 7 ATs, and only 4 aides. Head teachers apparently felt more confident about being interviewed than did their colleagues. A graduate student with an extensive background in early childhood education and who was coached on effective interviewing practices conducted the interviews. Additionally, the program Director and two of her assistants were interviewed to fill in background information about Meadow View. All interviews were transcribed for analysis. Following repeated readings of the transcripts, an informant by variable matrix (Miles and Huberman 1984, p. 110) was created that included in addition to marital status, position, and age of the informants (taken from the surveys), the following: Total years working in Head Start (not only years in current position), whether or not the informant rose through the ranks of Head Start, father’s job when growing up, plans to stay in Head Start, vision of Head Start, worries and concerns for self and for the children taught, driving motivation for teaching, and why and how they became involved in Head Start.

Interview Results

When added to or compared with the open-ended survey item responses, the following findings emerged: (A) Virtually all of the interviewees displayed a strong service ethic, often connected to strongly-held religious beliefs and commitments. They spoke of loving teaching, enjoying working with the children and families, and of doing an important work even as many worried about their own finances, personal health, or the children’s discouraging home situations. This last finding echoes numerous studies of teacher motivation over many years (Richardson and Watt 2006; Serow et al. 1994) and in preschool teaching (Court et al. 2009). A HT offered a typical comment, “The children [are the best thing about my current position]. Being able to make a difference in their lives, and feel the difference they make in [my life]. I also love working with the parents.” (B) With but two exceptions, the HTs reported consistently very high self-efficacy within their current job assignment. Five of the aides and three ATs volunteered that their talents were not being fully or well utilized; they could do more, they thought and would welcome a change. “I’m overqualified for my current job. [I would like to] work in a location where my educational experience is desired and accepted” (29 year-old HT with a BA). (C) A surprising number, fully half, of the informants had experience prior to working for Head Start in home day care or in one or another private preschool. (D) Twenty of the 25 informants who were interviewed either had or intended, if they stayed teaching in Head Start, on moving up through the job ranks. Figures provided by the Director indicated that 18 of 28 HTs had been promoted within the ranks; 9 of 28 ATs; and 10 of the 33 aides had shifted positions. Movement up or down within Head Start is relatively easy and encouraged. (E) Virtually all the informants expressed deep concern for the children and their futures, especially about difficulties related to living in poverty and to problems within families. A 40 year-old aide captures the general sense of those interviewed: “One of the main reasons I teach there, I mean I could open my own preschool again out of my home, but one of the main reasons I teach there is because those kids need me.” Another teacher (26 year-old, AT) remarked, “I worry that [the children] might not have those things they need. That they might not have the food they need. They’ll tell [me]…’my tummy hurts.” The respondents also expressed personal concerns. Half reported having serious financial worries, most especially those who were divorced and were the sole supporters of themselves and their families. A 58 year-old, divorced, classroom aide commented, for example, that she was able to make ends meet by doing without: “I don’t have too many bills. I don’t have internet, I don’t have cable…I don’t have a car.” Concerned about her colleagues, a married, 54 year-old HT, remarked, “If I had to live on my income, there is no way I could make it… I would be on welfare.” A few respondents also expressed concerns about the pay in connection with the increasing demands for higher levels of education. One 53 year-old, divorced, AT with a bachelor’s degree expressed her discouragement with the amount of pay and increasing demand for better qualifications in this way, “I have a real problem with the government saying that for Head Start teachers they can only hire college graduates…but pay them this [low] wage, this outrageous wage.” (F) Older (over age 50), but very few young, head teachers and aides planned to continue working in Head Start. Older and the least well-educated ATs also intended to stay. Young respondents (under age 30) with BS/BA degrees reported to be the least likely to stay in Head Start. Eight of the 14 aides surveyed who (in one or more of the three questions about leaving, worries, disappointments or drawbacks associated with their work) reported they would leave Head Start, said low pay is their primary dissatisfaction. An additional two aides said they hoped to leave their current Head Start positions and move up within Head Start in order to increase their pay. (G) Following the appointment of a new director who emphasized knowledge of the 2007 Federal Readiness Act, there was a consistent and clear understanding among informants of the purposes of Head Start. Aims included, in addition to academic and social readiness, child health and well-being and family support. (H) No patterns were found related to teacher social class background as determined by father’s employment. (I) Nearly all those interviewed began working in Head Start because they needed work. “Actually, when I graduated I wasn’t interested in teaching…I actually got to Head Start by applying as a secretary and then they called me back and said that’s been filled but we see on your resume you are qualified to teach” (29 year-old HT). The teachers frequently commented that Head Start paid better than day care. Others stated that their preference was to teach in an elementary school but there were no jobs available. “I think, in this community, Head Start is the overflow of elementary ed teachers who can’t get into the public school system…because of budget cuts and because of competition” (62 year-old HT).

Reviewing the entire data set, differences in age, education levels, marital status, and family responsibilities (in particular having children and the age of the children) were connected to work patterns, to positions held within Head Start, personal worries and concerns, ambitions and future plans. As noted, virtually all participants, regardless of age or education, held a strong service ethic and expressed a deep love for the children with whom they worked. They liked what they did. As we reviewed the data and considered the emerging patterns, it became apparent that they represented somewhat distinct differences in life course. We thought that these differences very likely would have important implications for both policy and practice within Head Start, a point suggested by Ackerman (2005). Accordingly, we conducted yet another analysis of the data, this from the perspective of life course theory (Mortimer and Shanahan 2004).

Life Course Concepts

As a theoretical orientation, life course research is concerned with “social pathways in historical time and place for human development and aging”(Elder et al. 2004, p. 4). The life course grows out of recognition that patterns of living differ based on a range of considerations both personal and social-historical.

Social pathways are the trajectories of education and work, family and residences that are followed by individuals and groups through society. These pathways are shaped by historical forces and are often structured by social institutions. Individuals generally work out their own life course and trajectories in relation to institutionalized pathways and normative patterns. They are subject to change, both from the impact of the broader contexts in which they are embedded and from the impact of the aggregation of lives that follow these pathways. Large-scale social forces can alter these pathways through planned interventions…and unplanned changes… Individuals choose the paths they follow; yet choices are always constrained by the opportunities structured by social institutions and culture. (ibid, p. 8)

Among the useful life course concepts are trajectories, transitions, turning points, cohort and period effects. Each concept will find a place in the discussion that follows. Trajectories are made up of transitions. A trajectory is a sequence of roles and experiences; while a transition is a change in status or identity. A turning point signals a shift in trajectory, a change in the direction of life. Location in a cohort places the individual in an age group and in an historical time. Differences in age signal differences in experience and life conditions while sharing an age brings with it similarities in experience and condition. The result is a cohort effect. A period effect results “when the impact of social change is relatively uniform across successive birth cohorts” (ibid, p. 9).

Social Pathways

The analysis that follows involved developing a pathway for each teacher and aide from the surveys and interview data. The two youngest women in the sample, ages 20 and 21, are not included. These two young women were in school and living with their parents. Primarily, emphasis will be placed on the dominant patterns that emerged. Natural age breaks produced four groupings: Ages 23–29, 14 total; Ages 30–35, 6 total; Ages 39–48, 12 total; and 50 and older, 14 total. (The pathways for each group are available by request.)

Ages 23–29 pathways. (14 total, 6 HTs, 5 ATs, 3 Aides) Ten of the 14 participants held either a BS or a BA degree. Two of the ATs had an associate’s degree and two of the aides had only completed high school. Seven of the 14 were married, one divorced.

A conclusion from a study of young, church-going women, ages 18–25, helpfully frames the discussion that follows in this and the next section (age 30–35 pathways). Colaner and Giles (2008) write:

As women are in the idealistic planning phase, they may not be focusing on the practicality of their desires but rather on the ideal based on their particular [religious] role ideology. By emphasizing the ideal, these women may not be realizing the possible tensions in store when they must reconcile the education they received with the limited options available when a child enters the family. (p. 531)

As noted, 10 of 14 women falling in this group hold BS/BA degrees, including one of three aides and two of four ATs. The other two ATs plan to complete baccalaureate degrees. Two aides, the only mothers in the group, one married, the other divorced, have no plans to obtain additional education and, although concerned with finances, likely will stay in Head Start. Neither aide gave any indication of wanting to move up. Two of the teachers were pregnant, both holders of baccalaureate degrees, one a HT and the other an AT. With the birth of her child, the HT will quit Head Start while the AT plans to work part time. In total, 12 of the 14 women have considered leaving Head Start, and at least six are actively making plans to leave. Generally, married teachers who do not yet have children do not plan on staying.

Marriage, pregnancy, and giving birth altered these young women’s pathways, signaling for most a turning point, a change in life’s trajectory. Mostly, these changes appear to be of the “strategic” rather than the “reactive” type, being “generally preferential, goal-oriented and planned out by those who make them” (Tomlinson 2006, p. 373). On the whole, once married, it appears the teachers adjust their career plans to their husband’s schooling and career trajectory, a view consistent with the findings of Colaner and Giles (2008) about church-going young women.

The two aides who are mothers both have confronted the challenge noted by Colaner and Giles (ibid), of reconciling “the education they received with the limited options available when a child enters the family” (p. 531) and Head Start figures prominently in their future plans. One of the aides reported the following as the significant event that made her decide to become a teacher of young children, “When I got divorced, my daughter took it really hard. I enrolled her in Head Start. I fell in love with the program.” The aides recognized their futures as limited by their modest educational attainments and constrained by their family obligations. However, given the severe economic downturn beginning in 2007, all 14 women undoubtedly have experienced and will continue to experience a cohort effect; when compared to economically more robust times, there are fewer opportunities for employment.

Ages 30–35 pathways. (6 total, 1 Aide, 3 ATs, and 2 HTs) Two of the 6 participants held either a BS or a BA degree. One HT, one AT and the one aide in this cohort had an associate’s degree and one of the ATs had a Child Development Associate (CDA). Three of the six were married, two divorced.

That the number of teachers who fall within this group is so small suggests that many of the women who began working in Head Start in their twenties did not stay. This conclusion finds support in that virtually all of the teachers within this age group came to Head Start after working in a variety of jobs, some for extended periods of time, including day care and, for one, a brief stint in Head Start. In addition, of the two participants with any longevity in Head Start (10 and 8 years), neither have children. One of these teachers has an associate’s degree while the other graduated from high school and received a Child Development Associate credential. Four of the six teachers have children, three were stay-at-home-moms for a time, and two are divorced. For both the divorced and for the married AT, who has worked for Head Start for 10 years, financial worries are pressing, as they are for the one aide. It would appear that Kerpelman and Schvaneveldt (1999) are likely correct when they argue: “As the roles of men and women continue to evolve, many young adults will find that developing and maintaining a traditional pattern of role involvements is neither feasible nor desirable” (p. 192).

Viewing these findings through the lens of life course research, it is likely that none of the women are following the social pathway envisioned in their early twenties, again underscoring the conclusion of Colaner and Giles (2008) noted above. Divorces with associated financial pressures, not marrying or not giving birth, influenced the life trajectories taken. All six women must work outside of the home, and the relative accessibility of Head Start employment coupled with better pay than in day care or most preschools (see Hale-Jinks et al. 2006; McGinty et al. 2008) fits their needs. This view is supported by the conclusions of Howes et al. (2003), when they note: “the informal rule is that people are often hired to fill entry-level positions and are then expected to get [needed training] in order to hold on to these positions or to move towards positions with more responsibility and compensation” (p. 107). The high numbers of participants who have moved up in Meadow View indicates that this “informal rule” obtains.

Using the descriptive categories developed by Tomlinson (2006), the patterns evident in this subcategory appear less “strategic” than “reactive” or “compromised.” “Reactive transitions take place as women react or respond to unplanned changes… They specifically relate to transitions that would not have occurred unless some other factor in the work-life balance equation hadn’t changed” (p. 374). Compromised choice transitions involve both “choice and constraint,” and trade-offs of various kinds. For the most part, the work of Head Start compared to other types of work is more balance friendly and therefore attractive (Kilgallon et al. 2008).

Ages 39–48 pathways. (12 total, 4 Aides, 4 ATs, and 4 HTs) Five of the 12 women in this category held either a BS or a BA degree. One HT and one AT had an associate’s degree. One AT also had a CDA. One AT and three aides had only completed high school.

Of the 12 participants one is divorced, two single, and nine are married (three aides, all four ATs, one without children, and two of the four HTs). Nine of the 12 teachers have children. Like the teachers in the 30–35 category, these women came to Head Start late, mostly after raising their children, and took advantage of the relative ease of employment. The dominant pattern of this group of teachers is captured by what Tomlinson (2006) described as a “child-before-career” trajectory: “The women associated with the child-before-career pattern were older women, who had had their children first, at a young age, and then, later, once children were midteens, embarked on a work career” (p. 377). This trajectory primarily involves the compromised choice transition noted above. Seven of the 12 participants were, for a time, stay-at-home-moms. To accommodate their child rearing responsibilities but to contribute to the financial well-being of the family, the majority of the women in this category with children, and one without, organized a home day care or worked in a preschool.

The two single (but not divorced) women, both HTs, came to Head Start after working full-time in other settings. One was a secondary education teacher who found the work painfully stressing and who found in Head Start a meaningful and enjoyable career and worked her way up to HT. At the time of data gathering, this teacher was in her 11th year in Head Start and was enrolled in graduate school. She wrote: despite financial concerns, she “[keeps] coming back because [she] love[s] working with the children.” The second single (but not divorced) teacher worked for a number of years in retail until the company for which she worked fell into bankruptcy. She reported that she “always wanted to teach…there’s 11 kids in my family…lots of teachers.” “She sought, but was not offered, jobs teaching kindergarten.” Even after beginning work at Head Start she occasionally applied for other teaching positions. After 13 years teaching in Head Start she reports that she “loves the program” and will stay.

All of the aides and all but one unmarried HT in this category reported being satisfied with their levels of pay. That the aides were satisfied with their pay may indicate lower expectations related to their comparatively lower level of educational attainment (excluding the one aide who is considering seeking elementary school employment). In contrast, all the ATs expressed concern about low salaries and expressed a desire to move up the teaching hierarchy. This finding is of particular importance when compared to a conclusion reached by Wagner and French (2010) about ATs’ willingness to participate in professional development activities: “What was unexpected…was the finding that pay and opportunities for promotion was a significant predictor of intrinsic motivation for teaching assistants [but not for head] teachers” (p. 168).

Ages 50–67 pathways. (14 total, 4 aides, 6 ATs, and 4 HTs). Of these teachers, one is widowed, eight are or have been divorced, all are mothers.

As with the Head Start teachers in the 39–48 pathway group, the women in this category again fall into the “child-before-career” trajectory (Tomlinson 2006). All 14 married, eight divorced. Virtually all of the participants entered the workforce relatively late, and primarily because they needed work. As a group, these teachers and aides have the lowest level of educational attainment; only four of 14 have baccalaureate degrees, a not surprising finding given changes in Head Start priorities but also changing patterns of education within the wider population over time and a reduction in the number of school teaching jobs. Nine of the 14 women reported having been stay-at-home-moms, and four either worked in a preschool or organized home day care when their children were young.

None of the participants in this category except one anticipating retirement at year’s end reported expecting to leave Head Start, including those few who mentioned being dissatisfied with the pay. As one of the HTs wrote: “My age makes it difficult to change jobs.” Only three, an aide and two ATs, wrote of wanting to move up in Head Start, and this was for financial reasons, although one of the ATs reported she very much likes not being wholly responsible for a classroom and would prefer staying put. The other teachers expect to remain in their current positions; eight reported not even thinking about leaving Head Start. On the whole, these women seem settled. “I know it is not good money but it is satisfying.” All report enjoying the children even as a few note deterioration in their energies or their abilities to relate to young children and their parents. “I love being a part of Head Start. My only [concern] is just my declining years approaching…and keeping up with the challenges.” Two said they had chosen to move down, from HT to AT and Aide, primarily for health reasons. These two women await retirement. Clearly, an attractive feature of employment in Head Start is that teachers can move up as well as down the employment hierarchy.

Conclusion

Anticipating the implications of the 2007 School Readiness Act, Ackerman (2005) warned, “Seemingly straightforward policy initiatives…are not necessarily self-actualizing in terms of achieving their premises or goals” (n.p.). She notes several potential challenges, both “personal” and “institutional” to meeting the “new BA policy.” Among the personal challenges mentioned are, “The constraints of being an adult learner,” “Academic insecurity,” “Language barriers,” and “Inability to pay for coursework.” The institutional challenges include issues of capacity and articulation. Our data suggest that Ackerman’s concerns remain. However, by focusing on Head Start teachers and aides, the data presented in this study raise another set of issues, more cultural and more deeply personal.

Head Start is driven by a dominating concern for the well-being of poor children and their families. Historically, a good many Head Start teachers and aides have also been Head Start parents, coming to know and care about the program by being served by it and by working within it as a volunteer, a requirement for participation. Moreover, the data indicate at least half of the participants came to Head Start after having worked in home day care or preschool and after having been, for a time, stay-at-home moms. These women came to Head Start knowing a lot about what they were getting into and often seeking family friendly work. They wanted to teach young children and the ease of employment in Head Start opened this opportunity. Once employed in Head Start, the aides and ATs often moved up as they gained experience and increased education. On this view, high turnover is manageable, and, from a budgetary perspective, programmatically beneficial, serving to keep costs of services relatively low. The pool of potential employees appears deep and well-experienced even as it seems to be highly fluid.

The emphasis in the 2007 law is school readiness. As noted, increasing the level of Head Start teacher educational qualifications is a central strategy, part of professionalizing Head Start. Possession of degrees rather than experience with children-day care, preschool, mothering—has been elevated in importance with the result, as the data show, that increasingly HTs, in particular, are much younger and more highly educated than their predecessors. One result is that instructional teams are often composed of very young HTs, frequently working in their first full-time jobs, with much more seasoned and experienced ATs and even aides. Most of these older women are mothers and find themselves needing to work to support their families or, for never married women, support themselves. In contrast, and on the whole, the younger teachers do not expect to stay working in Head Start long term although, like their older colleagues, at some point they may find themselves returning and for similar reasons. At this point in their lives, their aspirations point elsewhere, a different life trajectory. Recruitment patterns are shifting.

Head Start directly competes with elementary schools for teachers and, by comparison, Head Start is not financially attractive. For many of the young women, nearly all of whom reported themselves as being religious, their primary ambition is to have children and spend at least a portion of their lives as stay-at-home mothers. Lack of financial incentives coupled with life course ambitions that will take them away from full-time employment, help explain why there are so few teachers in their 30s in the sample. In effect, it appears that young women with BA/BSs tend not to stay, or at least do not think they will stay, and when they leave Head Start they are replaced by other, equally young and inexperienced, teachers. No doubt, stability within Head Start is increased by internal promotion; yet confronting what is likely to continue to be an insistent emphasis on raising educational standards the future would appear to promise greater instability. As Ackerman (2005) observes, “Although staff with a BA degree and P-3 certification may be an essential part of a high-quality ECE setting, so is a stable, low-turnover workforce” (p. 9). The aims seem to conflict.

Aides represent a different pattern. Program-wide, a large majority of Meadow View aides have virtually no educational credentials beyond high school graduation while those who have such credential do not stay on as aides; rather, they move up or leave. Becoming an aide represents for many a helpful but relatively short-term job that for some holds out the promise of upward mobility within the program. While there are a few incentives offered to support educational advancement, the low wages paid to aides noted above, consistently less that $10 an hour, makes doing so difficult. Aides with credentials appear to move upward easily.

Stability within Meadow View Head Start appears primarily to be a function of the 15 head and 11 ATs who have six or more years of work experience within the program. As noted, while the oldest head and assistant teachers are the least well-educated, they are the most likely to stay at Head Start. Given their life situations, they need the work but they are not any less committed to the program and its aims than their younger colleagues. In addition, across the board they are very confident in their teaching abilities and, like their younger colleagues, possess high levels of self-efficacy. Here we should note a kind of role reversal has taken place in some teams. In the interviews, young and inexperienced HTs commented on how helpful the more experienced ATs and sometimes even aides were as they needed guidance when learning their roles and responsibilities and in leading teams. A few ATs and aides found this situation frustrating, including those who reported that their talents were not being well-utilized within their team.

It is a time of transition in Meadow View Head Start. A new director is working diligently to strengthen the program and to support the teachers. A range of proposals have been made to increase teacher pay, a factor crucial to long-term improvement and to achieving greater stability. Terminating the aides has been suggested by some HTs as one possibility to increase pay. Like everything else to do with Head Start, implementing this suggestion would involve a set of complicated trade-offs. Most importantly such a change would remove what in effect is a loose apprenticeship that, if coupled with increased support for greater levels of education, might have the highly desired effect of producing a continuous flow of skilled and continuously improving teachers who are deeply embedded within the local community. As Hale-Jinks et al. (2006) argue, community embeddedness is a highly desirable, key element in maintaining program quality and for retaining effective early childhood teachers. Yet, making this apprenticeship system more effective likely will require significantly increased levels of pay coupled with expanded support for continuing education. It also will place a heavy burden on Head Start leadership to be more involved in teacher assessment and development.

In conclusion, recent policies such as the 2007 School Readiness Act do not, as suggested by Ackerman (2005), “provide the kinds of support that can help ECE teachers as they get from ‘here to there’” (n.p.) nor do they appear to pay much attention to who the teachers are who work in Head Start, their motivations for teaching or their aspirations as teachers. Effective policies must carefully consider such issues if successful programs of support are to be developed, programs that enable movement up the ranks of Head Start and encourage staff stability and teacher quality.

References

Ackerman, D. J. (2005). Getting teachers from here to there: Examining issues related to an early are and education teacher policy. Early Childhood Research and Practice, 7(1). Retrieved from http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v7n1/ackerman.html.

Brown, C. P. (2010). Balancing the readiness equation in early childhood education reform. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 8(2), 133–160. doi:10.1177/1476718X09345504.

Colaner, C. W., & Giles, S. M. (2008). The baby blanket or the briefcase: The impact of Evangelical gender role ideologies on career and mothering aspirations of female Evangelical college students. Sex Roles, 58, 526–534. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9352-8.

Court, D., Merav, L., & Ornan, E. (2009). Preschool teachers’ narratives: A window on history, values and beliefs. International Journal of Early Years Education, 17(3), 207–217. doi:10.1080/09669760903424499.

Demerouti, E., Mostert, K., & Bakker, A. B. (2001). Burnout and work engagement: A thorough investigation of the independency of both constructs. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(3), 209–222.

Elder, G. H., Jr, Johnson, M. K., & Crosnoe, R. (2004). The emergence and development of life course theory. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of life the life course (pp. 3–18). New York: Springer.

Hale-Jinks, C., Knopf, H., & Kemple, K. (2006). Tackling teacher turnover in child care: Understanding causes and consequences, identifying solutions. Childhood Education, 82(4), 219–226.

Howes, C., James, J., & Ritchie, S. (2003). Pathways to effective teaching. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 18, 104–120. doi:10.1016/S0885-2006(03)00008-5.

Jorde-Bloom, P. (1988). Factors influencing overall job satisfaction and organizational commitment in early childhood work environments. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 3(2), 107–122. doi:10.1080/02568548809594933.

Kelly, A. L., & Berthelsen, D. C. (1995). Preschool teachers’ experiences of stress. Teaching & Teacher Education, 11(4), 345–357. doi:10.1016/0742-051X(94)00038-8.

Kerpelman, J. L., & Schvaneveldt, P. L. (1999). Young adults’ anticipated identity importance of career, marital, and parental roles: Comparisons of men and women with different role balance orientations. Sex Roles, 41(3/4), 189–217. doi:10.1023/A:1018802228288.

Kilgallon, P., Maloney, C., & Lock, G. (2008). Early childhood teachers’ sustainment in the classroom. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 33(2), 41–54.

McGinty, A. S., Justice, L., & Rimm-Kaufman, S. E. (2008). Sense of school community for preschool teachers serving at-risk children. Early Education and Development, 19(2), 361–384.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1984). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mortimer, J. T., & Shanahan, M. J. (Eds.). (2004). Handbook of the life course. New York: Springer.

Report of the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Re-designation of Head Start Grantees. (2008). A system of designation renewal of Head Start Grantees. Washington, DC.

Richardson, P. W., & Watt, H. M. G. (2006). Who chooses teaching and why? Profiling characteristics and motivations across three Australian universities. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 34(1), 27–56. doi:10.1080/13598660500480290.

Serow, R. C., Eaker, D. J., & Forrest, K. D. (1994). I want to see some kind of growth out of them: What the service ethic means to teacher-education students. American Educational Research Journal, 31(1), 27–48. doi:10.2307/1163265.

Sidelinger, T. (2008). The problem of burnout among early educators and how it may lead to staff turnover. Master’s thesis, University of Maine.

Sumsion, J. (2002). Becoming, being and unbecoming an early childhood educator: A phenomenological case study of teacher attrition. Teaching & Teacher Education, 18(7), 869–885. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00048-3.

Tipton, R. B. (2008). Head Start update 2008: Overview of head start reauthorization. Retrieved from http://www.caplaw.org/headstart/HeadStart2007Reauthorization.html.

Tomlinson, J. (2006). Women’s work-life balance trajectories in the UK: Reformulating choice and constraint in transitions through part-time work across the life-course. British Journal of Guidance & Counseling, 34(3), 365–382. doi:10.1080/03069880600769555.

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 783–805. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1.

Wagner, B. D., & French, L. (2010). Motivation, work satisfaction, and teacher change among early childhood teachers. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 24, 152–171. doi:10.1080/02568541003635268.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bullough, R.V., Hall-Kenyon, K.M. & MacKay, K.L. Head Start Teacher Well-Being: Implications for Policy and Practice. Early Childhood Educ J 40, 323–331 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-012-0535-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-012-0535-8