Abstract

Background

In Crohn’s disease patients failing infliximab therapy, interventions defined by an algorithm based on infliximab and anti-infliximab antibody measurements have proven more cost-effective than intensifying the infliximab regimen.

Aim

This study investigated long-term economic outcomes at the week 20 follow-up study visit and after 1 year. Clinical outcomes were assessed at week 20.

Methods

Follow-up from a 12-week, single-blind, clinical trial where patients with infliximab treatment failure were randomized to infliximab intensification (5 mg/kg every 4 weeks) (n = 36), or algorithm-defined interventions (n = 33). Accumulated costs, expressed as mean costs per patient, were based on the Danish National Patient Registry.

Results

At the scheduled week 20 follow-up study visit, response and remission rates were similar in all study subpopulations between patients treated by the algorithm or by infliximab intensification. However, the sum of healthcare costs related to Crohn’s disease was substantially lower (31 %) for patients randomized to algorithm-based interventions than infliximab intensification in the intention-to-treat population: $11,940 versus $17,236; p = 0.005. For per-protocol patients (n = 55), costs at the week 20 follow-up visit were even lower (49 %) in the algorithm group: $8,742 versus $17,236; p = 0.002. Figures were similar for patients having completed the 12-week trial as per protocol (50 % reduction in costs) (n = 45). Among patients continuing the allocated study intervention throughout the entire 20-week follow-up period (n = 29), costs were reduced by 60 % in algorithm-treated patients: $7,056 versus $17,776; p < 0.001. Cost-reduction percentages remained stable throughout one year.

Conclusion

Economic benefit of algorithm-based interventions at infliximab failure is maintained throughout 1 year.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α therapy with infliximab (IFX) is effective in Crohn’s disease [1]. About half of the patients who initially benefit from IFX later experience recurrence of active disease despite ongoing IFX maintenance therapy [1–3]. International guidelines suggest intensifying the IFX regimen in this event [4–6]. However, clinical effect is regained on the short term in less than half, and with diminishing effectiveness over time [2]. Routine use of this strategy thus introduces risk of overtreatment and a breach in cost-effectiveness [2, 7]. Furthermore, uncontrolled inflammatory activity during periods of continued ineffective IFX treatments may cause unnecessary disease progression [2, 4–6].

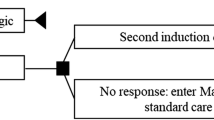

We have proposed an alternative strategy that is based on IFX and anti-IFX antibody (Ab) measurements to identify underlying immunopharmacological mechanisms for IFX failure and corresponding interventions in each individual patient [8, 9]. As detailed in Fig. 1, this algorithm operates with different situations where treatment failure most likely is caused by sub-therapeutic drug levels due to changes in pharmacokinetics afforded by either immune- or non-immune mechanisms, or in case of therapeutic drug levels, by pharmacodynamic issues or non-inflammatory conditions resembling relapse of active disease. In a 12-week randomized controlled trial, we observed substantial reductions in healthcare costs related to Crohn’s disease when using this algorithm. Importantly, this was obtained at similar clinical outcomes as the IFX intensification strategy [10]. The current scheduled follow-up study investigated long-term outcomes.

Treatment algorithm for Crohn’s disease patients with loss of response to infliximab (IFX) therapy. Abs antibodies, CD Crohn’s disease, IFX infliximab, sc subcutaneously, TNF tumor necrosis factor. Reproduced from Steenholdt et al. [10] with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd

Methods

Study Design and Patients

This was a follow-up study from a 12-week randomized controlled clinical trial where Crohn’s disease patients with loss of response to standard IFX maintenance therapy with regular infusions of 5 mg/kg every 6–8 weeks were equally randomized to either an intensified IFX regimen (5 mg/kg every 4 weeks) or algorithm-defined interventions based on IFX and anti-IFX Abs at time of treatment failure as detailed in Fig. 1 [8, 10]. At inclusion, all patients had recurrence of active disease defined as a Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) ≥220 and/or at least one draining perianal fistula. Patients were treated at the discretion of the physician from end of trial at week 12 and onwards. Patients were evaluated clinically at the scheduled follow-up visit at week 20. Economic evaluations were done at week 20 and after 1 year. Patients were blinded for randomization group and results of serum analyses. Physicians were blinded for IFX and anti-IFX Ab test results from patients in the IFX intensification group. Blinding was maintained throughout week 20. The trial was carried out at six Danish centers from 2009 through 2011. It was monitored by Good Clinical Practice units from the Universities of Copenhagen, Aarhus, and Odense, approved by the Danish Medicines Agency (EudraCT 2009-009926-94), the regional ethics committees (HA-2009-009), and the Danish Data Protection Agency (2007-58-0015; 750.89-2), and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00851565; protocol summary available). All subjects gave oral and written informed consent.

Endpoints

The objective was to assess long-term costs and clinical outcomes of treatment of Crohn’s disease patients with loss of response to IFX maintenance therapy using a proposed mechanistic algorithm as compared to standard intensified IFX regimen. Costs were assessed at the scheduled follow-up trial visit after 20 weeks and also after 1 year. Clinical outcomes were assessed after 20 weeks.

Evaluations

Costs

Cost data were obtained from the Danish National Patient Registry (NPR), which holds information on all inpatient and outpatient contacts in Danish hospitals. This unique register allows accurate determination of medical expenses on an individual patient basis as it includes administrative information, diagnoses, and diagnostic and treatment procedures. All disease-related procedures registered in combination with Crohn’s disease were identified for each patient, and costs were defined by Diagnosis-Related Grouping (DRG) tariffs. Cost of measuring IFX and anti-IFX Abs was also included. Pricing of biologic agents was set to the standard price paid by all Danish hospitals as at January 1, 2012 (Amgros, Copenhagen, Denmark). A standard IFX dose corresponding to 400 mg per infusion was used in the primary analysis and was based on the overall mean weight (72 kg) of included patients receiving IFX. Total healthcare costs were obtained as described above and without specification of diagnosis. Costs for each patient were calculated in Danish kroner as accumulated costs from inclusion and converted to USD ($).

Clinical

Patients were evaluated clinically at all study visits, and scores were obtained on CDAI (luminal) and/or Perianal Disease Activity Index (PDAI) and number of draining fistulas (fistulizing), and Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ). Clinical response was defined as ≥70 point reduction in CDAI from baseline in luminal disease and a reduction in active fistulas of ≥50 % from baseline in fistulizing disease. Clinical remission was defined as CDAI ≤150 and complete closure of all fistulas despite gentle pressure.

Analyses of IFX and Anti-IFX Abs

Serum samples for IFX and anti-IFX Ab testing were collected at time of reported IFX treatment failure, and with timing corresponding to a potential next IFX administration (i.e., trough level). Samples were sent for immediate analysis by radioimmunoassay (RIA) (Biomonitor A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark), and study interventions in the algorithm group were based on these test results. All analyses were done under blinded conditions. IFX and anti-IFX Abs were measured by fluid-phase RIA as previously detailed [10, 11]. IFX levels were classified as therapeutic (≥0.5 µg/ml) or sub-therapeutic (<0.5 µg/ml), and anti-IFX Abs as detectable or undetectable [limit of quantification (LOQ) 10 assay-specific units (U)/ml], based on available data [11].

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were compared by Fisher’s exact test or Chi-squared test and continuous variables by unpaired T test or Mann–Whitney test, as appropriate. Costs were analyzed using arithmetic means and compared by nonparametric bootstrap-t method. Data were analyzed in the following populations: intention-to-treat, per-protocol, per-protocol completion at end of trial week 12, and per-protocol completion at end of follow-up week 20. Patients who dropped out and missing data were included in the statistical analyses at subsequent study visits using the last observations carried forward for efficacy (response and remission), CDAI, PDAI, and biochemical parameters and by using actual costs (cost data from an intention-to-treat patient in the algorithm group were unavailable and thus not included). Patients who were withdrawn due to lack of effect of study treatment were classified as non-responders at subsequent study visits, and the other parameters were handled as for dropouts. Patients withdrawn due to causes other than lack of treatment effect were handled as dropouts. Sample size calculations were performed as part of the original trial [10]. Analyses were done in SPSS version 20 (IBM, Somers, NY, USA) and Stata 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Two-sided p values <0.05 were significant.

Results

Patients

Enrollment and Treatment

Of 36 patients with symptomatic IFX treatment failure and randomized to IFX intensification, 28 patients completed the 12-week trial period as per protocol (Fig. 2). Of these, 18 patients continued the intensified IFX regimen at the discretion of the treating physician, nine patients returned to a less intensive IFX regimen, and a single patient was lost to follow-up. A total of 13 patients (46 %) completed the 20-week follow-up period on the intensified IFX regimen, whereas five patients discontinued IFX due to treatment failure.

Among 33 patients randomized to treatment by the algorithm, 17 patients completed the 12-week trial period as per protocol (Fig. 2). All except one (94 %) continued treatment specified by the algorithm throughout the 20-week follow-up period at the discretion of the physician. Patients handled in accordance with the algorithm during the 12-week clinical trial period had a higher propensity of continuing the same type of treatment until follow-up than patients treated by IFX intensification: OR 18 [2–159], p < 0.01.

Characteristics

Patient characteristics were comparable between randomization groups (Table 1), and between all study subpopulation (not shown).

Mechanisms for Secondary IFX Treatment Failure

The majority of patients had therapeutic serum levels of IFX at time of treatment failure suggesting a pharmacodynamic mechanism or a non-inflammatory condition resembling relapse of active disease (Table 1). This subgroup of patients was in the algorithm group handled according to a review of the clinical condition by examinations for ongoing inflammatory disease activity, non-inflammatory complications, or other reasons for reported symptoms. As a result, per-protocol patients were treated for bile acid malabsorption (n = 3), strictures (n = 1), or irritable bowel syndrome (n = 1) or were optimized on conventional agents (n = 2 conventional immunosuppressives, n = 2 fistulizing disease using antibiotics, n = 2 oral hydrocortisone or budesonide, n = 1 natalizumab, n = 1 topical agents), as previously detailed [10]. Less commonly, failure was presumably due to immunogenicity of IFX or to non-immune-mediated changes in pharmacokinetics (Table 1). There was no difference in proposed mechanisms for treatment failure between randomization groups in the different study populations.

Economic Outcomes

At the scheduled follow-up study visit at week 20, the sum of healthcare costs related to Crohn’s disease was substantially and highly significantly lower in the algorithm group than in the IFX intensification group in all study populations (Table 2). Cost reductions were highest (60 %) among patients having completed all 20 weeks as outlined in the algorithm. However, costs were consistently reduced in patients randomized to treatment by the algorithm also in the intention-to-treat population (31 %), per-protocol population (49 %), and per-protocol completion end of trial week 12 population (50 %) (Table 2). Furthermore, economic superiority of the algorithm was maintained throughout one year, and with stable cost-reduction percentages (Table 3). Inclusion of all type of healthcare costs, irrespectively of relation to the Crohn’s disease, revealed similar proportional cost savings.

Clinical Outcomes

Disease control at the scheduled clinical follow-up visit at week 20, defined as clinical response and clinical remission, was similar between patients who had been dose intensified on IFX or treated by the algorithm in all study subpopulations (Table 4). Life quality and biochemical outcomes were also comparable between randomization groups (Supplementary Table 1). Alternative definition of clinical response as CDAI decrease ≥100, evaluation of decrease in CDAI or PDAI scores, and subgroup analysis of clinical outcomes in patients stratified for grouping in algorithm revealed findings similar to the above (Supplementary Table I).

Sensitivity Analyses

Robustness of economic findings was assessed in independent sensitivity analyses both at week 20 and after 1 year (Supplementary Table II). The sensitivity analyses included (1) inclusion of estimated costs for administration of biologic agents, (2) use of actual IFX dosing, and (3) price reductions in 3.5 and 7 % on biologic agents. Findings were similar to the above.

Discussion

This was a predefined follow-up study from a clinical trial investigating whether a personalized patient treatment based on IFX exposure and anti-IFX Abs at time of therapeutic failure obtained in order to identify the most likely mechanistic cause for loss of response would rationally guide interventions and prove more cost-effective than IFX intensification [8, 9, 12]. The current study shows that interventions based on the algorithm resulted in substantial cost reductions when evaluated at the scheduled follow-up trial visit after 20 weeks. Further, that economic superiority was maintained throughout one year. Importantly, the cost savings observed during the original 12-week trial period remained statistically stable throughout one year, thus indicating that use of the algorithm results in long-term sustainable cost savings (Table 5). As the proportional reduction in costs attained by use of the algorithm remained stable (i.e., reductions in percentage), the total amount saved increased substantially over time. Reduction in costs was not attained at the expense of increase in other types of healthcare costs. Even though this study extension was not formally powered to compare clinical outcomes, we observed comparable clinical, biologic, and life quality outcomes between patients treated according to the algorithm or by IFX intensification at the clinical follow-up visit after 20 weeks [10].

The algorithm evaluated here was originally put forward by our group [8] and has later been supported by others [13, 14]. It operates with distinct proposed mechanisms for IFX treatment failure defined by therapeutic or sub-therapeutic IFX levels, and detectable or undetectable anti-IFX Abs, to assess whether loss of response is more likely due to immunogenicity than to non-immune-mediated pharmacokinetic; or rather to pharmacodynamic issues or non-inflammatory conditions resembling relapse of active disease (Fig. 1). This type of individualized treatment approach has not yet been reported in other prospective clinical trials. However, a simulation study using clinical trial data to evaluate the algorithm supported our findings [15]. Findings in a randomized trial of adalimumab are in line with our observations [16]. Observational studies have reported superior clinical outcomes when using algorithms similar to ours [13, 17]. The small sample size of the current study does not allow direct comparisons on clinical efficacy of interventions defined by the algorithm as compared to IFX intensification in the individual algorithm subgroups. Taken together, accumulating data supports that patients with IFX treatment failure could favorably be handled on a personalized basis where interventions are tailored according to underlying mechanisms for treatment failure as identified by drug and antidrug Ab measurements instead of applying standardized cost-ineffective intensification regimens deduced from average responses in large patient cohorts [9].

This follow-up study was designed to evaluate economic and clinical endpoints assessed in the original 12-week trial, at time of the scheduled follow-up study visit after 20 weeks, and to additionally assess long-term economic outcomes after 1 year. This study design had been defined prior to the undertaking of the trial. Outcomes were assessed in all study populations and with consistent results, indicating that the observations are robust. The fact that patients were handled at the discretion of the treating physician from end of trial and onwards, as well as a limited number of patients completing the 20-week follow-up period, does warrant caution when extrapolating the results. However, as the proportional cost reductions (percentage) remained stable throughout the observation period, savings related to use of the algorithm were likely to be persistent. Furthermore, estimation of healthcare costs had high internal validity as the Danish healthcare system provides a unique setup, which allows very accurate determination at an individual level taking diagnosis into account, and with the exact amount of each type of expense uniformly defined by the Danish Health and Medicines Authority. The external validity is also considered relatively high, as there is no reason to expect fundamentally different results in other healthcare settings as expenses for intensified IFX are substantially higher than all other currently available interventions. Furthermore, cost findings were found to be robust to changes in economic variables as evaluated in a series of sensitivity analyses. The cost analysis included costs related to testing for IFX and anti-IFX Abs, and even though the price for these analyses may differ between countries, cost-effectiveness of immunopharmacological monitoring has proven to be robust [15].

Reduction in costs related to treatment of Crohn’s disease achieved by the algorithm was most likely driven by discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy in patients with therapeutic drug levels at time of manifestation of IFX treatment failure. The majority of these patients had endoscopically verified ongoing inflammation indicating a pharmacodynamic mechanism due to, e.g., activation of alternative inflammatory pathways bypassing TNF-α as pathogenetically central pro-inflammatory cytokine in patients treated with a TNF-inhibitor (IFX) over a prolonged period of time [8, 10, 18]. In support hereof, the clinical outcome of an intensified IFX regimen applied at treatment failure seems to be associated with the magnitude of increase in IFX exposure but with a notable proportion of patients not responding despite equally high increase in serum IFX levels [19]. Patients were in this case treated by optimization of conventional immunosuppressive agents in this study. We speculate that change to biologic agents targeting different inflammatory pathway than TNF-α may be favorable in this situation [20]. This hypothesis could, however, not be addressed in the current study, as only TNF-inhibitors were approved for Crohn’s disease in Europe at the time of study. A notable subset of patients with therapeutic drug levels at treatment failure suffered from various non-inflammatory conditions resembling relapse of active disease. Thus, despite clinically active disease based on CDAI criteria, these patients had no objective evidence of inflammation as underlying cause of symptoms. This observation highlights the importance of excluding non-inflammatory mechanisms for symptoms of relapse of Crohn’s disease at an early stage. The fact that a minority of included patients did not have endoscopic or radiographic disease activity may have introduced bias both with respect to clinical and economic outcomes. However, at the time where this study was done, it was not routine practice to validate also by other modalities manifest symptomatic relapse of Crohn’s disease as defined by CDAI scores in patients with well-established disease in ongoing IFX maintenance therapy. Importantly, as this was a randomized trial, a comparable proportion without endoscopic active disease should be expected in both randomization groups [21].

In conclusion, clinical interventions at IFX treatment failure based on monitoring of IFX and anti-IFX Abs are long-term cost-effective method compared to IFX dose intensification.

References

Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, Hanauer SB, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:644–659.

Gisbert JP, Panes J. Loss of response and requirement of infliximab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:760–767.

Allez M, Karmiris K, Louis E, et al. Report of the ECCO pathogenesis workshop on anti-TNF therapy failures in inflammatory bowel diseases: definitions, frequency and pharmacological aspects. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:355–366.

Dignass A, Van AG, Lindsay JO, et al. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:28–62.

D’Haens GR, Panaccione R, Higgins PD, et al. The London Position Statement of the World Congress of Gastroenterology on Biological Therapy for IBD with the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization: when to start, when to stop, which drug to choose, and how to predict response? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:199–212.

Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011;60:571–607.

Katz L, Gisbert JP, Manoogian B, et al. Doubling the infliximab dose versus halving the infusion intervals in Crohn’s disease patients with loss of response. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2026–2033.

Bendtzen K, Ainsworth M, Steenholdt C, Thomsen OO, Brynskov J. Individual medicine in inflammatory bowel disease: monitoring bioavailability, pharmacokinetics and immunogenicity of anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha antibodies. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:774–781.

Bendtzen K. Anti-TNF-alpha biotherapies: perspectives for evidence-based personalized medicine. Immunotherapy. 2012;4:1167–1179.

Steenholdt C, Brynskov J, Thomsen OO, et al. Individualised therapy is more cost-effective than dose intensification in patients with Crohn’s disease who lose response to anti-TNF treatment: a randomised, controlled trial. Gut. 2014;63:919–927.

Steenholdt C, Bendtzen K, Brynskov J, Thomsen OO, Ainsworth MA. Cut-off levels and diagnostic accuracy of infliximab trough levels and anti-infliximab antibodies in Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:310–318.

Bendtzen K. Personalized medicine: theranostics (therapeutics diagnostics) essential for rational use of tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists. Discov Med. 2013;15:201–211.

Afif W, Loftus EV Jr, Faubion WA, et al. Clinical utility of measuring infliximab and human anti-chimeric antibody concentrations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1133–1139.

Khanna R, Sattin BD, Afif W, et al. Review article: a clinician’s guide for therapeutic drug monitoring of infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:447–459.

Velayos FS, Kahn JG, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG. A test-based strategy is more cost effective than empiric dose escalation for patients with Crohn’s disease who lose responsiveness to infliximab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:654–666.

Roblin X, Rinaudo M, Del TE, et al. Development of an algorithm incorporating pharmacokinetics of adalimumab in inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1250–1256.

Vaughn BP, Martinez-Vazquez M, Patwardhan VR, Moss AC, Sandborn WJ, Cheifetz AS. Proactive therapeutic concentration monitoring of infliximab may improve outcomes for patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results from a pilot observational study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1996–2003.

Nikolaus S, Raedler A, Kuhbacker T, Sfikas N, Folsch UR, Schreiber S. Mechanisms in failure of infliximab for Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2000;356:1475–1479.

Steenholdt C, Bendtzen K, Brynskov J, et al. Changes in serum trough levels of infliximab during treatment intensification but not in anti-infliximab antibody detection are associated with clinical outcomes after therapeutic failure in Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2015. Epub. 01/09/2015.

Targan SR, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, et al. Natalizumab for the treatment of active Crohn’s disease: results of the ENCORE Trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1672–1683.

Steenholdt C, Ainsworth MA. Authors’ response: importance of defining loss of response before therapeutic drug monitoring. Gut. (Epub ahead of print). doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2014-309044.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following people for their technical assistance: Hanne Fuglsang, Anne Hallander, Vibeke Hansen, Birgit Kristensen, Yvonne Krogager, Charlotte Kühnel, Lene Neergaard, Lise Olsen, Anni Petersen (Dept. of Gastroenterology, Herlev University Hospital, Denmark); Pierre Nourdine Bouchelouche and Sussi Holbæk (Dept. of Medical Gastroenterology, Køge University Hospital, Denmark); Tove Nygaard (Dept. of Medical Gastroenterology, Aalborg University Hospital, Denmark); Rikke Charlotte Andersen, Lisbet Gerdes, Catriona Nairn Marcussen, Birgitte Sperling Wilms Nielsen, and Inger Schjødt (Dept. of Hepatology and Gastroenterology V, Aarhus University Hospital), Carina Blixt (Dept. of Gastroenterology, Hvidovre University Hospital, Denmark); Anne Berg (Dept. of Medical Gastroenterology S, Odense University Hospital, Denmark). We would also wish to thank Biomonitor A/S and Prometheus Laboratories Inc. Support for this study was provided by unrestricted research grants from Aase and Ejnar Danielsen’s Foundation, Beckett Foundation, Danish Biotechnology Program, Danish Colitis-Crohn Society, Danish Medical Association Research Foundation, Frode V. Nyegaard and Wife’s Foundation, Health Science Research Foundation of Region of Copenhagen, Herlev Hospital Research Council, Lundbeck Foundation, P. Carl Petersen’s Foundation, Ole Østergaard Thomsen’s Research Foundation, and Jørn Brynskov’s Research Foundation.

Conflict of interest

C. Steenholdt has served as speaker for MSD, Abbvie, and Pfizer and as a consultant for MSD and Takeda Pharmaceutical LTD. J. Brynskov has served as advisory board member for Abbvie. OØ Thomsen has served as a speaker and consultant for UCB and Zealand Pharma; speaker for MSA; and primary investigator for Amgen, Biogen, Novo-Nordisk, and Pfizer. L.K. Munck has served as speaker for MSD and participated in a safety study with Abbvie. J. Fallingborg has served as primary investigator for Centocor, Abbvie, MSD, and UCB and as a consultant for Abbvie and MSD. L.A. Christensen has served as speaker for Abbvie, Tillotts Pharma, and Ferring and as a consultant for MSD. J. Kjeldsen has served as a speaker for MSD, Abbvie, and Tillotts. K. Bendtzen has served as a speaker for Pfizer and Biomonitor; and owns stocks in Novo-Nordisk and Biomonitor. B.A. Jacobsen has served as advisory board member at Tillots Pharma. G. Pedersen, A.S. Oxholm, J. Kjellberg, and M.A. Ainsworth have no interests to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Steenholdt, C., Brynskov, J., Thomsen, O.Ø. et al. Individualized Therapy Is a Long-Term Cost-Effective Method Compared to Dose Intensification in Crohn’s Disease Patients Failing Infliximab. Dig Dis Sci 60, 2762–2770 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-015-3581-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-015-3581-4