Abstract

Background

In patients with unresectable hilar malignant biliary obstruction (MBO), bilateral metal stent placement is recommended. However, treatment selection between partially stent-in-stent (SIS) and side-by-side (SBS) methods is still controversial.

Study

Clinical outcomes of bilateral metal stent placement by SBS and SIS methods for hilar MBO were retrospectively studied in four Japanese centers. While large-cell-type uncovered metal stents were placed above the papilla in SIS, braided-type uncovered metal stents were placed across the papilla in SBS.

Results

A total of 64 patients with hilar MBO (40 SIS and 24 SBS) were included in the analysis. Technical success rate was 100% in SIS and 96% in SBS. Functional success rate was 93% in SIS and 96% in SBS. Early adverse event rates were higher in SBS (46%) than in SIS (23%), though not statistically significant (P = 0.09). Post-procedure pancreatitis was exclusively observed in SBS group (29%). Recurrent biliary obstruction rates were 48% and 43%, and the median time to recurrent biliary obstruction was 169 and 205 days in SIS and SBS, respectively.

Conclusions

Other than a trend to higher adverse event rates including post-procedure pancreatitis in SBS, clinical outcomes of SIS and SBS methods were comparable in patients with unresectable hilar MBO.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Endoscopic management with uncovered metallic stents (UMSs) has been widely used for unresectable hilar malignant biliary obstruction (MBO) [1,2,3,4,5] and is now recommended in the guidelines [6]. Biliary drainage of > 33–50% liver volume was reported to be associated with better drainage effects or survival in hilar MBO [7, 8], and bilateral stent placement is often necessary to achieve this goal [9,10,11,12,13]. Additionally, a recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated better stent patency of bilateral UMS placement for high-grade hilar MBO [14]. Despite these potential clinical benefits, bilateral UMS placement is sometimes technically challenging, and there are two methods for bilateral stenting: partially stent-in-stent (SIS) [15,16,17] and side-by-side (SBS) methods [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. We previously reported safety and efficacy of SIS using a large-cell UMS [15, 16], but sequential SBS deployment across the papilla was recently reported to be a technically feasible and potentially simpler technique for hilar MBO [23,24,25,26]. It is still controversial whether SIS or SBS is superior to one another in hilar MBO. Therefore, we retrospectively compared SBS across the papilla and SIS methods for bilateral UMS placement for unresectable hilar MBO.

Patients and Methods

Patients

This is a multicenter retrospective comparative study in the University of Tokyo Hospital and three affiliated hospitals. Data on patients who underwent bilateral UMS placement for unresectable hilar MBO between July 2010 and December 2016 were retrospectively studied. The diagnosis of unresectable hilar MBO was based on either pathological diagnosis or typical imaging findings. Resectability was determined based on multidetector contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) as well as cholangiogram in conjunction with transpapillary tissue sampling [27]. Exclusion criteria included severe liver atrophy and severe comorbid conditions. This study was approved by the local ethical committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

SIS and SBS Stent Placement Procedures

Prior to endoscopic biliary drainage procedure, CT and/or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was performed, and biliary drainage area was planned based on the liver volume. In cases with concomitant cholangitis, endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) was placed as an initial drainage. After improvement in cholangitis, UMS placement was attempted at the second session. The procedures were performed under moderate sedation, and prophylactic intravenous antibiotics were administered before the procedure.

First, two or three guidewires were placed into the bile ducts to be drained, using a hydrophilic guidewire in difficult cases. Endoscopic sphincterotomy was performed prior to stent placement exclusively in SBS group. In SIS group, sphincterotomy was not performed routinely to preserve the sphincter function and to prevent ascending cholangitis due to duodenobiliary reflux. Pre-dilation of the biliary stricture was performed using a balloon or bougie dilation catheter when the stent delivery system was unable to pass the stricture.

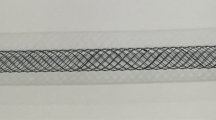

For SIS placement, Niti-S large-cell D-type biliary stents (LCD; Taewoong Corp., Gimpo, Korea) were placed above the papilla as previously reported [16]. The stent delivery system of a LCD stent is 8.5 Fr, and all LCD stents used in this study were 10 mm in diameter.

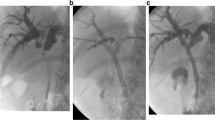

For SBS placement, uncovered WallFlex Biliary RX (ucWF) stents (Boston Scientific Corp., Marlborough, MA, USA) were placed across the papilla as described below. The stent delivery system is 8 Fr, and all ucWF stents used in this study were 8 mm in diameter. Similar to SIS placement, a first ucWF was placed in a more angulated duct, followed by a second stent placement. The hepatic end of ucWFs was placed at least 1 cm above the stricture, and the distal end was placed 1–1.5 cm in the duodenum (Fig. 1). All procedures were performed by experts on the ERCP procedure (> 5 years of ERCP experience) or by trainees (< 5 years of ERCP experience) under the supervision of experts.

a Bilateral side-by-side stent placement. A Cholangiography revealed hilar biliary stricture. B Two guidewires were placed into the right and left intrahepatic ducts. C The first stent was deployed across the papilla. D The second delivery system was advanced into the right hepatic duct. E. The second stent was deployed across the papilla in a side-by-side fashion. b Partial stent-in-stent placement. A Cholangiography revealed hilar biliary stricture. B Two guidewires were placed into the right and left intrahepatic ducts. C The first stent was placed into the left hepatic duct above the papilla. D A guidewire was placed into the right intrahepatic duct through the mesh of the first stent using the previously placed guidewire as a landmark. E The second stent was deployed above the papilla in a stent-in-stent fashion

Re-interventions

At the time of cholangitis, CT scan was performed to evaluate stent patency as well as to localize the area of cholangitis prior to re-interventions. Stent patency was evaluated on cholangiogram, and ENBD placement was attempted in all previously drained areas whenever possible through UMSs. After the resolution of cholangitis, the cause of cholangitis was evaluated in the second session. While balloon sweep was performed in cases with stent occlusion due to biliary sludge, plastic stents were placed as a stent-in-stent fashion in cases with tumor ingrowth (Fig. 2).

Outcomes

Data on technical success, functional success, procedure time, adverse events (AEs), recurrent biliary obstruction (RBO) and re-interventions for RBO, the number and types of interventions, and survival were extracted from medical records and compared between SIS and SBS groups. Technical success, functional success, RBO, and AEs were defined according to the TOKYO criteria [28]. Technical success was defined as successful stent deployment of UMSs in the intended location with sufficient coverage of the stricture. Functional success was defined as a 50% decrease in or normalization of the bilirubin level within 14 days of stent placement. Early or late AEs were defined as any stent or procedure-related AEs within or after 30 days of UMSs’ placement. RBO was defined as a composite endpoint of either stent occlusion or migration, and time to RBO (TRBO) refers to the time from UMSs’ placement to the RBO. TRBO was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared between groups using the log-rank test. Deaths without RBO were treated as censored at the time of death. Stent occlusion was defined as the recurrence of jaundice and cholestasis and/or evidence of biliary dilation on imaging studies such as ultrasonography or CT scan, requiring biliary re-intervention.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the medians and ranges, and categorical variables as the numbers and percentages. Statistical comparisons were performed with chi-square test or the Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Student’s t test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. A p value < 0.05 in two-sided test was considered as statistically significant. R software, version 2.14.0 (R Development Core Team: http://www.r-project.org), was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Between July 2010 and December 2016, 64 patients who underwent endoscopic bilateral metal stent placement for unresectable hilar MBO were enrolled: 40 SIS placement between July 2010 and December 2012, of which 26 patients were included in our previous report [16], and 24 SBS placement between June 2014 and December 2016. The patient characteristics of the two groups are shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in sex, age, the location of the primary tumor, and Bismuth classification between two groups.

Stent Placement Procedure

Details of stent placement procedures are shown in Table 2. The rate of direct UMS placement at the first session was 8% and 15% in SBS and SIS groups, respectively (P = 0.69). The median procedure time was 52 (range, 11–120) minutes in SBS group and 59 (range, 26–210) minutes in SIS group (P = 0.20), respectively. Overall technical success rate was 96% in SBS group and 100% in SIS group, respectively. In one case of SBS group, delivery insertion of a third UMS through the hilar biliary obstruction was technically impossible. Three metallic stents were placed in three patients (13%) in SBS group and four patients (10%) in SIS group (P = 0.99).

Clinical Outcomes

Clinical outcomes of SBS and SIS groups are shown in Table 3. Functional success was achieved in 96% in SBS group and 93% in SIS group (P = 0.99). Early AE rates were higher in SBS group (46%) than in SIS group (23%), though not statistically significant. Post-procedure pancreatitis was exclusively observed in seven patients (29%) in SBS group, and its severity was moderate in six cases and mild in one case. Acute cholecystitis was observed in two patients (8%) in SBS group and three patients (8%) in SIS group. Tumor invasion to cystic duct was confirmed by intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS) [29] before stent deployment in one case out of two in SBS group and all three cases in SIS group. The rates of AE by trainees were 56% (10/18) and 26% (4/15) in SBS and SIS groups, respectively. Meanwhile, those by experts were 17% (1/6) and 20% (5/25) in SBS and SIS groups. Late AE rates were 12% in SBS group and 10% in SIS group.

RBO rates were comparable between two groups: 43% in SBS group and 48% in SIS group. The major cause of RBO was tumor ingrowth (33%) in SBS group and sludge (25%) and tumor ingrowth (20%) in SIS group. Cumulative TRBO and survival are shown in Fig. 3. The median TRBO was 205 days in SBS group and 169 days in SIS group (P = 0.67). Meanwhile, the median overall survival was 381 days in SBS group and 238 days in SIS group (P = 0.07).

Re-interventions

We did not find any significant differences in the number of ERCPs during the follow-up period (2 vs. 2, P = 0.95), rates of conversion to percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) (4% vs. 8%, P = 1.00), and endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) (4% vs. 0%, P = 0.38), and TRBO after the first re-intervention (91 vs. 109 days, P = 0.32) between SBS and SIS groups. The procedure time of the first re-intervention was relatively shorter in SBS group than SIS group (35 vs. 44 min, P = 0.41), though statistically not significant. Uncontrolled cholangitis at death was present in 6% (1/17) in SBS group and 9% (3/34) in SIS group (P = 0.99).

Discussion

In cases with unresectable hilar MBO, endoscopic bilateral metal stent placement provides longer stent patency, but selection of SIS and SBS methods is still controversial. We previously reported SIS method using a large-cell-type UMS [16], but there still remain technical hurdles such as passing the guidewire and stent delivery through the first stent mesh. In this retrospective study, we compared the SBS method, which is presumably technically less demanding, with the SIS method.

Our study demonstrated that both SIS and SBS stent placement for unresectable hilar MBO demonstrated high technical and functional success rates with similar initial procedure time. Thus, we believe both SIS and SBS methods for unresectable hilar MBO are technically feasible as long as dedicated UMSs are used by experienced endoscopists.

In terms of long-term outcomes, though TRBO tended to be longer in SBS, the rate of RBO was similar: 48% and 43% in SIS and SBS groups, respectively. The causes of RBO were quite different: biliary sludge in the SIS group and tumor ingrowth in the SBS group. While the crossed stent mesh at the hilum in the SIS method can potentially enhance sludge formation, the use of a small diameter stent might increase RBO due to tumor ingrowth in SBS group. For further evaluation of long-term outcomes, we also compared TRBO after the first re-interventions and conversion rates to PTBD, but those were also comparable between two groups. In SBS group, EUS-guided biliary drainage was performed as re-intervention due to potential advantages of internal drainage [30, 31].

It should be noted that SBS tended to have high AE rate than SIS (46% in SBS and 23% in SIS). In a previous comparative study by Naitoh also demonstrated a higher AE rate in SBS above the papilla (44% in SBS vs. 13% in SIS), but post-procedure pancreatitis was not observed [19]. The SBS deployment across the papilla has potential disadvantages of overexpansion of the papilla and common bile duct. In our study, pancreatitis was exclusively observed in SBS group.

Endoscopic biliary stenting for hilar biliary stricture has reportedly a higher risk for pancreatitis [32]. In addition, non-pancreatic cancer and high axial force are two risk factors for pancreatitis after metallic stent placement [33]. Although pancreatitis was not severe and resolved without any invasive interventions, it is a potentially lethal adverse event. A recent study of SBS with the same ucWF demonstrated the safety of this method without any pancreatitis in 17 cases [24]. There are two methods in SBS: simultaneous stent deployment above the papilla using a small stent delivery system and sequential stent deployment across the papilla. The former method deploying the stent above the papilla is easy for stent deployment, but we sometimes encounter difficulties in passing a guidewire through each stent at the time of re-interventions. A comparative study showed that pancreatitis was observed only after SBS across the papilla, and the rate was 7.5% [23]. The reasons of a high pancreatitis rate of 29% in our study population were unclear, but the extent of endoscopic sphincterotomy might be insufficient to prevent pancreatitis, or the axial force of stents might affect the rate of pancreatitis as previously reported in distal biliary obstruction [33]. Moreover, SBS was more often performed by trainees, which might lead to the higher early AE rate in SBS group.

The role of re-interventions is increasing in hilar MBO [34,35,36]. Intuitionally, re-interventions for SBS across the papilla appear technically easy, but TRBO after the first re-intervention and the procedure time for re-interventions of occluded UMSs were comparable between two groups. As we previously reported [16], re-interventions for SIS using a large-cell-type UMS are technically feasible, but the clinical outcomes might differ by the local expertise. PTBD still has a role as re-interventions for refractory hilar MBO, and the role of EUS-BD should be further investigated in a large cohort.

Our study has some limitations. The first and major limitation is its retrospective design. The stent placement method was chronologically selected, not according to the endoscopists’ preferences. SIS and SBS methods were consecutively applied during each period. The expertise in our centers has allowed high technical success rates in both groups, and our study results might not be extrapolated to non-expert centers. Nonsignificant longer overall survival in SBS group might suggest the presence of some biases. The rate of metastatic disease was relatively higher in SIS (23%) as compared to that in SBS (4%), and there might be a cohort effect including recent improvement in chemotherapy. Secondly, various stents are now commercially available for hilar stenting and clinical outcomes might differ according to the stent types and the generalizability of our study results might be limited. We compared SIS and SBS methods, but SIS was placed above the papilla and SBS was placed across the papilla, considering the stent characteristics used in our study. The location of the distal stent end can potentially affect clinical outcomes, but one retrospective study on SBS stenting [23] revealed that only the incidence of pancreatitis was higher in cases with SBS across the papilla, which was in line with our study results. Finally, due to the advancement of chemotherapy, the prognosis of unresectable hilar MBO has been gradually improved and not a few patients survive longer than the initial stent patency and need re-interventions. Thus, hilar stenting should be evaluated not only by the initial stent patency but other clinical outcomes such as a total number of procedures, conversion rate to PTBD and the quality of life in this palliative setting.

In conclusion, both SIS and SBS were technically feasible with comparable long-term outcomes in unresectable hilar MBO. Thus, either technique, SIS or SBS, can be selected according to each endoscopist’s expertise.

References

Perdue DG, Freeman ML, DiSario JA, et al. Plastic versus self-expanding metallic stents for malignant hilar biliary obstruction: a prospective multicenter observational cohort study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:1040–1046.

Sangchan A, Kongkasame W, Pugkhem A, et al. Efficacy of metal and plastic stents in unresectable complex hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:93–99.

Rerknimitr R, Angsuwatcharakon P, Ratanachu-ek T, et al. Asia-Pacific consensus recommendations for endoscopic and interventional management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:593–607.

Mukai T, Yasuda I, Nakashima M, et al. Metallic stents are more efficacious than plastic stents in unresectable malignant hilar biliary strictures: a randomized controlled trial. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:214–222.

Gao DJ, Hu B, Ye X, et al. Metal versus plastic stents for unresectable gallbladder cancer with hilar duct obstruction. Dig Endosc Off J Jpn Gastroenterol Endosc Soc. 2017;29:97–103.

Dumonceau JM, Tringali A, Papanikolaou IS, et al. Endoscopic biliary stenting: indications, choice of stents, and results: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) clinical guideline—updated october 2017. Endoscopy. 2018;50:910–930.

Vienne A, Hobeika E, Gouya H, et al. Prediction of drainage effectiveness during endoscopic stenting of malignant hilar strictures: the role of liver volume assessment. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:728–735.

Takahashi E, Fukasawa M, Sato T, et al. Biliary drainage strategy of unresectable malignant hilar strictures by computed tomography volumetry. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4946–4953.

Chang WH, Kortan P, Haber GB. Outcome in patients with bifurcation tumors who undergo unilateral versus bilateral hepatic duct drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:354–362.

De Palma GD, Galloro G, Siciliano S, et al. Unilateral versus bilateral endoscopic hepatic duct drainage in patients with malignant hilar biliary obstruction: results of a prospective, randomized, and controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:547–553.

Naitoh I, Ohara H, Nakazawa T, et al. Unilateral versus bilateral endoscopic metal stenting for malignant hilar biliary obstruction. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:552–557.

Iwano H, Ryozawa S, Ishigaki N, et al. Unilateral versus bilateral drainage using self-expandable metallic stent for unresectable hilar biliary obstruction. Dig Endosc Off J Jpn Gastroenterol Endosc Soc. 2011;23:43–48.

Liberato MJ, Canena JM. Endoscopic stenting for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: efficacy of unilateral and bilateral placement of plastic and metal stents in a retrospective review of 480 patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:103.

Lee TH, Kim TH, Moon JH, et al. Bilateral versus unilateral placement of metal stents for inoperable high-grade malignant hilar biliary strictures: a multicenter, prospective, randomized study (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:817–827.

Kogure H, Isayama H, Nakai Y, et al. Newly designed large cell Niti-S stent for malignant hilar biliary obstruction: a pilot study. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:463–467.

Kogure H, Isayama H, Nakai Y, et al. High single-session success rate of endoscopic bilateral stent-in-stent placement with modified large cell Niti-S stents for malignant hilar biliary obstruction. Dig Endosc Off J Jpn Gastroenterol Endosc Soc. 2014;26:93–99.

Lee JM, Lee SH, Chung KH, et al. Small cell-versus large cell-sized metal stent in endoscopic bilateral stent-in-stent placement for malignant hilar biliary obstruction. Dig Endosc Off J Jpn Gastroenterol Endosc Soc. 2015;27:692–699.

Saleem A, Baron TH, Gostout CJ. Large-diameter therapeutic channel duodenoscope to facilitate simultaneous deployment of side-by-side self-expandable metal stents in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:628–631.

Naitoh I, Hayashi K, Nakazawa T, et al. Side-by-side versus stent-in-stent deployment in bilateral endoscopic metal stenting for malignant hilar biliary obstruction. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:3279–3285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-012-2270-9.

Law R, Baron TH. Bilateral metal stents for hilar biliary obstruction using a 6Fr delivery system: outcomes following bilateral and side-by-side stent deployment. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2667–2672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-013-2671-4.

Yoshida T, Hara K, Imaoka H, et al. Benefits of side-by-side deployment of 6-mm covered self-expandable metal stents for hilar malignant biliary obstructions. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Sci. 2016;23:548–555.

Kawakubo K, Kawakami H, Kuwatani M, et al. Single-step simultaneous side-by-side placement of a self-expandable metallic stent with a 6-Fr delivery system for unresectable malignant hilar biliary obstruction: a feasibility study. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:151–155.

Cosgrove N, Siddiqui AA, Adler DG, et al. A comparison of bilateral side-by-side metal stents deployed above and across the sphincter of oddi in the management of malignant hilar biliary obstruction. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;51:528–533.

Hsieh J, Thosani A, Grunwald M, et al. Serial insertion of bilateral uncovered metal stents for malignant hilar obstruction using an 8 Fr biliary system: a case series of 17 consecutive patients. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2015;4:348–353.

Moon JH, Rerknimitr R, Kogure H, et al. Topic controversies in the endoscopic management of malignant hilar strictures using metal stent: side-by-side versus stent-in-stent techniques. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:650–656.

Lee TH, Moon JH, Choi JH, et al. Prospective comparison of endoscopic bilateral stent-in-stent versus stent-by-stent deployment for inoperable advanced malignant hilar biliary stricture. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90:222–230.

Ito K, Sakamoto Y, Isayama H, et al. The impact of MDCT and endoscopic transpapillary mapping biopsy to predict longitudinal spread of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2018;22:1528–1537.

Isayama H, Hamada T, Yasuda I, et al. TOKYO criteria 2014 for transpapillary biliary stenting. Dig Endosc Off J Jpn Gastroenterol Endosc Soc. 2015;27:259–264.

Nakai Y, Isayama H, Tsujino T, et al. Intraductal US in the assessment of tumor involvement to the orifice of the cystic duct by malignant biliary obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:78–83.

Kongkam P, Tasneem AA, Rerknimitr R. Combination of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage in malignant hilar biliary obstruction. Dig Endosc Off J Jpn Gastroenterol Endosc Soc. 2019;31:50–54.

Nakai Y, Kogure H, Isayama H, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage for unresectable hilar malignant biliary obstruction. Clin Endosc. 2019;52:220–225.

Tarnasky PR, Cunningham JT, Hawes RH, et al. Transpapillary stenting of proximal biliary strictures: does biliary sphincterotomy reduce the risk of postprocedure pancreatitis? Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:46–51.

Kawakubo K, Isayama H, Nakai Y, et al. Risk factors for pancreatitis following transpapillary self-expandable metal stent placement. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:771–776.

Shiomi H, Matsumoto K, Isayama H. Management of acute cholangitis as a result of occlusion from a self-expandable metallic stent in patients with malignant distal and hilar biliary obstructions. Dig Endosc Off J Jpn Gastroenterol Endosc Soc. 2017;29:88–93.

Inoue T, Naitoh I, Okumura F, et al. Reintervention for stent occlusion after bilateral self-expandable metallic stent placement for malignant hilar biliary obstruction. Dig Endosc Off J Jpn Gastroenterol Endosc Soc. 2016;28:731–737.

Okuno M, Mukai T, Iwashita T, et al. Evaluation of endoscopic reintervention for self-expandable metallic stent obstruction after stent-in-stent placement for malignant hilar biliary obstruction. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Sci. 2019;26:211–218.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KI, TH, HI, and YN conceived and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the article. TS, RH, KS, TS, NT, SM, HK, YI, HY, SM, DA, DM, MT, and KK critically revised the article for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the final approval of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Yousuke Nakai and Hiroyuki Isayama received research grant from Boston Scientific Japan. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ishigaki, K., Hamada, T., Nakai, Y. et al. Retrospective Comparative Study of Side-by-Side and Stent-in-Stent Metal Stent Placement for Hilar Malignant Biliary Obstruction. Dig Dis Sci 65, 3710–3718 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-020-06155-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-020-06155-z